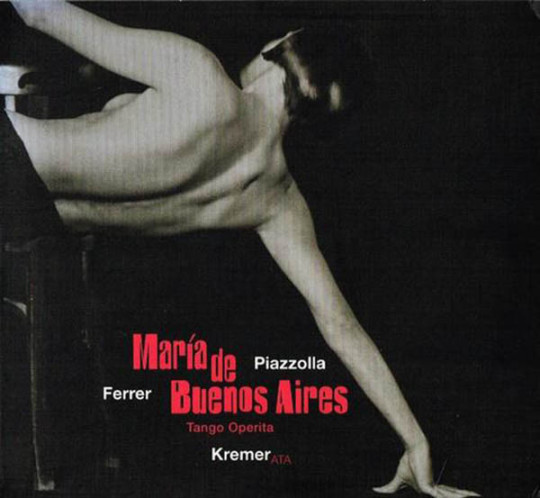

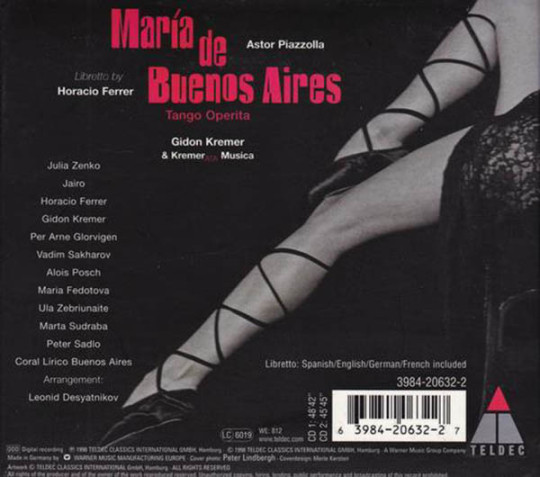

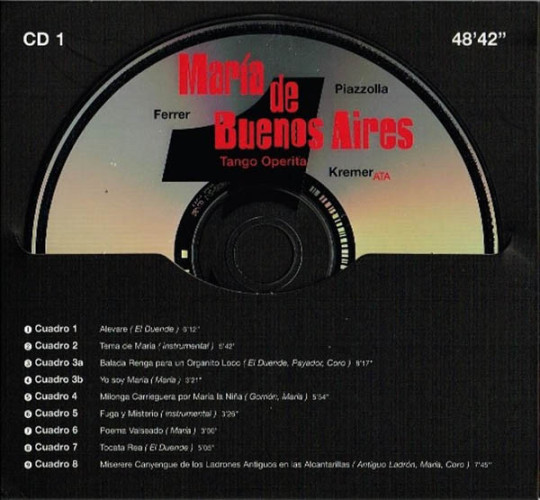

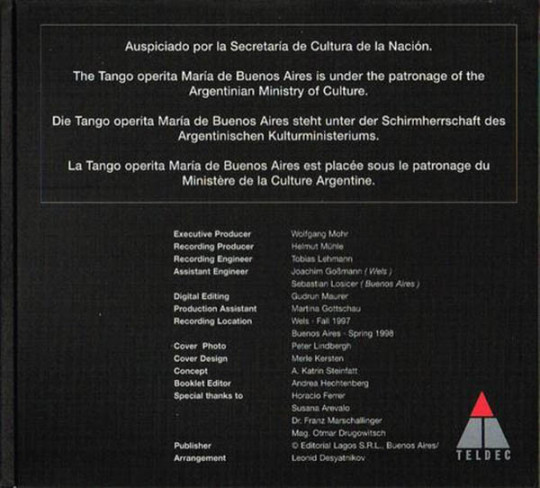

#Maria de Buenos Aires

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

brass of the royal concertgebouw orchestra

youtube

maria de buenos aires *piazzolla *ferrer *kremer

1968

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grace Elizabeth Vainik and Yehor Barshak skating to María de Buenos Aires for their rhythm dance at the 2022 Junior Grand Prix Riga.

(Source: Getty Images Sport)

#Grace Elizabeth Vainik#Yehor Barshak#Vainik Barshak#Figure skating#Ice dance#Georgia#Maria de Buenos Aires#Astor Piazzolla#Tango#2022–2023#2022 Junior Grand Prix Riga

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

fue por vos angelito, por vos este equipo es campeón, somos bicampeones de América por vos, gracias y miles de gracias porque un Dios siempre tiene su Ángel al lado💗

#argentina#mejor pais del mundo#scaloneta#fideo#angel#angel di maria#legendary#copa américa 2024#copa america#sos lo más grande final de la copa del mundo#bicampeones#buenos aires#somos lo mejor del mundo#campeones del mundo#campeones#afa

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muro se mostró a favor de que Mar del Plata sea subsede del Mundial 2030

Como ya es sabido, Mar del Plata se postulará para ser una de las subsedes del Mundial de Fútbol de 2030, en caso de que la Argentina, junto a Uruguay, Paraguay y Chile, sea designada por la FIFA para organizar la máxima competencia del fútbol internacional. En estos días, las distintas dependencias comunales están recolectando y elaborando documento con “datos duros” sobre la ciudad, tal cual lo…

View On WordPress

#Argentina#Buenos Aires#Chile#Diego Santilli#Diputados#El Cambio de Nuestras vidas#Estadio Jose Maria Minella#Fernando Muro#Juntos por elCambio#JxC#Mar del Plata#Portada#Uruguay

0 notes

Text

La virgen Maria y la Visitación a Santa Isabel

La celebración de la visita de María a Santa Isabel es un recordatorio de que Dios viene al hombre de una manera inesperada y sorprendente. Viene en situaciones desesperadas, vejez y decepción de la vida, esterilidad y un sentido de desgracia, o cuando una persona parece demasiado joven, no preparada para asumir desafíos. Pero esta es una fiesta que habla del poder de Dios. Es Él quien elige la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

HAPPY PRIDE MONTH

As every year this is a good date to remember the daily struggle for the rights of the LBGT+ community. It is also a time to learn about the people who made it possible for us to identify ourselves as who we are today without fear of reprisals or being punished by the law. This month I got involved in the history of Argentina and its different movements for the fight for rights through the 20th century. Here I come to share some important figures, some more known than others, but obviously there are a lot that I have left out of this publication.

