#Mahāyāna Buddhism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kwan Yin.

#kwan yin#guanyin#bodhisattva#buddhist#buddhism#觀音#chinese mythology#Avalokiteśvara#taoism#Vietnamese mythology#korean mythology#compassion#bodhisatva#Mahāyāna Buddhism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kek Lok Si Temple Penang Malaysia

#Abbot Beow Lean#Air Itam Mountain George Town Penang#Amitabha Buddha Pagoda -Three-Tier Pagoda#Buddhist Vatican Fujian China#Ch’i Kuo Guardian of the West#Ch’ng Chang Guardian of the East#Crane Mountain#Guanyin (Kuan Yin) Goddess of Mercy#Kek Lok Si Funicular#Kek Lok Si Hall of the Devas or Heavenly Kings#Kek Lok Si Liberation Pond#Kek Lok Si Temple Penang#Kuang Mu Guardian of the North#Mahāyāna Buddhism#Maitreya Buddha of the Future#Maitreya Laughing Buddha#Sacred Turtle Pond#Ten Thousand Buddha Pagoda#Thai King Rama VI#Theravada Buddhism#Tian Huang Dian#Tou Wen Guardian of the South#Traditional Chinese Buddhism#Venerable Beow Lean

0 notes

Text

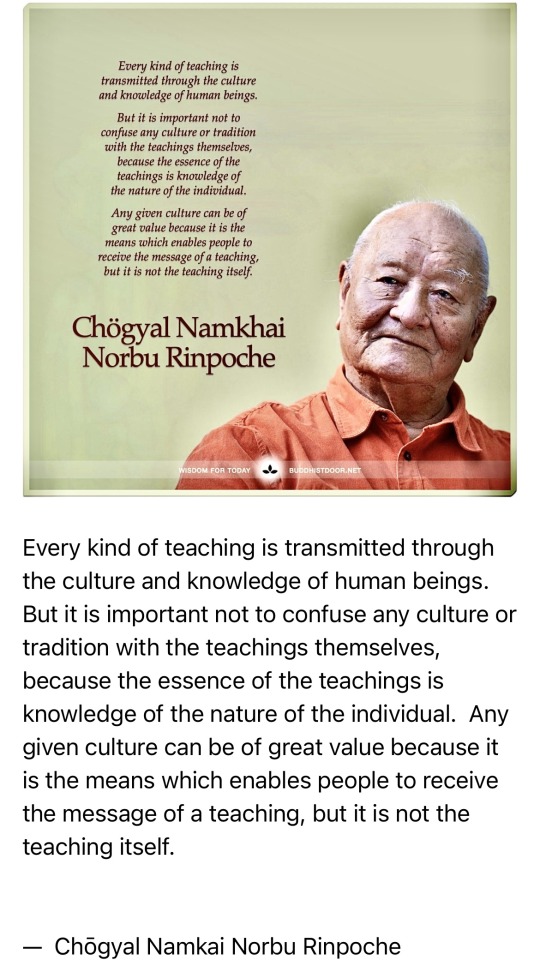

Namkhai Norbu (Tibetan: ནམ་མཁའི་ནོར་བུ་, Wylie: nam mkha’i nor bu; 8 December 1938 – 27 September 2018) was a Tibetan Buddhist master of Dzogchen and a professor of Tibetan and Mongolian language and literature at Naples Eastern University. He was a leading authority on Tibetan culture, particularly in the fields of history, literature, traditional religions (Tibetan Buddhism and Bon), and Traditional Tibetan medicine, having written numerous books and scholarly articles on these subjects.

•

•

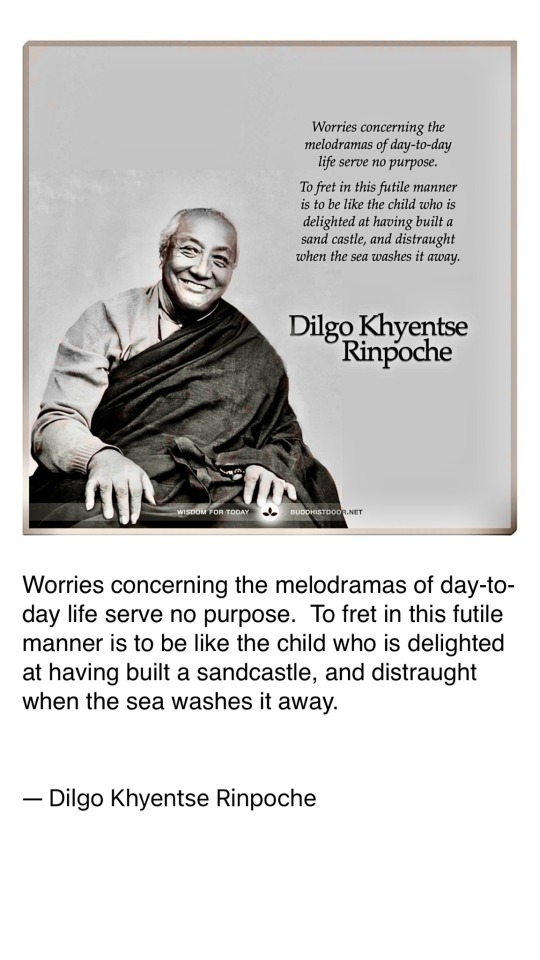

Tashi Paljor, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (Tibetan: དིལ་མགོ་མཁྱེན་བརྩེ་, Wylie: dil mgo mkhyen brtse) (c. 1910 – 28 September 1991) was a Vajrayana master, scholar, poet, teacher, and recognized by Buddhists as one of the greatest realised masters. Head of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism from 1988 to 1991, he is also considered an eminent proponent of the Rime tradition.

•

•

🔔 Wisdom for Today - Buddhistdoor Global: Teachings from the world of Buddhism and beyond, updated each weekday:

☸️ BDG • Buddhist Door Global website:

•

#Buddism#Mahāyāna Buddhism#Tibetan Buddhism#Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche#Dzogchen meditation tradition of Tibetan Buddhism#Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche#Vajrayana tradition of Tibetan Buddhism#Rime tradition of Tibetan Buddhism

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Just as stars and darkness, light and mirage, dew, foam, lightning, and clouds emerge, become visible, and vanish again, like the features of a dream — so is everything endowed with an individual shape.”

#first there is a mountain#then there is not a mountain#then there just is#diamond sutra#buddhism#Mahāyāna#east asia#chan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Six Classes of Beings

Buddhism teaches that sentient beings cycle repeatedly through saṃsāra, taking rebirth in six main classes or realms. Each of these realms features different levels and types of suffering.

In Buddhist cosmology, one of the three realms of existence is the desire realm. Sentient beings manifest in these classes or realms by means of one of the four types of birth. In the discourses of the Buddha, as well as the commentaries, an emphasis is placed on the cause of rebirth being tied to one’s actions–the law of karma.

