#Hopi-Navajo Mesas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Inspired by @clonerightsagenda’s thoughts about the Ambiguously Brown Spacefuture trope, I kinda want to see more creativity with how Earth is treated in spacefuture sci-fi.

There are plenty of examples where Earth is the center of everything. Star Trek is the obvious one: it’s a bustling interstellar multispecies space society, and Earth is where Starfleet is headquartered and it’s often reflexively and unthinkingly treated by the narrative like it’s the most important planet in the Federation. (Most of our main viewpoint characters are Human, so it’s the most important planet to THEM because it’s their home, but even beyond that, Earth is treated as critically key to the Federation in a way that, say, Betazed is not.)

More recently, the common trope is that the centers of society and culture and economy and politics are elsewhere. Other planets are important, and Earth is either an unimportant backwater that no one really cares about, or galactic humanity has nearly forgotten about it entirely. This is explicit in Becky Chambers’s Wayfarers, strongly implied in The Murderbot Diaries, and one line in Ancillary Justice suggests that too. Ofc this isn’t entirely new—from what I understand it’s what’s going on in Dune too.

And they do this for obvious reasons: the authors are all interested in social and political worldbuilding that is not tethered to real Earth nations, politics, prejudices, and general baggage. Second-world fantasy authors are allowed to do this with no strings attached, but sci-fi authors who want to do social worldbuilding from the ground up have to justify why people don’t appear to identify as Chinese or Latino or Hopi or American anymore (and more often than not, not Jewish or Catholic or Muslim or Hindu or Baha’i or whatever either), why those identities don’t come into conflict with the new planetary identities and spacefuture religions the author wants to write about. It’s been so long that the origin of humanity is forgotten or irrelevant.

Star Wars is honestly underappreciated for the bold, creative, unique choice to have a bustling interstellar multispecies space society with lot of humans… and no Earth. At all. Where do humans come from? Irrelevant. Not Earth though.

And honestly I wish more sci-fi that wants to write in this space took more of a cue form Star Wars to just own it. (I actually thought the Imperial Radch HAD done the same thing—functionally a second-world fantasy, but in a spacefaring setting—until Kat pointed out the reference to arguing over which planet was the real origin of humanity.) If you posit your space future as our future, but Earth is no longer relevant and is generally forgotten… I guess it depends on how far out it is, but it strains my credulity that no one remembers or cares! The Jews in the spacefuture don’t know/remember/care where Jerusalem is? Muslims in the spacefuture decided that going to Mecca just kinda isn’t worth it? The spacefuture Papal seat is no longer in Rome and the future Catholics don’t know or care that it was ever anywhere else? All the Hopis left the Three Mesas and all the Navajos left Dinétah and all the Māori left Aotearoa and then just… forgot about it? Really? That isn’t true after hundreds and even thousands of years today; why would it be true hundreds or even thousands of years in The Spacefuture?

There are some works that do a little more complexity with spacefuture planetary societies and cultures vs. memory of Earth—the Vorkosigan Saga positions Old Earth as a culturally important memory even if it’s not a politically important planet, and The Locked Tomb makes Earth a holy center place that is mythicized more than it’s known or inhabited, for magic necromancy reasons.

I’d like to see more of that, Earth holding some sort of unique place in spacefuture humans’ culture in a historically informed way, even if you actually want to write about other things. Or go the Star Wars route and proudly proclaim that this takes place a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, don’t worry about it.

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Design Notes: Warren

This is the third in a series of Kyoto Animation-style character design sheets. They’re in the style of my Fablehaven animation. I go into detail under the cut.

Here are some quotes from the books referencing Warren’s appearance.

'Handsome and quiet? White hair and skin? Dale's brother' Warren was no longer albino. He had dark hair and intense hazel eyes. Warren wore a dark orange T-shirt and gray sweatpants. Contrasted against the shirt, his arms looked white as milk. Dale turned him so that he was seated on the edge of the bed. When Dale let go, Kendra half-expected Warren to topple over, but he remained seated upright, eyes vacant. He looked to be in his twenties, at least ten years younger than Dale. Even with pale skin, white hair, and empty eyes, Warren was unexpectedly handsome. Not quite as tall as his brother, Warren Had broader shoulders and a firmer jaw. His features were more finely sculpted. Looking at Dale, she would not picture his brother handsome. Looking at Warren, she would not picture his brother plain. And yet seen together, a family resemblance persisted. Standing in the doorway, he studied her. He looked even more handsome now that he had possession of himself. His striking eyes were a silvery hazel. Had they been that color before? He ran a white hand through his thick hair, then stared at his palm. "I thought I was looking sort of bleached", he said, flexing his fingers. "I have leather armor under my shirt," Warren said. "The freak still gave me a good scratch. I keep my knives sharp." Warren crouched, recovering his throwing knife from where it had fallen. Warren wore several new rings and clung to a sheathed sword with a pearly hilt.

Seeing that he had "several new rings" implies he would wear rings normally, and that those are additions.

When introducing himself, Warren mentions being a Scorpio, making him... something of a zodiac girlie.

All this gave me the impression of him that you see reflected in his design. The throwing knives, too, and evidence of frequent injury are present.

Below is a design for the sword with the pearly hilt from Lost Mesa. Swords aren't a weapon really seen in Navajo or Hopi cultures, so I tried to make a sword of fairy-like design.

As a personal touch, I gave him the down-turned eyes of an elderly cat. His face is meant to look like a smug, somewhat mischievous elderly cat.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bracket!

Thank you to everyone who was interested and everyone who voted! You chose Tusayan (Sosi/Dogoszhi) and Mesa Verde to represent our black-on-whites, and Plain Smudged and Corrugated to represent our utility ware types! (I was not expecting such a plain smudged sweep - I love to see the enthusiasm!)

So, without any more ado, here is the Finalized Pottery Bracket!

There are SO many more pottery types than these 16, and every time I go to a museum or search up on my favorite Southwest pottery reference websites (New Mexico Office of Archaeology's Pottery Typology Project and Northern Arizona University's American Southwest Virtual Museum) I am reminded of just HOW many different pottery styles there are and how I want to show all of them off...

But these sixteen cover a wide range of styles, locations, and time periods, and give a good sweep of pottery history of the Southwest!

Instead of being separated into seeds, they're grouped by theme. More details on each matchup below:

Tournament 1: Northern Polychromes. Salado Polychrome (that is, Roosevelt Red Ware, Pinto/Gila/Tonto polychrome) vs. Fourmile Polychrome (and the closely associate St. Johns Polychrome). Red, white, and black pottery made in Arizona and New Mexico.

Tournament 2: Southern Polychromes. Ramos Polychrome vs. Trincheras Polychrome. Red, black, purple, and cream pottery made in Chihuahua and Sonora.

Tournament 3: Triumphant Black-on-whites. The return of Mesa Verde Black-on-white and Sosi & Dogoszhi Black-on-white, going head to head!

Tournament 4: Yellow-ish wares. Ancestral Hopi Jeddito Yellow Ware (including the dramatic Sityatki Polychrome) from the Hopi Mesas of Arizona vs. Hohokam red-on-buff types (including Sacaton Red-on-buff and Santa Cruz Red-on-buff) from southern Arizona.

Tournament 5: Return of the Utility Wares. New corrugated and new plain smudged types, still mostly from the Mogollon region both, going to single elimination!

Tournament 6: Mexican Originals. Mexican Majolica, in its distinctively popular type Talavera, the brilliantly colored pottery from the Spanish colonial period in the 1600s, is primarily associated with Puebla, Mexico, which is rather far south of our US Southwest/Mexican Northest topic area, but has for centuries been a popular throughout Spanish-influenced Mexico and the US Southwest. Mata Ortiz, meanwhile, is a modern art pottery style developed in the 1960s in Chihuahua, taking inspiration from the archaeological pottery of Paquimé (including Ramos Polychrome).

