#LitReview

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

🚀How to use Google Scholar like A Pro

Want to take your research game to the next level? 📈 Don't keep these powerful Google Scholar hacks to yourself - share the knowledge!

Follow @everythingaboutbiotech for more useful post.

#GoogleScholar#ResearchSkills#PhDLife#AcadTwitter#CitationGoals#LitReview#InfoPro#CiteRight#ScholarlyPapers#FreeArticles#KnowledgeIsPower#ScienceTwitter#AcadChatter

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literature Review

Click here for a PDF of the edited, complete literature review

Below is an earlier DRAFT

1.The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art by Christopher Johnstone

2. Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings) Essay by Dr. Linda Tyler

3. Can Gardens Mean? Essay by Jane Gillette

4. Lucian Freud's Paintings of Plants - from Symbolism to Truth webinar by Giovanni Aloi

Molly Timmins - Literature review Entry 1 [DRAFT]

The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art

Author: Christopher Johnstone

Published by: Randomhouse New Zealand. 2008.

The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art showcases over 100 paintings in which gardens are the primary subject-matter. Each artwork is accompanied by a written text by Christopher Johnstone, whose past experience as director of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki provides thorough knowledge on these contemporary and historic paintings. The book provides insight into the rich history of artworks sitting behind the core theme of my practice, and allows consideration of where my work may overlap or contrast with these artists.

Some of the featured artists use the garden environment as a central element to their practice; for others it appears as a one-off painting separate from their usual subject. Rita Angus has painted watercolours of flora and gardens many times, alongside Doris Lusk, Frances Hodgkins and Rata Lovell-Smith whom all painted botanicas and gardens in the late 19th and early 20th century. When Angus painted gardens, Johnstone considers this to be for spiritual reasons. He states that her spirituality was

derived from a blend of western and eastern beliefs, including a classical pantheistic tradition that finds presence of God in all living things […] the singular and intense vision that characterises Angus’s watercolours, emphasised by her use of symmetry, can be seen to project and reflect her spiritual relationship with nature. [1]

Gardens can be a place of peace, of cultivation, even identity. To paint a garden, particularly one’s own, can mean painting a portrait of accumulated nature and personal environment. Angus had a particularly strong personal connection to her subjects, shown not only in the sensitivity and length in which she painted them, but in letters to close friend Douglas Liburn in which she recalls seeing herself in a flower, stating “I think I may belong to the iris family one day.” [2]

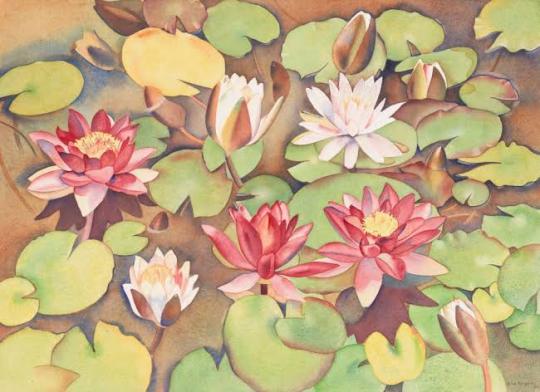

Rita Angus, Waterlilies [3]

During a talk held at at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Te Papa’s Curator for Modern Art Lizzie Bisley spoke about Rita Angus’ connection to nature. She explained that Angus was fascinated with the “cycles of nature, the birth of Spring” [4] and that she found hope and beauty in the “possibility of regrowth […] tightly intwined with her sense as a pacifist and as an artist.” [4] The sensitivity and “huge earnestness”[4] in which Angus approached her paintwork shows a tenderness towards the natural environment, whilst still encountering political statements around pacifism and feminism. Within my own practice, I am also interested in painting botanicas that at times have a delicacy and respect, which may portray a sense of peace and beauty. Within the layers of cultural and societal meanings within gardens that my practice also engages in, I aim to explore nuances of what a garden can mean whether critical or heartfelt.

Looking further back to early-colonisation, the text showcases another stable of women who tended watercolour paintings of gardens in Aotearoa. Martha King is considered Aotearoa’s first botanical artist, whose paintings lack record later in her career because, as Johnstone claims, “it seems her creative energies were diverted towards her noteworthy garden.” [1] Although her paintings studied botanical species as opposed to flourishing gardens, her place in this history is important because of the significance of her work being commissioned for several publications, including the New Zealand Company for Annals and Magazine of Natural History in 1838. [1] This is significant because of gender inequalities of the time, that would often place female painters in a hobbyist category making their efforts not for public consumption.

Margaret Stoddart, Godley House, Diamond Harbour [5]

With the introduction of Impressionism later in the 19th century, Aotearoa artists Mabel Hill and Margaret Stoddart utilised the loose brush-marks and rich colour palette within their garden watercolours, as seen in Europe at the time. Johnstone writes that this was during a period in which early modernism was not welcomed into Aotearoa. He uses the example of Stoddart, who “sent works for exhibition but in 1902 The Press commented that ‘her taste for a woolly misty impressionism has fallen upon her to the detriment of her work.’”1 Johnstone also points out that “this is impressionism with a small ‘i’; a kind of shorthand signalling that a painting was ‘modern’ or influenced by European art.” [1] Alongside the poor reception of modernism in general, critique of Stoddart and Hill’s work was likely to do with the gender of these artists, and the unbalanced hierarchies within the art world at the time. A similar parallel can be seen within the Abstract Expressionist art-movement of the 1950s, a period largely taken up by men, which has been followed more contemporaneously by abstract female-painters such as Laura Owens, Cecily Brown, Emily Karaka among many others reclaiming space for women within the art world.

