#Margot Wallström

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In January 2020, Mexico made history as the first Latin American country to adopt a feminist foreign policy. Pioneered by Sweden six years earlier in 2014, feminist foreign policy (FFP) initially began as a niche effort in the Nordic region. For many years, Sweden stood alone on the global stage, emphasizing that its FFP focused on enhancing women’s “rights, resources, and representation” in the country’s diplomatic and development efforts worldwide. That effort was the result of the vision and leadership of Sweden’s foreign minister at the time, Margot Wallström, although there was widespread support for the policy across the government and it was continued by subsequent ministers.

It would be another three years before other nations followed suit: In 2017, Canada announced a Feminist International Assistance Policy. At the end of 2018, Luxembourg’s new coalition government committed to developing a FFP in their coalition agreement. And in 2019, Mexico and France pledged to co-host a major women’s rights anniversary conference in 2021 while beginning to explore the development of feminist foreign policies simultaneously.

I had an inside view on that process having convened the existing FFP governments and numerous international experts just before Mexico’s announcement. Together, we developed a global definition and framework for FFP. As I wrote for this magazine in January 2020, this approach was largely followed by the Mexican policy. The goals for Mexico in adopting an FFP were to increase the rights of women and LGBTQ+ individuals on the world stage, diversify their diplomatic corps, boost resourcing for gender equality issues, and ensure that internal policies within the foreign ministry aligned with this approach, including a zero-tolerance policy toward gender-based harassment.

Now, under the leadership of a new female foreign minister, Alicia Bárcena, and following the election of Mexico’s first woman president, Claudia Sheinbaum, I was excited to travel to Mexico City in July as it hit another milestone: becoming the first country outside Europe to host the annual ministerial-level conference on FFP. It was an opportunity for me to take stock of what Mexico has achieved since it adopted an FFP, and to see what progress it has made toward its goals.

Initially convened by Germany’s Annalena Baerbock in 2022 and then by the Dutch last year, Mexico took a unique approach to the conference by focusing it on a specific policy issue—in this case, the forthcoming Summit of the Future. This conference, taking place at the U.N. General Assembly in September, aims to begin laying the groundwork for the successor goals to the Sustainable Development Goals framework. It is already a fraught and polarized process, and progressive leadership is sorely needed.

Last week provided clear evidence that Mexico is making progress in modeling that leadership—including in consistently advocating for progressive language in often contentious international multilateral negotiations, such as the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP). For example, in its interventions at the latest COP, Mexico placed human rights, intersectionality and gender equity at the heart of climate action and recognized the role of women environmental defenders and Indigenous women in a just transition.

“Mexico is often a lone voice in holding the line on critical human rights, Indigenous rights and gender equality language at the climate talks, even among the FFP countries,” said Bridget Burns, the executive director of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization who has spent the last 15 years organizing women’s rights activists in climate negotiations and attended the July conference to speak on the sustainable development panel.

Mexico’s decision to link their hosting of the FFP Conference to the Summit of the Future—as evidenced in an outcome document they published and are circulating for signature ahead of the General Assembly’s high-level week in September—challenged FFP governments to engage a feminist approach in mainstream foreign policy dialogue, not just in gender-related discussions like the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women. “The Summit of the Future aspires to a better tomorrow, but lofty goals won’t translate to real systemic change without feminist civil society,” said Sehnaz Kiymaz, senior coordinator of the Women’s Major Group.

On the multilateral front, Mexico has shown leadership by co-chairing the Feminist Foreign Policy Plus Group (FFP+) at the UN, alongside Spain. This body held the first ministerial-level meeting on FFP at the General Assembly last year and adopted the world’s first political declaration on FFP. Signed by 18 countries, governments pledged “to take feminist, intersectional and gender-transformative approaches to our foreign policies,” and outlined six areas for action in this regard. This was the first time FFP countries publicly pledged to work together as a group to address pressing global challenges through a feminist approach. While smaller subsets of this cohort have worked together multilaterally to condemn women’s rights rollbacks in Afghanistan or in support of an international legal framework on the right to care and be cared for, the first big test of this more systematic approach will be the forthcoming Summit of the Future, where feminists have been advocating for gender to be referenced as a cross-cutting priority.

