#Isao Zushi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

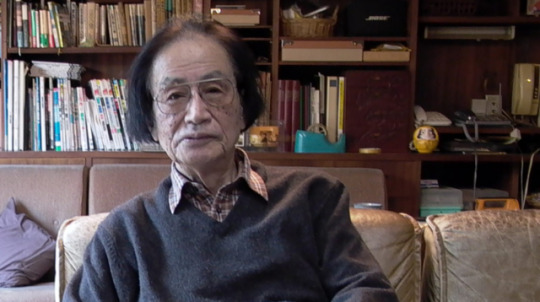

Underrated Godzilla suit actors.

They need more love!!!

Shinji Takagi

Isao Zushi

Toru Kawai (passed in 1996)

Mizuho Yoshida

#godzilla#suitmation#kaiju#godzilla suit actor#godzilla suit actors#shinji takagi#isao zushi#mizuho yoshida#toru kawai#gojira#suit actor#showa era#showa godzilla#millennium#millennium godzilla

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films Watched in 2024: 30. ゴジラ対メカゴジラ/ Gojira tai Mekagojira/Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) - Dir. Jun Fukuda

#ゴジラ対メカゴジラ#Gojira tai Mekagojira#Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla#Jun Fukuda#Masaaki Daimon#Kazuya Aoyama#Akihiko Hirata#Reiko Tajima#Hiroshi Koizumi#Masao Imafuku#Beru-Bera Lin#Shin Kishida#Gorō Mutsumi#Isao Zushi#Ise Mori#Kinichi Kusumi#Godzilla#Mechagodzilla#King Caesar#Anguirus#Films Watched in 2024#My Edits#My Post

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Spirit of Godzilla - Godzilla Suit Actors

Haruo Nakajima (1954-1972)

Isao Zushi (1974)

Kenpachiro Satsuma (1984-1995)

Mizuho Yoshida (2001)

Tsutomu Kitagawa (1999-2000/2002-2004)

#the spirit of godzilla#haruo nakajima#isao zushi#kenpachiro satsuma#mizuho yoshida#tsutomu kitagawa#godzilla#中島春雄#図師勲#薩摩剣八郎#吉田瑞穂#喜多川務#ゴジラ

308 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla 1974

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla - Jun Fukuda 1974

297 notes

·

View notes

Link

Originally, there was supposed to be a Double Inoue reunion with Kyoko Inoue and Takako Inoue facing Ayako Sato and Madeline but Kyoko can’t make it and Tsukasa Fujimoto will be taking her place. Yumi Fukawa will be debuting as a manager during that match. Interesting.. .as it was hinted she may see some ring action. In her condition, probably nothing too extreme and something more along the lines of Mika Nishio.

Much like Yumi honoring her senpai, Minoru will be honoring his senpai, Masakatsu Funaki who will be in the mainevent.

"Tanaka Minoru Promote-Zushi Sports Promotion Charity Tournament-1st Zushi Pro-Wrestling Festival" Date & Time: March 14 (Sat) 17:00 Start Venue: Kanagawa / Zushi City Gymnasium Main Arena

1. Shunsuke Sayama vs Kazuya Umizu 2. Zushi Sakurayanman debut match Zushi Sakurayanman & Isao Wada vs. Keizo Matsuda & Tetsuya Nakazato 3. Carbell Ito vs. Yoshihiro Doguchi 4. Women's wrestling tag team match Kyoko Inoue & Takako Inoue with Fukawa Tadami pair Ayako Sato & Madeleine 5. Masakatsu Funaki & Masamichi Marufuji vs Shiro Echunaka & Minoru Tanaka

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How tragic that man can never realize how beautiful life is until he is face to face with death.

Screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto (April 18, 1918 -- July 19, 2018) was one of Akira Kurosawa’s least-known collaborators, if only because he was not part of the director’s photogenic actors. But Hashimoto was more than just a Kurosawa collaborator. The screenwriter was raised in the Japanese countryside and was discharged from military service in World War II because of tuberculosis -- forcing him to spend four years in a veterans’ hospital. A fellow patient one day handed Hashimoto a magazine on cinema and, poring through the contents, it was then Hashimoto decided to pursue a career in filmmaking. He sent a screenplay to Mansaku Itami (a major figure of 1930s Japanese cinema, but whose films have largely not been distributed to the West), who was so impressed that he became the young Hashimoto’s mentor until his death in 1946.

Rashômon was Hashimoto’s screenwriting debut (and what a hell of a debut). Over the next several decades, Hashimoto’s films -- regardless of the director or actors involved -- would explore humanity from its most altruistic to its most unconscionable moments of cruelty. Hashimoto retired in 1982, having been with Toho Company for almost the entirety of his career. He passed away at a hundred years old in July -- the last of Kurosawa’s regular screenwriters living, and arguably the dean of that entire group.

Nine of his films are pictured above (left-right, descending):

Rashômon (1950) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Toshirô Mifune, Machiko Kyô, Masayuki Mori, Takashi Shimura, and Minoru Chiaki

Ikiru (1952) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Takashi Shimura, Shin’ichi Himori, Haruo Tanaka, Minoru Chiaki, Miki Odagiri, and Bokuzen Hidari

Seven Samurai (1954) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Toshirô Mifune, Takashi Shimura, Yoshio Inaba, Daisuke Katô, Seiji Miyaguchi, Minoru Chiaki, Isao Kimura, Yoshio Tsuchiya, and Bokuzen Hidari

I Live in Fear (1955) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Toshirô Mifune, Takashi Shimura, and Minoru Chiaki

Throne of Blood (1957) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Toshirô Mifune, Isuzu Yamada, Takashi Shimura, Akira Kubo, Hiroshi Tachikawa, and Minoru Chiaki

Harakiri (1963) -- directed by Masaki Kobayashi; also starring Tatsuya Nakadai, Rentarô Mikuni, Shima Iwashita, Akira Ishihama, and Yoshio Inaba

The Sword of Doom (1966) -- directed by Kihachi Okamoto; also starring Tatsuya Nakadai, Yûzô Kayama, Michiyo Aratama, and Toshirô Mifune

Dodes’ka-den (1970) -- directed by Akira Kurosawa; also starring Yoshitaka Zushi, Kin Sugai, Toshiyuki Tonomura, Shinsuke Minami, and Yûkô Kusunoki

Hakkodasan (1977) -- directed by Shirô Moritani; also starring Shôgo Shimada, Ken Takakura, Hideji Ôtaki, Kin'ya Kitaôji, Tetsurô Tanba, Rentarô Mikuni, Komaki Kurihara, Akira Hamada, Mariko Kaga, and Yûzô Kayama

#Shinobu Hashimoto#Rashomon#Ikiru#Seven Samurai#Throne of Blood#I Live in Fear#Harakiri#The Sword of Doom#Dodeskaden#Hakkodasan#Dodesukaden#Dodes'ka den#in memoriam

