#Medvigy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

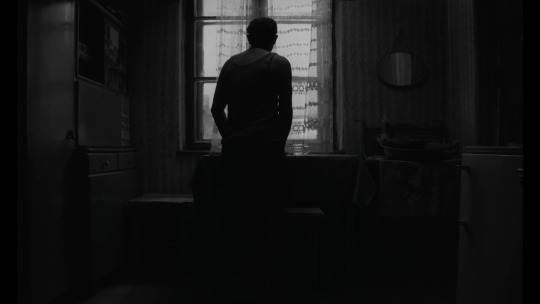

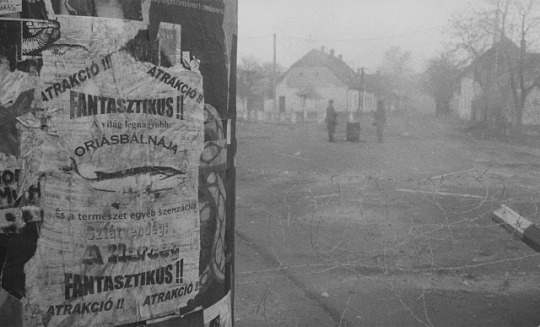

Sátántangó (1994)

Country: Hungary / Germany / Switzerland

Directed by: Béla Tarr

Cinematography by: Gábor Medvigy

#Satantango#Béla Tarr#Gábor Medvigy#Hungary#Germany#Switzerland#Arthouse#Existential#Surreal#Crime Drama#1990s

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Werckmeister Harmonies (Béla Tarr, Ágnes Hranitzky, 2000)

Cast: Lars Rudolph, Peter Fitz, Hanna Schygulla, János Derszi, Doko Rosic, Tomás Wichmann, Ferenc Kállai, Péter Dobai. Screenplay: László Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr, based on a novel by Krasznahorkai. Cinematography: Patrick de Ranter, Miklós Gurbán, Erwin Lanzenberger, Gábor Medvigy, Emil Novák, Rob Tregenza. Film editing: Ágnes Hranitzky. Music: Mihály Vig.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sátántangó (1994)

#film#movie#Sátántangó#satantango#tarr#Krasznahorkai#Hranitzky#Medvigy#Mihály Vig#Putyi Horváth#László feLugossy#Peter Berling#Erika Bók

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Bela Tarr#Béla Tarr#Werckmeister harmóniák#Werckmeister Harmonies#2000#best of 2000#slow cinema#arthouse#hungarian film#hungarian cinema#masterpiece#black and white#melancholia#michaly vig#Gábor Medvigy#László Krasznahorkai#drama#Werckmeister harmoniak

49 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

2017 FILMNAPLÓ

#16: KÁRHOZAT

hihetetlen, hogy ilyen filmeket még mindig nem láttam. tartottam tőle, pedig a legkönnyebben nézhető Tarr, amit eddig láttam (Sátántangó, Werckmeister, Londoni, Torinói). nagyon szép. tartalmilag, vizuálisan, szövegileg is. ha csak Medvigy-állóképek lennének Krasznahorkai-narrálva, már az zseniális lenne.

na meg ez a dal.

#víg mihály#tarr béla#krasznahorkai#medvigy#film#zene#magyar film#magyar zene#kárhozat#damnation#bela tarr#filmnaplo#2017 filmnaplo

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

aaawww

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

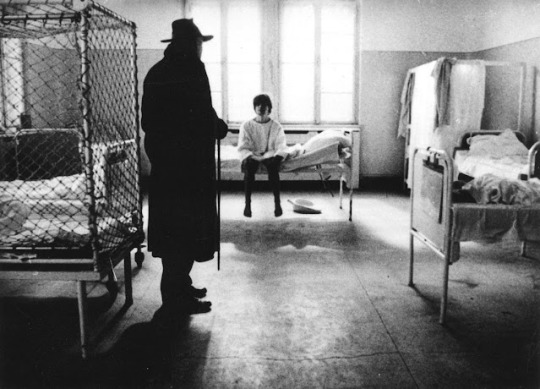

Damnation (Kárhozat, 1987, Béla Tarr)

#damnation#belatarr#cinema#film#black-and-white#mother#blackandwhitefilm#hungarian#kárhozat#cinematography#gábor medvigy

