#Margaret of Scotland Queen of Norway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

January 28th 1290 saw the death of Devorgilla, Lady of Galloway.

One with differing dates, but the majority of sources give January 28th, the name Dervorguilla or Dervorgilla was a Latinisation of the Gaelic Dearbhfhorghaill (alternative spellings, Derborgaill or Dearbhorghil).

Through her mother, Devorgilla was descended from King David I of Scotland. Her grandmother Maud was a member of the family of the powerful Earl of Chester while her aunt Isobel of Huntingdon was grandmother to Robert the Bruce.

The Lanercost states that Dervorguilla was the “widow of Lord John de Balliol” and that she “was a woman largely endowed with money and lands, both in England and in Scotland.” It also adds in her favour that “she had a much richer endowment in the nobility of her heart, being daughter and heiress of the magnificent Alan, the sometime Lord of Galloway.” Regarding her death, it states that “She passed from the world, full of years, at Castle Barnard, and was buried at Duquer, in Galloway, a Monastery of Cistercians, which she herself built and endowed.” Looks like ‘endowed’ was a well used term in those days; at least in the Lanercost.

Arguably the most famous fact about her, in Scotland at least, is that she was the mother of our erstwhile King John, it was through her that his legitimate claim to the Scottish crown came about, she was a great-great-granddaughter of King David I. Had she lived a wee whiles her lineage would have thrown up the possibility of her being named Queen of Scotland after the death of Margaret Maid of Norway in September 1290, this would have precluded that nasty Edward I interfering with our affairs, Queen Dervorguilla, how does that sound? This alternative timeline may have been the start of a Balliol dynasty, no Bruce’s or Stewarts such is the ifs and buts of history.

While a lot of marriages were arranged to form alliances and were loveless, that is not the case with that is certainly not the case with Lady Dervorguilla and John Balliol snr, on the death of her husband, in 1268, Dervorguilla had his heart embalmed and kept in a casket of ivory bound with silver. The casket travelled with her for the rest of her life.

Poetry has been written of the love shared between John Balliol and Dervorguilla of Galloway, the Lady also founded New Abbey in Dumfries & Galloway in honour of her husband, after her own death the Monks in the Abbey started calling it Dulce Cor, Latin for Sweet Heart, and so it became known as Sweetheart Abbey.

She was also the co-founder, with her husband of Balliol College, Oxford in 1263, even after John Balliol’s death Lady Dervorguilla continued to support it, securing its permanent endowment in 1282, as well as formal statutes, a seal, and a house to study in. It’s a shame that College did not allow women students until 1979!.

If you have ever visited Dumfries you will have no maybe crossed over the river Nth on Dervorguilla Bridge, built in 1426 and named in her honour.

She was buried in front of the high altar at Sweetheart Abbey. A stone slab in the floor marks the supposed site of her burial, the actually place being lost due to the mindless destruction of he Scottish Reformation, their lost graves lie amongst the ruins, which is described as a “shrine to human and divine love”.

An effigy found by archaeologists can be seen at the Abbey, sadly the head is missing, but it is thought to be the Lady and in 2017 it was named number 10 by VisitScotland in their 25 Objects That Shaped Scotland’s History. It can be seen in the second photo.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Lol, she has always had a soft spot for the English as far back as Fearless era. Love Story- English regency theme, English actors played love interests in Mine & Style music videos, UK singer ES collaboration, and Wordsworth Windermere lakes district inspiration. Not sure on other eras.

reddit.com/r/TaylorSwift/comments/vk1wx6/miss_americana_taylor_swifts_american_heritage/

A way with words & diplomacy runs in the family bloodlines. One of the descendants came up with historical slogan “No taxation without representation.” Also settled peacefully in Martha’s Vineyard among the native Indians (pre-USA).

Recent deep dive heraldscotland.com/life_style/arts_ents/23623229.taylor-swift-edinburgh-star-real-queen-scotland/

“…the 33-year-old can trace her roots back to Scottish King William the Lion.

The monarch, of the House of Dunkeld, ruled from 1165 to 1214, and while records are patchy - and, let's face it, not the most reliable given most people couldn't read or write - it appears he could be 26th great-grandfather of the pop superstar.

The House of Dunkeld ended in 1290 when Margaret Maid of Norway died aged seven in Orkney.

She was the last legitimate descendent of William the Lion but, as she was never crowned, historians are split on whether she can be considered Queen of Scots.”

Her dna trying to lead her home lol

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where Ariel lives

Where does Ariel the little mermaid live? I found this question particularly exciting to clarify, especially in relation to the live action film in which Ariel is played by an Afro-American woman. Here I give you the history of my research. ~*~ The sea kingdom where Ariel lives is called Atlantica. So it stands to reason that this kingdom is somehow in the Atlantic.

