#Leigh Brackett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Screenwriter Leigh Brackett gets her own publicity still for El Dorado (1966). Leigh was born in Los Angeles and first worked with Howard Hawks on The Big Sleep (1946). She also earned screenwriting credits on Rio Bravo, Hatari, and Rio Lobo, all with John Wayne.

Hawks fan John Carpenter's Halloween has a character named Sheriff Leigh Brackett.

In a 1974 interview with Starlog Magazine, Brackett described working with Hawks: “he would throw a bunch of ideas at me, and say, ‘This is what I want.’ Then, he would go away, and I wouldn’t see him again for weeks. He left it up to me to fit his ideas together, and turn them into a story.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨The Best of Leigh Brackett✨

Читалось у тандемі з Євою, адмінкою гриб з ю��ґота.

Колись цей день мав настати… Ми з Євою так часто згадували пані Лі, що не прочитати її творів було б максимально незручно. Тож ми вирішили почати зі збірки найкращих оповідань Брекетт і зараз ви будете читати як вона мені)

В загальному варто відмітити, що The Best of Leigh Brackett не грає такою різноманітністю, яка була в The Best of Henry Kuttner, але швидше за все тому, що Брекетт мала більш чітко визначені жанрові рамки в яких вона працювала (здебільшого це sword&planet), в той час, як Каттнер трошки кидався з тематик в тематику та з сетинґу в сетинґ. Але попри цю меншу різноманітність збірка пані Лі мені все ж таки сподобалась. Хоч Єва і жалілась на те, що засилля sword&planet в якийсь момент починає набридати, але я був у відповідному настрої та вайбі тож мені ці оповідання шикарно пішли (за виключенням одного).

Хотілось би трошки відзначити типажі з котрими працювала пані Лі. Мені було дійсно цікаво побачити, що Брекетт доволі часто працювала з персонажами, що були people pf color. Відносно часто вона робила їх головними героями й в принципі гарно їх прописувала, це приємно. З жіночими персонажами в Бреккет ситуація двояка… В усіх з наведених в збірці оповіданнях головні герої чоловіки, а жінкам завжди відведенні другі, треті й т.д. ролі. Не сказав би, що це якийсь шок підхід, як на мене, фантастика в 40-50-х була місцем чоловічих авторів, тож Брекетт вкладалася в тодішні тенденції, хоча в другій половині 40-х та в 50-х пані Лі, як на мене, вплітає все більше жіночого погляду у своїх персонажок (і я про це ще згадаю). Проте, зважаючи на специфіку sword&planet як жанру, жінки або сексуальні оголені/напівоголені танцівниці на фоні, або дами в біді, або супутниці головного героя.

В наздогін до оголених танцівниць, скажу що оповідання не настільки еротизовані, як могло �� скластися, якщо ви читали наші з Євою жарти в чатику при каналі UAGeek. Хоч Брекетт полюбляє вставити максимально випадкові горні сцени в оповідання (так-так, сцена у вітальні з The Woman From Altair, я про тебе говорю).

Окремо хочу відмітити передмову Едмонда Гамільтона (чоловік Брекетт і теж письменник-фантаст, хто не знав) та післямову самої Лі Брекетт. Вони дуже милі й інформативні. Було дуже цікаво читати про те, як Едмонд та Лі ремонтували свій тільки куплений будинок, чи про те як вони звикли до того, що кожен мав кардинально різні підходи до написання творів. Ну і вважаю, що мені (і вам!) конче треба було знати, що Гамільтон називав Лі томбоєм.

Тепер я б хотів поговорити про деякі оповідання зі збірки (не про всі, чесно!):

The Jewel of Bas

Єва вже в себе на каналі писала гарний допис про це оповідання, хотів би вам нагадати.

The Veil of Astellar

Насправді моє улюблене оповідання. Можливо це тому, що це оповідання про космічних вампірів, а я люблю вампірів. Проте Лі тут дуже цікаво працює з вампірами як такими, повністю відходячи від їх класичного образу і дає цікаву проблематику для головного героя, котрий, власне і є вампіром (але тут є пара але). Ну і тут вперше в збірці з'являється жіночий персонаж, котрий не існує просто для головного героя. Це сильна впевнена в собі вампірка, котра, проте, має страждати тому, що відкрилася не тій людині.

