#Palliative Care

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

America's largest hospital chain has an algorithmic death panel

It’s not that conservatives aren’t sometimes right — it’s that even when they’re right, they’re highly selective about it. Take the hoary chestnut that “incentives matter,” trotted out to deny humane benefits to poor people on the grounds that “free money” makes people “workshy.”

There’s a whole body of conservative economic orthodoxy, Public Choice Theory, that concerns itself with the motives of callow, easily corrupted regulators, legislators and civil servants, and how they might be tempted to distort markets.

But the same people who obsess over our fallible public institutions are convinced that private institutions will never yield to temptation, because the fear of competition keeps temptation at bay. It’s this belief that leads the right to embrace monopolies as “efficient”: “A company’s dominance is evidence of its quality. Customers flock to it, and competitors fail to lure them away, therefore monopolies are the public’s best friend.”

But this only makes sense if you don’t understand how monopolies can prevent competitors. Think of Uber, lighting $31b of its investors’ cash on fire, losing 41 cents on every dollar it brought in, in a bid to drive out competitors and make public transit seem like a bad investment.

Or think of Big Tech, locking up whole swathes of your life inside their silos, so that changing mobile OSes means abandoning your iMessage contacts; or changing social media platforms means abandoning your friends, or blocking Google surveillance means losing your email address, or breaking up with Amazon means losing all your ebooks and audiobooks:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

Businesspeople understand the risks of competition, which is why they seek to extinguish it. The harder it is for your customers to leave — because of a lack of competitors or because of lock-in — the worse you can treat them without risking their departure. This is the core of enshittification: a company that is neither disciplined by competition nor regulation can abuse its customers and suppliers over long timescales without losing either:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/21/potemkin-ai/#hey-guys

It’s not that public institutions can’t betray they public interest. It’s just that public institutions can be made democratically accountable, rather than financially accountable. When a company betrays you, you can only punish it by “voting with your wallet.” In that system, the people with the fattest wallets get the most votes.

When public institutions fail you, you can vote with your ballot. Admittedly, that doesn’t always work, but one of the major predictors of whether it will work is how big and concentrated the private sector is. Regulatory capture isn’t automatic: it’s what you get when companies are bigger than governments.

If you want small governments, in other words, you need small companies. Even if you think the only role for the state is in enforcing contracts, the state needs to be more powerful than the companies issuing those contracts. The bigger the companies are, the bigger the government has to be:

https://doctorow.medium.com/regulatory-capture-59b2013e2526

Companies can suborn the government to help them abuse the public, but whether public institutions can resist them is more a matter of how powerful those companies are than how fallible a public servant is. Our plutocratic, monopolized, unequal society is the worst of both worlds. Because companies are so big, they abuse us with impunity — and they are able to suborn the state to help them do it:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/testing-theories-of-american-politics-elites-interest-groups-and-average-citizens/62327F513959D0A304D4893B382B992B

This is the dimension that’s so often missing from the discussion of why Americans pay more for healthcare to get worse outcomes from health-care workers who labor under worse conditions than their cousins abroad. Yes, the government can abet this, as when it lets privatizers into the Medicare system to loot it and maim its patients:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-01-patient-zero-tom-scully/

But the answer to this isn’t more privatization. Remember Sarah Palin’s scare-stories about how government health care would have “death panels” where unaccountable officials decided whether your life was worth saving?

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26195604/

The reason “death panels” resounded so thoroughly — and stuck around through the years — is that we all understand, at some deep level, that health care will always be rationed. When you show up at the Emergency Room, they have to triage you. Even if you’re in unbearable agony, you might have to wait, and wait, and wait, because other people (even people who arrive after you do) have it worse.

