#shoddy history gifsets

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Shoddy History Edits: Mary Stewart, Countess of Arran

The oldest surviving daughter of James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders, Mary Stewart was probably born in Stirling in July 1451*. Over the course of the next decade she would be joined by at least five siblings, four of whom lived to adulthood- the future James III (b.1452), Alexander Duke of Albany, John Earl of Mar, and Lady Margaret Stewart. Although their births secured the future of the Stewart dynasty, the early lives of these children were not exactly stable and Mary would lose both her parents by the age of thirteen. Following her father’s accidental death at Roxburgh in 1460, her mother took charge of the government of Scotland on behalf of the young James III, until her own early demise in late 1463. After this Mary’s powerful kinsman James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews, assumed a leading role in the kingdom’s affairs but when he died in turn in 1465, things began to get a bit out of hand. Possession of the king’s person was a valuable commodity during Scottish minorities and it wasn’t long before the favoured tactic of ‘rule by kidnap’ was employed by Robert, Lord Boyd.

In summer 1466, a group of Boyd supporters led by Robert’s brother, Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll, seized the fourteen year old James III while the king was out hunting near Linlithgow, and took control of government. A reasonable amount of nest-feathering ensued, which was not entirely unexpected. However the Boyds seem to have overstepped the mark when, on or around 26th April 1467, Lord Boyd’s eldest son Thomas was created Earl of Arran and wed the king’s older sister Mary. We don’t know what Mary herself thought about this sudden development but her brother certainly didn’t like it- James would claim in later years that he wept at the wedding, but was unable to stop it out of fear that he and his brothers would be destroyed. This bold move from the Boyds- whose chief representative was only a lord of parliament before 1467- may not have impressed the wider political community much either, especially since Mary was the eldest daughter and was probably expected to make an important match with another powerful European dynasty*. After all, several of her paternal aunts had married into princely dynasties- like the late Margaret (d.1445), who had married the dauphin of France, Isabella (d. after 1494) who married the duke of Brittany, and Eleanor (d.1480) who married the (Arch)duke of Further Austria, while three other aunts had also been involved in important, if obviously less impressive, marriage negotiations. During her mother’s negotiations with Margaret of Anjou in 1460, Mary herself had been suggested as a bride for Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, the son of the exiled Henry VI of England. But as fate would have it, neither of James III’s sisters were destined to marry outside the kingdom- although, like her younger brother Alexander, Mary would experience her fair share of European travel.

After three years of power, the tide began to turn for the Boyds in the summer of 1469. Robert, Lord Boyd had been busy over the past year arranging the king’s marriage to Margaret, daughter of Christian I of Denmark, and now he and his son Thomas, Earl of Arran, had the honour of escorting the royal bride back to Scotland. But in the meantime James III had finally managed to seize the reins of government, and, by the by, he had also come to the conclusion that Lord Boyd and his son weren’t really in need of their heads. This must have put something of a damper on proceedings when the Boyds’ ship docked in Leith. Later sixteenth century accounts claim that Thomas Boyd was intercepted on board by his wife Mary, who warned him of her brother’s intentions. Instead of disembarking with the rest of the fleet, the couple promptly sailed away from Scotland again, with Thomas’ father Robert joining them later in exile- a sensible precaution really since James had Robert’s brother Alexander Boyd of Drumcoll executed on the castle hill of Edinburgh a few months later, and forfeited the possessions and lives of Robert and Thomas Boyd in absentia**. Whether or not Mary played an active role in the flight of her husband and father-in-law like the sixteenth century writers claim***, we do know that she joined them in exile. Sixteenth century sources claim that the Boyds in vain sought the support of the king of France, while contemporary sources show that Mary and the Boyds took refuge in Flanders, throwing themselves on the mercy of her cousin Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.

Bruges was then a fashionable place for exiled British royals to mooch around (Edward IV of England and co. were also in residence over the winter of 1470-71). Charles the Bold was not always a reliable ally but, in the Boyds’ case, he did at least send a message to James III through his ambassador Anselm Adornes (soon to become a favourite with the king of Scots), asking for the Scottish exiles to be pardoned and allowed to return home. James thanked the duke for his courtesy to his sister but stoutly refused, recounting the Boyds’ crimes and arguing that the duke, “ought no longer to favour traitors, who to the king’s dishonour had brought his sister to exile in many foreign lands.” So the Scottish exiles remained in Bruges for some time, staying at the Hotel de Jerusalem which belonged to Anselm Adornes while its owner went on pilgrimage to the real Jerusalem. During this time Mary gave birth to two children- James and Margaret Boyd- whose godmother was Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy.

In late 1471, though, the situation looked like it was improving. Some modern historians interpret the sources as stating that a plan was developed for the Boyds and Mary cross the sea again, and for Mary to travel to Scotland to soften her brother up while the Boyds waited in England until it was safe for them to return. On the other hand, sixteenth century writers like George Buchanan and John Leslie were of the opinion that James III had lured his sister home under false pretences, “on account of the great love she bore to her husband.” In any case, a safe conduct from Calais was granted to the exiles, and to Anselm Adornes who was to accompany them, and they sailed for England in October 1471. Thomas Boyd said goodbye to the rest of the group in the southern kingdom, and went to the court of the newly restored Edward IV, where he had business with the king. The rest of the party went on to Alnwick, where they were to remain to await the outcome of Mary’s mission (Robert, Lord Boyd, now quite old, is supposed to have died there). Mary then crossed the border with Anselm Adornes and his wife. She is not known to have seen her first husband again.

Little is certainly known of Mary’s career between her return to Scotland in 1471-2 and her second marriage in 1474, but clearly any plans to restore the Boyds to favour failed. Mary herself was receiving ferms from lands in Scotland by late 1473 at least, if not earlier, indicating that, if not exactly back in favour, she was at least able to conduct some business without royal obstruction. Both Leslie and Buchanan (and other writers) claim that she was detained by her brother in Ayrshire while James III wrangled a divorce between Mary and Thomas. The grounds and exact process of any such “divorce” are unknown, other than Buchanan’s puzzling story that the king summoned Thomas Boyd to Kilmarnock to answer for his crimes within sixty days and that, when Boyd naturally failed to appear, the marriage was declared illegitimate. Mary was then married (by force and “against her inclination” according to Buchanan) to James, Lord Hamilton, a man many years her senior but greatly favoured by the king. Once again we do not know Mary’s thoughts on this match, but it had taken place by Easter 1474, when, at the king’s command, “my Lady of Hammiltoune the Kingis sister” was given six ells of purple velvet for a kirtle. We know this was not James III’s younger sister Margaret (though she did later reside in Hamilton) since in July of the same year, Lord Hamilton surrendered several lands into the king’s hands so that they could be granted back in conjunct fee to the couple, with the wife named as “Marie Senescalli ejus sponse, sorori regis”. But aside from the minor detail that Mary’s first husband was perhaps still cutting about, there were other impediments which made the new couple’s relationship less than legal. Accordingly, in April 1476, Pope Sixtus dispensed them from the impediments of consanguinity, affinity, and public honesty, and declared the child which had since been born to them legitimate. By the time of Lord Hamilton’s death three years later, at least two children had been born of the marriage- a boy named James and a girl named Elizabeth.

In the meantime, Mary’s first husband Thomas appears to have died abroad, though we have almost no information about his life following their separation, and even the sixteenth century writers do not agree on this point. Buchanan claims that he died in Antwerp not long after the “divorce”, and was buried there with great honour on the orders of Charles the Bold (he also gives his personal opinion that James Hamilton was far inferior to Mary’s first husband- hindsight is a wonderful thing). The Italian humanist Giovanni Ferreri had obviously heard very different stories about Thomas and his character from his Scottish sources, and, in his rather unreliable continuation of Hector Boece’s history, he gave Thomas a reputation as a man capable of any vice, and claimed that, after much travelling in Europe, he was murdered in Italy by a man whose wife he had seduced. But two letters in the celebrated collection of the Pastons of Norfolk have survived which refer to Thomas Boyd’s time in England , and the first of these gives a very different character sketch to that offered by Ferreri- and a rare contemporary insight into the whole affair. On 5th June 1472, John Paston the younger wrote to his older brother of the same name:

“"Also I prey yow to recomand me in my most humbyll wyse unto the good Lordshepe of the most corteys, gentylest, wysest, kyndest, most compenabyll, freest, largeest, most bowntesous knyght, my Lord the Erle of Arran, whych hathe maryed the Kyngs sustyr of Scotland. Herto he is one the lyghtest, delyverst, best spokyn, fayrest archer; devowghtest, most perfyghte, and trewest to hys lady of all the knyghtys that ever I was aqweynted with; so wold God, my Lady lyekyd me as well as I do hys person and most knyghtly condycyons, with whom I prey yow to be aqweynted, as yow semyth best; he is lodgyd at the George in Lombard Street.**** He hath a book of my syster Annys of the Sege of Thebes; when he hath doon with it, he promysyd to delyver it yow."