Mexico has also recently ratified two international instruments to directly benefit women: Convention 189 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) on domestic workers and Convention 190 of the ILO on violence and harassment in the workplace. Under the mantle of its FFP, Mexico has championed the importance of care work in the advancement of women’s rights and countries’ development at the U.N. Human Rights Council and at the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean through the Global Alliance for Care Work.

While international women’s rights activists at the conference largely gave positive feedback on Mexico’s track record, the response from Mexican civil society was more critical. Activists organized a side event to present their more skeptical view of Mexican FFP. María Paulina Rivera Chávez, a member of the Mexican coalition and an organizer of the event, argued a conference could only go so far. “It is fundamental to decenter the state, understanding that feminist foreign policies must be horizontal,” she said.

A major theme of that side event and of Mexican activists’ interventions in the official ministerial conference was the incongruence of the Mexican government’s leadership on feminist approaches internationally while women’s human rights at home have suffered. Such criticisms of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador government are not unfounded. In one particularly troubling interview a few years ago, he suggested that Mexico’s high rate of femicide—11 women are murdered daily, with rates on the rise compared to other crimes—was merely a false provocation by his political opponents. Negative biases against women are pervasive in Mexico, with 90 percent of the population holding such biases.

Mexico has made strides in improving gender equality in other areas, however. Women now make up half of the Mexican legislature and have been appointed to lead high-level institutions, such as the Supreme Court, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Central Bank, with cascading positive effects on gender equality. Bárcena, for instance, clearly asserted from her first speech on the job that Mexico’s FFP would remain a top priority. This is no accident. At the federal level, significant efforts have been made to enforce gender parity laws and implement more than 80 percent of the legal frameworks promoting, enforcing and monitoring gender equality as stipulated by international benchmarks. Mexican women have also seen some improvements in maternal mortality rates, access to internet services, and protections to the right to abortion, with numerous national commitments to improve gender equality, such as measures to alleviate the burden of care on women.

But while there has been an increase in the number of women in the legislature and government positions, women from Indigenous, Afro-descendent, and working-class backgrounds continue to be underrepresented in political roles. And there has been a steady increase over the last decade in femicides, disappearances and sexual violence which Mexican feminist organizations and international actors have found are directly linked to the militarization of law enforcement under the guise of Mexico’s war on drugs and organized crime.

Additional criticisms of the Mexican FFP itself include the foreign ministry’s insularity and reluctance to engage with Mexican feminist activists in the development and implementation of its FFP. There was also a hesitation by the previous foreign ministry leadership to collaborate with Inmujeres, Mexico’s gender ministry, preferring to keep control of the FFP within the foreign ministry alone. It is not uncommon for gender ministries to be excluded in foreign policymaking as they are often perceived as lacking the necessary expertise or authority on foreign policy. However, Inmujeres is an exception in this regard and the criticism was valid. This was on my mind as I participated in the conference last month, and straight out of the gate I could observe a clear departure from the past approach under Bárcena’s leadership: The foreign ministry officially partnered with Inmujeres to co-host the conference, and the heads of both agencies were equally prominent voices throughout the three-day event. Similarly, the foreign ministry also made efforts to engage Mexican feminist civil society in conference planning, inviting civil society to a consultation day in the weeks leading up to the conference.

Following the right-wing electoral successes and likely abandonment of FFP in countries like Sweden, Argentina, and potentially the Netherlands, the success of a Mexican model of FFP is all the more important. Mexican activists I spoke with expressed optimism about Bárcena’s leadership, which they had not extended to her predecessor. Certainly, there is some cynicism about whether Mexico’s next president, a woman, will be any better on the issue of femicide than her mentor and predecessor, López Obrador, but there is some room for hope. If the leadership of a female foreign minister like Bárcena has been more effective in mobilizing political and convening power behind FFP, there’s potential that Sheinbaum will also show more interest than her predecessor.

