#Lanercost Chronicle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I seem to have forgotten to share the link to our Halloween special. Here, have it a few days after Halloween.

----------

What's better than the undead you don't know? The undead that you do! Join us in this Halloween special as we delve into the spooky nature of medieval undead tales and ghost stories, and teach you how to adapt them to TTRPGs!

Join our discord community! Check out our Tumblr for even more! Support us on patreon! Check out our merch!

Socials: Tumblr Website Twitter Instagram Facebook

Citations & References:

Saga Thing: The Tale of Thorstein Shiver -- listen here

Caesarius of Heisterbach. The Dialogue On Miracles. Translated by H. von E. Scott and C. C. Swinton Bland, vol. 2. Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1929.

The Chronicle of Lanercost. Translated by Herbert Maxwell. James MacLehose and Sons, 1913.

Saxo Grammaticus, The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus. Translated by Oliver Elton, vol. 2. Norrœna Society, 1905.

William of Malmesbury. The History of the Kings of England and the Modern History of William of Malmesbury. Translated by John Sharpe. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1815.

William of Newburgh. “The History of William of Newburgh.” The Church Historians of England, edited and translated by Joseph Stevenson, vol. 4. Seeleys, 1856.

#medieval#medieval literature#podcast#maniculum#halloween#undead#icelandic sagas#william of malmesbury#Lanercost Chronicle#william of newburgh#caesarius of heisterbach#ghost stories#d&d#dnd#dungeons and dragons#ttrpg

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TODAY IN HISTORY:

September 11, 1297 - Scots under William Wallace defeat the English at Stirling Bridge

The English force attempted to cross the River Forth via a narrow wooden bridge in front of the Scottish lines. During the fight, under the overwhelming weight, the bridge collapsed. Although vastly outnumbered, the Scottish army routed the English army.

One particularly prominent English knight, Sir Hugh Cressingham, was killed early in the fight, butchered when he fell from his horse. According to legend, Cressingham’s skin was used to make a sheath for Wallace’s sword. The Lanercost Chronicle records that Wallace had "a broad strip [of Cressingham's skin] ... taken from the head to the heel, to make therewith a baldrick for his sword".

On August 23, 1305, Wallace was indicted and condemned to death. There was no trial because he was declared a traitor to the king; Wallace emphatically denied this charge, as he had never sworn allegiance to Edward. That same day he was hanged, disemboweled, and finally beheaded and quartered at Smithfield. Wallace's head was dipped in tar and placed on a spike atop London Bridge and his limbs exposed at Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Perth.

- -

ДЕНЬ В ИСТОРИИ:

11 сентября 1297 года Шотландцы под командованием Уильяма Уоллеса побеждают англичан на Стерлингском мосту

Битва состоялась на реке Фор��. Трудно точно определить, сколько человек сражалось с обеих сторон, но вполне вероятно, что английская армия по численности превосходила шотландцев.

Английская конница была атакована шотландской пехотой на переправе через узкий деревянный мост, который под непреодолимой тяжестью рухнул. Разгром довершила атака легкой шотландской конницы под предводительством Эндрю де Морея, которая переправилась через реку вброд. Эндрю де Морей был тяжело ранен и скончался через несколько дней.

Англичане потерпели полное поражение. Погиб и выдающийся рыцарь, английский наместник и казначей короля Эдварда, сэр Хью Крессингем. Его зарубили в начале боя, когда он упал с лошади. По легенде, шотландцы содрали с него кожу, из которой были сделаны ножны для меча Уоллеса. В "Хронике Ланеркоста" есть запись, что у Уоллеса была «широкая полоса [кожи Крессингема]... отрезанная от головы до пяток, чтобы сделать из нее перевязь для его меча».

23 августа 1305 года Уоллес был осужден как предатель короля, хотя, как он утверждал, никогда не присягал на верность Эдварду. Его повесили, выпотрошили, обезглавили и четвертовали. Голову Уоллеса обмакнули в смолу и, насадив на пику, поместили на Большом Лондонском мосту. Конечности были выставлены в крупнейших городах Шотландии - Ньюкасле, Бервике, Стерлинге и Перте.

#WilliamWallace #StirlingBridge #TodayInHistory #УильямУоллес #Стерлинг #история #history

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

30th November 1335 saw the Battle of Culblean.

A little known battle during the Second War of Scottish Independence, it was fought out between supporters of Edward Balliol and King David II.

We know a lot about the Battles in which Scotland struggled to rid our country of Longshanks and his army, but the history of the years that followed is often overlooked, King Edwards son was soundly beaten at Bannockburn, and we sent him homeward, to think again, but his grandson Edward III had designs on extending his border by stealth, like his grandfather by placing a puppet King on the throne of Scotland, the Battle of Culblean on St Andrew’s Day 1335 was seen as the turning point in the Second War of Independence.

I have covered the story in previous posts, it all started with a win for Balliol at the Battle of Dupplin Moor in August 1332,, then later that year Sir Andrew Murray chased him, half naked back to England, another win for the pretender to the throne at the Battle of Haildon Hill near Berwick on 19 July 1333. His victory was so crushing that King David II and his young Queen fled to France for safety, leaving the country in the hands of Governors.

In return for English support, Balliol granted control of the whole of Lothian, including Edinburgh, to Edward, he had already sworn fealty to the English king the year before. Again Sir Andrew Murray helped depose him and sending him back to his English paymasters, only to return the following year.

Scotland was a divided country over the subject, there were some who thought Edward Balliol was the rightful heir to the throne and if you remember, he had the support of exiled Scots, the Disinherited.

By November 1335, with the help of English troops Balliol held all but 4 Scottish castles, David de Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl, loyal to Balliol, was laying siege to one of them, Kildrummy Castle in Aberdeenshire, which controlled the North East. Among them was the Bruce’s sister, Christian, and wife of Sir Andrew, a constant thorn in Balliol’s side during the Second Wars of Independence, he was also Regent to King David.

Murrray raised an army of about 4,000 to lift the siege, including the Earl of March and Sir William de Douglas. On 29th November the army camped at “Hall of Logy Rothwayne” on the north east shore of Loch Davan. On learning of their approach Atholl abandoned the siege and camped at the east end of Culblean, perhaps aiming for his land of Atholl, to the south.

The battle was described by Wyntoun’s Chronicle. John of the Craig, defender of Kildrummy told Murray of an approach to outflank Atholl, and splitting his forces, on St Andrew’s Day , de Douglas feinted to the front of Atholls army, about 3,000 strong, and de Moray hit them from the flank. Surprised and overwhelmed the pro English army was defeated. According to Boece’s account Atholl himself was killed by Alexander Gordon, the successor to the Lordship of Strathbogie forfeited by Atholl. Some of the survivors took refuge in the nearby island castle of Loch Kinord, but were forced to surrender the following day.

Compared with the other great battles of the Wars of Independence, Culblean was a relatively small affair, and is now largely forgotten. Nevertheless, its size was greatly outweighed by its importance on the road to Scottish national recovery. The Scottish academic and Historian Dr Douglas Simpson passed what might be said to be the final verdict on the battle when he wrote; Culblean was the turning point in the second war of Scottish Independence, and therefore an event of great national importance. Small as it was it effectively nullified the effects of Edward’s summer invasion, ending forever Balliol’s hope of gaining the Scottish throne. Its effects were almost immediately felt. Edward Balliol spent the winter of 1335-6, so says the Lanercost Chronicle; …with his people at Elande, in England, because he does not yet possess in Scotland any castle or town where he could dwell in safety

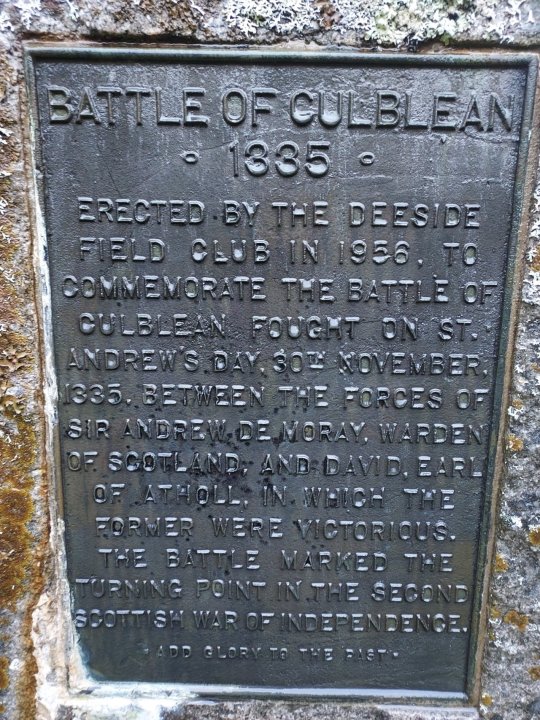

A monolith 13ft high was erected 16th September 1956, by the Deeside Field Club, to commemorate the battle, just off the Tarland-Burn o’ Vat road near the hill where the battle was fought. It reads

“Erected by the Deesside Field Club in 1956 to commemorate the Battle of Culblean fought on St. Andrew’s day, 30 November 1335 between the forces of Sir Andrew de Moray, Warden of Scotland, and David, Earl of Atholl, in which the former was victorious. The battle marked the turning point of the second Scottish War of Independence.”