Johnstone focuses on colonial-style gardens in his text. He references the term ‘gardenesque,’ [6] coined by John Loudon in the first issue of Gardener’s magazine in 1826 “to describe a style that distinguished gardens as works of art rather than imitations of nature.” [1] This terminology considers only a particular type of garden to be ‘gardenesque.’ Ornamental shrubbery, geometrical layout and specific use of only exotic plants deserve the adjective, so as to not be confused with the wildness of nature.

Example of a ‘gardenesque’ style garden [7]

Johnstone then quotes Loudon’s book The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion in which Louden advised a geometrical garden style for countries “in a wild state because gardens should be recognisable as works of art and not mistaken for wild nature.” [6] Johnstone’s inclusion of the latter quote seems to point out a contradiction within coining the term ‘gardenesque,’ and the suggestion of wilderness within specific countries. It points to an elitism and Euro-centric ideologies that pervade certain gardens. Similar generalisations are made today, as with EU foreign-policy chief Josep Borrell’s 2022 speech, in which he used a garden as a metaphor for Europe’s superiority.[8]

Europe is a garden. We have built a garden. Everything works. It is the best combination of political freedom, economic prosperity and social cohesion that the humankind has been able to build […] Most of the rest of the world is a jungle, and the jungle could invade the garden. [8]

For gardens to still represent such neo-colonial ideas nearly 200 years after European settlement in Aotearoa shows deeply ingrained ideologies and biased symbolism both culturally and societally. I am interested in reconsidering some of the symbolism and finding nuances within gardens and the language that represents them.

It is not a coincidence that many of these artists who return to the garden as a subject, are passionate gardeners who enjoy being immersed in the lively curated environment. I am interested in the parallels between painter and gardener, and not only how garden curation itself may mimic a painted composition, but how paint may reflect the artist’s environment. Author of the 1921 book Pictures in a New Zealand Garden, Barbara Douglas, is quoted in Johnstone’s text to say

Every woman who is interested in the beauty of her garden must realise the important part played by the judicious massing of colour. She may not be an artist with canvas and brush, but in her carefully planned garden she will be the possessor of a gallery full of exquisite pictures – pictures which charm and satisfy completely. [9]

Of the many metaphors involving gardens, the symbolic parallel between painting and gardening is perhaps the most fruitful. A painter divides space, arranges or mixes colour, and tends the paint upon the canvas as a gardener does to their blooms. I am interested in emphasising this relationship

Bibliography

[artwork] Angus, Rita. Waterlilies, 1950. Watercolour on paper. 391mm x 286mm. Te Papa collection, Wellington.

Image retrieved from: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/330128

Angus, Rita. Quoted by Tony Mackle in Rita Angus: Life & Vision, 2008.

Bisley, Lizzie. Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist [exhibition talk] Te Uru Contemporary, 2023.

Borrell, Josep. Speech at European diplomatic academy, 2022.

Retrieved from: Retrieved from Youtube: AFP News Agency 'Europe is a garden’ says EU foreign policy chief during speech in Bruges | AFP. Oct 18, 2022.

Douglas, Barbara. 1921. Quoted by Johnstone, Christopher in The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art, 2008

Johnstone, Christopher. The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art, 2008

Loudon, John. Quoted by Johnstone, Christopher. The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art, 2008.

[artwork] Repton Humphry, Flower Garden, Valleyfield. Print. From 'Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening' London, 1805.

Image retrieved from: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/flower-garden-valleyfield/xAGZyrSp_R5mmQ?hl=en

Image retrieved from: https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/blog/collection/2013/07/godley-house-diamond-harbour-by-margaret-stoddart

Molly Timmins - Literature review Entry 2 [DRAFT]

Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings)

Author: Dr Linda Tyler

Essay from Karl Maughan [p.21-32]. 2020. Edited by Hannah Valentine & Gabriella Stead

Published by: Auckland University Press

In the essay Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings), excerpted from the book Karl Maughan, Dr Linda Tyler analyses the early career of the titular artist.

As an associate professor of art history at the University of Auckland, Tyler pays particular interest to the historical and cultural narratives in Maughan’s work. She begins the essay reflecting on gardens as a contextual framework, in which she states that

Gardens are traditionally reinventions of primal forms of nature which serve as subliminal reminders of a world before humanity’s depredations […] they already carry meanings and associations, even before their interpretation by artists. [1]

Tyler considers the garden’s role outside of a painting context, and believes that the environment itself carries significant meaning. The intervention of an environment’s natural growth can say a lot about human domesticity and habits, as well as the resulting garden as an entity. Tyler elaborates that Maughan’s paintings are further translations of these environments, stating that “as nature shaped and trained by human hand, gardens are themselves works of art, however rudimentary, so Karl Maughan’s paintings are art made from art.”[1]

The idea that a garden is itself a transformed depiction of nature, in which painting the subject inherently translates it further, is of interest within my own practice. However, I would disagree in Tyler’s claim that gardens are synonymous with art in a literal sense. A garden environment may at times may have artistic attributes, like the geometric landscaping seen in Victorian gardens, or the painting-like presentation when certain floral colours are arranged (for instance, Marcel Proust’s idea that Monet’s garden is “not so much a garden of flowers, as of colours and tones.”[2]) Despite these artistic features that gardens sometimes possess, and the parallels or metaphors found between a painter and gardener, the act of shaping these environments does not inherently make the environment itself art. ‘Garden’ can sit within a broader territory than art, and occupies a constantly moving and evolving place which is a mixture of domesticity and growing wilderness, or sometimes even sits in a context of imagined and intangible space. Within my practice, I am interested in these conventions but curious to offer nuances to what ‘garden’ may mean both within and outside of these preconceptions.

