#Mingus Ah Um

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Let My Children Hear Music:" Charles Mingus' Masterpiece of Orchestral Jazz

Introduction: Charles Mingus, one of the most innovative and influential composers in jazz history, produced an immense body of work over his career that spanned bebop, hard bop, and avant-garde styles. Yet, of all his creations, “Let My Children Hear Music,” released in 1972, stands out as a monumental testament to his genius. Described by Mingus himself as “the best album I have ever made,”…

#Alan Raph#Bitches Brew#Charles Mingus#Classic Albums#Duke Ellington#George Gershwin#Igor Stravinsky#James Moody#Jazz History#Let My Children Hear Music#Miles Davis#Mingus Ah Um#Mingus Plays Piano#Sy Johnson#Teo Macero#The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady#Tom T. Hall

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

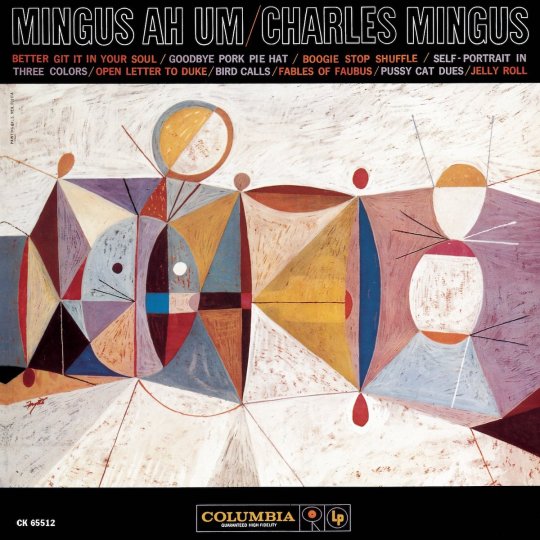

Storia Di Musica #278 - Charles Mingus, Mingus Ah Um, 1959

Le storie di giugno nascono dalla lettura di uno dei libri più belli sulla musica scritto da un non esperto musicale, Natura Morta Con Custodia Di Sax, che Geoff Dyer, sublime scrittore britannico, dedica a storie di jazz. In questo bellissimo saggio, che pesca da fonti storiche, un po’ inventa, un po’ sogna, Dyer scrive storie di alcuni tra i più grandi interpreti di questa musica particolare, creativa, magmatica, pilastro della cultura mondiale da cent’anni. Per mia indiretta colpa, in tutte queste storie di musica non mi era mai capitato di raccontare del personaggio che ho scelto, e uno dei protagonisti del libro, per un mese monografico anche piuttosto particolare: Charles Mingus. Contrabbassista, genio e sregolatezza, uno dei musicisti più importanti del jazz. Arrabbiato, per via di una infanzia passata a cercare di combattere quel sentirsi minoranza di una minoranza (pur essendo di famiglia piccolo borghese, soffriva terribilmente le sue origini meticce, tra genitori con discendenze afroamericane, asiatiche e nativo americane), nato In Arizona nel ’22 ma cresciuto poco prima della Seconda Guerra Mondiale nel tristemente famoso sobborgo di Watts a Los Angeles. Mingus si avvicina da giovanissimo al violoncello, ma poi si appassiona al contrabbasso, che studia con i migliori insegnanti, tra cui Herman Reischagen, primo contrabbasso dell’Orchestra Filarmonica di New York. Nel 1947 entra nell'Orchestra di Lionel Hampton, è già leader di propri gruppi e ha già fatto i primi tentativi di composizione. Mingus si approccia alla musica grazie ai canti gospel delle congregazioni religiose che frequentava regolarmente a Watts e a Los Angeles, realtà con cui venne a contatto durante gli anni dell'infanzia. Ascolta il blues e il jazz ma ha una varietà di conoscenze e di curiosità che compariranno qua e là nel corso della sua leggendaria carriera musicale: si dice ascoltasse Bach ogni giorno, studia Richard Strauss e Arnold Schönberg, non nasconde una passione per Claude Debussy e Maurice Ravel. Suona con il Mito Charlie Parker, ma il suo idolo è la big band di Sir Duke Ellington. E nel 1953 ha l’occasione della vita: viene chiamato da Ellington a suonare con lui. Leggenda vuole che Juan Tizol, portoricano, bianco, trombonista, che in quel momento scrive dei pezzi per l’Orchestra, gli scrive un assolo da suonare con l’archetto. Lui lo traspone di un’ottava per renderlo cantabile, e lo esegue come se lo strumento fosse un violoncello. Tizol lo apostrofa dicendogli che «come tutti i neri della band non sai leggere bene la musica»; Mingus, che è un gigante di mole (tra i suoi demoni, un’ingordigia da romanzo) lo prende a calci nel sedere. Tizol, sempre secondo la leggenda, nella custodia del trombone aveva un coltello, che prontamente afferra per scagliarsi contro Mingus mentre Duke dà l’attacco del brano. Questi, agilmente nonostante la sua mole, con il contrabbasso preso in braccio, salta e scivola sul pianoforte, correndo e dileguandosi fra le quinte. Rientra in un lampo sul palco con in mano una scure da pompiere e sfascia la sedia dell’esterrefatto Tizol. Ellington, che si dice non licenziò mai un suo musicista, lo “spinse” a dimettersi, e nella sua autobiografia (dal titolo già profetico, Beneath The Underdog, tradotta in italiano con il titolo magnifico di Peggio Di Un Bastardo) Mingus racconta: “Duke mi disse <<Se avessi saputo che scatenavi un simile putiferio avrei scritto un’introduzione>>, gli risposi che aveva perfettamente ragione”. Il suo era uno stile libero, che in pratica rimarrà unico. Esempio perfetto è il noto Pithecanthropus Erectus (1956), primo grande disco da solista, che dà un’idea generale della sua musica: bruschi cambi di atmosfera, di tempo e ritmo, un tocco “espressionista” che, di fatto, lo rendono quasi precursore del free jazz, considerazione tra l’altro che lo faceva andare su tutte le furie. Mingus si appassiona alla