You can read more on the battle and background here https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2017/01/05/battle-of-culblean/

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"There were contradictory rumours in England about the queen, some declaring that she was betrayer of the king and kingdom, others that she was acting for peace and the common welfare of the kingdom, and for the removal of evil counsellors from the king."

-The Lanercost Chronicle (c.1346) about ISABELLA OF FRANCE, describing her return to England in 1326 with an invading army

#Isabella of France#SO interesting that the duality that has characterized Isabella's historiography across the centuries was present from the very beginning#historicwomendaily#Edward II#14th century#english history#my post#contemporary sources#queue

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw a saying that Isabella from France may not have cheated on her?

Hi, yes! The idea that Isabella had an adulterous relationship with Roger Mortimer has been widely accepted by historians, novelists and commentators for some time but contemporary and near-contemporary records do not unambiguously support it. In recent years some historians, such as Seymour Phillips, Michael Evans and Kathryn Warner, have been more cautious about the idea that Isabella and Mortimer did have an affair.

In some contemporary records, we have the report of rumour - The Chronicle of Lanercost claims "there was a liaison suspected between him and the lady queen-mother, as according to public report" while the unreliable Geoffrey le Baker claimed that Isabella was "in the illicit embraces" of Mortimer. Some sources seemed to describe their relationship in the discourse of royal favouritism (similar language is used to describe the relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston and Richard II and Robert de Vere). Adam Murimuth claimed Isabella and Mortimer had an "excessive familiarity (nimiam familiaritatem)" and another chronicler described Mortimer as her "amasius" (or lover), which is a term used also to describe Gaveston in relation to Edward. Jean Froissart, writing long after the event, even claimed Isabella fell pregnant with Mortimer's child but there is no other evidence for this claim and it's difficult to see how it could have been kept secret.

There is little support in other contemporary chronicles, which often only mention Mortimer in his less scandalous role of councillor of the queen and as a participant in the rebellion. In some cases, euphemistic language might be employed (the Brut describes Mortimer making himself "wonder priuee" with Isabella and Edward II himself wrote Isabella kept Mortimer's "company within and without house" while the report of a story Edward told of an unnamed queen who was disobedient to her husband and deposed, very likely alluding to Isabella, may also be a veiled reference to Isabella's adultery) but we don't know whether a euphemism was intended and we undoubtedly read it in the context where the idea of an affair has not only been raised but has been so widely accepted.

Basically, the evidence does not universally support the idea that they definitely had an affair, much less that they were brazen about it. It does seem like there were rumours about it and that chroniclers perhaps explained Mortimer's rise to power in the same way they explained Gaveston and the Despensers' rise (on that note: we don't know whether Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger were Edward's lovers - it's certainly possible, perhaps even likely, but there's no way to know).

Warner has also argued that Isabella had too much sense of royal dignity to have an affair with a man of Mortimer's rank and that she was too pious to lie to the Archbishop of Canterbury about her desire to return to Edward - but I don't find these arguments particularly convincing. They're too subjective and are reliant on Warner's idea of what Isabella was "really like" while I believe that we don't and can't know what Isabella was really like to make these type of arguments.

Did Isabella have an affair with Mortimer? We don't know. It's possible she did - there is some supporting evidence for it. But the evidence may only be recording of rumours or slander. Where each person feels about the question probably relies on what they think of the narratives about Isabella's affair with Mortimer and what they think Isabella was "really like".

I don't have a strong opinion either way. I can see the argument for and I can see the argument against, and I think we should be cautious about taking the position that one is absolutely more likely to be true than the other. At a distance of 700 years, we have no way to know who Isabella really was and no way to prove or disprove whether she had sex with Mortimer or not.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

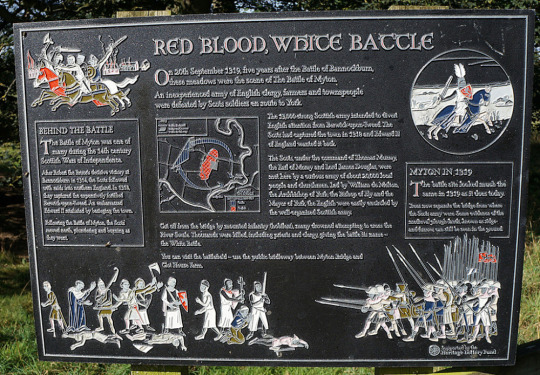

The Battle of Myton - Veteran Scots vs English Priests

The year was 1319, and Scotland’s Wars of Independence were going well for the northern kingdom. A famous victory over the English at Bannockburn five years earlier had cemented the rule of Robert I (Robert the Bruce) and left England on the brink of civil war.

In 1318 the Scots reinforced their success by capturing the vital border town of Berwick. After five years of raids into the north of England, the fall of the heavily fortified town spurred Edward II and his barons into retaliatory action. Along with his queen, Isabella, he mustered the host and marched north, laying siege to Berwick while the queen remained in York.

Despite investing Berwick by land and sea, the Scots resisted, led by Walter Stewart, the High Steward of Scotland. King Robert wished to lift the siege, but knew that engaging Edward’s larger army in a pitched battle would be unwise. Consequently, he dispatched a raiding force led by his foremost lieutenant, the Black Douglas, into Yorkshire, hoping to draw Edward’s attention away from Berwick.

The Scots seemingly had news of the queen's whereabouts, and the rumour soon spread that one of the aims of their raid was to take her captive. As they advanced towards York, she was hurriedly taken out of the city by water, finally gaining refuge further south in Nottingham. Yorkshire itself was virtually undefended and the raiders had an uninterrupted passage from place to place. William Melton, the Archbishop of York, set about mustering an army, which included a large number of men in holy orders. While the force was led by some men of standing, including John Hotham, Chancellor of England, and Nicholas Fleming, Mayor of York, it had very few men-at-arms or professional fighting men.[5] From the gates of York, Melton's host marched out to face the battle-hardened schiltrons, some 3 miles (5 km) east of Boroughbridge, where the rivers Swale and Ure meet at Myton. The outcome is described in the Brut or the Chronicles of England, the fullest contemporary source for the battle;

The Scots went over the water of Solway...and come into England, and robbed and destroyed all they might and spared no manner of thing until they come to York. And when the Englishmen at last heard of this thing, all that might travel-as well as monks and priests and friars and canons and seculars-come and meet with the Scots at Myton-on-Swale, the 12th day of October. Alas! What sorrow for the English husbandmen that knew nothing of war, they were quelled and drenched in the River Swale. And their holinesses, Sir William Melton, Archbishop of York, and the Abbot of Selby and their steeds, fled, and come to York. And that was their own folly that they had mischance, for they passed the water of Swale; and the Scots set fire to three stacks of hay; and the smoke of the fire was so huge that the Englishmen might not see the Scots. And when the Englishmen were gone over the water, so come the Scots with their wings in manner of a shield, and come toward the Englishmen in a rush; and the Englishmen fled, for they lacked any men of arms...and the Scots hobelars went between the bridge and the Englishmen. And when the great host had them met, the Englishmen almost all were slain. And he that might wend over the water was saved; but many were drenched. Alas, for sorrow! for there was slain many men of religion, and seculars, and also priests and clerks; and with much sorrow the Archbishop escaped; and therefore the Scots called it 'the White Battle'...

Many men were pressed into service who were not trained soldiers, including those who were monks and choristers from the cathedral in York. As so many clerics were slain in the encounter, it also became known as the 'Chapter of Myton'. Barbour gives the English loss as 1,000 killed, including 300 priests, but the contemporary English Lanercost Chronicle says that 4,000 Englishmen were killed by the Scots, while another 1,000 were drowned in the River Swale. Nicholas Fleming was among those killed.

The Chapter of Myton had the effect that Bruce was looking for. At Berwick it caused a serious split in the army between those like the king and the southerners, who wished to continue the siege, and those like Lancaster and the northerners, who were anxious about their homes and property. Edward's army effectively split apart: Lancaster refused to remain and the siege had to be abandoned.

