#Philosophyoftime

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Artillery Clock: What Living Near a Range Taught Me About Time

Living near an artillery range changes your relationship with time forever. Each explosion isn't just noise—it's a heartbeat of existence, a physical reminder that another moment has just passed and will never return. It's a unique chronometer that measures life not in silent seconds, but in reverberating booms that shake your windows and resonate in your chest.

At first, these explosions were my enemies. They interrupted thoughts, shattered concentration, and disturbed any semblance of peace. But over time, they became something else entirely: teachers of one of life's most crucial lessons.

The Physical Reality of Time

We live in a world where time has become abstract—numbers changing on screens, calendar notifications, digital reminders. But there's something profoundly different about feeling time's passage through your entire body. When each moment arrives with a force that makes your bones vibrate, you can't maintain the comfortable illusion that time is an infinite resource.

The artillery range strips away our modern cushioning from time's reality. Each boom asks a simple question: What did you do with that moment? Did you use it to move forward, to build, to grow? Or did you let another precious block of time slip away into the void?

The Relentless Auditor

Every explosion becomes an audit of your commitment:

Did you protect what needed protecting?

Did you build what needed building?

Did you teach what needed teaching?

Did you act when action was needed?

The artillery doesn't care about your excuses. It doesn't pause because you need more time. It just keeps marking the passages, keeps counting down the moments, keeps reminding you that time is the one resource you can never mine more of.

From Awareness to Action

This isn't about living in fear or constant stress. It's about living with acute awareness. When you can physically feel time's passage, you start making different choices. The transformation happens in stages, each boom pushing you further along the path from passive observer to active participant in your own life.

First comes the awakening—the moment you realize that time isn't just passing, it's passing through you. Each explosion forces you to acknowledge another moment gone, another opportunity either seized or lost. This awareness begins to seep into your decision-making process, creating a new sense of urgency that's not about panic, but about presence.

Then comes the shift in how you approach possibilities. When time becomes tangible, you stop treating ideas as distant dreams to be pursued "eventually." Instead, they become immediate candidates for action. Plans become actions because you understand that planning without execution is just another form of procrastination. Ideas become projects because you realize that an unrealized idea is just a ghost of what could have been. Intentions become commitments because you know that good intentions without action are worthless in the face of time's relentless march.

The most profound transformation happens in your relationship with "now." When each boom reminds you that time is finite, "someday" loses its power as a placeholder for dreams. The perfect moment reveals itself as the illusion it always was. You begin to understand that "now" isn't just a time—it's the only time you can actually use.

The most dangerous illusion in our modern world is the idea that there will always be more time—that we can wait for the perfect moment, the right conditions, the ideal circumstances. The artillery strips away this comfort. It makes time's passage unavoidable, undeniable, impossible to ignore. But more than that, it teaches you to use time rather than just watch it pass.

This new relationship with time manifests in practical changes:

You stop waiting for inspiration and start creating conditions for action

You reduce deliberation time not by rushing, but by making decisions with the understanding that perfect information is rarely available

You learn to distinguish between necessary preparation and unnecessary delay

You develop a bias toward action that's tempered by wisdom rather than paralyzed by fear

The shift from awareness to action isn't a single moment—it's a continuous process of aligning your behaviors with your understanding of time's value. Each boom becomes not just a reminder, but a call to action, a moment of decision, a chance to move from knowing to doing.

The Lesson of the Boom

What the artillery taught me wasn't about rushing. It was about removing the illusion that time is an infinite resource. Each explosion drove home the same lesson: Time will pass anyway. The only question is what you do with the time between the booms.

This understanding changes everything. When you truly internalize time's relentless forward motion, you stop waiting for permission. You stop looking for the perfect moment. You realize that the next boom is coming whether you're ready or not.

A Universal Timer

While most of us don't live near artillery ranges, we all have our own versions of these booms—deadlines, heartbeats, sunrise and sunset, the endless scroll of news and social media. The key is to find your own artillery clock, your own physical reminder of time's passage.

Because ultimately, that's what the artillery range teaches: Each moment that passes is gone forever, just like each round fired can never be unfired. The next boom is always coming. The only question is: What will you do before it arrives?

Take Action Towards Financial Independence

If this article has sparked your interest in the transformative potential of Bitcoin, there's so much more to explore! Dive deeper into the world of financial independence and revolutionize your understanding of money by following my blog and subscribing to my YouTube channel.

🌐 Blog: Unplugged Financial Blog Stay updated with insightful articles, detailed analyses, and practical advice on navigating the evolving financial landscape. Learn about the history of money, the flaws in our current financial systems, and how Bitcoin can offer a path to a more secure and independent financial future.

📺 YouTube Channel: Unplugged Financial Subscribe to our YouTube channel for engaging video content that breaks down complex financial topics into easy-to-understand segments. From in-depth discussions on monetary policies to the latest trends in cryptocurrency, our videos will equip you with the knowledge you need to make informed financial decisions.