We are offered no such contemporary insight into Mary’s character, which must remain something of a mystery, although if even half of what the sixteenth century writers claim about her is true, she must have had her fair share of both mettle and misfortune. Though she never saw her husband again, her two children by Thomas Boyd were eventually allowed to return to Scotland and, in the early 1480s, young James Boyd was even allowed to succeed to his grandfather’s title of Lord Boyd, possibly through his mother’s political influence. Norman MacDougall has raised the possibility that the young Boyd- then only in his early teens- returned to Scotland in 1482 in the company of his uncle Alexander, Duke of Albany, who had invaded Scotland with Richard, Duke of Gloucester and an English army. Since James III wasn’t entirely free to govern as he liked during this troubled period, MacDougall suggests that Mary Stewart may have seen her chance to rebuild the Boyd patrimony in Ayrshire. The fact that the grants of land made to James Boyd (several of which which Mary received liferent of) were part of the queen’s dower and supposedly could not be alienated meant that the grants were semi-illegal, and unlikely to have been made by the king acting on his own initiative. But James Boyd’s career was destined to be brief and when his uncle Alexander fled to Dunbar in 1483, the nephew followed and the grants made to him were rescinded. The following year, the young James (who could not have been much older than fifteen) was killed by Hugh Montgomery of Eglinton, sparking a local feud in Ayrshire between the Boyds and the Montgomeries which lasted over a century.

Mary was only in her early thirties but she had already lost two husbands and was now left to bury her teenaged son. Of her four siblings, only two remained by 1488, since John, Earl of Mar, had perished in mysterious circumstances in royal custody in 1479 and Alexander, Duke of Albany met his end in 1485, when he was hit by a splinter from the lance of the Duke of Orleans (the future King Louis XII) during a tournament in France. However, Mary did not live long enough to see the death of her last brother James III at the Battle of Sauchieburn in June 1488, since she herself seems to have died earlier that year, aged around 37.

Her posthumous legacy, as with so many other women of her time, has generally been seen in terms of the later prospects of her offspring. The descendants of her two children by Lord Hamilton were destined to play an important role in the fraught politics of sixteenth century Scotland. From her son James Hamilton were descended the Earls of Arran, including the Regent Arran who governed Scotland on behalf of the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, by virtue of his position as “second person of the realm” and the little queen’s direct heir through his descent from her great-great aunt and namesake. Mary’s younger daughter Elizabeth Hamilton married Mathew Stewart, Earl of Lennox, and Elizabeth’s grandson the 4th Earl of Lennox would later challenge the claims to the throne of his cousin the Regent Arran, creating a rivalry at the very heart of Scottish politics. Margaret Boyd, the only surviving child of Mary’s first marriage, married first Lord Forbes and then returned to Ayrshire to marry the first Earl of Cassilis. Although Mary Stewart herself remains a shadowy figure to this day, her story- both factual and speculative- has attracted interest and sympathy throughout the centuries and still offers opportunities for further discovery.

Additional notes and references below the cut.

Edit: the ‘read more’ section isn’t showing up on a lot of versions of this, so I will just have to put all the notes and sources below, even though it’s messy:

* In the twentieth century there was quite a bit of debate over the correct dates of birth for James III and Mary. Despite what is on wikipedia, this has largely been resolved and the general consensus is that Mary was the elder sibling.

** Some historians have debated whether Mary’s marriage prospects were quite so important to the political community in 1467 as has been traditionally assumed, but the Stewart dynasty’s contemporary European marriage alliances are nonetheless important to bear in mind.

*** Lord Boyd’s two younger sons were spared the king’s wrath however, and the youngest of them, Archibald Boyd of Naristoun, was the father of Marion Boyd, a mistress of James IV.

**** In all fairness though, we have so few contemporary chronicles/histories for the reign of James III that we have to take the sixteenth century writers at their word sometimes, especially where they agree with each other. Nonetheless we should always be cautious.

**** It’s worth noting that the site of the George in Lombard street in London is still occupied today, since there has been an inn on the spot since the twelfth century and its current incarnation is an eighteenth century building housing the George and Vulture restaurant. It seems that several of the buildings of Anselm Adornes’ estate where the Boyds were housed in Bruges also still exist, though I will have to do more research on this.

References (I have included links to online versions where available):

- “The Date of the Birth of James III”- there are two articles by this name in the Edinburgh Historical Review for the years 1950 and 1951 respectively, and both of them were consulted. The author of the first was Annie I. Dunlop while corrections and debate between Dunlop and Dr William Angus comprise the second.

- “James III”, by Norman MacDougall

- “Power and Propaganda: Scotland, 1306-1488″, by Katie Stevenson

- “The Boyds in Bruges”, W.H. Finlayson

- “A Letter of James III to the Duke of Burgundy”, C.A.J. Armstrong

- John Lesley’s “The Historie of Scotland”

- This translation of George Buchanan’s “History of Scotland”

- “Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland”, vol. 1

- “The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland”, vol. 5

- “Register of the Great Seal of Scotland”, vol. 2

- “Vetera monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum historiam illustrantia...”, Augustin Thenier

- “The Paston Letters”, vol. 3, edited by James Gairdner

- Giovanni Ferreri’s continuation to Boece I had to use the translation from this website since I couldn’t get access to the 1574 printing any other way, though my reading is backed up by secondary sources.

#This was not my best edit I may redo it later#My sources are pretty decent though so proud of that#women in history#British history#History edits#But had to get the word out about Mary- apologies for the length when I know there's not much definite info on her but context is important#Also James III and his siblings were a bonfire of insanity- Mary actually got off comparatively lightly#I don't know what was in the air in the 1470s- the York brothers were just as bad and on the continent there's a fair few similar cases#the Stewarts#shoddy history gifsets#Mary Stewart Countess of Arran

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Edits: Margaret Stewart, Dauphine of France

Born Christmas 1424, Margaret Stewart was the eldest child of James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort, and older sister to Isabella, Duchess of Brittany; Joan Countess of Morton; James II, King of Scots; Eleanor, Archduchess of Austria; Mary, Lady of Veere and Countess of Buchan; and Annabella, Countess of Geneva/Huntly. Though her father’s reign was turbulent- ending in his murder in 1437- what little is known of Margaret’s childhood indicates that it was relatively happy, though at the age of 11 she was to leave Scotland, never to return. Having taken a tearful farewell of her father, she sailed from Dumbarton in March 1436, bound for France, where she was to marry the heir of King Charles VII.

Married Louis, Dauphin of Viennois- the future Louis XI of France- in Tours on 25th June 1436. Though her relationship with her husband was reputedly bad and the two were generally estranged, she was a beloved daughter-in-law of Charles VII and Marie of Anjou, and generally popular at court, both for her personality and beauty. Famous for her love of poetry, she spent many sleepless nights composing ballades until dawn, and allegedly sometimes wrote as many as twelve a day. The literary atmosphere of the Scottish and French courts fostered this, and several poets numbered among her close friends, while she was also the subject of several poems written by friends and admirers. She also played an active role in many court festivities, and was present for several notable events, including the negotiations with Burgundy in 1445 where she greeted Isabel of Portugal (with whom she was to become close) alongside Queen Marie and the redoubtable Yolande of Aragon, and also the betrothal of her cousin Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou in the same year. Her contemporary Martin Lefranc described Margaret as ‘Une estoile clere et fine’- a star brilliant and pure.

