#NPR Fresh Air (1983)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

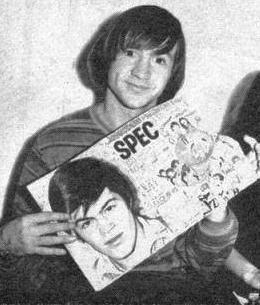

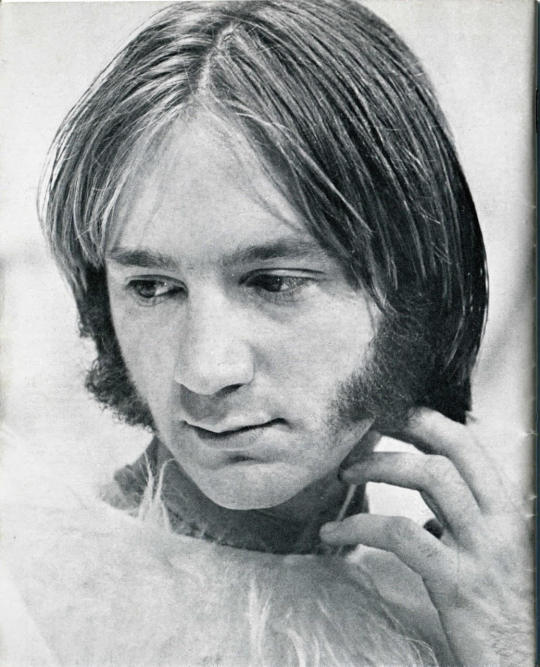

Peter Tork, 1966. Photos by Ken Whitmore, © 1978 Ken Whitmore, MPTV Images.

“He is 24, the oldest Monkee, but he wears that responsibility lightly. ‘The emotional age of all of us is 13. That’s part of the entertainer’s mentality.’ [...] After a period as a folk singer in a Greenwich Village ‘pass the basket’ coffeehouse, he became the guitar and banjo accompanist for the Phoenix Singers, working his way West. Something bright and gentle in him reminded producer Rafelson of Harpo Marx. But, unlike Harpo, Peter has a lot to say. ‘There’s a social revolution going on and the young ones are into it,’ he said. ‘The young more automatically agree to change. When they grow up, they’ll be just as antirevolutionary as their parents, but about different things. If you want something really visionary and mystic’ — he grinned and the dimples deepened into amiable furrows — ‘telepathy is the coming phenomenon. Nonverbal, extrasensory communication is at hand.’ What does he want to communicate? ‘Love. I don’t mean it to sound corny,’ he said pleadingly. ‘Dogmatism is leaving the scene. Youth is examining all the old-time premises that used to be taken totally for granted — sexual mores, artistic mores. And in Russia, the revolutionary clichés. I think there’s a genuinely democratic society just over the horizon. I hope so. I hope it achieves freedom and peace.’ Asked about his draft status, he hesitated. ‘1-Y, Unacceptable. I don’t like the army, and the army and I came to an agreement. To put it bluntly, they thought I was crazy... and maybe I am.’ He added defensively, ‘I don’t think I’m less patriotic than anyone else, maybe I’m even more. I think you should stand for what you believe in. I stand for love and peace. To my way of thinking, they’re the same thing. But the man who said ‘My country, right or wrong’ made a slight error of judgement. My country wrong needs my help. Well, I guess I’ve got myself in enough hot water.’” - interview conducted by Judy Stone for The New York Times, October 2, 1966 Peter Tork: “Well, they wouldn’t let us criticize the war in Vietnam.” Q: “Really?” PT: “Really.” TG: “Did you want to?” PT: “Yup. I actually did, to a New York Times reporter, and they made me, asked me very seriously, very strenuously, to call her and ask her to withhold that section of the interview. And I did, and she did, she was very kind about it. But it was… I look back on it and it seems kind of silly, but I think that the whole point of the project was: don’t make waves. Look like revolutionary, look like something new, but don’t make waves. On the other hand, in the experience of an awful lot of our audience, we were something new. So I can’t knock that.” - NPR, June 1983 “‘When I was a kid, before the Monkees, I was not primarily a rock and roller,’ said Tork during a 1998 interview. ‘I was primarily an acoustic folkie. For us, as acoustic folkies, the politics were very clear. We were strongly liberal, in the Pete Seeger mold. We certainly had a strong sense of right and wrong, and we certainly believed a lot that was wrong with society was the fault of the moneyed class. I think all of us to some extent believed ourselves to be socialists.’ […] It could not have been easy for someone who grew up listening to the Weavers and folk music to remain on the sidelines during such a fertile period in American politics as the late 1960s. Had Tork not strayed a second time from folk, perhaps he would have written a memorable protest song himself. But doing something like that was out of question while a member of the Monkees. Still, Tork tried at one point to break free from his ‘captors.’ ‘I thought that we had no business being in Vietnam, and I said so to the New York Times,’ Tork recalled. ‘I was asked (by Monkees’ management) to retract the statement. I called the Times and did that.’ It was, said Tork, a question of honor; he had signed a contract, and he would abide by its terms.” - We all want to change the world: Rock and politics from Elvis to Eminem (2003) (x)

#Peter Tork#Tork quotes#60s Tork#1960s#The Monkees#Monkees#<3#long read#80s Tork#1966#Peter deserved better#love his mind#The New York Times#NPR Fresh Air (1983)#We All Want To Change The World: Rock and Politics from Elvis to Eminem#can you queue it

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stuart Scott

Stuart Orlando Scott (July 19, 1965 – January 4, 2015) was an American sportscaster and anchor on ESPN, most notably on SportsCenter. Well known for his hip-hop style and use of catchphrases, Scott was also a regular for the network in its National Basketball Association (NBA) and National Football League (NFL) coverage.

Scott grew up in North Carolina, and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He began his career with various local television stations before joining ESPN in 1993. Although there were already accomplished African-American sportscasters, his blending of hip hop with sportscasting was unique for television. By 2008, he was a staple in ESPN's programming, and also began on ABC as lead host for their coverage of the NBA.

In 2007, Scott had an appendectomy and learned that his appendix was cancerous. After going into remission, he was again diagnosed with cancer in 2011 and 2013. Scott was honored at the ESPY Awards in 2014 with the Jimmy V Award for his fight against cancer, less than six months before his death in 2015 at the age of 49.

Early life

Stuart Orlando Scott was born in Chicago, Illinois on July 19, 1965 as the son of O. Ray and Jacqueline Scott. When he was 7, Scott and his family moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Scott had a brother named Stephen and two sisters named Susan and Synthia.

He attended Mount Tabor High School for 9th and 10th grade and then completed his last two years at Richard J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, graduating in 1983. In high school, he was a captain of his football team, ran track, served as Vice President of the Student Council, and was the Sergeant at Arms of the school's Key Club. Scott was inducted into the Richard J. Reynolds High School Hall of Fame during a ceremony on February 6, 2015, which took place during the Reynolds/Mt. Tabor (the two high schools that Scott attended) basketball game.

He attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and was part of the on-air talent at WXYC. While at UNC, Scott also played wide receiver and defensive back on the football team. In 1987, Scott graduated from the UNC with a B.A. in speech communication. In 2001, Scott gave the commencement address at UNC where he implored graduates to celebrate diversity and recognize the power of communication.

Career

Following graduation, Scott worked as a news reporter and weekend sports anchor at WPDE-TV in Florence, South Carolina from 1987 until 1988. Scott came up with the phrase "as cool as the other side of the pillow" while working his first job at WPDE. After this, Scott worked as a news reporter at WRAL-TV 5 in Raleigh, North Carolina from 1988 until 1990. WRAL Sports anchor Jeff Gravley recalled there was a "natural bond" between Scott and the sports department. Gravley described his style as creative, gregarious and adding so much energy to the newsroom. Even after leaving, Scott still visited his former colleagues at WRAL and treated them like family.

From 1990 until 1993, Scott worked at WESH, an NBC affiliate in Orlando, Florida as a sports reporter and sports anchor. While at WESH, he met ESPN producer Gus Ramsey, who was beginning his own career. Ramsey said of Scott: "You knew the second he walked in the door that it was a pit stop, and that he was gonna be this big star somewhere someday. He went out and did a piece on the rodeo, and he nailed it just like he would nail the NBA Finals for ESPN." He earned first place honors from the Central Florida Press Club for a feature on rodeo.

ESPN

Al Jaffe, ESPN's vice president for talent, brought Scott to ESPN2 because they were looking for sportscasters who might appeal to a younger audience. Scott became one of the few African-American personalities who was not a former professional athlete. His first ESPN assignments were for SportsSmash, a short sportscast twice an hour on ESPN2's SportsNight program. After Keith Olbermann left SportsNight for ESPN's SportsCenter, Scott took his place in the anchor chair at SportsNight. After this, Scott was a regular on SportsCenter. At SportsCenter, Scott was frequently teamed with fellow anchors Steve Levy, Kenny Mayne, Dan Patrick, and most notably, Rich Eisen. Scott was a regular in the This is SportsCenter commercials.

