#Isabella of Fife

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

15th January 1803 saw the birth of Marjory Fleming at Kirkcaldy.

Marjory "Pet" Fleming was an extraordinary child prodigy, left poems, letters and a journal that are now one of the treasures of the National Library of Scotland; and in 1889 Sir Leslie Stephen, Virginia Woolf's father, wrote an entry about her for the original Dictionary of National Biography, believing that 'no more fascinating infantile author has ever appeared. What makes this all the more remarkable is, Marjory was a mere 8 years old when she died.

A distant relative and said to be admired by Sir Walter Scott, although there is no real evidence they ever met Robert Louis Stevenson and Mark Twain also thought highly of her, Marjory Fleming was a child prodigy poet.

Marjory spent most of her sixth, seventh and eighth years in Edinburgh being tutored by her teenage cousin, Isabella Keith. Isabella is mentioned is the somewhat odd opening line of Marjory’s famous journal: ‘Many people are hanged for Highway robbery Housebreking Murder &c. &c. Isabella teaches me everything I know and I am much indebted to her she is learnen witty & sensible.’

Marjory returned to Kirkcaldy in July 1811, but wrote on 1 September to her cousin, ‘We are surrounded with measles at present on every side’. She herself contracted measles in November and although she apparently recovered, died in December from what is now thought to have been meningitis. She was a month short of her ninth birthday.

Marjory was an accomplished and witty poet and diarist although she was not published until 50 years after her death. Her writings became hugely popular in the Victorian period albeit with the published editions severely altered as some her her language was thought inappropriate for an eight year old. The first account of her was given by a London journalist in the Fife Herald and reprinted as a booklet entitled Pet Marjorie: a Story of Child Life Fifty Years Ago. The nickname ‘Pet’ and the spelling of her name with ‘ie’ were inventions of her biographer: both appear on Marjory’s gravestone in Abbotshall Kirkyard, Kirkcaldy erected in 1930.

Marjory’s precocious intellect is noted in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: ‘She records enjoying the poems of Pope and Gray, the Arabian Nights, Ann Radcliff’s ‘misteris [sic] of udolpho’, the Newgate calendar, and ‘tails’ by Maria Edgworth and Hannah More.’ Her abilities are also apparent in the pithy comments in her journal and in her valiant attempts to write in rhyming couplets.

Robert Louis Stevenson is quoted as saying, ‘Marjory Fleming was possibly – no, I take back possibly – she was one of the noblest works of God.’

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey people, I'm bored, and I'm still doing the comic, Anyone wanna voice my characters for 'The Ink Chronicles'

Voice Actors I need (There are voice actors that are already used so I will tag them):

Careen Jewel: N/A

Barbara Wilton: @littleearthlings0505 (If your still there)

Cardi Porco: N/A

Gaudy Bogus: N/A

Ewe Sata: @oddlyvoid

Ramee Delram: N/A

Viola Ayden: N/A

Bozo Boom Boom: N/A

DJ 'Marina’ Beastmode: N/A

Jim Millers: N/A

Bruice Ambrose: N/A

Wyatt Collymore: N/A

Nih Ajal: N/A

Riedairth Cadhe: N/A

Shadwo Clark: N/A

Indiana Everette: N/A

Cappella Fife: N/A

Alicla Blaaster: N/A

Kail Cooper: N/A

Ova Crawford: N/A

Ie Pikari: N/A

Maisy Austin: N/A

If you have a PC or a laptop, Tag me!!!

If you can’t figure out how to do these voices go to @littleearthlings0505 (Isabella Mireles Gamers) She’s great at Voice Acting!!!!

And also I'm doing Chapter 1 of the ink chronicles so YAY!!!!!!

Go to @the-ink-chronicles to read it! And there will be uploads!!!!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whisky Kingsbarns Balcomie

Whisky Kingsbarns Balcomie American Oak Oloroso Sherry Kingsbarns Balcomie è un single malt della distilleria della famiglia Wemyss, nella contea di Fife. È stato distillato utilizzando solo orzo locale e maturato al 100% in botti ex-Oloroso American Oak Sherry Butts di Jerez. Precedentemente utilizzate per la maturazione dello Sherry. Queste botti sono state specificamente scelte da Isabella…

0 notes

Photo

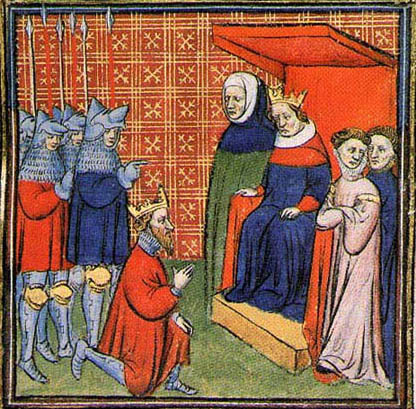

She was only in it for thirty seconds but absolutely any portrayal of Isabella of Fife was still worth watching that movie for

#Isabella of Fife#The Outlaw King as an Interested Party#Scottish history#period drama#Outlaw King#I am such a nerd and I'm not even that embarassed

727 notes

·

View notes

Photo

notable non-royal scottish women

requested by anonymous in honor of st.andrew’s day

#history#historyedit#weloveperioddrama#perioddramaedit#Scottish history#14th century#black agnes#black agnes randolph#agnes countess of dunbar#grizel baillie#17th century#18th Century#muriel spark#20th Century#deborah kerr#isabella of fife#flora macdonald#joanna baillie#19th Century#elizabeth melville#16th century#geillis duncan#gillis duncan#Aithbhreac inghean Corcadail#our edits#by julia#15th century

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

2nd January 1264: Marriage and Murder in Mediaeval Menteith

(Priory of Inchmahome, founded on one of the islands of Lake of Menteith in the thirteenth century)

On 2nd January 1264, Pope Urban IV despatched a letter to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline, commanding them to enquire into a succession dispute in the earldom of Menteith. Situated in the heart of Scotland, this earldom stretched from the graceful mountains and glens of the Trossachs, to the boggy carseland west of Stirling and the low-lying Vale of Menteith between Callander and Dunblane. The earls and countesses of Menteith were members of the highest rank of the nobility, ruling the area from strongholds such as Doune Castle, Inch Talla, and Kilbryde. Perhaps the best-known relic of the mediaeval earldom is the beautiful, ruined Priory of Inchmahome, which was established on an island in Lake of Menteith by Earl Walter Comyn in 1238. Walter Comyn was a powerful, if controversial, figure during the reigns of Kings Alexander II and Alexander III. He controlled the earldom for several decades after his marriage to its Countess, Isabella of Menteith, but following Walter’s death in 1258 his widow was beset on all sides by powerful enemies. These enemies even went so far as to capture Isabella and accuse her of poisoning her husband. The story of this unfortunate countess offers a rare glimpse into the position of great heiresses in High Mediaeval Scotland, revealing the darker side of thirteenth century politics.

Alexander II and Alexander III are generally remembered as powerful monarchs who oversaw the expansion and consolidation of the Scottish realm. During their reigns, dynastic rivals like the MacWilliams were crushed, regions such as Galloway and the Western Isles formally acknowledged Scottish overlordship, and the Scottish Crown held its own in diplomacy and disputes with neighbouring rulers in Norway and England. Both kings furthered their aims by promoting powerful nobles in strategic areas, but it was also vital to harness the ambition and aggression of these men productively. In the absence of an adult monarch, unchecked magnate rivalry risked destabilising the realm, as in the years between 1249 and 1262, when Alexander III was underage.

(A fifteenth century depiction of the coronation of Alexander III. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Walter Comyn offers a typical picture of the ambitious Scottish magnate. Ultimately loyal to the Crown, his family loyalties and personal aims nonetheless made him a divisive figure. A member of the powerful Comyn kindred, he had received the lordship of Badenoch in the Central Highlands by 1229, probably because of his family’s opposition to the MacWilliams. In early 1231, he was granted the hand of a rich heiress, Isabella of Menteith. In the end, there would be no Comyn dynasty in Menteith: Walter and Isabella had a son named Henry, mentioned in a charter c.1250, but he likely predeceased his father. Nevertheless, Walter Comyn carved out a career at the centre of Scottish politics and besides witnessing many royal charters, he acted as the king’s lieutenant in Galloway in 1235 and became embroiled in the scandalous Bisset affair of 1242.

When Alexander II died in 1249, Walter and the other Comyns sought power during the minority of the boy king Alexander III. They were opposed by the similarly ambitious Alan Durward and in time Henry III of England, the attentive father of Alexander III’s wife Margaret, was also dragged into the squabble as both sides solicited his support in order to undermine their opponents. Possession of the young king’s person offered a swift route to power, and, although nobody challenged Alexander III’s right to the throne, some took drastic measures to seize control of government. Walter Comyn and his allies managed this twice, the second time by kidnapping the young king at Kinross in 1257. They were later forced to make concessions to enemies like Durward but, with Henry III increasingly distracted by the deteriorating political situation in England, the Comyns held onto power for the rest of the minority. However Walter only enjoyed his victory for a short while: by the end of 1258, the Earl of Menteith was dead.