Sara Facio (1932-2024) & Maria Elena Walsh (1930-2011)

A couple of intellectual artists that would need a separate publication to go deeper into the subject. Sara is one of the greatest Latin American photographers who with her camera contributed to the creation of the most outstanding photographic heritage of the country. Maria Elena is a writer, singer and composer whose children's songs resonate to this day because they are much more profound than they seem and are still relevant today.

Salvadora Medina Onrubia (1894-1972)

She was a writer, militant anarchist, single mother and the first woman to run a newspaper in the country. She was the first Argentinean woman to dare to write about double sinners, lesbians and adulteresses. One of her most valued plays was Las descentradas, premiered in 1929. There, Salvadora honors her own contradictions, narrating women who question monogamous structures, marriage and the traditional family.

Malva Solis (1920-2015)

She was a transvestite writer who lived for 95 years when the life expectancy of this community in the country was under 40 years old. In 1951 founded the first trans organization on record, Maricas Unidas Argentinas. She has the oldest series of trans photographs in the country, dating from 1940 to 1980, when simply having those photographs at home was cause for being arrested. There is a documentary based on the photographs and conversations with her at her home called "Con Nombre de flor".

Jorge Horacio Ballve Piñero (1920-?)

Piñero was a young man from a well-to-do family of the Buenos Aires society at the beginning of the century. Together with his best friend Adolfo and Blanca, he organized gatherings in his apartment in Recoleta, and was a pioneer of male erotic photography. They mixed the privileged social class with workers, dishwashers, gas station workers, sailors and cadets from the Military College. These three characters were involved in a police case involving cadets from the military college, known as the Cadet Scandal. In the police archives remain captive the photographic collection, intended for pleasure and personal aesthetic enjoyment that tragically proved key to incriminate some friends who just wanted to have fun.

Ruth Mary Kelly (1925-1994)

She was a bisexual woman, who worked as a "Wohoo Worker". Founder of Grupo Safo in 1972, the first Argentine lesbian organization, and of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (Homosexual Liberation Front). In 1972 she wrote Memorial de los Infiernos about her experiences as a "Wohoo" worker and bisexual, persecuted by the psychiatric-prison system.

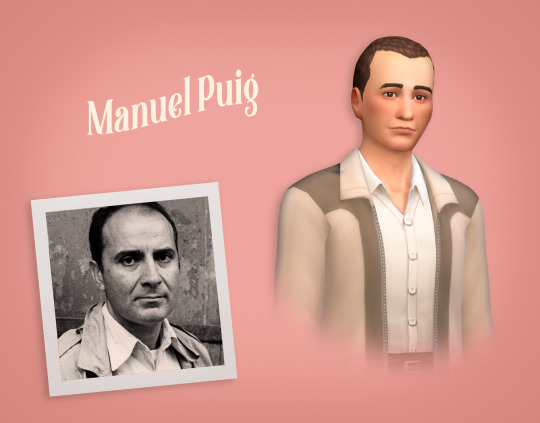

Manuel Puig (1932-1990)

He was an Argentine writer and LGBT+ activist, author of the novels Boquitas pintadas, El beso de la mujer araña (Considered one of the most recognized LGBT works in Latin America and one of the best works in Spanish of the 20th century) etc. He also fought against authoritarianism and machismo, and was one of the founders of the Homosexual Liberation Front in 1971, one of the first associations for the defense of LGBTQI+ rights.

Mariela Muñoz (1943-2017)

She was the first transsexual woman to be recognized by the state and given a female ID card on May 2, 1997. At the age of 16 she became independent, and it was then that she began caring for children, teenagers and single mothers. She cared for children who had been abandoned by their mothers, whom she loved and cared for. She raised, during her lifetime, 23 children and 30 grandchildren. In a dispute over the guardianship of 3 children in 1993, Argentina was confronted for the first time with the debate as to whether a transsexual person "could be a mother"

Carlos Jauregui (1957-1996) & Raul Soria

Carlos was a History professor and the founder of the Civil Association Gays for Civil Rights, organizer of the first Pride march in Buenos Aires and an essential figure for Argentine activism. In 1984, he broke with the schemes by appearing in the magazine Siete Días embracing the activist Raul Soria, a homosexual person assumed his sexuality in a public way for the first time. He believed that media visibility is fundamental for LGTB people. Leaving aside the fear and silence that other generations suffered for years. In 1985, Raul would present himself as the first gay candidate for congressman in the country.

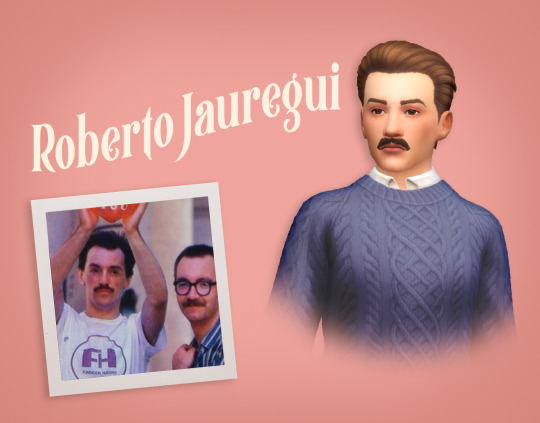

Roberto Jauregui (1960-1994)

Brother of Carlos, was a journalist, actor and the first activist for the rights of people with HIV in the country. In 1989 he exposed the inequality in access to treatment at that time due to the price of medication. He played a central role in marches, actions, talks and interviews to demand human rights for people living with the virus. A well-known phrase of his is "Showing one's face is not easy in a society that discriminates, censures and separates".

Cris Miró (1965-1999)

Cris was the first visible trans people that appeared in the media and broke with the "transvestite" paradigm. A dental student, she got involved in the artistic underworld and later studied classical dance, musical comedy and acting. Her career was meteoric: the popularity of revue theater catapulted her to the small screen where she became a sought-after figure in the most popular programs. On June 23rd, a series about his life inspired by his biography was released, available on Prime Video.

