25 ~ Bioarchaeologist ~ Medieval and early modern reenactor ~ Everyone just calls me Roman

Last active 3 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Brickwork details from the Fenâri Îsâ Mosque (formerly the Lips Monastery, dedicated in 908) in Istanbul Photos by Yasin Karabacak at the Hidden Face of Istanbul

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palazzo Contarini di Bovolo

Designed and built by Giovanni Candi in 1499, Giorgio Spavento later designed the famous spiral staircase located on the facade of the palace.

There are two stories about how and why the staircase was built: the first is that the owners of the palazzo, the Contarini family, left for vacation and simply gave the instructions to "build me a staircase" (Spavento might have been a bit of an overachiever). The second was that the staircase was built on the outside of the palace because towers were not permitted to be built in the city at the time of the construction of the main building. (Venice is built on the water so the poor bearing capacity of the soil leads to earthquakes, collapses and demolitions).

The original building was curious but not prestigious, tucked away in an obscure alley near the Piazza San Marco. After the wall protecting the small courtyard was brought down, Spavento was commissioned to create the staircase, which he did, using the model of the Byzantine scalar towers as inspiration. A series of overlapping loggias connect the floors to the airy staircase. The palace takes after a few different types of architecture and design. There are Renaissance, Byzantine and Gothic styles incorporated in and outside the building.

The name of the building: Contarini del Bovolo. Contarini was the name of the owners and "bovolo" means snail shell in the Venetian dialect. Sometimes the palace is simply referred to as the "snail house".

Around the base of the palazzo are numerous wellheads or "vere di pozzo". Most are much older than the building itself, dating back to the 13th century, and were incorporated into the structure. A few were made after the construction of the building though because they have the coat of arms of the family on them.

In 1949 the English director Orson Welles began filming a famous literary classic: Othello by William Shakespeare, whose first act was set in Venice. Throughout the movie, the famous spiral staircase was put on display many times.

As of 2016 (after some renovations) the staircase is accessible to the public for a small fee.

Sources:

https://web.archive.org/web/20111130111531/http://www.euro-poi.com/venice-bovolo-house-italy-383.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20060507133401/http://www.scalabovolo.org/bovolo2.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20110929112453/http://www.venice-sights.co.uk/Contarini_del_Bovolo.htm

https://www.visitvenezia.eu/en/venetianity/discover-venice/venice-and-its-%E2%80%98caskets--the-bell-towers-

https://www.venetoinside.com/hidden-treasures/post/the-othello-by-orson-welles-and-the-bovolo-stairs-in-venice/

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of a Youth, 1525, Jacopo Pontormo

https://www.wikiart.org/en/jacopo-pontormo/portrait-of-a-youth

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

A testament of Byzantine water management - New in history (6/?)

Aqueducts are truly fascinating witnesses from the past and they keep revealing their secrets. Recent research from the Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz (JGU) revealed some of these secrets. The research was done by Gül Sürmelihind. The Aqueduct of Valens (426 kilometres) provided water to Constantinople and started to operate in the fourth and fifth century. It was one of the longest water supply of the ancient world.

Research conducted on the carbonate deposits in the system of the aqueduct provided an archive of both archaeological developments and paleo-environmental conditions during the depositional period. Historical records prove that the aqueduct was used for at least 700 years, but the carbonate deposits in the system would suggest that it was only in use for 27 years. This implies that the aqueduct system mush have been cleaned of carbonate. The researchers presume this was done during regular campaigns. They also discovered that over 50 kilometres in the central system, there was a double-aqueduct. This might have been costly but it was practical to allow repairs and cleaning of carbonate to secure the water supply.

Check here the full research: x

240 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nomisma with John I Zimisces (obverse), 969-976, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

Byzantine Gold Coins The vast number of surviving Byzantine coins attests to the level of trade across the empire. Controlled and supervised by the emperor, the producers of coins took care to represent his authority and reflect his stature. Talented artists were recruited to engrave the dies (molds) used for the striking of coins. Emperors increasingly came to include their heirs and co-emperors on their coinage, as well as other family members or even earlier rulers. Coins were recognized, then as now, as small, portable works of art. With their inscriptions and images, Byzantine coins provide valuable documentation of historical events and a record of the physical appearance of the emperors. The coins shown here include the solidus, the basic gold coin of 24 karats; the tremissis, a gold coin of one-third the weight and value of the solidus; and the nomisma, which in the 10th century replaced the solidus as the standard gold coin. Size: Diameter: 2.3 cm (7/8 in.) Medium: gold

https://clevelandart.org/art/1968.61.a

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ceramic Bowl Inscribed with “‘Izz” (“Glory”), 12th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Islamic Art

