#John F. Kennedy's grave

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Arlington National Cemetery was established on June 15, 1864, when 200 acres (0.81 km2) around Arlington Mansion (formerly owned by Confederate General Robert E. Lee) are officially set aside as a military cemetery by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.

#Arlington National Cemetery#established#15 June 1864#160th anniversary#US history#Virginia#John F. Kennedy's grave#Robert Kennedy's grave#Arlington Mansion#architecture#lawn#tree#tourist attraction#landmark#summer 2009#original photography#vacation#travel#cityscape#landscape#USA#flora#nature

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna52723602

#nick beef#lee harvey oswald#john f kennedy#jfk assassination#grave goods#the more you know#cemetery

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.

- John F. Kennedy

#support for palestine#gaza solidarity encampment#student protests#anti genocide#palestine#palestinians#gaza#genocide#mass graves#mass murder#israeli apartheid#israeli occupation#war crimes#idf terrorists#iof terrorism#free palestine#free gaza#justice#icj#icc#right wing extremism#settler colonialism#zionism#john f kennedy#end genocide#end the occupation#us complicity#us weapons#childrens holocaust#civilian deaths

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Washington DC - The Federal Core

#traveling#reisen#usa#washington dc#georgetown#vietnam memorial#arlington cemetery#grave of john f. kennedy#mount vernon#washington family tomb

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lieutenant Audie Murphy was the most highly decorated soldier in American history. On May 28, 1971, Audie Murphy boarded a private jet in Atlanta, Georgia, and made his way toward Martinsville, Virginia. There was heavy fog but the pilot chose to fly through it. The Aero Commander 680 carrying Murphy crashed into the side of Brush Mountain, 20 miles west of Roanoke. There were no survivors.

He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 46, headstone number 46-366-11. Outside of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and President John F. Kennedy, Murphy’s headstone is the most-visited grave. The volume of tourists visiting to pay respects was so great that they had to build an entirely new flagstone walkway to accommodate the foot traffic.

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

A long trip on an American highway in the summer of 2024 leaves the impression that two kinds of billboards now have near-monopoly rule over our roads. On one side, the billboards, gravely black-and-white and soberly reassuring, advertise cancer centers. (“We treat every type of cancer, including the most important one: yours”; “Beat 3 Brain Tumors. At 57, I gave birth, again.”) On the other side, brightly colored and deliberately clownish billboards advertise malpractice and personal-injury lawyers, with phone numbers emblazoned in giant type and the lawyers wearing superhero costumes or intimidating glares, staring down at the highway as they promise to do to juries.

A new Tocqueville considering the landscape would be certain that all Americans do is get sick and sue each other. We ask doctors to cure us of incurable illnesses, and we ask lawyers to take on the doctors who haven’t. We are frightened and we are angry; we look to expert intervention for the fears, and to comic but effective-seeming figures for retaliation against the experts who disappoint us.

Much of this is distinctly American—the idea that cancer-treatment centers would be in competitive relationships with one another, and so need to advertise, would be as unimaginable in any other industrialized country as the idea that the best way to adjudicate responsibility for a car accident is through aggressive lawsuits. Both reflect national beliefs: in competition, however unreal, and in the assignment of blame, however misplaced. We want to think that, if we haven’t fully enjoyed our birthright of plenty and prosperity, a nameable villain is at fault.

To grasp what is at stake in this strangest of political seasons, it helps to define the space in which the contest is taking place. We may be standing on the edge of an abyss, and yet nothing is wrong, in the expected way of countries on the brink of apocalypse. The country is not convulsed with riots, hyperinflation, or mass immiseration. What we have is a sort of phony war—a drôle de guerre, a sitzkrieg—with the vehemence of conflict mainly confined to what we might call the cultural space.

These days, everybody talks about spaces: the “gastronomic space,” the “podcast space,” even, on N.F.L. podcasts, the “analytic space.” Derived from some combination of sociology and interior design, the word has elbowed aside terms like “field” or “conversation,” perhaps because it’s even more expansive. The “space” of a national election is, for that reason, never self-evident; we’ve always searched for clues.

And so William Dean Howells began his 1860 campaign biography of Abraham Lincoln by mocking the search for a Revolutionary pedigree for Presidential candidates and situating Lincoln in the antislavery West, in contrast to the resigned and too-knowing East. North vs. South may have defined the frame of the approaching war, but Howells was prescient in identifying East vs. West as another critical electoral space. This opposition would prove crucial—first, to the war, with the triumph of the Westerner Ulysses S. Grant over the well-bred Eastern generals, and then to the rejuvenation of the Democratic Party, drawing on free-silver populism and an appeal to the values of the resource-extracting, expansionist West above those of the industrialized, centralized East.

A century later, the press thought that the big issues in the race between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy were Quemoy and Matsu (two tiny Taiwan Strait islands, claimed by both China and Taiwan), the downed U-2, the missile gap, and other much debated Cold War obsessions. But Norman Mailer, in what may be the best thing he ever wrote, saw the space as marked by the rise of movie-star politics—the image-based contests that, from J.F.K. to Ronald Reagan, would dominate American life. In “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” published in Esquire, Mailer revealed that a campaign that looked at first glance like the usual black-and-white wire-service photography of the first half of the twentieth century was really the beginning of our Day-Glo-colored Pop-art turn.

