#Japanese Officials

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#youtube#militarytraining#US Department of State#Japanese Officials#Security Cooperation#Military Partnership#Japan Alliance#Defense Secretary Austin#Asian Allies#Secretary Blinken#Japan#United States#Bilateral Talks#International Relations#Tokyo#Foreign Policy#Diplomacy#Diplomatic Meeting#US-Japan Relations#East Asia#State Department#Press Conference#Blinken#Secretary of State#US Foreign Affairs#US-Japan Alliance#Japan Relations#Historic Trilateral Defense Meeting

0 notes

Text

Dungeon Meshi - Female Dwarf beards

#Adventurers bible#dungeon meshi#Dwarves#Namari#Marcille Donato#Love Namari for calling them out#I checked the original in japanese and it says hige which as far as I know translates as beard#not sure why it was translated as whiskers in the official translation#Dunmeshi Extra

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gendered pronouns in Japanese vs English

In Revolutionary Girl Utena, the main character Utena is a girl (it says so in the title), but very conspicuously uses the masculine first person pronoun 僕 (boku) and dresses in (a variation of) the boys school uniform. Utena's gender, and gender in general, is a core theme of the work. And yet, I haven’t seen a single translation or analysis post where anyone considers using anything other than she/her for Utena when speaking of her in English. This made me wonder: how does one’s choice of pronouns in Japanese correspond to what one’s preferred pronouns would be in English?

There are 3 main differences between gendered pronouns in Japanese vs English

Japanese pronouns are used to refer to yourself (first-person), while English pronouns are used to refer to others (third-person)

The Japanese pronoun you use will differ based on context

Japanese pronouns signify more than just gender

Let’s look at each of these differences in turn and how these differences might lead to a seeming incongruity between one’s Japanese pronoun choice and one’s English pronoun choice (such as the 僕 (boku) vs she/her discrepancy with Utena).

Part 1: First-person vs third-person

While Japanese does technically have gendered third person pronouns (彼、彼女) they are used infrequently¹ and have much less cultural importance placed on them than English third person pronouns. Therefore, I would argue that the cultural equivalent of the gender-signifying third-person pronoun in English is the Japanese first-person pronoun. Much like English “pronouns in bio”, Japanese first-person pronoun choice is considered an expression of identity.

Japanese pronouns are used exclusively to refer to yourself, and therefore a speaker can change the pronoun they’re using for themself on a whim, sometimes mid-conversation, without it being much of an incident. Meanwhile in English, Marquis Bey argues that “Pronouns are like tiny vessels of verification that others are picking up what you are putting down” (2021). By having others use them and externally verify the internal truth of one’s gender, English pronouns, I believe, are seen as more truthful, less frivolous, than Japanese pronouns. They are seen as signifying an objective truth of the referent’s gender; if not objective then at least socially agreed-upon, while Japanese pronouns only signify how the subject feels at this particular moment — purely subjective.

Part 2: Context dependent pronoun use

Japanese speakers often don’t use just one pronoun. As you can see in the below chart, a young man using 俺 (ore) among friends might use 私 (watashi) or 自分 (jibun) when speaking to a teacher. This complicates the idea that these pronouns are gendered, because their gendering depends heavily on context. A man using 私 (watashi) to a teacher is gender-conforming, a man using 私 (watashi) while drinking with friends is gender-non-conforming. Again, this reinforces the relative instability of Japanese pronoun choice, and distances it from gender.

Part 3: Signifying more than gender

English pronouns signify little besides the gender of the antecedent. Because of this, pronouns in English have come to be a shorthand for expressing one’s own gender experience - they reflect an internal gendered truth. However, Japanese pronoun choice doesn’t reflect an “internal truth” of gender. It can signify multiple aspects of your self - gender, sexuality, personality.

For example, 僕 (boku) is used by gay men to communicate that they are bottoms, contrasted with the use of 俺 (ore) by tops. 僕 (boku) may also be used by softer, academic men and boys (in casual contexts - note that many men use 僕 (boku) in more formal contexts) as a personality signifier - maybe to communicate something as simplistic as “I’m not the kind of guy who’s into sports.” 俺 (ore) could be used by a butch lesbian who still strongly identifies as a woman, in order to signify sexuality and an assertive personality. 私 (watashi) may be used by people of all genders to convey professionalism. The list goes on.

