#Jules Furthman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Watching

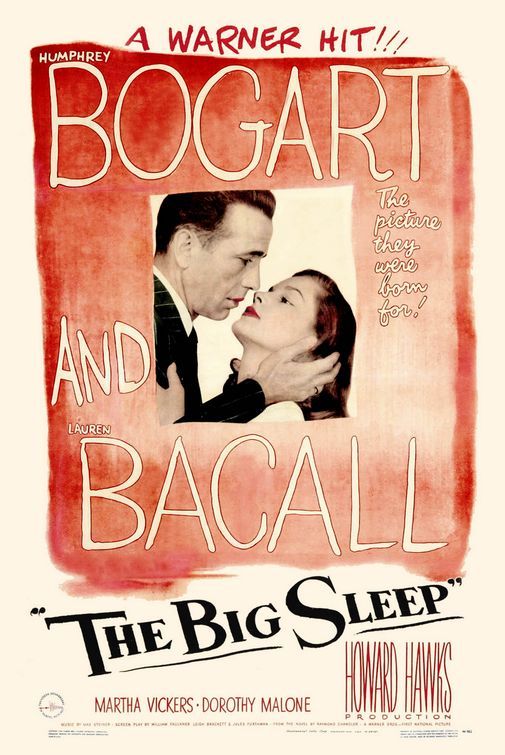

THE BIG SLEEP Howard Hawks USA, 1946

#watching#Howard Hawks#Humphrey Bogart#Lauren Bacall#Martha Vickers#William Faulkner#Leigh Brackett#Jules Furthman#Raymond Chandler#1946#Philip Marlowe

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Big Sleep (1946) Review

When private investigator Philip Marlowe is hired by a general from a wealthy family to try and find out why his daughter Carmen is being blackmailed and with the help of Vivian another of the generals daughters he is taken into a rather complex web of love triangles, murder, gambling and organised crime. ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#1946#Bob Steele#Crime#Dorothy Malone#Elisha Cook Jr.#Film-Noir#Howard Hawks#Humphrey Bogart#John Ridgely#Joy Barlow#Jules Furthman#Lauren Bacall#Leigh Brackett#Louis Jean Heydt#Martha Vickers#Max Barwyn#Mystery#Peggy Knudsen#Regis Toomey#Review#The Big Sleep#Trevor Bardette#William Faulkner

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'To Have and Have Not' – Bogie and Bacall meet on Max

Humphrey Bogart was 45-year-old acting veteran only a few years into leading man stardom and Lauren Bacall a 19-year-old model with no acting experience when director Howard Hawks paired them To Have and Have Not (1944). They sizzle from their first shared scene, the flinty loner and the sexy tough girl who burns her presence into the screen in her film debut. Legend has it that Hawks boasted to…

#1944#Blu-ray#Dolores Moran#DVD#Ernest Hemingway#Hoagy Carmichael#Howard Hawks#Humphrey Bogart#Jules Furthman#Lauren Bacall#Marcel Dalio#Max#Sheldon Leonard#To Have and Have Not#VOD#Walter Brennan#William Faulkner

0 notes

Text

#25: The Big Sleep (1946, dir. by Howard Hawks)

#the big sleep#movies of 2024#movie poster#howard hawks#william faulkner#leigh brackett#jules furthman#female screenwriters#women screenwriters#big movie marathon

0 notes

Text

'Rio Bravo' Movie and 4K Review

The following review was written by Ultimate Rabbit correspondent, Tony Farinella. When you think of the western genre in cinema, it’s hard not to think of John Wayne. Perhaps the only other actor who might be synonymous with westerns is Clint Eastwood, but he would frequently venture into other genres to expand his repertoire. For the most part, John Wayne lived and breathed westerns. When you…

View On WordPress

#1950&039;s Movies#1959 Movies#4K#4K UHD#4K Ultra HD#Angie Dickinson#Armada Productions#B. H. McCampbell#Book To Film#Classic Movies#Claude Akins#Dean Martin#Estelita Rodriguez#Howard Hawks#John Carpenter#John Russell#John Wayne#Jules Furthman#Leigh Brackett#Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez#Richard Schickel#Ricky Nelson#Rio Bravo#Walter Brennan#Ward Bond#Warner Brothers#WB100#Western#Westerns