While Mexican civil society has critiqued that Sheinbaum did not present a plan on how she would continue and improve the country’s FFP and repair the government’s relationship with feminist civil society, Sheinbaum’s plan—entitled 100 Pasos Para La Transformación—takes a human rights-based approach to gender equality. This is promising, because political approaches, which are more common, tend to reduce the human rights of women, girls, and gender-diverse persons as a means to an end, such as better economic, education, or health outcomes. The plan proposes measures to alleviate the care burden on women, safeguard sexual and reproductive health and rights, protect LGBTQ+ communities, promote gender parity in cabinets, improve land rights for rural women, reduce femicides, and more.

That Sheinbaum has not explicitly addressed the importance of Mexico’s FFP is not necessarily surprising. Most feminist and women’s rights organizations are understandably more focused on issues within their own borders, and foreign policy rarely drives political power and the focus of the electorate. Discussion of feminist foreign policy is thus typically the domain of the foreign minister and in some cases other relevant ministers—such as international development in Germany, or the trade ministry in Sweden under its previous government. (Canada’s Justin Trudeau stands out as a rare exception, having championed feminism and Canada’s feminist approach to policymaking at the Group of Seven and international gender equality forums throughout his tenure as prime minister.)

But even without top-down leadership from a president, savvy officials within the Mexican foreign and gender ministries are using FFP to make progress. While there has not yet been a public accounting of the progress made in implementing FFP, the clear leadership Mexico is demonstrating on the world stage in key negotiations, its successful conference, and the anticipated new government set the stage for Mexico to boldly advance its FFP. It will serve as a valuable example to the world.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greta Thunberg's visit to Ukraine reminds us that Putin's invasion is an act of ecocide. The Russian destruction of the dam at Kakhovka is just one of many Russian war crimes with harmful effects on the environment.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy met Thursday with Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg and prominent European figures who are forming a working group to address ecological damage from the 16-month-old Russian invasion. The meeting in the Ukrainian capital came as fighting continued around the country. [ ... ] The working group on the environment includes Thunberg, former Swedish Deputy Prime Minister Margot Wallström, European Parliament Vice President Heidi Hautala, and former Irish President Mary Robinson. Zelenskyy said forming the group is “a very important signal of supporting Ukraine. It’s really important, we need your professional help.” Thunberg said Russian forces “are deliberately targeting the environment and people’s livelihoods and homes. And therefore also destroying lives. Because this is after all a matter of people.” The objectives of the working group are evaluating the environmental damage resulting from the war, formulating mechanisms to hold Russia accountable, and undertaking efforts to restore Ukraine’s ecology.

Assessing the environmental impacts of the war in Ukraine

Every environmental disaster caused during this war is the direct responsibility of Vladimir Putin and Russia. Putin's efforts to become the Peter the Great of the 21st century set off a string of ecological catastrophes which actually began by compounding a previous Russian environmental calamity at Chernobyl.

#invasion of ukraine#ecocide#the environment#environmental catastrophe#ukraine#kyiv#greta thunberg#volodymyr zelenskyy#nova kakhovka#kakhovka dam#chernobyl#ecovandalism#russia#russian war crimes#екоцид#россия#владимир путин#путин хуйло#военные преступления#путин – это лжедмитрий iv а не пётр великий#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#каховська гідроелектростанція#грета тунберг#навколишнє середовище#володимир зеленський#слава україні!#героям слава!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margot Wallström

Le società con parità di genere godono di migliore salute, una più forte crescita economica e maggiore sicurezza, oltre a contribuire alla pace.

Si parte dal principio delle tre R: rights, representation e resources, diritti, rappresentazione e risorse.

Per “diritti” si intende il promuovere e affrontare le principali emergenze in materia di parità di genere, come la discriminazione e la violenza sulle donne. Con la seconda R, quella della “rappresentazione”, si punta a garantire la presenza delle donne nei ruoli decisionali, sia pubblici che privati. Infine, con “risorse” si intende la possibilità di distribuire equamente fondi e, appunto, risorse tra uomini e donne.