It is, nonetheless, in the enclosed, familiar spaces of gardens that, often more clearly than in the wider landscape, the shifting patterns and effects of the seasons and weather and atmosphere can be discerned. A garden, whether your own private ground or a public park, is often a constant – a place where you regularly walk, or which you see every day from your window, and where you notice subtle changes. The accessible, familiar, domestic character of the gardens in Maughan’s paintings is a reminder of why the novelist Marcel Proust (1871-1922) referred to the mind of a creative artist as an ‘internal garden’ (Jardin inerieur) [1]

Tyler references Jardin inerieur, the ‘internal garden’ within the mind of an artist. Within her interpretation of Proust’s quote, the garden attended in one’s mind is that of familiarity, and predictability. I am curious to further consider garden in this context as a tension between maintenance and growth, and between control and lack there-of.

Emily Karaka’s The painted dream garden (1991)[3] captures a ‘mind garden’ of sorts. The Abstract Expressionist qualities of the exuberant mark-making in conjunction with controlled coordination and hints of figuration presents ‘garden’ as personality and episodic growth. Comparing Karaka’s portrayal of ‘garden’, to Maughan’s Untitled work from the previous year [4], showcases the variation in what garden can mean in a painting context. While Maughan uses image-based referencing, which presents familiar domestic environments of colonial-style gardens, Karaka’s The painted dream garden considers the adjective of garden and how this can be presented by the physicality of paint itself, creating a tension of control and chaos. Both paintings are gardens, and yet the definition is shifted, showing how the idea garden can be led by interpretation – not grounded in one tangible thing. This is of consideration within my own practice when suggesting characteristics of ‘garden,’ because it is important to do so without claiming singular definition or constraint on the term.

[left] Emily Karaka, The painted dream garden. 1991. [3]

[right] Karl Maughan, Untitled. 1990. [4]

Throughout history, metaphors such as ‘internal garden’ have been used to assign human or un-garden qualities to the word in order to link to a human experience. Hortus colclusus, or enclosed garden, is a term seen in art history since the 14th century within Christian art [5]. ‘Enclosed garden’ seems analogous to ‘internal garden’ in translation, however the interpretation of the term is vastly different. Hortus colclusus is often depicted in paint, as a physical environment background to religious imagery or figures. The impenetrable cloister garden is said to symbolise the virgin Mary [5], and represents a specific interior oppositional to the internal garden visualised by Marcel Proust’s phrase. Both are gardens, one an imagined concept and the other a painted depiction of symbolically manicured enclosed space. These historic terms point to the universal changeability of ‘garden’ as an idea, much like how Maughan and Karaka’s work shows this variation within a painting context.

The domesticity of many gardens can create a sense of familiarity, and could at times be considered an extension of the interior spaces in terms of design and authorship. Karl Maughan is one artist who offers this interpretation of gardens, and has established this in consideration of past landscape painting conventions. I too am interested in the garden environment as an extension of human curation and control – but curious to further navigate environments (tangible or not) that combat this within a painting context.

Bibliography:

Hortus coclusus [term]

Definition retrieved from: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary/hortus-conclusus

[artwork] Karaka, Emily. The painted dream garden. 1991. Oil, acrylic & pastel on 2 sheets of paper, abutted. Purchased 1992 by Te Papa.

Image Retrieved from: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/36334

[artwork] Maughan, Karl. Untitled. 1990. Oil on canvas. 2100 x 1200mm. Purchased 1991 by Christchurch Art Gallery.

Image Retrieved from: https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/collection/91-31/karl-maughan/untitled

Proust, Marcel. How Marcel Proust Praises Artists & Their Visions

Retrieved from: https://www.thecollector.com/marcel-proust/

Tyler, Linda. Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings) Karl Maughan [p.21-32]. 2020. Edited by Hannah Valentine and Gabriella Stead. Auckland University Press

Molly Timmins - Literature review Entry 3 [DRAFT]

Can Gardens Mean?

Author: Jane Gillette

Essay from Landscape Journal [p.85-97]. 2005. Vol.24

Published by: University of Wisconsin Press

In Can Gardens Mean? Jane Gillette critiques landscape designers such as Anne Whiston Spirn who believe in coded meaning within landscape design and gardens [1]. Where this text elaborates, however, is opposing any meaning within gardens beyond a fleeting moment of peace or aesthetic pleasure. A responding essay, Gardens Can Mean written by Professor of Landscape Architecture Susan Herrington[2], offers opposing viewpoints and will be referenced in support of my ideas.

