#Japanese philosophy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Moving to Japan many years ago and being introduced more meticulously to its culture, history, and philosophy sparked a deep and lasting fascination that took root within me. Through extensive reading, research, observation, and reflection, it offered me valuable insights that, for some reason, blended organically with my own Balkan mentality. Japanese thought is like a quiet, endless ocean - vast and mysterious, yet full of deep truths for those curious to explore its depths. It’s not only that we can learn from it - it’s that we are drawn to it. The soul, restless and searching for meaning, finds itself captivated by its quiet elegance, by wisdom that is not shouted but whispered, like a secret offered in the stillness of the night. Herein lies its true beauty: it doesn’t force itself on you, it invites. It calls the spirit to explore the unknown, to face its own shadows, and in doing so, to find peace.

Here are a few philosophical principles that I find deeply compelling, each reflecting a unique idea or value within the expansive spectrum of Japanese aesthetics, ethics, and spirituality:

In the philosophy of "kensho" (見性), the gradual awakening to one's true self, there is a calm defiance against the rush of modern life. How easily we are deceived into thinking self-worth is built overnight, but Japanese thought insists on a far more patient, sometimes demanding journey - a slow, deliberate peeling away of the surface until only the real essence of the self remains. This is not comfort, but truth, and the search for truth is never without a bit of struggle. Yet in this struggle, in this slow awakening, there is beauty - one that cannot be grasped by those who seek only the fleeting joys of instant satisfaction.

Much like "bushidō" (武士道), the way of the warrior, this journey demands honor, integrity, and the kind of inner strength that does not waver, no matter how treacherous the path, a kind of inner strength that stands resolute in all circumstances. Bushidō embodies Gi (rectitude), Yū (courage), Jin (benevolence), Rei (respect), Makoto (honesty), Meiyo (honor), Chūgi (loyalty), and Jisei (self-control). It is not simply enduring hardship - it is about living with powerful intention, where loyalty, integrity, and courage form the foundation of a purposeful life. This spirit of Bushidō isn't about suffering but about a fierce dedication to living with honor and resilience, and within that struggle, one’s character is shaped. There is no arrogance in true confidence, only a hard-won resilience, the kind that grows in the cracks like a delicate flower breaking through stone.

Then comes "shibumi" (渋み) - that quiet, understated elegance that goes almost unnoticed, simplicity hiding a depth of complexity. True self-esteem, true understanding, doesn’t need to shout. It exists in the way a person holds themselves, moves through the world with calm, steady presence that speaks volumes without saying a word. This is confidence born not from pride but from humility, from understanding one’s place in the larger order of things, and finding peace in that awareness.

The beauty of "wabi-sabi" (侘寂) lies in its celebration of imperfection. It rejects the idea of flawless perfection and instead finds beauty in the cracks of imperfection and flaws. There is something both bittersweet and freeing in this acceptance - that we are all, in some way, broken, and it is through those very fractures that we find our true beauty. It’s a perspective that would resonate deeply with Dostoyevsky, who found humanity in the brokenness of his characters.

Perhaps the greatest gift of Japanese philosophy is the concept of "yūgen" (幽玄), that deep, elusive beauty lying just beyond reach, in the shadows and the unseen. Life is not meant to be fully understood, and some things are better left as mysteries. This unknowable depth gives life its meaning, its richness. The surface may seem dark, but beneath lies an entire world for those willing to look deeper, to feel with their soul, rather than just see with their eyes.

Finally, there is "fudōshin" (不動心) - the unshakable mind. To be calm, to be still, in the face of the storm - that is where true strength lies. It lies not in the victory and worldly achievements, triumph or success, but in the calm, steady enduring of life’s storms. This is the magnetic presence that draws others in, not through force or charm, but through the quiet power of someone who has faced the abyss and emerged, not untouched, but unbroken.

In Japanese philosophy, I’ve found a mirror to the human condition - beautiful, tragic, profound, and endlessly deep. It teaches us that self-esteem, like life, is not something to be attained in a moment, but something to be continuously sought, patiently, through humility and acceptance. There is no end to this journey, and in that endlessness lies its greatest beauty.