And our own electoral space? We hear about the overlooked vs. the élite, the rural vs. the urban, the coastal vs. the flyover, the aged vs. the young—about the dispossessed vs. the beneficiaries of global neoliberalism. Upon closer examination, however, these binaries blur. Support for populist nativism doesn’t track neatly with economic disadvantage. Some of Donald Trump’s keenest supporters have boats as well as cars and are typically the wealthier citizens of poorer rural areas. His stock among billionaires remains high, and his surprising support among Gen Z males is something his campaign exploits with visits to podcasts that no non-Zoomer has ever heard of.

But polarized nations don’t actually polarize around fixed poles. Civil confrontations invariably cross classes and castes, bringing together people from radically different social cohorts while separating seemingly natural allies. The English Revolution of the seventeenth century, like the French one of the eighteenth, did not array worn-out aristocrats against an ascendant bourgeoisie or fierce-eyed sansculottes. There were, one might say, good people on both sides. Or, rather, there were individual aristocrats, merchants, and laborers choosing different sides in these prerevolutionary moments. No civil war takes place between classes; coalitions of many kinds square off against one another.

In part, that’s because there’s no straightforward way of defining our “interests.” It’s in the interest of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to have big tax cuts; in the longer term, it’s also in their interest to have honest rule-of-law government that isn’t in thrall to guilds or patrons—to be able to float new ideas without paying baksheesh to politicians or having to worry about falling out of sixth-floor windows. “Interests” fail as an explanatory principle.

Does talk of values and ideas get us closer? A central story of American public life during the past three or four decades is (as this writer has noted) that liberals have wanted political victories while reliably securing only cultural victories, even as conservatives, wanting cultural victories, get only political ones. Right-wing Presidents and legislatures are elected, even as one barrier after another has fallen on the traditionalist front of manners and mores. Consider the widespread acceptance of same-sex marriage. A social transformation once so seemingly untenable that even Barack Obama said he was against it, in his first campaign for President, became an uncontroversial rite within scarcely more than a decade.

Right-wing political power has, over the past half century, turned out to have almost no ability to stave off progressive social change: Nixon took the White House in a landslide while Norman Lear took the airwaves in a ratings sweep. And so a kind of permanent paralysis has set in. The right has kept electing politicians who’ve said, “Enough! No more ‘Anything goes’!”—and anything has kept going. No matter how many right-wing politicians came to power, no matter how many right-wing judges were appointed, conservatives decided that the entire culture was rigged against them.

On the left, the failure of cultural power to produce political change tends to lead to a doubling down on the cultural side, so that wholesome college campuses can seem the last redoubt of Red Guard attitudes, though not, to be sure, of Red Guard authority. On the right, the failure of political power to produce cultural change tends to lead to a doubling down on the political side in a way that turns politics into cultural theatre. Having lost the actual stages, conservatives yearn to enact a show in which their adversaries are rendered humiliated and powerless, just as they have felt humiliated and powerless. When an intolerable contradiction is allowed to exist for long enough, it produces a Trump.

As much as television was the essential medium of a dozen bygone Presidential campaigns (not to mention the medium that made Trump a star), the podcast has become the essential medium of this one. For people under forty, the form—typically long-winded and shapeless—is as tangibly present as Walter Cronkite’s tightly scripted half-hour news show was fifty years ago, though the D.I.Y. nature of most podcasts, and the premium on host-read advertisements, makes for abrupt tonal changes as startling as those of the highway billboards.

On the enormously popular, liberal-minded “Pod Save America,” for instance, the hosts make no secret of their belief that the election is a test, as severe as any since the Civil War, of whether a government so conceived can long endure. Then they switch cheerfully to reading ads for Tommy John underwear (“with the supportive pouch”), for herbal hangover remedies, and for an app that promises to cancel all your excess streaming subscriptions, a peculiarly niche obsession (“I accidentally paid for Showtime twice!” “That’s bad!”). George Conway, the former Republican (and White House husband) turned leading anti-Trumper, states bleakly on his podcast for the Bulwark, the news-and-opinion site, that Trump’s whole purpose is to avoid imprisonment, a motivation that would disgrace the leader of any Third World country. Then he immediately leaps into offering—like an old-fashioned a.m.-radio host pushing Chock Full o’Nuts—testimonials for HexClad cookware, with charming self-deprecation about his own kitchen skills. How serious can the crisis be if cookware and boxers cohabit so cozily with the apocalypse?

And then there’s the galvanic space of social media. In the nineteen-seventies and eighties, we were told, by everyone from Jean Baudrillard to Daniel Boorstin, that television had reduced us to numbed observers of events no longer within our control. We had become spectators instead of citizens. In contrast, the arena of social media is that of action and engagement—and not merely engagement but enragement, with algorithms acting out addictively on tiny tablets. The aura of the Internet age is energized, passionate, and, above all, angry. The algorithms dictate regular mortar rounds of text messages that seem to come not from an eager politician but from an infuriated lover, in the manner of Glenn Close in “Fatal Attraction”: “Are you ignoring us?” “We’ve reached out to you PERSONALLY!” “This is the sixth time we’ve asked you!” At one level, we know they’re entirely impersonal, while, at another, we know that politicians wouldn’t do this unless it worked, and it works because, at still another level, we are incapable of knowing what we know; it doesn’t feel entirely impersonal. You can doomscroll your way to your doom. The democratic theorists of old longed for an activated citizenry; somehow they failed to recognize how easily citizens could be activated to oppose deliberative democracy.