In America, health care is mostly rationed based on your ability to pay. Emergency room triage is one of the only truly meritocratic institutions in the American health system, where your treatment is based on urgency, not cash. Of course, you can buy your way out of that too, with concierge doctors. And the ER system itself has been infested with Private Equity parasites:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/17/the-doctor-will-fleece-you-now/#pe-in-full-effect

Wealth-based health-care rationing is bad enough, but when it’s combined with the public purse, a bad system becomes a nightmare. Take hospice care: private equity funds have rolled up huge numbers of hospices across the USA and turned them into rigged — and lethal — games:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/26/death-panels/#what-the-heck-is-going-on-with-CMS

Medicare will pay a hospice $203-$1,462 to care for a dying person, amounting to $22.4b/year in public funds transfered to the private sector. Incentives matter: the less a hospice does for their patients, the more profits they reap. And the private hospice system is administered with the lightest of touches: at the $203/day level, a private hospice has no mandatory duties to their patients.

You can set up a California hospice for the price of a $3,000 filing fee (which is mostly optional, since it’s never checked). You will have a facility inspection, but don’t worry, there’s no followup to make sure you remediate any failing elements. And no one at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services tracks complaints.

So PE-owned hospices pressure largely healthy people to go into “hospice care” — from home. Then they do nothing for them, including continuing whatever medical care they were depending on. After the patient generates $32,000 in billings for the PE company, they hit the cap and are “live discharged” and must go through a bureaucratic nightmare to re-establish their Medicare eligibility, because once you go into hospice, Medicare assumes you are dying and halts your care.

PE-owned hospices bribe doctors to refer patients to them. Sometimes, these sham hospices deliberately induce overdoses in their patients in a bid to make it look like they’re actually in the business of caring for the dying. Incentives matter:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/12/05/how-hospice-became-a-for-profit-hustle

Now, hospice care — and its relative, palliative care — is a crucial part of any humane medical system. In his essential book, Being Mortal, Atul Gawande describes how end-of-life care that centers a dying person’s priorities can make death a dignified and even satisfying process for the patient and their loved ones:

https://atulgawande.com/book/being-mortal/

But that dignity comes from a patient-centered approach, not a profit-centered one. Doctors are required to put their patients’ interests first, and while they sometimes fail at this (everyone is fallible), the professionalization of medicine, through which doctors were held to ethical standards ahead of monetary considerations, proved remarkable durable.

Partly that was because doctors generally worked for themselves — or for other doctors. In most states, it is illegal for medical practices to be owned by non-MDs, and historically, only a small fraction of doctors worked for hospitals, subject to administration by businesspeople rather than medical professionals.

But that was radically altered by the entry of private equity into the medical system, with the attending waves of consolidation that saw local hospitals merged into massive national chains, and private practices scooped up and turned into profit-maximizers, not health-maximizers:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-02-qa-corporate-medicine-destroys-doctors/

Today, doctors are being proletarianized, joining the ranks of nurses, physicians’ assistants and other health workers. In 2012, 60% of practices were doctor-owned and only 5.6% of docs worked for hospitals. Today, that’s up by 1,000%, with 52.1% of docs working for hospitals, mostly giant corporate chains:

https://prospect.org/health/2023-08-04-when-mds-go-union/

The paperclip-maximizing, grandparent-devouring transhuman colony organism that calls itself a Private Equity fund is endlessly inventive in finding ways to increase its profits by harming the rest of us. It’s not just hospices — it’s also palliative care.

Writing for NBC News, Gretchen Morgenson describes how HCA Healthcare — the nation’s largest hospital chain — outsourced its death panels to IBM Watson, whose algorithmic determinations override MDs’ judgment to send patients to palliative care, withdrawing their care and leaving them to die:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/doctors-say-hca-hospitals-push-patients-hospice-care-rcna81599

Incentives matter. When HCA hospitals send patients to die somewhere else to die, it jukes their stats, reducing the average length of stay for patients, a key metric used by HCA that has the twin benefits of making the hospital seem like a place where people get well quickly, while freeing up beds for more profitable patients.

