#theophano

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Theophano?

Hi! I'm not sure what you mean to ask, so I'm just going take it as an opportunity to talk about Theophano and her life.

Theophano was a Byzantine empress in the second half of the 10th century. She was the daughter-in-law of Constantine VII; wife of Romanos II and Nikephoros II Phokas; lover of John I Tzimiskes; and mother of Basil II and Constantine VIII.

She was famed for her extraordinary beauty, with chronicles hailing her as a "miracle of nature" who surpassed all other women of her age.

She was born to a family of reportedly low birth, with Skylitzes and Leo the Deacon both emphasizing her obscure origins. The former also claimed that Theophano's father was an innkeeper, and while we don't know if this is true or exaggerated, given the background of some former empresses (eg: Theodora), it's certainly plausible. We know next to nothing about her childhood, although she was probably close to her mother, who she may have brought to the palace and who was later exiled along with, although separately from, her daughter.

Theophano met Romanos, the heir of Emperor Constantine VII, as a teenager. The young prince seems to have become infatuated by her and decided to marry her in around 956, accordingly forcing a fait accompli on his family. It's possible that the imperial dynasty may have attempted to invent a noble lineage for Theophano to circumvent the controversy.

Theophano adopted her name after her marriage, having previously been known as Anastaso. She was trained in her duties as a member of the royal family, serving her apprenticeship as junior Augusta under the tutelage of her experienced mother-in-law Helena Lekapena. Both empresses were prominent in imperial ceremonies during Constantine’s reign, particularly during the reception of Olga of Kiev.

Romanos II came to the throne on November 959. At least one chronicle accused him and Theophano of conspiring together to poison her father-in-law Constantine and hasten their own ascent to power, although no evidence suggests that the former emperor died of poison or any kind of foul play.

During Romanos's very brief reign, he seems to have played little role in governance but instead entrusted administration to the eunuch Joseph Bringas. Most historians believe that Theophano was very influential during that time, with Romanos relying on her for advice and support. She certainly participated in political intrigue, supplanting the much more established and well-connected dowager empress, and successfully convinced Romanos to forcibly exile all his sisters to convents. This may suggest that she had less-then-cordial relations with her in-laws. More strikingly, it demonstrates that despite her youth and origins, Theophano succeeded in removing any other candidate of potential influence around Romanos, establishing herself as the dominant force at court. It's tempting to speculate what further role she might have played had her husband lived longer, but I suppose we’ll never know.

During their marriage, she and Romanos had four known children together: Helena, Basil, Constantine and Anna.

Romanos died prematurely in 963, after a short reign of less than three-and-a-half years. Theophano was once again rumored to have poisoned him, although this is extremely unlikely: as a favored and influential young empress, she had nothing to gain everything to lose from such an action. Moreover, she had given birth to her youngest child just a few days prior and was still in confinement, making it logistically improbable for her to have orchestrated such a conspiracy, with all the variables it entailed.

During her sons’ minority, Theophano was appointed as regent to the throne on the authority of the senate and patriarch. During that time, Skylitzes claimed that she was responsible for poisoning Stephen, son of Romanos Lekapenos, a possible contender for the throne who had been in exile and died suddenly on Easter Sunday. If this is true, it would have been a political act to secure her sons’ positions against possible threats, although the veracity of the accusation is unknown.

Unfortunately, Theophano’s regency was destined to be a short one. While one source asserted that she was capable of handling political affairs herself, and that she may not have wished to remarry, circumstances seemed to have forced/enabled her to choose otherwise.

At the time of Romanos's death, there was bad blood between Bringas, who remained administer of the empire, and Nikephoros Phokas, a renowned general of the army. The latter decided to seize the throne, probably due to the persuasion of his supporters rather than his own inclination. He was proclaimed Emperor by the army and was bound by an oath not to conspire against the rule of the young emperors. However, Bringas relentlessly plotted against him, attempting to deprive him of the position and offering the crown to someone else of his choosing.

