#Giambattista Bodoni of Parma

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Omg lol ?????

Giambattista Bodoni thinking Napoleon was blind af

#😂💀#Giambattista Bodoni#Bodini#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Iliad#the Iliad#book binding#printer#Giambattista Bodoni of Parma by T. M. Cleland (1916)#Parma#Giambattista Bodoni of Parma#books#history#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#19th century

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

#esposizionegraficaedesign2024#francomariaricci#FrancoMariaRicci:l'operaalNero#l'operaalnero#mostregraficaedesign

0 notes

Text

Also, from the Discworld fan wiki

"Boddony, Goodmountain's "fiancee's" name is a reference to "Bodoni" a well-known typeface that was designed at the end of the eighteenth century by Giambattista Bodoni, an Italian printer who became the Director of the Press for the Duke of Parma."

Here I am when I'm meant to be asleep, silently yelling TERRY!! because I just realized that the dwarf Goodmountain in The Truth is the literal definition of Gutenberg. 🤦🏻

422 notes

·

View notes

Text

TÍTULO: Giambattista Bodoni

AUTOR: Andrea Appiani

FECHA: 1799

TÉCNICA: Óleo sobre lienzo

DIMENSIONES: 60,3 x 51,2 cm

ORIGEN: Parma, Academia de Bellas Artes, donada por Margherita dell'Aglio en 1841

INVENTARIO: GN. 341

Información e imagen de la web del Conjunto monumental de la Pilotta, Parma.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Typography Tuesday: Bodoni

Among the most prominent of 18th-century type designers was the great typographer, compositor, printer, and publisher Giambattista Bodoni in Parma, Italy. Bodoni was especially influenced by the type designs of French type founder Pierre Simon Fournier and the English type designer and printer John Baskerville. Bodoni, along with the French type founder Firmin Didot, established a style of type design that became referred to as “modern,” and in the 20th century is called “Didone,” a term that combines the names of Didot and Bodoni. Bodoni’s typefaces are not revived classical forms, but new, rational designs characterized by a strong contrast between the thick and thin parts of the type body.

After a nearly 20-year period of training, Bodoni became the type designer and printer for the new ducal press at Parma in 1768, where he would spend the rest of his career until his death in 1813. Shown here are examples from Bodoni’s early and later work:

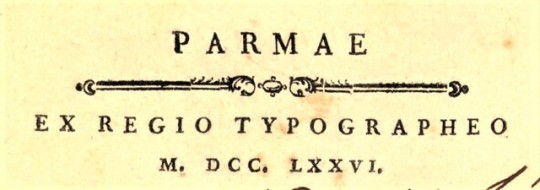

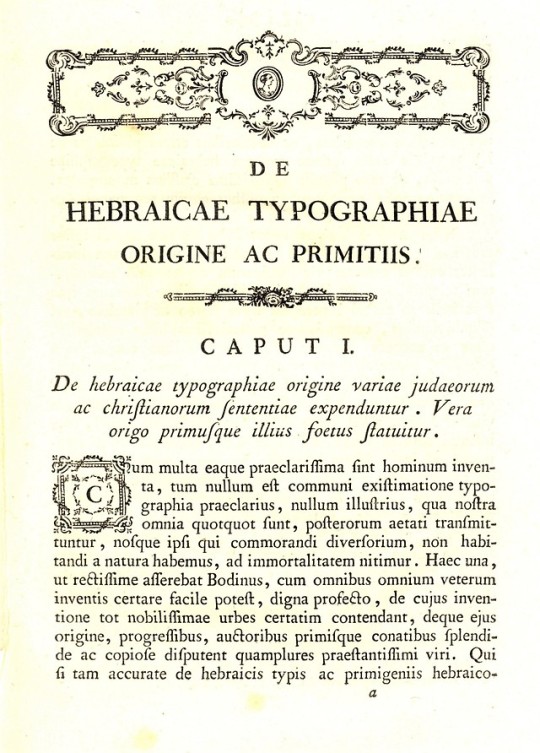

Giovanni Bernardo De Rossi. De hebraicae typographiae origine ac primitiis seu antiquis ac rarissimis hebraicorum librorum editionibus seculi xv. Parmae: ex Regio typographeo, 1776.

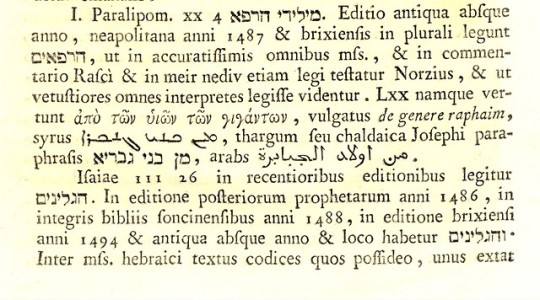

Torquato Tasso. Aminta, Favola boschereccia di Torquato Tasso; ora alla sua vera lezione ridotta. Crisopoli (i.e. Parma): Impresso co' tipi Bodoniani, 1796.

The first displays examples of his many fonts for different languages, including Latin, Hebrew, Greek, Syraic, and Arabic. The second displays his classic font (in Italian) in both Roman and Italic. When Bodoni began working for the Duke of Parma, his imprint would usually appear as ex Regio typographeo, without Bodoni’s name (as in the 1776 example above), but one knows this is by Bodoni because he was the only royal typographer from 1768-1813. In 1791, however, as a way to convince Bodoni to remain in Parma, the Duke allowed Bodoni to establish his own private press, and after this period we begin to find Bodoni’s name in the imprint, as we see in the 1796 printing above.

The 20th and 21st centuries have seen an extended revival of Bodoni typefaces in both cold type and digital versions. The 20th-century German-Italian typographer and fine-press publisher Giovanni Mardersteig, was so taken by Bodoni’s type designs, that when he founded his own private press in 1922, he obtained from Italian authorities the exclusive right to utilize a selection of Bodoni’s original matrices, naming his well-known press Officina Bodoni, which continued to produce quality hand-press work to the end of the 20th century under the direction of Mardersteig’s son Martino, the proprietor of Stamperia Valdonega, which was also founded by Martino’s father in 1948.

