#Katorga Works

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Merchandise - (Strange Songs) in the Dark, (Drugged Conscience & Katorga Works, 2010)

#merchandise#werchandise#carson cox#d. vassalotti#katorga works#drugged conscience#punk#post punk#noise

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Inner Peace by Lotus Fucker

“I found inner peace when I began again.” Happy New Year

1 note

·

View note

Text

Warhog - Potential / Yes, Master (Exterminate Me EP, 2014)

1 note

·

View note

Text

# 4,281

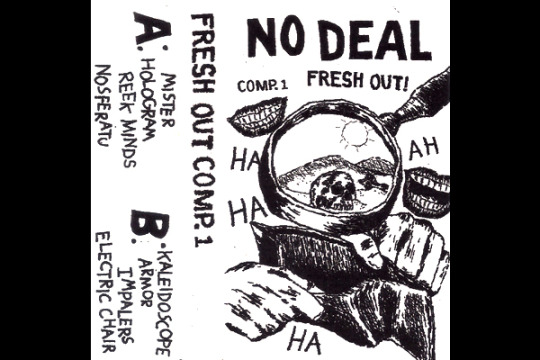

Various artists: No Deal Fresh Out Comp. 1 (2020)

Here's proof that you can find music goldmines through online video channels. No Deal has to be from New York City or somewhere else in the tri-state area judging where he's put together shows (Brooklyn's Saint Vitus for one). He's one of the messengers of the current punk / d-beat / thrash scene who posts all of his favorite finds, demos-, and records on YouTube. So far the count's up to 250+, but I'll be damned if he's not sharing the wealth (or poverty?) by throwing some of the best decrepit, broke-as-shit, trash-stricken punk out there. As a tribute, here was the first of two cassette compilations up for sale through Bandcamp (165 copies maximum) with free digital downloads up for grabs. Some contributions are freshly-baked and muffled (Mister's "Sucio") while others are a warbly disastrous mess (Hologram's "Nothing" or Nosferatu's untitled track) but that's the ethos of it all. There's also Kaleidoscope (Katorga Works), Impalers (featuring Mike Sharp) and Armor (crosshair demon); three bands Omega WUSB has featured previously on our show over the years. Go seek this out to see how No Deal had gotten right what short, last, loud, and angry means.

#punk#d-beat#thrash#Mister#Hologram#Nosferatu#Kaleidoscope#Katorga Works#Impalers#Mike Sharp#Armor#omega#music#mixtapes#reviews#playlists

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🖌️: Shiva Addanki

1 note

·

View note

Audio

Wiccans- Biology Is Not Destiny

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi love, hope you're well! i was wondering if you have any recs for slow burn or hurt/comfort type of fics? appreciate your work and hope you stay safe <3 -n

Hello dear n! I was steadily working on this whenever I have free time but this still took a long time. Thank you for patiently waiting.

A lot of fics I recommended under personal favorites actually fit your request. But here are some more fics (limited at 1 fic per author but check out their other works too!) tagged slow burn and/or hurt/comfort I rec:

All Our Yesterdays by @kitsunebi-uk [E, 1M]

York, England, 2120: Yuuri Katsuki is a dime-a-dozen techie, spending his days doing routine repairs at the university. He hangs out with his friend Phichit, goes for a drink, watches holograms. It’s an existence – but is it a life?

Crowood Castle, Yorkshire, 1392: As the son of a baron, Sir Victor Nikiforov makes judgements where lives hang in the balance. As a knight, he must sometimes end them. It’s what he was born to do – but what of the heavy burden on his soul? Death is all too commonplace, while life and love remain elusive.

When a brilliant scientist goes rogue, journeying to the Middle Ages with the world’s first time machine, Yuuri is stunned to be called on as the last hope of preventing her from changing history. After an abrupt departure, he lands at Crowood Castle disguised as an enemy of the Nikiforovs, Sir Justin le Savage – and will need to act the part if he is to survive. It’s a tall order for someone who can barely tell the back end of a horse from the front. But if Ailis, in her own disguise, discovers who he is, his mission will end in a blaze of laser-gun fire. He must not give his real identity away, even to the beguiling knight he’s falling in love with…

Beside the Dancing Sea by lily_winterwood / @omgkatsudonplease [E, ?] *Being edited and reuploaded

He’s finally here in this lovely and quiet little beach cottage, and the rest of the year seems to stretch out infinitely before him. Time will pass, though, and it will pass faster than he realises, but in the meantime he will stop worrying about writer’s block and deadlines and not even having the foggiest clue what his next novel’s going to be about, and live.

