#John Skylitzes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Another chalice in San Marco, also likely looted from Constantinople by the crusaders, incorporates a vivid green glass bowl of Islamic origin. Decorated with a stylized running hare motif, the bowl was cut with a rotating wheel, a lapidary technique commonly used for sculpting stones. As such, it was likely produced in Islamic lands: either in ninth- or tenth-century Iran, or perhaps tenth- or eleventh-century Egypt, where this technique was used. Eastern Roman artisans probably transformed the green glass bowl into a chalice in the eleventh century with the addition of a silver gilt setting, gems and pearls, and an enamel inscription. Now partially lost, the inscription once read, “Drink of this all of you, this is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed for you and for many for the remission of sins.” These words, spoken by Christ at the Last Supper and repeated by the clergy during the celebration of the Eucharist in the Eastern Roman Empire, enable art historians to identify this vessel as a Eucharistic chalice with confidence.

But how did this Islamic bowl end up in the Eastern Roman Empire and why did the Eastern Romans transform it into a chalice for the Eucharist?

It is possible that the green glass bowl came to Constantinople the same way that it eventually traveled from Constantinople to Venice: as booty from war (though not a crusade). The Eastern Romans made military gains against their Islamic neighbors to the east during this period and may have taken this glass bowl as plunder from Islamic lands. On the other hand, war was not the only way that objects traveled between cultures in the medieval Mediterranean, and there is no evidence that this bowl was brought to Constantinople as war booty. Historical documents record that glass vessels like this one were sometimes among luxury objects exchanged as diplomatic gifts by Eastern Roman rulers and their Islamic neighbors, so it is possible the green glass bowl came to Constantinople as a diplomatic gift from the Abbasids, Fatimids, or some other people. It is also possible that the green glass bowl simply came to Constantinople through trade. The tenth-century Book of the Eparch (a book of Eastern Roman commercial law) testifies that there was a market for Islamic goods in Constantinople at this time. But since we lack explicit textual evidence to corroborate any of these theories, we cannot say for certain how the green glass bowl came to Constantinople.

Materiality and ornament

As with the Romanos chalices, the materiality of the green glass bowl was surely an important factor in this object’s reuse. The stunning green hue of the glass bowl is unusual among surviving Islamic glass work. Both its color and its fashioning with a wheel were likely intended to produce the appearance of a precious stone, such as an emerald. And as with other Eastern Roman glass chalices, the transparency of the green bowl would have enabled worshippers to glimpse the Eucharistic wine while the inscription around its rim affirmed that it was the very blood of Christ.

The bowl’s running hare motif, however, is unique among surviving Eastern Roman chalices. Many Eastern Roman viewers would likely have recognized the angular hare motif as not Eastern Roman and perhaps even as Islamic in origin. This raises questions about why such a vessel might be converted into a chalice for the Eucharist, and how Eastern Roman users would have understood it.

Art, court, and diplomacy

To answer these questions, it is important to understand this vessel as a product of both the church and court of Constantinople. Although this chalice bears no donor inscription like those attributed to emperor Romanos, its costly materials and high quality of craftsmanship indicate that it too was likely commissioned by an emperor or some other elite patron in the court in Constantinople. As such, we can understand this vessel as one of many examples of Eastern Roman appropriation and imitation of Islamic culture in the tenth and mid-eleventh centuries. Such Islamic or Islamicizing elements appear on Eastern Roman clothing, jewelry, and lead seals of this period. Eastern Roman emperors and members of the court likely adopted such Islamicizing objects to project wealth, power, and a cosmopolitan identity.

In addition to their primary ritual functions, there is also evidence that sacred objects like chalices sometimes played a role in Eastern Roman diplomacy. The eleventh-century Eastern Roman historian John Skylitzes describes how the emperor Leo VI led Arab diplomats into the church of Hagia Sophia and showed them sacred vessels and other church objects—an episode illustrated here in a twelfth-century copy of Skylitzes’s history. In this scene, two Arab figures enter the church from the left, while the emperor—crowned and clad in gold—points to a golden chalice and other church objects held for display by church officials.

So, we can conclude that the patron of the chalice with hares likely intended Eastern Roman viewers (and perhaps even foreign visitors) to recognize the Islamic origin of the green glass bowl with hares. To display such a beautiful object of Islamic origin in tenth- and eleventh-century Constantinople was to project wealth, power, and a cosmopolitan identity. If there were any concerns about using an Islamic object for Christian religious purposes, the chalice’s Eastern Roman setting with its Christian inscription must have rendered the glass bowl suitable for use in the celebration of the Eucharist. An inventory of objects in the church of San Marco from 1325 mentions a “green chalice decorated with silver,” perhaps referring to the chalice with hares and suggesting that this object may have continued to function as a Eucharistic vessel even after it was transferred from Constantinople to Venice. Together with the Romanos chalices, the chalice with hares shows the important roles that materiality, ornament, and craftsmanship could play in an object’s cross-cultural mobility, reuse, and preservation through the centuries.