Different texts subdivide the sentient beings of the desire realm into either five or six sub-realms or classes. Some early Indian Buddhist schools counted only five classes as they counted the asuras as members of the god realm. In the Tibetan tradition, over time it has become more common to list six classes of sentient beings.

The Six Classes

1. Hell beings

2. Pretas (starving spirits or hungry ghosts)

3. Animals

4. Humans

5. Asuras (Demi-gods)

6. Desire realm gods.

The Buddha taught about the six realms in various discourses, including in the Saleyyaka Sutta in the Pali Canon. In the commentarial tradition, the 4th-5th century CE Abhidharmakośabhāsya contains the most detailed presentation. In this text, the first three classes are described as the three lower realms, and the latter three are known as the higher realms.

The Three Lower Realms

1. Hell Realm (Sanskrit Naraka)

In traditional cosmology, there are four major divisions of hells. Each of those is then subdivided into additional classes. The four main divisions are:

1. Hot hells (8 individual levels)

2. Cold hells (8 individual levels)

3. Neighboring hells

4. Ephemeral or diverse hells

Rebirth in the hells is said to come about as an experience of negative deeds committed due to anger or hatred. Alternatively, accumulating many negative actions of body, speech, and mind can also result in rebirth in hell. Discourses, such as the Devaduta Sutta, offer extensive explanations of the suffering encountered in the hell realms. In that teaching, the Buddha explained typical punishments experienced there:

Then the hell-wardens torture [the evil-doer] with what’s called a five-fold imprisonment. They drive a red-hot iron stake through one hand, they drive a red-hot iron stake through the other hand, they drive a red-hot iron stake through one foot, they drive a red-hot iron stake through the other foot, they drive a red-hot iron stake through the middle of his chest. There he feels painful, racking, piercing feelings, yet he does not die as long as his evil kamma is not exhausted.

Devaduta Sutta, MN130

The hot hells are so-called because beings there suffer from punishing heat. Likewise, the cold hells feature environments of extreme cold. Some texts describe the location of the hot hells as being below Mount Meru(Mount Sumeru), a sacred mountain in Indian cosmology that does not correspond to any known geophysical location. According to some Tibetan explanations, the cold hells are located below the sacred Lake Manasarovar, near Mount Kailash.

Neighboring and ephemeral hells can be experienced in diverse locations and beings inhabiting them experience a wide variety of suffering. Despite the fact that these locations are clearly stated in the texts, in the Mahayana teachings, the hell realms (like all the other realms) are understood to be mindstates that are characterized by a particular type of suffering, rather than actual physical locations.

2. Preta Realm (Starving Spirit)

Just as there are many types of hells, according to the Mahāyāna Saddharmasmṛtyupasthānasūtra (The Noble Application of Mindfulness of the Sacred Dharma), there are 36 different types of pretas:

The monk who has knowledge of the ripening of karmic effects will then ask himself how many realms of starving spirits there are. As he examines this matter by means of knowledge derived from hearing, he will understand that there are, in brief, thirty-six types of such realms. While birth in those realms is always caused by envy and stinginess, the realms are distinguished by distinct ways of thinking, as well as distinct modes of suffering, intention, sustenance, movement, and dwelling. All beings therein are, moreover, physically tormented by hunger and thirst… there are thirty-six classes of starving spirits in all. On a vast scale, one may enumerate infinitely many, in consideration of their distinct forms of intended actions and their different mentalities.

Some pretas live below the earth or in the human realm and interact significantly with human beings. There are also pretas who “move through space” and do not inhabit fixed abodes. In Tibetan explanations, the worldly preta spirits include the fearsome female mamos, which bring disease and warfare into the human realm. Other types of preta include jungpos, which cause droughts and can cause mental disorders in humans.

Pretas can suffer from external, internal, or specific obscurations due to their previous habits of stinginess and desire. They are often described as emaciated beings with scrawny limbs and immense bellies. They may not have heard even the mention of water for eons, and are consumed by burning pangs of hunger and thirst. In addition, they are tormented by harm from others as well as their own mental anguish.

Pretas that suffer from internal obscurations search constantly for food and drink. If they receive even the tiniest bit of food or drink, it bursts into flames when they consume it scorching their internal organs. Or it may poison them immediately upon tasting.

3. Animal Realm

Sentient beings are reborn into the animal realm due to ignorance, specifically to past actions of stupidity, close-mindedness, prejudice, and apathy or indifference. Among the specific causes for rebirth as an animal are telling lies, gossiping, hearsay, breaking precepts, and killing animals.

Animals live in oceans or other bodies of water, on the earth, in trees, in the air, and also in realms of the gods (“scattered animals”). Humans and animals are considered to be separate realms, although they see and interact with each other because their realms overlap. Animals experience the suffering of being slaughtered, enslaved, or beaten. The animal realm is dominated by fear, especially that of being attacked or eaten by other animals or humans.

In The Noble Application of Mindfulness of the Sacred Dharma, the suffering of animals is described:

Those who are born in the animal realm

Are aggressive to each other,

And they catch, kill, and eat one another.

Therefore, get rid of dullness.

A mind harmed by dullness

Will give up spiritual discipline and generosity.

Childish beings fooled by craving

Will be born in the realm of the animals.

Outsiders do not know right from wrong,

What to eat from what not to eat,

Or how to tell the meaningful from the meaningless.

Such people mix up Dharma and non-Dharma.

Since their five senses are dumb and obscured,

Such humans will travel to the animal realm.

The Three Higher Realms

Humans and the asuras (demi-gods) and gods are described as the three higher realms. As mentioned above, some texts describe only five realms, and in those, there are only two higher realms–those of humans and gods.

4. Human Realm

Human beings are described as living on the four major continents and the eight subcontinents according to classic Indian cosmology. Rebirth in the human realm is a result of virtuous karma and is said to be extremely rare. The human realm is also said to be the most ideal for the practice of the Buddhadharma. This is because generally there is a mixture of suffering and happiness that allows for reflection, inquiry, and eventual practice of the path leading out of the six realms, or samsara.

In the Limits of Life Sutra (Sanskrit Āyuḥparyantasūtra), the Buddha provided information on the lifespans of beings in each realm. He explained in vivid detail the stages of human life that illustrate the vagaries of this existence. This presentation assumed a maximum lifespan of one hundred years. He taught:

Monks, during a lifespan of one hundred years, people undergo ten stages. At the first stage, they are infants, feeble and lying on their back. At the second stage, they are children, disposed to playing. At the third stage, as youths, they chase after pleasure. At the fourth stage, they are endowed with physical strength and strong enthusiasm. At the fifth stage, they possess prudence and self-confidence. At the sixth stage, they are experienced and more given to reflection. At the seventh stage, they practice religion with all their heart. At the eighth stage, they are venerable and people of distinction. At the ninth stage, they are old, fragile, and weakened by age. At the tenth stage, life is exhausted and only death remains. Monks, in a hundred years, their lives undergo those ten stages.

