#I studied comparative religion at an institution of higher learning

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

🚨 Terrible Pun Warning 🚨

Q: How do you know that the United States of America is an xtian country?

A: Easy! Anybody can tell you that American automobile infrastructure is proof of the in car nation.

#religion#cw usa#cw car culture#cw christianity#cw christian nationalism#theology humor#automobile dependency#I studied comparative religion at an institution of higher learning#and this is the result#pun ish meant#Now the sticklers in the audience will point out that US culture is deeply heterodox by xtian theological standards#if not outright heretical in its embrace of capitalism and consumerism#So one could argue that’s it’s less of an xtian country#and more of a car go cult#If you read this far you knew what you were getting into#That’s all folks!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

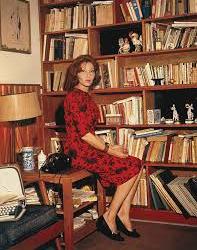

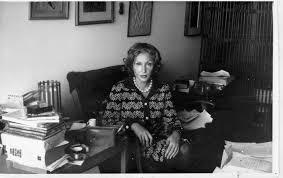

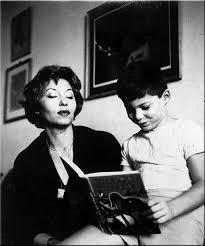

Clarice Lispector Birth Chart Analysis (PT 1)

Before I looked at her chart, she struck me as heavily Ketuvian based on the content of her writing.

♌ This birth time would give Lispector a Magha rising, which is fitting given her titles like “Madame of the Void” and “Queen of Brazilian Literature." She married a wealthy diplomat and traveled the world (Aquarius 7th house perhaps?), living like royalty compared to most Brazilians at the time. The Magha themes of ancestry and lineage appear frequently in her work. Claire Nakti associates Magha with the Abrahamic religions and Lispector was Jewish by birth.

♃ Lispector was also famous for her beauty, perhaps due to Jupiter in Purva Phalguni, ruled by Venus, on her ascendant. (This could also explain her lavish lifestyle after marriage.)

♄ Saturn in the second house: Lispector was a refugee to Brazil from Ukraine, sailing to Brazil from Romania at one year old. Her family suffered significantly in the pogroms that followed the dissolution of the Russian Empire. The family suffered financially for many years after their immigration. She expressed frequently that she never felt a sense of belonging to any land, which feels very Saturnian.

♍/♎ Saturn in Virgo/Rahu in Libra in the 3rd: At age 12, Lispector gained admission to the most prestigious secondary school in her state in Brazil. Around this time she decided to become a writer. She studied Law (Saturn) at one of the most prestigious institutions of higher learning in the country.

♒ 7th ruler is Saturn: Her husband was a fellow classmate at law school.

♏ Chart ruler in 4th (Jyestha): Her life and writing scream Jyestha and it makes sense her lagna lord would be Scorpio based on her dark aesthetic and literary preoccupation with the cosmic void and the supernatural. Especially in the fourth house, it makes sense she’s come to represent the “Dark Feminine,” especially as her Sun is her AK planet.

☿️ Mercury in Anuradha (In 4th): Mercury is a super interesting nak to look at for writers, and Anuradha has scorpionic themes of depth, death, and the occult but with Saturn’s refinement.

☾ Moon in Mula (as DK) in 5th: The fifth house can represent creative gifts, and Mula nak themes are reflected strongly in her work: horror, the abnormal, chaos, seeking truth, looking to the root of things. Her writing style is very stripped back and deep. Her husband provided for her financially (possibly bc moon = nourishment) and she bore two sons.

☾ 12th house (Cancer) ruler in 5th: This could contribute to the dreamlike quality of her writing as well.

♀️ Venus and Mars in the 6th house is interesting because she wrote for work and routinely with both signs in Capricorn. Her writing would her legacy, considered of the highest quality, and lasted the test of time, in fact interest in her work has increased as time passes. (If that isn’t Capricon idk what is lol: Uttara Ashada “Later Victorious")

With planets in Mula, Shravana, Magha, Anuradha, Uttara Ashada, and Jyestha, and Pisces 8th house, I definitely think she was pyschic.

♈ Ketu in 9th: Could definitely explain her spiritual inclinations, esp with Ashwini’s focus on the unmanifest and the self.

Will look into the padas and moon chart another day! I also want to compare her chart with that of Eve Babitz as they both received serious burns from smoking cigarettes. 🌺

#vedic astrology#vedic astro notes#sidereal astrology#horoscope#clarice lispector#woman writers#brazil#dark feminine

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Book Review

Ratner’s Star by Don DeLillo

Somebody once told me that Don DeLillo’s Ratner’s Star is an inscrutable novel, impossible to interpret and impossible to understand. I took this as a challenge. After all, I’ve read supposedly impossible books like Ulysses, Finnegans Wake, and Gravity’s Rainbow. I’ve plowed through The White Goddess by Robert Graves and managed to make some sense out of Heidegger’s Being and Time and Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. The trick to understanding these books is knowing what to read for, where to look for it, and how to separate the main ideas from the noise and irrelevant details. And especially be careful when listening to others who have read these books and obviously didn’t understand them, but felt a need to explain them anyways. Whether I am guilty of this or not will be left to others to decide. My take on Ratner’s Star is that it is a picaresque-style novel and that Billy Twillig is one of the least important characters in the narrative.

Billy Twillig is a prodigal scholar. At the age of fourteen, he wins the Nobel Prize for mathematics due to his work with zorgs, a branch that only six people in the world are able to understand. Billy gets taken to a secretly-located institution to work on an assignment to decode a message received from aliens in outer space. Billy, unsurprisingly, acts like a teenager despite his advanced skills, an aspect of him that never gets fully explored by DeLillo in the narrative. He is equal parts cheeky and horny, taking every chance he can get to ask questions of the adults that deprecate them but never himself. The institute itself seems, at times, more like a lunatic asylum than it does a research facility. DeLillo says that this first half of the book was modeled on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I didn’t pick up on that by myself, but after having learned that, it fits more or less.

The other scientists are eccentric, to say the least. After arriving, Billy encounters some of them in an artificial, man-made Elysian field. One of the first he meets is Cyril, a scholar working with a team of linguists to define the word “science”. This task is harder than first imagined as they can not agree to where the parameters of the definition lie. Some of them argue that primitive magic, as described by Frazer in The Golden Bough, should be considered part of the definition because those folk magic and customs were devised for the same reasons that science was invented; the purpose was to understand nature and the universe and to exert some sort of control over it for the benefit of humanity. Modern science is nothing more than a precise and more finely tuned form of magic.

Throughout the course of the discussion, Billy is introduced to some female scientists who study the natural elements and he think of them as nothing less than Pagan deities. After assigning one of them the characteristics of a water goddess, he spies on her while she is bathing only to be chastised by her when she catches him. This scene alludes to Artemis, the Greek goddess of chastity, who caught Actaeon spying on her in the woods. This Paganism is all significant because it introduces a theme that pervades throughout the entire book, the primitivism of science as it encounters the frontiers of human knowledge and also the disconnection between language and reality. Since thought, science, and mathematics are all products of language, all of which are tools used to comprehend what we encounter as real, nothing can ever be known in full. The signifier can never be equal to the signified. In the context of comparing Pagan magic and its transition into science, the same questions are foundations for both endeavors with science introducing higher levels of accuracy but also increasing levels of complexity to the point where finding defnite answers may be impossible. Where magic and religion have finality, closure, and the illusion of certainty, science offers only open ended questions that never stop expanding.