View our other Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#Giambattista Bodoni#Bodoni type#Didone#Parma#Giovanni Mardersteig#Martino Mardersteig#Officina Bodoni#Stamperia Valdonega#18th century#18th century type#18th century printers

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Italian publisher, editor and collector Franco Maria Ricci has died at the age of 82.

In sumptuously produced art books, and as editor of the bi-monthly art magazine FMR, Ricci published writing by Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco, Roland Barthes and many others over the course of his long and distinguished career. In 2019, Susan Moore visited his estate at Fontanellato, near Parma, where in recent years Ricci had constructed the largest labyrinth in the world out of bamboo; they discussed Ricci’s notable collection of largely 18th- and 19th-century sculpture and paintings, as well as his library of books published by the great typographer Giambattista Bodoni, whose works Ricci had reprinted in his first foray into publishing. The interview is published in full below.

Collecting may be read as a form of autobiography written with works of art rather than words. In the case of Franco Maria Ricci, his is a life composed of both words and pictures. He has not only published the most lavishly produced art magazine – FMR – and art books in the world, but also spent the last 50 years amassing a peerless collection of volumes produced by the great Italian typographer, compositor and publisher Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) and a rich, eclectic collection of some 500 largely neoclassical and baroque paintings and sculptures. Both collections are at the heart of his most recent and extraordinary venture, the creation of the immense, star-shaped Labirinto della Masone, near Parma, the largest labyrinth in the world – and surely one of the few planted with bamboo.

There is something surreal, and slightly disturbing, about turning off the autostrada and suddenly encountering this majestic bamboo structure rising 10m or more above the plains of the Po valley. For all its elegant calligraphic stems and angular leaves, this is not the sparse specimen bamboo of Chinese ink-painting, but a forest. Here, more than 200,000 of these fast-growing bamboos arch upward in their quest for light. Once I turn into the drive of what was originally Ricci’s grandfather’s estate at Fontanellato, the brilliant azure June sky all but disappears. By the end of my two-day visit, it seems that the contrasts of light and dark are an apt metaphor for the book and art collections – and for the entire complex of maze, museum, archive and chapel, the latter built in the form of a pyramid. Ricci has always been part rationalist, part visionary.

Ricci’s story begins with the book. ‘I grew up surrounded by my father’s books. Reading Shakespeare, Homer, Joyce and Dante saved me from bad taste,’ he once said. ‘It made beauty simple, familiar and immediate in my eyes.’ It was a book, too, that transformed his life and launched a long and successful career: Bodoni’s Manuale tipografico, first published in 1818. Before his discovery of Bodoni’s works in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma in the 1960s, a career in publishing seemed unlikely. The stylish Ricci, a racing driver and a dandy with dark cherubic curls, was best known for patterning the snow in the piazza around Parma Cathedral with the wheels of his E-type Jaguar. Even Bernardo Bertolucci remembered that car.

As a young man, Ricci had wanted to study archaeology, but an uncle in the oil world persuaded him to sign up for geology instead. After three months in Turkey spent looking for oil that was not there, he realised the oil business was not for him. Yet his education proved critical in unlikely ways. He spent weekends exploring the mysterious, labyrinthine underground tunnels and caves that are a feature of the Romagna region of Italy. He also designed posters for Parma University’s theatre festival that caught the attention of an American curator preparing a show of Italian design in New York. He became, inadvertently, a graphic artist, and went on to create striking graphics for everything from Poste Italiane to Alitalia.

Ricci has long insisted that ‘Bodoni was not only a typographer. He achieved modernity and elegance through graphic art. He was, like Canova, a champion of neoclassicism but in two dimensions. I immediately fell in love with the proportions, the concept of beauty.’ Bodoni’s genius was not simply the freshness, rigour and precision of the typefaces, with their dramatic contrasts between thick and thin line, but also his sense of how to lay out a page. Texts are set with extravagantly wide margins and with little or no decoration.

Ricci decided to reproduce the master’s Manuale tipografico, although everyone told him he was mad to do it. He bought two early offset typography machines which, he noted, were ‘as expensive as a Ferrari, which I wanted to buy but never did’, and had the highest-quality paper made exclusively for the project by Fabriano. It took a year to publish the three volumes in 900 numbered copies (1964–65). ‘So I became a publisher. It became a bestseller.’

Much to his mother’s horror, Ricci decided to continue to publish very expensive books – art books printed in Bodonian style – and later, literary editions, several series of which were edited by Jorge Luis Borges, whose presence looms large in library and labyrinth. At a time when Arte Povera dominated the Italian avant-garde, Ricci chose opulent black silk covers embossed with gold, and printed on costly pale blue Fabriano paper with handmade plates. He wanted his books to be rare – printing small editions – but also surprising. He gave Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco, Italo Calvino and Borges free rein to write accompanying texts.

His wife Laura Casalis remembers having been struck by the originality of Ricci’s 1970 book on the then little-appreciated Erté – text by Barthes – before she met the publisher himself in 1975, and soon found herself working on a book on red paper-cut portraits of Mao, accompanied by 39 of the Chairman’s own poems printed in Chinese characters. ‘Little by little I slipped into publishing with him – Franco was a workaholic and I realised that was the only way I would see him. Those Mao paper-cuts were typical of the practically unknown subjects that he would seek out all his life, and we sometimes show them between loan exhibitions in the museum. Franco has l’occhio lungo – he can see beauty in something which may take others a long time to recognise.’

It is in the library I find Ricci and, indeed, where he is to be found most mornings and afternoons. It is part of a cluster of picturesque 19th-century stone buildings surrounded by lush and increasingly exotic gardens. He had begun renovating the dilapidated stables behind his grandfather’s long-abandoned villa as a summerhouse and library in the 1970s, and its enormous hayloft still serves as an idyllic open-air dining room and entertaining space, even though the couple have now moved into the main house. Inside this romantic half-ruined folly, Ricci created the unexpected: two neoclassical library rooms lined with bookshelves and marble busts, their domed and coffered ceilings reminiscent of those in the Biblioteca Palatina.

