#HIV response

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The path to ending AIDS – Progress report on 2025 targets and solutions for the future.

On the occasion of the UNGA78 AIDS review, UNAIDS will hold a briefing, "The path to ending AIDS – Progress report on 2025 targets and solutions for the future".

The briefing will complement the debate in the GA Plenary and provide an opportunity for a more direct and interactive exchange between senior-level representatives of UNAIDS, Member States and civil society. It will focus on the progress made towards the 2025 global targets that will pave the way towards ending AIDS as a global public health threat by 2030 and the urgent action required for addressing the remaining gaps and challenges, as well as discuss key issues around the sustainability of the HIV response and maintaining the gains in the future.

Speakers:

Angeli Achrekar, UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director and an Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations

Jaime Atienza, Director, Equitable Financing, UNAIDS

Watch the UNAIDS: The Path to Ending AIDS!

#The path to ending AIDS#Solutions for the future#HIV response#public health treat#unaids#unga78#hiv/aids#Joint united nations programme HIV-AIDS#hiv prevention

0 notes

Text

The decriminalization of HIV enhances the HIV response because the removal of fear of prosecution helps people to access health services.

POSTCARD VIII- Zero Discrimination Day 2024; March 1st.

#access health services#zero discrimination day#1 march#campaign#decriminalization#UNAIDS#HIV response#Fear of prosecution#postcard#protect everyone's rights#protect everyone's health

0 notes

Text

He’s Coming to Me is a comedy…unless you think about about it for more than 3 seconds…about how Med and his untended grave represents a lost queer generation in the 90s…how Thun’s only queer mentor to help him out of his own cemetery of secret pain and longing is a ghost…a ghost who could’ve lived if greed didn’t willfully keep the medicine he needed out of his reach…

He’s Coming to Me is a comedy…unless you think about how Med resigned himself to never leave the graveyard and to never be seen by anyone because of the way his family abandoned him in his condition…how he accepted his eternal state of loneliness…how even after he’s freed, Med depends on Thun’s desire for his touch because death has changed him forever and he can’t simply act on his own desires alone…

He’s Coming to Me is a comedy…unless you think about Thun’s refusal to give up on the people who are supposed to be lost…his refusal to give up on those who want to give up on themselves…unless you think about the second-life Med gets to live…how genuinely happy Thun and he are to have each other despite the limits to their intimacy, despite those who can’t see their love, despite the knowledge that some day it will end…about how they love each other perhaps more deeply because they both recognize how preciously brief anyone’s life on earth is before they’re reborn and the search for those small moments of love happen again

Yes, He’s Coming to Me is a comedy 🥺🥺🥺…😭

#what I’m saying is that Thun went into public health law#the hiv allegory is just unparalleled#hctm#he’s coming to me#ohm pawat#singto prachaya#aof noppharnach#he’s coming to me the series#queer history#bl drama#thai bl#and in fact Thailand actually had one of the better national responses to the crisis according to the reports I read

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

❤️🤍💙 Red, White and Royal Blue. Representation matters

#representation matters#red white and royal blue#ive watched so many reaction vids from people in the gay community and hets and all the responses from the community have been positive#so many gay people said finally they have a movie about their community that isn't tragic isnt about HIV and shows gaysex#that is loving tender and beautiful#im happy for the community to get a movie like this finally#Nicholas and Taylor were great in their portrayals bringing charm humour and sincerity to their characters#im not in the community but I understand how important representation is#and also I love romcoms and there are so few well made romcoms out there#and this is one of my favourite romcoms now#rwrb#romcoms#taylor zakhar perez#nicholas galitzine#lbgt representation#lbgtq community#Matthew Lopez#mine

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

twitter keeps showing me posts about how people who take prep are whores?? and like getting aids/hiv is some morally reprehensible act that means you’re awful?? what is wrong with yall 😻

#my grandma died largely due to HIV#i know you can’t die OF it but like#the complications#like#shut the fuck up???#taking prep is a responsible sex practice bc you don’t know for sure what people have#or what you may have unless you get tested regularly#and having HIV/AIDS is not some moral failure#the puritan mindset has got to go#we need to talk more about safe sex and less about abstinence only or shaming people who have casual sex PLEASE#bimbo thinks(for once)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#HBV#HIV-1#hepatic flare#antiretroviral therapy#HBsAg seroclearance#HBV/HIV co-infection#immune reconstitution#liver enzymes#viral clearance#chronic hepatitis B#HIV treatment outcomes#liver health#ART-induced immune response#infectious diseases#hepatology#co-infection management#liver function monitoring#viral hepatitis#immune response dynamics#public health.#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

A two-dose schedule could make HIV vaccines more effective

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/a-two-dose-schedule-could-make-hiv-vaccines-more-effective/

A two-dose schedule could make HIV vaccines more effective

One major reason why it has been difficult to develop an effective HIV vaccine is that the virus mutates very rapidly, allowing it to evade the antibody response generated by vaccines.

Several years ago, MIT researchers showed that administering a series of escalating doses of an HIV vaccine over a two-week period could help overcome a part of that challenge by generating larger quantities of neutralizing antibodies. However, a multidose vaccine regimen administered over a short time is not practical for mass vaccination campaigns.

In a new study, the researchers have now found that they can achieve a similar immune response with just two doses, given one week apart. The first dose, which is much smaller, prepares the immune system to respond more powerfully to the second, larger dose.

This study, which was performed by bringing together computational modeling and experiments in mice, used an HIV envelope protein as the vaccine. A single-dose version of this vaccine is now in clinical trials, and the researchers hope to establish another study group that will receive the vaccine on a two-dose schedule.

“By bringing together the physical and life sciences, we shed light on some basic immunological questions that helped develop this two-dose schedule to mimic the multiple-dose regimen,” says Arup Chakraborty, the John M. Deutch Institute Professor at MIT and a member of MIT’s Institute for Medical Engineering and Science and the Ragon Institute of MIT, MGH and Harvard University.