Āyuḥparyanta (The Limits of Life)

5. Asura (Demi-god or jealous god) Realm

Indian cosmology situates the asura, or demi-god realms within caverns on the aforementioned central Mount Meru. The demi-gods living above the water line that surrounds the mountain are sometimes counted as animals. This class includes important chieftains such as Rahu who appear in many Buddhist texts. According to the Application of Mindfulness, there are two main types of asuras. Some belong to the class of starving spirits while others belong to the animal realm.

The principal cause of rebirth as an asura is jealousy and past actions motivated by envy, paranoia, grudges, and resentment. Asuras are preoccupied with fighting and quarreling among themselves and with the gods, whose superiority and luxuries they crave.

The status of asuras is not consistent across all texts. Some earlier Indian Buddhist schools included asuras within the god realm. And texts such as the Karmavibhaṅganāmadharmagrantha (The Dharma Scripture “Transformation of Karma”) differ by including the asuras in the lower realms.4

6. God Realm

Within the desire realm, there are six different sub-classes of gods or deities. Two of these sub-classes are described as terrestrial, meaning they are said to be located within the universe atop Mount Meru. The gods in the Heaven of the Thirty-three live at the top of Mount Meru and regularly engage in war with the asuras. The gods in the Abode of the Four Great Kings, the guardians of the four directions, reside on four terraces atop Mount Meru, and atop the seven golden mountain ranges.

The other four god realms are described as celestial abodes located In the sky above Mount Meru. These are delightful realms free of combat with the asuras. The most well-known of these realms is Tuṣita (‘Joyous’), (Tib. Ganden). According to the scriptures, the Buddha remained in Tuṣita heaven until the time was ripe for him to be reborn in the human realm.

Rebirth in the god realm is the result of past wholesome actions. In the Application of Mindfulness (Satipatthana) sutta, the Buddha reminds his listeners that the desire realm gods are not free of suffering due to their intense craving and when their karma is exhausted they will be reborn in the lower realms. The Buddha said:

One must also develop compassion for the six classes of gods in the desire realm. The gods may experience indescribably rich and diverse heavenly pleasures amid their mountains, flatlands, woodlands, and parks, and they may revel in hundreds of thousands of delights together with their divine ladies in lotus ponds and forests, yet, once their karmic actions are exhausted, they suffer the pain of dying, and after that comes life in the realms of hell beings, starving spirits, and animals. Thus, the gods are beings who engage in flawed conduct within cyclic existence. Since they are bound by the extremely tight chains of craving, they are continuously pulled along without ever pursuing the genuine path. As one observes the painful deaths of the gods, one develops compassion for them.

The cycle of existence has the nature of suffering, regardless of the realm in which one takes rebirth. In some realms, the suffering may be more intense than in others, but all are dissatisfactory. The Tibetan master Patrul Rinpoche commented, “Yet all beings bound to the realms of saṃsāra by their desire and attachments, with never a moment’s remorse, will have to undergo still more sufferings in this endless circle.”5 In his classic text, the Kunzang Lamé Shyalung (Words of My Perfect Teacher), Patrul Rinpoche offers detailed descriptions of the unsatisfactory nature of each realm. Buddhist teachers emphasize these shortcomings in order to inspire students to turn their minds toward the Dharma as a refuge. When one understands the defects of saṃsāra, renunciation is easily kindled.

#buddha#buddhist#buddhism#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#amitabha#buddha amitabha#sukhavati#dewachen#enlightenment spiritualawakening reincarnation tibetan siddhi yoga naga buddha

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celestial Buddha Space Lotus Talon Abraxas

Celestial bodhisattvas

Mahāyāna Buddhists believe that celestial bodhisattvas are advanced beings who are no longer bound by the suffering of birth and death, but are not yet fully enlightened Buddhas. The most popular ones are considered to be mahasattva (great truth) bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara (Tib. Chenrizig, Chinese Quan Yin, Jap. Kannon), Tara, and Vajrasattva. These beings can be prayed to for particular needs, such as protection (Tara), and are often portrayed as the attendants of Buddhas.

Devotionalism directed towards bodhisattvas remains the most common form of practice in the Mahāyāna tradition, and it is common for laity to offer incense, food and prayers to these figures. Buddhists believe that bodhisattvas are able to help ordinary beings by transferring their good karma to them. This act creates a feedback loop, because giving selflessly of ones own merit in turn creates more merit, so that they are able to continuously offer their aid. While the worship of bodhisattvas may seem odd to some Westerners who see Buddhism as a religion of pure reason devoid of any “religious” features, it is extremely common and is encouraged by the monastic community as a way for the laity to generate good karma, and to bring about the qualities represented by the bodhisattvas into their minds. For instance, in praying to Avalokiteshvara, bodhisattva of compassion, this quality automatically arises in the mind of the devotee, thius helping to generate what is for Buddhists the most important of traits.

This last feature is also particularly important in the meditative practices of Buddhist tantra, where bodhisattva's are visualized in order to bring their qualities into practicioners' minds. As Powers points out, "such bodhisattvas are not creating a delusional system in order to hide from the harsher aspects of reality. Rather, they are transforming reality, making it conform to an ideal archetype" Celestial bodhisattvas are also credited with starting various tantric lineages, appearing to advanced meditiators in their sambhogakaya (“enjoyment body”) form and initiating them into new practices (such as in the Kagyü school of Tibetan Buddhism).

Mahāyāna Buddhists also believe that these beings can create numerous emanation bodies, which may take any form that they choose. Famous saints are often posthumously said to have been emanations. The most renowned example of this is the Dalai Lama, who is simultaneously the reincarnation of the first Dalai Lama, Gendun Drup (1391-1474 C.E.), and a nirmanakaya of Avalokiteshvara.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are 2 major branches of Buddhism: Theravāda (School of the Elders) and Mahāyāna (Great Vehicle).

Theravāda emphasizes the attainment of nirvāṇa (extinguishing) as a means of transcending the self and its mortal body, therefore ending the cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra). Mahāyāna emphasizes the path of the Bodhisattva toward Buddhahood and the work for the liberation of all beings on earth.

The Theravāda branch is widespread in Sri Lanka as well as Southeast Asia, namely Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. The Mahāyāna branch (which includes the schools of Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren, Tiantai, Tendai, and Shingon) can be found predominantly in Nepal, Bhutan, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan.