Died after a sudden illness in a lodging in the cathedral cloister of Chalons, on 16th August 1445. At the end Margaret was deeply troubled by slanderous rumours spread by a certain Breton named Jamet de Tillay, which had distressed her frequently over the previous year and which preyed on her mind in her delirium. Though she was eventually induced to forgive him in her final hours, she does not seem to have found peace. After this she allegedly only spoke twice more, first when she was heard to whisper to herself miserably, ‘Were it not for my pledged word, I might well repent ever having come to France’, and later, her last words, ‘Fie on the life of this world, do not speak of it anymore to me.’* She was first buried in Chalons but decades later she was finally moved to Thouars Abbey according to her wishes. She was not yet 21.

The king and queen of France, who had lost their own daughter Radegunde the previous year, were deeply upset by Margaret’s death, and she was widely mourned at the French court. Her death also came only a month after that of her mother, Joan Beaufort, while Margaret’s orphaned sisters Eleanor and Joan, who had been invited to join her in France earlier that year, arrived only a few days after their sister’s death to find the French court in mourning. The youngest of the sisters, Annabella- then only around eight or nine years old- also received news of the deaths of both her mother and sister when she was far from home, on her way to Savoy to be married, and Isabel of Portugal provided her with mourning clothes for the occasion. Meanwhile Isabel Stewart, duchess of Brittany and the sister closest to Margaret in age, had a poem about the dauphine’s death transcribed into one of her books of hours, which still survives. The author of the Book of Pluscarden- probably Margaret’s ex-treasurer- also later translated her French epitaph into Scots, claiming this was at the request of her brother James II. One or two members of Margaret’s circle at the French court also composed poems in her memory. However all of Margaret’s own writings- to which she had devoted so much time and passion in life- were destroyed after her death on the orders of the dauphin, and no examples of her poetry have survived.

Read more here, here, here, here

*Translation loose and informed by sources cited above, not my own as my French is basically non-existent.

#Margaret Stewart Dauphine of France#Scottish history#French history#women in history#history edit#shoddy history gifsets#All the King's Horses

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Edits: Eleanor of Scotland, Archduchess of Further Austria/Tyrol

Born c.1433, Eleanor Stewart was one of the seven surviving children of King James I of Scotland and his wife Joan Beaufort. Very little is known about Eleanor’s early life in Scotland, but her parents’ relationship was apparently an affectionate one and their children initially seem to have been raised in a close family environment. This all changed however when her father was murdered at Perth in 1437, when Eleanor was probably not yet four years old. Her six year old brother was crowned James II of Scotland, and during the factional squabbles of his minority, her mother Queen Joan fought for control of her son. Amidst all this political intrigue, little is known about the experiences of James II’s five unmarried sisters, though the second, Isabella, was married to the duke of Brittany in 1442; the fifth, Mary, married the son of the lord of Veere in 1444; while in 1445 the youngest of the sisters, Annabella, was sent to Savoy in preparation for her marriage to the Count of Geneva.

Eleanor’s career properly begins in April 1445, when a letter was sent to Scotland from Isabel of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy, with the support of Louis, the dauphin of France, and his wife Margaret Stewart, Eleanor’s oldest sister, suggesting that Eleanor be sent to the continent for in preparation for marriage. Eleanor, along with her older sister Joanna (who had not been named in the letter), travelled to France later that year, but they arrived they to find the French court in mourning for the dauphine, their sister Margaret, whom they had not seen in nine years and who had died only a few days before. Nonetheless, the French king Charles VII still undertook to support the two Scottish princesses, and Eleanor and Joanna spent the next few years at the French court, under the eye of their sister’s old lady-in-waiting Jeanne de Tuce, and passing the time in games of piquet and writing poetry. Several possible matches were suggested for Eleanor during this time, initially to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, while the possibility of a marriage to the widowed dauphin Louis may also have been raised. In the end however, Eleanor married Frederick III’s nephew Sigismund, duke of Further Austria, and the proxy ceremony took place at Chinon in September 1448 with the French king and queen in attendance. Eleanor then began the journey to her new home, finally arriving several months later in the Tyrol, high in the Alps, where she met her husband Sigismund for the first time, and their marriage was solemnised at Merano on 12th February 1449.

While little is known of the early years of Eleanor’s marriage to Sigismund, however the couple seem to have worked well together, though they were never to have any children (the common claim that Eleanor had a son named Wolfgang has been debunked in recent decades). She was clearly trusted enough by her husband to be appointed regent on several occasions when he had to leave Tyrol between 1455 and 1458. This period was particularly tense, and during her regency Eleanor had to weather the fall-out from issues such as her husband’s conflict with the reforming Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, and some of the correspondence of the rebellious abbess Verena von Stuben addressed to Eleanor survives relating to this notable affair. Other domestic problems such as the split between Sigismund and his former retainer Bernard Gradner caused more tension, however for the most part she discharged her role as regent ably, including raising and funding an army to defend the ducal interests, and personally taking control of various lands belonging to her husband to lessen the impact of any interdict that might be placed on Sigismund in his conflict with Nicholas of Cusa. She further acted as regent in the foothills during the late 1460s, though after this she retreated from political life and spent more time supporting religious endeavours in the Tyrol. Much more could be said about Eleanor’s regency, but due to lack of space it is safe to note that she was a capable and clever ruler, playing the role of both consort and regent with great skill.

She also seems to have been able to communicate in various languages and a considerable amount of her correspondence survives, not just relating to the internal affairs of the Tyrol, but also with various important European figures, as well as several Scots both at home and on the continent, not least her brother James II and her sister Isabella, Duchess of Brittany. One of her retainers Jorg von Ehingen visited Scotland in 1458 and his diary left us with our only contemporary image of King James II. The strategic position of her husband’s lands also meant that the couple hosted many important guests who passed through the Tyrol on their way north or south, including Christian I of Denmark, Rene Duke of Lorraine, and even, in 1472, Sophia Palaiologina, the Byzantine princess who was then travelling on her way north to marry Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow. Eleanor’s half-brother James Stewart, Earl of Buchan may also have passed in the vicinity of Innsbruck on his way to Rome in 1465, as did many lesser Scottish visitors who were no less well-received by their countrywoman, far from home as she was. However sometimes the crowd of guests seems to have fatigued Eleanor, and she frequently left busy Innsbruck to stay at quieter locations, such as Sigmundsburg, a now ruined castle on an island in Fernsteinsee, which was built for her as a ‘tribute’ by her husband around 1463. She must have been pleased with the hunting opportunities it presented as this was a past-time she particularly enjoyed. She also frequently visited Baden to ‘take the waters’ in the springs there.

However Eleanor is probably best-known for her cultural interests and came from a very literary background. Her father, James I, was probably the author of the Kingis Quair, which gives a poetic account of his captivity in England and his first sight of Eleanor’s mother Joan, while Eleanor’s eldest sister Margaret was famous for her obsession with poetry, allegedly writing as many as twelve ballads a day and frequently staying up all night to write. The French court was also a hub of poetic activity, and Eleanor’s interest in literature may have been fostered during her time there, while the nobility of Germany and Austria were no less culturally active, and Eleanor would have come into contact with other notable female literary patrons, such as Mechtild of the Palatinate. Her husband Sigismund also seems to have shared her interest in literature. Eleanor herself is most famous for the translation into German of the romance Ponthus and Sydonia, and this version was widely popular in the German-speaking world for some time afterwards, though it is unclear whether Eleanor translated all of the work herself or if she oversaw the process. Furthermore she was also known as a literary patron in her own time, and the Swabian humanist Heinrich Steinhowel dedicated “Von den Erlauchten Frauen”, his translation of Boccacio’s ‘De Claris Mulieribus’ (i.e. ‘Concerning Famous Women’), to Eleanor in 1473.

Eleanor Stewart died at Innsbruck on 20th November 1480 and is buried in Stams Abbey, along with her husband and several other Hapsburgs, and in the seventeenth century large effigies of Eleanor and the others were erected which still survive. She also left her mark, no matter how small, on many other buildings and places in the region, as well as the political and cultural life of the Tyrol, and her impact is of some interest on a wider European level, and not least for the country of her birth.

Sources because the ‘read more’ section isn’t showing up on a lot of reblogs.