Byzantine chalice which originated as a green glass cup or bowl which originated from either Egypt or Iran in the 9th-11th century. When it made it's way to the Byzantine Empire it was decorated and turned into a chalice

#history#military history#religion#christianity#eastern orthodox church#islam#trade#commerce#art#art history#carving#italy#veneto#byzantine empire#iran#egypt#venice#constantinople#istanbul#st mark's basilica#haga sophia#john skylitzes#leo vi the wise#chalices#book of the prefect#glass#communion#eucharist

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

08 Works, Today, June 14th, is Saint Methodius I's day, his story in Paintings #165

Unknown artistMethodius I of ConstantinopleBulgarian icon St. Methodius I, also spelled Methodios, (born 788/800, Syracuse, Sicily — died June 14, 847, Constantinople)was patriarch of Constantinople from 843 to 847… Please follow link for full post

View On WordPress

#Ancient#Art#Biography#Fine Art#History#John Skylitzes#Leo#mythology#Nikephoros#Paintings#religion#Religious Art#St. Methodius I#Theodora#Theophilos#Zaidan

0 notes

Note

Theophano?

Hi! I'm not sure what you mean to ask, so I'm just going take it as an opportunity to talk about Theophano and her life.

Theophano was a Byzantine empress in the second half of the 10th century. She was the daughter-in-law of Constantine VII; wife of Romanos II and Nikephoros II Phokas; lover of John I Tzimiskes; and mother of Basil II and Constantine VIII.

She was famed for her extraordinary beauty, with chronicles hailing her as a "miracle of nature" who surpassed all other women of her age.

She was born to a family of reportedly low birth, with Skylitzes and Leo the Deacon both emphasizing her obscure origins. The former also claimed that Theophano's father was an innkeeper, and while we don't know if this is true or exaggerated, given the background of some former empresses (eg: Theodora), it's certainly plausible. We know next to nothing about her childhood, although she was probably close to her mother, who she may have brought to the palace and who was later exiled along with, although separately from, her daughter.

Theophano met Romanos, the heir of Emperor Constantine VII, as a teenager. The young prince seems to have become infatuated by her and decided to marry her in around 956, accordingly forcing a fait accompli on his family. It's possible that the imperial dynasty may have attempted to invent a noble lineage for Theophano to circumvent the controversy.

Theophano adopted her name after her marriage, having previously been known as Anastaso. She was trained in her duties as a member of the royal family, serving her apprenticeship as junior Augusta under the tutelage of her experienced mother-in-law Helena Lekapena. Both empresses were prominent in imperial ceremonies during Constantine’s reign, particularly during the reception of Olga of Kiev.

Romanos II came to the throne on November 959. At least one chronicle accused him and Theophano of conspiring together to poison her father-in-law Constantine and hasten their own ascent to power, although no evidence suggests that the former emperor died of poison or any kind of foul play.

During Romanos's very brief reign, he seems to have played little role in governance but instead entrusted administration to the eunuch Joseph Bringas. Most historians believe that Theophano was very influential during that time, with Romanos relying on her for advice and support. She certainly participated in political intrigue, supplanting the much more established and well-connected dowager empress, and successfully convinced Romanos to forcibly exile all his sisters to convents. This may suggest that she had less-then-cordial relations with her in-laws. More strikingly, it demonstrates that despite her youth and origins, Theophano succeeded in removing any other candidate of potential influence around Romanos, establishing herself as the dominant force at court. It's tempting to speculate what further role she might have played had her husband lived longer, but I suppose we’ll never know.

During their marriage, she and Romanos had four known children together: Helena, Basil, Constantine and Anna.

Romanos died prematurely in 963, after a short reign of less than three-and-a-half years. Theophano was once again rumored to have poisoned him, although this is extremely unlikely: as a favored and influential young empress, she had nothing to gain everything to lose from such an action. Moreover, she had given birth to her youngest child just a few days prior and was still in confinement, making it logistically improbable for her to have orchestrated such a conspiracy, with all the variables it entailed.

During her sons’ minority, Theophano was appointed as regent to the throne on the authority of the senate and patriarch. During that time, Skylitzes claimed that she was responsible for poisoning Stephen, son of Romanos Lekapenos, a possible contender for the throne who had been in exile and died suddenly on Easter Sunday. If this is true, it would have been a political act to secure her sons’ positions against possible threats, although the veracity of the accusation is unknown.

Unfortunately, Theophano’s regency was destined to be a short one. While one source asserted that she was capable of handling political affairs herself, and that she may not have wished to remarry, circumstances seemed to have forced/enabled her to choose otherwise.

At the time of Romanos's death, there was bad blood between Bringas, who remained administer of the empire, and Nikephoros Phokas, a renowned general of the army. The latter decided to seize the throne, probably due to the persuasion of his supporters rather than his own inclination. He was proclaimed Emperor by the army and was bound by an oath not to conspire against the rule of the young emperors. However, Bringas relentlessly plotted against him, attempting to deprive him of the position and offering the crown to someone else of his choosing.

