#Jean Aurenche

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Coup de Torchon / Clean Slate (1981). A pathetic police chief, humiliated by everyone around him, suddenly wants a clean slate in life - and resorts to drastic means to do so.

A moody French crime film that takes the American western tropes and surplants them to France-occupied West Africa. It works better than you'd think, and is particularly grounded by a wonderful performance from a young Isabelle Huppert! 7/10.

#clean slate#1981#Oscars 55#Nom: Foreign Film#France#french#senegal#africa#1930s#crime#drama#Bertrand Tavernier#Jean Aurenche#Philippe Noiret#isabelle huppert#Stéphane Audran#colonialism#7/10

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

LE STYLE AURENCHE ET BOST

Duo vedette du scénario durant trois décennies, Jean Aurenche et Pierre Bost ont écrit à quatre mains une soixantaine de films, dont plusieurs chefs-d’œuvre. Torpillés par la Nouvelle vague, ils seront réhabilités par Bertrand Tavernier qui fera de Jean Aurenche l’une des principales figures de son film Laissez-passer en 1992. Pierre Bost et Jean Aurenche Si leurs noms sont aujourd’hui moins…

View On WordPress

#bertrand tavernier#claude autant lara#françois truffaut#jean aurenche#jean delannoy#jean gabin#pierre bost#rené clément#yves allégret

0 notes

Text

"Autoportrait dans un Photomaton" de Jean Aurenche, Marie-Berthe Aurenche et Max Ernst (circa 1929) à l'exposition “Surréalisme" au Centre Pompidou, Paris, novembre 2024.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacques Prévert et le cinéma

Écrit par Carole Aurouet Jacques Prévert (1900-1977) marqua incontestablement de son empreinte le cinéma français des années 1930 à 1960. « Un jour, le cinéma s’est mis à parler Prévert », écrit Jean Aurenche (La Suite à l’écran, 1993). À l’occasion du quarantenaire de sa disparition, revenons sur l’œuvre cinématographique féconde de ce grand scénariste. Théâtre, littérature, chanson,…

View On WordPress

#Cinéma#Diálogo#Dibujo#Escrita#Extravagància#Insolite#Legalidad#Lenguaje#Liberté#Literatura#Lucidesa#Marc Chagall#Música#Meios#Normas#Photographie#Pintura#Plaisir#Poésie#Recherche#Sobriété#Théâtre

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bernard Blier and Arletty in Hõtel du Nord (Marcel Carné, 1938) Cast: Arletty, Louis Jouvet, Annabella, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Jane Marken, André Brunot. René Bergeron, Paulette Dubost, François Périer, Andrex, Henri Bosc, Marcel André, Bernard Blier, Jacques Louvigny, Armand Lurville, Génia Vaury. Screenplay: Henri Jeanson, Jean Aurenche, based on a novel by Eugène Dabit. Cinematography: Louis Née, Armand Thirard. Production design: Alexandre Trauner. Film editing: Marthe Gottié, René Le Hénaff. Music: Maurice Jaubert. Arletty's performance as the raucous streetwalker Raymonde in Hôtel du Nord is quite unlike her most famous role, the fascinating, enigmatic Garance in Marcel Carné's Children of Paradise (1945). Raymonde shares a room in the hotel with Edmond (Louis Jouvet), a photographer who is hiding out from his old cronies in the Parisian underworld. The film begins with a traveling shot along the canal that flanks the hotel, where we first see a young pair of lovers, Pierre (Jean-Pierre Aumont) and Renée (Annabella), walking arm in arm. Inside the hotel, the residents are celebrating the first communion of the daughter of Maltaverne (René Bergeron), a policeman who lives at the hotel. (It's a diverse household.) Pierre and Renée enter and request a room for the night, but instead of making love, they have decided on a suicide pact: He will shoot her, then kill himself. He holds up the first part of the bargain, but then chickens out. Edmond, who has been in his darkroom, hears the shot and breaks down the door, finding Renée apparently dead and Pierre cowering indecisively. Taking the gun from Pierre, Edmond urges him to flee. (The gun becomes a Chekhov's gun when Edmond first tosses it away and then recovers it and stashes it in a drawer.) Renée recovers from the gunshot, and Pierre, torn with guilt, turns himself in to the police as an attempted murderer and is sent to prison. After she recuperates, Renée returns to the hotel to collect her things, and is offered a job there by Madame Lecouvreur (Jane Marken), the wife of the proprietor (André Brunot). And so the story of the suicidal lovers begins to intertwine with that of Edmond and Raymonde. It's all neatly done, with a great deal of atmosphere (a word that Raymonde will give a particular spin to), much of it created by Alexandre Trauner's set, a re-creation in the studios at Billancourt of the actual hotel and the Canal St. Martin. The film's melodrama is alleviated by the ensemble work and the performances of Jouvet, who can switch from menacing to vulnerable in an instant, and Arletty, who makes the tough, worldly wise Raymonde often very funny. The film concludes with Carné's skillful staging of an elaborate Bastille Day sequence that anticipates the crowd scenes in Children of Paradise.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