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Big Sleep (Michael Winner, 1978)

Cast: Robert Mitchum, Sarah Miles, Richard Boone, Candy Clark, Joan Collins, Edward Fox, John Mills, James Stewart, Oliver Reed, Harry Andrews, Colin Blakely, Richard Todd. Screenplay: Michael Winner, based on a novel by Raymond Chandler. Cinematography: Robert Paynter. Production design: Harry Pottle. Film editing: Frederick Wilson. Music: Jerry Fielding.

Just don't. At least not unless you've seen Howard Hawks's 1946 version of Raymond Chandler's novel, which is set, as it should be, in Los Angeles. The shift of the action to London is disastrous, necessitating some lame exposition about why Philip Marlowe and the Sternwood clan are in England. Chandler's plot remains as enigmatic as ever, but in the hands of Hawks and screenwriters Jules Furthman, Leigh Brackett, and William Faulkner, we didn't much care whodunit and why. Michael Winner's screenplay just leaves us with a muddle that has no redeeming flavor and texture. Seldom has a cast of superbly accomplished actors been so sadly wasted as they are here under Winner's direction.

#The Big Sleep#Michael Winner#Robert Mitchum#Sarah Miles#Richard Boone#Candy Clark#Joan Collins#Edward Fox#John Mills#James Stewart#Oliver Reed

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Dorado (1966)

Pulp science fiction writer Leigh Brackett was an anomaly in the genre. Not only was she a woman, but she also crossed over into Hollywood sporadically. Alongside her novellas and serialized stories, her film credits are enviable: The Big Sleep (1946; okay, this film’s story never made sense, but its romantic dialogue is legendary), Rio Bravo (1959), and, posthumously, The Empire Strikes Back (1980). To Brackett, she deemed her script to 1966’s El Dorado, a loose adaptation of Harry Brown’s novel The Stars in Their Courses, as “the best script [she] had done in [her] life.” High praise for oneself, especially as one could easily interpret El Dorado as a lighter, slightly more comic version of Rio Bravo. El Dorado was Brackett’s fourth of five collaborations with director Howard Hawks (1938’s Bringing Up Baby; the four other Brackett-Hawks collaborations include The Big Sleep, 1948’s Red River, Rio Bravo, and 1970’s Rio Lobo). Brackett’s inventiveness and spiky dialogue makes even the more clichéd elements of the story more entertaining than they should be. Other than Hawks and the ensemble cast, it is Brackett who is most responsible for the film’s success.

Somewhere in the American West, cowboy Cole Thornton (John Wayne) rides into the town of El Dorado for a job offer from local landowner Bart Jason (Ed Asner). His longtime friend, Sheriff J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum) meets with him, quickly deduces the reason for Cole’s presence in town, and effortlessly persuades his friend to turn down the job (the mutual respect for each other – between the characters and between Mitchum and Wayne – is apparent from the moment they meet). Jason’s job for to Thornton included coercing, gently or otherwise, the MacDonald family to abandon their land and water rights. The MacDonalds are an honest family, Harrah says, and they have been the target of regular harassment from Bart Jason and his men. Over the rest of the film, Harrah, Thornton, elderly deputy Bull Harris (Arthur Hunnicutt), a youthful gunslinger named Mississippi (James Caan), and Dr. Miller (Paul Fix) find themselves further embroiled in Jason’s repeated attempts to violently force the MacDonalds out.

El Dorado’s large supporting cast also includes saloon owner Maudie (Charlene Holt, whose character has a hankering for Thornton); R.G. Armstrong, Christopher George, Johnny Crawford, and Adam Roarke as the MacDonald boys; and Michele Carey as the hot-tempered Josephine “Joey” MacDonald (Carey and Holt play two of the final examples of the “Hawksian woman”).

