#People with Disabilities

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Before you say no duh, remember that we need studies like this to quantify things for planning, government policy, and court cases, and also to help convince people who's minds aren't already made up.

I know I struggle to breath in heat like this, and hypoxia kills, especially when cars are involved.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Giles

14 Holy Helpers

650-710

Feast day: September 1

Patronage: people with disabilities, the poor, cancer patients, difficulty breastfeeding, mental illness, sterility, depression, childhood fears, convulsions, Edinburgh, Scotland

Originally from Greece, St. Giles lived as a hermit in the forest of France for many years and his sole companion was a deer who is said to have sustained him with her milk. When King Wamba's hunters pursued and shot at the deer, the arrow wounded St. Giles instead, making him the patron of cripples. As compensation, the King gave Giles a piece of land in the Provence, on which Giles founded a monastery. He died with the highest repute for sanctity and miracles.

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase here: (website)

#St Giles#people with disabilities#Patron of the poor#paron of mental illness#catholic saint#portraitsofsaints

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

explained to my daughter at the grocery store that the little girl that walked by with two arm braces for walking was using them like I use my cane

Her first concern: “mama does that mean BOTH her legs hurt?!”

Second concern: “why doesn’t she have stickers on her canes? Can I give her some stickers?” (She put some on mine) (we had none to offer and she was very sad)

Third: “Momma why can’t you have a purple cane like hers, I like purple better.” (Mine is black, she is offended)

#mushroomwillow rambles#chronic illness#physically disabled#kids with disabilities#people with disabilities#physical disability#disability aids

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The X-Men as an Allegory for People with Disabilities: Why Logan (Wolverine) Represents Our Struggle

Mutants in the X-Men universe have long been recognized as an allegory for various marginalized groups. Often, people discuss them as symbols for race, gender identity, or sexuality, and while these are all valid and essential interpretations, there’s another group that rarely gets the same attention: people with disabilities. At their core, the X-Men represent those who society deems "different," and their struggles mirror the everyday realities of disabled people who face prejudice, violence, and the overwhelming sense that they don’t fit in.

In this post, I want to dive into why Logan (Wolverine)—arguably the most beloved X-Men character—is such a poignant representation of this struggle. Logan’s experiences aren’t just about mutant oppression; they reflect the same violence, exclusion, and dehumanization that so many people with disabilities have endured throughout history. His pain resonates on a deeply personal level because he embodies the way disability can isolate, alienate, and force individuals to question their humanity.

Logan: Beaten Down, Like So Many Others

Logan’s story is filled with unimaginable suffering, much of it inflicted because of his mutation. From being experimented on in the Weapon X program to living through countless wars and battles, Logan has been beaten down—physically and mentally—time and time again. He’s been tortured, treated like an animal, and used as a tool by people who see his mutation as nothing more than a resource to exploit. This is painfully similar to the way people with disabilities have been treated throughout history.

From early eugenics movements to the horrific medical experiments performed on disabled individuals, society has frequently viewed people with disabilities as "less than human," as subjects for abuse or as problems to be solved. Logan’s life, constantly fleeing, hiding, and surviving these abuses, reflects the lived reality of countless disabled people who have been denied their basic humanity.

The Alienation of Feeling Like an Animal

One of the most striking aspects of Logan’s character is how he struggles with feeling like he doesn’t belong. His mutation, which gives him heightened senses, superhuman strength, and animal-like reflexes, also makes him feel less than human. His feral rage, his sharpened claws, and his ability to endure pain make him question whether he’s more beast than man. This deep feeling of alienation is something many people with disabilities understand all too well.

Disabled people are often made to feel like outsiders, whether through physical inaccessibility, social exclusion, or the ways society "others" their existence. Logan’s sense of not belonging, of feeling out of place in the world and within his own skin, mirrors the internal struggles that people with disabilities often face. His story isn’t just one of physical power—it’s about the mental toll of constantly being made to feel like you’re different, and not in a way that’s celebrated, but in a way that isolates.

Physical Power vs. Internal Pain

While Logan is incredibly strong and seemingly indestructible, his true power isn’t his healing factor or his claws—it’s his ability to keep going despite the weight of his internal pain. This is one of the reasons so many people relate to him. People with disabilities are often portrayed in media as weak or fragile, but in reality, they possess immense strength to survive in a world that isn’t built for them. Logan, too, represents this paradox: physically invincible but emotionally scarred.