👍 Like, subscribe, and hit the notification bell to stay updated with our latest content. Whether you're a seasoned investor, a curious newcomer, or someone concerned about the future of your financial health, our community is here to support you on your journey to financial independence.

Support the Cause

If you enjoyed what you read and believe in the mission of spreading awareness about Bitcoin, I would greatly appreciate your support. Every little bit helps keep the content going and allows me to continue educating others about the future of finance.

Donate Bitcoin: bc1qpn98s4gtlvy686jne0sr8ccvfaxz646kk2tl8lu38zz4dvyyvflqgddylk

#TimeManagement#Mindfulness#PhilosophyOfTime#PersonalGrowth#SelfReflection#Motivation#LiveInTheMoment#Awareness#ProductivityTips#ChangeYourPerspective#LifeLessons#OvercomeProcrastination#TickTockBoom#InspiredLiving#LifeAndTime#MakeEveryMomentCount#TimeIsFinite#MindsetShift#PurposefulLiving#ArtilleryClock#cryptocurrency#financial experts#digitalcurrency#financial education#finance#blockchain#financial empowerment#globaleconomy#bitcoin#unplugged financial

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ticking Obsession

by Thomas Marsh-Connors | Angry British Conservative Blog

Let me tell you something about myself that’s perhaps not immediately obvious I have a deeply unhealthy obsession with time. Not in the generic "I hate being late" way. No, my fixation goes far beyond punctuality or calendar apps. Though that is true too. This is something that took root in my mind back in 2006 and has since woven itself into my thoughts, habits, even how I see the world.

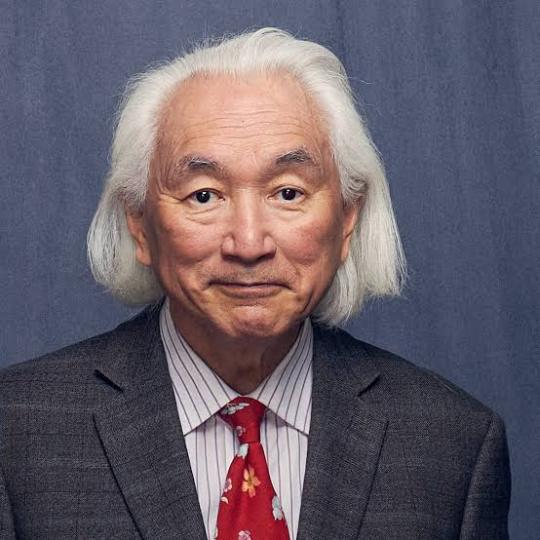

It all started with a BBC documentary. Not just any documentary, mind you this was the Time series hosted by none other than Dr. Michio Kaku. If you’ve never seen it, do yourself a favour and hunt it down. It’s a beautiful, mind-bending series in which Kaku an American physicist and master science communicator goes on a global journey to try and define, understand, and chase after that elusive thing we call time.

I was only a teenager at the time, but something about that series rewired my brain. Maybe it was the haunting realisation that time is both constant and completely out of our grasp. Maybe it was Kaku’s hypnotic, calm delivery a man who speaks of quantum mechanics like it’s poetry. Either way, from that day forward, time wasn’t just a part of my life. It became the part.

Naturally, I devoured everything Kaku ever wrote. Here’s a list of his books I’ve read and if you’ve got even a faint interest in science, technology, or the future of humanity, I strongly recommend you dive into them too:

Visions: How Science Will Revolutionize the 21st Century (1997)

Parallel Worlds: A Journey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos (2004)

Physics of the Impossible: A Scientific Exploration into the World of Phasers, Force Fields, Teleportation, and Time Travel (2008)

Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100 (2011)

The Future of the Mind: The Scientific Quest to Understand, Enhance, and Empower the Mind (2014)

The Future of Humanity: Terraforming Mars, Interstellar Travel, Immortality, and Our Destiny Beyond Earth (2018)

The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything (2021)

Quantum Supremacy: How the Quantum Computer Revolution Will Change Everything (2024)

Each book is a small detonation in the brain. Kaku has this rare gift: he makes impossibly complex theories about the multiverse, wormholes, and AI feel like gripping thrillers. But at the core of it all whether he’s talking about bending space-time, merging consciousness with machines, or building Type I civilisations time is always present.

And that’s the paradox, isn’t it? Time is everywhere and nowhere. We live inside of it, but we can’t see it. It drives every second of our lives, yet we barely understand it. It’s ticking constantly whether we choose to notice or not.

Since that first encounter in 2007, I’ve noticed time shaping the very architecture of my thought. I overthink minutes, waste hours worrying about the past, and have endless philosophical arguments in my head about the future. I obsess over history, write about nostalgia, and collect clocks yes, literal clocks. I time my coffee breaks. I remember whole days in terms of the exact hour something happened. It’s borderline manic, I know. But at the same time, I wouldn’t trade this obsession for anything. It keeps me grounded, aware, awake.