Walter Comyn had dominated Scottish politics for a decade, and even if, as Michael Brown suggests, his death gave the political community some breathing space, this also left Menteith without a lord. As a widow, Countess Isabella theoretically gained more personal freedom, but mediaeval realpolitik was not always consistent with legal ideals. In thirteenth century Scotland, the increased wealth of widows made them vulnerable in new ways (not least to abduction) and, although primogeniture and the indivisibility of earldoms were promoted, in reality these ideals were often subordinated to the Crown’s need to reward its supporters. Isabella of Menteith was soon to find that her position had become very precarious.

At first, things went well. Although one source claims that many noblemen sought her hand, Isabella made her own choice, marrying an English knight named John Russell. Sir John’s background is obscure but, despite assertions that he was low born, he had connections at the English court. Isabella and John obtained royal consent for their marriage c.1260, and the happy couple also took crusading vows soon afterwards.

But whatever his wife thought, in the eyes of the Scottish nobility John Russell cut a much less impressive figure than Walter Comyn. The couple had not been married long before a powerful coterie of nobles descended on Menteith like hoodie-crows. Pope Urban’s list of persecutors includes the earls of Buchan, Fife, Mar, and Strathearn, Alan Durward, Hugh of Abernethy, Reginald le Cheyne, Hugh de Berkeley, David de Graham, and many others. But the ringleader was John ‘the Red’ Comyn, the nephew of Isabella of Menteith’s deceased husband Walter, who had already succeeded to the lordship of Badenoch. Even though Menteith belonged to Isabella in her own right, Comyn coveted his late uncle’s title there. Supported by the other lords, he captured and imprisoned the countess and John Russell, and justified this bold assault by claiming that the newlyweds had conspired together to poison Earl Walter. It is unclear what proof, if any, John Comyn supplied to back up his claim, but the couple were unable to disprove it. They were forced to surrender all claims to Isabella’s dowry, as well as many of her own lands and rents. A surviving charter shows that Hugh de Abernethy was granted property around Aberfoyle about 1260, but it seems that the lion’s share of the spoils went to the Red Comyn, who secured for himself and his heirs the promise of the earldom of Menteith itself.

Isabella and her husband were only released when they promised to pass into exile until they could clear their names before seven peers of the realm. John Russell’s brother Robert was delivered to Comyn as security for their full resignation of the earldom. Having ‘incurred heavy losses and expenses’, which certainly stymied their crusading plans, they fled.

In a letter of 1264, Pope Urban IV described the couple as ‘undefended by the authority of the king, while as yet a minor’. However, though Alexander III was technically underage in 1260, he was now nineteen and could not be ignored entirely. Michael Brown suggests that Isabella and her husband may have been seized when the king was visiting England, and that John Comyn’s unsanctioned bid for the earldom of Menteith may explain why Alexander cut short his stay in November 1260 and hastily returned north, leaving his pregnant queen with her parents at Windsor. Certainly, Comyn was forced to relinquish the earldom before 17th April 1261. But instead of restoring Menteith to its exiled countess, Alexander settled the earldom on another rising star: Walter ‘Bailloch’ Stewart, whose wife Mary had a claim to Menteith.

Mary of Menteith is often described as Isabella’s younger sister, although contemporary sources never say so and some historians argue that they were cousins. Either way, Alexander’s decision to uphold her claim was probably as much influenced by her husband’s identity as her alleged birth right. Like Walter Comyn, Walter Bailloch (‘freckled’), belonged to an influential family as the brother of Alexander, Steward of Scotland. From their origins in the royal household, the Stewarts became major regional magnates, assisting royal expansion in the west. The promising son of a powerful family, Walter Bailloch was sheriff of Ayr by 1264 and likely fought in the Battle of Largs in 1263. In 1260 Alexander III had the opportunity to secure Walter’s loyalty as the royal minority drew to a close. Conversely John Comyn of Badenoch found himself out of favour and was removed as justiciar of Galloway following the Menteith incident. The king would not alienate the Comyns permanently, but for now, the stars of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith were in the ascendant.

(Loch Lubnaig, in the Trossachs, another former possession of the earls of Menteith)

Isabella of Menteith and John Russell had not been idle in the meantime. Travelling to John’s home country of England, they probably appealed to Henry III. In September 1261, the English king inspected documents relating to a previous dispute over the earldom of Menteith. On that occasion, two brothers, both named Maurice, had their differences settled before the future Alexander II at Edinburgh in 1213. The elder Maurice, who held the title Earl of Menteith and was presumed illegitimate by later writers (though this is never stated), resigned the earldom, which was regranted to Maurice junior. In return the elder Maurice received some towns and lands to be held for his lifetime only, and the younger Maurice promised to provide for the marriage of his older brother’s daughters.

It is probable that Isabella was the daughter of the younger Maurice, and that she produced these charters as proof of her right to the earldom. Perhaps Mary was her younger sister, but it seems likelier that Isabella would have wanted to prove the younger Maurice’s right if Mary was a descendant of the elder brother, and therefore her cousin. However despite Henry III’s formal recognition of the settlement, he did not provide Isabella with any real assistance: for whatever reason, the English king was either unable or unwilling to press his son-in-law the King of Scots on this matter. Isabella then turned instead to the spiritual leader of western Europe- Pope Urban IV.

(A depiction of the coronation of Henry III of England, though in fact the English king was only a child when he was crowned. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A long epistle which the pope sent to several Scottish prelates in January 1264 has survived, revealing much about the case. Thus we learn that Urban was initially moved by Isabella and her husband’s predicament, perhaps especially so since they had taken the cross. Accordingly, he had appointed his chaplain Pontius Nicholas to enquire further and discreetly arrange the couple’s restoration. Pontius was to journey to Menteith, ‘if he could safely do so, otherwise to pass personally to parts adjacent to the said kingdom, and to summon those who should be summoned’. But Pontius’ mission only hindered Isabella’s suit. According to Gesta Annalia I, the papal chaplain got no closer to Scotland than York. From there he summoned many Scottish churchmen and nobles to appear before him, and even the King of Scots himself. This merely antagonised Alexander III and his subjects. Although Alexander maintained good relations with England and the papacy throughout his reign, he had a strong sense of his own prerogative and did not appreciate being summoned to answer for his actions, especially not outwith his realm and least of all in York. Special daughter of the papacy or not, Scotland’s clergy and nobility supported their king and refused to compear. Faced with this intransigence, Pontius Nicholas placed the entire kingdom under interdict, at which point Alexander retaliated by writing directly to the chaplain’s boss, demanding Pontius’ dismissal from the case.

Urban IV swiftly backpedalled. In a conciliatory tone he claimed that Pontius was guilty of ‘exceeding the terms of our mandate’ and causing ‘grievous scandal’. To remedy the situation, and avoid endangering souls, the pope discharged his responsibility over the case to the bishops of St Andrews and Aberdeen, and the Abbot of Dunfermline. Thus the pope washed his hands of a troublesome case, the Scottish king’s nose could be put back in joint, and Isabella’s suit was transferred to men with great experience of Scottish affairs, who should have been capable of satisfactorily resolving the matter. However, there is no indication that Isabella was ever compensated for the loss of her inheritance, and when the dispute over Menteith was raised again ten years later, the countess was not even mentioned (probably she had since died). Possibly her suit was discreetly buried after it was transferred to the Scottish clerics, a solution which, however frustrating for the exiled countess, would have been convenient for the great men whose responsibility it was to ensure justice was done.

(Doune Castle- the earliest parts of this famous stronghold probably date to the days of the thirteenth century earls of Menteith, although much of the work visible today dates from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries)

The Comyns could not be dismissed so easily. Never resigned to losing Menteith, John Comyn of Badenoch claimed the earldom again c.1273, on behalf of his son William Comyn of Kirkintilloch. William had since married Isabella Russell, daughter of Isabella of Menteith by her second husband.* The 1273 suit was unsuccessful but William Comyn and Isabella Russell did not lose hope, and in 1282, William asked Edward I of England to intercede for them with the king of Scots. In 1285, with William’s father John Comyn long dead, Alexander III finally offered a compromise. Walter Bailloch, whose wife Mary may have died, was to keep half the earldom and he and his heirs would bear the title earl of Menteith. William Comyn and Isabella Russell received the other half in free barony, and this eventually passed to the offspring of Isabella’s second marriage to Sir Edward Hastings. Perhaps this could be seen as a posthumous victory for Isabella Russell’s late parents, but their descendants would never regain the whole earldom (except, controversially, when the younger Isabella’s two sons were each granted half after Edward I forfeited the current earl for supporting Robert Bruce).

Conversely, Walter Bailloch’s descendants remained at the forefront of Scottish politics. He and his wife Mary accompanied Alexander III’s daughter to Norway in 1281, and Walter was later a signatory to both the Turnberry Band and the Maid of Norway’s marriage negotiations. He also acted as a commissioner for Robert Bruce (grandfather to the future king) during the Great Cause. He had at least three children by Mary of Menteith and their sons took the surname Menteith rather than Stewart. The descendants of the eldest son, Alexander, held the earldom of Menteith until at least 1425. The younger son, John, became infamous as the much-maligned ‘Fause Menteith’ who betrayed William Wallace, although he later rose high in the service of King Robert I. Walter Bailloch himself died c.1294-5, and was buried next to his wife at the Priory of Inchmahome on Lake of Menteith, which Walter Comyn had founded over fifty years previously. The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith can still be seen in the chapter house of the ruined priory: the worn faces are turned towards each other and each figure stretches out an arm to embrace their spouse in a lasting symbol of marital affection.

