#Mingus Plays Piano

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Let My Children Hear Music:" Charles Mingus' Masterpiece of Orchestral Jazz

Introduction: Charles Mingus, one of the most innovative and influential composers in jazz history, produced an immense body of work over his career that spanned bebop, hard bop, and avant-garde styles. Yet, of all his creations, “Let My Children Hear Music,” released in 1972, stands out as a monumental testament to his genius. Described by Mingus himself as “the best album I have ever made,”…

#Alan Raph#Bitches Brew#Charles Mingus#Classic Albums#Duke Ellington#George Gershwin#Igor Stravinsky#James Moody#Jazz History#Let My Children Hear Music#Miles Davis#Mingus Ah Um#Mingus Plays Piano#Sy Johnson#Teo Macero#The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady#Tom T. Hall

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Charles Mingus - Myself when I'm real

Del disco MINGUS PLAYS PIANO.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

An extremely dumb guid to “Which famous 60’s/70's Jazz man is that?”

1, Is it Piano lead or Brass lead? If piano go to question two. If brass question three.

2, Does the Pianist sound like he’s taken all the acid, or is there a guy making love to a clarinet?

Oh yeah: he’s taken all the acid alight. Is… is he okay? Thelonious Monk.

Oh yeah, some guy is going ham on a clarinet. Dave Burkbeck Quartet.

Neither of the above: Duke Ellington.

3, If brass lead: is it Louis Armstrong? If Yes, it’s Louis Armstrong. If no, question four.

4, Does the Trumpet player make you feel sad? Even, dare I say, Blue?

Almost? Chet Barker

Kind of? Miles Davies.

If no, question five.

5, Is the trumpet player trying to blow your face clean off? Like, actively trying to kill the first row of the audience? Dizzy Gillespie.

It’s brass led, but Sax not Trumpet.

Okay, technically thats a woodwind but moving on, question 6, isolate the stings: is Charles Mingus doing what he’s actually paid to do in the back of the ensemble, or is he dicking around and seeing how far a man can take a double bass before his band-mates kill him?

Seems to be playing normally: Charlie Parker

He’s fucking around in F minor, and also that Bari sax is filthy! The Mingus Big band, with Ronnie Cuber on the Sax.

#Jazz#Big bang#blues#thelonious monk#dave brubeck#duke ellington#louis armstrong#chet baker#miles davis#dizzy gillespie#charlie parker#charles mingus#Ronnie Cuber#Tell me who i missed and how wrong i am in the comments#God i love Jazz

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

TODAY’S FROZEN MOMENT - 65th Anniversary

This amazing shot was taken just after midnight and in the first moments of the new year, at the Five Spot, a New York jazz club. January 1st, 1959

Here was the legendary Charles Mingus on his bass, playing with Horace Parlan on piano, saxophonists Booker Ervin and John Handy, and Roy Haynes on drums….

In front of Mingus’ bass sits devoted fan Orson Welles…

Photos by Dennis Stock

(Mary Elaine LeBey)

#jazz#Dennis Stock#Charles Mingus#Horace Parlan#Booker Ervin#John Handy#Roy Haynes#Jazz history#Mary Elaine LeBey

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

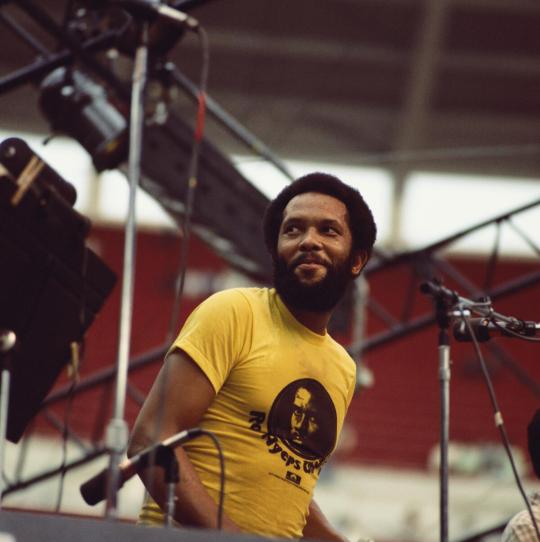

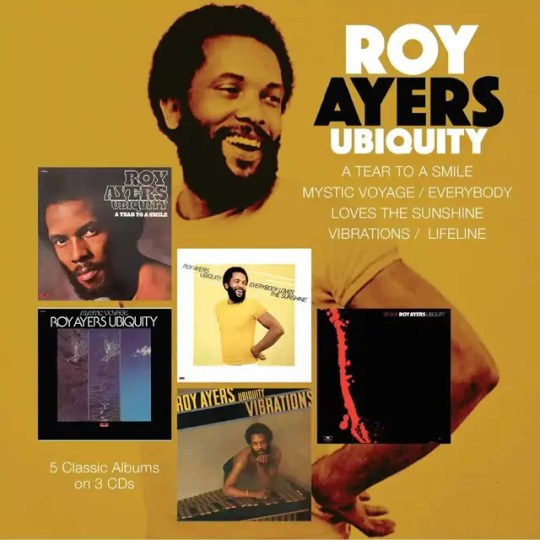

Roy Ayers

Jazz-soul vibraphonist and band leader best known for his laid-back summer track Everybody Loves the Sunshine

When Ruby Ayers, a piano teacher, took her five-year-old son Roy to a concert by the Lionel Hampton Big Band in California in 1945, the boy showed so much enthusiasm for the performance that Hampton presented him with his pair of vibe mallets. Roy Ayers, who has died aged 84, would go on to blaze a trail as a vibraphonist, composer, singer and producer.

A genre-bending pioneer of hard bop, funk, neo-soul and acid jazz, Ayers was most famous for his feel-good track Everybody Loves the Sunshine, from the 1976 album of the same name.

He said that the song was recorded at Electric Lady Studios in New York on, naturally, a warm summer’s day. Among those who feature are Debbie Darby (credited as “Chicas”) on vocals and Philip Woo on piano, electric piano and synthesizer. Woo explained that Ayers did not like to work from charts or scores, with the song based around a single chord that the band in the studio then developed.

While it was never released as a single, Everybody Loves the Sunshine’s warm, jazz-soul sound has won it numerous admirers over the past 50 years. As well as being sampled hundreds of times, by artists including Dr Dre and Mary J Blige, the track has also been covered by musicians ranging from D’Angelo to Jamie Cullen.

Perhaps the sheer simplicity of the song’s structure explains its appeal to such a variety of musicians. The hazy chords set up a steady state condition that allows the performer room for manoeuvre. D’Angelo covered the song in sweaty desire; Cullen’s Live in Ibiza version is as light and moreish as your favourite ice-cream; the Robert Glasper Experiment cover is edgy, an exercise in deconstruction. Other notable versions include the electronica-infused track from the DJ Cam Quartet and the modern jazz take of trumpeter Takuya Kuroda.