The Vajrayāna (Indestructible Vehicle) branch, also known as Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, Esoteric Buddhism, can be a separate branch of Buddhism by itself or a branch within Mahāyāna. Tibetan Buddhism preserves the Vajrayāna traditions of 8th century India and is practised mainly in Tibet, the Himalayan states, and Mongolia.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digimon & Mythology: the Holy Beasts and the Deva

I really like mythology and I really like Digimon, so why not combine them? Talking about the real-world inspirations behind monsters is something I've been doing with Pokemon, so let's give Digimon the same treatment.

Digimon has a lot of special groups whose members share common goals and origins. Two of these groups that are inticately linked to each other are the Holy Beasts (translated to English as the Sovereigns or Harmonious Ones) and the Deva. The Holy beasts are Ultimate/Mega level Digimon who each guard one of the cardinal directions of the Digital World: north, south, east, and west, with a 5th member ruling over the other four and guarding the center. The Deva are a group of 12 Perfect/Ultimate level Digimon that serve the Holy Beasts, with each of the Beasts having 3 Deva that answer to it. The Beast of the center has no Deva.

The Holy Beasts are based on the Chinese legend of the Four Symbols or Sì Xiàng. Other names for them include the Four Guardians, Four Gods, and Four Auspicious Beasts. These are four constellations that are said to represent and guard the four cardinal directions. Some versions of the myth add a 5th member representing the center. While it originated in China, the legend of the Four Symbols spread across East Asia and can now be found in many cultures. The legend reached Japan where it inspired the designers of Digimon. They specifically made the Holy Beasts based on a Japanese variant of the legend where the Four Symbols are believed to guard Kyoto. The Beasts are also associated with seasons and were syncretized into the 5 elements of the Wuxing: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. I will discuss each Digimon and its mythological counterpart below.

The Deva have multiple origins. The name comes from the Devas of Hinduism, benevolent supernatural beings who fought against the evil Asuras. As Hinduism evolved and changed over time, the term took on varying meanings, but still retained the idea that Devas are good. Buddhism adopted the idea when it split off from Hinduism. Buddhist Devas are beings that are more powerful than humans, but are still mortal and trapped in the same cycle of death and reincarnation as humans are. While Devas may be venerated by humans, they are still below the Buddhas. This can be seen in the Digimon Deva who are powerful beings (though not all of them are as benevolent as their mythical counterparts) but still are subordinate to the Holy Beasts. The Deva take the shape of animals from the Chinese zodiac. The names of the Deva come from the Twelve Heavenly Generals. These are Buddhist figures that are the guardians of Bhaisajyaguru, the Buddha if healing and medicine in Mahāyāna Buddhism. This story spread throughout Asia including to Japan, where Bhaisajyaguru is called Yakushi. The Heavenly Generals eventually came to be associated with the animals of the Chinese zodiac, though different traditions disagree on which animal is associated with which general. I think I have tracked down the version used by the Digimon creators, which uses the same animals for the Generals and the Deva. The Deva's names all come from Japanese transliterations of the Generals' original Sanskrit names. In this tradition, each General is associated with a particular weapon. The Deva share this trait, each having a weapon named in Chinese called the Bǎo [weapon name] with Bǎo meaning "treasure". Stragely, the Deva mix up which weapon is associated with which General. I don't know if this was intentional or not. Each Deva also has an attack named after one of the Narakas (hells) listed in the Hindu text Vishnu Purana. More detail on each Deva will be presented below.

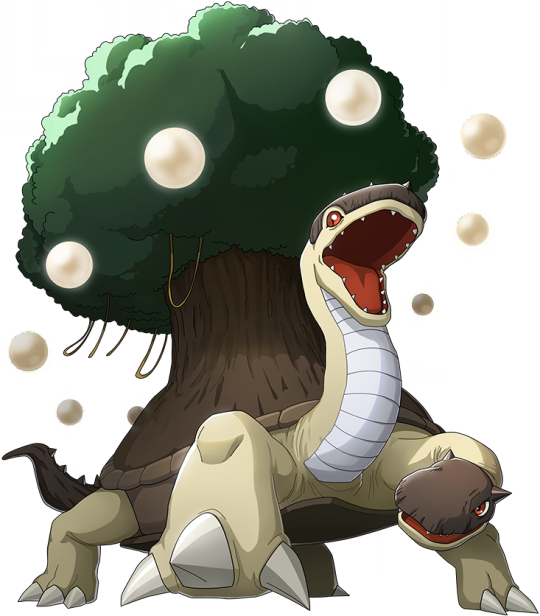

The Holy Beast of the north is Xuanwumon (Ebonwumon in English). It is a gigantic tortoise with two snake-like heads and a tree for a shell. It is based on Xuánwǔ, the Black Tortoise of the Four Symbols. While nearly every depiction of Xuánwǔ depicts it as a tortoise, usually with a snake on its shell, the name actually translates to "black warrior". It is associated with the season of winter and element of water. The snake seen with it is because it was believed that turtles could only mate with snakes and not each other. Yeah, the Greeks weren't the only people who could be hilariously wrong about animals. The snake connection carries over to Xuanwumon, whose heads and necks are those of snakes. Xuanwumon is the eldest of the Holy Beasts and fights using water powers (fitting its mythical counterpart). It is also the least violent of the Holy Beasts and is a philosopher who comes up with zen koans.

The Deva who serve Xuanwumon are Kumbhiramon the mouse, Vajramon the bull, and Vikaralamon the boar. Kumbhiramon is usually depicted as the weakest of the Deva, but is very intelligent, capable of predictions the actions of others, and participates in Xuanwumon's philosophical musings. It is also rather rude and sarcastic while playing up its charming and cute aspects. It's weapon is the Bǎo Chǔ, a vajra (type of Indian club) that it controls with telekinesis. This is one case where its namesake does use the same weapon and it functions as a pun since "chu" is the Japanese onomatopoeia for a mouse's squeak.

Vajramon is the most physically strong of the Deva and is a mighty warrior who seeks truth and honor and despises cowardice. It also aims to rid itself of material and emotional concerns, fitting the Buddhist origins of the Deva. It wields the Bǎo Jiàn, a pair of swords, which fits its legendary counterpart.

Vikaralamon is the largest of the Deva. It is detached, preferring to silently observe the world form a distance and only steps in when it needs to. It may also just be lazy as it sleeps a lot and can sleep with its eyes open. Its weapon is the Bǎo Lún, wheels that it spits out of its mouth and which have different effects depending on what color they are. None of the Heavenly Generals uses a wheel. Its namesake instead uses a sword or vajra. The wheel is a common symbol in Buddhism used to symbolize the cycle of death and rebirth.

The Holy Beast of the west is Qinglongmon (Azulongmon in English), a dragon made of storm clouds. It is based on Qīnlóng, the azure dragon of the east. It is associated with the season of spring and the element of `wood. Xuanwumon seems to have stolen the wood though, given it has a tree on its shell and Quinglongmon has nothing woody about it. Quinglongmon is described as a dispassionate deity who rarely concerns itself with humans or weak Digimon and will only step in when things get serious. This is in contrast to its anime appearances, where it was the most helpful and proactive of the four. Quinglongmon is also a member of the Four Great Dragons, possibly the least utilized group in the franchise. They exist as nothing but a reference to the Chinese Myth of the Four Dragon Kings.