H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Gift of Horace Havemeyer, 1948 Size: H. 4 11/16 in. (11.9 cm) Diam. 9 ¼ in. (23.5 cm) Wt. 18.8 oz. (533 g) Medium: Stonepaste; underglaze-painted, glazed (transparent colorless), luster-painted

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/450934

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

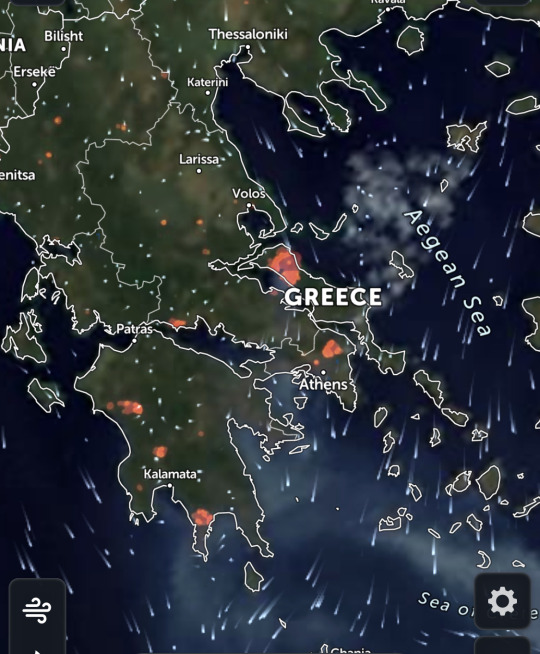

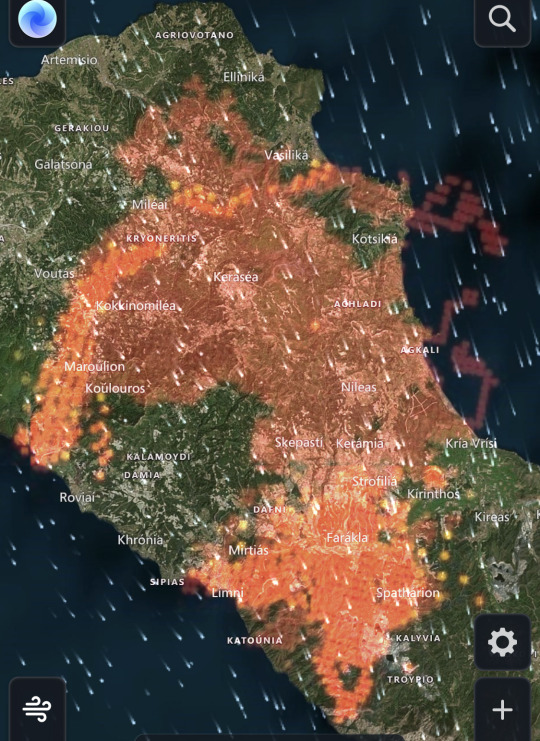

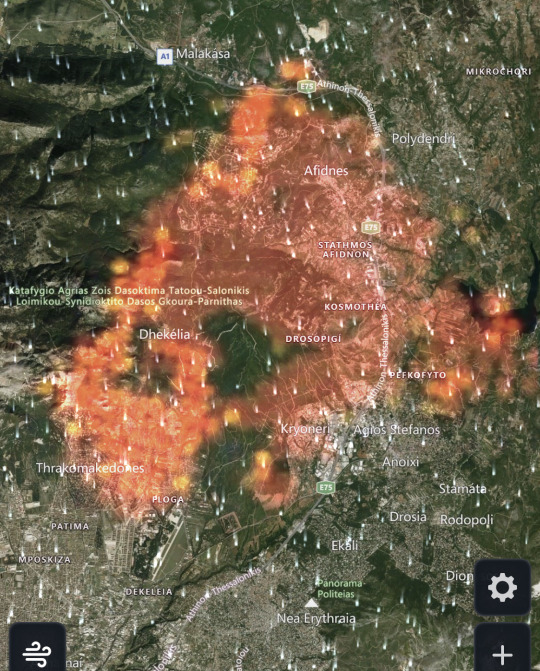

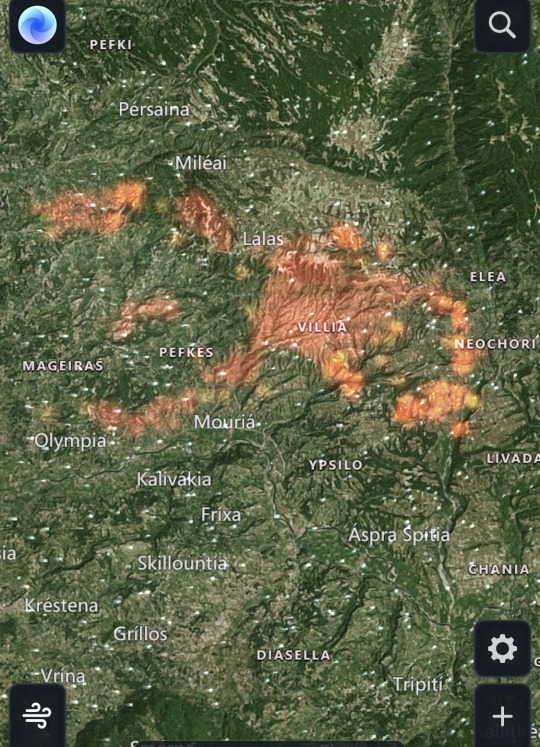

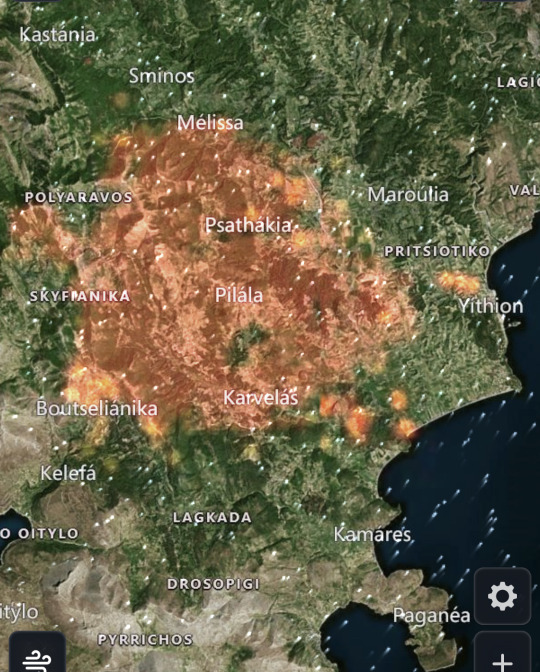

I found maybe the best satellite map site for fires, winds and rain. It is zoom.earth.

Here you can see in detail where and how big the fires are right now. Note the size of the fire in North Euboea and how many towns are threatened by the fires.

Here is the fire in Athens and Mount Parnitha. Note how close it is to the Wildlife Shelter of Parnitha (on the left). That is also where the grounds of the royal residences of Tatoi are.

The fire in Elis. Note how close it is to Ancient Olympia (left). This is from today and the fire was contained there eventually but the previous days the fire was even closer to the archaeological site.

And the fire in Mani. Note how close it is to the beautiful historical town of Gythion (Yithion) on the right.

But this in not just a matter of pretty towns and archaeological sites. Look at the number of towns where people had to abandon their homes. This is only what is burning right now, not what was burned all these days. And the winds are strong.