Ayers was born in the South Park (later South Central) district of Los Angeles, and grew up on Vermont Avenue amid the widely admired Central Avenue jazz scene during the 1940s and 50s, which attracted luminaries such as Eric Dolphy and Charles Mingus. His father, Roy Ayers Sr, worked as a parking attendant and played the trombone. His mother, Ruby, was a piano player and teacher.

He attended Thomas Jefferson high school, sang in the church choir, and played steel guitar and piano in a local band called the Latin Lyrics. He studied music theory at Los Angeles City College, but left before completing his studies to tour as a vibraphone – or vibes – sideman.

His first album, West Coast Vibes (1963), was produced by the British jazz musician and journalist Leonard Feather. He then teamed up with the flautist Herbie Mann, who produced the “groove” based sound of Virgo Vibes (1967) and Stoned Soul Picnic (1968).

Relocating to New York at the start of the 1970s, Ayers formed the jazz-funk ensemble Roy Ayers Ubiquity, recruiting a roster of around 14 musicians. At this time he composed and performed the soundtrack for the blaxploitation film Coffy (1973), starring Pam Grier as a vigilante nurse. The Everybody Loves the Sunshine album was released under the Ubiquity rubric, reaching No 51 on the US Billboard charts, but making no impact on the UK charts.

His 1978 single Get On Up, Get On Down, however, reached No 41 in the UK. He also scored chart success with Don’t Stop the Feeling (1979), which got to No 32 on the US RnB chart and 56 in the UK. The track was featured on the album No Stranger to Love, whose title track was sampled separately by MF Doom and Jill Scott.

Ayers was a regular performer at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in London during the 80s and his shows there were captured on live albums. Other live recordings include Live at the Montreux Jazz Festival (1972) and Live from West Port Jazz Festival Hamburg (1999). Ayers played at the Glastonbury festival five times, with his last appearance there in 2019.

A tour of Nigeria with Fela Kuti in 1979, and a resulting album, Music of Many Colours (1980), was just one of many fruitful collaborations. Ayers also performed on Whitney Houston’s Love Will Save the Day (1988); with Rick James on Double Trouble (1992); and with Tyler, the Creator on Cherry Bomb (2015).

A soul-funk album, Roy Ayers JID002 (2020), was the brainchild of the producers Adrian Younge and Ali Shaheed Muhammad. The latter was a member of the hip-hop group A Tribe Called Quest, who had sampled Ayers’ Running Away on their track Descriptions of a Fool (1989), and Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s 1974 song Feel Like Makin’ Love on Keep It Rollin’, from their 1993 Midnight Marauders album.

Ayers also collaborated with Erykah Badu on the singer’s second album, Mama’s Gun (2000). The pair recorded a new version of Everybody Loves the Sunshine for what would be Ayers’ final studio album, Mahogany Vibe (2004).

“If I didn’t have music I wouldn’t even want to be here,” Ayers told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s like an escape when there is no escape.”

Ayers married Argerie in 1973. She survives him, as do their children, Mtume and Ayana, a son, Nabil, from a relationship with Louise Braufman, and a granddaughter.

🔔 Roy Edward Ayers Jr, musician and band leader, born 10 September 1940; died 4 March 2025

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1- Charlie, a person with a spirit box head who has ghosts speak for them, is helping Rover, a fella who gets possessed occasionally by a ghost that makes him play piano, with a sudoku puzzle

2- Cyrus, a veterinarian and perhaps maybe occasionally a bit of a stalker, plays violin for Jethro. Jethro is a sucker for music.

3- Jethro, an emo twink who works for Gabby but also happens to be a licensed attorney, is in court with Mingus. Jethro is trying to help Cyrus get his dream head- a cat head- while Mingus has made laws preventing that.

4- Cyrus, now pictured with Cat head (Jethro is a good attorney) cuddles his African gray parrot Ganymede. They both emit a pleased hum.

All of these were briefly doodled in ink and are not perfect lol

Characters made in collaboration with @zestyjestr , Jethro and Charlie are fully his.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

HAMIET BLUIETT, LE PLUS MODERNE DES SAXOPHONISTES BARYTON

“Most people who play the baritone don’t approach it like the awesome instrument that it is. They approach it as if it is something docile, like a servant-type instrument. I don’t approach it that way. I approach it as if it was a lead voice, and not necessarily here to uphold the altos, tenors and sopranos.”

- Hamiet Bluiett

Né le 6 septembre 1940 au nord de East St. Louis à Brooklyn, dans les Illinois, Hamiet Ashford Bluiett Jr. était le fils d’Hamiet Bluiett Sr. et de Deborah Dixon. Aussi connu sous le surnom de Lovejoy, le quartier de East St. Louis était majoritairement peuplé d’Afro-Américains. Fondé pour servir de refuge aux anciens esclaves affranchis dans les années 1830, le village était devenu plus tard la première ville américaine majoritairement peuplée de gens de couleur.

Bluiett avait d’abord appris à jouer du piano à l’âge de quatre ans avec sa tante qui était directrice de chorale. Il était passé à la clarinette cinq ans plus tard en étudiant avec George Hudson, un populaire chef d’orchestre de la région. Même s’il avait aussi joué de la trompette, Bluiett avait surtout été attiré par le saxophone baryton.

Après avoir amorcé sa carrière en jouant de la clarinette dans les danses dans son quartier d’origine de Brooklyn, Bluiett s’était joint à un groupe de la Marine en 1961. Par la suite, Bluiett avait fréquenté la Southern Illinois University à Carbondale, où il avait étudié la clarinette et la flûte. Il avait finalement abandonné ses études pour aller s’installer à St. Louis, au Missouri, au milieu des années 1960.

Bluiett était au milieu de la vingtaine lorsqu’il avait entendu le saxophoniste baryton de l’orchestre de Duke Ellington, Harry Carney, jouer pour la première fois. Dans le cadre de ce concert qui se déroulait à Boston, au Massachusetts, Carney était devenu la principale influence du jeune Bluiett. Grâce à Carney, Bluiett avait rapidement réalisé qu’un saxophoniste baryton pouvait non seulement se produire comme accompagnateur et soutien rythmique, mais également comme soliste à part entière. Expliquant comment il était tombé en amour avec le saxophone barytone, Bluiett avait déclaré plus tard: "I saw one when I was ten, and even though I didn't hear it that day, I knew I wanted to play it. Someone had to explain to me what it was. When I finally got my hands o n one at 19, that was it."

