#IMF Economist jobs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Apply Now:International Monetary Fund Economist Program for Young Graduates - 2023

Apply Now:International Monetary Fund Economist Program for Young Graduates – 2023

Are you a young economist interested in acquiring hands-on exposure to a cross-section of InteInternationalrnational Monetary Fund (IMF) work and an opportunity to apply your research and analytical skills? Then the International Monetary Fund Economist Program is for you. The Economist Program offers participants a well-rounded experience of the IMF’s work and provides a unique foundation for a…

View On WordPress

#Apply Now:International Monetary Fund Economist Program for Young Graduates - 2023#How to get a job at IMF#IMF Economist jobs#IMF economist LinkedIn#IMF economist Program 2022#IMF Economist Program 2023#IMF Economist Program salary#IMF economists#IMF EP#IMF experienced economist#IMF jobs#IMF program Pakistan IMF program grant#IMF programs#IMF young professionals Program#World Bank economist Program

0 notes

Text

As all journalists know fear sells better than sex. Readers want be terrified. And here in the UK, there appears to be every reason to frighten them.

A country that was overdependent on financial services has been in decline ever since the banking crash of 2008. Then, from 2010 on, the astonishing Conservative policy failures of austerity, Trussonomics and, above all, Brexit further weakened an enfeebled state.

I was a child in a happy family during the crisis of the 1970s. Like all happy children I just got on with my life. But even I picked up a little of the despair and hopelessness of the time. That feeling that there is no way out is with us again.

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher came to power, and with great brutality, set the UK on a new path as she inflicted landslide defeats on Labour.

Obviously, our current Conservative government is heading for a defeat, maybe a landslide defeat.

But there is little sense that Labour will transform the country. The far-left takeover from 2015-2019 traumatised it. As recently as 2021, everyone expected Boris Johnson to rule the UK for most of the 2020s.

Johnson’s contempt for the rules he insisted everyone else follow and the great Truss disaster are handing Labour victory. But the centre-left appears to be the beneficiary of scandal and right-wing madness, not an ideological sea change that might inspire it and sustain it in power

Desperate to drop its crank image, battered by the conservative media establishment, fashionable opinion holds that a wee, cowering and timorous Labour party will come into power without radical policies that equal the country’s needs.

Just this once, fashionable opinion may even be right

And yet, and I know I will regret this outbreak of commercially suicidal optimism, there are reasons to believe that the UK’s position is not quite as grim as it appears.

1) The economy may revive

Although no one has been as wrong recently as the economists and central bankers who predicted that inflation would be a transitory phenomenon, it is finally coming down. Falls in energy prices may even bring it to the 2 per cent target this month. Interest rates will eventually follow suit.

Lower interest rates mean lower government borrowing costs. They will reduce the extraordinary debt bill Labour in power will have to meet.

Chris Giles of the Financial Times calculated this week that lower government borrowing costs improve the public finances five years ahead by almost £15bn (about 0.5 per cent of national income) for every percentage point reduction.

Meanwhile the Conservatives have raised taxes so high (by UK standards) a Labour government may not need to risk unpopularity by raising them further. Under Conservative plans the tax burden has risen from 33.1 per cent of gross domestic product in 2019-20 to 36.5 per cent in 2024-25 with further rises planned, taking it to 37.1 per cent by 2028-29.

If the 1997-2010 Labour government is any guide, Labour will be reluctant in the extreme to play into its enemies’ hands by raising taxes

It may not need to if economic growth leads to the revenue growth that would take the UK out of the rolling crisis that has afflicted it since 2016.

I wouldn’t be doing my job if I did not add that there are some pretty large caveats to make.

Economists missed the post-covid inflation surge because they forgot about politics. Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine upended the European economy. An extension of the war in Ukraine or the Middle East, or, more terrifyingly, a US-China confrontation, or the return of Donald Trump could all derail a new government.

In any case the IMF predicts growth of 1.5 percent in 2025, which is nowhere near the 3 percent we need to fund the state.

And yet, with a bit of luck there is a fair chance that our fortunes may revive, albeit modestly.

2) Labour is not as scared as it looks

Near where I live in London is the Union Chapel, a vast neo-Gothic hall.

Will Hutton was there recently to launch his new book This Time No Mistakes: How to Remake Britian. I have interviewed Will for the podcast, which should be out in a couple of days. For now, I’ll just say his book is a classic combination of liberal and left thought, and makes the case for radical reform. Keir Starmer arrived on stage to the cheers of the crowd and endorsed Hutton’s findings.

The fashionable view is that Labour has abandoned difficult policies so as not to alienate frightened voters, and I can see why people think that way.

The grand plan for green job creation has been hacked back after fears the markets would not wear it. The majority of people in this country, and the overwhelming majority of people who vote for opposition parties, now recognise that Brexit was a disastrous error. Year in year out it drags the country down. And yet Starmer, who once argued for a second referendum, is terrified of mentioning the subject in case he upsets a minority in marginal seats.

There was a depressing little vignette a few days ago when the European Commission laid out proposals for open movement to millions of 18- to 30-year-olds from the EU and UK, allowing them to work, study and live in respective states for up to four years. Labour joined the Tories in rejecting the offer.

It would rather squash the aspirations of young people than lay itself open to the charge that it was taking us back towards EU membership.

Yet Rachel Reeves, Keir Starmer and David Lammy talk about the need for cooperation. “Success will rest on forming new bilateral and multilateral partnerships, and forging a closer relationship with our neighbours in the European Union,” Reeves said as she explained her economic programme.

Meanwhile the UK has been ruled by Conservatives for so long our battered minds can underestimate how much the country will change when they are thrown out.

The new parliament will be filled with politicians who support renters, more home building and the EU. They will at least be interested in a land value tax and a universal basic income. Radical that ideas have been forbidden for years will soon seem normal.

3) The impetus for change

The last Labour government of 1997 to 2010 did not change economic fundamentals for what seemed at the time to be a very good reason.

When it came to power neo-liberalism worked. Indeed, is easy to forget now how successful the ideology appeared before the crash of 2008. Politicians like Gordon Brown and Tony Blair accepted much of what Margaret Thatcher had done because they thought they had no choice. Everyone knew, or thought they knew, that this was how you ran an economy.

None of that certainty pertains today. The Brexit nationalism that succeeded neo-liberalism has failed. Starmer and Reeves will not be like Blair and Brown: they will have no good reason to cling to discredited ideas.

That does not mean they won’t cling to them for fear of the Tory press or swing voters or because of their own intellectual failings. There is no guarantee that countries will turn themselves round. The UK could go the way of Argentina or Italy.

But the Labour leadership is made of serious politicians, and I keep asking myself why would serious politicians want to preside over decline? I can’t see why they would.

As I said, maybe I will regret writing this piece. But for the moment I think we can enjoy a rare moment of optimism.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

February 1, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

FEB 2, 2024

One of the biggest stories of 2023 is that the U.S. economy grew faster than any other economy in the Group of 7 nations, made up of democratic countries with the world’s largest advanced economies. By a lot. The International Monetary Fund yesterday reported that the U.S. gross domestic product—the way countries estimate their productivity—grew by 2.5%, significantly higher than the GDP of the next country on the list: Japan, at 1.9%.

IMF economists predict U.S. growth next year of 2.1%, again, higher than all the other G7 countries. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta projects growth of 4.2% in the first quarter of 2024.

Every time I write about the booming economy, people accurately point out that these numbers don’t necessarily reflect the experiences of everyone. But they have enormous political implications.

President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen, and the Democrats embraced the idea that using the government to support ordinary Americans—those on the “demand” side of the economy—would nurture strong economic growth. Republicans have insisted since the 1980s that the way to expand the economy is the opposite: to invest in the “supply side,” investors who use their capital to build businesses.