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

GODZILLA wiki

Godzilla From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the monster. For the film franchise, see Godzilla (franchise). For other uses, see Godzilla (disambiguation). "ゴジラ" redirects here. For other uses of "Gojira", see Gojira (disambiguation). ‹ The template Infobox character is being considered for merging. › Godzilla Godzilla film series character Godzilla '54 design.jpg Godzilla as featured in the original 1954 film First appearance Godzilla (1954) Created by Tomoyuki Tanaka Ishirō Honda Eiji Tsubaraya Portrayed by Shōwa era: Haruo Nakajima[1] Katsumi Tezuka[2] Hiroshi Sekida[3] Seiji Onaka[3] Shinji Takagi[4] Isao Zushi[5] Toru Kawai[5] Hanna-Barbera: Ted Cassidy (vocal effects)[6][7] Heisei era: Kenpachiro Satsuma[8] Millennium era: Tsutomu Kitagawa[9] Mizuho Yoshida[10] Shin Godzilla: Mansai Nomura[11] TriStar Pictures: Kurt Carley[12] Frank Welker (vocal effects)[13] Legendary Pictures: T.J. Storm[14][15] Designed by Akira Watanabe Teizô Toshimitsu[16] Information Alias The King of the Monsters[17] Gigantis[18] Monster Zero-One[19] The God of Destruction[20][21] Species Prehistoric amphibious reptile Family Minilla and Godzilla Junior (adopted sons) Godzilla (Japanese: ゴジラ Hepburn: Gojira) (/ɡɒdˈzɪlə/; [ɡoꜜdʑiɾa] (About this soundlisten)) is a monster originating from a series of Japanese films of the same name. The character first appeared in Ishirō Honda's 1954 film Godzilla and became a worldwide pop culture icon, appearing in various media, including 32 films produced by Toho, three Hollywood films and numerous video games, novels, comic books and television shows. It is dubbed the King of the Monsters, a phrase first used in Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, the Americanized version of the original film.

Godzilla is depicted as an enormous, destructive, prehistoric sea monster awakened and empowered by nuclear radiation. With the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Lucky Dragon 5 incident still fresh in the Japanese consciousness, Godzilla was conceived as a metaphor for nuclear weapons.[22] As the film series expanded, some stories took on less serious undertones, portraying Godzilla as an antihero, or a lesser threat who defends humanity. With the end of the Cold War, several post-1984 Godzilla films shifted the character's portrayal to themes including Japan's forgetfulness over its imperial past,[23] natural disasters and the human condition.[24]

Godzilla has been featured alongside many supporting characters. It has faced human opponents such as the JSDF, or other monsters, including King Ghidorah, Gigan and Mechagodzilla. Godzilla sometimes has allies, such as Rodan, Mothra and Anguirus, and offspring, such as Minilla and Godzilla Junior. Godzilla has also fought characters from other franchises in crossover media, such as the RKO Pictures/Universal Studios movie monster King Kong and the Marvel Comics characters S.H.I.E.L.D.,[25] the Fantastic Four[26] and the Avengers.[27]

Contents 1 Overview 1.1 Name 1.2 Characteristics 1.3 Roar 1.4 Size 1.5 Special effects details 2 Appearances 3 Cultural impact 3.1 Cultural ambassador 4 References 4.1 Sources 5 External links Overview Name Gojira (ゴジラ) is a portmanteau of the Japanese words: gorira (ゴリラ, "gorilla") and kujira (鯨クジラ, "whale"), which is fitting because in one planning stage, Godzilla was described as "a cross between a gorilla and a whale",[28] alluding to its size, power and aquatic origin. One popular story is that "Gojira" was actually the nickname of a corpulent stagehand at Toho Studio.[29] Kimi Honda, the widow of the director, dismissed this in a 1998 BBC documentary devoted to Godzilla, "The backstage boys at Toho loved to joke around with tall stories".[30]

Godzilla's name was written in ateji as Gojira (呉爾羅), where the kanji are used for phonetic value and not for meaning.[citation needed] The Japanese pronunciation of the name is [ɡoꜜdʑiɾa] (About this soundlisten); the Anglicized form is /ɡɒdˈzɪlə/, with the first syllable pronounced like the word "god" and the rest rhyming with "gorilla". In the Hepburn romanization system, Godzilla's name is rendered as "Gojira", whereas in the Kunrei romanization system it is rendered as "Gozira".[citation needed]

During the development of the American version of Godzilla Raids Again (1955), Godzilla's name was changed to "Gigantis", a move initiated by producer Paul Schreibman, who wanted to create a character distinct from Godzilla.[31]

Characteristics

Every film incarnation of Godzilla between 1954 and 2017 Within the context of the Japanese films, Godzilla's exact origins vary, but it is generally depicted as an enormous, violent, prehistoric sea monster awakened and empowered by nuclear radiation.[32] Although the specific details of Godzilla's appearance have varied slightly over the years, the overall impression has remained consistent.[33] Inspired by the fictional Rhedosaurus created by animator Ray Harryhausen for the film The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,[34] Godzilla's iconic character design was conceived as that of an amphibious reptilian monster based around the loose concept of a dinosaur[35] with an erect standing posture, scaly skin, an anthropomorphic torso with muscular arms, lobed bony plates along its back and tail, and a furrowed brow.[36] Art director Akira Watanabe combined attributes of a Tyrannosaurus, an Iguanodon, a Stegosaurus and an alligator[37] to form a sort of blended chimera, inspired by illustrations from an issue of Life magazine.[38] To emphasise the monster's relationship with the atomic bomb, its skin texture was inspired by the keloid scars seen on survivors in Hiroshima.[39] The basic design has a reptilian visage, a robust build, an upright posture, a long tail and three rows of serrated plates along the back. In the original film, the plates were added for purely aesthetic purposes, in order to further differentiate Godzilla from any other living or extinct creature. Godzilla is sometimes depicted as green in comics, cartoons and movie posters, but the costumes used in the movies were usually painted charcoal grey with bone-white dorsal plates up until the film Godzilla 2000.[40]

Godzilla's atomic heat beam, as shown in Godzilla (1954) Godzilla's signature weapon is its "atomic heat beam", nuclear energy that it generates inside of its body and unleashes from its jaws in the form of a blue or red radioactive beam.[41] Toho's special effects department has used various techniques to render the beam, from physical gas-powered flames[42] to hand-drawn or computer-generated fire. Godzilla is shown to possess immense physical strength and muscularity. Haruo Nakajima, the actor who played Godzilla in the original films, was a black belt in judo and used his expertise to choreograph the battle sequences.[43] Godzilla can breathe underwater[41] and is described in the original film by the character Dr. Yamane as a transitional form between a marine and a terrestrial reptile. Godzilla is shown to have great vitality: it is immune to conventional weaponry thanks to its rugged hide and ability to regenerate[44] and as a result of surviving a nuclear explosion, it cannot be destroyed by anything less powerful. Various films, television shows, comics and games have depicted Godzilla with additional powers, such as an atomic pulse,[45] magnetism,[46] precognition,[47] fireballs,[48] an electric bite,[49] superhuman speed,[50] eye beams[51] and even flight.[52]