The campaign had been another fiasco, leaving England more divided than ever. It was widely rumoured that Lancaster was guilty of treason, as the raiders appeared to exempt his lands from destruction. Hugh Despenser, the king's new favourite, even alleged that it was Lancaster who had told the Scots of the queen's presence in York. To make matters worse, no sooner had the royal army disbanded than Douglas came back over the border and carried out a destructive raid into Cumberland and Westmorland. Edward had little choice but to ask Robert for a truce, which was granted shortly before Christmas.

#myton#battle of myton#scotland#scottish#scottish history#medieval#middle ages#medieval history#14th century

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just read a 13th century story about a bishop who meets a spectral version of King Arthur and, at the end of the night, asks Arthur for a way to prove that he really had met King Arthur. Arthur then gives him the power to summon a butterfly in any season, simply by opening his hand.

Even better, the chronicler doesn't know what this means either: "Let men reflect on what the spirit of King Arthur intended to tell us by this gesture; its relevance to the present day can only be guessed at."

(Chronicon de Lanercost, translated by Andrew Joynes, in Medieval Ghost Stories: An Anthology of Miracles, Marvels and Prodigies)

#it's just such a weird thing a) to give as proof b) for king arthur to give as proof#it's almost certainly a local legend that got associated with a famous figure#i love it

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

19th March 1286: “A Strong Wind Will Be Heard in Scotland”

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

On 19th March 1286, a body was discovered on a Fife beach, not far from the royal burgh of Kinghorn. The corpse was that of a 44-year-old man, and the cause of death was later diversely reported as either a broken neck or some other severe injury consistent with a fall from a horse at some point during the previous night. It is not known exactly when this body was found, nor do we know who discovered it. But we do know that the dead man was soon identified, with much dismay, as the King of Scots himself, Alexander III.

The late king had no surviving children, only a young widow who was not yet known to be pregnant, and an infant granddaughter in the kingdom of Norway. Despite this, Alexander III’s untimely death did not cause any immediate civil strife, although it did set in motion a chain of events which eventually led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. This conflict would forever alter the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and England, as well as the wider course of European history.

Although Alexander III was a moderately successful monarch, he had been unfortunate over the last ten years. His first wife, Margaret of England, had died in 1275 and Alexander initially showed no immediate interest in remarriage. At first the succession seemed secure: Margaret had left behind two sons and a daughter. However the death of the couple’s younger son David c.1281, may have prompted the king’s decision to arrange the marriages of his two surviving children over the next few years. In the summer of 1281, the twenty-year-old Princess Margaret set sail for Bergen, where she was to marry King Eirik II of Norway. Her brother Alexander, the eighteen-year-old heir to the throne, married the Count of Flanders’ daughter in November 1282. Neither marriage lasted long. The queen of Norway died in spring 1283, possibly during childbirth, while her younger brother succumbed to illness in January 1284. Within a few years, a series of unforeseen tragedies had destroyed Alexander III’s family and hopes, and the outlook for the kingdom seemed equally bleak...

All was not lost however. The king was in good health and believed he could count on the support of the realm’s leading men. Steps were swiftly taken to ensure their compliance with his plans for the succession. On 5th February 1284, a few weeks after Prince Alexander’s death, an impressive number of Scottish nobles* set their seals to an agreement at Scone. In the event of the king of Scotland’s death without any surviving legitimate children, they obliged themselves and their heirs to accept as monarch the heir at law. This was currently a baby named Margaret, the only surviving child of Alexander III’s daughter the queen of Norway.

(Drawing based on a seal belonging to Yolande of Dreux, Alexander III’s second queen. She later became Countess of Montfort and, by marriage, Duchess of Brittany. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the bishops of Scotland were to censure anyone who broke this oath, the prospect of the crown being inherited by an infant girl on the other side of the North Sea was obviously not ideal. Her grandfather struck an optimistic note in a letter to his brother-in-law Edward I of England, writing that in spite of his recent “intolerable” trials, “the child of his dearest daughter” still lived and hoping that “much good may yet be in store”. But the king would not leave everything up to chance and in October 1285, at the age of 43, he married the French noblewoman Yolande of Dreux. As the year drew to a close, Alexander might have hoped that his misfortunes were behind him. He still had his kingdom and his health, and now, with a new queen, there was every chance that he could father another son.

In fact, the king had less than six months to live. The exact circumstances of Alexander’s death are shrouded in mystery, although most sources agree on the fundamental details. Only the Chronicle of Lanercost gives a detailed account, although much cannot be corroborated, and its author had a habit of providing moral explanations for historical events. He was convinced that the calamities which befell the Scottish royal house in the 1280s were punishment for Alexander III’s personal sins. The chronicler never explicitly names these sins, but he does hint at a conflict between the king and the monks of Durham (allowing Alexander’s death to be attributed to a vengeful St Cuthbert). The chronicler also included salacious stories of Alexander’s private life, claiming:

“he used never to forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of flood or rocky cliffs, but would visit, not too creditably, matrons and nuns, virgins and widows, by day or by night as the fancy seized him, sometimes in disguise, often accompanied by a single follower.”

Although this does seem to back up the king’s habit of making reckless journeys, alone and in bad weather, the chronicle’s biases are nonetheless fairly obvious. On the other hand, the man who probably compiled the chronicle up to the year 1297 does appear to have had many contacts in Scotland. These included the confessors of the late Queen Margaret and her son Prince Alexander, as well as the latter’s tutor, the clergy of Haddington and Berwick, and the earl of Dunbar. It is unclear how he acquired information about Alexander III’s death, but the chronicle’s narrative is at least plausible and correct in its essentials. Although some of the anecdotes are a little too detailed and didactic to be entirely truthful, the narrative provides some interesting insights into contemporary behaviour, such as the way medieval Scots felt entitled to address their kings. In the absence of alternative narratives, and without necessarily subscribing to the chronicler’s moral views, it is therefore perhaps worth following Lanercost to begin with, supplementing this with additional information where possible.

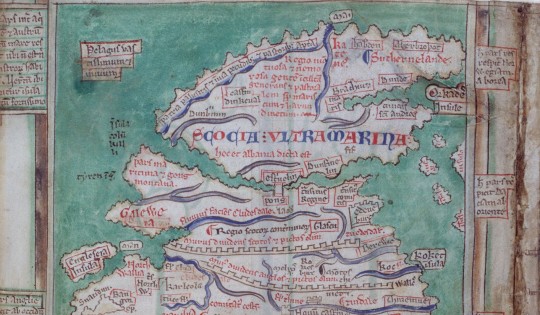

(The northern half of a map of Britain, drawn by the thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris. Matthew Paris was based in the south of England and was not overly familiar with Scottish geography, but his depiction of Scotland as split over two islands and joined only at the bridge of Stirling, is nonetheless enlightening. The map is now in the public domain and has been made available by the British Libary (x))

On the evening of 18th March 1286, Alexander III is reported to have been in good spirits. This was in spite of the weather, which the author of the Chronicle of Lanercost described as being so foul, “that to me and most men, it seemed disagreeable to expose one’s face to the north wind, rain and snow”. The king of Scots was then dining at Edinburgh, attended by many of his nobles, who were preparing a response to the king of England’s ambassadors regarding the aged prisoner Thomas of Galloway. However when the court had finished dinner King Alexander was not at all anxious to retire early. Instead, not in the least deterred by the wind and rain lashing the windows, he announced his intention of spending the night with his new wife. Since Queen Yolande was then staying at Kinghorn in Fife, travelling there from Edinburgh would not only involve riding over twenty miles in the dark, but would also mean crossing the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth. Unsurprisingly, the king’s councillors tried to dissuade him. However Alexander was determined, and eventually he set off with only a few attendants, leaving his courtiers wringing their hands behind him.

The first part of the journey passed without incident and soon the king and his companions arrived at the Queen’s Ferry, by the shores of the Forth. This popular crossing point was named after Alexander’s famous ancestress St Margaret, who had established accommodation and transport for pilgrims there two hundred years earlier. But when the king himself sought passage, the ferryman pointed out that it would be very dangerous to attempt the crossing in such conditions. Alexander, undeterred, asked him if he was scared, to which the ferryman is said to have stoutly replied, “By no means, it would be a great honour to share the fate of your father’s son.” So the king and his attendants boarded the ferry and, notwithstanding the storm, the boat soon reached the shores of Fife in safety. As the king and his squires rode away from the ferry port, intending to complete the last eleven or so miles of their journey that night, they passed through the royal burgh of Inverkeithing. There, despite the evening gloom, the king’s voice was recognised by the manager of his saltpans, who was also one of the baillies of the town.** The burgess called out to the king and reprimanded him for his habit of riding abroad at night, inviting Alexander to stay with him until morning. But, laughing, Alexander dismissed his concerns and, asking only for some local serfs to act as guides, he rode off into the night.