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Après avoir quitté la Marine en 1966, Bluiett s’était installé à St. Louis, au Missouri. À la fin de la décennie, Bluiett avait participé à la fondation du Black Artists' Group (BAG), un collectif impliqué dans diverses activités artistiques à l’intention de la communauté afro-américaine comme le théâtre, les arts visuels, la danse, la poésie, le cinéma et la musique. Établi dans un édifice situé dans la basse-ville de St. Louis, le collectif présentait des concerts et d’autres événements artistiques.

Parmi les autres membres-fondateurs du groupe, on remarquait les saxophonistes Oliver Lake et Julius Hemphill, le batteur Charles "Bobo" Shaw et le trompettiste Lester Bowie. Hemphill avait aussi dirigé le big band du BAG de 1968 à 1969. Décrivant Bluiett comme un professeur et mentor naturel, Lake avait précisé: “His personality and his thoughts and his wit were so strong. As was his creativity. He wanted to take the music forward, and we were there trying to do the same thing.”

À la fin de 1969, Hemphill s’était installé à New York où il s’était joint au quintet de Charles Mingus et au big band de Sam Rivers. Au cours de cette période, Bluiett avait également travaillé avec une grande diversité de groupes, dont ceux des percussionnistes Tito Puente et Babatunde Olatunji, et du trompettiste Howard McGhee. Il avait aussi collaboré avec le Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra.

En 1972, Bluiett avait de nouveau fait équipe avec Mingus et avait fait une tournée en Europe avec son groupe. Collaborateur plutôt irrégulier de Mingus, Bluiett quittait souvent le groupe avant de réintégrer la formation un peu plus tard. En 1974, Bluiett avait de nouveau regagné le giron du groupe de Mingus aux côtés du saxophoniste ténor George Adams et du pianiste Don Pullen, qui deviendrait plus tard un de ses plus fidèles collaborateurs. Il avait aussi joué avec le groupe de Mingus à Carnegie Hall. Bluiett avait continué de travailler avec Mingus jusqu’en 1975, lorsqu’il avait commencé à enregistrer sous son propre nom.

Le premier album de Bluiett comme leader, Endangered Species, avait été publié par les disques India en juin 1976. L’album avait été enregistré avec un groupe composé d’Olu Dara à la trompette, de Junie Booth à la contrebasse et de Philip Wilson à la batterie. En 1978, Bluiett avait enregistré Birthright, un magnifique album live dans lequel il avait joué en solo durant quarante minutes et qui comprenait un hommage à son idole Harry Carney.

En 1976, la même année où il publiait son premier album solo, Bluiett avait co-fondé le World Saxophone Quartet avec d’autres membres du Black Artists Group comme Oliver Lake et Julius Hemphill. Le saxophoniste ténor (et clarinettiste basse) David Murray faisait également partie de la formation. Surnommé à l’origine le Real New York Saxophone Quartet, le groupe avait amorcé ses activités en présentant une série de cliniques et de performances à la Southern University de la Nouvelle-Orléans, avant de se produire au Tin Palace de New York. Menacé d’une poursuite judiciaire par le New York Saxophone Quartet, le groupe avait éventuellement changé de nom pour devenir le World Saxophone Quartet (WSQ).

Le groupe avait enregistré son premier album (d’ailleurs largement improvisé) sous le titre de Point of No Return en 1977. Jouant une musique diversifiée allant du Dixieland au bebop, en passant par le funk, le free jazz et la World Music, le groupe avait remporté un énorme succès (il est aujourd’hui considéré comme une des formations de free jazz les plus populaires de l’histoire) et avait reçu de nombreux éloges de la critique. Qualifiant le groupe de ‘’the most commercially (and, arguably, the most creatively) successful" de tous les ensembles de saxophones formés dans les années 1970, Chris Kelsey écrivait dans le All Music Guide: ‘’At their creative peak, the group melded jazz-based, harmonically adventurous improvisation with sophisticated composition." Commentant un concert du groupe en 1979, Robert Palmer avait déclaré dans le New York Times: “The four men have made a startling conceptual breakthrough. Without ignoring the advances made by musicians like Anthony Braxton and the early Art Ensemble of Chicago, they have gone back to swinging and to the tradition of the big‐band saxophone section.” Palmer avait ajouté: “Some of the music looks to the more archaic end of the tradition, to the hocket‐style organization of wind ensembles in African tribal music, and in doing so it sounds brand new.”

Reconnaissant la contribution de Bluiett dans la création du son d’ensemble du groupe, Kelsey avait précisé: "The WSQ's early free-blowing style eventually transformed into a sophisticated and largely composed melange of bebop, Dixieland, funk, free, and various world musics, its characteristic style anchored and largely defined b y Bluiett's enormous sound." Très conscient de l’importance de la mélodie, Bluiett avait toujours insisté pour que le groupe se concentre principalement sur les balades et l’improvisation. Il expliquait: “I think melody is very important. When we went into the loft situation, I told the guys: ‘Man, we need to play some ballads. You all playing outside, you running people away. I don’t want to run people away.’ ”

Parallèlement à sa collaboration avec le World Saxophone Quartet, Bluiett avait également publié d’autres albums comme leader comme Im/Possible To Keep (août 1977), un enregistrement en concert qui comprenait une version de quarante minutes de la pièce ‘’Oasis - The Well’’ (en trio avec le contrebassiste Fred Hopkins et le percusionniste Don Moye) et une version de trente-sept minutes de la pièce Nali Kola/On A Cloud en quartet avec le pianiste Don Pullen. En novembre 1977, Bluiett avait enchaîné avec Resolution, un album enregistré en quintet avec Pullen, Hopkins et les percussionnistes Don Moye et Billy Hart. À peine un mois plus tard, Bluiett avait récidivé avec Orchestra Duo and Septet, qui mettait à profit différentes combinaisons de musiciens comprenant le violoncelliste Abdul Wadud, le trompettiste Oldu Dara, le pianiste Don Pullen, le joueur de balafon Andy Bey, le flûtiste Ladji Camara, le contrebassiste Reggie Workman, le joueur de oud (un instrument à corde d’origine iranienne) Ahmed Abdul-Malik et le batteur Thabo Michael Carvin.

