#Glaser and Strauss

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Grounded Theory: Making It Up As You Go Along (But With Integrity)

This week, in a break from stalking the usual parade of sociological ghosts—Marx, Weber, Bourdieu and the like—I thought we’d do something different. Let’s talk about something alive, terrifyingly current, and capable of causing existential dread in postgraduate students across the globe: methodology. More specifically, Grounded Theory. Now, if you’ve never come across Grounded Theory, count…

#Academic Life#coding chaos#data analysis nightmares#Glaser and Strauss#grounded theory#methodology humour#NVivo struggles#postgraduate research#qualitative research#reflexivity#research satire#social science humour#sociological methods#sociology jokes#theoretical saturation

0 notes

Text

Grounded theory denotes to an inductive research methodology aimed at the production of a theory that explains certain patterns in a given set of data, and predicts what social scientists may anticipate to find in such data (Glaser & Strauss, 2012). The theory involves the collection and analysis of a given set of and as such it is “grounded” in actual data, which implies that the analysis and the development of the subsequent theories occurs after data has been collected. Introduced in the 1967 by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, the theory was aimed at legitimizing qualitative research though it can be used in quantitative research studies. The two sociologists introduced the theory as an antidote to the popularity of the deductive theory that is more speculative, and mostly disconnected from the realities of social life. Comparatively, the grounded theory establishes a theory that is based on scientific research (Glaser & Strauss, 2012). The theory allows researchers to be creative and scientific at the same time as long as they can adhere to certain guidelines that include periodically stepping back and asking question about the collected and analysed data, and having and maintaining a skeptical attitude about all the theoretical explanations, hypotheses, and questions concerning the data. Further, they researchers must follow research procedures like data collection and analysis so that they can offer precision and accuracy to their studies. In using the theory, researchers start with a set of data and identify the trends, patterns, and the relationship among the different components of the data. It is on this basis that the researchers then construct a theory that uses the data or “grounded” in the data that they have collected and analysed. Again, the methodological strategies of the theory focus on creating or constructing middle-level theories from the data collected and analysed by the researcher. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Data analysis is a pivotal step in qualitative research, transforming raw data — often in the form of interviews, focus groups, observations, or open-ended surveys — into meaningful insights. Qualitative research focuses on understanding human behavior, experiences, and perspectives, making it inherently subjective. The process of analyzing qualitative data involves organizing, interpreting, and presenting the data in a way that uncovers patterns, themes, and narratives. Unlike quantitative data, which focuses on numbers and statistical analysis, qualitative data analysis is more interpretive, often requiring the researcher to dig deeper into the nuances of human experiences.

Understanding the Nature of Qualitative Data

Before diving into data analysis techniques, it’s essential to understand what makes qualitative data unique. Unlike quantitative data, which involves numerical measures and statistical testing, qualitative data is typically textual or visual. For example, it could include interview transcripts, field notes from observations, videos, audio recordings, or even images. This type of data is often rich and complex, providing a deeper understanding of the research participants’ emotions, opinions, and social contexts.

In qualitative research, data analysis is a flexible, iterative process, meaning the researcher may go back and forth between the data, analysis, and theory, refining their understanding as new insights emerge. There isn’t a single right way to analyze qualitative data, but there are several commonly used methods and strategies that researchers can employ to structure their analysis.

Key Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis

1. Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is one of the most widely used methods in qualitative research. It involves identifying and analyzing patterns or themes within the data. A theme is a broad idea or concept that captures important aspects of the data. Thematic analysis is a relatively straightforward and flexible method, making it suitable for a range of research questions and data types.

To conduct thematic analysis, the researcher typically follows these steps:

Familiarization with the data: Transcribing, reading, and re-reading the data to become immersed in it.

Generating initial codes: Identifying interesting features of the data that are relevant to the research question.

Searching for themes: Grouping the codes into broader themes or categories.

Reviewing themes: Refining the themes to ensure they accurately represent the data.

Defining and naming themes: Giving clear, concise names to each theme.

Writing the analysis: Presenting the findings with supporting evidence from the data.

Thematic analysis is particularly helpful when the goal is to provide a detailed and nuanced description of patterns across a dataset, offering rich insights into the underlying meanings and experiences of participants.

2. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is a more complex and systematic approach to data analysis, developed by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss. Unlike other methods, grounded theory aims to develop a theory or conceptual framework that is “grounded” in the data itself. The process is inductive, meaning that researchers begin with no preconceived hypotheses and let the data guide the development of theory.

The steps involved in grounded theory include:

Open coding: Breaking down the data into discrete parts, which are labeled and categorized.

Axial coding: Reassembling the data by identifying relationships between codes and categories.

Selective coding: Identifying core categories that relate to the central phenomenon of the study.

Theory development: Formulating a grounded theory that explains the research findings.

Grounded theory is particularly effective when the aim is to explore a new or under-researched topic and generate theories that can later be tested or expanded upon.

3. Content Analysis

Content analysis is a technique used to systematically analyze textual data. It involves coding the data and identifying the frequency and context of specific words, phrases, or concepts. This method is used when researchers want to quantify specific elements within the data and analyze patterns or trends. While it shares similarities with thematic analysis, content analysis is more focused on the frequency and presence of particular items in the data, making it more suitable for large datasets.

Researchers conducting content analysis typically follow these steps:

Choosing the material: Selecting the data (e.g., interviews, text documents) to analyze.

Defining categories: Developing categories or codes that are relevant to the research question.

Coding the data: Assigning codes to relevant segments of the data.

Analyzing frequency: Counting the frequency of codes and identifying patterns.

Interpreting results: Drawing conclusions based on the frequency and context of codes.

Content analysis is particularly useful for analyzing large volumes of text and identifying trends, patterns, and shifts in language over time.

Organizing and Interpreting Qualitative Data

Once the data is analyzed using one of these methods, the next challenge is organizing and interpreting the findings. This requires synthesizing the data and looking for connections between themes or categories. It’s crucial to approach the interpretation phase with an open mind, as qualitative data often offers multiple layers of meaning.

In qualitative research, interpretation involves more than just summarizing the data. Researchers must analyze how the themes relate to the research question, the broader context of the study, and any existing theories. It’s important to consider participants’ perspectives and experiences, as well as the social, cultural, or historical context in which they live.

Conclusion

In conclusion, data analysis in qualitative research is a dynamic and interpretive process. It involves identifying patterns, themes, and insights within textual or visual data to answer research questions. The methods of thematic analysis, grounded theory, and content analysis are just a few of the tools available to researchers, each offering unique approaches for analyzing complex human experiences. By carefully analyzing qualitative data, researchers can uncover deeper understandings of social phenomena and contribute valuable insights to academic fields and real-world issues.

Effective data analysis is essential to qualitative research, as it transforms raw data into meaningful conclusions. Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or a newcomer to qualitative methods, understanding the analysis process will help you navigate the complexities of qualitative data and enrich your research findings.

#content analysis#qualitative analysis#data analysis for qualitative#data analysis of a qualitative research

0 notes

Note

Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances In The Methodology of Grounded Theory

Dear reader, can you help me download the electronic version of this book and send it to me? I am very passionate about this book. Here, first of all, thank you all for your enthusiastic help

Hello,

I only have a hard copy for myself. I’m sorry. There might be great used books online you can buy. Check ebay and worldwide shipping bookstores. You can find glaser and strauss’ books also from their publishers from California, USA. I am pretty sure they can ship anywhere in the word.

0 notes

Text

This semester I will join a seminar on Grounded Theory. The crux; my professor will do the seminar similar to the grounded theory, a constant mix of theory, writing and thinking, no plan intended. We simply start by doing our own stuff, an ethnographic study as the base-data. I‘m curious and afraid at the same time. Wish me luck

1 note

·

View note

Text

INVESTING IN OUR TEACHERS TODAY FOR TOMORROW

BY SANDY NICOLL 2006

This is the conclusion of my Masters by Research study. It pre-dates thesis being stored online. It was awarded a High Distinction and I came first in the cohort. My PhD changed direction for I wanted to find a way to help move teaching forward.