In the first two years of the Biden-Harris administration, while the Democrats had control of the House and Senate, they passed a range of laws to boost American manufacturing, rebuild infrastructure, protect consumers, and so on. They did so almost entirely with Democratic votes, as Republicans insisted that such investments would destroy growth, in part through inflation.

Now that the laws are beginning to take effect, their results have proved that demand-side economic policies like those in place between 1933 and 1981, when President Ronald Reagan ushered in supply-side economics, work. Even inflation, which ran high, appears to have been driven by supply chain issues, as the administration said, and by “greedflation,” in which corporations raised prices far beyond cost increases, padding payouts for their shareholders.

The demonstration that the Democrats’ policies work has put Republicans in an awkward spot. Projects funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, are so popular that Republicans are claiming credit for new projects or, as Representative Maria Elvira Salazar (R-FL) did on Sunday, claiming they don’t remember how they voted on the infrastructure measure and other popular bills like the CHIPS and Science Act (she voted no). When the infrastructure measure passed in 2021, just 13 House Republicans supported it.

Today, Medicare sent its initial offers to the drug companies that manufacture the first ten drugs for which the government will negotiate prices under the Inflation Reduction Act, another hugely popular measure that passed without Republican votes. The Republicans have called for repealing this act, but their stance against what they have insisted is “socialized medicine” is showing signs of softening. In Politico yesterday, Megan Messerly noted that in three Republican-dominated states—Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi—House speakers are saying they are now open to the idea of expanding healthcare through Medicaid expansion.

In another sign that some Republicans recognize that the Democrats’ economic policies are popular, the House last night passed bipartisan tax legislation that expanded the Child Tax Credit, which had expired last year after Senate Republicans refused to extend it. Democrats still provided most of the yea votes—188 to 169—and Republicans most of the nays—47 to 23—but, together with a tax cut for businesses in the bill, the measure was a rare bipartisan victory. If it passes the Senate, it is expected to lift at least half a million children out of poverty and help about 5 million more.

But Republicans have a personnel problem as well as a policy problem. Since the 1980s, party leaders have maintained that the federal government needs to be slashed, and their determination to just say no has elevated lawmakers whose skill set features obstruction rather than the negotiation required to pass bills. Their goal is to stay in power to stop legislation from passing.

Yesterday, for example, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), who sits on the Senate Finance Committee and used to chair it, told a reporter not to have too much faith that the child tax credit measure would pass the Senate, where Republicans can kill it with the filibuster. “Passing a tax bill that makes the president look good…means he could be reelected, and then we won’t extend the 2017 tax cuts,” Grassley said.

At the same time, the rise of right-wing media, which rewards extremism, has upended the relationship between lawmakers and voters. In CNN yesterday, Oliver Darcy explained that “the incentive structure in conservative politics has gone awry. The irresponsible and dishonest stars of the right-wing media kingdom are motivated by vastly different goals than those who are actually trying to advance conservative causes, get Republicans elected, and then ultimately govern in office.”

Right-wing influencers want views and shares, which translate to more money and power, Darcy wrote. So they spread “increasingly outlandish, attention-grabbing junk,” and more established outlets tag along out of fear they will lose their audience. But those influencers and media hosts don’t have to govern, and the anger they generate in the base makes it hard for anyone else to, either.

This dynamic has shown up dramatically in the House Republicans’ refusal to consider a proposed border measure on which a bipartisan group of senators had worked for four months because Trump and his extremist base turned against the idea—one that Republicans initially demanded.

Since they took control of the House in 2023, House Republicans have been able to conduct almost no business as the extremists are essentially refusing to govern unless all their demands are met. Rather than lawmaking, they are passing extremist bills to signal to their base, holding hearings to push their talking points, and trying to find excuses to impeach the president and Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas.

Yesterday the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal, which is firmly on the right, warned House Republicans that “Impeaching Mayorkas Achieves Nothing” other than “political symbolism,” and urged them to work to get a border bill passed. “Grandstanding is easier than governing, and Republicans have to decide whether to accomplish anything other than impeaching Democrats,” it said.

Today in the Washington Post, Jennifer Rubin called the Republicans’ behavior “nihilism and performative politics.”

On CNN this morning, Representative Dan Goldman (D-NY) identified the increasing isolation of the MAGA Republicans from a democratic government. “Here we are both on immigration and now on this tax bill where President Biden and a bipartisan group of Congress are trying to actually solve problems for the American people,” Goldman said, “and Chuck Grassley, Donald Trump, Mike Johnson—they are trying to kill solutions just for political gain."

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#economic news#economic policy#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#history#WAPO#Wall Street Journal#supply side economics#the demand side#greedflation#extremist Republicans

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Is Canada’s Economy Falling Behind America’s? The Country Was Slightly Richer Than Montana In 2019. Now It Is Just Poorer Than Alabama

— September 30, 2024 | The Economist

Photograph: Associated Press (AP)

The economies of Canada and America are joined at the hip. Some $2bn of trade and 400,000 people cross their 9,000km of shared border every day. Canadians on the west coast do more day trips to nearby Seattle than to distant Toronto. No wonder the two economies have largely moved in lockstep in recent decades: between 2009 and 2019 America’s gdp grew by 27%; Canada’s expanded by 25%.

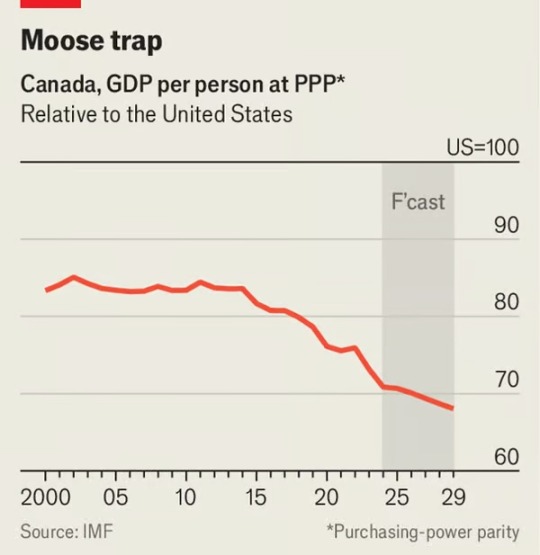

Yet since the pandemic North America’s two richest countries have diverged. By the end of 2024 America’s economy is expected to be 11% bigger than five years before; Canada’s will have grown by just 6%. The difference is starker once population growth is accounted for. The imf forecasts that Canada’s national income per head, equivalent to around 80% of America’s in the decade before the pandemic, will be just 70% of its neighbour’s in 2025, the lowest for decades. Were Canada’s ten provinces and three territories an American state, they would have gone from being slightly richer than Montana, America’s ninth-poorest state, to being a bit worse off than Alabama, the fourth-poorest.

The performance gap owes little to covid-19 itself. Canada did have a deeper recession than America after covid struck, partly because of stricter and longer lockdowns. Its gdp fell by 5% in 2020, compared with 2.2% in America. But Canada soon caught up. The country’s national income grew by 4% between 2019 and 2022, nearly on par with America’s, which expanded by 5% over the period.

The first of these is the services industry, which makes up about 70% of Canada’s gdp. In the aftermath of the pandemic Americans splurged on goods, which boosted manufacturers north of the border (American consumers gobble up around 40% of Canadian factories’ output). But they have since switched back to spending on domestic services. “The composition of American growth hasn’t been favourable to Canada,” says Nathan Janzen of Royal Bank of Canada (rbc), a bank. The job of powering Canada’s economy, therefore, falls even more to its own services sector, which relies on demand from Canadian households and the government.