This approach may also generalize to vaccines for other diseases, Chakraborty notes.

Chakraborty and Darrell Irvine, a former MIT professor of biological engineering and materials science and engineering and member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, who is now a professor of immunology and microbiology at the Scripps Research Institute, are the senior authors of the study, which appears today in Science Immunology. The lead authors of the paper are Sachin Bhagchandani PhD ’23 and Leerang Yang PhD ’24.

Neutralizing antibodies

Each year, HIV infects more than 1 million people around the world, and some of those people do not have access to antiviral drugs. An effective vaccine could prevent many of those infections. One promising vaccine now in clinical trials consists of an HIV protein called an envelope trimer, along with a nanoparticle called SMNP. The nanoparticle, developed by Irvine’s lab, acts as an adjuvant that helps recruit a stronger B cell response to the vaccine.

In clinical trials, this vaccine and other experimental vaccines have been given as just one dose. However, there is growing evidence that a series of doses is more effective at generating broadly neutralizing antibodies. The seven-dose regimen, the researchers believe, works well because it mimics what happens when the body is exposed to a virus: The immune system builds up a strong response as more viral proteins, or antigens, accumulate in the body.

In the new study, the MIT team investigated how this response develops and explored whether they could achieve the same effect using a smaller number of vaccine doses.

“Giving seven doses just isn’t feasible for mass vaccination,” Bhagchandani says. “We wanted to identify some of the critical elements necessary for the success of this escalating dose, and to explore whether that knowledge could allow us to reduce the number of doses.”

The researchers began by comparing the effects of one, two, three, four, five, six, or seven doses, all given over a 12-day period. They initially found that while three or more doses generated strong antibody responses, two doses did not. However, by tweaking the dose intervals and ratios, the researchers discovered that giving 20 percent of the vaccine in the first dose and 80 percent in a second dose, seven days later, achieved just as good a response as the seven-dose schedule.

“It was clear that understanding the mechanisms behind this phenomenon would be crucial for future clinical translation,” Yang says. “Even if the ideal dosing ratio and timing may differ for humans, the underlying mechanistic principles will likely remain the same.”

Using a computational model, the researchers explored what was happening in each of these dosing scenarios. This work showed that when all of the vaccine is given as one dose, most of the antigen gets chopped into fragments before it reaches the lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are where B cells become activated to target a particular antigen, within structures known as germinal centers.

When only a tiny amount of the intact antigen reaches these germinal centers, B cells can’t come up with a strong response against that antigen.

However, a very small number of B cells do arise that produce antibodies targeting the intact antigen. So, giving a small amount in the first dose does not “waste” much antigen but allows some B cells and antibodies to develop. If a second, larger dose is given a week later, those antibodies bind to the antigen before it can be broken down and escort it into the lymph node. This allows more B cells to be exposed to that antigen and eventually leads to a large population of B cells that can target it.

“The early doses generate some small amounts of antibody, and that’s enough to then bind to the vaccine of the later doses, protect it, and target it to the lymph node. That’s how we realized that we don’t need to give seven doses,” Bhagchandani says. “A small initial dose will generate this antibody and then when you give the larger dose, it can again be protected because that antibody will bind to it and traffic it to the lymph node.”

T-cell boost

Those antigens may stay in the germinal centers for weeks or even longer, allowing more B cells to come in and be exposed to them, making it more likely that diverse types of antibodies will develop.

The researchers also found that the two-dose schedule induces a stronger T-cell response. The first dose activates dendritic cells, which promote inflammation and T-cell activation. Then, when the second dose arrives, even more dendritic cells are stimulated, further boosting the T-cell response.

Overall, the two-dose regimen resulted in a fivefold improvement in the T-cell response and a 60-fold improvement in the antibody response, compared to a single vaccine dose.

“Reducing the ‘escalating dose’ strategy down to two shots makes it much more practical for clinical implementation. Further, a number of technologies are in development that could mimic the two-dose exposure in a single shot, which could become ideal for mass vaccination campaigns,” Irvine says.

The researchers are now studying this vaccine strategy in a nonhuman primate model. They are also working on specialized materials that can deliver the second dose over an extended period of time, which could further enhance the immune response.

The research was funded by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the Ragon Institute of MIT, MGH, and Harvard.

#antibodies#antigen#approach#Biological engineering#Cancer#cell#Cells#challenge#Chemical engineering#development#Diseases#drugs#effects#engineering#experimental#Future#Giving#harvard#Health#hiv#how#humans#immune response#immune system#immunology#infections#inflammation#Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES)#it#Koch Institute

0 notes

Text

"Meet "Doctor" Demetre Daskalakis.

Deputy Coordinator of the White House National Monkeypox Response Team and Director of the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention in the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention since 2020

Yet you can't find his birthdate on Wikipedia.

Hmm... the Good Doctor, alright. Up is Down. Black is White. Good is Bad.

#“Doctor” Demetre Daskalakis#Deputy Coordinator of the White House National Monkeypox Response Team#Director of the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention in the National Center for HIV/AIDS#Viral Hepatitis#STD#and TB Prevention since 2020#Satanic Deatj Cult Is In The White House#Sabbatean Frankists#Biden#Kamala Harris

0 notes

Text

To my Asian, European, African, and Canadian friends...do y'all wanna know how the United States found itself under a fascist, Hitler-loving dictator named Donald Trump?

In another post, I started my timeline in 1980. The year I was born. But, it was also a turning point in US politics.

First, let me share my credentials.

- Bachelors of Arts - History

- Juris Doctor - Public Interest Law (Critical Race Theory)

- Masters of Philosophy (research degree) - Sociology (Race, Ethnicity, Conflict)

Just recently, we buried President Jimmy Carter, who was the president, when I was born. Jimmy was from Georgia, like my grandmother, and he came from a Southern Baptist background. Southern Baptists are known for being very conservative Christians who did not support abortion.