Tournament 7: Pueblo Revivals. Sikyatki Revival is the name given to the style of Hopi pottery developed by the Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo in the late 1800s based on archaeological pottery from excavations at Sikyatki Village; vs. San Juan Revival, a pottery movement by potters of Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo (formerly known as San Juan Pueblo) starting in the 1930s.

Tournament 8: Modern Pueblo Art. Some of my personal favorite pottery styles picked out from many, many artists working in the Southwest today, Black-on-black (matte black on polished black, or vice versa) pottery developed in the 1910s by a San Ildefonso potter, and still popular primarily in Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos, vs. Modern Acoma Pottery, a distinctive style in bold reds, whites, and blacks that is just. Gorgeous. You'll see. (I don't mean to diss modern Hopi and Zuni and Navajo and everyone else's styles by not including them, because they're also beautiful and striking, but I had to stop somewhere!)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a funky friend for #FrogFriday:

Frog kachina, c.1960-80 Made by Ted Puhuyesua, Diné (Navajo) in Hoatvela (Hotevilla),Third Mesa, Hopi Reservation; Navajo County, AZ, USA carved & painted wood w/ feathers, 17.5 x 7 x 5 cm Smithsonian NMAI NMAI_270961

#animals in art#frog#kachina#doll#Ted Puhuyesua#Navajo art#Native American art#20th century art#woodwork#Smithsonian NMAI#Frog Friday

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

KATHERINE SMITH // ACTIVIST

“She was a Navajo activist, cultural educator, land defender, and resistor who protected Navajo land and refused to leave Big Mountain (Black Mesa). A 1985 documentary Broken Rainbow depicts the struggle of the Navajo amid government enforced relocation of thousands from Black Mesa in Arizona after the enactment of the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act of 1974. The documentary film about the relocation was nominated for an Oscar.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trade and Conflict Apache and Neighboring Tribes

Image generated by the author

Trade and Conflict Among the Apache and Neighboring Tribes: A Tapestry of Relationships

Introduction: The Dance of Trade and Conflict

Imagine a vast landscape, the sun setting behind the rugged mountains of the Southwestern United States, painting the sky in hues of orange and pink. In this vibrant tableau, the Apache people are not just surviving; they are engaging in a delicate dance of commerce and conflict. The air is thick with the aromas of herbs and roasted meats as traders from various tribes gather. Here, amidst the clamor of voices and the exchange of goods, a complex web of relationships unfolds—one built on mutual respect, shared needs, and historical tensions. What does this ancient tapestry reveal about human nature, and what can modern societies learn from it?

The Apache, whose rich cultural fabric intertwines with their neighboring tribes such as the Navajo, Hopi, and Pueblo, show us that each encounter in life carries lessons. Their interactions, steeped in trade and occasionally marred by conflict, are a testament to the intricate balance of relationships. As we delve deeper into the historical context, cultural significance, and modern relevance of these dynamics, we will uncover the profound wisdom embedded within the Apache way of life.

Historical Context: The Lifeblood of Trade

Historically, trade was not merely a transactional affair for the Apache; it was the lifeblood of their survival and prosperity. Picture a bustling market where Apache traders, equipped with hides, pottery, and tools, exchanged goods with neighboring tribes. This was a world where every item carried a story, and every trade was a bridge between cultures. The Apache established crucial connections through these exchanges, helping them navigate the challenges of their arid environment.

However, this web of commerce was fraught with complexities. Competition for resources often ignited tensions, particularly over land and differing worldviews. The arrival of European settlers further disrupted established trade routes, leading to increased territorial disputes. The Apache, known for their adaptability, turned to guerrilla warfare tactics—not only to protect their interests but also to maintain their way of life. This pragmatic approach to trade highlighted the duality of peace and conflict, as the Apache sought to balance commerce with strategic defense.

Cultural Significance: Weaving Relationships

In Apache culture, trade is not merely about the exchange of material goods; it is a sacred act that symbolizes trust and mutual understanding. To the Apache, every trade encounter is an opportunity to forge alliances, strengthen community ties, and share cultural insights. Imagine a scene where two tribes meet on neutral ground, exchanging goods and stories, creating bonds that transcend mere commerce. Apache philosophy teaches that conflict, often rooted in competition, can serve as a catalyst for growth and understanding.

Trade routes were not just pathways for goods; they were conduits of cultural exchange, enriching identities and survival strategies. Through the lens of Apache spirituality, trade signifies a deep interconnectedness among all beings, reinforcing the idea that relationships are vital to the human experience. This philosophy resonates strongly in the Apache view that every conflict has the potential to lead to new paths, underscoring the belief that trade and understanding are integral to fostering respect among tribes.

An Apache Story: The Healer's Journey

To illustrate the Apache approach to trade, let us journey into the heart of their culture through the tale of Haste, a healer of great wisdom. One day, Haste and her companions set out to gather herbs from the high mesas—herbs that symbolize abundance and life. Their goal was not just to procure natural remedies but to promote peace with the Pueblo tribe, which had been strained by misunderstandings.

As they trekked through fragrant wildflowers and towering sagebrush, Haste explained that trading extends beyond tangible goods; it encompasses trust, understanding, and shared experiences. Upon reaching the Pueblo lands, the group laid out their gathered herbs as offerings. In return, they received finely woven textiles, imbued with the stories of the Pueblo people. This exchange highlighted the Apache values of negotiation and unity, showcasing how the act of trade can build relationships and resolve tensions.

Examples and Expert Insights: A History of Exchanges

Throughout the centuries, the Apache engaged in trade with their neighbors, exchanging goods like textiles and pottery for hides and weapons. The 17th century marked a turbulent period when Spanish settlers disrupted these trade relationships, leading to violent encounters. Even after the establishment of the United States, the Apache maintained trade relations alongside territorial disputes with neighboring tribes. Experts emphasize the Apache's savvy trading practices, noting how misunderstandings over trade agreements often fueled conflicts.

For instance, the Apache's willingness to adapt to changing circumstances allowed them to forge alliances when necessary, demonstrating an astute understanding of the interconnectedness of commerce and conflict. This adaptability is reminiscent of a river that changes course yet continues to flow, navigating around obstacles in its path. The Apache's ability to balance trade and defense serves as a model for navigating complexities in modern relationships.

Practical Applications: Lessons for Modern Communities

The historical dynamics of trade and conflict among the Apache offer invaluable lessons for contemporary societies. The Apache practices of dialogue, negotiation, and resource management can enhance local economies and promote cooperation. Imagine communities embracing the idea that interdependence is key to survival, much like a symphony where each instrument contributes to a harmonious whole.

By emphasizing the interconnectedness of all beings, modern communities can adopt sustainable practices that honor both the land and their cultural heritage. Apache storytelling, rich in wisdom and tradition, reinforces cultural identity and serves as a powerful tool for education. As these insights are passed down to future generations, they ensure the continuity of Apache teachings, fostering a resilient and adaptive society.

Modern Relevance: Tradition Meets Technology

Apache wisdom continues to influence contemporary trade and conflict dynamics. In an era where technology plays a pivotal role, tribes are harnessing digital tools to strengthen economic ties while honoring their traditions. The Apache philosophy of adaptation reminds us that survival hinges on leveraging communal strengths, much like a tight-knit family that rallies together in times of need.

Modern trade agreements now often reflect the Apache emphasis on balance and dialogue. As communities navigate the complexities of globalization, the lessons learned from Apache history encourage a return to fundamental values—respect, reciprocity, and resilience. This call to action resonates deeply in the current climate, where understanding and collaboration are crucial for navigating an increasingly interconnected world.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The intricate dynamics of trade and conflict among the Apache and neighboring tribes reveal profound truths about the human experience. Apache culture views trade as a means to forge alliances and cultivate understanding, recognizing that conflict can stimulate adaptation. As we reflect on these historical interactions, we are reminded that dialogue and collaboration are essential for creating a more harmonious future.