Conclusion:

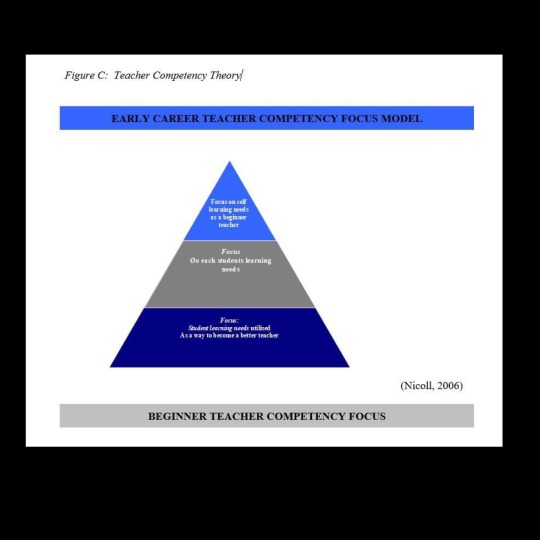

The Proficiency Pyramid involves three layers. Early practitioners start at the top and progress to the bottom. There is no time frame allocated to the proficiency progression. Further, teachers use the preceding level/s as they advance through the pyramid and their career. Additionally, the theory model does not assume all teachers will progress through to the final layer. Instead only truly competent/ proficient teachers’ use all three layers in their practice. This theory is regarded to have generality implications for the focus is not on specific subject areas but rather the approach to competent practice.

As the chief investigator I proposed a three level Professional Development model be utilised by an effective competent teacher. The pyramid design supports Grounded Theory Methodology as it involves the four key components of functionality, it is implicit for people working within the field, it can apply to more than one situation and it has applications for everyday life (Johnson & Christenson, 2004).

The layers include:

1. Beginning proficiencies focus upon teacher proficiency. This includes how teachers can best manage the classroom in terms of behaviour management, organisational skills, questioning, programming and assessing. The focus is on the teacher themselves.

2. Next, as teachers become more self-managing and efficient the teacher proficiencies focus shifts and the focus becomes the student. Certainly core teacher oriented proficiencies still exist. However, the focus is student oriented rather than themselves.

3. Finally, the truly proficient teacher can be concluded to shift their proficiency focus to how a teacher can use student issues to establish how I can become a more proficient teacher.

The theory can be summarised in the figure below as advocated by Vaughan (1992) and Strauss (1970). Both advocated Grounded Theory Methodology permitted factors such as the development of a model or a particular concept.

This model has been concluded in this study to demonstrate a way forward for teachers to become highly competent in the classroom. Thus, following this model will achieve greater success with student learning. Therefore, this model offers a divergent way of looking at the art of teaching and pedagogical practice. It guides professional directions as it establishes how teachers can use competencies to accomplish superior classroom practice.

6.3 Possible Future Aims/Directions

1. Integrate and respond to one group of key stakeholders, primary teachers in executive positions or by extending the study group beyond three participants

2. Identify what is perceived is being done/poorly well by primary teachers and reasons Why? /Why Not?

3. Identify future targets or course features in teacher pre-training as identified by current practicing teachers and this research study

4. Conduct a study designed to ask why teacher retention rates in terms of ‘30% leaving within the first 5 years’ in an effort to develop state wide plans

5. Another study could explore teachers who have not sort higher education qualifications since graduation of pre-service teaching and the implications for life long learning

6.4 Implications of the Study

This study will have implications and ramifications for teachers, the NSW Department of Education and relevant educational institutions. This study may form the basis of a PhD study commencing in 2007. The chief investigator believes the study can best serve the education community by being written and published through various avenues. The possibilities may include being published in:

• Academic Journals,

• Course readings during teacher retraining courses or Master Programs,

• In the Teacher newspapers such as the NSW Federation News

• Daily papers including a letter to The Australian and The Daily Telegraph.

Consequently, the idea of ‘discourse’ and empowerment will be encouraged and facilitated. Key stake holders will be able to develop and discuss the varying pedagogical implications of critical, authentic and productive pedagogy. Teachers will be able to genuinely discuss the study, which may serve as a valuable discourse strategy on its own.

This study has identified what highly competent teachers in the classroom do to achieve greater success with student learning. Therefore, this model offers a divergent way of looking at productive pedagogical practice. It will have implications for teachers, educational institutes and the NSWDET as it will provide an easily understood model for professional direction. The model is designed to establish how teachers can use competencies to accomplish superior classroom practice.

6.5 Discussion: Personal For’s/ Against for the Chief Investigator of the Project

Personal For’s:

The chief investigator in this study enjoyed this approach and found encouragement in this for it fostered creativity and opportunity. The investigator did feel genuine teacher commentary was achieved which was a key aim of the study. Consequently, it can be concluded Grounded Theory approach supports the idea of genuine commentary data collection.

The key components of applicability, functionality, giving a sense of direction for people working in the field, and the potential to apply the theory generated in everyday life was deemed to be achieved by this study. Thus, the investigator has deemed this project to be worthwhile.

The Grounded Theory Methodology gave an opportunity to utilise inferring and deducing. This facilitated the consideration of personal and primary experience to be regarded such as expressions and discourse.

The chief investigator acknowledges comparative analysis was a key feature of this particular study. This was utilised to generate hypothesises. However, this study did rely upon the individual investigator’s own interpretation of commentaries. Finally, the investigator is very willing to take on a sense of personal ownership for conclusions drawn and the theory proposed.

Personal Againsts:

Goulding (1998) argues taking care to consider possible misconceptions when considering the methodology and potentially misusing principles and procedures (p.155). This is a concern for the chief investigator and peer reviewing will be and has been a core validation technique designed to minimise this effect. Consequently, seeking peer reviewing was an invaluable tool.

Glaser (1978) illustrates another limitation and titled it the “drugless trip”. This may result if the chief investigator develops a continual and ceaseless fixation with analysing and collecting data. At times, the chief investigator did feel the trip or journey would not end. However, relying upon supervisors, limiting to participants to be three people only, end of semester dates and reasonable word limits did help avoid clouding progression. Although, progression at times did become very cloudy and the chief investigator sought ‘time out’ to allow for this progression to reignite.

Thus:

“Education is not simply a technical business of well-managed information processing, not even simply a matter of applying ‘learning theories’ to the classroom or using the results of subject-centered ‘achievement testing’. It is a complex pursuit of fitting a culture to needs of its members, and its members and their ways of knowing to the needs of the culture.” (Bruner, 1996, p. 41)

“[The] quality of what teachers know and can do has the greatest impact upon student learning… A clear message for policy makers is to invest first and most in policies that enhance teacher quality”

(Ingvarson, 2003, p. 2).

1 note

·

View note

Text

REGENERATIVE LEADERSHIP

Regenerative Leadership is the process of aligning one’s own way of being, one’s actions, ways of communicating and being in relationship with the wider pattern of life’s evolutionary journey towards increasing complexity and coherence with in the nested wholeness of community, ecosystems biosphere and Universe we participate in. (Wahl, 2019) Many leaders have termed regenerative to provide an alternative to the notion of sustainability which many of leaders featured here indicate has become insufficient to describe what needs to be done, economically, socially and environmentally if we are to ensure a flourishing world for present and future generations.

