#Margaret Stewart Dauphine of France

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

✧ The neglected Margaret of Scotland, Dauphine of France tried to centre her thoughts upon her own interests. She loved poetry above all things and gathered round her several women who occupied themselves with literary composition. (…) Alas, the French Court lacked the simplicity and purity which ought ever to surround a woman of Margaret's idealistic nature. Her love of the beautiful and unusual was to lead her into difficulties and suffering. She liked to sit evening after evening with the young courtiers and her maidens, reciting verse and singing love-songs, trying to keep out of her life the sordid ambitions and ugly intrigue which played a large part in the doings of others, and to bring into it some of the artistic atmosphere and culture she found congenial. – The Dauphines of France by Frank Hamel

#historyedit#p: margaret dauphine of france#margaret of scotland#margaret dauphine of france#margaret of scotland dauphine of france#margaret stewart#scottish history#french history#princesses#medieval history#15th century#house of stewart#kingdom of scotland#gifs#ours

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 17th 1424 French and Scots troops suffered defeat at the Battle of Verneuil.

Scots have a long history with France, the first official alliance dates back to the start of The First War of Scottish Independence

First agreed in 1295/6 the Auld Alliance was built on Scotland and France’s shared need to curtail English expansion. Primarily it was a military and diplomatic alliance but for most of the population it brought tangible benefits through pay as mercenaries in France’s armies and the pick of finest French wines.

In the poet William Dunbar’s, poem “Dirige to the King” he extols to James IV the selections of those wines….

‘To drink withe ws the new fresche wyne That grew apone the revar Ryne, Fresche fragrant claretis out of France, Off Angeo and of Orliance,’

Shakespeare’s ‘Henry V’ rightly portrays the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 as one of England’s greatest military victories. For the French it was a disaster that led to the near collapse of their kingdom. In their darkest hour the Dauphin turned to the Scots, England’s enemy, for salvation. Between 1419 and 1424, 15,000 Scots left from the River Clyde to fight in France. In 1421 at the Battle of Bauge the Scots dealt a crushing defeat to the English and slew the Duke of Clarence.

Honours and rewards were heaped upon the Scots army by the French. The Earl of Douglas was given the royal Dukedom of Touraine and the Scots army lived well off the land, much to the chagrin of the French peasantry. Their victory was short lived however; at Vernuil in 1424 a Scots army of 4,000 men was annihilated. As mercenaries they could have expected no mercy and those who were captured were dispatched on the spot. Despite their defeat, the Scots had brought France valuable breathing space and effectively saved the country from English domination.

Many Scots continued to serve in France. They aided Joan of Arc in her famous relief of Orleans and many went on to form the Garde Écossais, the fiercely loyal bodyguard of the French Kings, where they were at the very heart of French politics. And of course our Monarchs daughters married into the Royal Family of France, most notably, Margaret Stewart, from yesterday’s post and the most famous of all Mary Queen of Scots.

Many Scots mercenaries settled in France although they continued to think of themselves as Scots. One such man was Beraud Stuart of Aubigny: a third-generation Scot immigrant, Captain of the Garde Écossais from 1493-1508, and hero of France’s Italian wars. To this day both he and other Scots heroes of the Auld Alliance are celebrated in Beraud’s home town of Aubigny-sur-Neve in an annual pageant.

Of the battle itself it was later described as a ‘second Agincourt’ and Scotland’s future military prospects were damaged by the deaths in battle of two leaders - the Earl of Douglas and the Earl of Buchan. The defeat saw an end to Scotland’s participation as a nation in the Hundred Years’ War, although individual mercenaries stayed on to fight alongside the French.

This was a particularly brutal battle, Scots were slaughtered rather than being taken prisoner after the English had won the battle. The French had not adhered to the rules of the battle, chivalry was a big thing in those days, added to that Scotland was meant to be at peace with England at this time and this annoyed the English, a truce between England and Scotland had come into effect on the 1st May (I believe) which meant that the Scots would no longer fight with the French- but there was a loophole allowing Scottish forces already in France to stay. The English were offended at the Scottish presence. It seems that the English side and the Scottish forces, arrayed before the battle, hurled challenges, presumably with insults, at each other: this was to be a fight to the death, and the Scottish- oath breakers- did not deserve proper chivalric protocol. No quarter was given those Scots attempting to surrender were cut down and virtually the entire Scots force falling on the battlefield. The Scots stood their ground and died where they fought. A contemporary account said this of the aftermath…..