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sátántangó (1994)

Béla Tarr

270 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sátántangó (1994)

#1990s#actor erika bok#dir bela tarr#dp gabor medvigy#hungarian#german#swiss#monochrome#through glass#just eyes#water#child#satantango

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Werckmeister harmóniák ~ Werckmeister Harmonies (2000 - Béla Tarr)

#werckmeister harmóniák#werckmeister harmonies#béla tarr#bela tarr#agnes hranitzky#mihály vig#lars rudolph#peter fitz#hanna schygulla#mihály kormos#patrick de ranter#miklós gurbán#erwin lanzensberger#gábor medvigy#emil novák#rob tregenza#karanlık armoniler#hungarian cinema#2000#best of 2000#best films of 2000#movie#film#cinema#2000 movies#masterpiece

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kárhozat

(Punição)

H, 1988

Béla Tarr

9/10

.

Descida ao inferno

Béla Tarr é um realizador genial mas com uma linguagem francamente pesada para a maioria dos públicos. Eu sou um daqueles que gosta de se deleitar com um filme lento mas belo, como quem saboreia um excelente whisky e quer fazer durar o prazer no palato. Aqui temos tempo para saborear até à exaustão a bela cinematografia de Gábor Medvigy e esta visão dantesca da Hungria perestroikiana que nos é apresentada por Tarr (e seria desenvolvida ad nauseam em Satántango alguns anos depois). É uma visão cínica não apenas do regime mas também da própria natureza humana, feita por quem se mostra profundamente cético quanto às virtudes da nossa espécie.

Paradoxalmente esta visão negra e infernal da humanidade resulta extremamente bela quando filmada sob a direção de Tarr. Não só a já citada cinematografia é magnífica como também a música (ditirâmbica, raiando o depressivo), o ritmo do filme (oscilando entre o lento e o incrivelmente lento), os cenários (ruas lamacentas, clubes decrépitos, carros provectos), os personagens (miseráveis, quase patéticos) e a própria trama (perversa e totalmente desprovida de escrúpulos).

Quem aprecie o lado negro da vida exulta com esta visão terrível de Tarr. Para quem busca otimismo na arte então este filme é uma verdadeira descida aos infernos.

.

Descent into hell

Béla Tarr is a brilliant director, but his language is frankly heavy for most audiences. I am one of those people who likes to enjoy a slow but beautiful film, like someone who enjoys an excellent whiskey and wants to make the pleasure last on the palate. Here we have time to savor until exhaustion the beautiful cinematography of Gábor Medvigy and this Dantesque vision of perestroikian Hungary that is presented to us by Tarr (and would be developed ad nauseam in Satántango a few years later). It is a cynical view not only of the regime but of human nature itself, by someone who is deeply skeptical of the virtues of our species.

Paradoxically, this dark and hellish vision of humanity is extremely beautiful when filmed under Tarr's direction. Not only is the aforementioned cinematography magnificent, but so is the music (dithyrambic, bordering on the depressive), the pace of the film (oscillating between slow and incredibly slow), the settings (muddy streets, decrepit clubs, well-worn cars), the characters (wretched, almost pathetic) and the plot itself (perverse and utterly unscrupulous).

Those who appreciate the dark side of life exult in this terrible vision of Tarr. For those looking for optimism in art then this film is a true descent into hell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Damnation

Dir: Béla Tarr

Cin: Gábor Medvigy

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sátántangó, 1994

Director: Béla Tarr

Based on: Satantango; by László Krasznahorkai

Cinematography: Gábor Medvigy

Language: Hungarian

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sátántangó (1994)

#film#movie#Sátántangó#satantango#tarr#Krasznahorkai#Hranitzky#Medvigy#Mihály Vig#Putyi Horváth#gente#libertà#paura#vita#ordine#autorità#passione

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Béla Tarr#Bela Tarr#2000#Werckmeister harmóniák#Werckmeister Harmonies#slow cinema#black and white#arthouse#hungarian film#Gábor Medvigy#Emil Novák#Rob Tregenza#Mihály Víg#hungarian director#masterpiece#hungarian cinema#best of 2000#melancholia#end of the world

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sátántangó Experience

How exactly does one prepare to watch a 7.5 hour film? A bit like what you might do in preparation for major surgery: Pack a bag of necessities (in this case, water and protein bars), kiss your loved ones goodbye, and try to make peace with your god. Or, maybe less dramatically, treat it as you would a long train journey, one that takes you through some harrowing terrain on half a rutted track before depositing you to your eventual destination.