Simply expressed before we can live in a sustainable society, locally and globally, we must undergo profound paradigm shift like those that have allowed us throughout the ages to divest ourselves of beliefs that could no longer explain reality, that no longer worked for us, to seek out and adopt a more satisfactory new set of beliefs. (Kuhn, 1962)

According to Brown (2006), it is not quite suitable for the leaders to rely on the traditional approaches to leadership in finding better alternatives to solve existing problems.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Regenerative leaders are meant to have dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities have been defined as the capacity to renew competencies to achieve congruence with the changing business environment by ‘adapting, integrating, and reconfigurating internal and external organizational skills, resources and functional experiences. (Teece, Pisano and Shuen, 1997). ‘Dynamic capability is defined as the capacity of an organisation to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base.’ (Helfal, 2007). To qualify as a dynamic capability, a capability not only needs to change the resource base, but it also needs to be embedded in the firm, and ultimately be repeatable. (Helfat, Peteraf, 2003)

However, dynamic capabilities are argued to comprise of four main process: reconfiguration, leveraging, learning and integration. (Bowman, Ambrosini, 2003) Reconfiguration refers to the transformation and recombination of assets and resources, example, the consolidation of manufacturing resources that often occurs because of an acquisition. Leveraging refers to the replication of a process or system that is operating in one area of a firm into another are, or extending a resource by deploying it into a new domain for instance applying an existing brand to a new set of products. As a dynamic capability, learning allows tasks to be performed more effectively and efficiently, often as an outcome of experimentation and permits reflection on failure and success. Finally, integration refers to the ability of the firm to integrate and coordinate its assets and resources, resulting in the emergence of a new resource base.

When current dynamic capabilities are perceived to be insufficient to impact appropriately upon a firm’s resource base the dynamic capabilities themselves needs to be renewed. In other words, the firm needs to change the way it purposefully creates, extends, or modifies its resource base. (Helfat, 2007). In these circumstances a firm needs a set of dynamic capabilities to act upon the extant set of currently embedded dynamic capabilities, thus allowing it to change its resource base in new ways. These regenerative dynamic capabilities allow the firm to move away from previous change practices towards new dynamic capabilities. Regenerative dynamic capabilities are likely to be deployed by firms whose managers perceive that the environment is turbulent, where external changes are non-linear and discontinuous. (D’Aveni, 1994)

In essence, the leadership challenges of sustainability are contained in the need to balance complex and sometimes conflicting demands for economically, socially and environmentally sustainable solutions which require skills and behaviors that have gone unrecognized or have not been necessary in more stable organisational and social environments. (Ferdig, 2007)

The sustainability leaders create opportunities for people to come together and generate their own answers- to explore, to learn, and to devise a realistic course of action it addresses sustainability challenges. Instead of giving direction, sustainability leaders develop and implement actions in collaboration with others, modifying them as needed to adapt to unforeseen changes in the environment over time sustainability leaders recognize that the experience of change itself, and the dissonance it creates, fuels new thinking, discoveries, and innovations that can revitalize organisations. Furthermore, (Ferdig 2007) indicates that sustainability leaders make the notion of sustainability personally relevant, grounding action in a personal ethic that reaches beyond self-interest. They recognize that all of us can co-create the future through individual ways seeing, understanding, interacting, and doing. Sustainability leaders are informed, aware, realistic, courageous, and personally hopeful in ways that genuinely attract others to business of living collaboratively. From this perspective, it is impossible to define sustainability leadership as purposeful action driven from a position of enlightened self-interest, where benefiting others and the planet means the same as benefiting oneself. (Capra 2002)

Sustainability can be defined as the ability of natural and social systems to continue along what they are doing indefinitely, whereas sustainable development is the process that is undertaken so that sustainability may be achieved. (Attkisson 2008)

Regenerative leadership sits at the very core of what the organisations of today, and more importantly tomorrow, will need to rely on to thrive. (Nicklin 2020)

REGNERATIVE LEADERSHIP FRAMEWORK

The Regenerative Leadership Framework emerged from the findings of structured interviews conducted with 24 highly successful sustainability leaders in the field of business, education, and community development. The research methodology applied was the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis known as grounded theory. (Glaser and Strauss, 1967)

The study was conducted among terminal cancer patients. The major premise of the method is to allow theory to emerge from the data, rather than seeking to confirm a hypothesis, as in the scientific method. Though this may appear to contradict the scientific method, it ensures that the research bias is minimized, providing for objective findings to be extracted from the data. Among the most exiting findings was the overall correlation of leadership styles across the 3 domains of business, education, and community. While each of the approaches to sustainability of the 24 leaders were nuanced towards the most central aspect of their specific field, whether economic, environmental or social there was a surprising commonality in how they defined sustainability, how they came to perceive themselves in the context of sustainability and sustainable development, and how this influenced their leadership behavior. In the sequence of interviews, for example the majority the respondents shared the basic definition of sustainability, often used interchangeably with sustainable development, of the well-known Brandt Land Commission Report of 1987, which considers this to be the “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on environment and development, 1987)

The regenerative leadership constructs aggregated in the 4 quadrants may be broadly conceptualized as follows:

Quadrant 1 (Individual Interior/Subjective)

Facilitating access to the source of personal purpose and emerging self.

Quadrant 2 (Individual Exterior/Objective)

Connecting with others through keen observation and deep listening.

Quadrant 3 (Collective Interior/Subjective)

Eliciting collective purpose through generative conversation

Quadrant 4 (Collective Exterior/Objective)

Engaging in collective action through third-order change and back carting to strategize and prototype the best possible solutions to emerging futures.

The framework is completed by 3 additional visuals:

1) The horizontal field of engagement and emerging consciousness

2) The indirect regenerative leadership path represented by the infinity symbol; and

3) The 2 semi-circular arrows surrounding the framework that symbolise the collaborative heterarchical leadership style that is necessary for successful management within and across multiple systems and organisations for sustainability to be made possible.

CURRENT LEADERS AND REGENERATIVE LEADRSHIP

For several leaders today, many of whom were trained in a previous era of leadership thinking, this more to more emotionally intelligent, empathetically influenced and regeneratively-led business is infinitely difficult to grasp. When there was a same conversation with a millennial leader, however, they understand intrinsically that this move is not an option. It is what 21st century business, and certainly business post COVID-19 crisis, is already poised to be founded on.

“It will be in this driving of awareness surrounding the role of regenerative leadership, which systematically puts empathy at the core of organisations that we can build-and rebuild. Business and human resilience will provide impactful organisational results”.

Regenerative Business enriches life. It enriches us our customers, and the wider stakeholder ecosystem. Regenerative Business transforms our role and purpose, from a “what’s-in-it-for me” approach to a mindset of collaboration, co creativity and contribution.

“Seeking inspiration in the natural world, the principles in regenerative leadership provide a framework for a more inspired path forward in business and life” (Gellert 2020)

KEY CHANGES THAT CAN BE MADE THROUGH REGENERATIVE LEADERSHIP

Despite of these stressful times organisational functions can be made more purposeful, creative, agile, and wiser. There are 2 pathways to be considered:

1) Chooses fear and degeneration.

2) Chooses life and regeneration.

The exact idea is that the systematic challenges we face relate to a need for an inner awakening within our collective and individual psyche. The ultimate act of leadership is guiding ourselves, our teams, and social systems through real transformation.

Shyji Saji George

MBA student.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Methodology

From Pragmatism to Piracy

I must start by stating that I had never done research as a means to an end within my practice before. I had always gone with my gut or accumulated knowledge as a process towards a final outcome. Blinded by my own random thoughts, I had no notion whatsoever of the insights the research could provide to a creative designer/illustrator. I believed fiction and innovation had to be all new things and that there was no gaining from whatever was already done since it was indeed already done. I found out I was extremely wrong as soon as I began.

My method starts with reflective research. I found that it always begins with an emotion, a doubt or an impacting visual that triggered me in some way - just like in the creative process - followed by thorough objective research or an attempt to improve an issue I might have encountered (Mainemelis, 2002). After such I go back to reflecting on my findings.

My objective research allowed me to understand my focus subjects, helped to inform my search with quality texts from reliable and viable sources such as academic books and peer-reviewed articles. This objective search also showed proofs to my reflection, it defended my point of view and, sometimes, it even changed my view of certain subjects with the provided knowledge. It made sure that whatever I was writing about was not biased or incorrect since there were random things I used to believe in when I was young and now I question all of it till proof is given.