Avec le temps, les albums de Bluiett publiés en dehors de sa collaboration avec le World Saxophone Quartet étaient devenus de plus en plus accessibles. En faisaient foi des parutions comme Dangerously Suite (avril 1981), qui était une sorte de bilan de la musique populaire afro-américaine, et Ebu (février 1984), enregistré avec John Hicks au piano, Hopkins à la contrebasse et Marvin Smith à la batterie. L’album live Bearer of the Holy Flame (juillet 1983) documentait la collaboration de Bluiett avec un quintet composé de Hicks au piano et de deux percussionnistes. En juillet 1987, Bluiett avait aussi collaboré avec le trompettiste sud-africain Hugh Masekela dans le cadre de l’album Nali Kola qui mettait en vedette un saxophoniste soprano, un guitariste et trois percussionnistes africains

Littéralement passionné par son instrument, Bluiett avait également dirigé plusieurs groupes composés de plusieurs autres saxophonistes baryton. Également clarinettiste, Bluiett avait formé en 1984 le groupe Clarinet Family, un ensemble de huit clarinettistes utilisant des clarinettes de différents formats allant de la clarinette soprano E-flat à la clarinette contrebasse. Le groupe était composé de Don Byron, Buddy Collette, John Purcell, Kidd Jordan, J. D. Parran, Dwight Andrews, Gene Ghee et Bluiett à la clarinette et aux saxophones, de Fred Hopkins à la contrebasse et de Ronnie Burrage à la batterie. Le groupe a enregistré un album en concert intitulé Live in Berlin with the Clarinet Family, en 1984.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Le World Saxophone Quartet avait continué de jouer et d’enregistrer dans les années 1990. Lorsque Julius Hemphill avait quitté le groupe pour former son propre quartet au début de la même décennie, c’est Arthur Blythe qui l’avait remplacé. En 1996, le groupe avait enregistré un premier album pour l’étiquette canadienne Justin Time. Intitulé "Four Now’’, l’album avait marqué un tournant dans l’évolution du groupe, non seulement parce que c’était le premier auquel participait le saxophoniste John Purcell, mais parce qu’il avait été enregistré avec des percussionnistes africains. Comme compositeur, Bluiett avait également continué d’écrire de nombreuses oeuvres du groupe, dont Feed The People on Metamorphosis (avril 1990) et Blues for a Warrior Spirit on Takin' It 2 the Next Level (juin 1996).

Lorsque le World Saxophone Quartet avait commencé à ralentir dans les années 1990 après la fin de son contrat avec les disques Elektra, Bluiett s’était lancé dans de nouvelles expérimentations comme chef d’orchestre. En collaboration avec la compagnie de disques Mapleshade, Bluiett avait fondé le groupe Explorations, une formation combinant à la fois des nouveaux talents et des vétérans dans un style hétéroclite fusionnant le jazz traditionnel et l’avant-garde. Après avoir publié un album en quintet sous le titre If You Have To Ask You Don't Need To Know en février 1991, Bluiett avait publié deux mois plus tard un nouvel album solo intitulé Walkin' & Talkin', qui avait été suivi en octobre 1992 d’un album en quartet intitulé Sankofa Rear Garde.

Depuis les années 1990, Bluiett avait dirigé un quartet appelé la Bluiett Baritone Nation, composé presque exclusivement de saxophonistes baryton, avec un batteur comme seul soutien rythmique. Mais le projet n’avait pas toujours été bien accueilli par la critique. Comme le soulignait John Corbett du magazine Down Beat, "Here's a sax quartet consisting all of one species, and while the baritone is capable of playing several different roles with its wide range, the results get rather wearisome in the end." Le groupe avait publié un seul album, Liberation for the Baritone Saxophone Nation’’ en 1998, une captation d’un concert présenté au Festival international de jazz de Montréal la même année. Outre Bluiett, l’album mettait à contribution les saxophonistes baryton James Carter, Alex Harding et Patience Higgins, ainsi que le batteur Ronnie Burrage. Commentant la performance du groupe, le critique Ed Enright écrivait: "In Montreal, the Hamiet Bluiett Baritone Saxophone Group was a seismic experience... And they blew--oh, how they blew--with hurricane force." Décrivant le concept du groupe après sa performance, Bluiett avait précisé:

‘’This is my concept, and it’s all about the baritone, really. The music has to change for us to really fit. I’m tired of trying to fit in with trumpet music, tenor music, alto music, soprano music. I'm tired of trying to fit in with trumpet music, tenor music, alto music, soprano music. It takes too much energy to play that way; I have to shut the h orn down. Later! We've got to play what this horn will sound like. So, what I’m doing is redesigning the music to fit the horn {...}. It’s like being in the water. The baritone is not a catfish [or any of those] small fish. It’s more like a dolphin or a whale. And it needs to travel in a whole lot of water. We can’t work in no swimming pools.The other horns will get a chance to join us. They’ve just got to change where they’re coming from and genuflect to us—instead of us to them.”

En mars 1995, Bluiett avait publié un album en sextet intitulé New Warrior, Old Warrior. Comme son titre l’indiquait, l’album mettait à contribution des musiciens issus de cinq décennies différentes. Le critique K. Leander Williams avait écrit au sujet de l’album: "The album puts together musicians from ages 20 to 70, and though this makes for satisfying listening in several places, when it doesn't w ork it's because the age ranges also translate into equally broad--and sometimes irreconcilable--stylistic ones.’’ Tout en continuant de transcender les limites de son instrument, Bluiett avait également exprimé le désir d’une plus grande reconnaissance. Il expliquait: "[A]ll the music these days is written for something else. And I'm tired of being subservient to it. I refuse to do it anymore. I refuse to take the disrespect anymore." En juin 1996, Bluiett avait publié Barbecue Band, un album de blues.

Après être retourné dans sa ville natale de Brooklyn, dans les Illinois, pour se rapprocher de sa famille, enseigner et diriger des groupes de jeunes en 2002, Bluiett s’était de nouveau installé à New York dix ans plus tard. Décrivant son travail de professeur, Bluiett avait commenté: “My role is to get them straight to the core of what music is about. Knowing how to play the blues has to be there. And learning how to improvise—to move beyond the notes on the page—is essential, too.”

À la fin de sa carrière, Bluiett avait participé à différentes performances, notamment dans le cadre du New Haven Jazz Festival le 22 août 2009. Au cours de cette période, Bluiett s’était également produit avec des étudiants de la Neighborhood Music School de New Haven, au Connecticut. Le groupe était connu sous le nom de Hamiet Bluiett and the Improvisational Youth Orchestra.

Hamiet Bluiett est mort au St. Louis University Hospital ade St. Louis, au Missouri, le 4 octobre 2018 des suites d’une longue maladie. Il était âgé de soixante-dix-huit ans. Selon sa petite-fille Anaya, la santé de Bluiett s’était grandement détériorée au cours des années précédant sa mort à la suite d’une série d’attaques. Il avait même dû cesser de jouer complètement du saxophone en 2016. Même si le World Saxophone Quartet avait connu de nombreux changements de personnel au cours des années, il avait mis fin à ses activités après que Bluiett soit tombé malade. Les funérailles de Bluiett ont eu le lieu le 12 octobre au Lovejoy Temple Church of God, de Brooklyn, dans les Illinois. Il a été inhumé au Barracks National Cemetery de St. Louis, au Missouri.