musica di New Orleans, seguendo l’idea di big band di Ellington, e da questo punto in poi viene fuori tutta la sua incontenibile vitalità, spesso oltremodo eccessiva e davvero fuori le righe: altro caso leggendario fu la “maratona” intrapresa con il fido Dannie Richmond, il suo batterista per quasi tutta la carriera, a chi consumava più amplessi e tequila nei bordelli di Tijuana; da questa esperienza nacque quel capolavoro assoluto che è Tijuana Moods, registrato nel 1957 ma uscito solo nel 1962. Miles Davis disse di lui: “Era sicuramente pazzo, ma è stato uno dei più grandi contrabbassisti che abbia mai sentito. Mingus suonava qualcosa di diverso, era diverso da tutti gli altri, era genio puro”. La prova è il disco di oggi, uno dei capolavori assoluti del jazz, che esce nel 1959, il suo primo per la Columbia. Il titolo Mingus Ah Um è una parodia di una declinazione latina (gli aggettivi latini della I classe sono solitamente ordinati enunciando prima il nominativo maschile singolare che finisce con "us", poi il femminile "a" e infine il neutro "um"). In copertina un dipinto di S. Neil Fujita, che già aveva creato un disegno per un altro disco leggendario, Take Five di Dave Brubeck. Il disco è una sorta di enciclopedia del jazz, sia per la varietà dei brani proposti, sia per il futuro successo di alcuni, diventati standard tra i più famosi di tutti i tempi. Better Git It In Your Soul è un omaggio alla musica ritmica dei gospel e dei sermoni di chiesa, pezzo già leggendario, che fa da apripista al primo immenso capolavoro. Goodbye Porky Pie Hat è un omaggio al Pres, Lester Young, immenso sassofonista, scomparso poche settimana prima che l’album venisse registrato (per la cronaca in due leggendarie sessioni di registrazioni agli studi Columbia, il 5 e il 12 Maggio, sotto le cure mitiche di Teo Macero, il grande produttore di Miles Davis). Il porky pie hat è un cappello che ricorda nella forma il famoso pasticcio di carne inglese, e per dare un’idea di come è quello che indossa sempre Buster Keaton nei suoi film, ma era anche un cappello dal valore simbolico interraziale per i musicisti jazz, e Young lo teneva sempre in testa durante le esibizioni: il brano è divenuto uno standard da migliaia di interpretazioni, uno dei brani più famosi della storia del jazz. Self-Portrait In Three Colors era stata originariamente scritta per il film Ombre, opera prima di John Cassavetes, ma la canzone non appare né nel film né nel disco colonna sonora. Open Letter To Duke è un chiaro omaggio alla figura di Duke Ellington, composto riunendo insieme alcuni pezzi da tre precedenti brani di Mingus (Nouroog, Duke's Choice e Slippers). Jelly Roll è un riferimento al pianista pioniere del jazz Jelly Roll Morton, che si autoproclamò l’inventore del jazz nella prima decade del 1900; Bird Calls passò in un primo momento per un omaggio alla leggenda del bebop Charlie "Bird" Parker, con cui Mingus suonò molte volte, ma fu lo stesso Mingus a chiarire: «Non era stata intesa per suonare come qualcosa di Charlie Parker. Doveva piuttosto assomigliare al cinguettio degli uccelli - almeno la prima parte». Completano il capolavoro Pussy Cat Dues, Boogie Stop Shuffle dal ritmo irresistibile ma soprattutto Fables Of Faubus, primo dei grandi brani politici di Mingus: fu “dedicato” al governatore (democratico!) dell’Arkansas, Orval Eugene Faubus, convinto segregazionista, che nel 1957 tentò di impedire l'ingresso a scuola di nove ragazzi neri in un liceo di Little Rock, in deroga ad una decisione della Corte suprema che aveva reso illegale la segregazione nelle scuole. L'episodio ebbe un punto di svolta quando il presidente Dwight Eisenhower federalizzò la Guarda nazionale dell'Arkansas e permise agli studenti di colore di entrare nell'istituto sotto scorta. Faubus decise allora di chiudere tutte le scuole superiori di Little Rock fino al 1958. Mingus scrisse anche un testo, molto sarcastico, sul Governatore, e si dice che la Columbia lo censurò. In realtà però il testo fu aggiunto dopo da Mingus, quando il brano era stato già registrato, ma non si perse d’animo e lo pubblicò cantato nel suo disco del 1960 Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus, con il titolo di Original Faubus Fables. Il disco è uno dei capisaldi del jazz, uno dei cinquanta dischi selezionati dalla Biblioteca del Congresso degli Stati Uniti per essere inclusi nel National Recording Registry in conservazione per i posteri e la prestigiosa Penguin Guide, la bibbia della critica jazz, lo inserì nella Core Section con il loghino della corona, la massima valutazione per un disco. Con Mingus suonano il fido Richmond alla batteria, John Handy, Booker Ervin e Shafi Hadi ai sax (alto e tenore), Willie Dennis al trombone, Horace Parlan al piano (che suona pure Mingus) e Jimmy Knepper, leggendario trombonista, personaggio da cui si partirà per la seconda tappa di questo mese Mingusiano.