Of course, this sort of conception of time is entirely relative: If you have to drive somewhere that takes half an hour, it feels unduly long; but if the trip were normally three hours long, and you somehow found a shortcut that would cut the time down to 30 minutes, you would be flying on dulcet wings for that amount of time, and think you were blessed by angels. In other words, spending an entire standard work day watching one film might seem excessive, but it all has to do with your expectations.

In my case, I was at Philadelphia’s newly renovated Lightbox Theater at the University of the Arts to take in Béla Tarr’s magnum opus Sátántangó, all glorious 450 minutes, in a new 4K restoration (it’s currently playing at select theaters across the country). Armed with my snack survival kit, and safe in the knowledge that we would get intermissions at roughly 2.5 hour intervals, I settled in to watch what has been described as a masterpiece in cinephile circles, and currently resides at number 36 in the most recent Sight & Sound critics’ poll.

Tarr’s beyond-bleak film is broken up into 12 segments, each having to do with a failing farmer’s cooperative in Hungary during the last throes of communism in the late ‘80s. Each section has its own feel and perspective — some of them are more lighthearted, others are desolate beyond measure — but all expertly shot in low-contrast black and white (by Gábor Medvigy), which renders the people and landscape in various tones of drudgery grey.

It originally opened in America as part of the 1994 New York film festival, at a time when Hungary was undergoing a transformation from Communism to shaky democratic capitalism, so it served as a kind of epigraph to the era, a showcase, as it were, as to the imperfections of a political system built on a promise of human egalitarianism that proved to be depressingly difficult to put into practice.

The landscape makes up a lot of Tarr’s vision, the flat, moody farmland upon which the collective has been toiling, and the unceasing rain and wind that constantly pelts the characters as they venture outside for one business or another. As the film opens, the collective — made up of three couples; a curious “doctor” (Peter Berling), who spends his time spying on the others, making copious notes in his stacks of file folders, and daily drinking his considerable body weight in Palinka (Hungarian plum brandy); and the cagey Futaki (Miklos Szekely B.), who has to walk with a cane from an unspecified accident, but seems a bit more shrewd than the others — is anxiously awaiting their annual wages, which come all at once and is meant to get divvied up amongst the members equally.

Early on, there are various halfcocked plans from individuals to try and steal the small fortune for themselves, reflected in much idle talk about meeting that evening and decamping for parts unknown, but that ultimately come to nothing. However, when word reaches the group that the mysterious Irimiás (Mihály Vig, also the film’s composer) is, in fact, not dead as they had been told, but alive, and returning to the collective he started, the group dynamic is thrown akimbo, with various members fretting for their future, and, one, the owner of the local bar (Zoltán Kamondi), furious at the thought his business will be taken from him.

Just why they respond like this remains vague. In ensuing segments, we see Irimiás, along with his associate, Petrina (Dr. Putyi Horvath), navigating through a police interview — where the local Captain informs them they will be working for him now in ways unspecified — though it appears the collective had very actively planned on not having to include their former leader (and his right-hand man) in their financial arrangements. As for the non-collective characters, including the aforementioned barkeep, and various prostitutes sitting idly around, the collective is virtually their only business, such as it is, so they, too, await this potential flood of cash eagerly.

As the segments begin to collect, they also begin to fold upon themselves: Scenes that we see from one vantage point in an earlier segment are revisited later on, from the perspective of a different character, enabling a thrilling moment of realization that the stream of time we’re following has breaks, jumps, and hiccoughs throughout. Never more poignantly than a moment with a young girl peering into a window of the bar — one of the only lit buildings in the otherwise dismally dark countryside — watching the adults inside drunkenly dancing and cavorting.

About that girl. Easily the most emotional moment of the film involves her, but not first without the audience paying a heavy price, depending on your empathy for other creatures. Before the film screened, during its introduction, we were made aware that there was a scene of animal cruelty involving a cat somewhere in the proceedings. The sympathetic presenter, himself a cat lover, suggested looking away for parts of that segment, though a friend of mine in attendance who had seen it before assured me looking away wasn’t really an option. Fortunately, he also told me that the cat in question wasn’t actually hurt, and was still alive at the time of a 2012 interview with Tarr.