*The costumes in the edit above are inaccurate I am aware, and I’ve probably missed a tonne of things out in this description of Eleanor���s career, or made a few mistakes but I’m working on learning more (unfortunately many of the sources are either unavailable or in a language I’m not very fluent in) and I’ve talked for too long anyway. Either way had to spread the love for this little-known Scottish princess who absolutely deserves more attention. If you can find the Scottish royal arms in Merano that’s usually worth at least some comment, but when they’re associated with a politically active princess and literary patron, even more so.

Some good resources for Eleanor- the primary biography is “Die Beiden Frauen des Erzherzogs Sigmund von Österreich”, by Margaret Köfler and Silvia Caramelle, which covers both Eleanor and Sigmund’s second wife Katherine of Saxony. However there are some accounts in English- a good one is Stewart’s article ‘The Austrian Connection’ in ‘Brycht Lanternis: Essays on the Language and Literature of Medieval Scotland’ (eds. Spiller and McClure), and a much shorter article about both Eleanor and her two eldest sisters Margaret and Isabella in ‘Women in Scotland, 1100-1750′ (eds. Ewan and Meikle), and Fiona Downie’s analysis of queens Joan Beaufort and Mary of Guelders in ‘She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland, 1424-1463′, also considers the role of the Scottish princesses, including Eleanor. There are many other articles and primary sources both in English and German (and French) but these should serve as an introduction.

#Scottish history#British history#Austrian history#women in history#history edit#fifteenth century#Eleanor Stewart Archduchess of the Tyrol#Who I have not talked up well enough here and I'm sure I made mistakes but I'm going to go back to translating that book this summer#So I'll correct them if I find them#shoddy history gifsets#All the King's Horses#the Stewarts#My fave

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Edits: Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll

Perhaps best known as the only sister of the infamous Mary, Queen of Scots, Jean Stewart had her own adventurous life, occupying the various roles of king’s daughter, honoured lady-in-waiting, unhappy spouse, outlaw, and excommunicant over the decades. Born in the early 1530s, she was the only certainly acknowledged* illegitimate daughter of King James V. Her mother was probably Elizabeth, a member of the sprawling, yet influential and ambitious Beaton family. On her father’s side, Jean’s numerous half-siblings included James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews who was also the future earl of Moray and Regent of Scotland; his older half-brother and namesake James Commendator of Kelso (d.1558); John Stewart Commendator of Coldingham; and Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, as well as her younger half-sister, Mary Stewart, who became queen of Scots at no more than a week old upon the death of their father in 1542.

As the king’s daughter she was raised at court in considerable comfort, and the Treasurer’s Accounts record various payments for her clothing, nurse, and upbringing-including payments for gowns, a canopy for her to travel under, massbooks, and mourning clothes after the death of her grandmother Margaret Tudor in 1541. Her brothers often travelled between court and St Andrews where they were being educated, but Jean was more permanently associated with the royal court. When her father married his second wife Mary of Guise, the new queen apparently took Jean under her wing, and brought her step-daughter into her own household. Jean briefly moved to the household of her first legitimate brother Prince James, who was born in 1540, but when the infant prince died the next year she returned to the queen’s household. After 1542, when her father died and the succession of the infant Mary ushered in a new period of strife, references to Jean are less frequent. However, we at least know that when her royal sister sailed for France in 1548, Jean did not travel with her, unlike several of her brothers and at least two of her cousins, (Mary Fleming and Mary Beaton). Instead, in 1553, by which time Jean was in her early twenties, Mary of Guise and the Regent Arran arranged for her to marry Archibald Campbell, Lord Lorne, and the wedding took place in April the following year. Her new husband succeeded his father as 5th earl of Argyll five years later in 1558. By that point, both Argyll and his close friend James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews- Jean’s half-brother- had converted to Protestantism. Though her own religious views are more of a mystery, the ideals of the new reformed faith, which was formally established in Scotland in 1560, were to play an important role in her life.

When Queen Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, she soon re-established links with her birth family, and several of Mary’s half-siblings regularly attended on her at court, though their relationships with the queen varied. The Countess of Argyll quickly renewed ties with the younger sister whom she had not seen since Mary was five years old, and though she is not as well-known as the infamous Four Maries, Jean served as one of her sister’s chief ladies-in-waiting for several years. “Ma soeur” received gifts of clothes and jewels from the queen, along with an annual pension of £150 pounds. Along with Agnes Keith (who married Jean’s brother James and became Countess of Moray in 1562) and Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, Jean was one of the ladies Lord Darnley later blamed for causing a rift between himself and his wife. At the christening of Queen Mary’s only son, the future James VI, in June 1566, Jean and the Earl of Bedford stood proxy for Elizabeth I of England as the child’s godmother. A few months earlier, on the fateful night of 9th March 1566, Jean had been the only other woman in the room when David Rizzio was murdered, though among the men present at the dinner were her half-brother Robert Stewart and her kinsman Beaton of Creich. Jean is supposed to have caught a candelabra when the table was knocked over in the struggle, preventing the room being plunged into complete darkness. Though both her half-brother the Earl of Moray and her husband the Earl of Argyll must have been aware that there was a plot to murder Rizzio, it is unclear whether Jean was forewarned. In any case it seems unlikely that her husband would confide in her, since by 1566 the couple had been estranged for years.

Jean was a proud and determined yet often stubborn woman, and does not appear to have relished having to leave the Lowlands and court life for mountainous Argyll. Her husband was unfaithful on several occasions but does not appear to have been willing to tolerate his wife’s own infidelity, if the accusations of adultery levelled at her in the late 1550s are at all truthful. Relations steadily worsened between the couple, and Jean later alleged that, in the summer of 1560, she had been held prisoner and intimidated by several of her husband’s Campbell kinsmen. Though Jean was briefly reconciled with Argyll through the intervention of mutual friends, including the reformer John Knox, by 1563 things had deteriorated again. This time Queen Mary and John Knox made a rare collaborative effort in an attempt to reconcile the warring spouses. Mary considered Argyll a close friend and important ally and could not risk offending him, yet at the same time she was fond of her sister, and in any case their public feuding was considered an embarrassment to both the reformed faith and the royal family. While Knox gave Argyll a thorough dressing down for his infidelity and refusal to patch things up with his wife, the queen warned Jean that should she ‘behave not herself as she ought to do, she shall find no favour of me’.

In 1567, Argyll joined with many other Scottish nobles, both Catholic and Protestant, in imprisoning Queen Mary, but baulked at the idea of deposing her. He later commanded the Queen’s Men at the Battle of Langside in 1568 and subsequently became one of her chief lieutenants in Scotland after she fled to England in the same year. Meanwhile, by 1567 his marriage had completely broken down. After Jean escaped yet another bout of imprisonment in one of her husband’s retainers’ castles, refusing return to her husband, the earl finally initiated divorce proceedings. In order to settle the matter quickly, Jean was offered 10,000 merks in return for agreeing to a divorce on the grounds of her husband’s adultery. But although she certainly had no intention of reuniting with Argyll, she refused to cooperate in the divorce- whether this was due to personal morality or because she wanted to protect her status as countess is unclear. In this she was supported by her half-brother the Earl of Moray, now Regent of Scotland for the young James VI. Moray had also fallen out with Argyll over politics by this point and, though both men remained Protestant, Moray seems to have been very opposed to divorce (like Knox, who also berated Argyll for his behaviour). Moray publicly backed his sister and occasionally offered her financial support, as did other members of his extended family and Jean’s friends, like Annabella Murray (Moray’s aunt and another of Queen Mary’s former ladies-in-waiting). Frustrated over her refusal to grant him the divorce he needed, Argyll now attempted to compel his wife to return to him through the courts, but she refused to do so, leaving both spouses, the Kirk, and the political community in a bind. After Moray’s assassination in early 1570, Jean lost an important source of support from a close family member, and though her distant cousin the earl of Atholl attempted to intercede for her with Argyll, a reconciliation still never materialised. Holding out for a much more substantial settlement from her husband, whom she described as ‘that ongrait man’, Jean, took up residence with her friend Annabella Murray (Countess of Mar and James VI’s ‘Minnie’) at Stirling, with the household of the young king James. At this time she seems to have been acutely aware that she lacked a network of support, being described as ‘very angry and in great poverty’, and her situation worsened over the next few years.