North America, South America, Europe and Africa border the Atlantic Ocean. In the area of Europe it is the North Atlantic and in the area of Africa it is the South Atlantic. ~ Then King Triton's name caught my eye. Triton is the son of the Greek god of the sea, Poseidon. He also spawned the Tritons, which are nothing but mermaids and mermen. His palace was in present-day Turnesia. However, Triton had no daughters. At least I couldn't find anything about it. So I guessed, only the name was adopted. But that's why I found it interesting to find out where his daughters' names came from. Name: Ariel, Arielle Origin: Hebrew, France Meaning: The Lion of King, The one born in the water Name: Aquata Origin: Greece Meaning: Water Name: Attina (Athena) Origin: Greece Meaning: Wise Name: Alana Origin: Latin, Irish, (may) german Meaning: Precious, Awakening Name: Adella Origin: German Meaning: Noble Name: Arista Origin: Greece Meaning: The best Name: Andrina Origin: Greece Meaning: Manly, Brave Ariel is a male name, Arielle is the female version. Both are hebrew origins and means lion of god. But in France Arielle means water born. Attina is another variant of Athena, the greek goddess of wisdom. In the Live-Action Movie Arielles the siblings are called: Caspia, Indira, Perla, Karina, Mala und Tamika ~ Speaking of names. Where is Prince Eric from? Could he be Eric of Pomerania? He ruled over Denmark, Sweden and Norway. In 1389, Bogislaw was brought to Denmark to be raised by Queen Margaret. His name was changed to the more Nordic-sounding Erik. Source Because the original story of Arielle, written by Hans Christian Anderson, takes place in Denmark, cartoon Erik's empire seems also be Denmark. ~ Then I took on Fabius and Sebastian. Fabius is a surgeonfish that is also found in the Atlantic. This confirms my thesis that Atlantica must be somewhere in the Atlantic. With Sebastian, you know exactly what type of crab he is supposed to be. Because he is red, possible candidates would be the Christmas Island crab, a land crab from Australia, and the red mangrove crab from Thailand. But they don't reside in the Atlantic. That's why I assume Sebastian is a pure invention. Teach me otherwise. But where does the seagull Scuttle actually fly? Scuttle is a lesser black-backed gull. At least that would make the most sense. Lesser black-backed gulls live on the Atlantic coasts of Europe and also winter in North America and West Africa. Source ~ Finally, let's talk about Ariel's red hair. I was also very interested in them: Red hair is most commonly found at the northern and western fringes of Europe;[4] it is centred around populations in the British Isles and is particularly associated with the Celtic nations.[4] Ireland has the highest number of red-haired people per capita in the world, with the percentage of those with red hair at around 10%.[5]

Great Britain also has a high percentage of people with red hair. In Scotland, around 6% of the population has red hair, with the highest concentration of red head carriers in the world found in Edinburgh, making it the red head capital of the world.[6][7] In 1907, the largest ever study of hair colour in Scotland, which analysed over 500,000 people, found the percentage of Scots with red hair to be 5.3%.[8] A 1956 study of hair colour among British Army recruits also found high levels of red hair in Wales and in the Scottish border counties of England.[fn 1][9] The Berber populations of Morocco[23] and northern Algeria have occasional redheads. Red hair frequency is especially significant among the Riffians from Morocco and Kabyles from Algeria,[24][25][26] respectively. Source While Europe, especially Ireland, has the most redhairs, they are rarely seen in Africa. And Ireland is pretty close to Denmark. Arielle is full of European influences. Starting with the names of the sea creatures. Prince Erik is sure from Denmark. His name is also Nordic. Because of this I think Atlantica is located in the Atlantic Ocean between Ireland and Denmark nearby island. That would make the most sense. Of course, the conditions are there to move the setting from Europe to Africa. But how far will Ariel swim to get to Erik? At least a fair bit further than the original European Ariel.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay so William the conqueror got the throne in the battle of Hastings which actually happened in Battle so Battle of Battle tho it’s called Battle because of the battle but anyway he became king and when he died, his oldest son, Robert, didn’t become king of England he became Duke of Normandy and the second son, William I, became king of England. When William died Robert was supposed to become king but the third son, Henry, made some bogus claim about how he was born while their father was king of England, so he was more royal than them. Anyway Henry I’s only legitimate children were a son, William Adelin, and a daughter, Empress Matilda. William died in a shipwreck and Henry decided to be radical and make his daughter his heir. That didn’t go too well, a nephew, Stephen of Blois, claimed the throne while Matilda wasn’t there. This led to the Anarchy which ended with Stephen being king but Matilda’s son, another Henry, being the heir. And then I think it was Henry’s son next (I don’t really remember and this is just what I remember) but whoever he was his name was Richard and he spent like none of his time as king in England. He was Crusading for most of this. Anyway Richard was followed by his brother John, of Robin Hood fame, who lost all the Crown Jewels and was almost replaced by a French prince who the barons (?) summoned to replace him. That didn’t really work out. Then John’s son Henry who I literally don’t know anything about but anyway. His son was named after the king way back before William the Conqueror—Edward. Edward I was known as the Hammer of the Scots bc England and Scotland were at war I think? Idk. I think it was Edward who took Wales bc his son was born in Caernarfon or however you spell it. Edward II was supposed to marry Margaret, maid of Norway, but she died before becoming queen of Scotland, so you know. I lose track of what happens after that.

If I got anything wrong someone tell me

!! WHOA?? Thank you for this information on the monarchy of medieval england. I genuinely love visiting old sites around the country when we go away like castles, rivers yknow. so its good to put all the pieces together :)

#why do we learn about american politics in history and not. this#shocked by how quickly the ask arrived LOL#anyway#message in a bottle

1 note

·

View note

Note

Okay so William the conqueror got the throne in the battle of Hastings which actually happened in Battle so Battle of Battle tho it’s called Battle because of the battle but anyway he became king and when he died, his oldest son, Robert, didn’t become king of England he became Duke of Normandy and the second son, William I, became king of England. When William died Robert was supposed to become king but the third son, Henry, made some bogus claim about how he was born while their father was king of England, so he was more royal than them. Anyway Henry I’s only legitimate children were a son, William Adelin, and a daughter, Empress Matilda. William died in a shipwreck and Henry decided to be radical and make his daughter his heir. That didn’t go too well, a nephew, Stephen of Blois, claimed the throne while Matilda wasn’t there. This led to the Anarchy which ended with Stephen being king but Matilda’s son, another Henry, being the heir. And then I think it was Henry’s son next (I don’t really remember and this is just what I remember) but whoever he was his name was Richard and he spent like none of his time as king in England. He was Crusading for most of this. Anyway Richard was followed by his brother John, of Robin Hood fame, who lost all the Crown Jewels and was almost replaced by a French prince who the barons (?) summoned to replace him. That didn’t really work out. Then John’s son Henry who I literally don’t know anything about but anyway. His son was named after the king way back before William the Conqueror—Edward. Edward I was known as the Hammer of the Scots bc England and Scotland were at war I think? Idk. I think it was Edward who took Wales bc his son was born in Caernarfon or however you spell it. Edward II was supposed to marry Margaret, maid of Norway, but she died before becoming queen of Scotland, so you know. I lose track of what happens after that.