We live in a culture that is increasingly casual about time wasting it on meaningless distractions, pretending we have infinite tomorrows. But time is the one currency we can’t counterfeit. And once you become aware of that really aware you start living with urgency. Purpose. Gratitude.

So, if you're like me slightly mad and deeply curious give Dr Michio Kaku’s works a read. Rewatch that 2007 BBC series if you can. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll understand why I’ve never been able to escape the ticking echo of that first documentary.

Time isn’t just a dimension. For some of us, it’s a religion.

#Time#MichioKaku#PhysicsOfTime#BBCDocumentary#QuantumPhysics#ScienceBooks#ObsessionWithTime#TheGodEquation#PhysicsOfTheImpossible#FutureOfHumanity#TimeTravel#ScienceAddict#PhilosophyOfTime#BBCScience#ParallelWorlds#QuantumSupremacy#PersonalReflection#BookRecommendations#TimeIsPrecious#ThomasMarshConnors#new blog#today on tumblr

0 notes

Text

In the grand theater of existence, consider two metaphors - the Staircase and the Room.

The Staircase represents our human experience of reality. Each step is a moment in time, and we climb this staircase one step at a time, moving ever upward. We can look back at the steps we've climbed, remember them, learn from them, but we can never descend back down. Forward is the only direction we can go. This linear journey is our way of sorting through the data of existence. Each step is an event, a memory, a piece of data that we process and integrate into our understanding of the world.

Meanwhile, the Room represents a different, higher-dimensional plane of existence. Within this Room, there are no steps, no enforced sequence of events. All points in space and time exist simultaneously, accessible in any order. This Room offers a holistic view of reality, where all the data - all events, all moments - can be perceived at once. Entities in this Room can interact with the data in a non-linear fashion, experiencing events not in a sequence, but in an intricate web of interconnected moments.

These two metaphors - the Staircase and the Room - provide contrasting ways of perceiving and interacting with the data of existence. While we climb the Staircase, moving linearly through time, we may aspire to one day perceive the full scope of the Room, to experience the non-linear, interconnected web of reality in its entirety. As we ascend each step, we inch closer to understanding the grand tapestry of existence that unfolds within the Room.

#PerceptionOfReality#TimePerception#Consciousness#Metaphysics#HumanExperience#RealityMetaphors#LinearTime#NonlinearTime#DataOfExistence#ExistentialPhilosophy#Transcendence#HigherDimensionalExistence#SpiritualEvolution#CollectiveConsciousness#UnderstandingExistence#PhilosophyOfTime#TemporalPerception

0 notes

Text

youtube

> In a world driven by speed, why do we feel so slow inside?

This video explores the real root of modern impatience—not as a lack of discipline, but as a symptom of meaning erosion.

Through philosophical reflection, storytelling, and psychological insight, we confront the quiet crisis beneath our distractions.

We don’t simplify. We don’t perform. We reflect.

🧠 Bilingual | Rooted in Persian Thought, Spoken in a Global Voice

🎧 Watch if you’ve felt time slipping—but can’t remember why.

#Impatience ModernLife PhilosophyOfTime RealThinking FactUp ExistentialReflection MentalExhaustion WhyWeHurry DeepQuestions#Youtube

0 notes

Text

What If Time Was a Physical Substance 2025

What If Time Was a Physical Substance 2025

Imagine waking up in a world where time isn’t just something that passes — it’s something you can touch, bottle, and maybe even reshape. What if time was no longer an invisible force but a tangible substance with weight, color, and texture? In 2025, with rapid advances in quantum physics and metaphysical speculation, the concept of time as a physical substance is more fascinating — and hypothetically compelling — than ever before. In this exploration, we’ll dive deep into what it would mean if time were physical, how it might be manipulated, and what consequences such a reality could bring for humanity, physics, and even personal existence. Reimagining Time as a Tangible Entity Currently, time is one of the four dimensions of space-time, defined and measured but never physically touched. However, if time were a material substance — let’s say like water, gas, or light — it would drastically change how we understand everything from movement and aging to causality and energy. This shift would alter not only physics but also philosophy. We'd stop seeing time as a background stage on which events play out, and instead see it as a participant in those events. It could be mined, harvested, shaped, or stored. But how could such a concept exist in practice? Physical Properties of Time: What Might It Look Like? If we treat time as a substance, we must define its properties. Would it be a fluid, something you could pour? Or a gas, drifting invisibly but collectable with the right equipment? Could time exist in solid form — perhaps as crystal-like units, each representing a fixed moment? Some speculative physicists and science fiction writers imagine time as a luminous fluid that flows through space, while others picture it as a “fog” that thickens or thins depending on the gravitational field. In that view, being in a high-gravity area might feel like swimming through molasses-like time — movements slow, thought processes dragged. In contrast, low-gravity zones might feel like surfing a fast, lightweight stream of time. Such interpretations could help us physically explain phenomena like time dilation or time loops using substance-based analogies. Manipulating Time: Could We Build Time Machines? One of the most exciting possibilities in a world where time is physical is that it could be manipulated. If time were a harvestable or controllable resource, we might create technologies that allow us to speed it up, slow it down, or reverse it — not just metaphorically, but literally. Time machines would move beyond theory. Instead of warping space-time through gravity or velocity (as current theories suggest), we could invent “time engines” that displace or burn the physical substance of time to navigate through temporal dimensions. This concept may sound fantastical, but if time could be shaped or molded like clay, then moving to the past or future could become a question of applying force to that substance. Impacts on Daily Life and Human Experience A world where time is a substance would affect every part of human life: - Aging could be reversed or halted by slowing or isolating your personal “time field.” - People might store time in capsules to save moments for later or sell hours like currency. - Hospitals could give “time infusions” to patients to speed up healing. - Artists might sculpt with time to create living, moving works that evolve over weeks or centuries. This would also raise moral and ethical questions. Would the wealthy hoard time? Would stealing someone’s time be like robbing them of life itself? Could prisons stretch time to make a one-year sentence feel like 100? Scientific Parallels: Is There Any Basis? Although time isn't a substance according to current science, some advanced theories hint at related ideas. For instance, the block universe theory suggests that past, present, and future all exist simultaneously — as if they are laid out across space. Similarly, loop quantum gravity proposes that space and time are quantized at the smallest scale, made up of discrete units rather than being smooth and continuous. These approaches, while not stating that time is material, point toward a deeper structure — one that could theoretically behave in substance-like ways under extreme conditions, such as near a black hole or during the earliest moments of the universe.