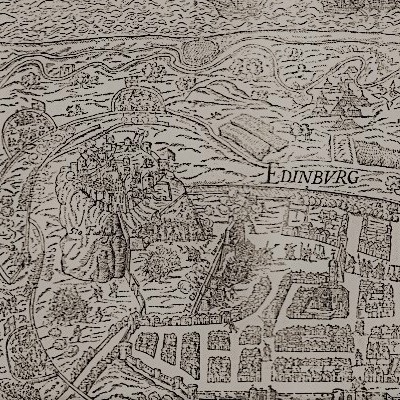

In the early 1570s, the balance began to shift in favour of Argyll, who had turned to the church courts for a solution. Kirk officials repeatedly censured Jean for non-adherence to her husband: she ignored all of these warnings. When she continued to disobey the direct orders of the Kirk, she was put to the horn (outlawed), and not long afterwards, with nowhere else to turn, she took refuge in Edinburgh Castle. The castle was then undergoing the ‘Lang Siege’, with William Kirkcaldy of Grange and his men holding the castle on behalf of Queen Mary against the Regent Morton, who then governed Scotland on behalf of Mary’s son the young King James VI. This siege has gone down in Edinburgh’s history as infamous, and forever changed the shape of the castle itself. The garrison held out for three years, taking potshots at both the supporters of the young King James and the capital city at large, minting coins in Mary’s name, and housing numerous members of the Queen’s Men, including Mary’s former secretary the ‘machiavellian’ William Maitland of Lethington, as well as many other dissidents who had entered the castle for various reasons, Jean included. Though her sentence of outlawry was briefly relaxed to allow her to appear in court, Jean refused to leave the castle and was excommunicated by the Kirk in April 1573.

By this time the Earl of Argyll had finally been won over by the ‘King’s Men’ and had exchanged his allegiance to Queen Mary for a position as chancellor in the government of James VI. This enabled him to get an act of parliament passed that allowed divorce for desertion and, finally, in June 1573, Argyll legally divorced his wife. This was a landmark decision in the history of Scots law, and while Jean never accepted the divorce, her tumultuous personal life did result in the emergence of the concept of ‘divorce by desertion’ and one of the first, and certainly most famous, divorces granted by the new reformed Church of Scotland. In desperate need of an heir, her ex-husband Argyll quickly remarried, but died only three months later in September 1573, with his posthumous son by his new wife dying at birth the next year.

Only a few weeks before Jean’s divorce was announced, Edinburgh Castle had finally surrendered, having been so thoroughly bombarded by English troops that David’s Tower and the Constable’s Tower, both roughly two hundred years old, collapsed in to the main entrance of the castle. Though most of the garrison were allowed to leave freely, Kirkcaldy of Grange and his brother were hanged at the mercat cross of Edinburgh along with the jewellers who had minted the coinage in Mary’s name. Maitland of Lethington died suspiciously in prison not long afterwards, possibly by his own hand. Jean, still afraid that she would be handed over to her husband, had written to Elizabeth I of England beseeching her protection, and in the meantime crossed the water to Fife, her mother’s native county. In time though, with her husband preoccupied with his remarriage and then dying soon after, Jean actually emerged in a stronger position. For the next decade or more she harassed her brother-in-law, the new earl of Argyll (who had married the Regent Moray’s widow Agnes Keith), for a settlement which would give her financial security, claiming her right as the late earl’s widow over his ‘pretendit’ second wife. She eventually won this case, receiving a handsome pay-out which supported her to the end of her life. She seems to have spent her later years living comfortably in Edinburgh, still describing herself as the Countess of Argyll. She was legitimated by the Crown in 1580, some decades after several of her half-brothers. She lived just long enough to hear of the execution of her younger sister Mary in 1587, but her thoughts on that infamous event must remain a mystery. By this point only Jean and her half-brother Robert, Earl of Orkney remained of James V’s acknowledged children: James of Kelso had died young in 1558, John Stewart succumbed to illness in 1563, the Regent Moray was shot in 1570, and now Mary had been beheaded. In January 1588, possibly aged about 55, Jean herself died in Edinburgh, ending her dramatic career a wealthy widow. She was buried in the royal vault at the Abbey of Holyrood, next to her father King James V.

Sources below cut or, since that ‘read more’ thing isn’t showing up much, you can access them at the bottom of this page

*’Certainly acknowledged’ means both the sons that James V supported during his lifetime and whose upbringing is recorded in the Treasurer’s Accounts, though probably there were other sons who were younger, while there may have been another daughter ‘Margaret’ but as she is only mentioned once and then ambiguously, it seems probable that this was just a typo for Jean.

Main sources include Jane Dawson’s article ‘The Noble and the Bastard’ in ‘Sixteenth Century Scotland: Essays in Honour of Michael Lynch’, eds. Goodare and MacDonald; Rosalind Marshall’s ‘Queen Mary’s Women’, and many primary sources (largely available online) including the Treasurer’s Accounts, the histories of people like Knox and Pitscottie, and various family papers.

#Jean Stewart Countess of Argyll#shoddy history gifsets#sixteenth century#Scottish history#Mary Queen of Scots#the Stewarts#women in history

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

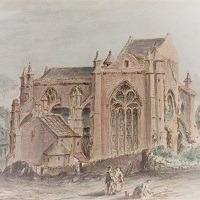

History Edits: Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scots

Born on 17th January 1433 in Grave, now in the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant, Mary of Guelders was the eldest of the surviving children of Arnold, Duke of Guelders (an area roughly approximating to modern-day Gelderland, but larger) and Catherine of Cleves. She was also the great-niece of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and it was due to this connection that in the duke arranged for her to be raised in the household of his wife Isabel of Portugal in 1442. The fifteenth century court of Burgundy was one of the most glittering and influential courts in western Europe and Mary would not only have been schooled in etiquette and courtly behaviour, but she would also have seen the formidable Duchess Isabel in action. It also appears to have been due to these Burgundian links that she was married to James II of Scotland in 1449, though the duchess and many other members of the Burgundian court wept when Mary departed from Bruges. The sumptuous wedding feast was thoroughly chronicled by Mathieu d’Escouchy, who attended along with several other notable figures from France and the Low Countries. Mary’s impressive dowry was provided by her great-uncle Philip the Good- who had no daughters of his own so used other female relatives to forge alliances- but it also came with the stipulation that she be kept in the style she was accustomed to, and soon enough Mary became a very rich woman- though sometimes indirectly as a result of her husband’s forfeitures of major nobles. Aside from her dowry, Mary’s marriage to James II was probably the reason why the great bombard Mons Meg- one of the largest cannons of its kind in history- was given to the king of Scots by Philip the Good. Scotland’s relationship with the Low Countries had always been important but Mary of Guelders’ marriage not only helped to bolster trade between the two, but also strengthened diplomatic relations with the dukes of Burgundy, as well as her homeland of Guelders. In later years, her second son Alexander, Duke of Albany, was to raised at his grandfather’s court of Guelders, and the family connections which the marriages of Mary and her husband’s sisters forged between the Stewarts and continental dynasties opened up important artistic and political channels for several generations after her death, not least during the reign of her son.

In her eleven years as queen consort Mary gave birth to upwards of seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood- Mary, Countess of Arran; the future James III; Alexander, Duke of Albany; John, Earl of Mar; and Lady Margaret Stewart. Her marriage was cut short suddenly in 1460, however, when one of her husband’s cannon exploded when he was standing nearby, and James died from blood loss soon after. At the time of his death he had been besieging Roxburgh Castle, formerly one of the most important castles in Scotland but which had been in English hands for around a century, and popular tradition has it that it was Mary who personally spurred on her husband’s troops to finish the job and take the castle, after which Roxburgh was razed to the ground and never rebuilt. She then acted as a regent (loosely) to her young son James III. While traditionally it was claimed that Mary was unstable and showed no aptitude for government, busying herself with taking a string of lovers instead, in more recent years these rumours- which were mostly the product of the political rivalries of James III’s minority- have been largely dispelled and her considerable political acumen and impact has been more widely acknowledged. In particular her foreign policy- previously thought of as ‘wayward’- actually seems to have been very intelligent, particularly when Mary protected Scotland’s interests during the civil war which was then disrupting Scotland’s neighbour England (i.e. the Wars of the Roses), and while she cautiously lent support to certain factions, she made sure not to overplay her hand and never inclined too much towards one party, in case it should endanger Scotland’s position. She did however on more than one occasion harbour the Lancastrian queen Margaret of Anjou, along with her husband Henry VI and young son, in Scotland. In 1461 a conference was held between the queens of Scotland and England at Lincluden, whereby it was agreed that the Scots would provide troops and support to the House of Lancaster, while Berwick-upon-Tweed would be returned to Scotland and Mary’s eldest daughter and namesake Mary Stewart would marry Margaret’s son, Edward Prince of Wales. This marriage never took place however, and Mary was eventually persuaded by her Burgundian relatives to drop the Lancastrian alliance, though she also rejected the marriage which was briefly proposed between herself and the Yorkist king Edward IV of England.