Goodhart’s Law holds that “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Give an MBA within HCA a metric (“get patients out of bed quicker”) and they will find a way to hit that metric (“send patients off to die somewhere else, even if their doctors think they could recover”):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goodhart%27s_law

Incentives matter! Any corporate measure immediately becomes a target. Tell Warners to decrease costs, and they will turn around and declare the writers’ strike to be a $100m “cost savings,” despite the fact that this “savings” comes from ceasing production on the shows that will bring in all of next year’s revenue:

https://deadline.com/2023/08/warner-bros-discovery-david-zaslav-gunnar-wiedenfels-strikes-1235453950/

Incentivize a company to eat its seed-corn and it will chow down.

Only one of HCA’s doctors was willing to go on record about its death panels: Ghasan Tabel of Riverside Community Hospital (motto: “Above all else, we are committed to the care and improvement of human life”). Tabel sued Riverside after the hospital retaliated against him when he refused to follow the algorithm’s orders to send his patients for palliative care.

Tabel is the only doc on record willing to discuss this, but 26 other doctors talked to Morgenson on background about the practice, asking for anonymity out of fear of retaliation from the nation’s largest hospital chain, a “Wall Street darling” with $5.6b in earnings in 2022.

HCA already has a reputation as a slaughterhouse that puts profits before patients, with “severe understaffing”:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/workers-us-hospital-giant-hca-say-puts-profits-patient-care-rcna64122

and rotting, undermaintained facililties:

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-care/roaches-operating-room-hca-hospital-florida-rcna69563

But while cutting staff and leaving hospitals to crumble are inarguable malpractice, the palliative care scam is harder to pin down. By using “AI” to decide when patients are beyond help, HCA can employ empiricism-washing, declaring the matter to be the factual — and unquestionable — conclusion of a mathematical process, not mere profit-seeking:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/26/dictators-dilemma/ggarbage-in-garbage-out-garbage-back-in

But this empirical facewash evaporates when confronted with whistleblower accounts of hospital administrators who have no medical credentials berating doctors for a “missed hospice opportunity” when a physician opts to keep a patient under their care despite the algorithm’s determination.

This is the true “AI Safety” risk. It’s not that a chatbot will become sentient and take over the world — it’s that the original artificial lifeform, the limited liability company, will use “AI” to accelerate its murderous shell-game until we can’t spot the trick:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/10/in-the-dumps-2/

The risk is real. A 2020 study in the Journal of Healthcare Management concluded that the cash incentives for shipping patients to palliatve care “may induce deceiving changes in mortality reporting in several high-volume hospital diagnoses”:

https://journals.lww.com/jhmonline/Fulltext/2020/04000/The_Association_of_Increasing_Hospice_Use_With.7.aspx

Incentives matter. In a private market, it’s always more profitable to deny care than to provide it, and any metric we bolt onto that system to prevent cheating will immediately become a target. For-profit healthcare is an oxymoron, a prelude to death panels that will kill you for a nickel.

Morgenson is an incisive commentator on for-profit looting. Her recent book These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs — and Wrecks — America (co-written with Joshua Rosner) is a must-read:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/02/plunderers/#farben

I’m kickstarting the audiobook for “The Internet Con: How To Seize the Means of Computation,” a Big Tech disassembly manual to disenshittify the web and bring back the old, good internet. It’s a DRM-free book, which means Audible won’t carry it, so this crowdfunder is essential. Back now to get the audio, Verso hardcover and ebook:

http://seizethemeansofcomputation.org

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/05/any-metric-becomes-a-target/#hca

[Image ID: An industrial meat-grinder. A sick man, propped up with pillows, is being carried up its conveyor towards its hopper. Ground meat comes out of the other end. It bears the logo of HCA healthcare. A pool of blood spreads out below it.]