Billy Twillig proceeds to meet other strange, eccentric scientists in a similar vein. One is an Indian woman from the untouchable class who studies animal communication and how they are able to think without language. Again, this is another commentary on language and the nature of thought. How can we even use language to comprehend thought that manifests without language? Considering the woman is untouchable, Billy wants to know what would happen if he touches her leg. “Nothing, obviously,” is the woman’s answer, rendering the concept of “untouchable” an empty set. There are also two sleazy gangster types who speak an odd mishmash of languages and left me wondering if they were actually space aliens. They represent the Honduran Syndicate and wish to recruit Billy to manipulate international financial markets. Yet another doctor, claiming to be a lapsed Gypsy, whatever that means, and wants to get rich by turning Billy into a super-computer by inserting brain-accelerating electrodes into his head. Also in a secret ceremony, Billy meets the old scientist Ratner who lent his name to Ratner’s Star, the part of the galaxy where the coded message came from. Ratner was an astronomer who abandoned science as a career and embraced the mysticism of Hasidic Judaism when he realized that science can not answer the question of what happens when we die. On his deathbed during the ceremony, Ratner tells Billy his life story and then whispers the ultimate secret of life into Billy’s ear, but the secret is the most mundane statement you could possibly imagine. But the symbolism of the old passing traditional knowledge down to the young is what is most important here. It also exemplifies how mysticism is a closed system of information whereas science is, by contrast, an open system.

Those are some of the minor characters from the first half. One of the more important characters is Billy’s father who doesn’t contribute too much to the overall narrative, but does introduce one important theme. He takes Billy down into the subways of New York City, where it is dark and there is a danger of getting hit by a train, to teach him that the basis of life is fear. In this instance Billy directly experiences the fear of death since getting hit by a train in the dark would inevitably result in death. Indirectly, DeLillo is pointing out how the fear of death leads to magic, mysticism, and religious thought. Through Billy’s father, DeLillo also points out that fear can lead people to live lives of absurdity since the father owns a guard dog that no one is scared of except for young Billy, develops a neurosis over a pile of dirty dishes in the sink, walks the streets prepared for brawls that never happen, and almost assaults an elderly and frail Chinese man who he mistakes for a mugger. The father also makes the mistake of admiring a tall and talented basketball player for being the kind of son he wishes he had even though the athlete makes a dumb decision that ruins his career while Billy goes on to be a success. The father even considers murdering Billy out of fear of how the boy, unusually small for his age and full of unusual ideas, will make the family look. The father’s fear of death does not lead him to make wise or sensible decisions about life which may be DeLillo’s critique of religion and the possibility of science as an alternative.

Then there is Endor, the mathematician who was assigned to crack the code from Ratner’s Star before Billy came along. Endor lost his patience, moved to a remote location, and spent the rest of his life living in a hole, eating grubs, and digging a tunnel. This latter project parallels the scientific task in that research involves digging oneself deeper and deeper into a hole that eventually will lead to some truth. Endor, as we learn later in the book, actually solved the code before seemingly going crazy. After doing so, he realized that the tunnel digging involved in solving the puzzle created a tunnel leading nowhere as the answer to the original problem ultimately led to more questions rather than one answer. So Endor quit and began digging a tunnel that literally had no purpose and led nowhere. But it did mean something symbolically. The entire book is full of tunnels and hallways all joining up with enclosed rooms, caverns, cells, and enclosures. These may or may not allude to the kabbalah diagram that Ratner describes to Billy as he dies.

In fact, there is one astrophysicist who explains to Billy that black holes are entrances to tunnels and anything that enters them re-emerges in another part of the galaxy. Every star corresponds to a black hole. I am not atronomically literate enough to know if this is true, but it serves a purpose in the book. The man who explains this to Billy is Orang Mohole, the man who discovered moholes, or pockets of hidden space that permeate the cosmos. This character is significant because his moholes play a major part in explaining where the message from Ratner’s Star came from and why they took so long to reach Earth. Mohole is also a pervert and a bipolar psychotic who enjoys inventing sex toys as if he is preoccupied with penetrating into the secret spaces of women’s bodies. He also sometimes goes crazy and shoots people at random. It is possible that he is the man having a firefight with the police when the riddle of the coded message is solved. As if he entered a narrative black hole and re-emerged in another part of the book, kind of like the Aboriginal shaman with white hair and one eye.

If the first half of the book is meant to portray the different aspects of science, two things are certain: one is that teamwork is necessary for scientific research; none of these people are working on their own, but rather they are each deeply involved in one complex part of a larger scientific problem. The other deduction, and the other side of that teamwork, is that individual scientists are lonely, eccentric, and socially isolated people who often risk their sanity for the cause of discovering higher truths. The fact that science, as an open system of information, can never be complete, drives some practitioners into mental territories that suggest locations on the autism spectrum. And all these characters in the first half do represent aspects of science. Ratner represents its mystical element. The Honduran Syndicate represent the exploitation of science for technocratic power, the lapsed Gypsy is the commercialization of science, and Cyril shows how science, in its inability to finally and completely explain the nature of existence, is always at the frontier of human knowledge, while Endor portrays the problematic side of science in that it can never fully explain nature the way religion can.

By the start of the second half of the book, one thing becomes clear; Billy Twillig’s purpose is to provide a structure to the novel and a thread that holds the whole mess together. He is like Virgil leading Dante through Hell in The Divine Comedy, only we, the readers, are Dante and Billy does not tell the stories of the lost souls we encounter, rather he lets them speak for themselves.

In this second half, Billy continues to serve his narrative function as the main character but not the most important character since that role gets filled by Softly, a drug and sex addicted dwarf with a deformed and asymmetrical body. He takes Billy into some underground tunnels to a cavern compound below the institute where they have been working. Softly has assembled a team of scientists to construct a language based purely on logic and mathematics that will be utilizable as a tool so that any intelligent living being on Earth or in outer space can communicate with perfect efficiency, without any ambiguities or misunderstandings. Wasn’t Esperanto meant to do something similar? Softly explains to Billy that he originally brought him to the institute for this secret project. When Billy asks why he had to spend so much time working on deciphering the message from Ratner’s Star even though no one actually cared about it, Softly explains that that project was nothing but preparation for this more important task. In terms of structure, this is the author’s way of telling us that the first half of the novel introduces all the themes of the book and the second half puts them into play. The metanarrative is actually encapsulated in the narrative. Is this Chomsky’s recursion at a semantic level? Remember how most of Moby Dick was descriptions of whales and the esoteric language associated with the practice of whaling? The layman needs to learn all of that so they don’t get lost in technical descriptiveness when the action of the novel begins. Well, that worked for Herman Melville, but not so much for Don DeLillo. Ratner’s Star reaches a narrative plateau rather than a narrative peak. While Billy isolates himself, refusing to do any work, the others set about the task of creating the language and, by God, they create it. Oh yeah, and Billy cracks the code of Ratner’s Star too. No big surprises or conventional conflict resolutions.

But like the first half of the book, the second half is really all about the characters. Where previously characters were meant to represent different aspects of the scientific endeavor, now the characters in the project are brought into three-dimensionality for an exploration of their individual motives. One man works on this project to advance his career and status in the scientific community, one woman uses it as a means of fueling her own philosophical theories about language. A third is engaged in the project to reconcile his identity as a Chinese-American man, being unable to fit completely into either category of “Chinese” or “American”; He latter concludes that language barriers prevent him from being wholly one or the other. The most poignant portrayals of the inner lives of the characters come from Softly and Jean Venable, an author he hires to write a book about the project. Jean is actually a talentless writer with a turbulent psyche and an unfulfilling social life, possibly even suffering from mental illness. Softly chose her because he wants the story to be told to the general public by someone who doesn’t understand science; in other words, he seeks fame through mass popularity while also seeking prominence in intellectual circles through his real work. Actually, though, he is more preoccupied with using Jean for sex to overcompensate for his physical malformations. As we get to know Softly more, we learn that he is motivated by insecurity and self-loathing. He refuses to look into mirrors out of disgust and tries to conquer the world to make up for his inadequacy.