Instead the divergence is more recent: since 2022 America’s economy has motored ahead, leaving Canada’s in the dust. The reason is not some bump on the road but what lies under the bonnet. Two drivers of Canadian growth have sputtered.

Chart: The Economist

Unfortunately, that demand has been throttled by higher interest rates. Monetary policy has had more “traction” in Canada than in America, says Tiff Macklem, the central-bank governor. In the latter, most mortgages are fixed for 30 years, whereas in Canada they are typically set for five. A greater share of Canadians than Americans have already seen their mortgage payments rise. This is all the more painful as Canadian households bear more debt, relative to income, than anywhere in the g7 club of large, rich countries. They now fork out an average 15% of their income to pay back debt, up one percentage point since 2019. And unlike Uncle Sam, Canada’s government has not tried to soften the blow by loosening the purse strings. It ran a deficit of just 1.1% of gdp in 2023, compared with 6.3% in America.

The second faltering growth driver is Canada’s petroleum industry, which accounts for 16% of exports. Canada underinvested in new production for years after 2014, when a collapse in oil prices hurt its fuel-dependent economy. In America, by contrast, oil-producing states suffered but consumers cheered. When prices spiked after Russia invaded Ukraine, investors did more to support American shalemen; the country’s crude output has rocketed. It was one-quarter higher in the first seven months of 2024 than it was during the same period six years ago. Canada’s has grown by only 11% over the same period.

Oil’s decline penalises Canada’s economy at large, because it is one of the country’s most productive sectors. That adds to a long-standing productivity problem. Growth in output per hour worked across Canada has been sluggish for two decades. It increasingly resembles Europe rather than America, which has benefited from a tech boom that has largely eluded Canada. Its gdp per capita since the pandemic has risen more slowly than that of every other g7 country bar Germany.

What Canada lacked in productivity it could long make up by having more workers, thanks to high immigration. Between 2014 and 2019 its population grew twice as fast as America’s. Canada has historically been good at integrating migrants into its economy, lifting its gdp and tax take. But integration takes time, especially when migrants come in record numbers. Recently immigration has sped up, and the newcomers seem less skilled than immigrants who came before. In 2024 Canada saw the strongest population growth since 1957. Many arrivals are classified as “temporary residents”, including low-skilled workers and students. They are more likely to be unemployed or in low-earning jobs, dampening growth in income per person. Canada’s unemployment rate rose to 6.6% in August, from 5.1% in April 2023.

Take all this together and it is clear that the seeds of the decoupling were sown much earlier than the pandemic, with sagging services the latest in a series of ailments. There are no quick fixes. Canada’s central bank has cut interest rates three times so far this year, from 5% in May to 4.25% today. But many borrowers will still feel worse off because they have yet to renew their mortgages. Immigration restrictions have been introduced, including a cap on international students, but that won’t solve Canada’s chronic productivity problem. Catching up to Alabama may soon seem like a distant dream. ■

#Finance & Economics#Economic Decoupling#Canada 🇨🇦 🍁#United States 🇺🇸#Canadian Economy#Montana#Alabama

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Lower Classes

George Osborne, former Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, and architect of Tory austerity cuts, was recently summoned to the Covid inquiry to discuss the impact of his cruel and heartless policies on the preparedness of the NHS to deal with the pandemic. Needless to say, he accepted NO responsibility what-so-ever.

“He denied that austerity depleted health and social care capacity. He denied that the state of the social care system became worse in his time in office. And he denied that austerity has any connection to worse health outcomes for the most disadvantaged in UK society.” (TUC: 20/06/23)

It wasn’t as if he didn’t know what would happen to our health and social services. There were plenty of warning signs and advice being given, advice he deliberately chose to ignore.

“A strong warning that austerity policies can do more harm than good has been delivered by economists from the International Monetary Fund, in a critique of the neoliberal doctrine that has dominated economics for the past three decades.” (Guardian: 27/05/16)

Why did Osborne ignore the warnings of economic groups like the IMF and other reputable forecasters? He did it to save the Tory Party’s rich friends in banking, business and commerce. Osborne himself admitted as much when he told the Covid inquiry:

“If we had not had a clear plan to put public finances on a sustainable path then Britain might have experienced a fiscal crisis…” (LBC: 20/06/23

So, “protecting" the economy and the rich was more important than protecting public services and the most vulnerable in society. The irony here is that borrowing rates were at an ALL TIME low during Tory austerity cuts so borrowing money to help essential public services could have been done very cheaply. What is even more ironic is that Osborne’s austerity programme was based on a false premise.

“George Osborne plunged the UK into austerity “all for nothing” due to an error on an Excel spreadsheet... The whole reason that George Osborne and David Cameron launched austerity was because of a Harvard paper that did a whole bunch of calculations – which showed that if your debt was exceeding 90 per cent of GDP then the economy would shrink… Actually it had been done on a spreadsheet and a bunch of rows of data had been missed out, which if they had been included it would have shown that the economy wouldn’t shrink.”

(The London Economic: 22/09/22)

In other words, if Osborne had done his job correctly and checked the data he would have discovered there was absolutely no need for austerity cuts and the resulting catastrophic consequences.

I use the term “catastrophic consequences” advisedly. Not only have ALL of our public services been starved of funding under Tory austerity cuts, to the point they are all on the verge of collapse, but worse still our children and grandchildren have suffered physically from Tory austerity.

“Children raised under UK austerity shorter than European peers, study finds. Average height of boys and girls aged five has slipped due to poor diet and NHS cuts, experts say” (Guardian: 21/06/23)

Children's height is a very good indicator of general living conditions, such as poverty, illness, stress, infections and sleep quality. Studies show that between 2010 and 2020,UK children who grew up during this period have fallen 30 places behind there European peers in height. Even more frightening is the fact that British children are now displaying alarming rates of increasing poor health, 700 children a year being admitted to hospital with malnutrition, rickets or scurvy.

Under Osborne’s austerity cuts the rich have grown richer. In 2018, the Equality Trust reported that the rich had increased their wealth by £274 billion over a five-year period. Meanwhile, as the rich continue to see their wealth increase many ordinary families are seeing the average height of their children shrink. Put brutally, the Tory Party has been, and continues to, deliberately sacrifice the health of the nations children for their own personal gain and that of their rich friends.

The term “lower class" was never more poignant.

#uk politics#health#childrens height#austerity#georege osborne#inequality#greed#malnutrition#scruvy#sacrifice#wealth.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why in reality has betting on macroeconomic stability had negative consequences and not contributed to stability?

Until the 1970s, inflation was considered the main enemy of the economy. Many countries experienced catastrophic hyperinflation, although it did not reach extreme levels. Economic instability caused by high or variable inflation was not conducive to attracting investment, which hindered development. This influenced the approach to managing government budget deficits and encouraged the creation of politically independent central banks. These banks deliberately focused on controlling inflation, as economic stability was a key factor for long-term investment.

Despite the victory over inflation, the world economy has become less resilient. The optimistic claims of the past thirty years that price fluctuations had been successfully controlled did not take into account the extreme instability exhibited by economies around the world. Numerous financial crises, including the global crisis of 2008, have left many with debt, bankruptcy and unemployment. An overemphasis on fighting inflation has diverted attention away from employment issues. The pursuit of growth at the expense of flexibility in the labor market has led to precarious jobs, making people worse off. Despite claims that stable prices promote economic growth, measures to reduce inflation have caused only a slow economic recovery since the 1990s, when inflation was thought to have been defeated.

In the early 2000s, Japan's central bank governor Masaru Hayami refused to increase the money supply for fear that doing so could lead to inflation, even though the country was experiencing deflation and falling prices at the time. However, there is no convincing evidence that an increase in inflation will inevitably lead to hyperinflation, or that such a likelihood is likely. No one argues that hyperinflation is desirable or at least acceptable, but it remains debatable whether any inflation is harmful, regardless of its level.