During this factional struggle, Theophano decided to back Nikephoros, probably recognizing that the local and military support he possessed would be beneficial for her sons. She provided him with required legitimacy and was instrumental in his ascension to power: according to Zonaras, it was on her orders that he came to Constantipole to celebrate his triumph in April 963. Skylitzes even reports that they were lovers, and that Nikephoros desired the throne due to his infatuation with the beautiful young empress. Although it’s plausible the pair were in close communication with each other and may have decided to marry, an extra-marital actual affair is out of question given what we know of Nikephoros’s reticent and ascetical character. This was probably yet another way for chronicles to try and malign Theophano.

The situation was complicated by the fact that Nikephoros was godfather to one or both of Theophano’s sons, which would technically make the marriage uncanonical. In particular, the patriarch Polyeuktos was apparently very opposed to it. However, Nikephoros refused to be separated from Theophano, and the situation was resolved with the (probably invented) explanation that it was actually Nikephoros’s father, Bardas Phokas, who had been the young emperors’ godfather.

Theophano was a very influential empress during Nikephoros’s reign, with Leo the Deacon noting with disapproval that he “habitually granted Theophano more favours than were proper”. She was given profitable estates, was an active intercessor, and witnessed her two sons living in splendor and comfort in the palace. Considering what we know about her later life, she seems to have cultivated excellent relations with them.

However, relations between the imperial couple may have deteriorated, primarily from Theophano’s perspective, though chronicles aren’t unanimous on the details. Zonaros claimed that Nikephoros kept away from her due to his disinterest in sexual relations (though he appears to have still been devoted to her and honored her as an empress), while Skylitzes records that Theophano was the distancing partner. Some sources believed that Theophano may have grown concerned for the future and safety of her children, either at Nikephoros or his brother Leo’s hands.

All sources agree that Theophano and John Tzimiskes, the handsome and charismatic nephew of Nikephoros, became lovers in the late 1960s. Together, they conspired together to depose Nikephoros and place John on the throne, almost definitely with Theophano as empress. This was planned clandestinely in John’s home, and according to Leo the Deacon, Theophano received several warriors who she kept in a secret room near her quarters to enact the plan.

The Emperor’s assassination was eventually enacted on 10th December 969. Reportedly, Theophano pretended that she was heading out to instruct the Bulgarian princesses who had recently arrived as brides for her sons, and told Nikephoros to leave the bedchamber door open for her as she would close it when she returned. He did as she asked, making his customary devotions and falling asleep, which allowed the attackers to strike him unaware. John played a crucial role in the actual murder, striking Nikephoros on the head with his sword, though the coup de grace was delivered by one of the other conspirators, Leo Abalantes. While Theophano certainly played a vital role in the conspiracy, her direct participation in the murder itself is unknown. Later sources would dramatize her involvement: for example, Matthew of Edessa claimed that Theophano was the one who actually handed John the sword in order to carry out the murder.

Whatever her exact motivations, it’s clear that Theophano intended to orchestrate/support a new transfer of power just as she had with Nikephoros, becoming Empress for a third time. This was unprecedented across Byzantine history till that point, making her a singular figure.

However, things didn’t go as planned. John does seem to have intended to marry Theophano, and, after promising to ensure the safety and status of Romanos’ young sons as co-emperors, gained local support. However, when he went to St Sophia to be crowned, the patriarch refused him entry and presented him with three conditions: Theophano had to be banished from the palace and Constantinople, the murderer of Nikephoros had to be dealt with, and the measures taken against the church by Nikephoros had to be revoked. John, who keen to establish his own position and absolve himself from any blame, agreed or was forced to agree to these demands.

Theophano was thus sentenced to exile to the island of Prote or Prokonnesos. She didn’t accept her fate quietly: according to Skylitzes, she actually managed to escape from Prokonnesos and reappeared in the capital Constantipole, seeking refuge in the Hagia Sophia. However, she was forcibly removed by Basil the Nothos, who sent her to a newly created monastery of Damideia in distant Armenia. Before this, she was granted the request of an audience with the Emperor and her former lover John, which was not peaceful. Theophano reportedly “insulted first the emperor and then Basil [her son], calling him a Scythian and barbarian and hitting him on the jaw with her fists”. Her activities during her years-long exile are otherwise unknown.