If the cultural advantages of liberalism have given it a more pointed politics in places where politics lacks worldly consequences, its real-world politics can seem curiously blunted. Kamala Harris, like Joe Biden before her, is an utterly normal workaday politician of the kind we used to find in any functioning democracy—bending right, bending left, placating here and postponing confrontation there, glaring here and, yes, laughing there. Demographics aside, there is nothing exceptional about Harris, which is her virtue. Yet we live in exceptional times, and liberal proceduralists and institutionalists are so committed to procedures and institutions—to laws and their reasonable interpretation, to norms and their continuation—that they can be slow to grasp that the world around them has changed.

One can only imagine the fulminations that would have ensued in 2020 had the anti-democratic injustice of the Electoral College—which effectively amplifies the political power of rural areas at the expense of the country’s richest and most productive areas—tilted in the other direction. Indeed, before the 2000 election, when it appeared as if it might, Karl Rove and the George W. Bush campaign had a plan in place to challenge the results with a “grassroots” movement designed to short-circuit the Electoral College and make the popular-vote winner prevail. No Democrat even suggests such a thing now.

It’s almost as painful to see the impunity with which Supreme Court Justices have torched their institution’s legitimacy. One Justice has the upside-down flag of the insurrectionists flying on his property; another, married to a professional election denialist, enjoys undeclared largesse from a plutocrat. There is, apparently, little to be done, nor even any familiar language of protest to draw on. Prepared by experience to believe in institutions, mainstream liberals believe in their belief even as the institutions are degraded in front of their eyes.

In one respect, the space of politics in 2024 is transoceanic. The forms of Trumpism are mirrored in other countries. In the U.K., a similar wave engendered the catastrophe of Brexit; in France, it has brought an equally extreme right-wing party to the brink, though not to the seat, of power; in Italy, it elevated Matteo Salvini to national prominence and made Giorgia Meloni Prime Minister. In Sweden, an extreme-right group is claiming voters in numbers no one would ever have thought possible, while Canadian conservatives have taken a sharp turn toward the far right.

What all these currents have in common is an obsessive fear of immigration. Fear of the other still seems to be the primary mover of collective emotion. Even when it is utterly self-destructive—as in Britain, where the xenophobia of Brexit cut the U.K. off from traditional allies while increasing immigration from the Global South—the apprehension that “we” are being flooded by frightening foreigners works its malign magic.

It’s an old but persistent delusion that far-right nationalism is not rooted in the emotional needs of far-right nationalists but arises, instead, from the injustices of neoliberalism. And so many on the left insist that all those Trump voters are really Bernie Sanders voters who just haven’t had their consciousness raised yet. In fact, a similar constellation of populist figures has emerged, sharing platforms, plans, and ideologies, in countries where neoliberalism made little impact, and where a strong system of social welfare remains in place. If a broadened welfare state—national health insurance, stronger unions, higher minimum wages, and the rest—would cure the plague in the U.S., one would expect that countries with resilient welfare states would be immune from it. They are not.

Though Trump can be situated in a transoceanic space of populism, he isn’t a mere symptom of global trends: he is a singularly dangerous character, and the product of a specific cultural milieu. To be sure, much of New York has always been hostile to him, and eager to disown him; in a 1984 profile of him in GQ, Graydon Carter made the point that Trump was the only New Yorker who ever referred to Sixth Avenue as the “Avenue of the Americas.” Yet we’re part of Trump’s identity, as was made clear by his recent rally on Long Island—pointless as a matter of swing-state campaigning, but central to his self-definition. His belligerence could come directly from the two New York tabloid heroes of his formative years in the city: John Gotti, the gangster who led the Gambino crime family, and George Steinbrenner, the owner of the Yankees. When Trump came of age, Gotti was all over the front page of the tabloids, as “the Teflon Don,” and Steinbrenner was all over the back sports pages, as “the Boss.”

Steinbrenner was legendary for his middle-of-the-night phone calls, for his temper and combativeness. Like Trump, who theatricalized the activity, he had a reputation for ruthlessly firing people. (Gotti had his own way of doing that.) Steinbrenner was famous for having no loyalty to anyone. He mocked the very players he had acquired and created an atmosphere of absolute chaos. It used to be said that Steinbrenner reduced the once proud Yankees baseball culture to that of professional wrestling, and that arena is another Trumpian space. Pro wrestling is all about having contests that aren’t really contested—that are known to be “rigged,” to use a Trumpian word—and yet evoke genuine emotion in their audience.

At the same time, Trump has mastered the gangster’s technique of accusing others of crimes he has committed. The agents listening to the Gotti wiretap were mystified when he claimed innocence of the just-committed murder of Big Paul Castellano, conjecturing, in apparent seclusion with his soldiers, about who else might have done it: “Whoever killed this cocksucker, probably the cops killed this Paul.” Denying having someone whacked even in the presence of those who were with you when you whacked him was a capo’s signature move.

Marrying the American paranoid style to the more recent cult of the image, Trump can draw on the manner of the tabloid star and show that his is a game, a show, not to be taken quite seriously while still being serious in actually inciting violent insurrections and planning to expel millions of helpless immigrants. Self-defined as a showman, he can say anything and simultaneously drain it of content, just as Gotti, knowing that he had killed Castellano, thought it credible to deny it—not within his conscience, which did not exist, but within an imaginary courtroom. Trump evidently learned that, in the realm of national politics, you could push the boundaries of publicity and tabloid invective far further than they had ever been pushed.