“… there a horrible spectacle to see on the battlefield, the corpses in high, tightly packed heaps, especially where the Scots had fought. No prisoners were taken among them, and the heaps held the bodies of the dead English soldiers all mixed up with theirs.” (Thomas Basin, Bishop of Lisieux):

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margaret Stewart (25 December 1424 – 16 August 1445) was a princess of Scotland and the dauphine of France. She was the firstborn child of King James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort.

She married the eldest son of the king of France, Louis, Dauphin of France, at the age of eleven. Their marriage was unhappy, and she died childless at the age of 20, apparently of a fever.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

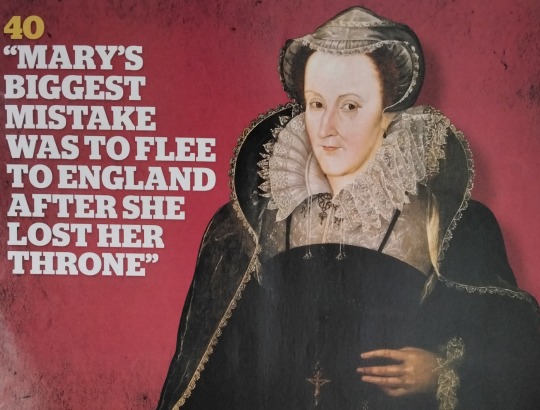

Notes from BBC History magazine (January 2019 edition):

Mary had the misfortune to ascend the Scottish throne at the very moment when the kings of England and France were eyeing her nation greedily - seeing in it an opportunity to extend their own power. And so, from the moment she was born, Mary was exploited by two powerful Kings- and her own family.

She was proclaimed queen at just six days old, on the death of her father, King James V. Immediately, Henry VIII declared his intention for Mary to marry his son, Edward, but as this was a means of gaining control over Scotland, the prospect was unpalatable to Mary's mother, Mary of Guise, who was acting as queen regent. So, Mary was packed off to France to be brought up as the future wife of the dauphin, Francis, son of the French king, Henry II. Meanwhile, the Guise family hoped that, through Mary, they would attain more influence at the French court.

The French king, Henry II, planned to absorb Scotland into France and even encouraged Mary to proclaim that she and her husband were the monarchs of England, which infuriated Elizabeth I and was to have fateful consequences. However, his plans fell apart when Francis died, aged 16, in 1560. Now a widow, she was unwanted at the French court and so she returned to Scotland. But unlike Elizabeth, who had grown up on the outskirts of her country's court and developed a firm group of loyal men around her, Mary returned to be a queen of a country she had not seen since she was five. [How fluent was her English?] [ Also note that Scotland at the time was riven by warring clans and factions, it would have been difficult for anyone to bring them all peacefully together].

Acc. to the article, Mary had been advised to return to Scotland by her half-brother, James Stewart, Earl of Moray, who had accompanied her to France when she was a child (he was around 11 years her senior) and who appeared to be her greatest supporter. His motives, however, were dubious. He wanted power for himself, but his claim to the throne was weak due to him being born illegitimate (his mother was Lady Margaret Erskine, mistress to James V of Scotland). To cut a longer story short, Moray took Mary captive, locked her in Lochleven Castle and forced her to abdicate. She was able to escape and fled to England, while Moray took up the regency for her son, James, until he was shot in 1570.

The article is by Kate Williams, a historian I've seen on TV a few times and I'm not very keen on. I think she's the one who fauns over the modern day royals a lot. It's interesting that she doesn't mention any possibility of Mary being implicated in the murder of Darnley; she also states that Mary was raped by the man who was to become her third husband, Bothwell, whereas I was of the understanding that while this has been suggested there is no evidence of Mary having made an accusation or informing anyone that he committed such a crime against her. But Williams writes it as though it is pure fact. I will have to dig out my book my Jenny Wormald and see what she thought.