Margot Wallström è stata Ministra degli Affari Esteri della Svezia dal 2014 al 2019.

Appartenente al Partito Socialdemocratico, ha avuto una lunga carriera nel parlamento svedese e nella Commissione Europea apportando significativi contributi per la tutela dell’ambiente e i diritti delle donne.

È stata la prima rappresentante speciale delle Nazioni Unite sulla violenza sessuale nei conflitti dal 2010 al 2012, Vicepresidente della Commissione europea, Commissaria per le relazioni istituzionali e la strategia di comunicazione, Commissaria europea per l’ambiente e Ministra per la tutela dei consumatori, donne e gioventù.

È stata la prima ministra degli esteri di un paese dell’Unione Europea a voler riconoscere la Palestina come Stato.

Nata a Skellefteå, il 28 settembre 1954, è scesa in politica a soli diciannove anni, a venticinque era già stata eletta al Parlamento.

Nel 2006 è stata votata come la donna più popolare in Svezia, battendo reali e atleti.

L’anno seguente ha presieduto il Consiglio delle donne leader mondiali.

Nel 2009, sempre al Parlamento Europeo, nella commissione guidata da José Barroso è stata vice presidente e responsabile delle Relazioni Istituzionali.

Nel 2014 è diventata ministra degli Affari Esteri nel governo svedese di Löfven I promettendo una politica femminista.

Durante il suo mandato è riuscita a inimicarsi l’Arabia Saudita criticando la mancanza dei diritti delle donne nel paese e minacciando di revocare l’accordo di esportazione di armi. L’incidente diplomatico è stato appianato dal re di Svezia in persona.

Successivamente si è schierata contro le politiche israeliane nei confronti della popolazione palestinese ed è stata dichiarata antisemita e non gradita nello stato di Israele.

Ha contestato anche le politiche turche rispetto al sesso tra minori e per l’accanimento contro la popolazione curda.

Come ministra degli esteri non si è certo distinta per la sua diplomazia, anche se ha dovuto arretrare su alcune dichiarazioni per mantenere il suo ruolo istituzionale.

Nel 2015 ha fatto parte del Comitato per il finanziamento umanitario dell’ONU, in preparazione del World Humanitarian Summit.

Margot Wallström è una donna che non si è fatta spaventare da niente e da nessuno.

Per prima ha aperto un blog al Parlamento Europeo, un luogo aperto dove confrontarsi su temi politici.

È stata insignita con numerosi premi, ha ricevuto diverse lauree ad honorem ed è presidente del Consiglio dell’Università di Lund.

Attualmente è nel direttivo di diverse no profit per la tutela dei diritti umani, di genere e ambientali.

0 notes

Text

Today's P4 Extra guest is Margot Wallström.For the past six months, she has been leading an international group that will look at the environmental consequences of Russia's large-s...

0 notes

Photo

Medienkritik aus der Welt von Vorgestern (2.3): Baerbock startet die Ära der feministischen Außenpolitik, aber ohne Margot Wallström auf der Titelseite auch nur zu erwähnen. Wallström prägte in Schweden ab 2014 den Begriff der Feministisk utrikespolitik. #witchhunt

0 notes

Text

jonas gardell ger sig in i diskussionen med sina sedvanligt väl underbyggda argument (ignorerar alla motargument, insinuerar margot wallström är en högerextremeist á la uganda/ungern/ghana)

när jan guillou skriver att han håller med hanne kjöller vet man att det är något extremt på gång

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

https://kurdnet.tumblr.com/

1 note

·

View note

Text

UAE Reiterates Commitment To Somalia's Unity, Security And Stability

UAE Reiterates Commitment To Somalia’s Unity, Security And Stability

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Eritrea#Ethiopia#EU and Luxembourg#European Union#Federal Government of Somalia#Federica Mogherini#Horn of Afric#International Community#Margot Wallström#Mohammed Issa Al Suwaidi#Political Roadmap 2020#Reiterates Commitment#restore peace and stability#Security And Stability#Somalia#Somalia Partnership Forum#Somalia&039;s Unity#UAE Ambassador to the Kingdom of Belgium#United Arab Emirates (UAE)#Unity

1 note

·

View note

Quote

"The oppression of women is a global disease." – Margot Wallström

UN Women (https://twitter.com/UN_Women/status/923938658905939974)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh thanks!