During this factional struggle, Theophano decided to back Nikephoros, probably recognizing that the local and military support he possessed would be beneficial for her sons. She provided him with required legitimacy and was instrumental in his ascension to power: according to Zonaras, it was on her orders that he came to Constantipole to celebrate his triumph in April 963. Skylitzes even reports that they were lovers, and that Nikephoros desired the throne due to his infatuation with the beautiful young empress. Although it’s plausible the pair were in close communication with each other and may have decided to marry, an extra-marital actual affair is out of question given what we know of Nikephoros’s reticent and ascetical character. This was probably yet another way for chronicles to try and malign Theophano.

The situation was complicated by the fact that Nikephoros was godfather to one or both of Theophano’s sons, which would technically make the marriage uncanonical. In particular, the patriarch Polyeuktos was apparently very opposed to it. However, Nikephoros refused to be separated from Theophano, and the situation was resolved with the (probably invented) explanation that it was actually Nikephoros’s father, Bardas Phokas, who had been the young emperors’ godfather.

Theophano was a very influential empress during Nikephoros’s reign, with Leo the Deacon noting with disapproval that he “habitually granted Theophano more favours than were proper”. She was given profitable estates, was an active intercessor, and witnessed her two sons living in splendor and comfort in the palace. Considering what we know about her later life, she seems to have cultivated excellent relations with them.

However, relations between the imperial couple may have deteriorated, primarily from Theophano’s perspective, though chronicles aren’t unanimous on the details. Zonaros claimed that Nikephoros kept away from her due to his disinterest in sexual relations (though he appears to have still been devoted to her and honored her as an empress), while Skylitzes records that Theophano was the distancing partner. Some sources believed that Theophano may have grown concerned for the future and safety of her children, either at Nikephoros or his brother Leo’s hands.

All sources agree that Theophano and John Tzimiskes, the handsome and charismatic nephew of Nikephoros, became lovers in the late 1960s. Together, they conspired together to depose Nikephoros and place John on the throne, almost definitely with Theophano as empress. This was planned clandestinely in John’s home, and according to Leo the Deacon, Theophano received several warriors who she kept in a secret room near her quarters to enact the plan.

The Emperor’s assassination was eventually enacted on 10th December 969. Reportedly, Theophano pretended that she was heading out to instruct the Bulgarian princesses who had recently arrived as brides for her sons, and told Nikephoros to leave the bedchamber door open for her as she would close it when she returned. He did as she asked, making his customary devotions and falling asleep, which allowed the attackers to strike him unaware. John played a crucial role in the actual murder, striking Nikephoros on the head with his sword, though the coup de grace was delivered by one of the other conspirators, Leo Abalantes. While Theophano certainly played a vital role in the conspiracy, her direct participation in the murder itself is unknown. Later sources would dramatize her involvement: for example, Matthew of Edessa claimed that Theophano was the one who actually handed John the sword in order to carry out the murder.

Whatever her exact motivations, it’s clear that Theophano intended to orchestrate/support a new transfer of power just as she had with Nikephoros, becoming Empress for a third time. This was unprecedented across Byzantine history till that point, making her a singular figure.

However, things didn’t go as planned. John does seem to have intended to marry Theophano, and, after promising to ensure the safety and status of Romanos’ young sons as co-emperors, gained local support. However, when he went to St Sophia to be crowned, the patriarch refused him entry and presented him with three conditions: Theophano had to be banished from the palace and Constantinople, the murderer of Nikephoros had to be dealt with, and the measures taken against the church by Nikephoros had to be revoked. John, who keen to establish his own position and absolve himself from any blame, agreed or was forced to agree to these demands.

Theophano was thus sentenced to exile to the island of Prote or Prokonnesos. She didn’t accept her fate quietly: according to Skylitzes, she actually managed to escape from Prokonnesos and reappeared in the capital Constantipole, seeking refuge in the Hagia Sophia. However, she was forcibly removed by Basil the Nothos, who sent her to a newly created monastery of Damideia in distant Armenia. Before this, she was granted the request of an audience with the Emperor and her former lover John, which was not peaceful. Theophano reportedly “insulted first the emperor and then Basil [her son], calling him a Scythian and barbarian and hitting him on the jaw with her fists”. Her activities during her years-long exile are otherwise unknown.

After John’s death in January 1976, Theophano’s sons recalled their mother to the palace. She resumed her rightful position as empress, and since her elder son Basil never married, she would have remained the senior Augusta and most important imperial woman throughout her life.

Georgian sources indicate that Theophano also resumed her role as a prominent political figure, directing negotiations to broker an alliance with the Georgian overlord David of Taiq to counter a revolt by the general Bardas Skleros against her sons. She was also a generous patron and seems to have been partially responsible for supporting the foundation of the ‘Iviron’ monastery on Mt Athos reserved for monks of Georgian nationality.

However, Theophano vanishes from historical records after 978. It’s unknown if she died, retired, or if evidence for her activities has simply been lost across time.

All in all, Theophano seems to have been a fascinating woman who lived a full and sensational life. In many ways, she still remains a question mark, as very few primary sources survive to document the reigns of Romanos, Nikephoros, or the early years of her sons in detail. The majority of her daily activities, motivations, and even her ultimate fate, all remain unknown. But while this could have enhanced the effect of intrigue that already surrounds her, it seems to have had the opposite effect. Despite her controversial career, colourful romantic life, recorded influence over the court and affairs of state, and undeniable impact on the trajectory of the Byzantine Empire, Theophano remains a frustratingly unknown and often forgotten figure in most general histories of the dynasty.