In 2002, Scott was named studio host for the NBA on ESPN. He became lead host in 2008, when he also began at ABC in the same capacity for its NBA coverage, which included the NBA Finals. Additionally, Scott anchored SportsCenter's prime-time coverage from the site of NBA post-season games. From 1997 until 2014, he covered the league's finals. During the 1997 and 1998 NBA Finals, Scott did one-on-one interviews with Michael Jordan. When Monday Night Football moved to ESPN in 2006, Scott hosted on-site coverage, including Monday Night Countdown and post-game SportsCenter coverage. Scott previously appeared on NFL Primetime during the 1997 season, Monday Night Countdown from 2002 to 2005, and Sunday NFL Countdown from 1999 to 2001. Scott also covered the MLB playoffs and NCAA Final Four in 1995 for ESPN.

Scott appeared in each issue of ESPN the Magazine, with his Holla column. During his work at ESPN, he also interviewed Tiger Woods, Sammy Sosa, President Bill Clinton and President Barack Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign. As a part of the interview with President Barack Obama, Scott played in a one-on-one basketball game with the President. In 2004, per the request of U.S. troops, Scott and fellow SportsCenter co-anchors hosted a week of programs originating from Kuwait for ESPN's SportsCenter: Salute the Troops. He hosted a number of ESPN game and reality shows, including Stump the Schwab, Teammates, and Dream Job, and hosted David Blaine's Drowned Alive special. He hosted a special and only broadcast episode of America's Funniest Home Videos called AFV: The Sports Edition.

Style

While there were already successful African-American sportscasters, Scott blended hip-hop culture and sports in a way that had never been seen before on television. He talked in the same manner as fans would at home. ESPN director of news Vince Doria told ABC: "But Stuart spoke a much different language ... that appealed to a young demographic, particularly a young African-American demographic." Michael Wilbon wrote that Scott allowed his personality to infuse the coverage and his emotion to pour out.

Scott also integrated pop culture references into his reports. One commentator remembered his style: "he could go from evoking a Baptist preacher riffing during Sunday morning service ('Can I get a witness from the congregation?!'), to quoting Public Enemy frontman Chuck D ('Hear the drummer get WICKED!') In 1999, he was parodied on Saturday Night Live by Tim Meadows. Scott appeared in music videos with the rappers LL Cool J and Luke, and he was cited in "3 Peat", a Lil Wayne song that included the line: "Yeah, I got game like Stuart Scott, fresh out the ESPN shop." In a 2002 segment of NPR's On the Media, Scott revealed one approach to his anchoring duties: "Writing is better if it's kept simple. Every sentence doesn't need to have perfect noun/verb agreement. I've said 'ain't' on the air. Because I sometimes use 'ain't' when I'm talking."

As a result of his unique style, Scott and ESPN received a lot of hate mail from people who resented his color, his hip-hop style, or his generation. In a 2003 USA Today survey, Scott finished first in the question of which anchor should be voted off SportsCenter, but he also was second to Dan Patrick in the 'definitely keep him' voting. Jason Whitlock criticized Scott's use of Jay-Z's alternate nickname, "Jigga", at halftime of Monday Night Football as ridiculous and offensive. Scott never changed his style and ESPN stuck with him.

Catchphrases

Scott became well known for his use of catch phrases, following in the SportsCenter tradition begun by Dan Patrick and Keith Olbermann. He popularized the phrase booyah, which spread from sports into mainstream culture. Some of the catchphrases included:

"Boo-Yah!"

"Hallah"

"As cool as the other side of the pillow"

"He must be the bus driver cuz he was takin' him to school."

"Holla at a playa when you see him in the street!"

"Just call him butter 'cause he's on a roll"

"They Call Him the Windex Man 'Cause He's Always Cleaning the Glass"

"You Ain't Gotta Go Home, But You Gotta Get The Heck Outta Here."

"He Treats Him Like a Dog. Sit. Stay."

"And the Lord said you got to rise Up!"

"Make All the Kinfolk Proud ... Pookie, Ray Ray and Moesha"

"It's Your World, Kid ... The Rest of Us Are Still Paying Rent"

"Can I Get a Witness From the Congregation?"

"Doing It, Doing It, Doing It Well"

"See ... What Had Happened Was"

Legacy

ESPN president John Skipper said Scott's flair and style, which he used to talk about the athletes he was covering, "changed everything." Fellow ESPN Anchor, Stan Verrett, said he was a trailblazer: "not only because he was black – obviously black – but because of his style, his demeanor, his presentation. He did not shy away from the fact that he was a black man, and that allowed the rest of us who came along to just be ourselves." He became a role model for African-American sports journalists.

Personal life

Scott was married to Kimberly Scott from 1993 to 2007. They had two daughters together, Taelor and Sydni. Scott lived in Avon, Connecticut. At the time of his death, Scott was in a relationship with Kristin Spodobalski. During his Jimmy V Award speech, he told his teenage daughters: "Taelor and Sydni, I love you guys more than I will ever be able to express. You two are my heartbeat. I am standing on this stage here tonight because of you."

Eye injury

Scott was injured when he was hit in the face by a football during a New York Jets mini-camp on April 3, 2002, while filming a special for ESPN, a blow which damaged his cornea. He received surgery but afterwards suffered from ptosis, or drooping of the eyelid.

Appendectomy and cancer

After leaving Connecticut on a Sunday morning in 2007 for Monday Night Football in Pittsburgh, Scott had a stomachache. After the stomachache worsened, he went to the hospital instead of the game and later had his appendix removed. After testing the appendix, doctors learned that he had cancer. Two days later, he had surgery in New York that removed part of his colon and some of his lymph nodes near the appendix. After the surgery, they recommended preventive chemotherapy. By December, Scott—while undergoing chemotherapy—hosted Friday night ESPN NBA coverage and led the coverage of ABC's NBA Christmas Day studio show. Scott worked out while undergoing chemotherapy. Scott said of his experience with cancer at the time: "One of the coolest things about having cancer, and I know that sounds like an oxymoron, is meeting other people who've had to fight it. You have a bond. It's like a fraternity or sorority." When Scott returned to work and people knew of his cancer diagnosis, the well-wishers felt overbearing for him as he just wanted to talk about sports, not cancer.

The cancer returned in 2011, but it eventually went back into remission. He was again diagnosed with cancer on January 14, 2013. After chemo, Scott would do mixed martial arts and/or a P90X workout regimen. By 2014, he had undergone 58 infusions of chemotherapy and switched to chemotherapy pills. Scott also went under radiation and multiple surgeries as a part of his cancer treatment. Scott never wanted to know what stage of cancer he was in.

Jimmy V Award

On July 16, 2014, Scott was honored at the ESPY Awards, with the Jimmy V Award for his ongoing battle against cancer. He shared that he had 4 surgeries in 7 days in the week prior to his appearance, when he was suffering from liver complications and kidney failure. Scott told the audience, "When you die, it does not mean that you lose to cancer. You beat cancer by how you live, why you live, and in the manner in which you live." At the ESPYs, a video was also shown that included scenes of Scott from a clinic room at Johns Hopkins Hospital and other scenes from Scott's life fighting cancer. Scott ended the speech by calling his daughter up to the stage for a hug, "because I need one," and telling the audience to "have a great rest of your night, have a great rest of your life."

Death

On the morning of January 4, 2015, Scott died of cancer in his home in Avon, Connecticut, at the age of 49.

Tributes

ESPN announced: "Stuart Scott, a dedicated family man and one of ESPN's signature SportsCenter anchors, has died after a courageous and inspiring battle with cancer. He was 49." ESPN released a video obituary of Scott. Sports Illustrated called ESPN's video obituary a beautiful and moving tribute to a man who died "at the too-damn-young age of 49." Barack Obama paid tribute to Scott, saying:

I will miss Stuart Scott. Twenty years ago, Stuart helped usher in a new way to talk about our favorite teams and the day's best plays. For much of those twenty years, public service and campaigns have kept me from my family – but wherever I went, I could flip on the TV and Stu and his colleagues on SportsCenter were there. Over the years, he entertained us, and in the end, he inspired us – with courage and love. Michelle and I offer our thoughts and prayers to his family, friends, and colleagues.

A number of National Basketball Association athletes—current and former—paid tribute to Scott, including Stephen Curry, Carmelo Anthony, Kobe Bryant, Steve Nash, Jason Collins, Shaquille O'Neal, Magic Johnson, Dwyane Wade, LeBron James, Michael Jordan, Bruce Bowen, Dennis Rodman, James Worthy and others. A number of golfers paid tribute to Scott: Tiger Woods, Gary Player, David Duval, Lee Westwood, Blair O'Neal, Jane Park and others. Other athletes paid tribute including Robert Griffin III, Russell Wilson, Jon Lester, Lance Armstrong, Barry Sanders, J. J. Watt, David Ortiz and Sheryl Swoopes. UNC basketball coach Roy Williams called him a "hero." Arizona Cardinals head coach Bruce Arians said: "We lost a football game but we lost more this morning. I think one of the best members of the media I've ever dealt with, Stuart Scott, passed away."

