#Native Plants of the Eastern United States

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Plant Profile: American Witch Hazel - Hamamelis virginiana

Today's plant is better known for its use as a facial toner but this year I've witnessed a mass-bloom (the yellow dots in the image above) so I want to re-introduce you my ultimate late fall favorite!

Witch-Hazel refers to members of the Hamamelis family, containing about five species, 3 of which are found in the eastern US and the other two in Asia. Our species of focus is the American Witch Hazel, a wide growing, often dominate understory shrub/tree common throughout forests of the American East. The plant has a lovely arching growth habit (Image 2 above), alongside trails in older-growth tall mountain forests, one always can spot witch hazel by a tunnel effect along the trails framed by its branches.

For a quick technical analysis, Witch Hazel has oval alternate leaves that are asymmetrical and have rounded lobes along the sides (image 3 of pressed leaf). The bark is a grey or reddish brown with small lenticels (image 4 of 'trunk') and typically grows in clusters sprouting from deep roots. Typically the plant reaches about 20' in height and 20' in width, as I usually only see specimens this large in very old portions of woodland my assumption is that it takes many decades to achieve this stature.

The flowers themselves are divided into 4 portions with yellow ribbon-like petals present from October-December (image 5, 6, 9). The flowers are extremely fragrant in wet weather and mornings, the scent usually fades in drier conditions. Flowers lose their ribbons and recede into this hardened portion connected to the stem called a calyx (it looks like a rounded pod which can have about 4 seeds in it). The seeds actually shoot out of this pod as a dispersal method around the next fall.

I brought up flowering because like many species in the northeast, there is never a consistent year for these things, while I see witch-hazel flowers every year I don't encounter blooms prolifically unless it's exposed to a lot of sun light. From my experience, a mass-bloom (in which every tree has noticeable blooms like image 1) occurs every 5 years about, I've noticed this in my forest since childhood but others may have more frequent encounters than me.

American Witch Hazel has a large range and is found throughout the Eastern US. The Northern limit of its range is Nova Scotia to Wisconsin staying mostly east of the Mississippi River south until its South Western Limit in East Texas and Northern Florida to the East. Allegedly disjunct populations also exist in Lost Maples Texas and the Eastern Sierra Madres of Mexico but those are fairly isolated from the main range.

There are two other Hamamelis species located within the same range. H. vernalis: Ozark Witch-hazel, which is a common horticultural specimen due to its reddish yellow blooms coming out just before spring and is naturally restricted to the Ozarks. H. ovalis: big leaf witch-hazel is a new species discovered in 2004, found only in one watershed in Mississippi and Alabama; this species has much larger leaves and red mid-winter blooms. Most people are unlikely to encounter these in the wild at all.

Hamamelis virginiana can grow in both acidic and alkaline conditions, though I tend to find the densest populations on protected north facing slopes in mature forests near where water travels. I've also found it on pure rock on mountain top balds in New York before (image 7 above). This is because in the North, American Witch Hazel isn't as limited in habitat as in the Southern portion of it's range where it's generally restricted to only cove forests and bottom lands. generally there is an association with the Witch Hazel and decent moisture.

Speaking of moisture, Early English settlers (shown by Native Americans) used witch hazel branches as dowsing rod to find underground water sources. Sticking branches in the ground, and watching which portion bent upon encountering streams. It's likely the name 'Witch' in Witch Hazel derives either from Middle English 'Wiche' for 'lively' or Anglo-Saxon 'Wych' for 'bend' describing this use. [Info from US Forest Service].

Witch Hazel is also a protector of the forest following disturbance. In a Canadian Journal of Forest Research Study by Taylor Benton, analysis found that where large scale canopy loss was present H. virginiana was found to increase it's basal area growth (think spread) by over 300%. This indicates that in the presence increased light and nitrogen, the dominate understory species are able to protect seedlings by increasing canopy shade!

In my own forest I've noticed this where Ash has died back, the Witch Hazel flowers more prolifically and frequently as well as becoming denser (Image 8 Witch-hazel in flower above a stream)

Now what are the ecological relationships associated with American Witch Hazel? This species specifically provides one of the last insect oriented pollen sources prior to winter (other witch-hazel species often bloom in early spring), so species like the owlet moth which are active in winter, and late season bees get a food source from it. The leaves are occasionally predated by a gall wasp which forms many odd tents on the leaf in favorable conditions.

Propagating Witch-hazel for those crazy like me should be aware it is not an easy plant to start. The seeds require a period of moist cold stratification, then warm, then another cold (think 90 days of fridge, 90 days in warmth, 90 days in fridge) then it'll begin to germinate. If you have a full specimen you can attempt layering (which is covering a low branch in soil allowing it to root). You can take softwood cuttings in spring but they have to be kept frost free the next winter.

Finally Landscaping advice! Witch-Hazel is best utilized in partially shaded non-south facing or moist areas in partial sun. While it loves total shade in its natural environment it really preforms much better in a garden with some sunlight. American Witch-Hazel also is a better performer in the scent category rather than a showy floral display, most horticultural specimens are derived from hybrids between Chinese, Japanese, or Ozark Witch-hazel (image 10 of possible H. vernalis cultivar above) as their coloring is much more interesting compared to our local powerhouse. However it must be said that American Witch-hazel is resilient and has some flower color variation (oranges and pinks) which are absent in other species.

So this has been my plant profile on American Witch-Hazel, please go into the woods and smell the haunting yellow blooms while the mass-bloom is still occurring. Happy Hunting to my Eastern American followers :)!

#American witch hazel#Hamamelis virginiana#plant profiles#Native Plants of the Eastern United States#Understory Species#Fall and winter flowers

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost: Reasons I firmly believe we will beat climate change

Posts are in reverse chronological order (by post date, not article date), mostly taken from my "climate change" tag, which I went through all the way back to the literal beginning of my blog. Will update periodically.

Especially big deal articles/posts are in bold.