Time Economics: Would We Spend, Save, or Trade It? The concept of time as a physical object opens up a new economy. Imagine a world where hours are traded like money, and days can be banked or borrowed. People might wear “temporal meters” on their wrists to monitor how much time they have left — a literal countdown to their end. Poorer communities might suffer from “temporal poverty,” experiencing days at half speed compared to the privileged. This would create an entirely new form of inequality, measured not by wealth or location, but by temporal access. We could even see a black market for smuggled time, stolen from other people or extracted from future timelines. The Consequences of Time Pollution or Misuse If time can be handled like a substance, it can also be contaminated, leaked, or corrupted. What would “time pollution” look like? Perhaps zones where time malfunctions — memories overlap, people age irregularly, or physical laws break down. Cities may implement time sanitation protocols, and accidents involving “time spills” could lead to chronal disorientation or even entire days looping indefinitely. This opens up a new field of “chronal engineering,” with experts who regulate and fix damaged time systems, much like IT technicians do with digital data today. Social and Psychological Impacts The human mind is built to perceive time linearly — birth to death, cause to effect. But in a world where time can be bent, twisted, and shaped, that sense could shatter. People might become lost in infinite loops of nostalgia. Others might skip through weeks at a time, blurring relationships and memory. Society could fracture between those who live at normal pace and those who manipulate time to slow their experience — living lifetimes in a single afternoon. This could also spark a rise in new religions or spiritual movements centered on mastering or respecting the flow of time as a sacred resource. Could We Ever Return to “Normal” Time? Once time becomes physical, could we ever go back to perceiving it as abstract? Probably not. Just like our concept of space forever changed after Einstein, a tangible time would permanently alter our view of existence. If everyone had control over their own personal time flow, collective experiences — watching a movie together, aging together, going to school in sync — might disappear. Society could become fragmented, like passengers on separate tracks, each hurtling through their own individualized chronologies. Final Thought: The Power and Peril of Tangible Time Making time a substance would empower us beyond imagination — healing wounds, extending life, even rewriting history. But it would also introduce dangers we've never faced: temporal inequality, timeline corruption, and existential breakdown. This speculative idea makes us reflect not just on the possibilities of future physics but also on how we value our minutes, our memories, and our shared journey through time. — 📚 Related Reading from Our Blogs: - What If Dreams Could Be Recorded and Played Back 2025 https://edgythoughts.com/what-if-dreams-could-be-recorded-and-played-back-2025 - What If We Found Proof of a Multiverse 2025 https://edgythoughts.com/what-if-we-found-proof-of-a-multiverse-2025 🔗 External Resource: You can read more about time as a physical quantity in the context of theoretical physics here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_in_physics Read the full article

#100#2025-01-01t00:00:00.000+00:00#2025https://edgythoughts.com/what-if-dreams-could-be-recorded-and-played-back-2025#2025https://edgythoughts.com/what-if-we-found-proof-of-a-multiverse-2025#ageing#alberteinstein#analogy#blackhole#blackmarket#blog#bottle#causality#clay#color#concept#corruption#countdown#currency#data#digitaldata#dimension#drag(physics)#dream#economicinequality#economics#economy#energy#engineering#eternalism(philosophyoftime)#ethics

0 notes

Video

youtube

Anak Panah Masa: Mengapa Masa Hanya Bergerak Ke Hadapan

Dive into the mysterious and fascinating concept of time! 🌌 In this video, we explore time's constant presence in our lives and ask why it flows in one direction. Journey through history with Newton's classical physics and Einstein's revolutionary theory of relativity. Discover how imaginary time and the weak anthropic principle shape our understanding of the cosmos, and delve into the psychological and thermodynamic arrows of time. From the expansion of the universe to the intricacies of human consciousness, join us in unraveling the profound mysteries of time.