Che vi dico già verrà pubblicata Martedi 13 Giugno.

17 notes

·

View notes

Audio

6:05 PM EDT October 12, 2023:

Charles Mingus - “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” From the album Mingus Ah Um (September 14, 1959)

Last song scrobbled from iTunes at Last.fm

File under: Post-bop

–

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're diving into the iconic world of jazz albums, and we want to hear from YOU! 💬 Whether you’re a seasoned jazz enthusiast or just getting started, these albums are legends in the genre. But we’re curious—which one resonates with you the most? 🤔

Your chance to VOTE and be heard! And if we missed your favorite, let us know in the comments. 🎶

#Jazz#KindofBlue#ALoveSupreme#HerbieHancock#MingusAhUm#BillEvans#JazzLegends#JazzCommunity#MusicPoll#Jazz music#John Coltrane#Head Hunters#Miles Davis#Charles Mingus#Bill Evans#Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz#Jazz Art#Some place it's always Monday...#Best Jazz Album Ever#Sunday at the village vanguard#Music Monday#tumblr tuesday#Music on tumblr

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry for the spam likes today. Favorite jazz album?? I saw a post on your blog that mentioned Mingus ah um. That’s either my fave or Birth of Cool (Miles Davis does do my favorite version of On Green Dolphin Street). Though both are kinda basic choices I want to expand my listening.

so i'm gonna give you a few albums (and album-adjacent things) with the caveat that i haven't heard most of what's out there ^_^ i'm just a casual fan

ornette coleman - the shape of jazz to come

this album is on another level. the multiple layers of brass crisscross each other, playing dissonant chaos, then they rip into solos that could melt charlie parker's fingers. the bass shreds and stumbles up and down some wild assortment of scales. the drums patter out a frantic rhythm that somehow ties everything together.

it shouldn't make sense, but it feels so alive. you'll catch quotes from flight of the bumblebee over rainy oceans of rhythm. herds of wild animals shuffle back and forth in a forest painted by jackson pollock. and then whoever's not soloing yells "woo! alright!"

it's not even my favorite ornette coleman recording. that honor goes to this youtube upload of a live show in germany, 1978. the bass intro, instantly picked up by the drummer, is so electric. the haunting melodies, borrowed from the rite of spring, are traded from sax to guitar. the whole band feels like they're operating on instinct. this is what a basquiat painting SOUNDS like. like a genius artist drawing with their non-dominant hand. LITERALLY coleman plays a violin left-handed at one point. it's incredible.