As soon as we arrive in the inner sanctum, the Bodoni library with its more than 1,200 volumes – missing a tantalising three or four tomes but otherwise complete – Ricci is immediately up on his feet and pulling down and opening cherished volumes, eyes blazing. Despite the heat, he wears an elegant embroidered linen waistcoat but not its jacket, which hangs nearby, bearing the synthetic red flower that became in effect his iconographical device. (Tai Missoni gave him a cardigan as a present: Ricci declined the gift – he does not wear cardigans – but declared that he would always wear the red flower from its packaging thereafter, which he did. Once, when he had forgotten the flower, an officer at the Alitalia desk at Milan airport said: ‘I see you are travelling incognito today Mr Ricci.’)

Now Ricci deftly presents Bodoni’s Essai de caractères russes… of 1782, and his 1789 edition of Torquato Tasso’s pastoral play Aminta, exquisitely illuminated for the Prince of Essling. These are dear friends and the joy as he handles these pages is self-evident. This is the only significant part of the collection not to have been moved down to the museum and archive complex, a short bamboo-lined drive away. It is clear that he could never bear to live apart from these books.

The impetus to create the long-imagined labyrinth, and a museum and library to house his collections and publishing archive, was a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The couple sold the publishing house in 1982, and their house in Milan, and moved to Fontanellato. There is a fierce pride in Laura Casalis’s voice as she explains: ‘Franco wanted to do it, he imagined it, and he found the right team of people to help him realise it.’ We are sitting over coffee in the Labirinto courtyard surveying the sharp-edged geometries of its rose-pink brick buildings, a place that already has the air of a lost ancient city discovered in a jungle. Laura describes the evolution of the museum collections within, and recalls the words of the late Italian publisher Valentino Bompiani, who described Ricci as a man of courage and fantasy.

‘Whenever he fell for some subject or artist, Franco would try to buy.’ Laura continues. ‘He was never concerned with what was or was not fashionable, and never bought to decorate a house. He collected pieces that he liked that were strange or unconventional.’ He began with Art Deco, first buying inexpensive little bronze and chryselephantine dancers by the likes of Demétre Chiparus (1886–1947), as well as Guiraud-Rivière’s dramatic figure of Isadora Duncan with two bears, which dominates the central space of the 20th-century gallery in the museum.

Here, too, are three paintings by the outsider artist Antonio Ligabue (1899–1965), a tormented soul who had led a tragic life, painting and wandering around the Po valley when he was not confined to a psychiatric hospital. Ricci published the first monograph on the artist in 1967, two years after his death, a work that helped catapult the artist from provincial to national and then international fame. Two years later, he bought two of the artist’s bold, visceral close-up heads of roaring tigers, painted in the 1950s, including the key work that had been selected for the book cover. A no less bright and richly impasted self-portrait in the guise of Vincent Van Gogh followed a year later.

Ricci also championed – and collected – the work of the third dominant presence in this space, Adolfo Wildt (1868–1931), often described as the last Symbolist but one whose reputation was, as Laura puts it, ‘tarnished by Fascist association’. Ricci published a monograph in 1988, the same year that he acquired the strange masterpiece that is Vir temporis acti of 1913, a virtuoso marble bust of a Greek or Roman soldier reimagined through the combined lenses of Michelangelo and the Secessionists. The expressive anguish of this head may be seen as a symbol of the nobility and redemption of sacrifice, but it is the refined and gleaming silken surface that led to Brancusi.

Ricci has a penchant not only for sculpture but also portraits, and portrait busts in particular. ‘I have hunted portraits all my life. I never get tired of looking at them,’ he confesses, ‘and in turn, I feel observed by them.’ In the 1990s, he began following the art market and collecting in earnest. Ricci had an office, bookshop and apartment in Paris and there and in Monaco he was to acquire many of his largely French 18th-century terracottas, some of the most compelling by less familiar names. A superb example is the bust of an intense, low-browed individual, signed by one A. Riffard and given the Revolutionary date of ‘9. Fructidor an 3e’, from 1794–95.

Another naturalistic tour de force is one of very few known terracottas by Francesco Orso, also known as François Orsy, a Piedmontese sculptor also active in Paris. Orso is responsible for the rarest sculptures here: the disconcerting life-size polychrome wax portrait busts of Vittorio Amadeo III of Savoy and his wife Maria Antonia Ferdinanda di Borbone, complete with painted papier-mâché clothes. The revolution destroyed the sculptor’s courtly patronage in Paris, and he diversified into the more overtly commercial world of the waxwork with a show featuring an effigy of the aristocratic revolutionary leader the Comte de Mirabeau and popular tableaux on themes such as Marat’s assassination by Charlotte Corday.

Unsurprisingly, given Ricci’s passion for Bodoni, the neoclassical looms large. At the centre of the Napoleonic gallery, lined with marble busts – Italian, English and Danish – is a model of Canova’s ideal head of Dante’s muse Beatrice, first conceived as an idealised portrait of Mme Récamier. The display offers a witty face-off between Wellington and Napoleon on opposing pedestals, but the emperor prevails with a sequence of classicising family portraits. Above hangs the second version of Francesco Hayez’s The Penitent Magdalene (1825). Here the Romantic artist has transposed the chilly perfection of Canova’s marble surfaces into pigment.

An unusual and endearing mid 18th-century Italian group portrait presents the family of Antonio Ghidini, a cloth merchant to the Bourbon court in Parma, painted by his friend, the court artist Pietro Melchiorre Ferrari (1734/5–87). In this Zoffany-style conversation piece there is no doubting Ghidini’s business, as he points to documents mentioning his association with his trading partners in Manchester and his wife sits stiffly under her salmon-pink stomacher in sprigged and striped silk finery.