This is where people are watching for the proposition to come:https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/arende/betankande/forbattrade-mojligheter-att-andra-kon_HA01SoU25

there's a SoU about trans from like 2014 that the activists use to push new law. so its gone back and forth for a bit.

Lagrådsremiss was a year and a half ago i recommend you read the responses from the different remissinstanser, its a good way to see what different organisations had to say (or if you want to join an oeganisation with women that agree with u). This is when the proposal was full self-id and from 12 years of age. The more recent one that came after this was from 16, and not full self-id, you'd need some sort of assessment. so what we're waiting on is to see what the final proposition will be. Anyway the responses from 2021 are here: https://www.regeringen.se/remisser/2021/11/remiss-utkast-till-lagradsremiss-vissa-kirurgiska-ingrepp-i-konsorganen-och-andring-av-det-kon-som-framgar-av-folkbokforingen/

the parties on the left all have pro-self id things in their partiprogram. miljöpartiet are especially loud, S are a bit quiet because S-kvinnor are critical of self-id, Margot Wallström got some shit for speaking out a while back. You can look at Womens rights watch valkompass too:

View this post on Instagram

so atm politically i think people are waiting on the actual proposition and also seeing how this plays out in the parties on the right. we desperately need more left-wing ppl to speak out.

(also DM me if you want to chat! depending on where u live i might b able to connect you to local women or chat about feminist organisations)

(this is a rant based on a conversation i had yesterday, i wanted to write it down as a time capsule/diary entry type thing about where The Debate is right now. links are to stuff in swedish)

right now im super apprehensive about how the self-id/single sex spaces discussion is gonna go in sweden. a major difference between sweden and the uk is we have established women’s orgs on our side, high ups in the womens shelter movement are speaking out etc.

and im seeing how that can go in 2 different directions. as an example, recently there’s been articles and awareness about the situation for young women/teen girls in institutional care. amongst other things, sexual assault by male staff is an issue. the board says they want to fix it by “hiring more women”. the main organisation of women’s shelters wants demands single-sex staff, so males don’t get access to vulnerable girls.

at the same time, we have the self-id/trans debate bubbling up. this month there’s been a handful of articles and debate on the issue, but we’re waiting on the government to announce their (overdue) proposition. (So we don’t know right now if it’s full self-id or not! if i remember it correctly the most recent proposal from last year disappointed basically everyone by having all the gender-id language but wasn’t full self-id because it needed some “simplified process of confirmation”, so the self-id advocates were mad about it)

which brings me to what this post is actually about: the fork in the road where we’re at. there’s so much polarisation and so many questions that the right/nationalist side owns already, like how the drag queen story hour thing is only ever presented as a “liberal gays” vs “straight nationalist conservatives and alt righters” issue. right now, at this point in time, the media is actually talking about single sex spaces as “trans advocates” vs “(some) women’s organisations”. and that’s an important advantage imo. one that we don’t want to lose.

re: the example about the institutionalised girls: there are two ways this could go. one way is that people understand that the women’s orgs are right to demand single-sex services for vulnerable girls and women.

the other way this could go is trans activists shouting about how women aren’t actually demanding single-sex care because the girls are vulnerable, they’re just using it to be mean about trans women. and they’ll use the fact that various women’s orgs collaborate on articles to undermine them. (look, these womens orgs that we thought were reasonable work with the really terfy ones!)