I also must say that no matter how bad a heatwave is and while climate change is definitely happening as we speak, this hellfire is not caused just by a heatwave. This is arson. The worst is that this is the deed of MANY arsonists. Right now, the police has caught or is chasing at least 4-5 arsonists. All sorts of dangerous equipment was found in the forests, magnifying glasses, oil, matches etc. Are all these people just crazy? Are they acting only on their own volition? Is there something bigger lurking behind? I hope time will tell. Time MUST tell.

The law needs to become a lot stricter with arson. Arson is knowing you will certainly kill flora, you will almost certainly kill animals and you will possibly kill humans, regardless if the firefighters manage to put out the fire before it causes any casualties. The intent is still there. Just saying.

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some trustworthy places to donate money to fighting the wildfires? I know of the Hellenic Institute but not much else. Thank you!

So far there are not many options, maybe because the immediate need is for volunteers to physically help fight the still expanding fires and probably more donations will start later.

There are two I found:

1. You can donate to the Red Cross Greece.

Transfer your donation to their account in the bank "Eurobank".

Their IBAN: GR26 0260 2400 0003 0020 1205 013

Their SWIFT code: ERBKGRAAXXX

In the reason box or whatever it is called, use the word "Πυρκαγιές" just like I write it here. Copy paste it. It means "Wildfires".