Image: Seydelmann (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GW300_1.jpg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#hca healthcare#Gretchen Morgenson incentives matter#death panels#medicare for all#ibm watson#the algorithm#algorithmic harms#palliative care#hospice#hospice care#business#incentives matter#any metric becomes a target#goodhart's law

542 notes

·

View notes

Text

13/7/23 // 12.23

Study day for me today aka endless hot drinks and snacks

#mine#studyblr#studyspo#notes#studying#pharmblr#pharmacy#medblr#Maria does diploma#palliative care#study space#myhoneststudyblr#study notes

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help Fundraise for a Dying Papa

I don't normally make this sort of post, and never on my own behalf, but it's time I have to ask the help of anyone who's able. My father, Mark St. Amant, was recently diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer. He's opted for palliative care over any kind of extension of life thru chemo.

I'm still sort of in shock about the whole thing, there's been plenty of laughing and crying and all sorts of strangeness, but right now money is the issue. Papa wants to spend his last months in Oregon, near me, and moving costs as well as the palliative care don't come cheap. He's also looking into a Death with Dignity (physician-assisted death) option, which isn't covered by insurance and so has its own costs. We're hoping to have him up here in the next two weeks, which I know isn't long, so it's high time to ask for help.

Please, only give if you're able; I know the situation isn't great for a lot of folks out there and don't want to ask hardship of anyone else. If you can't give, a reblog would be appreciated to spread this around. I don't know what kind of a footprint I have here but I'm hoping this will at least help.

Thank you so much in advance, even for reading this far. We're gonna make it through this.

#gfm#medical costs#palliative care#fundraiser#cancer#healthcare#mutual aid#assisted dying#oregon#health insurance#terminal illness

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“[Euthanasia] is never a source of hope or genuine concern for the sick and dying. Instead, it is a failure of love, a reflection of a ‘throwaway culture’ in which ‘persons are no longer seen as a paramount value to be cared for and respected,'” he continued. “Indeed, euthanasia is often presented falsely as a form of compassion. Yet ‘compassion,’ a word that means ‘suffering with,’ does not involve the intentional ending of a life, but rather the willingness to share the burdens of those facing the end stages of our earthly pilgrimage. Palliative care, then, is a genuine form of compassion, for it responds to suffering, whether physical, emotional, psychological or spiritual, by affirming the fundamental and inviolable dignity of every person, especially the dying, and helping them to accept the inevitable moment of passage from this life to eternal life.”

#catholicism#pope francis#live action#live action news#euthanasia#palliative care#pro life#pro every life

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friendly reminder that prenatal children with a terminal diagnosis have a right to hospice/palliative care, and parents have a right to obtain emotional and psychological support through that time.

112 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Commission of a scene from the fic Perfectly Imperfect by JustSomeStranger !

#Overwatch#junkrat#roadhog#roadrat#CW Death#Major Character Death#End of Life#End of Life Care#Palliative Care#CW Cancer#End Stage CW#my art

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

#tiktok#palliative care#end of life care#tw death#uk#tw death mention#death mention tw#death ment tw#sky news#uk news#tw medical#medical mention

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Paradox of Control — Surrender, Acceptance, and True Agency - Post 5 of 5

The pursuit of control is a fundamental aspect of the human condition—an enduring impulse that finds its expression in nearly every facet of existence. Photo by JESHOOTS.com on Pexels.com From mastering physical environments to orchestrating societal structures, humanity’s narrative has been a perpetual endeavour to impose order upon chaos. This relentless striving is enshrined in political…

View On WordPress

#acceptance#ACT therapy#agency#Arendt#bioethics#Buddhism#collective agency#Confucianism#control#Degrowth#ecological ethics#Ecology#Foucault#Gandhi#indigenous traditions#learned helplessness#meditation#mindfulness#Neuroplasticity#non-attachment#palliative care#phenomenology#Political Theory#Raffaello Palandri#Stoicism#surrender#Sustainability#Taoism#transpersonal psychology#Wu Wei

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just seen a woman on TV protesting against euthanasia for disabled people, her argument being "well I'm disabled and I don't want to be euthanized!!"

I just wanted to scream. Disabled or not, this isn't about you. This is about terminally ill people desperately wanting dignity in death! People like you are inhibiting perhaps the most death positive movement England has ever passed for selfish, unfounded, unsympathetic reasons.