Like and share the video to spread the knowledge!

#TimeMystery #Relativity #PhilosophyOfTime #Newton #Einstein #CosmicArrow #Thermodynamics #Consciousness #PhysicsExplained

OUTLINE:

00:00:00 The Arrow of Time: A Summary and Explanation 00:33:09 One Way or Two? 00:33:52 Time Marches On 00:34:36 Time Bends and Warps 00:37:20 A Different Dimension 00:40:11 Further Implications and Reflections on the Arrow of Time 00:44:27 Broken Cups and Nature's Disorder 00:45:03 From Order to Chaos 00:45:45 The Psychological Time 00:46:19 Expanding Universe, Cosmic Arrow 00:46:59 A Universe Still Unfolding 00:49:41 The Human Perspective

0 notes

Text

Understanding Singular Statements In Philosophy | PhilosophyStudent.org #shorts

Explore the concept of singular statements in philosophy – assertions uniquely tied to specific objects, persons, places, or times. Please Visit our Website to get more information: https://ift.tt/yMBgntE #singularstatement #philosophyinsights #philosophicalassertions #philosophyoftime #understandingphilosophy #shorts from Philosophy Student https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QxMPr77e7Xo

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Stanford Encyclopedia: Reichenbach Accessed 06/19/20

0 notes

Text

Hourglass 54 SPb Green Acrylic

The timeless in you is aware of life's timelessness. And knows that yesterday is but today's memory and tomorrow is today's dream. Kahlil Gibran

Hourglass 54 SPb Green Acrylic

Acrylic green hourglass Saint Petersburg on Prague

Hourglass 54 SPb Green Acrylic Hourglass Collection on MHC Virtual Museum We have more than 1000 objects in My Hourglass Collection Hourglass Collection, Collection catalog: Collection catalog 300-399Collection catalog 200-299Collection catalog 100-199Collection catalog 1-99Collection catalog, The List

Hourglass 54 Information about time tells the durations of events, and when they occur, and which events happen before which others, so time has a very significant role in the universe's organization. Nevertheless, despite 2,500 years of investigation into the nature of time, there are many unresolved issues. Hourglass – measurement device. An hourglass, sandglass, sand timer, or sand clock is a device used to measure the intervals of time. Hourglass 54 Philosophy of space and time is the branch of philosophy concerned with the issues surrounding the ontology, epistemology, and character of space and time. During the Age of Enlightenment (17th and 18th Century), early modern philosophy began once again to consider questions of whether time is real and absolute or merely an abstract intellectual concept that humans use to sequence and compare events. In the 19th Century, philosophers began to question whether the present was really an instantaneous concept or a duration, and the conventionalists and phenomenologists all made their own contributions to the debate on time.

Hourglass 54 SPb Green Acrylic Hourglass figure – Sophia Loren Hourglass Body Shapes The hourglass is one of four female body shapes Female body shape or female figure is the cumulative product of her skeletal structure and the quantity and distribution of muscle and fat on the body Masonic Hourglass – a symbol of the third Degree of Freemasonry peculiar to the American Rite. – Source: MasonicDictionary.com Masonry is a unique institution that has been a major part of community life in America for over 250 years. Masonry, or more properly Freemasonry, is America’s largest and oldest fraternity and one that continues to be an important part of many men’s personal lives and growth. Many years ago in England it was described as “a system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.” It is a course of moral instruction using both allegories and symbols to teach its lessons. The legends and myths of the old stonecutters and Masons, many of them involved in building the great cathedrals of Europe, have been woven into an interesting and effective way to portray moral truths. Read the full article

#Enlightenment#Hourglassfact#Philosophyofspace#Philosophyofspaceandtime#Philosophyoftime#PracticalPhilosophy#Prague#SaintPetersburg#SPb

0 notes

Video

instagram

The Physics of Time: What Is Time? "As quantum mechanics implies, the present moment you're experiencing now is best thought of as funneled from all your possible pasts as well as funneled from all you probable futures. Since time can't be absolute but is always subjective, D-Theory of Time, or Digital Presentism, revolves around observer-centric temporality. All realities are 'observer-centric virtualities' where an entire Observer-Universe system remains in the state of quantum coherence until experienced as a Conscious Instant, or the Temporal Singularity in the framework of D-theory of Time. A series of such conscious instants constitutes a data stream of consciousness. In a real sense, your consciousness is, in actuality, mind-based computing of your experiential branch in the Quantum Multiverse... Your sense of time flow is a sequential change between static perceptual frames, it's an emergent phenomenon, 'a moving image of eternity' as Plato famously said more than 2 millennia ago." -Excerpt from The Physics of Time: D-Theory of Time & Temporal Mechanics available now as eBook on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07S3QZPQT #PhysicsOfTime #DTheoryOfTime #TemporalMechanics #DigitalPresentism #TemporalPhysics #PhilosophyOfTime #TemporalPhilosophy #Fracta https://www.instagram.com/p/ByDxaeGg4D6/?igshid=1u2ey3mzcbigs