Bluiett laissait dans le deuil ses fils, Pierre Butler et Dennis Bland, ses filles Ayana Bluiett et Bridgett Vasquaz, sa soeur Karen Ratliff, ainsi que huit petits-enfants. Bluiett s’est marié à deux reprises. Après la mort de sa première épouse, Bluiett s’était remarié, mais cette union s’était terminée sur un divorce.

Saluant la contribution de Bluiett dans la modernisation du son du saxophone baryton, Garaud MacTaggart écrivait dans le magazine MusicHound Jazz: "Hamiet Bluiett is the most significant baritone sax specialist since Gerry Mulligan and Pepper Adams. His ability to provide a stabilizing rhythm (as he frequently does in the World Saxophone Quartet) or to just flat-out wail in free-form abandon has been appare nt since his involvement with St. Louis' legendary Black Artists Group in the mid-1960s."

Tout en continuant de se concentrer sur le saxophone baryton, Bluiett avait continué de jouer de la clarinette et de la flûte. Avec son groupe Clarinet Family, il avait même contribué à faire sortir de l’ombre des instruments moins bien connus comme les clarinettes contrebasse et contre-alto ainsi que la flûte basse.

Refusant de confiner son instrument à un rôle essentiellement rythmique, Bluiett avait toujours considéré le baryton comme un instrument soliste à part entière. Il expliquait: “Most people who play the baritone don’t approach it like the awesome instrument that it is. They approach it as if it is something docile, like a servant-type instrument. I don’t approach it that way. I approach it as if it was a lead voice, and not necessarily here to uphold the altos, tenors and sopranos.”

Refusant de se laisser dominer par les ordinateurs et les nouvelles technologies, Bluiett avait toujours été un ardent partisan d’un son pur et naturel. Il poursuivait: "I'm dealing with being more healthful, more soulful, more human. Not letting the computer and trick-nology and special effects overcome me. I'm downsizing to maximize the creative part. Working on being more spiritual, so that the music has power... power where the note is still going after I stop playing. The note is still going inside of the people when they walk out of the place." Doté d’une technique impeccable, Bluiett affichait une maîtrise remarquable de son instrument dans tous les registres. Le jeu de Bluiett, qui atteignait un total de cinq octaves, lui permettait de jouer dans des registres qu’on croyait jusqu’alors hors de portée du saxophone baryton.

À l’instar de son collaborateur de longue date, le saxophoniste ténor David Murray, Bluiett était un adepte de la respiration circulaire, ce qui lui permettait de prolonger son phrasé sur de très longues périodes sans avoir à reprendre son souffle. Reconnu pour son jeu agressif et énergique, Bluiett incorporait également beaucoup de bebop et de blues dans le cadre de ses performances. Très estimé par ses pairs, Bluiett avait remporté le sondage des critiques du magazine Down Beat comme meilleur saxophoniste baryton à huit reprises, et ce, sur quatre années consécutives de 1990 à 1993 et de 1996 à 1999. Décrivant la virtuosité et la polyvalence de Bluiett, le critique Ron Wynn écrivait dans le magazine Jazz Times en 2001: ‘’There haven’t been many more aggressive, demonstrative baritone saxophonists in recent jazz history than Hamiet Bluiett. He dominates in the bottom register, playing with a fury and command that becomes even more evident when he moves into the upper register, then returns with ease to the baritone’s lowest reaches.’’

Décrivant Bluiett comme un des saxophonistes les plus dominants de son époque, le critique Stanley Crouch avait déclaré: "He had worked on playing the saxophone until he had an enormous tone that did not just sound loud. And the way that Bluiett described Harry Carney's playing — he basically was telling you how he wanted to play: 'I want to be able to play that very subtle, pretty sound, way at the top of the horn, if necessary. I want to play a foghorn-like low note. And if they want a note to sound like a chain beat on a floor, I can do that, too.'"

Tout aussi à l’aise dans les standards du jazz que dans le blues, Hamiet Bluiett a enregistré près de cinquante albums au cours de sa carrière, que ce soit en solo, en duo, dans le cadre de petites formations ou en big band. Bluiett a collaboré avec de grands noms du jazz et de la musique populaire, dont Babatunde Olatunji, Abdullah Ibrahim, le World Saxophone Quartet, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, James Carter, Bobby Watson, Don Braden, Anthony Braxton, Larry Willis, Charles Mingus, Randy Weston, Gil Evans, Lester Bowie, Don Cherry, Eddie Jefferson et Arthur Blythe. Même s’il croyait que les musiciens devaient faire un effort pour se rapprocher du public, Bluiett était aussi d’avis que le public devait faire ses propres efforts pour comprendre la musique qu’on lui proposait. Il précisait: "Get all the other stuff out of your mind, all of the hang-ups, and just listen. If you like it, cool. If you don't like it, good too. If you hate it, great. If you love it, even better. Now if you leave the concert and don't have no feeling, then something is wrong. That's when we made a mistake."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orbiting Human Circus - Quartet Plus Two - woozy interpretations of standards (and by "woozy" I mean "incorporating singing saws")

Orbiting Human Circus is the continuing evolution of the imagination of Julian Koster (Neutral Milk Hotel, The Music Tapes, Elephant 6), whose music and storytelling under this moniker have encompassed immersive theater and podcasts as well as more traditional EPs and singles. Quartet Plus Two is the group’s debut album. The origins of Quartet Plus Two are as magical and seemingly unlikely as everything else in Koster’s career. While walking through New York’s Central Park, he stumbled upon standup bass player Gauvain Gamon and drummer Kolja Gjoni playing Gershwin and Mingus, and, with the addition of pianist Benji Miller, a musical partnership was born. Koster’s longtime collaborators Robbie Cucchairo (horns) and Thomas Hughes (orchestral arranging and chimes) of The Music Tapes also contribute to the record. The music they make together is at once familiar and unrecognizable; while exploring new musical paths ever forward, there is something as comforting as the smell of autumn leaves or snow. Alongside those composed by Koster, Orbiting Human Circus interpret compositions by Irving Berlin, Duke Jordan, George and Ira Gershwin, and others. The use of the term “composition” is intentional and speaks to Koster’s relationship with the music of Quartet Plus Two in far more evocative terms than “cover” or even “standard.” Much like passionate young pianists will sit down to play Brahms, or children can still be found the world over singing “London Bridge,” or the traditional “Koliada” featured on this album is still sung at holiday time, this music is vital, eternal, and right now—and through the medium of the hearts and souls of Koster and Orbiting Human Circus, the spark that animates these songs has never glowed more warmly. Starring North and Romika, the singing saws Julian Koster: saw encouraging, vocal, orchestral banjo, organ Gauvain Gamon: bass Benjamin Miller: piano Kolja Gjoni: drums And The Music Tapes Robbie Cucchiaro: trumpet, euphonium Thomas Hughes: orchestra chimes, orchestration And The Singing Saw Choir on track 9 And The Orbiting Human Circus Orchestral

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A SERENE JAZZ MASTERPIECE TURNS 65

The best-selling and arguably the best-loved jazz album ever, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue still has the power to awe.