She is also one of the most viciously maligned women in Byzantine history, vilified and scapegoated by contemporaries and historians as a wicked seductress, decadent intriguer, and violent murderess. Ultimately, we'll never know if Theophano was motivated by survival, desire, ambition, a combination of the above, or something else altogether. What we do know, however, is that she seems to have been a particularly strong-willed individual capable of navigating manifold realms of power despite not being born into it, and surviving the turbulent reigns of no less than six emperors. We can also appreciate how, in many ways, it was Theophano who seems to have gotten the last laugh: she outlived all her opponents and played a vital role in safeguarding the rights of her eldest son Basil II, who would go on to become the longest-ruling Roman Emperor.

In conclusion - she was fantastic and I love her.

References:

Lynda Garland, Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD: 527-1204

Anthony Kaldellis, Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade

John Ash, A Byzantine Journey

#ask#theophano#byzantine history#byzantine empire#women in history#my post#10th century#romanos ii#nikephoros ii phokas#basil ii#John I Tzimiskes#Byzantium#empress theophano

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

cackling

if only he knew...

#akshlshdks i can’t name any philosophers but#kassia was a poet#and then there’s basil ii#constantine viii#zoe porphyrogenita#romanos iii argyros#michael iv the paphlosgsnbsgdkbd#michael v kalaphates#theodora porphyrogenita#constantine ix monomachos#romanos iv diogenes#i also know of john the orphanotrophos#and basil skleros#and john skylitzes#and psellos#and giorgios maniakes#and constantine diogenes#byzantium#byzantine empire#history#not to flex but#nonsense#this is an excerpt from my history textbook btw#wait i did name a philosopher#psellos????#ig#and romanos iii was a wannabe philosopher so#byzantine things

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leo V, murdered on December 25, 820–first account is told by John Skylitzes in his Synopsis of Histories

Nikephoros II Phokas, murdered on December 11, 969–story told in Leo’s the History of Leo the Deacon

Romanos III Argyros, murdered on April 11, 1034– story told by Michael Psellus in his Chronographia

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Khan Omurtag of Bulgaria

From the Chronicle of John Skylitzes 11th century

• Omurtag (Bulgarian: Омуртаг) was a Great Khan (Kanasubigi) of Bulgaria from 814 to 831. He is known as "the Builder".

#khan#omurtag#bulgaria#chronicle of john skylitzes#art#illustration#middle ages#11th century#9th century

1 note

·

View note

Photo

demons (?) and lovecraftian horrors (?) from a byzantine history book by John Skylitzes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

eugene!! what are you doing to leo phokas!!!

If this was originally posted on tumblr it would have become the big new trend within hours

[Image description: a tweet from Twitter user @ow_riki reading: ‘Had a dream that the new Twitter fad was to post a picture of a giant isopod photoshopped into historical events and going “Eugene! Not again!!”.’ It has 2,794 likes, 68 quote tweets and 797 retweets. End ID]

#did nicholas mystikos put you up to this#history#medieval history#byzantine history#roman empire#john skylitzes

42K notes

·

View notes

Text

“At the battle on the Danube in 971, before Sviatoslav sued for peace, there came a black day of defeat for the Rus, when the Byzantine emperor’s cavalry drove the Rus warriors back against the walls of the town and many were “trodden underfoot by others in the narrow defile and slain by the Romans when they were trapped there.” As the victors were “robbing the corpses of their spoils,” wrote John Skylitzes in his Synopsis of Byzantine History a hundred years later, “they found women lying among the fallen, equipped like men; women who had fought against the Romans together with the men.”

The real valkyrie, The hidden history of viking warrior women, Nancy Marie Brown

#the real valkyrie#history#women in history#kievan rus'#byzantine empire#10th century#quotes#warrior women#women warriors#sorry no proper update today#due to personal reasons

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was Greek Fire and how was it used?

For quite some time, there has been a fairly persistent myth that Greek fire has been utterly lost to the sands of time. Greek Fire was never truly lost, however, as its use prevailed in the armies of the Arabs and Turks for quite a time thereafter. Further, the recipe itself was never really in question as we have always had Roman and Arab sources outlining it since the 3rd century CE such as Julius Sextus Agrucanus and Ibn Mangli. It certainly became state secret, but in the case of the various Arabs, Turks, and Romans themselves, keeping it a state secret was never enough.

Some scholars have dedicated themselves to tracing the lineage of Greek Fire/Naft, its usage, and where it was gathered from. The best of this group, in my mind, come down to John Haldon and Tarek M. Muhammad. The latter of this group focuses more on the Arabic side of things which is something for another time.

The debate regarding the recipe largely comes down to whether it’s sulfur based, gunpowder based, petroleum based, or something else entirely. Haldon has previously picked apart the other arguments and, based on overwhelming contemporary evidence and modern experimentation, I am inclined to fully agree with him.