Comparisons to Rio Bravo are all but inevitable to cinephiles and fans of American Westerns. Where Rio Bravo is more of a movie where friends revel in each other’s’ vibes, El Dorado is squarely a story of aging cowboys whose foibles – Harrah’s alcoholism to drown his self-pity, Thornton’s first act spinal injury and free-roaming ways – may spell the difference between local tragedy and justice. Despite what she might say, Brackett’s script to Rio Bravo (co-written by Jules Furthman) is far tighter than El Dorado’s, which employs a momentum-killing six-month time skip just as its dramatic interest begins to pique (editor John Woodcock does not provide any assistance here). It takes just a tad too much time for El Dorado, which uses the time skip to introduce Mississippi and sideline Harrah due to his heavy drinking, to regain the dramatic interest it established in the opening third of the movie.

Both casts of Rio Bravo and El Dorado have advantages over the other. Rio Bravo boasts Walter Brennan and Ward Bond in supporting roles (yet I’ve never been too fond of Dean Martin’s performance). El Dorado has Mitchum (whose dynamic with Wayne is fantastic), Caan (miles better than a Ricky Nelson sticking out like a rock 'n' roll kid from the 1950s), and not enough Asner. The two films, to me, are similar in quality, and I vacillate between which is “better” (but, on a rewatch, I think I might prefer El Dorado)*.

The interplay between John Wayne and Robert Mitchum lies at the heart of El Dorado. In 2024, it remains fashionable to lambaste Wayne for not being able to act and “playing himself” – an accusation that has been around for decades. With more lightly comedic material than usual (I would not consider El Dorado a comedy, but there are good-hearted ribbings and wry situational observances that prevent this from being a pure dramatic Western), Wayne revives some of the comic timing from The Quiet Man (1952) to decent effect here, especially around Mitchum and Caan. But most compellingly, Howard Hawks directs Wayne in a way that acknowledges and plays against his on-screen persona as the accomplished Western hero. Thornton’s spinal injury in the film’s opening act sees him reckon with his mortality – in jest and in seriousness. Wayne’s delivery and his physical acting is striking to longtime viewers such as yours truly, as it is one of the first films in which Wayne must come to terms with aging and his growing fallibility, as well as his reputation for outgunning and outthinking his opponents. The seeds of what would be Wayne’s late career signature performances in The Cowboys (1972) and The Shootist (1976) begin to show themselves here.

Mitchum, perpetually sleepy-eyed and always my first choice to play a slovenly protagonist good with a revolver, is wonderful here as a sheriff with the romantic maturity of a teenager who unaccustomed to rejection. The duality of Mitchum’s Sheriff Harrah here – the fastest gun for miles around determined to uphold the law and the inebriated slob who retains a sense of humor that makes self-pitying and self-deprecation indistinguishable – is difficult to pull off, but Mitchum does exactly that. Mitchum and Wayne’s historical on-screen personas are not polar opposites, but there is nevertheless little overlap between the two aside for their marksmanship. In their only screen appearance together (the two both co-starred on 1962’s The Longest Day, but their scenes were filmed separately), it seems the two have known each other for ages. The subtle glances, the knowing facial expressions, and gentlemanly warmth in conversation bely the fact that this is their first film together. But for El Dorado, their rapport benefits the film magnificently.

Like his good friend Ernest Hemingway, Howard Hawks admired masculine competence, professionalism, and self-reliance. El Dorado rambles a little bit about duty, honor, and loyalty, but all of this surrounds the central tenants of male friendship found here and in Rio Bravo. It is the development of that friendship and simultaneous professional excellence, rather than any plot details, that concerns Hawks – and this is the frame through which he wants viewers to see this film. By his own self admission, Hawks stated that he was, “much more interested in the story of a friendship between two men” than anything else in El Dorado (including fidelity to the original novel). The range war between Jason and the MacDonald family lacks as much exposition as some might expect. Hawks and Brackett refuse to fully explain how the dispute started, as well as what the conflict has wrought during the film’s time skip.