Mary also made an impact on domestic life in Scotland in several different ways. She has acquired a reputation as a builder, and her most notable projects included a new castle at Ravenscraig in Fife, which was the first castle in Scotland specifically built to withstand artillery fire, and also Trinity Collegiate Church in Edinburgh. This last project also displays Mary’s spiritual patronage (she was also later credited with having introduced the Observant Franciscans to Scotland) as well as her interest in music, and among other things she provided organs for the church’s use and stipulated that all the clerics were to be able to sing in matins.

Mary was eventually buried in Trinity Kirk when she died prematurely in December 1463, a month short of her 31st birthday, having been ill for some time. The kirk was eventually bulldozed to make way for Waverley Station, and it is unclear whether it was actually Mary’s body that was moved to Holyrood Abbey at this time or another unknown woman. In the fifteenth century however, she was mourned both in her homeland of Guelders and in Scotland. Mary had only been at the head of government for three years but in that time proved herself a capable administrator and strong ruler, whilst she had also made a notable contribution to Scotland’s international relations- both diplomatic and economic- and its religious life, as well as fostering its military strength and supporting new technology in an age where warfare was changing massively. She is still a very shadowy figure for all this, however, and the lack of information available about her life and world do not help us to dispel some of the older assumptions about her rule. We don’t even have any contemporary artistic portrayals of her. Nonetheless though she died relatively young and while she must remain a mysterious figure in many ways, Mary of Guelders was for a short time able to exercise an important influence in both Scotland and arguably even Britain as a whole, and her impact on mid fifteenth century Scotland should not be underestimated.

Read more about Mary here, here, and if looking for books here’s some good places to start x, x (pretty sure there’s much much cheaper versions elsewhere because these books are not usually so expensive but I just wanted to give the titles. Also this book is good for Guelders. And there are lots of primary sources online, including the account of Mary’s wedding by Mathieu d’Escouchy).

#Mary of Guelders#Scottish history#women in history#British history#fifteenth century#shoddy history gifsets#Guelders

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

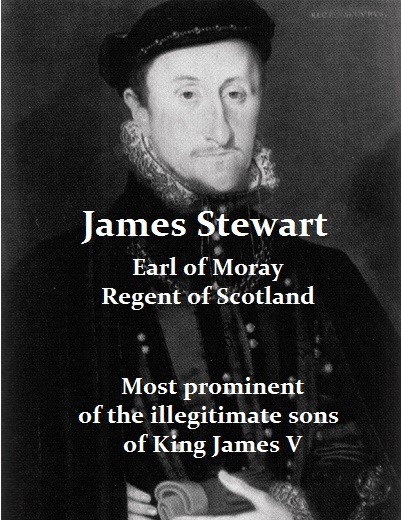

Shoddy History Edits:

The Regent Moray + Mary I of Scotland: Parallels and Contrasts

*I know there’s a typo re: Mary’s age at time of death, but it took ages to measure out the text and I can’t go back now. She hadn’t reached her 45th birthday at the time of her execution.

#Mary Queen of Scots#Regent Moray#Scottish history#the Stewarts#sixteenth century#They're maybe not the best parallel in the world but I felt I had to do this#shoddy history gifsets

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shoddy History Edits: The Women of the First War of Independence:

Marjorie Comyn, Countess of Dunbar made her contribution in the first few months of the conflict. Her husband was one of the few Scottish earls to adhere to Edward I of England rather than the Scottish Crown, and had left Marjorie in Dunbar Castle in his absence. Not long after, however, Dunbar came under siege by part of the Scottish army. Marjorie held out for a couple of days with only a small household and no proper garrison until she heard from some of her kinsmen that her husband was, in fact, supporting the English king (it should be remembered that Marjorie was the sister of John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, and the cousin of John Comyn of Badenoch, who were King John’s most important backers). At this she promptly changed her allegiance and held Dunbar Castle against her husband, who asked for an English army to retake it. Edward I provided this, and the English were soon laying siege to Dunbar themselves. A Scottish army was mustered to relieve Dunbar and the resulting clash between the two forces, known as the Battle of Dunbar and the first pitched battle of the Wars of Independence, was a disaster for the Scots with many important nobles being taken prisoner both on the field and in the castle. It is unclear what happened to Marjorie afterwards.

Agnes Comyn, Countess of Strathearn, another of the sisters of the Earl of Buchan, had a rather different experience of the war. Her husband Malise at first supported the patriotic cause, but eventually seems to have been worn down by the conflict and adhered to the English after the Battle of Falkirk. This situation did not alter after 1306 when Robert Bruce declared himself king- Bruce did so on the back of murdering Agnes’ cousin, an action which pushed many of the Comyns and their supporters in to the English camp, and he followed this up by kidnapping Agnes’ husband not long afterward, in an attempt to force his allegiance. Whether or not Malise gave this allegiance, it was almost certainly under compulsion, though he was still hauled before the English king to answer for his actions and imprisoned (honourably) in York for several years thereafter, his wife joining him there. He finally returned to Scotland to serve Edward II by holding Perth against Robert I in 1312, and when Perth fell he was stripped of his earldom. The title of Earl of Strathearn was instead given to Malise and Agnes’ son, also Malise, who, unlike his parents, remained a firm supporter of Robert Bruce throughout his career. Agnes’ husband died in their son’s custody a few years later, but it seems the countess herself still had work to do. Given Robert I’s persecution of her family and its supporters, particularly in Buchan which was brutally harried in 1308, Agnes had no reason to love the new king, even if her son remained his loyal supporter. She is named by John of Fordun as one of the conspirators in the Soulis conspiracy of 1320, which aimed to overthrow Robert I, and, given the identities of some of the other conspirators, it seems that Agnes may have been one of the ringleaders of the plot and was active in securing support from among her household and kin. She was imprisoned for this, presumably until the end of her life, though, like her sister Marjorie we have no record of the rest of her life.

Christina of the Isles or Christina of Garmoran was an heiress and important member of the MacRuairi kindred, one of the three major clans descended from the famous Somerled (the other two being the MacDougalls and the MacDonalds). As the only surviving legitimate daughter of the MacRuairi chief she was an important magnate on the western seaboard and in the isles, though we have considerably less information on her than we might like, which is unfortunately quite a typical state of affairs when it comes to noblewomen of the Gaelic world, even more so than their already under-documented Anglo-Norman counterparts. Nonetheless, when Robert Bruce fled into the west in 1306, Christina is supposed to have been one of the island nobles who sheltered him, with the chronicler John of Fordun going so far as to say that is was chiefly ‘by the help and power of a certain noble lady, Christiana of the Isles, who wished him well’ that Bruce was able to return to his earldom of Carrick. Christian, as well as her cousin Angus Og of Islay, provided Bruce with galleys and men in support of his claim, even when he seemed entirely defeated (hence the birlinn of the isles).