Otherwise, the scientific themes in the second half are really just expansions on the themes introduced in the first half. One theme that deserves some attention here is that of mathematics. A lot of readers are put off to this book because of it, but you don’t actually need to do any math to follow what is going on since DeLillo limits his exploration to theoretical mathematics rather than applied mathematics. What I get from this book is the need for math to remain an open system of communication so that mathematics can expand eternally and adapt to scientific changes as more knowledge accumulates. The paradox is that while pure mathematics deal in absolute truths, applied math needs to be constantly readjusted to function since science is a process of never-ending self-correction. Pure mathematics can only be self-referential thereby posing the question of whether they are pure or not when we utilize them to explain scientific objectivity. Or do we, in reverse, adjust our perceptions of objectivity to correspond with the ultimate truths of pure mathematics? Of course, this is postmodernism so there can ultimately be no solution to these problems. Is postmodernism meant to be an admission that there are limitations to our intellectual abilities or is it merely just a cop out? When reading Wittgenstein I think it’s the former, when reading Derrida I think it’s the latter.

In the end, Ratner’s Star certainly has its flaws. The anecdotes about Billy’s childhood don’t lend a whole lot to the overall story and I think some of them should have been written to completion or else left out entirely. I guess in postmodern novels, not everything makes sense because the world is just that way. Pynchon can get away with this, but here DeLillo appears to have made some poor editorial choices. Billy could have been developed as a character more too. I know he is more of a narrative device than a real character, but this still leaves a huge void in the center of the novel that makes it underwritten which is strange considering how overwritten everything else in this book is. Speaking of Pynchon, DeLillo intended this to be an homage to him. But instead of reading like an homage, it comes off as derivative and unoriginal. There are secret plots, paranoia, underground tunnels, secret societies, communications theory, arcane technological jargon, loose plot threads, sexual perversion, non sequiturs, narrative derailments, and even a couple songs stuck in at random places. It’s as if DeLillo took every element from Pynchon’s first three novels and repurposed them for his own novel. It is often too close to Pynchon to be good, but isn’t that also postmodernism? There is never anything new, only copies of copies of copies? In DeLillo’s case it doesn’t quite work. But this novel is far from being a failure. The well-drawn characters are unforgettable and full of depth, so much so that within a sentence or two they feel complete and fully realized. This is a trick few authors can master.

Would Ratner’s Star stand on its own for a reader who had never heard of Pynchon? I think it would. There is enough brilliance here to be independently evaluated without the overbearing shadow of the great and mysterious Ruggles. DeLillo is full of his own ideas and this is a unique exploration of language, logic, science, and mathematics that could never be recreated by anyone else. DeLillo’s later novels were definitely better, and Ratner’s Star is not for the casual reader, but for those who make the effort, and especially those who have an eagle’s eye for fine details, reading this book is a rich and rewarding experience.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know where I got that quote from? A review of Dominion by Tom Holland. Where he, an atheist, argues that it is Christianity that gives us our concept of human rights. Where he also notes that the first person to call for the abolition of slavery was a Christian, Gregory of Nyssa.

While I admittedly haven't read it, I have read God's Philosophers (UK title)/The Genesis of Science (US title) arguing that Christianity not only did not hinder, but played a significant role in founding science as we know it. While the author is a liberal Catholic, he's been praised by people who aren't - it was shortlisted for Royal Society Science Book Prize in 2010 and the British Society for the History of Science Dingle Prize in 2011, and historian of science Edward Grant has this to say: “Hannam has written a splendid book and fully supported his claim that the Middle Ages laid the foundations of modern science. He has admirably met another of his goals, namely that of acquainting a large non-academic audience about the way science and various aspects of natural philosophy functioned in medieval society and laid the foundation for modern science. Readers ... will learn about these important matters in the history of science against the broad background of the life and times of medieval and early modern societies.”

May I recommend History for Atheists to you? You are exactly the kind of fevered, historically illiterate anti-theist militant it was written to combat.

Oh, and by the way you still haven't responded to my point about the evidence for Jesus compared to similar figures. I'll be honest: you are the equivalent of someone who thinks the moon landing never happened. I will again call in Bart Ehrman (who, I will remind you, is an ex-Evangelical atheist who thinks Jesus was a failed doomsday prophet and the Bible is unreliable):

"Few of these mythicists are actually scholars trained in ancient history, religion, biblical studies or any cognate field, let alone in the ancient languages generally thought to matter for those who want to say something with any degree of authority about a Jewish teacher who (allegedly) lived in first-century Palestine. There are a couple of exceptions: of the hundreds -- thousands? -- of mythicists, two (to my knowledge) actually have Ph.D. credentials in relevant fields of study. But even taking these into account, there is not a single mythicist who teaches New Testament [Studies] or Early Christianity or even Classics at any accredited institution of higher learning in the Western world. And it is no wonder why. These views are so extreme and so unconvincing to 99.99 percent of the real experts that anyone holding them is as likely to get a teaching job in an established department of religion as a six-day creationist is likely to land on in a bona fide department of biology."

And while I'm being honest with you, I only responded to your initial post because I wanted to have a go at shredding your absurd and ignorant beliefs about the historical Jesus. So my interaction with you is not something you deserve.

Respond to my post comparing evidence for Jesus with evidence for Athronges, John the Baptist, the Samaritan Prophet, etc. in 24 hours from now (3:50 PM in the UK, 8:50 AM on the East Coast of the US) or I'm blocking you.

By the way @gaykarstaagforever, I had a little look at your blog and it reminded me of this quote by Tim O'Neill, amateur historian* and history blogger who got fed up of his fellow atheists pushing outdated pseudohistory.

"One of the things that often startles me about the way most anti-theist activists speak or write about Christianity is their almost visceral emotionalism. I happen to be a person raised a Christian who abandoned any faith pretty readily in my late teens and who lives in a highly secular country in a largely post-Christian society. On occasion certain Christians, particularly some prelates or politicians, will annoy me with a particularly stupid statement or action, but on the whole I can regard Christianity as I regard any faith – something that other people do that interests me largely as a historical phenomenon.

Many of those who are the focus of this blog, however, cannot seem to get Christianity out of their systems. A large number of them are, like me, ex-Christians, but ones who seem still mentally entangled in their former faith. Never able to emerge from a kind of juvenile angry apostasy, they seem impelled to strike out at it at every turn. They have to constantly remind others – and, it seems, themselves – of its manifest stupidity and wickedness.

This is why many of them cannot fathom how I can debunk myths about Christian history without also somehow being a kind of “Christian apologist” or “crypto-Christian”. It is why noting that the Church actually did not teach the earth was flat, that Christians did not burn down the Great Library of Alexandria or that the Galileo Affair was not some black-and-white moral parable of “science versus religion” elicits frantic efforts on the part of some to salvage something of these stories so that Christianity does not get off scot-free. It is also why the Jesus Myth thesis seems so convincing to many of these anti-Christian zealots while it appears clumsy and contrived to pretty much everyone else."

*He has an advanced degree in history, but it's not his job.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Haha okay. This is what I ended up keeping of my education, skills, and aptitudes for Alucard over his lifetime. The first paragraph is true and documented information as to the education of the irl Vlad Dracula.

No institutional education to speak of. He was tutored privately up until he was about 11. He was taught to be literate and multilingual. Historically, he spoke Bulgarian (most likely his mother tongue), Slavonic, what is now Romanian, Magyar, Turkish, German, Latin, and Greek. He would have learned basic math, how to ride a horse, and some basic information about foreign affairs, history, and religion. When he lived with the Turks he most likely taught geometry, chemistry, algebra, military history, how to fight in general (Hirano depicts him with a broadsword, but in reality he favored the kilij, a curved scimitar he learned to use with the Turks) and literature. Ottoman education was considered a higher standard of education compared to European schools.