Yet it would be misleading to suggest that Ricci’s ever-curious eye never ranged beyond the 18th and 19th centuries. He owns a number of 17th-century marbles, including that of the all-powerful prelate Cardinal Paluzzo Paluzzi Altieri degli Albertoni, who effectively ran the papacy under Clement X – irresistible in profile. In the 2000s Ricci also added, for example, Ludovico Carracci’s handsome three-quarter length Portrait of Lucrezia Bentivoglio Leoni (1589), executed two years before the sitter’s death. Flanking the same door is Philippe de Champaigne’s Portrait of the Duchesse d’Aiguillon (c. 1650), and viewed beyond is an unusual sensual and erotically charged work by Luca Cambiaso (1527–85), Venus Blindfolding Cupid.

Yet Ricci has also always been attracted to what he describes as the art of visionary madness, by the surreal, and by what is prosaic and popular. The museum’s cabinet of curiosities includes a narwhal horn, once thought to have belonged to the unicorn. Its walls are lined with particularly gruesome vanitas paintings and sculptures. Centre stage among the skulls is a decomposing head by Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627), its flesh and rotten teeth seething with maggots and flies.

Only superficially more benign are the drawings of the Codex Seraphinianus, first published in two volumes in 1981 – Ricci’s most extraordinary publication. These meticulously detailed explications of the bizarre and the fantastical illustrate an encyclopaedia of an imaginary world conceived by the artist Luigi Serafini in the 1970s and written in a language still understood only by its creator. Certainly its pages are at home in the Labirinto della Masone complex – another visionary creation, in effect a Gesamtkunstwerk, an all-embracing art work expressing the life and taste of one man.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adiós a Franco Maria Ricci

por Juan José Mendoza [Revista Ñ, 19 de septiembre de 2020]

En marzo de 1971 Cuadernos del Archibrazo publicó en un suelto de 56 páginas el que para Borges es el “mejor” de todos sus textos: “El Congreso”. “Si de todos mis textos tuviera que rescatar uno solo, rescataría ‘El Congreso’”. La edición del Archibrazo fue leída por Franco Maria Ricci, dueño de una pequeña casa editorial en Parma. Inmediatamente viajó a la Argentina para conocer al entonces Director de la Biblioteca Nacional. En el verano del 72 llegó a Buenos Aires. Cuando Ricci entró a la Biblioteca de la calle México, Borges lo tomó del brazo y le comenzó a hablar en italiano primero, en varias lenguas después: le recitó poemas en español, en inglés y en francés. Como ya era tarde para editar sus obras completas –ya en manos de Mondadori y Feltrinelli–, Ricci le propuso que dirigiera una colección. Así nació La Biblioteca di Babele, la serie de literatura fantástica con textos de Papini, Poe, Melville, Hinton, H. G. Wells...

Al poco tiempo la editorial Ricci se mudó de Parma a Milán. Estos detalles los conocemos por María Esther Vázquez, a quien Borges le dictó algunos de esos prólogos: “Cada dos o tres meses enviaba el material de un nuevo libro a Milán; así se completó una colección de unos treinta títulos”. Treinta y tres exactamente. Desde entonces Ricci sería una figura muy cercana a Borges hasta sus últimos días. Invitado por Ricci para dictar unas conferencias, a Milán es precisamente a donde Borges partió la tarde el 28 de noviembre de 1985, cuando dejó la Argentina para siempre.

En julio de 1984 Borges recibió un regalo sorprendente. Él mismo lo contó así: “Resulta que desde que yo nací, sin saberlo y sin que nadie lo supiera tampoco, he ganado una libra esterlina por año. Eso no parece excesivo, pero cuando al cabo de 84 años uno recibe un cofre con ochenta y cuatro monedas de oro [...], ochenta y cuatro monedas de oro dan la sensación de un capital infinito”. La colección comenzaba con una moneda de 1899 y terminaba con otra de 1983. Ricci organizó el cumpleaños de Borges en la Biblioteca Nacional de Washington. Alquiló la sala de lectura y llevó cuatro cocineros de Parma, para que los tortellini que se sirvieran no fueran inferiores a los que Borges amaba comer en Italia. Hubo unos cuatrocientos cincuenta invitados: “Hablaron muchas personas, me entregaron el premio y yo pensé: Recibo un premio de Italia, un país que quiero tanto, me lo dan en Washington, una ciudad que quiero tanto, y me lo entrega Ricci, un viejo amigo...”

Amante de las tipografías, Ricci se inició en el mundo de la edición en 1963 con la publicación del Manual Tipográfico de Giambattista Bodoni. Entre 1982 y 2002 fue editor de FMR –por sus iniciales, que en francés se pronuncia “éphémére”–, catalogada como “la revista más bella del mundo”.

A Ricci lo atraía la materialización de la literatura borgeana. En 2015 había inaugurado el Laberinto della Masone en Parma, uno de los laberintos más grandes que existen. Cerca de allí, el jueves 10 de septiembre, en un bello día de finales del verano europeo, y después de un almuerzo al aire libre, Franco Maria Ricci se quedó dormido para siempre en su casa de Fontanello. Tenía 82 años. Su fundación [francomariaricci.com] dio a conocer la noticia con un comunicado. Hacia el final se lee: “Sobre su ataúd, el epitafio de Charles Nodier sería apropiado: Aquí yace / en su encuadernación de madera / una copia in folio / de la mejor edición del hombre / escrito en una lengua de la edad de oro...”

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

“Il principe dei tipografi”

Casualmente ci siamo imbattuti in questo estratto dal film “Prima della rivoluzione” anno 1964, diretto da Bernardo Bertolucci, colonna sonora di Ennio Morricone. Sentite il commento del protagonista sul “Signor Bodoni”! Questa fantastica scena è girata nella tipografia G.Ferrari e figli a Parma (dedotto grazie all’occhio attento di Francesco dello studio grafico bunker). Sarebbe interessante capire perché Bertolucci ha prestato tanta attenzione alla tipografia. Qualcuno sa dirci qualcosa?