MARCH 06, 2024

At a moment when jazz still loomed large in American culture, 1959 was an unusually monumental year. Those 12 months saw the release of four great and genre-altering albums: Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out (with its megahit “Take Five”), Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Sixty-five years on, the genre, though still filled with brilliant talent, has receded to niche status from the culture at large. What remains of that earthshaking year in jazz? “Take Five” has stayed a standard, a tune you might hear on TV or on the radio, a signifier of smooth and nostalgic cool. Mingus, the genius troublemaker, and Coleman, the free-jazz pioneer, remain revered by Those Who Know; their names are still familiar, but most of the music they made has been forgotten by the broader public. Yet Kind of Blue, arguably the best-selling and best-loved jazz album ever, endures—a record that still has the power to awe, that seems to exist outside of time. In a world of ceaseless tumult, its matchless serenity is more powerful than ever.

On the afternoon of Monday, March 2, 1959, seven musicians walked into Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio, a cavernous former church just off Third Avenue, to begin recording an album. The LP, not yet named, was initially known as Columbia Project B 43079. The session’s leader—its artistic director, the man whose name would appear on the album cover—was Miles Davis. The other players were the members of Davis’s sextet: the saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, the bassist Paul Chambers, the drummer Jimmy Cobb, and the pianist Wynton Kelly. To the confusion and dismay of Kelly, who had taken a cab all the way from Brooklyn because he hated the subway, another piano player was also there: the band’s recently departed keyboardist, Bill Evans.

Every man in the studio had recorded many times before; nobody was expecting this time to be anything special. “Professionals,” Evans once said, “have to go in at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday and make a record and hope to catch a really good day.” On the face of it, there was nothing remarkable about Project B 43079. For the first track laid down that afternoon, a straight-ahead blues-based number that would later be named “Freddie Freeloader,” Kelly was at the keyboard. He was a joyous, selfless, highly adaptable player, and Davis, a canny leader, figured a blues piece would be a good way for the band to limber up for the more demanding material ahead—material that Evans, despite having quit the previous November due to burnout and a sick father, had a large part in shaping.

A highly trained classical pianist, the New Jersey–born Evans fell in love with jazz as a teenager and, after majoring in music at Southeastern Louisiana University, moved to New York in 1955 with the aim of making it or going home. Like many an apprentice, he booked a lot of dances and weddings, but one night, at the Village Vanguard, where he’d been hired to play between the sets of the world-famous Modern Jazz Quartet, he looked down at the end of the grand piano and saw Davis’s penetrating gaze fixed on him. A few months later, having forgotten all about the encounter, Evans was astonished to receive a phone call from the trumpeter: Could he make a gig in Philadelphia?

He made the gig and, just like that, became the only white musician in what was then the top small jazz band in America. It was a controversial hire. Evans, who was really white—bespectacled, professorial—incurred instant and widespread resentment among Black musicians and Black audiences. But Davis, though he could never quite stop hazing the pianist (“We don’t want no white opinions!” was one of his favorite zingers), made it clear that when it came to musicians, he was color-blind. And what he wanted from Evans was something very particular.

One piece that Davis became almost obsessed with was Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s 1957 recording of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. The work, inspired by Ravel’s triumphant 1928 tour of the U.S., was clearly influenced by the fast pace and openness of America: It shimmers with sprightly piccolo and bold trumpet sounds, and dances with unexpected notes and chord changes.

Davis wanted to put wide-open space into his music the way Ravel did. He wanted to move away from the familiar chord structures of jazz and use different scales the way Aram Khachaturian, with his love for Asian music, did. And Evans, unlike any other pianist working in jazz, could put these things onto the keyboard. His harmonic intelligence was profound; his touch on the keys was exquisitely sensitive. “I planned that album around the piano playing of Bill Evans,” Davis said.

But Davis wanted even more. Ever restless, he had wearied of playing songs—American Songbook standards and jazz originals alike—that were full of chords, and sought to simplify. He’d recently been bowled over by a Les Ballets Africains performance—by the look and rhythms of the dances, and by the music that accompanied them, especially the kalimba (or “finger piano”). He wanted to get those sounds into his new album, and he also wanted to incorporate a memory from his boyhood: the ghostly voices of Black gospel singers he’d heard in the distance on a nighttime walk back from church to his grandparents’ Arkansas farm.

In the end, Davis felt that he’d failed to get all he’d wanted into Kind of Blue. Over the next three decades, his perpetual artistic antsiness propelled him through evolving styles, into the blend of jazz and rock called fusion, and beyond. What’s more, Coltrane, Adderley, and Evans were bursting to move on and out and lead their own bands. Just 12 days after Kind of Blue’s final session, Coltrane would record his groundbreaking album Giant Steps, a hurdle toward the cosmic distances he would probe in the eight short years remaining to him. Cannonball, as soulful as Trane was boundary-bursting, would bring a new warmth to jazz with hits such as “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” And for the rest of his career, one sadly truncated by his drug use, Evans would pursue the trio format with subtle lyrical passion.

Yet for all the bottled-up dynamism in the studio during Kind of Blue’s two recording sessions, a profound, Zenlike quiet prevailed throughout. The essence of it can be heard in Evans and Chambers’s hushed, enigmatic opening notes on the album’s opening track, “So What,” a tune built on just two chords and containing, in Davis’s towering solo, one of the greatest melodies in all of music.

The majestic tranquility of Kind of Blue marks a kind of fermata in jazz. America’s great indigenous art had evolved from the exuberant transgressions of the 1920s to the danceable rhythms of the swing era to the prickly cubism of bebop. The cool (and warmth) that followed would then accelerate into the ’60s ever freer of melody and harmony before being smacked head-on by rock and roll—a collision it wouldn’t quite survive.

That charmed moment in the spring of 1959 was brief: Of the seven musicians present on that long-ago afternoon, only Miles Davis and Jimmy Cobb would live past their early 50s. Yet 65 years on, the music they all made, as eager as Davis was to put it behind him, stays with us. The album’s powerful and abiding mystique has made it widely beloved among musicians and music lovers of every category: jazz, rock, classical, rap. For those who don’t know it, it awaits you patiently; for those who do, it welcomes you back, again and again.