After he turned, he wanted to learn about the nature of his new existence, and at the turn of the 16th century he picked up alchemical studies from his exposure to it via the Turks, which was basically the occult without being wholly rejected by the Abrahamic faiths. This opened the door to philosophy and further studies in chemistry. This was the gateway to him expand on his lesser intuitive capacity, as it allowed practical application theories (chemistry) to more conceptual theories (philosophy). He came to favor the works of Hermes Trismegistus, and found the concept of the Philosopher’s Stone an interesting concept. By the time his curiosity for alchemy had been sated, he’d decidedly settled on his own theory that the true nature of the Philosopher’s Stone was blood, and by “eating his own wings”--a metaphor for giving up his humanity and pursuit of divinity– he had incidentally transmuted his own blood into the Philospher’s Stone.

Conceptual studies weren’t all consuming; he still favored sensory (read as “practical”) skills. He expanded on his knowledge of arms and armory by learning to forge iron. Eventually he learned leatherwork and woodwork to supplement the creation of iron works. While these were means of survival or earning a living for humans, they were strictly hobbies for him, and he put them down to pick up new skills as his interests waxed and waned. He kept up with political affairs, domestic and foreign, and routinely brought in guests and tutors to keep his knowledge of the changing times up to date. When he wasn’t killing enemies of his homeland and feeding on them, he used the wealth he’d managed to abscond with and his up-to-date knowledge of the happenings of Europe to invest in commodities, political figures, and land.

Over time, he became less and less invested in the workings of the human world, and when he began keeping more to himself he picked up arts for the sake of learning something new. His favorite was architectural studies and design, and had a handful of properties built to his designs so he could move when there was cause for concern that he may be suspected for mass deaths in the local villages and encampments. Portraiture, landscapes, and architecture were subjects of drawing and painting, but when he reached a point of considerable technical skill he would drop the hobby for decades at a time. He learned to play a few instruments, including viola (and later on violin), harpsichord, and piano.

He consistently obtained books and hired the occasional tutor to teach him the remaining Romance languages and some others, as well as advancements in science, mathematics, philosophy, literature, warfare, and theology. This inevitably led to learning about the progression of Western Europe, and by the 19th century England was a significant place of secular development. Having learned Middle English long ago, he began learning modern English and English history with the goal of moving to England to expand his palette and his experiences of the human world.

He kept up with military developments throughout his entire life, and technology in general, and had long since begun learning how to use and maintain firearms. With the militarization of the Hellsing Organization in the 20th century, he got firsthand experience on modern weaponry, moreso under Arthur’s observance as opposed to Abraham who kept him on a very short leash. Despite sleeping through the 70’s and 80’s, he was quick on the uptake when Integra brought him back to the world. Integra allowed him to learn to operate vehicles, including cars, but particularly military aircraft as he made an excellent test pilot with effective indestructibility. He learned how to use phones and pagers, and developed a simplistic, if dismissive, understanding of how to operate a computer though he had little to no practical application of that understanding up until the end of the war in 1999.

Post series in the 2030’s he continued to bring himself up to speed on socio political affairs, technology, literature, sciences, and other practical matters.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

capitalism

context: why does it make me cringe? why does sales make me cringe?

why did I feel for a while that I don’t want to get caught up in the career ladder?

why do I judge people who chase money or fame?

what should truly motivate us at work

In a perfect world, when it came to choosing an occupation, we would have only two priorities in mind:

– to find a job that we enjoyed

– to find a job that paid us enough to cover reasonable material needs

But in order to think so freely, we would have to be emotionally balanced in a way that few of us are. In reality, when it comes to choosing an occupation, we tend to be haunted by three additional priorities. We need:

– to find a job that will pay not just enough to cover reasonable material expenses but a lot more besides, enough to impress other people – even other people we don’t like very much.

– we crave to find a job that will allow us not to be at the mercy of other people, whom we may deep down fear and distrust.

– and we hope for a job that will make us well known, esteemed, honoured and perhaps famous, so that we will never again have to feel small or neglected.

reforming capitalism

The system we know as Capitalism is both wondrously productive and hugely problematic. On the downside, capitalism promotes excessive inequality; it valorises immediate returns over long-term benefits; it addicts us to unnecessary products and it encourages excessive consumption of the world’s resources with potentially disastrous consequences – and that’s just a start. We are now deeply familiar with what can go wrong with Capitalism. But that is no reason to stop dreaming about some of the ways in which Capitalism could one day operate in a Utopian future.

What we want to see is the rise of other – equally important – figures that report on a regular basis on elements of psychological and sociological life and which could form part of the consciousness of thoughtful and serious people. When we measure things – and give the figures a regular public airing – we start the long process of collectively doing something about them.

The man is indeed employed, but in truth, he belongs to a large subsection of those in work we might term the ‘misemployed’. His labour is generating capital, but it is making no contribution to human welfare and flourishing. He is joined in the misemployment ranks by people who make cigarettes, addictive but sterile television shows, badly designed condos, ill-fitting and shoddy clothes, deceptive advertisements, artery-clogging biscuits and highly-sugared drinks (however delicious).

We intuitively recognise it when we think of work as ‘just a job’; when we sense that far too much of our time, effort and intelligence is spent on meetings that resolve little, on chivying people to sign up for products that – in our heart of hearts we don’t admire.

Fortunately, there are real solutions to bringing down the rate of misemployment. The trick isn’t just to stimulate demand per se, the trick is to stimulate the right demand: to excite people to buy the constituents of true satisfaction, and therefore to give individuals and businesses a chance to direct their labour, and make profits, in meaningful areas of the economy.

This is precisely what needs to be changed – and urgently. Society should do a systematic deal with capitalists: it should give them the honour and love they so badly crave in exchange for treating their workers as human beings, not abusing customers and properly looking after the planet. A standard test should be drawn up to measure the societal good generated by companies (many such schemes already exist in nascent form), on the basis of which capitalists should then be given extraordinarily prestigious titles by their nations in ceremonies with the grandeur and thrill of film premieres or sporting finales.

There’s no shortage: we need help in forming cohesive, interesting communities. We need help in bringing up children. We need help in calming down at key moments (the cost of our high anxiety and rage is appalling in aggregate). We require immense assistance in discovering our real talents in the workplace and understanding where we can best deploy them (a service in this area would matter a great deal more to us than pizza delivery). We have unfulfilled aesthetic desires. Elegant town centres, charming high streets and sweet villages are in desperately short supply and are therefore absurdly expensive – just as, prior to Henry Ford, cars existed but were very rare and only for the very rich.

But we know the direction we need to head to: we need the drive and inventiveness of Capitalism to tackle the higher, deeper problems of life. This will offer an exit from the failings and misery that attend Capitalism today. In a nutshell, the problem is that we waste resources on unimportant things. And we are wasteful, ultimately, because we lack self-knowledge, because we are using consumption merely to divert or quieten anxieties or in a vain search for status and belonging.

If we could just address our deeper needs more directly, our materialism would be refined and restrained, our work would be more meaningful and our profits would be more honourable. That’s the ideal future of Capitalism.

In the Utopia, businesses would of course have to be profitable. But the success of a business would primarily be assessed in terms of its contribution to the collective good.

On changing the world

the only way to bring about real change is to act through competing institutions. Revolutions in consciousness cannot be made lasting and effective until legions of people start to work together in concert for a common aim and, rather than relying on the intermittent pronouncements of mountain-top prophets, begin the unglamorous and deeply boring task of wrestling with issues of law, money, long-term mass communication, advocacy and administration.

Our collective ideal of the free thinker is that of someone living beyond the confines of any system, disdainful of ‘boring things’, cut off from practical affairs and privately perhaps rather proud of being unable even to read a balance sheet. It’s a fatally romantic recipe for keeping the status quo unchanged.