Alejandro Vannelli (1948-) y Ernesto Larresse (1950-)

They were the first couple in the province of Buenos Aires to get legally married on July 30, 2010 after the Equal Marriage Law was passed. They met in 1976 because of a triple A bomb in the theater where Larresse was performing with Nacha Guevara, then he joined the cast of Vannelli. At the beginning they did not like each other because of Vanelli's appearance as a wealthy young man and Larresse was the opposite, but opposites attracted and they were a couple for 34 years.

Norma Castillo (1943-) y Ramona "Cachita" Arévalo (1943-2018)

They were the of South America's first gay marriage on April 9, 2010. Norma and Ramona were married to two Colombians, who were cousins to each other. During the dictatorship they both went into exile in Colombia and there they fell in love and lived their romance clandestinely, until Cachita separated and Norma was widowed by her husband. They lived their love freely and even opened an LGBT discotheque in Colombia. In 1998 they returned to Argentina and began to work in sexual diversity organizations.

Feliciano Centurión 1962-1996)

He was a visual artist, a Paraguayan painter professionally trained in Argentina. He grew up in a home dominated by women, where he learned to sew and crochet. Inspired by queer aesthetics and folk art, he used to incorporate household textiles and references to the natural world. She handled kitsch art and languages not considered high art with a great deal of knowledge and sensitivity.

Humberto Tortonese (1964-) , Alejandro Urdapilleta (1954-2013) & Batato Barea (1961-1991)

Batato was an actor and "literary transvestite clown" as he called himself, one of the most important personalities of the underground theater movement of the post-dictatorship years. Together with Alejandro Urdapilleta and Humberto Tortonese, revolutionized the underground scene of the 80's - in places like the Parakultural. They disguised themselves, wore make-up and improvised delirious and strident scenes for the decade.

Sandra Mihanovich & Celeste Carballo

Sandra and Celeste are two singers who were visibly lesbians during the 80s and early 90s. Together they released the albums "Somos mucho mas que dos" and "Mujer contra mujer" which became a symbol of belonging for the whole LGBTQ arc in our country. They managed to be part of the rock scene, an area historically dominated by men. Sandra among all her songs is "Soy lo que soy" released in 1984 composed by Henry Jerman.

#Argentina LBGT#Lgbt Latin America#ARG Queer#lgbt#lgbt love#gay pride#bisexual pride#lesbian pride#pride month#the sims 4#sims 4 pride#sims 4 edit#sims 4 render#ts4 lgbt#lgbt history#queer history#victorian lgbt#PrideFlagLegacy#pride flag legacy challenge#ts4 historical#sims 4 historical#Cris Miro#Sandra Mihanovich#Celeste Carballo#Maria Elena Walsh#Sara Facio#Ballve Piñero#Carlos Jauregui#Roberto Jauregui#Feliciano Centurión

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rinka Watanabe: Maria de Buenos Aires » 2024 Skate America

#rinka watanabe#fskateedit#figure skating#skate america 2024#SA 2024#program#jp ladies going 1-2 at skate AMERICA???#i'm still in shock lmao#i like this program for rinka#glad she turned it around from her disastrous last few comps#someone please get her a spin doctor though

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

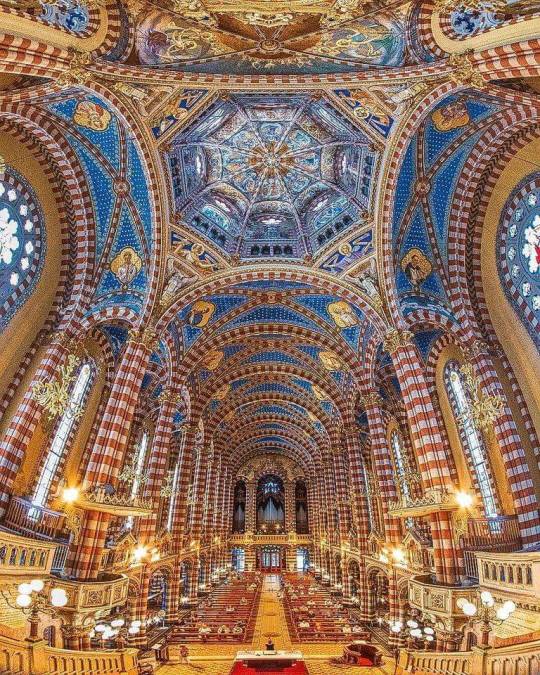

Interior de la Basilica de Maria Auxiliadora y San Carlos Borromeo en Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA

#interior#basilica#maria auxiliadora#mary help#san carlos#saint charles#borromeo#buenos aires#argentina#south america#sur america#america

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

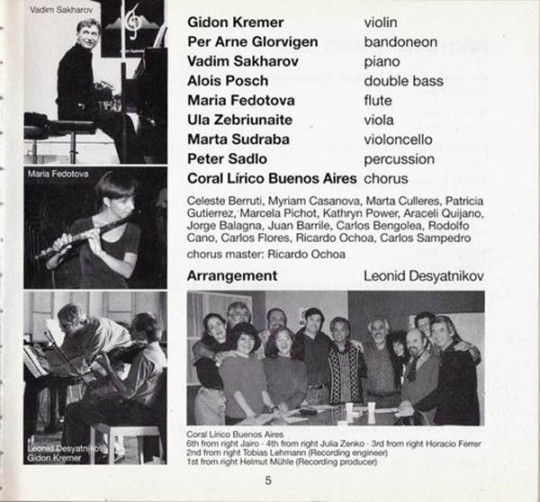

2024 Skate America - October 19, 2024 Rinka Watanabe → Maria de Buenos Aires by Astor Piazzolla, performed by Gidon Kremer and Kremerata Musica, Julia Zenko, choreographed by Lori Nichol 📸 Kenji Ikai for Mainichi Photography

#rinka watanabe#figure skating#fs#skate america#skate america 2024#skam#skam 2024#grand prix series#grand prix series 2024#gp#gp 2024#season: 2024 2025#this is becoming a series

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.3.5 What is Anarcha-Feminism?