Since the 1980s, free-market economists have been able to convince the world community that economic stability should be accompanied by minimal to no inflation. They argued that inflation was bad for the economy and should be avoided at all costs. An acceptable level of inflation, they argued, was about 1.3%. This was the figure suggested by Stanley Fischer, a former professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and chief economist at the IMF from 1994-2001.

In fact, there is no evidence that low inflation is bad for the economy. Even studies by pro-free-market economists working with organizations such as the University of Chicago or the IMF show that inflation below 8-10% has no effect on economic growth. A number of other studies set the inflation threshold even higher, at 20-40%, which also has no noticeable negative effect on economic growth.

The experience of a number of countries also shows that sufficiently high inflation can coexist with rapid economic growth. Brazil had an average inflation rate of 42% in the 1960s and 1970s, but remained one of the fastest growing economies in the world, with per capita income growth of 4.5% per year.

During the same period, per capita income in South Korea grew by 7% annually, despite an average annual inflation rate of nearly 20%, well above many Latin American countries. Since 1996, Brazil, having overcome the traumatic stage of high inflation and hyperinflation, began to contain inflation by raising the real interest rate to one of the highest in the world at 10-12% per year. As a result, inflation fell to 7.1% per annum, but economic growth was affected as the increase in per capita income did not exceed 1.3% per annum.

A similar situation was observed in the Republic of South Africa since 1994, when inflation control became a priority, which also led to an increase in the interest rate to a level comparable to Brazil's.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the low inflation policy seemed intended to create a sustainable and stable economic environment, but in practice has had negative consequences. The excessive focus on controlling inflation has detracted from other important aspects such as employment and the quality of life of people. As a result, even with low inflation, economic growth has been stunted and per capita income has not been able to reach significant heights.

The experience of countries such as Brazil and South Africa shows that high inflation can coexist with rapid economic development. Thus, the question arises: does a reliance on macroeconomic stability with a focus on low inflation really contribute to a more sustainable world economy? It may well be necessary to reconsider economic policy approaches in the future, given the diversity of factors affecting the real state of the economy.

0 notes

Text

Income Inequality and Its Influence on Economic Growth: An In-Depth Analysis

Income inequality has become a pressing issue in modern economies, raising questions about its impact on economic growth and development. As economies evolve, understanding how disparities in income distribution affect overall economic performance becomes crucial. For students studying development economics, comprehending these dynamics is essential, and Development Economics homework help can offer valuable insights into these complex relationships. This blog explores the intricate relationship between income inequality and economic growth, shedding light on the implications and offering a comprehensive analysis.

The Relationship Between Income Inequality and Economic Growth

Income inequality refers to the unequal distribution of income across various segments of society. It is a phenomenon observed globally, with significant differences in income levels between the wealthiest and the poorest. Economists have long debated the impact of income inequality on economic growth, with varying theories and perspectives emerging over time.

Theoretical Perspectives:Several theories provide insights into how income inequality might influence economic growth. One prominent view is the trickle-down economics theory, which posits that benefits provided to the wealthy will eventually "trickle down" to the rest of society through increased investment, job creation, and economic growth. According to this perspective, income inequality might stimulate economic growth by incentivizing the wealthy to invest and spend more.Conversely, the classical economic theory suggests that income inequality can hinder economic growth. This view argues that when income is concentrated in the hands of a few, it can lead to under-consumption by the majority, limiting overall economic demand. Reduced consumption can stifle economic growth, as businesses may face lower sales and decreased incentives to invest.

Empirical Evidence:Empirical studies offer mixed evidence regarding the relationship between income inequality and economic growth. Some research indicates that moderate income inequality can foster economic growth by encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship among the wealthier segments of society. However, extreme income inequality is often associated with slower economic growth, increased social unrest, and reduced social mobility.For instance, a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that countries with lower income inequality tend to experience more sustained economic growth. The study highlights that high levels of inequality can lead to lower levels of human capital investment and reduced economic opportunities for disadvantaged groups, ultimately hindering overall growth.

The Impact of Income Inequality on Economic Development

Income inequality not only affects economic growth but also has broader implications for economic development. Development economics focuses on understanding how economies evolve and improve over time, and income inequality plays a critical role in this process. Here are some key implications of income inequality on economic development:

Human Capital and Education: Income inequality can influence access to education and healthcare, which are vital components of human capital development. In societies with high income inequality, disadvantaged groups may face barriers to accessing quality education and healthcare, limiting their ability to contribute to economic growth effectively. This inequality in access can perpetuate a cycle of poverty and hinder overall development. Addressing income inequality through targeted policies and support can help improve access to education and healthcare for disadvantaged groups, fostering a more equitable distribution of human capital and enhancing economic development. For students seeking deeper insights into these issues, Development Economics homework help can provide a detailed understanding of how policies can mitigate the negative effects of income inequality.

Social Cohesion and Stability: High levels of income inequality can lead to social unrest and instability. When a significant portion of the population feels excluded from economic progress, it can result in increased social tensions and decreased social cohesion. This instability can have detrimental effects on economic development by undermining investor confidence and disrupting economic activities. Promoting social cohesion through policies that address income inequality can contribute to a more stable and conducive environment for economic development. Ensuring that the benefits of economic growth are distributed more equitably can help foster a sense of inclusion and stability, which is crucial for long-term development.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Income inequality can also influence innovation and entrepreneurship. In economies with high income inequality, the wealthy may have greater access to resources and opportunities for investment in innovative ventures. This can potentially lead to increased economic growth driven by technological advancements and entrepreneurial activities. However, excessive income inequality may limit the opportunities available to the broader population, stifling potential innovations and entrepreneurial activities among disadvantaged groups. A more balanced income distribution can help ensure that a wider range of individuals have the opportunity to contribute to innovation and entrepreneurship, driving sustainable economic development.

Policy Implications and Strategies

Addressing the impact of income inequality on economic growth and development requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers and economists need to consider various strategies to mitigate the negative effects of income inequality and promote more inclusive economic growth. Some key strategies include:

Progressive Taxation:Implementing progressive tax systems can help redistribute income more equitably and reduce income inequality. By taxing higher incomes at higher rates and using the revenue to fund social programs and services, governments can promote greater income equality and support economic development.

Investing in Education and Healthcare:Investing in education and healthcare for disadvantaged groups is crucial for reducing income inequality and promoting economic development. By ensuring that all individuals have access to quality education and healthcare, societies can enhance human capital and foster a more equitable distribution of economic opportunities.

Social Safety Nets:Developing robust social safety nets can help protect vulnerable populations from the adverse effects of income inequality. Programs such as unemployment benefits, social security, and poverty alleviation initiatives can provide essential support and reduce the negative impacts of income inequality on economic growth and development.

Promoting Inclusive Growth:Fostering inclusive growth involves designing policies that ensure the benefits of economic progress are shared more equitably across society. By promoting policies that address income disparities and create opportunities for all individuals, governments can support more sustainable and inclusive economic development.

Conclusion

The relationship between income inequality and economic growth is complex and multifaceted. While some theories suggest that income inequality can stimulate economic growth by incentivizing investment and entrepreneurship, extreme income inequality often hinders growth by reducing consumption, undermining social cohesion, and limiting access to opportunities. Understanding these dynamics is essential for students studying development economics, and Development Economics homework help can provide valuable insights into the interplay between income inequality and economic growth. By implementing targeted policies and strategies, societies can address the negative effects of income inequality and promote more inclusive and sustainable economic development.