Colleagues Hannah Storm and Rich Eisen gave on-air remembrances of Scott. On SportsCenter, Scott Van Pelt and Steve Levy said farewell to Scott and left a chair empty in his honor. Tom Jackson, Cris Carter, Chris Berman, Mike Ditka and Keyshawn Johnson from NFL Countdown shared their memories of Scott.

During Ernie Johnson, Jr.'s acceptance speech for his 2015 Sports Emmy Award for Best Studio Host, he gave his award to Scott's daughters, saying it "belongs with Stuart Scott". At the 67th Primetime Emmy Awards and at the 2015 ESPY Awards, Scott was included in the "in memoriam" segment, a rare honor for a sports broadcaster.

Filmography

He Got Game (1998)

Disney's The Kid (2000)

Drumline (2002)

Love Don't Cost A Thing (2003)

Mr. 3000 (2004)

Herbie: Fully Loaded (2005)

The Game Plan (2007)

Enchanted (2007)

Just Wright (2010)

Television

Arli$$ (2000)

I Love the '80s (2002)

Soul Food (2003)

She Spies (2005)

I Love the '70s (2003)

One on One (2004)

Stump the Schwab (2004–06)

Dream Job (2004)

Teammates (2005)

I Love the '90s (2004)

I Love the Holidays (2005)

I Love Toys (2006)

Black to the Future (2009)

Publications

Scott, Stuart; Platt, Larry (2015). Every Day I Fight. Blue Rider Press. ISBN 978-0-399-17406-3.

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

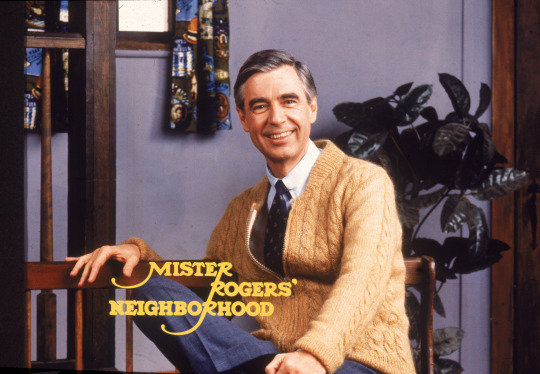

Discovering the Neighborhood of Make-Believe in the NPR archives

In the 1978 Christmas Eve broadcast of NPR's Weekend All Things Considered, Mr. Rogers explains his decision to invite Santa to his Neighborhood of Make-Believe — he wanted it on the record that Santa would never watch children while they’re sleeping. This nearly 40 year-old interview with the star of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was the first delightfully unexpected discovery I made while searching through NPR's in-house digital archive. The interview was contemplative and funny and, lucky for me, there was more. Mr. Rogers was interviewed on NPR over a dozen more times between 1975 and 2002. What’s special about these interviews is their incredibly slow pace. And it’s not just the way Mr. Rogers talks--it’s the way he reveals the thoughtfulness and deep compassion for the perspective of children that went into every creative choice on the show.

Here are the greatest hits from nearly thirty years of NPR interviews with Mr. Rogers.

All Things Considered, 6/5/1975

Bob Edwards introduces him by saying, “Mr. Rogers is, for adults anyway, almost unbearably slow paced.”

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Bob Edwards: Mr Rogers is, for adults anyway, almost unbearably slow-paced. Steven Banker asked Fred Rogers to account for the difference.

Mr. Rogers: I think it depends who you are. I happen to be a person who is rather well-modulated in his way of speaking and in his way of dealing with feelings. And so consequently, I am myself. And I think maybe that’s the most important thing that I can be to children on television, is myself.

All Things Considered, 12/12/1979

39 days into the Iranian Hostage Crisis, Mr. Rogers returns to All Things Considered to discuss with Susan Stamberg how parents can use this time to teach their children to, “develop empathy for all sorts of people.”

NPR Archives

Susan Stamberg: A crisis situation presents a tremendous opportunity to really teach lessons in morals and values, doesn’t it? It’s a way to acknowledge the fact that there’s anger, but you can go beyond that and say, but this is the wrong way to express your anger. Taking prisoner is the wrong way.

Mr. Rogers: I have trouble with right and wrong. But I know what you’re saying. And I think that it’s more helpful to say, this is not the way we do it in our family. This is not the way we would do it in our country. And then go on to say how we as a family feel. And our notion of how we as a country feel is such and such. And this gives the kids a very secure sense of belonging to a family, to a country that has these ideals.

Morning Edition, 3/18/1983

Eight years after his initial interview with Mr. Rogers, Bob Edwards admits he has converted to the slow-speed philosophy of the Neighborhood.

Getty Images

Bob Edwards: I have a confession, I’m almost 36 years old and I enjoy your show. It’s not so much what you’re doing with children I mean I see that now as a father, it’s television and something is going on there. You use the medium so well.

Mr. Rogers: Anybody likes to be in touch with somebody who’s honest. We all do… I think that the box, there’s a certain safety in the box. And I wonder — when children see me on the street they invariably say, how did you get out? And I try my best to explain what television is and that it’s a picture and that I’m a real person and that’s why I could be there at that moment. They think that you’re so big. And I invariably say to them, you know the scary things you may see on television, could never come and visit you.

Fresh Air, 11/13/2002

Mr. Rogers appears on NPR for the last time a year before he passed away in 2003. In this Fresh Air interview with Barbara Bogaev he reveals more about his life outside the “Neighborhood of Make-Believe” than in any of his previous appearances.

Mr. Rogers: I had every imaginable childhood disease, even scarlet fever, and so whenever I was quarantined—and you know, they used to quarantine people for chicken pox and all of those things—I would be in bed a lot, and I certainly knew what it was like to use the counterpane as my neighborhood of make-believe, if you will. But I had puppets.

Barbara Bogaev: You mean, the window? You would use what? Finger puppets or shadow puppets, or what?

Mr. Rogers: And things on the bed. I would put up my knees and they would be mountains, you know, covered with the sheet, and I'd have all these little figures moving around, and I'd make them talk. And I can still see my room, and I'm sure that was the beginning of a much later neighborhood of make-believe.

Sarah Wilson is a public history intern with NPR’s RAD team. She works with the RAD team to uncover NPR history and collect oral history interviews with notable current and former staff.

#NPR#npr rad#mr. rogers#mr. rogers neighborhood#audio preservation#archival audio#nprchives#allthingsconsidered#morningedition

264 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Prine, a wry and perceptive writer whose songs often resembled vivid short stories, died Tuesday in Nashville from complications related to COVID-19. His death was confirmed by his publicist, on behalf of his family. He was 73 years old.

Prine was hospitalized last week after falling ill and put on a ventilator Saturday night, according to a statement from his family.

Music Features

John Prine's Songs Saw The Whole Of Us

Even as a young man, Prine — who famously worked as a mailman before turning to music full-time — wrote evocative songs that belied his age. With a conversational vocal approach, he quickly developed a reputation as a performer who empathized with his characters. His beloved 1971 self-titled debut features the aching "Hello In There," written from the perspective of a lonely elderly man who simply wants to be noticed, and the equally bittersweet "Angel From Montgomery." The latter song is narrated by a middle-aged woman with deep regrets over the way her life turned out, married to a man who's merely "another child that's grown old."

Bestowing dignity on the overlooked and marginalized was a common theme throughout Prine's career; he became known for detailed vignettes about ordinary people that illustrated larger truths about society. One of his signature songs, "Sam Stone," is an empathetic tale of a decorated veteran who overdoses because he has trouble readjusting to real life after the war. (Prine has said he based the protagonist around friends who were Vietnam War veterans, and also soldiers he encountered during his own two-year stint as an Army mechanic.)

Tiny Desk

John Prine: Tiny Desk Concert

Like "Sam Stone," many of Prine's songs also had an uncanny ability to address (if not predict) the societal and political zeitgeist. The understated 1984 song "Unwed Fathers" illustrates pernicious double standards pertaining to gender: The titular group "can't be bothered / They run like water, through a mountain stream," while the young women they impregnate are shamed and face consequences. Recorded for John Prine, "Your Flag Decal Won't Get You Into Heaven Anymore" criticizes people who use piety and patriotism as a cover for supporting an unjust war — a theme he'd revisit on 2005's "Some Humans Ain't Human," which pulls no punches slamming both hypocritical people and the Iraq War started by George W. Bush.

John Prine: In Memoriam

But like fellow songwriting iconoclast Shel Silverstein, Prine also cloaked his pointed commentary within whimsical wordplay. "Some Humans Ain't Human" claims that inside the heart of these turncoats is "a few frozen pizzas, some ice cubes with hair and a broken Popsicle," while "Dear Abby" has a lilting, rollicking rhythm to its verses, as it gently chides advice-column complainers to count their blessings. "Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow)" uses both absurdity (an altar boy struck by a train) and the mundane (a bench makeout) to encourage people to stay positive and have gratitude.