We have to make what we already know very well more effective out there. The urgent question is how to ally the very many good ideas which currently slumber in the recesses of intellectual life with proper organisational tools that actually stand a chance of giving them real impact in the world. From a completely secular starting point, it can be worth studying religions to learn how to alter behaviour.

This is what religions have, for their part, excelled at doing. They’ve realised that if you put down an important idea on paper in somewhat pedestrian prose, it won’t have any lasting or mass impact. They’ve therefore, over their history, engaged the most skilled artists to wrap their ideas in the coating of beauty. They have asked Bach and Mozart to put the ideas to music, they have asked Titian and Botticelli to give the ideas a visual form, they’ve asked the best fashion designers to make nice looking clothes and they’ve asked the best architects to design the most impressive and moving buildings to give the ideas heft and permanence.

We should use the history of religion to inform us about the role of repetition, ritual and beauty in the name of changing how things are.

There is a great deal of large-scale ambition in the world, but all the largest corporate entities are focused on servicing basic needs: the mechanics of communication, inexpensive things to eat, energy so we can move about. While our higher needs – for love, beauty, wisdom – have no comparable provision. The drive to grandeur is missing just where we need it most.

Good business

So, inevitably, businesses will evolve to profit from their wishes. Capitalism has not traditionally been interested in whether these are sensible, admirable or worthy desires. Its aim is neutral: to make money from supplying whatever people happen to be willing to pay for.

Philosophy, by contrast, has long recognised a crucial distinction between desires and needs:

A desire is whatever you feel you want at the moment.

A need is for something that serves your long-term well being.

And it’s our needs that are required for a satisfying, fulfilled life (which Plato, Aristotle and others call a life marked by eudaimonia).

Capitalism goes wrong when it exploits this cognitive flaw: large numbers of businesses sell us stuff that we desire but which (in all honesty) we don’t need. On longer, calmer reflection we’d realise those things don’t actually help us to live well.

Sadly, it’s easier to generate profits from desires than from needs. You can make much more money selling bad ice cream than by marketing Plato’s dialogues.

In a utopia, good businesses should be defined not simply by whether they are profitable or not; but by what they make their profit from. Only businesses that satisfy true needs are moral.

Good capitalism requires that we address two, core educational needs. Getting us to focus on what we really need, what the real challenges in our lives are. And getting us to focus on the value of particular goods in relation to our needs: that is, how do these particular purchases help with eudaimonia?

So, in search of a better economy, we should direct our attention not simply to shopping centres and financial institutions, but to schools and universities and the media. The shape that an economy has ultimately reflects the educated insights of its consumers. When people say they hate consumerism, what they often mean is that they are dismayed at peoples’ preferences. The fault, then, lies not so much with consumption as with the preferences. Education transforms preferences not by making us do what someone else tells us. But by giving us the capacities and skills to understand more clearly what we genuinely do want and what sort of goods and services will best help us.

tbc

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amos Jackson III, MDiv ′23

“Healing matters to the oppressed, the disenfranchised, the poor, and the hungry. People can get justice, they can get policies and even resources, but it's the healing that actually helps them to move forward. If an individual gets justice but still carries trauma, are they really obtaining true justice?”

Amos is a first-year master of divinity degree candidate at Harvard Divinity School.

Politics and the Church

I was named after one of the minor prophets in the Bible as well as my father and my grandfather, who was named after his uncle. I'm the fourth generation of my name, but the third in my immediate family. I'm originally from West Palm Beach, Florida, but currently based in the Washington D.C. area. I’ve been here since I started college at Howard University, where I graduated from in 2019 as a double major in political science and African American studies.

I grew up in a non-denominational church and even went to pre-K there, but when I was about 13 we moved to a Baptist church not too far from our house, and that's where I really begun my personal faith journey. Growing up, no matter what happened on a Saturday night, we were going to church on Sunday at 7:45 am in the morning.

Interestingly, the church was my introduction to politics. I remember that the first time I met a politician was while he was at church campaigning, and I can recall asking myself why politicians frequented the Black church during election season. Because of the influence of my upbringing, and watching how religion played a big role in social movements, I've always had an interest in the intersection of religion and politics. I wanted to know why this intersection was so important to politicians. “Why now? Why here? What purpose does it serve?”

Seeking the answers to these questions is a big part of the reason I’m now at HDS. I still attend church every Sunday (now virtually) and lead a prayer call for my church every Sunday at 6 pm while also being devoted to the various social justice causes of my church, because I believe that faith requires me to go out of the four walls of the church building and be involved in the community.

Articulating the Value of HBCUs

I initially did not have the desire to attend an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) before I committed to Howard University. It wasn't until I got there that I understood the intellectual and cultural richness of the HBCU experience. The biggest benefit of all was getting my education from an African diasporic lens of learning. In comparison to other schools that might have been providing a Eurocentric or westernized form of education, I was learning about psychology, political science, and other spheres in a way that addressed them not just generally, but also their specific interactions with and effects on Black people.

Having the opportunity to be in a space where I felt comfortable and could unapologetically be myself was such a blessing. I also had the honor of being student body president and becoming an ambassador for my HBCU. HBCUs make up only 3 percent of higher education but produce 50 percent of Black lawyers and doctors. Some of the most exceptional Black leaders in this country—such as Martin Luther King, Thurgood Marshall, Ella Baker, John Lewis, Kamala Harris and so many others—were shaped and highly influenced by their HBCU education, and being able to stand on their shoulders as an HBCU alum is a high honor.

Working on a Historic National Campaign

2018 was a very important year for me. I met the then Senator Kamala Harris at an event in D.C., and I shared with her about the disappointment I had felt the night when the 2016 election results were released. I told her how I had believed my opportunities were crushed in D.C., but the silver lining in it all had been that fact that she was elected that very same night to the United States Senate. And there I was, a year-and-a-half later, asking if I could work for her. She offered me the opportunity, and that summer I started interning in her office. Just days after graduation, I was working as a national political coordinator for her presidential campaign in New Hampshire and Nevada. Fast forward to this past September, when I joined the Biden-Harris campaign as Senator Harris’s deputy political director. These opportunities have been endless, and I attribute this to my HBCU education providing me a pathway to work for an alumna of my institution. I do, in a way, see politics as a ministry, and I am grateful that I can now answer the questions I had as a child about why religion was significant for politics. I am seeing firsthand the extent to which society is driven by their social, religious, and moral views, and I'm just saying, that really matters.

The Road That Led to HDS

While in college I had also done an internship with the Center for Responsible Lending, which had a program called the Faith & Credit Roundtable. Part of the work we did there was train clergy to go to Capitol Hill and advocate for their parishioners and congregations regarding economic issues like payday lending, predatory lending, fair housing, and student loan debt, particularly in the Black community which, compared to other communities, has a very high debt-to-wealth ratio. Seeing the impact of that work awakened my aspirations, and I said to myself, “I can do this. I want to do this.” Incidentally, one of the directors of that program had received her master of divinity degree at Duke Divinity. She was the one that advised me to think about the possibility of attending divinity school. I, however, was under the impression that divinity school was only for those who wanted to preach or become a pastor, so I was really blind to all the opportunities that divinity school could bring. I did however end up applying to a few divinity schools, and ultimately Harvard. What solidified the decision for me was knowing that HDS provided the opportunity to take classes in all the different schools. So, if I wanted to see how religion affected public policy, I would have the Kennedy School. If I wanted to see how it affected business, I would have the Business School. If I wanted to see how it affected law and social justice, I would have the Law School. Therefore, making the choice to be in an institution that would enrich me in all of these capacities was a no-brainer.