People are more or less acquainted with the "my body my choice" argument following the recent rows over abortion, so why can't that be applied to dying people desperate to retain the dignity stripped of them by their sickness.

#euthanasia#liz carr#tw death#tw euthanasia#disability#disabled#disabilties#terminal illness#palliative care

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

i generally don't post about my personal life on here, but i went to high school with ariel and watching her cystic fibrosis progress so rapidly in recent years has been devastating. she's entering hospice today and is raising money to pay for her care, as her insurance won't cover all of her medical bills and as we all know healthcare in the united states is unbelievably expensive.

please donate if you're able, and please reblog this so it can reach other people.

#cystic fibrosis#cf#medical bills#fundraiser#i dont know what fucking tags to use im just trying to get more traction#mutual aid#gofundme#donate#please donate#signal boost#boost#fundraising#fundrasier#ohio#lgbt#united states#healthcare#hospice#palliative care#hospital bills#hospital#medicine#cystic fibrosis awareness#cf awareness#money

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

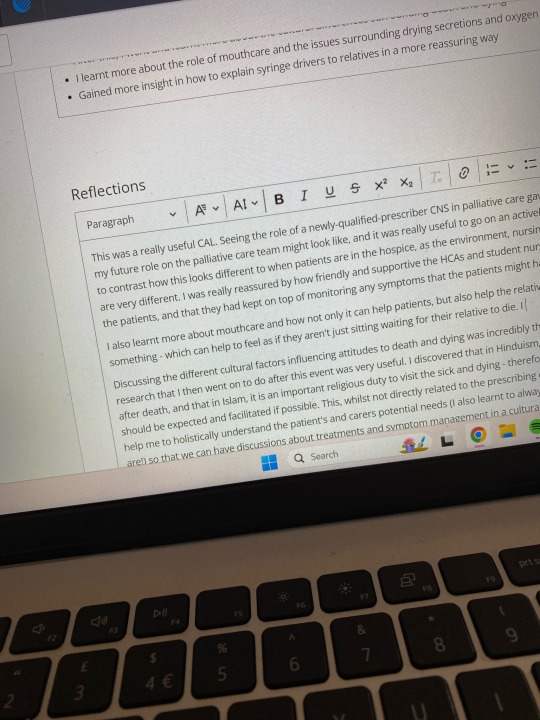

14/4/24 // 15.58

Hello. I’m drowning in reflections to write up but exciting news!!!! I got offered a hospice job last week! I’m now a lead pharmacist for palliative care. What an absolutely exciting amazing moment in my life. Not at all where I thought my career would go but I absolutely cannot wait!

#mine#studyblr#studyspo#notes#studying#pharmblr#pharmacy#medblr#good vibes#Maria does IP#Maria does diploma#palliative care

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a personal note - I have been struggling with grief for the past four months. My cat, Tiggette, was diagnosed with late stage abdominal cancer. I was told she only had a few weeks. I've had her for 18 years. Almost half my life. I sat in that vet's office sobbing. Not again!

Given how quickly I lost my other cat, Jayne, I was ready to save her from any pain. She seemed to take a quick decline and then the morning I was set to say goodbye she did a 180. I found out that the gabapentin I was giving her was making her seem sicker than she was. (In cats, gabapentin gets stored in their kidneys for an undetermined time until they release the medicine.) So I cancelled my appointment. I cancelled my PTO.

Then she had a bad day around the holidays that she recovered from. And then a bad few days in January. I kept in contact with my vet and I started to make another appointment and for a third time Tiggette said "Just Kidding! ✌🏼" And now for the past almost two weeks she's been in a steady decline.

On Monday, I looked at the facts. I listened to my gut. I made the appointment. I took PTO. I gave myself almost two weeks certain that she would just get worse and I would possibly lose her too soon.

This fucking bitch.