Although opposition to the state and all forms of authority had a strong voice among the early feminists of the 19th century, the more recent feminist movement which began in the 1960’s was founded upon anarchist practice. This is where the term anarcha-feminism came from, referring to women anarchists who act within the larger feminist and anarchist movements to remind them of their principles.

The modern anarcha-feminists built upon the feminist ideas of previous anarchists, both male and female. Indeed, anarchism and feminism have always been closely linked. Many outstanding feminists have also been anarchists, including the pioneering Mary Wollstonecraft (author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman), the Communard Louise Michel, and the American anarchists (and tireless champions of women’s freedom) Voltairine de Cleyre and Emma Goldman (for the former, see her essays “Sex Slavery”, “Gates of Freedom”, “The Case of Woman vs. Orthodoxy”, “Those Who Marry Do Ill”; for the latter see “The Traffic in Women”, “Woman Suffrage”, “The Tragedy of Woman’s Emancipation”, “Marriage and Love” and “Victims of Morality”, for example). Freedom, the world’s oldest anarchist newspaper, was founded by Charlotte Wilson in 1886. Anarchist women like Virgilia D’Andrea and Rose Pesota played important roles in both the libertarian and labour movements. The “Mujeres Libres” (“Free Women”) movement in Spain during the Spanish revolution is a classic example of women anarchists organising themselves to defend their basic freedoms and create a society based on women’s freedom and equality (see Free Women of Spain by Martha Ackelsberg for more details on this important organisation). In addition, all the male major anarchist thinkers (bar Proudhon) were firm supporters of women’s equality. For example, Bakunin opposed patriarchy and how the law “subjects [women] to the absolute domination of the man.” He argued that ”[e]qual rights must belong to men and women” so that women can “become independent and be free to forge their own way of life.” He looked forward to the end of “the authoritarian juridical family” and “the full sexual freedom of women.” [Bakunin on Anarchism, p. 396 and p. 397]

Thus anarchism has since the 1860s combined a radical critique of capitalism and the state with an equally powerful critique of patriarchy (rule by men). Anarchists, particularly female ones, recognised that modern society was dominated by men. As Ana Maria Mozzoni (an Italian anarchist immigrant in Buenos Aires) put it, women “will find that the priest who damns you is a man; that the legislator who oppresses you is a man, that the husband who reduces you to an object is a man; that the libertine who harasses you is a man; that the capitalist who enriches himself with your ill-paid work and the speculator who calmly pockets the price of your body, are men.” Little has changed since then. Patriarchy still exists and, to quote the anarchist paper La Questione Sociale, it is still usually the case that women “are slaves both in social and private life. If you are a proletarian, you have two tyrants: the man and the boss. If bourgeois, the only sovereignty left to you is that of frivolity and coquetry.” [quoted by Jose Moya, Italians in Buenos Aires’s Anarchist Movement, pp. 197–8 and p. 200]

Anarchism, therefore, is based on an awareness that fighting patriarchy is as important as fighting against the state or capitalism. For ”[y]ou can have no free, or just, or equal society, nor anything approaching it, so long as womanhood is bought, sold, housed, clothed, fed, and protected, as a chattel.” [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Gates of Freedom”, pp. 235–250, Eugenia C. Delamotte, Gates of Freedom, p. 242] To quote Louise Michel:

“The first thing that must change is the relationship between the sexes. Humanity has two parts, men and women, and we ought to be walking hand in hand; instead there is antagonism, and it will last as long as the ‘stronger’ half controls, or think its controls, the ‘weaker’ half.” [The Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel, p. 139]

Thus anarchism, like feminism, fights patriarchy and for women’s equality. Both share much common history and a concern about individual freedom, equality and dignity for members of the female sex (although, as we will explain in more depth below, anarchists have always been very critical of mainstream/liberal feminism as not going far enough). Therefore, it is unsurprising that the new wave of feminism of the sixties expressed itself in an anarchistic manner and drew much inspiration from anarchist figures such as Emma Goldman. Cathy Levine points out that, during this time, “independent groups of women began functioning without the structure, leaders, and other factotums of the male left, creating, independently and simultaneously, organisations similar to those of anarchists of many decades and regions. No accident, either.” [“The Tyranny of Tyranny,” Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 66] It is no accident because, as feminist scholars have noted, women were among the first victims of hierarchical society, which is thought to have begun with the rise of patriarchy and ideologies of domination during the late Neolithic era. Marilyn French argues (in Beyond Power) that the first major social stratification of the human race occurred when men began dominating women, with women becoming in effect a “lower” and “inferior” social class.

The links between anarchism and modern feminism exist in both ideas and action. Leading feminist thinker Carole Pateman notes that her “discussion [on contract theory and its authoritarian and patriarchal basis] owes something to” libertarian ideas, that is the “anarchist wing of the socialist movement.” [The Sexual Contract, p. 14] Moreover, she noted in the 1980s how the “major locus of criticism of authoritarian, hierarchical, undemocratic forms of organisation for the last twenty years has been the women’s movement … After Marx defeated Bakunin in the First International, the prevailing form of organisation in the labour movement, the nationalised industries and in the left sects has mimicked the hierarchy of the state … The women’s movement has rescued and put into practice the long-submerged idea [of anarchists like Bakunin] that movements for, and experiments in, social change must ‘prefigure’ the future form of social organisation.” [The Disorder of Women, p. 201]

Peggy Kornegger has drawn attention to these strong connections between feminism and anarchism, both in theory and practice. “The radical feminist perspective is almost pure anarchism,” she writes. “The basic theory postulates the nuclear family as the basis of all authoritarian systems. The lesson the child learns, from father to teacher to boss to god, is to obey the great anonymous voice of Authority. To graduate from childhood to adulthood is to become a full-fledged automaton, incapable of questioning or even of thinking clearly.” [“Anarchism: The Feminist Connection,” Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 26] Similarly, the Zero Collective argues that Anarcha-feminism “consists in recognising the anarchism of feminism and consciously developing it.” [“Anarchism/Feminism,” pp. 3–7, The Raven, no. 21, p. 6]