Those who are not as competent or professional – in this film’s case, James Caan’s character of Mississippi – are simply comic relief until they can prove otherwise. For those aware of Hawks’ aversion to Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) – in which Gary Cooper’s Sheriff Will Kane spends almost ninety minutes going around town asking for help when he learns a few recently-released convicts are coming to murder him (Hawks, to my consternation, considered this cowardly and a disgrace to the Western genre) – El Dorado is yet another reaction against it.

Unlike Hemingway, Hawks (who was by no means a feminist) rejects Hemingway’s reductionist portrayals of women as “Dark” (submissive lovers) or “Light” (castrating man-killers). The female protagonists in Hawks’ films, too, demonstrate tremendous ability. The saloon keeper, Maudie, is perhaps the most keenly observant individual in the entire picture, and can pick out the psychology of a person whether she has known them for ages (such as our leads) or if they have just stumbled in for a drink. She may be the smartest person in town. Her fellow Hawksian Woman is the wild-haired Joey MacDonald (her hair feels at times like an anachronism airlifted from the 1960s, rather than a likelihood of the Old West), quick on a gun and with a quicker temper. There is not nearly enough attention on either character as previous Hawksian Women (nevertheless, we need to recall what Hawks wanted to concentrate on most here, and that’s male friendship), but what there is still improves El Dorado’s watchability aside from our two leads.

youtube

A worthy score from composer Nelson Riddle (1960’s Ocean’s 11, 1962’s Lolita) dials back the main theme more than one might expect from a midcentury Western, but it is still effective music for this film. Riddle is best known as an arranger and orchestrator for the likes of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Linda Ronstadt, not a composer. Nevertheless, arrangers and orchestrators can learn composition through osmosis if they have not already been trained in music composition. Riddle’s liberal use of harmonica perfectly captures the setting, although his use of electric guitar/bass and discernible lack of harmonic identity (especially in the strings) feels too much like television scoring from this era – Riddle was the principal composer for the 1960s Batman television series starring Adam West. Instead, the score highlights revolve around uses of the main title song and its variations.

And what about that title song? Sung by George Alexander and the Mellomen, with lyrics by John Gabriel (Dr. Seneca Beaulac on ABC’s soap opera Ryan’s Hope), “El Dorado” fits the film perfectly, and Alexander’s rich baritone musically exemplifies the masculine themes of El Dorado. Strings double underneath the vocals, with the occasional woodwind and brass section and peaking out from the melodic doubling (again, one wishes for more harmonic interest here aside from doubling the melody). A snippet of the song’s lyrics reference to Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “Eldorado”; the poem itself is recited by Mississippi. “El Dorado” is nothing but an earworm, and I just wish it (and its variations) made more appearances in the film itself.

Though Rio Bravo had elements of a changing of the guard, El Dorado cannot help but feel, by its conclusion, as a generational marker, a near-last hurrah – intentionally or otherwise. This is not, like The Wild Bunch (1969) or Unforgiven (1992), a eulogy of the Old American West. In 1966, El Dorado came at a time when the great figures of Old Hollywood and the height of the American Western’s popularity (Wayne and Mitchum) were no longer the dominant forces in American cinema. The film’s title song even opens with oil paintings from Western artist Olaf Weighorst, of evocatively overcast vistas of the West, as if in reflection.

El Dorado would be Leigh Brackett and Howard Hawks�� penultimate collaboration and penultimate Western, with Rio Lobo a few years away. Their professional partnership, so unlikely given Hawks’ status in Hollywood and Brackett’s supposedly disreputable day job as a pulp science fiction writer, is maybe one of the most underrated and undermentioned in Old Hollywood history – one that spanned the height of Golden Age Hollywood to its final years. For El Dorado, Brackett, despite a few structural missteps, once again shows her gifts for dialogue and a keen understanding of Hawks’ directorial intentions. Hawks arguably improves upon his depiction of male camaraderie from Rio Bravo, allowing our protagonists to intuit their aging (some might say obsolescence). This is a sterling Western, if slightly out of time.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* As of this write-up’s publication, I have not seen Rio Lobo (1970), which forms an unofficial trilogy of Westerns with Rio Bravo and El Dorado.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#El Dorado#Howard Hawks#John Wayne#Robert Mitchum#James Caan#Charlene Holt#Paul Fix#Arthur Hunnicutt#Michele Carey#Leigh Brackett#Ed Asner#R.G. Armstrong#Harold Rosson#John Woodcock#Nelson Riddle#Harry Brown#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To Have and Have Not” (1944)

youtube

Film Summary

During World War II, American expatriate Harry Morgan (Bogart) helps transport a French Resistance leader and his beautiful wife to Martinique while romancing a sensuous lounge singer (Bacall).