Can Gardens Mean? places emphasis on the interpretations of 'meaning’. Gillette believes that objects only have meaning outside of human influence, stating that “gardens, artifacts, undesigned landscapes, and so forth do not tell, desire, or express anything. Only humans can do that.”[3] The idea of nature existing as an entity, with gardens being a false translation of such, is one I am interested in. For this reason, I can accept the rejection of such meaning, however I disagree with Gillette’s denial of human interpretation or historical influence creating any importance within a garden. She goes on to claim that

Botanical gardens can, of course, be considered as evidence of social largesse as well as shifting cultural paradigms; but to be so considered they require a dedicatory plaque and even more explanatory labelling, perhaps provided by a social historian. [3]

I believe that such information does exist outside of a labelled reference. Histories can be seen within gardens, whether it be of culture (seen in gardening techniques, types of food crops, or design features,) botanicas (viewable without information even if exact identification is not shown,) and industrial evolution (inclusion of plastics, ceramics or other materials).

Gardens can also tell us about human behaviour, both domestically and societally. Where Gillette seems to search for a grand meaning of artistic or philosophical importance in which she finds little evidence, I wonder if the 'meaning’ is instead found in habitual rituals and uses, observed in a garden over time. Socio-economic status is attached too, shown throughout history when the grandness of a garden is displayed as a status symbol, with a forced hierarchy implemented from terms such as ‘gardenesque’ coined by John Loudon to describe “a style that distinguished gardens as works of art rather than imitations of nature” [4]. Although Gillette’s argument does tie to an objective viewing of a garden as an immediate encounter, I would argue that to ask 'can gardens mean’ you must consider the broad range of offerings and how they interrelate.

Granted, these associations are made with prior knowledge to histories and human perception, in which Gillette considers irrelevant to its interpretation. Recalling famous historic gardens, it’s Gillette’s opinion that “nothing at Stourhead [gardens] is complex enough to demand very much attention - especially if we divorce the artifact from its historical information.”[3] Where I would disagree, is her desire to consider the complexity of a garden’s meaning while divorcing it from its history.

Gillette also discusses the fifteenth-century Japanese Zen garden, in which she describes that they exist to “express the unity of all phenomena, spiritual and material, human and nonhuman. This is, conceivably, the only meaning of all gardens, but the Zen garden articulates it”[3] she contradicts some of her past sentiments by adding

Furthermore we frequently see the [Zen] garden backed by a blank wall. This wall provides the equivalent of the background of a painting or a sample of calligraphy so that the elements in the garden can seem like brush strokes on silk. Such devices alert us to the fact that we are seeing a work of art, one that represents an idea [3]

To interpret physical framing of a garden as reference to painting and thus representation of an idea, contradicts the notion of objective meaning detached from cultural association. It seems that the direct representational or symbolic objects within the garden is where Gillette disregards meaning, but perhaps it is not only within symbolism, or coded language, or even the gardener’s intent, in which one can find importance. Instead, importance can be found looking at a garden as a product from centuries of the very human design that also alienates its environmental meaning, even if it is the domestic habit of humans controlling nature as a symptom of “our emotional desire to be at one with the physical universe (or nature.)” [3] The symbolism does not have to be, as mentioned in the article, a school book comparison of “the trees in Jane Austen’s novels express hope because they are green and green is the color of hope.”[3] Instead, I would question what can these varieties of plants and objects suggest about the societal and physical landscape it sits within.

Terminology within a garden context is a crucial element in discussion of what they mean – particularly when relating to interpretation of the word garden itself. Herrington’s oppositional text raises this point, and states that

For Gillette, gardens range from a meadow created in a park, to frog fountains, to conventionally labeled gardens like Stourhead. For Treib, landscapes are referred to as fountains, plazas, memorials, and parks. Both authors admit that they will not define what they are writing about: landscapes and gardens. Perhaps they are nominalists - meaning that they do not believe that gardens or landscapes are defined by any real essences. This is less clear with Gillette because she consistently refers to "the garden" throughout her text as if there is a universal garden that we all share.[2]

When the word garden is used in text, it can be ambiguous because of the vast range of not only physical garden landscapes, but interpretations, whether metaphorical or literal. It seems that within Gillette’s text, she assigns strict criteria to what falls within the definition of a garden, yet shows a lack of clarity of such criteria. Herrington claims that use of “the garden” in this text conjures a universality which is untrue to some, and points to the ambiguity that can come from the word in such context.

If people make gardens to express ideas, we need to ask what idea requires the garden for its full and best expression, an expression that cannot be adequately achieved by some other medium - poetry, say, or the philosophical treatise, the play, the landscape painting.[3]

Comparison to linguistics and artforms is consistent in this article, to which I would argue is a misguided comparison. Where some writers may have made claims in which Gillette is conflicting, she is exaggerating the idea of gardens not being a substitute for art or critique, by concluding that gardens have no meaning at all. In discussion of Aotearoa artist Karl Maughan’s garden paintings; Dr Linda Tyler claims that “as nature shaped and trained by human hand, gardens are themselves works of art,”[5] which flips Gillette’s argument to place gardens in an art context. As written when analysing Tyler’s essay Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings), I disagree with her general categorisation of gardens as art, however her reasons for the claim do, in my opinion, correctly combat Gillette’s denial of expression within these spaces. It also seems that both texts over-generalise the term ‘garden’ in order to support other ideas.