In a world often divided by misunderstandings and competition, let us take a page from the Apache playbook. By embracing the lessons of respect, negotiation, and shared experiences, we can build bridges that honor our diverse cultures and pave the way for a more interconnected existence. As the sun sets over the mountains of the Southwest, let us carry forward the spirit of trade and understanding that has sustained the Apache people for generations, illuminating our path toward a brighter tomorrow.

Glossary of Apache Terminology

To further enrich our understanding of Apache culture, here are key terms that encapsulate their values:

Dine’��: The word for "the people," reflecting a deep sense of community.

K’é: An important concept of kinship and interconnectedness among all beings.

Nééz: The spirit of harmony and balance, essential in trade and relationships.

Call to Action

We invite you to explore further insights into Apache wisdom and its modern applications. Subscribe to our newsletter to receive resources on reconnecting with nature, indigenous knowledge, and ways to foster understanding among communities. Let us journey together toward a future enriched by the wisdom of those who came before us.

About Black Hawk Visions

Black Hawk Visions preserves and shares timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Inspired by Tahoma Whispering Wind, we offer eBooks, online courses, and newsletters that blend traditional knowledge with modern learning. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

AI Disclosure: AI was used for content ideation, spelling and grammar checks, and some modification of this article.

About Black Hawk Visions: We preserve and share timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

0 notes

Text

The Grand Canyon--Emergence of The People has been published on Elaine Webster - http://elainewebster.com/the-grand-canyon-emergence-of-the-people/

New Post has been published on http://elainewebster.com/the-grand-canyon-emergence-of-the-people/

The Grand Canyon--Emergence of The People

Eleven tribes call the Grand Canyon home: Havasupai Tribe, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Las Vegas Band of Paiute Indians, Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and the Yavapai Apache Nation. Each tribe has their own version of the emergence of their people from the point where the Little Colorado and the Colorado rivers meet at what is known as the Confluence.

Recently, the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition, called upon Washington to create a 1.1-million-acre National Monument to protect this sacred area from threats like uranium mining and over-development. (This proposal remains under consideration by the U.S. government.) The Havasupai Tribe, in particular, who have lived in and around the Grand Canyon since time immemorial, were last evicted from the area in 1928. Finally, the name of the campground and rest area along the Bright Angel Trail has been renamed to be Havasupai Gardens.

So, why do we care? Well, history repeats and we are now faced with many of the same challenges that drove ancient civilizations below ground, only to emerge in stages after the great floods receded. There is much speculation about pre-historical circumstances, but there is no denying the legendary similarities existing in most indigenous cultures—cultures which would not have had contact at the time of the catastrophic earth changes. It is not important for us to believe the mythology—it is important to study how people faced with insurmountable obstacles can begin again and do it peacefully.The Hopi emergence story describes how the Hopi people lived in the underworld for many years, where they were taught by the Kachinas about the ways of the world and the importance of living in harmony with nature. However, the time came when the Kachinas instructed the Hopi people to leave the underworld and emerge into the physical world.

The Hopi people followed the Kachinas’ guidance, and after a long and treacherous journey, they emerged from the depths of the Grand Canyon. After the emergence, the Hopi people continued to be guided by the Kachinas, who taught them how to survive in their new environment. The Kachinas instructed the Hopi people in agriculture, hunting, and spiritual practices, which helped them to establish a thriving community in the mesas and valleys of northeastern Arizona.

One of the most important crops grown by the Hopi is corn, which is considered a sacred food. The Hopi have developed over 24 different varieties of corn, each with unique properties and flavors. The Hopi use corn in a variety of ways, including for food, medicine, and as a part of their spiritual practices. In addition, these unique strains of corn can withstand the harshest of conditions on a planet that is becoming hotter and drier. This certainly is useful today.

Migration and societal connections are once again paramount. DNA samples from several tribes show striking similarities with Eastern Asian populations suggesting that migratory routes included crossing land and/or sea from Asia. The Zuni language, for instance, is considered by linguists as having no established relationship with other languages. However, one anthropologist has linked the language to a Japanese archipelago. This could be a result of Japanese Buddhist missionaries traveling to Mexico, then north during the 12th century CE. Regardless, human migratory patterns are more extensive than originally thought—we are all inter-related at some point. So, when we turn our backs on other cultures; we are turning our backs on ourselves—we are all in this together.

Next, bring on G.E. Kincaid, an American adventurer and explorer who, in the early 20th century, claimed to have made an incredible discovery within the depths of the Grand Canyon. His account of this remarkable find has since been the subject of intense debate and speculation, with many questions remaining unanswered to this day.

Kincaid was born in 1868 in Washington, D.C., and spent much of his youth exploring the wilderness around his home. He developed a deep fascination with ancient civilizations and lost cities, and this passion led him on numerous expeditions to remote regions across the globe. However, it was his journey to the Grand Canyon in 1909 that would prove to be his most controversial.

According to Kincaid, he was traveling down the Colorado River on a wooden raft when he noticed an unusual cave entrance on the canyon wall. Intrigued, he decided to investigate and found himself inside a vast underground chamber. As he explored the cavern, he was amazed to discover a series of intricate tunnels and passageways leading deep into the earth.

Further exploration revealed that the tunnels were home to a thriving civilization, complete with temples, homes, and even an enormous amphitheater. The walls of the chambers were adorned with intricate carvings and murals, depicting scenes of daily life and religious rituals. Kincaid also claimed to have found artifacts and relics that suggested the inhabitants of the underground city were a highly advanced and sophisticated culture.

Kincaid returned to the surface with a trove of photographs and sketches, as well as a detailed journal documenting his discovery. However, his account was met with skepticism and disbelief from many quarters. Some argued that the photographs were doctored or taken from other sources, while others suggested that Kincaid had simply fabricated the entire story as a publicity stunt.

Despite the controversy, Kincaid continued to promote his story and even offered to lead expeditions back to the underground city. However, he was never able to provide concrete evidence to support his claims, and the mystery of the Grand Canyon cave remains unsolved to this day.

So, as we look to our future, the question is: Will we fall victim once again, to a planetary collapse from war, famine, economic decline, political upheaval, and environmental changes, only to scramble underground to wait until we can re-emerge? Or have we learned enough to circumvent most catastrophes, band together, support each other and thrive? Let’s hope this is so.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey, would you be willing to elaborate on that "disappearance of the Anasazi is bs" thing? I've heard something like that before but don't know much about it and would be interested to learn more. Or just like point me to a paper or yt video or something if you don't want to explain right now? Thanks!

I’m traveling to an archaeology conference right now, so this sounds like a great way to spend my airport time! @aurpiment you were wondering too—

“Anasazi” is an archaeological name given to the ancestral Puebloan cultural group in the US Southwest. It’s a Diné (Navajo) term and Modern Pueblos don’t like it and find it othering, so current archaeological best practices is to call this cultural group Ancestral Puebloans. (This is politically complicated because the Diné and Apache nations and groups still prefer “Anasazi” because through cultural interaction, mixing, and migration they also have ancestry among those people and they object to their ancestry being linguistically excluded… demonyms! Politically fraught always!)

However. The difficulties of explaining how descendant communities want to call this group kind of immediately shows: there are descendant communities. The “Anasazi” are Ancestral Purbloans. They are the ancestors of the modern Pueblos.