Isabella de Beaumont, more often known by her married name Isabella de Vesci, was initially the wife of John de Vesci, lord of Alnwick, a powerful landowner in the north of England. Both before and after her husband’s death in 1289 Isabella showed herself to be remarkably skilled at accumulating land and influence, becoming a major landowner in the north. This was helped along by her close friendship with Eleanor of Castile and, by extension, Edward I of England, which persisted even after Eleanor’s death in 1290. Edward I trusted Isabella with the keeping of at least two important royal castles in the north, appointing her governor of Scarborough and Bamburgh, a position never previously held by a woman in England. As the political situation got out of hand on the other side of the border, Isabella was thus naturally involved in the defence of her territories in the north of England, was granted the keeping of Scottish prisoners, and became interested in Scottish politics, assisted by several of her brothers, whom she had helped to gain prominent positions. Her brother Henry de Beaumont in particular benefited from his sister’s politicking, as Isabella secured for him the hand of Alice Comyn, the heiress to the earldom of Buchan, and in time she also arranged the marriage of Henry’s daughter Katherine to the young son of the late Earl of Atholl. In this way Isabella maneuvered her family into an influential position among the ‘Disinherited’ Scottish nobles, supporters of the Balliol claim and enemies of Robert Bruce, with the result that the de Beaumonts became heavily involved in both the First and Second Wars of Independence (though particularly the latter). She also became close to Isabella of France, though this resulted in her later falling out of favour with Edward II, especially when the war with Scotland began to go badly for the English king. When Queen Isabella was in France plotting to invade her husband’s kingdom, Isabella de Beaumont and her family members were already in revolt against the king, but later Isabella de Beaumont also fell out with Queen Isabella’s new government, especially over the peace treaty with Scotland. To this end she was involved in the Earl of Kent’s rebellion, but escaped imprisonment, and lived to see Edward III in turn overthrow his mother, and the Disinherited’s invasion of Scotland in support of Edward Balliol which started the ‘Second’ War of Independence, before her death in 1334.

Alianora de Louvain, Lady Douglas- even before war broke out, a kingless late thirteenth century Scotland could be dangerous for noblewomen, especially rich widows. In 1288-9, Alianora, the widow of William de Ferrers of Groby, was staying with Elena de Zusche at her manor of Tranent in East Lothian, having come north to receive her dower from her husband’s Scottish lands. At some point before late January of 1289, however, she was abducted by William ‘le Hardi’ Douglas and John Vicharde and carried off ‘into the interior of Scotland’. The Sheriff of Northumberland was commanded by Edward I of England to seize Douglas’ lands, and, along with the Guardians of Scotland, was instructed to arrest Douglas and Alianora should they be found. The Guardians do not seem to have been too eager to stir themselves in pursuit of Douglas, but nonetheless he had been taken prisoner by May of 1290, when he was released from Leeds Castle on the condition that he stand trial. Later upon paying a fine to the English king, William Douglas and Alianora were married, but it is unclear how she felt about the whole affair. I hesitate to agree with whoever edited Douglas’ wikipedia page and claimed that Alianora was “apparently not averse to the rough charms of her kidnapper”- whilst it is not necessarily inaccurate, and abduction in the Middle Ages was a far more complex crime than it is today, there is no real evidence for this speculation, and for all we know Alianora could have been making the best of a bad situation, or might have been party to the plan beforehand, or any number of possibilities. Whatever the case, the little evidence we have for their married life reveals no other drama, and Alianora appears to have played the role of the loyal noble wife to the best of her ability. When William Douglas was again censured by the English king for his role in the uprising of 1297, it is claimed by some sources that Alianora and her young stepson James Douglas (yes that one) were left in charge of Douglas Castle, and it was there that Robert Bruce, who had been sent to take the castle, changed sides to support the rebels. Alianora’s lands were also frequently mentioned as being seized alongside her husband when he was in rebellion, though this may simply have been to counteract the control he could exercise over his wife’s property, and after his death ibn the Tower of London in 1298, Alianora petitioned successfully for their return, engaging in no more acts of rebellion against the English king. Nonetheless, as well as being the wife of a prominent figure in the irststages of the Wars of Independence, she provides an interesting example of both the responsiblities and dangers faced by a noblewoman of her period in her own right.

Euphemia, Countess of Ross is one of many obscure Scottish noblewomen who nonetheless stepped into the political arena during the Wars of Independence, acting as the head of the kindred and governing their husbands’ lands during his absence. Euphemia is thought to have been a daughter of Hugh de Barclay, and was married to Uilleam, Earl of Ross. During her husband’s captivity in England during the late 1290s, Euphemia seems to have taken charge of the family’s fortunes, with the support of her sons. She worked conscientiously for her husband’s release, attempting to appease Edward I and also gaining the support of many prominent members of the Scottish political community in this. Meanwhile, she promised to keep the English king’s peace in Ross, keeping him informed of the rebellion of Andrew Moray in 1297, and personally undertaking to provision and assemble an army which her son was to lead against the rebels in that year. Euphemia thus stands as an example of the often shadowy figures who were forced, often through the absence of husbands or sons- whether as a result of death or captivity- to keep things running smoothly at home and work for the return of their husbands by whatever means possible.

Margaret of France, Queen of England, was the second wife of Edward I of England, and, at the age of twenty, around forty years younger than her husband, a ruthless and formidable conqueror with decades of political and military experience, who had lost his beloved first wife nine years before. Nonetheless genuine affection seems to have existed in the marriage and Margaret, on her own initiative, decided to join her husband on campaign in Scotland, which is supposed to have greatly pleased Edward. She was present at the siege of Stirling, among other engagements, and along with her ladies viewed the spectacle and the feats of arms of her husband and his army in the best chivalric tradition (though whether the presence of the queen inspired the knights to greater deeds in the style of Arthurian legend is less certain). She also accompanied Edward on his final campaign in 1307, but the English king died before reaching Scotland, after which, though she was still young, Margaret refused to remarry, allegedly stating that ‘when Edward died, for me, all men died with him.’

Elizabeth de Burgh, Queen of Scots, was an Anglo-Irish noblewoman who became the second wife of Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, in 1302. Four years later, when her husband proclaimed himself king at Scone, she also became Queen of Scots, but her husband’s reign had hardly begun when he was defeated at the Battle of Methven and his supporters forced to flee. Queen Elizabeth, along other important women of Bruce’s family and following, was conveyed north by her brother-in-law Neil Bruce and the earl of Atholl, initially taking shelter in Kildrummy Castle in Aberdeenshire. However when it became clear that Kildrummy was going to be besieged by an English army, the queen and her ladies, along with Atholl, went further north still, probably intending to reach Orkney and then perhaps Norway, where Isobel Bruce, her husband’s sister, was queen dowager. Unfortunately, the small party was betrayed and captured in the chapel of St Duthac in Tain by the Earl of Ross, and handed over to the wrath of Edward I of England. As the daughter of Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, who had remained a supporter of the English king despite his son-in-law’s claims, Elizabeth fared better than some of the other ladies- and certainly better than Atholl, who wasn’t even given the dignity of beheading and was hanged on Edward’s orders. Nonetheless she remained a prisoner, in conditions which were often unfriendly and sometimes filthy, until her husband’s victory at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. We know little of Elizabeth’s life as a queen, despite her husband’s fame, though she had at least four children, three of whom survived to adulthood- Margaret, Matilda, and finally David, King Robert’s long-hoped for son and heir being born in 1324. She was also stepmother to Robert’s eldest legitimate daughter Marjorie Bruce, who was in the company of the queen at Kildrummy and Tain and was similarly imprisoned in England, but we have little indication of their relationship. Elizabeth died in 1327, two years before her husband, leaving her children motherless at a young age, not least David, who was only an infant and proclaimed king at the age of five.