(The effigies of Walter Bailloch and Mary of Menteith at Inchmahome Priory, which was founded by Walter Comyn in 1238 and was perhaps intended as a burial site for himself and his wife Isabella of Menteith. Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The dispute over Menteith saw a prominent noblewoman publicly accused of murder and exiled, and even sparked an international incident when Scotland was placed under interdict. For all this, neither Isabella of Menteith nor John Comyn of Badenoch triumphed in the long term. Even Walter Bailloch eventually had to accept the loss of half the earldom after holding it for over twenty years. In the end the only real winner seems to have been the king. Although at first sight the persecution of Isabella and her husband looks like a classic example of overmighty magnates taking advantage of a breakdown in law and order during a royal minority, Alexander III was not a child and his rebuke of John Comyn did not result in any backlash against the Crown. Most of the Scottish nobility fell back in line once the king came of age, but the king in turn had to ensure that he was able to reward key supporters if he wanted to expand the realm he had inherited. Although it was important to both Alexander III and his father that primogeniture and were accepted by their subjects as the norm, in practice both kings found that they had to bend their own rules to ensure that the system worked to their own advantage. The thirteenth century is often seen an age of legal development and state-building, but these things sometimes came into conflict with each other, and even the most successful kings had to work within a messy system and consider the competing loyalties and customs of their subjects.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Vetera Monumenta Hibernorum et Scotorum”, Augustinus Theiner (a printed version of Urban IV’s original Latin epistle may be found here)

- “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, vol. 2, ed. W.F. Skene (this is an English translation of the chronicle of John of Fordun, made when Gesta Annalia I was still believed to be his work. It provides an independent thirteenth or fourteenth century Scottish account of the Menteith case

- “The Red Book of Menteith”, volumes 1+2, ed. Sir William Fraser

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, volumes 1, 2, 3 & 5, ed. Joseph Bain

- “The Political Role of Walter Comyn, earl of Menteith, during the Minority of Alexander III of Scotland”, A. Young, in the Scottish Historical Review, vol.57 no.164 part 2 (1978).

- “Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy, 1204-1296″, M.A. Pollock

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371″, Michael Brown

As ever if anyone has a question about a specific detail or source, please let me know! I have a lot of notes for this post, so hopefully I should be able to help!

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#thirteenth century#women in history#Menteith#earldom of Menteith#Isabella Countess of Menteith#John Russell#John Comyn I of Badenoch#Alexander III#Henry III#Pope Urban IV#Walter Bailloch#the Stewarts#House of Dunkeld#House of Canmore#Mary of Menteith#inchmahome priory

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Walker

Walker Variants: Waker

• Current frequencies: GB 133929, Ireland 4922

• GB frequency 1881: 98570

• Main GB location 1881: widespread: esp. in N England, the Midlands, and Scotland

• Main Irish location 1847–64: widespread: esp. Ulster

English, Scottish: occupational name for a fuller, from Middle English and Older Scottish walker (Old English wealcere ) ‘one who trampled cloth in a bath of lye or kneaded it, in order to strengthen it’. Compare Fuller and Tucker.

Early bearers: England

Richard le Walkere, about 1248 in Bec Abbey Documents (Warwicks); Robert le Walker, 1260 in Assize Rolls (Yorks); Nicholaus Walker, 1377 in Poll Tax (Sheepy Parva, Leics); Johannes Walker, 1377 in Poll Tax (Scamblesby, Lincs); Adam Walker, 1377 in Poll Tax (Rothbury, Northumb); Willelmus Walker, 1377 in Poll Tax (Ellerton with Stainton, NR Yorks); Thomas Walker’, 1377 in Poll Tax (Slaughterford, Wilts); Hugo Walker, 1377 in Poll Tax (Worcester, Worcs); Johannes Walker, 1379 in Poll Tax (Lonsdale wapentake, Lancs); Johannes Walker’, 1379 in Poll Tax (Prescote, Oxon); Thomas Walker’, 1379 in Poll Tax (Warwicks); Willelmo Walkar’, 1379 in Poll Tax (Ormside, Westm); Alanus Walkar, 1379 in Poll Tax (Sheffield, WR Yorks); Willelmo Walker’, 1381 in Poll Tax (Little Faringdon, Berks); Davidus Walkar, 1381 in Poll Tax (Hinton on the Green, Gloucs); Galfridus Walker, 1381 in Poll Tax (Kings Cliffe, Northants); Hugo le Walker, 1381 in Poll Tax (Wistanswick, Shrops); Agnes Walker, 1538 in IGI (Bromyard, Herefs); Edw. Walker, 1538 in IGI (Benington, Herts); Gulielmus Walker, 1538 in IGI (Hanley Castle, Worcs); Eme Walker, 1539 in IGI (Farnworth near Prescot, Lancs); Isabella Walker, 1539 in IGI (Halifax, WR Yorks); Marmaduke Walker, 1539 in IGI (Oswaldkirk, NR Yorks); Agnes Walker, 1541 in IGI (Morland, Westm); Elizabeth Walker, 1541 in IGI (Burton upon Trent, Staffs); John Walker, 1578 in IGI (Breedon on the Hill, Leics); Margaret Walker, 1578 in IGI (Burton Latimer, Northants); Katherina Walker, 1578 in IGI (Fillongley, Warwicks); Robert Walker, 1578 in IGI (Chippenham, Wilts); Willim Walker, 1580 in IGI (Selston, Notts).

Scotland Thomas dictus Walkar, 1324 in Cambuskenneth Register (Berwicks); William Walkere, 1361 in Moray Register (Inverness); Donald Walcare, 1457 in Newbattle Register (Edinburgh, Midlothian); Isbell Walker, 1561 in IGI (Dunfermline, Fife); Johne Walker, 1565 in IGI (Edinburgh, Midlothian); Alysone Walker, 1597 in IGI (Monifieth, Angus); David Walker, 1599 in IGI (Kelso, Roxburghs); Issobell Walker, 1605 in IGI (Aberdeen, Aberdeens); Margaret Walker, 1609 in IGI (Glasgow, Lanarks); Elizabeth Walker, 1620 in IGI (Duns, Berwicks); Issobell Walker, 1620 in IGI (Scone, Perths).