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2014, Margot Wallström, then serving as the foreign minister of Sweden, proclaimed that the Swedish government would adopt a so-called feminist foreign policy, becoming the first nation ever to do so. Since then, Canada, France, and Mexico have followed suit, and a handful of other nations—most recently, Luxembourg, Malaysia, and Spain—have pledged to develop similar policies.

In each of these countries, the announcements have provoked questions among foreign policy experts. What, exactly, do these policies set out to achieve? At a time of rising global activism for gender equality, what does it mean to conduct foreign policy from a feminist perspective? And in an era of economic uncertainty, is a focus on gender equality an unnecessary distraction?

A Natural Fit

Evidence from recent studies suggests that the status of women is closely aligned with a country’s prosperity and security. In this respect, promoting gender equality as a foreign policy priority seems like common sense. Closing the gender gap in workforce participation could add as much as $28 trillion to the global GDP. Ensuring women’s meaningful participation in peace processes makes agreements more likely to last and be implemented. The more women there are in a country’s parliament, the lower the incidence of human rights abuses and conflict relapse. Equalizing access to agricultural resources for women could result in 150 million fewer hungry people on the planet. The bottom line: research confirms that nations seeking to fortify their own security, better use foreign aid, or support stable and democratic partners should prioritize women’s advancement.

Women’s rights have had a place in public policymaking since at least the late 1970s, supported by both international institutions and a proliferation of local ones in more than 100 countries. But national reforms have primarily addressed domestic concerns. A feminist foreign policy offers something different, in that it promotes programs that make gender equality and women’s empowerment central to national security, including diplomacy, defense, aid, and trade.

The government of Sweden has undertaken the most comprehensive plan of this type with the feminist foreign policy it first articulated in 2014. But the Swedish policy actually builds on the prior efforts of many other nations. Such efforts share a focus on promulgating change in three broad areas. They seek to promote women’s leadership, to commit to policies that advance equality, and to allocate resources in a manner that supports those commitments. The specific initiatives governments have proposed vary, as do the extent of their implementation and the means of measuring their success. And although all aim to elevate gender equality as a foreign policy priority, not all are explicitly termed “feminist.”

Over the last decade, many countries have brought more women into their foreign policy decision-making circles and placed greater emphasis on gender equality in their conduct of foreign affairs. Today, a record 34 countries have female foreign ministers, 84 have female ministers of trade, and 20 have female ministers of defense. Several countries have established ambassador-level positions to promote women’s issues abroad or within their foreign policy apparatus. Not all of these countries have signed on to a foreign policy unequivocally dedicated to advancing women’s rights, but the shifts in their leadership have diversified foreign policy debates and led to effective policies.

Countries with and without explicitly feminist foreign policy agendas have pursued policies and dedicated resources that further gender equality, some of them adopting specific plans to address women’s rights through diplomacy and development cooperation. Eighty-three nations have adopted national action plans to encourage women’s participation in peace and security processes. Donor countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United Arab Emirates, have pledged a percentage of their foreign-assistance funds to programs that promote the advancement of women, or they have created new pooled funds to support women’s rights organizations. These efforts add up to a collective shift in resources and political will.

Too Much, Too Little

The effort to change leadership, adopt policies, and commit resources in order to advance gender equality as a foreign policy priority has met with some skepticism. Critics argue that increasing the focus on women’s rights and gender equality detracts from promoting other national interests abroad. Even many who believe that gender equality is a worthwhile goal do not agree that it should be institutionalized as a foreign policy priority.

Such criticism overlooks evidence that gender equality is not only a human right worthy of protection but also a means to advance a country’s economic and security interests. Raising the status of women and girls has been shown to increase GDP, improve global health, combat radicalization and extremism, improve the chances of lasting peace, and strengthen democracy. The world confronts too much poverty, insecurity, authoritarianism, and violence for any nation to afford to overlook the talents and contributions of 50 percent of its population.