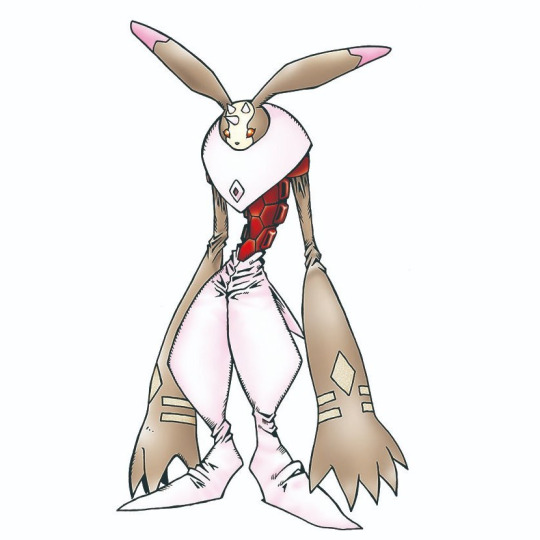

The Deva that serve Quinglongmon are Andiramon the rabbit, Majiramon the dragon, and Mihiramon the tiger. Andiramon (Antylamon in English) is the first of the Deva to debut, predating the group as a whole, though in a different form. There are two forms of Andiramon, Andiramon (data) and Andiramon (virus) with the former being treated as the normal form and the latter being a corrupted version of the Deva as a result of a computer virus. Andiramon (virus) appeared before Andiramon (data). Andiramon is also the only Deva with a dedicated evolution line from Child/Rookie to Ultimate/Mega. Andiramon is a gentle Digimon that loves small and cute creatures and will defend them. Its weapon is the Bǎo Fǔ, which are its own hands transformed into axes. Its mythical counterpart instead uses a mallet or whisk.

Andiramon (data)

Andiramon (virus)

Majiramon is the most capitalist of the Deva. It is extremely greedy and will not lift a finger to do anything that doesn't benefit itself. It also puts a monetary value on everything and will intervene if anything upsets the flow of money. Its weapon is the Bǎo Shǐ, arrows formed from its hair, each of which is worth 5,000 yen. Its associated General is usually associated with bows or spears.

Mihiramon is a scoundrel and a ruffian that enjoys picking fights, but is also the Deva's best strategist and possesses a brilliant tactical mind. Combined with its ability to fly and incredible speed, Mihiramon is one of the best fighters amongst the Deva. Its weapon is the Bǎo Bàng, a three-sectioned staff connected by chains that it can turn its tail into. Think a souped-up nunchuck. Its mythical counterpart uses a vajra instead.

The Holy Beast of the South is Zhuqiaomon. It is based on Zhūquè, the Vermillion Bird of the south. The bird is described as a pheasant with five-colored feathers and that is perpetually covered in fire. Fittingly, its season is summer and its element is fire. Zhuqiaomon is also a flaming bird that attacks with fire. It is the least pleasant of the Holy Beasts, a violent and often cruel god who incinerates those who approach it and rarely helps out others. Fittingly, its sole major anime appearance was as a villain.

The Deva who serve Zhuqiaomon are just as assholeish as their master. They are Indaramon the horse, Pajiramon the sheep, and Sandiramon the snake. Indaramon is a vain asshole that spends its time bragging about talented it is. It even looks down on those who value hard work as it views them as inferior to its natural talent. Despite fussing over its appearance, it is completely unrefined in battle and fights like a berserker. Its weapon is the Bǎo Bèi, a giant gilded conch shell that it uses as a bludgeon and as a horn that can release ultrasonic blasts. Its mythical counterpart instead used a staff

Pajiramon is one of the coolest Deva and one of the evilest. It rules the world of dreams and knows many dark secrets that it divulges to no others. It even avoids the other Deva. While it is described as always calm and yet cruel to others it gives me the impression that the secrets it holds are so dangerous that it must stay away from others at all costs. Its weapon is the Bǎo Gōng, its crossbow that fires arrows which can put others to sleep and trap them in nightmares. It's mythical counterpart also uses a bow.

Sandiramon is the cruelest and most cunning of the Deva. It prefers to draw out fights and kill its enemies in slow and torturous ways. It also lives underground and excels in subterranean combat. Why do snakes always have to be evil? Let us have good snakes damnit. I really don't like it when a group of animals are always or almost always villains in fiction, like sharks, rats, vultures, and snakes. Its weapon is the Bǎo Kuí, spears made of light that it spits out of its mouth. Its mythical counterpart uses a sword or conch shell instead.

The Holy Beast of the west is Baihumon. It is based on Báihǔ, the White Tiger of the West. Báihǔ is associated with autumn and the element of metal. Metal is fitting for Baihumon as it wears metal armor and can unleash a roar that turns targets into metal statues. Baihumon is the youngest and strongest of the Holy Beasts. It is a neutral being that prefers not to get involved in most matters, but is the first Holy Beast to leap into the fight against a powerful enemy.

The Deva that serve Baihumon are Caturamon the dog, Makuramon the monkey, and Sinduramon the rooster. Caturamon has a strong sense of justice and will preside over judgement of others, proclaiming them as good or evil. It's view of justice is very black and white and it doesn't like dealing with situations without a clear good and bad side. It also acts like an older brother to its fellows, something they do not seem to reciprocate. Its weapon is the Bǎo Chuí, a giant hammer it can transform its whole body into. Its mythical counterpart uses swords instead.

Makuramon is interesting it that it almost never speaks and its face remains completely expressionless. This would make its emotions enigmatic, but its body language is extremely expressive, showing it to be hyperactive and extremely curious, though with a short attention span. It dislikes battles and prefers to trap enemies and settle fights nonviolently. This is opposed to its major anime appearance, where it was a total asshole. Its weapon is the Bǎo Yù, spheres that can be used to trap other Digimon. Its mythical counterpart prefers an axe.

The last Deva is Sinduramon, which also sounds like it would be unpleasant to be around. It's a gossip that loves to give insults and pick fights, then it hides inside its armored shell when this inevitably gets it into trouble. I know some people like that and they suck. Its weapon is shared with Kumbhiramon, a vajra called Bǎo Chǔ. Sandiramon's vajra can shoot lightning. Its mythical counterpart also uses a vajra, but a single-pronged one instead of a three-pronged one.