After John’s death in January 1976, Theophano’s sons recalled their mother to the palace. She resumed her rightful position as empress, and since her elder son Basil never married, she would have remained the senior Augusta and most important imperial woman throughout her life.

Georgian sources indicate that Theophano also resumed her role as a prominent political figure, directing negotiations to broker an alliance with the Georgian overlord David of Taiq to counter a revolt by the general Bardas Skleros against her sons. She was also a generous patron and seems to have been partially responsible for supporting the foundation of the ‘Iviron’ monastery on Mt Athos reserved for monks of Georgian nationality.

However, Theophano vanishes from historical records after 978. It’s unknown if she died, retired, or if evidence for her activities has simply been lost across time.

All in all, Theophano seems to have been a fascinating woman who lived a full and sensational life. In many ways, she still remains a question mark, as very few primary sources survive to document the reigns of Romanos, Nikephoros, or the early years of her sons in detail. The majority of her daily activities, motivations, and even her ultimate fate, all remain unknown. But while this could have enhanced the effect of intrigue that already surrounds her, it seems to have had the opposite effect. Despite her controversial career, colourful romantic life, recorded influence over the court and affairs of state, and undeniable impact on the trajectory of the Byzantine Empire, Theophano remains a frustratingly unknown and often forgotten figure in most general histories of the dynasty.

She is also one of the most viciously maligned women in Byzantine history, vilified and scapegoated by contemporaries and historians as a wicked seductress, decadent intriguer, and violent murderess. Ultimately, we'll never know if Theophano was motivated by survival, desire, ambition, a combination of the above, or something else altogether. What we do know, however, is that she seems to have been a particularly strong-willed individual capable of navigating manifold realms of power despite not being born into it, and surviving the turbulent reigns of no less than six emperors. We can also appreciate how, in many ways, it was Theophano who seems to have gotten the last laugh: she outlived all her opponents and played a vital role in safeguarding the rights of her eldest son Basil II, who would go on to become the longest-ruling Roman Emperor.

In conclusion - she was fantastic and I love her.

References:

Lynda Garland, Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD: 527-1204

Anthony Kaldellis, Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade

John Ash, A Byzantine Journey

#ask#theophano#byzantine history#byzantine empire#women in history#my post#10th century#romanos ii#nikephoros ii phokas#basil ii#John I Tzimiskes#Byzantium#empress theophano

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's always a little deflating to watch or read something and it's clear the author has read exactly the same posts, or Wikipedia articles, as you

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can't stop myself from putting here something from my Real Life Real Work again: just look, what have I found right now in some Church Slavic manuscript from the late 13th/beginning of the 14th century:

Just look at these two charming boys embracing each other!

Sometimes I really like my work, I really do.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

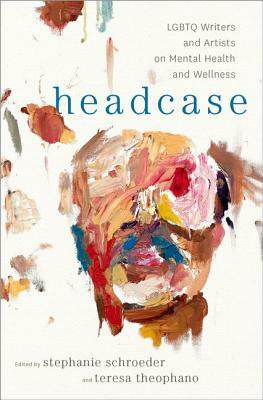

Headcase ed. Stephanie Schroeder; Teresa Theophano Headcase is a groundbreaking collection of personal reflections and artistic representations illustrating the intersection of mental wellness, illness, and LGBTQ identity, as well as the lasting impact of historical views equating queer and trans identity with mental illness. View the full summary and rep info on wordpress!

#Stephanie Schroeder#Teresa Theophano#bookblr#daily book#gay#lesbian#mental illness#mlm#neurodiverse rep#mental health rep#poc rep#queer#queer rep#transgender#wlw#adult books#anthology#essays#female protagonist#health#lgbt nonfiction#lgbtqia#male protagonist#mental health#nonfiction#Headcase

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Damn this person is married to Leoni

i think some of you pepole need to think about what you are saying

#that's the only hellenic witch i know#okay it's also theophano and kypriani#and the witches of Smyrna ig#btw if you're greek and aren't watching the witch season 2#wrf are you doing with your life

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcase: LGBTQ Writers and Artists on Mental Health and Wellness, edited by Stephanie Schroeder and Teresa Theophano

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Before queerness was seen as an identity it was considered a disease, given entries in the DSM, and used as an excuse to detain and "cure" people of perceived deviance. Even after revisions to diagnostic practices, both past and present traumas contribute to high rates of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and other mental illnesses among LGBTQ populations. Thirty-seven artists, writers, poets, psychologists and more lend their voices to this collection, exploring their personal experiences with queerness and mental health, whether related to their identity or otherwise.