If you need more guidance call them at (+30) 210 36 09 825

2. The gamers / youtubers UNBOXHOLICS ( Sakis and Alekos Karpas, they are brothers) are doing a special livestream on twitch.tv to gather donations. Now you may ask, seriously??? A twitch by some gamers?! Yes, these guys are super legit. They are some of the most popular and straightforward Greek youtubers and I believe they can totally be trusted. They have done this before, for the fatal fires of Mati in 2017. The livestream begins today 6/8/2021 at 11.45 PM EEST (you 'll have to convert to your timezone). As long as there is a way to donate through twitch even if you are abroad and as long as the language isn't a problem, you don't have to worry whether your money will go to the right hands. Anyway, check them out and see.

This is their twitch link.

3. Avaaz. This is not a donation but please sign this campaign that all burned areas should be immediately reforested to their former state without any exception accepted. This is the link.

Hopefully there will be more donating platforms launching soon.

*PS: I found some random people launching gofundmes and stuff but I obviously can't vouch for them.

I thank you for your intention to offer help to those in need right now. You rock 💕

346 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Plaque: The Journey to Bethlehem, c. 1100-1120, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

This ivory plaque depicts Mary, Joseph, and one of his sons from a previous wife on their way to Bethlehem. The scene is set within an architectural frame that combines Byzantine decorative elements (such as the acanthus leaf column capitals) with Islamic architectural motifs (most notably, the distinctively rounded arches). The blending of Byzantine, Islamic, and Western iconographic elements and decorative motifs is typical for the art produced in the city of Amalfi, a prosperous merchant town near Naples in South Italy. Size: Overall: 16.3 x 11 x 1 cm (6 7/16 x 4 5/16 x 3/8 in.) Medium: ivory

https://clevelandart.org/art/1978.40

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Lady with a Drawing of Lucretia, 1531, Lorenzo Lotto

Medium: oil,canvas

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nomisma with Constantine IX Monomachus (obverse), 1042-1055, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

Byzantine Gold Coins The vast number of surviving Byzantine coins attests to the level of trade across the empire. Controlled and supervised by the emperor, the producers of coins took care to represent his authority and reflect his stature. Talented artists were recruited to engrave the dies (molds) used for the striking of coins. Emperors increasingly came to include their heirs and co-emperors on their coinage, as well as other family members or even earlier rulers. Coins were recognized, then as now, as small, portable works of art. With their inscriptions and images, Byzantine coins provide valuable documentation of historical events and a record of the physical appearance of the emperors. The coins shown here include the solidus, the basic gold coin of 24 karats; the tremissis, a gold coin of one-third the weight and value of the solidus; and the nomisma, which in the 10th century replaced the solidus as the standard gold coin. Size: Diameter: 2.9 cm (1 1/8 in.) Medium: gold

https://clevelandart.org/art/1964.424.a

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

St. Ursula, 1523, Hans Holbein the Younger

Medium: panel,tempera

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine Baked Cheesecake “melopita”

This week, I’ll be taking a look at a Byzantine baked cheesecake - that’s quick, simple, and very tasty! It seems to be based on an earlier Greek recipe for a baked cheesecake, but was adapted to suit the tastes of Medieval Byzantine elite cuisine!

youtube

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above!

Ingredients 500g ricotta cheese (or myzithra, anthotyro cheese) 150g honey 3 eggs flour cinnamon butter (to grease baking tin)

Method 1 - Whisk Ingredients To begin with, we need to place our cheese in a bowl. I used ricotta here, because it has a good texture and is widely available, but other soft Greek cheeses would work well - such as myzithra or anthotyro. Into this, pour 150g of honey, and whisk it well. Crack an egg one at a time into the bowl, whisking it until it’s well combined before adding two more. Chicken eggs would have been used in this period, along with wildfowl and pidgeon eggs - so you can use these here too if you happen to have any. Finally, to thicken the mixture up a little, add a tablespoon or two into the mixture, whisking together as you go. I used plain wheat flour, which has a lower bran content than what would have been widely available in Late Antiquity, but it results in a smoother, finer cake when you’re finished.

2 - Bake Cheesecake Preheat your oven to 180C/356F while you pour your mixture into a tin.

Make sure you grease your baking tin before you pour in your batter. Your batter should be silky smooth as you’re pouring it in. Smooth out the top, and place it into the middle of your preheated oven. Let this bake for about 40-50 minutes, depending on your oven. It should be done when the top of it has turned a lovely golden colour, and the centre of the cake doesn’t jiggle when you wiggle it. The top of it will slowly fall down while it’s cooling, but don’t worry - that’s what’s meant to happen!