It is Williams' view that Mary's biggest mistake was to flee to England after she lost her throne. She was convinced that her cousin Elizabeth I would help her, but that support never materialised. She was locked up, spending most of her imprisonment in Sheffield Castle and Sheffield Manor with no prospect of release, which is what prompted her involvement in the 'Babington Plot', the plan to assassinate the English queen. It was this betrayal which finally led Elizabeth to sanction Mary's execution at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, at the time a state prison, in 1587. She was only 44. She had spent nearly half of her life in captivity.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Edits: Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France

Born Christmas 1424, Margaret Stewart was the eldest child of James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort, and older sister to Isabella, Duchess of Brittany; Joan Countess of Morton; James II, King of Scots; Eleanor, Archduchess of Austria; Mary, Lady of Veere and Countess of Buchan; and Annabella, Countess of Geneva/Huntly. Though her father’s reign was turbulent- ending in his murder in 1437- what little is known of Margaret’s childhood indicates that it was relatively happy, though at the age of 11 she was to leave Scotland, never to return. Having taken a tearful farewell of her father, she sailed from Dumbarton in March 1436, bound for France, where she was to marry the heir of King Charles VII.

Married Louis, Dauphin of Viennois- the future Louis XI of France- in Tours on 25th June 1436. Though her relationship with her husband was reputedly bad and the two were generally estranged, she was a beloved daughter-in-law of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou, and generally popular at court, both for her personality and beauty. Famous for her love of poetry, she spent many sleepless nights composing ballades until dawn, and allegedly sometimes wrote as many as twelve a day. The literary atmosphere of the Scottish and French courts fostered this, and several poets numbered among her close friends, while she was also the subject of several poems written by friends and admirers. She also played an active role in many court festivities, and was present for several notable events, including the negotiations with Burgundy in 1445 where she greeted Isabel of Portugal (with whom she was to become close) alongside Queen Marie and the redoubtable Yolande of Aragon, and also the betrothal of her cousin Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou in the same year. Her contemporary Martin Lefranc described Margaret as ‘Une estoile clere et fine’- a star brilliant and pure.

Died after a sudden illness in a lodging in the cathedral cloister of Chalons, on 16th August 1445. At the end Margaret was deeply troubled by slanderous rumours spread by a certain Breton named Jamet de Tillay, which had distressed her frequently over the previous year and which preyed on her mind in her delirium. Though she was eventually induced to forgive him in her final hours, she does not seem to have found peace. After this she allegedly only spoke twice more, first when she was heard to whisper to herself miserably, ‘Were it not for my pledged word, I might well repent ever having come to France’, and later, her last words, ‘Fie on the life of this world, do not speak of it anymore to me.’* She was first buried in Chalons but decades later she was finally moved to Thouars Abbey according to her wishes. She was not yet 21.

The king and queen of France, who had lost their own daughter Radegunde the previous year, were deeply upset by Margaret’s death, and she was widely mourned at the French court. Her death also came only a month after that of her mother, Joan Beaufort, while Margaret’s orphaned sisters Eleanor and Joan, who had been invited to join her in France earlier that year, arrived only a few days after their sister’s death to find the French court in mourning. The youngest of the sisters, Annabella- then only around eight or nine years old- also received news of the deaths of both her mother and sister when she was far from home, on her way to Savoy to be married, and Isabel of Portugal provided her with mourning clothes for the occasion. Meanwhile Isabel Stewart, duchess of Brittany and the sister closest to Margaret in age, had a poem about the dauphine’s death transcribed into one of her books of hours, which still survives. The author of the Book of Pluscarden- probably Margaret’s ex-treasurer- also later translated her French epitaph into Scots, claiming this was at the request of her brother James II. One or two members of Margaret’s circle at the French court also composed poems in her memory. However all of Margaret’s own writings- to which she had devoted so much time and passion in life- were destroyed after her death on the orders of the dauphin, and no examples of her poetry have survived.

Read more here, here, here, here

*Translation loose and informed by sources cited above, not my own as my French is basically non-existent.

#Margaret Stewart Dauphine of France#Scottish history#French history#women in history#history edit#shoddy history gifsets#All the King's Horses

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, December 25th:

Cleopatra Selene II, Queen of Numidia and Mauretania, 40 B.C.

Alexander Helios, Prince of Egypt, 40 B.C.

Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France, 1424

Christina of Saxony, Queen of Denmark, 1461

Christine of Saxony, Landgravine of Hesse, 1505

Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain, 1584

Leopold II, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, 1700

Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, 1901

Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy, 1936

Alia al-Hussein, Queen of Jordan, 1948

#cleopatra selene#alexander helios#margaret stewart#christina of saxony#christine of saxony#margaret of austria#leopold ii#princess alice#princess alexandra#Alia al-Hussein#long live the queue#royal birthdays

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portraits from the Recueil d’Arras, a 16th century collection of images of royalty and other famous personages, attributed to Jacques Le Boucq

1. Henry VII of England

2. Elizabeth of York, Queen of England (This one exists only as an imprint of the original drawing left on the opposite page, so I enhanced it a bit to make it more visible)

3. James IV of Scotland

4. Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland

5. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V of England

6. Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy

7. Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France (Incorrectly labeled as Charlotte of Savoy)

8. James (I or II) of Scotland (Labeled only as “James, King of Scots”)

9. Mary I of England (Labeled as Elizabeth I, but I think it’s Mary because I’ve only ever seen that triangle hood on her)

10. Elizabeth I of England

Check out the entire digitized manuscript, featuring a total of 293 portraits, here!

#this thing rocks so hard#they're mainly copies of contemporary portraits#and we know they're largely accurate because some of the original portraits have survived to compare them to#definitely gonna do a second post#manuscript#tudors#plantagenets#stewarts#art history#Recueil d'arras

200 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(Pierre-Charles Comte, Alain Chartier and Margaret of Scotland, 1859)

(Edmund Blair-Leighton, Alain Chartier, 1903)

“The story of the famous kiss bestowed by Margaret Stewart, Dauphine de France, on ‘la précieuse bouche de laquelle sont issus et sortis tant de bons mots et vertueuses paroles’ (“The invaluable mouth from which issued and which left so many witty remarks and virtuous words”) is mythical, for Margaret did not come to France till 1436, after the poet’s death; but the story, first told by Guillaume Bouchet in his Annales d’Aquitaine, is interesting, if only as a proof of the high degree of estimation in which the ugliest man of his day was held.”

#pierre charles comte#edmund blair leighton#alain chartier#medieval#art#art history#margaret stewart#history painting#pre raphaelite brotherhood

192 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The ceremony took place at the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris on 24 April 1558. It was a Sunday and the citizens of Paris flocked to see the spectacle, as was intended. Henry II would not have wasted the opportunity to display Valois power and prestige and his mastery of the public event was very much in evidence at the wedding of the Scottish queen destined to be the wife of his eldest son. A covered walkway had been erected to frame the bridal procession as it made its way from the palace of the archbishop of Paris to the main entrance of the cathedral itself, where a raised stage across the west front allowed onlookers a better view of the leading participants in this wedding that was intended to unite two kingdoms forever. No doubt the Scottish lords present would have taken great pride in their queen when she appeared, flanked by her future father-in-law and her cousin, the duke of Lorraine.

Mary was tall for her age and already a fine-looking woman. She had deliberately broken with tradition and chosen a white wedding dress, presumably because she thought it showed off her colouring better and would also attract attention. White was normally the colour of mourning in France and the widows of French kings were supposed to wear it for months after their spouse’s demise, so Mary made an emphatic break with tradition when she chose it for her wedding day. Those who saw portents in such choices might have felt a frisson of concern for this confident beauty who flaunted the traditions of French royalty so alluringly but Mary does not seem to have been subject to such doubts. The dress itself was made of white satin and it glittered with diamonds and jewelled embroidery. Over it she wore a mantle of blue velvet embroidered with white silk and pearls, tapering into a long train that was carried by two maids of honour.

The jewels worn by Mary were equally impressive. She had a splendid pendant around her neck, engraved with Henry II’s initials. She called it ‘Great Harry’ and eventually placed it among the Scottish Crown jewels. Her hair hung loose down her back, as was customary with brides in those days, and on her head was a magnificent gold crown studded with gems – rubies, diamonds, sapphires, emeralds and pearls – all gleaming in the bright light of a Parisian spring day. The marriage ceremony was performed by Charles Bourbon, the cardinal archbishop of Rouen, and the wedding ring was taken by the king of France off his own finger and handed to his son to be placed on Mary’s. This could be seen as a gesture of affection or a further indication of his complete ownership of the Scottish queen herself. A nuptial Mass followed as Francis and his wife sat on thrones beneath a canopy of cloth of gold.