The Moon That Vanished

Це оповідання я відмічаю не тому, що воно таке хороше… Навпаки… Це чесно найгірше оповідання в збірці, це не дуже цікавий морський "тревел блог" того, як головний герой з ще двома персонажами тікає від переслідування і пливе в "святі землі". Паралельно страждаючи за мертвою коханою, що, проте, не заважає йому романсити його сусідку по кораблю. Чесно ледь продирався крізь ці 40 сторінок тексту.

Enchantress of Venus

Оповідання на котрому в нас з Євою розійшлись думки. Це знову чисто води sword&planet, проте ще й частина серії пригод постійного персонажа пані Лі — Джона Старка. І це дійсно міцненьке таке sword&planet, де ти бонусом отримуєш гомоеротичні вайби між Старком і його найкращим другом, гру престолів в межах одного роду на мінімалках і шикарну Варру. Чи поводиться вона так наче в неї овуляція, а Старк перший чоловік котрого вона бачить в житті? Можливо. Чи стає вона від цього менш 💅slay queen💅? Ні краплі. Це впевнена в собі дівчина, котра знає собі ціну, знає чого вона хоче і робить все, що вважає за потрібне, просто ікона. І насправді в цьому оповіданні все прям дуже добре з жіночими персонажами (ну може за виключенням Зарет).

The Woman From Altair

Останнє оповідання котре я хотів би відмітити окремо. The Woman From Altair, як на мене, історія про двох жінок: перша — хоче помститися своєму кривднику (брат головного героя); а друга хоче захистити свого коханого (головний герой). Хоч твір початково подається більше як історія про двох братів, та й головний герой в оповіданні чоловік і саме з його точки зору ми й дивимось на події. Його брат повертається з місії в далекому космосі та привозить з собою наречену з іншого світу, хоч далі за розвитком сюжету виявиться, що він її "купив" на її рідній планеті — Альтаїрі. І саме в цей момент оповідання буквально перетворюється на твір про жіночу помсту, де Жінка з Альтаїра хоче забрати у свого кривдника все йому близьке (тобто і брата теж). З іншої сторони кохана головного героя — Марта (mother), намагається просто врятувати свого хлопця. Хоч їй і приходиться вбити жінку з Альтаїра, проте вона не те щоб засуджує її за помсту, а просто хоче врятувати свого хлопця. Єдине, що мені трошки не вистачило розкриття Марти, бо вона хоч і mother, проте її основна мета у творі чисто врятувати головного героя.

У висновку я б сказав, що Брекетт не підвела моїх очікувань і збірка її оповідань дійсно мені сподобалась. Чесно радив би вам ознайомитись з її творами, проте підготуйтеся що буде багато sword&planet.

0 notes

Text

Charles Cyphers as Sheriff Brackett in Halloween (1978)

Watercolors on Paper, 8.5" x 11", 2024

By Josh Ryals

#charles cyphers#sheriff brackett#leigh brackett#halloween#halloween 1978#michael myers#haddonfield#fan art#original art#portrait#painting#watercolors#tribute#josh ryals art#joshua ryals art#joshryalsart#john carpenter#70s horror

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelly Freas - Lorelei of the Red Mist - 1953, by Leigh Brackett and Ray Bradbury

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Mars Minus Bisha" by Leigh Brackett is a fantastic story. Devastating.

0 notes

Text

vote yes if you have finished the entire book.

vote no if you have not finished the entire book.

(faq · submit a book)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Road to Sinharat" is available to read here

#short stories#short story#the road to sinharat#leigh brackett#20th century lit#english language lit#american lit#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls#links to text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leigh Brackett in an original publicity still for El Dorado (1966). Leigh was a screenwriter who first worked with Howard Hawks on The Big Sleep (1946). She worked on most of his movies after that. Leigh is also respected as a fantasy writer. Her last writing credit was for the first treatment of The Empire Strikes Back.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Leigh Brackett's pulp SF stories are full of stuff like "hero & heroine flirt by giving each other facial scars" and planets whose dress code is "tits out always"

She also wrote the first draft of Empire Strikes Back.

imagine if Star Wars was allowed to be that horny. the hotness would make people's heads explode.