#personal entries#japanese philosophy#cultural reflections#wisdom and resilience#philosophical musings#見性#kensho#武士道#bushido#渋み#shibumi#侘寂#wabi sabi#幽玄#yugen#不動心#fudoshin#日本#japan#soulful insights#musings#hero's journey

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-sabi is a traditional Japanese aesthetic and worldview centered on the acceptance and appreciation of imperfection, impermanence, and the incomplete. It is deeply rooted in Buddhist teachings, particularly those relating to the transience of life. The philosophy of wabi-sabi celebrates the beauty found in simplicity, humility, and natural processes. Here’s an exploration of its core principles and concepts:

1. Impermanence (Mujō)

Transience of Life: Central to wabi-sabi is the Buddhist concept of impermanence (mujō), which acknowledges that all things are in a constant state of flux and decay. This perspective encourages an appreciation for the present moment and the beauty of fleeting experiences.

Natural Aging: Wabi-sabi finds beauty in the natural aging process. The patina of wear and the signs of use on objects are celebrated as they reveal the passage of time and the story of their existence.

2. Imperfection (Wabi)

Beauty in Flaws: Wabi-sabi embraces the idea that nothing is perfect, and it is in the imperfections that true beauty resides. This could be seen in asymmetry, roughness, and the uniqueness of handmade objects.

Simplicity and Humility: The wabi aspect emphasizes simplicity and humility. It values modest, rustic beauty over ostentatious or overly elaborate designs. This often translates to an aesthetic of minimalism and restraint.

3. Incompleteness (Sabi)

Unfinished and Evolving: The sabi aspect of wabi-sabi appreciates the incomplete and the evolving nature of things. It suggests that beauty is a process, not a fixed state, and that objects and experiences are always in a state of becoming.

Quietness and Serenity: Sabi also conveys a sense of quietness and serenity. It reflects a meditative quality, an appreciation for solitude and the tranquility found in understated beauty.

4. Connection to Nature

Natural Materials: Wabi-sabi often involves the use of natural materials that age gracefully over time, such as wood, stone, and clay. These materials reflect the organic processes of growth and decay inherent in nature.

Organic Forms: The aesthetic favors organic, irregular forms that mimic the irregularities found in nature, as opposed to geometric perfection.

5. Mindfulness and Presence

Living Mindfully: Embracing wabi-sabi encourages living mindfully and being present in the moment. It’s about appreciating the here and now, and finding contentment in the current state of things, despite (or because of) their imperfections.

Acceptance: Wabi-sabi involves accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay, and finding peace and contentment in this acceptance. It’s about letting go of the pursuit of perfection and embracing the reality of impermanence.

Examples in Practice

Tea Ceremony: The Japanese tea ceremony is a quintessential example of wabi-sabi in practice. The ceremony emphasizes simplicity, natural materials, and the appreciation of imperfections in the tea utensils, such as a crack in a teacup that adds character and history.

Kintsugi: The art of kintsugi, where broken pottery is repaired with gold or silver lacquer, highlights the philosophy of wabi-sabi. It transforms damage into beauty, celebrating the history and imperfection of the object.

Gardens: Traditional Japanese gardens often embody wabi-sabi principles with their asymmetrical layouts, natural elements, and deliberate incorporation of aged or weathered features.

The philosophy of wabi-sabi offers a profound shift in how we perceive beauty and value in the world. By embracing imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness, wabi-sabi encourages us to find beauty in the everyday, to appreciate the simple and humble aspects of life, and to cultivate a deep connection with the natural world. It is a reminder to live mindfully, to cherish the present moment, and to find peace in the ebb and flow of life’s inevitable changes.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#Wabi Sabi#Japanese Philosophy#Impermanence#Imperfection#Incompleteness#Buddhist Teachings#Natural Aging#Simplicity#Humility#Organic Forms#Mindfulness#Tea Ceremony#Kintsugi#Traditional Gardens#Aesthetic Principles#Transience#Rustic Beauty#Minimalism#Cultural Philosophy

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

#YUTORI is a Japanese philosophy - encourages us to slow down, savor the moment and makes room for what truley matters

@samirafee

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Watsuji Tetsuro#Tetsuro#climate#philosophy#Japanese philosophy#book cover#cover design#nature#environment#Geoffrey Bownas

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had my first tea ceremony with kimono at MAIKOYA. The staffs were professional, patient and polite. They speak simple English with a mix of Japanese which is understandable if you know a few phrases.