Mary had upstaged her husband by making herself the centre of attention, perhaps the first time in the sixteenth century that the bride, rather than the groom, took all the attention at a royal wedding. Back in 1503 Mary’s grandmother, Margaret Tudor, could only have wished for such admiration. The dauphin, however, seems to have taken his bride’s stealing of the limelight in good part. Perhaps he was getting used to it by then and he was certainly no heroic figure himself. Physically, he and Mary were a totally mismatched pair. Mary’s letter to her mother claiming that it was the happiest day of her life shows, if she genuinely meant what she said, that dynasticism was her driving motive in life. She had, no doubt, learnt this from those all around her. In truth, Mary was marrying a sickly runt. The prince looked younger than fourteen and was reported to be sexually immature; it was said that his testicles had not dropped. Despite this, there were reports that the union had been consummated but there would scarcely have been any publicity if the opposite were, in fact, the case. Francis appears to have been genuinely fond of the glittering girl who looked at least twenty sitting beside him in Notre Dame and he knew his duty. The marriage would give him the crown matrimonial of Scotland and the impressive if clumsy title of King-Dauphin while his wife became Queen-Dauphiness. Presumably he also knew, as the Scottish nobility watching did not, that his father had made sure that Scotland would remain subject to French rule even if Mary were to die childless. His wife could have her moment in the sun but the Valois family would be winners in the end.” — Linda Porter, Tudors versus Stewarts: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary, Queen of Scots

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#scotlandsladies#history#Mary Queen of Scots#Francis II of France#Mary I of Scotland#*mine#*gifs

179 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On Monday July 25th 1603 James VI of Scotland became the I of England after he and his beautiful Anna of Denmark were crowned King and Queen of England at Westminster Abbey. James arrived to London on May of that year, his wife was not with him at the time because she was heavily pregnant but she arrived in time for their coronation. There had not been another joint coronation in almost a century. The last being the one with his predecessor’s father with his first spouse, Katherine of Aragon in 1509. He was also the first Scottish King to see the stone of Scone again. (The stone had been taken by the English under Edward I and placed in the coronation chair.) As usual, the archbishop of Canterbury (John Whitgift) was in charge of the ceremony, anointing the couple with the holy oils before placing the crowns of the St Edward and St Edith on their heads.

“When he [James VI] entered London for the first time on that spring morning in 1603” Linda Porter writes in her biography (‘Tudors vs Stewarts: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary, Queen of Scots’), “he was fulfilling the hopes of the marriage of James IV to Margaret Tudor a century before that the two crowns might, one day, be united.” And she is right. Henry VII did a lot to ensure peace between both kingdoms and agreed to prosecute border criminals in courts of law that would include Scottish and English jurors (to avoid bias). He also worked with Scottish noblemen to ensure that there would be less raids on England’s Northern borders and Scotland’s Southern border. It is hard to say though, that Henry VII would have ever envisioned this future for his country. Maybe Porter is right and he did. His ancestor Edward I certainly tried this when he negotiated a marriage between the maid of Norway (who died before she could be crowned Queen of Scots) and his heir, Edward of Caernarfon (future Edward II). Henry VII’s son, Henry VIII, almost succeeded but Mary of Guise was a lot smarter than he thought, and she sent her daughter away to France to marry the Dauphin, instead of his heir.

James VI was twice descended from Henry VII through both his parents. Mary, Queen of Scots as you all know, descended from Margaret Tudor’s first marriage to King James IV of Scotland, while Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley descended from her second to the Earl of Angus.

After Queen Elizabeth I’s death on the 24th of March 1603, parliament declared in favor of James and Robert Cecil sent a messenger to Scotland less than a month later to tell the King of Scotland of the recent events. James immediately set out for England. On the day of his coronation, he and Anne were gorgeously dressed, and even though there was an outbreak of plague, “the streets seemed paved with men and women” wrote one observer, that were eager to see their new king and queen. This was after all, the end of an era -the Tudor era- and the start of a new one.

Read the rest here: https://tudorsandotherhistories.wordpress.com/2015/07/25/james-vi-of-scotland-becomes-i-of-england/

#James VI of Scotland and I of England#Tudor#Stuart#History#Modern era#Renaissance#July 1603#Coronation

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A 1797 copper engraving of Margaret (Stewart) of Scotland, Dauphine of France (1424-1445), published in ‘Iconographia Scotica’ by John Pinkerton.