And "Christmas In Prison" boasts one of his best lyrics — "She reminds me of a chess game with someone I admire" — while embodying his quiet irreverence. "It's about a person being somewhere like a prison, in a situation they don't want to be in, and wishing they were somewhere else," he wrote in the liner notes to 1993's Great Days: The John Prine Anthology, adding that "I used all the imagery as if it were an actual prison. ... And being a sentimental guy, I put it at Christmas."

Prine was born on October 10, 1946, to parents with strong family ties to Paradise, Kentucky, a place that later served as the backdrop to "Paradise," his cautionary tale about a coal country town destroyed and discarded by corporate interests.

Raised in Maywood, a suburb of Chicago,, the young Prine devoured 45s from Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash and Little Richard, and soaked up the country music his father loved, such as Hank Williams Sr., Ernest Tubb and Roy Acuff. More crucially, Prine learned rudimentary guitar skills from his oldest brother, Dave, a folk fan who memorably gifted him a Carter Family LP. "I learned all those songs," he told NPR's Terry Gross in 2018. "And not too long after that, I started writing when I was 14. And my melodies always came out like old-timey country stuff." Around this time, Prine also started to learn finger-picking by playing songs by Elizabeth Cotten and Mississippi John Hurt, he added: "I'd sit in the closet in the dark in case I ever went blind, to see if I could play."

Although Prine also started taking guitar lessons at Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music starting in fall 1963, he still wasn't considering pursuing music as a full-time career. In fact, he was working as a mailman and playing gigs at night on the side when a generous live review from critic Roger Ebert in late 1970 boosted his reputation in Chicago's nascent folk scene. A record deal with Atlantic Records came in early 1971, after then-executive Jerry Wexler saw Prine perform three songs during a Kris Kristofferson set at the Bottom Line in New York City.

John Prine, hanging out at Georgia State College in 1975.

Tom Hill/WireImage

Prine received a Grammy nomination for Best New Artist in 1972, on the strength of his debut, and started turning out records at a brisk pace for the rest of the 1970s. Almost immediately, his songs were covered by other artists: Bonnie Raitt did a version of "Angel From Montgomery" (as did John Denver and Tanya Tucker), while Bette Midler, Everly Brothers, Swamp Dogg and, later, the Highwaymen also recorded Prine-penned songs.

Being in the spotlight didn't come naturally. "I had a difficult time listening back to them because I was so nervous," he told Fresh Air about his early records. "I didn't expect to do this for a living, be a recording artist. I was just playing music for the fun of it and writing songs to ... that was kind of my escape, you know, from the humdrum of the world."

But Prine's early success allowed him to start approaching his career on his own terms. With manager Al Bunetta, he formed the independent label Oh Boy Records in 1981, launching it with a Christmas single, "I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus." Prine slowed down his output in the '80s and '90s but expanded his sonic purview, co-writing "Jackie O" with John Cougar Mellencamp for the latter's hit 1983 LP Uh-Huh and collaborating with members of Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers for his 1991 album The Missing Years, which won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album. (Prine also won in the same category for 2005's Fair & Square.)

Starting in the mid-'90s, Prine also dealt with several serious health issues. He had a cancerous tumor in his neck removed in 1996, successfully beat lung cancer in 2013 and had a heart stent implanted in 2019. In 2018, he admitted to NPR's Terry Gross that his 1996 cancer surgery changed his voice.

"It dropped down lower, and it feels friendlier to me," he said. "So I can actually sit in the studio and listen to my singing play back. Before, I'd run the other way." He debuted his new voice — which did feel a bit rougher of comfort, like a rock swathed in moss — with 1999's In Spite of Ourselves, which featured duets on covers with female artists such as Iris DeMent, Patty Loveless and Lucinda Williams. He released a kindred-spirit sequel in 2016, For Better, or Worse, that also featured DeMent, in addition to duets with contemporary artists Miranda Lambert, Kacey Musgraves and Morgane Stapleton.

John Prine at the Edison Hotel in Times Square, 1999.

New York Daily News Archive/NY Daily News via Getty Images

Prine's career received another boost more recently, too, after his work was championed by modern Americana acts such as Jason Isbell and Amanda Shires — two artists with whom Prine collaborated — Sturgill Simpson and Margo Price. In 2019, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the year after releasing The Tree of Forgiveness, his first album of all-new original songs since Fair & Square. The album featured co-writes with Dan Auerbach and long-time foils Pat McLaughlin and Keith Sykes, and debuted at No. 5 on Billboard's Top 200.

The Tree of Forgiveness ends with a song called "When I Get to Heaven," a detailed look at what Prine said he intended to do after he dies: start a band, see dearly departed family members, order a cocktail, shake God's hand and encourage rampant forgiveness. (In a nod to his usual wry streak, he also said he'd enjoy a cigarette that's "nine miles long.") The lyrics are sentimental and freewheeling, making it clear that Prine planned to keep the good times going up in heaven. It's likely that the song was intended to be a winking bit of foreshadowing about his own mortality, although now, perhaps it's better interpreted as Prine providing a blueprint for how to live life with gusto while you're still here.

0 notes

Video

youtube

James Victor "Vic" Chesnutt (November 12, 1964 – December 25, 2009) was an American singer-songwriter from Athens, Georgia. His first album, Little, was released in 1990, but his breakthrough to commercial success didn't come until 1996 with the release of Sweet Relief II: Gravity of the Situation, a tribute album of alternative artists covering his songs.

Chesnutt released 17 albums during his career, including two produced by Michael Stipe, and a 1996 release on Capitol Records, About to Choke. His musical style has been described by Bryan Carroll of allmusic.com as a "skewed, refracted version of Americana that is haunting, funny, poignant, and occasionally mystical, usually all at once".

Injuries from a 1983 car accident left him partially paralyzed; he used a wheelchair and had limited use of his hands.

An adoptee, Chesnutt was raised in Zebulon, Georgia, where he first started writing songs at the age of five. When he was 13, Chesnutt declared that he was an atheist, a position that he maintained for the rest of his life.

At 18, a car accident left him partially paralyzed; in a December 1, 2009 interview with Terry Gross on her NPR show Fresh Air, he said he was "a quadriplegic from [his] neck down", and although he had feeling and some movement in his body, he could not walk "functionally" and that, although he realized shortly afterward that he could still play guitar, he could only play simple chords.

On December 25, 2009, at the age of 45, Chesnutt died from an overdose of muscle relaxants that had left him in a coma in an Athens hospital. In his final interview, which aired on National Public Radio 24 days before his death, Chesnutt said that he had "attempted suicide three or four times [before]. It didn't take."

According to him in the same interview, being "uninsurable" due to his quadriplegia, he was $50,000 in debt for his medical bills, and had been putting off a surgery for a year ("And, I mean, I could die only because I cannot afford to go in there again. I don't want to die, especially just because of I don't have enough money to go in the hospital.").

-Wikipedia

44 notes

·

View notes

Link

New story on NPR: 'Fresh Air' Reflects On The Psychedelic Movement https://ift.tt/35qUeiF

0 notes

Photo

You might recall older posts featuring audio and/or quotes from Peter's June 1983 interview with NPR (such as here, here, here, and here). There are also some audio snippets on this fan page's YouTube channel. But since the full audio is too long to upload to YouTube, I transcribed the full audio interview, and thought I'd share that transcript here for anyone who might be interested in reading this snapshot of a moment in time.

Terry Gross: "Um, you wanna wait for the coffee before we start?" Peter Tork: "Yes, let’s wait for the coffee." TG: "Good. It’ll be a couple of minutes. We’re waiting for the coffee. Yeah." PT: "Push the button that says stop. [long silence] Does he have to get a key to stop the tape machine? (chuckles)" TG: "So, soon as the coffee’s ready, we’ll…" PT: "We’ll just hit it. (Speaks louder) Okay, now, the thing about the songs is, snatches, this is that, the piece of this, that’s all right, but if you put on songs, then I’m just gonna be the whole..." [recording cuts off]. TG: "Are you comfortable talking about The Monkees?" PT: "It’s a mixed bag. Sometimes I am. Actually, to tell you the truth, I’m not comfortable but it’s not because I… about talking about The Monkees, it’s because I haven’t had a cigarette since yesterday." TG: "Do you wanna light one up?" PT: "Noooo." TG: "Oh, you’re trying to stop." PT: "Well, I’m trying to put it off." TG: "(laughs) Savor it a little." PT: "Put off the next cigarette for, well, hopefully for a very long time, but just not smoke one right now." TG: "Okay. How did you first hear about the Monkees audition?" PT: "Stephen Stills called me and said, 'Go try out.'"