Through careful analysis and thoughtful policy interventions, it is possible to mitigate the adverse impacts of income inequality and foster a more equitable and prosperous economic future.

source: https://www.economicshomeworkhelper.com/blog/income-inequality-and-economic-growth/

#economics#student#education#university#homework helper#do my economics homework#economics homework helper#business economics homework helper

0 notes

Text

Our Unresolved Problem(s)

Problems unresolved are not unlike cancers that fester and fester until they burst with pain and devastation. The longer they fester, the greater the pain, the greater the devastation. Such it is with our great nation, a nation of many problems—currently, it seems, tired, broke, hungry, polarized, and twisting in the winds.

To solve a problem, any problem, one must first identify it, get to the absolute root of the matter, decide what to do about it, and do it—too often a problem in and of itself. For far too long, we the people of the United States of America haven’t done this, preferring to shift our problems to a “back burner”, dealing with them with temporary “fixes”, passivism, and procrastination, which has cost us dearly.

I submit to you that in these, the greatest times in the history of civilization, the two greatest problems confronting our nation today are a lack of concerted direction and xenophobia, i.e. racial discrimination. We have many serious problems before us—very serious; but, before they can be effectively resolved, we must above all, first, resolve these two.

I have discussed this in prior postings to this blog, from various aspects. We are heading in a direction, if we are not already there, wherein we are being ruled by an oligarchy of the Corporatocracy and Power Elite which, contrary to our presently being a democratic republic “of the people, by the people, and for the people”, the extent of our freedoms will be determined by them. This is just not The United States of America. This is a global thing. Even now many of the rules under which you and I live are under the control of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Agenda 21 of the United Nations, etc. which transcends national boundaries. Even now, our government is negotiating so-called Free Trade Agreements in secret (I’m thinking specifically of the Trans-Pacific Partnership [TPP], which will affect jobs and living standards for millions of us). We the people will have no say in it. Some will tell you we freely elected those who facilitate this, our Congress. We did? Keep in mind all the money that flows into the coffers of our representatives through the lobbyists of these Corporatists. Some even write the rules that go into these agreements. Does your representative answer your phone calls? You can bet on it. He, or she, answers theirs.

In 2013, Keynesian economist Joseph Stiglitz, himself a renowned economist, warned that the TPP presented “grave risks” and it “serves the interests of the wealthiest”. Organized labor in the U.S. argues that the trade deal would largely benefit big business at the expense of the workers in manufacturing and service industries. The Economic Policy Institute and the Center for Economic and Policy Research have argued that the TPP could result in further job losses and declining wages. In December 2013, 151 House Democrats signed a letter written by Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) and George Miller (D-Calif.) opposing the “Fast Track”

Let me briefly explain what is meant by the “Fast Track”. According to Wikipedia, “the fast track negotiating authority for trade agreements is the authority of the President of the United States to negotiate an international agreement that Congress can approve or disapprove but cannot amend or filibuster. Also called trade promotion authority (TPA) since 2002, fast track negotiating authority is a temporary and controversial power granted to the President by Congress.” Wikipedia also states that “The authority was in effect from 1975 to 1994, under the Trade Act of 1974, and from 2002 to 2007 by the Trade Act of 2002. Although it expired for new agreements on July 1, 2007, it continued to apply to agreements already under negotiation until they were eventually passed into law in 2011. In 2012, the Obama administration began seeking renewal of the authority.”

You can read for yourself on Wikipedia a history and summary of the ongoing Trans-Pacific Partnership. This is just one event going on with the Corporatocracy and Power Elite, our Shadow Government. There are many more; and, in my mind, they are not in favor of the people—only the 1%, the very very rich and elite. Whether you believe in God or not, God made people. People made business. Business is supposed to serve the people. People should be in charge—not business. We must turn this around before we become their serfs.

I submit to you this is the greatest problem for our nation today. This is not the direction in which we should continue, and we must change that direction now. We the people must take back our country; but, to do that, we must all participate by voicing our demands. We cannot do that with only 40%, or whatever, going to the polls.

As I said above, the second greatest problem for our nation today is xenophobia, i.e. racial discrimination. I will post a candid discussion of this subject in my next blog. I’m sure what I say will be controversial, but it must be said. The successful resolution of almost all our future problems will depend upon the resolution of these two, our domination by the Corporatocracy and Power Elite and our resolution of Racial Discrimination.

Please, think about these things. Do you want our country/your country to be run by these people—the huge corporations, banks, and the wealthy; or, do you want us to be a democratic republic as per our Constitution, a nation of the people, by the people, and for the people? I tell you. It is going, going, gone—unless you do something about it. You may think this is all a big joke but it isn’t. It is in your hands. What are you going to do and when? When? From: Steven P. Miller @ParkermillerQ, gatekeeperwatchman.org Tap Pictures Always: Founder of Gatekeeper-Watchman International Groups, Saturday, June 1, 2024, Jacksonville, Florida., USA. X ... @ParkermillerQ #GWIG, #GWIN, #GWINGO, #Ephraim1, #IAM, #Sparkermiller, #Eldermiller1981 Thank you for sharing: Https://gatekeeperwatchman.org/post/751889961062744064/daily-devotionals-for-may-30-2024-proverbs-gods? MY GROUP and Not FACEBOOK/METAS: https://www.facebook.com/groups/Sparkermiller.JAX.FL.USA

0 notes

Text

Debate #5: Conditioning Aid on Rights for SOGI/LGBTQ Populations (Simon)

Background: On February 24th, 2014, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni signed the Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA), also known as the ‘kill-the-gays bill,’ a modified version of a tabled 2009 Anti-Homosexuality Bill, sentencing those convicted of homosexuality to life imprisonment and requiring “citizens to report anyone suspected of being gay” (see the Economist editorial). After Museveni signed the AHA, Norway, the Netherlands, and Denmark cut aid to Uganda; Sweden and the United States redirected aid from the Ugandan government to civil society and NGOs; and the World Bank postponed a $90 million loan to Uganda’s health service sector (see Saltnes, 11 and Economist). Conditional and values-based aid has been a popular tactic by states and international organizations such as the World Bank and the IMF for decades (see Ramcharan, 3). Yet the effectiveness and morality have also been hotly contested. Within the context of Uganda’s 2014 AHA, our “debate” seeks to highlight four perspectives on conditioning aid based on the rights provided to particular sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)/LGBTQ populations and these perspectives’ arguments for and/or against the practice.

Aid-Giver Perception In Favor Of Conditionality

Since Uganda is a geopolitically small nation, it can be easily pressured by Western countries to improve gay rights, unlike a larger nation that lacks in gay rights. Regardless of the precedence that it could set, imposing financial pressure on Uganda to change a policy that is radical, even by the standards of most anti-LGBT government policies.

President Yoweri Museveni has been ruling Uganda autocratically since 1986, so it is hard to argue that Uganda’s policy decisions reflect the beliefs of the Ugandan population as a whole (Britannica). Though on paper, Uganda holds multiparty elections, Museveni’s victories have been accused of being fraudulent and he has recently been accused of attempting to position his son as the successor of the Ugandan presidency. As a result, foreign aid should consider the fact that Ugandan governmental policy is non-representative of the Ugandan population, and the funding itself doesn’t undergo the same internal due-diligence that a functioning democracy should. As a result, it is impossible for Uganda to enforce change from the ground up, and these types of interventions could uniquely target the political elites of Uganda and enact important changes such as gay rights. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Yoweri--Museveni

As argued by former US Secretary of State John Kerry, Uganda’s uniquely extreme new policy is comparable to anti-semitic policy in Germany and apartheid policy in South Africa (BBC). Since this is an apt comparison, it is difficult to assert that states and international organizations should tacitly approve of such extreme policies by maintaining the status quo of foreign aid just because they are being made in the geopolitically insignificant country of Uganda. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26378230

Aid-Giver Perception Against Conditionality

Geopolitical incentive to provide aid that competes with the non-conditionality of China’s foreign aid(Wan)https://amp.dw.com/en/how-unconditional-is-chinas-foreign-aid/a-43499703

The poverty rate in Uganda is around 40%, therefore it would be cruel to withhold aid, even though the Ugandan government has no political interest in improving gay rights (World Bank).