Big picture:

Mature trees offer hope in world of rising emissions (x)

Spying from space: How satellites can help identify and rein in a potent climate pollutant (x)

Good news: Tiny urban green spaces can cool cities and save lives (x)

Conservation and economic development go hand in hand, more often than expected (x)

The exponential growth of solar power will change the world (x)

Sun Machines: Solar, an energy that gets cheaper and cheaper, is going to be huge (x)

Wealthy nations finally deliver promised climate aid, as calls for more equitable funding for poor countries grow (x)

For Earth Day 2024, experts are spreading optimism – not doom. Here's why. (x)

Opinion: I’m a Climate Scientist. I’m Not Screaming Into the Void Anymore. (x)

The World’s Forests Are Doing Much Better Than We Think (x)

‘Staggering’ green growth gives hope for 1.5C, says global energy chief (x)

Beyond Catastrophe: A New Climate Reality Is Coming Into View (x)

Young Forests Capture Carbon Quicker than Previously Thought (x)

Yes, climate change can be beaten by 2050. Here's how. (x)

Soil improvements could keep planet within 1.5C heating target, research shows (x)

The global treaty to save the ozone layer has also slowed Arctic ice melt (x)

The doomers are wrong about humanity’s future — and its past (x)

Scientists Find Methane is Actually Offsetting 30% of its Own Heating Effect on Planet (x)

Are debt-for-climate swaps finally taking off? (x)

High seas treaty: historic deal to protect international waters finally reached at UN (x)

How Could Positive ‘Tipping Points’ Accelerate Climate Action? (x)

Specific examples:

Environmental Campaigners Celebrate As Labour Ends Tory Ban On New Onshore Wind Projects (x)

Private firms are driving a revolution in solar power in Africa (x)

How the small Pacific island nation of Vanuatu drastically cut plastic pollution (x)

Rewilding sites have seen 400% increase in jobs since 2008, research finds [Scotland] (x)

The American Climate Corps take flight, with most jobs based in the West (x)

Waste Heat Generated from Electronics to Warm Finnish City in Winter Thanks to Groundbreaking Thermal Energy Project (x)

Climate protection is now a human right — and lawsuits will follow [European Union] (x)

A new EU ecocide law ‘marks the end of impunity for environmental criminals’ (x)

Solar hits a renewable energy milestone not seen since WWII [United States] (x)

These are the climate grannies. They’ll do whatever it takes to protect their grandchildren. [United States and Native American Nations] (x)

Century of Tree Planting Stalls the Warming Effects in the Eastern United States, Says Study (x)

Chart: Wind and solar are closing in on fossil fuels in the EU (x)

UK use of gas and coal for electricity at lowest since 1957, figures show (x)

Countries That Generate 100% Renewable Energy Electricity (x)

Indigenous advocacy leads to largest dam removal project in US history [United States and Native American Nations] (x)

India’s clean energy transition is rapidly underway, benefiting the entire world (x)

China is set to shatter its wind and solar target five years early, new report finds (x)

‘Game changing’: spate of US lawsuits calls big oil to account for climate crisis (x)

Largest-ever data set collection shows how coral reefs can survive climate change (x)

The Biggest Climate Bill of Your Life - But What Does It DO? [United States] (x)

Good Climate News: Headline Roundup April 1st through April 15th, 2023 (x)

How agroforestry can restore degraded lands and provide income in the Amazon (x) [Brazil]

Loss of Climate-Crucial Mangrove Forests Has Slowed to Near-Negligable Amount Worldwide, Report Hails (x)

Agroecology schools help communities restore degraded land in Guatemala (x)

Climate adaptation:

Solar-powered generators pull clean drinking water 'from thin air,' aiding communities in need: 'It transforms lives' (x)

‘Sponge’ Cities Combat Urban Flooding by Letting Nature Do the Work [China] (x)

Indian Engineers Tackle Water Shortages with Star Wars Tech in Kerala (x)

A green roof or rooftop solar? You can combine them in a biosolar roof — boosting both biodiversity and power output (x)

Global death tolls from natural disasters have actually plummeted over the last century (x)

Los Angeles Just Proved How Spongy a City Can Be (x)

This city turns sewage into drinking water in 24 hours. The concept is catching on [Namibia] (x)

Plants teach their offspring how to adapt to climate change, scientists find (x)

Resurrecting Climate-Resilient Rice in India (x)

Edit 1/12/25: Yes, I know a bunch of the links disappeared. I'll try to fix that when I get the chance. In the meantime, read all the other stuff!!

Other Masterposts:

Going carbon negative and how we're going to fix global heating (x)

#climate change#climate crisis#climate action#climate emergency#climate anxiety#climate solutions#fossil fuels#pollution#carbon emissions#solar power#wind power#trees#forests#tree planting#biodiversity#natural disasters#renewables#renewable electricity#united states#china#india#indigenous nations#european union#plant biology#brazil#uk#vanuatu#scotland#england#methane

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I meant to post this earlier in the month, but in case you missed it, the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is going to be listed as a threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act. It's a bit disappointing for those of us pushing for full endangered status because a threatened species doesn't receive as complete a set of protections. But it's better than nothing.

Monarch butterflies have seen a precipitous drop in numbers over the past few decades, to include both the western and eastern North American subpopulations. When I was a child in Missouri in the 1980s they were a common sight in our garden; that's not the case any more. The western subpopulation, found west of the Rocky Mountains, is much smaller than the eastern and so is at even greater risk of extinction.

As with most endangered species, habitat loss is the leading cause of population drop. While an adult monarch butterfly can feed from a variety of flowers, the caterpillars can only eat the leaves of milkweed (Asclepias spp.) No milkweed means no monarchs, and as open fields and meadows are increasingly paved over or turned into housing developments with sterile grass lawns, the monarchs have fewer and fewer places to lay their eggs. Climate change is also having a negative effect on monarchs; many died in last January's freezing temperatures that hit their overwintering sites in Texas and Mexico, and temperature variability also affects monarch reproduction.