(South Queensferry, as drawn by the eighteenth century artist John Clerk and made available for public use by the National Galleries of Scotland. Obviously the Queen’s Ferry changed a lot between the 1280s and the 1700s, but at least during this period the ferry was still the main mode of transportation across the Forth.)

By now darkness had set in and, despite the local knowledge of their guides, it was not long before every member of the king’s party became completely lost. Although they had become separated, the king’s squires eventually found the road again. However at some point they must have realised that they had a new problem: the king was nowhere to be found.

In the early fifteenth century, local tradition held that Alexander was at least heading in the right direction when he became separated from his companions. Although he too had lost sight of the main road, the king followed the shoreline, his horse carrying him swiftly over the sands towards Kinghorn. It was there, only a couple of miles from his destination, that the king’s luck finally ran out. Since there were no known witnesses to Alexander III’s death, it is unlikely that we will ever know for certain what happened that night. However most sources agree that the king’s horse probably stumbled and threw its rider. Alexander tumbled to the ground and snapped his neck and, at a stroke, the dynasty which had ruled Scotland for over two hundred years came to an end.

It is not known precisely how long the king’s body lay on the beach, alone under the moon while the waves crashed on the shore and confusion reigned among his squires and guides. However his corpse was discovered the next day and was swiftly conveyed to nearby Dunfermline. Ten days later, on 29th March 1286, the kingdom’s ruling elite gathered to see the last King Alexander buried near the high altar of the abbey kirk, in the company of his ancestors. Near the spot where the king’s body was allegedly found, a stone cross was later erected beside the road, which could still be seen by travellers over a hundred years later. The modern belief that Alexander III died when either he or his horse fell from a cliff*** (a tradition which is not supported by any mediaeval sources so far as I am aware) may stem from the position of this old cross, which possibly occupied the same spot as that of the Victorian Alexander III monument. This monument can now be seen at the side of the modern A921 road between Burntisland and Kinghorn, a permanent reminder of the role this seemingly nondescript location once played in the history of Scotland.

(The Alexander III monument near Kinghorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons- the photo was taken by Kim Traynor who has kindly made the image available for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The impact of Alexander’s death on a small mediaeval kingdom like Scotland, conditioned to look to its monarch for leadership, must have been great. Even the Lanercost chronicler admitted that the general populace was observed “bewailing his sudden death as deeply as the desolation of the realm.” However it is important not to exaggerate the scale of the crisis. Popular views of Alexander III’s death are inescapably informed by the accounts of fourteenth and fifteenth century writers, who depicted it as the root of all of Scotland’s later ills.

Writing in the aftermath of a century dominated by war, plague, famine, and climate change, it is perhaps unsurprising that many late mediaeval chroniclers looked back on Alexander III’s reign as comparatively peaceful. As the author of the fourteenth century “Gesta Annalia II” explained, “How worthy of tears and how hurtful his death was to the kingdom of Scotland is plainly shown forth by the evils of after times.” Meanwhile, in his “Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland” completed c.1420, Andrew Wyntoun portrayed Alexander’s reign as a Golden Age of peace and justice (when, just as importantly, oats only cost fourpence a boll). He incorporated an old song into his chronicle, perhaps written in the years following the king’s accident, which neatly encapsulates later views of the event and its impact:

“Quhen Alysandyr oure Kyng wes dede

That Scotland led in luẅe and lé,

Away wes sons off ale and brede,

Off wyne and wax, off gamyn and glé:

Oure gold wes changyd in to lede.

Cryste borne in to Vyrgynyté,

Succoure Scotland and remede,

That stad [is in] perplexyté.”

Wyntoun’s younger contemporary Walter Bower, author of the “Scotichronicon”, also lamented Alexander’s premature death and even rolled out a legend about Scotland’s famous seer, Thomas the Rhymer, to reinforce his point. On 18th March 1286, he claimed, the earl of Dunbar “half-jesting” asked the Rhymer for the next day’s weather forecast. True Thomas answered gloomily:

“Alas for tomorrow, a day of calamity and misery! Because before the stroke of twelve a strong wind will be heard in Scotland, the like of which has not been known since long ago. Indeed its blast will dumbfound the nations and render senseless those who hear it, it will humble what is lofty and raze what is unbending to the ground.”

The next morning came and went without any gales, so the earl decided that Thomas had gone mad- until a messenger arrived at precisely midday with news of the king’s death. Although Bower may have been attempting to bolster Thomas of Erceldoune’s reputation as a prophet (in response to English propagandic use of Merlin’s prophecies), the anecdote reveals the significance he attached to Alexander III’s death. Similarly for John Barbour, author of the fourteenth century romance “The Bruce”, there was no doubt that the story of his hero’s story began, “Quhen Alexander the king was deid / That Scotland haid to steyr and leid.” Following this, Barbour skips ahead to the selection of John Balliol as king, dismissing the six years in between as a time when the country lay “desolate”. In this way later chroniclers created the impression of an Alexandrian ‘Golden Age’ and that Scotland almost immediately descended into chaos after his death. Though understandable, these late mediaeval interpretations have traditionally hampered analysis of Alexander’s reign and the events of the decade following his death, despite the best efforts of modern historians.

(The coronation of the young Alexander III at Scone, as depicted in a manuscript version of the fifteenth century “Scotichronicon”, compiled by the Abbot of Incholm, Walter Bower. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In reality, while the king’s death was undoubtedly a deep blow, the Scottish political community rallied in the immediate aftermath. In April 1286, parliament assembled at Scone and promised to keep the peace on behalf of the rightful heir to the kingdom. Six ‘Guardians’ were to govern in the meantime- two bishops (William Fraser of St Andrews and Robert Wishart of Glasgow), two earls (Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan and Duncan, earl of Fife), and two barons (John Comyn of Badenoch and James the Steward). Despite the oaths sworn to Margaret of Norway two years earlier, there may have been some doubt as to who the “rightful heir” actually was. Certain sources claim that Alexander III’s widow Yolande of Dreux was pregnant and the political community waited anxiously for several months before the queen gave birth in November 1286. However no male heir materialised**** and by the end of the year it seems to have been generally acknowledged that the three-year-old Maid of Norway was the rightful “Lady of Scotland”. She was destined never to set foot in Scotland, but, despite her age, gender, and absence from the realm, the country did not descend into complete anarchy in the four years when she was the accepted heir to the throne. Undoubtedly there were people who had reservations about her reign: the Bruces, for example, seem to have attempted a short-lived rebellion, though the situation was soon defused by the Guardians. By 1289 the cracks were perhaps beginning to show, with the death of the earl of Buchan and the murder of the earl of Fife removing two Guardians, who were not replaced. Nonetheless, the authority of the Guardians was recognised in the absence of an adult ruler and they generally attempted to govern competently in the four years between Alexander III’s accident and the Maid of Norway’s own death in 1290.

Having received news of this second tragedy, the Guardians again acted cautiously, deciding that rival claims for the kingship should be judged in an official court chaired by a respected and powerful arbitrator. Thus they appealed to Scotland’s formidable neighbour, Edward I of England. Despite later allegations of foul play, the English king’s eventual judgement in favour of John Balliol does appear to have been consistent with the law of primogeniture and due process. It would take years of steady deterioration before war finally broke out in 1296. By then Alexander III had been dead for a decade, and though the crisis may have indirectly grown out of his demise, it was not necessarily the immediate cause of Scotland’s late mediaeval woes. Nonetheless the events of that dark night in March 1286 would leave their mark on the popular imagination for centuries, shaping Scottish history down to the present day.

(An imprint of the Great Seal used by the Guardians of Scotland following Alexander III’s death. Reproduced in the “History of Scottish seals from the eleventh to the seventeenth century”, by Walter de Gray Birch, now out of copyright and available on internet archive)

Additional Notes:

*The assembled magnates included the earls of Buchan, Dunbar, Strathearn, Atholl, Lennox, Carrick, Mar, Angus, Menteith, Ross, Sutherland, and two other earls whose titles are illegible but who may have been Caithness and Fife. The barons included Robert de Brus the elder (father of the earl of Carrick and grandfather of the future Robert I), James Stewart, John Balliol (the future king), John Comyn of Badenoch, William de Soules, Enguerrand de Coucy (Alexander III’s maternal cousin), William Murray, Reginald le Cheyne, William de St Clair, Richard Siward, William of Brechin, Nicholas de Hay, Henry de Graham, Ingelram de Balliol, Alan the son of the earl, Reginald Cheyne the younger, (John?) de Lindsay, Simon Fraser, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, Angus MacDonald, and Alan MacRuairi, among others.

** The historian G.W.S. Barrow identified this figure as Alexander the saucier the master of the royal sauce kitchen and one of the baillies of Inverkeithing.