john coltrane - my favorite things

trane puts so much panache into this simple little pop song. the opening chords are heavy with drama. the groove is insanely tight. every time he plays the melody, it's got a new rhythm, to the point where he seems to be playing a game with the listener. "how many ways can i get you to feel this groove?" the song is melted, bent, and stretched like molten glass, in a 13 minute display of total virtuosity

and that's just track 1!!!! this album is timeless. every second is as fresh and vibrant as it was in 1961

herbie hancock - headhunters

herbie has always been at the cutting edge of jazz fusion. this is his definitive statement on funk

this album is intensely rhythmic, laying out catchy melodies over funk foundations. the whole band seems to just be having a blast. the grooves are often busy and hypermelodic, with no room to breathe as everyone jams at once. it's like an all-night house party in a bouncy castle full of confetti

if you're a fan of japanese jazz like caseopia, or jazz-influenced video game music, this album will feel shockingly familiar to you. its wildly creative synth work, uplifting and colorful chords, and eclectic sound palette are all DECADES ahead of their time.

where would we be without herbie? i'd wager the entire global music landscape would be different. from hip hop to big beat to drum n bass, we all stand on the shoulders of giants. hancock is a titan. the giants that raise us up are standing on his shoulders

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Mingus - Mingus Ah Um, 1959.

Artiste non crédité.

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Mingus - Mingus Ah Um. 1959 : Columbia CL 1370.

! acquire the album ★ attach a coffee !

#jazz#hard bop#bop#jazz bass#charles mingus#1959#columbia#horace parlan#booker ervin#teo macero#1950s#1950s Jazz#essential jazz#essential album

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

Got any jazz recommendations for a beginner?

some records that i think make a great introduction to jazz:

kind of blue by miles davis

moanin' by art blakey and the jazz messengers

mingus ah um by charles mingus

big steps by john coltrane

saxophone colossus by sonny rollins

once you get more used to this style and want something more off beat i strongly recommend the shape of jazz to come by ornette coleman

you can also discover more records and artists by looking at who else the musicians in the records you like played with. like when i listened to saxophone colossus i was really impressed by the drumming and looked for more records with max roach, and i discovered a lot of great music like that

jazz is so fun to explore, there are so many subgenres spanning many different decades, you're almost guaranteed to find something you'll love

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Howard Mandel (Editor): Jazz & Blues Encyclopedia (2019)

I bought this Jazz & Blues Encyclopedia at Nashville's National Museum of African American Music, and it's as entertaining and educational as a visit to this incredible museum, should you find yourself in Music City.

Decade by decade, throughout the 20th Century and into the 21st, this comprehensive survey provides detailed descriptions of the music’s evolution in both technical and artistic terms, while putting everything into clear historical and social context.

And it ain't just jazz and blues in the strictest definition, but every possible branch in their family trees, leading into countless other styles of American music, such as R&B, Soul, Funk, Gospel, Doo Wop, and, of course, Rock 'n' Roll and Hip Hop.

Each decade also gets a dedicated description of relevant events, deep dives into a handful of key artists, and capsule biographies of dozens more, both familiar and obscure (depending upon the reader, of course), along with their most important works.

All the while, this incredible trove of invaluable information is presented with a fair, authoritative, scholarly tone, reminiscent of the very best PBS documentaries -- at once dispassionate and oh-so-passionate -- about these timeless artists and their music.

Needless to say, this encyclopedia is highly recommended to find a shelf in every home -- not least as a handy reference book.

Featured Records:

Bessie Smith: The World’s Greatest Blues Singer (1970)

Various Artists: Jazz Abstractions (1960)

Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra: The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra, Vol. 2 (1966)

Nina Simone: Nina Simone Sings the Blues (1967)

Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah Um (1959)

Miles Davis: Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet (1958)

Billy Cobham: Spectrum (1973)

Buy from: Amazon

#jazz#blues#r&b#soul#miles davis#john coltrane#duke ellington#count basie#billie holiday#bessie smith#charles mingus#robert johnson#nina simone#sun ra#jimi hendrix#ray charles#hip hop#rock#doo wop#janis joplin#thelonious monk#muddy waters#howlin' wolf#charley patton#cab calloway#ella fitzgerald#billy cobham

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A SERENE JAZZ MASTERPIECE TURNS 65

The best-selling and arguably the best-loved jazz album ever, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue still has the power to awe.

MARCH 06, 2024

At a moment when jazz still loomed large in American culture, 1959 was an unusually monumental year. Those 12 months saw the release of four great and genre-altering albums: Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out (with its megahit “Take Five”), Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Sixty-five years on, the genre, though still filled with brilliant talent, has receded to niche status from the culture at large. What remains of that earthshaking year in jazz? “Take Five” has stayed a standard, a tune you might hear on TV or on the radio, a signifier of smooth and nostalgic cool. Mingus, the genius troublemaker, and Coleman, the free-jazz pioneer, remain revered by Those Who Know; their names are still familiar, but most of the music they made has been forgotten by the broader public. Yet Kind of Blue, arguably the best-selling and best-loved jazz album ever, endures—a record that still has the power to awe, that seems to exist outside of time. In a world of ceaseless tumult, its matchless serenity is more powerful than ever.