New York Times-bestselling author Viktor Nikiforov arrives in the sleepy seaside town of Torvill Cove to cure his writer's block. After encountering local wallflower Yuuri Katsuki at a party, he discovers that this mysterious dark-haired man has a couple secrets up his sleeve.

And Viktor will be damned if he doesn't find out just what those secrets are.

Dot, Dash, Star* by saltwreath [T, 29K]

People with soulmates were blessed with lights like stars. Viktor Nikiforov was born without one, Katsuki Yuuri would have two, and Yuri Plisetsky pretended he had none.

They find each other anyway.

it's the side effects that save us by renaissance [T 71K]

After a sudden personal tragedy and a narrow defeat at the Grand Prix Final, Viktor is ready to throw it all away—until he sees a video of the skater who beat him performing the free skate he couldn't.

Or; plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose...

Love in Exile by @martymusesloveinexile [E, 99K]

Once a well know ballet dancer in St. Petersburg, Victor Nikiforov finds himself exiled to Sakhalin Island as a political convict in 1881. As a man sentenced to katorga he will never return to European Russia or his life on the stage. Known as the "Edge of the World," his life on Sakhalin could not be further from the life he once knew. Strange circumstances lead his path to cross that of a young Japanese man, one of the very few still living on the island. Katsuki Yuuri leads a life of exile of a different kind, one that is largely self-imposed. Drawn to each other, despite their differences, something slowly begins to grow between them. When a narrowly avoided tragedy leaves them stranded together for a long, cold Sakhalin winter, they are challenged to face what their relationship really means, and what future it could possibly have.

My Name On Your Lips by feelslikefire [E, 108K]

Yuuri Katsuki has been betrothed to the High King's son, Victor, since he was just a child; furthermore, as an omega, he's forbidden from practicing magic in combat. For years, he's been able to put off the former because the Prince was traveling abroad, and gotten around the latter by practicing with his mentor in secret.

Now Victor Nikiforov has finally returned home, and Yuuri is being summoned to the capital for their wedding. He needs a plan to put off marriage long enough to find a way to break the betrothal, while keeping his practicing from being discovered.

If only the Prince didn't have other ideas.

The Noblest Form of Affection by @lucycamui [E, 38K]

The duty of a valet appears deceptively simple on the surface: his sole job is to wait upon his master. Yuuri prides himself on his skills as a valet, but will the challenges and heartaches that come hand in hand with serving the lovely and eccentric Mister Nikiforov prove to be too great a hurdle?

Nuclear Hearts Club by butterbeerbitch / @the-tortellini-man [T, 84K]

He remembers his sister made being seventeen look like life was happening harder than it ever did. All those big, brutal feelings.

And he’s here now, and it's untangling in a pace too fast for him to hold onto anything. Something's starting and something's ending, and it makes sense until it doesn't, and he's stuck somewhere in the middle thinking it won't ever stop feeling like this.

All this changing in a town where nothing ever does.

-

Being seventeen in the middle of nowhere isn't supposed to be a walk in the park. Add being crazy in love with your brother's best friend to the equation, and it’s safe to say you’re cosmically fucked for life.

Good thing Yuuri Katsuki's not used to having nice things.

Rivals series by Reiya / @kazliin [E, 452K]

An altered universe where a single event changes the course of both Yuuri and Viktor's lives, a rivalry is formed that spans across many years and both of them tell a very different side to the story

same song, different dance by @crossroadswrite [T, 88K] *WIP

The line is silent for a moment, as Yuuri stands there, fingers getting progressively colder as he hears Minako breathe in his ear, not really willing to hang up first.

“The Grand Prix is just around the corner,” Minako says, her tone almost wistful.

He breathes out slowly to steady himself. “It is.”

“… Are you going to watch it?”

Yuuri shouldn’t. He knows it’ll feel awful to watch everyone he knows trying their best at something he loves when he can’t anymore. But it’s Phichit’s first year in the Grand Prix, and Victor’s competing, so…

“Of course,” he says, and is proud of how steady his voice comes out. He doesn’t know if it’s a lie or not.