The leader of the Holy Beasts and one of the most powerful Digimon in existence is Huanglongmon (Fanglongmon in English). It is based on Huánglóng, the Yellow Dragon of the Center. It is considered the incarnation of the supreme deity that is the Yellow Emperor and its color represents the earth. It represents the changing of the seasons and the element of earth. Huanglongmon is associated with earth in that it is trapped in the center of the world, from which it observes the Digital World and oversees the other Holy Beasts. In the distant past it was free, but when Lucemon (Digimon's devil) rebelled against God, it trapped Huanglongmon as its first act since its rebellion would have been foiled were Huanglongmon around to oppose it. The imprisonment of Huanglongmon caused the other Holy Beasts to begin fighting for supremacy, but they eventually settled into an equilibrium. Huanglongmon's body is coated in the ultra-rare metal Huanglong ore, which is utterly indestructible. Assimilating Huanglong ore into one's body is a process that takes so long that only Huanglongmon is old enough to actually use it. Huanglongmon is both good and evil, having achieved true balance. If that balance is thrown off, bad things can happen. Specifically, if it leans too hard to evil it will become Huanglongmon Ruin Mode, an unstoppable god of ruin whose rampage was only stopped when the other Holy Beasts restored the balance. This would imply that it also has a mode where it leans too hard to good (Holy Mode? Creation Mode?) but this have never been made official.

Huanglongmon

Huanglongmon Ruin Mode

#digimon#holy beasts#digimon sovereigns#mythology#chinese mythology#hinduism#hindu mythology#buddhism#buddhist mythology#deva#digimon deva#twelve heavenly generals#four symbols#xuanwumon#ebonwumon#quinglongmon#azulongmon#zhuqiaomon#baihumon#huanglongmon#fanglongmon#andiramon#antylamon#vajramon#kumbhiramon#vikaralamon#majiramon#mihiramon#indaramon#pajiramon

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

What "Bodhisattva" even mean? Are they like a messager or middle man?

They are an enlightened being who foregoes nirvana in order to save countless people from the suffering that keeps man trapped in samsara.

This is the official entry in the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (2014):

Bodhisattva (P. bodhisatta; T. byang chub sems dpa’; C. pusa; J. bosatsu; K. posal 菩薩). In Sanskrit, lit. “enlightenment being.” The etymology is uncertain, but the term is typically glossed to mean a “being (SATTVA) intent on achieving enlightenment (BODHI),” viz., a being who has resolved to become a buddha. In the MAINSTREAM BUDDHIST SCHOOLS, the Buddha refers to himself in his many past lifetimes prior to his enlightenment as a bodhisattva; the word is thus generally reserved for the historical Buddha prior to his own enlightenment. In the MAHĀYĀNA traditions, by contrast, a bodhisattva can designate any being who resolves to generate BODHICITTA and follow the vehicle of the bodhisattvas (BODHISATTVAYĀNA) toward the achievement of buddhahood. The Mahāyāna denotation of the term first appears in the AS˙ T˙ ASĀHASRIKĀPRAJÑĀPĀRAMITĀ, considered one of the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras, suggesting that it was already in use in this sense by at least the first century BCE. Schools differ on the precise length and constituent stages of the bodhisattva path (MĀRGA), but generally agree that it encompasses a huge number of lifetimes—according to many presentations, three incalculable eons of time (ASAM˙ KHYEYAKALPA)—during which the bodhisattva develops specific virtues known as perfections (PĀRAMITĀ) and proceeds through a series of stages (BHŪMI). Although all traditions agree that the bodhisattva is motivated by “great compassion” (MAHĀKARUN˙ Ā) to achieve buddhahood as quickly as possible, Western literature often describes the bodhisattva as someone who postpones his enlightenment in order to save all beings from suffering. This description is primarily relevant to the mainstream schools, where an adherent is said to recognize his ability to achieve the enlightenment of an ARHAT more quickly by following the teachings of a buddha, but chooses instead to become a bodhisattva; by choosing this longer course, he perfects himself over many lifetimes in order to achieve the superior enlightenment of a buddha at a point in the far-distant future when the teachings of the preceding buddha have completely disappeared. In the Mahāyāna, the nirvān˙ a of the arhat is disparaged and is regarded as far inferior to buddhahood. Thus, the bodhisattva postpones nothing, instead striving to achieve buddhahood as quickly as possible. In both the mainstream and Mahāyana traditions, the bodhisattva, spending his penultimate lifetime in the TUS˙ ITA heaven, takes his final rebirth in order to become a buddha and restore the dharma to the world. MAITREYA is the bodhisattva who will succeed the dispensation (ŚĀSANA) of the current buddha, GAUTAMA or ŚĀKYAMUNI; he is said to be waiting in the tus˙ ita heaven, until the conditions are right for him to take his final rebirth and become the next buddha in the lineage. In the Mahāyāna tradition, many bodhisattvas are described as having powers that rival or even surpass those of the buddhas themselves, and come to symbolize specific spiritual qualities, such as AVALOKITEŚVARA (the bodhisattva of compassion), MAÑJUŚRĪ (the bodhisattva of wisdom), VAJRAPĀN˙ I (the bodhisattva of power), and SAMANTABHADRA (the bodhisattva of extensive practice). In Western literature, these figures are sometimes referred to as “celestial bodhisattvas.” In Korea, the term posal also designates laywomen residents of monasteries, who assist with the menial chores of cooking, preserving food, doing laundry, etc. These posal are often widows or divorcées, who work for the monastery in exchange for room and board for themselves and their children. The posal will often serve the monastery permanently and end up retiring there as well (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 134).

Also check out the Wikipedia article:

Source:

Buswell, R. E., & Lopez, D. S. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

a question how bad or disrespectful would it be to use the name as king paramita for an oc I really like the way it sounds It sounds like the name of a perfectionist character, someone who always seeks efficiency as a personal goal. I don't know, that's what it transmits to me

Thanks for the question anon! And as far as I'm aware using the name King Paramita for an oc wouldn't be disrespectful at all.

From what little I know the word "Pāramitā" is a Sanskrit term often translated as "perfection," and that it is used in Buddhism to describe the character of enlightened beings, or the paths bodhisattvas must follow to become true buddhas. And you wouldn't be the first to use it for an OC! The author of the unofficial side-journey for Journey to the West called A Supplement to the Journey to the West (published in 1640), after all, involves Sun Wukong meeting his "son" King Pāramitā in an illusion created by a goldfish demon.

So given this, "King Pāramitā" sounds like a pretty good name for an oc who's a perfectionist! That said, if you're still feeling uncertain about it you may want to do more research into Buddhism, and particularly Mahāyāna Buddhism, to get a better sense of how this term is commonly used and why your oc may have that name.