If I got anything wrong someone tell me

I honestly didn't know anything about this before now and its interesting as hell. Keep Asking if you want :)

0 notes

Note

Okay so William the conqueror got the throne in the battle of Hastings which actually happened in Battle so Battle of Battle tho it’s called Battle because of the battle but anyway he became king and when he died, his oldest son, Robert, didn’t become king of England he became Duke of Normandy and the second son, William I, became king of England. When William died Robert was supposed to become king but the third son, Henry, made some bogus claim about how he was born while their father was king of England, so he was more royal than them. Anyway Henry I’s only legitimate children were a son, William Adelin, and a daughter, Empress Matilda. William died in a shipwreck and Henry decided to be radical and make his daughter his heir. That didn’t go too well, a nephew, Stephen of Blois, claimed the throne while Matilda wasn’t there. This led to the Anarchy which ended with Stephen being king but Matilda’s son, another Henry, being the heir. And then I think it was Henry’s son next (I don’t really remember and this is just what I remember) but whoever he was his name was Richard and he spent like none of his time as king in England. He was Crusading for most of this. Anyway Richard was followed by his brother John, of Robin Hood fame, who lost all the Crown Jewels and was almost replaced by a French prince who the barons (?) summoned to replace him. That didn’t really work out. Then John’s son Henry who I literally don’t know anything about but anyway. His son was named after the king way back before William the Conqueror—Edward. Edward I was known as the Hammer of the Scots bc England and Scotland were at war I think? Idk. I think it was Edward who took Wales bc his son was born in Caernarfon or however you spell it. Edward II was supposed to marry Margaret, maid of Norway, but she died before becoming queen of Scotland, so you know. I lose track of what happens after that.

If I got anything wrong someone tell me

Empress is a great word

Also dw I would not know if ur right or not with any of this bc most of what ik abt this stuff is related to Irish history

0 notes

Text

Margaret, Maid of Norway

the best queen

Born: 9 April 1283

Died: 26 September 1290

Margaret, Maid of Norway was the only child of Margaret of Scotland, the daughter of Alexander III and Eric II of Norway. Her mother died in childbirth. After her uncle, another Alexander, died in 1284, Margaret was the only surviving descendant Alexander had left. He had the earls, barons, and clan chiefs of Scotland come to Scone to swear to recognize Margaret as his heir presumptive. In March 1286, Alexander was found dead with a broken neck. He had fallen from his horse on his way to see his wife, who was pregnant. However, the baby was stillborn and Margaret’s accession seemed assured.

In 1290, Margaret set sail from Norway. She never arrived. She died from motion sickness or food poisoning at Orkney, then a part of Norway.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BORN ON THIS DAY:

Margaret of Denmark (23 June 1456 – 14 July 1486) was Queen of Scotland from 1469 to 1486 by marriage to King James III.

She was the daughter of Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and Dorothea of Brandenburg.

0 notes

Text

Last is Margaret, the Maid of Norway:

Who appropriately intersects with one of the cases where I shall pick up, with the Plantagenets. She represented the last bid of the first Scottish dynasty to hold onto the throne, which ultimately misfired because she died at the tender young age of eight. The result of this was the very inheritance crisis that permitted Edward I to have his opportunity to seek to first place a puppet king in Scotland and then to invade and outright conquer it.

For this, and for all else that would follow, he would open the opportunities to another Queen Matilda, as he was a very successful and brutish warlord and his son Edward II was.....not.

That said next up will be the history of the Mongol Empire as a part of women's history, both the unpleasant bits like how Genghis Khan has 16 million descendants these days, and the Khatuns who ran the Empire. The Mongols for much of Asia and parts of Europe are the watershed between eras, for Western Europe it was the Avignon Schism and the Hundred Years' War started by Edward I's grandson.

#lightdancer comments on history#women's history month#europe and women's history#margaret the maid of norway

1 note

·

View note

Text

19th March 1286: “A Strong Wind Will Be Heard in Scotland”

(Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

On 19th March 1286, a body was discovered on a Fife beach, not far from the royal burgh of Kinghorn. The corpse was that of a 44-year-old man, and the cause of death was later diversely reported as either a broken neck or some other severe injury consistent with a fall from a horse at some point during the previous night. It is not known exactly when this body was found, nor do we know who discovered it. But we do know that the dead man was soon identified, with much dismay, as the King of Scots himself, Alexander III.

The late king had no surviving children, only a young widow who was not yet known to be pregnant, and an infant granddaughter in the kingdom of Norway. Despite this, Alexander III’s untimely death did not cause any immediate civil strife, although it did set in motion a chain of events which eventually led to the Scottish Wars of Independence. This conflict would forever alter the relationship between the kingdoms of Scotland and England, as well as the wider course of European history.

Although Alexander III was a moderately successful monarch, he had been unfortunate over the last ten years. His first wife, Margaret of England, had died in 1275 and Alexander initially showed no immediate interest in remarriage. At first the succession seemed secure: Margaret had left behind two sons and a daughter. However the death of the couple’s younger son David c.1281, may have prompted the king’s decision to arrange the marriages of his two surviving children over the next few years. In the summer of 1281, the twenty-year-old Princess Margaret set sail for Bergen, where she was to marry King Eirik II of Norway. Her brother Alexander, the eighteen-year-old heir to the throne, married the Count of Flanders’ daughter in November 1282. Neither marriage lasted long. The queen of Norway died in spring 1283, possibly during childbirth, while her younger brother succumbed to illness in January 1284. Within a few years, a series of unforeseen tragedies had destroyed Alexander III’s family and hopes, and the outlook for the kingdom seemed equally bleak...