Smelling the Roses

Something I’ve been reflecting on lately is that one of the biggest things we can do as students of ministry is to understand how healing works, and that it takes a communal effort to heal. Healing matters to the oppressed, the disenfranchised, the poor and the hungry. People can get justice, they can get policies and even resources, but it's the healing that actually helps them to move forward. If an individual gets justice, but still carries trauma, are they really obtaining true justice? People always ask me if I have plans to run for office, but I don't know about all that. I just love doing the work. If it provides an opportunity, sure; but that's not a goal of mine. I just want to pursue God's will for my life, and whatever that brings, I will take. I’m at the school I’ve always wanted to go to, doing the work that I always dreamed of doing, meeting the people I’ve always wanted to meet. So, I'm just trying to enjoy the moment right now, and be grateful and settled in the blessings that God has put in my life.

Interview by Suzannah Omonuk; photos courtesy of Amos Jackson III

#Harvard Divinity School#Harvard#politics#Religion#kamala harris#howard university#baptist church#social justice#large

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sewn into his jacket an incoherent note

How to Make Love, Write Poetry, & Believe in God by Nin Andrews

A few weeks ago, I was part of a Hamilton-Kirkland College alumnae poetry reading, and after the reading a woman asked a simple question: “How do you write a poem?” I didn’t have an answer so I suggested a few books by poets like John Hollander, Mary Oliver, and Billy Collins. The woman said she had read books like that, but they didn’t help. She wanted something else, like a genuine operating manual—a step by step explanation.

I, too, love instruction manuals, especially those manuals on how to perform magic: write a poem or know God or make love, if only love were something that could be made. Manuals offer such promise. Yes, you, too, can enter the bee-loud glade and the Promised Land and have an orgasm.

I love the idea that my mind could be programmed like a computer to spit out poems on demand—poems with just the right number of lines, syllables, metaphors, meanings, similes, images . . . And with no clichés, no matter how much I love those Tom, Dick and Harry’s with their lovely wives, as fresh as daisies. I can set them in any novel or town in America, and they will have sex twice a week, always before ten at night, never at the eleventh hour, and it will not take long,time being of the essence.

I love sex manuals, too: those books that suggest our bodies are like cars. If only we could learn to drive them properly, bliss would be a simple matter of inserting a key, mastering the steering wheel, signaling our next moves, knowing the difference between the brakes and the gas pedal, and of course, following the speed limit.

A depressive person by nature, I am also a fan of how-to books on God, faith, happiness, the soul, books that suggest a divine presence is always here. I just need to find it, or wake up to it, or turn off my doubting brain. That even now, my soul is like a bird in a cage. If I could sit still long enough and listen closely, it might rest on my open palm and sing me a song.

God, poetry, sex, they offer brief moments of bliss, glimpses of the ineffable, and occasional insights into that which does not translate easily into daily experience, or loses its magic when explained.

In college, I took classes in religion, philosophy and poetry, and I studied sex in my spare time—my first roommate and I staying up late, pondering the pages of The Joy of Sex. As a freshman, I auditioned my way into an advanced poetry writing class by composing the single decent poem I wrote in my college years. The poem, an ode to cottage cheese, came to me in a flash as a vision nestled on a crisp bed of iceberg lettuce. Does cottage cheese nestle? I don’t know, but the professor kept admiring that poem. He said all my other poems paled by comparison.

This was in the era of the sexual revolution,long before political correctness and the Me-Too movement. My roommate, obsessed with getting laid, said we women should have been given a compass to navigate the sexual landscape. She liked to complain that she’d had only one orgasm in her entire life, and she wanted another. “What if I am a one-orgasm wonder?” she worried. The subject of orgasms kept us awake, night after night.

In religion class, my professor told the famous story about Blaise Pascal who had a vision of God that was so profound, his life seemed dull and meaningless forever afterwards. He never had another vision. But he had sewn into his jacket an incoherent note to remind him of the singular luminous experience.

The next day in religion class, a student stood up and announced that the professor was wrong—about Pascal, God, everything. The student knew this because he was God’s friend. He even knew His first name, and what God was thinking. The professor smiled sadly, put his arm around the student, and led him out of the classroom, down the steps and into the counselor’s office. When the professor returned, he warned us that if we ever thought we knew God, we should check ourselves into a mental institution. Lots of insane people know God intimately.

But, I wondered, what would God (or the transcendent—or whatever word you might choose for it: the muse, love, the orgasm, the soul, the higher self) think of us? For example, what would a muse think of a writer trying, begging, praying to enter the creative flow? All writers know it—that moment when inspiration happens. The incredible high. And the opposite, when words cling to the wall of the mind like sticky notes but never make it onto your tongue or the page.

What would an orgasm think of all the people seeking it so fervently yet considering it dirty, embarrassing, unmentionable? And then lying about it. “Did you have one?” a man might ask. “Yes,” his lover nods. But every orgasm knows it cannot be had. Or possessed. Or sewn into the lining of a coat. No one “has” an orgasm. At least not for long.

What did God think of Martin Luther, calling out to him in terror when a lightning bolt struck near his horse, “Help! I’ll become a monk!” And later, when he sought relief from his chronic constipation and gave birth to the Protestant Reformation on the lavatory—a lavatory you can visit today in Wittenberg, Germany.

I don’t want to evaluate Luther’s source of inspiration. But I do want to ponder the question: How do you write a poem? Is there a way to begin?

I think John Ashbery gave away one secret in his poem, “The Instruction Manual:” that it begins with daydreaming. Imagination. And the revelation that the mind contains its own magical city, its own Guadalajara, complete with a public square and bands and parading couples that you can visit this enchanted town for a limited time before you must turn your gaze back to the humdrum world.

But a student of Ashbery’s might cringe at the suggestion that poetry is merely an act of the imagination. In order to master the dance, one must know the steps. And Ashbery was a master. So many of his poems follow a kind of Hegelian progression, traveling from the concrete to the abstract to the absolute. Or what Fichte described as a dialectical movement from thesis to antithesis to synthesis. Fichte also wrote that consciousness itself has no basis in reality. I wonder if Ashbery would have agreed.

In college I wrote an inane paper, comparing Ashbery’s poetry to a form of philosophical gardening in which the poet arranges the concrete, meaning the plants or words, in such an appealing order that they create the abstract, or the beauty, desired. Thus, the reader experiences the absolute, or a sense of wonder at the creation as the whole thing sways in the wind of her mind.

Is there a basis in reality for wonder? Or poetry? I asked. Or are we only admiring illusions, the beautiful illusions the poet has created? How I loved questions like that. I wanted to follow in the footsteps of Fichte and Hegel and Ashbery and write mystical and incomprehensible books. I complained to my mother that no matter how hard I tried, I could not compose an actual poem or philosophical treatise—I was trying to write treatises, too. “That’s good,” she said. “Poets and philosophers are too much in their heads, and not enough in the world.”

I didn’t argue with her and tell her that not all poets are like Emily Dickinson. Or say that Socrates was put to death for being too much in the world, for angering the public with his Socratic method of challenging social mores, and earning himself the title, “the gadfly of Athens.”

Instead, I thought, That’s it! If I want to be a poet, I just need to separate my head from the world. Or at least turn off the noise of the world. And seek solitude, as Wordsworth suggested, in order to recollect in tranquility. I imagined myself going on a retreat or living in a cave, studying the shadows on the wall. Letting them speak to me or seduce me or dance with me.

The shadows, I discovered, are not nice guests. Sometimes they kept me awake all night, talking loudly, making rude comments, using all the words I never said aloud. “Hush,” I told them. “No one wants to hear that.” Sometimes they took on the voices of the dead and complained I hadn’t told their stories yet or right. Sometimes they sulked and bossed me about like a maid, asking for a cup of tea, a biscuit, a little brandy, a nap. One nap was never enough. When I obeyed and closed my eyes, they recited the poems I wanted to write down. “You can’t open your eyes until we’re done,” they said, as if poetry were a game of memory, or hide and seek in the mind. Other times they wandered away and down the dirt road of my past, or lay down in the orchard and counted the peaches overhead. Whatever they did or said, I watched and listened.