Jimmy, despite that background, actually supported LGBTQ rights by lifting a federal ban. He supported Roe v. Wade which protected access to abortion. And, he established the federal Department of Education.

However, Jimmy had an antagonistic relationship with Congress, and that alienated several Democrats, including Ted Kennedy, who was the brother of John F. Kennedy, a president who was assassinated.

The Kennedy family has an established name brand due to JFK and Robert F Kennedy (another brother and JFK's attorney general who was also assassinated). Ted was the younger, drunken brother who caused the accidental death of a college friend.

In 1980, Ted challenged Jimmy for the presidency even though they were both Democrats. Jimmy has the incumbent shouldn't have faced a challenge from his own party, but he had just been that bad.

So, this internal strife weakened the Democratic Party entering the 1980 election. In that same year, Jimmy boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Russia due to Russia's invasion of Afghanistan. Furthermore, there was a recession.

The Republican Party nominee was a former Hollywood actor turned politician named Ronald Reagan. Ronald was the governor of California and was trailing Jimmy in the polls until a presidential debate in which Ronald used his acting skills to make Jimmy seem incompetent.

Ronald believed in "trickle down economics." He believed that if the wealthiest people were taxed less, then they would spend more, thus boosting the economy and allowing prosperity to "trickle down" to the working & Middle class.

He also believed in increased military spending as this was the height of the Cold War with Russia. My own parents voted for Reagan because my dad was in the military.

Instead of trickling down, the wealthy just grew wealthier. Republicans continued to lower taxes for these individuals and businesses, so the money never trickled down. Social services were underfunded & unemployment increased. Reagan's response was to blame Black "welfare mothers" for abusing the system.

Republicans latch onto this. They implement work requirements for government assistance and make it harder for folks to pull out of poverty. As a result, a wealth gap separated white folk from the rest. White folk felt their hard earned money was supporting lazy white & Black folk, so they continued to constrict welfare programs.

[Section added] During Reagan's term, an unknown illness is killing young, gay Black & Latino men. It's AIDs. Reagan deemed it a gay disease that only affects gay people, so no funding is allocated to study this disease. It's viewed as retribution for their homosexua lifestyle. However, overtime, they learn about HIV once non-gay men were infected. Children die from the disease because blood is not tested for it, so some are born from it through their mothers while others were given transfusions.

Under Reagan, the Fairness Doctrine ends. Under this doctrine, news agencies had to report both sides of an issue. Because of this, television stations can now present one side. Fox News opens as a conservative network.

Ronald is well-loved by white folk. He gets elected to two terms. By the end of his term, the economy has recovered, and white folk are prospering. Then, his VP, George H.W. Bush, is elected.

Under George I, the Cold War ends, but we have the Gulf War in Kuwait. He signs trade agreements that result in several American companies, namely the auto industry, to shutter their doors and build factories overseas. This is due to a change in tariffs!

Millions of Americans lose their jobs as factories close. Detroit, as the leading auto manufacturer city, is devastated. Back in the 90s, Detroit was the 4th largest US city after Chicago. These factory closures hit the Midwest, especially hard.

This makes Bush unpopular. He is challenged by a young, charismatic Democrat named Bill Clinton.

Bill was a southerner like Jimmy, but Bill was a very well-known ladies' man. Bill appeals to Black Americans, though, and that allows him to defeat George.

Bill continues expanding trade agreements. He's a fiscal conservative despite being a Democrat, and under Bill, military spending is reduced.

[Section added] The rise of AIDs leads to further hate directed at the LGBTQ. During the 90s, several queer people are murdered. One such kid was Matthew Shepard. A college kid in Wyoming, he is beaten by a gang of white men. His family was terrorized so much, that they couldn't bury him because of fears his grave would be desecrated.

[A white woman Bishop in DC invites Shepard's parents to bury him in their graveyard. That Bishop is Marian Edgar Budde, the same Bishop who gave Trump his inaugural sermon this past week. She pleaded for Trump to have mercy on the queer community because she was the Bishop who buried Shepard!]

Bill is a popular president. The economy is booming, but he's still a lady's man, and he gets in trouble with a college intern.

This scandal adversely impacts the last few years in office so much so that his VP, Al Gore, loses the presidency to George W. Bush.

George Bush won the Electoral College while Al Gore won the popular vote. There was such a tiny margin that there were numerous recounts because of faulty ballots (hanging chads). Eventually, the Supreme Court intervenes and tells them to stop the count and certify George as president.

George II is the son of George I.

George II is a popular Texan with swagger. He wants to build up the military once again.

Clinton left a surplus of money, so what did George II do? He implemented tax cuts for the wealthy. That damned "trickle down economics" again. The wealthy get wealthier, increasing the wealth gap between white folks and everybody else.

They cut taxes while cutting social services. One of his biggest "achievements" was a restructuring of our educational system called "No Child Left Behind."

NCLB emphasizes test scores. School administrations are penalized if they don't meet these standards. They lost funding, so electives such as home economics, art, Music, etc are trimmed to make room for these test standards. By this time, my dad has retired from the military and is a school principal, and I remember the stress of trying to meet these standards.

These standards emphasize STEM at the expense of liberal arts. This is happening just as the internet becomes available to all.

Amazon opens as an online used book store. Facebook is started as a college message board. There's a tech boom, so everyone is being pushed into tech fields. Liberal arts education was devalued.

During his term, 9-11 happens. We declare war on Afghanistan. Islamophobia spikes. Fox News helps drive this narrative. Christianity is now being pushed into schools, whereas schools were previously secular.

[Section added] In 2004, the assault rifle ban was lifted. Now we are seeing a dramatic spike in school shootings. The Far Right embraces the expansion of the 2nd Amendment.

Then, we go to war in Iraq.