Anarcha-feminists point out that authoritarian traits and values, for example, domination, exploitation, aggressiveness, competitiveness, desensitisation etc., are highly valued in hierarchical civilisations and are traditionally referred to as “masculine.” In contrast, non-authoritarian traits and values such as co-operation, sharing, compassion, sensitivity, warmth, etc., are traditionally regarded as “feminine” and are devalued. Feminist scholars have traced this phenomenon back to the growth of patriarchal societies during the early Bronze Age and their conquest of co-operatively based “organic” societies in which “feminine” traits and values were prevalent and respected. Following these conquests, however, such values came to be regarded as “inferior,” especially for a man, since men were in charge of domination and exploitation under patriarchy. (See e.g. Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade; Elise Boulding, The Underside of History). Hence anarcha-feminists have referred to the creation of a non-authoritarian, anarchist society based on co-operation, sharing, mutual aid, etc. as the “feminisation of society.”

Anarcha-feminists have noted that “feminising” society cannot be achieved without both self-management and decentralisation. This is because the patriarchal-authoritarian values and traditions they wish to overthrow are embodied and reproduced in hierarchies. Thus feminism implies decentralisation, which in turn implies self-management. Many feminists have recognised this, as reflected in their experiments with collective forms of feminist organisations that eliminate hierarchical structure and competitive forms of decision making. Some feminists have even argued that directly democratic organisations are specifically female political forms. [see e.g. Nancy Hartsock “Feminist Theory and the Development of Revolutionary Strategy,” in Zeila Eisenstein, ed., Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism, pp. 56–77] Like all anarchists, anarcha-feminists recognise that self-liberation is the key to women’s equality and thus, freedom. Thus Emma Goldman:

“Her development, her freedom, her independence, must come from and through herself. First, by asserting herself as a personality, and not as a sex commodity. Second, by refusing the right of anyone over her body; by refusing to bear children, unless she wants them, by refusing to be a servant to God, the State, society, the husband, the family, etc., by making her life simpler, but deeper and richer. That is, by trying to learn the meaning and substance of life in all its complexities; by freeing herself from the fear of public opinion and public condemnation.” [Anarchism and Other Essays, p. 211]

Anarcha-feminism tries to keep feminism from becoming influenced and dominated by authoritarian ideologies of either the right or left. It proposes direct action and self-help instead of the mass reformist campaigns favoured by the “official” feminist movement, with its creation of hierarchical and centralist organisations and its illusion that having more women bosses, politicians, and soldiers is a move towards “equality.” Anarcha-feminists would point out that the so-called “management science” which women have to learn in order to become mangers in capitalist companies is essentially a set of techniques for controlling and exploiting wage workers in corporate hierarchies, whereas “feminising” society requires the elimination of capitalist wage-slavery and managerial domination altogether. Anarcha-feminists realise that learning how to become an effective exploiter or oppressor is not the path to equality (as one member of the Mujeres Libres put it, ”[w]e did not want to substitute a feminist hierarchy for a masculine one” [quoted by Martha A. Ackelsberg, Free Women of Spain, pp. 22–3] — also see section B.1.4 for a further discussion on patriarchy and hierarchy).

Hence anarchism’s traditional hostility to liberal (or mainstream) feminism, while supporting women’s liberation and equality. Federica Montseny (a leading figure in the Spanish Anarchist movement) argued that such feminism advocated equality for women, but did not challenge existing institutions. She argued that (mainstream) feminism’s only ambition is to give to women of a particular class the opportunity to participate more fully in the existing system of privilege and if these institutions “are unjust when men take advantage of them, they will still be unjust if women take advantage of them.” [quoted by Martha A. Ackelsberg, Op. Cit., p. 119] Thus, for anarchists, women’s freedom did not mean an equal chance to become a boss or a wage slave, a voter or a politician, but rather to be a free and equal individual co-operating as equals in free associations. “Feminism,” stressed Peggy Kornegger, “doesn’t mean female corporate power or a woman President; it means no corporate power and no Presidents. The Equal Rights Amendment will not transform society; it only gives women the ‘right’ to plug into a hierarchical economy. Challenging sexism means challenging all hierarchy — economic, political, and personal. And that means an anarcha-feminist revolution.” [Op. Cit., p. 27]

Anarchism, as can be seen, included a class and economic analysis which is missing from mainstream feminism while, at the same time, showing an awareness to domestic and sex-based power relations which eluded the mainstream socialist movement. This flows from our hatred of hierarchy. As Mozzoni put it, “Anarchy defends the cause of all the oppressed, and because of this, and in a special way, it defends your [women’s] cause, oh! women, doubly oppressed by present society in both the social and private spheres.” [quoted by Moya, Op. Cit., p. 203] This means that, to quote a Chinese anarchist, what anarchists “mean by equality between the sexes is not just that the men will no longer oppress women. We also want men to no longer to be oppressed by other men, and women no longer to be oppressed by other women.” Thus women should “completely overthrow rulership, force men to abandon all their special privileges and become equal to women, and make a world with neither the oppression of women nor the oppression of men.” [He Zhen, quoted by Peter Zarrow, Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture, p. 147]

So, in the historic anarchist movement, as Martha Ackelsberg notes, liberal/mainstream feminism was considered as being “too narrowly focused as a strategy for women’s emancipation; sexual struggle could not be separated from class struggle or from the anarchist project as a whole.” [Op. Cit., p. 119] Anarcha-feminism continues this tradition by arguing that all forms of hierarchy are wrong, not just patriarchy, and that feminism is in conflict with its own ideals if it desires simply to allow women to have the same chance of being a boss as a man does. They simply state the obvious, namely that they “do not believe that power in the hands of women could possibly lead to a non-coercive society” nor do they “believe that anything good can come out of a mass movement with a leadership elite.” The “central issues are always power and social hierarchy” and so people “are free only when they have power over their own lives.” [Carole Ehrlich, “Socialism, Anarchism and Feminism”, Quiet Rumours: An Anarcha-Feminist Reader, p. 44] For if, as Louise Michel put it, “a proletarian is a slave; the wife of a proletarian is even more a slave” ensuring that the wife experiences an equal level of oppression as the husband misses the point. [Op. Cit., p. 141]