On the afternoon of Monday, March 2, 1959, seven musicians walked into Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio, a cavernous former church just off Third Avenue, to begin recording an album. The LP, not yet named, was initially known as Columbia Project B 43079. The session’s leader—its artistic director, the man whose name would appear on the album cover—was Miles Davis. The other players were the members of Davis’s sextet: the saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, the bassist Paul Chambers, the drummer Jimmy Cobb, and the pianist Wynton Kelly. To the confusion and dismay of Kelly, who had taken a cab all the way from Brooklyn because he hated the subway, another piano player was also there: the band’s recently departed keyboardist, Bill Evans.

Every man in the studio had recorded many times before; nobody was expecting this time to be anything special. “Professionals,” Evans once said, “have to go in at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday and make a record and hope to catch a really good day.” On the face of it, there was nothing remarkable about Project B 43079. For the first track laid down that afternoon, a straight-ahead blues-based number that would later be named “Freddie Freeloader,” Kelly was at the keyboard. He was a joyous, selfless, highly adaptable player, and Davis, a canny leader, figured a blues piece would be a good way for the band to limber up for the more demanding material ahead—material that Evans, despite having quit the previous November due to burnout and a sick father, had a large part in shaping.

A highly trained classical pianist, the New Jersey–born Evans fell in love with jazz as a teenager and, after majoring in music at Southeastern Louisiana University, moved to New York in 1955 with the aim of making it or going home. Like many an apprentice, he booked a lot of dances and weddings, but one night, at the Village Vanguard, where he’d been hired to play between the sets of the world-famous Modern Jazz Quartet, he looked down at the end of the grand piano and saw Davis’s penetrating gaze fixed on him. A few months later, having forgotten all about the encounter, Evans was astonished to receive a phone call from the trumpeter: Could he make a gig in Philadelphia?

He made the gig and, just like that, became the only white musician in what was then the top small jazz band in America. It was a controversial hire. Evans, who was really white—bespectacled, professorial—incurred instant and widespread resentment among Black musicians and Black audiences. But Davis, though he could never quite stop hazing the pianist (“We don’t want no white opinions!” was one of his favorite zingers), made it clear that when it came to musicians, he was color-blind. And what he wanted from Evans was something very particular.

One piece that Davis became almost obsessed with was Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s 1957 recording of Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. The work, inspired by Ravel’s triumphant 1928 tour of the U.S., was clearly influenced by the fast pace and openness of America: It shimmers with sprightly piccolo and bold trumpet sounds, and dances with unexpected notes and chord changes.

Davis wanted to put wide-open space into his music the way Ravel did. He wanted to move away from the familiar chord structures of jazz and use different scales the way Aram Khachaturian, with his love for Asian music, did. And Evans, unlike any other pianist working in jazz, could put these things onto the keyboard. His harmonic intelligence was profound; his touch on the keys was exquisitely sensitive. “I planned that album around the piano playing of Bill Evans,” Davis said.

But Davis wanted even more. Ever restless, he had wearied of playing songs—American Songbook standards and jazz originals alike—that were full of chords, and sought to simplify. He’d recently been bowled over by a Les Ballets Africains performance—by the look and rhythms of the dances, and by the music that accompanied them, especially the kalimba (or “finger piano”). He wanted to get those sounds into his new album, and he also wanted to incorporate a memory from his boyhood: the ghostly voices of Black gospel singers he’d heard in the distance on a nighttime walk back from church to his grandparents’ Arkansas farm.

In the end, Davis felt that he’d failed to get all he’d wanted into Kind of Blue. Over the next three decades, his perpetual artistic antsiness propelled him through evolving styles, into the blend of jazz and rock called fusion, and beyond. What’s more, Coltrane, Adderley, and Evans were bursting to move on and out and lead their own bands. Just 12 days after Kind of Blue’s final session, Coltrane would record his groundbreaking album Giant Steps, a hurdle toward the cosmic distances he would probe in the eight short years remaining to him. Cannonball, as soulful as Trane was boundary-bursting, would bring a new warmth to jazz with hits such as “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” And for the rest of his career, one sadly truncated by his drug use, Evans would pursue the trio format with subtle lyrical passion.

Yet for all the bottled-up dynamism in the studio during Kind of Blue’s two recording sessions, a profound, Zenlike quiet prevailed throughout. The essence of it can be heard in Evans and Chambers’s hushed, enigmatic opening notes on the album’s opening track, “So What,” a tune built on just two chords and containing, in Davis’s towering solo, one of the greatest melodies in all of music.