All was not lost however. The king was in good health and believed he could count on the support of the realm’s leading men. Steps were swiftly taken to ensure their compliance with his plans for the succession. On 5th February 1284, a few weeks after Prince Alexander’s death, an impressive number of Scottish nobles* set their seals to an agreement at Scone. In the event of the king of Scotland’s death without any surviving legitimate children, they obliged themselves and their heirs to accept as monarch the heir at law. This was currently a baby named Margaret, the only surviving child of Alexander III’s daughter the queen of Norway.

(Drawing based on a seal belonging to Yolande of Dreux, Alexander III’s second queen. She later became Countess of Montfort and, by marriage, Duchess of Brittany. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Although the bishops of Scotland were to censure anyone who broke this oath, the prospect of the crown being inherited by an infant girl on the other side of the North Sea was obviously not ideal. Her grandfather struck an optimistic note in a letter to his brother-in-law Edward I of England, writing that in spite of his recent “intolerable” trials, “the child of his dearest daughter” still lived and hoping that “much good may yet be in store”. But the king would not leave everything up to chance and in October 1285, at the age of 43, he married the French noblewoman Yolande of Dreux. As the year drew to a close, Alexander might have hoped that his misfortunes were behind him. He still had his kingdom and his health, and now, with a new queen, there was every chance that he could father another son.

In fact, the king had less than six months to live. The exact circumstances of Alexander’s death are shrouded in mystery, although most sources agree on the fundamental details. Only the Chronicle of Lanercost gives a detailed account, although much cannot be corroborated, and its author had a habit of providing moral explanations for historical events. He was convinced that the calamities which befell the Scottish royal house in the 1280s were punishment for Alexander III’s personal sins. The chronicler never explicitly names these sins, but he does hint at a conflict between the king and the monks of Durham (allowing Alexander’s death to be attributed to a vengeful St Cuthbert). The chronicler also included salacious stories of Alexander’s private life, claiming:

“he used never to forbear on account of season or storm, nor for perils of flood or rocky cliffs, but would visit, not too creditably, matrons and nuns, virgins and widows, by day or by night as the fancy seized him, sometimes in disguise, often accompanied by a single follower.”

Although this does seem to back up the king’s habit of making reckless journeys, alone and in bad weather, the chronicle’s biases are nonetheless fairly obvious. On the other hand, the man who probably compiled the chronicle up to the year 1297 does appear to have had many contacts in Scotland. These included the confessors of the late Queen Margaret and her son Prince Alexander, as well as the latter’s tutor, the clergy of Haddington and Berwick, and the earl of Dunbar. It is unclear how he acquired information about Alexander III’s death, but the chronicle’s narrative is at least plausible and correct in its essentials. Although some of the anecdotes are a little too detailed and didactic to be entirely truthful, the narrative provides some interesting insights into contemporary behaviour, such as the way medieval Scots felt entitled to address their kings. In the absence of alternative narratives, and without necessarily subscribing to the chronicler’s moral views, it is therefore perhaps worth following Lanercost to begin with, supplementing this with additional information where possible.

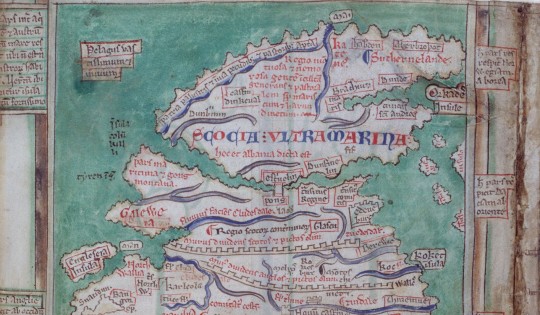

(The northern half of a map of Britain, drawn by the thirteenth century English chronicler Matthew Paris. Matthew Paris was based in the south of England and was not overly familiar with Scottish geography, but his depiction of Scotland as split over two islands and joined only at the bridge of Stirling, is nonetheless enlightening. The map is now in the public domain and has been made available by the British Libary (x))

On the evening of 18th March 1286, Alexander III is reported to have been in good spirits. This was in spite of the weather, which the author of the Chronicle of Lanercost described as being so foul, “that to me and most men, it seemed disagreeable to expose one’s face to the north wind, rain and snow”. The king of Scots was then dining at Edinburgh, attended by many of his nobles, who were preparing a response to the king of England’s ambassadors regarding the aged prisoner Thomas of Galloway. However when the court had finished dinner King Alexander was not at all anxious to retire early. Instead, not in the least deterred by the wind and rain lashing the windows, he announced his intention of spending the night with his new wife. Since Queen Yolande was then staying at Kinghorn in Fife, travelling there from Edinburgh would not only involve riding over twenty miles in the dark, but would also mean crossing the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth. Unsurprisingly, the king’s councillors tried to dissuade him. However Alexander was determined, and eventually he set off with only a few attendants, leaving his courtiers wringing their hands behind him.

The first part of the journey passed without incident and soon the king and his companions arrived at the Queen’s Ferry, by the shores of the Forth. This popular crossing point was named after Alexander’s famous ancestress St Margaret, who had established accommodation and transport for pilgrims there two hundred years earlier. But when the king himself sought passage, the ferryman pointed out that it would be very dangerous to attempt the crossing in such conditions. Alexander, undeterred, asked him if he was scared, to which the ferryman is said to have stoutly replied, “By no means, it would be a great honour to share the fate of your father’s son.” So the king and his attendants boarded the ferry and, notwithstanding the storm, the boat soon reached the shores of Fife in safety. As the king and his squires rode away from the ferry port, intending to complete the last eleven or so miles of their journey that night, they passed through the royal burgh of Inverkeithing. There, despite the evening gloom, the king’s voice was recognised by the manager of his saltpans, who was also one of the baillies of the town.** The burgess called out to the king and reprimanded him for his habit of riding abroad at night, inviting Alexander to stay with him until morning. But, laughing, Alexander dismissed his concerns and, asking only for some local serfs to act as guides, he rode off into the night.