Anarcha-feminists, therefore, like all anarchists oppose capitalism as a denial of liberty. Their critique of hierarchy in the society does not start and end with patriarchy. It is a case of wanting freedom everywhere, of wanting to ”[b]reak up … every home that rests in slavery! Every marriage that represents the sale and transfer of the individuality of one of its parties to the other! Every institution, social or civil, that stands between man and his right; every tie that renders one a master, another a serf.” [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Economic Tendency of Freethought”, The Voltairine de Cleyre Reader, p. 72] The ideal that an “equal opportunity” capitalism would free women ignores the fact that any such system would still see working class women oppressed by bosses (be they male or female). For anarcha-feminists, the struggle for women’s liberation cannot be separated from the struggle against hierarchy as such. As L. Susan Brown puts it:

“Anarchist-feminism, as an expression of the anarchist sensibility applied to feminist concerns, takes the individual as its starting point and, in opposition to relations of domination and subordination, argues for non-instrumental economic forms that preserve individual existential freedom, for both men and women.” [The Politics of Individualism, p. 144]

Anarcha-feminists have much to contribute to our understanding of the origins of the ecological crisis in the authoritarian values of hierarchical civilisation. For example, a number of feminist scholars have argued that the domination of nature has paralleled the domination of women, who have been identified with nature throughout history (See, for example, Caroline Merchant, The Death of Nature, 1980). Both women and nature are victims of the obsession with control that characterises the authoritarian personality. For this reason, a growing number of both radical ecologists and feminists are recognising that hierarchies must be dismantled in order to achieve their respective goals.

In addition, anarcha-feminism reminds us of the importance of treating women equally with men while, at the same time, respecting women’s differences from men. In other words, that recognising and respecting diversity includes women as well as men. Too often many male anarchists assume that, because they are (in theory) opposed to sexism, they are not sexist in practice. Such an assumption is false. Anarcha-feminism brings the question of consistency between theory and practice to the front of social activism and reminds us all that we must fight not only external constraints but also internal ones.

This means that anarcha-feminism urges us to practice what we preach. As Voltairine de Cleyre argued, “I never expect men to give us liberty. No, Women, we are not worth it, until we take it.” This involves “insisting on a new code of ethics founded on the law of equal freedom: a code recognising the complete individuality of woman. By making rebels wherever we can. By ourselves living our beliefs . … We are revolutionists. And we shall use propaganda by speech, deed, and most of all life — being what we teach.” Thus anarcha-feminists, like all anarchists, see the struggle against patriarchy as being a struggle of the oppressed for their own self-liberation, for ”as a class I have nothing to hope from men . .. No tyrant ever renounced his tyranny until he had to. If history ever teaches us anything it teaches this. Therefore my hope lies in creating rebellion in the breasts of women.” [“The Gates of Freedom”, pp. 235–250, Eugenia C. Delamotte, Gates of Freedom, p. 249 and p. 239] This was sadly as applicable within the anarchist movement as it was outside it in patriarchal society.

Faced with the sexism of male anarchists who spoke of sexual equality, women anarchists in Spain organised themselves into the Mujeres Libres organisation to combat it. They did not believe in leaving their liberation to some day after the revolution. Their liberation was a integral part of that revolution and had to be started today. In this they repeated the conclusions of anarchist women in Illinois Coal towns who grew tried of hearing their male comrades “shout in favour” of sexual equality “in the future society” while doing nothing about it in the here and now. They used a particularly insulting analogy, comparing their male comrades to priests who “make false promises to the starving masses … [that] there will be rewards in paradise.” The argued that mothers should make their daughters “understand that the difference in sex does not imply inequality in rights” and that as well as being “rebels against the social system of today,” they “should fight especially against the oppression of men who would like to retain women as their moral and material inferior.” [Ersilia Grandi, quoted by Caroline Waldron Merithew, Anarchist Motherhood, p. 227] They formed the “Luisa Michel” group to fight against capitalism and patriarchy in the upper Illinois valley coal towns over three decades before their Spanish comrades organised themselves.

For anarcha-feminists, combating sexism is a key aspect of the struggle for freedom. It is not, as many Marxist socialists argued before the rise of feminism, a diversion from the “real” struggle against capitalism which would somehow be automatically solved after the revolution. It is an essential part of the struggle:

“We do not need any of your titles … We want none of them. What we do want is knowledge and education and liberty. We know what our rights are and we demand them. Are we not standing next to you fighting the supreme fight? Are you not strong enough, men, to make part of that supreme fight a struggle for the rights of women? And then men and women together will gain the rights of all humanity.” [Louise Michel, Op. Cit., p. 142]

A key part of this revolutionising modern society is the transformation of the current relationship between the sexes. Marriage is a particular evil for “the old form of marriage, based on the Bible, ‘till death doth part,’ … [is] an institution that stands for the sovereignty of the man over the women, of her complete submission to his whims and commands.” Women are reduced “to the function of man’s servant and bearer of his children.” [Goldman, Op. Cit., pp. 220–1] Instead of this, anarchists proposed “free love,” that is couples and families based on free agreement between equals than one partner being in authority and the other simply obeying. Such unions would be without sanction of church or state for “two beings who love each other do not need permission from a third to go to bed.” [Mozzoni, quoted by Moya, Op. Cit., p. 200]

Equality and freedom apply to more than just relationships. For “if social progress consists in a constant tendency towards the equalisation of the liberties of social units, then the demands of progress are not satisfied so long as half society, Women, is in subjection… . Woman … is beginning to feel her servitude; that there is a requisite acknowledgement to be won from her master before he is put down and she exalted to — Equality. This acknowledgement is, the freedom to control her own person. “ [Voltairine de Cleyre, “The Gates of Freedom”, Op. Cit., p. 242] Neither men nor state nor church should say what a woman does with her body. A logical extension of this is that women must have control over their own reproductive organs. Thus anarcha-feminists, like anarchists in general, are pro-choice and pro-reproductive rights (i.e. the right of a woman to control her own reproductive decisions). This is a long standing position. Emma Goldman was persecuted and incarcerated because of her public advocacy of birth control methods and the extremist notion that women should decide when they become pregnant (as feminist writer Margaret Anderson put it, “In 1916, Emma Goldman was sent to prison for advocating that ‘women need not always keep their mouth shut and their wombs open.’”).