Director Howard Hawks

Writers Ernest Hemingway, Jules Furthman and William Faulkner

Stars

Humphrey Bogart

Lauren Bacall

Walter Brennan

Photos & Related Press Images

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lauren Bacall

TO HAVE AND NOT TO HAVE - Howard Hawks (1944)

"Do you think we could create a female character who is insolent, as insolent as Bogart, who insults people, who does it while laughing, and who makes the audience like her?" Howard Hawks asked screenwriter Jules Furthman. Thus was born the character of Marie Browning, the girl who teaches Bogart to whistle. And that's nothing to say that the public loved it. Bogart did too, but that's another story.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Only Angels Have Wings brings a light touch to what is essentially a serious story about the grace under pressure shown by fliers in a small South American port town who have to battle the weather to fly the mail across the Andes. Director Howard Hawks and screenwriter Jules Furthman take the familiar "you can't send the kid up in a crate like that" premise and turn into something both funny and moving. The key is that they refuse, like the pilots in their movie, to take anything really seriously, which keeps the peril and loss from bogging the film down. There is a startling moment near the end when we see tears in Cary Grant's eyes, but the movie swiftly moves to a lighter-hearted conclusion. There is some corny artifice in the settings and flying sequences, and perhaps a little too much about the relationship between the characters played by Rita Hayworth (pushed on Hawks by Columbia studio head Harry Cohn) and Richard Barthelmess. Some see Only Angels as a kind of rough draft for To Have and Have Not (1944), and Jean Arthur, who clashed with Hawks about her character, said she didn't understand what he wanted until he saw that later film. But Only Angels Have Wings stands on its own.

Only Angels Have Wings (1939) dir. Howard Hawks

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The big sleep, 1946

#crime#film-noir#mystery#the big sleep#howard hawks#william faulkner#leigh brackett#jules furthman#raymond chandler#humphrey bogart#charles waldron

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's Your Problem?

Anita Bushell on the place of the problem in a story Faulkner contacted Chandler who said he had no idea. The screenwriting team for Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1946), writers William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman, as well as director Howard Hawks, had been busy parsing the plot of the novel and wired Chandler to find out who was responsible for chauffer Owen Taylor’s…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Nightmare Alley (Edmund Goulding, 1947).

#nightmare alley#edmund goulding#jules furthman#william lindsay gresham#tyrone power#lee garmes#barbara mclean#j. russell spencer#lyle r. wheeler#thomas little#bonnie cashin#nightmare alley (1947)

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many have tried to figure out exactly who did what to whom in Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep. Screenwriters William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman are said to have consulted Raymond Chandler, the author of the novel they were adapting, about certain obscurities of the plot, and Chandler admitted that he didn't know either, which is as fine an example of being "in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason," which Keats called "negative capability." So ask not who killed the Sternwoods' chauffeur, or even who really killed Shawn Regan -- if, in fact, Regan is dead. This is one of the most enjoyable of films noir, if a movie that has so many sheerly pleasurable moments can really be called noir. It's also one of the most deliciously absurd -- or maybe absurdist -- movies ever made, including its persistent presentation of Humphrey Bogart's Philip Marlowe as an irresistible hunk, who has bookstore clerks, hat check girls, waitresses, and female taxi drivers swooning at his presence. The only thing that makes this remotely credible is that Lauren Bacall, and not just Vivian Sternwood Rutledge, actually did. In his review for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther, one of the most obtuse critics who ever took up space in a newspaper, called it a "poisonous picture" and commented that Bacall "still hasn't learned to act" -- an incredible remark to anyone who has just watched her exchange with Bogart ostensibly about horse racing. This is, of course, one of Howard Hawks's greatest movies, and of course it received not a single Oscar nomination -- not even for Martha Vickers's delirious Carmen Sternwood. Vickers was so good in her role that her part had to be trimmed to put more focus on Bacall, who was being groomed for stardom. Sadly, Vickers never found another role as good as Carmen. Dorothy Malone, who did go on to stardom and an Oscar, steals her scene as the bookstore owner amused and aroused by Marlowe's charisma. And then there's Elisha Cook Jr. as a small-time hapless hood not far removed from the Wilmer who stirred Sam Spade's homophobia in The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1946). Except this time his demise elicits something from Marlowe that Spade was incapable of: pity.