La photo, affirmait Chris Marker en 1966, c’est I’instinct de chasse sans l’envie de tuer. C’est la chasse des anges… On traque, on vise, on tire et- clac ! au lieu d’un mort, on fait un éternel. Mes vœux d’Annette Messager – 263 épreuves photographiques représentant des détails corporels de femmes et d’hommes 1989 Mes voeux (zoom) Man Ray Chapeau par Elsa Schiaparelli – 1933 Photomatons de MB. Aurenche, J.Prévert, M.Ernst, Y.Tanguy vers 1929 W.Eugene Smith – Jean Pierson 1949 Sergio Larrain – Photos du Chili – 1952 Chris Marker, la chouette, le mystère Koumiko et Jacques Branchu, son (l’) ami de ma 1ère vie HC.Bresson Gotthard Schuh – mineur belge 1937 Nusch Eluard à gauche (photo de Dora Maar) et poème de Paul Eluard à droite – extrait de son opuscule “le temps déborde” dédié à son épouse partie dans l’autre monde et publié en 1947 HC. Bresson à 24 ans – Mexico 1934 – sublime… “Nous ne vieillirons pas ensemble Voici le jour En trop : le temps déborde” (Paul Eluard)

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

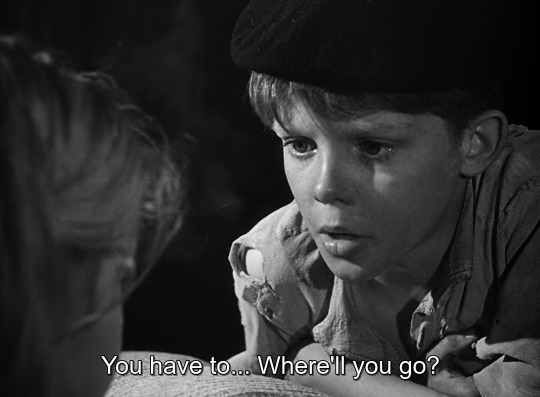

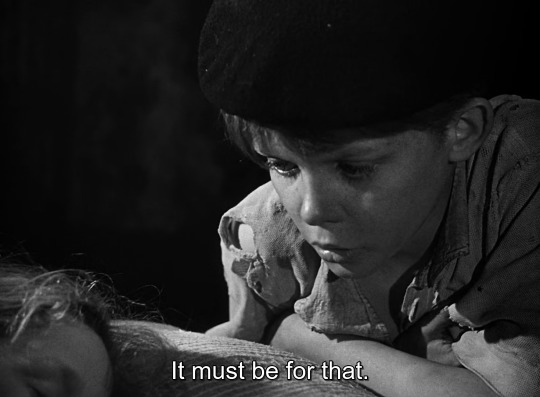

Forbidden Games (René Clément, 1952).

#jeux interdits#jeux interdits (1952)#rené clément#forbidden games#françois boyer#jean aurenche#pierre bost#brigitte fossey#georges poujouly#robert juillard#roger dwyre#paul bertrand#majo brandley

33 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Better the blind man who pisses out the window than the joker who told him it was a urinal.