#margaret stewart dauphine of france#margaret of scotland#house of stewart#history#scottish history#kingdom of scotland#p: margaret dauphine of france#princesses#artwork#*artwork#ours

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 5th 1560 The Treaty of Edinburgh was drawn up between England and France bringing to an end the siege by English troops of French forces occupying Leith. (some places say July 6th)

Two events in 1560 combined to create the environment for the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh. In February, the Treaty of Berwick was signed, which led to English troops entering Scotland. And in June, the Catholic Mary of Guise, mother of Mary, Queen of Scots, and co-Regent of Scotland, died. That latter event signalled and end to Catholic resistance in Scotland. The Treaty of Edinburgh was then concluded on the 6th of July, 1560.

With the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I and French representatives in Scotland agreed to formally conclude the Siege of Leith, abolish the ‘Auld Alliance’ between France and Scotland, establish a new Anglo Scottish accord, and maintain the peace between England and France that had been agreed by the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis. Also included in the Treaty was the agreement for Mary, Queen of Scots, and her husband, the French King François II, to give up Mary’s claim to the English crown and to recognise Elizabeth I as rightful Queen of England.

The earlier Treaty of Berwick was signed on the 27th of February, 1560, between the representatives of Queen Elizabeth I of England and the Scottish Lords of the Congregation. The result of that treaty was that an English fleet and an army came to Scotland to help expel the ten thousand French troops that were defending the Regency of the Catholic Mary of Guise. The reason Elizabeth was so keen on that treaty was because she feared that France intended to rule Scotland, which would have threatened her realm. In addition, she feared greater unity between Scotland and France, and in particular, Mary Stewart’s claim to her throne.

Mary had a strong claim to that throne, through her grandfather, James IV, who was married to Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII. Catholic Mary was therefore a legitimate relative of Henry VIII, unlike Protestant Elizabeth, who was illegitimate, at least in Catholic eyes, because they saw her father’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s mother, as being illegal. Ipso facto, she was not the true Queen of England.

In addition, when Mary had married the then fifteen year old Dauphin, François, on the 24th of April, 1558, when she was herself just fourteen, the two countries had signed an accord. That agreement stipulated that the crowns of Scotland and France would be unified if there were children of the marriage, and the crown of Scotland would be given to France if there were not. From a French point of view, because Mary had legitimate claims, they wanted her to be the Queen of England, Scotland and France. Voilà!

Another factor concerning Elizabeth was the desire to further hasten the Reformation in Scotland, which is why the Scottish Lords of the Congregation were trying to get the Catholic French expelled. For Elizabeth, if Scotland were Protestant, that would make it an ally and help protect England. Armed conflict ensued and the English arrived. French troops retreated, and fortified the port and town of Leith against the combined force of English and Scottish Protestants. And so began the Siege of Leith.

With the death of Mary of Guise, on the 11th of June, 1560, the figurehead of the Scottish Catholic resistance was removed. Mary of Guise had been ruling as Queen Regent on behalf of her absent daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, who was at that time also Queen Consort in France. In Mary’s absence, the Lords of the Congregation acted on Scotland’s behalf or more properly, their own behalf. Some were confirmed Protestants and couldn’t see past their religious fervour, but some were just chancers who saw an opportunity to claim power for themselves. The terms of the treaty were drawn up on the 5th of July by John de Montluc, Bishop of Valence, Charles de la Rochefoucault, Sieur de Randan, Sir William Cecil and Nicholas Wotton, Dean of Canterbury and York. It was concluded on the following day, the 6th of July, 1560. Nobody asked Mary, Queen of Scots, if that would be OK.

