#On Comics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

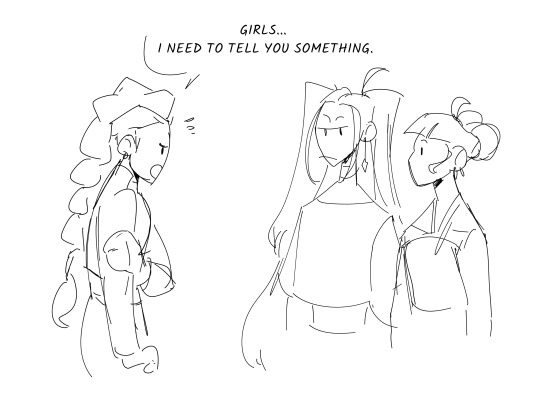

Not to put you on blast, but speaking as a comic artist, I can tell you that all that random emphasis isn’t actually as random as you might think!

I’m sure every comic letterer has their own criteria for when and how (and whether) to employ this technique, but the way I see it, there’s a couple of overlapping reasons why it’s done:

It makes the text a bit more legible. The bolded words act as visual landmarks that help guide the reader through the text. Comic text is pretty weird, typographically speaking: it has a very small line-height and it’s center-aligned, not to mention it’s usually printed in allcaps. This is all done in the interest of conserving space for the illustrations, but it makes for text that can be kind of fatiguing to read. The extra visual emphasis on key words and phrases can make it easier to quickly parse the text, especially in larger speech bubbles.

It also serves the usual purpose of indicating the natural word emphasis that people employ when speaking English. Usually you’d just use italics for that, but italics are hard to distinguish in handwriting, so letterers will use either bold or bold-italics for the job. Beyond that, the difference is mainly down to quantity: comic letterers traditionally go a bit ham with this technique, whereas it’d be gauche to do the same thing in prose. But that’s a matter of convention.

Emphasis on the word traditionally in that last point, by the way. In truth, this convention has been on its way out for a while. Lots of comics these days even have lowercase letters! It’s easier to pull off with the switch to digital lettering. But I still find the practice charming as heck.

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kalat Club and 30 Summers Ago: Love Letters to a Sapphic Past

Time is a fascinating element in stories. It is a fundamental part of storytelling, essential to a narrative’s setting. Sometimes it’s treated as an afterthought, and its implications to a story are not interrogated. But some of the best stories I’ve enjoyed are ones where time makes itself inextricable to the narrative, looming, sometimes haunting, a foundation for the events that will unfold.

When it comes to queer-centric stories, knowing when the story is set adds a layer of understanding as to why characters act the way they do. The dynamics between sapphic characters will be different between a story set during the late 70s versus a tale set during the American occupation. The context is different. The stakes are different.

There are a lot of sapphic stories set in times far past, but right now, I want to focus on two comics that situate themselves in recent history, set in the near past of the 2010s and the 2000s.

First released as part of the Silakbo GL Anthology, Kalat Club and 30 Summers Ago are two stories that situate themselves in two different periods, and this placement in time is integral to the story they are trying to tell. They are both love letters to past selves and hope for a better, queer future. And it’s because of this I want to take the time to talk about how time situated itself in these two entries and what that means for sapphic comics and stories in the future.

If you'd like to read more, the rest is on my medium page!

Wrote a little something on two comics that I liked from Silakbo, and how these two entries reflect what the world was like to a queer teen in that time :D.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw it was make a terrible comic day today (June 24 2025) so meet my cats

#makeaterriblecomicday2025#my art#comic#comics#cat comic#it is indeed a terrible comic#but I recently adopted these two after fostering 4 cats and missing having cats of my own#I love them both very much#They're still adjusting to the house and finding who their person is#especially Lucida Sans#But that's ok i know she had a tough start#She and Tammy came to the shelter pregnant#And from Lucida's body it seems like she had been pregnant many times#but now she doesn't have to be a mommy cat anymore#she just learned how to play and have fun!#it took her 2 weeks to learn how to play by watching Tammy play#Meanwhile Tammy has a kitten mindset#she still suckles on Lucida#the only time Tammy purrs is when she's suckling#that is#until she started recently purring when I pet her and carry her around#She is so sweet and funny#but she also jumps on my railing that overlooks the basement stairs down and its a steep fall#and I don't know how to stop her and I live in fear one day she'll slip and fall down