Needless to say, my worry about this poor cat dominated my experience in the early going: Every time I saw a feline in the background of a scene, I worried that it was coming up, such that it was almost a relief when it finally happened. The situation is this: Estike (Erica Bók), the young daughter of one of the local prostitutes, caught up in her world of half-fantasies after being sent out of their apartment by her working mother, holes up in an attic with a grey tabby. At first, she pets and cuddles him, but eventually, she desires to control him, bend the cat to her will. To the cat’s increasing discomfort and fury, she grabs him by the front paws and rolls around with him, all the while muttering how she alone can determine its fate. Looping up the poor fellow in a net bag and hanging it from a post, she goes downstairs to mix a batch of milk with some rat poison powder and force feeds him until he dies (though in actuality merely tranquilized).

Wandering around the farm that night with the stiffened body of the cat tucked under her arm (a prosthetic, the director assures us), Estike runs into the doctor, shuffling outside to refill his giant jug of brandy, shortly after peering through the window of the bar. Eventually, she lies down amongst the deserted crumble of a bomb-blasted church and takes the poison herself.

As gruesome as the segment becomes, its haunting evocations permeate the rest of the film (though not immediately: in a jarring juxtaposition, the very next segment takes us back to the bar, where everyone is still dancing wildly about to a loopy accordion refrain — only towards the end of this extended scene do we see the face of the soon-to-be-dead Estike peering inside). Eventually, Irimiás does indeed return, in time to give a moving eulogy for Estike, while at the same time transitioning the group towards his next vision, a new farm some distance away where he assures them they can finally live freely and thrive. All he needs to achieve this goal for them is the money they just received from their previous year’s efforts.

With nowhere else to go, and no other plan on the horizon, the members of the collective dutifully deposit their wages on the table in front of their leader. He sends them out to pack their things so that they may meet with him in a couple of days at the new farm he’s selected.

Gathering their miserable belongings, the group reassemble and trudge down the muddy road on foot, as the rain pelts down on them without ceasing. Distressingly, the members don’t have any proper rain coats — in an earlier soliloquy in the bar, Kráner (János Derszi) laments that his leather coat is so old and stiff he has to bend it in order to sit down — so they wear their woolen winter coats, which do little to keep them from getting soaked in the heavy fall rains.

As they make their way to this new destination, it’s clear that Irimiás is up to something. Most obviously, he could make off with their wages and move on, but it turns out his scheme is less direct than just taking their hard-earned money for himself.

Towards the second half, Tarr’s penchant for long, elegantly composed shots gives gradually away to more adventurous camerawork, including a single steadicam shot in the woods that’s like something out of a Sam Raimi film. There are extensive elliptical shots with the camera spinning slowly on an axis, this particular effect never more effective than when after the group arrives at their new farm, yet another dilapidated series of box-like concrete buildings. Once they dump their belongings and lie on the floor of the unheated, broken-windowed main house, trying to sleep, our narrator makes one of his occasional VO appearances to describe in intimate detail the dreams each character is having.

It’s a shot that could have served as an excellent final salvo, one would imagine. Indeed, by the last hour of this opus, time and again, Tarr arrives at what might be considered a conclusive moment — in this, the confusion is aided by his particular style: It turns out many films end on a superbly composed, static long shot — only to keep the narrative flowing, circling back, eventually to the original farm, where the doctor, having just returned from a stint in a hospital, begins to narrate, again, the original opening lines. Such is the perfection in this device (the segment is titled “The Circle Closes”) that once you finally arrive there, it’s clear there could be no other ending that would have sufficed.

When finally the film ended, it was later in the evening. I met up with my compatriots also in attendance, and the three of us ventured back out into the city, heading to a bar where we could nurse a beer and attempt to articulate the tangled mass of feelings and impressions of the previous nine hours. In one of the very few bars in the city that still allows smoking, appropriately enough, we debated about the film in an atmosphere swirling with the poisonous fumes of an earlier era. It seemed hopeless, but still necessary, somehow; like bidding farewell to someone already in a coma.

#sweet smell of success#ssos#piers marchant#films#movies#satantango#bela tarr#hungary#communism#Mihály Vig#philadelphia lightbox theater

2 notes

·

View notes