James Kaplan, a 2012 Guggenheim fellow, is a novelist, journalist, and biographer. His next book will be an examination of the world-changing creative partnership and tangled friendship of John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Mingus – Oh Yeah

by Atlantic Records. It was recorded in 1961, and features Mingus (usually known to play bass) singing on three of the cuts and playing piano throughout. Allmusic awarded the album five stars and reviewer Steve Huey wrote: “Oh Yeah is probably the most offbeat Mingus album ever, and that’s what makes it so vital.” Charles Mingus – piano and vocals Rahsaan Roland Kirk – flute, siren, tenor saxophone, manzello, and stritch Booker Ervin – tenor saxophone Jimmy Knepper – trombone Doug Watkins – bass Dannie Richmond – drums

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kris Davis — Diatom Ribbons Live At The Village Vanguard (Pyroclastic)

Photo by Peter Gannushkin

The bio on Kris Davis’ website borrows a line from the New York Times which described the Canadian pianist as the beacon that told listeners where in New York City one should go on any given night. Diatom Ribbons Live At The Village Vanguard proposes a more expansive understanding of her relationship to jazz, because the ensemble’s music is a zone where Davis’s notions about was worth hearing in the 20th century gets processed and beamed out into the 21st.

The first project’s first, self-titled iteration wasn’t really the work of a band as much as it was the manifestation of a concept. The musicians at its core were Davis on piano, Trevor Dunn on electric bass, Terri Lynne Carrington on drums and Val Jeanty wielding turntables as a source of sampled speech, natural sounds and scratches. They were supplemented by six other musicians playing electric guitar, saxophones, vibes and voice, who enabled Davis to incorporate blues, rock, hip-hop and classical elements into her already-inclusive vision of the jazz continuum. The two-disc Diatom Ribbons was ambitious, but also a bit exhausting to negotiate.

This similarly dimensioned successor comes from a weekend engagement at the Village Vanguard. The latest material, which hinges around a three-part “Bird Suite,” and the ensemble’s lack of augmentation — besides the core group, there are no horns and just one guitarist, Julian Lage — results in a more cohesive statement of Davis’s thesis, which echoes a point that Charles Mingus already made a long, long time ago; you do Charlie Parker no honor by trying to play like him. He is the namesake of the three-part “Bird Suite,” which is the album’s center of gravity. Buttressed by Jeanty’s snatches of speeches by Sun Ra, Stockhausen, and other visionaries, as well as liberally reinterpreted tunes by Wayne Shorter, Ronald Shannon Jackson, and Geri Allen, the music seems to be arguing that today’s jazz musician, like Bird, need to deal with everything that’s happened, and then come up with something personal.

To that end, Davis makes a hash of old, dualistic notions like inside/outside, improvised/composed or jazz + (one other genre) hybrids. Properly prepared, hash is pretty tasty, and that’s the case with this overflowing platter of pristine lyricism, bebop-to-free structural abstractions, shifting rhythmic matrices and multi-signal broadcasts of sound and voice. This is the good stuff, Davis seems to be saying, and a music maker following a jazz trajectory needs to deal with it all. But, while the music of the Diatom Ribbons ensemble is way more creatively inclusive than all those bebop copycats Mingus used to rail against, it’s a highly personal reordering of what is known, not a total paradigm shift into the new. Come to think of it, however, Mingus’ own undeniably magnificent accomplishments were more on the order of what Davis is doing here than Charlie Parker’s transformation of the music of his time.

Bill Meyer

#kris davis#diatom ribbons live at the village vanguard#pyroclastic#bill meyer#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#Bandcamp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The traveling record shop has visited my town for this weekend, so it was good ol’ crate diggin’ time. Went there twice, just in case. As you can see on the second photo, it was a good idea :)

Here are my findings:

1. Echo and The Bunnymen „Crocodiles” I was lacking their debut in my collection, hence was more than happy to fill the gap. They are a bit raw yet here, but already at home with their style.

2. Gerry Mulligan „The age of steam”from ’71 shows him on a funkier side of things. It’s very, very good. Also he is in a good company here (incl.: Bud Shank, Bob Brookmeyer, Harry „Sweets” Edison, Joe Porcaro).

3. Astrud Gilberto/ Walter Wanderley „A certain smile, a certain sadness”. Astrud and Walter were both present at the birth of Bossa so it’s no surprise their pairing brought us fine, jazzy and classy album full of first rate Bossa Nova.

4. „Mingus Quintet meets Cat Anderson”. It’s a ’72 bootleg from Berlin (good quality) Two side-long tracks and mindblowing versality from all the musicians, they swing and fool around, effortlessly flow from dixie to avant (jungle-style muted horns extravaganza included). Brilliant stuff!

5. Nat „King” Cole and his trio „After midnight”, which is one of his most jazz records, when he sings and plays piano, with a really swingin’ backing band.

6. Dr. John, The Night Tripper „Remedies”. It captures The Good Doctor still deep in his New Orlean voodoo phase, which I love.

#vinyl#vinyl records#records#vinyljunkie#dr John#nat king cole#gerry mulligan#echo and the bunnymen#astrud gilberto#jazz#bossa nova#post punk#vooodoo#charles mingus

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Mingus

The black saint and the sinner lady, 1963 · Play album Richard Williams, Rolf Ericson (trumpet), Quentin Jackson (trombone), Don Butterfield (tuba), Jerome Richardson (soprano saxophone, baritone saxophone), Dick Hafer (tenor saxophone, flute), Charlie Mariano (alto Saxophone), Jaki Byard (piano), Jay Berliner (guitar), Charles Mingus (bass, piano) & Dannie Richmond (drums).

Recorded in New York on January 20th, 1963.

* Lp info

1 note

·

View note

Text

…AND AT THE PIANO…

Miki Yamanaka at SMALLS JAZZ CLUB with

SARAH HANAHAN, Matt Dwonszyk, and Samuel Bolduc, 30 JANUARY 2025, 10:30 pm se

FRANK LACY, Mike Lee, Nicoletta Manzini, Brian Simontacchi, Felix Moseholm, and Wen-Ting Wu, 3 FEBRUARY 2025, 7:30 pm

While Miki Yamanaka first caught my eye as part of Roxy Coss’ band relatively early in that first season of streaming, her regular presence with a late night gig bred a contented familiarity to the point that I’m a fan. In spite of a brash pose, she is a real student of the music and a player of fire and invention. To see her again outside of the leader role was the promise of these gigs, albeit with leaders who can be uneven. They were, but I expected SARAH HANAHAN’s quartet would be more cutting edge and more to my liking whereas FRANK LACY would be rather scattered.