69K notes

·

View notes

Text

Local goat discovers joy of painting

105K notes

·

View notes

Text

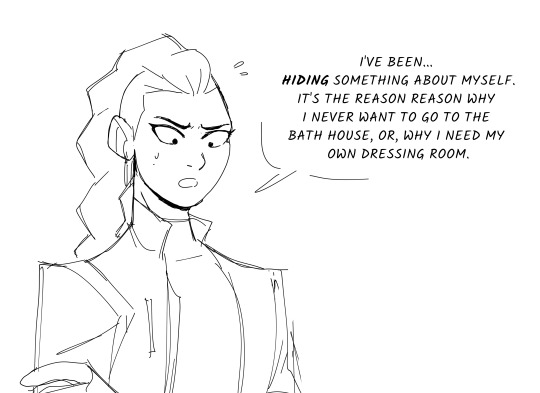

"... You're what??"

#kpop demon hunters#huntrix#rumi#zoey#mira#comic#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#character art#my art

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

Today I met happiness

#art#digital art#artist#digital artist#artwork#comic#lgbtq comic#lgbt comic#trans#transgender#trans artist#trans art#trans pride#lgbtq+#lgbtq#lgbtq pride#bamjammy art

94K notes

·

View notes

Text

do y'all remember when they found all that tf art in Osamu Tezuka's drawer post-mortem because I think about it often

anyway keep chasing your bliss and draw weird shit, god knows we need that right now

87K notes

·

View notes

Text

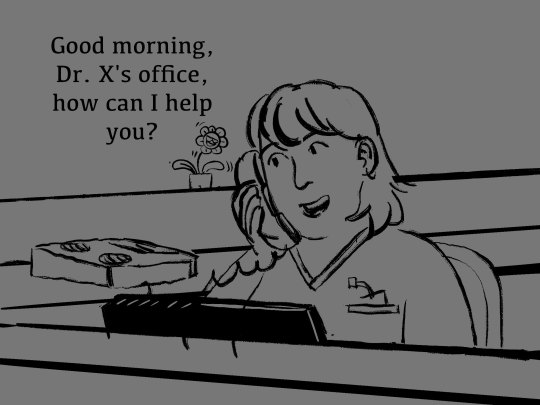

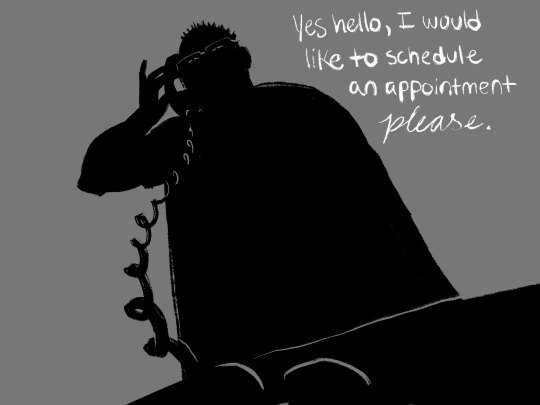

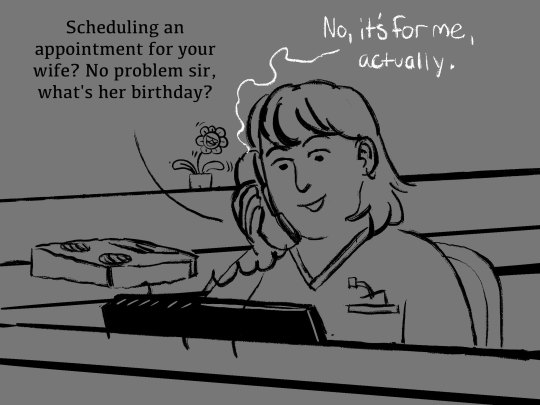

*doom music starts to play* I actually kindof like scheduling these kinds of appointments now...

but seriously Fellas, don't forget to schedule a pap smear every couple of years just in case. If you still have a cervix you can still get cervical cancer. ilu

this has been a psa

#my art#my comics#og post#psa#trans healthcare#gender affirming receptionist lady#transgender#lgbt#queer comics

181K notes

·

View notes

Text

184K notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe this therapy shit is working

100K notes

·

View notes

Text

widehead

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

I can be shaped by more than the things that hurt me

74K notes

·

View notes