I have little use of subjective research since I made no extensive interviews nor any enquiries. I noted responses to my work for one of my blog posts because they were the focus of the experiment and the rest of the subjectivity within the posts is more reflective and critical.

In terms of reliability I focus on peer-reviewed texts as I believe they are at the top of the hierarchic chain of quality references due to their trustworthy content. However, when I gathered subjective research such as in the “Visual Irony” post, I asked colleagues, friends and family members for their insights knowing how their education, culture and beliefs would bias their responses. Opinions could easily vary but, as a designer, the public’s take on what is produced is a must for it to be effective.

From my recent reading on research methods, I found out I’ve leaned towards the grounded theory method by gathering theoretical sampling. This because, just like Glaser and Strauss in the sixties, when a problem would arise, I would gather the evidence from what is directly there by questioning its content in order to prove a point and find a solution to it (Bell & Waters, 2018). New data would always test my ideas in order to add to or break my theory. Once the solution was found, I would distance myself in order to see its faults since it is my belief that the best tool we have rests in our brains, in reflecting on the issues that we stumble upon.

On the other hand I believe I could have gone deeper as I acknowledge that by being critical and reflective I don’t do as much objective research as I think I should in order to support my theories. There is, also, a lack of originality in terms of research methods in my opinion.

Being very introspective, I found reflection to accompany me everywhere I went and in whatever I researched, either for visual inspiration or for when I stumbled upon situations that intrigue me. I used subjectivity when describing the feelings that I experienced so I could show the idea behind most posts as I wanted the reader to feel what I felt. I inspect my research in the end of each post where I relate the objective research I gathered to final concluding thoughts. Nevertheless I do not examine my argumentation’s effectiveness since I would lean towards overthinking and auto-validation until now.

Some of my posts have books defending their subject that might not be considered by all researchers since they might be mirroring my own opinion specifically. Even though I mention the contrasting thoughts on the studied subjects, I lack the consideration of other researchers views when referencing.

Leaving out most of the visual experimentation was my biggest foul provided that my master bases itself on visual language as a priority.

I am, though, limited by my interests, my understanding of only four languages (some articles I might only get access as a pdf of a scanned version where there is no way to translate it) and my education and formulate most conclusions based on my experience since it is my belief that, as I said in the “The Growth of an Idea” post, our actions are connected to us as rational beings since most of our research route’s choices depend on our gut, knowledge or personal taste.

Now, I like to think of my method as an adventure. A journey where I jump on my imaginary boat filled with tools in order to gain knowledge. I stumbled upon some obstacles in the way, gathered more tools and kept drawing my way. I might not even know to where it will lead me. In this sea of research the aim might be reaching land or finding a treasure but I ultimately believe that the richness we end up achieving comes from the whole experience of roaming this ocean of research.

To conclude, I trust it wasn’t only the research itself but the research methods that made me grow as an illustrator and designer opening paths I never knew before.

References:

Bell, J. & Waters, S. (2018) Doing your Research Project: a Guide for First-time Researchers, Open University Press

Mainemelis, C. (2002) “Time and Timelessness: Creativity in (and out of) the Temporal Dimension.” Creativity Research Journal. [Online] 14 (2). pp.227-238. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_9?needAccess=true [Accessed: 21st November]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hofstra University

The Department of Music

presents the

Hofstra Chamber Orchestra and Hofstra Symphony Orchestra with Adam Glaser, Music Director, performing “Symphonic Dances.”

Norman Dello Joio: Choreography: Three Dances for String Orchestra ; Ottorino Respighi: Ancient Airs and Dances, Suite No. 3; Carl Maria von Weber (orch. Berlioz): Invitation to the Dance, op. 65; Johann and Joseph Strauss: Pizzicato Polka; Edvard Grieg: Symphonic Dances, Op. 64

Friday, November 12, 8 p.m. Toni and Martin Sossnoff Theater, John Cranford Adams Playhouse, South Campus Admission is FREE and open to the public. Advance Registration required. More info and to RSVP visit http://tiny.cc/9cfluz

ALL GUESTS (Hofstra students, faculty and staff, as well as visitors) that attend a Hofstra University-sponsored indoor event must be fully vaccinated. Evidence of vaccination will be required at time of entry with Hofstra Pride Pass or proof of vaccination and government ID. Masks covering over your mouth and nose, must be worn at ALL indoor events on campus.

0 notes

Text

Observación participante.

El siguiente reporte es del capítulo dos, titulado LA OBSERVACIÓN PARTICIPANTE. PREPARACIÓN DEL TRABAJO DE CAMPO, del libro Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación de los autores S.J. Taylor y R. Bogdan.

Este capítulo es una orientación sobre qué decisiones que tomar antes de realizar la observación participante. Este capítulo consta de ocho acápites.

En el primer acápite titulado DISEÑO DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN los autores señalan algunas particularidades del diseño de la observación participante.

En el segundo acápite titulado SELECCIÓN DE ESCENARIOS los autores brevemente establecen como elegir el escenario de investigación ideal.

En el tercer acápite titulado ACCESO A LAS ORGANIZACIONES hacen los autores algunas recomendaciones para acceder a investigar organizaciones.

En el cuarto acápite titulado ACCESO A LOS ESCENARIOS PÚBLICOS Y CUASI PÚBLICOS, Taylor & Bogdan abordan algunas sugerencias para la investigación en lugares públicos.

El quinto acápite ACCESO A ESCENARIOS PRIVADOS trata sobre como establecer contacto a escenarios privados.

El sexto acápite ¿QUÉ SE LES DICE A PORTEROS E INFORMANTES? trata sobre como comunicar los intereses investigativos de forma efectiva a informantes y porteros sin obstaculizar la investigación.

El séptimo acápite RECOLECCIÓN DE DATOS. En este acápite se examina la importancia de formular notas de campo de forma detallada.

El octavo y último acápite es titulado INVESTIGACIÓN ENCUBIERTA aquí los autores aluden al criterio de una variedad de científicos sociales, así como también sus propias opiniones sobre la investigación encubierta.

Primer acápite

A diferencia de otros métodos de investigación, la observación participante se caracteriza por su flexibilidad, su enfoque constantemente evoluciona.

Aunque lo conveniente es realizar la observación participante sin preconceptos específicos, siempre existen interrogantes previas a la investigación de campo. Estas interrogantes las dividen los autores en dos categorías: sustanciales y teóricas. Las categorías sustanciales se refieren a interrogantes relacionadas con ''problemas específicos en un particular tipo de escenario'', y las categorías teóricas se refieren a ''problemas sociológicos básicos, tales como la socialización, la desviación y el control social.''

Ambas categorías están interconectadas, debido a que un ''buen estudio cualitativo combina una compresión en profundidad del escenario particular estudiado con intelecciones teóricas generales que trascienden ese tipo particular de escenario.''

Indican que no es sensato aferrase a ningún interés teórico, así como tampoco a ningún escenario, es preferente que se investigue los fenómenos tal y como emergen, y si se encuentra particularmente interesado en cuestiones teóricas, estar dispuesto a cambiar de escenario. Indican que ''Todos los escenarios son intrínsecamente interesantes y sucinta importantes cuestiones teóricas.''

Los autores opinan que ''en el momento en que los observadores participantes inician un estudio con interrogantes e intereses investigativos generales, por lo común no predefinen la naturaleza y número de los casos -escenarios o informantes- que habrán de estudiar.''

Cuando de investigaciones cuantitativas se trata, ''los investigadores seleccionan los casos sobre la base de las probabilidades estadísticas''. El muestreo al azar tiene como objetivo ''asegurar la representatividad de los casos estudiados respecto de una población mayor en la cual está interesado el investigador.''

Similar a este muestreo estadístico, en investigaciones cualitativas, se define la muestra sobre una base que evoluciona conforme el estudio avanza.