While the ESA threatened listing is a move in the right direction, it's not enough. Existing monarch habitat must be protected, and lost habitat restored as much as possible. Even little pockets of native milkweeds for caterpillars, and other native wildflowers for the adults, can create important oases, so planting these species in your yard or on your porch can help monarchs and other native insects. Avoid non-native, tropical milkweed species, as these can host dangerous parasites. And keep pushing U.S. Fish and Wildlife to give monarchs full endangered status, while supporting organizations that advocate for these butterflies, like the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

#monarch butterflies#butterflies#insects#invertebrates#arthropods#nature#wildlife#animals#environment#conservation#scicomm#endangered species#extinction#animal welfare

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Water Willow

Justicia americana

This native perennial loves water and can be found in very moist habitats. Its native range spans from Texas, throughout much of the eastern United States, to southeastern Canada. I found this blooming plant with purple and white bicolored flowers among a small colony growing in the middle of a shallow creek.

June 6, 2023

Shannon County, Missouri, USA

Olivia R. Myers

@oliviarosaline

#botany#plants#native plants#native flowers#flowers#nature#ozarks#the ozarks#naturecore#missouri#fairycore#wetlands#aquatic plants#wildflowers#wild flowers#goblincore#cottagecore#Justicia americana#Justicia#water willow#american water willow#Acanthaceae#Dianthera americana#Dianthera#Missouri nature#plants of the ozarks#plants of tumblr#hiking#exploring nature#plant photography

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sopa de mora salvadoreña (Salvadoran black nightshade soup)

American black nightshade (Solanum americanum)—not to be confused with bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) or deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna)—is a widespread flowering plant in the genus Solanum which grows throughout central America and Mexico, and into the northeastern United States. The genus Solanum, within the nightshade family Solanaceae, also includes tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplants.

The ripe berries of this plant, perhaps unsurprisingly, taste something like a very small tomato—but this dish concerns the plant's leaves. Sopa de mora is an earthy, savory, slightly spicy soup eaten in the countryside of El Salvador. It is made from the leaves of hierba mora, or black nightshade, in addition to squash, potato, chili, and sometimes chicken; a beaten egg or two may also be added and cooked, without stirring, directly in the soup.

A similar soup, made from black nightshade and broken pasta, is eaten in Guatemala under the name "caldo de quilete," "sopa de quilete," or "sopa de macuy." "Macuy" presumably derives from the word "majk'u'y", from Kaqchikel: a language in the Maya family spoken in central Guatemala.

Recipe under the cut!

Patreon | Paypal | Venmo

Note that, despite the fact that black nightshade leaves are eaten all throughout the plant's native range, they contain varying amounts of toxic compounds including Solanine, and should be eaten in moderation. Avoid unripe (green) berries, and do not eat leaves raw. Some people advise pre-boiling the leaves and discarding the boiling water to remove toxins.

Ingredients:

Large bunch of American black nightshade (Solanum americanum), Eastern black nightshade (Solanum ptychanthum), or European black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) leaves, washed and chopped

1/2 white onion, diced

2 cloves garlic, chopped

1 tomato, diced

1 jalapeño, sliced

1 small russet potato, diced

1 chayote fruit (güisquil), diced (optional)

1 small carrot, sliced (optional)

Water or vegetable stock

I used water, and found that the vegetables and leaves gave the soup plenty of flavor; but it's not unusual to use vegetable or chicken stock.

Instructions:

Sauté onion and garlic on medium in a large stockpot until onions are softened and translucent.

Add garlic and sauté until light golden brown.

Add tomato and salt and sauté until softened and nearly dry.

Add remaining ingredients, plus water to cover. Boil until vegetables and leaves are softened, 15-20 minutes. Taste and adjust salt.

Identifying American black nightshade

These are quick notes rather than a complete guide. Don't forage unless you know what you're doing!

Leaves are alternate; ovate or lanceolate; with entire to undulate to blunty dentate margins. Flowers are about 1cm in diameter; white to light purple; with yellow stamens. Berries are green when unripe, and glossy and black when ripe. They grow in clusters. Calyxes are smaller than the berries, and curl away from them. Ripe berries, unripe berries, and flowers often appear on the same branch.

Avoid the green, unripe berries, which are toxic.

Lookalikes

Bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) is poisonous. It has berries that are green when unripe, and bright red when ripe. Black nightshade has berries that are green when unripe, and black when ripe.

Deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) is poisonous. It has a calyx extending far beyond the berry, and the berries grow singly. Black nightshade has a calyx smaller than the berry, and its berries grow in clusters.

Eastern black nightshade (Solanum ptychanthum) is also in the Solanum nigrum complex and is sometimes considered synonymous with American black nightshade. It is edible, and may also be used in this recipe. Leaves are alternate; ovate or lanceolate. Leaf margins have 2-5 blunt teeth at the base, but become smooth and pointed at the tip. The base is rounded or cuneate (wedge-shaped). Petioles are winged with extensions of the leaf blade.

Flowers are about 1cm in diameter; white to light purple; with yellow stamens. Berries are green when unripe, and glossy and black when ripe; and grow in clusters.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything You Need to Know About Veggies and Fruits: Cranberries

Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon)

*Kitchen *Medical *Feminine

Folks Names: Bog fruit, Marshworts

Planet: Mars

Element: Water (juice), Fire (berry)

Deities: Astarte, Marjatta,

Abilities: Healing, Protection, Love, Lust, Positive Energy, Courage, Passion, Action

Characteristics: Native to Eastern North America and northern Asia. Small, slender, evergreen shrub growing to 1 ft with oval, dark green leaves, pink flowers and round/slightly pear-shaped red berries.

History: This jewel-toned gem of the bog is native to North America and a traditional food from Samhain through Yule. Its association with the American Thanksgiving meal is long rooted in tradition, but there is no historical evidence proving it was actually served at that first Thanksgiving celebrated by the Pilgrims. Despite this, cranberry something or other is commonly found on Thanksgiving and Christmas feast tables all across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Cranberry garlands made by stringing hundreds of the hard round red berries with a needle onto a long sturdy string is a traditional Christmas decoration. It is believed that cranberries got their name due to cranes always eating them and the blossoms of the berries look like the head of cranes. It is considered a sacred fruit in some indigenous circles such as Algonquian and Iroquois.