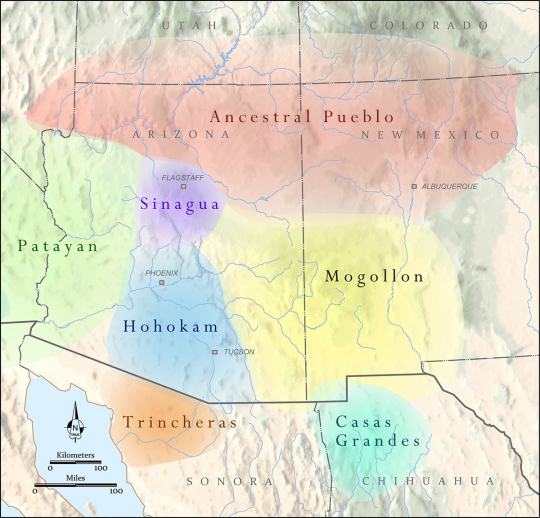

The Ancestral Puebloans as a distinct cultural group defined by similar material culture aspects arose 1200-500 BCE, depending on what you consider core cultural traits, and we generally stop talking about “Ancestral Puebloan” around 1450 CE. These were a group of people who lived in northern Arizona and New Mexico, and southern Colorado and Utah—the “Four Corners” region. There were of course different Ancestral Pueblo groups, political organizations, and cultures over the centuries—Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Kayenta, Tusayan, Ancestral Hopi—but they generally share some traits like religious sodality worship in subterranean circular kivas, residence in square adobe roomblocks around central plazas, maize farming practices, and styles of coil-and-scrape constructed black-on-white and black-on-red pottery.

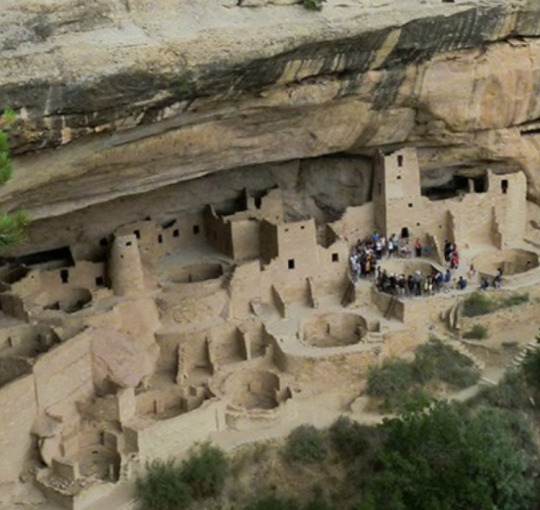

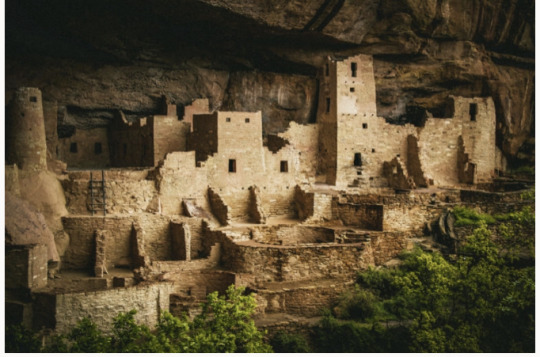

The most famous Ancestral Pueblo/“Anasazi” sites are the Cliff Palace and associated cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado:

When Europeans/Euro-Americans first found these majestic places, people had not been living in them for centuries. It was a big mystery to them—where did the people who built these cliff cities go? SURELY they were too complex and dramatic to have been built by the Native people who currently lived along the Rio Grande and cited these places as the homes of their ancestors!

So. Like so much else in American history: this mystery is like, 75% racism.

But WHY did the people of Mesa Verde all suddenly leave en masse in the late 1200s, depopulating the whole Mesa Verde region and moving south? That was a mystery. But now—between tree-ring climatological studies, extensive archaeology in this region, and actually listening to Pueblo people’s historical narratives—a lot of it is pretty well-understood. Anything archaeological is inherently, somewhat mysterious, because we have to make our best interpretations of often-scant remaining data, but it’s not some Big Mystery. There was a drought, and people moved south to settle along rivers.

There’s more to it than that—the 21-year drought from 1275-1296 went on unusually long, but it also came at a time when the attempted re-establishment of Chaco cultural organization at the confusingly-and-also-racist-assuption-ly-named Aztec Ruin in northern New Mexico was on the decline anyway, and the political situation of Mesa Verde caused instability and conflict with the extra drought pressures, and archaeologists still strenuously debate whether Athabaskans (ancestors of the Navajo and Apache) moved into the Four Corners region in this time or later, and whether that caused any push-out pressures…

But when I tell people I study Southwest archaeology, I still often hear, “Oh, isn’t it still a big mystery, what happened to the Anasazi? Didn’t they disappear?”

And the answer is. They didn’t disappear. Their descendants simply now live at Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Picuris, Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tamaya/Santa Ana, Kewa/Santo Domingo, Tesuque, Zia, and Ysleta del Sur. And/or married into Navajo and Apache groups. The Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans didn’t disappear any more than you can say the Ancient Romans disappeared because the Coliseum is a ruin that’s not used anymore. And honestly, for the majority of archaeological mysteries about “disappearance,” this is the answer—the socio-political organization changed to something less obvious in the archaeological record, but the people didn’t disappear, they’re still there.

452 notes

·

View notes

Photo

World Wildlife Day

The World is full of amazing creatures from every possible medium. From the birds of the air to the majestic whales of the sea, wildlife abounds in the most unusual and unexpected places. Wildlife benefits us in many ways and has since timed out of mind. World Wildlife Day is a day to remind us of our responsibilities to our world and the lifeforms we share it with.

Even though we might like to think so sometimes, humans aren’t the only living things on Earth. In fact, we’re far outnumbered by other living things, from animals and plants to fungi and bacteria. Wildlife isn’t just something that we passively observe; it’s part of our world, and something we need to care for. World Wildlife Day is your chance to celebrate all wildlife, from the smallest insect to blue whales. No matter what you love about wildlife, you can spend the day taking action to help protect it.

This day is all about raising awareness of wild flora and fauna across the world. Whether you love animals, you’re passionate about plants, or you’re concerned about climate change, it’s the day that you can use to educate yourself or others. You can celebrate the incredible biodiversity across the world and perhaps get out there to explore the huge range of flora and fauna the world has to offer. Celebrating World Wildlife Day is a must for anyone who loves our planet.

History of World Wildlife Day

On March 3rd, 1973 the United Nations General Assembly took a stand to protect Endangered Species throughout the world. Whether plant or animal, the importance of these species in every area of human life, from culinary to medical, could not be understated. At this time hundreds of endangered species were being threatened every year, and extinction was at a staggeringly high rate. CITES was put into place (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) to ensure that the world did not continue to hemorrhage species that would never be seen from again.

On December 20th, 2013 another step was taken to help spread awareness of the fragility of endangered species in the world. At its 68th session, the UN declared that each year World Wildlife Day would be dedicated to a new purpose and idea to help keep people abreast of the changing nature of our world, and the treasures we stand to lose from the animal and plant kingdom if we don’t take care.

Sometimes the day highlights an endangered animal or group of animals, while in other years, it has focused on a specific issue affecting the world of wildlife. Previous themes have included getting serious about wildlife crime and listening to young voices. World Wildlife Day is implemented by the CITES Secretariat, working together with relevant UN organizations. The day might not have been around for long compared to some others, but it’s already made a big impact. If you are passionate about the Earth and everything on it, celebrating is a must.

World Wildlife Day Timeline

1900 First wildlife conservation act is passed in the US

The Lacey Game and Wild Birds Preservation and Disposition Act is passed by Congress, which is the first legislation of its kind in the United States.

1948 International Union for Conservation of Nature begins

This is the first effort toward conservation that is supported by governments and societal organizations globally and its purpose is to encourage cooperation and the sharing of resources regarding conservation.

1961 World Wildlife Federation is established

A group of individuals who are passionate about protecting endangered species and places bands together to secure funding to this end.

1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

Negotiated in Washington DC, CITES is an international agreement between governments to protect the survival of various wild species by ensuring that trade does not threaten them. The signing takes place on March 3.