Trump’s ability to be both joking and severe at the same time is what gives him his power and his immunity. This power extends even to something as unprecedented as the assault on the U.S. Capitol. Trump demanded violence (“If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore”) but stuck in three words, “peacefully and patriotically,” that, however hollow, were meant to immunize him, Gotti-style. They were, so to speak, meant for the cops on the wiretap. Trump’s resilience is not, as we would like to tell our children about resilience, a function of his character. It’s a function of his not having one.

Just as Trump’s support cuts across the usual divisions, so, too, does a divide among his opponents—between the maximizers, who think that Trump is a unique threat to liberal democracy, and the minimizers, who think that he is merely the kind of clown a democracy is bound to throw up from time to time. The minimizers (who can be found among both Marxist Jacobin contributors and Never Trump National Review conservatives) will say that Trump has crossed the wires of culture and politics in a way that opportunistically responds to the previous paralysis, but that this merely places him in an American tradition. Democracy depends on the idea that the socially unacceptable might become acceptable. Andrew Jackson campaigned on similar themes with a similar manner—and was every bit as ignorant and every bit as unaware as Trump. (And his campaigns of slaughter against Indigenous people really were genocidal.) Trump’s politics may be ugly, foolish, and vain, but ours is often an ugly, undereducated, and vain country. Democracy is meant to be a mirror; it shows what it shows.

Indeed, America’s recent history has shown that politics is a trailing indicator of cultural change, and that one generation’s most vulgar entertainment becomes the next generation’s accepted style of political argument. David S. Reynolds, in his biography of Lincoln, reflects on how the new urban love of weird spectacle in the mid-nineteenth century was something Lincoln welcomed. P. T. Barnum’s genius lay in taking circus grotesques and making them exemplary Americans: the tiny General Tom Thumb was a hero, not a freak. Lincoln saw that it cost him nothing to be an American spectacle in a climate of sensation; he even hosted a reception at the White House for Tom Thumb and his wife—as much a violation of the decorum of the Founding Fathers as Trump’s investment in Hulk Hogan at the Republican Convention. Lincoln understood the Barnum side of American life, just as Trump understands its W.W.E. side.

And so, the minimizers say, taking Trump seriously as a threat to democracy in America is like taking Roman Reigns seriously as a threat to fair play in sports. Trump is an entertainer. The only thing he really wants are ratings. When opposing abortion was necessary to his electoral coalition, he opposed it—but then, when that was creating ratings trouble in other households, he sent signals that he wasn’t exactly opposed to it. When Project 2025, which he vaguely set in motion and claims never to have read, threatened his ratings, he repudiated it. The one continuity is his thirst for popularity, which is, in a sense, our own. He rows furiously away from any threatening waterfall back to the center of the river—including on Obamacare. And, the minimizers say, in the end, he did leave the White House peacefully, if gracelessly.

In any case, the panic is hardly unique to Trump. Reagan, too, was vilified and feared in his day, seen as the reductio ad absurdum of the culture of the image, an automaton projecting his controllers’ authoritarian impulses. Nixon was the subject of a savage satire by Philip Roth that ended with him running against the Devil for the Presidency of Hell. The minimizers tell us that liberals overreact in real time, write revisionist history when it’s over, and never see the difference between their stories.

The maximizers regard the minimizers’ case as wishful thinking buoyed up by surreptitious resentments, a refusal to concede anything to those we hate even if it means accepting someone we despise. Maximizers who call Trump a fascist are dismissed by the minimizers as either engaging in name-calling or forcing a facile parallel. Yet the parallel isn’t meant to be historically absolute; it is meant to be, as it were, oncologically acute. A freckle is not the same as a melanoma; nor is a Stage I melanoma the same as the Stage IV kind. But a skilled reader of lesions can sense which is which and predict the potential course if untreated. Trumpism is a cancerous phenomenon. Treated with surgery once, it now threatens to come back in a more aggressive form, subject neither to the radiation of “guardrails” nor to the chemo of “constraints.” It may well rage out of control and kill its host.

And so the maximalist case is made up not of alarmist fantasies, then, but of dulled diagnostic fact, duly registered. Think hard about the probable consequences of a second Trump Administration—about the things he has promised to do and can do, the things that the hard-core group of rancidly discontented figures (as usual with authoritarians, more committed than he is to an ideology) who surround him wants him to do and can do. Having lost the popular vote, as he surely will, he will not speak up to reconcile “all Americans.” He will insist that he won the popular vote, and by a landslide. He will pardon and then celebrate the January 6th insurrectionists, and thereby guarantee the existence of a paramilitary organization that’s capable of committing violence on his behalf without fear of consequences. He will, with an obedient Attorney General, begin prosecuting his political opponents; he was largely unsuccessful in his previous attempt only because the heads of two U.S. Attorneys’ offices, who are no longer there, refused to coöperate. When he begins to pressure CNN and ABC, and they, with all the vulnerabilities of large corporations, bend to his will, telling themselves that his is now the will of the people, what will we do to fend off the slow degradation of open debate?

Trump will certainly abandon Ukraine to Vladimir Putin and realign this country with dictatorships and against NATO and the democratic alliance of Europe. Above all, the spirit of vengeful reprisal is the totality of his beliefs—very much like the fascists of the twentieth century in being a man and a movement without any positive doctrine except revenge against his imagined enemies. And against this: What? Who? The spirit of resistance may prove too frail, and too exhausted, to rise again to the contest. Who can have confidence that a democracy could endure such a figure in absolute control and survive? An oncologist who, in the face of this much evidence, shrugged and proposed watchful waiting as the best therapy would not be an optimist. He would be guilty of gross malpractice. One of those personal-injury lawyers on the billboards would sue him, and win.