After the Treaty was signed, the French and English armies left Scotland and left the Scottish Protestant nobles in charge – properly delighted with themselves. Later, in August, the ‘Reformation Parliament’ of 1560 met and ratified the acts that would establish the Protestant Kirk in Scotland. It prohibited the practise of the Latin Mass in Scotland and denied the authority of the Pope, in effect implementing the Reformation across Scotland. The detestable John Knox was one of the leading figures during the rebellion against Mary of Guise and French Catholic control of Scotland. The signing of the Treaty and the removal of the French enabled him to return from Europe to lead the fight to make Scotland Protestant. Ultimately, he and his Calvinist successors succeeded. On the 5th of December, 1560, the eighteen years old Mary, Queen of Scots, was widowed and, as Charles IX had no real incentive to support her, she was increasingly isolated in France. The French also had more to do with their own affairs after the outbreak of the Wars of Religion. And so, on the 19th of August, 1561, Mary had little choice but to accept an invitation to return to Protestant Scotland as Queen. Now, don’t forget, the Treaty of Edinburgh had not been ratified by Mary, Queen of Scots. She was the reigning monarch and it needed her ratification, but as somebody might have said, ���Ach weel, it was lackin’ only a signature and hersel’ still a wee bit lassie, just.” Mary was put under considerable pressure to ratify the Treaty, but she had no intention of so doing. She viewed the Lords of the Congregation as rebels and traitors against herself and her mother, Mary of Guise. Another reason for not ratifying the treaty was because it officially declared Elizabeth I Queen of England, effectively ending Mary’s claim to that throne. When all was said and done, Mary had to accept the terms of the Treaty, but she never signed.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On This Day In History . 12 February 1424 . King James I of Scotland married Joan Beaufort . . King James I of Scotland of the House of Stewart married Joan Beaufort, a cousin of Henry VI of England & the niece of Thomas Beaufort, 1st Duke of Exeter, & Henry, Bishop of Winchester. . ◼ They were wed at St Mary Overie Church in Southwark. They were feasted at Winchester Palace that year by her uncle Cardinal Henry Beaufort. She accompanied her husband on his return from captivity in England to Scotland, and was crowned alongside her husband at Scone Abbey. As queen, she often pleaded with the king for those who might be executed. . The royal couple had eight children; . ◾ Margaret Stewart, Princess of Scotland (1424–1445) married Prince Louis, Dauphin of Viennois (later King Louis XI of France) . ◾ Isabella Stewart, Princess of Scotland (1426–1494) married Francis I, Duke of Brittany . ◾ Mary Stewart, Countess of Buchan (died 1465) married Wolfart VI van Borsselen . ◾ Joan of Scotland, Countess of Morton (c. 1428–1486) married James Douglas, 1st Earl of Morton . ◾ Alexander Stewart, Duke of Rothesay (born and died 1430); Twin of James . ◾ James II of Scotland (1430–1460) .. ◾ Eleanor Stewart, Princess of Scotland (1433–1484) married Sigismund, Archduke of Austria uncle Cardinal Henry. . ◾ Annabella Stewart, Princess of Scotland (c. 1436 – 1509) married and divorced 1. Louis of Savoy, and then married and divorced 2. George Gordon, 2nd Earl of Huntly . . . #onthisdayinhistory #thisdayinhistory #d12feb #theyear1424 #JamesI #JamesIofScotland #KingofScots #history #JoanBeaufort #Scottishmonarchy #HouseofStewart #britishmonarchy #Southwark #Wedding #RoyalWedding #London #England #historyfacts #Scotland #arthistory (at Southwark) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bty_V55leZS/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=taikl5dtrrhp

#onthisdayinhistory#thisdayinhistory#d12feb#theyear1424#jamesi#jamesiofscotland#kingofscots#history#joanbeaufort#scottishmonarchy#houseofstewart#britishmonarchy#southwark#wedding#royalwedding#london#england#historyfacts#scotland#arthistory

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I try so hard to be unbiased when it comes to history...

...but then I remember that Louis XI probably had all of Margaret Stewart’s poems destroyed and I burn with rage

#Look Louis I try very hard to understand your point of view#But that was not necessary#AT ALL#Margaret Stewart Dauphine of France#Louis XI#The Auld Allies#I say probably because I can't read French and double check all the sources myself but Barbe is pretty sure

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, December 25th:

Cleopatra Selene II, Queen of Numidia and Mauretania, 40 B.C.

Alexander Helios, Prince of Egypt, 40 B.C.

Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France, 1424

Christina of Saxony, Queen of Denmark, 1461

Christine of Saxony, Landgravine of Hesse, 1505

Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain, 1584

Leopold II, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, 1700

Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, 1901

Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy, 1936

Alia al-Hussein, Queen of Jordan, 1948

#cleopatra selene#alexander helios#christina of saxony#christine of saxony#margaret of austria#leopold ii#princess alice#princess alexandra#Alia al-Hussein#long live the queue#royal birthdays#margaret stewart

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France

Margaret Stewart (25 December 1424 – 16 August 1445) was a princess of Scotland and the dauphine of France. She was the firstborn child of King James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort.

She married the eldest son of the king of France, Louis Dauphin of France, at eleven years old. Their marriage was unhappy, and she died childless at age 20, apparently of a fever.

0 notes