*** There are some variations on this local tradition too- in 1794, the minister who wrote the entry for Kinghorn parish in the Old Statistical Account claimed that the ‘King’s Wood-end’ near the site of the current Alexander III monument was where the king liked to hunt and that he fell from his horse while on a hunting trip.

****The Guardians and other nobles may have assembled at Clackmannan for the birth. Several modern historians have accepted Walter Bower’s statement that the queen’s baby was stillborn, despite the Chronicle of Lanercost’s somewhat fantastic tale of a fake pregnancy, with Yolande being caught conspiring to smuggle an actor’s son into Stirling Castle.

Selected Bibliography:

- “The Chronicle of Lanercost”, as translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, Volume 2, ed. Joseph Bain

- Rymer’s “Foedera…”, Volume 1 part 1

- “Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland”, vol 1., ed. Joseph Stevenson

- “Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson (especially Annals of Worcester; Thomas Wykes; Chronicles in Annales Monastici)

- “Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson (esp. Chronicle of Holyrood, various continuations of the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland; John of Evenden; Nicholas Trivet)

- “The Flowers of History… as Collected by Mathew of Westminster”, ed. C.D. Yonge - Gesta Annalia II (formerly attributed to John of Fordun) in “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W. F. Skene

- John Barbour’s “The Brus”, ed. A.A.M. Duncan

- “The Orygynale Cronikil of the Scotland”, vol.2., by Andrew Wyntoun, ed. David Laing

- “A History Book for Scots: Selections from the Scotichronicon”, ed. D.E.R. Watt

- “The Authorship of the Lanercost Chronicle”, by A.G. Little in the English Historical Review, vol. 31 no. 122, p. 269-279

- “The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

- “Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland”, G.W.S. Barrow

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1230-1371”, Michael Brown

I have extensive notes so if anyone needs a reference for a specific detail please let me know.

#Scottish history#British history#Scotland#thirteenth century#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#1280s#Alexander III#Yolande of Dreux#House of Canmore#Margaret of England#Margaret Maid of Norway#Margaret of Scotland Queen of Norway#Prince Alexander (d.1284)#Edward I of England#William Fraser Bishop of St Andrews#Robert Wishart Bishop of Glasgow#John Comyn of Badenoch#Alexander Comyn Earl of Buchan#James the Steward#Duncan Earl of Fife (d.1288)#Chronicle of Lanercost#Patrick III Earl of Dunbar#Walter Bower#Scotichronicon#Andrew Wyntoun#John Barbour#John of Fordun#Gesta Annalia II#Sources

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Outlaw King Comes To Berwick

And so the Hollywood/Netflix circus has been in town to film The Outlaw King, starring Chris Pine, Florence Pugh, and James Cosmo among others. One star that sadly may not, for many, shine as brightly is Berwick-upon-Tweed. Yes, its great fun watching the filming this week and we hope that it will bring some much needed extra income to the town, but the filming locations—the Quayside and the Old Bridge—are the stunt doubles for Glasgow and London Bridge. This is a great shame as Bruce had an important part in Berwick’s medieval past. Let us examine his role.

Early Days

One of many misconceptions is that the Bruce family were Scottish. They started off, like so many of the nobility in Britain as Norman; the name comes from Brix in Normandy. They acquired, and fortified, Hartlepool after the Norman Conquest but were later grated Annandale (in modern Dumfries and Galloway) by King David I of Scotland in 1124.

The story starts in 1286 with the death of King Alexander III and the ensuing Great Cause of 1291. Of the noblemen claiming the Scottish throne there were only two real contenders, John Balliol and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale. (As with so many families, the first names are handed down through the generations which can be confusing. This Robert Bruce was the grandfather of our Robert the Bruce and future King Robert I, who was born in 1274.) The Balliols, who were allied to the Comyns, and Bruces had been spoiling for a fight for some time; John II “Black” Comyn had been a third possible contender for the Scottish throne. In 1295 after members of the Scottish nobility refused to pay homage to Edward I, among them, the Bruces. Following Edward’s demands of the Scots for military assistance, the Scots formed what became known as the Auld Alliance with France. The burgesses of Berwick, the principal Scottish Royal Burgh, latterly signed up to this alliance.

Watch Out Bruce—He’s Comyn For You!

Meanwhile, Edward was attending to “diplomatic discussions” in France which were proving awkward to say the least. While away, the Scots kept their side of the Alliance and made incursions into the north of England. Annandale was attacked by King John (Balliol) and given to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan; the Bruces, evicted from their estates in south-west Scotland sought the safety of England and sided with Edward I. Sensing trouble ahead, Edward I appointed Robert the Bruce’s father, another Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale, as governor of Carlisle Castle. On 26 March 1296, Easter Monday, seven Scottish earls led by Comyn attacked Carlisle. This was to be the first act of aggression in the first Wars of Scottish Independence. However, it was not so much an attack on the English than the Comyn family taking on the Bruces. It was the last straw however and led to Edward returning to England and commanding his army muster in Newcastle and march north. Edward laid waste to Berwick on Good Friday 30th March. Balliol was deposed as King of Scotland.

And so to William Wallace. After his Battle of Stirling Bridge on the 11th September 1297, Wallace was appointed Guardian of Scotland, the first to hold the post during the second interregnum. His men harried the north of England down to Hexham. The English basically abandoned Berwick and one of Wallace’s men, Haliburton, took Berwick and kept it until Wallace returned north in early 1298 after trashing Northumberland. In turn, the Scots abandoned the town by the next Spring pre-empting Edward’s wrath. Wallace was defeated at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 and resigned as Guardian. Bruce and John III “Red” Comyn were appointed joint Guardians of Scotland in his place but Bruce resigned in 1300. He, in turn was replaced by Sir Ingram de Umfraville and William de Lamberton.

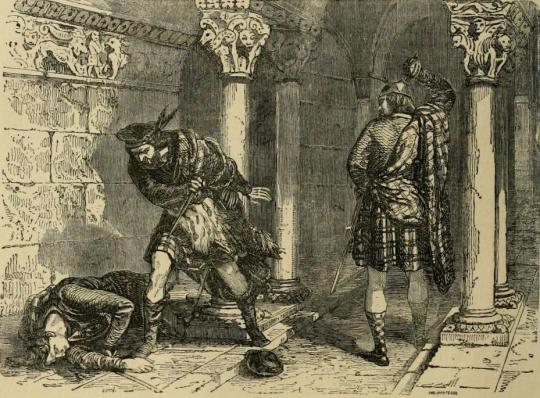

In 1301, Edward launched his sixth invasion of Scotland after which in 1302 many of the Scottish nobility, including Bruce, swore fealty to him. In 1303, Edward launched yet another attack north of the border reaching as far north as Aberdeen. Now, all of Scottish nobility surrendered to Edward, save Wallace, who was eventually captured near Glasgow in 1305 and met a very sticky end. Both Comyn and Bruce still held dearly their claims to the Scottish throne and it was at a meeting between them on 10 February 1306 at the Chapel of the Greyfriars Monastery in Dumfries that Bruce accused the Red Comyn of treachery and murdered him. Bruce then began his claim to the throne through aggression with a successful attack on the English garrison at Dumfries Castle, after which his long time ally Robert Wishart, the Bishop of Glasgow granted him absolution. Nevertheless, he was excommunicated. Some English records suggest that the murder was premeditated and that Edward wrote to the Pope asking for Bruce’s excommunication.

The killing of Comyn in the Greyfriars church in Dumfries, as imagined by Felix Philippoteaux, a 19th-century illustrator.

Six weeks later, Bruce was crowned at Scone near Perth by Bishop Lamberton. Bishop Wishart who had hidden the Scottish regalia was amongst those in attendance. It was traditional that MacDuff, the Earl of Fife performed the ceremony. In the absence of any of the male MacDuffs, Isabella MacDuff claimed the right to perform the ceremony. She arrived at Scone a day late and so a second ceremony was performed.

Edward moved north yet again. He defeated Bruce on 19th June 1306 at the Battle of Methven. Bruce’s wife and other ladies of the court were sent to his brother’s castle at Kildrummy for protection. Bruce and his few followers fled. Alas, there was no safety to be had at Kildrummy. Bruce’s wife Elizabeth, his sisters Christina and Mary, and Isabella MacDuff were captured; his brother, like Wallace before, hanged, drawn and quartered. It was for her part in the crowning of Bruce that Isabella was held prisoner at Berwick Castle. Bruce was declared an outlaw.