I was brought to the waiting area next to a Japanese Garden, where they encouraged me to go to the toilet first as it'll be harder to do your toilet business once you're dressed in your kimono.

Once I'm done, the staffs gave me a nice handbag matching my kimono for me to put my personal belongings like wallet, phone and keys that I will carry with me, walking around in my kimono.

A second bag, a bigger one is given to put my backpack and jacket, as it will be stored safely at their place while you have your tea ceremony or walk around the city in your kimono with handbag.

I was given time to walk around anywhere with my kimono for as long as I returned before the store is closed for the day, so an hour before it closes is recommended as you'll need time to change back.

I'm surprised by how warm the layers of kimono are able to provide me, considering I walk around Kyoto in the evening autumn weather of 8 degrees Celsius. Even the socks are warm enough.

The tea ceremony itself takes about an hour plus as the tea master explains to you the history and philosophies, its cultural significance and purpose, before demonstrating to you the actual one.

She explains to me patiently and clearly, what is expected of me during the actual ceremony like rituals, when to bow, how to bow, when to receive the tea, how to receive it, etc.

After that you're given a chance to do it yourself so you can enjoy and understand the process, and of course, taste your own matcha tea which you prepared for yourself! It's not as easy it seems!

But don't worry it's not as rigid as it sounds! It's actually enjoyable and interesting! The atmosphere is relaxing and calming. The tea master is friendly and casual, like talking to someone you know.

You just have to observe basic courtesy and common sense during the actual ceremony itself which is only a few minutes. I've read reviews where some tourists chat endlessly, please don't do that.

After the ceremony, there are photo taking sessions where the tea master help you to take photos in the teahouse and garden. The tea master will thank you and bid you farewell after it is all done.

What she said to me, made me tear up a little.

"I am so happy to see you wearing my kimono and learning my culture. Thank you for choosing to come to my country. Please enjoy your stay and I hope you will find happiness. May we meet again."

Ichi-go ichi-e is the term she used to describe the experience. One moment, one chance. You may experience the tea ceremony again next time, but it won't feel exactly the same as it is now.

Maybe the tea master would be a different person, the tea room will be a different one, the weather will be different, your life experiences by then will change you making you different as well.

So the key thing learnt is that appreciate and enjoy the present.

#japan#tea ceremony#japanese culture#japanese tradition#japanese philosophy#ichigo ichie#my japan trip 2024#kimono

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#philosophy thoughts#important#vagabond#miyamoto musashi#japanese philosophy#japanese tradition#japanese culture#motivational#motivation#get motivated#inspirational#inspiration#dragon ball#dragon ball z#naruto#one piece#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#dbz

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

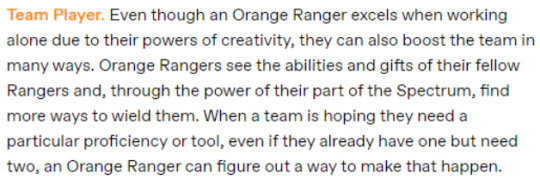

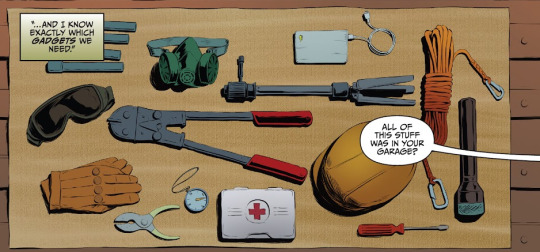

#web weaving#Eugene Skull Skullovitch#boom! comics power rangers#helluva boss#shattered grid#Ranger Slayer one-shot#go go power rangers#japanese philosophy#spongebob time cards#woyote#watership down graphic novel#the last unicorn graphic novel#crow time webtoons#fantasia 200#the chronicles of narnia#latin phrases#butterfly weed#carnelian gem#theme: one realm or the other; mighty morphin orange is Skull

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekend Book Reviews: Kakuzo Okakura's "The Book of Tea"

Kakuzo Okakura’s “The Book of Tea” stands as a timeless classic in the realm of literature, philosophy, and cultural studies. Originally published in 1906, this small yet profound work continues to captivate readers with its eloquent exploration of tea and its deep-seated significance in Japanese culture and beyond. At its heart, Okakura’s book is a philosophical treatise, elegantly weaving…