We aren't quite sure why we're at war with Iraq. We overthrow Suddam Hussein (from the Gulf War). George declares victory, then terminates the Iraqi Army.

This triggers an insurrection. Massive casualties are coming out of Iraq. The war in Afghanistan is overshadowed.

George serves two terms, but his VP is so unpopular that he doesn't run for president. Instead, the Republican nominee is John McCain.

Two Democrats fight for the nomination. Hillary Clinton, the wife of Bill, and Barack Obama.

Barack was a young, biracial Senator from Illinois. I attended law school in Illinois, and one of my classmates had been his legislative aide. I met Barack twice while a student. The first time, he had come to campus to propose a college-savings account. After his press conference, I latched onto his arm and refused to let go until he heard me, and I explained that his proposal was unrealistic because it assumed that a single mother would have the resources to save for an education when it was more likely her money would go towards groceries & rent or other immediate needs. (Fast forward two-three years, and the dude is repeating my line during the State of the Union! I had changed his mind!)

Barack beats Hillary for the nomination. He defeats McCain and is sworn in as the 1st black (not Black) president.

Obama is popular and well-loved by most Americans. Under his tenure, gay marriage is legalized.

Fox News triples down on their hatred.

Their network booms. They push Islamophobia 24/7. Highlight the fact that Obama's father was Muslim and that his middle name was Hussein.

Older Americans are watching program after program of this negativity. A movement starts called the Tea Party movement, which positions itself as a fiscally conservative movement. A bankrupt slumlord with a reality TV show gains popularity with these folks.

I wrote my master's dissertation on the Tea Party movement. It's called "Jesus and the White Man."

Donald Trump

Donald latches onto the Islamaphobia. He calls Barack by his middle name and questions his birth certificate. Donald grows popular with older Americans.

At the end of Obama's term, the son of VP Biden dies. This devastated Biden. He had lost his infant daughter & first wife in a car accident. He decides not to run for president.

Obama supports Hillary.

It is now Hillary v. Trump.

Trump pushes misogyny and Islamaphobia. Hillary is Bill's wife and a woman. She is the most qualified presidential candidate to ever run (at that time).

During Obama's last year in office, Justice Antonin Scalia* dies. Obama has the privilege to nominate that next Justice, but Mitch McConnell stalls through the election.

But older white Americans were barely okay with a black president. They were not about to let a woman serve as President. At the same time, an organization called Cambridge Analytica began to fine-tune an ultra conservative agenda.

With the help of Russian intelligence, they use Facebook ads to try to persuade voters to support Trump. They succeeded with white folk, but they did not succeed with the Black vote.

Russians used African bot farms in order to try to persuade Black Americans to support Trump. We rejected him at 90%.

Donald wins the Electoral College but not the popular vote.

Donald is a corrupt and ineffectual president. He tried to bribe foreign leaders and shared US intelligence with Russia.

However, as a populist, he latches onto the Christian Right. He nominates 3 Supreme Court Justices who lie during their confirmation hearings. These Justices will ultimately vote to overturn Roe v. Wade.

The Christian Right love this. But then COVID hits and the incompetence of Donald leads to millions of deaths. These Christian folk refuse to get vaccinated or wear masks.

Donald is an unpopular president and ranks as the worst president of all time.

Biden challenges him and wins.

Donald refuses to accept that he lost, so he organized an attempted coup. January 6th.

He's impeached. Twice.

McConnell refuses to take the step to have him permanently barred from office.

Biden takes office when COVID is still rampant. The Christian Right continue to push their agenda, seeking to remove protections for the LGBTQI.

Right wing media generates a lot of money. Podcasters jump on the bandwagon. Red pill content spills into the mainstream.

Kids who were isolated during COVID are now at home watching Joe Rogan & Theo Von. They spend hours upon hours on TikTok.

But unbeknownst to these kids is the history of Russian interference.

Schools emphasize STEM. They don't emphasize liberal arts or social sciences such as history or literature. The literacy rate plummeted to an all-time low. The average white American's reading level is at the 4th grade. They aren't able to engage in critical thinking.

They don't know the history of the Spanish Influenza. They don't know the history of a trade war that triggered the Great Depression. They don't know that our government has imprisoned citizens in internment camps. They don't know Hitler's rise to power.

In fact, Fox News frequently features individuals who deny the Holocaust.

Russia move their troll farms from Facebook to TikTok, where the algorithm serves as an echo chamber. Uneducated, illiterate folks gobble up 30-second videos but can't be arsed to watch anything over 5 minutes so complex issues are stripped down to sound bites.

The algorithm pushed right-wing fascist talking points. They rehabbed Donald while shifting Gen Z to the far right. They do not know how to verify information for themselves, so they gobble up misinformation and disinformation.

If a TikTok creator has millions of followers with thousands of views and likes, these kids assume that that info is factual. They do not vet shit for themselves.

Russia pushed anti-American propaganda that posed as pro-American talking points. Pushed isolationism. Pushed anti-democratic rhetoric. In fact, one of their greatest accomplishments is convincing Gen Z and uneducated, white Millennials into thinking we aren't a democracy.

We are a fucking Democratic Republic. Our constitution begins with: "We the people".

So, because of TikTok, Trump won.

That's why Biden was pushing for it to be banned before the election. The algorithm was being corrupted. But folks couldn't part from their addiction.

Folks who had been anti-Trump just 5 years ago are suddenly Trump supporters. They were brainwashed.

So, how did we get here?

We got here because most Americans are fucking STUPID.

#ask auntie#ask me anything#black girl magic#donald trump#elon musk#maga#barack obama#hillary clinton#jimmy carter#biden#kamala harris#democrats#republicans#US History#american history#American politics#US politics#LGBTQ#gay marriage#trans rights#cambridge analytica#russian interference#troll farms#facebook#twitter#tiktok#meta#amazon#ronald reagan#trump deportations

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

How community-led interventions are central to achieving the end of AIDS and to sustaining the gains into the future.

youtube

We have an extraordinary, historic opportunity. We can end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 and sustain these gains in future decades. We even know how—by enabling the leadership of the communities at the frontlines.