Petroleum for the Byzantines was harvested from the oil fields of the Northern Caucasus region using large amphorae that were essentially dunked into the oil fields that are characterised by Haldon as having “paraffin-rich varieties low in non-hydrocarbons” meaning very inflammable. This is severely problematic for the Byzantines as this area became frequently contested between a variety of hostile entities including the Quman-Kipchaqs and Mongols. Rivalries with the Genoese and Venetians almost definitely contributed to this rapid loss of equipment as well. This area, along with the Ruslands to the north, was clearly critical for the Byzantines as we see in the tenth century document De administrando imperio outlining the severity of good diplomatic relations in these areas. Eventually, though, the Byzantine cycle of failure just could not hold up to the pressures on literally every front and this resource became unobtainable.

What’s regarded as the game-changer regarding Greek Fire is the invention and adoption of the siphon used to propel it. How it actually would have operated is quite confusing given the complexity of the texts, but Haldon suggests "that oil was pumped from a reservoir, which was heated over a hearth or grate, and projected under pressure through a swivel nozzle or tube.” It’s certainly very plausible given how sophisticated Byzantine pump-valve systems already were. These pump systems were likely fixed in place, especially in the imperial fleet, and depictions of them used as “hand syringes” are regarded as being “garbled common-sense” by Haldon.

The classic and most widely known image of Greek fire (posted below) comes from the Madrid Skylitzes which already makes it fairly sketchy.

Provided below and taken from Haldon’s experimental archaeology are his ideas for how the siphon would have operated.

His experimentation ended with a conclusive success pictured below.

#byzantium#Byzantine Weapons#byzantine history#byzantine#roman#roman weapons#roman empire#greece#medieval#medieval history#middle ages#middle east#turkey#georgia#arms and armour#archaeology#greek fire

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

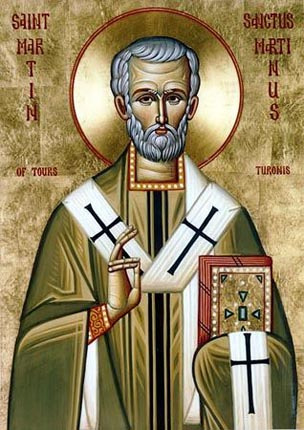

Saints&Reading: Sun., Oct. 25, 2020

Commemorated on October 12_ Julian calendar

St Martin “ The Merciful” of Tours ( 397)

St. Martin of Tours, (born 316, Sabaria, Pannonia [now Szombathely, Hungary]—died November 8, 397, Candes, Gaul [France]; Western feast day, November 11; Eastern feast day November 12), patron saint of France, father of monasticism in Gaul, and the first great leader of Western monasticism.

Of pagan parentage, Martin chose Christianity at age 10. As a youth, he was forced into the Roman army, but later—according to his disciple and biographer Sulpicius Severus—he petitioned the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate to be released from the army because “I am Christ’s soldier: I am not allowed to fight.” When charged with cowardice, he is said to have offered to stand in front of the battle line armed only with the sign of the cross. He was imprisoned but was soon discharged.

While he was still in the military and a catechumen of the faith, Martin cut his cloak in half to share it with a beggar. That night, he dreamed that Jesus himself was clothed with the torn cloak. When he awoke, the garment was restored. Moved by this vision and apparent miracle, Martin immediately finished his religious instruction and was baptized at age 18.

On leaving the Roman army, Martin settled at Poitiers, under the guidance of Bishop Hilary. He became a missionary in the provinces of Pannonia and Illyricum (now in the Balkan Peninsula), where he opposed Arianism. Forced out of Illyricum by the Arians, Martin went to Italy, first to Milan and then to the island of Gallinaria, off Albenga. In 360 he rejoined Hilary at Poitiers. Martin then founded a community of hermits at Ligugé, the first monastery in Gaul. In 371 he was made bishop of Tours, and outside that city he founded another monastery, Marmoutier, to which he withdrew whenever possible.

As bishop, Martin made Marmoutier a great monastic complex to which European ascetics were attracted and from which apostles spread Christianity throughout Gaul. He himself was an active missionary in Touraine and in the country districts where Christianity was as yet barely known. In 384/385 he took part in a conflict at the imperial court in Trier, France, to which the Roman emperor Magnus Maximus had summoned Bishop Priscillian of Ávila, Spain, and his followers. Although Martin opposed Priscillianism, a heretical doctrine renouncing all pleasures, he protested to Maximus against the killing of heretics and against civil interference in ecclesiastical matters. Priscillian was nevertheless executed, and Martin’s continued involvement with the case caused him to fall into disfavour with the Spanish bishops. During his lifetime, Martin acquired a reputation as a miracle worker, and he was one of the first nonmartyrs to be publicly venerated as a saint.