This collection wasn't bad, but I feel that it would have the most value to an ally who wants to understand and support queer people in their community, or perhaps a LGBTQ person who isn't very familiar with the history. Most of what it covered were things I already knew about, so my reading experience was more emotionally exhausting than illuminating. There were some pieces that were very interesting to me though, such as Fidelindo Lam's contrast of his identity as a gay man in the Philippines versus how we understand gay identity in the United States, as well as the stories that sought to share personal accounts as opposed to arguing why therapists should do this or that.

I was pleased by how diverse the contributors were. It's skewed towards the US and UK, but the collection features racial diversity as well as a full spectrum of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and non-binary individuals. It's also very accessible to people without a background in psychology(my own consists of a single 100-level course). A couple of the chapters get a bit dense, but I was able to follow the argument without needing google as a reference. All in all, I'd recommend this primarily to people who work in or engage with mental health support systems and would like to learn more about supporting LGBTQ populations. It might also have strong appeal to LGBTQ people who are looking to learn more about queer history as it relates to mental health struggles.

#books#book review#headcase#Headcase: LGBTQ Writers and Artists on Mental Health and Wellness#stephanie schroeder#teresa theophano#lgbtq#mental health#lgbtq history

1 note

·

View note

Text

+++🙏🏻God Bless🕊️+++

Blessed Theophania of Byzantium, Empress

MEMORIAL DAY DECEMBER 29

Blessed Tsarina Theophania (Theophano), the first wife of Emperor Leo VI the Wise (886-911). According to slander, she and her husband, then still the heir to the throne, were imprisoned for three years. After gaining her freedom, she spent her life in prayer and fasting. Her meekness, mercy, and heartfelt contrition for her sins made her name famous among her fellow citizens. Theophania died in 893 or 894. The relics of Blessed Theophania are kept in St. George's Cathedral in one of Istanbul's Fanare districts.

💫International Orthodox Art Corporation Andcross May the blessing of the Lord be upon you!

#orthodox christmas#orthodox icon#orthodoxia#orthodox church#orthodox christian#russian orthodox#orthodox#greek orthodox#iconofaday#jesus

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John I Tzimiskes

John I Tzimiskes was Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976 CE. Although he took the throne by murdering his predecessor Nikephoros II Phokas, John was a popular emperor. A skilled general and a competent politician, he is known for expanding Byzantium's borders to the Danube River in the west and further into Syria in the east.

Rise to Power

John was related to the landed military elite families of Byzantine Anatolia, including the powerful Phokas and Kourkouas families. He was married to a woman from the Skleros family, who died sometime before 969 CE. After John's uncle, Nikephoros Phokas, took command of the Byzantine armies in 955 CE, he gave a forward command appointment to John. John was described as a short but handsome general. He led multiple armies against the forces of Sayf al-Dawla (r. 945-967 CE), the powerful Emir of Aleppo, under Nikephoros' overall command. He was known for an aggressive style of command and, like Nikephoros himself, he was a highly successful general.

John was among the troops that proclaimed Nikephoros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE) emperor in 963 CE. Nikephoros appointed John domestikos, or commander, of the East. John was one of the main commanders under Nikephoros in Cilicia and Syria, but after 965 CE Nikephoros distrusted him, stripped him of his titles, and placed him under house arrest.

On the night of December 10-11, 969 CE, John broke into the imperial palace with inside help and murdered Nikephoros with his co-conspirators. John immediately summoned Basil Lekapenos, the parakoimomenos, or director of the palace, to help secure John as the new emperor. By the morning, John had been crowned co-emperor with the young princes of the Macedonian Dynasty, the future Basil II (r. 976-1025 CE) and Constantine VIII (r. 1025-1028 CE). John prevented any looting from taking place following the coup, and other members of the Phokas family were placed under arrest and exiled. The fact that Nikephoros was already dead and that he was so unpopular allowed John to be accepted as emperor without any public outcry.