How to Grow:

Easy to Plant: Relatively

Rating: Moderate

Seeds accessible: Sometimes seasonal

How to Plant Cranberries

Video Guide

Where to Buy Seeds

Magical Properties

Can be used as a substitute for wine

Dried cranberries can be used in a charm to honor the wisdom of elders or as an offering to ancestors

It’s bright color signals energy, passion, courage, rejuvenation and rebirth

Can lend abundance, love and healing in kitchen spells

Since they are from the bog, it said to be feared by evil spirits and can offer protection

Placing a bowl of cranberries under one’s bed can restore depleted energy and cure an illness

Drinking the juice with your partner on a dark moon can keep your relationship free of trouble and continue to go strong

Can help link wisdom and guidance of ancestors

Can be utilized in energy cleansing rituals to remove negative energies from the aura

Is said to restore chakra alignment balance and create harmony

Burning bundles of cranberry stems can purify the energy of space and promote spiritual well-being during rituals and meditating

Medical Usage:

A classic remedy for urinary tract infections and can prevent and treat problems such as cystitis and urethritis

Can help to disinfect the urinary tubules and may be taken for problems associated with poor urinary flow such as enlarged prostate and blade infections

Can be used long term to prevent the development of urinary stones

Research in 1994 showed that cranberry juice helped really well with UTIs in women

Sources

#witch community#witchblr#witchcraft#paganblr#nature#witchcraft 101#plants and herbs#green witch#occulltism#cranberries#cranberry juice#cranberry sauce#kitchen witch#thanksgiving#fruits and vegetables#berries#baby witch

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

‼️This is a callout post‼️

I hate these guys I hate them so much like actually who decided to start planting Bradford Pears they have Zero good qualities I HATE THEM SO MUCH

So here’s some reasons why you should get rid of these:

They smell like a fish market on a hot summer day but all the fish are a week old

The flowers aren’t that cool like sorry there’s plenty of other trees with white flowers

They are BRITTLE. SO BRITTLE. One gust of wind and your tree is GONE.

They will breed with anything. Whore tree. They cross-pollinate to a point where they become incredibly invasive. And also when they do that they grow thorns and get super ugly 👍

THEY’RE PEAR TREES THAT DON’T EVEN GROW PEARS

Did I mention they smell like fish

‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️‼️ If you have Bradford Pears that you can cut down you should cut them down

Some US states will give you a free tree to replace them with

Here are some better trees to plant in your area:

*these are US based recommendations because I’m pretty sure the US is the only place with Evil Bradford Pear Problems*

Magnolias! They smell amazing and have great flowers. They’re native to Florida but will survive in most of the southeastern US

Dogwoods! There’s both an eastern and a western variety and both are native to North America! Just make sure you get the right type for where you live (east vs west)

Pawpaws! These trees bear fruit, are great for pollinators, and their native range spans about half of the United States

Redbuds! Similar to Dogwoods, there’s both an eastern and western variety. Also native to North America, they’re one of the first trees to bloom in spring

Serviceberry! YOU CAN EAT THE BERRIES!!! Also native to North America, they can survive in a ton of different climates and are great for pollinators

You can find more native trees here

This has been a Bradford Pear Hate Post

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

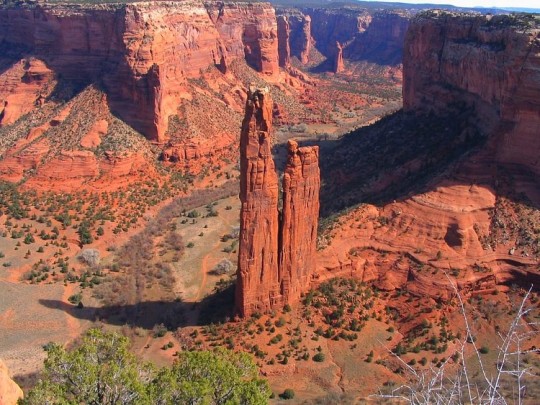

Canyon de Chelly

Canyon de Chelly or Canyon de Chelly National Monument is a protected site that contains the remains of 5,000 years of Native American inhabitation. Canyon de Chelly is located in the northeastern portion of the US state of Arizona within the Navajo Nation and not too far from the border with neighboring New Mexico. It is located 472 km (293 miles) northwest of Phoenix, Arizona. Canyon de Chelly is unique in the United States as it preserves the ruins and rock art of indigenous peoples that lived in the region for centuries - the Ancestral Puebloans and the Navajo. Canyon de Chelly has been recognized as a US National Monument since 1931 CE, and it is one of the most visited National Monuments in the United States today.

Geography & Prehistory

The etymology of Canyon de Chelly's name is unusual in the U.S. Southwest as it initially appears to resemble French rather than the more ubiquitous Spanish. "Chelly" is actually derived from the Navajo word tseg, which means "rock canyon" or "in a canyon." Spanish explorers and government officials began to utilize a "Chelly,” “Chegui,” and even "Chelle" in order to try to replicate the Navajo word in the early 1800s CE, which eventually was standardized to “de Chelly” by the middle of the 19th century CE.

Canyon de Chelly lies very close to Chinle, Arizona, and it is located between the Ancestral Puebloan ruins of Betakin and Kiet Siel in the west and the grand structures of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico in the east. Canyon de Chelly, as a National Monument, covers 83,840 acres (339.3 km2; 131.0 sq miles) of land that is currently owned by the Navajo tribe. Spectacularly situated on the Colorado Plateau near the Four Corner's Region, Canyon de Chelly sits at an elevation of over 1829 m (6,000 ft) and bisects the Defiance Plateau in eastern Arizona. The tributaries of the Chinle Creek, which runs through Canyon de Chelly and originates in the Chuska Mountains, have carved the rock and landscape for thousands of years, creating red cliffs that rise up an additional 305 m (1000 ft). The National Monument extends into the canyons of de Chelly, del Muerto, and Monument.