The majestic tranquility of Kind of Blue marks a kind of fermata in jazz. America’s great indigenous art had evolved from the exuberant transgressions of the 1920s to the danceable rhythms of the swing era to the prickly cubism of bebop. The cool (and warmth) that followed would then accelerate into the ’60s ever freer of melody and harmony before being smacked head-on by rock and roll—a collision it wouldn’t quite survive.

That charmed moment in the spring of 1959 was brief: Of the seven musicians present on that long-ago afternoon, only Miles Davis and Jimmy Cobb would live past their early 50s. Yet 65 years on, the music they all made, as eager as Davis was to put it behind him, stays with us. The album’s powerful and abiding mystique has made it widely beloved among musicians and music lovers of every category: jazz, rock, classical, rap. For those who don’t know it, it awaits you patiently; for those who do, it welcomes you back, again and again.

James Kaplan, a 2012 Guggenheim fellow, is a novelist, journalist, and biographer. His next book will be an examination of the world-changing creative partnership and tangled friendship of John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

pitchfork has really rare moments of pure insight. I’m pretty sure this was a pitchfork article , but it was about Illmatic. How did Illmatic become *the* rap classic? Obviously it’s incredible, but there’s a few others as good. Why that one?

and the article’s thesis was that Illmatic was chosen because it *wasn’t* representative but could be presented as such in a way appealing to the academy. Nas is clever on that album, but he’s never funny—-no real jokes. There’s no club track. These are the two aspects of early 90’s rap that people still make fun of, and they were a great part of it! Illmatic sidesteps all that stuff; you can just meditate on the (really, truly) brilliance of ‘Sleep is the cousin of death’ etc

the standard ‘how do I get into jazz’ recommendation list is kind of like this. It always goes—-Kind of Blue, Miles, A Love Supreme, Coltrane (both amazing)—-and a third that’s shifting by taste but is meant to make up the slack (colorful, uptempo, fun)—-normally Brubeck’s Take Five or Mingus Ah Um (again, all great albums). My boss back in Chi talked to me about this once and said ‘you notice something? …you know anyone who dances to those?’

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Booker Ervin: The Tenor Saxophonist Who Brought the Blues to Jazz

Introduction: Booker Ervin’s tenor saxophone voice was one of the most distinctive in jazz. He combined the raw emotional intensity of the blues with the sophistication of modern jazz, creating a style that was both deeply rooted in African American musical traditions and forward-thinking in its complexity. Though he was overshadowed by contemporaries like John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins,…

#Alan Dawson#Blues & Roots#Booker Ervin#Buddy Tate#Charles Mingus#Charlie Parker#Dexter Gordon#Jaki Byard#Jazz History#Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland#Jazz Saxophonists#John Coltrane#Lester Young#Mingus Ah Um#Richard Davis#Sonny Rollins#The Blues Book#The Freedom Book#The Song Book#The Space Book

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

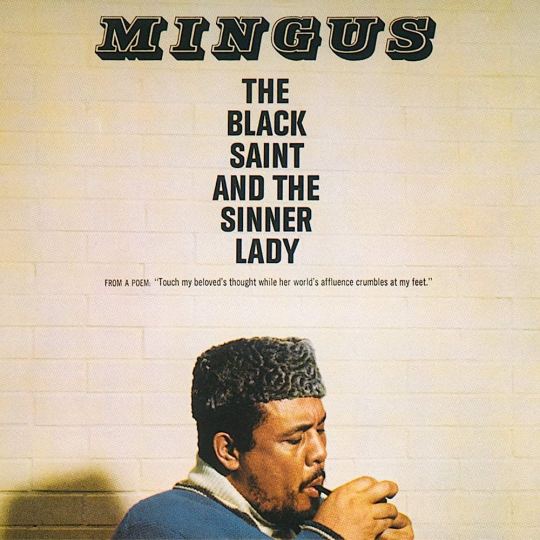

Storia di Musica #279 - Charles Mingus, The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady, 1963