Lucien Cordier, Coup De Torchon

#Lucien Cordier#Coup De Torchon#Coup De Torchon movie#Coup De Torchon Movie Quotes#Movie Quotes#quotes#wordporn#Bertrand Tavernier#Jean Aurenche#Jim Thompson#quote#quote of the day

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

- Don’t be modest. - I do what I can.

The Trip Across Paris (La traversée de Paris), Claude Autant-Lara (1956)

#Claude Autant Lara#Jean Aurenche#Pierre Bost#Jean Gabin#Bourvil#Louis de Funès#Jeannette Batti#Georgette Anys#Robert Arnoux#Myno Burney#Monette Dinay#Béatrice Arnac#Anouk Ferjac#Jacques Natteau#René Cloërec#Madeleine Gug#1956

0 notes

Photo

Hôtel du Nord (Marcel Carné, 1938)

"Ce n’est pas un étranger, c'est un orphelin."

The first word a stone, the second one a nugget of humanity.

#Hotel du Nord#Marcel Carne#humanism#Jean Aurenche#Henri Jeanson#French film#French cinema#1930s movies

0 notes

Link

#the hunchback of notre dame#the hunchback#jean delannoy#jean aurenche#jacques prevert#Jacques Prévert#gina lollobrigida#anthony quinn#jean danet#based on#novel#victor hugo#remake#drama#history#france#italy#alain curry#valentine tessier#daneille dumont#horror#horror film#horror films#horror movie#horror movies#horror fan#horror fans#horror review#horror reviews#horror reviewer

0 notes

Text

CLAUDE AUTANT-LARA : LE BOURGEOIS ANARCHISTE

Claude Autant-Lara a été un des grands cinéastes français de la période 1940-1960. Il en a donné maintes fois la preuve, c’est un artiste et il sait ensuite injecter une méchanceté toute personnelle à ce qu’il veut dénoncer et user du vitriol. Son œuvre est inégale et comporte une inévitable part de films sans intérêt. Mais on lui doit quelques chefs-d’œuvre et une bonne dizaine d’œuvres…

View On WordPress

#bourvil#brigitte bardot#claude autant lara#gerard philipe#jean aurenche#jean gabin#max douy#michèle morgan#michel simon#nouvelle vague#pierre bost#rene cloerec

0 notes

Photo

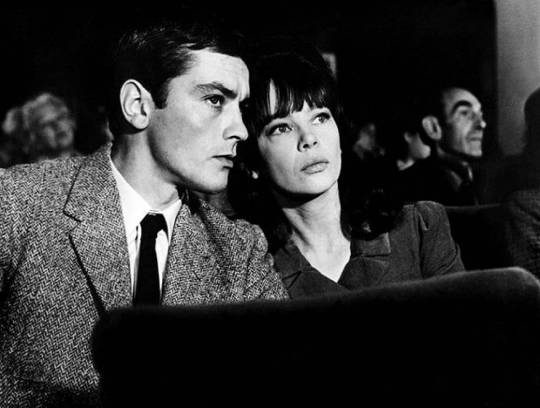

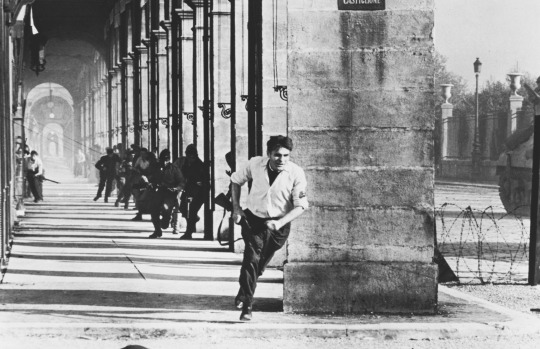

Is Paris Burning? (aka Paris brûle-t-il ?) is a 1966 film about the liberation of Paris in August 1944 by the French Resistance and the Free French Forces during World War II.