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

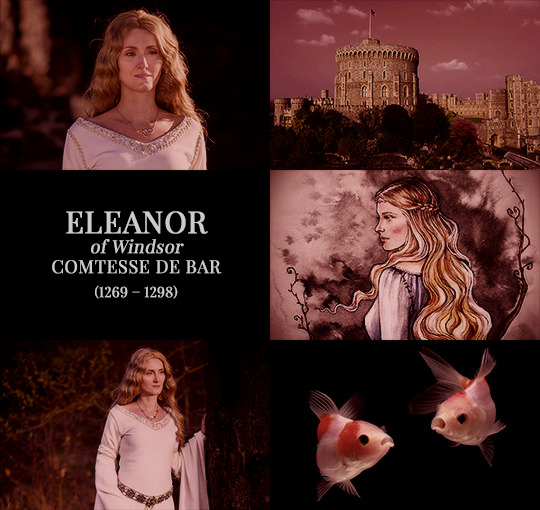

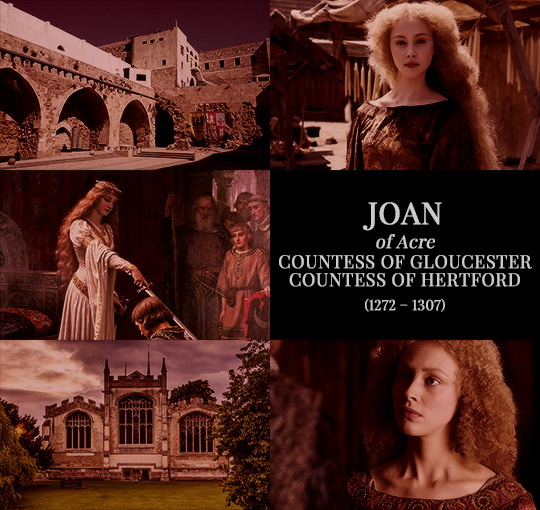

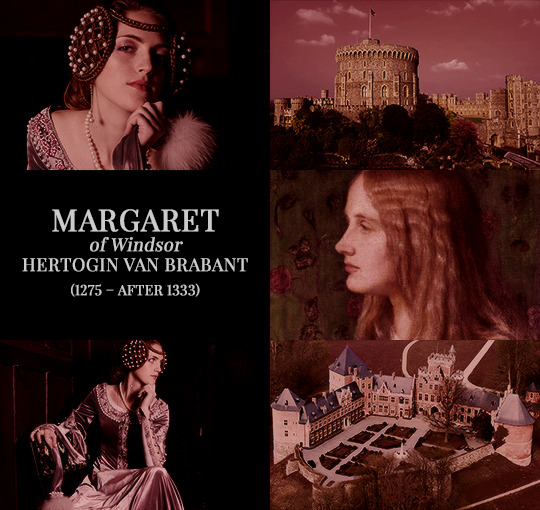

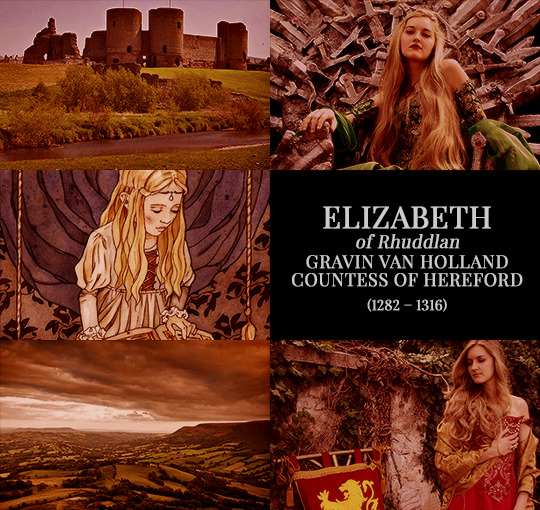

English princesses aesthetic, part II

Eleanor of Windsor, comtesse de Bar. Daughter of Edward I and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Jehanne de Bar, Countess of Surrey. Grandmother of Aliénor de Bar, duchesse de Lorraine.

Joan of Acre, Countess of Gloucester and Hertford. Daughter of Edward I and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Eleanor de Clare, 6th Lady of Glamorgan; Margaret de Clare, Countess of Gloucester; Elizabeth de Clare, 11th Lady of Clare; and Mary de Monthermer, Countess of Fife.

Margaret of Windsor, Hertogin van Brabant. Daughter of Edward I and Leonor de Castilla. Grandmother of Johanna, Hertogin van Brabant and Margaretha van Brabant, comtesse de Flandre.

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, Countess of Hereford. Daughter of Edward I and Leonor de Castilla. Mother of Eleanor de Bohun, Countess of Ormonde and Margaret de Bohun, 2nd Countess of Devon. Great-grandmother of Eleanor de Bohun, Duchess of Gloucester and Mary de Bohun, Countess of Northampton.

Eleanor of Woodstock, Hertogin van Gelre. Daughter of Edward II and Isabelle de France.

Joan of the Tower, Queen of Scots. Daughter of Edward II and Isabelle de France.

Isabella of Woodstock, Countess of Bedford. Daughter of Edward III and Philippa de Hainaut. Mother of Marie Ire de Coucy, comtesse de Soissons and Philippa de Coucy, Countess of Oxford.

Mary of Waltham, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Edward III and Philippa de Hainaut.

Blanche of Lancaster, Pfalzgräfin bei Rhein. Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun.

Philippa of Lancaster, Dronning af Danmark. Daughter of Henry IV and Mary de Bohun.

#house of plantagenet#medieval#house of lancaster#historyedit#english history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Here’s a mini tribute featuring some of my favorite dancers, all photographed by the wonderful Jason Lavengood aka @timber.no Dancers: (in no particular order 😉) 1) Macyn Vogt @macynvogt 2) Iana Salenko @iana_salenko 3) Kylie Shea @kyliesheaxo 4) Lia Cirio @msliac 5) Camila Cattani @camiballerina 6) Lillyan Fife @lilly_fife 7) Grace Rookstool @grace.cecelia.15 8) Isabella Bertellotti @bellla.balllerina . . . . . . . . . . #dreamdancerballet #fortheloveofballet #dancersofinstagram https://www.instagram.com/p/Bp76hcPj52N/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=ns2lfxyma2r9

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert the Bruce was born in Turnberry Castle, Ayrshire on 11th July 1274.

Well where do we start with this one? I think the majority of us know about Robert and how he led us to victory at Bannockburn so I will put a bit background together of his immediate family.

His mother Marjorie, Countess of Carrick, I think nowadays the term we would use, and it's quite appropriate , is battle-axe. According to what has been written about her she held his father, Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandaleprisoner until he agreed to marry her, it was through his mother that he drew most of his Scottish ancestry. The marriage must have worked for as well as Robert they had 7 more children.

After the Battle of Methven his wee brother Nigel de Brus was captured at Kildrummy Castle and was taken to Berwick to be hanged, drawn and beheaded for high treason, he was protecting Robert's wife, Elizabeth, his daughter Marjorie, his sisters Christina and Mary Bruce, and Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan and helped them escape, although they were later captured by Balliol's army and handed over to Edward I. Nigel was executed for high treason by being hanged, drawn, and quartered in September 1306 at Berwick-upon-Tweed by the English. Two of his other brothers, Alexander and Thomas were also judicially murdered at Carlisle on Februaey 17th 1307 after being captured at Loch Ryan Galloway in 1207, after landing an invasion force consisting of eighteen galleys trying to take land from Dungal MacDouall, who was a supporter of the Comyns,.

Arguably the most famous of his siblings was Edward Bruce, if you have been paying attention you will remember his part in fighting with Robert at Bannockburn, he later went and fought in Ireland and indeed became King for a short time but lost his life in the Battle of Faughart, the, it's said the victor John de Bermingham then took his head to England to be put on display before Edward II.

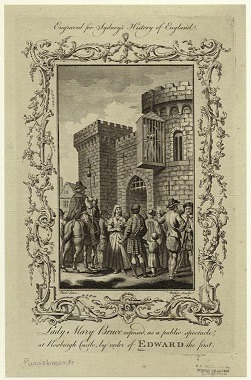

Robert's sisters, Christina and Mary, as I said earlier were captured after the siege at Kildrummy, along with Isabella MacDuff, now Isabella crowned the Bruce at Scone, it was tradition that the MacDuffs performed the crowning of Scottish monarchs, Isabella arrived the day after Robert had been crowned but the Bruce agreed to second crowning as otherwise some would see the ceremony as irregular, not being performed by a MacDuff.Isabella was imprisoned in cages for four years of Isabella, Edward Longshanks is said to have commanded "Let her be closely confined in an abode of stone and iron made in the shape of a cross, and let her be hung up out of doors in the open air at Berwick, that both in life and after her death, she may be a spectacle and eternal reproach to travellers."

The sisters faired a wee bit better, Isabel Bruce became Queen of Norway as the wife of King Eric II., so escaped the First War of Scottish Independence. Christina and Mary, also captured after Kildrummy, were sent into solitary confinement at a Gilbertine nunnery at Sixhills in Lincolnshire. Mary Bruce was given the same treatment as Isabella MacDuff, but held at Roxburgh Castle.. The sisters sspent eight years as English prisoners, and returned to Scotland in October 1314 as part of the ransom for the Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, who was taken prisoner after the Battle of Bannockburn.

There is not a great deal of detail about the other sisters, Margaret married one Sir William de Cairlyle. Lady Elizabeth Bruce married Sir William Dishington of Ardross, in Fife, and finally Matilda, (Maud) Bruce married Hugh 4th Earl of Ross.

Robert was married twice in his life, first to Isabella of Mar, who died in 1296, , with whom he had a daughter Marjorie, from whom the Stewart dynasty was to trace its lineage. His second wife was Elizabeth de Burgh, with whom he had five children – Margaret, Matilda, David, John (who died in infancy) and Elizabeth. His eldest son succeeded his father as King David II of Scotland.

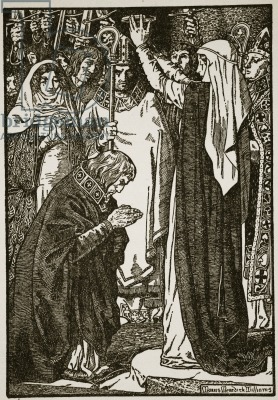

The photo shows Isabella MacDuff and King Robert I in “The Crowning of Bruce” part of an exhibition at Edinburgh Castle.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Downton Abbey - References to Historical Figures + References to Other Fictional Characters and Works

The following are two lists; one are real people who where mentioned on Downton Abbey, and the other is fictional characters and works that were also mentioned in the show. I complied these two lists together (because sometimes I had to research what was indeed being referenced!). As I didn’t know if I’d ever been sharing these lists, I don’t have the episode numbers listed out, but they do go in order by mention.

Real Historical Figures Mentioned in Downton

* means that the person was not contemporary of the characters and there for famous or well-known to them. Others without it may not be known personally by them, but are their contemporaries. Some of these have made it to the character list, if for sure they did indeed know the Crawleys, or other any other major character.