Referente a esto, los autores aluden a un concepto formulado por los sociólogos Glaser y Strauss denominado muestreo teórico, este es un procedimiento que consiste en seleccionar ''casos adicionales a estudiar de acuerdo con el potencial para el desarrollo de nuevas intelecciones o para el refinamiento y la expansión de las ya adquiridas.'' Es gracias a este procedimiento es posible comprobar ''si los descubrimientos de un escenario son aplicables a otros, y en qué medida. De acuerdo con Glaser y Strauss, el investigador debería llevar a un rendimiento máximo la variación de casos adicionales seleccionados para ampliar la aplicabilidad de las intelecciones teóricas.''

Segundo acápite

Consideran los autores que un escenario ideal, es donde el investigador: 1) tiene fácil acceso, 2) logra establecer rapport y, 3) le es posible recoger datos pertinentes a su investigación.

Enfatizan la importancia de la paciencia para elegir un escenario, ya que, por lo general, las cosas progresan lentamente.

Sugieren que el investigador evite escenarios en los que exista una cercanía personal o profesional, estiman que ''cuando más próximo se está a algo, más difícil resulta desarrollar la perspectiva crítica necesaria para conducir una investigación consistente.''

Tercer acápite

Cuanto de organizaciones se trata, el investigador obtendrá acceso por medio de porteros. Estos son agentes con alta responsabilidad, con estatus o alto rango.

Es pertinente que el investigador no proyecte que proporcionara inconvenientes o molestias en la estructura de la organización. Debido a que el acceso a las corporaciones y a grandes organizaciones es particularmente difícil, existen varias tácticas de introducción a los que los autores aluden: (1) El enfoque directo; (2) por medio de una red de contactos, y; (3) por la puerta trasera.

Es probable que existan tensiones entre los distintos niveles de jerarquía en una organización, por lo que, si el interés investigativo radica en los niveles inferiores, es preferible que el investigador mantenga considerable distancia de los porteros una vez que se haya obtenido acceso. También existe la posibilidad de que los porteros asignen a los investigadores informes de sus observaciones, es frecuente que estos solo le brinden al portero información muy general.

El hecho de puede existir un lapso significativo entre el acceso al escenario y la iniciación de la observación, o que en ocasiones no se consienta el acceso al investigador, son algunas de las adversidades que los autores consideran importante tener en cuenta en el diseño de la investigación.

Cuarto acápite

Cuando el investigador se encuentra en escenarios públicos (parques, edificios gubernamentales, aeropuertos, estaciones ferroviarias, playas y etcétera) o semipúblicos (establecimientos privados como, bares, restaurantes, teatros, negocios, etcétera), los autores aluden a Steven Prus, quien sugiere ubicarse en los puntos de mucha acción. Es decir, aproximarse a las personas y emprender una conversación casual.

Los autores advierten de la importancia de ''asumir un rol aceptable'' cuando el investigador permanecerá en lugar por un tiempo determinado. Aconsejan, ''Identifíquese antes de que la gente comience a dudar de sus intenciones, en especial si está en envuelta en actividades ilegales o marginales.''

Quinto acápite

En cuanto a escenarios privados, Taylor y Bogdan establecen que la técnica para ''lograr acceso a escenarios y situaciones privados es análoga a la del entrevistador para ubicar informantes. Tanto a los escenarios como los individuos hay que encontrarlos; el consentimiento para el estudio debe ser negociado con cada individuo.''

Los autores describen una técnica para ganar acceso a escenarios privados denominada bola de nieve, esta consiste en ganar la confianza de una pequeña red de personas y que estas nos introduzcan a más, y así, paulatinamente se construya una red de contactos.

Taylor y Bogdan establecen que existen cuatro tácticas por donde comenzar.

En primera instancia comenzar a averiguar con contactos personales.

Segundo, que el investigador se comprometa con la comunidad que quiere estudiar.

En tercer lugar, concurrir los mismos establecimientos y organizaciones sociales que el sujeto de estudio.

Y cuarta, el hacer uso de la publicidad.

Sexto acápite

Determinan los autores que no es conveniente explicar con detalle los pormenores relativos a la investigación o la fidelidad con la que se hará la recolección de información.

Señalan que el investigador debe ser ''veraz, pero vago e impreciso.'' Nunca engañar deliberadamente, pero tampoco hacer sentir al sujeto demasiado observado para no inhibir su comportamiento.

Una forma efectiva sería argumentar que el investigador no se encuentra especialmente interesado en esa organización o personas específicas. Los autores arguyen que en todas las investigaciones ''los intereses del investigador abarcan más que un escenario particular''.

Frecuentemente los porteros poseen cierta aprensión a la investigación por temor a las consecuencias de los descubrimientos, o por temor a que la investigación consista de métodos intrusivos que perturbe de algún modo el escenario, por lo que es común que los porteros demanden elaboras explicaciones sobre la metodología, o expresen preguntas críticas sobre el diseño de investigación y quieran establecer ciertas garantías (pactos).

Aconsejan los autores, que los investigadores anticipen estas problemáticas y tengan respuestas preparadas, ''bastará con una consideración superficial e imprecisa de los métodos de investigación cualitativos, la teoría fundamentada, etcétera.''

Séptimo acápite

De manera muy breve los autores indican que durante el proceso de lograr el ingreso a un escenario es importante llevar de forma detallada un control de observaciones ya que estas al final, por más triviales que parezcan, proveerán al investigador de valiosa información.

Expresan los autores, ''El proceso de obtener acceso a un escenario también facilita la compresión del modo en que las personas se relacionan entre sí y tratan a otros.''

Octavo acápite

En cuanto a la investigación encubierta, los autores indican que esta ''suscita graves problemas éticos''.

Hay científicos sociales como Jack Douglas que consideran que el engaño es parte de la cotidianeidad, por lo que no es vital ser franco con el informante. Por el contrario, antropólogos como James Spradley, defienden el ''derecho a no ser investigado'' de las personas.

Otros como Norman K. Denzin opinan que el propio investigador debe tener la plena libertad de suscribirse a las conductas éticas que encuentre oportunas.

Por último, están los que opinan que el fin justifica los medios, y si los resultados de la investigación proveerán de beneficios a la sociedad, es lícito no ser del todo veraz. Los autores son de este criterio, aunque si bien, no abogan por el engaño abierto con el simple objetivo de cumplir con alguna obligación o ambición académica, reconocen que existe una escasez de investigaciones a grupos que concentran poder, y establecen que ''estudiar de modo encubierto los grupos poderosos puede resultar recompensatorio*''.

Al finalizar, los autores también aluden al hecho de que toda investigación guarda cierta deshonestidad, el investigador nunca es completamente veraz debido a que no es posible explicar el proceso de investigación al sujeto de estudio, ya sea por su cualidad abstracta que exige de un análisis imperioso o, por la cualidad emergente de la investigación que no provee al investigador de resultados claros inmediatos.

En conclusión, este capítulo aborda las cuestiones fundamentales de tomar en cuenta a priori a la observación participante, desde la conexión con nuestros sujetos de estudio como la selección de escenarios.

Bibliografía:

Taylor, S.J. Y R. Bogdan. ''La observación participante. Preparación del trabajo de campo'' Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. Edit. Paidos Basica, España, 2000, pp. 31-49

#2019#Observación participante#S. J. Taylor#R. Bogdan#Métodos y Técnicas de Investigación Antropológica

0 notes

Text

Grounded Theory and Photography

Robert Wilson

Blog Post 3

4th November 2019

For my MA Photography project, I am considering the use of Grounded Theory as a research methodology that I can apply to my photographic data collection and analysis. Before I can implement this research paradigm, it is important to consider its suitability for use in a photographic project. This article will examine how a photography project can generate a theory which demonstrates the potential of Grounded Theory for the medium.