TG: "He auditioned?" PT: "I don’t know whether he auditioned exactly, or whether he had just met the producers socially, but… Steve was a friend of mine on the Village streets in early 60s. He, as a matter of fact, hit town and became instantly known as that guy who looks like Tork, which was my name in those days. And I ran across him on the street. I said, 'I know who you are. You’re the kid who looks like me.’ He said, 'I know who you are. You’re the kid I’m supposed to look like.’ Anyway, so we cut back again to a couple of years later, and Steve knows this guy, and it turns out to be Bob Rafelson, one of the producers, who says to him, in his own inimitable way, 'Well, we like ya a lot, but your hair and teeth are wrong for our production, they ain’t photogenic. You know anybody who looks like you who’s got good hair and teeth?’ Stephen said, 'My friend Peter.’ And so Stephen called me and said, 'Go try out for this thing.’ And I said, 'Yeah, yeah, sure, Steve, yeah, right, instant success, gimme a break.’ And he said, 'No, no, really, try out.’ 'All right, all right, all right.’ So, you know, I took my hard-earned savings, which I’d been making washing dishes at this club in southern, way southern California, fifty miles south of Hollywood, and took a bus up to Hollywood and back down again, and up and down for auditions. And eventually won the part." TG: "What was the audition like?" PT: "Well, it started off with just a huge gang of kids in the office. The office had one secretary type and two offices, one on either side. You went into which ever one was free next and if they didn’t like you, that was it. If they did like you, then you went into the next guy’s office when he was free, and if he liked you, then they sent you to this — they gave you a, what they called a personality interview: they just had the cameras running on the set of I Dream Of Jeannie or something, and they asked you questions. And then, if they thought that was… that was actually also, I think, a photogenic test — photo genesis test (chuckles): Were you born in the camera? But after that, then came the regular screen test, which was scripted, and they had a set there, and a director, and he said, 'Do this and do that, and don’t do this and do this other thing.’ And they had, by that time, had gotten down to eight guys, and they divided them up into teams of two, and each one of them did the screen test with the script and the stage actions: 'Hey, man, what’s really the matter?’ 'Aw, I don’t know, it’s about Celia, you know.’ 'Yeah, yeah, I know, man.’ Like that." TG: "So that was the audition." PT: "That was, well, that was the whole audition process." TG: "Did, did they test you for chemistry with each other, since this was a band that was put together by producers?" PT: "No, they made, they made their assumptions and shot. They said, Well, we need one of these and one of these, two from column A and one from column B." TG: "Yeah, so, so what were the types that you were supposed to fit?" PT: "Well, I actually think that what they did… They didn’t just say, 'Actually, we need one of each of these.' What they said was, 'We’re going to need a bunch of qualities and pretty much the qualities… and we need them somehow or another combined among these guys.' I think basically one of the reasons I was chosen was — I can think of two good reasons why I was chosen. One is that I brought that character of the dummy to the audition. And they needed an odd man out, a guy who is like a little, you know, slightly turned from the other guys; straight-ahead rock and roll band, and one kind of simpatico, simplicico kind of a guy, and that was my character. And so that was one of the reasons why I was chosen. The other reason I think I was chosen is because I did the screen test in one take. At least, I thought it was impressive, I hope they did, too. In any case, it was like that, I got — I was the odd man out, Davy was the little British or romantic, and then two other guys, one of them light and crazed, and the other kind of dark and serious. And so that was the way it was balanced out." TG: "Were you asked to watch Beatles movies or listen a lot to Beatles records to develop the kind of sound and image that they had?" PT: "No." TG: "Were you self-conscious of The Monkees being considered to be like a Beatles imitation band?" PT: "Well, I — there was a lot of criticism to that effect and I think I took it to heart, and now I think I took it to heart too much. Because, really, it was, I think in some ways, Micky and Davy had a healthier attitude about it as I look back on it now. They didn’t go for that imitation this or organic that, you know, they just read their scripts, they came to the studio and read their parts, and that was all they ever cared about doing. You know, 'Give me a part and pay me at the end of the week.’ That’s all. And if I’d had that attitude, I would have been a lot happier. I would have been able to not worry. Because I heard a lot of different criticisms — and it all sounded as thought it was coming from one seriously important source, to me in those days. That was how I was. And I now see that each person had their own little carping to do. For instance, nobody ever said, to, in my knowledge, in those days, that we were a bunch of talentless actors. Everybody said we were talentless musicians, but not talentless actors. Because in Hollywood, we were respected pros doing what we had to do, cranking out this stuff week in and week out. You got it out, you were a pro; that was all anybody cared about in Hollywood. And so I said, Well, at least we had that much respect.’ I later find out that the struggling New York actors crowd are calling us talentless actors. But what I heard was the struggling musicians crowd in L.A., and all of the would-be-goods that are going, Well, these guys don’t play their own instruments,’ and all that… horseradish." TG: "You find that the rap has changed about the program? Because so many people look back on it affectionately now as being, like, a real pop piece from that period?" PT: "I don’t — it’s a good question. I don’t know whether the rap itself has changed, but I’m hearing more good rap about it. Which maybe comes to the same thing." TG: (laughs) PT: "You’re laughing because I spilled my coffee." TG: "Because you spilled your coffee, yeah. Did the studio control your personal life or your image? Like, was it okay to have girlfriends?" PT: "Oh, sure." TG: "Um, was it okay to be seen with them?" PT: "It’s okay to have sex. (laughs)" TG: "(laughs) You never know with studios, like how much control they’re exerting or what they want you to look like to your public." PT: "Well, they wouldn’t let us criticize the war in Vietnam." TG: "Really?" PT: "Really." TG: "Did you want to?" PT: "Yup. I actually did, to a New York Times reporter, and they made me, asked me very seriously, very strenuously, to call her and ask her to withhold that section of the interview. And I did, and she did, she was very kind about it. But it was… I look back on it and it seems kind of silly, but I think that the whole point of the project was: don’t make waves. Look like revolutionary, look like something new, but don’t make waves. On the other hand, in the experience of an awful lot of our audience, we were something new. So I can’t knock that." TG: "Do you think you would have been more of an activist if you weren’t part of TV at the time?" PT: "I don’t know. I never did march, you know, I never did carry a sign. The only thing I ever did was a sit-down strike someplace. Not much. You know, I never really did get into activism, and I don’t know whether it’s just because I’m a flat-out coward or I have some deep understanding of the cosmic truth of the fact that it doesn’t do any good or whatever, in whatever case, that’s just — that’s what it is, I don’t do it much." TG: "Bob Rafelson, who was one of the producers of the show, is now also known as a director of such films as Five Easy Pieces. Have you kept in touch with him at all?" PT: "No." TG: "Did you, like, go to see his other movies?" PT: "I happen to have seen some of the other movies… Of course I saw Five Easy Pieces because we were still associated with those guys as that movie was being put together. I mean, Easy Rider, and then I saw Five Easy Pieces because it was Jack Nicholson who helped us make the movie Head, the Monkee movie. And, and I think, I think Jack is super. And of course, one of the things that I — I have a feeling about Jack because I see the crazy guy that he portrays on screen and I see him in life and he’s still got that, that something, you know, out of bounds is still there, and still, in his actual character, he is one of the great open-minded, open-hearted sweeties that I know. And to see a man with that, these vast, seemingly vast, differences, working and playing these crazed people on screen, and still — I mean, the reason that he’s as big a star as he is, is because he does have the capacity to be abstract about his own work. You should have heard, you should have seen what it was like working with him. He’s a great technician, which is one of the great attributes. You can’t be a crazy maniac like that and not be a good technician if you want to have a career. Because you’ll just go out of bounds without any kind of viewing. And… wow, how’d we get off on that?" TG: "Did you want to pursue acting after The Monkees?" PT: "I didn’t care what I did. I, I’m an entertainer. If I act, or play music, or like I’m doing tonight at Godfrey Daniel in Bethlehem, if I do that… I have a rock band now, it’s called The Peter Tork Project and we’ll probably be swinging through here. And we play thumping rock and roll, we just really beat the bejesus out of things and really stomp. And we have a hard time getting people to believe it, because I do my acoustic act and it depends almost entirely on rapport, and I don’t rock out too much because how much rock and roll can you do on an acoustic guitar or a piano? But… I do, so it’s very, a kind of quietish show, it’s a nice, mild show." TG: "What kind of material do you play solo?" PT: "Well, I do essentially… it’s like there’s an overlap. I do a large part of the same material in both shows. I do do some old Monkees songs, just because I know people want to hear that kind of stuff. And I do do some oldies, ‘50s rockers. And with the band, then we go on to the more heavy rock and roll, the band plays that and rockier stuff. And acoustically I play that and farther out stuff, more ballads, some… a J.S. Bach piece on the piano, one, count ‘em, one. And… like that. So, it’s old, old tunes; I play some more introspective stuff in an acoustic set." TG: "What kind of music do you listen to when you have time to listen?" PT: "Baroque, reggae, current pop from time to time if I happen — I don’t buy current pop records but I get them from my family for gifts and so on. I like Men At Work, I got that for Christmas, I thought it was great." TG: (laughs) PT: "That kind of stuff. The Police. Good — I like good music in almost every form. About the only kind of music that I really have a very hard time taking is opera, and Mozart. For some reason, Mozart I think is awful. I don’t know how come he’s so revered and so treasured. Out of about every dozen pieces that I hear, I think one is inventive and interesting, and the other seem to me just to be scales with flourishes." TG: "Well, I’ll send you all the angry mail when we get it. (laughs)" PT: "No thanks!" (laughter) TG: "Peter Tork is my guest, if you’re just joining us, who got started in, um, and came in very young when he was in The Monkees." PT: "Wait a minute, wait a — that’s not my start! I was playing in the Village for two and a half years. (jokingly) Made his mark in the entertainment industry, you might say, that, that would be fair." TG: "What kind of material were you playing in the Village?" PT: "Folk songs. Just the old folk songs, and 'Blowin’ In The Wind,' and protest songs and folk songs, five-string banjo stuff." TG: "Word was on The Monkees show that it was really studio musicians who were doing the instrumental part while The Monkees were actually doing the singing. Is that true?" PT: "The first two records. After that, we did a record all by ourselves, almost all by ourselves. And then after that, we went into a mixed mode, where it was a professional drummer and I’d be playing bass, or, you know I’d be playing guitar and we’d have a professional bass player, or something like that. At the outset it was — and the thing was that nobody was sure whether we could play, nobody had any idea of how much time. I mean, they really, you know, when you hire a professional studio musician, you know what you’re getting, you know that you can knock off a complete track of two tunes in three hours, maybe more. Just take them in, put the music in front of them, and hit it. And say, More of this, less of that, and okay, you got it. And that’s the way it goes. And they just didn’t know what it was like, and so because our services were needed most critically for making the TV series, it was just regard… also, Donnie Kirshner didn’t like to have people who couldn’t be told what to do. As a matter of fact, you may have noticed that, after he and The Monkees parted company, he decided that The Monkees were not plastic enough for him, went and did the Archies." TG: "Did he organize them also by audition?" PT: "The Archies? You’re kidding." TG: "I don’t know the whole folklore of the Archies." PT: "You know — have you ever seen an Archies comic book?" TG: "Yeah, oh! Of course. What am I thinking? Right." PT: "The Archies were those comic book characters, and whatever singers were willing to do what Kirshner paid them to do, did the records. And after that, they left. There were never any Archies, there never were. (laughs) Like I said, The Monkees were too real for Don Kirshner." TG: "Did you think of Kirshner as being an absurd character?" PT: "Yes." TG: "But powerful." PT: "Well, in his time he was powerful enough. He just was one of those characters whose set up and system happened to jibe with the commercial demand of the times. I don’t think Kirshner knew what he was doing at one level. At another level, he knew perfectly well what he was doing. He was… he listened to music, and he created music that he liked, and it sold millions to thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds." TG: "I’m getting the feeling that you were in a kind of awkward position of kind of understanding what kind of manipulation was happening and at the same time being willing to go along with it because it was good for your performing career." PT: "Well, I don’t know whether it was good for my performing career. The reason I went along with it is because I never took any initiative of anything on my own account. Really basically, I just did wherever I was pointed. You know, Stephen said, ‘Go try out,’ I tried out. They said, ‘Come here, do this.’ I did that. ‘Sign here.’ I signed there. And really, I’m just — I’m only recently now getting to the point in my life where I’m beginning to say, ‘Let me figure this out. What is it that I really want? What steps do I have to take, and what…’ And even then, you know, I have to recognize that I have no control over events. All I can do is say, ‘This is the kind of thing that I’d like, and this is the kind of thing that I have to do to make my chances better.’ And then I do that, and then I have to just let the results be whatever they are, to get into trying to make results happen, you know. As a matter of fact, in some ways that was one of the problems that… when I broke up with The Monkees, I left because I couldn’t get those guys back into the studio to do the same kind of thing that we’d done on our third album, which was Micky on drums, Michael on guitar, me on piano, our producer on bass, Davy Jones playing rhythm sections, and then hiring the occasional string player or something like that. Micky said, 'You can’t go back.' He thought he was Thomas Wolfe. And Davy said, 'I don’t wanna be banging a tambourine day in, day out. You guys, it takes you 54 takes to get your parts down, I’ve got my part down first take. Just bang a tambourine. I’m sick of banging a tambourine, Peter, I hope you don’t mind.’ 'Okay, Davy.’ And so we went into this mixed mode. But I wanted the guys to be a real, live group. I had this Pinocchio/Geppetto complex, you know. And when they wouldn’t go for it, I really — it burned me out. And there I was being burnt out because things wouldn’t happen my way, and it was a case of His Majesty The Baby, trying to, you know, have his own way. If I had had the good sense God gave me, I might have noticed that I was having my own personal way, that is, in the sense that I wanted for myself was happening. I could be in the studio playing bass or guitar or piano on every single cut The Monkees did from then on if I wanted to, but that wasn’t enough for me, I wanted things for other people to do, otherwise I wanted to produce and direct and write the script for the whole shebang." TG: "Why did you want everyone to be playing? Because you thought it was more honest? Or was there another reason?" PT: "I thought it was more honest, I thought it was a bigger deal, I wanted a real live group, I thought that this was the way things were done; I was a victim of the same illusions that other people were criticizing us for shattering in their lives. In other words, you’re not a — you don’t just do this all by yourselves, you’re not an organic group, you don’t this, you don’t that, and how could you, you’ve broken my heart.’ As if, you know, as if we’ve broken their heart, as if it wasn’t the shattering of false illusions. If you hang on to false illusions, of course your heart’s gonna get broken." TG: "Did you try to organize the band to maybe rebel against —" PT: "Mh-hm." TG "— the producer." PT: "Well, we did organize the band, and we did get — rebel against Don Kirshner, but it was Mike and me wanting to — each for reasons of our own — and Micky and Davy went along. And then we did the thing, and then everybody said, 'Well, that’s enough of that, thanks very much.’ And I went, 'No, no, no, you’ve got to do it the way we planned, the way I had in mind for us to do,' you know. The fact that everybody went along with what looked like my plan obscured my vision of the fact that everybody was doing what it was they thought they had to do for reasons of their own. And when their reasons changed, and their behavior changed, and my plan didn’t change, I went after them screaming to try to mend my shattered illusions. What a jerk." TG: "(laughs) How did being a television star and a recording star affect your schooling and your ability to have friendships and things like that?" PT: “I don’t know that it affected my ability to have friendships. Basically I don’t think I knew how to be or have a friend beforehand, and I don’t think I learned while I was in that operation. I mean, I had some good buddies, you know, but that wasn’t the same thing, I didn’t really understand. There was only one person in my life that I could turn to when I was hurting who happened somehow to know what it was, what it took to stop me hurting, and that was a woman named Karen Harvey, who later joined me on the West Coast. And I thought, well, here’s a friend come to join me and this will be a real friend. And we were pretty good friends, I guess, but there wasn’t any that, you know, that — I didn’t know what a friend did in a sense of how, on a day-to-day basis, do you maintain your friendships, do you go out of your way to make sure that things are nice and right and, you know, the kind of work that a friendship takes. You don’t just have a friendship without work. And I didn’t know that. And I’m not so sure I know it now. I can say it, but I don’t know if I have, I have the real gut understanding it takes. But in any case, so that… And my schooling, the reason that I was in entertainment was because I’d flunked out of college for the second time, and I never did finish and get a graduate — I mean, I never did get a bachelor’s degree. And to this day, I haven’t got one and I don’t know whether I ever will." TG: "Well, you don’t exactly send resumes around when you’re playing concerts. (laughs)" PT: "No, they didn’t ask me for my degree when they asked me to play Bethlehem. At the Godfrey Daniel tonight in Bethlehem, PA. Those of you who are within driving distance of there, who are within the sound of my taped voice now should hustle out there and take your money so that you can get in." TG: "Speaking of money — how much profits did people in the band, of The Monkees, have, from the millions of records that were sold, and the TV profits and syndication?" PT: "We got the usual — we got standard minimum shares of the TV show and the records. We got a raise, a modest substantial raise, some, you know, medium kind of a raise, after about six months they gave us a raise. We always got the standard record deal, which was: the group gets five points, which was five percent of ninety percent, and so we split one and a quarter points, which is, what, one and three tenths percent each person of whatever the going price was. And we get that today. If they sell a record, The Monkees Greatest Hits album is still on the Billboard middle-of-the-road or some — there’s some special chart that Billboard has that we’ve been on for weeks and weeks and weeks and weeks." TG: "How do you feel about that?" PT: "Well, it’s money, I don’t care." TG: "Did you retire as a wealthy young man from the —" PT: "No. No, I didn’t. I retired as a man with some indeterminate amount of money which somehow indeterminately ran out." TG: "So, when you left, did you want to be known as the former Monkee or did you want to erase that part of your past —" PT: "I tried to erase it." TG: "— and start anew?" PT: "I tried to erase it completely." TG: "How do you do that?" PT: "Well, you just don’t do anything connected with it, just absolutely refuse to have anything to do with it, and… basically what I did was I retreated into — I wound up retreating into Marin County, California, which is just north of San Francisco. And there I worked, I belonged to a worker-owned restaurant, waited tables and was part of the cooperative that owned and operated the restaurant. Nominally owned the restaurant; it was actually owned by this guy whose parents had left him some GM stock, and he bought this thing and the co-op was supposed to pay him to buy him out over the long haul. I think they have done finally, I think it’s now a real workers’ co-op. And I worked there, and I retreated, and nobody said anything to me about my Monkees past except one or two guys said, You know, I’m glad to see you just on the street schlepping around, that kind of thing, which made me feel good. I belonged to a few groups; I belonged to a thing called the Fairfax Street Choir, which had 35 voices in the rock section and was very hard to stage. (laughs) Those little coffee house stages, 35 guys and women. And I also belonged to a kind of second on the bill act in San Francisco called Osceola for a year or so. And that kind of thing. And nobody said anything about The Monkees to me." TG: "Are you in touch with the former members now?" PT: "Occasionally." TG: "I would imagine that some people would be happy to see, like, a reunion. Would you ever imagine that happening? PT: Yeah. The only problem with that is mounting it and making it acceptable to everybody. The problem is, the real problem is that I can’t much see myself going onstage and doing an hour of Monkees greatest hits playing bass and getting offstage. I don’t think that any amount of money would particularly… I don’t suppose that no amount of money, but I don’t think that any amount of money that anybody would be interested in paying me would make me want to do that. I… And I don’t see what conceivable creative project could interest the four of us that would be backed with enough money to make it worth our while to develop any good germ of an idea into something full-blown. I just, I don’t see it happening, I just think that the chances are astronomical against it. It’s possible. We’re all alive. The Beatle reunion is not possible. I’m just reading Lennon’s interview, and he says that thoughts of a Beatle reunion are like going back to high school. Why don’t you go back to high school? When are The Beatles getting back together? When are you going back to high school?" TG: "Is that how you feel?" PT: "I — like I said, I would think that any just simple remounting of The Monkees greatest hits songs on a stage would be that, yes." TG: "Oh, but if you were able to do other material." PT: "That’s what I’m saying. If I thought that it could be creative and useful and engage everybody to the fullest of their capacities, I would, I would consider it. But who’s gonna, you know, pay for us to have hotels, to keep us supported in the styles to which we are accustomed for the two months or three months that it would take to create, carve, mount, produce and rehearse a show that would involve all of us to the maximum of our new capacities. I don’t think it can be done." TG: "How do you feel about audiences?" PT: "What do you mean, (laughs) how do I feel about audiences? What kind of a question is that?" TG: "Okay, because fans have kind of played it both ways with the members of The Monkees, you know, I think when the TV series was on and when millions were being sold, there were millions of fans who were really adoring. And then when you leave a group like that and everybody wants to hear from you only in that context, it’s probably —" PT: "How long have we been on that topic, on this? We’ve been a half an hour, we’ve been almost the entire show on that topic." TG: "What topic?" PT: "The Monkees." TG: "Right. So…" PT: "(gently) So what’s your question?" TG: "So do you have a mixed feeling about fans and audiences?" PT: "Well, fans and audiences are different. Audiences come and they catch the show and they like what I do or they don’t, and that’s up to them, and that’s just the way it’s supposed to be, no matter whether I ever was a Monkee or not. And fans… if a fan, if somebody really needs to remember The Monkees and identify with that, I have nothing to say about that because I don’t know what’s going on with them or what chord I may have touched at some point way back when that they still need to strum on themselves. And it’s none of my business." TG: "So where are you living now?" PT: "I live in Venice, California, legally and technically. As a business matter, I spend most of my time in New York. I still am a registered voter in southern California, my driver’s license is southern California, I’m married, I have children in southern California, I go back there as often as I can and be part of the family, I just don’t get out there very often, and as a business matter, I spend most of my time in New York. Eighty percent." TG: "Where have you been doing most of your performing?" PT: "The New York area these days, mostly. I went to southern Canada, southern Ontario to do a few shows, I’ve been to Boston, I’ve been upstate New York, and I did Pittsburgh a couple, about a year ago, I guess. You know, I operate out of New York basically because you can’t operate out of L.A. You cannot make a living as an entertainer operating out of L.A. Not that I make such a great living operating as an entertainer out of New York, but at least there’s a sense of whatever level I’m on, I can go to the next level and operate on that level for a while. In L.A., you either have to make it or you die. That’s it: you’re either making it or you’re dead. And once somebody has been to the top and come away, you don’t, as far as I see, get much of a second chance in L.A. I tried to knock around as a character, comic character actor for a while, and I got people to: 'Hi, you know, it’s good to see ya,' and they laughed at my jokes, and then they never invited me back." TG: "Um, I forgot what I was gonna ask you." PT: "(laughs) A hell of a note for a professional interviewer." TG: "(laughs) Oh! Do you watch TV much now?" PT: "A fair amount." TG: "Do you watch it very critically, having been — and also seeing what kind of roles are available, I imagine…" PT: "No, no, I don’t watch mass media pop TV much. Hillstreet Blues, that’s about it. The rest of what I watch is CNN, cable news, I don’t know if you get it here." TG: "We don’t get cable here yet." PT: "You don’t have cable in Philly? (jokingly) Oh, you poor people! MTV, also on cable, and, um, the odd cosmos show. I, I saw Carl Sagan say astrology had been completely debunked on a scientific basis. And I go, wait a minute. Not that I’m such a fan of astrology, but there’s no scientific proof that — it’s like, anything you don’t like, if you define it the way you don’t like it, you can prove it doesn’t exist. Like, he said, 'The premise is that the stars have a profound influence on life.’ No, that’s not it." TG: "Do you watch a lot of rock video?" PT: "I watch a fair amount of rock video, and a few pop, the news, you know. Then I listen to music and I read, and I perform and I rehearse, and I run around and take care of business, and that keeps my days filled." TG: "Will you be performing tonight at Godfrey Daniels?" PT: "I’ll be performing at Godfrey Daniels in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania." TG: "And which instruments will you be playing?" PT: "I’ll be playing the guitar, the banjo, and the piano. All at once. (laughter) No, no, seriously, folks, all kidding towards one side, I’ll be playing those three instruments, if they have a decent piano in Bethlehem; I didn’t bring my piano with me." TG: "I want to thank you a lot for talking with us. Thanks very much for being here." PT: "Well, I’m — it was all right, thank you, and I, I just, I just hope it turns out an audience in Bethlehem, that’s all." TG: "Thanks for coming." PT: "Okay." [audio cuts off]