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A stone-sculpted image of Nyoirin Kannon Bodhisattva (如意輪観音菩薩) on the grounds of Han’nyaji Temple (般若寺) in Nara

Photo by Matsumoto Zen’ya (松本善也), 1955

Image from the photography collection of the Nara Prefectural Library

#buddhist art#如意輪観音菩薩#如意輪観音#nyoirin kannon#観音菩薩#観音#kannon#avalokitesvara#石仏#sekibutsu#奈良市#nara#buddhist temple#般若寺#hannyaji#japanese philosophy#松本善也#matsumoto zenya#historic photo#vintage photography

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Zen

The philosophy of Zen is a branch of Mahayana Buddhism that emphasizes direct experience, mindfulness, and the attainment of enlightenment through meditation and intuitive insight rather than through doctrinal study or ritualistic practices. Originating in China as Chan Buddhism and later flourishing in Japan as Zen, this philosophy seeks to transcend the dualities of ordinary thought and to awaken to the true nature of reality, which is seen as beyond conceptual understanding.

Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Zen:

Direct Experience and Enlightenment (Satori):

Immediate Awareness: Zen emphasizes direct, immediate experience as the path to enlightenment (satori). This means engaging with reality without the interference of conceptual thought or the ego, often through practices such as meditation (zazen) and mindful awareness.

Satori: Enlightenment in Zen, known as satori, is often described as a sudden, profound realization of the interconnectedness of all things and the emptiness (śūnyatā) that underlies reality. This insight transcends ordinary understanding and reveals the true nature of existence.

Meditation (Zazen):

Seated Meditation: Zazen, or seated meditation, is the core practice of Zen. It involves sitting in a specific posture, focusing on the breath, and observing thoughts without attachment. The aim is to quiet the mind, develop concentration, and eventually experience deep states of awareness and insight.

Beyond Techniques: While zazen is a formal practice, Zen teaches that meditation can extend into all aspects of life, encouraging practitioners to bring the same mindfulness and presence into everyday activities.

Koans and Paradoxes:

Koans: Koans are paradoxical statements or questions used in Zen practice to transcend logical thinking and provoke direct insight. A well-known example is, "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" The purpose of a koan is not to find a logical answer but to break down the barriers of conventional thought and open the mind to a more profound reality.

Beyond Rationality: Zen often challenges the limits of rationality, using paradox and contradiction to point out that true understanding is beyond intellectual comprehension.

Non-Dualism and Emptiness (Śūnyatā):

Transcending Duality: Zen philosophy rejects the dualistic thinking that separates the self from the world, subject from object, and good from bad. Instead, it teaches that all distinctions are illusory and that true reality is non-dual.

Emptiness: The concept of emptiness (śūnyatā) is central to Zen. It refers to the idea that all things are interconnected and lack an independent, permanent essence. Understanding this emptiness is key to realizing the impermanent and interdependent nature of reality.

Mindfulness and Present-Moment Awareness:

Living in the Present: Zen encourages practitioners to live fully in the present moment, without attachment to the past or anxiety about the future. This mindfulness is cultivated in both formal meditation and daily activities.

Mindful Action: Zen teaches that any action, no matter how mundane, can be an opportunity for mindfulness and awareness. The concept of "being one with the task" is emphasized, where the distinction between the doer and the deed dissolves.

Simplicity and Naturalness:

Simplicity: Zen values simplicity in both thought and lifestyle. This is reflected in Zen art, architecture, and daily practices, which emphasize naturalness, austerity, and the beauty of the unadorned.

Natural Flow: Zen encourages a natural way of being, in harmony with the flow of life. This idea is often illustrated by metaphors of nature, such as the effortless way a tree grows or a river flows.

Compassion and Ethical Living:

Bodhisattva Ideal: Although Zen emphasizes direct personal experience, it also upholds the Mahayana Buddhist ideal of the bodhisattva—someone who seeks enlightenment not just for themselves but for the benefit of all beings. Compassion and ethical conduct are integral to this path.

Engaged Buddhism: In modern times, Zen has also inspired forms of engaged Buddhism, where mindfulness and ethical living are applied to social, environmental, and political issues.

Art, Aesthetics, and Expression:

Zen Arts: Zen has profoundly influenced Japanese arts, including tea ceremony, calligraphy, poetry (such as haiku), and gardening. These arts embody the principles of simplicity, mindfulness, and the transient nature of existence.