Godzilla's allegiance and motivations have changed from film to film to suit the needs of the story. Although Godzilla does not like humans,[53] it will fight alongside humanity against common threats. However, it makes no special effort to protect human life or property[54] and will turn against its human allies on a whim. It is not motivated to attack by predatory instinct: it does not eat people[55] and instead sustains itself on nuclear radiation[56] and an omnivorous diet.[57] When inquired if Godzilla was "good or bad", producer Shogo Tomiyama likened it to a Shinto "God of Destruction" which lacks moral agency and cannot be held to human standards of good and evil. "He totally destroys everything and then there is a rebirth. Something new and fresh can begin."[55]

Godzilla battles King Kong in King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). This film has the highest Japanese box office attendance figures in the entire Godzilla series to date.[58] In the original Japanese films, Godzilla and all the other monsters are referred to with gender-neutral pronouns equivalent to "it",[59] while in the English dubbed versions, Godzilla is explicitly described as a male, such as in the title of Godzilla, King of the Monsters!. The creature in the 1998 Godzilla film was depicted laying eggs through parthenogenesis.[60][61][62]

Roar Godzilla has a distinctive disyllabic roar (transcribed in several comics as Skreeeonk!),[63][64] which was created by composer Akira Ifukube, who produced the sound by rubbing a pine-tar-resin-coated glove along the string of a contrabass and then slowing down the playback.[65] In the American version of Godzilla Raids Again (1955) entitled Gigantis the Fire Monster, Godzilla's iconic roar was substituted with that of the monster Anguirus.[31] From The Return of Godzilla (1984) to Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), Godzilla was given a deeper and more threatening-sounding roar than in previous films, though this change was reverted from Godzilla vs. Mothra (1992) onwards.[66] For the 2014 American film, sound editors Ethan Van der Ryn and Erik Aadahl refused to disclose the source of the sounds used for their Godzilla's roar.[65] Aadahl described the two syllables of the roar as representing two different emotional reactions, with the first expressing fury and the second conveying the character's soul.[67]

Size Godzilla's size is inconsistent, changing from film to film, and even from scene to scene, for the sake of artistic license.[55] The miniature sets and costumes were typically built at a 1⁄25–1⁄50 scale[68] and filmed at 240 frames per second to create the illusion of great size.[69] In the original 1954 film, Godzilla was scaled to be 50 m (164 ft) tall.[70] This was done so Godzilla could just peer over the largest buildings in Tokyo at the time.[2] In the 1956 American version, Godzilla is estimated to be 122 m (400 ft) tall, because producer Joseph E. Levine felt that 50 m did not sound "powerful enough".[71] As the series progressed Toho would rescale the character, eventually making Godzilla as tall as 100 m (328 ft).[72] This was done so that it would not be dwarfed by the newer, bigger buildings in Tokyo's skyline, such as the 243-meter-tall (797 ft) Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building which Godzilla destroyed in the film Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). Supplementary information, such as character profiles, would also depict Godzilla as weighing between 20,000 and 60,000 metric tons (22,000 and 66,000 short tons).[70][72] In the American film Godzilla (2014) from Legendary Pictures, Godzilla was scaled to be 108.2 m (355 ft) and weighing 90,000 metric tons (99,000 short tons), making it the largest film version at that time.[73] Director Gareth Edwards wanted Godzilla "to be so big as to be seen from anywhere in the city, but not too big that he couldn't be obscured".[74] For Shin Godzilla (2016), Godzilla was made even taller than the Legendary version, at 118.5 m (389 ft).[75][76] In Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters, Godzilla's height was increased further still to 300 m (984 ft).[77]

Special effects details

Suit fitting on the set of Godzilla Raids Again (1955), with Haruo Nakajima portraying Godzilla on the left Godzilla's appearance has traditionally been portrayed in the films by an actor wearing a latex costume, though the character has also been rendered in animatronic, stop-motion and computer-generated form.[78][79]

Taking inspiration from King Kong, special effects artist Eiji Tsuburaya had initially wanted Godzilla to be portrayed via stop-motion, but prohibitive deadlines and a lack of experienced animators in Japan at the time made suitmation more practical. The first suit consisted of a body cavity made of thin wires and bamboo wrapped in chicken wire for support and covered in fabric and cushions, which were then coated in latex. The first suit was held together by small hooks on the back, though subsequent Godzilla suits incorporated a zipper. Its weight was in excess of 100 kg (220 lb).[40] Prior to 1984, most Godzilla suits were made from scratch, thus resulting in slight design changes in each film appearance.[80] The most notable changes during the 1960s-70s were the reduction in Godzilla's number of toes and the removal of the character's external ears and prominent fangs, features which would later be reincorporated in the Godzilla designs from The Return of Godzilla (1984) onward.[81] The most consistent Godzilla design was maintained from Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) to Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995), when the suit was given a cat-like face and double rows of teeth.[82] Several suit actors had difficulties in performing as Godzilla, due to the suits' weight, lack of ventilation and diminished visibility.[40] Kenpachiro Satsuma in particular, who portrayed Godzilla from 1984 to 1995, described how the Godzilla suits he wore were even heavier and hotter than their predecessors because of the incorporation of animatronics.[83] Satsuma himself suffered numerous medical issues during his tenure, including oxygen deprivation, near-drowning, concussions, electric shocks and lacerations to the legs from the suits' steel wire reinforcements wearing through the rubber padding.[84] The ventilation problem was partially solved in the suit used in 1994's Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, which was the first to include an air duct, which allowed suit actors to last longer during performances.[85] In The Return of Godzilla (1984), some scenes made use of a 16-foot high robotic Godzilla (dubbed the "Cybot Godzilla") for use in close-up shots of the creature's head. The Cybot Godzilla consisted of a hydraulically-powered mechanical endoskeleton covered in urethane skin containing 3,000 computer operated parts which permitted it to tilt its head and move its lips and arms.[86]

In Godzilla (1998), special effects artist Patrick Tatopoulos was instructed to redesign Godzilla as an incredibly fast runner.[87] At one point, it was planned to use motion capture from a human to create the movements of the computer-generated Godzilla, but it was said to have ended up looking too much like a man in a suit.[88] Tatopoulos subsequently reimagined the creature as a lean, digitigrade bipedal iguana-like creature that stood with its back and tail parallel to the ground, rendered via CGI.[89] Several scenes had the monster portrayed by stuntmen in suits. The suits were similar to those used in the Toho films, with the actors' heads being located in the monster's neck region, and the facial movements controlled via animatronics. However, because of the creature's horizontal posture, the stuntmen had to wear metal leg extenders, which allowed them to stand two meters (six feet) off the ground with their feet bent forward. The film's special effects crew also built a 1⁄6 scale animatronic Godzilla for close-up scenes, whose size outmatched that of Stan Winston's T. rex in Jurassic Park.[90] Kurt Carley performed the suitmation sequences for the adult Godzilla.[12]