(Or: in which Yuuri's Stammi Vicino skate never gets posted and he retires, Victor keeps himself skating for better or for worse, Yuri struggles with his debut, and missed opportunities have a way of righting themselves.)

Tadaima by @stammiviktor [T, 12K]

After decades of wandering, Viktor finds a home in the Katsuki family.

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wilk’s father(mainly appearance) is based on exiled Polish anthropologist Bronisław Piłsudski.

The clothes especially are based on Bronisław Piłsudski’s portrait by Adomas Varnas(1912)

Wilk himself would be older than the real Pilsudski who would be the same age as Kiroranke(b. 1866).

Pilsudski was a law student and member of the extremist group Narodnaya Volya who participated in the “Second First of March” where they attempted to assassinate Tsar Alexander III(son of the Tsar Wilk assassinated) but failed. Pilsudski was the only one of the group not executed but was instead sent to Katorga(hard labour) in the Sakhalin penal colony in 1887.

There, Pilsudski studied and interacted with the Karfuto Ainu, Nivkh, Orok and later even went to Hokkaido and worked with the Hokkaido Ainu. In 1902, he married a Karafuto Ainu woman, Chuhsamma[チュフサンマ], with whom he had two children- a son and daughter. This is once again similar to Kiroranke who has two infant sons and he seems to have married more recently some time before the war(1904-1905) maybe 1902.

Having to leave behind his family including his infant children he took an opportunity to flee illegally to his native Poland around the time after the Russo-Japanese War and he died in Europe without ever seeing them again.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite historical AUs

Blackbird. The year is 1942, and Europe is at war. Captain Victor Nikiforov, an intelligence operative for the NKVD, has been trapped in Berlin by the German invasion of the USSR. Posing as a Nazi industrialist, his days are spent charming information out of Axis diplomats to try and keep the Red Army fighting another day.

Yuuri Katsuki, a foreign-educated bureaucrat in the Japanese Embassy, has secrets of his own concealed beneath his unremarkable demeanour. When he uncovers Victor’s real identity, it will alter the course of both of their lives forever.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/9651944/chapters/21806939

Love in Exile. Once a well know ballet dancer in St. Petersburg, Victor Nikiforov finds himself exiled to Sakhalin Island as a political convict in 1881. As a man sentenced to katorga he will never return to European Russia or his life on the stage. Known as the "Edge of the World," his life on Sakhalin could not be further from the life he once knew. Strange circumstances lead his path to cross that of a young Japanese man, one of the very few still living on the island. Katsuki Yuuri leads a life of exile of a different kind, one that is largely self-imposed. Drawn to each other, despite their differences, something slowly begins to grow between them. When a narrowly avoided tragedy leaves them stranded together for a long, cold Sakhalin winter, they are challenged to face what their relationship really means, and what future it could possibly have.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/9327392/chapters/21135641

the fall of this empire will be loud. In 1991, the Soviet Union collapses. In 1989, the Berlin wall falls. In 1987, Viktor Nikiforov, iconic figure skater and darling of the USSR, defects to the United States. In 1986, Yuuri Katsuki falls in love.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/10450485/chapters/23069037

The Stars, the Moon, and a Soul to Guide Us. When Yuuri was born, the priestess was struck with a vision, a picture they could not explain. As he comes of age, they realise what he is - the carrier of a gift, admired by some, but feared and mistrusted by most.

But when his future is decided for him and his life put in the hands of a stranger through marriage, Yuuri knows that he has no choice. That whatever the gods have planned for him must come true.

As it was foretold.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/21300893/chapters/50723870?view_adult=true

moods, states of grace, & elegies. Victor Nikiforov has traveled far and wide in the company of trader Christophe Giacometti on the silk roads to arrive at Hasetsu, capital of the Great Nihon Empire. He expects to stay a winter, until the seasons change again, and fairer weather and the changing of seasons can return him to his wanderlust.He does not expect to fall in love with the Crown Prince.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/14632119/chapters/33817776#workskin

Zanka. Aoyagi's lips parted in a sigh, and for a brief second, Viktor saw a wistful expression beneath the fine-edged veneer – fleeting and transient as a cherry blossom in bloom. There was so much unspoken that Viktor wanted, now more than ever, to take the man with him. Bring him home and far away from this glittering world of luxury and waste.