#star wars#leigh brackett#the empire strikes back#esb#empire strikes back#tesb#literature#science fiction#pulp sf#movies#film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bifrost 105, cover by Nicolas Fructus

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leigh Brackett defending Science Fiction, 1944.

1 note

·

View note

Text

'The Long Tomorrow' Warns Against Theocracies

'The Long Tomorrow' takes you by the hand and calmly tries to kick some sense into you. #sf #scifi #books #bookreview

The Long Tomorrow (1955) by Leigh Brackett takes an unequivocal stance on the perils of repression and theocracy. Coming at the problem from two angles she contrasts the ideology of religion with its often contrary reactions. Through clear and effective prose Brackett paints a world where horror wears a smile. Brackett’s multi-faceted talent makes The Long Tomorrow a classic that needs wide…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

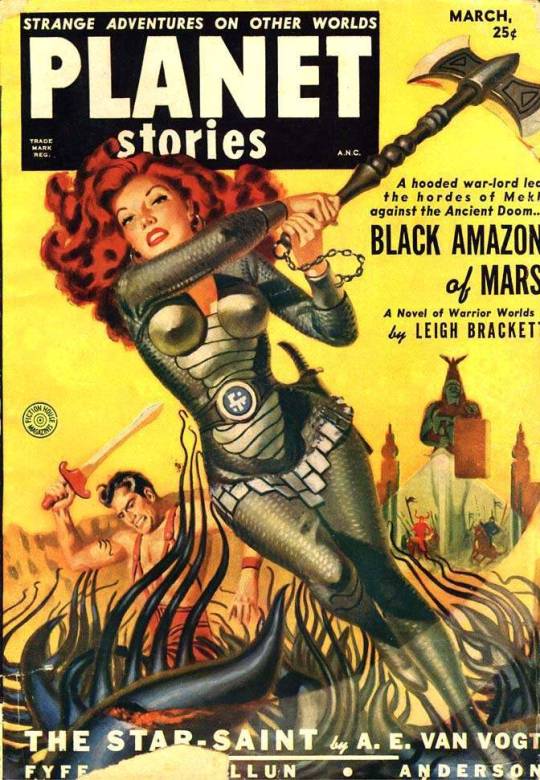

Planet Stories March, 1951 issue. Cover by Allen Anderson.

The cover story, Black Amazon of Mars by Leigh Brackett, was an Eric John Stark episode, his final appearance in a magazine until Brackett revived the character in the 1970s. The aforementioned Black Amazon, featured so prominently on the cover, begins as Stark's antagonist but ends up an ally.

The attitudes of the time did not allow for Stark (the guy with the sword) to be depicted as Brackett described him. Stark had Caucasian features, but his skin was almost pitch black from having been raised on the surface of Mercury with its close proximity to the Sun.

#Planet Stories#Black Amazon of Mars#Eric John Stark#Leigh Brackett#pulp magazines#science fiction#science fantasy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

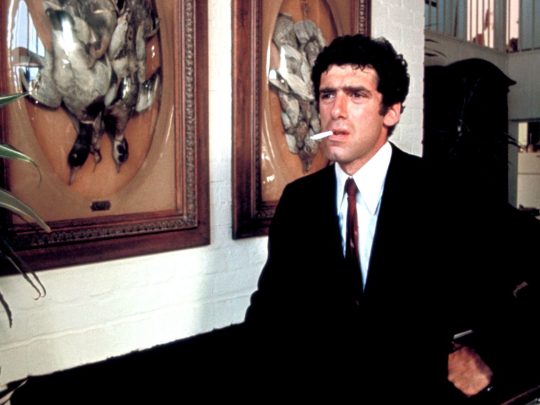

The Long Goodbye, Robert Altman (1973)

#Robert Altman#Leigh Brackett#Elliott Gould#Nina van Pallandt#Sterling Hayden#Mark Rydell#Henry Gibson#David Arkin#Jim Bouton#Warren Berlinger#Stephen Coit#Vilmos Zsigmond#John Williams#Lou Lombardo#1973

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

vote yes if you have finished the entire book.

vote no if you have not finished the entire book.

(faq · submit a book)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1949.

I couldn't find the artist.

11 notes

·

View notes