The Bruce Comes To Berwick

Edward I died in 1307. His heir, Edward II was a weak ruler, from whom Bruce allegedly said it was easier to gain a kingdom than a foot of land from his father. On 6th December 1313, Bruce made his first attempt to take Berwick. It is described in the Lanercost Chronicle:

“In the night, coming unexpectedly to the castle, he placed ladders against the wall and began to ascend. Unless the loud barking of a dog had made known the arrival of the Scots, he would quickly have taken the castle as well as the town. The ladders, curiously made for the purpose of scaling, were left here, and our men have hung them over the pillory as a public show. So this dog saved Berwick as formerly the cackling of the geese saved Rome.”

By this time Bruce had recaptured most castles from the English. Edward II’s response was to assemble a vast army, complete with provisions for the campaign, at Berwick. This army is said to have consisted of 60,000 foot and 40,000 horse; 3,000 of the latter are said to have been horsemen in complete armour. The King met the army here. Never had such a vast number been mustered in Berwick before of since, but numbers alone do not always bring victory; rather, it ended in a crushing defeat at Bannockburn from whence Edward returned to Berwick alone.

Emboldened, by his success, Bruce attempted another assault on Berwick. The Lanercost Chronicle again:

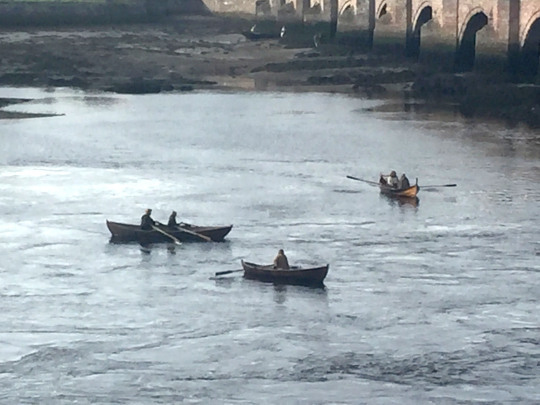

“Within the octaves of the Epiphany, 15th January, 1316, the King of Scotland, with a great army, came secretly to Berwick, and under brilliant moonlight made an attack by land and by sea in skiffs, hoping to have entered the town on the river side between the Bridge House and the Castle, where the walls were not yet built. But by means of watchmen and others through the noise of those attacking they were repulsed, and a certain Scotch soldier, Sir J. de Landels, was killed, and Sir James Douglas with difficulty escaped in a small skiff. And thus the whole army was put to confusion…”

Skiffs battle against the flow of the Tweed

The victory against the Scots was a Pyrrhic one. The town was in dire straits, as was all of Northern Europe, gripped by the Great Famine. Poor harvests due to cold, rainy summers were taking their toll. Letters of the day from the Warden, Maurice de Berkeley give a vivid impression of life in the town for the English garrison:

“Tells [Sir William Ingge] no town was ever in such distress as Berwick short of being taken or surrendered. The garrison are deserting daily, and there are none left in the town, save only such of the garrison of the castle as are not slain or dead of hunger. If the town is lost, the blame will rest on him as one of the King’s chief councillors. Whenever a horse dies in the town the men-at-arms carry off the flesh and boil and eat it, not letting the foot touch it till they have had what they will. Pity to see Christians leading such a life. If he would save the town, prays him to send assistance quickly.”

18 February 1316.

To the king:

“The burghers are deep in debt, and his men are dying of hunger on the walls. He has supplied them out of his own means while he had any. The town was never in such a state, as he has often told the King; but he sees clearly that no order of the latter is obeyed. Whatever his ministers may say to the contrary, there has not come to Berwick, either in money or provisions, since he arrived there, more than £4000, and there are ten weeks short of the year. Of the 300 men-at-arms enrolled, only 50 can be mustered mounted and armed, the rest of the horses being dead, and the arms at pledge for the owners sustenance. He has not had a penny of his own pay since Michaelmas. Begs him to take thought for them and the town, for if he loses it, he will lose all the north, and they their lives. Begs another warden may be appointed, as his term expires a month after Easter, and he will remain no longer. Thinks no attention has been paid to his former letters.”

2 March 1316

The mayor, bailiffs and community of Berwick to the King. Tell him that the town is in great danger, as there are only provisions for one month… Sir Robert de Bruys will be at Melrose before Ascension Day with all his force, and do his utmost, they fear, to annoy them by treason or otherwise…”

10 May 1316

The town was in disarray with a power struggle between the burgesses and the garrison. The Mayor, Walter de Goswik, had “been very much harassed by the keepers of the town appointed by the King”. James Douglas, one of Bruce’s new allies and whom had been part of the unsuccessful 1316 raid, gained intelligence of this confusion. He and Bruce amassed a new army.

Contemporary records tell us that Douglas believed he could gain the trust of one of the garrison and bribe him to assist the Scottish cause. That man was Peter de Spalding. The Scottish poet Barbour records that Spalding:

“…was annoyed at the Governor’s ill-will to the Scotch in the town, and covenanted with Bruce through Marshal Keith to deliver up the town to him if he drew to it during night, and at the Cowgate when it was his turn to watch.”

This he did. Douglas and his men scaled the walls and hid overnight; remember, at this time the Parade/Ravensdowne area had no buildings on it, save for some stores—the King’s Garners—and the old Parish Church. In the morning, all hell broke loose as the Scots plundered the town. After a siege of six days, the castle too capitulated and King Robert strolled into the town. As for Peter de Spalding? His reward for assisting the Scots was not the promised £800 (something in the order of £300K–£400K today) but execution. The following year, Edward attempted to retake the castle but was thwarted by the efforts of the Flemish pirate-cum-siege engineer, John Crabbe. In retrospect, this was a last hurrah for the Scots. The town finally fell after the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 bringing to an end the last time the Scots held Berwick for any great length of time.However, the one last thing that Bruce gave to Berwick before his death in 1329 was the completion of the medieval walls begun by Edward I in 1296.

Braveheart

Since the filming began, I have been asked one or two questions regarding the mythology that surrounds The Bruce. One story in particular that I was asked about was one that the correspondent’s teacher had passed on years ago; that Bruce’s heart had been buried in Berwick.

Bruce died in 1329 near Dumbarton, possibly of leprosy. Robert’s final wish reflected conventional piety, and was perhaps intended to perpetuate his memory. His last regret was not partaking in any crusade. After his death his heart was removed, placed in a silver casket, and taken by Sir James Douglas on a crusade to help Spain regain Granada from the Moors. Sir James and most of the Scottish contingent were killed but his body and the casket were recovered and returned to Scotland. The casket was buried at Melrose Abbey. It was discovered in 1920 and then rediscovered in 1996 when it was forensically examined and deemed to have held human tissue of the correct age. It was reinterred in 1998. Nothing to do with Berwick.

However, Robert did arrange for perpetual soul masses to be funded at the chapel of Saint Serf, at Ayr and at the Dominican friary in Berwick (near the Bell Tower), as well as at Dunfermline Abbey.

It is ironic that arguably the one accurate thing the 1995 Mel Gibson film Braveheart portrayed (the “Braveheart” in question being Bruce’s and has nothing to do with Wallace) was Bruce’s ambivalence, siding with the English against Wallace.

Glasgow Goofs

Now, I’m no historian of Glasgow and I stand to be corrected, but some quick research reinforces my original thoughts regarding Berwick Quayside portraying the Port of Glasgow: would there have been a port in Glasgow in the early 14th century?

The Port of Glasgow as imagined by the film makers. (Courtesy Richard Robinson)

It was (and remains) my understanding that no port on the west coast of Britain became particularly important until the “discovery” of, and eventual trade with, the Americas. Looking at an academic paper which gives tables of economic activity in all the British nations, Glasgow is very important regarding the activity of ecclesiastic houses, but the only port on that coast that gets any mention is Ayr; and the tax returns are minuscule compared to the 30% of all Scottish port customs which is from Berwick. Glasgow became a (non-Royal) Burgh in 1214, 90 years after Berwick became King David’s first Royal Burgh. Glasgow itself wasn’t easily navigable till much later. The original port may have been at Newark which became Port Glasgow. But prior to 1668, Newark was a herring fishing village, centred around Newark Castle which was built in 1478 by George Maxwell of Pollok when he inherited the Barony of Finlanstone. So how the film makers justify this eminence, I have no idea. Let us be charitable and say that its a good looking bit of artistic license for Bruce to meet up with Bishop Wishart. It is an irony that the most important port in Scotland is playing the part of a non-entity! *sighs*

Where’s Wallace?

Another old chestnut reflected in The Outlaw King is the story of what happened to the body parts of the quartered William Wallace which leads me to a criticism of the film. This is a really silly thing about the whole saga. Popular tradition says it was Wallace’s left upper quarter displayed at Berwick, probably on the bridge. The film shows the left arm of Wallace on a merket cross (improbably located on the Quayside. So 9/10 for accuracy if the port is Berwick, but it’s -10/10 if it’s meant to be Glasgow: no body part was displayed there. The other quarters were displayed at Newcastle, Stirling and Perth.