Anarcha-feminism does not stop there. Like anarchism in general, it aims at changing all aspects of society not just what happens in the home. For, as Goldman asked, “how much independence is gained if the narrowness and lack of freedom of the home is exchanged for the narrowness and lack of freedom of the factory, sweat-shop, department store, or office?” Thus women’s equality and freedom had to be fought everywhere and defended against all forms of hierarchy. Nor can they be achieved by voting. Real liberation, argue anarcha-feminists, is only possible by direct action and anarcha-feminism is based on women’s self-activity and self-liberation for while the “right to vote, or equal civil rights, may be good demands … true emancipation begins neither at the polls nor in the courts. It begins in woman’s soul … her freedom will reach as far as her power to achieve freedom reaches.” [Goldman, Op. Cit., p. 216 and p. 224]

The history of the women’s movement proves this. Every gain has come from below, by the action of women themselves. As Louise Michel put it, ”[w]e women are not bad revolutionaries. Without begging anyone, we are taking our place in the struggles; otherwise, we could go ahead and pass motions until the world ends and gain nothing.” [Op. Cit., p. 139] If women waited for others to act for them their social position would never have changed. This includes getting the vote in the first place. Faced with the militant suffrage movement for women’s votes, British anarchist Rose Witcop recognised that it was “true that this movement shows us that women who so far have been so submissive to their masters, the men, are beginning to wake up at last to the fact they are not inferior to those masters.” Yet she argued that women would not be freed by votes but “by their own strength.” [quoted by Sheila Rowbotham, Hidden from History, pp. 100–1 and p. 101] The women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s showed the truth of that analysis. In spite of equal voting rights, women’s social place had remained unchanged since the 1920s.

Ultimately, as Anarchist Lily Gair Wilkinson stressed, the “call for ‘votes’ can never be a call to freedom. For what is it to vote? To vote is to register assent to being ruled by one legislator or another?” [quoted by Sheila Rowbotham, Op. Cit., p. 102] It does not get to the heart of the problem, namely hierarchy and the authoritarian social relationships it creates of which patriarchy is only a subset of. Only by getting rid of all bosses, political, economic, social and sexual can genuine freedom for women be achieved and “make it possible for women to be human in the truest sense. Everything within her that craves assertion and activity should reach its fullest expression; all artificial barriers should be broken, and the road towards greater freedom cleared of every trace of centuries of submission and slavery.” [Emma Goldman, Op. Cit., p. 214]

#feminism#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Dreams on Ice practices

Kaori's new SP is to Concierto del Angel (Piazolla).

We have a tango Kaori, I repeat we have tango Kaori choreographed by Rohene Ward.

Rinka SP should be Moonlight Sonata (Rinka's love of warhorses strikes again). FS is Maria de Buenos Aires.

Hana Yoshida once again with the good music choice skates her SP to Temen Oblak (Dark Clouds by Christopher Tin feat Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares)

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kristen Spours skating to Piazzolla for her short program at the 2021 Cup of Austria.

(Source: The Phantom Kabocha)

#Kristen Spours#Figure skating#Great Britain#Women#Astor Piazzolla#Tango#Oblivion#Yo soy Maria#Maria de Buenos Aires#2021–2022#2021 Cup of Austria

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adriana Mirabel Fangio

Personal Information

Occupation: Formula 1 Driver. Date of Birth: January 24th 2002, aged 23. Place of Birth: Buenos Aires, Argentina. Height: 5'.7'' Weight: 118 lbs Team: Alfa Romeo-Maserati F1 Team Driving Number: 24 - for the number of races her grandfather won. Nation: Argentina Best Tracks: Imola, Suzuka, Spa, Silverstone, Interlagos Worst Tracks: Singapore, Baku, Qatar Nicknames: Adri, La Princesa. Hobbies: Cooking, Reading, and Swimming Teammate: Felipe Drugovich

Family (several people here are my own inventions)

Juan-Manuel Fangio - Grandfather

Maria-Anna Fangio - Grandmother

Sebastian Fangio - Father

Francesca Velasquez - Mother

Federico Fangio - Older Brother

Alejandro Fangio - Older Brother

Isabella Fangio - Older Sister

Julian Fangio - Older Brother

Felipe Drugovich - Teammate/Best Friend/Future Boyfriend

Heroes

Kimi Raikkonen

Fernando Alonso

Sebastian Vettel

Sabine Schmitz

24 Facts About Adriana

Adriana grew up mostly as a Ferrari and Mercedes fan, but never supported any one team.

Excelled in school as a kid, and got top grades in all subjects.

Wears her abuelo's signet ring on her middle finger as a good luck charm.

Never got to meet her grandfather, but is said to mirror him most in terms of personality.

Never had a fixed racing number until Formula 1.

She and Felipe pack bonded to each other during their karting days in South America, since they were always the best ones on track.

Develops a friendly rivalry with Franco Colapinto during their shared first full season with Alfa Romeo and Racing Bulls respectively.

An avid swimmer, Adriana tries to incorporate swimming into her training as much as possible, and uses it to de-stress between races.

A huge Boca Juniors supporter since childhood, and loves watching L'Albiceleste as well.

Had a boyfriend in her later karting years, called Damian, who broke up with her because she got called up to Formula Renault instead of him.

Bucks a trend in racing drivers by not moving to Monaco. Instead purchasing a place in Milan as a residence in Europe for the season.

Works with girls in Argentina to get them into karting when she's not driving herself.

Raced under her mother's last name, Velasquez, as a child and into her Formula 2 career so as to avoid getting too much attention and preferential treatment.