Victuuri historical AU in 1800s, Edo, Japan. Yuuri is Aoyagi, a high-ranking male courtesan, and Viktor falls hopelessly in love.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/11542329/chapters/25917123

The Lily of Kasagiya. Yuuri, following his love of beautiful things, would have gone to any lengths to become the finest geisha in the world. Then he met Victor Nikiforov.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/11467587

croisés, écartés, entrelacés. St. Petersburg, the early 1900s. Yuuri has left everything behind to follow his dream and Victor is the city’s darling. Both danseurs at Mariinsky theatre, their paths continually intertwine as they are fated to meet again and again. However, as love blooms, looming shadows of war lie in wait.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/12534796/chapters/28544700

Interpersonal Diplomacy. For the sake of ending a centennial war and protecting the lives of his family and people, Prince Imperial Yuuri of Shanjia makes an unexpected sacrifice, placing his life in the hands of King Viktor of Nova. For the survival of their nations' fledgling peace, Yuuri must live on Novan soil alone, surrounded by people his nation just recently considered enemies, and tied to their monarch by the bonds of diplomacy.

However, Yuuri will also find allies, individuals willing to welcome the peace-loving regardless of past history. If Yuuri is to carve a home in this foreign nation, he must earn the trust of the war-weary Novan people.

And in time, Yuuri may find himself drawing closer to the sympathetic but enigmatic King Viktor.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/16072742/chapters/37529747

in my head, in my heart, in my soul. Drawn into a conflict outside of his responsibility, Victor Nikiforov, the greatest general of the age, appears to have met his match in the shy Prince of Japan who surrenders on the fields of Goryeo.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/15994100

for your sake I hope heaven and hell. Mr. Nikiforov, Duke of Cumberland, first meets Mr. Katsuki, assistant steward to the Giacometti Estate, in Kent.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/23587234

Chorus in Aurorae. When Minako, the sightseer of the Elk clan, tells Yuuri of her vision, he doesn't know what to make of it. But he knows it must be important.

Once she returns from her travels, he learns that another seer from another great clan has shared her vision, and that this can only mean one thing: their clans are to be united, and Yuuri is to be part of it.

He is to bond with a hunter of the Bear clan.

While frustrated that he is being thrust onto a path so very different from the life he had envisioned for himself, Yuuri is made to accept that this union is the will of the spirits. He will go through with it for the sake of the people he loves, even if it means giving up every last part of himself.

To make matters worse, his mate-to-be is the most renowned hunter the winter lands have ever seen, and someone Yuuri has admired for a long time.However, from the moment they meet, Yuuri slowly realises that there is much more to Victor than he has imagined, and that perhaps the will of the spirits is more closely aligned with his own than he previously thought...

https://archiveofourown.org/works/13707318/chapters/31487046

Victor the Great. At the age of nine Victor became the Tsar of all the Russias with Lilia as regent. One day he will be the sole ruler of Russia, the man who makes all the decisions and gets to do what he wants, with one exception: he has to marry a woman from a Russian aristocratic family. Except that he falls in love with a boy who is a foreign commoner. Will he risk the throne to be able to marry the one he loves?

https://archiveofourown.org/works/12740541/chapters/29055912

Pulses that beat double. Katsuki Yuuri traveled all the way from Japan to study medicine in London, but finds himself very short on funds. He's long had a fascination with the scandalous Baron Viktor Nikiforov, so he's shocked when the baron takes an interest in him. So shocked he runs away as quickly as possible. But Viktor Nikiforov is a persistent man when he sees something he wants.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/12210117/chapters/27730044

Gore and Glory. It is the year 1903. In an attempt of de-escalating matters with Imperial Russia, translator Yuuri Katsuki accompanies his father to St. Petersburg in a diplomatic mission. However, he certainly did not expect to meet a man as stunning and peculiar as tsarevich Yuri Georgieviech's bodyguard, Polkovnik Viktor Ivanovich Nikiforov - and even less he expected to fall in love when war is threatening the country.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/10485105/chapters/23131323

#Yuri on ice#YOI#yuuri katsuki#yuri katsuki#Viktor Nikiforov#victor nikiforov#viktor x yuuri#yuuri x victor#yoi fanfic#yoi fic#yoi aus#viktuuri#victuuri

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dmitry decidedly NEVER talks about politics when he’s in Paris. It doesn’t matter whether it’s with the Dowager Empress, Anya, or Vlad, he doesn’t talk about politics when he and Anya visit. While Dmitry doesn’t really define himself with a political label, he is more ANARCHIST than he is anything else. He takes after his father, believes in the work that his father did and spoke about even if it is just a distant memory.