2013 First World Wildlife Day is celebrated

At its 68th session, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) declares March 3 as the day to raise awareness and and celebrate the wild animals all over the world.

How to Celebrate World Wildlife Day

You can celebrate World Wildlife Day on your own or with others, whether you just want to spend some time contemplating the majesty of nature or you want to spread the word about just how amazing the world’s wildlife is and how we can protect it.

The first thing that always comes to mind when we think about World Wildlife Day is heading out to our local zoo or botanical conservatory and reminding ourselves of the vast variety of life our world offers. If you have children, this can be one of the best ways to really introduce them to the wonders of the animal and plant kingdom. If you’re feeling particularly adventurous, an outdoor excursion with a book of local flora and fauna (That’s plants and animals) can help make that connection come even closer to home.

You could also spend the day spreading the word about the importance of our wildlife. If you love our planet, what better way to celebrate everything on it than to encourage other people to care about it too? You might create an event, get people to sponsor you or create some education materials. Choose a cause that matters to you, whether it is a local one or an international wildlife issue that you want to highlight.

Another way you can get involved is finding out what this year’s theme is by stopping by www.wildlifeday.org and finding ways to get involved. The website has a map of events that you can search to discover things to do near you, or you could add your own event to encourage others to get involved too. You can find a range of useful materials on the site too, including posters, logos, a social media kit, and a special action card that you can use to take photos. You can find suggestions for World Wildlife Day hashtags to use on social media or any materials that you create for your event too. Some of their suggestions for getting involved include running a competition, engaging with influencers, celebrities and politicians, and showing your appreciation for those who help to conserve wildlife every day.

There are few things as important as making sure that the world’s biosphere remains healthy, every time we lose a plant or animal, we have no way of knowing if a cure for a disease or some new medical breakthrough was lost with them. World Wildlife Day is your opportunity to do your part in preserving our world.

World Wildlife Day FAQs

Who started World Wildlife Day?

World Wildlife Day was started by the United Nations General Assembly which is the main policy-making sector of the assembly. Over the years it has become the most important annual event dedicated to the preservation of wildlife.

What is World Wildlife Day?

World Wildlife Day offers a simple opportunity to consider the animals and plants that humans share the planet with and to take action to help them in a variety of ways.

How to get involved with World Wildlife Day?

Taking part in World Wildlife day can be simple or more involved. The best ways to stay connected are to learn more, share the need with friends and family members, get to know threats to your local area, and host an awareness day at the office or at school.

Why do we celebrate World Wildlife Day?

The purpose of the celebration of World Wildlife Day is to raise awareness for the plight of and care for wild species that may be at risk and need to be protected.

When did World Wildlife Day start?

Although attention to wildlife has been active for more than 70 years, World Wildlife Day is a fairly modern celebration, officially started by the UN in 2013.

Source

#sea otter#pelican#lizard#California ground squirrel#Morro Bay#California#Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park#Utah#Arizona#Pacific Ocean#Elephant Seals of San Simeon#Northern elephant seal#Sagebrush lizard#Mesa Verde National Park#Arches National Park#Hopi chipmunk#wild horse#Lodgepole chipmunk#World Wildlife Day#3 March#animal#flora#fauna#summer 2022#original photography#travel#vacation#USA#Colorado#California toad

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voters on Navajo, Apache, and Hopi reservations helped swing Arizona for the Democrats in 2020. In response, the Republican governor and state legislature have curtailed ballot access for an already marginalized constituency.

To vote in the 2020 Presidential election, Frank Young rode a horse to the polls in Kayenta, Arizona. He was fifty-eight years old, and it was the first time he’d ever cast a ballot. Young is a citizen of the Navajo Nation, the country’s most populous Native American tribe, with nearly four hundred thousand members. About forty per cent of them live on a reservation that spans more than twenty-seven thousand square miles, an area larger than West Virginia. When we met, not far from his home in Rough Rock, a small Native community tucked under the mesa where his livestock grazes, he was wearing cowboy boots and a wide-brimmed black hat that sat low over a broad face weathered from years tending his animals. Two years ago, when his daughter convinced him that another Trump Presidency would be disastrous for Native Americans, Young decided that the best way to “protect the sacred” was to travel into battle the way his ancestors had. “We used to use horses to fight our enemies,” he said. “So my idea was, We’re gonna beat red. And we’d do it on horseback, and the horses will carry our culture and our democratic tradition and that will help us get it back.” Forty other riders joined him on an eight-mile ceremonial ride to vote at the local chapter house, the seat of the tribal government, which doubles as a polling site.

There are close to five million Native Americans of voting age in the United States, but only sixty-six per cent of them are registered to vote. Young said that he previously chose not to participate in American elections because the state and federal governments—he called them “colonizers”—had oppressed his people for centuries, extracting their timber, minerals, and ore, and leaving them to languish on land stripped of its value. “I just felt that our votes didn’t matter,” he told me.

It was an explanation that I heard a lot as I made my way across Arizona’s Navajo, Apache, and Hopi reservations, where human habitation is sparse, and flat-topped mountains preside over scrubby grass valleys. Native Americans have the highest rate of poverty in the nation—around twenty-seven per cent. As the pandemic took hold, the rate of unemployment soared to nearly twenty-nine per cent, reaching rates not seen in this country since the Great Depression. What this looks like on the ground is stunning: whole communities that live in substandard housing and, in 2022, lack electricity and running water. A former state legislator from the region said, “If you were told that there’s a Third World country in the middle of Arizona, you would not believe it. Yet people here still have to haul water, they have to use kerosene lanterns, and they have to use outhouses.”

Vida Begay, a Navajo woman from Indian Wells, Arizona, explained that people there had to strap two-hundred-gallon plastic water tanks—each of which can cost upward of two hundred dollars—to the back of their vehicles, filling them every few days, even in the depths of winter, when they have the tendency to freeze and crack open. On an Apache reservation, in Whiteriver, Lydia Dosela told me that there are members of her community who, because they can’t afford transportation, hitchhike to the town of Pinetop-Lakeside, twenty-five miles away, to work. “If it’s a choice between paying for gas and feeding their family, they are going to feed their family,” she said. As we toured her village, where stray dogs roam in packs, we passed the remains of a community center that had burned down after its copper wires were stripped by vandals. Dosela pointed to a small, windowless, unheated shed, the prefabricated kind that is meant to store tools and other equipment, and said that five people had been living in it.

Both Begay and Dosela are organizers with Northeast Arizona Native Democrats, hired to educate their communities about elections, garner support for Democratic candidates, and encourage voting. It is challenging work. Poverty and geography have combined to create structural barriers that thwart voting on sovereign Native lands. Poor people in the United States vote less than those with higher incomes, generally, but the remoteness of many communities and a general lack of reliable transportation make voting even more difficult for many Native Americans. In Navajo County, for example, which covers ten thousand square miles, there are only seventeen ballot drop boxes and twelve early-voting sites. Because local election offices are underfunded, the hours that those sites are open are often limited. The million-and-a-half acre Hopi Reservation has just three places where people can vote in person on Election Day. Early voting by mail helps Native voters, but post-office boxes can cost money that people may not have, and, in communities where there are not enough boxes to go around, residents sometimes have no choice but to get their mail delivered to towns that are hours away. There are only eleven post offices and sixteen additional sites that provide postal services across the entire Navajo reservation in Arizona. By contrast, West Virginia has seven hundred and twenty-five.

“Most of the time, when you have a post-office box, it makes voting a lot easier,” Allison Neswood, an attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, told me. “But, for Native communities, that’s not necessarily the case. The ones that are more rural, more remote, are farther from post offices, and the same obstacles to picking up the mail—Are the roads passable? Does my family have a vehicle that I can use?—also create barriers to voting.” (The majority of roads in Navajo Nation are unpaved and, in some parts of the reservation, only one in ten people owns a car. ) For tribal members who do not speak or read English and need language assistance, voting in person is the only option. But, for those who live in, for example, Teec Nos Pos, which is ninety-five miles from the nearest polling location, or for members of the Kaibab Paiute tribe, who have to travel two hundred and eighty-five miles to an early-voting site, voting in person may not be an option.