(South Queensferry, as drawn by the eighteenth century artist John Clerk and made available for public use by the National Galleries of Scotland. Obviously the Queen’s Ferry changed a lot between the 1280s and the 1700s, but at least during this period the ferry was still the main mode of transportation across the Forth.)

By now darkness had set in and, despite the local knowledge of their guides, it was not long before every member of the king’s party became completely lost. Although they had become separated, the king’s squires eventually found the road again. However at some point they must have realised that they had a new problem: the king was nowhere to be found.

In the early fifteenth century, local tradition held that Alexander was at least heading in the right direction when he became separated from his companions. Although he too had lost sight of the main road, the king followed the shoreline, his horse carrying him swiftly over the sands towards Kinghorn. It was there, only a couple of miles from his destination, that the king’s luck finally ran out. Since there were no known witnesses to Alexander III’s death, it is unlikely that we will ever know for certain what happened that night. However most sources agree that the king’s horse probably stumbled and threw its rider. Alexander tumbled to the ground and snapped his neck and, at a stroke, the dynasty which had ruled Scotland for over two hundred years came to an end.

It is not known precisely how long the king’s body lay on the beach, alone under the moon while the waves crashed on the shore and confusion reigned among his squires and guides. However his corpse was discovered the next day and was swiftly conveyed to nearby Dunfermline. Ten days later, on 29th March 1286, the kingdom’s ruling elite gathered to see the last King Alexander buried near the high altar of the abbey kirk, in the company of his ancestors. Near the spot where the king’s body was allegedly found, a stone cross was later erected beside the road, which could still be seen by travellers over a hundred years later. The modern belief that Alexander III died when either he or his horse fell from a cliff*** (a tradition which is not supported by any mediaeval sources so far as I am aware) may stem from the position of this old cross, which possibly occupied the same spot as that of the Victorian Alexander III monument. This monument can now be seen at the side of the modern A921 road between Burntisland and Kinghorn, a permanent reminder of the role this seemingly nondescript location once played in the history of Scotland.

(The Alexander III monument near Kinghorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons- the photo was taken by Kim Traynor who has kindly made the image available for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The impact of Alexander’s death on a small mediaeval kingdom like Scotland, conditioned to look to its monarch for leadership, must have been great. Even the Lanercost chronicler admitted that the general populace was observed “bewailing his sudden death as deeply as the desolation of the realm.” However it is important not to exaggerate the scale of the crisis. Popular views of Alexander III’s death are inescapably informed by the accounts of fourteenth and fifteenth century writers, who depicted it as the root of all of Scotland’s later ills.

Writing in the aftermath of a century dominated by war, plague, famine, and climate change, it is perhaps unsurprising that many late mediaeval chroniclers looked back on Alexander III’s reign as comparatively peaceful. As the author of the fourteenth century “Gesta Annalia II” explained, “How worthy of tears and how hurtful his death was to the kingdom of Scotland is plainly shown forth by the evils of after times.” Meanwhile, in his “Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland” completed c.1420, Andrew Wyntoun portrayed Alexander’s reign as a Golden Age of peace and justice (when, just as importantly, oats only cost fourpence a boll). He incorporated an old song into his chronicle, perhaps written in the years following the king’s accident, which neatly encapsulates later views of the event and its impact:

“Quhen Alysandyr oure Kyng wes dede

That Scotland led in luẅe and lé,

Away wes sons off ale and brede,

Off wyne and wax, off gamyn and glé:

Oure gold wes changyd in to lede.

Cryste borne in to Vyrgynyté,

Succoure Scotland and remede,

That stad [is in] perplexyté.”

Wyntoun’s younger contemporary Walter Bower, author of the “Scotichronicon”, also lamented Alexander’s premature death and even rolled out a legend about Scotland’s famous seer, Thomas the Rhymer, to reinforce his point. On 18th March 1286, he claimed, the earl of Dunbar “half-jesting” asked the Rhymer for the next day’s weather forecast. True Thomas answered gloomily:

“Alas for tomorrow, a day of calamity and misery! Because before the stroke of twelve a strong wind will be heard in Scotland, the like of which has not been known since long ago. Indeed its blast will dumbfound the nations and render senseless those who hear it, it will humble what is lofty and raze what is unbending to the ground.”

The next morning came and went without any gales, so the earl decided that Thomas had gone mad- until a messenger arrived at precisely midday with news of the king’s death. Although Bower may have been attempting to bolster Thomas of Erceldoune’s reputation as a prophet (in response to English propagandic use of Merlin’s prophecies), the anecdote reveals the significance he attached to Alexander III’s death. Similarly for John Barbour, author of the fourteenth century romance “The Bruce”, there was no doubt that the story of his hero’s story began, “Quhen Alexander the king was deid / That Scotland haid to steyr and leid.” Following this, Barbour skips ahead to the selection of John Balliol as king, dismissing the six years in between as a time when the country lay “desolate”. In this way later chroniclers created the impression of an Alexandrian ‘Golden Age’ and that Scotland almost immediately descended into chaos after his death. Though understandable, these late mediaeval interpretations have traditionally hampered analysis of Alexander’s reign and the events of the decade following his death, despite the best efforts of modern historians.