In no universe could Dmitry ever bring himself to be a Bolshevik. He HATES everything they’ve done to Russia. On the other hand, he could never see himself as imperialist either, as much as he loves Anya and respects her past. The tsar was undoubtedly corrupt in many ways, but this is more personal than anything, because the tsar is the man who indirectly killed his father. Nikolai Sudayev was a known anarchist sent to a katorga by the tsar, where he eventually died. Dmitry remembers the day that his father was taken from them vividly-- he remembers reaching out one last time for his father’s hand, for the sleeve on his coat, for anything that he could grab hold of to anchor his father on the spot before he disappeared forever. He remembers the reassuring facade his father put up when he was taken away and the smell of burning propaganda the days prior to his arrest.

Dmitry was a boy then. He held on to hope that his father would return soon alive after a few years in the labour camps, that he would find him one day and run into his embrace. But that never happened. It took him years before he finally succumbed to the assumption that his father died, but even then, he can’t deny that he would still check the faces of tall, dark-haired men for a semblance to the man who raised him. He was thirteen when he met a man who had returned after serving his five year sentence in a kartoga, Aleksandr Ivanov, who told him that he knew his father and that he DIED for what he believed in.

Dmitry doesn’t blame Anya for what her father did. After all, they were just children. To him, she isn’t just the daughter of the tsar either, she is so much more than that. She is hope, she is both freedom and home at once, and she sees HIM beyond all politics and status. However, he does have a hard time reconciling with the idea of Nicholas being a good man when he hears her fond memories and her grandmother’s stories because his vision of the tsar will always be tainted with his father’s death. This, however, goes UNMENTIONED to her and her family. For now, it’s just easier to nod understandingly than divulge the painful memory that will certainly end in guilt ( from both parties certainly ), even if it does hurt a little to be surrounded by the hierarchy that killed his father. But he can’t say he doesn’t breathe a little easier when he and Anya finally leave each visit.

#✦✧ biggest con in history ↣ headcanons.#[ aleksandr as in aleksandr solzhenitsyn ?? absolutely. ]#[ this should be talked about more ]#[ like this doesn't deter his love for anya but it certainly makes things complicated sometimes ]#✦✧ no time to spare ↣ q.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weed Hounds / Double Life [Bandcamp, Cassette, Digital Release]

Weed Hounds / Double Life [Bandcamp, Cassette, Digital Release]

//bandcamp.com/EmbeddedPlayer/v=2/album=69616691/size=large/bgcol=ffffff/linkcol=0687f5/minimal=true/ Band Name: Weed Hounds Label: Don Giovanni Records Release Date: October 5, 2017 Tags: alternative, brooklyn, cassette, indie pop, indie rock, jungly pop, new york, noise pop, punk, shoegaze Links: Website, Bandcamp, SoundCloud

View On WordPress

#bandcamp#Don Giovanni Records#Iron Pier Records#Katorga Works#National Archive Of Records#Stupid Bag Records#Weed Hounds

0 notes

Photo

Real-deal punk from the Katorga Works label. Sara Abruna’s vocals are really to die on a sword / hill for.

📷: Jesse Riggins.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Merchandise - ‘Become What You Are’

0 notes

Photo

OMG HAHAHAHAHA Their first kiss is straight out of a fanfic - the evil overseers don’t believe their marriage is real so they make them prove it by kissing. AHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHHAHAHAHAHAHAH!!!! Maybe ask them to have sex next pls?

P.S. That’s some serious enthusiasm, countess x convict OTP!!!!!!

P.P.S. I want to buy the chief overseer a shirt. Staring at his chest does nothing for me.

P.P.P.S. For being sent to katorga (I can’t think of an english equivalent to the Russian word, sorry), work seems to take a decidedly second place to toiling....

8 notes

·

View notes