This report shows how community-led interventions are central to achieving the end of AIDS and to sustaining the gains into the future. This report shines a light on the underreported story of the everyday heroes of the HIV response. But it is much more than a celebration of the achievements of communities. It is an urgent call to action for governments and international partners to enable and support communities in their leadership roles.

People living with or affected by HIV have driven progress in the HIV response—reaching people who have not been reached; connecting people with the services they need; pioneering innovations; holding providers, governments, international organizations and donors to account; and spearheading inspirational movements for health, dignity and human rights for all. They are the trusted voices. Communities understand what is most needed, what works, and what needs to change. Communities have not waited to be handed their leadership roles— they have taken the roles on themselves and held fast in their insistence on doing so. They have applied their skills and determination to help tackle other pandemics and health crises too, including COVID-19, Ebola and mpox. Letting communities lead builds healthier and stronger societies.

#let communities lead#world aids day#unaids#hiv infection#people living with hiv#hiv prevention#community led hiv responses#health community based organizations#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

from the number of asinine complaints about how "voting is NOT a form of harm reduction" because harm reduction is for ADDICTS! ONLY! I'm seeing around... all coming from OP blogs I don't recognize and which otherwise don't have much presence... well, that coordination alongside the timing of US politics sure feels like the Russian troll bots agitating again. (Yes, they absolutely infested Tumblr; I think @ms-demeanor had a great post about what the bots looked and felt like somewhere that I will have to try and track down tomorrow.)

The thing is, if you actually do know harm reduction well, the complaint makes no sense. It's not as if the origin of harm reduction is a secret or especially hard to find out more about. I am not exactly an expert in the field: I have a educated layperson's interest in public health and infectious disease, I'm a queer feminist of a certain age and therefore have a certain degree of familiarity with AIDS-driven safer sex campaigns, and I'm interested in disability history and self advocacy (and I would in fact clarify harm reduction as a philosophy under this umbrella). So I have about twenty years of experience with harm reduction as a philosophy basically by existing in communities whose history is intertwined with harm reduction, which means I know it well from many different angles, and I know how the story of the philosophy is generally taught.

See, this is a story that starts, as so many stories do, in the 1980s with something monstrous President Reagan was doing. In this case, it was the AIDS epidemic, and Reagan refusing to devote any money or time to what eventually became called AIDS (rather than the original GRIDS, which came with its own baked in homophobia). Knowing themselves abandoned by society in this as in all things, and watching as friends and loved ones died in droves, queers and addicts are two communities who see that they are the only resources that they collectively have to save each other's lives. Queers know that sex, even casual sex, is an important part of people's lives and culture... and people aren't going to stop doing it even if there's a disease, so how can it happen safely? Condoms. Condoms every time, freely available, easy and shameless, shower them on people in the street if you have to. (And other things: this is the origin of the concept of "fluid bonding", for example... both of which were concepts that were immediately adopted in response to COVID, like outdoor socially distsnced greetings and masks and "bubbles." That wasn't an accident. Normalizing sexual health tests and seeing hard results on paper before sex was a thing, too.)

Addicts, too, knew that using was going to happen no matter how earnestly people tried to stop. If it was that easy, addiction wouldn't exist. So: how do you make using safer for longer? If you could stop someone getting HIV before they could bring themselves to get clean, that's a whole life right there. If you could stop someone overdosing once, twice, a dozen times, that's more time you're buying them to claw themselves out of addiction and into a better place. Addicts see, right, needle sharing is getting the diseases spread, so cut down on needle sharing. Well, needles aren't easy to get hold of. Their supply is controlled because people who aren't prescribed needles are theoretically junkies, so taking the needles away makes it harder to use, right— and no one is complicit, and also you see fewer discarded needles lying around where they're unsanitary and unsafe, right? Except that people want to do a buddy a good turn, so they share if there's no other option, and they'll keep a needle going until it's literally too blunt to keep using if need be. So fighting needle sharing means making it easier to get needles to shoot up with: finding a place to discard used ones and get as many fresh ones as you need to use safely!

Making free needles available to junkies and free condoms for the bathhouses was not a popular solution with politicians, for perhaps obvious reasons. Nor was routine testing of the blood supply, because that cost money too. But these things work to stop the spread of disease. Thus the principle of harm reduction: policy interventions in response to communities that frequently engage in risky behavior should focus on whatever reduces aggregate harm by reducing the risk rather than by trying to reduce the behavior. The homos and junkies say look, all your societal judgement in the world hasn't stopped us being homos and junkies yet. You ain't going to look after us? We'll look after our own. And this is the form that takes. Not increasing the pressure to act like people who aren't is, but making it safer to be the people we are while we try to be the happiest versions of ourselves. Even if that means being morally complicit in a whole lot of casual sex and drug abuse.

The thing is, harm reduction is a philosophy rooted in the defiance of people who knew that their society thought they deserved to die painfully, young, invisible and alone. This is not the kind of thing that people come up with and get mad if you adapt it and share it, especially if you tell the story of where it came from. And importantly, harm reduction is not purely the child of addiction: that philosophy, from the get go, was cooked up to apply both to substance abuse and casual sex. It didn't just spread from addiction care; it was born straddling addiction care and queer & feminist health care.

So it doesn't make sense to see actual activists who know harm reduction well complaining that this is a term exhibiting semantic drift when we talk about voting as harm reduction. It's actually a good metaphor: you're reducing the overall risk of the worst case scenario metaphors by voting Democrat, at least until future votes can install a system where multiple parties can flourish on the political scheme. (Democrats and Republicans are essentially coalitions of a pack of arguing factions anyway, and those factions are essentially what would be classed elsewhere as a party in its own right; the US essentially just lumps political granularity rather than splitting it in our political system.) And anyone who understands harm reduction itself knows that.