I believe this is what’s happening with Utena - she is signifying her rebellion against traditional feminine gender roles with her use of 僕 (boku), but as part of this rebellion, she necessarily must still be a girl. Rather than saying “girls don’t use boku, so I’m not a girl”, her pronoun choice is saying “your conception of femininity is bullshit, girls can use boku too”.

Through translation, gendered assumptions need to be made, sometimes about real people. Remember that he/they, she/her, they/them are purely English linguistic constructs, and don’t correspond directly to one’s gender, just as they don’t correspond directly to the Japanese pronouns one might use. Imagine a scenario where you are translating a news story about a Japanese genderqueer person. The most ethical way to determine what pronouns they would prefer would be to get in contact with them and ask them, right? But what if they don’t speak English? Are you going to have to teach them English, and the nuances of English pronoun choice, before you can translate the piece? That would be ridiculous! It’s simply not a viable option². So you must make a gendered assumption based on all the factors - their Japanese pronoun use (context dependent!), their clothing, the way they present their body, their speech patterns, etc.

If translation is about rewriting the text as if it were originally in the target language, you must also rewrite the gender of those people and characters in the translation. The question you must ask yourself is: How does their gender presentation, which has been tailored to a Japanese-language understanding of gender, correspond to an equivalent English-language understanding of gender? This is an incredibly fraught decision, but nonetheless a necessary one. It’s an unsatisfying dilemma, and one that poignantly exposes the fickle, unstable, culture-dependent nature of gender.

Notes and References

¹ Usually in Japanese, speakers use the person’s name directly to address someone in second or third person

² And has colonialist undertones as a solution if you ask me - “You need to pick English pronouns! You ought to understand your gender through our language!”

Bey, Marquis— 2021 Re: [No Subject]—On Nonbinary Gender

Rose divider taken from this post

#langblr#japanese#japanese language#language#language learning#linguistics#learning japanese#utena#revolutionary girl utena#shojo kakumei utena#rgu#sku#gender#transgender#nonbinary#trans#official blog post#translation#media analysis

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

happy year of the dragon from this guy…

#something deeply wrong with him (affectionate)#also#eyeing the third panel like: hm. this too is yuri.#this is art ryoko kui posted to her official blog by the way#i just translated it from japanese#dungeon meshi#lunar new year#year of the dragon#manga#falin#laois#marcille#art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

902 notes

·

View notes

Text

We hope you are staying cool during this hot summer. The sunlight is so strong that it could turn you into a dried fish, but the young people of this region seem to be used to it.

Don't forget to take precautions against the heat and enjoy the summer!

#splatoon 3#splatoonusna#nintendo#nintendo switch#the official na post was...very sad translation wise so i just altered the japanese text a bit since it's a lot cuter

739 notes

·

View notes

Text

Works by Yoshitomo Nara ⋆。° ★

#archive#photo archive#art archive#yoshitomo nara#shoujo girl#shoujo#aesthetic#drawing#art inspo#2000s japan#japanese art#mixed media#color palette#2000s anime#anime art#2000s manga#manga art#manhwa#nana#ai yazawa#paradise kiss#kimi ni todoke#kamisama kiss#ao haru ride#lily chou chou#nastyona#lamp#official art

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

スヌーピー“顔を出す”シュークリーム

#snoopy#peanuts#food#dessert#cream puff#official product#from official photo#transparent#my edit#do not repost#cute#png#I just think it's cute#site link#snoopy “shows his face” cream puffs#source: hilton hotel japan#shu cream = cream puffs in japanese

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

just an austrian giant clutching a little blonde twink by the waist, soaked in champagne, hoping that this feeling never ends

#this race actually won both of them their championships#nico's wouldn't be official until abu dhabi but this is the race that won him 2016#nico rosberg#toto wolff#japanese gp 2016

347 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's 25-ji, Nightcord de.'s artworks from the 3rd anniversary site!