Other skeptics argue that a true feminist foreign policy would require nothing short of a transformation in international relations. These critics maintain that the feminist policies that the governments of Canada, France, Sweden, and other countries have adopted do not do enough to reshape aid infrastructure, decrease militarism, address the root causes of inequality, or incorporate the experiences of women and girls. But to the extent that such critiques are valid, they risk making the perfect the enemy of the good. Moreover, policies promoting gender equality in the national security space are relatively new, and it is still too early to know just what effects they will have, whether on improving the lives of women or on generating the political will to bring about further change.

Theory Into Practice

A foreign policy vision that announces itself as feminist has the advantage of making gender equality an implicit and explicit priority. But Sweden’s path is not the only way forward. By adopting and executing a carefully designed policy that ties women’s advancement to national security, as well as to economic and diplomatic priorities around the world, countries can hope to reap some of the benefits of greater parity.

To strengthen prosperity and stability, governments worldwide—including the United States—should work to advance gender equality in foreign policy. Governments should establish high-level councils to coordinate their efforts to promote the status of women and girls both at home and abroad. Each cabinet agency should appoint a high-ranking, full-time official who reports directly to the cabinet minister and is tasked with fostering gender equality. And governments and their agencies should make their own workplaces a part of this effort by prioritizing gender balance in staffing and providing effective means for addressing workplace harassment and abuse.

National leaders should draw up government-wide, high-priority policies to advance gender equality through diplomacy, development, defense, and trade. Metrics for measuring a country’s prosperity and stability should take into account the status of women and girls—by, for example, defining economic health to include a level playing field for women, free of discriminatory laws, and defining security to include freedom from intimate-partner violence and sexual assault. Parliaments can support these policy efforts with legislation that promotes gender equality and mandates government ministries to strengthen related initiatives.

Gender equality promises real benefits, not only to a country’s economy but also to its national security. In order to reap those benefits, however, governments need to invest, and they must do so at levels sufficient for achieving meaningful gains for women. Countries that can provide foreign assistance should do so in a manner that directly supports local, female-led organizations, which are proven drivers of change but often lack funds. A multinational gender-equality partnership, modeled after the Open Government Partnership, could catalyze additional financing for gender equality from governments, multilateral organizations, the private sector, and civil society institutions.

Rhetoric and promises alone will not generate the dividends of real progress toward gender equality. Nations should be held accountable for the work they do (and don’t do). They should commit to issuing public annual reports that assess progress toward time-bound and measurable goals along the road to equity. For its part, the United States should ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which would oblige it to join other nations in submitting a report to the CEDAW committee every four years detailing measures taken to advance gender equality.

Feminist foreign policy aims to unlock the potential of half the population. Doing so is not just a moral obligation—it is an economic and security imperative. To get there, countries must demonstrate genuine leadership, adopt strong policies, and provide generous resourcing that will not only improve the lives of women and girls but also strengthen the stability and prosperity of entire economies and nations.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Swedish foreign ministry has many reasons to follow events in northern Syria. One of them is the Swedish children and women who are held in various Kurd-controlled camps for relatives of suspected ISIS-terrorists. In April this year, the foreign minister at the time, Margot Wallström, announced that the children would be allowed to come home. But so far only seven children have been brought to Sweden.

-- We want to bring the children home. But it’s much, much harder than we thought. First, there are certain laws which mean that you can’t simply take a child from its mother, or take a child who has a Swedish mother and a non-Swedish father. Second, there is human rights and international law. There are so many obstacles which I think we were not aware of in the beginning, says Ann Linde.