In the same way that disabled people have to fight for basic rights, recognition, and acceptance, Logan fights for a place in the world. His physical toughness often hides his internal vulnerability, but those who look closely can see the emotional scars he carries—the loss, the trauma, the battles that never seem to end. These scars make him relatable to anyone who’s been made to feel different or "less than" by society.

The Fight for Recognition

Logan, like all mutants, is constantly fighting for recognition—fighting for the right to exist, to be treated as more than a weapon or a threat. People with disabilities face this same struggle. Whether it’s fighting for accessibility, equal opportunities, or even the right to be seen as full people rather than their disabilities, the fight for recognition is ongoing. Logan’s story reminds us that the battle for acceptance is exhausting but necessary, that fighting for one’s humanity is a lifelong journey.

Conclusion: Logan as an Icon of Resilience

What makes Logan’s story so powerful is that, despite all the violence, abuse, and isolation, he never gives up. He’s survived things no one should have to endure, and though he’s scarred, broken, and often cynical, he continues to protect those he cares about. He becomes a mentor to younger mutants, helping them navigate a world that sees them as dangerous or inferior. In this way, Logan’s journey is one of resilience—a testament to the strength it takes to survive in a world that doesn’t always see you as fully human.

People with disabilities can see themselves in Logan because his story is one of constant struggle, of surviving in a world that wasn’t made for him, and of pushing forward despite the pain. He’s not just a superhero with claws and a healing factor—he’s a symbol of the fight for dignity and recognition that so many of us face every day.

Logan’s story shows us that even when the world beats you down, when society tries to strip you of your humanity, there’s power in resilience. There’s strength in continuing to fight for your place in the world. That’s why people with disabilities—myself included—find a part of ourselves in Logan.

#hugh jackman#wolverine#xmen#x men#allegory#disability#disability awareness#essay#marvel#people with disabilities

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

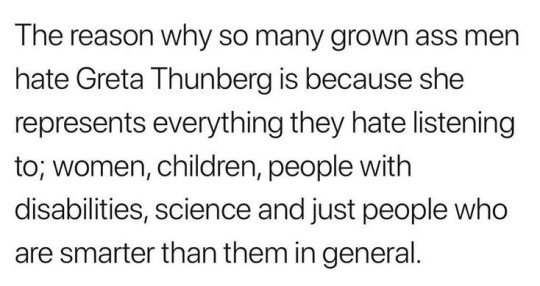

#climate change#human rights#feminism#activism#greta thunberg#women#children#people with disabilities#feminist#climate activism#climate action now#climate action#climate activst#not mine

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi guys! This post is not related to arts, but I will be very grateful to you for sharing it.🌸

This is a survey for my university's research. I study the problems of disabled people in tourism and recreation. This survey is anonymous.

The statistics collected in the surveys will be used for my university project.

I will be very grateful to everyone who completes the survey and sends it to their family members or friends✨️

The more people complete the survey, the more detailed statistics i will get, so it is important to spread it as much as possible.

You can scan it or use links below:

Ukrainian 🇺🇦

English 🇬🇧

Polish 🇵🇱

#tourism#parks and recreation#people with disabilities#university project#disability#disabled#disabilties#accesibility#chronic illness#hard of hearing#sensory disability#physical disability#physically disabled#mental disability#intellectual disability#developmental disabilities#cognitive disability#visual impairment#legally blind#mobility aid#hearing loss#hearing impaired#speech impediment#hearing aids#hearing issues

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using mobility aids as a young person is having kids walk in front and run into them.

For some reason parents will often not correct their kids and leave it to me to either:

a) move my mobility aid out the way of their child

or

b) wack their child with my mobility aid

PLEASE teach your kids to make extra space for people using mobility aids, even if the person using them is a young person.

#physically disabled#disability#hypermobile ehlers danlos#heds#mobility aid user#young disabled person#people with disabilities#hypermobile eds#heds tag#disabled#disabled problems

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Share to keep her memory alive

This is Ruth, a 16 years old teenager with physical and intellectual disability. Like many in her age, she liked to dance and meet new friends. Her dad, Arik, took her to parties and raves.

In the picture: Ruth and her dad in a rave.

They were at the Nova festival during the Black Saturday of 07/10.

When the shooting started, Arik took Ruth in his arms, leaving behind her wheelchair, and ran for their lives. He refused to leave her behind.