- Lucy Rothes (Titanic survivor, friend of the Crawleys) - John Jacob "JJ" Astor (business man who died on Titanic, friend of the Crawleys) - Madeleine Astor (not mentioned by name, but as JJ's wife, Titanic survivor, Cora did not like her) - Sir Christopher Wren* (architect, designed the Dower House) - David Lloyd George (politician and Prime Minister starting in 1916) - William the Conqueror* - Mark Twain* (author) - Queen Mary (wife of King George V) [mentioned in S1, appears in S4CS] - Queen Catherine of Aragon* - Oliver Cromwell* - Bishop Richard de Warren* - Anthony Trollope* (author; he would have been somewhat contemporary, died in 1882) - Piero della Francesca* (painter) - Franz Anton Mesmer* (scientist) - Thomas Jefferson* (politician, inventor, third president of the United States) - Léon Bakst (Russian painter and scene- and costume designer) - Sergei Diaghilev (another Russian artist) - Edith Vane-Tempest-Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry (sounds like the Crawleys did attend her parties from time to time) - Emily Davison (suffragist) - Herbert Henry "H.H." Asquith (politician and Prime Minister until 1916) - Kaiser Wilheim (ruler of Germany; Sir Anthony personally visited him a few times) - Vincenzo Bellini* (composer) - Gioachino Rossini* (composer) - Giacomo Puccini* (composer) - Karl Marx* (philosopher) - John Ruskin* (social thinker and artist; he would have been somewhat contemporary, died in 1900) - John Stuart Mill* (philosopher) - Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria - Guy Fawkes* - Gavrilo Princip (member of the Black Hand and Franz Ferdinand's assassin) - H.G. Wells (author) - Major General B. Burton - Heinrich Schliemann* (German businessman archaeologist, died in 1890; deleted scene mention) - General Douglas Haig (later a field marshal) - Belshazzar* (King of Babylon) - Mabel Normand (actress) - Plantagenets* - Eugene Suter (hair stylist) - Alexander Kerensky (Russian political leader) - Vladimir Lenin (Russian communist revolutionary) - Florence Nightingale* (nurse; died 1910) - Czar Nicholas II and the Romanov family (ruler of Russia) - Jack Robinson (footballer; he stopped playing in 1912) - Frederick Marryat* (author) - George Alfred "G.A." Henty* (author; he would have been somewhat contemporary, died in 1902) - Maximilien Robespierre* (French revolutionary) - Marie Antoinette* (French queen) - Erich Lundendorff (German commander) - Sylvia Pankhurst (suffragist) - Jack Johnson (boxer) - Commander Harold Lowe (Fifth Officer of the Titanic; if P. Gordon was really Patrick, he would have known him personally) - Theda Bara (actress) - Robert Burns* (poet, read by Bates; name is not uttered on screen, but it is clear on book cover) - Jules Verne* (author; he would have been somewhat contemporary, died in 1905) - Marion Harris (singer of "Look for the Silver Lining"; name is not uttered on screen) - Edward Shortt (Home Secretary from 1919-1922) - Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of York (one of the first actual historical figures in the show; married Matthew and Mary, visited Downton Abbey for dinner) - King George V (king of England) [mentioned in S3E1, appears in S4CS] - Charles Melville Hays (president of the Grand Trunk Railway that Robert invested in; died on the Titanic) - Robert Baden-Powell (founder of the Boy Scouts) - Lady Maureen Dufferin (socialite, friend of the Crawleys) - Georges Auguste Escoffier (famous chef and restaurateur) - Marie-Antoine Carême* (famous chef) - Queen of Sheba* - Napoleon Bonaparte* - The Bourbons* - The Buffs* (famous army regiment; "steady the Buffs" popularized by Kipling) - Croesus* (king of ancient Lydia; mention several times starting in S3 and through S4) - Thomas Edwin "Tom" Mix (Wild West picture star) - Dr. Samuel Johnson* (English writer; quote paraphrased by Carson) - Jean Patou (dress designer; maker of Edith's S3 wedding dress in-show) - Lucy Christiana, Lady Duff-Gordon (dress designer of "Lucille"; a survivor of the Titanic) - The Marlboroughs (famous family; mentioned like the Crawleys knew them personally, Sir Anthony did) - The Hapburgs* (rulers of the Holy Roman Empire) - Maud Gonne (English-born Irish revolutionary) - Isabella Augusta, Lady Gregory (Irish revolutionary) - Constance Georgine Markievicz, Countess Markievicz (Irish revolutionary and politician) - Lady Sarah Wilson (née Churchill) (female war correspondent) - Gwendolen Fitzalan-Howard, Duchess of Norfolk (real person and friend of Violet's) - Pope Benedict XV - Lillian Gish (actress) - Ivy Close (actress) - Alfred the Great* (9th century ruler of England) - Oscar Wilde* (author; he would have been somewhat contemporary, died in 1900) - Nathaniel Hawthorne* (author) - Charles Ponzi - Walter Scott* (author) - Charles Dickens* (author) - Virgina Woolf (author, one of the first actual historical figures in the show, was not actually mentioned though, just a background guest at Gregson's party) - Roger Fry (artist, one of the first actual historical figures in the show, was not actually mentioned though, just a background guest at Gregson's party) - Sir Garnet Wolseley* - Phyllis Dare (singer and actress) - Zena Dare (singer and actress, sister to Phyllis) - Maurice Vyner Baliol Brett (the second son of the 2nd Viscount Esher, Zena Dare's husband) - King Canute* (Cnut the Great, norse king) - Nellie Melba (opera singer, one of the few actual historical figures in the show) - Al Jolson (singer) - Christina Rossetti* (poet) - Marie Stopes (feminist doctor and author of Married Love) - George III* (ruler of England) - Lord Byron* - Arsène Avignon (chef at Ritz in London, actual historical figure in the show) - Louis Diat (chef at Ritz in New York) - Jules Gouffé* (famous chef) - King of Sweden (whoever it was when Violet's husband was alive) - Rudolph Valentino (actor) - Agnes Ayres (actress) - Lord Robert Henley, 1st Earl of Northington* (Lord Chancellor and abolitionist) - Albert B. Fall (US senator and Secretary of the Interior) - King Ludwig* (I’m assuming of Bavaria) - John Ward MP (liberal politician, actual historical figure in the show) - Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe (Royal Navy, Blake and Tony served under him) - Benjamin Baruch Ambrose (bandleader at the Embassy Club, his band appears on-screen but it's not pointed out who he is) - The Prince of Wales (David, who became Edward VIII when King) - Freda Dudley Ward (socialite and mistress of the above) - The Queen of Naples* - Wat Tyler* (leader of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England) - Edmond Hoyle* (writer of card rules) - Ramsay MacDonald (Prime Minister Jan-Nov 1924) - Archimedes* - Boudicca* (Queen of the British Iceni tribe) - Rosa Luxemburg (Revolutionary) - Charles I* - Douglas Fairbanks (movie star) - Jack Hylton (English band leader) - Edward Molyneux (fashion designer; Cora has a fitting with him in S5E3) - The Brontë Sisters* (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, all authors. Anne's work The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was the charade answer in S2CS.) - Leo Tolstoy* (author) - Nikolai Gogol* (author) - Elinor Glyn (author of romantic fiction) - Czar Alexander II - Prince Alfred (son of Queen Victoria) - Grand Duchess Maria (wife of Alfred, daughter of the czar) - Peter Carl Fabergé (Russian jeweller) - Ralph Kerr (officer in the Royal Navy; Mabel mentions a man by this name as a friend) - Keir Hardie (Scottish socialist, died in 1915) - The Moonella Group (formed a nudist colony in 1924 in Wickford, Essex) - John Singer Sargent (American painter, died in 1925) - Rudyard Kipling (author and poet - often quoted starting in S1, but first mentioned by name in S5) - Mary Augusta Ward (Mrs. Humphrey Ward - author; I'm not adding her to the character list, died in 1920) - Adolf Hitler - Pola Negri (film star) - John Barrymore (actor [Drew Barrymore's grandfather]) - King Richard the III (of England)* - Hannah Rothschild and Lord Rosebery (British socialites Violet knew; Hannah died in 1890) - General Reginald Dyer - Lytton Strachey (supposedly was at Gregson's party) - Niccolo Machiavelli* - Adrienne Bolland (aviatrix) - The Fife Princesses (as listed by Sir Michael Reresby) - Duke of Arygll (as listed by Sir Michael Reresby) - The Queen of Spain (as listed by Sir Michael Reresby) - Lady Eltham (Dorothy Isabel Westenra Hastings) - King John* - Neville Chamberlain (Minister of Health in 1925, later Prime Minister; appears on-screen in S6E5) - Anne de Vere Cole (Neville Chamberlain's wife. Fictitiously, she is Robert's father's goddaughter. Her father is mentioned has having served in the Crimean War with Robert's) - Horace de Vere Cole (Anne de Vere Cole's brother) - Joshua Reynolds* (painter) - George Romney* (painter) - Franz Xaver Winterhalter* (painter) - Sir Charles Barry* (real architect of Highclere, cited here as one as Downton Abbey) - Tsar Nicholas I* - Teo (or Tiaa)* - Amenhotep II* - Tuthmosis IV* - King Charles* - Clara Bow (actress) [To my knowledge, the Ripon election candidates in S1E6 were not real people, as were not always the case for military personnel Robert referred to.] Fictional Characters and Works Mentioned in Downton - Long John Silver (referenced by Thomas) - Andromeda, Perseus, Cepheus (Greek mythology) (referenced by Mary) - Sydney Carton (A Tale of Two Cities) (referenced by Robert) - Princess Aurora, and later Sleeping Beauty (the ballet I presume) (referenced by Robert) - Horatio (Hamlet; Thomas quotes a line in a deleted scene) - "Gunga Din" (poem by Kipling; quoted by Bates and later quoted by Isobel) - Little Women (referenced by Cora) - The Lost World - Elizabeth and her German Garden (book given to Anna by Molesley) - Wind in the Willows (referenced by Violet) - "If You Were the Only Girl in the World" (sung by Mary, Matthew and cast) - "The Cat That Walked By Itself" (short story by Kipling; quoted by Matthew) - Iphigenia (Greek mythology, may be referenced in The Iliad but I cannot confirm) - Uncle Tom Cobley ("Widecombe Fair") (referenced by Sybil) - Alice and the Looking Glass - "The Rose of Picardy" (only a few strains played, possibly the John McCormack version which was out in 1919) - Zip Goes a Million and "Look for the Silver Lining" (song played by Matthew) - The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (title used in The Game) - Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Angel Clare (referenced by Mary) - Lochinvar (from Sir Walter Scott) (referenced by Martha) - "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring" (played at Mary and Matthew's wedding) - "Let Me Call You Sweetheart" (sung by Martha and cast) - "Dashing Away with the Smoothing Iron" (English folk song sung by Carson) - Way Down East (film) - The Worldings (film) - "Molly Malone" (Irish song) - The Scarlet Letter (referenced by Isobel) - Lady of the Rose (musical) - The Lady of Shalott (ballad) - The Puccini pieces from S4E3 - The jazz pieces from S4E4 sung by Jack Ross ("A Rose By Any Other Name") - The Sheik (film) - The jazz pieces from S4E6 sung by Jack Ross ("Wild About Harry") - "The Second Mrs Tanqueray" (play and films) (referenced by Edith) - "The Sword of Damocles" (Greek myth) - Dr. Fu Manchu - Mrs. Bennett (Pride and Prejudice) - A vague allusion to Wuthering Heights (talking about the Brontë sisters and moors) (referenced by Rose) - Vanity Fair and Becky Sharp (Molesley reads this with Daisy) - "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (sung by Denker) - "The Fall of the House of Usher" (short story by Edgar Allen Poe) - Madame Defarge (A Tale of Two Cities) - Ariadne (Greek mythology) - "Cockles and Mussels" (Spratt sings a few bars in S6E5; this is also called "Molly Malone") - Elizabeth Bennett and Pemberley (Pride and Prejudice) (referenced by Violet) - Mr Squeers (Nicholas Nickleby) (referenced by Bertie) - The Prisoner of Zenda (adventure novel by Anthony Hope) (referenced by Tom) - "The course of true love never did run smooth" (quote from A Midsummer Night's Dream) Not included are proverbs or sayings (which Anna says a lot of), nor Biblical references. Do note that there's a lot of scenes with the characters reading, but we don't know exactly what.