In terms of the World Bank specifically, its goal is to tackle extreme poverty, so its withholding of funding for the Ugandan health system shouldn’t be based on the condition of gay rights(Leach). Furthermore, this diversion of focus could lower the effectiveness of the World Bank in doing its prescribed job, therefore they should focus on reducing poverty and not try to branch out to approaching more social causes.

Efforts by Western countries to diffuse LGBT rights in Uganda overshadows the fact that Western countries are culpable of causing Ugandan homophobia in the first place through mechanisms of intervention (Weiss, 6). By continuing the regime of imposing policies on a country receiving foreign aid, the providers of foreign aid risk sabotaging their current efforts to enforce gay rights in the event that a new administration takes over the conditioning of foreign aid and carries a different moral compass but maintains the bargaining chip of influencing gay rights.

Homophobia is an easily diffusible political norm due to its lack of necessity for a self-defined group, whereas LGBT advocates have to organize at a lower level in order to influence political elites (Weiss, 5). In addition, the diffusion of LGBT advocacy only follows diffusion of political homophobia, as a non-homophobic society logically doesn’t need LGBT advocacy (Weiss, 16). As a result, it is uniquely difficult to effectively install progressive LGBT policy since the precursor to this policy is always the existence of homophobia. In this case of Uganda, it might prove to be ineffective to direct a change in such a pervasive ideology in a way that doesn’t come from the direction of compelling elite political circles from the ground-up, as opposed to from the top down in the case of foreign aid. Historical Perception In Favor Of Conditionality

The argument can be made that aid itself lacks historical effectiveness in many cases, therefore the restriction of aid wouldn’t necessarily make donors the culprit of a negative humanitarian impact in a situation where funding largely leads to corruption that worsens the condition of democracy and money often doesn’t arrive in the humanitarian-oriented places that it should. Alternatively, the use of this funding on a conditional basis that stipulates for progressive policy could seriously impact the political elites of Uganda in such a way that motivates them to change their political ideology.

In the case of Lebanon, its $133 billion of capital inflows from 1993-2012 haven’t tangibly led to an increase in development or quality of life (Finckenstein, 2). https://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/updates/LSE-IDEAS-How-International-Aid-Can-Do-More-Harm-Than-Good.pdf

Foreign aid can lead to increased corruption and therefore increasingly undemocratic political systems in recipient states(Finckenstein, 3)

Unconditional aid can give recipients the idea that their behavior and level of implementation of aid is unimportant in the process of gaining further funding(Finckenstein, 6).

When compiling a large number of cases, the correlation between official aid and economic growth is statistically insignificant, but slightly positive(Edwards).https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/11/how-effective-is-foreign-aid/ Historical Perception Against Conditionality

Sanctions haven’t worked historically and even when they have, there have been significant negative externalities that make sanctions a far less attractive tool in enacting change.States have still signed discriminatory laws/ignored the threats of sanctions

Targets states rather than norm influencers such as NGOs and churches

IMF loans with high amounts of contingencies have led to anti-democratic political consequences for Latin American countries between the years of 1998-2003 (Brown, 431). https://www.jstor.org/stable/25652919

In the last 30 years, foreign aid has accelerated GDP growth by an annual 1% in the most poor recipient countries.(Edwards)https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2014/11/how-effective-is-foreign-aid/

The effectiveness of pushing for the achievement of specific reforms in aid conditionality is less effective than focusing on a broader qualification of progress(Spevacek)https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnadm068.pdf

“a review of all U.S. sanctions since 1970 shows that targeted countries altered their behavior in a way that the U.S. hoped they would just 13 percent of the time”(Hirsch)

Harsh sanctions can often have such an impact on humanitarian conditions that it turns citizens against sanctioning countries(Hirsch)

In the example of Iran in 2012, sanctions that kicked Iran off the SWIFT transaction system successfully pushed Iran to accept limitations to its nuclear program, but the externality of this sanction caused a plummet in Iranian living standards, and eventually caused Iran to suffer disproportionately in the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were unable to gain access to medical supplies (Hirsch). In this historical example of what is a successful use of sanctioning/aid restriction to compel change in a single policy, there was such an extreme negative outcome in human rights that the value of such imposition of policy is questionable.

0 notes

Text

IMF: AI could boost growth but worsen inequality

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/imf-ai-could-boost-growth-but-worsen-inequality/

IMF: AI could boost growth but worsen inequality

.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper display:none; img width:100%;

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that AI could boost global productivity and growth, but may displace jobs and worsen inequality.

In a new analysis, IMF economists examined AI’s potential impact on the global labour market. While many studies foresee jobs being automated by AI, the technology will often complement human work instead. The IMF analysis weighs up both scenarios.

The findings are striking: almost 40 percent of jobs globally are susceptible to automation or augmentation by AI.

Historically, new technologies have tended to affect routine tasks—but AI can also impact high-skilled roles. As a result, advanced economies face greater risks from AI but also stand to gain more of its benefits versus emerging markets.

Per the IMF’s research, about 60 percent of jobs in advanced economies may be impacted by AI. Around half of those jobs could benefit from AI integration, enhancing productivity. For the remainder, AI may execute key human tasks, lowering labour demand, wages, and hiring. In some cases, human jobs could disappear entirely.

In emerging and developing economies, IMF economists predict AI exposure of 40 percent and 26 percent respectively. This suggests fewer immediate AI disruptions than advanced economies. However, many emerging markets lack the infrastructure and skills to harness AI’s benefits. Over time, this could worsen inequality between countries.

The IMF warns AI may also drive inequality within countries. Workers able to exploit AI may become more productive and boost wages, while those who cannot fall behind.

Research shows that AI can accelerate the productivity of less experienced staff. Younger workers could therefore benefit more from AI opportunities whereas older workers may struggle adapting.

Advanced economies are better prepared for AI adoption but must still prioritise innovation, integration, and regulation to cultivate its safe and responsible use. For emerging markets, the priority is developing digital infrastructure and skills.

To assist countries in crafting effective policies, the IMF has introduced an AI Preparedness Index—evaluating readiness in areas such as digital infrastructure, human capital, innovation, and regulation. Wealthier economies – including Singapore, the US, and Denmark – have shown higher preparedness for AI adoption.

The AI era has arrived, and proactive measures are crucial to ensuring its benefits are shared prosperity for all.

(Photo by Levi Meir Clancy on Unsplash)

See also: McAfee unveils AI-powered deepfake audio detection

Want to learn more about AI and big data from industry leaders? Check out AI & Big Data Expo taking place in Amsterdam, California, and London. The comprehensive event is co-located with Digital Transformation Week and Cyber Security & Cloud Expo.

Explore other upcoming enterprise technology events and webinars powered by TechForge here.

Tags: artificial intelligence, ethics, government, imf, impact, inequality, international monetary fund, jobs, report, research, Society, study

#2024#ai#ai & big data expo#ai news#AI-powered#amp#Analysis#artificial#Artificial Intelligence#audio#automation#Big Data#Cloud#coffee#comprehensive#cyber#cyber security#data#deepfake#detection#Digital Transformation#enterprise#Ethics#Ethics & Society#Events#Experienced#Global#Government#growth#hand

0 notes

Text

Let us put to rest at last the idea that Ronald Reagan’s economic policies did any good for American society. In fact what those policies accomplished was a tearing away at the foundation of America’s middle class, pushing millions of families out of middle-class living while closing off opportunities to those families wishing to move up. Reagan’s extreme tax cuts for the rich, his deregulations of corporations, and his attacks on social programs set us on a path back to a dark past—back to the Gilded Age. Today, finally, a new study confirms what historians have known all along: Reagan’s trickle-down theory was a joke. A bad joke.