That’s how I began writing my first real poems. I knew not to disobey the shadows. I knew not toturn my back on them and look towards the light as Plato suggested—Plato who wanted to banish the poets and poetry from his Republic.I knew to not answer the door if the man from Porlock came knocking.

To this day I am grateful for the darkness. For the shadows it creates in my mind. It is thanks to them I have written another book, The Last Orgasm, a book whose title might make people cringe. But isn’t that what shadows do? And much of poetry, too? Dwell on topics we are afraid to look at in the light?

(https://blog.bestamericanpoetry.com/the_best_american_poetry/2020/09/how-to-make-love-write-poetry-believe-in-god-by-nin-andrews.html)

Five prose poems by Nin Andrews (formatting better at http://newflashfiction.com/5-prose-poems-by-nin-andrews/)

Duplicity

after Henri Michaux “Simplicity”

When I was just a young thing, my life was as simple as a sunrise. And as predictable. Day after day I went about doing exactly as I pleased. If I saw a lovely man or women, or beauty in any of its shapes and forms and flavors, well, I simply had to have it. So I did. Just like that. Boom! I didn’t even need a room.

Slowly, I matured. I learned a bit of etiquette. Manners, I discovered can have promising side effects. I even began carrying a bottle of champagne wherever I went, and a bed. Not that the beds lasted long. I wasn’t the kind to go easy on the alcohol or the furnishings, nor was I interested in sleep. It never ceased to amaze me how quickly men drift off. Women, many of them, kept me going night after night. You know how inspiring women are.

But then, alas, I grew tired of them as well. I began to envy those folks who curl up into balls each night, their bodies as heavy as tombstones. I tried curling up with them, slowing my breath, entering into their dreams. What dreams! To think I had been missing out all along! That’s when I became a Zen master, at one with the night. Now I teach classes on peace, love, abstinence. At last I have found bliss, I tell my followers. The young, they don’t believe it. But really, I ask you. Would I lie?

The Broken Promise

after Heberto Padilla, “The Promise”

There was a time when I promised to write you a thousand love poems. When I said every day is a poem, and every poem is in love with you. But then the poems rebelled. They became a junta of angry women, impossible to calm or translate, each more vivid, sultry, seductive than the next. Some stayed inside and sulked for weeks, demanding chocolates, separate rooms, maid service. Others wanted to be carted around like queens. Still others took lovers and kept the neighbors up, moaning at all hours of the day and night. One skinny girl (remember her? the one with flame-colored hair?) moved away. She went back to that shack down the road where we first met. At night she lay down in the orchard behind the house and let the dark crawl over her arms and legs. In the end even her dreams turned to ash and blew away in a sudden gust of wind.

Little Big Man

after Russell Edson “Sleep”

There was once an orgasm that could not stop shrinking. Little big man, his friend called him, watching as he grew smaller and smaller with each passing night, first before making love, then before even the mention of making love, then before even the mention of the mention of making love. Oh, what a pathetic little thing he was.

One night he tried reading, Think and Grow Big, but it only caused him to shrink further inside himself. Oh, to grow large and tall as I once was, he sighed. What he needed, he knew, was a trainer with a whip and chains. Someone to teach him to jump through hoops and swing from a trapeze and swallow fire until he blazed ever higher into the night. Yes, he shuddered. Yes! as he imagined it. A tiny wisp of smoke escaped his lips.

Questions to Determine if You Are Washed Up

after Charles Baudelaire, “Get Drunk!”

Do you feel washed up lost, all alone? Do you fear that time is passing you by like a train for which you have no ticket, no seat? That you have lived too long in the solitude of your room and empty mind, that now you are but a slave of sorrow? Or is it regret? Do you no longer taste the wine of life on your lips, tongue, throat? Is there not even even a chance of intoxication? Bliss? No poetry or song above or below the hips? No love in the wind, the waves, in every or any fleeting and floating thing? No castles in your air? No pearls in your oysters? Are you wearing a pair of drawstring pants?

Remembering Her

after Herberto Padilla

This is the house where she first met you. This is the room where she first said your name as if it were a song. This is the table where she undressed you, stripping away your petals, leaves, your filmy white roots and sorrows. And there on the floor is the stone you picked up each morning, the stone you clung to night after night. Sometimes she kicked it aside. Sometimes she placed in on the sill and blew it out the window as her presence filled you like a glow, and you thought for an instant, I, too, can fly.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ICSA: Virtual Summer Conference, Saturday and Sunday, July 11-12

This two-day event will include a variety of presentations, panels, and workshops for former members of cultic groups, families and friends, professionals, and researchers.

_______________________________________

Day 1 – Saturday Conference Sessions, July 11, 2020 (11 am - 4 pm US Eastern Time)

Day 2 – Sunday Workshops, July 12, 2020 (11 am - 4 pm US Eastern Time)

_______________________________________

Saturday, July 11, 2020

11:05 -11:50 / "The Neurobiology of Sexual Abuse: Flashbacks, Triggers and Healing" (Doni Whitsett)

The first part of this presentation presents a neurobiological understanding of flashbacks and triggers resulting from sexual abuse. The second part of the presentation offers suggestions for dealing with triggers, learning to manage them, and perhaps using them to facilitate healing.

11:05 -11:50 / "MIND FIXERS: The History of Mass Therapy With its Roots in Mind Dynamics Institute, Misuse of Zen Insights, and Hyping the Positive Thinking of New Thought Religion." (Joseph Kelly, Joseph Szimhart, Patrick Ryan)

The title for this presentation, “MIND FIXERS: The History of Mass Therapy With its Roots in Mind Dynamics Institute, Misuse of Zen Insights, and Hyping the Positive Thinking of New Thought Religion,” covers a vast arena for specialized workshops that range from one day to several weeks. Borrowing techniques from encounter group formats, military boot camp training, and the mindfulness movements these specialized groups operate as unregulated mass therapy businesses and are not licensed as mental health professions. The stated purpose of these “large group awareness trainings” is to increase self-realization and success in life. The outcomes, however, are problematic with some critics claiming that a form of “brainwashing” is taking place that emphasizes promotion of the workshops while any real-life gains are highly questionable. Some participants report psychological and social harm. The speakers will guide a discussion to address the criticisms.

12:00 - 12:50 / "Coercive Control and Persuasion in Relationships and Groups– Intersections and Understandings" (Rod Dubrow-Marshall; Linda Dubrow-Marshall; Carrie McManus; Andrea Silverstone)

This panel will examine contemporary understandings of coercive control in relationships and groups with practitioners from both sides of the Atlantic. The way in which the term ‘coercive control’ is now being used and applied in different jurisdictions will be discussed and how changes to the law are reflecting advances in our understanding of how coercive control works psychologically across contexts. It will also be explored how a heightened dialogue between practitioners and researchers across the fields of intimate partner violence and cults/sects and extremist groups is leading to enhanced appreciation of commonalities in the process of psychological indoctrination. Positive implications for prevention, exit and recovery and rehabilitation across these areas will also be discussed along with recommendations for policy makers.

12:00 - 12:50 PM / "Unification Church (Moonie) SGAs: The Future is Unwritten" (Lisa Kohn; Teddy Hose; Jen Kiaba)

A panel of Unification Church (Moonie) SGAs (Jen Kiaba, Teddy Hose, and Lisa Kohn) will discuss their different experiences of living in, leaving, and learning to thrive after being part of the Unification Church (the “Moonies”). The questions and discussions will focus on how the panelists experienced being part of the Unification Church, how they were able to leave the Church, how they still feel affected by their childhood in the Church, and how they have healed since leaving the Church.

1:00 - 1:50 PM / "Lived Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Former Cult Members – Counseling Implications" (Cyndi Matthews; Stevie Powers)

Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) individuals growing up in religious cults can face opposition to their sexual orientation. They may struggle with depression, anxiety, drug/alcohol abuse, self-mutilation, and suicidal ideation. Research by presenters will describe lived experiences of LGB individuals who grew up in religious cults. Best practices based on this research, APA & ACA Codes of Ethics, along with ASERVIC and ALGBTIC competencies will be presented.