In Godzilla (2014), the character was portrayed entirely via CGI. Godzilla's design in the reboot was intended to stay true to that of the original series, though the film's special effects team strove to make the monster "more dynamic than a guy in a big rubber suit."[91] To create a CG version of Godzilla, the Moving Picture Company (MPC) studied various animals such as bears, Komodo dragons, lizards, lions and gray wolves which helped the visual effects artists visualize Godzilla's body structure like that of its underlying bone, fat and muscle structure as well as the thickness and texture of its scale.[92] Motion capture was also used for some of Godzilla's movements. T.J. Storm provided the performance capture for Godzilla by wearing sensors in front of a green screen.[14]

In Shin Godzilla, a majority of the character was portrayed via CGI, with Mansai Nomura portraying Godzilla through motion capture.[11]

Appearances Main article: Godzilla (franchise) Further information: Godzilla (comics) Cultural impact Main article: Godzilla in popular culture

Godzilla's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame Godzilla is one of the most recognizable symbols of Japanese popular culture worldwide[93][94] and remains an important facet of Japanese films, embodying the kaiju subset of the tokusatsu genre. Godzilla's vaguely humanoid appearance and strained, lumbering movements endeared it to Japanese audiences, who could relate to Godzilla as a sympathetic character, despite its wrathful nature.[95] Audiences respond positively to the character because it acts out of rage and self-preservation and shows where science and technology can go wrong.[96]

In 1967, the Keukdong Entertainment Company of South Korea, with production assistance from Toei Company, produced Yongary, Monster from the Deep, a reptilian monster who invades South Korea to consume oil. The film and character has often been branded as a knock-off of Godzilla.[97][98]

Godzilla has been considered a filmographic metaphor for the United States, as well as an allegory of nuclear weapons in general. The earlier Godzilla films, especially the original, portrayed Godzilla as a frightening nuclear-spawned monster. Godzilla represented the fears that many Japanese held about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the possibility of recurrence.[99] As the series progressed, so did Godzilla, changing into a less destructive and more heroic character as the films became geared more towards children. Since then, the character has fallen somewhere in the middle, sometimes portrayed as a protector of the world from external threats and other times as a bringer of destruction.[100][101]

In 1996, Godzilla received the MTV Lifetime Achievement Award,[102] as well as being given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2004 to celebrate the premiere of the character's 50th anniversary film, Godzilla: Final Wars.[103] Godzilla's pop-cultural impact has led to the creation of numerous parodies and tributes, as seen in media such as Bambi Meets Godzilla, which was ranked as one of the "50 greatest cartoons",[104] two episodes of Mystery Science Theater 3000[105] and the song "Godzilla" by Blue Öyster Cult.[106] Godzilla has also been used in advertisements, such as in a commercial for Nike, where Godzilla lost an oversized one-on-one game of basketball to a giant version of NBA player Charles Barkley.[107] The commercial was subsequently adapted into a comic book illustrated by Jeff Butler.[108] Godzilla has also appeared in a commercial for Snickers candy bars, which served as an indirect promo for the 2014 movie. Godzilla's success inspired the creation of numerous other monster characters, such as Gamera,[109][110] Reptilicus of Denmark,[111] Yonggary of South Korea,[97] Pulgasari of North Korea,[112] Gorgo of the United Kingdom[113] and the Cloverfield monster of the United States.[114]

Godzilla's fame and saurian appearance has influenced the scientific community. Gojirasaurus is a dubious genus of coelophysid dinosaur, named by paleontologist and admitted Godzilla fan Kenneth Carpenter.[115] Dakosaurus is an extinct marine crocodile of the Jurassic Period, which researchers informally nicknamed "Godzilla".[116] Paleontologists have written tongue-in-cheek speculative articles about Godzilla's biology, with Ken Carpenter tentatively classifying it as a ceratosaur based on its skull shape, four-fingered hands and dorsal scutes, and paleontologist Darren Naish expressing skepticism while commenting on Godzilla's unusual morphology.[117]

Godzilla's ubiquity in pop-culture has led to the mistaken assumption that the character is in the public domain, resulting in litigation by Toho to protect their corporate asset from becoming a generic trademark. In April 2008, Subway depicted a giant monster in a commercial for their Five Dollar Footlong sandwich promotion. Toho filed a lawsuit against Subway for using the character without permission, demanding $150,000 in compensation.[118] In February 2011, Toho sued Honda for depicting a fire-breathing monster in a commercial for the Honda Odyssey. The monster was never mentioned by name, being seen briefly on a video screen inside the minivan.[119] The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society christened a vessel the MV Gojira. Its purpose is to target and harass Japanese whalers in defense of whales in the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. The MV Gojira was renamed the MV Brigitte Bardot in May 2011, due to legal pressure from Toho.[120] Gojira is the name of a French death metal band, formerly known as Godzilla; legal problems forced the band to change their name.[121] In May 2015, Toho launched a lawsuit against Voltage Pictures over a planned picture starring Anne Hathaway. Promotional material released at the Cannes Film Festival used images of Godzilla.[122]

Steven Spielberg cited Godzilla as an inspiration for Jurassic Park (1993), specifically Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), which he grew up watching.[123] Spielberg described Godzilla as "the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies because it made you believe it was really happening."[124] Godzilla also influenced the Spielberg film Jaws (1995).[125][126]

The main-belt asteroid 101781 Gojira, discovered by American astronomer Roy Tucker at the Goodricke-Pigott Observatory in 1999, was named in honor of the creature.[127] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 11 July 2018 (M.P.C. 110635).[128]

Cultural ambassador To encourage tourism in April 2015 the central Shinjuku ward of Tokyo named Godzilla an official cultural ambassador. During an unveiling of a giant Godzilla bust at Toho headquarters, Shinjuku mayor Kenichi Yoshizumi stated "Godzilla is a character that is the pride of Japan." The mayor extended a residency certificate to an actor in a rubber suit representing Godzilla, but as the suit's hands were not designed for grasping, it was accepted on Godzilla's behalf by a Toho executive. Reporters noted that Shinjuku ward has been flattened by Godzilla in three Toho movies.[129][130]