What any plausible explanation must confront is the fact that Trump is a distinctively vile human being and a spectacularly malignant political actor. In fables and fiction, in every Disney cartoon and Batman movie, we have no trouble recognizing and understanding the villains. They are embittered, canny, ludicrous in some ways and shrewd in others, their lives governed by envy and resentment, often rooted in the acts of people who’ve slighted them. (“They’ll never laugh at me again!”) They nonetheless have considerable charm and the ability to attract a cult following. This is Ursula, Hades, Scar—to go no further than the Disney canon. Extend it, if that seems too childlike, to the realms of Edmund in “King Lear” and Richard III: smart people, all, almost lovable in their self-recognition of their deviousness, but not people we ever want to see in power, for in power their imaginations become unimaginably deadly. Villains in fables are rarely grounded in any cause larger than their own grievances—they hate Snow White for being beautiful, resent Hercules for being strong and virtuous. Bane is blowing up Gotham because he feels misused, not because he truly has a better city in mind.

Trump is a villain. He would be a cartoon villain, if only this were a cartoon. Every time you try to give him a break—to grasp his charisma, historicize his ascent, sympathize with his admirers—the sinister truth asserts itself and can’t be squashed down. He will tell another lie so preposterous, or malign another shared decency so absolutely, or threaten violence so plausibly, or just engage in behavior so unhinged and hate-filled that you’ll recoil and rebound to your original terror at his return to power. One outrage succeeds another until we become exhausted and have to work hard even to remember the outrages of a few weeks past: the helicopter ride that never happened (but whose storytelling purpose was to demean Kamala Harris as a woman), or the cemetery visit that ended in a grotesque thumbs-up by a graveside (and whose symbolic purpose was to cynically enlist grieving parents on behalf of his contempt). No matter how deranged his behavior is, though, it does not seem to alter his good fortune.

Villainy inheres in individuals. There is certainly a far-right political space alive in the developed world, but none of its inhabitants—not Marine Le Pen or Giorgia Meloni or even Viktor Orbán—are remotely as reckless or as crazy as Trump. Our self-soothing habit of imagining that what has not yet happened cannot happen is the space in which Trump lives, just as comically deranged as he seems and still more dangerous than we know.

Nothing is ever entirely new, and the space between actual events and their disassociated representation is part of modernity. We live in that disassociated space. Generations of cultural critics have warned that we are lost in a labyrinth and cannot tell real things from illusion. Yet the familiar passage from peril to parody now happens almost simultaneously. Events remain piercingly actual and threatening in their effects on real people, while also being duplicated in a fictive system that shows and spoofs them at the same time. One side of the highway is all cancer; the other side all crazy. Their confoundment is our confusion.

It is telling that the most successful entertainments of our age are the dark comic-book movies—the Batman films and the X-Men and the Avengers and the rest of those cinematic universes. This cultural leviathan was launched by the discovery that these ridiculous comic-book figures, generations old, could now land only if treated seriously, with sombre backstories and true stakes. Our heroes tend to dullness; our villains, garishly painted monsters from the id, are the ones who fuel the franchise.

During the debate last month in Philadelphia, as Trump’s madness rose to a peak of raging lunacy—“They’re eating the dogs”; “He hates her!”—ABC, in its commercial breaks, cut to ads for “Joker: Folie à Deux,” the new Joaquin Phoenix movie, in which the crazed villain swirls and grins. It is a Gotham gone mad, and a Gotham, against all the settled rules of fable-making, without a Batman to come to the rescue. Shuttling between the comic-book villain and the grimacing, red-faced, and unhinged man who may be reëlected President in a few weeks, one struggled to distinguish our culture’s most extravagant imagination of derangement from the real thing. The space is that strange, and the stakes that high. ♦

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jackie Kennedy and her two children pay a visit to John F Kennedy’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery on what would have been his 47th birthday - May 29, 1964

#jackie kennedy#jacqueline bouvier kennedy#caroline kennedy#john f kennedy jr#jfk jr#kennedy family#the kennedys

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was Trump's assassination attempt the first time people other than the president were also killed or hurt?

No, it definitely was not the first time. There have been a number of additional victims during Presidential assassinations or assassination attempts throughout American history.

Here are the incidents where someone other than the President was wounded in an assassination attempt on Presidents or Presidential candidates:

•April 14, 1865, Washington, D.C. At the same time that John Wilkes Booth was shooting Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, Booth's fellow conspirator, Lewis Powell, attacked Secretary of State William H. Seward at Seward's home in Washington. Seward had been injured earlier that month in a carriage accident and was bedridden from his injuries, and Powell viciously stabbed the Secretary of State after forcing his way into Seward's home by pretending to deliver medicine. Powell also attacked two of Seward's sons, a male nurse from the Army who was helping to care for Seward, and a messenger from the State Department. Another Booth conspirator, George Azterodt, was supposed to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson at the same time that Lincoln and Seward were being attacked in an attempt to decapitate the senior leadership of the Union government, but Azterodt lost his nerve and got drunk instead. A total of five people were wounded at the Seward home as part of the Booth conspiracy, but Lincoln was the only person who was killed.