This year, Frank Young will once again ride his horse to the polls. His daughter, Allie, meanwhile, who is a program manager at the social-justice nonprofit, Harness, is sponsoring rides to register and to vote in other parts of Arizona, as well as in rural Black and Latino neighborhoods in Texas and Georgia. In her own community, Allie Young said, the show of civic engagement is meant to highlight a long history of voter suppression that continues to stymie Native Americans’ access to the ballot box. “The spirit of the horse represents strength and healing,” she said. “When we put our trust in the horse, it takes us where we need to go.”

Neither the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibits both the state and federal governments from denying (male) citizens the right to vote based on race, nor the Snyder Act of 1924, which explicitly granted citizenship to Native Americans, enfranchised them in Arizona, because the Constitution left it up to the states to decide who could vote. That right wasn’t fully extended to Indigenous people residing in Arizona until 1948. Even then, state-sanctioned literacy tests continued to block many Native Americans from registering, until the practice was struck down by a Supreme Court decision in 1970, five years after the Voting Rights Act abolished such tests nationwide. At a campaign rally I attended in Cameron, a place known for its abandoned uranium mines and high rates of cancer, Theresa Hatathlie, a Navajo woman running for State Senate, told the crowd, “For a long time, my mother and my father were not allowed to vote. So when they were finally given that right, whether it was the primary, or the general, or a special election, no matter the distance, whether it was raining, snowing, hailing, they went to vote. They reminded us that our people, our ancestors, encountered all this hardship and all these challenges just to vote.”

In 2020, Native Americans, who comprise six per cent of the Arizona population, voted in numbers never before seen and are largely credited with turning the state blue. According to the Associated Press, voters on the Navajo and Hopi reservations cast seventeen thousand more votes in 2020 than they had four years earlier, a majority of them for Biden, who won the state by about ten and a half thousand votes. With Trump promising to reopen the uranium mines, seizing sacred lands, and threatening to renege on the 1868 treaty that allowed Navajos to return to their ancestral homeland, the prospect of a Republican victory was existential. Jordan Harvill, the national program director for Advance Native Political Leadership, an Indigenous-led nonprofit that works to increase Native American political representation, told me, “After years of chronic underinvestment and voter suppression in Native communities, Native voters proved to be a decisive voting bloc in 2020.”

Rather than trying to appeal to Native voters, the Republican legislature and governor are, instead, actively working against them. The 2021 Supreme Court decision in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, a case that originated in Arizona, essentially neutered the section of the Voting Rights Act which prohibits states from passing laws that result “in a denial or abridgement” of the right to vote “on account of race or color.” In an opinion written by Samuel Alito, the Court’s conservative majority ruled that a law passed by the Arizona legislature, which made it illegal for a person to return the ballot of a friend or neighbor to a drop box or polling location, and disqualified voters who cast ballots in the wrong location, did not violate the Voting Rights Act. In an amicus brief, lawyers for the Navajo Nation pointed out, “Arizona’s ballot collection law criminalizes ways in which Navajos historically participated in early voting by mail. Due to the remoteness of the Nation and lack of transportation, it is not uncommon for Navajos to ask their neighbors or clan members to deliver their mail.” The 2022 election will be the first time ballot collection will be outlawed. There is little doubt that it will suppress the Native vote.

The law’s prohibition against out-of-precinct voting is also likely to undercut Native representation. Indian reservations tend to lack street addresses—by one count, fifty thousand properties do not have a fixed address—so when people there register to vote they have to draw a map of where they live in order to be assigned to the correct precinct. But, in practice, this often leads to voters being placed in the wrong precinct or not getting a precinct assignment at all. Although they may be able to cast a provisional ballot, Arizona rejects provisional ballots more frequently than any other state, and a substantial number of those rejected ballots are from Indigenous communities. And though the state now allows voters to identify their domicile with a code from Google that uses latitude and longitude to create a shareable digital address, numerous challenges, starting with Internet access and poor cell service, make this difficult to implement on reservations. Casey Lee, a thirty-three-year-old Navajo chef, started registering voters in and around Kayenta after the pandemic forced him to shutter his food truck; he told me that he now spends much of his time finding Google codes for his neighbors.

Since the Brnovich decision, the legislature has continued to pass more laws that target Native Americans and other people of color, who tend to vote for Democrats. Voters now must “cure” ballots when there is a mismatch between the signature on file and the signature on the ballot by 7 P.M. on Election Day—previously, they had seven days to do so—a hurdle that is likely to be too high for most people living on reservations. Another law bans local election offices from receiving funding from outside organizations, despite chronic underfunding of those offices, especially on reservations. Two additional laws make it easier for registered voters to be removed from the voter-registration database. “The colonization of our people is not over,” the former state legislator told me. “And one of the most glaring forms is attacking our voting rights. It is the easiest way to take the power away from Indigenous communities. And so it continues to happen.”

Redistricting has also hit Native communities hard. Districts that were created to empower Native Americans have now been sliced and diced to mute Native voices. District 2, for instance, now encompasses sixty per cent of Arizona’s landmass, including fourteen of the state’s twenty-two tribes. It is the most Native voting district in the state. But the newly drawn map adds a large Republican county, diluting the Native vote and giving the advantage to white Republicans. This new map is a direct legacy of the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby v. Holder, which effectively eliminated the provision of the Voting Rights Act that required the Justice Department to review changes to voting rules in states with a history of racial and ethnic discrimination before they could be adopted—what is known as “preclearance”—in order to insure that those changes would not harm minority voters. Without preclearance, states are now free to discriminate at will.

It was the twelfth day of early voting when I arrived in Dilkon, a town of fewer than two thousand people in the southwestern corner of the Navajo reservation. I followed a “Vote Here Today” sign to the town’s chapter house, an unassuming, dun-colored building on a dusty side road. The radio station KTNN, “the Voice of the Navajo Nation,” had set up in a parking lot a few hundred feet away, and was broadcasting a mix of country songs, tribal music, and exhortations to vote. Women crowded into a makeshift kitchen inside a horse trailer, preparing pozole, a pork-and-hominy stew. People arrived in fits and starts, most dropping off ballots before sitting down at folding tables to eat. Cindy Honani, an organizer from Mission for Arizona, a group funded by the Democratic Party, told me that it was the first time they had served hot food at a campaign event. The organizers hoped that both the stew and the presence of the radio station would draw a hundred people by day’s end. It was unseasonably cold—it snowed that morning—and people ate in a hurry and left. The mood was serious, not festive.

On the other side of the road was a neat row of compact houses. Begay told me that each one might have fifteen people living in it. That was the reason that COVID tore through the Navajo Nation, she said. (In May, 2020, there were more COVID cases per capita on the reservation than anywhere in the country.) “If one person got COVID, there was no place for them to isolate, so it went through the houses here like wildfire.” Masks are still required on the reservation, and, as I drove along Indian Route 15, it was not unusual to see hand-painted signs reminding people to wear them.

Missa Foy, the chair of the Navajo County Democrats, told me that, during the 2020 election, the pandemic had curtailed door-knocking and other traditional get-out-the-vote activities. “We had been on the ground since 2019, doing year-round deep canvassing, and when the pandemic hit we were not going to go out there and tell anyone to vote because it was just not the right thing to do,” she said. “So we came together as a team and said, ‘Let’s see who needs help. Let’s see what we can do.’ ” The group began connecting people with needed services, including meal boxes and P.P.E. “This wasn’t a branded effort,” Foy said. “We weren’t saying, ‘The Democratic Party is calling to save you.’ We just did it as community service.”