(The coronation of the young Alexander III at Scone, as depicted in a manuscript version of the fifteenth century “Scotichronicon”, compiled by the Abbot of Incholm, Walter Bower. Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In reality, while the king’s death was undoubtedly a deep blow, the Scottish political community rallied in the immediate aftermath. In April 1286, parliament assembled at Scone and promised to keep the peace on behalf of the rightful heir to the kingdom. Six ‘Guardians’ were to govern in the meantime- two bishops (William Fraser of St Andrews and Robert Wishart of Glasgow), two earls (Alexander Comyn, earl of Buchan and Duncan, earl of Fife), and two barons (John Comyn of Badenoch and James the Steward). Despite the oaths sworn to Margaret of Norway two years earlier, there may have been some doubt as to who the “rightful heir” actually was. Certain sources claim that Alexander III’s widow Yolande of Dreux was pregnant and the political community waited anxiously for several months before the queen gave birth in November 1286. However no male heir materialised**** and by the end of the year it seems to have been generally acknowledged that the three-year-old Maid of Norway was the rightful “Lady of Scotland”. She was destined never to set foot in Scotland, but, despite her age, gender, and absence from the realm, the country did not descend into complete anarchy in the four years when she was the accepted heir to the throne. Undoubtedly there were people who had reservations about her reign: the Bruces, for example, seem to have attempted a short-lived rebellion, though the situation was soon defused by the Guardians. By 1289 the cracks were perhaps beginning to show, with the death of the earl of Buchan and the murder of the earl of Fife removing two Guardians, who were not replaced. Nonetheless, the authority of the Guardians was recognised in the absence of an adult ruler and they generally attempted to govern competently in the four years between Alexander III’s accident and the Maid of Norway’s own death in 1290.

Having received news of this second tragedy, the Guardians again acted cautiously, deciding that rival claims for the kingship should be judged in an official court chaired by a respected and powerful arbitrator. Thus they appealed to Scotland’s formidable neighbour, Edward I of England. Despite later allegations of foul play, the English king’s eventual judgement in favour of John Balliol does appear to have been consistent with the law of primogeniture and due process. It would take years of steady deterioration before war finally broke out in 1296. By then Alexander III had been dead for a decade, and though the crisis may have indirectly grown out of his demise, it was not necessarily the immediate cause of Scotland’s late mediaeval woes. Nonetheless the events of that dark night in March 1286 would leave their mark on the popular imagination for centuries, shaping Scottish history down to the present day.

(An imprint of the Great Seal used by the Guardians of Scotland following Alexander III’s death. Reproduced in the “History of Scottish seals from the eleventh to the seventeenth century”, by Walter de Gray Birch, now out of copyright and available on internet archive)

Additional Notes:

*The assembled magnates included the earls of Buchan, Dunbar, Strathearn, Atholl, Lennox, Carrick, Mar, Angus, Menteith, Ross, Sutherland, and two other earls whose titles are illegible but who may have been Caithness and Fife. The barons included Robert de Brus the elder (father of the earl of Carrick and grandfather of the future Robert I), James Stewart, John Balliol (the future king), John Comyn of Badenoch, William de Soules, Enguerrand de Coucy (Alexander III’s maternal cousin), William Murray, Reginald le Cheyne, William de St Clair, Richard Siward, William of Brechin, Nicholas de Hay, Henry de Graham, Ingelram de Balliol, Alan the son of the earl, Reginald Cheyne the younger, (John?) de Lindsay, Simon Fraser, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, Angus MacDonald, and Alan MacRuairi, among others.

** The historian G.W.S. Barrow identified this figure as Alexander the saucier the master of the royal sauce kitchen and one of the baillies of Inverkeithing.

*** There are some variations on this local tradition too- in 1794, the minister who wrote the entry for Kinghorn parish in the Old Statistical Account claimed that the ‘King’s Wood-end’ near the site of the current Alexander III monument was where the king liked to hunt and that he fell from his horse while on a hunting trip.

****The Guardians and other nobles may have assembled at Clackmannan for the birth. Several modern historians have accepted Walter Bower’s statement that the queen’s baby was stillborn, despite the Chronicle of Lanercost’s somewhat fantastic tale of a fake pregnancy, with Yolande being caught conspiring to smuggle an actor’s son into Stirling Castle.

Selected Bibliography:

- “The Chronicle of Lanercost”, as translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell

- “Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Preserved Among the Public Records of England”, Volume 2, ed. Joseph Bain

- Rymer’s “Foedera…”, Volume 1 part 1

- “Documents Illustrative of the History of Scotland”, vol 1., ed. Joseph Stevenson

- “Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson (especially Annals of Worcester; Thomas Wykes; Chronicles in Annales Monastici)

- “Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson (esp. Chronicle of Holyrood, various continuations of the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland; John of Evenden; Nicholas Trivet)

- “The Flowers of History… as Collected by Mathew of Westminster”, ed. C.D. Yonge - Gesta Annalia II (formerly attributed to John of Fordun) in “John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W. F. Skene

- John Barbour’s “The Brus”, ed. A.A.M. Duncan

- “The Orygynale Cronikil of the Scotland”, vol.2., by Andrew Wyntoun, ed. David Laing

- “A History Book for Scots: Selections from the Scotichronicon”, ed. D.E.R. Watt

- “The Authorship of the Lanercost Chronicle”, by A.G. Little in the English Historical Review, vol. 31 no. 122, p. 269-279

- “The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

- “Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland”, G.W.S. Barrow

- “The Wars of Scotland, 1230-1371”, Michael Brown

I have extensive notes so if anyone needs a reference for a specific detail please let me know.

#Scottish history#British history#Scotland#thirteenth century#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#1280s#Alexander III#Yolande of Dreux#House of Canmore#Margaret of England#Margaret Maid of Norway#Margaret of Scotland Queen of Norway#Prince Alexander (d.1284)#Edward I of England#William Fraser Bishop of St Andrews#Robert Wishart Bishop of Glasgow#John Comyn of Badenoch#Alexander Comyn Earl of Buchan#James the Steward#Duncan Earl of Fife (d.1288)#Chronicle of Lanercost#Patrick III Earl of Dunbar#Walter Bower#Scotichronicon#Andrew Wyntoun#John Barbour#John of Fordun#Gesta Annalia II#Sources

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wonder what would have happened if the bloodline of Margaret of Denmark’s brothers had died out instead of Margaret Tudor’s

#Scandinavian-Scottish state to make everyone worried not just the English? Or Scotland subsumed into Denmark like Norway#Or would Scotland have simply been too far away to govern effectively and ended up either in chaos or charting its own path#Interestingly because of the 200 year gap it might have had a very different impact than earlier Scottish=Scandinavian marriages#For example if Eric II and Margaret of Scotland had had a son who lived to adulthood instead of the short-lived Maid#That would probably have had a very different effect on Scotland than James IV falling heir to the Danish throne#At least#I don't think that James III had to relinquish all claims to the Danish succession when he married Margaret?#I know James II did for Guelders but that was rather different#And had he not then even trying to govern both Guelders and Scotland at once would hve been a Challenge given the geography#We know what happened when Mary Queen of Scots married Francis II of France#But even that bears comparison with an earlier match- if Margaret Stewart had survived instead of her brother James II#Then Louis XI might have ended up king of Scotland de jure uxoris#Which is a terrifying thought#Though Louis XI did not get along with his wife as well as Francis II got along with his#Not that that's ever been much of a bar to men riding roughshod over their wives' rights in their own kingdoms#God even if Margaret hadn't survived either I can still see Louis XI sticking his nose in if Isabella Duchess of Brittany fell heir#Some think that the entail on the Scottish Crown was still in place then- i.e. that instead of passing to James II's sisters#it would have passed to another male descendant of Robert II#But actually the preparations made for royal marriages in James II's reign indicate that that wasn't the case#And certainly nobody bothered to mention an entail in the reigns of James III IV & V or Mary I#Personally I think that entail disappeared magically when James I took off the DUke of Albany's head if not earlier#You could also contrast the very different reaction that might have occurred had Alexander III and Margaret of England's offspring#succeeded to the English throne in the late 1200s to the reaction just half a century later if Joan of the Tower's brothers#had all died and England had faced the prospect of David Bruce as the husband of their monarch#Both Scotland and England might have had a small problem with that#The issue was not so much the prospect of an English-based king ruling over Scotland#As the prospect of that same king deciding to get rid of native Scottish laws and customs rather than ruling two separate kingdoms#At least from my point of view#Religion changed things too though - par exemple James VI#Anyway I'm getting off topic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 26th 1251 Alexander III, the King of Scots, was married to Margaret, the daughter of Henry III, King of England, in York.

Look at this as a follow on to yesterdays post and an explanation to why King Henry was in the presence of our young King and asked him to pay homage.

With this in mind the new royal couple and wedding party probably didn’t want to stick around and returned to Scotland. But it didn’t all go smoothly at first. Margaret had left behind a warm and loving family to move to a court full of people she didn’t know, which led to a period of severe homesickness for the young Queen.

After writing to her parents complaining that she was badly treated, Henry and Eleanor requested that she be allowed to return home for a visit. The Scottish council who were ruling the country on behalf of Alexander refused the request. In the end Henry and Eleanor gathered an army together and marched north, determined to see their daughter. Margaret was allowed to travel south to visit her parents, and then returned to Scotland.

Alexander was the King who had the misfortune of falling to his death over the cliff at Kinghorn, he left no immediate heir to the throne, the couple had three children, Margaret, Alexander and David but he outlived the three leaving his granddaughter the Margaret, Maid of Norway as the only heir, the run of bad luck continued though as she died of fever at St Margaret’s Hope, Orkney on her way to take the throne in 1290, this led to the Wars of Independence

.

The pics are statues of Alexander at St Giles, and the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and a monument to him near Kinghorn in Fife.

Alexander also outlived his bride, in February of 1275, Margaret fell ill while visiting Fife. She died on February 26th in Cupar Castle. Alexander had her buried in the Abbey of Dunfermline. She was thirty four years old and had been Queen of Scotland for twenty-three years.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Consorts Spam

Margaret of Scotland (1469) also referred to as Margaret of Norway, was Queen of Scotland

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Partial List of Royal Saints

Saint Abgar (died c. AD 50) - King of Edessa, first known Christian monarch

Saint Adelaide of Italy (931 - 999) - Holy Roman Empress as wife of Otto the Great

Saint Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury (died 944) - Queen of the English as wife of King Edmund I

Saint Æthelberht of Kent (c. 550 - 616) - King of Kent

Saint Æthelberht of East Anglia (died 794) - King of East Anglia

Saint Agnes of Bohemia (1211 - 1282) - Bohemian Princess, descendant of Saint Ludmila and Saint Wenceslaus, first cousin of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Bertha of Kent (c. 565 - c. 601) - Frankish Princess and Queen of Kent as wife of Saint Æthelberht

Saint Canute (c. 1042 - 1086) - King of Denmark

Saint Canute Lavard (1096 - 1131) - Danish Prince

Saint Casimir Jagiellon (1458 - 1484) - Polish Prince

Saint Cormac (died 908) - King of Munster

Saint Clotilde (c. 474 - 545) - Queen of the Franks as wife of Clovis I

Saint Cunigunde of Luxembourg (c. 975 - 1033) - Holy Roman Empress as wife of Saint Henry II

Saint Edmund the Martyr (died 869) - King of East Anglia

Saint Edward the Confessor (c. 1003 - 1066) - King of England

Saint Edward the Martyr (c. 962 - 978) - King of the English

Saint Elesbaan (Kaleb of Axum) (6th century) - King of Axum

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (1207 - 1231) - Princess of Hungary and Landgravine of Thuringia

Saint Elizabeth of Portugal (1271 - 1336) - Princess of Aragon and Queen Consort of Portugal

Saint Emeric (c. 1007 - 1031) - Prince of Hungary and son of Saint Stephen of Hungary

Saint Eric IX (died 1160) - King of Sweden

Saint Ferdinand (c. 1199 - 1252) - King of Castile and Toledo

Blessed Gisela of Hungary (c. 985 - 1065) - Queen Consort of Hungary as wife of Saint Stephen of Hungary

Saint Helena (c. 246 - c. 330) - Roman Empress and mother of Constantine the Great

Saint Henry II (973 - 1024) - Holy Roman Emperor

Saint Isabelle of France (1224 - 1270) - Princess of France and younger sister of Saint Louis IX

Saint Jadwiga (Hedwig) (c. 1373 - 1399) - Queen of Poland

Saint Joan of Valois (1464 - 1505) - French Princess and briefly Queen Consort as wife of Louis XII

Blessed Joanna of Portugal (1452 - 1490) - Portuguese princess who served as temporary regent for her father King Alfonso V

Blessed Karl of Austria (1887 - 1922) - Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, King of Croatia, and King of Bohemia

Saint Kinga of Poland (1224 - 1292) - Hungarian Princess, wife of Bolesław V of Poland and niece of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Ladislaus (c. 1040 - 1095) - King of Hungary and King of Croatia

Saint Louis IX (1214 - 1270) - King of France

Saint Ludmila (c. 860 - 921) - Czech Princess and grandmother of Saint Wenceslaus, Duke of Bohemia

Blessed Mafalda of Portugal (c. 1195 - 1256) - Portuguese Princess and Queen Consort of Castile, sister of Blessed Theresa of Portugal

Saint Margaret of Hungary (1242 - 1270) - Hungarian Princess, younger sister of Saint Kinga of Poland and niece of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Margaret of Scotland (c. 1045 - 1093) - English Princess and Queen Consort of Scotland

Blessed Maria Cristina of Savoy (1812 - 1836) - Sardinian Princess and Queen Consort of the Two Sicilies

Saint Matilda of Ringelheim (c. 892 - 968) - Saxon noblewoman and Queen of East Francia as wife of Henry I

Saint Olaf (c. 995 - 1030) - King of Norway

Saint Olga of Kiev (c. 900 - 969) - Grand Princess of Kiev and regent for her son Sviatoslav I, grandmother of Saint Vladimir the Great

Saint Oswald (c. 604 - 642) - King of Northumbria

Saint Radegund (c. 520 - 587) - Thuringian Princess and Frankish Queen

Saint Sigismund of Burgundy (died 524) - King of the Burgundians

Saint Stephen of Hungary (c. 975 - 1038) - King of Hungary

Blessed Theresa of Portugal (1176 - 1250) - Portuguese Princess and Queen of León as wife of King Alfonso IX, sister of Blessed Mafalda

Saint Vladimir the Great (c. 958 - 1015) - Grand Prince of Kiev and grandson of Saint Olga of Kiev

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

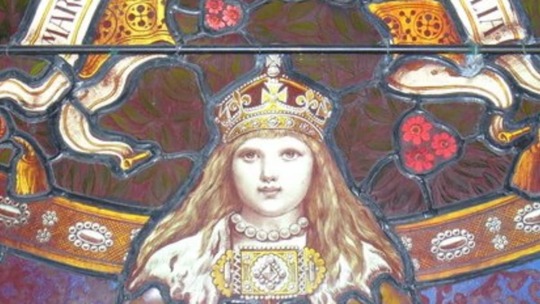

Margaret, Maid of Norway, Queen of Scots (9 April 1283 - 26 September 1290)

#margaret maid of norway#queen of scots#queen of scotland#daughter of eric ii of norway#history#women in history

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[AU: what if the Union of the Crowns had happened... centuries earlier before James VI of Scotland became King of England?]

Margaret, Maid of Norway, becomes Queen of Scotland by right. In an accordance with Edward, King of England, she keeps the independence of the realm to a certain degree if she marries his son, the prince of Wales. Eventually, she is espoused by Edward of Caernarfon, but the marriage is complicated in the beginning. However, Edward and Margaret eventually settle together and their marriage produce the following children:

1. Edward III of England and I of Scotland. He takes as wife Philippa of Hainault, by whom he has 13 children. Edward is the responsible for splitting the realms again... He makes Lionel, his favourite son, the king of Scotland, whilst appointing Edward, his oldest son, heir to England. Lionel takes as wife a granddaughter of the powerful nobleman Robert the Bruce.

2. Margaret, Queen of Norway. She marries Margaret’s nephew, her first cousin, by whom she has at least three children.

3.Eric, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor. He takes as wife a daughter of the duke of Burgundy.

4.Eleanor, Duchess of Brittany. Named after Margaret of Scotland’s grandmother, this princess is espoused by the duke of Brittany, by whom she has at least 5 children.

5.Henry, Duke of Albany. He takes as wife a daughter of the king of France. They have issue.

6. William, Earl of Cornwall. He takes as wife a granddaughter of Alfonso X of Castille.

7. Mary, Countess of Guelders. She is espoused by the Earl of Guelders, but they don’t have issue.

#i do NOT claim to own any of those gifs#found them online with the ONLY purpose to play with history#if however any of these gifs belong to anyone please let me know so I can credit them properly#margaret of norway#maid of norway#queen of scots#edward ii#king of england#plantagenet#alternative universe#charlize theron#freya allan#essie davies#fancast#timothee chalamet

19 notes

·

View notes