So it's this wildly inorganic complaint being voiced repeatedly by different sources. Sounds like a pretty good flag for a potential psyop to me.

If you want to learn more about harm reduction and its history, especially from an addiction perspective, I cannot recommend Maia Szalavitz's Undoing Drugs: How Harm Reduction is Changing the Future of Drugs and Addiction (2022) highly enough. Szalavitz has a history of addiction of her own as well as being a clear and accessible writer with an excellent grasp of neuroscience and history. I have a lot of respect for her work.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In HIV prevention, there has been remarkable community-led research by experts such as Sari Reisner, Asa Radix, Jae Sevelius, and others highlighting that transgender MSM (TMSM) are a key group in the fight to end HIV,” Pedro B. Carneiro, PhD, MPH, notes. “Their behaviors and HIV incidence are comparable to, and at times higher than, their cisgender counterparts.” However, despite the importance of reaching TMSM to achieve HIV elimination goals, this group is “under-represented in research, excluded from guidelines and clinical trials, and overlooked in our national strategy to end HIV,” Dr. Carneiro says. “Moreover, much of the existing research has been cross-sectional, which limits our ability to explore the long-term challenges (ie, PrEP uptake and use) faced by this community and advocate for change.”

For those interested in the topic of trans men and HIV, check out the Policy Brief on Effective Inclusion of Trans Men in the Global HIV and Broader Health and Development Responses mentioned in the article.

760 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Since it was first identified in 1983, HIV has infected more than 85 million people and caused some 40 million deaths worldwide.

While medication known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, can significantly reduce the risk of getting HIV, it has to be taken every day to be effective. A vaccine to provide lasting protection has eluded researchers for decades. Now, there may finally be a viable strategy for making one.

An experimental vaccine developed at Duke University triggered an elusive type of broadly neutralizing antibody in a small group of people enrolled in a 2019 clinical trial. The findings were published today [May 17, 2024] in the scientific journal Cell.

“This is one of the most pivotal studies in the HIV vaccine field to date,” says Glenda Gray, an HIV expert and the president and CEO of the South African Medical Research Council, who was not involved in the study.

A few years ago, a team from Scripps Research and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) showed that it was possible to stimulate the precursor cells needed to make these rare antibodies in people. The Duke study goes a step further to generate these antibodies, albeit at low levels.

“This is a scientific feat and gives the field great hope that one can construct an HIV vaccine regimen that directs the immune response along a path that is required for protection,” Gray says.

-via WIRED, May 17, 2024. Article continues below.

Vaccines work by training the immune system to recognize a virus or other pathogen. They introduce something that looks like the virus—a piece of it, for example, or a weakened version of it—and by doing so, spur the body’s B cells into producing protective antibodies against it. Those antibodies stick around so that when a person later encounters the real virus, the immune system remembers and is poised to attack.

While researchers were able to produce Covid-19 vaccines in a matter of months, creating a vaccine against HIV has proven much more challenging. The problem is the unique nature of the virus. HIV mutates rapidly, meaning it can quickly outmaneuver immune defenses. It also integrates into the human genome within a few days of exposure, hiding out from the immune system.

“Parts of the virus look like our own cells, and we don’t like to make antibodies against our own selves,” says Barton Haynes, director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute and one of the authors on the paper.

The particular antibodies that researchers are interested in are known as broadly neutralizing antibodies, which can recognize and block different versions of the virus. Because of HIV’s shape-shifting nature, there are two main types of HIV and each has several strains. An effective vaccine will need to target many of them.

Some HIV-infected individuals generate broadly neutralizing antibodies, although it often takes years of living with HIV to do so, Haynes says. Even then, people don’t make enough of them to fight off the virus. These special antibodies are made by unusual B cells that are loaded with mutations they’ve acquired over time in reaction to the virus changing inside the body. “These are weird antibodies,” Haynes says. “The body doesn’t make them easily.”

Haynes and his colleagues aimed to speed up that process in healthy, HIV-negative people. Their vaccine uses synthetic molecules that mimic a part of HIV’s outer coat, or envelope, called the membrane proximal external region. This area remains stable even as the virus mutates. Antibodies against this region can block many circulating strains of HIV.

The trial enrolled 20 healthy participants who were HIV-negative. Of those, 15 people received two of four planned doses of the investigational vaccine, and five received three doses. The trial was halted when one participant experienced an allergic reaction that was not life-threatening. The team found that the reaction was likely due to an additive in the vaccine, which they plan to remove in future testing.

Still, they found that two doses of the vaccine were enough to induce low levels of broadly neutralizing antibodies within a few weeks. Notably, B cells seemed to remain in a state of development to allow them to continue acquiring mutations, so they could evolve along with the virus. Researchers tested the antibodies on HIV samples in the lab and found that they were able to neutralize between 15 and 35 percent of them.

Jeffrey Laurence, a scientific consultant at the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) and a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, says the findings represent a step forward, but that challenges remain. “It outlines a path for vaccine development, but there’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” he says.

For one, he says, a vaccine would need to generate antibody levels that are significantly higher and able to neutralize with greater efficacy. He also says a one-dose vaccine would be ideal. “If you’re ever going to have a vaccine that’s helpful to the world, you’re going to need one dose,” he says.

Targeting more regions of the virus envelope could produce a more robust response. Haynes says the next step is designing a vaccine with at least three components, all aimed at distinct regions of the virus. The goal is to guide the B cells to become much stronger neutralizers, Haynes says. “We’re going to move forward and build on what we have learned.”