#project sekai#25 ji nightcord de#boring trivia: the group image is called nightcode in the site data. if you've been around long enough you might recognise it as a common#localisation of the unit name before the official EN one came about#also mafuyu is called mahuyu#these are just alternate localisations ig. like when you pronounce nightcord and mafuyu in japanese they sound like nightcode and mahuyu

895 notes

·

View notes

Text

i want to be a macoto takahashi's girl ♡

like/reblog

#macoto takahashi#anime art#manga art#manga aesthetic#manga and stuff#manga#anime and manga#manga screencap#manga panel#art style#artwork#japanese art#official art#mangacore#shoujo manga#shoujo#retro#vintage#manga retro#retro shojo#vintage shojo#vintage manga#icons#twitter icons

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Live"

"Who you are and where you've come from, might never be known. But even if you don't pass the patterns of all power, you're you."

#I'm so sad#note that I'm not an official translator#my translation might be different from what i understand in japanese because translating is HARD#bsd chuuya#bsd rimbaud#bsd fifteen

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been having trouble putting this idea into words so you’ll have to bear with me, but I was struck when I saw a Japanese news program interviewing foreign tourists in Japan, and some australian women were dubbed over with a stereotypically feminine speech register (lots of のs and わs), and my first thought was “they weren’t speaking that femininely in english”.

A friend of mine from the UK recently mentioned that he noticed that australia has a generally more masculine culture than england - he felt that everyone is a bit more masculine here, including women. This kind of confirmed to me that my impressions of the dubbing were right - the tourists were speaking in a relatively (internationally) more masculine way. Yet their dub made them sound so much more feminine.

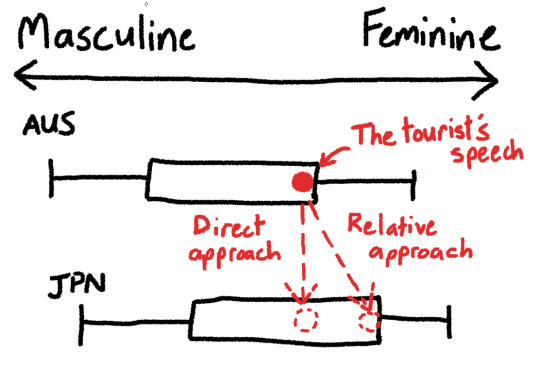

It made me wonder. When translating something, do you translate the manner of speaking “directly”, or “relatively” in terms of cultural norms? Maybe this graph will help me explain the question.

A direct appoach in this case might appear to a Japanese person to result in an unexpectedly masculine register, but preserves how the speaker's cultural upbringing has influenced their speech.

The news program translators chose the relative approach - I think I would prefer the direct approach. I think I prefer it because I believe translation should be a rewriting of the original utterance as if the speaker was originally speaking the target language, and the direct approach compliments that way of thinking the best.

Actually now that I type that, I’m second guessing myself. Does it? It does, if for the purposes of the “rewrite it as if they spoke japanese” thought experiment, we suppose the speaker magically learned japanese seconds before making the utterance, but what if we suppose the speaker magically grew up learning japanese - then maybe they would conform to the relative cultural values. But also, maybe they would never have said such a thing in the first place - their original utterance was informed by their upbringing and cultural values, so how could you possibly know what they would have said if they had known japanese from birth? Maybe my initial instinct was right after all?

If you work in translation, I’m very interested to hear if you have come across this problem and how you deal with it 🙏

Further reading: I think this question also ties into this problem I’ve been struggling to answer for a while.

#linguistics#language#langblr#japanese#japanese language#translation#jimmy blogthong#official blog post

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

987 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soooooo very normal about this skit btw

#for reference this is the japanese vas preparing for the anniversary#but they're acting in-character#and the voiced version is comedy gold#sw is the one narrating ren's reply and firefly switches to sam mid-message#they're so goofy i'm gonna die#honkai star rail#hsr#hsr kafka#hsr firefly#hsr sam#silver wolf#hsr blade#stellaron hunters#official media#edit: THE GROUP NAME HELLO??#“stellaron hunter family. lol”#i know what you are silver wolf

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

「Senran Kagura: New Link - UR 羽衣(爆乳祭・弐)」

#senran kagura: new link#senran kagura#閃乱カグラ#ui#japanese clothes#official art#mypost#mypost:senran kagura

100 notes

·

View notes