Jimmy Knepper è stato uno dei più grandi trombonisti del jazz. Dopo una straordinaria “gavetta” nei locali più famosi di tutti gli stati uniti negli anni ‘40, suonando nelle più prestigiose orchestre, a metà anni ‘50 ha l’incontro della sua vita, quello con Charles Mingus. Mingus lo scrittura per moltissimi lavori ma, come si è già detto nella storia precedente, Mingus aveva un rapporto quantomeno singolare con i suoi collaboratori: non rare erano le urla durante i concerti perchè non suonavano come voleva lui, le liti, le mani addosso. Ma con Knepper successe qualcosa di inaudito. Inizio anni ‘60, dopo il grande successo di Mingus Ah Um, il grande contrabbassista suona prima con il suo mito Duke Ellington in Money Jungles (1960, immenso capolavoro anche con la collaborazione di Max Roach) e poi inizia una proficua collaborazione con Eric Dolphy, con cui c’era anche una sorta di amicizia spirituale, non nuova nelle relazioni di Mingus ma sempre piuttosto movimentate: faranno insieme un leggendario tour europeo, poi si divisero perchè Dolphy rimarrà nel Vecchio Continente, dove morirà in circostanze mai del tutto chiarite nel 1964 a Berlino, ad appena 36 anni. Knepper lo segue ovunque, e sta preparando con lui i brani per un concerto presso la Town Hall di New York. Parlando del lavoro da fare, Mingus chiese a Knepper di suonare diversamente un assolo, ma al rifiuto di Jimmy, successe l’incredibile: si scaraventò sul trombonista, e con un pugno lo colpì sul viso, rompendogli un dente e rovinandogli l'imboccatura, che per un trombettista significava smettere di suonare come una volta (ci vorranno anni per il ritorno di Knepper al trombone, nonostante ciò dovette cambiare stile e perse per un certo periodo la totale estensione del suo strumento). Knepper non fece finta di niente e lo trascinò in tribunale. Lì successe una cosa che spiega benissimo il carattere del nostro Charles: nonostante il suo avvocato lo supplicasse di stare in silenzio, Mingus sbuffava ogni volta che il Giudice lo definiva musicista jazz, alche Mingus chiede al giudice: “Non mi chiami musicista jazz. Per me la parola jazz significa negro, discriminazione, cittadinanza di serie B e tutta la storia del dover stare in fondo all’autobus”. Fu condannato ad un anno con la condizionale. Ma il rapporto Knepper Mingus non finì certo qui). Eppure Mingus continua a sperimentare, ed è sempre un grandioso musicista: lo dimostrano dischi come Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus e Oh Yeah (scritti tra il 1960 e il 1961, appena prima della lite con Knepper). Ma qualcosa è rotto, e il famoso concerto per le cui prove picchiò Knepper alla Town Hall fu un fiasco colossale, fu persino fischiato. Mingus sente che è tempo di pensare a sé e fa una decisione straordinaria: sull’orlo di una sorta di crisi personale, di sua spontanea volontà si ricovera al Bellevue Hospital per farsi curare nel reparto psichiatrico. Lì conosce il dottor Edmund Pollock, che diviene il suo psicoterapeuta e che scriverà le note del libretto del disco di oggi, uno dei più grandi capolavori del jazz: The Black Saint and The Sinner Lady. Registrato in una sola, incredibile giornata di registrazioni, il 20 gennaio 1963 a New York con l’ausilio del grande produttore Bob Thiele, Mingus ha in mente un album, parole sue, di ethnic folk-dance music. Con una band di 11 elementi scrive un concerto pensato per un balletto, che piuttosto che alla grazia del corpo e dell’armonia musicale ha una propria e dirompente natura politica, per delineare le tappe della emancipazione afro-americana, diviso in 4 suite (che hanno un titolo ed un sottotitolo e la cui quarta parte ha 3 sotto sezioni), di 40 minuti, dove rielabora la musica pianistica, il blues, brani da dance hall sofisticate, addirittura la musica andalusa in un continuum sonoro senza soluzione di continuità trascinante e incredibilmente emozionante. Solo Dancer accende la miccia, tra una batteria che ispirerà persino la funk music anni ‘70, e un volo di sax leggendario; Duet Solo Dancers ha un interludio clamoroso di chitarra; Trio Dancers è un complesso, e magnifico, gioco tra orchestra e sax trombone, che davvero richiama il tanto odiato free jazz per la sua aerea composizione; Trio and Group Dancers è l’apoteosi, 18 magici, ipnotici e trascinanti minuti di pura potenza mingusiana, un vulcano in piena, nello stile incredibile e forsennato di un genio. Il Dottor Pollock scrive in copertina:”Mingus ha qualcosa da dire e usa qualsiasi cosa per far interpretare il suo messaggio (…) la sua musica è un appello all’amore, al rispetto, alla reciproca accettazione e comprensione, libertà e amicizia”. Costantemente tra i dischi più belli della storia del jazz, è una parentesi di genio in un periodo di profondissimo disagio: iniziò a litigare con chi lo chiamava Charlie, gli organizzatori, i proprietari dei Club (sfasciò un faro di illuminazione al Village Vanguard che divenne una sorta di reliquia per gli avventori)i critici e ovviamente il free jazz. Per un certo periodo decise di non suonare più, e si rintanò nel suo appartamento: finì per essere sfrattato e lui trasformò quel mesto trasloco in una semidelirante manifestazione affidata ad un cineasta che lo riprendeva (Thomas Reichman) e accompagnata da lettere indirizzate a papa Paolo VI, il Presidente Lyndon Johnson, Charles De Gaulle per accusare l’FBI di averlo sfrattato. La situazione peggiorò moltissimo quando scoprì di avere il morbo di Gerhing, che ben presto lo costrinse alla sedia a rotelle. Tra coloro che lo andarono a trovare, c’era pure un trombettista a cui una volta ruppe un dente. Lo aveva perdonato.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