#physicsoftime#dtheoryoftime#temporalmechanics#digitalpresentism#temporalphysics#philosophyoftime#temporalphilosophy#fracta

0 notes

Photo

The latest episode of Free Association is up. Talking the history of time and some philosophy of time. Check it out o Apple, Spotify, Google, or Stitcher under “Free Association with Ben Vizy” 🎙⏱⏲ #benvizy #freeassociation #time #historyoftime #philosophyoftime #podcasting from #bouldercolorado (at Boulder, Colorado) https://www.instagram.com/p/BvCTgR3HzP7/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1r9m39u8omfh7

0 notes

Text

I am a memory growing ‘old’

As I sat on the edge of my bed, wrapped in a towel facing the mirror, I looked at my 23 year old body and studied my face. All this time gone, the time it took to get here, memories of experiences and relationships; exists only in my head. Did anything really happen the way I perceived it? Did any of it happen at all? The only evidence of time passing is my ageing body, yours and photographs. But what if ageing was just a warped filter we were taught to look through? It’s as if the only self we were taught to be conscious of was our physical one, decaying through linear time. I feel as though my consciousness is evolving and learning, though not ageing like my body. “Who I am” is just a memory of how I’ve responded to “events”.

When I was younger, I would fantasise about what it would be like to be a certain age, which most people do. But now that I am that age, I have come to realise that we are not however many years old. We are merely a moment, whichever moment that may be, in time. A blink, as some have coined it. And since to remember a moment it needs to have passed, to remember “who we are” it needs to have been us at one point- this is why we are just a memory. Time is strange, it takes so long and it goes so fast, and once you’ve spent it you can never get it back. A physical moment dissolves into a clump of words and images and opinions and feelings. So tangible, malleable, and out of control. I can’t help but feel that in order to upkeep who I think I am, I need to be recreating that version of myself in every waking moment.

0 notes

Text

A Journey Through Time

Time, the ever-flowing river that carries us from one moment to the next, has fascinated humanity for centuries. What if we could navigate its currents, dipping into the past or hurtling towards the future? The concept of time travel has long captured our collective imagination, inspiring countless works of science fiction. While we have yet to build a functioning time machine, let's embark on a thrilling exploration of the hypothetical possibilities and philosophical implications of traveling through time. After reading the majority of books from Dr Michio Kaku (Michio Kaku is an American physicist, science communicator, futurologist) over the years it does lead to the main inspiration for this blog.

Theoretical Framework:

Time travel, as envisioned by physicists and scientists, often involves bending the fabric of spacetime. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity opened the door to such speculations, suggesting that gravity could influence the passage of time. Wormholes, black holes, and cosmic strings have all been proposed as potential conduits for temporal voyages. While these concepts remain firmly in the realm of theoretical physics, they ignite our curiosity and challenge our understanding of the universe.

The Past Beckons:

Imagine strolling through the bustling streets of ancient Rome, witnessing the construction of the pyramids, or experiencing the Renaissance firsthand. The allure of visiting historical epochs is undeniable, allowing us to witness pivotal moments, meet historical figures, and gain a deeper understanding of our cultural heritage. However, the prospect of altering the past raises profound ethical questions — do we observe quietly or intervene to shape a different future?

The Butterfly Effect:

In chaos theory, the "butterfly effect" posits that a small change in one part of a system can have far-reaching consequences. Applying this concept to time travel, even the slightest interference in the past could lead to unforeseen and potentially catastrophic outcomes in the present and future. This raises questions about the responsibility and consequences of our actions across time.

The Uncertainty of the Future: Venturing into the future holds its own set of enigmas. Will we find a utopian society or a dystopian nightmare? The uncertainties of what lies ahead raise philosophical questions about determinism versus free will. If we can glimpse our future, can we alter its course, or is our fate predestined?

Temporal Paradoxes:

Time travel often comes with its fair share of paradoxes, such as the famous grandfather paradox. If you were to travel back in time and inadvertently prevent your grandparents from meeting, would you cease to exist? These paradoxes challenge our understanding of causality and create fascinating intellectual puzzles.

While time travel remains a tantalising concept that captivates our imaginations, it also serves as a rich source of philosophical inquiry.

Whether exploring the past to understand our roots or peering into the future to contemplate our destiny, the notion of temporal travel raises profound questions about the nature of time, causality, and our place within the vast tapestry of existence.

Until science catches up with our dreams, we can continue to marvel at the mysteries of time and savour the adventures that unfold within the pages of science fiction. Ever since the days of 2006 when I watched the documentaries of Dr Michio Kaku. I have always been fascinated by the topic of time and I probably always will be.