References Ryfle 1998, p. 178. Ryfle 1998, p. 27. Ryfle 1998, p. 142. Ryfle 1998, p. 360. Ryfle 1998, p. 361. Perlmutter 2018, p. 248. Morgan, Clay (March 23, 2015). "Ted Cassidy: The Man Behind Lurch, Gorn & TV's Incredible Hulk". Norvillerogers.com. Retrieved July 18, 2018. Ryfle 1998, p. 263. Kalat 2010, p. 232. Kalat 2010, p. 241. Ashcraft, Brian (August 1, 2016). "Meet Godzilla Resurgence's Motion Capture Actor". Kotaku. Retrieved August 1, 2016. Mirjahangir, Chris (November 7, 2014). "Nakajima and Carley: Godzilla's 1954 and 1998". Toho Kingdom. Retrieved April 5, 2015. Miller, Bob (April 1, 2000). "Frank Welker: Master of Many Voices". Animation World Network. Retrieved March 24, 2018. Arce, Sergio (May 29, 2014). "Conozca al actor que da vida a Godzilla, quien habló con crhoy.com". crhoy.com. Retrieved March 26, 2015. Pockross, Adam (February 28, 2019). "Genre MVP: The Motion Capture Actor Who's Played Groot, Godzilla, and Iron Man". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019. "Making of the Godzilla Suit". Gojira - Classic Media 2006 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Retrieved April 6, 2018. Kalat 2010, p. 29. Solomon 2017, p. 32. Honda 1970, 21:57. Godzila, Mothra, and King Ghidorah (2001). Directed by Shusuke Kaneko. Toho DeSentis, John (July 4, 2010). "Godzilla Soundtrack Perfect Collection Box 6". SciFi Japan. Retrieved November 23, 2014. Brothers 2009. Barr 2016, p. 83. Robbie Collin (May 13, 2014). "Gareth Edwards interview: 'I wanted Godzilla to reflect the questions raised by Fukushima'". The Telegraph. Retrieved May 19, 2016. Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #1 (Marvel Comics, 1977) Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #20 (Marvel Comics, 1979) Godzilla, King of the Monsters (vol. 1) #23 (Marvel Comics, 1979) Ryfle 1998, p. 22. "Gojira Media". Godzila Gojimm. Toho Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2010. Ryfle 1998, p. 23. Ryfle 1998, p. 74. Peter Bradshaw (October 14, 2005). "Godzilla | Culture". London: The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Biondi, R, "The Evolution of Godzilla – G-Suit Variations Throughout the Monster King's Twenty-One Films", G-Fan #16, July/August 1995 Greenberger, R. (2005). Meet Godzilla. Rosen Pub Group. p. 15. ISBN 1404202692 Kishikawa, O. (1994), Godzilla First, 1954 ~ 1955, Big Japanese Painting, ASIN B0014M3KJ6 Kravets, David (November 24, 2008). "Think Godzilla's Scary? Meet His Lawyers". Wired. Retrieved May 21, 2013. Snider, Mike (August 29, 2006). "Godzilla arouses atomic terror". USA Today. Retrieved May 30, 2013. Tsutsui 2003, p. 23. "Gojira". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved June 2, 2013. Making of the Godzilla Suit!. Ed Godziszewski. YouTube (December 24, 2010) An Anatomical Guide to Monsters, Shoji Otomo, 1967 "Interview with Haruo Nakajima". Godzilla - Criterion Collection 2012 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Missing or empty |url= (help); |access-date= requires |url= (help) The Art of Suit Acting - Classic Media Godzilla Raids Again DVD featurette Godzilla 2000 (1999). Directed by Takao Okawara. Toho. Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). Directed by Kazuki Ōmori. Toho Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). Directed by Jun Fukuda. Toho Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989). Directed by Kazuki Ōmori. Toho Godzilla: Destroy All Monsters Melee (2002). Pipeworks Software CR Godzilla Pachinko (2006). Newgin Zone Fighter (1973). Directed by Ishirō Honda et al. Toho The Godzilla Power Hour (1978). Directed by Ray Patterson and Carl Urbano. Hanna-Barbera Productions Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971). Directed by Yoshimitsu Banno. Toho Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964). Directed by Ishirō Honda. Toho. Godzilla: Unleashed - Godzilla 2000 character profile "Ryuhei Ktamura & Shogo Tomiyama interview - Godzilla Final Wars premiere - PennyBlood.com". Web.archive.org. February 3, 2005. Archived from the original on February 3, 2005. Retrieved September 25, 2013. The Return of Godzilla (1985). Directed by Koji Hashimoto. Toho Milliron, K. & Eggleton, B. (1998), Godzilla Likes to Roar!, Random House Books for Young Readers, ISBN 0679891250 Peter H. Brothers. Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. Author House. 2009. Pgs. 47-48 Tsutsui 2003, p. 12. Ryfle 1998, p. 336. Kalat 2010, p. 225. Seibold, Witney (May 26, 2014). "Godzilla Goodness: Godzilla (1998)". Nerdist. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Stradley, R., Adams, A., et al. Godzilla: Age of Monsters (February 18, 1998), Dark Horse Comics; Gph edition. ISBN 1569712778 Various. Godzilla: Past Present Future (March 5, 1998), Dark Horse Comics; Gph edition. ISBN 1569712786 NPR Staff. "What's In A Roar? Crafting Godzilla's Iconic Sound". National Public Radio. Retrieved September 7, 2015. David Milner, "Takao Okawara Interview I", Kaiju Conversations (December 1993) Ray, Amber (May 22, 2014). "'Godzilla': The secrets behind the roar". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 19, 2016. "Godzilla". Gvsdestoroyah.dulcemichaelanya.com. Retrieved September 25, 2013. "Amazing and Interesting Facts about Godzilla Special Effects - Special Effects in Godzilla Movies - Hi-tech - Kids". Web Japan. Retrieved September 25, 2013. "Godzilla (1954) stats and bio page". www.tohokingdom.com. Retrieved March 8, 2013. Tsutsui 2003, p. 54-55. "Godzilla (1991) stats and bio page". www.tohokingdom.com. Retrieved June 3, 2015. "Godzilla Ultimate Trivia". The Movie Bit. Retrieved May 21, 2014. Owusu, Kwame (February 28, 2014). "The New Godzilla is 350 Feet Tall! Biggest Godzilla Ever!". MovieTribute. Retrieved February 20, 2018. "2016年新作『ゴジラ』 脚本・総監督:庵野秀明氏&監督:樋口真嗣��からメッセージ". oricon.co.jp. Retrieved April 1, 2015. Ragone, August (December 9, 2015). "Japanese Press Reveals Shin Godzilla's Size". The Good, the Bad, and Godzilla. Retrieved February 20, 2018. Miska, Brad. "The Latest Godzilla is Three Times the Size of its Predecessors!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved April 20, 2019. Failes, Ian (October 14, 2016). "The History of Godzilla Is the History of Special Effects". Inverse. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Ryūsuke, Hikawa (June 26, 2014). "Godzilla's Analog Mayhem and the Japanese Special Effects Tradition". Nippon.com. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Kalat 2010, p. 36. Kalat 2010, p. 160. Ryfle 1998, p. 254-257. Clements, J. (2010), Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade, A-Net Digital LLC, pp. 117-118, ISBN 0984593748 Kalat 2010, p. 258. Ryfle 1998, p. 298. Ryfle 1998, p. 232. Rickitt, Richard (2006). Designing Movie Creatures and Characters: Behind the Scenes With the Movie Masters. Focal Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 0-240-80846-0. Rickitt, Richard (2000). Special Effects: The History and Technique. Billboard Books. p. 174. ISBN 0-8230-7733-0. "Godzilla Lives! - page 1". Theasc.com. Retrieved January 22, 2014. Ryfle 1998, p. 337-339. Dudek, Duane (November 8, 2013). "Oscar winner & Kenosha native Jim Rygiel gets UWM award". Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013. Carolyn Giardina (December 25, 2014). "Oscars: 'Interstellar,' 'Hobbit' Visual Effects Artists Reveal How They Did It". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 28, 2014. Sharp, Jasper (2011). Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780810857957. West, Mark (2008). The Japanification of Children's Popular Culture: From Godzilla to Miyazaki. Scarecrow Press. p. vii. ISBN 9780810851214. "Interview with Tadao Sato". Godzilla - Criterion Collection 2012 Blu-ray/DVD Release. Missing or empty |url= (help); |access-date= requires |url= (help) "The Psychological Appeal of Movie Monsters" (PDF). Calstatela.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2013. Kalat 2010, p. 92. Demoss, David (June 18, 2010). "Yongary, Monster from the Deep". And You Thought It Was...Safe(?). Retrieved March 19, 2018. Rafferty, T., The Monster That Morphed Into a Metaphor, NYTimes (May 2, 2004) Lankes, Kevin (June 22, 2014). "Godzilla's Secret History". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Goldstein, Rich (May 18, 2014). "A Comprehensive History of Toho's Original Kaiju (and Atomic Allegory) Godzilla". Daily Beast. Retrieved March 19, 2018. "Godzilla Wins The MTV Lifetime Achievement Award In 1996 – Godzilla video". Fanpop. November 3, 1954. Retrieved April 13, 2010. "USATODAY.com - Godzilla gets Hollywood Walk of Fame star". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. November 30, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Beck, Jerry (ed.) (1994). The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals. Atlanta: Turner Publishing. ISBN 1-878685-49-X. "Godzilla Genealogy Bop" - MST3K season 2, episode 13, aired February 2, 1991 Song Review by Donald A. Guarisco. "Godzilla - Blue Öyster Cult | Listen, Appearances, Song Review". AllMusic. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Martha T. Moore. "Godzilla Meets Barkley on MTV". USA Today. September 9, 1992. 1.B. Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury. Holy Sh*t! The World's Weirdest Comic Books. St. Martin's Press, 2008. 104. Kalat 2010, p. 23. Phipps, Keith (June 2, 2010). "Gamera: The Giant Monster". AV Club. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Don (June 16, 2015). "Reptilicus: Godzilla Goes To Denmark". Schlockmania. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Romano, Nick (April 6, 2015). "How Kim Jong Il Kidnapped a Director, Made a Godzilla Knockoff, and Created a Cult Hit". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Murray, Noel (May 8, 2014). "Meet Gorgo, the "British Godzilla"". The Dissolve. Retrieved March 19, 2018. Monetti, Sandro (January 13, 2008). "Cloverfield: Making of a monster". Express. Retrieved March 19, 2018. K. Carpenter, 1997, "A giant coelophysoid (Ceratosauria) theropod from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 205 (#2): 189-208 Gasparini Z, Pol D, Spalletti LA. 2006. An unusual marine crocodyliform from the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary of Patagonia. Science 311: 70-73. Naish, Darren (November 1, 2010). "The science of Godzilla, 2010 – Tetrapod Zoology". Scienceblogs.com. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Toho sues Subway over unauthorized Godzilla ads, The Japan Times (April 18, 2008) Toho suing Honda over Godzilla, TokyoHive (February 12, 2011) "Sea Shepherd Conservation Society :: The Beast Transforms into a Beauty as Godzilla Becomes the Brigitte Bardot". Seashepherd.org. May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2013. Gojira htm Biography and Band at the Gauntlet, The Gauntlet "Voltage Pictures Sued For Copyright Infringement". torrentfreak.com. Retrieved July 9, 2015. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G". ECW Press. p. 15. ISBN 9781550223484. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G". ECW Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781550223484. Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780753505564. Derry, Charles (1977). Dark Dreams: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film. A. S. Barnes. p. 82. ISBN 9780498019159. "(101781) Gojira". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved July 19, 2018. "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved July 19, 2018. "Godzilla recruited as tourism ambassador for Tokyo". The Guardian. April 9, 2015. "Godzilla is Tokyo's newest resident and ambassador". New York Post. April 9, 2015. Sources Barr, Jason (2016). The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema's Biggest Monsters. McFarland. ISBN 1476623953. Brothers, Peter H. (2009). Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. CreateSpace Books. ISBN 1492790354. Edwards, Gareth (2014). Godzilla. Warner Bros. Pictures. Galbraith IV, Stuart (1998). Monsters Are Attacking Tokyo! The Incredible World of Japanese Fantasy Films. Feral House. ISBN 0922915474. Godziszewski, Ed (1994). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Godzilla. Daikaiju Enterprises. Honda, Ishiro (1970). Monster Zero (English version). Toho Co., Ltd/United Productions of America. Kalat, David (2010). A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series (second edition). McFarland. ISBN 9780786447497. Lees, J.D.; Cerasini, Marc (1998). The Official Godzilla Compendium. Random House. ISBN 0-679-88822-5. Perlmutter, David (2018). The Encyclopedia of American Animated Television Shows. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 1538103737. Ragone, August (2007). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9. Rhoads & McCorkle, Sean & Brooke (2018). Japan's Green Monsters: Environmental Commentary in Kaiju Cinema. McFarland. ISBN 9781476663906. Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan’s Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488. Ryfle, Steve; Godziszewski, Ed (2017). Ishiro Honda: A Life in Film, from Godzilla to Kurosawa. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-7087-1. Solomon, Brian (2017). Godzilla FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King of the Monsters. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 9781495045684. Tsutsui, William M. (2003). Godzilla On My Mind: Fifty Years of the King of Monsters. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403964742. External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Godzilla. Wikiquote has quotations related to: Godzilla (franchise) Official website of Toho (Japanese) Godzilla on IMDb