11:05 PM EDT October 29, 2024:

Charles Mingus - "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" From the album Mingus Ah Um (September 14, 1959)

Last song scrobbled from iTunes at Last.fm

File under: Post-bop

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jazz on a Summer’s Day

JAZZ ON A SUMMER'S DAY

They say that 1959 was the year that changed jazz. It was the period when the music broke away from its traditional modes to create new forms, specifically allowing soloists to break free and express themselves. It was year that America: the found its groove with jazz leading the charge. The list of albums that were released that year is just incredible - check them out.

However when scholars and aficionados talk about music in that year four jazz albums are cited, each a high point for the artists concerned and a real soundtrack of the times and all four stand up to this day and somewhat. They are:

Miles Davis, Kind of Blue

Dave Brubeck, Time Out

Charles Mingus, Mingus Ah Um

Ornette Coleman, The Shape of Jazz to Come

All four may be different but they are equally sublime. They are timeless and to have heard them contemporaneously must have been something else. The albums, jazz and that period of time has established itself as an integral part of American history and it quickly found itself an audience and voice in the jazz clubs, nightclubs and parties on this side of the Atlantic as well. Jazz - especially Trad Jazz - was huge in the UK at the end of the 1950s and the aficionados, beatniks and modernists quickly lapped up this modern jazz creating friction - that led to numerous verbals and fist fights between the Trads and Moderns. For this was modern and new. Frightening, exciting, exhilarating and refreshing.

Like the music the shift was rapid and the records soon found their way into the stores the length and breadth of the country. The kids snapped them up, played them, danced to them and nodded their heads to them. And whilst ding this they studied the album covers of all these new imported sounds on the Verve, Blue Note and Capitol labels. See, it was more than the music. It was also about the style, the clothes, the colours, the modernist art, architecture and furniture, and the graphic design. It was Hollywood PLUS! Britain was looking west. Cigarettes, glamour, bourbon, Ivy League clothing and jazz. As the legendary retailer and original modernist John Simons says on his company's website: "I came to art really through record covers, I was extremely interested in the Bebop revolution in America in the post-war years. I would always find myself in record stores looking at the covers. They were very often done by interesting modern artists, which reflected the music. As a fourteen and fifteen-year-old that drew me to it. To me the Bebop revolution made the Punk revolution look like right wing conservatives! So far out man… I can’t even tell you."

Then in August 1959 a small independent film was released that gave the UK modernists a visual interpretation of their new-found music. Entitled Jazz On A Summer's Day the film is a dazzling documentary of the Newport Jazz Festival held a year earlier on Rhode Island, USA. The festival was founded in 1954 and soon became the hippest event in the country. It wasn't long before Bert Stern, a young New Yorker specialising in "still" advertising photography, had the bright idea of filming the Newport Jazz Festival, in which 50 top-flight American jazz musicians and vocalists took part and to which jazzanistas in their legions flocked from all over. Stern has a wonderful gift for capturing the colour, style and panache of the venue, artistes and audience. He then intersperses this with film of the city of Newport from the harbour with its racing yachts skimming gracefully over the sparkling and shimmering water to shots of kids paying on the beach and onto the cool cats arriving at the event.And “cool” is the word.

The music featuring the Jimmy Giuffre 3, Thelonious Monk Trio, Dinah Washington, Louis Armstrong and Mahalia Jackson to name just a few is scintillating. The multi-racial crowd has never been hipper and as day turns to night Stern and co-director Aram Avakian capture a vibe that is like nothing anybody had seen, heard or felt before in America or at one of the few cinemas that showed it in the UK. The reviews were superb, those that saw it had now bought into this whole new scene and Britain edged that little bit closer to the 1960s...

FOOTNOTES

In 2020 the film was given a new 4K restoration by IndieCollect, and premiered at the 57th New York Film Festival - the trailer looks fantastic . It was meant to have a cinema and Netflix release but due to Covid this doesn't seem to have happened. You can however watch the pre-restored version on Vimeo and Youtube.

Meanwhile the photos that accompany this piece are from the incredible book Jazz Festival by Jim Marshall and released by Reel Art Press. The book includes photos from the 1958 festival - amongst other years - and Marshall can actually be seen on the film. If you haven't done so already then check out the book!

9 notes

·

View notes