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#OnThisDay Year 1324, Birth of David II of Scotland. was King of Scotland for nearly 42 years, from 1329 until his death in 1371. He was the last male of the House of Bruce. Although David spent long periods in exile or captivity, he managed to ensure the survival of his kingdom and left the Scottish monarchy in a strong position. David II was the eldest and only surviving son of Robert I of Scotland and his second wife, Elizabeth de Burgh. He was born on 5 March 1324 at Dunfermline Abbey, Fife. His mother died in 1327, when he was 3 years old. In accordance with the Treaty of Northampton's terms, on 17 July 1328, when he was 4, David was married to 7 year old Joan of the Tower, at Berwick-upon-Tweed. She was the daughter of Edward II of England and Isabella of France. They had no issue. #RoyalBirth #RoyalHistory #HistoryofRoyals #DavidII #Scotland #Monarchy #EuropeanRoyalties https://www.instagram.com/p/CMB2G_xFIGU/?igshid=lx17y87zxj7w

1 note

·

View note

Text

onceideals said: Can someone explain why would she crown him?

Hi! Hope you don’t mind me weighing in on this as the OP, because I never tire of telling Isabella MacDuff’s story.

Basically, since at least the twelfth century if not earlier, the earls of Fife had occupied a very important position in Scottish politics. While they might not always be the strongest magnates, militarily or economically, they seem to have been regarded as first among the Scottish earls, not least because of their close associations with the Scottish Crown. These were both political (as close allies of the Canmore kings) and symbolic, as the earls of Fife had gradually acquired a central role in the Scottish coronation process, where they were charged with setting the new king of Scots on the stone of destiny and thus investing him with his title. (Probably Isabella of Fife did not actually physically crown Robert Bruce either, but install him on the throne- nonetheless this coronation pose has become so deeply associated with her legend that it’s no wonder it was used on film). In any case, as a daughter of one of the earls of Fife, this was Isabella’s heritage, and even after ten years of English attempts at conquest, and nearly twenty years of political uncertainty, it was clearly important in the minds of the Scottish political community that tradition be satisfied. At the last Scottish coronation, that of the ill-fated John Balliol in 1292, the earl of Fife’s role had been carried out by a knight named John of St John, but this was because the earl- Duncan MacDuff- was then probably a very small child. This earl of Fife was either Isabella’s brother or nephew, but whatever the case Isabella clearly felt that she was entitled to act in her kinsman’s absence in 1306, as Earl Duncan was in English captivity when Robert Bruce made his bid for the kingship.

There were a few snags of course. Not everybody in Scotland was happy to see Robert Bruce crowned king, especially since, not only was the deposed King John still alive, but Bruce had recently murdered the better claimant- King John’s nephew John ‘the Red’ Comyn of Badenoch- in a church. Since Robert Bruce proclaimed himself king not long afterwards, this drove the Comyns and their allies- formerly as active on the ‘patriotic’ side as any other major Scottish nobles- firmly into the English camp, and sparked a civil war in Scotland between the supporters of the Balliols and Comyns, and the supporters of the Bruces, which would rear its ugly head many times over the next fifty years or more. Chief among the disgruntled kinsmen of Comyn of Badenoch was his powerful cousin, John Comyn, Earl of Buchan, a major Scottish magnate, especially in the north, and whose father and grandfather had dominated thirteenth century Scottish politics (you see him for like two seconds in Outlaw king, sporting a bad haircut in the courtyard of Linlithgow Palace). And it was this earl of Buchan, one of Bruce’s chief enemies until his death in 1308, who was Isabella of Fife’s husband.

To this day it is unclear why Isabella MacDuff acted as she did in March 1306 (and so, in that sense, we can’t actually explain why she’d crown Bruce). Like many of the women of the wars of independence, we know so little about her private- or even public- thoughts that many people have speculated about her backstory. Some novelists and other popular writers have suggested she was in love with Bruce (which, though not impossible, has no evidence to back it up and smacks of a kind of ‘women can only ever do anything out of love for a man’ attitude), others have speculated about the nature of her relationship with her husband (again, no evidence for any ill treatment, but by the end there was certainly no love lost between them). Possibly she saw supporting the Bruce claim as the most likely strategy to secure Scotland’s independence, or perhaps she just wished to take a rare opportunity to act politically in a man’s world. There’s also the possibility that her father had been aligned to the Bruce party in the 1280s. Whatever the case, as soon as she heard that Bruce intended to have himself crowned, Isabella quit her husband’s house and rode quickly to Scone, intending to play her part in the proceedings. She arrived too late- the coronation had already gone ahead, but Isabella’s claim must have been impressive, as two days later they went through the whole process again, so that tradition could be satisfied when the blood of the earls of Fife placed Robert Bruce on his throne (no stone of destiny, this, like Isabella’s brother, had also been removed south to England).

It was a bold act, but in the end Isabella paid dearly for her defiance of both her marital house and the English king. Along with other ladies of Bruce’s court, including at least two of his sisters, his wife Elizabeth de Burgh, and his daughter Marjorie, Isabella was captured at Tain only a few months after Bruce’s coronation and sent south into English captivity. According to some chronicles her own husband Buchan called for her to be put to death for her treachery, however she was instead condemned to be imprisoned in a cage, suspended in a tower at Berwick-upon-Tweed (one of King Robert’s sisters Mary Bruce was imprisoned in a similar cage at Roxburgh Castle, and there may also have been plans to have young Marjorie Bruce imprisoned in one at the Tower of London though this was soon discarded and she was sent to a nunnery instead). Isabella does not seem to have lived to see her actions vindicated- while Bruce began winning back Scotland from 1307 on, she is not recorded after 1313, suggesting she may have died as a result of her harsh captivity, a year before the other ladies were released following Bannockburn. Either way her short career offers a fascinating insight into the ways in which women could act politically in the fourteenth century, and how they viewed their own family heritage, as well as how this could conflict with the political allegiance of their marital house

Sources and further info here.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLAN CARRUTHERS - ELIZABETH DE BURGH

CLAN CARRUTHERS – ELIZABETH DE BURGH

ELIZABETH DE BURGH

Elizabeth de Burgh, was the daughter of Richard Óg de Burgh, 2nd Earl of Ulster, and Margarite de Burgh, she was born circa 1289 at Dunfermline, Fife.