1:00 - 1:50 PM / "How Female Former Cult Members Can Reclaim their Relationship with Knowledge and Self-Identity" (Jacqueline Johnson)

High-control and coercive groups work at stealing and silencing the thoughts and knowledge base, and subsequently, the voices, of its members. For females, this dynamic becomes more problematic when those female members are, or have been, part of a misogynous group that incorporates numerous ways of subjugating women. This presentation will outline the research of Belenky et al (1986), which examines the development of women’s self, voice, and mind. Belenky and her colleagues describe the cognitive and intellectual development in women in terms of five knowledge positions (ranging from silence to construction) through which women develop their identity. This presentation will examine ways that high-control, misogynous groups subjugate women, how this affects the epistemology of female cult members, her resulting relationship to knowledge, and the possible impairments to her ability to construct her own knowledge, develop her own identity, and find her own voice. Implications for therapists working with women are discussed in terms of helping former female cult members begin to develop their identity, find their voice, and construct their own knowledge.

2:00 - 2:50 PM / "Raised in a Cult: Psychological and Social Adjustment of Second- and Third-Generation Former Cult Members" (Sofia Klufas)

Former cult members often find themselves struggling to re-integrate into mainstream society and typically describe long periods of recovery post-exit. The current study aimed to qualitatively explore the experiences of individuals raised in cults (1) during, (2) in the process of leaving, and (3) post-cult involvement in order to understand how cultic influences might impact their ability to socially and psychologically adjust to life outside of the cult upon defection. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 8 participants from across North America and Europe who self-identify as second- and/or third-generation former cult members. Responses were qualitatively analyzed for totalistic patterns of influence which may dissuade members from leaving the group or simply deviating from its norms. Participants reported a wide range of emotional responses and psychological difficulties which they perceived to be the result of their cultic upbringing including but not limited to hyper-arousal, anxiety, doctrine-related fears, feelings of isolation, depression, anger/outbursts and suicidal tendencies. Identity reconstruction and social adjustment challenges such as relationship loss due to shunning, difficulty connecting with others, language differences were also reported by participants. Raised-in cult members are a distinct population from converted cult members as they have been exposed to cultic influence throughout the course of their developmental period. While the experiences of these two groups are comparable in many ways, previous research has demonstrated that raised-in cult members are at higher risk for social and psychological difficulties (Furnari, 2005).

2:00 - 2:50 PM / "What does awe have to do with it?" (Yuval Laor)

What is awe? What role does awe play in cult recruitment? And what brings about awe experiences? The talk will discuss these and other topics related to this strange emotion and the effects it can have on us.

3:00 - 3:50 PM / "Nxivm: the Reinventive Path to Success?"(Susan Raine, Stephen Kent)

In this session I discuss the multi-level cultic organization, NXIVM. I propose that NXIVM operated as, what Susie Scott (2011) calls, a reinventive institution—that is, an organization that people enter into voluntarily, because they promise to help people transform or reinvent themselves through personal and professional growth, self-actualization, self-improvement, and success. The group’s founder and leader, Keith Raniere offered members these outcomes via the Stripe Path—a hierarchal system of courses that were supposed to empower people as they worked towards personal growth and world peace. Scott stresses, however, that reinventive institutions incorporate structures of power and are far from benign. This dynamic is evident in NXIVM, which offered to empower its members but ultimately ended up disempowering many of them—especially its most committed female followers. I follow up this discussion by addressing how Raniere had groomed many of these most dedicated women for sexual abuse and exploitation. Grant Sinnamon’s (2017) research on adult grooming and Janja Lalich’s (1997) work on the psychosexual exploitation of women in cults provide extremely useful insights for understanding Raniere’s behaviour.

3:00 - 3:50 PM / "What Do I Tell People? Empowered Ways that Cult Survivors and their Families Can Tell their Stories. Cults, Recovery and Podcasts." (Rachel Bernstein)

Nearly all my clients and podcast guests have experienced fear when thinking about telling people about their cult-related experiences. Many live in isolation because of this, and at times it's for good reason. When they've tried to share their stories, they've been responded to with insulting judgment and condescension, with confusion and disbelief, or with inappropriately voyouristic interest and invasive follow-up questions. Learn how to take control of that conversation and present your story in an educational and empowered way so you don't have to live in fear of these moments and remain silent and alone.

This two-day event will include a variety of presentations, panels, and workshops for former members of cultic groups, families and friends, professionals, and researchers.

_______________________________________

Sunday, July 12, 2020

11:00 AM - 1:00 PM / Research Workshop

The Research Workshop will be facilitated by Rod Dubrow-Marshall, Chair of the ICSA Research Network and Co-Editor of the International Journal of Coercion, Abuse and Manipulation (IJCAM). He will speak initially with a short overview about research on cults and coercive control and he will be followed by introductory talks by Cyndi Matthews, Managing Editor of IJCAM, Marie-Andrée Pelland, Co-Editor of IJCAM and Omar Saldaña from the University of Barcelona, who will each speak about research and developments in their respective areas.

The Research Workshop will focus on key areas of research currently taking place on cults and extremist groups and related areas of coercive control including intimate partner violence, trafficking and gangs. Researchers will be able to discuss the challenges they may be facing or may have faced in proposing new research projects in these areas, including getting institutional approval (IRB or ethics committee), finding participants, clarifying aspects of research design and getting support from faculty/professors. Experienced researchers will be on hand to answer questions and all those present will be able to share their ideas on current and future research including possibilities for collaboration. Plans and opportunities for the ICSA Research Network will also be discussed.

11:00 AM - 2:00 PM / Mental Health Workshop

1:00 PM - 4:00 PM / Former Member Workshop

This workshop will include an Overview of Recovery, touching on such subjects as attachment, boundaries, and identity. There will also be an opportunity to offer reflections on sessions people have attended during the first day of the conference. The workshop is intended for both first and second/multi-generation former members.

(William Goldberg, Gillie Jenkinson)

2:00 PM - 4:00 PM / Family Workshop

"Building Bridges; Leaving and Recovering from Cultic Groups and Relationships: A Workshop for Families"

Topics discussed include assessing a family’s unique situation; understanding why people join and leave groups; considering the nature of psychological manipulation and abuse; being accurate, objective, and up-to-date; looking at ethical issues; learning how to assess your situation; developing problem-solving skills; formulating a helping strategy; learning how to communicate more effectively with your loved one; learning new ways of coping.

(Rachel Bernstein, MSed, LMFT, Joseph Kelly, Patrick Ryan)

_______________________________________

Virtual Summer Conference

Lisa Kohn

To the Moon and Back: A Childhood Under the Influence

VIDEO: ‘Meet the author’ interview

How do you learn to love yourself?

Lisa Kohn interview on Generation Cult

_______________________________________

Teddy Hose

Talk Beliefs VIDEO: Over the Moon – Escaping Sun Myung Moon, Hak Ja Han and their family

Talk Beliefs VIDEO: Secrets of the Moonies

Growing Up “Moonie” by Teddy Hose

_______________________________________

Jen Kiaba

The Purity Knife

Life Without Reverend Moon

Why Didn’t You Just Leave?

Jen Kiaba

: Hello and welcome to my least favorite question in the entire world. It’s one I’ve heard more times than I care to count, and sadly I think that’s something many cult survivors can relate to. In the past that question used to make me clam up and spiral into shame, or mumble, “It’s not that simple.” But in those days I didn’t fully understand the coercive control mechanism that were used to keep me, and so many others, trapped. Read more:

https://jenkiaba.medium.com/lessons-on-leaving-why-didnt-you-just-leave-789953c4689a