Technicians put the final touches to the remains of Wallace

Finally, let me just reassert for the 94th time that Wallace Green has nothing to do with William Wallace—it’s a corruption of the name given to the area which James Douglas and his men would have, in 1318, been hiding out in—the Walls Green!

Anyway, I join everyone’s pleasure in the entertainment (and money) we have been given by the cast and crew and look forward to seeing the film before posting why comments on the “goofs” section of the IMDb!

Chris Pine looking suitably heroic!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

JOAN OF ENGLAND, QUEEN OF SCOTLAND - (THE JILTED PRINCESS) - (21 June 1221 – 4 March 1238) FAVOURITE HISTORICAL FIGURES

Joan Plantagenet was married to the King of Scots while very young. Due to the vagaries of politics between Scotland and England and conflicts between her husband and her brother, her position remained tenuous. She would be overshadowed by her mother-in-law and never had any children.

Joan was born on July 22, 1210. She was the third child of King John of England and his second wife Isabella of Angoulême. In 1212, Alexander, son of William the Lion, King of Scots was in England and was knighted by King John. Alexander insisted from that point on that King John had promised him his eldest daughter as a wife and that Northumberland would be part of her dowry. In 1214, King William died and Alexander became king. It is most doubtful John would have parted with Northumberland but Alexander persisted with negotiations for Joan’s hand. King John had other plans. His intention was to use the marriage of Joan as an enticement to mend his relations with old enemies on the continent.

King Philip II of France was looking to marry Joan to his son but John spurned this offer and in 1214, she was betrothed to Hugh, future lord of Lusignan and Count of La Marche, as compensation for him being jilted by her mother Isabella. At the age of four Joan was sent to France to be brought up in her future spouse’s court, with the promise of Saintes, Saintonge and the Isle of Oléron as a dowry. Hugh X tried to obtain these same properties by absolute grant prior to their marriage but was unsuccessful. His failed attempt to obtain Joan’s dowry lessened his eagerness to have Joan as a bride at that point.

On the death of John of England in 1216, the queen dowager Isabella decided she should marry Hugh X herself. The government of Joan’s brother, King Henry III, was in serious negotiations for a marriage with Alexander and in May of 1220 asked for Joan to be surrendered at La Rochelle. But Hugh kept her as a hostage in an effort to gain the properties he was promised as Joan’s dowry as well as Isabella’s dower which was being withheld from her by the English. On June 15th, Alexander agreed to marry Joan’s sister Isabella if Joan was not available but upon the intervention of the Pope and assurance of Isabella’s dower, Hugh finally returned Joan to England in the fall.

On June 18, 1221, Alexander officially settled on Joan lands in Jedburgh, Hassendean, Kinghorn and Crail which were worth one thousand pounds. Kinghorn and Crail at that point belonged to Alexander’s mother, Queen Ermengarde so Joan was to receive properties in Ayrshire and Lanarkshire until the other two properties became available. The marriage ceremony was performed on June 19 at York Minster. Joan was nearly eleven and Alexander was just past twenty-two.

There is a suggestion that Joan was not enamoured with Scotland and its society. She was hampered by her youth and had little political influence. Alexander’s mother, Queen Ermengarde was a forceful personality and had more authority at court than Joan. Joan remained childless throughout her marriage (that is not to say that she may or may not have suffered miscarriages or stillbirths in the whole of her marriage as no accounts have survived) and this lack of an heir was a serious issue for Alexander. However, an annulment of the marriage might have caused war with England as both her husband and brother were not on the best of terms and were hindered by strong tensions.

Although, this worked in Joan’s favour as she seemed to have found a purpose and would mediate between the two monarchs. Alexander would often use Joan’s personal letters to her brother as a way of communicating with Henry, while bypassing the formality of official correspondence between kings. One such letter is a warning, possibly on behalf of Alexander’s constable, Alan of Galloway, of intelligence that Haakon IV of Norway was intending to aid Hugh de Lacy in Ireland. In the same letter she assured Henry that no one from Scotland would be going to Ireland to fight against Henry’s interests. Another letter, this time from Henry, was of a more personal nature, written in February 1235 it informed Joan of the marriage of their “beloved sister” Isabella to the holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, news at which he knew Joan “would greatly rejoice”.

In December 1235 Alexander and Joan were summoned to London, possibly for the coronation of Henry’s new queen, Eleanor of Provence. This would have been a long and arduous journey for the Scots monarchs, especially in the deepest part of winter.

Henry’s use of Joan as an intermediary suggests she did have some influence over her husband, this theory is supported by the fact that Joan would accompany Alexander to England for negotiations with her brother King Henry over disputed northern territories in September of 1236 at Newcastle and in September of 1237 at York.

After the York summit, Alexander agreed by treaty to drop his claims and returned to Scotland. Joan and her sister-in-law Eleanor of Provence agreed to go on pilgrimage to Canterbury together to visit Thomas Becket’s shrine. Given that Joan was now 27 and Eleanor already married for 2 years, it is possible both women were praying for children, and an heir.

The chronicler Matthew Paris suggests that Joan and Alexander may have become estranged at this point as Joan wished to spend more time in England at her brother’s court. In 1236, Henry did provide her with manors in Driffield, Yorkshire and Fen Stanton in Huntingdonshire where she could take refuge if needed. Joan may have known she was gravely ill when she began travelling to Canterbury.

Joan died at the age of twenty-seven at Havering in Essex on March 4, 1238 in the arms of her brothers King Henry and Richard of Cornwall.

According to Matthew Paris ‘her death was grievous, however she merited less mourning, because she refused to return [to Scotland] although often summoned back by her husband’. And even in death Joan elected to stay in England. her will requested that she be buried at the Cistercian nunnery of Tarrant in Dorset.

Henry would be generous in giving alms to the nunnery after his sister’s death suggesting he loved her dearly. He arranged for a tomb to be erected over her body and later had a marble effigy carved and placed beside the tomb. The last mention of the church where she was buried is from the Reformation and there is no trace of this tomb or the church left.

Talking of her wedding day, the Chronicle of Lanercost had described Joan as ‘a girl still of a young age, but when she was an adult of comely beauty.’ After her death, Alexander would marry Marie de Coucy who finally provided him with a male heir.

#joan of england#queen of scotland#princess of england#the plantagenets#house of plantagenet#plantagenet dynasty#medieval queens#kings and queens#history#medieval history#english history#scottish history#historical figure#Joan is probably one of the first plantagenet figures I fell in love with as a child#i have always seen her story as a tragic one#the fact that she died in both her brothers arms' is heartbreaking#historyedit#plantagenetedit#queenedit#I might to more depending on how this one goes#queens#royalty#english royalty#scottish queens#13th century

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

isabellacapets said: can you imagine how tabloid magazines would have been like in the middle ages?

Have you ever read the Chronicle of Lanercost

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

October 17th saw 1346 Battle of Neville's Cross.

This was another catastrophic battle for Scotland, it was triggered by the French asking us to invoke terms The Auld Alliance after the English won The Battle of Crecy in August 1346.

After the usual rampaging through Northumberland for a few weeks, the 12,000 strong Scottish army arrived outside the gates of Durham on 16th October 1346.

Waiting for their payment of £1,000 in protection money to arrive, the Scots were blissfully unaware that an English force comprising some 7,000 men raised from the northern counties of England had been quickly mobilised by William Zouche, the Archbishop of York.

The Scots only discovered the presence of the English army on the morning of 17th October, when they stumbled upon them in the morning mist.

With the English positioned on the better ground, the invaders found themselves disadvantaged by the uneven ground and their formations fell apart as they tried to advance.

Sensing defeat and now out manoeuvred, many of the Scottish nobles, as per usual, fled the field abandoning King David II and his bodyguard to face the enemy alone.

David II initially managed to escape. However, legend records that while he was hiding under a bridge over the nearby River Browney, his reflection was spotted in the water by a English soldiers out searching for him. David was then taken prisoner by John de Coupland. King David was imprisoned at Odiham Castle in Hampshire from 1346 to 1357. David was only 17 at the time, it would 11 years before he was to see Scotland again.

It's worth noting that Edward III did more than his fair share of meddling in Scottish affairs, like his grandfather he used the much maligned Balliol family during what is called The Second war of Scottish Independence.

The battle was disastrous for the Scots, as not only was their king captured and imprisoned, but in the year that followed the English drove home their advantage and occupied virtually all of southern Scotland.

Eventually our monarch was released in return for a ransom of 100,000 marks as part of the Treaty of Berwick.

The depiction is from the Froissart Chronicles written in the 14th century by Jean Froissart.