Robert the Bruce, also held the title Earl of Carricks. His first wife Isabella of Mar had died in childbirth six years previously, leaving him with just a daughter, Marjorie Bruce ( WHO CARRIES THE CARRUTHERS DNA GENOME ).…

View On WordPress

#Clan Carruthers#Ancient and Hononrable Carruthers Clan Society Int LLC.#Carrothers#Carothers#Credeur#Crothers#Crowder#GILBERTINE CONVENT#Marjorie Bruce#ROBERT THE BRUCE#SCONE ABBEY#Ulster

0 notes

Text

Setting the King on his Throne: Isabella of Fife, Countess of Buchan

It’s been a while and I hope everyone had a good new year! For my part, I’m kicking off the year with a rather well-known figure: Isabella of Fife, Countess of Buchan, one of the most famous women of the Wars of Independence (no mean feat- there are not enough famous ladies, but there are quite a lot who deserve to be). Aside from her actions in 1306 and subsequent imprisonment, Isabella is quite a shadowy figure, but she is a highly important one in Scottish history and definitely deserves a place on this blog. After all, if you can't find room in your day for a woman who defied her husband and the English king to crown Robert Bruce, I don't even know what you're following for.

It is unclear just when Isabella was born. There is even uncertainty over who her parents were- some sources say she was the sister of Duncan IV, Earl of Fife, others claim she was his aunt. That would mean she was either the daughter of Colban, Earl of Fife, and his wife the daughter of Alan Durward, or she was the daughter of Duncan III, Earl of Fife, and his wife Joanna de Clare, daughter of the Earl of Gloucester- the latter is generally thought more likely but it is an open debate. Perhaps we can vaguely put her birth date between 1265 and 1285, but given that both her (supposed) father and grandfather died young it is difficult to be sure. Earl Colban died in the early 1270s, while Duncan was murdered in 1289, leaving a similarly young son named Duncan as his heir. The younger Duncan would be considered a minor until after the end of the century- if Isabella was his sister, she cannot have been much older, though was certainly of age to be married before 1297. In the meantime, their uncle, known to us only as MacDuff (perhaps indicating that he was considered head of the kindred even if his nephew was earl) and apparently a brother of Earl Colban, caused some trouble over properties he believed had been left to him by his father.

In any case, Isabella was daughter to the Earl of Fife, who, although he was not always the most politically or territorially powerful of Scotland’s magnates, was generally regarded as symbolically ranking first among them. We can safely say that Isabella counted among her ancestors such notable figures as Llywellyn the Great, Prince of Wales, Alexander II of Scotland (and thus through him she was descended from personages such as David I and St Margaret), and Adeliza of Louvain second wife to Henry I of England, whilst if she was the daughter of Joanna de Clare, she could also count among her ancestors Isabella of Angouleme (through the Lusignans) and Strongbow. Although Fife is now a firmly Lowland county- or kingdom- in the thirteenth century it still retained much of its Gaelic character, even though English was probably the main language of its bustling east coast burghs. The mormaers- later earls- of Fife, members of the Clan MacDuff, had been the chief lords in the area since the tenth century. Over more recent centuries they had acquired the “right” to a special role at the coronation of the kings of Scots- that of placing the king on the stone of Scone, as other kings might be placed on a throne. With young Earl Duncan still in his minority, a knight named John of St John was nominated to fill this role at the coronation ceremony of John Balliol in 1292. Nonetheless, the symbolic role of the earls of Fife, and their status as heads of the political community, was still highly respected.

(Some key locations and regions for the life of Isabella of Fife. The dots aren’t quite in their exact positions, because I’m not great at geography, but it’s just meant to give an idea.)

As the daughter of the Earl of Fife, Isabella was expected to make a profitable marriage and she wed John Comyn, Earl of Buchan before 1297. The Comyn family, especially the Badenoch and Buchan lines, were the most powerful baronial family in Scotland during the late thirteenth century. This was especially true north of the Forth where their lands stretched from Buchan in the east to Lochaber in the west, though they also had sizeable holdings south of the Forth and in England. They had played a leading role in Scottish politics during the reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III, and continued to do so during the uncertainty following the latter’s death. Their importance only grew in 1292, when John Balliol ascended to the Scottish throne, a man whose sister was married to John Comyn of Badenoch, and was mother to John ‘the Red’ Comyn. This meant that Isabella’s husband was not only one of the most important magnates in the realm and one of King John’s main supporters, but was also cousin to the man who was next in line for the throne should the Balliol line fail.

All this rather long-winded scene-setting aside, as we all know, John Balliol did not have a great time as king. Eventually, with Edward I becoming increasingly overbearing, and the unfortunate King John increasingly browbeaten, a council of Scottish magnates, including the Comyns, removed the power from the King of Scots’ hands. Determined not to give in to the English king’s demands, which would have been seen as confirming Scotland’s subservient position, they continued to pursue an alliance with the French. This led to the Scottish Crown’s decision to physically support the French (and perhaps also preempt an English attack) by assembling the realm’s army, and this in turn resulted in a short war in which the Scots were quickly overcome at the Battle of Dunbar. King John fled into the north-east but was later forced to surrender and was publicly stripped of his crown, while the Comyns, like the rest of the Scottish nobility, were eventually received into the English king’s peace.

(John Balliol doing homage to Edward I of England)

It was not long before trouble broke out again in Scotland, when William Wallace and Andrew Moray rose up in 1297. The Earl of Buchan was technically supposed to be keeping the peace but, like many Scottish magnates, he seems to have cautiously remained on the fence. We have no indication of his wife Isabella’s opinion during this troubled period, except a grant that allowed her to take wood from near to her husband’s Leicestershire property, which indicates she was still in the king of England’s good books and living reasonably peacefully. Her possible mother, Joanna de Clare, was not so lucky during this troubled period, and in 1299 brought charges against a Scot named Herbert de Moreham for having ambushed, abducted, and imprisoned her upon her refusal to marry him, and then having robbed her of her possessions to the tune of two thousand pounds. Meanwhile, Isabella’s brother/nephew, Duncan, became a captive in England, though he nominally retained his title. Her kinsman MacDuff, was less easily cowed, taking part in Wallace’s rebellion and leading the men of Fife against the English, though this ended with his death at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298.

Though this long (but nonetheless very generalised) explanation of the events of the 1290s is somewhat necessary to understand the context of Isabella’s lifetime, it is to the year 1306 that we must look for her real activity. In this year, Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, shocked the political community on both sides of the border when, in Greyfriars church in Dumfries, he stabbed John Comyn of Badenoch during what was supposed to be a peace conference. By primogeniture, and with the Balliols sidelined, Comyn had a better claim to the throne, so by murdering him Bruce had, quite ruthlessly, cleared a path to the kingship. But he had also enraged both Edward I of England and the entire Comyn family network (and their many allies) who, although hitherto as flexible with their patriotism and loyalty to the king of England as any other Scottish nobles, now found themselves firmly in the English camp as Bruce claimed the throne of Scotland. The Earl of Buchan, then in England, would have been furious at his cousin’s death, and whether Isabella of Fife was with her husband or not, she would have been well aware of the implications of Bruce’s bloody attack on her marital house, an act for which he was excommunicated.

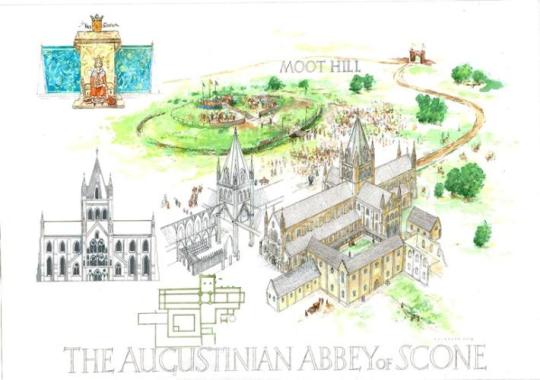

(An artist’s depiction of Scone Abbey in c.1371- not my picture, found here)

For some reason, though, Isabella seems to have viewed the situation very differently to her husband. The previous Earl Duncan of Fife may have been loosely associated with the Bruces in the past and this might have left a mark on Isabella’s allegiances. Or perhaps she viewed Bruce as a candidate who could genuinely lead the Scots to independence, regardless of his crimes. Perhaps she simply seized an opportunity to act politically in a time where women’s opportunities were limited, or felt it was her turn to look out for the interests of her birth family while the earl of Fife was in captivity and other male members of the kindred dead. Some English chroniclers even claim she harboured romantic feelings towards Bruce, and while of course this cannot ever be proved or disproved, it perhaps says more about mediaeval chroniclers’ inability to imagine a woman taking political action for any reasons other than lust. It is similarly difficult to tell if Isabella had had any contact with the Bruce faction before the murder of Comyn of Badenoch, or if it was a spur of the moment decision. Whatever the case, she seems to have had fast horses readied in advance and was merely waiting for the right moment to take action. Upon hearing of Bruce’s decision to crown himself at Scone, she promptly quit her husband’s house and rode there herself. Intending to take the place of the captive earl of Fife, she claimed the right to fulfil the ancient duty of her house by placing King Robert on his throne.