The wheelchair was found burnt about a week ago, but there was no sign of Ruth and Arik.

We prayed for good news. For them to be found - wounded, kidnapped, but alive.

I got the news last night.

Their bodies were identified yesterday. They were buried today.

And I'm asking - you say it was done for freedom.

Yes, I remember the last time people with disabilities died for "freedom"

(somehow, we are never part of it)

#disability#hamas is isis#actually disabled#israel#palestine#hamas#gaza#i/p#i/p conflict#free gaza from hamas#antisemitism#jumblr#eugenics#disabled#disabled murder#people with disabilities#i'm sad#ruth#Ruth Perez#remember their names#keeping the memory alive

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lois Curtis

Disability rights activist Lois Curtis was born in 1967 in Atlanta, Georgia. Curtis, who had been diagnosed with developmental disabilities and schizophrenia, was confined to a Georgia institution. She nonetheless advocated for herself, calleing attorneys and social workers asking for help to leave the state hospital. In 1995, with the help of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, she filed a case that went all the way to the US Supreme Court. In 1999, the Supreme Court ruled in Curtis' favor in the landmark case, Olmstead v LC, determining that unjustified segregation of people with disabilities violated the Americans with Disabilities Act. After leaving the hospital and going to live in the community, she became a visual artist.

Lois Curtis died in 2022 at the age of 55.

Image source: The White House

#disability rights#women with disabilities#people with disabilities#black women#black history#disability history#women's history

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

#invisible disabilities#hidden disabilities#people with disabilities#hiddendisability#hidden disability

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Washington Voters Please Vote NO on all state initiatives

There are a bunch of dangerous initiatives on the ballot this year. A hedge fund manager is trying to gut things for tax cuts for the rich and it will ruin our state.

I-2066 guts clean energy

I-2109 cuts taxes for the rich

I-2117 kills the climate Commitment act, increasing pollution, gutting infrastructure funding, etc.

I-2124 kills long term care funding for elderly and disabled people.

Please Signal Boost this. Ballots will arrive shortly!

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

#love having this problem at 26#I mean it started before that but#eye problems#eye disability#seeing disability#disabilties#disabled#legally half blind#half blind#only one working eye#i’m too old for this#people with disabilities#meme#we’re in this together besties#actually disabled#disabled eye#partially blind#vision impaired

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh my gosh people. woah, just wow.

like it's amazing the beautiful variety there is to you all, from queer people to neurodivergent people to therians and otherkins, systems, people of completely different cultures and personalities, people simply loving other people just for existing, people sharing memes with each other because they think they might like it, or sending messages or talking because the other person merely exists, just wow. people. they bring me to tears for just existing

#idk what to tag this as#love#I love people#all people#and things in the flesh of people#multiple people in the body of one#people with disabilities#trans people#gnc people#I love you all#I love you all so so much

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#epilepsy#epilepsy awareness#seizure disorder#seizures#disabilities#people with disabilities#disability#disability awareness#seize the day#epilepsy warrior

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Life Is Like When Your Brain Can't Recognize Faces

The common neurological disorder affects roughly 2 percent of the population. Author Sadie Dingfelder shares her perspective navigating the world with it.

— By Sadie Dingfelder | August 6, 2024

An illustration adds an abstract look on top of a photo of author Sadie Dingfelder. Illustration By Matthieu Bourel, Photo By Oxana Ware

Fifteen pairs of eyes stared into the gloaming. An hour passed before someone spied the faintest wisp of smoke on the horizon. The wisp drew closer, becoming something larger, winged, and muscular: sandhill cranes the color of storm clouds, save for their smart red caps. They swirled around our bird blind, a converted shipping container set into the riverbank to hide us from the cranes, and dropped out of the sky in groups of two or three or five, landing gently in the Platte River in central Nebraska.

“It looks like one big mass of birds,” explained our guide from a conservation group called the Crane Trust. “But they actually stay in family groups for their entire migration.”

“How do they keep track of their mates?” I asked.

“They look alike to us, but I bet they look different to each other,” replied a woman in a green coat. I turned away from the birds to study her face. She had wide-set eyes, a ski jump nose, and short gray hair. Was she the same woman I was chatting with on the van ride here, the one who showed me pictures of her dogs?

She was flanked by two similar looking women, and all three were traveling with their own mates—men who were, to me, interchangeably outdoorsy, middle-age, and white. After the cranes melted into the inky darkness, we humans filed silently out of the blind and trekked across a muddy field, our careful footfalls drowned out by a choir of chirping frogs.