Canyon de Chelly is one of the longest continuously inhabited places anywhere in North America, and archaeologists believe that human settlement in the canyon dates back some 5,000 years. Ancient prehistoric tribes and peoples utilized the canyon while hunting and migrating seasonally, but they did not construct permanent settlements within the canyon. Nonetheless, these prehistoric peoples did leave etchings on stones and on canyon walls throughout what is now Canyon de Chelly. Around c. 200-100 BCE, peoples following a semi-agricultural and sedentary way of life began to inhabit the canyon. (Archaeologists refer to these peoples as "Basketmakers." They are considered the ancestors to the Ancestral Puebloan Peoples.) While they still hunted and gathered like their prehistoric forebears, they also farmed the land where fertile, growing corn, beans, squash, and other small crops. It is also known that they grew cotton for textile production. Yucca and grama grass have grown in the canyon for several millennia, and indigenous people utilized these plants when making baskets, sandals, and various types of mats. Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia cactaceae) and pinyon are also found throughout Canyon de Chelly, the latter of which provided an important source of food for indigenous peoples in autumn and winter. Fish are found in Canyon de Chelly's tributaries, and large and small game frequent the canyon.

Continue reading...

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

[A] luscious Owari Satsuma citrus tree, whose species was originally imported from Japan, currently experiencing the ravaging effects of an aphid infestation. [...] Where did they come from? [...] And a question that nineteenth- and twentieth-century individuals may have added is, who is to blame? Jeannie N. Shinozuka’s monograph, Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 [...] [examines] such human and nonhuman interconnections [...] [and] meditates on such questions in the historical setting of the American empire, including its transpacific borderland.

Toward the end of the nineteenth and through the twentieth century, the already present anti-Asian racism in the United States was infused with a conservationist attitude of sustainable yield and efficient use of the vast but vanishing natural resources of North America.

---

Unsurprisingly, these racial anxieties appeared just as the American empire expanded well beyond the continent’s borders. The economic threat of chestnut blight or citrus scale played into a native invasive binary that conveniently placed blame for the species’ decline, along with pest and disease introductions, on poor and immigrant groups, while excluding and erasing a longer colonial history of importations of destructive plants and animals by colonial and antebellum planters. These fears were founded not just in the economics of decline, based on a fear of the threat posed to cash crops often grown on increasingly large-scale farms, but also in jealousy surrounding agricultural innovations [...] of certain immigrant farmers [...] in a society plagued with racial anxieties of a so-called yellow peril. Paradoxically, wealthy American citizens interested in beautifying landscapes often held an orientalist fascination with a fetishized and consumable version of a Japanese countryside in the form of tea gardens. [...]

---

The work also discusses the role of newly ordained technocratic officials in giving supposed scientific validity to attitudes toward plant, animal, and human invaders from the Orient.

Plant biologists such as [D.F.] and entomologists [...] were on the forefront of crusades to prevent economically damaging insects and plant diseases from entering the borders of the United States and “degrading” the native stock. Many of these individuals, like [D.F.], were closely associated with some of the leading eugenicist organizations, for example, the American Breeder’s Association, within the United States. Their efforts at plant quarantine culminated in Plant Quarantine Number 37, or PQN 37, a law intended to prevent diseases and infection from foreign animal and plant bodies. This law set a precedent for similar policies regulating humans perceived as alien, including the Immigrant Act of 1924, which limited immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, while completely excluding individuals from Asia. Similarly, officials, [...] [entomologists] included among them, seized and destroyed the property of Japanese immigrants [...].

---

Shinozuka’s work is [...] a contribution to environmental history and Asian studies, [and] it is also a fresh conversation on borderlands and the role that [...] migrant groups, played in such porous places as the US Mexico border and Hawaii, the Pacific gateway to the US empire. Both domains offered opportunities to immigrants and scientists alike [...]. [I]mmigrant labor provided muscle power to corporate-owned American sugar plantations in Hawaii while also experiencing accusations of importing such damaging insects as the termite or Oriental beetle. What Shinozuka makes clear is that while these insects may have originated in southeast Asia, their spread was enabled by the context of American colonialism and empire. The trifold factors of urbanization, industrialization, and monocrop agriculture, all promoted in the interest of American business and marketed as a modernization effort in supposedly backward places like Hawaii, created the perfect circumstances for insects to swarm and disease to spread.

---

All text above by: Jacob Gautreaux. "Review of Shinozuka, Jeannie N., Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950". H-Environment, H-Net Review. August 2024. At: h-net dot org slash reviews/showrev.php?id=60450. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientific Name: Brickellia eupatorioides or Brickellia macranthra Common Name(s): False boneset or Texas false boneset Family: Asteraceae (aster) Life Cycle: Perennial Leaf Retention: Deciduous Habit: Forb USDA L48 Native Status: Native Location: Plano, Texas Season(s): Fall

Brickellia eupatorioides previously comprised a number of sub-taxa that were reclassified as full species in a 2022 paper (PDF). Among these, only B. eupatorioides (sensu stricto) and and the new species B. macranthra (known as B. eupatorioides var. texana before) are found in the county where Plano is located. As outlined in the paper, examining the phyllaries and counting the florets are how to distinguish the two from each other, but I’m not good enough to see those differences after the plant has gone to seed. As the name suggests, Texas false boneset (B. macranthra) is endemic mostly to Texas and Oklahoma, whereas false boneset (B. eupatorioides) can be found throughout the eastern half of the United States.

#Brickellia eupatorioides#Brickellia macranthra#false boneset#Asteraceae#perennial#deciduous#forb#native#Plano#Texas#fall#autumn#fruit#white#plantblr

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I came up with an explanation in my AU for why the Alliance's symbol is a lion despite the lack of lions in the Eastern Kingdoms. ((Which, looking at reddit, may not be too far off from some very hard-to-find canon? Can't find sources)). But I gotta tell a very short story about bald eagles first.

There were only around 400 breeding pairs (compared to historic estimates of 400,000-500,000 total individuals) in the lower 48 states of the US by the 1950s. This population loss was mainly due to shooting and DDT, an incredibly popular pesticide at the time which interfered with the eagle's ability to properly create egg shells. The result was that the shells were too thin to sustain the weight of the nesting adult, and cracked under them.