•February 15, 1933, Miami, Florida Just 17 days before his first inauguration, President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt was the target of an assassination attempt in Miami's Bayfront Park. Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt as FDR was speaking from an open car. Roosevelt was not injured, but all five bullets hit people in the crowd, including Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak who was in the car with FDR. Roosevelt may have been saved by a woman in the crowd who hit Zangara's arm with her purse as she noticed he was aiming his gun at the President-elect and caused him to shoot wildly. Mayor Cermak was gravely wounded and immediately rushed to a Miami hospital where he died about two weeks later.

•November 1, 1950, Blair House, Washington, D.C. From 1949-1952, the White House was being extensively renovated with the interior being almost completely gutted and reconstructed. President Harry S. Truman and his family moved into Blair House, a Presidential guest house across the street from the White House that is normally used for visiting VIPs, for 3 1/2 years. On November 1, 1950 two Puerto Rican nationalists, Griselio Torresola and Oscar Collazo, tried to shoot their way into Blair House and attempt to kill President Truman, who was upstairs (reportedly napping) at the time. A wild shootout ensued on Pennsylvania Avenue, leaving White House Police Officer Leslie Coffelt and Torresola dead, and Collazo and two other White House Police Officers wounded.

•November 22, 1963, Dallas, Texas Texas Governor John Connally was severely wounded after being shot while riding in the open limousine with President John F. Kennedy when JFK was assassinated.

•June 5, 1968, Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, California When he finished delivering a victory speech after winning California's Democratic Presidential primary, Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York was shot several times while walking through the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel. While RFK was mortally wounded and would die a little over a day later, five other people were also wounded in the shooting.

•May 15, 1972, Laurel, Maryland Segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace was paralyzed from the waist down after being shot by Arthur Bremer at a campaign rally when he was running for the Democratic Presidential nomination. Three bystanders were also wounded in the shooting, but survived.

•September 22, 1975, San Francisco, California A taxi driver in San Francisco was wounded when Sara Jane Moore attempted to shoot President Gerald Ford as he left the St. Francis Hotel. Moore's first shot missed the President by several inches and the second shot, which hit the taxi driver, was altered when a Vietnam veteran in the crowd named Oliver Sipple grabbed her arm as she was firing. Just 17 days earlier and 90 miles away, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a member of the Charles Manson family, had tried to shoot President Ford as he walked through Capitol Park in Sacramento but nobody was injured.

•March 30, 1981, Washington, D.C. President Ronald Reagan was shot and seriously wounded by as he left the Washington Hilton after giving a speech. Three other people were wounded in the shooting, including White House Press Secretary James Brady who was shot in the head and partially paralyzed, Washington D.C. Police Office Thomas Delahanty, and Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy. Video of the assassination attempt shows that when the shots were fired, McCarthy turned and made himself a bigger target in order to shield the President with his own body. President Reagan was struck by a bullet that ricocheted off of the Presidential limousine.

#History#Presidential Assassinations#Presidential Assassination Attempts#Presidency#Politics#Political History#Assassinations#Attempted Assassinations#Lincoln Assassination#Assassination of Abraham Lincoln#Booth Conspiracy#Attempted Assassination of President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt#FDR#Franklin D. Roosevelt#President Roosevelt#Puerto Rican Nationalists#Attempted Assassination of Harry S. Truman#President Truman#Secret Service#United States Secret Service#White House Police#Presidential History#Robert F. Kennedy#RFK Assassination#Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy#Attempted Assassination of George Wallace#Attempted Assassination of Gerald Ford#President Ford#Attempted Assassination of Ronald Reagan#President Reagan

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 20th, 1970 - After visiting the grave of her husband in Arlington National Cemetery, Mrs. Robert F. Kennedy with five of her children and Senator and Mrs. Edward Kennedy visit the nearby grave of President John F. Kennedy. The children are (L-R) Maxwell, Kerry, Michael, (behind) Christopher, and Courtney. The two roses were placed by Mrs. Robert Kennedy and Senator Edward Kennedy, whose wife is at extreme right.

#1970s#1970#Joan Bennett Kennedy#Joan Kennedy#Ted Kennedy#EMK#Edward M. Kennedy#Ethel Kennedy#Maxwell Kennedy#Kerry Kennedy#Michael kennedy#Christopher Kennedy#Courtney Kennedy#The Kennedys#Kennedy#Arlington cemetery#Cemetery

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mashup artists featured on this blog

Note: due to tumblr having a limit on the number of links you can have in one post, I've only linked the tags of those mashup artists who have more than one word in their name, or if it's long/complicated. You'll have to type the others into search yourself.