Certain elements of this article are positions I align with in my practice. The above statement in which Gillette proposes that gardens say nothing that cannot be expressed through another art form (which, as mentioned, I disagree with in some parts,) perhaps alludes to the reason I translate gardens through paint. If I believed a garden shows my ideas on its own, I would select photography or installation as the display. The ideas within my paintings, however, are different from ideas that gardens may show. Where painting or writing can translate an interpretation of an environment, the garden itself does not exist to fulfil the same purpose. Gardeners do not always “make gardens to express ideas,”[3] sometimes they do so simply to garden – a verb that perhaps emphasises an episodic space as opposed to singular outcome.

Gillette also explains that gardens are a product of humans trying to imitate nature, a concept I am interested in exploring through my paintings. She explains that once discovering gardening, “human beings had acquired power but only at the cost of consciously experiencing themselves as set apart from the rest of the physical universe, from nature.”[3] I too wonder if gardens can detach people from the environment in which they are trying to replicate, and at times the resulting environment can be a tension or even fight between a gardener and the growing vegetation in which they prescribe a value system. This isn’t always the case, and the term ‘garden’ can invite environments detached from this scenario completely (like the ‘internal garden’ Jardin inerieur within the mind of an artist referred to by Marcel Proust.[6])

Gillette raised ideas around purpose, meaning and symbolism within gardens, and questions whether this exists at all. The text concludes that nothing meaningful lies here other than our interpretations, and specifically disproves of historical importance of these environments. Contrastingly, my practice aims to explore the nuances of ‘garden’ as a term and as a place, and I seek to highlight the histories both of human knowledge and botanical habitats that exist within these spaces. Wild growth and curated design, both of which Gillette deems unimportant, can show deep meaning of human domestic behavior and environmental movement, bringing to consideration where the two may collide or connect.

Bibliography

Gillette, Jane. Can Gardens Mean? Essay from Landscape Journal [p.85-97]. 2005. Vol.24 Published by University of Wisconsin Press

Herrington, Susan. Gardens Can Mean. Essay from Landscape Journal [p.302-317], 2007. Vol. 26. Published by University of Wisconsin Press

Loudon, John. Quoted by Johnstone, Christopher. The Painted Garden in New Zealand Art, 2008

Proust, Marcel. Quoted by Dr Linda Tyler in Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings)

Tyler, Linda. Sunshine, Shadows and Sanctuary (The Early Garden Paintings) Essay from Karl Maughan [p.21-32]. 2020. Edited by Hannah Valentine and Gabriella Stead. Published by Auckland University Press

Molly Timmins - Literature review Entry 4 [DRAFT]

Lucian Freud's Paintings of Plants - from Symbolism to Truth

Giovanni Aloi

Webinar hosted by New York Botanical Garden. 2020

Lucian Freud's Paintings of Plants - from Symbolism to Truth discusses Lucian Freud’s portrayal of plants and gardens within his paintings. Author and curator Giovanni Aloi theorises that Freud observes ‘truth’ within his subjects by offering new ways of looking at plants and our relationship with them.

A key observation throughout this discussion is Freud’s contribution to art history, and the deconstruction of previous botanical art traditions. Aloi explains that “Freud’s paintings of plants stand somewhere between the botanical illustration; the detail, the realism of science - and the symbolic interpretation of painting, of the still life genre.”[1]

The way in which Freud replicates his subject with such unwavering attentiveness to what the plant itself presents, was a new approach from the 19th and 18th century botanical artists. Historically, a botanic illustration involves a

Clarifying approach, a scientific approach that capitalises on the plain background and isolates the botanical object in such a way that it can be appreciated fully, and it can be disentangled from the outside world (…) [an] attempt to extract the work from nature [1]

While Freud commits a level of realism to his artwork, there is also a rawness that confronts the viewer with the plant’s character. More famously known for his nude work and self-portraits, there is a fascinating overlap between the ‘truth’ in which he studies the human body, and the same nakedness which he applies to the plant subject. Freud has referred to his plant paintings as ‘portrait’ artworks [1], and Aloi describes a “desire to get to the bottom, the truth of who somebody might be, but also not to smother the world with metaphors and symbolic meaning that might cloud our vision of plants.”[1]

As well as scientific depiction, there is a history of symbolism within botanic painting in art history. Paintings within the Victorian period, and further back to the vanitas painting movement, saw heavy symbolism within flowers and plants. Aloi explains the downside to this by saying

The contingency of using symbolism to express something through plants, is part of a broader symptom of feeling that nature is not enough throughout the history of humanity, throughout western conceptions of what nature can be. We have to bring voices into plants/animals in order to enrich what otherwise might seem terribly poor. [1]

The anthropocentrism, or human-centric, ideologies seen throughout art history have at times neglected or overlooked the truth within the subject themselves. Lucian Freud questioned this hierarchy, and portrayed plants at times in the foreground of an image, equal or higher to the human within the composition. Aloi describes that by doing this, as well as painting types of plants

that are otherwise seen as mundane, the plant “can be allowed to evade the symbolic representation that we have become accustomed to in art.” [1]

I am interested in how symbolism, or deliberate avoidance of it, can feature in the Aotearoa gardens painted within my own art practice. I wish to achieve a balance between the heavy historical vocabulary of symbolic meaning within plants, and the objective portrayal of them as their own entity. Specific decisions which would inform this reading would be the plant species itself and the background language it carries, but also the painting language in which I apply to it. For example, when Freud paints the yucca tree in Interior at Interior at Paddington (1951) or weeds in his garden studies, he draws attention to the mundane and domestic plants which allows the subject to form its own narrative. The composition which champions the plant-life further pushes it outside of traditional still life conformities and begins asking new questions within the picture.