Robert Frank’s The Americans: the creation of a theory of place in photography

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that was first revealed to academia by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in their ground-breaking work The Discovery of Grounded Theory (1967). Strauss’s successor and collaborator Juliet Corbin summarises Grounded Theory as

‘… a form of research the purpose of which is to construct theory from data. The methodology is carried out through a set of data gathering and analytic procedures. Procedures should be used flexibly and reflect the analytic task at hand. Researchers can’t pick and choose among the procedures deciding to use some and discard others. It is the flexible use of procedures that lead to the development of rich and dense theory that fits the data and that offers insight and solutions to the issues and problems of participants.’ (Corbin, 2017)

Whilst Grounded Theory was originally used in nursing studies, it has now become widely applied across academic disciplines. This article will explore the appropriateness of Grounded Theory as a framework for photographic research. It will not provide cases of photographers using Grounded Theory as there is no explicit evidence in the literature that photographers have consciously applied the paradigm but will illustrate its suitability for photography by showing how artists can built theories within their work. To do this, we will examine the clearest and most well-known example of a photographer creating a theory – Robert Frank’s The Americans (2008).

The Americans and its Theory of America

Frank’s The Americans (2008), first published in 1958, was not initially popular, and the majority of reviews were critical. Yet, it has come to be regarded as a seminal work of documentary photography. Uniquely at the time, the work was not solely about aesthetics or creating a single narrative but constructed a theory of America. The book is not an ode to American, but is,

‘…ambiguous, destabilized, ‘moving’ photography that engages the viewer in a dialogical process rather than transmitting a ready-made story with its pre-packaged values and assumptions.’ (Campbell, 2003, p. 214)

The book turns a critical eye on America and that America is, most particularly, one of flags, of automobiles, jukeboxes, and religion, and of racism. It must be noted that Frank’s theory of America does extend beyond the three features above, but for the necessity of brevity, this article will focus on these alone. For greater exploration, the reader is encouraged to engage with The Americans itself as well as Robert Frank's 'The Americans': The Art of Documentary Photography (Day, 2011).

Flags

Robert Frank - Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey (1955/56)

The Stars and Stripes is central to the arrangement of the book (Day, 2011, pp. 71-76). They are the placeholders that begin each new ‘chapter’ (p. 71). In each of the images that feature the flag, the people present are subordinate to it. For example, in the opening image of the book Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey, Day notes that the women in the image are

‘… marginalized, cramped into the corners of the composition. They appear no more important in the image’s visual hierarchy than the wall which divides them. These women are fitted into this block not because it suits them or is a desirable residence, but because there is nowhere else they can go.’ (p. 72)

As we proceed through the book, the flags continue to appear. For example, in Fourth of July – Jay, New York, a tattered flag overshadows a party, yet the participants are seemingly unaware of its presence. In the last image to feature a flag, the amusing Political rally – Chicago (the second image in the book to carry the name), the bandsman is subsumed by his sousaphone: the instrument dominates and his identity is hidden (pp. 75-76). In Frank’s America, flags are a constant theme, and even if the responses of those featured in the images are not consistent (p. 76), the people themselves are always of secondary importance.

Automobiles, Jukeboxes and Religion

Frank’s America has three religions: Christianity, jukeboxes and cars. Christianity, represented by crosses both real and implied, features throughout the book. Juxtaposed against this are both the automobiles, which are not new, but are ‘older models, junked cars, or accidents on the side of the road’ (Mortenson, 2014, p. 425), and the jukeboxes which serves as altars for people of every background. The country worships before all three.

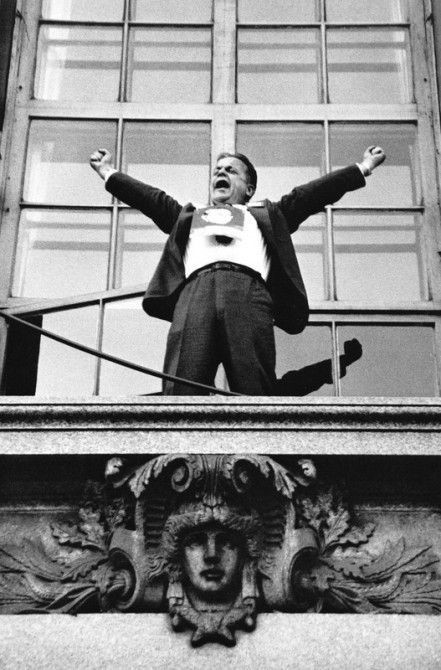

Robert Frank – Political Rally – Chicago (1955/56)

Political Rally – Chicago (the first image to carry the name) is the first of the implied crosses to feature. The figure, with arms spread wide and high, appears almost crucified on the cross formed by the window above. His expression is either triumphant or a grimace of pain. Halfway down his chest is a black patch. This maybe shadow but appears more like a stain. Was this the entry point for his Spear of Destiny?

This image and Jehovah’s Witness- Los Angeles feature implied crosses, but the work also features multiple ‘real’ crosses. Christianity is the overriding faith in the book, but Frank shows that it is not the only faith.

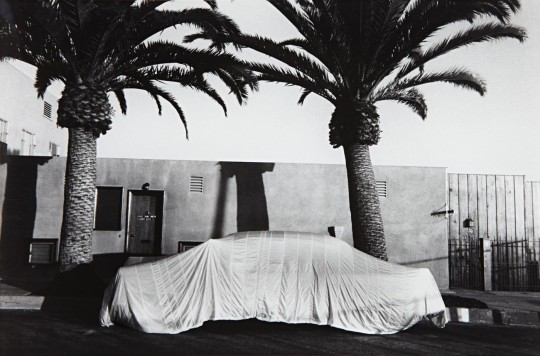

Robert Frank – Covered Car – Long Beach, California (1955/56)

In Covered Car – Long Beach, California, the anonymous car has become the altar in the church of the automobile. As Day (2011, p. 62) points out,

‘The photograph depicts a car covered in a cloth. The cloth appears to be silk, perhaps a parachute or something similar. The richly adorned car stands between two palm trees, which create the impression of a portico. The car thus becomes an altar, complete with altar cloth.’

For the rest of the work, the automobile is a frequent feature. It is a constant facet of everyday life in The Americans. Its variety of appearance include as a simple mode of transport, at a funeral, as an intrusion, as a place to sit during a movie, and finally as a place of rest in the final image of the book. The presence of the car cannot be escaped and it is an inclusive faith. However, only one other image consecrates the automobile as overtly as Covered Car – Long Beach, California, and that is St. Francis, gas station, and city hall – Los Angeles.

Robert Frank – St. Francis, gas station, and city hall – Los Angeles

Here, the statue, which Frank names as St. Francis,

‘…preaches directly across a deserted highway, into the sun. … St Francis is famous for his sermon to the birds. … Here he preaches to an audience of automobiles.’ (p. 88)

The cars appear, flock like, crammed between the two buildings waiting on every word. By being blessed or preached to by St. Francis, the image inescapably marks the cars as part of America’s religion.

Robert Frank – Bar – New York City (1955/56)

In Bar – New York City, the jukebox glows ethereally as if beckoning converts with a mystic light. Day (p. 143) describes it as ‘a modern-day Gabriel trumpeting in song the arrival of a new age’ and notes that the figures present in the bar seem to take little notice of its radiance. This jukebox wants to convert more to its cause even if, as in this image, few are listening.

However, in images such as Candy Store – New York City, the jukebox, like the car in Covered Car – Long Beach, California, becomes an altar. This time surrounded by young people who informally worship at it. Like the car, the jukebox is inclusive in its conversion of followers. This is illustrated effectively by Café – Beaufort, South Carolina. Here, a small African American baby is sprawled face first on the edge of a large cushion. The child is dwarfed by an enormous jukebox which seems to watch over the child in a protective, almost angelic fashion. Despite the child’s potential exclusion, on account of its ethnicity, from much of what 1950s America has to offer, the jukebox is there for him or her regardless of background.