#

3DMA

64gigs

86toMoose

A

a table

Adamusic

Amanda

Andrew Hagen

AnDyWuMUSICLAND

Anna McBurgendy

Arkadius

axelnapalm

B

Baaanggg

Beans McSprout

Bessco Samune

Birch

Blanter Co

Blood Love

Boebie

Byronxazz

C

Cacola

Cameron Hayes

Camhorn

Choinkus

chongo

Chris Taylor

CLMC Music

Cow Vibing

Cryptrik

D

dabunky

Damonis Midnight

Daniel Kendall

DaymanOurSavior

Deep V

Demi Adejuyigbe

demionbrisk

Denis Tognolo

Deospark

DiamondBrickZ

Dimitri Schmidt

diornotwar123

DJCJ

DJ BrookeTheProducer

DJ Cummerbund

DJ Earworm

DJ Flapjack

DJ MikeA

DJ Morgoth

DJ Poly

DJ Poulpi

DJ Surge-N

DM Mashups

domburg

Domino's Dump

DRA'man

Drewdot

duuzu

E

earlvin14

Ella Noir

Ellie Spectacular

Ema Pex

Eminem Mashups

EpicToast

eqt. studios

Erika Ersson

EvilGenki

Exightly

F

FG Roland DJ

Flipboitamidles

FrenchFri

G

Gingergreen

goodthingsnow777

Grave Danger

Gregory Brothers

groboclone

H

Hailey Schnur

Hala Nassar

Happy Cat Disco

harpistkt

Hilolila

Horologium

How2BEpic

I

Ian

Idlehands

InanimateMashups

Irn Mnky

itspeyday

Isomer

Isosine

Ivaalo

J

J Mixes

jackhoeting 909

Jacob Sutherland

Jake Ranney

Jalex Petrie

Jamie Truelove Music

Jason Rollins

Joebot the Robot

Jerome Tremenz

John Fassold

Joleszezanev

Jonathan Coulton

Joseph James

JSaga

Justin Robinett

jyeoms

K

Kahizer

Karu

Kathleen

Kill_mR_DJ

Kiltro

Krale

L

Lamaita

levsadohoff

LibraH

Liddell

lobsterdust

Lopan

Lord Pandemicus

Luise Gad Lund

M

Madeon

madmartigan2012

Marc Johnce

Mark Hattori

Masdamind99

Mastgrr

Matt Nguyen-Ngo

Mauricio V

mashed potatoes

memes die

Michael Henry

MixmstrStel

mrfun4isback

Mouthies

MysticWolf

N

nakinyko

Nandy sisters

Nate Belasco

Neddly

Neil Circierega

Norwegian Recycling

O

OctogonCollaboration

OhKay

One Bored Jeu

Oskr96fred 4

Otto Hast

P

paper-mario-wiki

Partyben

PaulineeIsHere

Ph0ton

piratecovejoe

Piscicore

pluffaduff

PomDeter

Pomplamoose

primmsfairytale

ProdByJadii

pseudosalient

Psynwav

R

Rage/Chill Music

Raheem D

Rani KoHEnur

Ranvision

Red Omega

RezaMusic

Rick Sama

Robin Skouteris

Rolling Quartz

Ruskya

S

Salvador Peralta

Scibot9000

Scott

Scout

SheldonJpiripCooper

shimshamwow

Shokk

Shoopfex

SilvaGunner

Slayyyter

SmadaLeinad

Sowndhaus

SP Mashups

Squeaky Belle

swag mastar

Szoszism

T

T12

Taylor Kennedy

TCMusic

Tenkrom

The Optimist

There I Ruined It

THiNGYBOBinc

thquib

Tito Silva

Titus Jones

Triple Q

U

UberDisney

Ultra Music

Unai

unknown

V

Valter Henrique

Vazer

W

Wax Audio

Waxolotl

William Maranci

Wyd Hart

Y

YamiNoBahamut

Yitt

Z

Zakuzu

Zedd

Zode

Zoraya

Other artists/types of music

Bad Lip Reading

Key shift (major to minor or vice versa)

Shitposts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Quizá la más grande lección de la historia es que nadie aprendió las lecciones de la historia”

Aldous Huxley

Fue un escritor y filósofo británico nacido en julio de 1984.

Miembro de una reconocida familia de intelectuales, fue conocido por sus novelas y ensayos a través de los cuales ejerció como crítico social.

Fue también un interesado en temas parapsicológicos y místicos, acerca de los cuales escribió varios libros y relató sus experiencias con sustancias psicotrópicas como la mezcalina y el LSD.

Aldous fue el tercero de cuatro hermanos, uno de los cuales se convertiría en un destacado divulgador científico y eminente biólogo y otro de ellos cometería suicidio.

A la edad de 16 años sufre de una grave enfermedad en los ojos que lo tendría limitado de la vista por el resto de su vida. Esta enfermedad le obliga a declinar su intención de estudiar medicina graduándose en literatura inglesa en el Balliol College de Oxford en 1915.

Sus primeros trabajos fueron publicados a la edad de veintidós años y fue profesor del prestigioso colegio Eton donde fue alumno.

Pensador incansable dueño de un saber enciclopédico y asiduo viajero, incursionó gran parte de su vida a saciar su sed de experiencias y conocimientos a lo largo del mundo, publicando sus obras, impartiendo conferencias, publicando artículos y escribiendo ensayos.

En su pensamiento puede destacarse la necesidad de aportar al mundo una estructura útil.

En 1932 en cuatro meses, escribe la obra que lo haría más famoso; Un mundo feliz (Brave new world), una anti utopía ficticia en donde la humanidad es ordenada en castas, avanzada tecnológicamente y libre sexualmente. En donde la guerra y la pobreza han sido erradicadas y las personas aceptan su condición y son felices, un mundo que para ser feliz debe eliminar la familia, el arte, la religión, la literatura, la ciencia y el amor.

Otra obras famosas de Huxley son; “Las puertas de la percepción” y “La Isla”.

Muere a los sesenta y nueve años el mismo día del asesinato del presidente John F. Kennedy. Al morir pidió se le leyera al oído El libro tibetano de los muertos, (una de sus lecturas preferidas) y que le fuera administrado LSD como terapia agónica.

Fuente: Wikipedia, psicologiaymente.com

#aldous huxley#citas de escritores#escritores#notasfilosoficas#frases de filosofos#filosofos#frases de reflexion#citas de reflexion#inglaterra

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arlington National Cemetery was established on June 15, 1864, when 200 acres (0.81 km2) around Arlington Mansion (formerly owned by Confederate General Robert E. Lee) are officially set aside as a military cemetery by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.