Interior at Paddington [2]

Although favouring the domestically mundane, Freud at times painted plants layered with personal symbolism and heritage. Lucian’s grandfather, neurologist Sigmund Freud, grew a Sparrmannia Africana plant at his studio in Austria 1 in which he gifted cuttings of to family members. The tree, grown from his own lineage, obtains a new symbolism and tenderness when featured as one of Lucian’s subjects. Whilst it is not immediately evident to the viewer of this plant’s heritage through the painting itself, or even imperative for the viewer to know of this connection, there is an interesting layering of personal coded meaning relatable to many gardeners who carry a story through their own plants. As Aloi puts it, these artworks show

a fascinating way that we can all craft personal symbolism in plants. While the 17th and 18th century applied love to rose, and a poppy implied death, these were religious symbols inscribed by the church in plants. We can all have personal symbols that we can use in plants to keep that plant alive with a meaning that is very intimate.[1]

These ideas around intimacy and personal symbolism are something to consider within my own depictions of personally significant gardens and plants. My family connection to bromeliads, and the specific references to my grandma Hazel, are a key part of balancing the heavy historical narratives of garden painting. It is important to consider plants within art history, while creating a new environment in which the paint itself can at times champion its garden.

Bibliography:

Aloi, Giovanni. Lucian Freud's Paintings of Plants - from Symbolism to Truth. Webinar hosted by New York Botanical Garden. 2020

Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8W-jODjZ-G4

Freud, Lucian. Interior at Paddington. 1951. Oil on canvas, 1143mm x 1524 mm. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK

Image retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/lucian-freud/interior-at-paddington-1951

0 notes

Text

Finished Maurice by E.M. Forster this week and wow, just wow. I thought this was gonna be a hard read because I can struggle with classic lit but even though there were times I was confused with language the overall story flowed well and I was captivated by the young man’s story.

Maurice isn’t always likeable but he is relatable and real. I liked the happy ending but it felt a little rushed with Alec at the end.

I am also in the camp that while Clive was sexually repressed and has a lot of internalized homophobia I think he was probably also asexual.

For a book written so long ago the story stands the test of time. I wish more classic literature were gay… although, some definitely are, they just don’t say it out loud.

#maurice#e.m. forster#cannabis and lit review#litreviews#theweedandread#weed&read#weedandread#booktok#weedreads#book thoughts#book reviews#book review#classics review

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

attempting to get over a hard therapy appointment with a to do list, a spicy latte, and some very loud rock music so behold! a three hour mini work session covering:

HH writeup

Prep cell bio notes

Prep multivariate problem demo

grade math exams

analyze math grades

message proc team

picked up 'tomorrow' (today) with yet more piles and piles of work

CV writeup

module 3 lecture & notes

Obed., Pris., BlueBrown lectures

Single Subject Research module

C&C ch. 3, 5

CritInq sheet 3

LitReview

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I messed up bad. Word acted up and I lost everything I had written for my litreview section. I had finally gotten myself to sit down and do most of it last night after weeks of not being able to do it. I wake up today to finish it before I meet with my supervisor and word glitches and just says fuck all and I can't find it anywhere not even in the recovery logs. I was so close to finishing it as well. Why does this always happen to me. After this happened once a few months ago I mekse sure that I autosav3 all my work but word is a little peice of ahit that is constantly glitching and ended up scrapping it even though im oretty sure i had autosave on (its happend before with something i was writing for a friend as introduction into a fandom). Now it seems very likely that I'll end up completely spiralling in front of my supervisor. (I've managed to get a little bit written again but I had classes today so I only got like 700 words done). I'm not too worried about how he'll react but I can't stop myself from spiralling. Guess we'll see how it goes because I have to be there soon.

0 notes

Text

Title: To Kill a Mockingbird

I recently delved into Harper Lee's classic novel "To Kill a Mockingbird," and I was yet again utterly captivated by its timeless themes and poignant storytelling. Set against the backdrop of the Deep South during the 1930s, this Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece offers a profound exploration of morality, racial injustice, and the complexities of human nature.

Narrated through the innocent eyes of Scout Finch, a young girl growing up in the racially segregated town of Maycomb, Alabama, the story unfolds with both heartwarming moments and gut-wrenching revelations. Scout, along with her brother Jem and their friend Dill, becomes entangled in the trial of Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of assaulting a white woman.

What struck me most about "To Kill a Mockingbird" is its unflinching portrayal of prejudice and inequality. Through the trial of Tom Robinson and the character of Atticus Finch, Scout's principled father and the epitome of moral integrity, Lee confronts the harsh realities of racism and social injustice with unwavering honesty. Atticus's unwavering commitment to defending Tom, despite the town's vehement racism, serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of standing up for what is right, even in the face of overwhelming opposition.