The Patriarch of Constantinople, Polyeuktos, agreed to crown John emperor in exchange for him canceling Nikephoros' decrees about the Church and blaming Empress Theophano, the mother of Basil and Constantine and widow of Romanos II (r. 959-963 CE) and Nikephoros, for instigating the murder of Nikephoros. It was even alleged that Theophano had had an affair with John before Nikephoros' murder. Theophano was then exiled by Basil the parakoimomenos. After being crowned, John married one of Romanos II's (r. 959-963 CE) sisters, Theodora, connecting him to the reigning Macedonian Dynasty.

Continue reading...

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@wanderer-on-the-steppe, yes, he sings to me right now near to my window, my Beloved Soul-Mate! I don't know his species (or even, whether it is he or she), because I have never seen him properly, only some shadow flying between our buildings.

Just look into his dark eyes, so unimaginably beautiful, sad and playful at the same time!

…

christine.c.w

#śliczny zwierz#bats#all mysterious and beautiful in the first picture#and cute and fluffy in the second :)#theophano's soul mate

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

OK, commonly I'm not putting here things from my real-live-real-work, but the Medieval Eastern Slavic Artist, who made illuminations to the manuscript, I'm currently working with, was so fond of dragons, that I couldn't stop myself. And I'm rarely so impressed with all the beauty, which has been suddenly revealed to my eyes after opening some PDF file.

@wanderer-on-the-steppe, something special for you from theophan-o's world.

Bohunku, don't be jealous, it's, after all, part of your own world too.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (November 20)

Saint Bernward served as the thirteenth Bishop of Hildesheim in Germany from 993 until his death in 1022.

His grandfather was Athelbero, Count Palatine of Saxony. After having lost his parents, Bernward was sent to live with his uncle Volkmar, who was the Bishop of Utrecht.

His uncle enlisted the assistance of Thangmar, the pious and well-educated director of the cathedral school at Heidelberg, to help with Bernward's education.

Under the instruction of Thangmar, Bernward made rapid progress in Christian piety as well as in the sciences.

He became very proficient in mathematics, painting, architecture, and particularly in the manufacture of ecclesiastical vessels and ornaments made of silver and gold.

Bernward completed his studies at Mainz, where he was then ordained a priest.

In lieu of being placed in the diocese of his uncle, Bishop Volkmar, he chose to remain near his grandfather Athelbero to comfort him in his old age.

Upon his grandfather’s death in 987, he became chaplain in the imperial court.

Empress-Regent Theophano quickly appointed him to be tutor of her son Otto III, who was only six years old at the time.

Bernward remained at the imperial court until 993, when he was elected Bishop of Hildesheim.

A man of extraordinary piety, he was deeply devoted to prayer as well as the practice of mortification.

His knowledge and practice of the arts were employed generously in the service of the Church.

Shortly before his death on 20 November 1022, he was vested in the Benedictine habit.

He was canonized by Pope Celestine III on 8 January 1193.

One of the most famous examples of Bernward's work is a monumental set of cast bronze doors known as the Bernward doors.

Bernward doors are now installed at St. Mary's Cathedral, which are sculpted with scenes of the Fall of Man (Adam and Eve) and the Salvation of Man (Life of Christ).

Bernward was also instrumental in the construction of the early Romanesque Michaelskirche.

St. Michael's Church was completed after Bernward's death, and he is buried in the western crypt.

These projects commissioned by Bernward are now considered as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

© The image is under the copyright of the Museum of Fine Arts

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wives and Daughters of Byzantine Emperors: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

Theodora, wife of Justinian I; age 35 when she married Justinian in 435 AD

Constantina, wife of Maurice; age 22 when she married Maurice in 582 AD

Eudokia, wife of Heraclius; age 30 when she married Heraclius in 610 AD

Fausta, wife of Constans II; age 12 when she married Constans in 642 AD

Maria of Amnia, wife of Constantine VI; age 18 when she married Constantine in 788 AD