Belief and its paraphernalia, conventional or otherwise, is a consistent theme of Frank’s America. It is one of the key theories that underpin The Americans as a critical description of 1950s America.

Racism

Whilst racism is frequently alluded to in the book, one images confronts it directly. That picture is both the book’s cover and arguable its most well-known. It is Trolley – New Orleans.

Robert Frank - Trolley – New Orleans (1955/56)

The message of segregation is clear in this picture of a racially divided America. The white passengers are in the front and the black passengers the back. They are separated by a divide. However, the image offers us more than a simple reading. As Sturken and Cartwright (2009, pp. 19-20) note,

‘It is as if the trolley itself represents the passage of history… The trolley riders seem to be held for one frozen, pivotal moment within the vehicle, a group of strangers thrown together to journey down the same road that would become so crucial to American history…’

This analysis can be taken further still. In the centre of the picture, we see two children, innocent of expression; it is they who are necessarily the central focus of the image. It is the minds of children that are to become the battleground. If the children cannot be persuaded of the folly of racism and segregation, then America’s future is a bleak one.

Racism is also seen in a wider but less overt context than segregation in the South in the image San Francisco.

Robert Frank - San Francisco (1955/56)

In this image, Frank surprises and photographs a black couple relaxing above an apparently wealthy white-washed suburb. However, they are separated from it excluded from the gleaming buildings and affluence. Professor Maurice Berger, writing in the New York Times notes that,

‘Rather than a neutral observer, Mr. Frank looms over them, an active, unseen participant — a surrogate for the intimidating whiteness that shadowed the lives of black Americans, no matter how liberal their environment.’ (2015)

It is clear from these two images as well as others in the book that the racism of mid-1950s America is an integral feature of Frank’s theory. Whilst is never again confronted so overtly as in Trolley – New Orleans, it is a constant theme.

The Connection to Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory did not exist as a research paradigm when Robert Frank was completing his work on The Americans. If it had existed, we can be confident that Frank would been neither aware nor interested in its potential as a photographic research tool as his great project was not an academic exercise. However, this does not obviate the realisation that he created a theory of America in his work. His theory is individual and subjective, but, nonetheless, it is a theory.

Since its creation Grounded Theory has consistently shown that it can be an effective method of generating theory in research. Additionally, it is axiomatic that qualitative research methods in general are subjective in nature. Therefore, if we accept that a body of photographic work can generate theory, and Frank’s work suggests the truth of this, it seems entirely appropriate to accept that Grounded Theory can be used a method of theory generation for a photographic research project.

References

Berger, M. (2015). The New York Times. [Online] Available at: https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/01/15/robert-frank-telling-it-like-it-was/ [Accessed 6 11 2019].

Campbell, N. (2003). 'The look of hope or the look of sadness': Robert Frank's dialogical vision. Comparative American Studies An International Journal, 1(2), pp. 204-221.

Corbin, J. (2017). Grounded Theory. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), pp. 301-302.

Day, J. (2011). Robert Frank's 'The Americans' The Art of Documentary Photography. Kindle ed. Bristol: Intellect.

Frank, R. (2008). The Americans. 11 ed. Gottingen: Steidl .

Glaser, B. & S., S. A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. 1st ed. Chicago: Aldine.

Mortenson, E. (2014). The Ghost of Humanism: Rethinking the Subjective Turn in Postwar American Photography. History of Photography, 38(4), pp. 418-434.

Sturken, M. & Cartwright, L. (2009). Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

0 notes

Photo

Difference Between Grounded Theory and Ethnography Difference Between Grounded Theory and Ethnography Definition Grounded theory and ethnography are two qualitative research methodologies. Grounded theory, developed by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, is a methodology that involves developing theory through the analysis of data.

0 notes

Text

Juniper publishers-Aging In Grace and the Effects of Social Isolation on the Elderly Population

Abstract

Our conception, birth and developmental processes are as a result of human cooperation which establishes a necessity of our dependence on others for success, personal progress and well-being. Without this cooperation our full growth into adulthood will be grossly hampered. This article will discuss such cooperation and confirm the reality that we are summed by the contributions made in our lives by people we have been privileged to encounter in our journey of life.

It identifies successful aging or aging in grace within a framework of factors and conditions that encourage the potential development of the 'untapped reserves' of the elderly population. It is also aims at demonstrating how social isolation is a problem in the general wellbeing of the elderly population and "social death” as a devaluation of the humanity of others and of the human person in general. Finally, it recommends social support systems as imperative in promoting general well-being among older adults.

Introduction

In the light of our collective cynicism and stereotyping of aging and the elderly—elderly people are sick, elderly people are ugly, elderly people are obsolete, the question arises: is there any hope to age in grace or successfully, and experience some kind of tranquility and happiness in the process, and what would that entail? Aging in grace, graceful aging, successful aging, optimal aging, positive aging, productive aging, active aging, adaptive aging, or aging well, are all ideas without universally accepted definitions. A focus on aging includes concepts such as health, life satisfaction and quality of life and genetic, biomedical, behavioral and social factors.

Aging in Grace and Other Nuances

The terms aging in grace, graceful, successful, positive or optimal aging are usually used interchangeably, but, according to many gerontologists these terms focus on life-style choices that promote quality aging, and therefore minimize age-related problem. The term successful aging was made popular by Rowe and Kahn [1] in order to describe quality aging well into old age. Aging in grace is one of the ways of describing the other ways of growing old happily, successfully and normally, or the average aging development as assessed on any measure and with any age definition, and pathological aging, which incorporates acute or chronic disease that hampers a normal aging pattern and accelerates decline. Many people, view aging as 'something to be denied or concealed', but aging in grace and successful aging have to do with 'aging well' which is not the same as 'not aging at all'.

Successful aging is no longer an oxymoron but a reality. Nevertheless, a standard or uniform definition for successful aging still does not exist. Part of the problem in defining the term is a lack of consensus on what aging is, when it starts, and finding general criteria for success, since social and cultural values both play a role in the definitions [2]. Successful aging can be defined as the process of promoting gains and preventing losses through a process called 'Selection, Optimization and Compensation' (SOC). An inclusive definition of successful aging necessitates a value-based, systemic, and an ecological perspective. Both subjective and objective indicators need to be considered within a given cultural context with its particular contents and ecological demands. The solution according to Rowe and Kahn [1] is thus to use various subjective and objective criteria for successful aging, focusing on individual variability within a given culture.

Successful aging is the result of the interaction between an aging individual within his or her society over the life span, and can also be described as the process of 'adaptive competence'with regard to the challenges of later life, using both internal and external resources. Since dynamics in society influence the aging process, successful aging is not solely an inherent quality of an aging person. There is a bidirectional relationship between an aging individual's adaptive competence and the developmental tasks of society. Successful agers appear to fare well on developmental tasks. There does not seem to be clear scientific agreement on a definition of developmental tasks, but Featherman et al. [3] describe them as sequences of tasks over the life course whose satisfactory performance not only is important for the person's sense of competence and esteem in the community, but also serves as preparation for the future. Developmental tasks require using one's cognitive, emotional and behavioral skills to manage one’s life circumstances. Examples of adaptive competence include gathering social support, maintaining independence as far as possible and adjusting well to retirement. Featherman et al. [3] are of the opinion that as aging progresses, ill-structured tasks out-number well-structured tasks. Well-structured tasks are sometimes defined as problems with standard solutions or techniques, and ill-structured tasks as more ambiguous problems with relative solutions. Reflective planners tend to fare better in retirement because of their accumulated expertise in solving ill-structured problems.

I. With Rowe and Kahn, we identify three key aspects in successful aging

i. preventing disease and disability as far as possible, inter alia through good lifestyle choices,

ii. continuing with mental and physical exercise throughout the life span, and

iii. Keeping up an active life-style, by being productive and by fostering strong social relationships.

This identification was based on the 10-year MacArthur study involving a multi-disciplinary team of professionals that wanted to answer three questions:

i. the meaning of successful aging,

ii. what can be done to age successfully, and

iii. What changes are necessary in American society to facilitate successful aging.

This equally helped with a paradigm shift away from conceptualizing aging as more focused on disease and disability, to a more hopeful approach. However, research confirms that few very old people (older than 90 years) age successfully. Thus, the concept aging in grace, Ihenetu [2] suggests is more 'comprehensive' than successful aging, because aging in grace focuses on 'quality of life and a sense of well-being' despite age- related decline or ill health. Successful aging for some researches is an idealized term that is not necessarily in accordance with the present reality of aging, due to the fact that restrictive factors such as ageism, affordable housing, adequate income and quality healthcare are not taken into consideration. On the other hand, the value of successful aging lies in understanding that an individual can contribute to aging well, for example through specific activities or life-style choices. Nevertheless, few elderly people fit neatly into the categories of successful, normal or pathological aging for all capabilities and suggests that one should maximize successful aging in the capabilities one can control as early in life as possible, employing preventive measures to delay age-related decline for as long as possible.

Social Death and Social Isolation Among The Elderly Population

With the advance of science and modernity, the meaning and understanding of death has been evolving. Death can be defined on a variety of different levels but most people define death as a physical event in which there is a cessation of all bodily functions including beating of the heart. Some in the medical field will broaden this to include 'clinical' or 'biological' death. The 'social death’ phrase evolved and relates to those who die in a social sense consequent to degeneration of the brain or disease, which limits interaction with those around them.

The first available presentation of social death came from Glaser and Strauss (1966), during a discussion of 'hopelessly comatose’ patients, these authors describe their receipt of 'nonperson treatment from hospital personnel when talking freely about things that would matter to the conscious patient. They said that socially he is already dead, though his body remains biologically alive. They also describe some 'senile patients' as 'socially dead as if they were hopelessly comatose’ in the eyes of the families who consign them to institutions and thereafter fail to visit. Some individuals according to Ihenetu [4] regard certain health challenges as a result illness or old age as a social death in which the person is no more connected to society and is dying a little at a time with no hope for recovery. A person's true worth does not diminish as a result of certain health challenges, it becomes an assault for a system of society to diminish and devalue the humanity of others as socially dead or insignificant based on the condition of life.

It is important to debate the idea as to whether elderly persons who are faced with the challenges of old age can be considered socially dead because how they are perceived would directly correspond to how they are cared for and valued in society. A good place to start would be to ask the question; what it is that makes an individual into a whole person? What is it that would allow one to say that an individual has a worthwhile life or life of value? The perception of social death may have some correlation to anticipatory grief that precedes the impending death of an elderly patient. What this means is that the caregiver or family member who is in the position of contributing to the social life of the individual might have given up long before exhausting every available opportunity to communicate. Labeling someone as socially dead is a serious allegation. In essence, it is the end of an individual's social existence. It might even be considered as a self-fulfilling prophecy that could speed up actual physical death. Social death occurs when a person is treated as a corpse although he or she is still clinically and biologically alive. For instance, this is much like allowing someone who was brought into a hospital in a near death state to remain on the stretcher overnight for the fear of unnecessarily having to dirty a bed. Social death does not always lead to biological death nor is it a definite concept.

A survey by Pat Robertson (2011) which referred to Alzheimer’s patients as socially dead, 100% of the responses received from surveys sent out to caregivers show otherwise. When specifically asked if those with Alzheimer's are to be considered socially dead, here below are some of the responses received from caregivers: "Absolutely not; each time my father saw me I could see a twinkle in his sad blue eyes. He did not know my name but he called me pretty’. Another said, 'Not at all - we still can enjoy church; sing and he still goes to Sunday school but does not recall anything except the Lord 's Prayer” To the same question, a Hospice Medical Director writes 'No, because they are still relational to the family to which they belong. They interact with loved ones even until death.' Another doctor who specializes in geriatrics notes, "In those with advanced dementia though the interaction/conversation may be basic or repetitive, they can still interact and thus are not socially dead.” A palliative care doctor said, "I believe they are far from socially dead. Although they may not be able to verbalize, they do communicate in other ways - why can’t people see it?”

Self-perceived social death occurs when an individual accepts the notion that he or she is as good as dead. When a patient is given a terminal diagnosis, it can be a cause to precipitate such thought. However Kastenbaum [5] is of the view that social death must be defined situationally. In particular, it is a situation in which there is absence of those behaviors which we would expect to be directed towards a living person and the presence of behaviors we would expect when dealing with a deceased or non-existent person. Thus, although an individual may be potentially responsive and desperately seeking recognition and interaction, that individual will by this definition be socially dead if others cease to acknowledge his or her continued existence. Consequently, it is paramount to get this right. Non-cognitive or elderly persons should never be looked upon as those who cease to have continued existence [4].

On the other hand, when we look at social isolation among elderly adults, we discover that there are so many researches on the effects of isolation on children and young adults, but only a few on the effect of isolation on the elderly. However, the human need for social connection does not fade away among the elderly, which is to say, the elderly have the need for social connections. Decline of social connection is considered one of the various interrelated factors which compose well-being among the elderly. Hence, it is necessary and important to deepen the knowledge about social isolation among the elderly. According to some authors, social isolation is a subject concerned with the objective characteristics of a situation and refers to the absence of relationships with other people, that is to say, they believe that persons with a very small number of meaningful ties are socially isolated, (ibid.,35).

Meanwhile, Ihenetu [4] enumerated five attributes of social isolation as: number of contacts, feeling of belonging, fulfilling relationships, engagement and quality of network members. Consequently, even loneliness, depression symptoms and their temporal connection are not attributes of social isolation, but those concepts can be causes of being socially isolated. Therefore, lack of a sense of social belonging, lack of social contacts, lack of fulfilling and quality relationships, psychological barriers, physical barriers, low financial/resource exchange and a prohibitive environment can be possible reasons leading to social isolation.

Turning to the effects of being socially isolated, it has been associated with increased vascular resistance, elevated blood pressure, impaired sleep, altered immunity, alcoholism, progression of dementia, obesity and poorer physical health. In other words, socially isolated individuals have a higher possibility of suffering from health issues. Also, drinking, falls, depressive symptoms, cognitive decline and poor outcome after stroke, nutritional risk, increased rates of re-hospitalization, loneliness and alteration in the family process were are also specific effects of social isolation. These truly existing negative effects prove that social isolation has a far-reaching impact on elderly well-being.

Its effects on the elderly well-being are phenomenona which cannot be ignored. The socially isolated elderly persons are among the risk group for myriad other negative health consequences, such as poor nutrition, cognitive decline and heavy alcohol consumption. Therefore, social isolation has a non-ignorable influence on elderly well-being [4]. It is more prevalent in older adults due to diminished vitality and health. In other words, diminished vitality and health are direct causes for being socially isolated among the elderly. Simultaneously, vitality and health are considered a vital dimension of elderly well-being. In sum, the relevance between elderly well-being and isolation is arising from interaction.

Isolation

Working Definition

'Belonging' is a multi-dimensional social construct of relatedness to persons, places, or things, and is fundamental to personality and social well-being. If belonging is connectedness, then social isolation is the distancing of an individual, psychologically or physically, or both, from his or her network of desired or needed relationships with other persons. Therefore, social isolation is a loss of place within one’s group(s). The isolation may be voluntary or involuntary. In cognitively intact persons, social isolation can be identified as such by the isolate.

Some researches portray social isolation as typically accompanied by feelings related to loss or marginality. Apartness or aloneness, often described as solitude, may also be a part of the concept of social isolation, in that it is a distancing from one's network, but this state may be accom¬panied by more positive feelings and is often vol-untarily initiated by the isolate. Some researchers debate whether apartness should be included in, or distinguished as a separate concept from, social isolation. Social isolation as we can see has several definitions and distinc¬tions, dependent upon empirical research and the stance of the observer.

When Isolation Becomes A Problem