Of course, it again can't be forgotten that "King Pāramitā" is the name of someone's oc from the 1600s who was there to be a "what-if" scenario/mess with Sun Wukong's mind, so take that precedent as you will XD

I'm also linking @journeytothewestresearch's article on the fan children that people have come up with for the Monkey King over the centuries, as it gives more detail into what said oc does in A Supplement to the Journey to the West, as well as gets more into the term "Pāramitā" in Buddhism:

#anon answered#king paramita#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#jttw#xiyouji#supplement to journey to the west

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there any place where I can info on Buddhist monks that I can use. I was trying to find out something and got two conflicting answers

I would recommend documentaries as I have found that to always be a great way to find and consume information, but honestly, you have to remember that there are different schools of Buddhism and there have been changes over the years so if you see different answers, it could be that you were looking at two different groups.

Buddhists generally classify themselves as either Theravāda or Mahāyāna. An alternative scheme used by some scholars divides Buddhism into the following three traditions or geographical or cultural areas: Theravāda (or "Southern Buddhism", "South Asian Buddhism"), East Asian Buddhism (or just "Eastern Buddhism") and Indo-Tibetan Buddhism (or "Northern Buddhism). Hinayana (literally "lesser or inferior vehicle") is a derogatory term to name the family of early philosophical schools and traditions from which contemporary Theravāda emerged, so a variety of other terms are used instead, including: Śrāvakayāna, Nikaya Buddhism, early Buddhist schools, sectarian Buddhism and conservative Buddhism.

Not all traditions of Buddhism share the same philosophical outlook or treat the same concepts as central. Each tradition, however, does have its own core concepts, and some comparisons can be drawn between them.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

BUDDHA SPEAKS

Subhuti, how does a person first feel the need to save beings?

He becomes aware of that kind of wise insight which shows him beings as on their way to destroying themselves. Great compassion then takes hold of him.

He survey the world, and what he sees fills him with agitation. So many carry the burden of actions that bring their own punishment in their wake; others have been born in unfortunate circumstances in which they know nothing of the truth; yet others are doomed to be killed in wars or to be enveloped in a net of false views or to fail to find the way; and there are yet others who have had a fortunate birth and who have begun to find freedom but have lost it again.

So such a person radiated great friendliness and compassion over all these beings and gives his attention to them, thinking, "I would like to save these beings, I would like to release them from all their sufferings." BUT ... He does not make his desire into an attachment, for he never turns his back on full enlightenment. For he know that only when his thoughts are supported by Perfect Wisdom will they bear fruit. Only from the realm of Perfect Wisdom can he point out the path, shed light in darkness, set people free, and cleanse the organs of vision of all beings.

Prajñāpāramitā.

Prajñāpāramitā (Sanskrit: प्रज्ञापारमिता) means "the Perfection of Wisdom" or "Transcendental Knowledge") in Mahāyāna and Theravāda Buddhism.

***

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to read up on mahāyāna buddhism for the philosophy of it. sadly it is still buddhism and suffers from invasive species of white self-help gurus sticking to it like flies

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religion and Jonathan Crane, a compilation.

[It is 3:00 in the morning and I am barely conscious + had yet another mental breakdown and also eating my chemistry teacher alive is starting to look pretty good right about now. So forgive me for any major errors, dropped trains of thought, etc. Just need to get my mind off some things.]

Born and raised Mahāyāna Buddhist, still sticks to this faith in adulthood but mixes aspects of it with his family's native Mo traditions. People too often tend to assume all religions are Abrahamic God-centric, and I find that people in the DC fandom in particular only like the idea of atheist Scarecrow because of that. Granted the Mo do have a singular notion of god, Bu Luotuo, but also do you really think that this guy would respect a singular entity that much? Overall he holds no real belief in anyone/thing proclaiming to be an authority figure while also letting things such as childhood cancer happen, and will fistfight anything at any time ever. [He'll lose, but still.]

TLDR: Animistic polytheist

With Mahāyāna Buddhism there's not so much of an emphasis on reincarnation than there is gaining knowledge/wisdom.

Veryyyyy unsurprising that he is primarily a Huapo worshipper, as well as Me Hoa, as both are Mo goddesses associated with reproduction and reproductive health. Also the entire Mo religion places heavy emphasis on continuing one's bloodline.

Highly superstitious. Honestly, has probably sacrificed a few people to various gods/spirits....who were more than likely like "wtf we don't want these".

Mostly vegetarian when he does bother to eat of his own accord [and cook for that matter], following traditional diet.

Going to hell and is completely fine with that. He knows he's too much of a mess to reach nirvana any time soon if ever. If given a hypothetical [or real] Get Out of Hell Free card, he'd probably just laugh his ass off. But ironically he'd also probably be the most trusted to hang on to it because however much he wants to die and throws himself into dangerous situations, so far no one's killed him. Overall, he just doesn't see the concept of eternal damnation as a big deal, and frequently jokes that "being alive [is] hell enough already".

Has a habit of openly praying when under duress.

Frankly? He doesn't believe suffering can be avoided, and that to believe so is foolish. His entire life has been a series of doors slammed in his face, so it's hardly surprising.

#Where there's smoke there's fire - HEADCANONS#[hi I was raised Shinto lol]#[I also cannot read Zhuang.]#masterpost

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CH. 21 NOTES

⚠️ First, I should preface these notes by saying my knowledge on Buddhism could be entirely incorrect and misinformative. IF I HAVE ERRORED, PLEASE LET ME KNOW!! I am not above or against criticism. In fact, I welcome it immensely. Thank you.

⭐️1.) I have included some facts about orchids from Adriana Picker’s book, “Petal: The World of Flowers Through an Artist's Eye.” This book is fantastic and makes for a great gift idea. The artwork is so aesthetically pleasing. I’ll show some pictures on the Discord server.

⭐️2.) Dishes found in “The Official Downton Abbey Cookbook” by Annie Gray.

⭐️3.) This is not the ‘gotcha’ question Hannah thinks it is. Here she is unknowingly paraphrasing from the first century biography of the Buddha called the Buddcharita written by the Indian poet Ashcaghosa (Clark, 61-62). This biography is believed to record the Buddha’s final actions, however, it is not a sūtra. In Mahāyāna Buddhism there are said to be two influential sūtras detailing the final teachings and death of the Buddha: The Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and the Lotus Sūtra. Both these religious texts are believed to record the Buddha’s final days, but for many Mahāyāna Buddhists - and I’m thinking specifically of the Japanese schools - the Lotus Sūtra contains the highest and most valuable final teachings of the Buddha. Tendai schools stress the superiority of the Lotus Sūtra, believing all other Buddhist sūtras as being, in some categorical way, inferior. However, this does not mean the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra is whole-heartedly discarded from the Tendai canon: “…the Buddha preached the Mahāparinirvāṇa in order to stress his permanence for those who were too slow to grasp sufficiently the teaching of the Lotus Sūtra.”(Williams quoting Hurvitz, 156-157).

Clark, Anthony E. Catholicism and Buddhism: The Contrasting Lives and Teachings of Jesus and the Buddha, 2018, pp 60-61. Cascade Books.