#TimeTravel#TemporalExploration#SciFiAdventures#Wormholes#TheoreticalPhysics#ButterflyEffect#PhilosophyOfTime#HistoricalJourney#FutureUnknown#TemporalParadox#EinsteinTheory#SpacetimeContinuum#TimeMachineDreams#CausalityDilemmas#ChronoWonders#TimeTraveler#GrandfatherParadox#TemporalMysteries#TimeBending#TemporalEthics#Dr Michio Kaku#back to the future#today on tumblr#deep thoughts#deep thinking#new blog

0 notes

Text

youtube

"The Future That Never Arrives""Explore the timeless mystery of past, present, and future in this thought-provoking video. Delve into philosophical insights on whether the future truly exists, the fleeting nature of the present, and the enduring impact of the past. A journey into time's interconnectedness, ethics, and the legacy we leave for generations to come."

#PhilosophyOfTime FutureExists EthicsAndTime PastPresentFuture PhilosophicalThoughts TimeMysteries EternalNow DeepThinking Legacy#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Craig's Confusion: McTaggart's Paradox and Presentism

McTaggart’s argument for the unreality of time has has occupied the attention of many philosophers of time since its publication in 1908. While few today accept the soundness of the argument in its entirety, his categorization of the serial conceptions of time into what he called, rather blandly, A-Series and B-Series, have been almost universally adopted. An A-Series is a tensed, dynamic series of time, in which the positions run from the past, to the present, and to the future. The B-Series, on the other hand, is a tenseless, static time series, in which positions run from “earlier to later” (McTaggart 1908). Broadly, McTaggart’s argument has two basic parts; firstly, he shows that the A-Series is the only true time series, and then, secondly, he proceeds to show the A-Series to be incoherent, leading to his famous conclusion that time does not exist. We will here briefly outline both of these parts, and then assess a popular criticism of the argument.

McTaggart begins his proof by outlining two basic intuitions about the nature of time; (1) that time involves change, and (2) that time has a direction. The B-Series certainly accommodates the latter of these intuitions, but it is not clear whether it can account for real change. Perhaps change occurs in the B-Series when one event stops, and another starts - but the B-Series involves an eternally ordered set; events can not simply ‘pop in’ or ‘pop out’ of the series! Perhaps then, the change occurs when two events overlap in time. The same problem, however, reoccurs here; while two events can have a common element, they can not be the same event, for this would preclude the possibility of change. If some event M changes into some other event N, M has ceased to be M and N has become to be N - but as we have already seen, no event can begin or cease to be in the B series. Hence, the B-Series cannot account for change.

The A-Series, on the other hand, involves both direction and change; events in the A-Series change from being future, to being present, and then become past - therefore making it a true time series. However, according to McTaggart, on closer inspection the A-Series appears to be incoherent. If we take the A-properties of “being past” or “being present” or “being future” in the A-Series as being non-relational, then every event simultaneously has all three of these contradictory properties, as every event will be past, present or future at some point in the series. Of course, we know that an event cannot be past, present and future all at once; events travel from ‘being future’ to ‘being present’, then to ‘being past’ - but this is a vicious circle, as it assumes the existence of time in order to make sense. Perhaps then, our A-properties are relational to something - the present. But by what virtue do we take a certain event to be present? Perhaps it is that a present event will have the A-property of being present - but if this is the case, all events would have this property, as all events are/will present at some point. It would seem that the relational point needs to exist outside the A-Series. With this in mind, we could posit another A* Series that gives a special property to present events. But again, all events would have this property, so another A** Series would be needed, and so on ad infinitum. So, McTaggart concludes, as the A-Series is the only true theory of time (because it accommodates both of our intuitions about time, while the B-Series cannot), and the A-Series is incoherent, and these exhaust the options, therefore time does not exist.

Most attempts to refute McTaggart’s argument have either involved accepting his first premise (that the A-Series is the only true time series) while denying the second (that the A- Series is incoherent - also known as McTaggart’s paradox), or denying the first while maintaining the second. One instance of the former has been posited by William Lane Craig and Robin DePoidevin, who point out that McTaggart may not be attacking the A-Theory at all in the second part of his argument, but rather a hybrid A-B Theory, which “combines tenseless ontology with temporal intrinsic properties of tense” (Craig 2001). Although this seems to be an odd objection (McTaggart defined our terms, after all), McTaggart does seem to implicitly maintain that any series of time must always include some kind of B-Theoretic event ontology; an eternally indexed, tenseless series of events. An A-Theory of this kind certainly exists; the moving spotlight A-Theory combines the B-Ontology of eternalism with a privileged present and thus tense, and hence falls easily for McTaggart’s paradox. However, as the paradox relies on “an event ontology of tenselessly existing events” (DePoidevin 1991), an A-Theory that has no such B-Ontology - such as presentism - would never see it arise. On presentism, the relational point of the present is easily defined, as present events are the only events that exist. This eliminates the need for a relational point outside of the A-Series, thus avoiding the infinite regress of A* Series’ that follow in the paradox.

