#Modern Monet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Arcadian Echoes

Dr. Caelum Vespera, Curator of Interstellar Artifacts at the National Museum of Future Heritage in the Republic of Solaris, discusses the impressionist painting of Rob Medley, entitled ‘Arcadian Echoes,’ painted at the Ashville Ohio Viking Festival in the first half of the 21st Century. Arcadian Echoes This splendid composition is a remarkable tribute to the Impressionist movement, echoing the…

View On WordPress

#Arcadian#Art of Solitude#Cosmic Narratives#Ethereal Art#Future Heritage#Harmony in Art#Impressionist Legacy#Modern Monet#Timeless Masterpiece#Universe in Color

0 notes

Text

Claude Monet (French, 1840 - 1926) • The Luncheon • 1868 – 1869 • Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany

#art#painting#fine art#art history#oil painting#claude monet#monet#modern art#impressionism#french artist#19th century european art#european art#paintings of domestic interiors#interior with figures#paintings of rooms#the painted room art blog

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

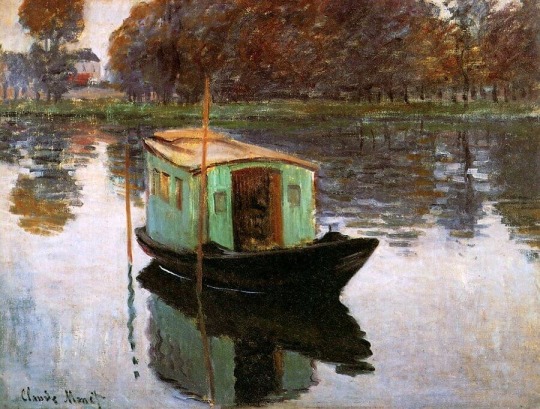

Claude Monet, The Studio Boat, 1874

(Monet’s floating “studio” in Argenteuil)

#claude monet#Argenteuil#impressionism#impressionist art#impressionists#french impressionism#art history#modern art#french artists#French painters#french art#aesthetic#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#aesthetictumblr#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think modern au Buggy would be a fake conspiracy theorist just for the online views and attention and then eventually accidentally make a literal cult? Because God I do and it's hilarious...

#he makes a crap ton of conspiracy theory videos that with his persuading tone of voice is easily believed by his viewers#then SOMEHOW he creates a cult like hes not even sure how it happened either#a simple circus clown with a tiktok account one day#the next a cult leader who doesnt even understand how to be a cult leader so hes actually a relatively harmless one#aaaaaaaaand then mihawk and crocodile take advantage of this opening and does intentional#take part in the whole cult thing oops#they probably just monetized it lmao a whole ass pyramid scheme#one piece#one piece modern au#buggy the clown

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

from the series “Mornings on the Seine”, by Claude Monet

#claude monet#art#impressionistpainting#impressionism#sunday morning#mornings on the seine#france#french art#painting#classical studies#modernism#19th century#20th century#monet#camille pissarro#manet#Renoir#nature#observational art#water lily#landscape#beauty#beautiful sky#sky#clouds#mist#scenery#wallpaper#aesthetic#moodboard

924 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Water-Lily Pond (1899) 🎨 Claude Monet 🏛️ The National Gallery 📍 London, United Kingdom

For Monet, gardens offered a refuge from the modern urban and industrial world, although he and his fellow garden enthusiasts benefited from modern advances in botanical science that were creating new hybrid flowers in a wide choice of shapes and colours that could be produced on an almost industrial scale. He made modest gardens in the homes he rented in Argenteuil and Vetheuil in the 1870s, but from 1883, when he moved to a rented house in Giverny, about 50 miles to the west of Paris, he had more scope to indulge his passion for plants. He became a dedicated gardener with an extensive botanical knowledge, and sought the opinions of leading horticulturalists. As Monet’s career flourished his increasing wealth enabled him to fund what became a grand horticultural enterprise: by the 1890s he was employing as many as eight gardeners.

Monet began by refashioning the garden in front of the house, the so-called ‘Clos Normand’, replacing the existing kitchen garden and orchard with densely planted colourful flower beds that were filled with blooms throughout the seasons. He was able to buy the house in 1890, and three years later he purchased an adjacent plot of land next to the river Epte beyond the railway line at the edge of his property. The plot had a small pond with arrowhead and wild water lilies, which he wanted to turn into a water garden with a larger lily pond ‘both for the pleasure of the eye and for the purpose of having subjects to paint’.

The idea may have occurred to him after he had seen the water garden at the 1899 Exposition Universelle in Paris created by the grower Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac, who bred the first colourful hardy waterlilies. Monet began by requesting permission from the Prefect of the Eure to dig irrigation channels from the Ru – a branch of the Epte – to feed his pond, but the Giverny villagers objected, fearing it would contaminate the water and that the foreign plants would poison their cattle. Monet was furious, but three months later permission came through and he began to enlarge the existing pond, replacing the wild water lilies with Latour-Marliac hybrids available in yellows, pinks, whites and violets.

The pond was enlarged on further occasions – in 1901 and 1904 – tripling the size of the water garden. Together with the flower garden on the other side of the railway track it became the principal preoccupation of the last 26 years of Monet’s life. While the Clos Normand garden was laid out along fairly traditional lines, harking back to the formal French gardens of seventeenth-century Europe, with a central alleyway and geometrically arranged beds, the water garden was more Eastern in inspiration. Its less regimented, more natural design and more muted colours created a quieter, meditative atmosphere. Monet erected a Japanese bridge over the western end of the pond that took its inspiration from the bridges in ukiyo-e Japanese prints. He was a keen collector of these prints and he owned a copy of Hiroshige’s Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine (1856), one of the many prints that features a curved bridge. In a more general sense, the water garden reflected Monet’s admiration for the Japanese appreciation of nature.