The bald eagle was not close to extinction at this point, only extirpation (basically, localized extinction) from the US. But still, it would've been a very bad look to kill off your own national symbol. So, lots of laws and years later, there are bald eagles all over the US again. About 300,000, as of 2021.

...You probably see where I'm going with this.

There is one rare lion spawn in the Twilight Highlands, so let's go with that. Historically, the Twilight Highlands and perhaps other regions did have lions. But hunting, collection for menageries, and settlement of their habitats eventually took them out. We're dealing with a rudimentary, medieval understanding of how nature works so, only slightly worse than that of the US* -- if anyone saw any issue with it, it wasn't enough or was too late.

They kept the symbol, of course. When anyone asks, there's a prefabricated story with themes of immortality that's been integrated into the public conscious for years. To spin it around, make it something worthy of pride, or at least that's the intent.

And that's just a beautiful, tragic microcosm of how I write the Alliance. Imperialist to its own detriment, catching others in the crossfire without a care. Ever since the colonization of Kalimdor, they've certainly been hunting and trapping lions there to ship back to the EK, which just rubs it in even more.

*I'm being disingenuous. No one can compare to Aotearoa's godlike mastery of conservation (see: they carefully removed the soil with the native plants in it, marked where each square unit of soil went, kept the soil and plants in a greenhouse, and then put every single square unit of soil with every single plant in the exact same spot it came from, so the filming of the Edoras scenes in Lord of the Rings could be carried out without harm to the environment) BUT, RELATIVELY SPEAKING, the US is kind of, somewhat, in certain ways, actually not the absolute worst at conservation. Despite everything.

Anyway

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plant Profile: Red Maple - Acer rubrum

If you live in America you've probably seen a red maple before, this versatile little beast is one of the most ecologically widespread and common tree species in the east.

Let's start with the name: Why is it called Red Maple? The name refers to the beautiful ruby red spring buds/flowers (Image 1: Red Maple swamp West Milford, NJ) in addition to the vibrant fall colors. Suburbanites often confuse 'Japanese' maples as "red maples" due to the leaf hue but unlike that cultivated variety, Acer rubrum has green leaves and will preform very differently, angry clients sometimes 'buy the wrong tree' then make it YOUR problem.

Red maples are very variable within their geographic range, in some forests they can occupy a dominant understory position, some they are dry mountain dwellers, while in others they are niche successional wetland species but in most cases they exist as a 'short' lived tree usually dying before 100 years of age (Image 2: 150 year old specimen, Chester County, PA). These phenological differences can be genetic quirks of an isolated population or just occupying an available place.

Quick description on how to identify: Red maples are a fast growing deciduous tree species usually free of branches for about half it's height (reaching around a hundred feet). The bark itself is usually a smooth darker grey when young becoming lighter, randomly furrowed, ridged and scaly at maturity, in wetland environments it's not uncommon to see a lime green lichen present on its bark (Image 6). Twigs are usually purplish with redder new growth (Image 4). Buds and flowers are usually fully red (Image 3) and samaras (cute helicopter seeds) have red and green tints and are quite small compared to other American maples. These trees are usually unisexual (flowers are male or female, some pollinated female flowers image 3) though some have both sexes on the same tree and have been known to change genders. The leaf of a red maple (image 5) is pretty variable in proportions but has 3 very distinct lobes (sometimes 5 lobes) and very toothy, opposite placement and will create the most vibrant red color in fall fading slowly to yellow sometimes.

Within its native range red maple has a few 'subspecies' (Swamp red maple var. drummondii whose leaf has hairy undersides and Carolina red maple var trilobum which has a smaller 3 lobed leaf) but not many look alikes of other species. Mountain maple (Acer spicatum) has similar leaves but is a shrub present in the Appalachias and anywhere north of New York. Amur maple is also similar but this is usually restricted to gardens and has a proportionally long leaf.

The native range of red maple encompasses the entire Eastern United States with a southwestern limits in East Texas and a northwestern limit in Minnesota extending eastward with a northern limit in Newfoundland. I've personally seen this tree at both limits of its range (the Everglades and Quebec) and the further south one goes the more restricted to swamps and streams, conversely the further north the less restricted to wetlands it is (Image above: Red Maple on right in Catskills Mountains).

Habitat: Red maple is relatively dominant in New England-Mid Atlantic Wetlands, every tree you see with green lichen is a red maple in the image above (Great Swamp,NJ). The key for red maple seedling germination is soil moisture, which is why the further north one goes the more common it is to find. Naturally Red Maple is not meant to be as dominate as it is, I often state colonialism influenced our modern forest cover in distinct ways. Fire suppression, Low lumber value, and Clear Cut Disturbance has allowed the tree to thrive. Early successional (fast growth/high seeding) and Late successional habits (shade tolerance) makes Red Maple a perfect candidate for 'domination'. This may seem like a looming biodiversity threat when in reality the tree regenerates forest loss extremely well, it's short lifespan and weak wood/shallow root system often allows hardier trees (in non-wetland conditions) to readily take over after several decades. Each image (above and below) I'm showing with near total Red Maple coverage was once farmland less than a century prior giving way to variable forest. Additionally Red maples are important food sources for early pollinators and it's seeds are probably one of the top early summer food sources for squirrels.

Future trends: It is unknown what the future holds for Red Maples, With climate change increasing heavy precipitation events and late spring droughts may impact seedling success, though the tree is hardy in floods and dry periods. The Image above actually just experienced a large wildfire (the image is 6 month before burn) which will likely lead to a replacement with more fire tolerant species. Red Maples have thin bark and die easily when facing predation (Beaver herbivory visible mid-left above) and disturbances. On a positive note, according to a 2022 Boston University study warming trends are increasing the nutritional content (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, etc. concentrations) of its foliage which may be good for forest soil health.

Direct Uses: Red maple is considered a 'soft' maple and is often not used for much aside from veneer. Red maples have concentrated forms of tannin and the bark can potentially be used to make dyes though I have not tried this. Of direct human consumption occasionally people will use this species to derive syrup though unlike sugar maples they have a relatively short harvest period. The leaves are also toxic fodder for equine species (and humans), so don't use this in silvopasture!