Nathan Oaklander has disputed this point, however, pointing out that Craig appeals to tensed possible successive worlds¹ which “did, do or will obtain” to justify his talk about events having existed in the past (Oaklander, 1999, emphasis mine) - that is to say, that the past and the future exist in some sense, but only obtain as they become present. This, however, obviously begs the B-theoretical concept of succession; past and future events still exist both tenselessly and in an eternal relation on this view, even if they are abstract objects. With this in mind, Craig’s view of presentism seems to be little more than a hybrid A-B Theory - a group which he himself claims are ‘in deep trouble’ with regard to the paradox (Craig 1998).

This is not to say that every presentist is committed to a B-ontology in this way. Oaklander points out that Prior, Levison and Christensen - presentists, of whom Craig counts himself alongside - all reject B-ontology in favor of a ‘pure A-Theory’ of presentism. According to Oaklander, their presentism differs from Craig’s, in that they “... reject an ontology that includes events, they reject the property of presentness that events acquire and shed, and most importantly, they reject the notion that there is a genuine change that an event, or anything else, undergoes as it becomes present and recedes into the past” (Oaklander 1999). Prior explicates this in his (1968), claiming that “... what looks like talk about events is really at bottom talk about things, and that what looks like talk about changes in events is really just slightly more complicated talk about changes in things.” (Prior 1968:10). The flow of time, he thus claims, is “merely metaphorical, not only because what is meant by it isn’t a genuine movement, but further because what is meant by it isn’t a genuine change” (Prior 1968:11).

By denying that temporal becoming involves change, this form of presentism adriotly avoids McTaggart’s paradox, as it denies the existence of the A-properties ‘past’, ‘present’ and ‘future’ that events gain and shed. It does not, however, avoid the first premise of his argument, as it flatly denies McTaggart’s first intuition about time; that time involves change. This is because, as Oaklander points out, on a pure A-Theory of presentism, “... there are only individual things and the present tensed facts that such individuals or substances enter into” (Oaklander 1999). By McTaggart’s lights, this “pure A-theory” would not be a true time series at all, for exactly the same reason that initially disqualified the B-Series.

By way of summary, we have assessed two unsuccessful strategies that presentists have deployed to avoid McTaggart’s argument for the unreality of time; to either reject B-ontology completely in favour of a ‘pure A-theory’ that denies temporal becoming as a species of change, and thus disqualify itself in the first premise of McTaggart’s argument, or, in an effort to make sense of talk about past and future events, accept a hybrid A-B theory that rests (in some capacity) on B- ontology, and in doing so become subject to McTaggart’s paradox in his second premise. Of course, this does not prove presentism or the A-series as a whole to be necessarily inconsistent; one could certainly reject McTaggart’s intuitions about time, or attack his argument in other ways than which we have discussed, but, as we have seen, either disposition of presentism cannot completely avoid McTaggart’s argument, as it has been claimed.

Notes

¹ Meant in the serious actualist sense. Oaklander: '... states of affairs which exist as abstract objects but which are not instantiated' (Oaklander, 1999)

References

Craig, W. L. 1998. McTaggart’s Paradox and the problem of temporary intrinsics. Analysis 58: 122–27.

–––––. 2001. McTaggart's Paradox and Temporal Solipsism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 79, Iss. 1

LePoidevin, Robin. 1991. Change, Cause and Contradiction: A Defense of the Tenseless Theory of Time. London: Macmillan.

McTaggart, John Ellis. 1908. The Unreality of Time. Mind: A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy 17: 456-73.

Oaklander, L. N. 1996. McTaggart’s Paradox and Smith’s tensed theory of time. Synthese 107: 205–21

–––––. 1999. Craig on McTaggart’s Paradox and the problem of temporary intrinsics. Analysis 59: 314.

Prior, A. N. 1968. Changes in events and changes in things. Time and Tense. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Arrow of Time: Why Time Only Moves Forward

Dive into the mysterious and fascinating concept of time! 🌌 In this video, we explore time's constant presence in our lives and ask why it flows in one direction. Journey through history with Newton's classical physics and Einstein's revolutionary theory of relativity. Discover how imaginary time and the weak anthropic principle shape our understanding of the cosmos, and delve into the psychological and thermodynamic arrows of time. From the expansion of the universe to the intricacies of human consciousness, join us in unraveling the profound mysteries of time.

Like and share the video to spread the knowledge!

#TimeMystery #Relativity #PhilosophyOfTime #Newton #Einstein #CosmicArrow #Thermodynamics #Consciousness #PhysicsExplained

OUTLINE:

00:00:00 The Arrow of Time: A Summary and Explanation 01:29:18 One Way or Two? 01:29:56 Time Marches On 01:30:30 Time Bends and Warps 01:32:46 A Different Dimension 01:35:20 Further Implications and Reflections on the Arrow of Time 01:39:08 Broken Cups and Nature's Disorder 01:39:40 From Order to Chaos 01:40:18 The Psychological Time 01:40:51 Expanding Universe, Cosmic Arrow 01:41:29 A Universe Still Unfolding 01:43:47 The Human Perspective

0 notes