Willliams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations, 1989, pp 156-157. Routledge.

For the sake of theoretical argument, let’s pretend Satoru explains these nuisances to Hannah amidst their conversation.

⭐️4.) It goes without saying, but differing Christian teachings on the Eucharist/Holy Communion are very important when discussing the distinctions between Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Orthodox. They all disagree to a certain extent. Basically it goes like this:

CATHOLICS: Believe in ‘transubstantiation,’ where the bread and wine during Mass undergoes a metaphysical change, becoming the actual body and blood of Christ (substances), while retaining the physical ‘accidents’ of real bread and real wine. Not merely a symbol.

PROTESTANTS: (And I use Protestants sparingly here because Protestant theology varies widely) Essentially upholds that the bread and wine do undergo some type of change, but reject the belief they ‘transubstantiate’ into the actual body and blood of Christ. The bread and wine are taken as symbols and no more.

EASTERN ORTHODOX: Agree with the Catholics that yes, the bread and wine do become the actual body and blood of Christ during consecration, but do not call it ‘transubstantiation.’ This change is a mystery and is therefore beyond human comprehension.

For the sake of theoretical argument, let’s pretend Hannah explains these nuances to Satoru amidst their conversation.

ADDITIONAL NOTES ABOUT THE GOJO FAMILY'S BUDDHISM: Much to my ignorance, I chose Jōdo-Buddhism as the Gojo family’s faith not realizing the long and arduous history of how it first came to be. Essentially there are two main Buddhist schools practiced in Japan (three if you count Zen as its own separate school). These schools are Tendai and Jōdo-shū/Jōdo-Shinshū, with Jōdo-Buddhism being the most widely practiced. However, I’ve already mentioned before that the real Gojo family were (are) not only descendants of Michizane Sugawara, but also aristocrats. Depending on when the Gojo lineage first started, this would indicate they were probably practitioners of Tendai Buddhism, as Tendai not only pre-dated Jōdo, but was only accessible to the noble classes since the peasants couldn’t read or write. When Michizane was later accused of favoring Prince Tokiyo over the crown prince, he was forced into exile and died two years later in 903. However, it is not abundantly clear how close the Gojo line was to Machizane’s direct bloodline at the time, or whether they were exiled along with him. Although, the Gojo family were listed as ‘viscounts’ during the Meiji era (1868-1912), which was considered the lowest rank of Japanese peerage. So either they were exiled for a time and later allowed back into the fold (possibly to assuage Michizane’s vengeful spirit), or they were never exiled and it was only Michizane immediate descendants who got punished??? The Meiji era also sought to abolish Buddhism for Shintoism, so perhaps we can broadly stretch our imaginations and pretend the Gojo line (as Akutami shows it), somewhere, somehow, switched from following Tendai to Jōdo-Buddhism during this unstable religious period. Why? I’ll let you decide. (Please note that I have nothing against Tendai. I literally Google-searched the most popular Buddhist schools in Japan and Jōdo was the first to pop up. I don’t have a strong opinion one way or the other).

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TENDAI AND JODO.

Tendai and Jōdo agree on many things, but here are the primary differences as I (a non-Buddhist) see it.

JAPANESE FOUNDERS

(We could take the easy way out and say ‘the Buddha’ but I’m thinking more as it relates to different schools.)

Tendai: Saichō (767 - 822) with Nicherin (1222-1282) being a huge influence centuries later.

Jōdo-shū: Hōnen (1113 - 1212) ex-Tendai monk.

Jōdo-Shinshū: Shinran (1173 - 1263) disciple of Hōnen. Also an ex-Tendai monk.

RELIGIOUS TEXTS

Tendai adheres primarily to the Lotus Sūtra.

Jōdo-shū/Jōdo-Shinshū adheres to three sūtras: The Larger Sukhavativyuha Sūtra, Meditation Sūtra (Amitavur Dhyana Sūtra), and the Smaller Sukhavativyuha Sūtra. (The Lotus Sūtra can also be included).

BUDDHAS

Tendai: Sakyamuni Buddha (though Lotus Sūtra mentions many other buddhas, including Amida.)

Jōdo-shū/Jōdo-Shinshū: Amida Buddha.

DOCTRINAL TEACHINGS

1. Tendai: Self Power - You alone can reach enlightenment.

1. Jōdo-shū/Jōdo-Shinshū: Other Power - You cannot reach enlightenment on your own in your current human state, and need the guidance of another power (Amida Buddha). ⭐️ It should be noted that Jōdo practitioners believe Amida was given this ability thanks to Sakyamuni Buddha.

2. Tendai: Can reach buddhahood in this life.

2. Jōdo-shū/Jōdo-Shinshū: Cannot reach buddhahood in this life and must wait upon entering the Pure Land in the next life with the help of Amida.

HOW DOES SATORU VIEW HIS BUDDHISM?Only Gege would be able to answer this question to the extent Satoru takes Buddhism seriously. For GTAW, I’ve written him with a mixture of Buddhist thought. On one hand, I’ve incorporated an historic element where Satoru’s family have been practicing Jōdo-Buddhism for almost two centuries, however realistic that sounds. But how personally devoted is he to Amida Buddha? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Don’t know. While it’s true I have him reciting the nembutsu and he hasn’t discarded his family’s Amida butsudan, I haven’t delved too deeply into his faith. I can picture him liking Hōnen and Shinran’s simplicity in teaching the Dharma and their criticisms of the elite upper classes, but I’ve also written him quoting from thirteenth-century Tendai mystics like Kenkō (1283–1350) and expressing a desire to live as a hermit up in the mountains, which is more of a Tendai aesthetic. And the fact he unearths the truth about cursed energy (ie, enlightenment) seems to suggest he has proven that enlightenment can be achieved in one’s current lifetime and does not require Other Power. Or perhaps it is because of Other Power that he was able to reach enlightenment in this lifetime, where he will then be reborn in the Pure Land in the next life? Anyway, this is just my opinion. For all we know he doesn’t give a hoot about religion. I’ll leave these interpretations to you, the reader. My brain hurts enough as it is.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vairocana - Cosmic Buddha Talon Abraxas

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana) is a Cosmic Buddha from Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism.

Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the Avataṁsaka Sūtra, as the Dharmakāya of the historical Gautama Buddha.

In East Asian Buddhism (Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese Buddhism), Vairocana is also seen as the embodiment of the Buddhist concept of Śūnyatā.

In the conception of the 5 Tathāgatas of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism, Vairocana is at the centre and is considered a Primordial Buddha.

Mantra of Light: Oṁ Amogha Vairocana Mahāmudrā Maṇipadma Jvāla Pravartāya Hūṁ

"Praise be to the flawless, all-pervasive illumination of the great mudra (or seal of the Buddha). Turn over to me the jewel, lotus and radiant light."

15 notes

·

View notes