Source: Britannica

The Transfer from Malta to Gatchina of a Part of the Wood of the Life-Creating Cross of the Lord, the Philermia Icon of the Mother of God and the Right Hand of Saint John the Baptist (1799)

The Transfer from Malta to Gatchina of a Part of the Wood of the Life-Creating Cross of the Lord, together with the Philermia Icon of the Mother of God and the Right Hand of Saint John the Baptist was done in the year 1799. These holy things were preserved on the island of Malta by the Knights of the Catholic Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. In 1798, when the French seized the island, the Maltese knights turned for defence and protection to Russia. On 12 October 1799 they offered these ancient holy things to the emperor Paul I, who at this time was situated at Gatchina. In the autumn of 1799 the holy items were transferred to Peterburg and placed in the Winter Palace within the church in honour of the Image of the Saviour Not-Made-by-Hand. The feast for this event was established in 1800.

Philermia Icon

By ancient tradition, the Philermia Icon of the Mother of God was written by the holy Evangelist Luke. From Jerusalem it was transferred to Constantinople, where it was situated in the Blakhernae church. In the XIII Century it was taken from there by crusaders and from that time kept by the Knights of the Order of Saint John.

The right Hand of John the Baptist

The Orthodox Church celebrates the Synaxis of John the Baptist and the translation of his right hand from Antioch to Constantinople. According to the Church’ tradition, John the Forerunner of our Lord, was buried in the city of Sebaste, Samaria. Saint Luke the Evangelist wanting to move St John’s whole body to Antioch, was able to obtain and translate only his right hand. Historians Theodoret and Rufinus mention that the tomb of St. John the Baptist was desecrated in 362, during the Emperor Julian the Apostate reign, and a part of St. John relics burned. What remained intact from Saint’ body was taken to Jerusalem, then to Alexandria, and on May 27, 395 was placed in the church that bears saint John’ name.

The chronicle of John Skylitzes (a Byzantine historian of the eleventh century) states that the right hand of St. John the Baptist was moved from Antioch to Constantinople in 956 by Emperor Constantine the VII or Porphyrogenites (913-959) to be placed in one of the chapels of the Grand Palais, that is in the church of the Most Holy Theotokos of Peribleptos. At the end of the twelve century, the Russian archbishop Anthony of Novgorod who went on a pilgrimage to Constantinople, mentions in his writings among other treasures of this church, the right hand of St. John the Baptist. According to Du Cange in 1263, Othon of Ciconia attested the presence of a small piece from St. John’ right hand, in Citeaux Abbey, France. In 1261, Othon aceepted the refuge of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople Baldwin the II and in exchange for a gift, the emperor gave Othon this piece of relic of St John. In a testimony of the Spanish ambassador Clavijo dated 1404, it is mentioned that the holy hand was still in the church of the Theotokos – Peribleptos in Constantinople. After the fall of Constantinople (in 1453), the hand of St. John the Baptist along with other Church’ treasures were seized by the Turks and kept in the imperial treasury. In some Turkish fiscal archives from 1484 kept in Topkapi, it is noted that Sultan Bayezid the II (1481-1512) sent the hand of St. John to Hospitallers from Rhodes, (who occupied this island during the first quarter of the fourteenth century), in order to earn their favor. Later, the Hospitallers took the relics to the island of Malta, where they established their quarter...continue reading

John 20:19-31

19Then, the same day at evening, being the first day of the week, when the doors were shut where the disciples were assembled, for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood in the midst, and said to them, "Peace be with you."20When He had said this, He showed them His hands and His side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.21So Jesus said to them again, "Peace to you! As the Father has sent Me, I also send you."22 And when He had said this, He breathed on them, and said to them, "Receive the Holy Spirit. 23 If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained. 24 Now Thomas, called the Twin, one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came.25 The other disciples therefore said to him, "We have seen the Lord." So he said to them, "Unless I see in His hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and put my hand into His side, I will not believe." 26 And after eight days His disciples were again inside, and Thomas with them. Jesus came, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst, and said, "Peace to you!" 27 Then He said to Thomas, "Reach your finger here, and look at My hands; and reach your hand here, and put it into My side. Do not be unbelieving, but believing." 28 And Thomas answered and said to Him, "My Lord and my God!" 29 Jesus said to him, "Thomas, because you have seen Me, you have believed. Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed."30 And truly Jesus did many other signs in the presence of His disciples, which are not written in this book; 31 but these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in His name.

Galatians 1:11-19

11But I make known to you, brethren, that the gospel which was preached by me is not according to man. 12 For I neither received it from man, nor was I taught it, but it came through the revelation of Jesus Christ.13 For you have heard of my former conduct in Judaism, how I persecuted the church of God beyond measure and tried to destroy it.14 And I advanced in Judaism beyond many of my contemporaries in my own nation, being more exceedingly zealous for the traditions of my fathers.15 But when it pleased God, who separated me from my mother's womb and called me through His grace, 16 to reveal His Son in me, that I might preach Him among the Gentiles, I did not immediately confer with flesh and blood, 17 nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me; but I went to Arabia, and returned again to Damascus.18 Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to see Peter, and remained with him fifteen days. 19 But I saw none of the other apostles except James, the Lord's brother.