But by the time Isabella arrived at Scone Abbey, the traditional coronation spot of Scottish kings outside the city of Perth, a coronation had already taken place. On Lady Day (25th March), at a ceremony attended by several earls and the bishops of St Andrews and Glasgow, not to mention the abbot of Scone and many other nobles and clerics, Robert Bruce had been crowned in defiance of the king of England and not two months after having blasphemously murdered the rival claimant in a church. He was by no means secure on his claimed throne, but the coronation was still an impressive display of his political and ecclesiastical support. Nevertheless, the sight of the Countess of Buchan, who must have ridden a considerable way in a very short amount of time and defied her husband to boot, and the importance of tradition- or perhaps simply Isabella’s force of character- seems to have convinced the king and his counsellors to go through with a second coronation. On the 27th of March, Robert was once again proclaimed king of Scots, and satisfied tradition when Isabella of Fife placed him on the throne in the manner of her forefathers, though the stone of Scone and the earl of Fife both remained captive in England.

(The mausoleum on the Mote hill which now stands on top of where the kings of Scots were once crowned- the investiture of Scottish kings, rather like medieval weddings, probably took place outside the abbey on the Mote hill and not inside the church itself)

Unfortunately for Isabella, the start of the new king’s “reign” did not go quite so well as his coronation. An English army was raised not long after the news of John Comyn’s murder and Bruce’s coronation reached the ears of Edward I, and in June Robert’s army was defeated at the Battle of Methven, near Perth. Forced to flee to the Western Isles, Robert decided to send his female family members away to Kildrummy Castle in Aberdeenshire. This castle was at the centre of the earldom of Mar, and King Robert’s first wife had been the earl’s sister so it probably seemed like a strong place in which they would be protected. The queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, and Robert’s daughter from his first marriage Princess Marjorie, along with at least two of the king’s sisters, were sent north in the care of his brother Neil Bruce and John de Strathbogie, the earl of Atholl. The Countess of Buchan, now firmly an adherent of the Bruce cause, was also with them. However not long after they reached Kildrummy, they must have heard that an army under the command of Edward, Prince of Wales, was heading for the castle. Leaving Neil Bruce in charge of the garrison, Atholl conveyed the queen and her ladies further north still, possibly hoping to reach the safety of Orkney and then maybe Norway, where King Robert’s sister was the dowager queen. Kildrummy Castle, meanwhile, held out only a short while before the garrison were betrayed, and Neil Bruce and others were taken south to be hanged.

Hurrying north, the fugitives stopped for shelter in the church of St Duthac at Tain. This small chapel overlooking the windy shores of the Dornoch Firth (the long estuary separating Ross from Sutherland) was a sacred place, holding the shrine of a popular local saint, and its sanctuary extended not just to the chapel but also the surrounding area. As they huddled in its walls, the party might have been forgiven for trusting to the safety of this holy spot and the name of St Duthac. Unfortunately, this trust was to prove horribly misplaced. Uilleam, the Earl of Ross and an adherent of the Balliols whose line Bruce had usurped, was not about to let such a valuable prize sit unmolested in his own territory. Breaking the sanctuary, he had Atholl and the ladies taken prisoner, and sent them south to England. Ross would later be received into King Robert’s peace, but was obliged to make an offering for Atholl’s soul at Tain which would have important implications for the town’s growth. In 1306, however, the captured women and earl faced harsh imprisonment and worse at the hands of an enraged Edward I.

(The ruined chapel where Isabella and many others were captured after the Earl of Ross broke sanctuary.)

(The links at Tain, Ross, looking towards Sutherland over the firth. For context purposes)

John, Earl of Atholl, like other male supporters of the Bruce claim, was to be executed by the humiliating method of hanging. Members of the English political community’s begged for mercy on his behalf, or at least for a more honourable death since Atholl was related to the English king, but Edward I’s reportedly refused, saying that his rank only meant that the earl would be hanged on a higher gallows. The queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, was the daughter of the Earl of Ulster, an important supporter of Edward, so was given a rather more lenient punishment in the form of house arrest, though she was still often short of funds and occasionally kept in filthy conditions. Christian Bruce, one of the two sisters of Robert I captured at Tain and the wife of Christopher Seton (hanged in August 1306), was likewise placed under house arrest in Sixhills nunnery in Lincolnshire. However her sister Mary Bruce, along with Isabella of Fife, faced a rather worse fate. The chronicle of Guisborough goes so far as to claim that Isabella’s husband the Earl of Buchan called for his wife’s execution, though ultimately this was not to occur. Instead Mary and Isabella were placed in “cages” in the castles of Roxburgh and Berwick respectively. The writer of ‘Flores Historiarum’ (this chronicle gives rather a colourful account of the Scottish situation so is perhaps taken with a pinch of salt) even places the following words in the mouth of Edward I, when deciding on Isabella’s punishment:

“Because she did not smite with the sword, she shall not perish by the sword. But because of the unlawful crowning which she made, let her be kept most fastly in an iron crown, made after the fashion of a little house, whereof let the breadth and length, the height and the depth, be finished in the space of eight feet; and let her be hung up for ever at Berwick under the open sky, that all they who pass may see her and know for what cause she is there.”

It’s a little bit unclear whether these cages were actually suspended outside the castles in full view of the public and open to the elements, as various chroniclers report, or if they were merely extreme security measures taken within the towers of the castles. The official instructions for the construction of Isabella’s cage included orders that the cage be constructed “in one of the turrets” of Berwick, and that she have “the convenience of a decent chamber” and be kept secure, but the imprisonment of the ladies at the Scottish castles Roxburgh and Berwick, rather than securely in England, must have had some symbolic purpose. In any case, conditions were harsh, and the women were not to be allowed to speak to anyone except their guards, and especially not other Scots. They were to remain in these cages for years. Fortunately for the young Marjorie Bruce, similar plans to imprison her in such a cage in the Tower of London were scrapped and she was put under house arrest in another Lincolnshire nunnery. Nevertheless, none of the women would see freedom for at least eight years, when most were released after the Battle of Bannockburn.

This freedom came too late for Isabella however. Living in a cage would have been a harsh life, and even harsher if the cage was actually suspended outdoors. Mary Bruce seems to have been removed from Roxburgh by 1311, being kept a prisoner in Newcastle until Bannockburn, (as Roxburgh was taken by the Scots in 1313, this move was probably due to strategy rather than mercy). Isabella was not similarly moved on that occasion and our last glimpse of her is in April of 1313, by which time the Scots had already made one attempt on the town of Berwick the previous year and had successfully captured Roxburgh and Edinburgh only a few weeks earlier. Then she was finally released from imprisonment at Berwick and placed under house arrest in the keeping of Henry de Beaumont and his wife Alice Comyn, her late husband’s niece and heiress to the earldom of Buchan. She does not appear in any prisoner exchanges post-Bannockburn however, and it is probable that she died not long afterwards (it has been theorised that the conditions of her imprisonment may have hastened her demise but this cannot be proven). In any case, she at least outlived her husband, the Earl of Buchan, who had died in 1308. There was no issue from their marriage and so the claim to the earldom passed to the earl’s nieces, one of whom was married to Henry de Beaumont (and, due to this, de Beaumont would cause quite a bit of trouble for the Bruces in later decades). Nonetheless, though we only have a small amount of information on her Isabella of Fife was clearly a woman with a backbone of steel, defiant and determined to make her mark, and well-deserves her place in the history books.

(A depiction of Mary Bruce in her cage at Roxburgh. Isabella would have been held similarly at Berwick, though I will not swear to the accuracy of these cages in the drawings)

References:

Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland preserved in the English archives

Acts of the Parliament of Scotland

Chronicle of Guisborough

Chronicle of Lanercost

Flores Historiarum

Scalachronica (by Sir Thomas Gray)

Chronica Gentis Scotorum (John of Fordun)

The Brus (John Barbour)

“Widows of War: Edward I and the Women of Scotland during the War of Independence”, by Cynthia J. Neville, in ‘Wife and Widow in Medieval England’, ed. Sue Sheridan Walker

Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, by G.W.S. Barrow

The Comyns, Alan Young

The Women of the Wars of Independence in Literature and History, R.J. Goldstein

And others.

#isabella macduff#Scottish history#People#British history#women in history#Scotland#Anglo-Scottish Relations#warfare#Wars of Independence#Isabella of Fife Countess of Buchan#Buchan#Comyn family#Fife#Clan MacDuff#John Comyn Earl of Buchan#Robert the Bruce#Edward I#John de Strathbogie Earl of Atholl#Scone Abbey#stone of scone#women of independence#thirteenth century#fourteenth century#nobility#House of Bruce#John Balliol#Tain#Ross#Earl of Ross#William Earl of Ross

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1902 Fife, Scotland: great great grandma Isabella (b1848) with five grandchildren, my grandma on the right (1897-1979) via /r/TheWayWeWere https://ift.tt/2Tb3keo

0 notes