Growing Red Maple: Thousands of red maple seedlings usually take over my beds and die within the year, occasionally I'll take a sapling for my personal nursery. I've found that the tree performs extremely well in partial shade and has the potential to grow 2' a year once established. Once mature, not much will survive around the trunk due to it's shallow roots.

Condition and Landscaping: Red Maple is a catch-22 in landscaping: it grows fast, has great color, it can thrive in bad conditions like flooding, droughts, sidewalks, pollution, disease and major damage.... unfortunately they tend to carry these marks and branches can break easily. Many cities use red maple cultivars and hybrids guaranteed to have decent form, it's shallow roots prevent weed (and grass) growth around the trunk. European and west coast cities utilize a hybrid between silver and red maple (Acer x freemanii) as a common hardy street tree. There are two cultivars I will recommend: 'Brandywine' which has dense foliage and 'October Glory' which has deep red fall colors and seeds

Restoration performance: Red Maple makes an excellent forest edge species allowing its vibrant fall color to be fully enjoyed and producing dense foliage to protect the inner woods from drying sunlight (sapling in field above from the Poconos). They're best utilized in wetland restoration projects as they are quite prolific and survive long periods of standing water.

So this was my quick piece on maybe our most common tree, if you're in New England/the Mid-Atlantic in mid winter to spring look up for the characteristic red buds, they're waiting for the right day length to bloom!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miscellaneous Other Birds

...I'm counting sixteen. No, that one doesn't count, there's still only sixteen.

Following Silverhart's lead, I've left off the names on the initial image so you can guess which is which—some I feel are rather obvious and others rather not. Under the cut I'll put the version with every bird labelled.

Some birds have inspiration from existing birds. A few have very direct inspiration, in that I had a bird field guide with me while drawing and, in the case the bestiary entry didn't spark anything solid, would open it to a random page and use whatever it was as inspiration or reference. I don't remember most of these.

Now, let's buckle in for:

Rapid-Fire Birdbuilding

The Tluftasong

The Tluftasong is a nocturnal bird native to Eastern Europe. It bears strong resemblance to an owl, though it is unrelated. It is roughly seven inches from bill to tailtip, and has sooty grey feathers.

A Tluftasong eats insects and nests in hollows and in the eaves of abandoned buildings. Its pupils are extremely dilated, and are unable to significantly change size. Because of this, Tluftasongs cannot safely open their eyes during daylight and are severely impacted by light pollution.

The Lokfotreag

The Lokfotreag is a bird found only in Scotland. Its body is covered in shaggy brown feathers, save for its head, which is bald, save for a bright red crest of feathers. It is incapable of long-distance flight, and primarily eats corpses.

(My intention with this one was to take "turkey vulture" a bit too literally, but it doesn't look very much like an actual turkey.)

The Hurrashbeg

The Hurrashbeg is a kind of corvid native to Ireland. Its feathers are mainly black, though the tips of its wings and tail and the top of its head are white. It is capable of mimicking sounds, though not as well as a parrot or raven, and is noted for doing so incredibly often.

The Konchilkuk

The Konchilkuk is a kind of woodpecker found in Southeast Asia. It is very easily identified as its body is covered in black-and-orange stripes.

The Wobrahfmet

The Wobrahfmet is a black bird found in all of Europe except for southern Europe. Its head is a slightly lighter shade than the rest of its body. It is not picky in its choice of food, and will dine on plants, insects, and corpses alike, and it makes a loud croaking call that can be heard from an impressive distance.

The Hrongnewit

The Hrongnewit is a small bird of prey—a foot in length at most—found throughout all of Europe except for northern Europe. Its feathers are a sandy brown, with a darker body than head and paler feathers on the undersides of its wings and the tip of its tail. It likes to prey on the chicks of domestic birds, if they are left unattended.

The Klomurgrae

The Klomurgrae is a shorebird native to the Midwestern and Northeastern United States. Its feathers are black with white stripes, and its head is bald. Much of its diet consists of washed-up corpses, though it will also dig in the sand for living invertebrates.

The Zagsmenrok

The Zagsmenrok is a tiny bird, four inches in length. It eats mainly seeds. There are two species of Zagsmenrok—one is found throughout almost all of Europe, and is black with a white beak, and the other is found only in Greece, and is white with a black beak.

(This one was based on a chimney swift! Got lucky with the bird book there—not sure what I'd have done if I'd landed on a duck or something.)

The Hreakgleav

The Hreakgleav is a bird native to Russia. It is covered in shaggy grey feathers, and makes a low croaking call. They are frequently seen nesting in manmade structures. They are omnivorous and will eat anything they can find, from seeds to corpses to small living animals to human garbage.

The Wahrembeag

The Wahrembeag is a songbird found throughout the United States and Canada. It is blue-grey in color, with white feathers along its wings, and it eats mainly insects. It is known for singing particularly loudly just before dawn year-round, and remaining silent the rest of the day when not in its spring mating season.

The Sarbrufeat

The Sarbrufeat is a bird of prey found mainly in Canada and the northern United States. Males of the species have white feathers with grey bands on their legs, while females have mottled grey feathers with white stripes on their chest and legs.

The Keltrumram

The Keltrumram is a waterbird found in the southern United States. It is known locally as the "fool's eagle" because the white plumage on its head causes some to mistake it for a bald eagle. It eats fish.

(I think I remember what this bird is, from the "eagle" week... so I designed something that might plausibly be mistaken for either bird. Assuming I remember right.)

The Grozfarwat

The Grozfarwat is a bird with blue-grey feathers and a broad wingspan. Its head is a brighter shade of blue, and it eats seeds, small fish, and invertebrates. Grozfarwats are known for migrating across the Atlantic Ocean, from Europe to South America.

The Mortelgeng

The Mortelgeng is a bird native to the Midwestern United States and parts of Canada. It is brown in color, with a grey underbelly and bright red spots on its face—for males, they encircle their eyes, and for females they are found only in the outside corners of their eyes. They eat insects and grain, and make a whistling call.

(This is probably my favourite of the birds. The Hurrashbeg and Grozfarwat are both vying for second.)