THE IMF CONFIRMS THAT 'TRICKLE-DOWN' ECONOMICS IS A JOKE

By Jared Keller

If there’s one person most often associated with the origins of trickle-down economics, it’s President Ronald Reagan. But a devastating new report from the International Monetary Fund has declared the idea of "trickle-down" economics to be as much a joke as Will Rogers imagined when he said that money trickles up, not down.

The IMF report, authored by five economists, presents a scathing rejection of the trickle-down approach, arguing that the monetary philosophy has been used as a justification for growing income inequality over the past several decades. "Income distribution matters for growth," they write. "Specifically, if the income share of the top 20 percent increases, then GDP growth actually declined over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down."

This should shock no one: Observers of income inequality over the past five years (especially those fond of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century) will recognize this trend from economic data going back to the end of World War II.

The balance in the distribution of capital is flipped from the majority of the nation to the top 10 percent during the Reagan and Bush administrations, a rapid acceleration of a gradual trend. Income inequality was already growing in the U.S., but the advent of Reaganomics kicked the trend into overdrive. In general, the top one percent of society today derives an increasing portion of income gains from existing capital and wealth.

According to the IMF, countries looking to boost economic growth should concentrate their efforts on the lower segments of society rather than bolstering so-called "job creators" with tax breaks. The study results suggest that raising incomes for the poor and middle class yields measurable improvements to the national economy: Increasing the income share to the bottom 20 percent of citizens by a mere one percent results in a 0.38 percentage point jump in GDP growth. By contrast, increasing the income share of the top 20 percent of citizens yields a decline in GDP growth.

The message of the IMF report is clear: Income and wealth inequality isn’t a class problem, but a national issue. "Widening income inequality is the defining challenge of our time," the authors of the report write. "The poor and the middle class matter the most for growth via a number of interrelated economic, social, and political channels." While disciples of Reaganomics may be clenching their fists, Will Rogers is probably laughing from the grave.

—Jared Keller

1 note

·

View note

Text

New Post has been published on All about business online

New Post has been published on http://yaroreviews.info/2023/06/immigration-can-help-push-down-uk-inflation-says-imf-deputy

Immigration can help push down UK inflation, says IMF deputy

By Ben Chu & Michael Cowan

BBC Newsnight

Immigration that fills gaps in the domestic jobs market can help push down UK inflation, the deputy head of the International Monetary Fund has said.

The Prime Minister has said rates of legal immigration are “too high”.

Yet the IMF’s Gita Gopinath told BBC Newsnight that “with inflation as high as it is there are benefits to having workers come in.”

The government said the immigration system could “flex to the needs of the economy”.

Net migration (the difference between the number of people entering the country and those leaving on a long-term basis) is at a record level in the UK – at 606,000 in 2022, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Meanwhile, UK headline inflation fell to 8.7% year-on-year in April, but core inflation – which excludes volatile food and energy prices – rose to 6.8%, the highest in the G7.

“In this context, with inflation as high as it is, having workers who can fill the shortages in some of the sectors that we’re seeing right now will help with bringing inflation down,” Ms Gopinath, the deputy managing director of the IMF, said.

“So I think there are benefits to having workers come in.”

The latest official statistics showed the UK still had more than one million vacancies in the three months to April 2023.

The industries with the highest vacancy ratios were accommodation and food (5.5%), health and social work (4.5%) and professional scientific jobs (4%).

Economists have identified the UK’s tight labour market, exacerbated by the impact of Brexit on flows of European Union workers and the impact of the Covid pandemic, as one of the main contributory factors to high domestic inflation.

April’s higher-than-expected inflation rates led many to predict the Bank of England will raise interest rates higher than previously thought, from their current 4.5% to above 5%.

Food prices ‘worryingly high’ as sugar and milk soar

Mortgage rates rise after inflation surprise

But Ms Gopinath downplayed the idea that the UK has considerably worse core inflation than other developed economies.

“I wouldn’t make a big difference between small differences in numbers in core inflation,” she said.

Brexit effect

Ms Gopinath also told Newsnight that the IMF stood by its 2018 forecast that Brexit would reduce the long-term growth potential of the UK economy by 2.5% to 4% of GDP, equivalent to £900 to £1,300 per person.

“We put that estimate out around 2018 and we haven’t done an update since then for the reason that we’ve had the pandemic and that we’ve had many other shocks,” she said.

“So just identifying how much is purely Brexit becomes much harder to do. But if you look at the more recent estimates by the Bank of England and others, this is in the ballpark.

“Investment has been weaker since 2016, labour market flexibility has come down and the intensity of trade of the UK with the EU has come down. So all of these factors are in line with a weakening economy.”

In a statement the Treasury said the UK had “moved away from the old model of unlimited, unskilled migration”.

“We now have a points-based immigration system, giving the British people full control of the country’s borders, which is designed to flex to the needs of the economy to ensure we have the skills we need.

“We want businesses to invest in our domestic workforce to fill labour shortages, but where there’s an acute need for staff, we have also been flexible, including putting care homes and the seafood industry on the shortage occupation list,” a spokesperson said.

You can watch the full interview with Gita Gopinath on Newsnight on BBC iPlayer

Related Topics

UK immigration

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Inflation

UK economy

More on this story

Who is allowed to come to live in the UK?

25 May

Chris Mason: Ministers weigh up tricky options on immigration

17 May

Legal migration is too high, says Rishi Sunak

19 May

IMF expects UK economy to avoid recession

23 May

0 notes

Text

In case you hadn’t noticed, the world economy’s gone rather topsy-turvy.

Japan is up while China is down—and in danger of Japan-like deflation. The United States is practicing Japanese-style protectionism and industrial policy, while Japan is championing what Washington used to promote: newer, better open trade rules.

These trends represent a virtual reversal of the neoliberal narrative we had grown used to since the end of the Cold War, when the disintegration of Soviet communism appeared to discredit the whole idea of government-directed economic growth. This was followed by the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in the early 1990s, which in turn touched off a long period of slow, geriatric growth in the granddaddy of the East Asian “miracle.” But the economics profession, having made so many bad calls since this long, strange trip of globalization began, can’t keep up. That’s because most mainstream economists still have trouble admitting that their model of free-market fundamentalism—the “Washington Consensus”—has failed catastrophically, and in several dimensions.

While Brexit has proved a disaster for Britain and the U.S. is floundering with ever-worsening inequality, Japan may well have entered a new chapter of its extraordinary postwar story. It is enjoying a new spurt of activity, including annualized growth of nearly 5 percent in the second quarter and some price and wage increases. These indicators “suggest the economy is reaching a turning point in its 25-year battle with deflation,” as the government said in its annual white paper. Japan also remains socially stable to a degree that should make Americans envious, since it doesn’t suffer the huge income inequality problem that bedevils the United States, though Japan is, of course, far less ethnically diverse. Japan is hardly a perfect model—it is still backward, for example, in recognizing women’s rights—but its Human Development Index is rising among the rich countries. Whether measured by equality, life expectancy, or its stellar jobless rate of 2.7 percent, Japan is today in the “top rung of the most affluent and most successful societies in the world—and now seven and a half years longer than for America,” as economics historian Adam Tooze puts it.