-via WIRED, May 17, 2024

#hiv#aids#aids crisis#virology#immunology#viruses#vaccines#infectious diseases#vaccination#immune system#public health#medicine#healthcare#hiv aids#hiv prevention#good news#hope#medical news

920 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Big TB Announcement

Greetings from Washington D.C., where I spent the morning meeting with senators before joining a panel that included TB survivor Shaka Brown, Dr. Phil LoBue of the CDC, and Dr. Atul Gawande of USAID. Dr. Gawande announced a major new project to bring truly comprehensive tuberculosis care to regions in Ethiopia and the Philippines. Over the next four years, this project can bring over $80,000,000 in new money to fight TB in these two high-burden countries.

Our family is committing an additional $1,000,000 a year to help fund the project in the Philippines, which has the fourth highest burden of tuberculosis globally.

Here’s how it breaks down: The Department of Health in the Philippines has made TB reduction a major priority and has provided $11,000,0000 per year in matching funds to go alongside $10,000,000 contributed by USAID and an additional $1,000,000 donated by us. This $22,000,000 per year will fund everything from X-Ray machines, medications, and GeneXpert tests to training and employing a huge surge of community health workers, nurses, and doctors who are calling themselves TB Warriors. In an area that includes nearly 3,000,000 people, these TB Warriors will screen for TB, identify cases, provide curative treatment, and offer preventative therapy to close contacts of the ill. We know this Search-Treat-Prevent model is the key to ending tuberculosis, but we hope this project will be both a beacon and a blueprint to show that It’s possible to radically reduce the burden of TB in communities quickly and permanently. It will also, we believe, save many, many lives.

—

I believe we can’t end TB without these kinds of public/private partnerships. After all, that’s how we ended smallpox and radically reduced the global burden of polio. It’s also how we’ve driven down death from malaria and HIV. For too long, TB hasn’t had the kind of government or private support needed to accelerate the fight against the disease, but I really hope that’s starting to change. I’m grateful to USAID for spearheading this project, and also to the Philippine Ministry of Health for showing such commitment and prioritizing TB.

—

One reason this project is even possible: Both the cost of diagnosis (through GeneXpert tests) and the cost of treatment with bedaquiline are far lower than they were a year ago, and that is due to public pressure campaigns, many of which were organized by nerdfighteria. I’m not asking you for money (yet); Hank and I will be funding this in partnership with a few people in nerdfighteria who are making major gifts. But I am asking you to continue pressuring the corporations that profit from the world’s poorest people to lower their prices. I’ve seen some of the budgets, and it’s absolutely jaw-dropping how many more tests and pills are available because of what you’ve done as a community.

—

I don’t yet have the details on which region of the Philippines we’ll be working in, but it will be an area that includes millions of people–perhaps as many as 3 million. And it will include urban, suburban, and rural areas to see the different responses needed to provide comprehensive care in different communities. This will not (to start!) be a nationwide campaign, because even though $80,000,000 is a lot of money, it’s not enough to fund comprehensive care in a nation as large as the Philippines. But we hope that it will serve as a model–to the nation, to the region, and to the world–of what’s possible.

—

I’m really excited (and grateful) that our community gets to have a front-row seat to see the challenges and hopefully the successes of implementing comprehensive care. Just in the planning, this project has involved so many contributors–NGOs in the Philippines, global organizations like the Partners in Health community, USAID, the national Ministry of Health in the Philippines, and regional health authorities as well. There are a lot of partners here, but they’ve been working together extremely well over the last few months to plan for this project, which will start more or less immediately thanks to their incredibly hard work.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The year is 1998. While antiviral drugs to treat HIV had been approved a decade earlier, only five out of 33 million people who carried the virus were receiving the life-saving treatment. Nowhere was the situation worse than in South Africa. The country had the highest global prevalence of the disease with nearly one in five people infected and 200,000 children orphaned.

Treatment options were limited. That year, the Minister of Health released a report outlining the deficiencies in the country’s health care system. The principal finding was that most South Africans could not afford antivirals. The average monthly income at the time hovered around $220 a month, which was nowhere near the $1,000 per month the pharma companies were charging for their wares. Faced with a virus that was decimating his population, Nelson Mandela made a choice that landed him in court for the first time since his arrest several decades earlier for resisting apartheid.

His government broke the patent regime for the antivirals that was chiefly responsible for killing his people—allowing parallel imports in which generics companies manufacture the drug without the patent-holding pharma company’s consent. He was instantly sued by 40 pharmaceutical companies. Bill Clinton’s administration cowered to pressure from the pharma lobby and placed South Africa on a watchlist, subjecting the nation to possible trade sanctions. It ended up being an enormous PR disaster for the obstreperous pharmaceutical firms. After three years of mounting pressure from AIDS activists, the pharma companies finally dropped their case.

While this story has a happy ending, Mandela’s battle against Big Pharma was only a small part of an ongoing war to provide equitable access to HIV medication. In the decades since his court case, taxpayer-funded research has contributed enormously to the development of new HIV treatments. New drugs can now allow people living with HIV to enjoy normal life spans, and completely reduce the risk of new transmissions. Used widely, medications should allow the complete eradication of HIV from the planet. The only obstacle the world is now facing is the same one Mandela stared down: corporate greed which prioritizes profits over human life.