I uploaded the full audio to Google Drive, here.

#Peter Tork#80s Tork#60s Tork#70s Tork#Fairfax Street Choir#Osceola#The Monkees#Monkees#thislovintime transcripts#Peter and Micky#Peter and Davy#Peter and Michael#Don Kirshner#Bob Rafelson#Stephen Stills#et al.#(if anyone is interested in other transcripts feel free to let me know for future posts)#long read#NPR Fresh Air (1983)#Tork interviews#can you queue it

41 notes

·

View notes

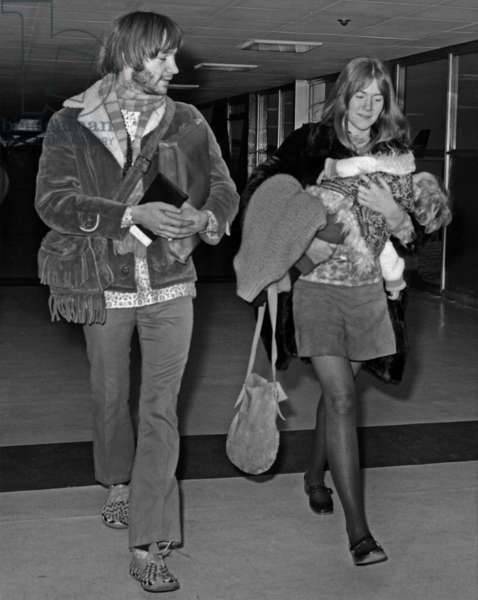

Photo

Karen Harvey on The Monkees' tour plane, summer of 1967 (photo by Henry Diltz); Peter Tork, Karen, and Justin in January 1968 (photo courtesy of Bridgeman Images); Peter and Karen's son Domin, 1989 ("Tork recently visited Harvey and her son in Amsterdam," per The News Journal in 1989; Peter and Karen in the 2000s.