Other economists who have long invoked the Japanese and East Asian “middle way” of market-sensitive government industrial support agree. “I wouldn’t attribute too much to Japan’s quarterly growth rate—but I would give them some credit for not leaving as many people behind,” said Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University. “The big advantage they had was that before their malaise set in, they had achieved a far more egalitarian state.” Or as International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists Fuad Hasanov and Reda Cherif conclude in one recent paper, the Asian miracles’ economic models—mainly the ones used in Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan—“resulted in much lower market income inequality than that in most advanced countries.”

How did East Asia do it? By focusing on export competitiveness and forcing subsidized firms to compete in global markets, these countries created good jobs for the middle class and avoided the pitfalls of failed “import substitution” policies that have characterized bad industry policy in the past across countries from Latin America to Africa. Building upon that, they also imposed progressive tax systems.

By contrast, there is also some agreement that one reason for China’s slowdown is that its dictatorial leader, Xi Jinping, has cracked down too harshly on the market part of the economy, disturbing the delicate balance of government-vs.-market control that began in the late 1970s. Xi “doesn’t seem to know how to use the levers of government with subtlety or within a market framework,” Stiglitz said.

All this is surprising, because in the policy debate with advocates of East Asian-style market intervention, the Washington Consensus had until fairly recently been winning, hands down. “Industrial policy” of the kind practiced by Japan and other East Asian nations was toxic and had to be practiced, at best, below the radar, especially in the United States. Capital flows were heedlessly unleashed around the world and market barriers eliminated at the insistence of both Democrats and Republicans in Washington. When the Asian financial crisis hit in the late 1990s, the neoliberals at first claimed vindication, saying corrupt crony capitalism and heavy government interference were to blame. But after the 2008 crash sank Wall Street—and nearly the entire U.S. financial system—it was clear that the crisis was, in fact, one of global capitalism and the excesses of neoliberalism. The problem in both the U.S. and Asia wasn’t the heavy hand of government so much as its opposite: totally unregulated capital flows and financial markets, not to mention (in the United States) regressive tax policies that favored Wall Street and capital gains earners.

As Eisuke Sakakibara, Japan’s former vice minister of finance and international affairs and one of Asia’s intellectual champions for an alternative model, told me presciently back then: “Global capital markets are responsible to a substantial degree. If you look at the so-called Asia crisis, the root cause has been the huge inflow of capital into Malaysia, Thailand, South Korea, and China. And all of a sudden … all of that has [fled] from those countries. Borrowers have been borrowing recklessly, and lenders have been lending recklessly. And not just Japanese banks. American banks and European banks as well.” Sakakibara proved to be correct, and something similar—indeed, much worse—struck the U.S. economy nearly 10 years later.

Beyond that, it was also clear during this three-decade period that China was paying scant attention to trade rules, deploying among other systematic violations industrial espionage, investment controls, currency manipulation, and intellectual property theft. During the same period, American confidence was badly misplaced that the nation’s high-tech advantages would automatically translate into a new manufacturing age for the middle class. It wasn’t just American capital that was fleeing abroad: By the mid-1990s, it was obvious that Silicon Valley-style startups don’t take one’s economy very far when most of the scale-ups—the manufacturing and downstream jobs, in other words—are happening overseas in low-wage countries.

So neoliberalism’s been dying ever since, and Donald Trump and Joe Biden have delivered the death blows. The most significant failure, perhaps, was not purely economic but social and political. It has become clear that in the United States, as well as in other major Western economies such as Great Britain, deepening inequality brought about by an almost religious devotion to neoliberal thinking has generated jarring social instability and populism on the right and left. Trump and former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson turned the two democracies that built the postwar global economic system into anti-globalist, inward-looking confederacies. Trump focused his ire on starting a trade war and crippling the World Trade Organization (WTO), and Johnson stormed out of the European Union. How did we get to this topsy-turvy place? A little historical perspective might help.

What’s been playing out on the global stage all this time has been nothing less than a historic test of alternative approaches to economic development—and an unprecedented test of social stability, too.

It began about three decades ago, when U.S. President Bill Clinton rolled into office in the triumphalist aftermath of the collapse of the USSR and decided that markets and globalization were the answer—even for formerly progressive Democrats like him. Command economies were utterly discredited. So was big government in the United States. And in the developing world, government intervention—so-called import substitution, meaning the support of domestic industry and the closing of trade barriers to foreigners—had also been an abysmal failure, especially in Africa and Latin America, leading to corruption and endemic poverty.

But then there was that strange outlier, East Asia. The East Asian “Tigers,” inspired by the postwar champion of managed economies, Japan, had dared to tinker with market forces like demiurges playing with elemental fire, and they had largely succeeded. Around that time, Masaki Shiratori, Japan’s executive director at the World Bank, lobbied passionately for a study of East Asia’s unusual success, its unique and savvy combination of deft government promotion of markets.

The World Bank came up with one—350 pages long—that hesitantly concluded that “market-friendly state intervention” might sometimes work. But it was so heavily hedged that it had little impact. Washington didn’t want to risk turning countries like India into government-supported export giants with East Asian-style policies, especially when U.S. markets were already seen as being under assault and Clinton was preaching “jobs, jobs, jobs.” And U.S. policymakers didn’t want countries like Russia to find excuses for only half-reforming their way out of command economics.

Mainstream economists rolled out their big guns against the idea that East Asia had a viable alternative. In a 1994 Foreign Affairs article, “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle,” Paul Krugman argued that pouring all that capital into industry at home was only going to yield “diminishing returns” and compared the Asians to the Soviet Union, saying that people forget “how impressive and terrifying the Soviet empire’s economic performance once seemed.” Krugman cited in particular the work of economists Alwyn Young and Lawrence Lau, who argued that East Asia’s “total factor productivity” numbers showed East Asian economic growth was entirely based on “inputs” such as rapid labor force increases, not on improved efficiency. It was merely “economic growth on steroids,” Young told me in an interview for Institutional Investor magazine in 1993. “You look impressive, but inside you’re rotting.”

Young and others pointed to Japan’s slow-growth period as evidence of this, but he and other economists failed to take into account the ultra-long time frame of the East Asian model—the fact that these countries were laying the institutional groundwork for later improvements in productivity and efficiency. And all the while neoliberalism was being slowly undermined by the departure of U.S. capital for foreign shores, along with cheaper labor. What the Clintonites and their advocates failed to see was that “[a]s capital becomes internationally mobile, its owners and managers have less interest in making long-term investments in any specific national economy—including their home base,” Robert Wade—then a renegade World Bank economist—argued at the time.

Wade and others were, of course, ignored. The historical tide of neoliberalism was too powerful, and the Japanese too meek about asserting their views. Japan, as ever, was bad about “forming universal theories from the economic success of Japan,” Naohiro Amaya, one of the country’s legendary bureaucrats, told me in 1992 when I lived there. It was a culture of pragmatism; the Japanese had no Keynes or Marx of their own. And frankly, few bureaucracies were as savvy as those of the East Asians, with their agile technocratic class and Confucian tradition of service. India, for example, which had grown up with Nehru socialism, had suffered for decades under the “license raj,” which involved a bureaucratic tangle every time someone wanted to start a business.

Yet much of this long-entrenched economic “wisdom” is now cracking—much like the melting glaciers that neoliberal capitalism, during its rampage across the planet, has helped to promote. As Cherif and Hasanov write in “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named”: “Our summary of 50 years of development showed that only a few countries made it from relative or absolute poverty to advanced economy status,” giving rise to the idea that government can’t make much of a difference. East Asia proved that it could, but “until recently, the experiences of the Asian miracles have been mostly considered as ‘accidents’ that cannot and should not be emulated, at least from the point of view of standard development economics.”

That is no longer the case. For better or worse, a new global economic consensus is being born, if rather painfully. As John Maynard Keynes wrote in the preface to The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money: “The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones…”