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) – Episode 134 – Decades of Horror 1970s

"When the red moon sets and the sun rises in the West, two monsters will appear to save the people.” But first, you have to listen to the song. Join your faithful Grue Crew - Doc Rotten, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, and Jeff Mohr - and as they try to keep the aliens, monsters, and good guys straight, while learning a few wrestling moves on the side, in the kaiju romp from Toho known as Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974).

Decades of Horror 1970s Episode 134 – Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

Ape-like aliens build a robotic Godzilla to destroy Japan, and the true Godzilla may not be powerful enough to destroy it.

IMDb

Director: Jun Fukuda

Writers: Jun Fukuda, Hiroyasu Yamaura (as Hiroyasu Yamamura)

Story by: Masami Fukushima, Shin'ichi Sekizawa

Selected Cast:

Masaaki Daimon as Keisuke Shimizu

Kazuya Aoyama as Masahiko Shimizu

Akihiko Hirata as Professor Hideto Miyajima

Hiroshi Koizumi as Professor Wagura

Reiko Tajima as Saeko Kanagusuku

Hiromi Matsushita as Ikuko Miyajima

Goro Mutsumi as Kuronuma, Black Hole Alien Leader

Shin Kishida as Nanbara, Interpol Agent

Takayasu Torii as Tamura, Interpol Agent

Bellbella Lin as Nami Kunigami, the Azumi Royal Family Princess (as Barbara Lynn)

Masao Imafuku as Tengan Kunigami, the Azumi Royal Family High Priest

Daigo Kusano as Yanagawa, Alien Agent #1

Kenji Sahara as Ship Captain

Isao Zushi as Godzilla

Ise Mori as Mechagodzilla

Kinichi Kusumi as Anguirus / King Shîsâ (as Momoru Kusumi)

It’s Chad’s pick this episode and he first learned of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla from a trailer he saw while watching Sanford and Son and he immediately knew he had to see it, even if he had to walk uphill both ways the three miles to the theater. He is a big fan of The Six Million Dollar Man and thought Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla was the best thing he��d ever seen. Even now, he had a blast watching the movie despite its cheese factor. Bill, a huge kaiju fan, has always liked Mechagodzilla and its Swiss Army knife arsenal of weaponry. As always, Jeff is playing catch up with the rest of the 70s Grue-Crew when it comes to kaiju, but he loved the explosions! They “blowed” up stuff real good! Doc is also a lover of kaiju and monster films and was gaga over the four monsters in this one - the title characters, Anguirus, and King Shisa - and the wrestling moves the monsters utilize.

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla gets a big thumbs up from the 70s Grue-Crew! (Don’t they all?) The film is currently available for streaming on HBOmax and The Criterion Channel, and on Blu-ray disc in the Godzilla: The Showa-Era Films, 1954–1975 Box Set from Criterion.

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1970s is part of the Decades of Horror two-week rotation with The Classic Era and the 1980s. In two weeks, the next episode in their very flexible schedule will be Damien: Omen II (1978), chosen by Doc! Be sure to join us for that one.

We want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave us a message or leave a comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror 1970s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

“Gojira tai Mekagojira“ or Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974)

AKA: Godzilla vs. Bionic / Cosmic Monster, choose one, as both names were used in addition to “Mechagodzilla,” and in Spain they called the bad guy “Cibergodzilla.” Italy just called him a “robot.”

It’s important to note from the start that this is set on Okinawa, which is a quite remote island of Japan and is separate from Tokyo and other cities of Nippon. I’m not sure how to view this from a North American perspective, but maybe substitute Puerto Rico or Hawai’i vs America; or Newfoundland vs Canada; or the Isles of Scilly vs the UK; or Tasmania vs Australia. Technically it’s part of Japan, but it’s very remote and the feeling one gets is that “Things Are Very Different There…”

New cover illustration by Takashi Okazaki — — — —

We start the film with a title song in the style of big band jazz that sounds like “Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing)” by the Benny Goodman Orchestra. It’s a great, bounding tune, and it re-emerges in the battle / fight sequence later to great effect.

The story’s danger is Foreign and Technological in nature. The enemy is cold, calculating, and will stop at nothing to get what they want, yet they are defeated by old-fashioned determination wielded in traditional means. There’s an allegorical reason for this:

The film was widely criticized for its supposed lack of substance. However, some critics pointed out the actual historical context behind the plot. There had long been tension between Japan and the island Okinawa, [plus] Okinawa was the home of American military bases at the time that brought the threat of the Cold War to the island. With the aliens controlling Mechagodzilla representing the outside invading force [potentially either the Americans and/or the Soviets, to be honest], Godzilla representing Japan, and the mythical King Caesar standing in for Okinawa, the film proposes cooperation between the two nations, standing together against a common adversary.

- IMDb [link]

This approach to problem solving of co-operation and using methods so basic that high-tech doesn’t even think about them anymore is something we’ll see again in the Battle of Endor in The Return of the Jedi, among other films.

King Shîsâ (Kinichi Kusumi) in “Gojira tai Mekagojira“ (1974) — — — —

The guardian monster King Shîsâ is based on the actual “shîsâ” lion-dog guardian statues in Okinawa. Originally from China, they are statues that ward off evil spirits. Another Japanese name for them is “komainu” (lion-dog).

However as seen in the film, King Shîsâ (or ‘King Caesar’ as the English sub-titles simplify it and it really sounds like that anyway) looks like a dragon fucked the dog-like beast from The Neverending Story. I apologize for that comparison, but take a look at that thing and see if you can come up with something better!

The details of the story beyond the above ones are multiple, as is typical in these things.

The plot’s protagonist is very much the young anthropologist: who is A WOMAN!! After the last film, let’s celebrate the fact she’s here. Additionally, there’s a daughter of Professor Hideto Miyajima (played by Akihiko Hirata), but she ends up basically being there to be rescued and whose potential death is used as a bargaining chip to gain the Professor’s co-operation. Alas.

We also have earthquakes in the second film in a row. This leads to a big rocks flying out of a volcano, it then explodes on impact, and OUT COMES GODZILLA!! This, plus a black cloud, and a few other things, match a prophesy received by a member of the Royal House of Azumi regarding vengeance upon the mainlanders’ desecration of the local shrines.

INTERPOL makes its first appearance here, and it will continue to exert its power in the next film (completely ignoring the fact that it’s an information sharing agreement and its network doesn’t include investigating agents in any way). We also meet a self-described ‘muckraker’ reporter who may not be what he seems!

Nami Kunigami, the Azumi Royal Family Princess (Bellbella Lin) [kneeling, right] solicits the help of King Shîsâ (Kinichi Kusumi) [rear, in cave, above and to the left of the bad matte work] in “Gojira tai Mekagojira“ (1974) — — —

Because it’s been awhile since we had a musical number, Azumi Princess Nami Kunigami (Bellbella Lin) wakes King Shîsâ by taking to the beach before his cave and singing a pretty song, in which she begs him to help save the people he has protected for so many years.

A shot of Godzilla peeking over the top of a hill harkens back to his debut in 1954, two decades previous. This film was made to mark the 20th anniversary of Godzilla’s debut, which also accounts for the number of repeat actors, and probably the increased budget for sets and costumes. For instance, Akihiko Hirata is back (not wearing an eye-patch this time), here he’s an analyst of Space Titanium. Also, the SFX include a rainbow zapping fight between King Shîsâ and Mechagodzilla. We get great pictures and art direction throughout; especially the sets and costumes!