Theodote, wife of Constantine VI; age 15 when she married Constantine in 795 AD

Euphrosyne, wife of Michael II; age 33 when she married Michael in 823 AD

Theodora, wife of Theophilos; age 15 when she married Theophilos in 830 AD

Eudokia Dekapolitissa, wife of Michael III; age 15 when she married Michael in 855 AD

Eudokia Ingerina, wife of Basil I; age 25 when she married Basil in 865 CE

Theophano Martinakia, wife of Leo VI; age 16/17 when she married Leo in 882/883 AD

Helena Lekapene, wife of Constantine VII; age 9 when she married Constantine in 919 AD

Theodora, wife of John I Tzimiskes; age 25 when she married John in 971 AD

Theophano, wife of Romanos II (and later Nikephoros II); age 14 when she married Romanos in 955 AD

Anna Porphyrogenita, daughter of Romanos II; age 27 when she married Vladimir in 990 AD

Zoe Porphyrogenita, wife of Romanos III (and later Michael IV & Constantine IX); age 50 when she married Romanos in 1028 AD

Eudokia Makrembolitissa, wife of Constantine X Doukas (and later Romanos IV Diogenes); age 19 when she married Constantine in 1049 AD

Maria of Alania, wife of Michael II Doukas (and later Nikephoros III Botaniates); age 12 when she married Michael in 1065 AD

Irene Doukaina, wife of Alexios I Komnenos; age 11 when she married Alexios in 1078 AD

Anna Komnene, wife of Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger; age 14 when she married Nikephoros in 1097 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Alexios I Komnenos; age 14/15 when she married Nikephoros Katakalon in 1099/1100 AD

Eudokia Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Michael Iasites in 1109 AD

Theodora Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Constantine Kourtikes in 1111 AD

Maria of Antioch, wife of Manuel I Komnenos; age 16 when she married Manuel in 1161 AD

Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera, wife of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Alexios in 1169 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Manuel I Komnenos; age 27 when she married Renier of Montferrat in 1179 AD

Anna of France, wife of Alexios II Komnenos (and later Andronikos Komnenos); age 9 when she married Alexios in 1180 AD

Eudokia Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 13 when she married Stefan Nemanjic in 1186 AD

Margaret of Hungary, wife of Isaac II Angelos; age 11 when she married Isaac in 1186 AD

Anna Komnene Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Isaac Komnenos Vatatzes in 1190 AD

Irene Angelina, daughter of Isaac II Angelos; age 16 when she married Philip of Swabia in 1197 AD

Philippa of Armenia, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 31 when she married Theodore in 1214 AD

Maria of Courtenay, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 15 when she married Theodore in 1219 AD

Maria Laskarina, daughter of Theodore I Laskaris; age 12 when she married Bela IV of Hungary in 1218 AD

Elena Asenina of Bulgaria, wife of Theodore II Laskaris; age 11 when she married Theodore in 1235 AD

Anna of Hohenstaufen, wife of John III Doukas Vatatzes; age 14 when she married John in 1244 AD

Theodora Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Michael in 1253 AD

Anna of Hungary, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Andronikos in 1273 AD

Eudokia Palaiologina, daughter of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 17 when she married John II Megas Komnenos in 1282 AD

Irene of Montferrat, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 10 when she married Andronikos in 1284 AD

Rita of Armenia, wife of Michael IX Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Michael in 1294 AD

Simonis Palaiologos, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 5 when she married Stefan Milutin in 1299 AD

Irene of Brunswick, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 25 when she married Andronikos in 1318 AD

Anna of Savoy, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Andronikos in 1326 AD

Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Basil of Trebizond in 1335 AD

Maria-Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 9 when she married Michael Asen IV of Bulgaria in 1336 AD

Theodora Kantakouzene, daughter of John VI Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Orhan Gazi in 1346 AD

Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos; age 13 when she married John in 1347 AD

Keratsa of Bulgaria, wife of Andronikos IV Palaiologos; age 14 when she married Andronikos in 1362 AD

Helena Dragas, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Manuel in 1392 AD

Anna of Moscow, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 21 when she married John in 1414 AD

Maria Komnene, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 23 when she married John in 1427 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Theodore II Palaiologos; age 14 when she married John II of Cyprus in 1442 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 15 when she married Lazar Brankovic in 1446 AD

Sophia Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 23 when she married Ivan III of Russia in 1472 AD

The average age at first marriage was 17 years old.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

@threshold-of-revelation, thank you for tagging me here! It's my first time to write such details about myself, but - let's try!