Beyond its exploration of racial injustice, "To Kill a Mockingbird" is also a coming-of-age story that resonates with readers of all ages. Through Scout's eyes, we witness her gradual understanding of the complexities of the adult world, as well as her blossoming empathy and compassion for those marginalized by society.

What truly sets this novel apart is its richly drawn characters and lyrical prose. From the enigmatic Boo Radley to the formidable Mrs. Dubose, each character is imbued with depth and complexity, making them feel like old friends by the novel's end. Lee's masterful storytelling and evocative descriptions transport readers to the sleepy streets of Maycomb, where the scorching heat and stifling social norms serve as a backdrop to the unfolding drama.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is a timeless classic that continues to resonate with readers decades after its publication. Its exploration of justice, empathy, and the enduring power of compassion serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of confronting prejudice and standing up for what is right. I can confidently say that "To Kill a Mockingbird" is a literary masterpiece that deserves a place on every bookshelf.

#BookReview #BookRecommendation #BookishThoughts #CurrentlyReading #BookWorms #AmReading #ReadingCommunity #BookishLove #Bibliophile #BookAddict #ReadingList #BookObsessed #PageTurner #BookNerd #BookishLife #LitReview #BookClub #BookishChat #BookishWorld #BookLoversUnite #MustRead #BookishBliss #BookishJourney #BookishFaves #BookishDiscoveries #BookishDreams #inkspire #tokillamockingbird #harperlee

0 notes

Photo

#litreview #philosophy #descartes #philosophymemes #subversivephilosophymemes #nomoreinspirationhenceiam https://www.instagram.com/p/B9FZk_2hp0A/?igshid=1t2fij8lqsfjg

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Choose Your Expert #Academic Editor https://www.editorworld.com/academic-editing #professor #phd #researchpaper #researchhelp #researcher #litreview #literaturereview #dissertation #thesis #gradschool #phdresearch #phdresearcher #womeninacademia #dissertationediting #thesiswriting #proofreadingservice #copyediting #assistantprofessor #academicwriting #phdchat #postdoc #professor #student #universitylife (at Editor World: Proofreading & Editing Services) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkIp9COgzv9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#academic#professor#phd#researchpaper#researchhelp#researcher#litreview#literaturereview#dissertation#thesis#gradschool#phdresearch#phdresearcher#womeninacademia#dissertationediting#thesiswriting#proofreadingservice#copyediting#assistantprofessor#academicwriting#phdchat#postdoc#student#universitylife

0 notes

Text

DIS Paper Using Interviews as Research Methods

This post is about methods and writing.

This week I read some DIS (Designing Interactive Systems) papers which use interivews as research methods. Here I will give some examples and summary of the reading.

The challenge of these interview projects for DIS is that they do not DESIGN anything. Instead, they do plenty of user research as a preliminary step to design. If we just talk about the research from the perspectives of social science or communication without any implications for design, the paper may not be appropriate for DIS.

Emphasize of the goal of the paper as design

“More than just Space”: Designing to Support Assemblage in Virtual Creative Hubs (Luik et al., 2018)

This paper aims to understand interactions at creative hubs, and how this understanding can be used to inform the design of virtual creative hubs. They make it clear in the keywords: informing design and they repeatitvely mention the goad as "inform the design of virtual hubs" for several times in the paper.

We believe that our findings and their analysis through the lens of assemblage will benefit the field of Human- Computer Interaction (HCI) by informing the design of social-technical infrastructures that seek to ...

Our aspiration in conducting this research was to inform the design of interactive technologies that...

Caller Needs and Reactions to 9-1-1 Video Calling for Emergencies

This paper explores how video calling services should be designed through an interview study with people who have called 911 in the past. This paper is merely an interview project. It focuses on the challenge of 911 calling systems and provides implications for future design.

Our overarching goal is to understand how to design ... systems from the perspective of xxx, with an emphasis on matching the technology with xxx needs.

These issues illustrate that designing xxx requires careful design considerations to balance the needs of xxx and xxx.

List the contributions to design

“Hey Alexa, What’s Up?”: Studies of In-Home Conversational Agent Usage

This paper used mixed methods - survey and interviews to explore how people interact with Alexa:

Resulting knowledge will give researchers new avenues of research and interaction designers new insights into improving their systems.

Our contributions are as follows... Additionally, we provide information about the limitations and shortcomings of the technology as it is designed today, and suggestions for how CUIs can be better designed in the future.

Demostrate more design elements

Evaluating and Informing the Design of Chatbots (Jain et al., 2018)

This paper emphsizes more on implications for design.

Here is what they write in the abstract:

We conclude with implica- tions to evolve the design of chatbots, such as: clarify chatbot capabilities, sustain conversation context, handle dialog fail- ures, and end conversations gracefully.

They demonstrate and discuss some interfaces of Messenger app. In the Discussion part, they offer design implications for both chatbot designers and chatbot platform UX designers, as well as potential future usage of chatbots in HCI research. Although the implications are a bit trivial and confined in Facebook Messenger which looks like a usability test, this paper gives more sense of what a design paper would look like (the authors are industry so it quite makes sense).

Examining Self-Tracking by People with Migraine: Goals, Needs, and Opportunities in a Chronic Health Condition

This paper also spent much space to talk about design implications in Discussion section.

Create concept to demonstrate the idea

This kind of paper puts forward a new concept and demonstrate the design of technologies to support it.