Expression of Enlightenment: In Zen, artistic expression is often seen as an extension of the meditative mind. The spontaneity and directness found in Zen arts reflect the same qualities valued in Zen practice.

Non-Attachment and Letting Go:

Letting Go of Ego: Zen teaches the importance of letting go of the ego, desires, and attachments that create suffering. By relinquishing these attachments, one can experience a deeper, more peaceful state of being.

Non-Striving: Paradoxically, Zen teaches that enlightenment cannot be attained through effort alone; it requires a state of non-striving, where one lets go of the desire for enlightenment and simply allows it to arise naturally.

Silence and the Ineffable:

Beyond Words: Zen often emphasizes the limitations of language in capturing the essence of reality. Many Zen teachings are conveyed through silence or direct, non-verbal actions, highlighting that the deepest truths cannot be fully expressed in words.

Ineffability of Truth: Zen suggests that true understanding comes from direct experience, not from intellectual discussion or analysis. This is reflected in the Zen saying, "The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon," indicating that teachings are merely pointers to the truth, not the truth itself.

The philosophy of Zen offers a unique approach to understanding the nature of reality and the self, emphasizing direct experience, mindfulness, and the transcendence of dualistic thinking. By cultivating a deep awareness of the present moment and embracing the simplicity and natural flow of life, Zen practitioners seek to realize the interconnectedness of all things and attain enlightenment. This philosophy has had a profound influence on both Eastern and Western thought, inspiring not only spiritual practice but also art, literature, and approaches to everyday living.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#metaphysics#ontology#psychology#Zen Buddhism#Mindfulness#Non-Dualism#Meditation (Zazen)#Enlightenment (Satori)#Koans#Emptiness (Śūnyatā)#Present-Moment Awareness#Simplicity#Zen Arts#Non-Attachment#Bodhisattva Ideal#Engaged Buddhism#Spiritual Practice#Japanese Philosophy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Truth is found in the way. The way is found in nature. Nature is found within yourself, and yourself is found in the way." - Miyamoto Musashi

#bushido#samurai#warrior way#japanese philosophy#inspiration#motivation#truth#nature#self discovery#personal growth#mental toughness#quotestoliveby#mentaltoughness#mindfullness#self awareness#balance#inner peace#wisdom

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

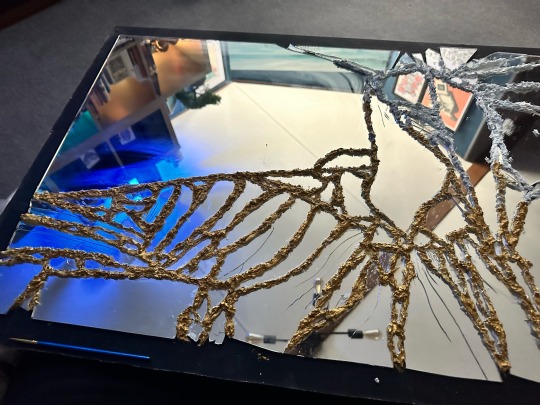

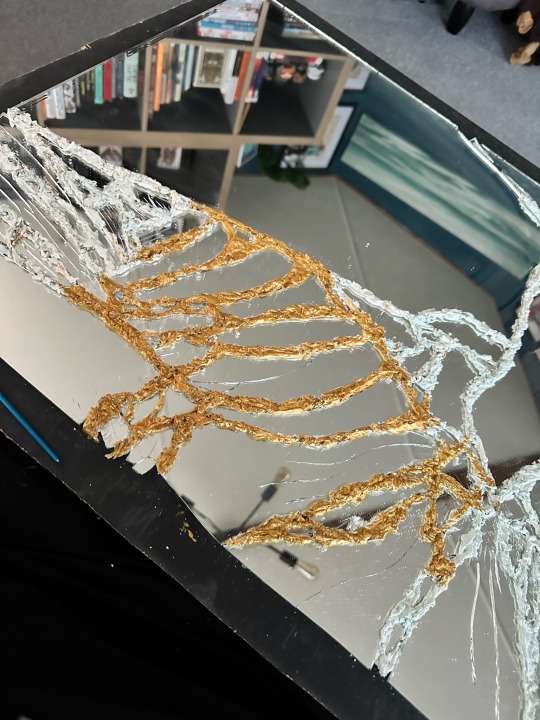

How I've been spending my evening so far…. Dog sitting Pip at mine while the family are out for the night, watching movies and finally getting round to pollyfilling my broken mirror and painting it gold in the style of Kintsugi! This art form appeals to me a lot as it's about highlighting the imperfections, that something broke can be repaired and be reused again! I can relate to that philosophy in a lot of ways, being imperfect, being broken but always working to improve myself!