Last song I listened to: "Moja cygańska", from the record: Mirosław Czyżykiewicz & Witold Cisło PRETEKST LIVE (2018).

Currently watching: Rewatching Walt Disney's "Zorro" (1957–1961). Because I adore old, innocent fairy tales, but only these with a lot of horse-riding and sword-fighting:-)

Currently reading:

For work (because I have been asked to write a review of it): Ágnes Kriza, Depicting Orthodoxy in the Russian Middle Ages. The Novgorod Icon of Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2022 [= Oxford Studies in Byzantium].

Privately: Remigiusz Ryziński, Foucault w Warszawie, Warszawa 2017. Very interesting piece of non-fiction writing. The author claims, that Michel Foucault stayed in Warsaw in 1958, during the work on his Ph.D. dissertation Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (Folie et Déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, 1961) and was expelled from Poland by its communist government not for love affairs with Polish boys, but... because of the topic of his study (he was suspected to analyse Polish communist reality as an example of societal madness). Michel, Michel, what would you say seeing Poland nearly 70 years later?

Current obsession: Surprisingly, not so far away from the main topic of my blog: art and music devoted to the Zaporozhian (Ukrainian) Cossacks.

9 people you want to know better

Tagged by my lovely @hardboiledteacozy Here goes!

last song I listened to: "What Was I Made For?" from the Barbie movie for the weekly existential crisis. Also, anime ops for a good good dose of endorphins.

currently watching: Rewatching the first season of “Loki” before the new one drops. Also about to rewatch the “RomeoXJuliet” anime.

currently reading: Alternating between a book abt the history and production of anime and “The Pillars of the Earth” by Ken Follett (but I’m not crazy over it, not gonna lie…).

current obsession: I’m back on my bullshit with true-crime, weird history, and folk-horror podcasts; currently super addicted to the Mexican dark comedy streams “El Dollop” (The Dollop) and “Leyendas Legendarias” (Legendary Legends). Stupid fun stuff.

-

I’m gonna tag @siegeperilousgalahad , @jimikii, @theophan-o @greyselkie @sprawca @nerd-unity

Feel free to ask any questions or add your answers if you like. 👍🏻 These things are always fun to do/read! Now, fly my pretties!

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!!! I was reading this post of yours (for my research) and i'm truly wondering how did Byzantine princesses wanted to take a bath?? Do you have a post for that?

I don't but I managed to find a few pieces of information about the general habits of Byzantine bathing and grooming, and particularly that of the empresses and the princesses.

"The wealthy and noble women of the empire were concerned with their looks and Christianity cast no pall on the baths nor the sale of cosmetics and perfumes. (...) Byzantine gardens, therefore, had areas set aside for aromatic flowers from which could be distilled some of the more fragrant oils. (...) Mirrors, tweezers and similar hygiene equipment would have been commonplace in a Byzantine home. (...) Michael Psellos wrote that (Empress) Zoe turned her chambers into cosmetics laboratory in which she created cosmetics and ointments to preserve her beauty well into old age. (...) Byzantine women did not use as heavy cosmetics as their earlier Roman counterparts. (...) For eye liner and darkening eye brows and lashes, kohl was very popular."

Source: http://gretchenbrownauthor.com/2018/04/08/cleanliness-and-hygiene-among-the-byzantines/

"Women washed their hair in special fragranced solutions that naturally lightened it, including saffron, turmeric, fern roots and citrin-colored sandalwood and rhubarb. The cloths they wrapped their hair in were usually brushed with perfume. People made their own scents at home. Lotions and creams were made fresh from natural sources and had to be used in a few days. (...) There were many public baths; the Byzantines - even monks and nuns - bathed frequently. One was expected to bathe twice a week. (...) The Byzantines had a wide variety of cleaning products for bodies and clothes."