Back in the dining hall, we sat speechless, some of us near tears at the beauty we’d seen. As we began to put our collective wonderment into words, I noticed many of my fellow “craniacs” (our term for crane enthusiasts) were calling me by name. It wasn’t strange by any means. After all, we’d spent the past six hours together, chatting over drinks, getting settled in our cabins, and then packing ourselves tightly into vans. But, hard as I tried, I couldn’t draw forth any of their faces or names.

To my eye, humans are nearly as interchangeable as cranes, and I only recently discovered why. I have a neurological disorder known as prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Some people end up with this condition through brain injury, but most cases are genetic in origin—and this version, known as developmental prosopagnosia, affects 2 to 2.5 percent of the population. It touches nearly every aspect of our lives, from dating to networking to making friends, and yet it goes largely undiagnosed. This is because, like most people, folks with face blindness assume that everyone else sees the world the same way as we do. We don’t realize that other people perceive faces as distinctive and highly memorable. A case in point: Bill Choisser, who coined the term “face blind” in the late ’90s, once asked his partner, “Why do TV shows have so many close-ups of actors’ faces? How are we supposed to tell them apart if we can’t see their clothes?”

As a kid, all I knew was that I couldn’t seem to make any friends. I’d hit it off with someone one day and then treat them like a stranger the next. I later found out that my classmates, quite reasonably, thought that I was aloof, or weirdly hot and cold. To fend off loneliness, I would read constantly, usually series like The Baby-Sitters Club or Sleepover Friends. I dreamed of having not just one pal but many. I yearned for the safety of a flock.

In college I abruptly switched strategies—from treating everyone like a stranger to treating everyone like a friend. Walking to class, I’d stop and chat with anyone who so much as glanced my way. It was, I thought, a major improvement. So it went for another 20 years. I knew everyone without really knowing anyone, save a handful of best friends and a boyfriend, all of whom tended to be visually distinctive, or at least very loud. It never occurred to me that this might be a strange way to live.

Not long after I turned 39, I began writing down funny stories from my life, pushing to meet a personal deadline to write a book by 40. Since I was working at the Washington Post at the time, I sent drafts to friends who also happened to be award-winning journalists. They had questions: Why are you always lost? Why do you regularly have no idea who you are talking to? Why is your life shot through with so much ambiguity and confusion?

Other people might have consulted a neurologist, but as a science writer, my first instinct was to sign up for studies. One, run by researchers at Harvard, involved brain scans followed by nearly 30 hours of intensive face-recognition training. My scores in the program improved, but whatever skills I learned during the exercises did not translate to real life. Somehow, I figured out a work-around for tests that were all but impossible given my unusual brain—and this is how I (and most face-blind people) get through life. We figure it out. We adapt.

This is also true for the sandhill cranes. When humans replaced wetlands with farmlands, the birds adapted their diet to include crops like corn. The sandhills, however, are uncompromising in at least one regard: They need wide, shallow waterways to roost in—and that’s why, during much of the year, Crane Trust staff mow down saplings and prevent shrubbery from rooting along the riverbanks. As a result of this adaptability and assistance, sandhill crane populations have been steadily increasing every year.

While I don’t require much accommodation these days, except for the occasional name tag, I do worry about all the lonely face-blind kids out there—as well as people who have other neurological differences. What could we as a society do to make the world more hospitable to the largely unacknowledged diversity of human brains and minds? Where should we be clearing riverbanks?

It was late when we got back to our cabins, but I was still curious about the cranes. I skimmed a few papers before going to bed, and I discovered that cranes probably do look alike, even to each other. But their calls are distinctive. Each bird has its own signature sound, and their voices can carry for miles. This is how cranes keep track of their family members throughout their migration—not with their eyes but their ears.

I should have known. While the cranes looked the same to me, I noticed one particular bird that stretched its neck long and made a sound like an angry clarinet. “It looks like he doesn’t like where his family has roosted,” my friend in the green jacket observed. It was impossible to know, but I suspected she was right. The world is a cacophony of consciousnesses, all so different from your own. But sometimes, if you’re quiet, perceptive, and lucky, you can hear another singular voice piping through the din. I drifted to sleep that night feeling a deep kinship with the cranes, comforted by the knowledge that while my vision may sometimes fail me, my curiosity never will.

2 notes

·

View notes