3 - Decorate Cheesecake Let the cake cool for about 5 minutes in the pan before you try and take it out and top it. When it’s cooled slightly, pour some more honey over the top, along with some ground cinnamon. Cinnamon would have been used by the elites of Byzantine society, as they would have had more access to expensive spices than Western Europe (given the Byzantine Empire’s proximity to the spice trade routes of the Near and Middle East). In any case, serve up warm and dig in!

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ancient and Noble Art of Silk

Silk has a millennial history. It is said that the birth of the silkworm is attributed to the Chinese Empress Xi Ling Shi, but probably the silk was known in China as early as 3000 BC. The silken robes that were reserved for Chinese emperors became part of the wardrobe of the richer social class, becoming a coveted luxury item that was extended to the areas reached by the Chinese merchants for the qualities of lightness and beauty.

In the mid-6th century AD, two monks, with the support of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, successfully smuggled silkworm eggs into the Byzantine Empire, which led to the establishment of an indigenous Byzantine silk industry. This acquisition of silk worms from China allowed the Byzantines to have a monopoly of silk and from the tenth to the eleventh centuries, sericulture was practiced in Byzantine territory.

At the time, Southern Italy’s Calabria was part of the Byzantine Empire. Between the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century, Calabria was one of the first regions of Italy to introduce silk production to Europe and what happened next is that Italy became the largest producer of European silk - the city of Catanzaro, in Calabria, was particularly renowned for its silk.

According to historians, around 1050 the theme of Calabria had 24,000, mulberry trees cultivated for their foliage, and their number tended to expand. While the cultivation of mulberry was moving first steps in other regions of Italy, silk made in Calabria reached the peak of 50% of the whole Italian/European production. As the cultivation of mulberry was difficult in Northern and Continental Europe, merchants and operators used to purchase in Calabria raw materials in order to finish the products and resell them for a better price.

In particular, the silk of Catanzaro supplied almost all of Europe and was sold in large market fairs to Spanish, Venetian, Genoese, Florentine and Dutch merchants. Catanzaro became the lace capital of Europe with a large silkworm breeding facility that produced all the laces and linens used in the Vatican. From Southern Italy, the cultivation of the silkworm and silk processing world spread first in other regions of Italy and then in the rest of Europe.

The breeding of silkworms was an important income support to the agricultural economy and the production and trade of fabrics – together with that of wool it was a very profitable industry that gave power and wealth to the corporations who practiced it.

In 1466, King Louis XI decided to develop a national silk industry in Lyon and called a large number of Italian workers, mainly from Calabria. The fame of the master weavers of Catanzaro spread throughout France and they were invited to Lyon in order to teach the techniques of weaving.

In 1470, one of these weavers, known in France as Jean Le Calabrais, introduced a new kind of loom which was able to work the yarns faster and more precisely. Some centuries later, the famous Jacquard machine evolved from this approach.

In 1519 Emperor Charles V formally recognized the growth of the industry of Catanzaro by allowing the city to establish a consulate of the silk craft, charged with regulating and check in the various stages of a production that flourished throughout the sixteenth century. At the moment of the creation of its guild, the city declared that it had over 500 looms. By 1660, when the town had about 16,000 inhabitants, its silk industry kept 1,000 looms, and at least 5,000 people, busy.

After the invention of the Jacquard machine, the Italian record was then disputed by the region of Lyon in France. During the 17th century silk production in Calabria begin to suffer by the strong competition of new-raising competitors in Italian Peninsula and Europe (France), but also the increasing import from Ottoman Empire and Persia.

The rediscovery of an ancient tradition

Today, in San Floro, a few kilometers from Catanzaro, a newly-created cooperative called Nido di Seta has rediscovered the ancient silk tradition. The young founders, who came back to Calabria after studying abroad, chose to breed their silkworms on 3,500 Kokuso mulberry trees, rented out by the municipality.

Their production and their processing of silk is of great historical and cultural significance, so much so as to have also led to the birth of a dedicated Silk Museum, set in the beautiful surroundings of an ancient XV century castle.

207 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Livia da Porto Thiene and her Daughter Porzia, 1552, Paolo Veronese

Medium: oil,canvas

https://www.wikiart.org/en/paolo-veronese/livia-da-porto-thiene-and-her-daughter-porzia-1552

11 notes

·

View notes