#Arlington National Cemetery#established#15 June 1864#anniversary#US history#Virginia#John F. Kennedy's grave#Robert Kennedy's grave#Arlington Mansion#architecture#lawn#tree#tourist attraction#landmark#summer 2009#original photography#vacation#travel#cityscape#landscape#USA#flora#nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Stanislaw Albrecht Radziwill, Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy, Caroline Kennedy, John F. Kennedy, Jr. visit the grave of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, June 9, 1968 in Arlington National Cemetery.

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

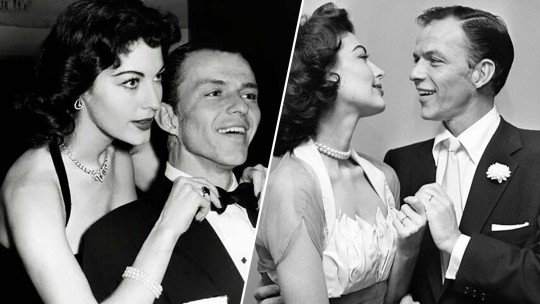

Hell, I suppose if you stick around long enough they have to say something nice about you.

- Ava Gardner, Ava: My Story

Ava Gardner was a hard-drinking, wisecracking, libidinous vamp, a liberated woman before it was even invented.

It's an extraordinary life of an extraordinary woman. She swore like a drunken sailor, slept with anything that moved, drove Frank Sinatra to such heights of passion and torment that he attempted suicide, and entirely failed to care what anybody thought of her.

Ava Gardner was an actress who starred in some good films and some not very good films; but more than that she was the great iconic beauty of her day. She wafted around the screen and was featured on the front covers of magazines looking untouchable in pearls and mink. And yet she behaved like a man or, at least, like a certain kind of man - one with pots of cash, a taste for hard liquor and a higher-than-average libido.

She was, in essence, a liberated woman, a good two decades before women's liberation was invented. Her success and status made it possible for her to make the kind of choices - and mistakes - that other women couldn't. And, even now, there's really nobody who can match her combination of carnality, glamour and a potty-mouth.

Sixty years on, people claim that Sex and the City's Samantha Jones is the figment of a gay, male scriptwriter's imagination, but compare it to this story from Murray Garrett, a press photographer, recounting a backstage photo-call: 'This one idiot guy ... says to her, "Hey Ava, Sinatra's career is over, he can't sing any more ... what do you see in this guy? He's just a 119-pound has-been." And Ava says, very demurely, no venom, just very cool, in the most perfect ladylike diction, "Well I'll tell you - 19 pounds is cock."'

She married three times - to Mickey Rooney (a serial cheater), the musician Artie Shaw (who belittled her) and finally and most tumultuously to Frank Sinatra. She lured him away from his wife, sinking his career in the process, married him, divorced him, but never got over him. Nor he her. It was a life-long relationship between two people who loved each other but couldn't be together. Their rows, she said, 'started on the way to the bidet'.

Instead, Gardner had affairs. They litter her life. She slept with David Niven, Robert Mitchum, John F Kennedy. She had flings with Spanish bullfighters and Mexican beach boys and rejected Howard Hughes, the multi-millionaire aviator and womaniser.

What made Gardner who she was? It's the great, unanswered question of her life and career. There is nothing in the early years to suggest her character to come. Not the tomboyish childhood spent with her family among the ordinary rural poor of north Carolina; nor the moment when an MGM studio exec spotted her portrait in the window of a photographer's shop; nor even when she married Mickey Rooney, the studio's biggest star.

It is as if her character wasn't so much revealed over time, as forged in the furnaces of Hollywood's industrial complex.There are countless testimonies from other Hollywood stars to Gardner's beauty, but almost no sense of her as a person. She gradually turns from object to subject, her beauty her defining characteristic and the key to her power and freedom but also, as her favourite director, John Huston, says, a curse from the gods. 'Ava,' he said, 'has well and truly paid for her beauty.'

Her high spirits descend into alcoholic abuse; her wanton behaviour into episodes such as the one when she is banned from the Ritz in Madrid for urinating in the lobby; when she moves to live out her days in the relative anonymity of a London flat it is with a sinking heart that you realise that the woman who charmed Ernest Hemingway and Robert Graves should become so isolated.

She made some truly terrible choices, including turning down the role of Mrs Robinson in The Graduate and ending her days making schlock TV. She was careless of her art, under-confident about her talent and tended to be taken at her own measure. But ultimately, it's besides the point. Gardner's genius was not her work, but, as her own autobiographical book proves, her life.

#gardner#ava gardner#quote#actress#hollywood#golden age#beauty#film#cinema#movies#diva#sex siren#sex appeal#femme fatale#culture

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering John F. Kennedy, his intellect, his vision, his words. (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963)

"I think the American people expect more from us than cries of indignation and attack. The times are too grave, the challenge too urgent, and the stakes too high to permit the customary passions of political debate. We are not here to curse the darkness, but to light the candle that can guide us through that darkness to a safe and sane future.”

"The life of the arts, far from being an interruption, a distraction, in the life of a nation, is very close to the center of a nation’s purpose and is a test of the quality of a nation’s civilization.”

"“Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce."

[Sherry Baker]

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Grace of Monaco brought a floral tribute to the grave of John F. Kennedy at Arlington National Cementary on December 2, 1963.

3 notes

·

View notes