#ortohodxy#ancientfaith#orthodoxchristianity#originofchristianity#holyscriptures#gospel#spirituality#sacredtexts#wisdom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Methodius I, also spelled Methodios, (born 788/800, Syracuse, Sicily —died June 14, 847, Constantinople)was patriarch of Constantinople from 843 to 847…

Please follow link for full post

Art,Paintings,St. Methodius I,Nikephoros,Theophilos,RELIGIOUS ART,fine art,Religion,biography,History,John Skylitzes,Zaidan,Ancient,Leo,Theodora,Mythology,footnotes,

08 Works, Today, June 14th, is Saint Methodius I's day, his story in Paintings #165

#Icon#Bible#biography#History#Jesus#mythology#Paintings#religionart#Saints#Zaidan#footnote#fineart#Calvary#Christ

0 notes

Photo

A Byzantine army, besieging a citadel, deploys its trebuchet. Illustration from a 12th century Sicilian #manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories (Σύνοψις Ἱστοριῶν) of John Skylitzes (ca. 1040-1101).

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

i would love to know, are shield maidens real?

Honestly… from what we can tell the short, and long answer is: no.

At least not in the way that we would think of shield maidens. Nothing like an organisation, a dedicated warrior elite like the Berserkers, nor was it overly common for women to be on the front lines. Did this mean that women never fought?

No.

In fact we do have several sources in which the chronicler, John Skylitzes,noted, in shock, that the Norse dead included several armoured, and armed women. This was when the Varangians (Vikings from Russia) were defeated at the Siege of Dorolstolon.

There is also the Greenland Saga which noted that Leif Erikson’s half-sister Freydís Eiríksdóttir picked up a sword, when pregnant, and bare breasted, chased away a band of skrælingjar in Vineland.

As well as the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who noted that ranks of the Danes at the Battle of Brávellir. Though it should be noted that the even the historical events of Brávellir are disputed, with several historians claiming the historical accuracy of the event is “impossible to verify.”

And then we have Birka female Viking warrior. A skeleton, whose grave was found numerous weapons, two horses, and a strategic game board. Finally solid evidence right?

Well… again no. Judith Jesch, a Viking studies professor of the University of Nottingham was of the opinion that 1) the grave had been opened since 1887, which could have led to bones becoming mixed up, and 2) it was rather traditional of the vikings to bury such items with the wealthy, regardless if they were warriors or not. As there has been little mention of battle damage to the bones, something we have seen time and time again when excavating the graves of other warriors, and the large mess that the grave was subjected to, during its first unearthing, does cast a lot of doubt to the claim.

And then there is what we do know of Norse culture in and of itself. Like the majority of the world, women were expected to stay at home, and tend to the house hold affairs.

With all that said, were their women who fought? Undoubtedly.

Were they the norm? Or even encouraged? All evidence points to no.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its all about the Tent

The Significance of Kerbogha’s Tent

Kerbogha’s tent would have arrived by the time the council began. The Hystoria de via et recuperatione Antiochae atque Ierusolymarum states that the tent was sent to Bari by sea and left Antioch straight after the battle, on the 28th of June (D’Angelo, 2009: 89, chap. 13.57). The council opened at the beginning of October and three months would have been ample time for such a journey, especially given that the summer months were optimal for sailing (Eadmer, 1964: 108–14; Protospatarius, 1724: 197). John Pryor (1992: 117) has shown that commercial vessels were able to travel from the West to the Holy Land and back within a single sailing season (from March until late autumn), sometimes setting out as late as early August and still making it back to their home port before winter. Because of the prevailing winds in the Mediterranean, it was always slower to travel from East to West than vice versa. However, a journey from the Eastern Mediterranean to Italy could have been made comfortably within three months. In the 12th century, most voyages between the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and the ports of Italy took between four and eight weeks (Menache, 1996: 151, note 34). In the 9th century, Bernard the Monk travelled from Jaffa to Rome in 60 days (Wilkinson, 2002: 268), and Frederick II made a similar voyage in the summer of 1229, from Acre to Brindisi, in 40 days (Menache, 1996: 151). When the news of Bohemond’s great victory at Antioch reached Bari, together with the impressive tent that he had taken from his enemy, it must have caused excitement that would have been heightened by the arrival of Urban II, the instigator of the crusade. It is easy and logical to imagine that the tent would have been displayed in the church during and after the council. Eadmer tells us that the council took place ‘before the body of St Nicholas’, which might imply that it was held in the crypt, but that is impossible (Eadmer, 1964: 108–14). The crypt is nowhere near large enough to accommodate all the delegates, who must have numbered at least 200. Probably the discussions were held in the upper church, begun nine years earlier. Although the structure may have been in place, it is doubtful that the church was much more than a shell. All additional ornament would have been welcome. Although we have no evidence of how the tent was used in Bari, it is interesting to speculate. Perhaps the tent was erected in the space of the nave or outside the church, in order to provide a temporary shelter for the council. Another possibility is that it was cut up and used as carpeting or wall hangings within the half-finished building.