It'll be a wonderful focal piece above my radiator at the entranceway and something I can be proud of creating!

#personal#kintsugi#kintsugi art#japanese philosophy#Japanese kintsugi#upcycle#upcycling#new home project 2023#renovation#home art#artwork#physical art#my doggo#home 2023

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Travel Diary : The Postcard Seller in Kyoto

Got this beautiful postcards at a little stall by the roadside near the entrance to the Bamboo Forest in Arashiyama.

Seller is a kind man looks to be in his 50s. He explains that the lovely drawings are his wife who spent years learning to draw as a hobby. She got sick recently and retired but she continues to share her love of drawing and her country with tourists like me.

He was enthusiastic and put tremendous effort to speak English. My Japanese is still a work in progress and I was a little embarrassed to speak in Japanese but was touched by his story. It’s one of the things that motivate me to learn Japanese so I could speak to the locals.

He thanked me for buying his postcards and the last sentence was what got me, “Thank you for loving my country. Hope to see you again.” After which he proceeded to show me the direction to the Bamboo Forest and bow in gratitude before he returned to his stall.

It’s one of the many encounters in Japan that I will remember for life. Their sense of hospitality or Omotenashi, where they go above and beyond for their guests will always amazed me. They take pride in their job no matter how “trifle” or “unglamorous” it may seem to others.

Something I wish people in my own country would understand. Sadly, we are still being judged by what we do, based on personal experience working as a delivery rider when I hit rock bottom in life. My “peers” used to say “how long are you going to work this job”?

While in Japan, they would say, “it’s a good job where you send food to busy and hungry people”. Whoever you are, wherever you are, I hope you can be proud of your job. Keep doing what you are doing. Others will always judge you no matter what job you do.

#travel diary#japan#kyoto#arashiyama#japan trip#japan travel#life lesson#japanese philosophy#japanese hospitality#omotenashi#japanese art#story time#bamboo forest

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The worst thing about the samurai is that they devoted everything towards obedience and loyalty to their master. When I think about the idea of the freedom of action that comes from the death drive they embraced, I think "imagine what they could be without obedience".

When reading the Hagakure, you get many expressions of the idea of death, meditation upon death, or to live as if you are already dead, as the key to unlimited freedom of action. The way of the samurai is even more broadly described as "desperation" or even "insanity". There's even a section where Tsunemoto talks about people who were brave and rowdy because they had "vitality", versus people who were gentle because they lacked it, but the latter was not inferior to the former because they would still be "crazy to die".

But the only thing is, in the context of Bushido, all of that is wrapped in the idea that this was all meant to facilitate total obedience to master. The samurai had to act instantaneously so as to fulfill the commands of their lord without faltering.

What I'm saying is, imagine if you could have something of what the Hagakure hints at, in terms of how it figures full mental freedom of action, but in pursuit of the fulfillment of an anarchist insurrectionary agent rather than cultivating complete obedience to any lord?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a little description of Kintsugi for anyone who was left wanting to know more -

"Kintsugi can relate to the Japanese philosophy of mushin (無心, "no mind"), which encompasses the concepts of non-attachment, acceptance of change, and fate as aspects of human life. Also mono no aware, a compassionate sensitivity, or perhaps identification with, [things] outside oneself."

Make of that what you will.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miyamoto Musashi’s The Book of Five Rings

Understanding strategy from a samurai’s perspective might sound like a niche interest, but trust me, Miyamoto Musashi’s The Book of Five Rings is anything but narrow in scope. Written in the 1600s, it’s a brutally honest, no-fluff guide to winning in both martial arts and life. Honestly, it’s part swordplay manual, part life philosophy, and all kinds of fascinating. The lessons Musashi…

View On WordPress

#dailyprompt#empowerment#history#japanese philosophy#Kaizen#karate#martial arts#mindset#Miyamoto Musashi#Okinawa#personal growth#Self Defence#self improvement#survival mindset#training

0 notes