Improvements also include (but are not limited to) the fact that Godzilla now has lightning power and is magnetic! I’m not sure how practical any of that is in the long run, but; hey! variety! [:: confetti cannon ::]

Cinematography and lighting are much better; although there are occasional shots which make me wonder if there was some drinking honing on. Mostly the problem seems to be problem with a specific lens: it has a massive area of aberration that covers ¾ of the field, and it may be impossible to focus on anything except a set distance from the camera. Somebody definitely needed to repair that thing.

That said, there’s some great use of low angles, snap zooms, whip pans, and a bunch of other techniques to make things look grand, as well as some excellent use of lighting to both evoke moods and show things off to their best potential.

Mechagodzlla (Ise Mori) [left] is attacked by Godzilla (Isao Zushi) [right] at an oil refinery in “Gojira tai Mekagojira“ (1974) — — — —

At the beginning of the story, Anguirus (Kinichi Kusumi) moves wrong: it’s obviously a guy in a suit on all fours and when attacking he wants to stand upright whenever possible, but that’s simply out of character. The fault here may be that the previous times we saw Anguirus, he was a different proportion to who he was attacking. Also his tail is too long; seen when he is retreating, it may be twice as long as he is!

People drive like four-year-olds, making the car go faster by wiggling the steering wheel back and forth. That’s a shame.

All in all, a return to the bonkers approach to story telling where history and imagination are woven together in a successfully entertaining manner.

★★★★☆

#Godzilla#Mechagodzilla#Anguirus#King Shîsâ#King Caesar#Gojira tai Mekagojira#Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla#Criterion Collection#Dear God What Have I Done to Myself?

0 notes

Text

1ª EDIÇÃO MENU SOLIDÁRIO

http://www.piscitellientretenimentos.com/1a-edicao-menu-solidario/

1ª EDIÇÃO MENU SOLIDÁRIO

Azumi ensina clássicos do restaurante em workshop com renda revertida para o instituto Vivendas da Fé

Que tal participar de um workshop sob o comando de dois mestres na arte de produzir o que há de mais representativo na gastronomia oriental e, ao mesmo tempo, ajudar uma instituição que há 19 anos oferece a esperança de uma vida melhor a crianças e adolescentes em situação de risco ou abandono?

Essa é a proposta da 1ª edição do Menu Solidário, que acontecerá no dia 30 de setembro, às 15:30h, no Azumi. O restaurante que é referência no respeito às tradições culturais do Japão, em Copacabana, mas ao mesmo tempo sensível às tendências inovadoras e a tudo o que represente o melhor do espírito humano, abraçou a causa do instituto e, sob o comando de Isao e Alissa Ohara, verdadeiros ícones da culinária japonesa, promoverá um delicioso workshop gastronômico, aberto ao público. Os participantes vão aprender a preparação do famoso Harumaki (Foto), de origem chinesa, elaborado com repolho, cenoura e cogumelos.

O prato é extremamente apreciado pelo público, mas nunca fora servido no restaurante. Ele estará presente no workshop como uma singela homenagem aos filhos de Alissa, que sempre o pedem. Também serão elaborados o Do Goma Ae de agrião, que será escaldado e temperado no molho de gergelim, levemente adocicado, e o Okonomi Zushi, que quer dizer sushi a seu gosto. Nada mais é do que uma forma divertida e informal de comer sushi, com cada pessoa montando o seu com o recheio de preferência. Tudo isso com direito à degustação das iguarias após a aula. O evento terá o valor de R$ 200 por pessoa e toda a renda será revertida para o instituto Vivendas da Fé – Lar da Criança “Minha casa, doce casa”, em Guaratiba.

A 1ª edição do Menu Solidário é uma iniciativa que abraça o projeto O Ideal é Real, de autoria do juiz Sérgio Luiz Ribeiro de Souza da 4ª Vara da Infância, da Juventude e do Idoso do Rio. O foco do projeto é aproximar pessoas habilitadas à adoção de crianças e adolescentes que preencham os requisitos para “adoções necessárias”. Essas adoções são compostas por crianças com mais de 3 anos de idade e adolescentes; grupos de irmãos; e crianças e adolescentes com problemas de saúde. Porém, as pessoas ao iniciarem o processo de habilitação para adoção traçam um perfil, de forma a idealizar o “filho”, mas nas instituições de acolhimento estão as crianças e os adolescentes reais à espera do gesto de amor, e que preenchem os requisitos para “adoções necessárias”. O projeto sinaliza uma forma mais abrangente de doação, de troca de afeto. Aproximar o ideal do real. Esse é o desdobramento do projeto Apadrinhar – Amar e Agir para Materializar Sonhos, também de autoria do juiz, vencedor do Prêmio Innovare, em 2015.

O Apadrinhar é um programa que visa a recuperação da autoestima de crianças e adolescentes e que estabelece três tipos de apadrinhamento: o afetivo, com visitas regulares ao acolhido, buscando-o para passar fins de semana, feriados ou férias escolares em sua companhia, proporcionando o fortalecimento de valores e laços de fraternidade; o provedor, que apoia financeiramente o acolhido; e o colaborador, que presta serviços às instituições dentro de sua área de conhecimento ou profissão. A experiência, implementada em outros estados, tem apresentado retorno muito positivo. E no Vivendas da Fé – Lar da Criança “Minha casa, doce casa”, não é diferente.

A história da instituição começa com o desejo de Ana Maria Rocha Rezende Martins, de ser mãe de coração. O sonho foi concretizado em 1998, com a adoção do primeiro dos mais de 928 abrigados que, desde então, encontraram afeto, proteção e a oportunidade essencial para seu desenvolvimento.

Assim, a 1ª Edição do Menu Solidário, que vai contar com a presença do juiz Sérgio Luiz Ribeiro palestrando sobre as modalidades dos dois projetos, torna-se uma oportunidade imperdível de degustar clássicos deliciosos da culinária japonesa e ao mesmo tempo exercer o compromisso da solidariedade.

Serviço:

Dia do evento :: 30.09.2017

Horário: 15:30hs até 18:30h

Inscrição através do telefone (21) 99985-8587 (whatsapp)

Local do evento: Rua Ministro Viveiros de Castro, nº 127 _ Copacabana

Valor da inscrição R$ 200,00

Capacidade: 20 lugares

0 notes

Photo

Japanuary Day 24 (2/2) - Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974)

youtube

#Japanuary#Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla#Jun Fukuda#Isao Zushi#Kinichi Kusumi#Ise Mori#Masaaki Daimon#Matthew Oram#Akihiko Hirata#Michael Kaye#English Dub#Masao Imafuku#Beru-Bera Lin#Goro Mutsumi#Daigo Kusano#Kaiju#Godzilla#Mechagodzilla#Anguirus#King Caesar#Gojira tai mekagojira#Godzilla vs. Bionic Monster#Godzilla vs. Cosmic Monster#Shin Kishida

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#20 Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla - Jun Fukuda 1974

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla - Jun Fukuda 1974

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla - Jun Fukuda 1974

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla - Jun Fukuda 1974

18 notes

·

View notes