The symbolic value of Bohemond’s donation can be contextualised with other examples of tents being used as gifts. During the crusaders’ stay in Constantinople in June of 1097, before they travelled into the Holy Land, they were required to pay homage to the emperor. Bohemond’s nephew Tancred was more reluctant to comply than the others, but did so, begrudgingly. After he had sworn the oath of allegiance, Emperor Alexius offered him a gift of his choice, expecting that Tancred would ask for gold or something of monetary value. Instead, Tancred requested the emperor’s tent, despite the fact that it was cumbersome, requiring 20 camels to move, and would have been a hindrance to Tancred on the crusade. Alexius was very angry and refused. The tent was perceived to be akin to the emperor’s palace, and the request was seen as symbolic of Tancred’s ambition to usurp the emperor, who stated that the tent was part of his insignia and responded, ‘he desires nothing other than my palace, which is unique in the world. What more can he ask except to take the diadem off my head and place it on his own?’ (Ralph of Caen, 2005: chap. 18). A second illuminating parallel comes from a century later. During the Battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212, King Alfonso VIII of Castile captured the tent of the Almohad caliph, al-Nasir. Alfonso donated part of the tent to the Abbey of Las Huelgas de Burgos and the other part to Pope Innocent III, along with the caliph’s lance, standard and a letter describing the battle (Ali-de-Unzaga, 2014). The pope ordered that the letter be read publicly in Rome, and the standard was hung in St Peter’s Basilica (O’Callaghan, 2003: 72). These two examples demonstrate the significance of the tent in medieval culture as highly symbolic of kingship. The Spanish example also shows the importance of donations to churches. It seems likely that the arrival of Kerbogha’s tent in Bari would have been similar to the arrival of al-Nasir’s tent in Rome: it would have been accompanied by a description of Bohemond’s victory that would have been read aloud during the council, in the presence of the pope, and the tent itself would have been displayed in the church.

Figure 7

The Fall of Antioch in 969 from the Chronicle of John Skylitzes, cod. Vitr. 26–2, fol. 153, Madrid National Library. By Unknown, 12th/13th century author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/81/Fall_of_Antioch_in_969.png (Last accessed 1 May 2018).

What Did Kerbogha’s Tent Look Like?

Frustratingly for art historians, Fulcher of Chartres and Albert of Aachen tell us only that the tent was an impressive, large, fairly complex structure and that at least part of it was made of multicoloured silk. Therefore, we must look at examples of other medieval tents to attempt a reconstruction. Most tents in the central Middle Ages seem to have been circular bell tents, with a pole through the centre. Seljuq tents like Kerbogha’s were usually domed pavilions of this type (Redford, 2012). This kind of tent can be seen in multiple images in the Madrid Skylitzes manuscript (Codex Matrit Bib. Nat. Vitr. 26.2), which is an illuminated copy of a Byzantine chronicle, full of military scenes, produced in the Sicilian royal chancery during the reign of King Roger II (Boeck, 2015; Cavallo, 1982: 35–6). The manuscript depicts 33 circular bell tents, all decorated with curved bands of ornament, either at the top, bottom or halfway up the sides (Figure 7). Both Byzantine and Arab tents are represented, and although the Arab tents are slightly more ornate, there is no difference between the two (Mullett, 2013: 277). The tents of prominent Islamic military leaders like Kerbogha were richly decorated with animals, ornamental designs and sometimes figurative and narrative scenes (Golombek, 1988: 31–2). Both Byzantine and Arab tents were sometimes embroidered with inscriptions, and sometimes with poetry or good wishes for the owner (Mullett, 2013: 277). Jeffrey Anderson and Michael Jeffreys (1994) have suggested that short poems were sometimes embroidered onto tents. We have two excellent examples of Arabic and pseudo-Arabic inscriptions on circular tents, both from 13th century manuscripts. Al Hariri’s Maqamat (St Petersburg Institute for Oriental Studies ms c-23, folio 43b), painted in Baghdad in the 1220s, depicts a pilgrimage scene with two inscribed tents (Figure 8). The tent on the right has an inscription running around the top of the tent, where the roof joins the side. The tent on the left has a pseudo-inscription in the same position. Another example can be seen in Alfonso X of Castile’s Book of Games, which features a scene in which two figures play chess within a tent inscribed with a band of Arabic. Therefore, it is entirely plausible that Kerbogha’s tent (or part of the complex structure that made up the ‘tent city’) was circular and that the hem of the fabric was decorated with a pseudo-Arabic motif, like the one we find on the semi-circular mosaic pavement at San Nicola.

https://olh.openlibhums.org/articles/10.16995/olh.252/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cataphracts: the heavy cavalry

Byzantine horseriders (kataphraktoi) are charging. Chronicle of John Skylitzes, XIVth century

In the ancient world, the term cataphract was used by Greek and Roman sources to describe heavily armored cavalry used by Seleucid, Parthian, Sassanid, and Roman armies. The modern interpretation of these units typically takes the form of warriors armored spectacularly from head to toe, equipped with full horse armor and armed with a long pike and other weapons.

The term has also been applied by modern authors to describe apparently similar cavalry used by other peoples of western, central, and eastern Asia, even though the use of this term in ancient sources was originally limited to the nations described above.

Something interesting about these soldiers is that many scholars consider them as a possible cause of the increase on Western Roman Empire’s taxes, which ultimately was one of the multiple reasons for its fall.

Historical re-enactment of a Sassanid-era cataphract, complete with a full set of scale armor for the horse

58 notes

·

View notes