Those pesky human rights causing trouble again...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

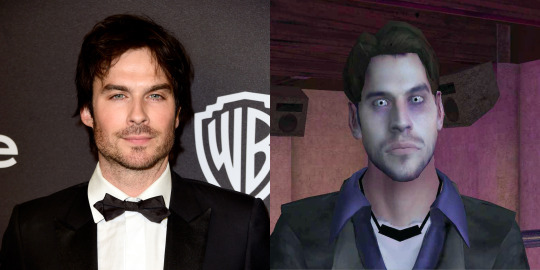

VTMB fancast

Martin Wallström - Sebastian Lacroix

Gong Li - Ming Xiao

or Luci Liu - Ming Xiao

Johny Depp - Beckett

Margot Robbie - Therese Voerman

Margot Robbie - Jeanette Voerman

Michael Pitt - Vandal Cleaver

Or Brady Corber - Vandal Cleaver (Vandal never enough xD)

Luke Wilson - Mercurio

Willem Dafoe (in Nosferatu-2000) - Gary Golden

Jeremy John Irons - Isaac Abrams

Kat Dennings - Velvet Velour

or Сhristina Hendricks - Velvet Velour (I would suggest Dita von Teese, but no)

Ian Somerhalder - Ash Rivers (I mean, just look at their moustaches)

David Gandy - Nines Rodriguez (lol)

Shirley Manson - Damsel

Ivanno Jeremiah - Skelter

Rob Zombie - Smiling Jack

Lindsey Morgan - Pisha

Ed Harris - Maximillian Straus

Laura Spencer - Heather Poe

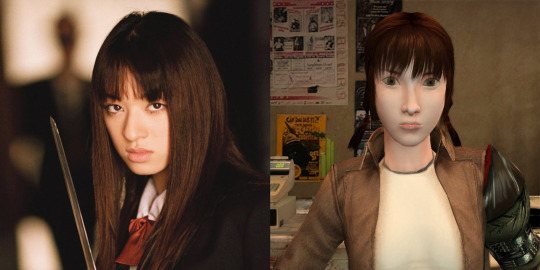

Chiaki Kuriyama - Ogami Yukie

Katy Perry - Venus Dare

Gordon Liu - Mr. Ox

Jackson Rathbone - Trip

Olivia Cooke - Samantha

Iwan Rheon - Bishop Vick

Joseph Gatt - Brother Kanker

Melanie Gaydos - Imalia

Yuriy Kolokolnikov - Barabus

Kimberly Freeman - female Malkavian protagonist

Natalia Tena - female Gangrel protagonist

Linda Evangelista - female Toreador protagonist

#vtmb#vampire the masquerade#vampirethemasquerade#Vampire The Masquerade Bloodlines#втмб#gary golden#sebastian lacroix#beckett#jeanette voerman#therese voerman#vandal cleaver#isaac abrams#ash rivers#heather poe#ogami yukie#max straus#smiling jack#pisha#damsel#skelter#Nines rodriguez#velvet velour#mercurio#mingxiao#venus dare#fancast

266 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What a wonderful compliment. I think its fair to say that we all love Alex. <3

Alex with Patti Smith, Margot Wallström (Sweden’s Minister for Foreign Affairs) and friends at the 2018 Way Out West Festival (August 9, 2018, Göteborg, Sweden).

Margot had a chat with Alex and had very kind words to say about meeting him:

“This is an actor and representative of Sweden that contributes to the image of Sweden. It’s fun that such people show such humility, professionalism and are so nice and down to earth. I think he’s amazingly good. A great representative of Sweden that we can be proud of. It was also a nice experience.” (Source: Aftonbladet.se (x))

Photo sources/Thanks: TeamWallstrom instagram (x, x) & August 9, 2018 insta stories (x), Aftonbladet.se (x) & Stockss’ August 10, 2018 insta story (x, x)

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyckleri och svek när Sverige bytte sida om kärnvapen

Hyckleri och svek när Sverige bytte sida om kärnvapen

0 notes

Text

Swedish FM Wallström Says She Won't 'Forgive' UK Lawmakers For Allowing Brexit

Swedish FM Wallström Says She Won’t ‘Forgive’ UK Lawmakers For Allowing Brexit

Swedish Foreign Minister Margot Wallström slammed UK politicians for Brexit, saying she cannot “forgive” them for allowing the British people to vote to leave the European Union. Wallström made her comments this week during a conference on foreign policy in the Finnish capital of Helsinki saying that the British political class had created a problem not just for the UK but for countries across…

View On WordPress

0 notes