This effort was being run almost entirely by women. Later on, Foy and her colleagues decided to try to replicate it for voting, training community matriarchs on the ins and outs of voter registration and early voting, introducing them to candidates, and familiarizing them with the ten propositions that are on the midterm ballots. There are now a hundred and sixty-four matriarchs who have pledged to get their extended families to the polls. One of them, Lorraine Coin, a sixty-five-year-old Hopi woman I visited in Second Mesa, told me, “Women are the fire keepers of the house. When the kids come home from school, who is the first person they want to see? The mom, of course. And when the mom or grandmother or auntie talks, they are going to listen.”

Not long before I left Arizona, I drove around the town of Pinon with Suzy Etsitty, a medical-transportation driver who has worked to elect Democrats since 2014. Before that, she said, she “didn’t know crap about politics.” Now she regularly debates her Republican relatives, most of whom live off the reservation, about abortion, immigration, and inflation. And she can persuade her neighbors to register and vote because their lives depend on it. “I tell them that their social security is at stake,” she said. “That their rights are at stake. That we get funding from the government for our schools and our hospitals and for things like food stamps.”

Pinon is a dusty outpost of just over a thousand residents. As we drove, Etsitty, who lives out of town in a house built by her grandfather decades earlier, with her infirm mother and teen-age nieces, pointed out the public-school dormitory where she boarded until third grade. A housing development for the school’s teachers, many of whom have come to this isolated high desert from the Philippines, stood between the high school and a horse paddock. A sign welcoming visitors warned against social gatherings and listed other COVID prohibitions. Not far from the sole grocery store for nearly fifty miles, she showed me the post office where her midterm ballot was waiting for her, and the drop box where she would deposit it. “If Republicans get their way, they are going to do away with our voting rights,” she said. “That’s what really scares me.” ♦

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. (AP) — Federal penalties have increased under a newly signed law intended to protect the cultural patrimony of Native American tribes, immediately making some crimes a felony and doubling the prison time for anyone convicted of multiple offenses.

President Joe Biden signed the Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony Act on Dec. 21, a bill that had been introduced since 2016. Along with stiffer penalties, it prohibits the export of sacred Native American items from the U.S. and creates a certification process to distinguish art from sacred items.

The effort largely was inspired by pueblo tribes in New Mexico and Arizona who repeatedly saw sacred objects up for auction in France. Tribal leaders issued passionate pleas for the return of the items but were met with resistance and the reality that the U.S. had no mechanism to prevent the items from leaving the country.

“The STOP Act is really born out of that problem and hearing it over and over,” said attorney Katie Klass, who represents Acoma Pueblo on the matter and is a citizen of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma. “It's really designed to link existing domestic laws that protect tribal cultural heritage with an existing international mechanism.”

The law creates an export certification system that would help clarify whether items were created as art and provides a path for the voluntary return of items that are part of a tribe's cultural heritage. Federal agencies would work with Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians to outline what items should not leave the U.S. and to seek items back.

Information provided by tribes about those items would be shielded from public records laws.

While dealers and collectors often see the items as art to be displayed and preserved, tribes view the objects as living beings held in community, said Brian Vallo, a consultant on repatriation.

“These items remain sacred, they will never lose their significance,” said Vallo, a former governor of Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico. “They will never lose their power and place as a cultural item. And it is for this reason that we are so concerned."

Tribes have seen some wins over the years:

— In 2019, Finland agreed to return ancestral remains of Native American tribes that once called the cliffs of Mesa Verde National Park in southern Colorado home. The remains and artifacts were unearthed by a Swedish researcher in 1891 and held in the collection of the national Museum of Finland.

— That same year, a ceremonial shield that vanished from Acoma Pueblo in the 1970s was returned to the tribe after a nearly four-year campaign involving U.S. senators, diplomats and prosecutors. The circular, colorful shield featuring the face of a Kachina, or ancestral spirit, had been held at a Paris auction house.

— In 2014, the Navajo Nation sent its vice president to Paris to bid on items believed to be used in wintertime healing ceremonies after diplomacy and a plea to return the items failed. The tribe secured several items, spending $9,000.

—In 2013, the Annenberg Foundation quietly bought nearly two dozen ceremonial items at an auction in Paris and later returned them to the Hopi, the San Carlos Apache and the White Mountain Apache tribes in Arizona. The tribes said the items invoke the spirit of their ancestors and were taken in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

The STOP Act ties in with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act that requires museums and universities that receive federal funds to disclose Native American items in their possession, inventory them, and notify and transfer those items to affiliated tribes and Native Hawaiians or descendants.

The Interior Department has proposed a number of changes to strengthen NAGPRA and is taking public comment on them until mid-January.

The STOP Act increases penalties for illegally trafficking Native American human remains from one year to a year and a day, thus making it a felony on the first offense. Trafficking cultural items as outlined in NAGPRA remains a misdemeanor on the first offense. Penalties for subsequent offenses for both increase from five years to 10 years.

New Mexico U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, who introduced the House bill, said time will tell whether the penalties are adequate.

[...]

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

David Roberts, the author of the New York Times Op-Ed, is not telling us anything new, but he’s right in reminding us of the importance of this particular piece of land to Native Americans and to us. Excerpt:

The American West embraces more than its share of spectacular landscapes. But there’s nothing else quite like the vast swath of canyons, mesas, sandstone spires and arches that stretches some 80 miles from north to south in the southeast corner of Utah, ranging in altitude from sagebrush flats to pinyon-and-juniper forests and old growth stands of ponderosa pine and Douglas fir.

This is the wilderness of 1.35 million acres that President Barack Obama set aside in 2016 as the Bears Ears National Monument. One year later, cozying up to the oil-and-gas lobby and the right-wing crusade to turn federal lands over to “the people,” President Donald Trump eviscerated the monument, cutting it in size by 85 percent. During the past three years, the Bears Ears has hovered in judicial limbo, after Native American groups and environmental activists filed lawsuits claiming that Mr. Trump’s reduction exceeded his authority.

That wilderness is my favorite place on earth. I’ve written four books about the Bears Ears region, and until last year, when the pandemic stranded me in my Massachusetts home, I had made pilgrimages there every year for 28 years.

But around A.D. 1230, two or three thousand men, women and children flourished among those canyons and mesas, people we know today only by the taxonomic labels of Ancestral Puebloan and Fremont. Those inhabitants left behind a stunning array of mud-and-stone dwellings and panels of visionary rock art carved and painted on the cliffs, just waiting for latter-day vagabonds like me to discover.

If the Bears Ears is my favorite place on earth, it has an even deeper significance for the members of what became the Inter-Tribal Coalition — Navajo, Ute Mountain Ute, Hopi, Uintah and Ouray Ute and Zuni — who started the push for the Bears Ears back in 2010, championing the first successful national monument spearheaded by Native Americans. Mark Maryboy, the 65-year-old Navajo activist who got the ball rolling, told me: “Most tribes feel that North America is still theirs, that it’s been stolen from them by the government, by white people. We still worship in those lands. The Bears Ears is our church, our cathedral.”

Even as I plan my return to my favorite place on earth for the spring, I dread what I’ll find. But my personal loss is trivial compared with what anything short of complete restoration of the monument, and the oversight to keep it adequately protected from thoughtless desecration, will mean.

The original monument set aside by Mr. Obama comprises one of the most compelling landscapes in North America. But it’s more than that. With more pristine ancient dwellings, granaries and enigmatic galleries than any other wilderness in the United States, the Bears Ears constitutes an irreplaceable cultural treasure. We don’t have many of these places left to squander.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

sedona arizona history

Scenic Sedona Arizona History

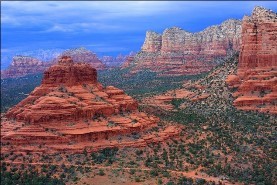

Sedona is located in the Upper Sonoran Desert of northern Arizona at an elevation of 4500 feet. Uptown Sedona (the part in Coconino County) and West Sedona (the Yavapai County portion) form the City of Sedona. Originally founded in 1902, the town was incorporated into a city in January 1988

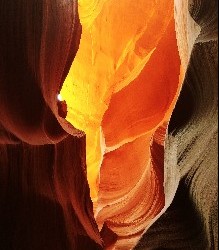

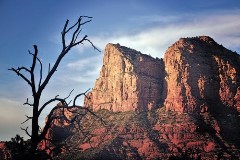

Southwestern America's stunning desert country, with its soaring red sandstone outcrops and formations, is a major attraction for visitors to the Arizona city of Sedona.