I just wrote a very lengthy text to my vet explaining everything and asking for advice. She's become litter box averse. She's become food averse. And both of these things say "it's time". But I think I fucked up with the food part. When I thought she was going too fast I was like "you can have ALLLLL the Greenies you want!" Because what kind of monster would deny a dying cat joy?? But... If you give cats a lot of treats they become food averse. They only want treats. But I can't not feed her. She's sick! She's definitely not eating as much as she should. When I limit her treats and she is hungry enough to eat her actual food she doesn't eat much. And with the litter box I have pee pads everywhere. And she stopped "covering" where she went. Until tonight. That was my first clue that she was coming out of her spell.

What the fuck do I do?? I have spent every day crying because I don't want to say goodbye. Who does?? But it feels like torture. I feel like I'm being gaslit and I'm bringing everyone for the ride! I spent $300 on professional house cleaners so she could be in a "calm environment".

I feel guilty for taking everyone on this ride with me. I fear feeling guilty if it's too soon. And I know the prevailing sentiment is "do it before it gets worse and save her the pain". But I don't even know if she's actually in pain!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been dying for so long now that I’ve become used to it, but signing the DNR (do not resuscitate order) and starting palliative care has been eye opening.

Being online is so difficult now. EVERYONE talks about the future. Things they look forward to, things they want to change, saying that things will change. Will get better.

I even find myself thinking about books, movies, and tv shows, new seasons of the shows that’ll come out and that I don’t even know if I’ll be alive to see any of them.

It’s just really depressing and really hard knowing that things will not get better for me. It’s only going to get worse from here. But the world just spins madly on.

#personal#terminally ill#chronic illness#chronic illness tag#palliative care#how do you die in your twenties without going actually insane or making everyone around me miserable?#oh also everyone assumes you only die young from an accident or cancer#I can’t find any support groups bc it’s all cancer and my illnesses make my death a little different

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an interview with Vatican News ahead of the event, Bishop Simard noted the confusion around palliative care, where euthanasia is permitted under the euphemism “medical assistance in dying,” or MAID. The practice involves doctors or nurse practitioners to either administer drugs to end a patient’s life, or provide drugs that are administered by the patients themselves. Palliative care, by contrast, “is accompanying people’s lives,” said Bishop Simard, attempting to respond to all the person’s need. “So yes, we need to answer the problem of suffering and pain,” the Bishop says, “but at the same time, there are many other needs” that must be addressed. ... “We are telling them: ‘You are still a person loved by God. You have your place in society. And we are here to tell you that we love you,’” the Bishop said. It also means assuring them that they are not alone and expressing to them the compassion and tenderness of God that never leaves them. Bishop Simard likewise highlighted the importance of listening to the person, “to her fears, to her anxiety, and also to what she is unable to say... accompanying helps them to express” their hopes and fears as they approach the end of their lives. Palliative care, he continued, is also concerned for family members and other caregivers, for whom accompaniment can be a challenge. “We have to be there to listen to them and maybe offer them some respite,” he said, adding that listening to all those involved in palliative care is “essential.” The Canadian Bishop also emphasized the necessity of accompaniment in the dying person’s spiritual life. Prayer and the reception of the Sacraments are important means to help the person prepare themselves “to go and join the Lord in glory,” reflecting the “very important role” of palliative care for the spiritual life.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharon Carstairs

Sharon Carstairs was born in 1942 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1984, Carstairs was appointed leader of the Liberal Party in Manitoba, making her the first woman in the province's history to lead a major political party. In 1994, Carstairs was appointed to the Senate of Canada. From 2001 to 2003, she was Leader of the Government in the Senate and Minister with Special Responsibility for Palliative Care. Carstairs used this role to direct government money to programs and research in palliative care. She secured the funding to create the Canadian Virtual Hospice, an educational website with resources on loss, advanced illness, and palliative care. The site reaches millions in Canada and around the world. In 2016, Carstairs was appointed to the Order of Canada for her work championing palliative care.

#canada#canadian#women leaders#palliative care#politics#women in politics#manitoba#canadian politics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is what pro-life, palliative care looks like for the child with a terminal diagnosis.

14 notes

·

View notes