You can find out more about this battle at the link below, taken largely from the English Lanercost chronicles. https://www.medievalists.net/.../the-battle-of-nevilles.../

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th February 1314 saw James Douglas retake Roxburgh Castle and raze it to the ground, a major breakthrough in the Wars of Scottish Independence.

The Black Douglas, as he was known, to the English, and sixty men approached the castle under cover of darkness draped in black cloaks to fool the defenders into thinking they were simply cattle. They scaled the walls and surprised the garrison climbing the castle walls using hooked scaling ladders after taking the Castle it was razed to the ground

It is well known that Robert Bruce's policy was to " slight" a castle whenever he captured one, as his small field army was never sufficient to detach garrisons for these fortresses, in order to prevent their re-occupation. As the Chronicle of Lanercost states, in describing how the Scots dealt with Roxburgh Castle,

"they razed to the ground the whole of that beautiful castle, just as they did other castles which they succeeded in taking, lest the English should ever hereafter be able to lord it over the land through holding the castles."

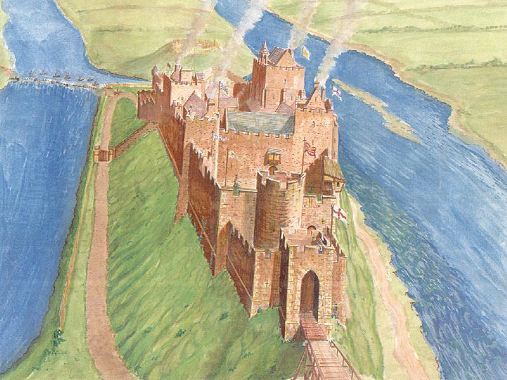

Little remains of the castle as you can see from the photo but the second pic is an interpretation of how it would have looked by Andrew Spratt.

Find more about the castle on the excellent Maybole page here https://www.maybole.org/history/castles/roxburgh.htm

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 8th January 1313 the forces of Robert Bruce seized Perth from the English garrison.

This victory was significant as it brought all of Scotland north of the Forth under Bruce's control. However, it was also a source of embarrassment for later Scottish writers seeking to cast King Robert in a positive light, as the events of 8th January seem to have degenerated into a bloodbath.

By 1313, the tide of the war had very much turned in Bruce's favour. He had defeated his main Scottish opponents at the Battles of Inverurie and the Pass of Brander in 1309, survived an English invasion of Scotland in 1310-11, and even begun raiding into northern England. 1312 had ended on something of a sour note when the barking of a dog had thwarted a Scottish attempt to capture Berwick by surprise, but undeterred Bruce marched his men north to lay siege to Perth.

Perth was no easy target - its castle had not been rebuilt since a flood a century earlier but it was still protected by a wall and a water-filled ditch. It seems that Bruce was counting on the English being unprepared for the Scots to keep up the military pressure on them during the frigid Scottish winter (normally, the campaigning season would last from spring to autumn at the most, as I have pointed out in previous posts, I call it “the battle season”)

Both the contemporary Lanercost Chronicler and the late Scottish writer John Barbour blame the fall of Perth at least in part on the negligence of the garrison. On the night of 7th January, under cover of darkness, the Scots surged across the ditch in force and threw ladders against the wall, pouring into the town and overwhelming the unprepared defenders. By the morning of the 8th, Perth belonged to Bruce.

The aftermath of the capture of Perth is a source of some disagreement among contemporary and near contemporary historians, possibly because many of those writers felt uncomfortable with the facts as they saw them. The earliest surviving account comes from the Lanercost Chronicle, which claims that those in the town 'who were of the Scottish nation' were put to death, although the Englishmen there were allowed to return home.

The earliest surviving Scottish account of the incident - written by John Fordun in the 1360s - states that 'the disloyal people, both Scots and English, were taken, dragged and slain with the sword', although he attempts to mitigate this by emphasising that their disloyalty is what earned them this fate and adding that the king spared anyone who begged for mercy.

Writing about a decade after Fordun, the Scottish poet John Barbour - who was writing for Robert II, addressed this aspect of the capture of Perth simply by denying it, claiming that Bruce had specifically ordered his men not to kill anyone unless they refused to surrender without a fight. Despite Barbour's protestations, it would seem that the capture of Perth was accompanied by considerable bloodshed. If we are being generous to Bruce - and most historians who have written about the fall of Perth have been inclined to be just that - any executions after the town's capture can be understood as a very emphatic way of discouraging disloyalty among his subjects in other towns around the kingdom, a common enough tactic in medieval warfare, these were brutal times.

King Robert could now claim to control all of Scotland north of the Forth. Further offensives later in the year secured Bruce's control of the south-west, so that by the end of the year only Lothian and the Borders remained in English hands. By late spring The Bruce controlled almost all of Scotland .

Stirling castle was still under the control of English forces but was under siege from the Scots led by Edward Bruce. Bruce and the English commander, Sir Philippe de Mowbray, came to an agreement that if English forces had not reached the castle by midsummer 1314, Mowbray would surrender the castle to the Scots. Bruce even let Mowbray leave the castle to inform the English king of the agreement, the scene was set for the Battle of Bannockburn.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

30th November 1335 saw the Battle of Culblean.

Another little known battle , this ties in with the Balliols, this time Edward and is seen as the turning point in the Second War of Independence.

By November 1335, with the help of English troops Balliol held all but 4 Scottish castles, David de Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl, loyal to Balliol, was laying siege to one of them, Kildrummy Castle in Aberdeenshire, which controlled the North East. Among them was the Bruce’s sister, Christian, and wife of Sir Andrew, a constant thorn in Balliol’s side during the Second Wars of Independence, he was also Regent to King David.

Murrray raised an army of about 4,000 to lift the siege, including the Earl of March and Sir William de Douglas. On 29th November the army camped at “Hall of Logy Rothwayne” on the north east shore of Loch Davan. On learning of their approach Atholl abandoned the siege and camped at the east end of Culblean, perhaps aiming for his land of Atholl, to the south.

The battle was described by Wyntoun’s Chronicle. John of the Craig, defender of Kildrummy told Murray of an approach to outflank Atholl, and splitting his forces, on St Andrew’s Day , de Douglas feinted to the front of Atholls army, about 3,000 strong, and de Moray hit them from the flank. Surprised and overwhelmed the pro English army was defeated. According to Boece’s account Atholl himself was killed by Alexander Gordon, the successor to the Lordship of Strathbogie forfeited by Atholl. Some of the survivors took refuge in the nearby island castle of Loch Kinord, but were forced to surrender the following day.

Compared with the other great battles of the Wars of Independence, Culblean was a relatively small affair, and is now largely forgotten. Nevertheless, its size was greatly outweighed by its importance on the road to Scottish national recovery. The Scottish academic and Historian Dr Douglas Simpson passed what might be said to be the final verdict on the battle when he wrote; Culblean was the turning point in the second war of Scottish Independence, and therefore an event of great national importance. Small as it was it effectively nullified the effects of Edward’s summer invasion, ending forever Balliol’s hope of gaining the Scottish throne. Its effects were almost immediately felt. Edward Balliol spent the winter of 1335-6, so says the Lanercost Chronicle; …with his people at Elande, in England, because he does not yet possess in Scotland any castle or town where he could dwell in safety

A monolith 13ft high was erected 16 September 1956, by the Deeside Field Club, to commemorate the battle, just off the Tarland-Burn o’ Vat road near the hill where the battle was fought. It reads

“Erected by the Deesside Field Club in 1956 to commemorate the Battle of Culblean fought on St. Andrew’s day, 30 November 1335 between the forces of Sir Andrew de Moray, Warden of Scotland, and David, Earl of Atholl, in which the former was victorious. The battle marked the turning point of the second Scottish War of Independence.”

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

On October 14th 1322 a Scottish army led by King Robert I defeated Edward II of England at the Battle of Old Byland.

Many people are unaware that The Bannockburn did not end The Wars of Scottish Independence, they were to run intermittently for years to come. Seen as possibly the most important of those encounters was the Battle of Old Byland in Yorkshire on this day in 1322 when the Scots once again faced their English foes – but this time on English soil.

Robert the Bruce now took his army of 20,000 mosstroopers ( marauders who operated in the mosses, or bogs, of the border between the two countries)and clansmen through the west marches and laid waste to the areas round Carlisle, Lancaster and Preston before marching across the Pennines through Swaledale and Wensleydale where he could and should have been ambushed and stopped in his tracks by any competent defender of the easily defensible passes. Bruce joined forces with The Good Sir James Douglas at Northallerton and received the news that Edward II was staying at Rievaulx Abbey, about 20 miles away. Bruce conferred with his generals, Douglas, Sir Walter Stewart, and Sir Thomas Randolph and discussed the possibility of capturing King Edward and bringing this long drawn out war to an end.