Source: https://www.pallasweb.com/deesis/daily-life-in-constantinople.html

"Byzantines in the capital city of Constantinople developed public baths similar to those found in Rome, and public bathing was a daily ritual for many. (...) Unlike the Romans, who used a lot of makeup and cosmetics, the Byzantines avoided heavy preparations for their skin. Instead, they developed rich perfumes using ingredients obtained in trade from China, India, and Persia, modern-day Iran. Perfume making was developed as an esteemed trade."

Sources:

Baltoyianni, Chryssanthi. "Byzantine Jewelry." Hellenic Ministry of Culture. http://www.culture.gr/2/22/225/22501/225013/e013intro.html (accessed on July 29, 2003).

Cosgrave, Bronwyn. The Complete History of Costume and Fashion: From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. New York: Checkmark Books, 2000.

"Let us now place ourselves in the second half of the 11th century, when a Byzantine princess arrives in Italy again; not in Rome but in Venice, although with the same nuptial purpose. This time she is Theodora Doukaina, daughter of Emperor Constantine X Doukas and Eudokia Makrembolitissa (the niece of Patriarch Michael I Cerularius) who is to marry Doge Domenico Selvo. (...) The Byzantine stravaganza of Theodora was reflected not only in the colossal retinue she led or the impressive tiara she wore at the ceremony (the one worn by her brother Michael VII, who had just inherited the imperial throne) but also in her own daily behaviour, which included such whims as bathing in the dew that his servants collected or – and here is what interests us – the refusal to touch food with her hands, so that she made use of a golden fork to prick the bites that her eunuchs had previously cut off."

Source: https://www.labrujulaverde.com/en/2020/06/how-two-byzantine-princesses-scandalized-europe-by-using-a-fork/

"While the Germans like Theophano, many of them thought her odd. The Byzantine empire was known for its luxurious, decadent ways, and Theophano was a product of that 'decadence'. She talked too much, she bathed every day, and, strangest of all, she used a two pronged utensil to bring food to her mouth (aka a fork), instead of eating with her hands like everyone else."

Source: http://www.thathistorynerd.com/2017/07/damn-girl-holy-roman-empress-theophano.html

Check here for a great link with detailed description of Byzantine public baths, how they worked and how they were taken

Peter Damian, the Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, wrote a chapter entitled "De Veneti ducis uxore quae prius nimium delicata, demum toto corpore computruit" ("Of the Venetian Doge's wife, whose body, after her excessive delicacy, entirely rotted away.") about an unnamed Byzantine princess whose manners he considered scandalously lavish and which brought to her a horrible death as a divine punishment. This woman has been mistakenly (since Damian died 1072) identified with Domenico Selvo's wife by later Venetian chroniclers (incl. Andrea Dandolo and Marino Sanuto the Younger) followed afterwards by various modern authors; however since the work in which Damianus' chapter is contained is dated ca 1059 it refers probably to Maria Argyropoulaina who had died a half century before.

From Wikipedia. Irrelevant but Maria Argyropoulaina might be the most modern Greek name I have seen in a medieval woman ever.

When, three days after the wedding, the new empress left her rooms to take her bath in the Palace of Magnaura, the court and the commonwealth gathered in queues behind her in the gardens. And when the empress passed with the servants who showed off the robes, the boxes with the perfumes, walking first, accompanied by three ladies of waiting who held apples decorated with pearls, as a symbol of erotic love, the commonwealth would cheer, the jesters of the court would make inappropriate jokes and the most important officers of the empire would escort the empress all the way to the entrance of the bath, where they waited for her to finish, and escorted her back to her bridal chambers.

Source: From The History of the Byzantine Empire by Charles Diehl, translated by me here.

They don't go into great detail as you see but I guess they are enough to give you an idea. Reminder to check the link I added above about the detailed description of the public baths - it is very interesting!

#history#middle ages#byzantine empire#byzantine culture#eastern roman empire#greek history#byzantine history#greek culture#anon#ask

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fredegund-Theophano-Alice Perrers pipeline is so real

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fun fact: Theophano, wife of Holy Roman emperor Otto, was resented by the emperor's courtiers for her "luxurious tastes", like demanding to take a bath daily and using "a golden double prong (ye olden fork basically) to bring food to her mouth", instead of eating with her hands. 😂

lol girl had hygiene and they all hated her for it

4 notes

·

View notes