What's the matter? Haven't you ever seen a gun before? What do you want me to do, count three like they do in the movies? THE BIG SLEEP (1946) dir. Howard Hawks

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

Betty Compson and George Bancroft in The Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928)

Cast: George Bancroft, Betty Compson, Olga Baclanova, Clyde Cook, Mitchell Lewis, Gustav von Seyffertitz. Screenplay: Jules Furthman, based on a story by John Monk Saunders; titles: Julian Johnson. Cinematography: Harold Rosson. Art direction: Hans Dreier. Film editing: Helen Lewis.

Josef von Sternberg is mostly remembered today for his fetishization of Marlene Dietrich in romances with glamorous settings like Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932), but The Docks of New York shows that Sternberg could handle grit as well as glamour. If it's not as well known as the Dietrich films, it's partly because it was largely overlooked at the time of its release because of the flurry of interest in talkies -- it's one of the last important silent movies. But it's as strikingly visual in its way as the more opulent Sternberg movies, with the collaboration of director, cinematographer Harold Rosson, and art director Hans Dreier giving a solid story by Jules Furthman -- who also wrote Morocco and Shanghai Express -- the right flavor. Bill Roberts (George Bancroft), the burly stoker on a tramp steamer, goes ashore for a one-night leave in New York, after being warned by the engineer, Andy (Mitchell Lewis), not to come back drunk. Not one to follow his own advice, Andy then goes to a waterfront dive called the Sandbar where he is surprised to meet his wife, Lou (Olga Baclanova), whom he has abandoned. Meanwhile, Bill rescues a suicidal prostitute named Mae (Betty Compson), when she tries to drown herself, and takes the unconscious woman to a room above the Sandbar. Lou comes to the room to aid in reviving Mae while Bill goes to find some clothes for her. He steals them from a closed pawn shop and returns to find a revived Mae, who turns out to be quite pretty. They go down to the bar, where Andy puts the moves on Mae and gets into a fight with Bill, which Andy loses. Two lost souls, Mae and Bill are attracted to each other, and in a kind of what the hell way, he proposes marriage. They talk wistfully about his giving up the life at sea, and she accepts. A waterfront missionary (Gustav von Seyffertitz) performs the ceremony in the bar. But the next morning Bill has second thoughts and leaves for the ship while Mae is still asleep. Andy, however, still smarting from the beating Bill gave him, goes to the room, where Mae has discovered Bill has left her. She refuses Andy's advances and he tries to rape her, only to be shot by Lou, who has arrived just in time. Seeing the commotion outside the Sandbar, Bill returns to the scene, where he and Mae say their farewell. But when the ship sails, Bill thinks better of it, jumps overboard and swims to shore, where he finds that Mae has been arrested for stealing the clothes from the pawn shop. He confesses to the crime and is sentenced to jail, promising to Mae that he'll return once he serves his sentence. This is solid melodrama stuff, elevated by the performances, which establish the essential loneliness that unites Bill and Mae, and by the fine production values.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Big Sleep - Howard Hawks (1946)

poster

#the big sleep#howard hawks#humphrey bogart#lauren bacall#Warner Bros#1946#1940s#noir#film noir#martha vickers#dorothy malone#william faulkner#raymond chandler#leigh brackett#jules furthman#elisha cook jr.#poster

6 notes

·

View notes