The Burngraega

The Burngraega is a bird found through Europe, particularly northern Europe. It has pure white feathers and a long neck, and lives near water. Burngraegas mainly eat fish and invertebrates.

The Klethghrom

The Klethghrom is a bird found mainly in Brazil. Its feathers are mainly green, with a dark blue chest, and the undersides of its wings are grey with rose-colored streaks. Its tail is long and dark, with dark blue-and-pink eyespots. It makes a cooing noise, and eats all manner of plant parts.

#maniculum miscellaneousbirds#tluftasong#lokfotreag#hurrashbeg#konchilkuk#wobrahfmet#hrongnewit#klomurgrae#zagsmenrok#hreakgleav#wahrembeag#sarbrufeat#keltrumram#grozfarwat#mortelgeng#burngraega#klethghrom#can't believe I typed all those out#bestiary#worldbuilding#fiction writing#strix draws things

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I forgot to show you all this cool wasp I found when I was hiking in old growth forest in Missouri last month! She's an Atanycolus species, probably A. cappaerti, and she's a native stingless wasp found primarily in the eastern half of the United States. You can tell she's stingless because she has a long, skinny ovipositor at the end of her abdomen instead of a shorter, sharper stinger.

In fact, stingers are just modified ovipositors found in some members of the order Hymenoptera (wasps, bees, ants, sawflies). Originally the structure evolved so that the female could inject her egg into a safe place, whether that was a leaf or stem of a plant, or a hapless insect or spider host. But some species changed it through evolution so that it not only could more easily penetrate the skin or exoskeleton of an attacker, but inject venom as well. This not only allows some parasitic wasps to more effectively subdue and paralyze their hosts, but defend themselves and their nests as well.

A. cappaerti has a variety of insect hosts, but I was delighted to hear that this species will readily parasitize larvae of the invasive emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis). And even better news--there are other native wasps that also use the ash borer as a host! All of which means these native wasps could be used for intentional biocontrol of the invasive insects without having to bring in non-native parasitic wasps.

#wasps#wasp#insects#bugs#Hymenoptera#stingless wasps#animals#wildlife#nature#native species#invasive species#emerald ash borer#ecology#conservation#invertebrates#arthropods#Missouri#Ozarks

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eastern Shooting Star

Primula meadia syn. Dodecatheon meadia

This native perennial has a range that spans throughout the central and eastern United States, where it can be found growing in a variety of habitats with acidic to neutral soils. Its nodding flowers resemble a shooting star and are usually white or lilac in color.

This particular plant was growing in a dolomite glade, but I've also found this species growing in moist, open forests over sandstone before.

April 18th, 2024

Jefferson County, Missouri, USA

Olivia R. Myers

@oliviarosaline

#botany#Dodecatheon meadia#Primula meadia#Primula#Dodecatheon#Primulaceae#primroses#shooting star#flowers#plants#nature#glades#Missouri#ozarks#the ozarks#plant photography#nature photography#flower photography#naturecore#fairycore#cottagecore#purple flowers#native flowers#native plants#wild flowers#wildflowers#woods#forest#photography#hiking

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Text is from the Center for Biological Diversity:

For Immediate Release, February 27, 2023

Contact:

Tierra Curry, (928) 522-3681, [email protected]

Rare Milkweed Gains Endangered Species Protection, Critical Habitat

Plant Is Crucial for Migratory Monarch Butterflies in South Texas, Mexico

RIO GRANDE CITY, Texas— The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service today protected the prostrate milkweed as endangered. Only 24 populations of the plant survive, in south Texas and northern Mexico, where they serve as an important food source for pollinators like bees and imperiled monarch butterflies.

The Service also protected 661 acres of critical habitat for the plant in eight south Texas units in Zapata and Starr counties. Recent border-wall construction degraded another 20 acres of habitat that were proposed for protection last year to the point that they were unsuitable for the plant and withdrawn from designation. All populations of the milkweed in the United States are within nine miles of the border, making it one of hundreds of species threatened by wall construction.

“Protecting prostrate milkweed is a big deal for the monarch butterflies who lay their eggs on these plants as they fly through Texas after spending the winter in Mexico,” said Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “For the sake of the milkweed and all the pollinators who rely on it, it’s a relief that this important native plant finally has the safeguards of the Endangered Species Act.”

Construction and maintenance for roads, utilities, and the oil and gas industry also destroy the prostrate milkweed, and additional border-wall construction on the Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge threatens to uproot more of them. These activities and livestock grazing foster the spread of invasive buffelgrass, which is planted as livestock forage. Buffelgrass displaces native plants and is very difficult to control.

Under natural conditions the prostrate milkweed is thought to be able to persist at low densities. It produces so much nectar that far-flying pollinating insects such as tarantula hawks and large bees are so juiced up after visiting it that they can fly farther and pollinate other relatively distant prostrate milkweed populations. But as prostrate milkweed numbers and densities have declined, the plant is also imperiled by lower reproductive success and loss of genetic diversity.

Just 24 populations of prostrate milkweed remain in Starr and Zapata counties in Texas and in Tamaulipas and eastern Nuevo León in Mexico. Nineteen of those populations are rated in low condition, the remaining five are in moderate condition and none are in high condition — indicating acute imperilment.

The Endangered Species Act has been successful in keeping more than 99% of species under its protection from going extinct. But long delays in adding animal and plant species to the endangered list have heightened the perils and made recovery more difficult and expensive. For example, the Service must decide by the end of 2024 whether to protect monarch butterflies as threatened, 10 years after a petition seeking to protect them under the Endangered Species Act was filed.

The prostrate milkweed listing comes in response to a Center lawsuit to gain final decisions on protection for 241 plant and animal species threatened with extinction, including the prostrate milkweed and more than 35 others in Texas. The prostrate milkweed was the subject of a 2007 protection petition by WildEarth Guardians.

The prostrate milkweed’s low and sprawling leaves and stem wilt during droughts. But the plant’s subterranean tuber stays alive and after soaking up moisture from occasional tropical storms sends up stalks and pink and yellow flowers.

175 notes

·

View notes