"Harvey was living in the same apartment building as Tork, at 35 Bedford St., and they cemented a friendship that had started earlier. 'We’re still very, very good friends,' she said. Through a girlfriend at one of the art galleries, Harvey also go to know David Crosby. He and Tork were responsible for getting Harvey to move West. 'He [Crosby] fell in love with my girlfriend and took her back to California. Then Peter got this Monkees thing and moved there. Everybody was trying to get me to come to California, and so I eventually went,' Harvey says. 'She came because I asked her to,' Tork confirmed during a phone call from California. 'I can’t actually say she was my girlfriend. She was my roommate. She came back and forth for a while. I’m an old fan of hers from way, way back. Karen is a wonderful singer.' Although she eventually got her own apartment, Harvey spent much of her time at Tork’s house, under the famous 'Hollywood' sign. 'I was handling a lot of affairs of the house because he [Tork] was working like a slave,' Harvey said. 'TV work is no picnic.' With the increasing amount of money and fame through the Monkees’ TV show, Tork moved to a bigger house (once owned by actor Wally Cox) in Studio City. They also needed more room because Tork, Harvey and Robert Hammer, who directed the horror film 'Don’t Answer the Phone,' had formed a film company called Breakthrough-Influence, whose work included videos for Crosby, Stills and Nash, and Steve Miller. (Hammer is also the father of Harvey’s son, Justin, 22; she has another son, Domin, 11, by a member of Sail-Joia.) 'It was in that [Studio City] house that Lowell George from Little Feat used to rehearse, and that was the house that the Beatles came to,' Harvey said. 'Jimi Hendrix came to both [houses] because he was a real good friend right up until he died.' Of the Beatles, only Ringo Starr and George Harrison dropped by the Studio City home, Tork recalled. 'We went swimming for a while in the pool.' 'I slept through it,' said Harvey of the visit. 'I though they would hang around a little and I was just real slow about it and they left. I was hanging out with every superstar in the book, and they were just average people to me. Peter Tork was very, very generous, and his house was an open house.' To make up for her missing the Beatles, Harvey said, Tork suggested they go to England to visit them. It was New Year’s Eve 1968 [sic]. She remembers that her son, Justin, who was a toddler then, played bongos with Harrison at Apple Records. 'We went to visit George,' Tork said. 'George was doing cuts for the "Wonderwall" album [read more about Peter's banjo contribution to the movie here] at the time. I remember George offering to turn the lights up so Karen could have more light to take pictures.'" - The News Journal, July 16, 1989

* * *

“I don’t know that it [fame] affected my ability to have friendships. Basically I don’t think I knew how to be or have a friend beforehand, and I don’t think I learned while I was in that operation [The Monkees]. I mean, I had some good buddies, you know, but that wasn’t the same thing, I didn’t really understand. There was only one person in my life that I could turn to when I was hurting who happened somehow to know what it was, what it took to stop me hurting, and that was a woman named Karen Harvey, who later joined me on the West Coast. And I thought, well, here’s a friend come to join me and this will be a real friend. And we were pretty good friends, I guess, but there wasn’t any that, you know, that — I didn’t know what a friend did in a sense of how, on a day-to-day basis, do you maintain your friendships, do you go out of your way to make sure that things are nice and right and, you know, the kind of work that a friendship takes. You don’t just have a friendship without work. And I didn’t know that. And I’m not so sure I know it now.” - Peter Tork, NPR, June 3, 1983

“[‘Lady’s Baby’] was about the lady that I was living with at the time, and her son. That’s them [in photo 2], that’s my darling Karen, with whom I am still very good friends all these years later.” - Peter Tork during his My Life In The Monkees & So Much More tour, 2013 (x)

#Peter Tork#Karen Harvey#Justin Hammer#Tork quotes#60s Tork#Tork songs#Lady's Baby#80s Tork#1968#1989#<3#long read#'Peter was very very generous'#(transcribing and listening to that 1983 interview makes me want to reach back in time and give Peter a hug)#more transcripts coming soon; been working on transcribing a lot of interviews these last weeks#Tork houses#The News Journal#NPR Fresh Air (1983)#can you queue it

51 notes

·

View notes

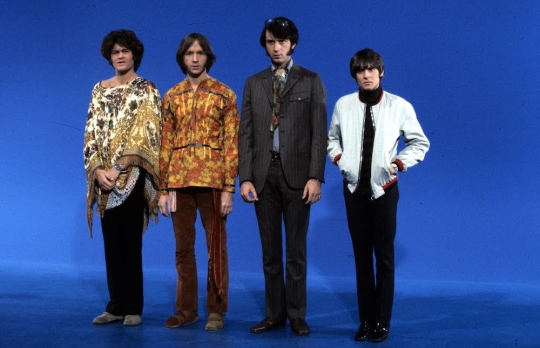

Photo

Peter Tork, 1965, 1967, and 2004 (photos 3 & 4 by Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images).

“[T]hen I said [to Bob Rafelson], ‘Listen, I know another guy that’s a lot like me and he’s probably a little brighter, and he might be a little bit quicker and funnier.’ […] I called him [Peter] up. He said, ‘I’ll come down.’ And two days later, I found out that he had gotten the job and he called me to thank me. It was funny. I was amused that he took it because he was kind of a hipster.” - Stephen Stills on recommending Peter Tork for The Monkees, 1988 interview quoted in Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and Music of Laurel Canyon (2009)

“Steve knows this guy, and it turns out to be Bob Rafelson, one of the producers, who says to him, in his own inimitable way, ‘Well, we like ya a lot, but your hair and teeth are wrong for our production, they ain’t photogenic. You know anybody who looks like you who’s got good hair and teeth?’ Stephen said, ‘My friend Peter.’ And so Stephen called me and said, ‘Go try out for this thing.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure, Steve, yeah, right, instant success, gimme a break.’ And he said, ‘No, no, really, try out.’ ‘All right, all right, all right.’ So, you know, I took my hard-earned savings, which I’d been making washing dishes at this club in southern, way southern California, fifty miles south of Hollywood, and took a bus up to Hollywood and back down again, and up and down for auditions. And eventually won the part.” - Peter Tork, NPR, June 1983 (x)

“There was one guy, Steve, whom I liked enormously. Unfortunately he wasn’t quite right, but he had musical intelligence and I went so far as to ring him up and ask him along again. When he realized he wasn’t going to make it he suggested I get in touch with someone he knew, a certain Peter Thorkelson. I might have said ‘Yeah’ and forgotten about it — particularly as this Peter Thorkelson hadn’t even answered the ad and we had a lot of guys who had. Yet I remember I went to great lengths to contact him. I found him working as a dishwasher — not even as a musician, so you can imagine it took a while tracing him. But when I heard him, I knew at once he was right. I was knocked out.” - Bob Rafelson, NME, August 12, 1967 (x)

Q: “Do you have any regrets about the Monkees?” Peter Tork: “Oh, dozens of little ones, sure. But in a way, nothing that I had any handle on. There were stands I wish I had been able to take sometimes, but you can’t do what you can’t do. If I had been the person who could’ve taken the stands, maybe they wouldn’t have chosen me. You never know how this goes.” Q: “But you’re happy they chose you?” PT: “Oh sure. You know, I’m not going to tell you the story but I promise you that there were a number of events leading up to it that lead me to think that there was a certain kind of ordained quality to it all. I’m not a mystic, by any chance, but I’ve seen a lot of connections occur that standard, conventional Western logic isn’t large enough to take in. And I believe that this was pretty much set up somehow. It’s almost as if I had no choice. Things sort of occurred. For instance, Stephen Stills called me and said, ‘Go try out.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah,’ and hung up and left and didn’t think about it. Well, he called again. Nobody’s ever called me with a suggestion like that twice. Not before, not since.” - The News and Observer, September 13, 2004

#Peter Tork#00s Tork#<3#60s Tork#80s Tork#long read#Stephen Stills#The Monkees#Monkees#Bob Rafelson#1960s#1980s#2000s#1965#1967#2004#NME#Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and Music of Laurel Canyon#NPR Fresh Air (1983)#The News and Observer#can you queue it

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Peter Tork on criticizing the Vietnam War in 1966, from his interview with NPR in June 1983; now up on this fan page's YouTube channel. (In connection with this post.)

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fairfax Street Choir (including Peter Tork), 1970s; photo provided by the Fairfax Street Choir to The Sacramento Bee in 2013.

As with 1970 and 1971 (e.g. here and here), researching turned up a few gig ads, this time from 1973:

“Sleeping Lady: Peter Tork, May 10; Fairfax Street Choir, May 11” - San Francisco Bay Guardian, May 10 through May 23, 1973

“Sleeping Lady: Peter Tork and Wood Nymphs, June 30” - San Francisco Bay Guardian, June 21 through July 4, 1973

“Sunday, [July] 29 Fairfax Street Choir, Peter Tork interlocutes, dancing ladies tap dance and 30 people play and sing some of the sweetest music around, Lions Share, 60 Redhill, San Anselmo” - San Francisco Bay Guardian, July 19 through August 1, 1973