Isabella of France, Queen of England- is well-known for her role in English history, though (fortunately) her involvement in the Scottish Wars of Independence has nothing in common with her storyline in Braveheart, even when she accompanied her husband on campaign on several occasions, including in 1314. Nonetheless, she was on several occasions forced to deal with the realities of a conflict which went increasingly badly for England during her husband’s reign, with the result that, by the late 1320s, Scottish invasions of the north of England were certainly far more common and successful than attempts at English conquest. In 1319, for example, she was forced to decamp hastily from York when the forces of Sir James Douglas made a raid in the area, which was rumoured to have been intended to capture the queen. A few years later, Isabella, once again came close capture when Bruce, Randolph, and Douglas routed English forces near Rievaulx Abbey, where her husband had been staying at the time, and chased him all the way to the gates of York. Meanwhile, as a result of the Scottish invasion, Isabella herself, who had been staying at Tynemouth priory, was now in the middle of territory that lay behind the Scots’ advance, and it is alleged that she was once again nearly captured as she escaped from the area, coming uncomfortably close to the army itself. It is unclear how she actually escaped, given that the land was swarming with the Scots and the sea with Flemish mercenaries, but there is no doubt that being forced to flee once again was humiliating for the queen. Nonetheless, after overthrowing her husband and taking control of England’s government in 1326, it soon became clear that defeating the Scots was no easier than it had been four years before, and, after the failure of the Weardale Campaign, the English government under Isabella and Roger Mortimer sued for peace in the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton. This treaty recognised Robert I as king of an independent Scotland, and sealed the bargain by marrying Isabella’s daughter Joan to the young David Bruce. Nonetheless, the treaty was declared a ‘shameful peace’ in England, while the anger of the London mob prevented the return of the Stone of Scone, and war would break out again in 1332, though by this time Isabella had been firmly removed from government by her son Edward III.

Christiana of Esperstoun is kind of the odd one out on this list. Unlike the other ladies, she did not choose a political camp during the Wars of Independence and nor did she take part in events of national importance (or at least, if she did, this information has not been passed down to us today). In fact her experiences were local and personal, and, though they were exacerbated by the political uncertainties of late thirteenth century Scotland and the war-torn Lothian countryside, they might have happened at any time. Her story is more interesting (if also a misery-fest) as the unusually well-preserved tale of an ordinary woman (not a noblewoman, again unlike the other ladies on this list) who stood up to men far more powerful than herself in order to protect her heritage, rights, and family. As her father’s only child, Christiana inherited a small parcel of land in the hamlet of Esperston (now little more than three or four spread out houses near the village of Gorebridge in Midlothian). However, her husband, William, by later accounts ‘a man more given to ease than labour’ alienated this piece of land to the local house of the Templars for his lifetime only, in return for his maintenance by them. In the meantime Christiana and her three sons remained in a cottage on this land, but in poverty, and with little security of tenure. When her husband died some time around 1296, she might have expected to at least regain her land but instead, Brian le Jay, the Master of the Templars in Scotland (and a noted supporter of Edward I, hence there may be a little bias against him in later accounts but we cannot know) turned up with several of his followers in order to have her driven out, claiming that her husband had made a permanent alienation. Christiana of course denied that her husband had ever done so or even had the right do so, and clung to the door of her home when the Master of the Templars ordered his men to forcibly remove her. When they could not drag her away, one of le Jay’s followers cut her finger off with a knife and thus Christiana was removed, ‘sobbing and shrieking, from her home and heritage’. Despite suffering mutilation and eviction however, Christiana was not yet beaten, and, eventually gaining an audience with the king at Newbattle (probably Edward I rather than John), managed to have her lands restored after a full inquiry was held, though le Jay seems to have got off lightly. However, the next few years saw increased conflict in Scotland as the War of Independence got into full swing, and the Master of the Templars was able to take advantage of the breakdown in law and order and once again evict her. When Christiana’s eldest son heard of this he returned home to help his mother, but was murdered by a band of Welsh mercenaries that le Jay had hired in preparation for the Battle of Falkirk. It would take many more years before Christiana’s second son William was able to regain his mother’s land for the family, but, though he himself died without heirs of his body, his mother’s bravery and defiance were preserved in a record of an inquiry into the land’s ownership in 1354, and plainly remembered by the local community.

Joanna de Clare, Countess of Fife was another woman who became uncomfortably aware of the problems in establishing law and order in Scotland during the late 1290s. Joan was the daughter of Gilbert ‘the Red’ de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, as well as widow to Duncan, Earl of Fife, who was murdered in 1289, and perhaps also mother of Isabella, Countess of Buchan. Perhaps unsurprisingly, when the Wars of Independence broke out she was a reasonably wealthy woman who, for the most part, remained on good terms with Edward I of England. The English king naturally considered it his business if such an important noblewoman remarried and extracted a promise from Joan not to do so without his permission, but it may have slipped their minds that wealthy widows were particularly vulnerable to kidnap and forced marriage in the thirteenth century. In 1299 she brought charges against Herbert de Morham, a Scottish nobleman who had ambushed her retinue on the road between Stirling and Edinburgh and carried her off to his brother’s castle. Joanna refused to marry him, however, as a result of her oath to Edward I, and so de Morham imprisoned her and seized her goods to the tune of two thousand pounds. Joanna seems to have been released and brought legal action against her captor, but she nonetheless found herself heavily in debt as a result of the goods he had stolen. Later during the war (1317), and despite her usual loyalty to the English Crown, Joanna is listed as being in rebellion along with her second husband, both of them supporting her son the young Earl of Fife against the English.

Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan was the daughter of an Earl of Fife, and wife to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan (the brother of Marjorie and Agnes Comyn, mentioned above). Though little is known of her early life, she made history in 1306 when, hearing that Robert Bruce intended to have himself crowned King of Scots at Scone, she broke with her husband (whose cousin Bruce had recently murdered) and quit his house. Riding to Scone she arrived too late for the coronation but nonetheless demanded to fulfill the traditional role of the earls of Fife in installing the new king on his throne, as the earl- either her nephew or more likely brother- was then captive in England. A second coronation was thus held at which Isabella carried out this important tradition. Unfortunately Bruce’s first year as king was not particularly successful and Isabella was soon forced to flee north with the queen and several other ladies. She was captured at Tain by the Earl of Ross and handed over to the English. One source claims that her husband demanded her execution but instead she ended spending the next seven years imprisoned in a cage which was suspended from the walls of Berwick castle, open to the elements. She was finally removed from this harsh imprisonment in 1313, but does not appear in any prisoner exchanges after Bannockburn, suggesting that she may have died by this time. You can read more about her here.

Christian Bruce, Lady Seton, Lady Moray, and perhaps also Countess of Mar was one of the many sisters of King Robert I. Her first (arguably second) husband, Christopher Seton, was a close follower of her brother and, like many of Bruce’s male followers, including Christian’s other brothers Thomas, Alexander, and Neil, he was hanged in 1306. Christian herself was one of the ladies captured at Tain and was held in close confinement in the nunnery of Sixhills, Lincolnshire, until after the Battle of Bannockburn. She later married the Guardian of Scotland, Andrew Moray (posthumous son of William Wallace’s less well-known co-commander of the same name). During the Second War of Independence she successfully defended Kildrummy Castle, which years earlier her brother Neil had defended unsuccessfully prior to his execution and which was then one of the few castles in Scotland still in Bruce hands, against the forces of David of Strathbogie, until Moray’s army defeated Strathbogie’s at the Battle of Culblean and relieved the castle. Christian lived a long life and died in 1357, being buried in the royal abbey of Dunfermline with much honour.

Mary Bruce, another of Robert Bruce’s sisters, was less fortunate than Christian after being captured at Tain. Like Isabella of Fife she was kept for several years in deplorable conditions in a cage which was suspended outside Roxburgh Castle. The reason for her ill treatment by comparison with her sister is unclear- Isabella of Fife's defiance of both her husband and Edward I of England is well documented but we have no record of what Mary’s crime was, if she committed any such act of defiance at all. She was released after Bannockburn and was later married to Sir Neil Campbell, Mac Cailein Mór.

Marjorie Bruce- the only child of Robert Bruce by his first wife, Isabella of Mar, in 1306 Marjorie was around twelve years old and her father’s only legitimate child. She was captured along with her stepmother and aunts at Tain and duly imprisoned in England. It seems that the young Marjorie was initially intended for a similar cage to those of her aunt Mary and Isabella of Fife, which was to be placed in the Tower of London, but for whatever reason this punishment was relaxed and she was instead sent to a nunnery in Lincolnshire. Having spent most of her teenage years in captivity, she returned to Scotland after the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, and, the next year, was married to ‘the Good Sir Walter’, the High Steward, by whom she had one surviving child, a son named Robert. Unfortunately Marjorie would not enjoy freedom for very long and died in 1316, possibly from complications surrounding a second childbirth. However her posthumous legacy ensured her name would live on- fifty-five years later, her son ascended the Scottish throne as King Robert II, and thus founded the Stewart dynasty, who ruled Scotland for several centuries thereafter.