Buona visione

Ritratto di Giambattista Bodoni del 1799 realizzato da Andrea Appiani (Il dipinto si trova tutt’ora a Parma nella Galleria Nazionale)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Las Tipografías Más Utilizadas En Diseño Gráfico

1. Gotham

Gotham es una tipografía diseñada por Tobias Frere-Jones en el año 2000. Está inspirada en el grupo de las Sans-Serif (palo seco) y del estilo arquitectónico popular de mediados del siglo XX en la ciudad de Nueva York.Muchos comparten que es una tipografía con mucha personalidad y transmite confianza, por esta razón hemos podido encontrarla en diferentes campañas políticas entre las más destacadas la de Barak Obama en el 2008. Por otro lado el programa de música online Spotify, también la utiliza en su versión digital sustituyendo a la Helvetica Neue.

2. Bodoni

Bodoni es una fuente creada por Giambattista Bodoni (Parma, 1740-1813). Una tipografía que combina muy bien los trazos gruesos y finos transmitiendo una gran elegancia. Bodoni ha sido utilizada en revistas como Vogue o Harper’s Bazaar y en muchos de los periódicos de los años 60, incluso por la banda Nirvana.

3. Futura

Futura es una tipografía sans serif diseñada por Paul Renner en 1928. Futura es uno de los tipos de letra más conocidos y utilizados de las tipografías modernas. Varias compañías como Volkswagen, Boeing o Ikea la han usado como parte de su diseño corporativo. En el siglo XX fue muy usada y en la actualidad continúa siendo muy popular.

4. Gill Sans

Gill Sans es una tipografía sans serif o paloseco fue creada por el tipógrafo Eric Gill y publicada por Monotype 1928 y 1930. Ha sido usada en empresas importantes como el metro de Londres y British Railways, y en España la hemos podido ver en Televisión Española entre 1990 a 1997 en toda la grafía y maquetación de los programas.

5. Garamond

Garamond es una tipografía con serif > Romanas clásicas > Antiguas. Creada por Claude Garamond en el siglo XVI en Francia. Una de las más influyentes de la historia y también una de las mejores romanas jamás creadas.En 1984 fue adoptada por Apple para el lanzamiento del Macintosh y fue modificada posteriormente por Myriad.

6. Avant Garde Gothic

Avant Garde es una fuente inspirada en logo de Herb Lubalin en 1970 para la revista Avant Garde Magazine en 1967. Una tipografía geométrica de líneas rectas y figuras circulares basadas en el movimiento Bauhaus de los años 20.

7. Baskerville

Baskerville es una tipografía con serif diseñada en 1757 por John Baskerville en Birmingham. Su gran delicadeza y virtud por el diseño ayudo a influenciar a tipógrafos de la talla de Didot o Bodoni. Estamos delante de una tipografía clara y legible gracias a su diseño (serif) siendo muy apropiada para proyectos editoriales como libros de textos.

8. Franklin Gothic

Franklin Gothic es una fuente sans-serif creada por Morris Fuller Benton (1872-1948) en 1902. Su nombre es en honor al prolífico político, inventor e impresor estadounidense, Benjamin Franklin. Esta tipografía es muy común verla en anuncios y titulares de periódicos.

9. Bebas Neue

Bebas Neue es una fuente creada por Ryoichi Tsunekawa y gracias a su gran popularidad fue nombrada para muchos como la «Helvetica de las tipos gratuitas». Está formada por toda la familia de fuentes: Thin, Light, Book y Regular. Gracias a su elegancia y líneas rectas y la altura de la X, Beabas Neue es ideal para titulares.

10. Akzidenz-Grotesk

Akzidenz Grotesk, es un tipo de fuente paloseco o sans serif diseñada por la fundidora de tipos H. Berthold de la ciudad de Berlín en el año de 1896 por Günter Gerhard Lange. Debido a su gama de anchos es buena opción en espacios reducidos como tablas y titulares de periódicos y revistas.

[Publisher Factory]. Factory by Factory

#tipografia#typography#graphic design#diseño gráfico#garlaydesign#arte#graphic art#graphic#creative#creatividad#designtypography#diseñotipografico#design#agencydesign#bcndesign#diseño

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

La stazione di ricarica per veicoli elettrici EnerMia da 22 kW presso la Camera di Commercio di Parma: in piena ZTL, per cui serve esporre anche il pass https://www.forumelettrico.it/forum/colonnina-enermia-22-kw-camera-di-commercio-parma-pr-via-giambattista-bodoni-8-t27311.html #Parma #EnerMia

0 notes

Text

Die 20 beliebte Schriftarten aller Zeiten

Schriftarten sind seit Jahrhunderten ein integraler Bestandteil der "Lese-Schreib"-Gesellschaft und haben sich heute in das digitale Zeitalter des Typografie-Designs und -Designs entwickelt, in dem Schriftarten weitaus wichtiger sind als je zuvor. Schriftarten beeinflussen in hohem Maße, wie Ihr Textmaterial für den Betrachter aussieht und sich anfühlt, daher ist es wichtig, Schriftarten für Ihre Druck-, Veröffentlichungs-, Webdesign- und anderen Aufgaben sorgfältig auszuwählen. Im Folgenden haben wir eine Liste der beliebte Schriftarten zusammengestellt, aus denen Sie für Ihre Druck- und Designanforderungen auswählen können. Um mehr über Schriftarten zu erfahren, sollten Sie zu https://schriftarten123.com/ gehen und die Schriftarten unten sehen, sowohl das Lesen als auch das Üben wird Ihnen helfen, sich viel besser zu erinnern und zu lernen.

1. Beliebte Schriftarten Helvetica (Max Miedinger, 1957)

Helvetica ist wohl die berühmteste Schrift der Welt. Ursprünglich 1957 vom Schweizer Designer Max Miedinger entworfen, wird diese klassische Schrift seit ihrer Gründung in den 1950er Jahren bis heute überall verwendet. Seine immense Popularität kann darauf zurückgeführt werden, dass es immer noch modern und einfach aussieht und so vielseitig und zuverlässig ist wie es schweizerisch ist.

2. Beliebte Schriftarten Baskerville (John Baskerville, 1757)

Unbeeindruckt von zeitgenössischen "Caslon" -Schriften begann John Baskerville 1950 mit dem Schneiden seiner eigenen Schriften, um seine Drucke zu verbessern, und es debütierte offiziell 1757 in Birmingham als Übergangsserifenschrift (zwischen altmodischen Caslon-Schriften und modernen Bodoni- und Didot-Stilen) mit Kleinbuchstaben mit Serifen. fast horizontal und hervorragender Kontrast. Von vielen Konkurrenten von Baskerville wie Benjamin Franklin und Giambattista Bodoni bewundert, haben verschiedene Gießereien seit seiner Gründung viele Versionen davon produziert, darunter die neue und elegant aussehende "New Baskerville".

3. Beliebte Schriftarten Times (Stanley Morison, 1931)

William Lints-Smith, der 1929 die Londoner Tageszeitung "The Times" herausgab, hörte, dass die berühmte Schreibkraft Stanley Morison von der Druckqualität seiner Zeitung unbeeindruckt war. Beeindruckt von Morisons Argumenten, engagierte der Journalist Morison, um seine Zeitung neu zu gestalten, und 1931 gab Morison seine eigene neue Schriftart, die Times New Roman, und ersetzte seinen Vorgänger, die Times Old Roman. Seitdem ist es eine der häufigsten Schriften, die für viele veröffentlichte Dokumente und Nachrichtendrucke verwendet werden.

4. Beliebte Schriftarten Akzidenz Grotesk (Gießerei im Brethold-Stil, 1896)

Akzidenz Grotesk beeinflusste eine Vielzahl anderer populärer Schriften wie die beliebte Helvetica und Frutiger und wurde erstmals 1896 in Deutschland von Brethold Type Foundry veröffentlicht. Es erlebte eine neue Popularität, nachdem es in den 1950er Jahren unter der Leitung von Gunter Gerhard Lange mit mehr Gewichtsarten und Variationen neu erfunden wurde.

5. Beliebte Schriftarten Gotham (Hoefler und Frere-Jones, 2000)

Gotham wurde im Jahr 2000 veröffentlicht und ist eine Adaption von "Gothic" durch den Produzenten von American Sign aus dem 20. Jahrhundert. In den letzten 16 Jahren hat es aufgrund seines sauberen und modernen Aussehens in der Designwelt an Popularität gewonnen. Unter seinen populären Verwendungen gibt es die Geschichte der Obama-Kampagne, die speziell diese San-Serifen-Schrift bei den Wahlen 2008 verwendete.

6. Beliebte Schriftarten Bodoni (Giambattista Bodo ni, 1790)

Giambattista Bodoni entwarf diese Serifenschrift im späten 18. Jahrhundert im Palast des Herzogs Ferdinand von Bourbon-Parma, der Bodonis Handwerkskunst sehr bewunderte und ihm erlaubte, eine private Druckerei in seinem Palast zu bauen. Bodoni war eine weit verbreitete Schriftart, als Morris Fuller Benton sie in den 1920er Jahren für die ATF mit einem detaillierten Schwerpunkt auf verschiedenen Gewichtungen wiederbelebte. Der Film "Goodfellas" verwendete Schriftarten in seinen Plakaten.

7. Beliebte Schriftarten Didot (Firmin Didot, 1784-1811)

Didot erschien zur gleichen Zeit im späten 18. Jahrhundert als Ersatz für Bodoni, so dass der gegenseitige Einfluss zwischen ihnen offensichtlich war. Diese Schrift ist im Grunde eine dünnere Version von Bodoni, aber sie ist tatsächlich von John Baskervilles Experiment mit hohem Kontrast und kondensierter Haftung inspiriert. Bis heute haben seine verschiedenen Renaissancen vielen modernen Gebäuden zeitlose Eleganz verliehen.

8. Beliebte Schriftarten Futura (Paul Renner, 1927)

Futura wurde von Paul Renner in den 1920er Jahren in Deutschland entworfen und seit seiner Gründung ist Futura seit über 80 Jahren mit seinen bemerkenswerten Formen die Norm der Geometrie. Diese moderne Schrift hat viele andere Designer beeinflusst und ist bis heute in Geschäftsschildern und Werbung weit verbreitet. Volkswagen verwendet es seit Jahren als Titelschriftart.

9. Beliebte Schriftarten Gill Sans (Eric Gill, 1928)

Diese typisch englische Schriftart wurde von der Monotype Corporation produziert und 1928 von Eric Gill entworfen. Eric Gill arbeitete mit Edward Johnston zusammen, so dass Gills Versuch, diese am besten lesbare serifenlose Schriftart zu entwerfen, weitgehend von Johnston beeinflusst wurde, der Johnston-Schriften für die Londoner U-Bahn entwarf. Die Gill Sans-Familie, die heute von vielen Designern weit verbreitet ist, bietet verschiedene Stärken und Schriftvariationen, aus denen Sie wählen können.

10. Beliebte Schriftarten Frutiger (Adrian Frutiger, 1977)

Dieser zeitlose Klassiker wurde 1977 vom berühmten Adrian Frutiger entworfen, um Wegweiser für einen neu gebauten Flughafen in Paris zu zeichnen. Adrian Frutiger veröffentlichte 1957 seine erfolgreiche Schrift Univers, aber er fand sie zu kompakt und geometrisch, um auf Schildern lesbar zu sein. So wurde Frutiger geboren, was Adrian Frutiger selbst für "mittelmäßig und schön" hielt. Adrian Frutiger trug auch zum berühmten "Linotype Didot" bei.

11. Beliebte Schriftarten Bembo (Aldus Manutius, Frank Hinman Pierpont và Francesco Griffo, 1929)

Die britische Niederlassung der Monotype Corporation schuf diese altmodische Serifenschrift unter dem Einfluss von Stanley Morison im Jahr 1929, als der italienische Renaissance-Druck von Interesse war. Im Grunde ist dies eine Wiederbelebung der Serifenschrift, die Francesco Griffo im späten 15. Jahrhundert ausgeschnitten hat. Jetzt bietet es viele schöne Gewichte, Symbole und Ziffernsätze für Designarbeiten.

12. Beliebte Schriftarten Rockwell (Monotype Foundry, 1934)

Rockwell ist eines der berühmtesten Beispiele für Plattenserifenschriften mit dicken, scharfen Serifen und ausgeprägten kühnen geometrischen Formen. Rockwell wurde 1934 von der hauseigenen Designabteilung der Monotype-Gießerei entworfen und ist vor allem als Display-Schriftart beliebt, aber es ist bekannt, dass es jedem Design Eleganz verleiht.

13. Beliebte Schriftarten Franklin Gothic ( Morris Fuller Benton, 1903 )

Franklin Gothic wurde 1903 von Morris Fuller Benton in den USA entwickelt und 1980 neu gezeichnet und 1991 mit einer Vielzahl von Gewichten aktualisiert. Schriftarten dieses realistischen serifenlosen Genres haben mehr Charaktere als jede andere Art von Schriftart in ihnen, und ihre Kühnheit wird von vielen Designern geliebt. Obwohl seine Popularität in den 1930er Jahren nach der Einführung europäischer Konkurrenten wie Futura kurzzeitig zurückging, gewann es bald wieder an Popularität und ist heute bei vielen Menschen für verschiedene Designarbeiten beliebt.

14. Beliebte Schriftarten Sabon (Jan Tschichold, 1966)

Sabon wurde 1966 von Jan Tschichold, einem berühmten Schweizer Grafikdesigner und Schriftdesigner, sowohl aus Monotype- als auch aus Linotype-Maschinen erstellt. Tschichold hat viel zum modernen Grafikdesign beigetragen und der typografischen Welt viele gute Schriften gegeben, aber diese altmodische Serife ist das, was vor allem seine Werke hervorhebt und weit verbreitet ist. Die Einzigartigkeit von Sabon zeigt sich in seinen halbscharfen Kanten und schönen kursiven Details.

15. Beliebte Schriftarten Georgia (Matthew Carter, 1993)

Matthew Carter entwarf Georgia 1993 mit Tom Rickner für die Font-Sammlung von Microsoft. Erstellt als charmante Schriftart für einfache Lesbarkeit und Einfachheit, ist es für niedrig aufgelöste Displays gedacht, um Klarheit mit seinem Verdana-Gegenstück zu schaffen - beide sind weit verbreitet.

16. Beliebte Schriftarten Garamond (Claude Garamond, 1530)

Diese Schrift wurde ursprünglich von Claude Garamond im 15. Jahrhundert während der turbulenten Zeit der französischen Renaissance entworfen. Claude war der Lehrling von Antoine Augereau, einem Drucker und Verleger, der unter seiner Aufsicht seine eigene Cicero-Schrift für den berühmten Drucker Robert Estienne schnitt, der große Bewunderung erhielt. Um 1620 wurde es von Jean Jannon, einem Schweizer Drucker, als Garamond kopiert. Adobe Garamond, 1989 von Robert Slimbach entworfen, ist heute die beliebteste digitale Version.

17. Beliebte Schriftarten News Gothic (Morris Fuller Benton, 1908)

News Gothic ist eine weitere beliebte Schriftart, die von Morris Fuller Benton entworfen wurde und im frühen 19. Jahrhundert in Form von American San Serif populär gemacht wurde, die speziell für die ATF entwickelt wurde. Die Schrift sieht ordentlich und sauber aus mit diesen scharfen Kanten, die von vielen bis heute für Zeitungsdruck, Veröffentlichung und andere Zwecke bevorzugt werden.

18. Beliebte Schriftarten Myriad ( Robert Slimbach , Carol Twombly , Christopher Slye, Fred Brady, 1992)

Myriad ist eine der Originalschriftarten von Adobe, die 1992 speziell für die Adobe-Schriftsammlung entwickelt und entwickelt wurde. Es wurde von vielen Unternehmen und Organisationen als ihre Unternehmensschriftarten einschließlich Apple angepasst.

19. Beliebte Schriftarten Frau Eaves (Zuzana Licko, 1996)

Licko war unglücklich über die digitale Wiederbelebung alter Schriften in dieser modernen Ära der "absoluten Freiheit" und so schuf sie 1996 Mrs Eaves, eine moderne Interpretation von John Baskervilles legendärer Schrift, und benannte sie nach seiner Butlerin (die später Baskervilles Frau wurde) Sarah Eaves.

20. Beliebte Schriftarten Minion (Rober Slimbach, 1990)

Als Robert Slimbach für Adobe Garamond arbeitete, sammelte er zahlreiche Drucke und Dokumente zur Renaissance-Typografie aus europäischen Museen. Und zusammen mit den digitalen Fähigkeiten der 80er Jahre entwickelte er alle brauchbaren Ideen aus den gesammelten Materialien, um Schergen mit einer ausgeprägten Persönlichkeit zu schaffen. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

L’EFFIMERO E L’ETERNO DI FRANCO MARIA RICCI IN MOSTRA ALLA BIBLIOTECA PROVINCIALE "MELLUSI" DI BENEVENTO

La biblioteca provinciale “Antonio Mellusi” al Corso Garibaldi di Benevento ospiterà la mostra “L’effimero e l’eterno. L’essenza della bellezza”, dedicata a uno dei personaggi più eclettici del Novecento: Franco Maria Ricci. La mostra è organizzata e curata da Sannio Europa, società partecipata della Provincia di Benevento che promuove e gestisce la rete museale dell’ente, in collaborazione con la cooperativa San Rocco. Scomparso poco più di un anno fa, Franco Maria Ricci è stato un rinomato designer, un raffinato collezionista d’arte, ma soprattutto un editore illuminato. Nato a Parma, ha concepito volumi meravigliosi, come la ristampa di opere del sapere fondamentali quali l’Encyclopédie di Diderot e D’Alembert o il Manuale tipografico di Giambattista Bodoni, direttore della Stamperia Ducale di Parma a fine ‘700 e creatore di caratteri ricercati ed eleganti, adottati da Ricci per la stampa dei suoi testi. Ha pubblicato collane d’arte e di letteratura uniche, come la “Biblioteca di Babele” nata dall’incontro con Jorge Luis Borges, e la rivista d’arte più bella del mondo: “FMR” che, per la qualità dei contenuti, gli argomenti ricercati e l’eleganza delle immagini e della veste grafica, è un vero oggetto di culto per i collezionisti di tutto il mondo. Pubblicata in cinque edizioni in lingue diverse, e distribuita anche negli Stati Uniti, dopo 163 numeri, il marchio FMR venne ceduto, per assecondare il desiderio di Franco Maria Ricci di dedicarsi alla costruzione del Labirinto della Masone, il più grande in Europa, sede della Fondazione a lui intitolata. Nel dicembre 2020, tuttavia, la casa editrice ne ha riacquisito il marchio e il primo numero della seconda stagione di FMR uscirà nel prossimo mese di dicembre. Nelle collezioni della Biblioteca provinciale di Benevento "Antonio Mellusi", la rivista è presente fin dal “Numero 0", senza dimenticare che nel 2010 l’Istituto ha ricevuto una cospicua donazione di volumi d’arte da parte della stessa casa editrice. In mostra potranno essere ammirati gli esemplari originali dell’ Encyclopédie Des Sciences (1751-1772), manifesto dell’Illuminismo, ancora oggi considerata una delle fonti documentarie più autorevoli sul piano storico per gli argomenti scientifici, artistici e tecnici trattati, accanto a una selezione dei numeri della rivista “FMR” in cui sono approfonditi argomenti di interesse locale, quali l’oreficeria longobarda e la porta bronzea del Duomo di Benevento, esposti accanto ad esemplari antichi che trattano lo stesso tema, testi dedicati al tipografo Giambattista Bodoni, e a una selezione dei volumi d’arte donati da Franco Maria Ricci alla Biblioteca provinciale.

Nell’ambito della mostra bibliografica sarà proiettato il documentario sulla storia di Franco Maria Ricci, dal titolo "Ephèmère – La bellezza inevitabile", realizzato da Simone Marcelli, Barbara Ainis e Fabio Ferri, e gentilmente concesso dalla Fondazione “Franco Maria Ricci”. Nel documentario, i ricordi del protagonista si intrecciano alle parole di alcuni di grandi personaggi intervistati, quali il regista Bernardo Bertolucci, lo storico dell’arte Vittorio Sgarbi, gli editori Feltrinelli, Hoepli e Taschen e il direttore del Musée d’Orsay, Guy Cogeval, che descrivono il protagonista come un ricercatore della bellezza in tutte le sue forme, un visionario, un intellettuale raffinato, ma soprattutto un amico.

0 notes

Photo

By Maggie Bell (co-author)

Italian typographer Giambattista Bodoni was born into a family of printmakers on 16 February 1740 in Saluzzo in the Piedmont region of Italy. He spent his career, also working as a printer and publisher, in Rome and then Parma, where he died in 1813 after serving as director of the Royal Press of the Dukes of Parma (Stamperia Reale). Inspired by the type-designers Pierre-Simon Fournier (1712-68) and John Baskerville (1706-75), Bodoni developed a new style of typeface whereby letters are cut with strong contrasts of thick and thin elements, and favored uniformity and subtlety in the serifs on the upper and lower parts of letters. Like Baskerville before him, Bodoni preferred wide margins and little-to-no decoration or illustration. Bodoni's book of typefaces is still available in print.

Reference: Laura Suffield. “Bodoni, Giambattista.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T009528>.

Various Bodoni publications

Giuseppe Lucatelli, Portrait of Bodoni, c. 1805-6. Museo Glauco Lombardi.

Biagio Martini, Portrait of Bodoni

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrea Appiani - Ritratto di Giambattista Bodoni

Andrea Appiani – Ritratto di Giambattista Bodoni

Ritratto di Giambattista Bodoni

IL DIPINTO

Il ritratto di Giambattista Bodoni, realizzato da Andrea Appiani è un dipinto ad olio su tela (60,3 x 51,2 cm) eseguito nel 1799 e conservato presso la Galleria nazionale di Parma. Il ritratto rappresenta Giambattista Bodoni, celebre incisore, tipografo e stampatore parmense. Con pennellata fluida e sintetica l’intellettuale è inquadrato a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

neo-classical luncheon

heads set in digital reissue of kuenstler script black. the base weight, originally called künstlerschreibschrift, was modeled upon the scripts of 18th c. writing masters, & issued by d stempel ag in 1902; the black cut, the design of hans bohm, issued in 1957.

items set in digital reissue of bauer bodoni. bauer’sche giesserei issued their bodoni types in 1927, cut from designs of heinrich jost, in which he abstracted singular roman & italic from the numerous founts engraved by giambattista bodoni in parma, 1768‒1813.

fleuron pair are digital reissue of monotype recuttings [uk monotype 357-8]: bodoni did cut these fleurons, 303-4 in his Fregi e Majuscole [parma, 1771, p22], but abstracted them—as did he much of his ornamental material—from pierre-simon fournier [vignettes 108-9 in: Manuel Typographique, tome ii, imprimé par l`auteur, se vend chez barbou, paris, 1766, p100], who, in turn, had copied the design of louis luce [Épreuve du premier alphabeth droit et penché, ornée de quadres et de cartouches., imprimerie royal, paris, 1740].

1 note

·

View note

Photo

So I’ve decided I’m going to use the Bodoni type face for my specimen poster. I like the traditional style and I feel I can create a poster that really reflects the elegance of the type.

Giambattista Bodoni was an Italian printer born in 1740. He started his career working in Rome for the pope, printing out various Biblical documents before finally being granted his own printing press by the Duke of Parma, where he printed classical Greek and Roman literature.

0 notes