Grounding Interactive Machine Learning Tool Design in How Non-Experts Actually Build Models

This paper is different because it not only shows the results of interview, also offers a concept/ framework for future design (the first author herself is a designer). Although it is not a detailed design work with evaluation, the concept has offered enough implications for future work.

Investigating How Experienced UX Designers Effectively Work with Machine Learning

This paper has the same author with the one above. It probes several open questions at the end of the paper, which is also creative.

Social Support Mosaic: Understanding Mental Health Management Practice on College Campus

This paper investigates how emerging adults seek help managing their mental wellness through social support. They define the support network as "the Mosaic of Scoial Support" and discuss the technologies to support it.

Reference

I am too lazy to write this part... will add it in the future.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I feel somewhat inadequate in terms of the number of articles in my lit review—as of now, there are 24, and my classmate just texted me wondering whether “60 articles are too less” lmao

Here’s to vaguely threatening competition I guess. How many articles do you guys generally review for your dissertations/theses?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

hateeeee how the academic term is queer for lgbt studies like . i have never rlly identified w it <- guy who's read too many books as a kid where that just meant 'weird' and then for all these papers i read to go ah yes the queer community....😞

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

January Noon Reads #2&3. @poetryfoundation @zone3press My next reading time of every day is my Noon Reads. And writing time. This is an hour in the day when I step away from my desk and sit elsewhere. I'll walk the dog, do some yoga stretches and pull the kinks out of my back and shoulders and neck and hamstrings. Have a little lunch listening to a little music, and then sit comfortably, fresh coffee in hand, with my noon reading. I'll write in essays and notes and ideas. This is a time when I'll either read bits of several things or a whole book through the week for an hour a day. A little extra on the weekends if need be or break open something new. For January reading I have a variety of reviews, lit magazines, poetry, current events, and even simply a little life and home. #southern #southernpoetry #litmag #litmagazine #litmags #review #reviews #litreview #poetry #lot #literature #literary #januaryreads #read #reading #amreading (you can find at @barnesandnoble #newstand #barnesandnoblenewstand #afternooncoffee #afternoonreading #zone3press #poetryfoundation #book #poems #poet #litjournal #literary #literaryjournal #noon https://www.instagram.com/p/B7ojzhOAGsP/?igshid=19a0avrl7cixe

#2#southern#southernpoetry#litmag#litmagazine#litmags#review#reviews#litreview#poetry#lot#literature#literary#januaryreads#read#reading#amreading#newstand#barnesandnoblenewstand#afternooncoffee#afternoonreading#zone3press#poetryfoundation#book#poems#poet#litjournal#literaryjournal#noon

0 notes

Text

Finished book one, moving onto book two.

Crossing my fingers for this one.

Thoughts ACOTAR have been added to the old post.

First few chapters in….

- so book one she was forced to live with a kind capture and now book two she’s forced to live with a seemingly ‘dark’ capture… book one she falls for the warmth and book too she falls for the darkness? Except we all can tell Rhysand is not bad, dark and night does not equal bad or evil. Essentially we are repeating book one but with pizzazz.

Around half way??

- so the characters are so much more fun and interesting this book. It’s got humour and sass which book one lacked.

- we are tackling sexism folks, buckle up

FINISHED:

- okay I liked this book more than the first, I hear that’s a common experience.

#acotar#theweedandread#weedandread#weed&read#a court of thorns and roses#a court of mist and fury#sarah j maas#litreviews#audiobook

0 notes

Text

Finding literature.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth by Xiaolu Guo

"Fenfang, never look back at the past, never regret, even if there is emptiness ahead." My first novel of Xiaolu Guo as it should be to start off with in her writing journey. A raw & surreal narrative of a young girl named Fenfang who escapes her monotone life back in the nameless village to gain fame as an actress in the big city. Maybe she thought of being one is easy until she learnt it the hard way 🤷🏻 Even with the never-ending background roles and objectifying criticism of her looks, she's still determined to at least survive everyday that she got into script writing as a change in plans. Her story goes on with bad lovers, sexism, cursing, bad decisions and some days of herself watching pirated movies all day or meeting up with Huizi. How Fenfang described her surroundings and feelings seems quite normal but it was emotionally explained then. Her words woke me up from some things that I took lightly in life like when she describes on healing from a certain wound or her parent's appearance after a few years. All in all, Fenfang is a character that a number of us can really relate with. To me, it was relatable in parts of how lost she felt herself in some parts in her life with a dose of loneliness without her boyfriends even though she just wants company, how cynical she may seem along with her ambitious nature & unwillingness to give up on life. I did feel lost in the plot in the middle of the book just as she was but thankfully I've found my way back. I truly felt that in a certain way that Fenfang is finally ready to take on a new challenge in life at the end as she has already made quite an experience in Beijing. It was a content end to a youthful story. Rating : 🌻🌻🌻🌻 https://www.instagram.com/p/B1oYRSODj0Y/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

#bookreview#asianlit#xiaoluguo#litreview#bibliophile#readingandreading#booklover#readingbythemoonbow

0 notes

Photo

Looking for a new way to decorate your office? May I recommend lots of journal articles & a bored dog (who apparently read my research). #litreview https://www.instagram.com/p/BynZNm_Ir67/?igshid=1ihjogpqj60c7

0 notes