@startorrent02

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new way to reprogram immune cells and direct them toward anti-tumor immunity

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/a-new-way-to-reprogram-immune-cells-and-direct-them-toward-anti-tumor-immunity/

A new way to reprogram immune cells and direct them toward anti-tumor immunity

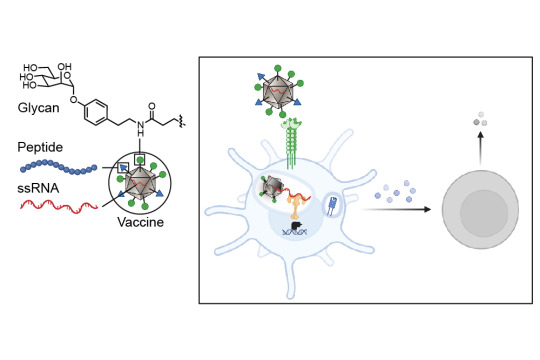

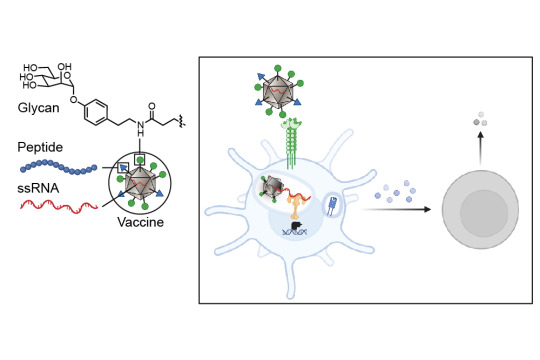

A collaboration between four MIT groups, led by principal investigators Laura L. Kiessling, Jeremiah A. Johnson, Alex K. Shalek, and Darrell J. Irvine, in conjunction with a group at Georgia Tech led by M.G. Finn, has revealed a new strategy for enabling immune system mobilization against cancer cells. The work, which appears today in ACS Nano, produces exactly the type of anti-tumor immunity needed to function as a tumor vaccine — both prophylactically and therapeutically.

Cancer cells can look very similar to the human cells from which they are derived. In contrast, viruses, bacteria, and fungi carry carbohydrates on their surfaces that are markedly different from those of human carbohydrates. Dendritic cells — the immune system’s best antigen-presenting cells — carry proteins on their surfaces that help them recognize these atypical carbohydrates and bring those antigens inside of them. The antigens are then processed into smaller peptides and presented to the immune system for a response. Intriguingly, some of these carbohydrate proteins can also collaborate to direct immune responses. This work presents a strategy for targeting those antigens to the dendritic cells that results in a more activated, stronger immune response.

Tackling tumors’ tenacity

The researchers’ new strategy shrouds the tumor antigens with foreign carbohydrates and co-delivers them with single-stranded RNA so that the dendritic cells can be programmed to recognize the tumor antigens as a potential threat. The researchers targeted the lectin (carbohydrate-binding protein) DC-SIGN because of its ability to serve as an activator of dendritic cell immunity. They decorated a virus-like particle (a particle composed of virus proteins assembled onto a piece of RNA that is noninfectious because its internal RNA is not from the virus) with DC-binding carbohydrate derivatives. The resulting glycan-costumed virus-like particles display unique sugars; therefore, the dendritic cells recognize them as something they need to attack.

“On the surface of the dendritic cells are carbohydrate binding proteins called lectins that combine to the sugars on the surface of bacteria or viruses, and when they do that they penetrate the membrane,” explains Kiessling, the paper’s senior author. “On the cell, the DC-SIGN gets clustered upon binding the virus or bacteria and that promotes internalization. When a virus-like particle gets internalized, it starts to fall apart and releases its RNA.” The toll-like receptor (bound to RNA) and DC-SIGN (bound to the sugar decoration) can both signal to activate the immune response.

Once the dendritic cells have sounded the alarm of a foreign invasion, a robust immune response is triggered that is significantly stronger than the immune response that would be expected with a typical untargeted vaccine. When an antigen is encountered by the dendritic cells, they send signals to T cells, the next cell in the immune system, to give different responses depending on what pathways have been activated in the dendritic cells.

Advancing cancer vaccine development

The activity of a potential vaccine developed in line with this new research is twofold. First, the vaccine glycan coat binds to lectins, providing a primary signal. Then, binding to toll-like receptors elicits potent immune activation.

The Kiessling, Finn, and Johnson groups had previously identified a synthetic DC-SIGN binding group that directed cellular immune responses when used to decorate virus-like particles. But it was unclear whether this method could be utilized as an anticancer vaccine. Collaboration between researchers in the labs at MIT and Georgia Tech demonstrated that in fact, it could.

Valerie Lensch, a chemistry PhD student from MIT’s Program in Polymers and Soft Matter and a joint member of the Kiessling and Johnson labs, took the preexisting strategy and tested it as an anticancer vaccine, learning a great deal about immunology in order to do so.

“We have developed a modular vaccine platform designed to drive antigen-specific cellular immune responses,” says Lensch. “This platform is not only pivotal in the fight against cancer, but also offers significant potential for combating challenging intracellular pathogens, including malaria parasites, HIV, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This technology holds promise for tackling a range of diseases where vaccine development has been particularly challenging.”

Lensch and her fellow researchers conducted in vitro experiments with extensive iterations of these glycan-costumed virus-like particles before identifying a design that demonstrated potential for success. Once that was achieved, the researchers were able to move on to an in vivo model, an exciting milestone for their research.

Adele Gabba, a postdoc in the Kiessling Lab, conducted the in vivo experiments with Lensch, and Robert Hincapie, who conducted his PhD studies with Professor M.G. Finn at Georgia Tech, built and decorated the virus-like particles with a series of glycans that were sent to him from the researchers at MIT.

“We are discovering that carbohydrates act like a language that cells use to communicate and direct the immune system,” says Gabba. “It’s thrilling that we have begun to decode this language and can now harness it to reshape immune responses.”

“The design principles behind this vaccine are rooted in extensive fundamental research conducted by previous graduate student and postdoctoral researchers over many years, focusing on optimizing lectin engagement and understanding the roles of lectins in immunity,” says Lensch. “It has been exciting to witness the translation of these concepts into therapeutic platforms across various applications.”

#antigen#applications#author#Bacteria#Biological engineering#Cancer#cancer cells#cell#Cells#chemistry#collaborate#Collaboration#deal#Design#design principles#development#Diseases#display#Fight#Fundamental#fungi#hiv#human#human cells#immune cells#immune response#immune system#immunology#Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES)#it

1 note

·

View note