Always takes a nap before racing so as to conserve and build up energy in herself.

Prefers spending time by herself after races, reading and drinking mate to unwind.

Has no interest in racing for any other team but Alfa Romeo, or with any other teammate than Felipe.

Doesn't take kindly to people belittling her or talking down to her, and also doesn't have any interest in spending time with the girlfriends of the other drivers.

Speaks Spanish and English fluently, and has a working knowledge of Italian and Portuguese.

Is eager to learn everything she can about her abuelo's time in the sport, and try to learn about the driver he was in his day. Since no real footage remains from those days.

In her second season, she starts a group called 'Equipo 24' - an open group for young girls who want to get into driving. Giving little girls in all 24 cities they go to access to her garage and passes to see the racing.

Felipe is her greatest confidant and source of comfort and safety.

She and Franco are outspoken in their desire for a revival of the Argentine Grand Prix at Autodromo Buenos Aires.

Develops a bit of a bitter rivalry with Lance, seeing him as having sabotaged Felipe's shot at the Aston Martin seat, and not delivering to excuse it.

Her personal motto is: 'Prove Them Wrong'. Which is on the back of her racing helmet. Which also features the Argentine flag, and five stars for her abuelo's championships.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Op zoek naar de verloren tijd in een café te Buenos Aires

Het alfabet maakt dat enkele delen Proust onbereikbaar hoog in mijn boekenkast staan: een paar oude exemplaren, met de wat broeierige omslagen van Wout Muller (van wie ik als prille kunststudent les heb gehad), en enkele nieuwe uitgaves met hun nietszeggende, frisse uiterlijk. Dat zegt iets over mij en Proust op dit moment: of verstoft of maagdelijk weggezet. Ik las maar een paar delen, nooit 'de hele Proust'. Vorig jaar deed lezende vriend P dat wel, vierentwintighonderd pagina's lang. Maar hij is verslagen door een lid van een Argentijnse Proust-boekenclub. Die las Proust drie keer, en daarbij heeft hij een dochter die Albertine heet én die ook nog eens in Parijs woont. Nou jij weer, P!

Ik zag in Utrecht de documentaire 'El Tiempo Recuperado'*, over een boekenclub met oude, enkele heel oude leden. Al zo'n twintig jaar komen ze samen in een café in Buenos Aires om steeds enkele hoofdstukken voor te lezen en af en toe commentaar te geven of vragen te stellen. De film was behoorlijk uitputtend, maar ook ontroerend, vrolijkmakend en op enkele momenten ongemakkelijk. 95 % van de tijd wordt er voorgelezen en met Proust in het Spaans in je oren en in het Engels de ondertiteling lezen is een hele inspanning.

Af en toe schuiven er mogelijk nieuwe leden aan. Een vrouw die nooit iets van Proust gelezen heeft, vraagt of het er in het boek om gaat wie de moordenaar is. Oh nee!, roepen de andere leden lachend in koor. Ook in de bioscoopzaal stijgt er gelach op. Ze wordt niet zozeer uitgelachen; het is de lach van het absurde. Als haar dan even later het vuistdikke eerste deel wordt voorgehouden, deinst ze bijna achteruit op haar stoel. Een passage over de glimlach van een overleden vriend in het boek herinnert een vrouw aan de glimlach van haar overleden man, die zij steeds weer kan oproepen. Alsof hij bijna oplicht in haar geheugen. Ook klinken er zuchten van bewondering en verrukking. En als de vader van de Argentijnse Albertine maar weer eens aan een nieuwkomer vertelt dat hij Proust drie keer heeft gelezen, dan zijn er soms blikken van de anderen. Wat een prestatie, wat een onmogelijkheid!

Voor mij wordt Proust niet opgeroepen door lindebloesemthee maar door de de bloeiende meidoorn. Al zo'n dertig jaar lang laat ik mij ieder jaar voor een bloeiende meidoorn fotograferen. Ook een soort op zoek naar de verloren tijd. In 'Combray' beschrijft Proust de herinneringen van de kleine jongen aan de bloeiende meidoorn: … ze boden me tot in 't oneindige dezelfde charme met een onuitputtelijke overvloed, maar zonder dat ik dieper in hen kon doordringen....”.** De bloesem had iets ambigues voor hem, zoals voor mij de geur het zelfde heeft: verleidelijk van verre, een tikje afstotend van dichtbij. Maar de kleine jongen houdt zo van de meidoorns, dat hij snikkend afscheid van ze neemt.

*'El Tiempo Recuperado' | Maria Alvarez |Argentinië 2020 | zwartwit documentaire 120 minuten

Trailer documentaire : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iER-3qonZJs

** 'Op zoek naar de verloren tijd' – De kant van Swann – Deel Een – 'Combray' | Marcel Proust | vertaling C.N. Lijsen | Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij | 1977

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

El Gato Negro - Café por El Gato Negro Café Por Flickr: El Gato Negro - Café Corrientes, Av. 1669 - Ciudad de Buenos Aires Fotografia por: Maria Jimena Almarza ©Todos los derechos reservados

#cafe#argentina#buenos#aires#el#gato#negro#Café#bar#turismo#corrientes#avenida#clasico#coffe#antiguo#retro#almacen#tango#especias#america#latina#el Gato Negro#flickr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Tetro (2009) - Bennie (Alden Ehrenreich) travels to Buenos Aires to find his long-missing older brother (Vincent Gallo), a once-promising writer who is now a remnant of his former self. Bennie's discovery of his brother's near-finished play might hold the answer to understanding their shared past and renewing their bond. Written and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Starring: Vincent Gallo, Alden Ehrenreich, Maribel Verdu, Rodrigo De la Serna, Leticia Bredice, Mike Amigorena, Klaus Maria Brandauer and Sofia Gala Castiglione.

#alden ehrenreich#vincent gallo#maribel verdu#rodrigo de la serna#leticia bredice#mike amigorena#klaus maria brandaver#sofia gala castiglione#francis ford coppola#tetro#babyjujubee#adoring alden ehrenreich#tumblr#video#google#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes