#Lakota Warrior

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

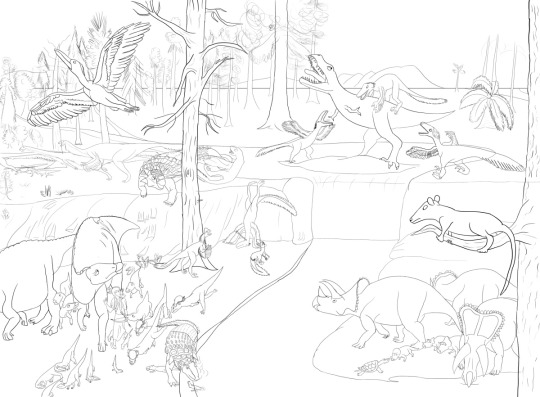

Walking in the Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota Drawing

Work In Progress: Walking in the Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota.

View On WordPress

#adobe photoshop#ankylosaurus#artistatwork#Commissions Open#Concept Art#Dakotaraptor#Digital Art#digital drawing#DigitalPainting#dinosaur#Dinosaur Art#Environment Design#female warrior#hell creek#hell creek formation#Lakota#Lakota Tribe#Lakota Warrior#landscape#landscape art#Native American#paleontology#Palo Art#South Dakota#T-Rex#triceratops#Wacom Tablet#Workinprogress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's not Black and White

Our god has no rules only ceremonies to know him better.~Lakota Warrior Part and parcel of being raised in a monoculture is the gradually built hubris wherein the world is divided into two distinct antithetical halves. They are ‘our way’ and the ‘wrong way.’ It sets the stage for the curse of binary thinking, an almost complete inability to see shades of grey, including the inability to…

0 notes

Text

Lakota Warrior

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Folks go missing in the park at night"

#the outsiders#the outsiders musical#johnny cade#sky lakota lynch#ralph macchio#warriors album#warriors musical#folks go missing in the park at night

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shield by He Nupa Wanica/Joseph No Two Horns

Currently on display as part of the MET’s Art of Native America exhibit, this type of shield would have been carried into battle; it’s vision-inspired imagery offered spiritual protection. Joseph No Two Horns was one of the most prolific Plains artists and his artwork helps to identify the tribal history of the Lakota. His work depicts specific events in his own life as well as the lives of other Lakota people. A warrior by the age of fourteen, No Two Horns participated in at least 40 battles during his life, including the Battle of Little Big Horn. No Two Horns also kept his tribe’s winter count, a collection of pictographs recording 137 years of Lakota history.

Article on Joseph No Two Horns, American Indian Art Magazine, 1993

More information

0 notes

Text

Outlander || Series Masterlist

Pairing: Dean Winchester x OFC

Summary: Dean Winchester has been stripped of his military rank, but he’s living happier with his new wife, trying to adjust to a new life in her tribe. What will it take for her people to accept him, especially when the battle for her heart might not be completely won?

AN: So this is a sequel story directly following The Honorable Choice, where Dean not only saves the member of a Native American tribe, but falls in love with her. (She saves him a lot in return.) Now, he’ll have to learn how to live in her world if he wants to stay with her.

Disclaimer: I first got inspired to write The Honorable Choice for @jacklesversebingo after a recent rewatch of Spirit: The Stallion of the Cimarron (with a tinge of Yellowstone in the mix). I’ve done a lot of research for this whole series, both on the Native American Lakota tribe, and on American history during this time in the late 1800s; AKA: the Old West, during the American Indian Wars.

Jacklesverse Bingo24 Prompt: Western AU

Tags/Warnings: 18+ only for smut, Protective Dean, (and rogue/cowboy Dean), survival situations, hunting (in the more traditional sense), suggestiveness/implied smut and spice throughout, angst, blood and violence, hurt/comfort, and romantic fluff. (Plus other chapter-specific tags.)

Chapters:

Part 1 - Two Worlds

Part 2 - What is Home

Part 3 - A Warrior's Death

Part 4 - One People

Series is complete!

Join My Patreon 🌟 Get early access to new stories, bonus content, and first looks at upcoming stories, send me requests, and more!

The Honorable Choice Masterlist

Jacklesverse Bingo24 Masterlist

Dean Winchester Series List

Dean Winchester Masterlist

Main Masterlist

Comment below if you'd like to be tagged in this series! 💜

Or follow @zepskieswrites (with notifications on) to get notified every time I drop a new story or chapter.

Series Tag List (Part 1):

@hobby27 @kazsrm67 @letheatheodore @agothwithheavysetmakeup @jacklesbrainworms

@foxyjwls007 @wincastifer @thebiggerbear @roseblue373 @this-is-me19

@emily-winchester @spnexploration @deans-spinster-witch @deans-baby-momma @iprobablyshipit91

@sanscas @sleepyqueerenergy @wayward-lost-and-never-found @kaleldobrev @spnwoman

@thewritersaddictions @just-levyy @samanddeaninatrenchcoat @pieandmonsters @globetrotter28

@adoringanakin @theonlymaninthesky @teehxk @midnightmadwoman @brianochka

@chevroletdean @agalliasi @chriszgirl92 @lyarr24 @kayleighwinchester

@ladysparkles78 @solariklees @deansbbyx @candy-coated-misery0731 @curlycarley

@sarahgracej @bagpussjocken @deanfreakingwinchester @chernayawidow @mimaria420

@fics-pics-andotherthings-i-like @waywardxwords @waynes-multiverse

#Outlander Masterlist#The Honorable Choice#Jacklesversebingo24#dean winchester#dean winchester angst#dean winchester x oc#supernatural#spn#dean winchester fanfiction#dean x oc#dean winchester imagine#dean winchester smut#dean winchester fanfic#supernatural fanfiction#supernatural x reader#spn fanfic#jensen ackles#jensen ackles x oc#jensen ackles fanfiction#jackles#dean winchester au#western au#dean au#dean winchester x original character#dean winchester x original female character#dean winchester x ofc#sam winchester#benny lafitte#sam and dean#zepskies writes

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakota Trinity by the late artist Father John Giuliani

"In this image, the great Father—Wakan Tanka—appears with a full headdress of eagle feathers in a halo of light.

His open hands deliver the Son, a victorious Sioux warrior whose raised arms and open hands reflect a similar gesture of self-giving.

He wears a richly decorated buckskin war shirt—heavily fringed, beaded and painted with the four color circle of the universe as its breast plate.

The eagle represents the Holy Spirit and completes the spiral of trinitarian love and unity."

From the Catholic Extension Society.

#religion#christianity#catholicism#native american#trinity#holy trinity#god#trinity sunday#art#divinum-pacis

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Organizations To Help Indigenous People

I've been reblogging three separate posts for a while now and I thought I'd combine them all into one for maximum ease. Please reblog this list and help these organizations if you can!

Warrior Women Project

Sitting Bull College

First Nations COVID-19 Response Fund

The Redhawk Native American Art Council

Partnership With Native Americans

Native American Heritage Association

National Indigenous Women's Resource Center

Indigenous Women Rising (abortion access fund)

Indian Residential School Survivor’s Society

Stop Line 3

Honor The Earth

The Lakota People’s Law Project

Amazon Frontlines

‘Āina Momona

The Native Wellness Institute

The Native Americans Rights Fund

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation/University of Manitoba

First Nations Child & Family Caring Society

Native Women's Association of Canada

Indspire

Mi'kmaw Native Friendship Centre

Micmac Benevolent Society

Mawita'mk

Advancing Indigenous People In STEM

Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment

The Association on American Indian Affairs

First Nations Development Institute

American Indian College Fund

Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment (CARE)

Hopa Mountain

Indigenous Values Initiative

Native American Disability Law Center

People’s Partner for Community Development

If anyone has links to other organizations that help indigenous people, please feel free to add them!

#indigenous people#native americans#native canadians#indigenous organizations#support indigenous people#support native people#signal boost#for a good cause#please reblog#please help#please share#please donate

549 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐲 𝐍𝐨𝐬𝐞 🌻🌻

Pretty Nose : A Fierce and Uncompromising Woman War Chief You Should Know

Pretty Nose (c. 1851 – after 1952) was an Arapaho woman, and according to her grandson, was a war chief who participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.In some sources, Pretty Nose is called Cheyenne, although she was identified as Arapaho on the basis of her red, black and white beaded cuffs. The two tribes were allies at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and are still officially grouped together as the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

On June 25, 1876, a battalion of the 7th Cavalry, led by George Armstrong Custer, was wiped out by an overwhelming force of Lakota, Dakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

There are many stories that come from this most famous battle of the Indian Wars. However, the most overlooked account is of the women warriors who fought alongside their male counterparts.

Minnie Hollow Wood, Moving Robe Woman, Pretty Nose (pictured), One-Who-Walks-With-The-Stars, and Buffalo Calf Road Woman were among the more notable female fighters.

Pretty Nose fought with the Cheyenne/Arapaho detachment.

One-Who-Walks-With-The-Stars (Lakota) killed two soldiers trying to flee the fight.

Minnie Hollow Wood earned a Lakota war-bonnet for her participation, a rare honor.

Lakota Moving Robe Woman fought to avenge the death of her brother.

And Cheyenne Buffalo Calf Road Woman holds the distinction of being the warrior who knocked Custer off his horse, hastening the demise of the over-confident Lt. Colonel.

Pretty Nose's grandson, Mark Soldier Wolf, became an Arapaho tribal elder who served in the US Marine Corps during the Korean War. She witnessed his return to the Wind River Indian Reservation in 1952, at the age of 101.

#Pretty Nose#Lakota#Cheyenne/Arapaho#Woman War Chief#Battle of the Little Bighorn#1876#Other Lives#Past Times

165 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Man Who Married the Thunder Sister

The Man Who Married the Thunder Sister is a legend of the Cherokee nation about a young warrior who falls in love with a Thunder Sister and follows her home where he finds nothing is what it seems to be, not even the young woman. The story explores many themes common to Native American literature.

Ojibwe Shoulder Pouch Depicting Two Thunderbirds

Daderot (Public Domain)

Among these is the importance of following instructions and of faith. According to Cherokee belief, the Creator God Unetlanvhi, made the tri-level world with good spirits above, bad spirits below, and humanity in the middle world, tasked with maintaining balance. Spirits from either plane could manifest themselves on earth at any given time – sometimes threatening this balance -–and so people were encouraged to proceed, in anything, through faith in Unetlanvhi to discern what kind of entity they might be encountering, whether a threat to harmony or a guide in helping one maintain celestial and terrestrial balance.

In the case of the young warrior in this story, as he follows the young woman and her sister toward their home, he is shown that his senses are deceiving him and the waters he encounters on the journey are not as they appear, but upon reaching their cave, he forgets the lessons learned, abandons his faith, and relies on his own senses. According to some interpretations of the story, he has been tested and has failed in recognizing the sisters as beneficial guides. Trusting in his own judgment, instead of proceeding by faith, he is led astray.

He later fails to heed the instructions given to him by the sisters that he should tell no one where he had gone or what he had seen there, and he suffers the consequences. This theme appears in the legends and myths of many different Native American nations and is often repeated in a cycle of stories – such as the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne or the Iktomi tales of the Lakota Sioux – in which a character repeatedly fails to follow simple instructions and must then suffer for it. The importance of following instructions appears so often in Native American tales because it is a common cultural value. Part of maintaining balance in life is recognizing and honoring tradition and the rituals that are a part of that. Deviating from how something has always been done runs the risk of throwing an individual, or community, off balance.

Another theme central to the story is the danger of blindly trusting strangers, no matter how friendly or welcoming they may appear, as they might be ghosts or evil spirits who have appeared only to lure one into trouble or strike one with sickness or even death. This theme usually runs through Native American ghost stories as ghosts, even of loved ones, were thought to sometimes appear only to draw one with them into the afterlife, and before one's appointed time. In this story, the young man instantly engages with the two beautiful sisters, even though they have never been seen in the village before, and, ignoring the traditional wisdom of approaching strangers with caution, happily follows them home.

This is not to say the Cherokee – whether in the past or present – do not welcome strangers into their community, as they certainly did and still do, but it is thought prudent to proceed with caution, trusting in one's faith to discern bright energies or dark energies in a new acquaintance. Failure to do so, as seen in the stories of many different nations, always leads to serious problems. In this story, the young warrior never pauses for a moment to question who the young women are or where they have come from and so, unwittingly, is led to the home of the Thunder Beings.

Thunder Beings & Horned Serpents

The Thunder Beings, according to some Cherokee bands (not all) are storm spirits descended from Selu, the corn goddess, through her sons, the Thunder Boys (Wild Boy and Good Boy), all featured in the Cherokee myth, The Origin of Game and Corn. The Thunder Boys are trickster figures – often playing with people's perceptions of reality – and so it is no surprise that their children should do the same, as the women do with the young warrior in the story. The Thunder Beings live in the west, the cardinal point sometimes associated with death and the afterlife, but are life-giving spirits as they bring rain, which fills the streams and makes the crops grow. They are the personification of thunderstorms, as scholar Larry J. Zimmerman explains:

Native Americans believe that the forces of nature – which include summer, winter, rain, lightning, and "the four winds" – are controlled by elemental gods and spirits to whom the various powers of the Great Spirit are delegated. Many peoples of the Great Plains think in terms of spirits of earth, fire, water, or air (thunder, one of the mightiest forces, is an air god). Elemental entities feature in the lore of most tribes, but they are understood in divergent ways…The underworld spirits, headed by dragon-like deities that are usually represented as panthers or horned serpents, are generally regarded as malevolent.

(162)

The Thunder Beings in Cherokee lore correspond to the Thunderbird recognized by many of the Plains Indians as the bringer of storms. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

Every aspect of a storm was explained by the actions of the Thunderbird: thunder was the flapping of its wings; the storm cloud was caused by its approaching shadow. Its blinking eyes caused lightning. And rain poured down from the lake carried by the bird upon its back.

(479)

In this same way, a Thunder Being brought storms simply by moving from one place to another. In the following story, the brother of the two women arrives home with a clap of thunder, in keeping with the understanding of how a Thunder Being would announce himself. The Thunder Beings were to be respected, not feared, while the horned serpents Zimmerman references were always to be avoided.

Among the most terrifying of these serpents was Uktena, the great serpent with the powerful jewel in its forehead, featured in the Ulunsuti tales. When Uktena is taken up into the higher realm so that his activities can be monitored, he leaves behind smaller versions of himself, all possessing some of his immense chaotic power. This is the kind of snake the woman brings into the cave in The Man Who Married the Thunder Sister, and so the young warrior's reaction is justified, but, as he has already learned that he needs to walk in faith and not trust his senses, he should, by this point, understand that the "uktena snake" he thinks he sees is probably something else, most likely a horse.

Rock Art Depicting a Horned Serpent

E. Kay Luther (CC BY-SA)

As with all Native American stories, legends, and myths, The Man Who Married the Thunder Sister can be interpreted in various ways. Perhaps the young warrior fell under a spell to test his discernment and failed, or it could be that, until his lapse in not following instructions, he behaved as he should have in rejecting what is offered by elemental spirits he has no business dealing with. The story is as popular today as it was in the past, however, and, as noted, continues to lend itself to many different interpretations.

Continue reading...

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walking in the Hell Creek Formation: South Dakota

South Dakota during the Twilight of the Dinosaurs

View On WordPress

#adobe photoshop#ankylosaurus#artistatwork#Commissions Open#Concept Art#Cretaceous period#Dakotaraptor#Digital Art#Digital Painting#dinosaur#Dinosaur Art#edmontosaurus#Environment Design#female warrior#hell creek formation#Lakota Sioux#Lakota Sioux Tribe#Lakota Tribe#Lakota Warrior#Landscape Painting#Native American#paleontology#Palo Art#prehistoric life#South Dakota#tyrannosaurus rex#Wacom Tablet

1 note

·

View note

Photo

[image description: gifs stacked vertically of Native American warriors of various tribes, in traditional attire and in the fashion of their tribe. Text overlays on top of each gif, labeled, in order: “Brave’s society of Young Warriors, Blackfoot.”, “Women Warrior’s Society, Cheyenne.”, “Black Knife Society, Comanche.”, “Okichitaw, Cree.”, “Crazy Dogs, Crow.”, “Koitsenko, Kiowa.”, “Kit Fox Society, Lakota.”, “Iruska, Pawnee.”. end image description.]

Plains Native American Warrior Societies

(not an exhaustive list)

#historyedit#history#native american#plains native#plains indian#ndn#indigenous#native american history#first nations history#american history#canadian history#justin's edits

453 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch ARK: The Animated Series!!!!

So, I binged ARK: The Animated series today. It's a TV show, which is based on a video game and not only is it great but, I swear to God, whoever wrote this set out with the intention of pissing off the Gamerbro crowd as much as humanly possible.

Stuff that will make the Gamerbros cry and whine like little babies: 01). Main Character is a Aboriginal Australian Lesbian (Voiced by an Aboriginal Australian Actress no less). 02). Main Character's wife is a blue haired women who works as a translator for a humanitarian air organization (voiced by Elliot Page). 03). Main Character is a neurodivergent paleontologist. 04). Main Character's mother was a civil rights activist. 05). There's a plot line revolving around protesting the taking of Aboriginal lands. 06). Another major character is a Chinese Warrior Woman who is also a great big lesbian (voiced my Michelle Yeoh). 07). Main villain is a Roman General (Voiced by Gerard Butler) 08). Secondary Villain is an 19th century British Scientist (Voiced by David Tenant) 09). Tertiary Villain is a female Roman Gladiator. 10). Another major character is a Lakota man from the 19th century who was abducted from his tribe and sent to one of the Indian boarding schools. 11). The Main Character is better at science than the 19th Century British Scientist guy.

Great things about the show: 01). It's very gay. Like, so gay. 02). The characters are freaking awesome. 03). There are freaking dinosaurs. So many dinosaurs. 04). It makes you feel. Just, seriously, it makes you fucking feel.

Cons: 01). Content Warning: Self Unaliving in episode 1 02). This show is fucking violent. Like, I get that there's this whole 'battle for survival' thing going on, but we're talking kind of gratuitous 03). levels of violence. Seriously, half the animation budget was spent on red paint. That much violence. 04). The show is predictable AF. Like, I don't mind that, but don't expect any real surprises or plot twists.

In conclusion: Watch the fuck out of this show, because cons aside, it was freaking amazing. It's not like, Arcane levels of perfection, but if you want a fun, gay, show to watch, this is a great choice. There is also a part too already filmed and in the can which will drop later this year, so we're definitely getting more, and even the preview for Part II has gay in it.

#ark the animated series#ark: the animated series#lesbian characters#lesbian tv#sapphic characters#sapphic tv#representation#minor spoilers#cw: blood#cw: gore#dinosaurs#ark tas

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

I should be sleeping rn

The crossover nobody asked for but I needed

#warriors album#warriors musical#lin manuel miranda#the outsiders#the outsiders musical#the outsiders johnny#johnny cade#folks go missing in the park at night#sky lakota lynch#ralph macchio

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

The warrior is not someone who fights, for no one has the right to take another life. The warrior, for us, is the one who sacrifices himself for the good of others. His task is to take care of the elderly, the defenseless, those who cannot provide for themselves, and above all, the children, the future of humanity.

~ Sitting Bull, chief of the Lakota nation

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander - Part 3

Pairing: Dean Winchester x OFC

Summary: Dean Winchester has been stripped of his military rank, but he’s living happier with his new wife, trying to adjust to a new life in her tribe. What will it take for her people to accept him, especially when the battle for her heart might not be completely won?

AN: Back into the saddle, so to speak. 😏 Plus, we have a very special guest joining the cast...

Disclaimer: I first got inspired to write The Honorable Choice for @jacklesversebingo after a recent rewatch of Spirit: The Stallion of the Cimarron (with a tinge of Yellowstone in the mix). I’ve done a fair bit of research for this now ongoing series, both on the Native American Lakota tribe, and on American history during this time in the late 1800s; AKA: the Old West, during the American Indian Wars.

Jacklesverse Bingo24 Prompt: Western AU

Song Inspo: The Spirit Soundtrack

Word Count: 8.1K

Tags/Warnings: 18+ only! Smut, fluff, angst, hurt/comfort, blood and character death.

🐎 Series Masterlist || Bingo Masterlist

Part 3: A Warrior’s Death

Mila has never enjoyed being an early riser, but sometimes, it has its benefits. In the rare times that she wakes up before Dean, she’s taken to counting the small nicks and scares that mark his body, from his chest and arms and back, down to his calloused hands. They mark him as a warrior.

Today, she slips her fingers through his brown hair. It’s grown a little more, and it’s easy to spike wildly in all directions. His breathing shifts from the deeper, slower ones of sleep to shallower ones.

“What’re you doing?” he grumbles, despite the way his lips twitch at a smile. His eyes are still closed.

“It’s morning, and I’m lonely,” Mila teases. She leans in to kiss his chin, then slowly and sensuously across his prickly jawline.

“Can’t you entertain yourself until the sun comes up all the way?” he says, in a voice laden with grit and sleep.

“That is what I’m doing,” is her cheeky reply.

Dean releases a deep breath that’s more like a sigh. Mila continues, smoothing her hand across his shoulder and squeezing warmly as she makes her way down his neck with kisses. She takes to nibbling his skin, then soothing it with her tongue. He makes a throaty sound of pleasure, gripping her hip.

“Wake up, my love,” she whispers.

Dean feels the shape of her smile against his skin. His lips tug upwards too, before he chuckles and finally succumbs to her wily ways. He twists onto his back and takes her with him, guiding her leg to slip over his lap. She squeals in surprise to be moved, but it ends with her smiling down at him as she straddles his hips. His hands travel under her the thin fabric of her shift and squeeze the supple flesh of her thighs.

Her fingertips drag down his chest, teasing his nipples along the way. She begins to tease him in other ways too, subtly rolling her hips, rocking against his hardening length. She wears a heated, playful look he knows all too well. He smirks up at her lazily.

“You’ve been more demanding than usual,” he remarks. His hold on her hips tightens, encouraging her to grind down harder onto him. He groans in pleasure at the feeling of her bare, wet folds against his clothed erection. Still, he can’t help but tease her too. “You already got what you wanted. I got you good and pregnant.”

His knees slide up to press against her ass, angling her more firmly against his cock. She hums in pleasure at the feeling of him, nice and hard and ready to fill her. It doesn’t matter that he’s right.

She’s pregnant, and has been for over a month now, according to Eyota. Even so, Mila still craves her husband. She wants to take advantage of a good morning, one where she doesn’t feel sick to her stomach.

“Yes,” she agrees, “but you think that means your duty is done?”

She takes his hands from her thighs and moves them up her body underneath her shift, until he can palm her breasts. He obliges her, rolling the sensitive buds under his thumbs.

Dean chuckles deeply. “Haven’t you had enough?”

“I will say when I’ve had enough,” she quips back.

He smiles, more genuinely this time. “Yes, ma’am.”

He takes back control of his hands. One holds her steady by her waist, while the other drags back down her body, brushing over the thatch of hair covering her mound. His fingers slip between her wet folds, and they find what they’re looking for.

She utters a keening moan when the pads of his fingers probe gently at her entrance, pushing inside for a few pulsing beats. He gathers some wetness there and begins to circle the sensitive bundle of nerves above her entrance. She grinds her hips down as she tries to press into his hand. A shudder of pleasure tingles down her spine and throbs deliciously in her core.

She grips his arms tight. “Please,” she says, “I’m ready for you.”

“Already?” he smirks. “I’ve barely touched you.”

Instead of answering him, she drags down his pants herself and reaches for his heavy cock. He moans at her touch, demanding, but still careful as she pumps him to full readiness. Then she notches him at her entrance. Dean grabs her hips and slowly guides her over him in one smooth plunge.

Their breathing becomes more labored as they take beat, just to revel in the connection.

During the day, they both lead busy lives. They each do their part for the tribe to make sure there’s food to eat, clothes to wear, and that the tribe stays protected—but the time they spend together here doesn’t need to be rushed. This is their time.

Mila hesitates to move though, her hands flexing on his shoulders. Her thighs squeeze his hips experimentally.

“How should I move?” she asks in a whisper. “I’ve never…ridden you.”

Dean grins. He rubs her thighs encouragingly. “Trust your instincts, baby. Try just rocking on me.”

He helps her by guiding her hips in a smooth, rolling rhythm, in and out. Mila moans as the shallow friction builds a slow momentum inside her.

“See,” he pants, “you’re a natural.”

She smiles, her face warming in a blush. As she craves more, she becomes bolder, letting his cock drag out of her almost to its tip, before she pushes all the way back in. Dean utters a faltering moan, and tries not to let his eyes close in pleasure. He wants to keep watching the way she gets herself off on his cock, the way her full breasts bounce with her movements.

Dean’s hands slide up her back to feel the gentle slope. He leans up to kiss and suck at her tightened nipples, his teeth catching on them. She gasps and arches against him. Her nails scramble for purchase between his shoulder blades.

Dean chuckles into her skin. “So sensitive. Being so fucking good for me, huh baby?”

Mila nods, half out of her mind. He blazes an upward path, kissing and sucking between her breasts, along the line of her collarbone, and then at her neck. He stops there to suck hard at her pulse point, burying his fingers tightly in her hair.

She moans and clings to him as she rocks a harder rhythm on top of him. She chases her release, and tries to help him reach his. But when his fingers slip in between them to massage her clit again, she shudders deeply and gasps. “Dean.” Her inner walls clench tightly on his cock and begin to flutter and pulse around him.

He drives his hips up into her with a few wild, harsher thrusts with his own release. He grunts sharply into her neck as he spills deep inside her.

Mila holds him tightly to her while her heart races. She pants for breath, huffing because her hair has fallen into her eyes. Dean brushes the strands behind her ear as he too catches his breath. He lays back down and takes her with him, gratefully stroking her back.

“Well, good morning,” he says. His voice is like hot gravel. “Fuckin’ hell…”

She giggles breathlessly against his chest. By now she’s learned many of the English curse words. They often sound both harsh and funny to her. Though she knows that right now, it’s a compliment.

They lay together for a while, even after she untangles herself from him and grabs a washcloth to clean them both. She finds herself led back into Dean’s embrace under the warm furs. His large hand spans her lower belly, resting there.

“You want a boy or a girl?” he asks. His deep voice is still a bit coarse with sleep.

Mila considers his question while pillowing her cheek against her folded arms.

“I want to give you a son,” she says.

Dean’s lips twitch into a smile. He hums thoughtfully while he slips his fingers through her hair.

“I guess that means I’ll have to teach him things. Things about the world,” he says. She turns in his arms to face him.

“What would you teach him?” she asks, with a smile of her own. She asks the question not only because she genuinely wants to know, but because she likes the soft glow of optimism and possibilities reflected in Dean’s eyes. In some ways, he’s already different from the hardened soldier she first met. Or maybe she’s just continuing to learn more and more of who he really is—layer by layer.

“Well, how to learn from his mistakes, for one thing,” he says. “How to protect himself, and his family. How to survive, but also how to live.” He thinks about it a bit harder for a second.

“Come to think of it, I’d teach my daughter all that too,” he says. “So I guess I’ve got no preference.”

And we can always try again, he thinks.

“He will be strong, like his father,” Mila says.

“Or like his mother,” Dean playfully replies. She smiles back, and she leans forward to kiss his lips. She cups his cheek with a gentle, loving hand. Dean squeezes her waist and pulls her tighter against him.

“Are you two going to sleep all day, or are you going to join the rest of the world and start working?” Šóta interrupts, loudly from outside their tipi. “The horses need to be fed, Horsemaster.”

Dean and Mila break apart from the kiss, and they share a look, hers more annoyed than his. Her cousin has taken what she said to him before about being a leader to heart, if in some unexpected (and annoying) ways.

She sighs, but unfortunately, Šóta has a point. It prompts them to get up and start getting dressed.

“What do you got planned today?” Dean asks, while he tries to find a clean shirt.

“I have some mending to do and laundry to take down. Then I will help my aunts skin the hides and prepare the vegetables for lunch and supper,” she says.

He pauses, leveling her with a warning look. “Hey, remember to take it easy, all right. Don’t strain yourself.���

She just smiles and touches his cheek. This man is a protector in all senses, and it seems, also a worrier.

Dean takes pride in corralling the horses and making sure they’re fed, brushed, and given water. Just like he suspected would happen, Mato and Baby have been getting along a little too well. She’s now pregnant too.

Ironically enough, it means she’ll give birth to her foal around the time Eyota believes Mila will deliver their child, maybe a month or two after.

Ain’t that just life, he thinks.

There’s another colt that Dean has spent the past week breaking in. He’s wily and precocious, giving Dean a challenge, but that’s what he likes about the guy.

“You’ve got spirit, kid, I’ll give you that,” Dean says.

He has a rawhide lead tied around the horse’s neck while he runs around the corral. He’s waiting until the horse tires himself out, so Dean can really begin training him, getting him used to a bridle, teaching him verbal cues, and all the rest.

Back at Fort Laramie, there were those like Colonel Sanderson, who believed that breaking a horse meant you had to break his independence, his spirit. Dean’s father had always taught him that a bond between him and an animal, a bond based on trust, will serve him better with a loyal horse rather than just an obedient one. He’s glad that the Lakota here share his views on horse rearing.

At about mid-morning, Chatan comes over to inspect Dean’s progress. His ankle has healed, mostly, but he’s allowed Dean to take over the harder work when it comes to breaking the horses. Chatan is still teaching him their ways in training them, making bridles and simple saddles, and all the other ways they care for their horses here. He inspects Dean’s work with the colt and nods.

“You’re doing well,” he says.

That’s a big improvement from all the times he’s given Dean some form of correction or instruction. Dean is about to reply, when Šóta and Takoda come over the hill on horseback. Šóta calls for both Chatan and Dean—especially Dean.

“You should see this,” Šóta says.

“Are the other men coming?” Dean says, keeping his voice low as Baby plods along beside Šóta.

“No,” Šóta replies. “We must keep the group small.”

Dean namely meant Otaktay, who still tries his best to ignore him.

Takoda has warmed up to him more though. He doesn’t call him Outlander anymore, let alone wašíču. He’s also the tribe’s best fisherman, and when they eat lunch together, he’s started to save Dean the second-biggest fish after Šóta.

Takoda even showed him how to fletch his own arrows. And when Dean broke his whet stone while sharpening his knife, Takoda gave him his own whet stone.

“I make new one,” he said, in broken English, even with a smile. “This one old anyway.”

At first, Dean used to wonder why some people in the tribe seemed to have better English, like Mila, Tahatan, and Šóta, but others didn’t. After he thought about it more, he supposed he wouldn’t want to learn his enemy’s language. He asked Šóta about it once.

“It’s the opposite for me,” Šóta told him. “I want to know what my enemy says behind my back. Then, I will be ready when he strikes.”

He now leads them away from the forest and across the grasslands. In an hour, they reach a desert valley, where Dean already hears the construction. A new stretch of railroad is being laid out, courtesy of the U.S. government. Dean even spots Benny, Jack, and Colonel Sanderson himself supervising the construction.

Shit, Dean thinks.

They stealthily crept back into the forest and returned to the village. They bring the news of what they saw to Chief Tahatan in his tipi. His wives are there, along with Chatan, Weaya, Mila, Eyota and her husband Hanska. The last two are the medicine man and woman of this tribe, but Hanska is also their wiseman. He advises the Chief.

“We should move the village again, farther north along the river,” Hanska suggests.

“And what? They will keep pushing us back until there is nothing left—until we fall of the edge of the earth!” Šóta shouts. He’s getting more and more angry as the conversation becomes a deliberation on what to do next.

“It’s the Northern Pacific Railroad,” Dean says. He doesn’t know if it’s place to speak, but he feels that he has to. “They mean to keep building until they reach the coast in the Northwest.”

“See? They will rape more and more of the land to do it,” Šóta says. “Our land. We cannot let this stand.”

Dean gives him a wary look. “This is bigger than the tribe. If you try to hit them, they’re just gonna hit back harder. And they’re going to bring the full weight of the U.S. Army on top of you.”

“So what do you suggest we do, Dean Winchester?” Tahatan says. “Sit and do nothing while they continue to carve into our home, where we have lived and died for generations?”

“I think…you should look at the faces around you,” Dean says. “Ask yourself how many of them you’re willing to lose.”

That evening in the privacy of their tent, Dean tries his best to soothe Mila’s worry, but his own trepidation and sense of urgency wins out as he paces back and forth.

“Just moving up the river won’t be enough,” he says. “We could go southwest into Montana, towards the Yellowstone River.”

Mila shakes her head warily. She sits by the fire and watches him cross the room again. He makes her anxious, and so she grabs onto his hand and leads him to sit beside her.

“The Crow people live along Yellowstone,” she says. “The Lakota have fought them for generations.”

“About what?”

“Land,” she admits. “Our tribes are proud and do not like to share hunting territory. The Crow are bitter enemies. They will not accept us there.”

That is putting it mildly. She shudders to think what the Crow would do to them if they crossed paths in their own land.

Dean nods. “Okay, well, what about if we go further north?”

She ponders the idea. Even though she doesn’t like the idea of leaving the river, where her people have settled for decades, she believes what he says is true. Her people wouldn’t win in a head-on fight against the U.S. Army.

“East of Big Cheyenne, there is a bigger territory of land. Other Sioux tribes live there,” she says. “The path is long from here to there, but it could be the answer.”

“Okay, that’s good,” Dean nods. “…I just don’t know how Tahatan and the rest of ‘em are gonna take the idea coming from me. To them, I probably sound like a coward.”

Mila shakes her head and grasps his arm. “You are no coward, Dean. I will help you talk to my father. When he understands, then we will speak to my uncle.”

“And Šóta?” Dean says wryly.

“Šóta is young and wants to prove himself to my uncle. He is brave and strong, but doesn’t consider what we could lose,” Mila says, holding a hand over the small swell of her stomach. Dean covers her hand with his.

“Whatever comes next, I’m not letting anything happen to you. You understand?” he says.

Her face, and the tension in her shoulders, relax. She doesn’t quite manage to smile, but she rests her head against his shoulder.

“Yes,” she nods.

Days become a week, and the men of the tribe begin to notice Cavalry patrols edging closer to the village. Too close.

Dean tries to convince Šóta to let them pass by in ignorance. Attacking them would not only heighten the risk of the military discovering Dean’s alive, but it would just put the entire tribe in more unnecessary danger.

It’s getting harder and harder each day to persuade Šóta to stay his hand, so it becomes even more important to convince the Chief to mobilize the tribe.

While Dean and Mila manage to get Chatan to see the wisdom in the idea of moving the village north of the railroad, Tahatan isn’t so easily convinced that they should leave the river where their tribe has tilled the land, fed their families, built their traditions and their way of life. It’s understandable, but it leaves Dean with a worry in his gut that only grows with every new day.

Mornings are no longer peaceful for him, and while he knows Mila’s beginning to notice, it’s something he can’t help.

They dress for the day in silence after breakfast. He straps his gun to his right thigh and his knife on the other—a new precaution he’s started taking.

“Don’t go past the corral by yourself,” he warns Mila, when he sees her piling up a bundle of clothes for washing. She glances up at him with raised brows.

“I’m only going to the river,” she says.

“Take someone with you,” Dean says, shaking his head. “Like your mom, or a couple of your aunts. Hell, take Šóta with you. Or at least Takoda.”

She gives him a look that says she’s trying to be patient. “I will see if others have washing to do.”

Dean stops her with a hand on her arm.

“Or you could wait ‘til I get back,” he says. “I don’t mind going with you.”

“Dean,” she replies, her brows furrowing. “I may be with child, but I don’t need a caretaker. I’ll be fine.”

Again he stops her from moving past him. “Hey. Just listen to me, damn it!”

She gives him a sharp, surprised look. He stops himself short and realizes he’s losing his temper. He takes a breath, his face tight with frustration.

Mila frowns at him, trying to keep her own temper from rising to the surface. She knows he only wants to protect her, but nothing has even happened. Cavalry patrols haven’t gotten more than a couple of miles close to the village as the railroad construction continues. She’s begun to wonder if it’s necessary to move north after all.

Dean sighs, raising his hands in apology. He gently grasps her arms and looks down at her, meeting her gaze.

“Sorry,” he says. “Just…humor me, okay?”

Her brows furrow. “Humor? You want me to laugh at you?”

At that, he actually breaks into a chuckle. It eases some of his tension, but doesn’t completely expel his worry.

“What I mean is, I know how I’m being right now. I just want you to be safe,” he says, staring into her eyes. “Actually, I need it.”

Mila softens with a sigh. She reaches up and caresses his cheek, and she nods in agreement. She reaches up for his kiss, and he holds her tighter, more securely.

Okay, he thinks.

Dean leaves her to see to his responsibilities, caring for the horses, while Mila goes her own way to resume her daily chores. But when she asks her mother, Misae, and even Eyota if they want to go with her to the river, they say they’re too busy with other tasks to wash clothes. Her mother does give her an extra bundle to do for her though.

So even though it makes her uneasy to go against Dean’s wishes, she carries the bundles by herself to the river. Honestly, she prefers to do this alone sometimes, so she can be alone with her thoughts. Dean’s being overcautious.

Sure, it takes extra effort for her to get down on her knees at the riverbank, considering her protesting back, but she manages to do it. Because in her tribe, one does what they need to in order to live and eat.

She settles into her work after a few minutes, and bit by bit, she feels settled enough to relax. She even hums a little tune to herself. It’s part of a lullaby her mother used to sing to her when she was little, and now Mila sings it for her child, even before she gets to meet him…

Or her, she thinks, smiling to herself.

Her smile drops with a sharp inhale of breath.

She hears hoof falls on the earth. A horse treads nearby.

Slowly, she lowers the wet clothing back into the basin. She sees two reflections growing on the water: a horse and a man. The man gets down from his horse first.

“Hey there, miss—”

Mila swiftly turns and unsheathes the knife she keeps strapped to her ankle.

Dean finally takes the colt out for his first ride out in the open. He’s a little twitchy, but he responds well to Dean’s commands, enough that he chances leading the horse farther out of the village.

Maybe he’ll join Šóta and the rest of the men. They’re likely planting in the fields today, some of the women too, if they’re done at the river. Dean thinks of Mila then, and he hopes she’s finished her work there. He wonders if she got her mother to go with her, or maybe a couple of her friends. They’re new mothers, just a few years older than her.

I’ll just check on them, make sure everything’s on the up and up, Dean thinks. He guides the horse towards the river. He’s relaxed and focused on how the colt is behaving, until he hears a man’s voice on the wind. Dean looks up sharply and sees his wife there alone, crouched down on the riverbank.

A man stands just a few feet away and towers over her.

Dean’s gun is in his hand before he realizes it. With a small but purposeful kick, he urges the colt to a full gallop.

The man seems to be approaching her, taking meaningful steps forward. Mila says something sharply to him as she brandishes her knife and prepares to use it. He stops short.

“Hey!” Dean shouts.

He aims for the dead center of the man’s chest. His hair is long enough to brush his shoulders and obscure his face, but the closer Dean gets, a certain twinge runs up his spine and triggers his senses.

When the man looks up and raises his hands in shocked surrender, it’s like a physical blow to Dean’s chest. The man staring back at him is broad-shouldered, slightly taller than him in his dark brown duster coat, Stetson hat, and boots. He’s scruffier than usual, but unmistakable; he too stares at Dean like he can’t believe his own eyes.

“Dean,” he says, a hint breathless. His gaze drifts from Dean’s face to his pointed gun. He chuckles. “You gonna shoot me?”

Slowly, Dean lowers his weapon. He quickly moves to Mila first and slips an arm around her waist to help her stand with him. He makes sure she’s all right by the silent conversation that passes between them, through their eyes.

Then, he looks over at his brother and smiles, shaking his head in disbelief.

“Hey, Sam,” he says. His gaze roams over the younger man’s face, sporting what he’d call half a beard. “What the hell’s that ferret on your face?”

Sam laughs. It ends with a too-bright smile that’s a little teary. Dean’s throat begins to close up on him a bit as well, but feeling Mila stir at his side, grasping his arm with a questioning look on her face, he gives her a reassuring look.

“Sweetheart, this is my brother. Sam,” he says.

Her eyes widen, but as she looks between the men, her face dawns with understanding. She smiles and releases him, only to guide him towards his brother with a gentle push.

Dean needs no further encouragement. His grin widens as he goes to meet Sam, who’s already coming straight for him. They meet in a warm, solid embrace, even if they’re both still on shaky ground on the inside. Sam’s grip is just as strong and desperate as Dean’s is reassuring, cupping the back of his neck.

“They told me you were dead, you bastard,” Sam says. His laughing words have a suspect shake in them.

“Yeah, my fault,” Dean says. He chuckles too, as if that can make this easier. “Why’d you come all the way out here?”

Sam pulls back after a moment. “Because I didn’t believe them.”

Dean’s smile falls. How the hell is he going to explain this? To Sam, to the Chief and the rest of the tribe…

He notices Sam looking past him, and finally Dean remembers himself. He keeps a hand on Sam’s shoulder and beckons Mila over to them. She’s hesitant, but she trusts him. She goes to him and leans into his side while he wraps his arm around her waist.

“Sammy, this is Mila…my wife,” he says.

Sam brows raise high, his mouth nearly falling open. Dean recognizes the question in his eyes.

You married…an Indian?

Dean just raises his brows.

To his credit, Sam gets ahold of himself and internalizes most of his reaction.

“Ah, right. Nice to meet you…ma’am,” he says, chuckling awkwardly as he extends the offer of his hand. She just looks at his hand curiously.

Sam clears his throat and takes his hand back.

“So, when did—uh, how…”

Dean smiles slightly. He can’t remember the last time he saw his brother this tongue tied; maybe since the time Jessica Moore kissed his cheek when he was nine after he gave her his last juice box.

“Come on,” Dean says, tightening a hand on his shoulder. “I’ve got a lot to tell you before we get back.”

“Get back? Where are we going?” Sam asks.

Dean doesn’t answer him just yet, but he wishes he had brought Mato. He doesn’t trust putting Mila up on the colt, who’s still being broken in, but he doesn’t think she’d feel comfortable riding with Sam. So they walk back together to the village while leading their horses. Dean tells Sam the story of how he and Mila met—the good, the bad, and skimming over most of the ugly. Though he does admit to killing Dick Roman. And Dean admits that he made a choice to help her based on gut instinct alone.

“I knew what I was supposed to do, but…” Dean trails, glancing over at Mila. She’s been holding onto his arm as they make their way up a grassy hill, and now, their eyes meet. “I guess I’m just not the man they wanted me to be.”

She smiles a little at that, squeezing his hand.

Sam watches them together. He’s unable to stop the wonder from crossing his face, along with his smile. But his smile fades.

“You let us believe you were dead, Dean,” he says. Anger creeps into his voice, earning Dean’s sigh.

“It’s not like I could mail you a letter, Sam. It was…easier this way.”

“Easier?” Sam scoffs. “You think it was easy for me? Easy for Mom?”

Dean looks away. This chips open every part of his grief.

“We had a funeral for you,” Sam says. “Not that we had anything to bury.”

“Okay, I get it,” Dean says, rubbing at his eyes. “Maybe easier was the wrong word…safer is. For you, for me, for my wife, and for her people.”

Sam glances at Mila, who stares back at him with reservation in her eyes. She understands his anger, but she’s grateful to Dean. She knew what he’d done to protect her all this time. However, faced with part of the family he let go for her sake, she now feels guilty. So she doesn’t speak as she walks beside Dean.

Sam also stays quiet for a while. The gentle plodding of the horses and their boots on the grassy earth are the only sounds for a while, along with the wind in the distant trees of the forest.

“So, her tribe just…accepted you?” Sam asks.

Dean chuckles, shaking his head. “Well, it hasn’t been that easy.”

“He has worked hard to earn the Chief’s respect, and the respect of everyone in our tribe,” Mila says. It’s the first thing she’s contributed to the conversation, but she feels that this is something that must be said.

Once again, she and Dean share a meaningful glance. He’s going to need all of that respect and goodwill if he’s going to bring Sam to meet the Chief.

Dean is actually glad Šóta is gone on a hunt with most of the other men. Tahatan, Chatan, and Hanska are enough of an audience when he brings Sam to the Chief’s tipi. He and Mila explain why his younger brother came to find him, and Sam fills in the rest of the blanks from his point of view.

Apparently, he and their mother, Mary, received a letter from the U.S. Cavalry that Dean had been killed in the line of duty, but when Sam reached out to military personnel through his law connections, no one could tell him specifically how Dean had died.

So Sam took a train out of Lawrence, Kansas and headed to Wyoming. He travelled the rest of the way on horseback to Fort Laramie. There he requested to speak to Colonel Sanderson, but the only one who would talk to him was Captain Benny Lafitte.

“Captain now, huh?” Dean remarks. He smiles to himself. “Good for him.”

“He’s the one who told me that you had fallen into the canyon…in pursuit,” Sam says, tactfully when he glances at Mila. “But I looked all over that canyon. I never found your body, or your horse. So I just kept looking.”

Dean sighs. He can’t fault Sam for not leaving it alone, because he knew if he’d been in Sam’s shoes, he would’ve been searching all over the state for his little brother too, even if it was just a body to bring back to his mother.

“What if they followed him here?” Chatan speaks up. It reminds Dean that it’s not just him and his brother here. In fact, his father-in-law and the Chief are wearing similar grim looks while they seize up the younger Winchester. To see if he’s a threat to their tribe.

Dean meets his brother with a firmer look. “What did you tell them, Sam?”

“What do you mean?” Sam asks. “They lied to me.”

“Yeah, but what did you say to Benny? To Sanderson. To anyone. Did you tell them you didn’t believe I was dead?” Dean asks.

“No, I didn’t even talk to Sanderson. He couldn’t be bothered with me,” Sam says. “All I told Captain Lafitte was that I was going to find your body.”

Dean breathes out in relief, but the feeling is short lived. Šóta and Otaktay bring in a wounded Takoda into the tent. He’s bleeding and groaning in pain, clutching at his chest with a hand covered in scarlet. Blood drips to the ground where they lay him before Hanska. Tahatan calls for Eyota, the healer. Mila and Dean go to help Takoda.

“What happened?” Tahatan demands to know.

Šóta can’t look his father in the eye at first. He opens his mouth to reply, but Takoda groans in agony. Mila pillows his head in her lap and brushes her half-cousin’s hair from his face. She feels someone’s gaze on her, and she finds that it’s Otaktay. He hasn’t spoken to her since his fight with Dean several weeks ago, and she’s certainly not gone out of her way to speak to him. But there’s no time for awkwardness right now. Takoda writhes in pain while Hanska examines his wound.

Dean recognizes what it is right away. Takoda has been shot twice—once in the shoulder, and once all too close to his heart. Dean looks up at Šóta with furrowed brows.

“These are bullets, not arrows. Where did it happen?” he asks.

“I warned you not to engage the White Men!” Tahatan reproaches angrily. “Now look at what has happened!”

Šóta looks like he wants to bow his head, but he holds stubbornly to his convictions.

“They’re starting to build closer to the village. We were just watching them at first, but we were spotted,” he says.

“You got too close!” Chatan growls.

Eyota arrives with more supplies to help stem the bleeding. Dean is no doctor, but he knows a gunshot wound better than the others do, even Eyota and Hanska. The problem is, they don’t have the tools to get at the second bullet in his chest, and he’s bleeding out fast.

“I gotta dig it out,” Dean tells Šóta in English. He translates to the others. Dean looks down at Takoda and tries to reassure him. “This is gonna hurt like hell, brother. Just hold on.”

Takoda nods. He literally holds onto Dean’s shoulder and pleads without speaking. Help me.

His jaw clenching tight, Dean tries his best to find the bullet with the thinnest utensil Eyota has for him. Takoda attempts to keep still. His writhing is too much though. Even Sam comes to help hold him down. He’s a lawyer, not a doctor, but he knows what Dean is doing is the man’s only chance.

It just takes too long. Dean eventually does find the fat piece of the bullet and pulls it out, but the fight has drained from Takoda along with his life blood. His sweaty chest stills in its movements. His grip on Dean’s shoulder and Šóta’s knee become lax, and then limp.

His dark eyes stare up at the ceiling of the tipi, now unseeing as the light drains out of them.

Takoda. His name meant Friend to Everyone. And so he was.

After Hanska and Eyota clean his body, they dress him in his best clothes and wrap him in robes. Then they bring his body to the highest point near the village, at the top of the grassy hill. Under the night stars, it’s the closest they can bring him to the heavens, where the Lakota believe his soul will ascend to the spirit world. They won’t bury him in the ground, but instead will give him an “air burial” for a warrior’s death.

When a member of the tribe dies, usually the night is spent telling stories, laughing at old jokes, and food passed around. But this isn’t a night for joke-telling. The whole tribe is gathered in mourning at the foot of the hill.

Tahatan sings a somber song for his second son, and his voice rises high over his second wife’s wails. She kneels beside her son and cuts her long hair jagged with a knife while she weeps. Mila grieves more quietly, but she tells Sam and Dean that hair cutting is part of the custom, and even cutting at their own bodies if their grief is that great.

Eventually, the tribe disperses for the night. Tahatan leads his wife away, but Šóta and Otaktay stay with his body. They will sit in a vigil with him all night.

Meanwhile, Mila and Dean take Sam to their tent. She finds bedding and furs for Sam to sleep on, and Dean helps her lay it all out.

“Thank you,” Sam says to her sincerely.

She offers him a small smile, then she prepares to sleep herself. Dean stops her by taking her hand. He leads her into a comforting embrace. She lets out a shaky breath as her fingers curl into his clothing.

“I’m sorry…I couldn’t save him,” Dean confesses quietly.

Mila shakes her head. “It was not your fault.”

In her mind, she can’t help but put that blame on Šóta. It hurts to have that anger in her heart, but it’s there, no matter how hard she tries to let go of it. She clings harder to Dean, pressing her face into his chest while her body shakes with silent sobs. He caresses her hair, kisses the top of her head, and then her cheek.

After a little while, she pulls away from him and rests a grateful hand over his heart, before she goes to bed. Dean helps her settle down on the ground and pulls the fur blanket over her form. He squeezes her shoulder one more time before he joins Sam on the other side of the room.

All the while, his younger brother has been watching him, admiring the way he’s always been a protector, but also a man who takes care of the people around him. Sam remembers it well, when they were kids.

Dean gives him some bison jerky to snack on, and for a few minutes they eat in silence while a small fire burns in the coals piled in front of them.

“You’re all in danger here, Dean,” Sam says, breaking the silence. “It’s only a matter of time before the Army finds this place.”

Dean nods slowly. “I’ve been trying to convince the Chief to move the tribe up north. Other Sioux tribes have been able to settle there, but more and more, they’re being forced out of their land.”

Sam considers that with a slow nod. A grim realization dawns in his eyes.

“It’s not fair,” he eventually agrees. He falls into his thoughts for a moment, trying to decide how to say what he wants to. “You should come home, Dean. Come back with me.”

Dean sighs. He knew this was coming. It might as well be now. He glances over at Mila, who finally seems like she’s sleeping peacefully. He rests an elbow above his knee and looks back at his brother.

“You’re asking me to leave my wife?” he asks. “She’s pregnant, Sam.”

Sam’s eyes widen. That news probably shouldn’t have surprised him as much as it did, but he’s a little hurt that Dean would think he’d suggest leaving her.

“No, Dean, of course not,” he says. His frown fades, turning into a smile. “Congratulations.”

Dean lightens, his lips curving slightly into a smile as well. He nods in thanks.

Sam sighs. “Look…ask her to come with you. With us. You can live out with Mom on the farm and raise your kids there.”

“You forget that I’m supposed to be dead? Hell, for God’s sake, you already had my funeral to prove it.” Dean rubs tiredly at his face. “Lawrence is a small town, and Mom has, what, fifteen, twenty people working that farm? Word’s gonna get out, one way or another. If the Army hears it, I’ll be court martialed for desertion, not to mention all the rest of it.”

Sam opens his mouth to argue back with that earnest, determined look in his eyes. Dean expects nothing less. It’s what makes his brother a good lawyer, but Dean raises up a hand against whatever he’s going to say. Again, he glances back at Mila.

“Sam…this is what she knows. These are her people, her family,” he says. After a hesitant pause, he adds, “They’ve become my family too.”

Sam’s jaw clenches. He glances down at the ground between his feet, before he’s able to meet Dean’s eyes again. There’s hurt and anger in his own.

“And me?” he asks. “What, I’m not your family anymore?”

He doesn’t know just how deeply that hurts Dean. He shakes his head, drops his jerky into the dirt. He reaches out and grasps Sam’s shoulder.

“Sammy,” Dean says. For a moment, he can’t speak. His throat constricts, and no matter how tight he presses his lips together, he can’t stop the slight tremble in them. “You don’t know how hard it’s been…to convince myself that I wasn’t ever gonna see you again. But I’m happy. I’m so fucking happy that you found me.”

Dean tries and fails to blink past the way his eyes burn with tears. Sam’s eyes are getting just as red and shiny. He lays a heavy hand on Dean’s knee, and they sit like that for a while in silence, until the embers on the coals dim from red to black.

Šóta hasn’t slept. It’s evident in his red-rimmed eyes and unkempt, dirty clothes, but he’s still adamant about hitting back against the railroad construction.

“Father, they stand at our doorstep!” he argues to the Chief. “They take our horses, run off our wild game with their machines, cut down the forest, and now they build iron tracks through our lands. You went to war against the Crow for less!”

Tahatan seems heavy in his thoughts as he listens. The words of his eldest son, and from his first wife, have weight—not just with him, but with the entire tribe as they sit together in the place where they typically have group feasts. Otaktay stands behind Šóta in support.

Dean is reluctant to single himself out, but after sharing a look with Mila, he stands.

“Chief, what happened yesterday was more than just a tragedy or a crime. It’s a warning,” he says. “We need to leave, before the Army finds this village.”

“You suggest we run like cowards,” Otaktay says. His tone is icy and angry.

Dean shakes his head. “I’m not doubting your courage or your skill. I’m not doubting any warrior here. But this ain’t a fair fight.”

He shifts his gaze, addressing Tahatan directly.

“We’re out-manned and out-gunned, literally. Arrows and knives against bullets—pistols and rifles,” Dean says. “They’ll tear through this village until there’s no one and nothing left. We have to go north. It’s the only way we’ll survive.”

Chatan sides with Dean, and Mila stands with him too.

Tahatan thinks hard. After a long, silent moment, he stands from his chair of whicker and wood.

“We will pack the caravans today and move out tonight,” he says.

Then he commands Šóta and Dean to start preparing the horses. Šóta shoots Dean a hard, angry look, but Mila steps in and pushes at her cousin’s arm.

“Don’t look at him,” she warns tersely in their language. “This is the cost of what you have done.”

Šóta is affronted by her words, but he doesn’t answer her. He just turns away with a sharp pivot on his heel. Otaktay glances back at Mila and Dean impassively, but he follows after Šóta, his friend and his leader.

Dean understands what she said; he’s spent enough time here that he’s able to follow every word. He gives her a look that’s mostly resigned, but he holds her to his side in comfort. He knows this isn’t easy for her either.

“I will start packing,” she says.

Dean nods. “I’ll come help you in a bit.”

He watches her leave his side to make her way back to their tent. Sam approaches him, and together they walk to the horse pen, where his horse is grazing with the others under the great sycamore tree that shields them.

“We’re leaving tonight,” Dean says. “You should head home.”

“What if something happens to you on the road?” Sam says.

Dean smiles ruefully. “I could say the same thing to you…but it looks like you don’t need me to protect you anymore.”

“Yeah well, doesn’t mean I won’t always need my brother.”

They share a smile, followed by a strong embrace. Dean thumps his back.

“Take care of yourself, Sammy,” he says, a coarse whisper.

Sam chuckles weakly. “You’ve got a harder road than I do.”

“Hey, you’re the one who’s gonna have to face Mom.”

Dean says it as something of a joke, but all it does is sober both of them. Sam pulls away reluctantly.

“I’m not going to get to meet my niece or nephew,” he says.

“I’m sorry about that too,” Dean says, meeting his brother’s glassy eyes. “I’m sorry about a lot of things.”

Sam jaw clenches, and he shakes his head. “Don’t do that.”

Another beat passes between them. He clears his throat.

“I’ll tell Mom…”

“Take care of her,” Dean says.

Sam nods his agreement. Dean finally releases his brother’s shoulder, and there below the sycamore tree, the brothers part ways. Sam straps up his provisions and climbs up on his horse. Dean opens the pen for him, long enough for Sam to ride through.

He stops at the foot of the hill and looks over his shoulder at Dean, who gives him one more lax salute. Sam smiles, nodding back at him. Then he keeps riding.

Dean watches him cross the grassy plain until it becomes too hard to look straight into the afternoon sun. Distantly he hears Šóta’s voice behind him, giving out orders to other men. Dean looks away from the sun.

He has work to do.

He locks up the rest of his grief to begin with the horses, not knowing that Otaktay watches him.

Dean doesn’t want to load up Baby with too much cargo. She’s still early in her pregnancy, and he could even ride her if he wanted to, but he can’t help but want to protect her more. It’s going to take days to move the tribe across the state, maybe longer. So instead, she can help pull one of the caravans with the colt and a couple of the other horses.

He saddles up Mato to ride. Hopefully he actually cooperates with Dean this time.

Mato begins to stamp nervously though, like he senses something coming. Dean perks up and notices the way the horse’s ears flick back and forth. Baby makes an anxious sound as well. Dean turns his head in the direction of the village with furrowed brows.

Šóta draws near to find his horse, who’s just as unsettled as the rest of them.

“The horses are spooked,” he says.

“Something’s wrong,” Dean nods in agreement. His gut tells him so, while a spark of unease licks up his spine.

And then he hears it. A warning blow of a buffalo horn on the air, followed by screaming, shouting, and gunfire in the village down below. His eyes widen.

Mila.

AN: 😬 Sorry about the cliffhanger, but we're almost to the end! What did you think of Sam's big entrance into the story? 😉

Coming up, the grand finale...

Next Time:

Gritting his teeth, Dean brings Mato to a short stop in front of the Chief. Dean aims his gun at the Colonel. By now, the man is clutching his bleeding shoulder and staring at his former captain in disbelief. Benny is maybe a little less shocked to see Dean, but there’s conflict in his eyes—happiness mixed with turmoil.

The other officer is Jack Kline. He recognizes Dean too, with wide eyes and a gaping mouth.

“You…” Sanderson trails. He blinks, his brows furrowing. “Dean Winchester.”

Pronunciation Guide:

Wašíču ("wash-ee-jew") Šóta ("sho-tah") Chatan ("chat-tan") Tahatan ("ta-hat-tann") Otaktay ("ogh-tac-tay") Weaya ("we-ayy-ya") Takoda ("ta-koda") Mato ("matt-toe") Misae ("mee-sah-eh")

▶️ Keep Reading: PART 4 (Finale!)

Join My Patreon 🌟 Get early access to new stories, bonus content, and first looks at upcoming stories, send me requests, and more!

Outlander Masterlist

The Honorable Choice Masterlist

Jacklesverse Bingo Masterlist

Dean Winchester Series List

Dean Winchester Masterlist

Main Masterlist

Series Tag List (Part 1)

@hobby27 @kazsrm67 @jacklesbrainworms @foxyjwls007 @mostlymarvelgirl

@thebiggerbear @roseblue373 @this-is-me19 @emily-winchester @deans-spinster-witch

@deans-baby-momma @sanscas @kaleldobrev @spnwoman @samanddeaninatrenchcoat

@globetrotter28 @adoringanakin @midnightmadwoman @chevroletdean @iprobablyshipit91

@chriszgirl92 @lyarr24 @ladysparkles78 @spnfamily-j2 @pieandmonsters

@deansbbyx @sarahgracej @chernayawidow @mimaria420 @stoneyggirl2

@fics-pics-andotherthings-i-like @waywardxwords @waynes-multiverse @twinkleinadiamondsky @mxltifxnd0m

@my-stories-vault @kayleighwinchester @rizlowwritessortof @samslvrgirl @tortureddarkstar

@tmb510 @syrma-sensei @artemys-ackles @malindacath @mrsjenniferwinchester

@jc-winchester @charmed-asylum @fromcaintodean @k-slla

#A Warrior's Death#Outlander#Part 3#Jacklesversebingo24#The Honorable Choice#dean winchester#dean winchester angst#dean winchester x oc#supernatural#spn#dean winchester fanfiction#dean x oc#dean winchester imagine#dean winchester smut#dean winchester fanfic#supernatural fanfiction#spn fanfic#jensen ackles#jensen ackles x oc#jensen ackles fanfiction#jackles#dean winchester au#western au#dean au#dean winchester x original character#sam and dean#dean winchester x ofc#benny lafitte#sam winchester#zepskies writes

100 notes

·

View notes