Welllll, they were respectively cutting edged and scattered, but the LACY gig was more fun for me and probably Yamanaka, in fact somehow giving her more space. HANAHAN didn’t pin my ears back quite as much as usual. The middle of the set had an actually pretty tune and then a Latin tinged one and she delayed taking her solos to the stratosphere quite as quickly. The Senor Blues opener morphed into Coltrane’s Dear Lord though I found Hanahan more in Cannonball mode. But, it seemed lackluster and Yamanaka wasn’t engaged. It wasn’t a fun bandstand.

LACY’s however was—and he was particularly pleased with Yamanaka who soloed energetically and comped well for the four horns. Lacy has played in the Mingus Big Band and with the likes of Oliver Lake and Henry Threadgill as well as a stint with Art Blakey. So he likes the palette of a larger band and there was shuffling for charts. There were arrangements, not head charts. The players settled in but only Mike Lee on tenor was consistent as a soloist. Lacy himself is playing trumpet though much of his work has been on trombone. In any case, the tunes—two directly from the Art Blakey book as well as Wayne Shorter’s Lady Day where Lee shone—were agreeable and swinging. They moved along crisply despite having to divide up the solo time among so many. Perhaps there was something in the concision but I didn’t feel Yamanaka had to curb herself and I don’t think it’s just the fan in me saying that she was the one who had the most to say. And the structure of the tunes and the arrangements gave things a swagger and swing that Hanahan’s set just didn’t.

0 notes

Text

John Mehegan Famous Jazz Style Piano Folio - With Instruction on How to play Jazz Piano

John Mehegan Famous Jazz Style Piano Folio - With Instruction on How to play Jazz PianoBest Sheet Music download from our Library.Please, subscribe to our Library.John Mehegan The First Mehegan (1955)Other instructional books by John MeheganJohn Mehegan Improvising, Jazz PianoJohn Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 1 Tonal and Rhythmic Principles (Book)John Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 2 Jazz Rythm And The Improvised LineJohn Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 3 Swing And Early Progressive Piano StylesJohn Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 4 - Contemporary piano styles by John MeheganJohn Mehegan The Jazz Pianist Book 2Browse in the Library:

John Mehegan Famous Jazz Style Piano Folio - With Instruction on How to play Jazz Piano

John Mehegan- Famous Jazz Style PianoDownload Contents: Mimi - Easy Living - I Hear Music - My Old Flame - Accent On Youth - I Wanna Be Loved - I Wished On The Moon - If I Should Lose You - It Could Happen To You - You Leave Me Breathless

John Mehegan The First Mehegan (1955)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8CDmwXWFSyI John Mehegan – "The First Mehegan" Label:Savoy Records – MG-15054 Format:Vinyl, LP, Album, 10", Mono Country:US Released:1955 Genre:Jazz Tracklist: A1 Cherokee A2 The Boy Next Door A3 Blue's Too Much A4 Thou Swell B1 Taking A Chance On Love B2 Uncus B3 Sirod B4 Stella By Starlight Credits Bass – Charlie Mingus* (tracks: A1 to A4), Vinnie Burke (tracks: B1 to B4) Directed By – Jack McKinney (tracks: B1 to B4), Ozzie Cadena (tracks: A1 to A4) Drums – Joe Morello (tracks: B1 to B4), Kenny "Klook" Clarke* (tracks: A1 to A4) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder (tracks: A1 to A4) Guitar – Chuck Wayne (tracks: B1 to B4) Liner Notes – Jack McKinney Piano – John Mehegan Notes Red label with silver print.

Other instructional books by John Mehegan

John Mehegan Improvising, Jazz Piano

John Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 1 Tonal and Rhythmic Principles (Book)

John Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 2 Jazz Rythm And The Improvised Line

John Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 3 Swing And Early Progressive Piano Styles

John Mehegan Jazz Improvisation 4 - Contemporary piano styles by John Mehegan

John Mehegan The Jazz Pianist Book 2

Read the full article

#SMLPDF#noten#partitura#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartitinoten楽譜망할음악ноты#spartiti

0 notes

Text

Charlie Parker at the Massey Hall concert in 1953 (listen here). He was accompanied by, from left to right, pianist Bud Powell, Charles Mingus on bass, drummer Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet.

(English / Español / Italiano)

Charlie Parker played at the legendary Massey Hall concert on 15 May 1953 in Toronto, Canada. This concert is known as one of the greatest in jazz history, as it brought together five of the greatest bebop musicians: Charlie Parker (alto sax), Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet), Bud Powell (piano), Charles Mingus (bass) and Max Roach (drums). Although Parker was not credited on the original album due to contractual problems, his participation was crucial and his playing on alto saxophone left an indelible mark on the evening. This concert is considered by many to be "The greatest jazz concert of all time".

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Charlie Parker en el concierto del Massey Hall en 1953 (escucha aquí). Lo acompañaron, de izquierda a derecha, el pianista Bud Powell, Charles Mingus en el bajo, el baterista Max Roach y Dizzy Gillespie en la trompeta.

Charlie Parker tocó en el legendario concierto del Massey Hall el 15 de mayo de 1953 en Toronto, Canadá. Este concierto es conocido como uno de los más grandes en la historia del jazz, ya que reunió a cinco de los más grandes músicos del bebop: Charlie Parker (saxo alto), Dizzy Gillespie (trompeta), Bud Powell (piano), Charles Mingus (bajo) y Max Roach (batería). Aunque Parker no fue acreditado en el álbum original debido a problemas contractuales, su participación fue crucial y su interpretación en el saxo alto dejó una marca indeleble en la noche. Este concierto es considerado por muchos como "El concierto de jazz más grande de todos los tiempos"

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Charlie Parker al concerto alla Massey Hall nel 1953 (ascolta qui). Lo accompagnano, da sinistra a destra, il pianista Bud Powell, Charles Mingus al basso, il batterista Max Roach e Dizzy Gillespie alla tromba.

Charlie Parker suonò al leggendario concerto della Massey Hall il 15 maggio 1953 a Toronto, in Canada. Questo concerto è conosciuto come uno dei più grandi della storia del jazz, in quanto riunì cinque dei più grandi musicisti bebop: Charlie Parker (sax alto), Dizzy Gillespie (tromba), Bud Powell (pianoforte), Charles Mingus (basso) e Max Roach (batteria). Sebbene Parker non sia stato accreditato sull'album originale a causa di problemi contrattuali, la sua partecipazione fu fondamentale e il suo modo di suonare il sassofono contralto lasciò un segno indelebile nella serata. Questo concerto è considerato da molti "il più grande concerto jazz di tutti i tempi".

Source: Pasión por la música

0 notes