A French-American co-production, it was directed by French filmmaker René Clément, with a screenplay by Gore Vidal, Francis Ford Coppola, Jean Aurenche, Pierre Bost and Claude Brulé, adapted from the 1965 book of the same title by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre.

The film stars an international ensemble cast that includes French (Jean-Paul Belmondo, Alain Delon, Bruno Cremer, Pierre Vaneck, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Leslie Caron, Charles Boyer, Yves Montand), American (Orson Welles, Kirk Douglas, Glenn Ford, Robert Stack, Anthony Perkins, George Chakiris) and German (Gert Fröbe, Hannes Messemer, Ernst Fritz Fürbringer, Harry Meyen, Wolfgang Preiss) stars.

All sequences featuring French and German actors were filmed in their native languages and later dubbed in English, while all the sequences with the American actors (including Welles) were filmed in English. Separate French and English-language dubs were produced.

#is paris burning?#1960s#paris brûle-t-il#rené clément#france#alain delon#jean-paul belmondo#jean paul belmondo#orson welles#anthony perkins#george chakiris#gert fröbe#gert frobe#ww2#second world war#world war two#the eiffel tower#leslie caron

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

jean aurenche, marie-berthe aurenche, max ernst follow the light

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean Gabin and Bourvil in Four Bags Full aka The Crossing of Paris aka Pig Across Paris (Claude Autant-Lara, 1956)

Cast: Jean Gabin, Bourvil, Louis de Funès, Jeanette Batti, Georgette Anys, Robert Arnoux, Laurence Badie, Jacques Marin, Jean Dunot, MonetteDinay. Screenplay: Jean Aurenche, Pierre Bost, based on a story by Marcel Aymé. Cinematography: Jacques Natteau. Production design: Max Douy. Film editing: Madeleine Gug. Music: René Cloërec.

Like most movie-lovers whose knowledge of film extends beyond "Hollywood," I was familiar with Jean Gabin, but although I had encountered the name, I didn't know Bourvil, celebrated in France but not so much on this side of the Atlantic. Which made it difficult for me at first to capture the tone and humor of La Traversée de Paris, a film also known as Four Bags Full, The Crossing of Paris, The Trip Across Paris, and Pig Across Paris. Since the film begins with newsreel footage of German troops occupying Paris in 1942, it strikes a more serious tone than it eventually takes. Marcel Martin (Bourvil) is a black market smuggler tasked with carrying meat from a pig that's slaughtered at the beginning of the movie while he plays loud music on an accordion to cover its squeals. He's responsible for transporting two suitcases filled with pork across the city to Montmartre, but when the other smuggler fails to show up, he has to accept the aid of a stranger, Grandgil (Gabin), who agrees to carry the other two valises. Grandgil, however, wants the butcher, Jambier (Louis de Funès), to pay much more than the originally agreed-upon amount for his services, and blackmails him into accepting, to the consternation of Martin. The task is perilous, given the vigilance of the French police and the German occupying troops, so the film wavers between thriller and comedy -- the latter particularly when some stray dogs pick up the scent of what's in the suitcases. It ends up being a fascinating tale of the odd-couple relationship between Grandgil and Martin, as well as a picture of what Parisians went through during the occupation. It was controversial when it was released because it takes a warts-and-all look at black-marketeers and the Résistance, downplaying the heroism without denying the genuine risks they took. Eventually, Grandgil and Martin are caught by the Germans, but Grandgil is released because the officer in charge recognizes him as a famous artist. Martin is sent to prison, but the two are reunited after the war when Grandgil recognizes him at a train station as the porter carrying his luggage -- a rather obvious, and somewhat sour, bit of irony.

#La Traversée de Paris#Four Bags Full#The Crossing of Paris#Pig Across Paris#Claude Autant-Lara#Jean Gabin#Bourvil

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Douce (Claude Autant-Lara, 1943).

#douce#douce (1943)#claude autant-lara#odette joyeux#roger pigaut#philippe agostini#madeleine gug#jacques krauss#jean aurenche#pierre bost#michel davet

22 notes

·

View notes