Millions of years ago, the area now known as Sedona was covered with sea. Ever so slowly with the gradual withdrawal of the waters combined with the earth’s powerful forces of upheaval, this masterpiece of nature was created. Sculpted by wind and erosion, the crimson monuments of vividly colored mesas were formed. Today Sedona is brightly adorned with panoramic beauty so unique it doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world.

The spectacle of Sedona is crystal clear, but the history of ancient inhabitants is a bit blurred over the last 10,000 years or so. Artifacts, prehistoric dwellings, petroglyphs and other archaeological evidence confirm that various civilizations lived in the Sedona area beginning in about 8,000 BC. Historians and researchers somewhat disagree on timelines of when these original “Native Americans” came, why they left and what happed to them.

Most believe that the first inhabitants migrated across land connecting Ancient Asia with North America. These nomads are now referred to as “Paleo Indians”. Evidence suggests that the “Anasazi Indians” came next followed by the Hohokam during the period of 500 AD to 700 AD.

The name Anasazi was coined by the Navajos and means “The ancient ones who weren’t us”. For mysterious reasons, the Anasazi left the area. The Hohokam introduced irrigation farming which is evidenced by ancient canals that still exist today.

The Sinaqua Tribe which means “without water” in Spanish came to the Sedona area about 900-1000 AD. The Sinaquans are known to have been “dry farmers” (hence their name) and traded with other native groups some of which extended into South America. Many archaeologists believe that a gigantic volcanic eruption at about 1060 AD which formed the Sunset Crater forced the Sinaquans to flee the area. Others conclude that new war-like tribes attacked and forced them out for an extended period. Some evidence suggests that the volcanic ash created more fertile soils which enticed the return of the Sinaquans followed by the return of Anasazi remnants that taught the Sinaquans to build multi-storied dwellings into cliff-sides as defensive mechanisms. Some of these pueblo dwelling ruins still stand today at “ Montezuma Castle” and the “ Palatki Ruins

Quite suddenly around the 1300s, they seemed to have abandoned the area quickly. Some theorize that most were eliminated by other nearby inhabitants with other Sinaquans fleeing to subsequently meld with native inhabitants farther to the north.

Perhaps over an extended period of time, tribal segments branched off and integrated with other tribes and became the prehistoric ancestors of today’s various Indian Tribes in various parts of Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. Many researchers believe the Hopi Indians are descendants of the ancient Anasazi.

Who knows for sure what happened to the first “citizens of Sedona”, the Paleo, Anasazi, Hohokam and Sinaqua. Did they see the same Sedona we see today? Was it as beautiful then as it is today? That also we’ll never know. But we all are thankful for the treasures of artifacts they left us to enjoy and this spectacular place now called Sedona for the whole world to experience.

The quest for gold and silver riches brought Spanish explorers to the Sedona area in about 1583. It is believed that Antonio de Espejo was the first European to set foot in Sedona and what a sight it must have been. Antonio never discovered gold or silver but did discover the beauty that took nature millions of years to create. As did the first inhabitants, the Spanish left their contributions to history as well in the form of Colonial Architecture and descendents that have made a historical impact on all of Arizona.

Near the beginning of the 1900s, there were few Caucasian squatters in the Sedona area. One was T.C. Schnebly and his wife. T.C. petitioned the U.S. Postal Service to make a postal stop in the area. The post office needed a name and he suggested several which were rejected by the Postmaster General as being too long. Schnebly’s brother suggested submitting the name of T.C.’s wife. Her name was “Sedona” and the rest is history.

Apples and peaches were Sedona’s first main industry. Frank L. Pendley homesteaded land alongside Oak Creek and harnessed the water to irrigate his orchards. Today the original homestead is owned by the State Park system as “ Slide Rock State Park”. Yes, apple trees still produce delicious fruit that is sold to the visiting public to help cover the cost of administering the park. Old historic structures still reside in the park as a continuous reminder of years past.

Sedona was discovered by Hollywood in the 1950s. Its startling beauty and unique backdrop attracted movie producers that used Sedona as the setting for over 70 films. The Sedona secret was out. Gradually, Sedona became the getaway home of some of the world’s rich and famous.

Today, tourism is Sedona’s primary industry attracting over 4 million visitors a year second only to the Grand Canyon as Arizona’s most visited destination.

Dwell upon the ancient history of past civilizations. Imagine if they were here today to take one peek at what they discovered thousands of years ago. The coexistence of architecture that artfully blends with nature. The game of golf under the blue skies. The luxury resorts along the creek and mountainsides. The awe-inspiring attractions that entices the senses. And the joy of seeing their own ancient artifacts that confirms their prehistoric existence.

Thanks Paleo. Thanks Anasazi, Hohokam and Sinaqua. You served Sedona and the world well.

Photos on this article are from pexels and other net free sourcrs

this article is in the public domain

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Adobe Dwellings in Mishongnovi, Hopi Second Mesa, Navajo Country - 1900

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Navajo Nation Division of Economic Development & Hopi Delegation Initiate Partnership Talks Published June 25, 2019 SAINT MICHAELS, Ariz. – The Division of Economic Development and representatives from the Hopi communities of the First Mesa Consolidated Village met last Tuesday in Window Rock to begin discussing an economic development partnership between the two tribes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Ed Kabotie : "The use of reclaimed water on the San Francisco Peaks is an abomination and a continuance of centuries of oppression from the capitalistic paradigm. The sacred lands that we call the Colorado Plateau carry the footsteps and voices of our ancestral mothers and fathers. We were led to the places that we live to understand the truth of life. Dry farming and dependence upon the answers to our prayers for rain made our hearts humble and kept our mind's eye focused on the spiritual. Through threatened throughout the centuries, our culture's greatest assault began in the last decade of the 1800's when our fathers were imprisoned on Alcatraz island for refusing to send their children to be educated in the boarding school system of 'Kill the Indian, Save the Man'. My great-grandfather, Loloma'yaouma, was arrested in 1906 for refusing to send my grandfather to school. My grandfather ran away from school till he was 15, and then was sent to the Santa Fe Indian School. My father was sent to Lawrence, Kansas. I graduated from the same boarding school as my grandfather. During this calculated assault on our families and homes, our communities' leaders were usurped and replaced by 'constitutional governments' for the purpose of mineral exploration on our lands. There are over 500 open pit uranium mines that exist today on the Navajo Nation. The World's Largest strip mining operation between 1970 and 2005 depleted a pristine aquifer system that could and should have provided water for our posterity for generations. Today, the majority of those that have running water in their homes in Hopi can't drink from it because of arsenic contamination. The only currently existing uranium mine today in the state of Arizona is the Grand Canyon Mine which threatens the health of the Havasupai nation. The only operating commercial mill in the United States is the White Mesa Mill which threatens the water systems of the Ute Mountain Ute nation! When does the desecration and disregard for life end? ...The Arizona Supreme Courts ruling that the Hopi Tribe cannot claim special damage on the lands managed by the Arizona Snowbowl on the San Francisco Peaks is yet another manifestation in the ongoing story of Cultural Imperialism on the Colorado Plateau."

#sacred lands#sacred land#water is sacred#genocide#indegenous#indegenous land defenders#water is life#water protectors#native lives matter

34 notes

·

View notes