Monet had to wait for his water garden to mature before he could begin to paint it in earnest. As he later recalled: ‘It took me some time to understand my water-lilies. It takes more than a day to get under your skin. And then all at once, I had the revelation – how wonderful my pond was – and reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.’ In total, Monet painted 250 canvases of his water garden. Around 200 of these represent water lilies floating on the surface of the water, while the remainder also show the Japanese bridge, the weeping willow trees and wisteria and the irises, agapanthus and day lilies on its banks. In all these pictures Monet was painting a subject that was already ‘pictorial’ – a landscape that had been carefully composed according to his personal aesthetic. The National Gallery has three further paintings of the water garden :Water-lilies, setting sun; Irises; and Water-lilies.

Monet painted three views of the Japanese bridge in 1895, not long after it had been constructed, but then took a break from the subject, only returning to it in 1899. By now the pool was overhung by vegetation and surrounded by plants, but to judge from contemporary photographs it was never as enclosed as Monet painted it, and he exaggerated the feeling of claustrophobia. In December 1900 he exhibited 12 paintings at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in Paris, all of which showed more or less symmetrical views of the Japanese bridge.

In this painting, as in the others in the series, we are looking down onto the surface of the water, where the lily pads float into the distance, meeting the dense foliage on the far bank. Weeping willows are reflected in the pond and clumps of iris border its banks. The perspective seems to shift so that it is hard to find a single focal point; it is as though we are looking up at the bridge but down on the waterlilies. The picture, like the water itself, seems to oscillate between surface and depth. The mainly vertical reflections provide a counterpoint to the horizontal clumps of the lily pads. Different colours, applied with thick brushstrokes, are placed next to each other. This way of painting has more in common with Monet’s early Impressionist works than his more recent paintings of mornings on the Seine, where he had used softer, more blended strokes to convey hazy atmospheric effects.

The Japanese bridge series marked a turning point in Monet’s art. From now on his subjects were painted from an increasingly confined viewpoint, conveying the sense of an enclosed world. In later paintings of the pond, he would dispense with the banks and bridge altogether to focus solely on the water, the reflections and the water lilies. The culmination of Monet’s water lily paintings were the Grandes Dėcorations, 22 enormous canvases each over two metres high and totalling more than 90 metres in length, which he completed months before his death and donated to the French state. These are now on permanent display in two oval rooms in the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

#The Water-Lily Pond#1899#Claude Monet#The National Gallery#London#United Kingdom#oil painting#painting#oil on canvas#Modern art#Impressionism#french#art#artwork#art history

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

“SPRING FLOWERS” CLAUDE MONET // 1864 [oil on fabric | 56 7/8 x 46 1/8”]

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOMA

september 2021

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketches of lasted weeks

#trafalgar law#one piece#fanart#op oc#monet#one piece monet#elbaf#modern au#Rio#my baby Rio i looce heeer#I loove Law as weell want to see him back in the story aaaaah--

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude Monet is my favorite painter! I wish I could see “Woman with a Parasol” in person as it’s my favorite, but this painting here might be my second fav. ☺️ Just saw this one today at the Chicago Art Institute!!!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time someone calls contemporary art “not real art” an angel loses its wings (a creative and unique new artist gives up on their passion and the world becomes slightly less interesting where it could have become slightly more)

#maybe it’s not actually bad#maybe you’re just not creative or smart or interesting or open minded enough to understand it#maybe if you weren’t so narrow minded in your view of what art is/should be you would be able to appreciate the beauty and creativity in it#people have been trying to police what counts as “real” art since the dawn of time#van gogh and monet were once seen as “not real artists”#you are not on the side of history that you think you are#the only art that doesn’t count as real art is ai art#art comes from the soul#it comes from human emotion and creative self expression#everything else is just extra#you don’t need to understand the meaning for it to be meaningful#contemporary art defender#contemporary art#modern art#art#classical art#van gogh#vincent van gogh#claude monet#monet#anti ai art#art movements#renaissance art

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

monet and law in the modern au

#lawmonet#monet one piece#trafalgar law#my art#my comic#secret modern au#undescribed#<- later again#no context yet. anyone knows their ship name?#she wears regular prosthetics but the image of monet running at full speed inside a hospital with the sport ones was too funny

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

autumn visit to nyc 💙 i saw the MoMA and Hadestown, both of which were breathtaking!

#eva’s life#MoMA#museum of modern art#nyc#new york#new york city#autumn#aesthetic#light academia#dark academia#van gogh#monet

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edouard Manet, Monet in his Studio Boat, 1874

Claude Monet, The Studio Boat, 1874

#edouard manet#claude monet#french artist#french art#french painter#french painting#artist studio#boats#small boats#art on tumblr#impressionist#impressionism#impressionist painter#aesthetic#beauty#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle

565 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Weeping Willow, 1921-1922

Oil on canvas

#claude monet#monet#fine art#art#paintings#artwork#artists on tumblr#painting#impressionist painter#impressionism#impressionist art#impressionist#art history#artist#artists#art on tumblr#art of the day#oil on canvas#oil painting#weeping willow#modern art#painter#french artist#giverny#french impressionism

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

STARRY BOUQUET

#van gogh#starry night#vincent van gogh#1889#19th century art#19th century#moma#museum of modern art#oil on canvas#oil painting#Nocturne#paul gauguin#paul cezanne#claude monet#monet#arles#bedroom in arles#Vincent#sunflowers#post impressionism#painting#art history#van gogh museum#amsterdam#dutch artist#tortured artist#modern art#bouquet#flowers#ikebana

39 notes

·

View notes