#Georgian Britain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Windsor Castle from Datchet Lane on a rejoicing night, 1768

by Paul Sandby

#windsor castle#art#paul sandby#windsor#datchet lane#england#english#bonfire#night#full moon#river bank#fireworks#river thames#middle ward#winchester tower#star buildings#georgian era#georgian#great britain#history#celebration#king#george iii#torch#tricorn hat#drunken#drunk#castle#british#torchbearer

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surrounded by lush gardens, The Ivy in Chippenham is well named.

#The Ivy#Chippenham#Wiltshire#The Cotswolds#1728#Georgian architecture#neoclassical#English mansions#UK#18th century#baroque aesthetic#country estate#rural britain

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hermitage, Craigvinean Forest, Perthshire, Scotland

(happiness_behind the_lens)

#gothic#gothic architecture#georgian#neo classical#neoclassical#craigvinean forest#fall#autumn#dunkeld#perthshire#scotland#britain#great britain

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Silk Robe à l’anglaise Dress, ca. 1770, British.

Met Museum.

#red#silk#brocade#18th century#1770#1770s#british#Britain#met museum#robe à l’anglaise#extant garments#Georgian#1770s britain#fave#1770s dress#1770s womenswear#1770s extant garment

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

MILK SOUP, THE DUTCH WAY (1747)

It has been a few weeks since I made a historical dish due to a busy schedule and a weekend trip tp London (where I picked up an interesting historical cookbook, 'Churchill's Cookbook', which I intend to use here if I run out of Tasting History recipes). To keep in the English mood, I decided to make my next Tasting History dish, Milk Soup, the Dutch Way. While it may have been inspired by the Dutch style of making Milk Soup at the time, it is, in fact, an 18th century English recipe from Hannah Glasse's 'The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy', published in 1747. This soup technically follows the rules of Dr. George Cheyne’s Georgian English fad diet of “Milk, Seeds, Bread, mealy Roots, and Fruit”. While it follows Dr. Cheyne’s rules, this soup less a healthy soup and more a dessert. I chose to make this recipe entirely because Max says it tastes exactly like the milk left over from Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereal - a nostalgic breakfast treat from my childhood. Milk soup may sound a little strange, but it will hopefully be delicious. See Max’s video on how to make it here or see the ingredients and process at the end of this post, sourced from his website.

My experience making it:

I stuck fairly close to the recipe, other than the fact that I halved it. The only minor change I made is that instead of using whole milk, I used 1.5% milk, mainly because I bought the wrong one, mindlessly purchasing our default milk. For the sippets, I used French baguette, and for the butter, I used Kerrygold unsalted.

Milk Soup was a pretty quick dish to make, but did make a few dishes to clean. While the oven preheated, I fried the baguette slices in butter. I threw them in the oven, but they definitely took less than 30 minutes to dry out. As a result, mine were a little on the crispier side than Max's were. I heated the milk and attempted to dissolve the cinnamon and brown sugar into it with some constant stirring, but the cinnamon, like Max warned, did not quite want to combine all that well. It eventually did, but just a little. I added in two sippets, leaving the others on the side so I could try dipping them and 'croutoning' some of them into the soup when trying. I beat the egg yolk, then added half of the milk mixture to it, then poured it all back in the pot. It was super frothy at this point, so I simmered it a bit longer until the bubbles went down. I served up two portions, with a few sippets on the side, and was quite happy it looked similar to Max's Milk Soup!

My experience tasting it:

I first tried the soup by itself. To my delight, it did taste exactly like the milk left over from Cinnamon Toast Crunch! Then I tried a spoonful with some of the soup-soaked sippet: it was cinnamony, sweet, and a little buttery. A little soggy, but not terribly - similar to the last few bites of cereal before there is only milk left. Next, I dipped a crispy sippet into the soup and took a bite: this time, the sippet was almost too dry and crispy, it barely soaked up any of the soup flavour. Lastly, I broke up a sippet into crouton shapes and threw them into the Milk Soup. Taking a spoonful with these fresh, crispy bites of buttery toast was the winner for sure - probably the most literal interpretation of Cinnamon Toast Crunch. It blew my mind to think that this exact flavour and texture combination was a thing in the 18th century, long before Cinnamon Toast Crunch graced our kitchen cupboards! My husband and I both enjoyed the Milk Soup, but I would probably simplify the recipe if I was going to make it again. I think you would get the same flavour if you didn't add the beaten egg yolk. I also think that kids would really enjoy this recipe; it's a little interactive, sweet, and very close to modern flavours in desserts. If you end up making this dish, if you liked it, or if you changed anything from the original recipe, do let me know!

Milk Soup (The Dutch Way) original recipe (1747)

Sourced from The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, 1747.

Boil a quart of milk with cinnamon and moist sugar; put sippets in the dish, pour the milk over it, and set it over a charcoal fire to simmer, till the bread is soft. Take the yolks of two eggs, beat them up, and mix it with a little of the milk, and throw it in; mix it all together, and send it up to table.

Modern Recipe

Based on The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, c. 1747, and Max Miller’s version in his Tasting History video.

Ingredients:

Sippets

4 tablespoons butter

8-12 small pieces of bread, I used a baguette sliced 1/2” thick

Soup

1 quart, plus 3/4 cup (1.1 L) whole milk

1 1/2 teaspoons cinnamon

1/3 cup (70 g) light brown sugar

2 egg yolks, beaten

Method:

For the sippets: Preheat the oven to 225°F (105°C) and line a baking sheet with parchment paper.

Melt the butter in a pan over medium heat, then add the bread slices. Cook for 1 minute on each side, or until nicely browned.

Place the bread on the baking sheet and bake for 30 minutes or until they are dry and crisp.

For the soup: When the sippets are almost done, pour the milk into a pot and whisk in the cinnamon and brown sugar.

Bring to a simmer over medium heat, then add the sippets. Simmer, stirring occasionally to make sure the milk doesn’t burn, until the sippets are soft.

Add about 1/2 cup of the hot milk mixture to the egg yolks, whisking constantly, then add it all back to the pot and stir for 10 to 15 seconds. Remove from the heat and serve it forth.

#max miller#tasting history#tasting history with max miller#cooking#keepers#europe#18th century#The art of cookery made plain and easy#Hannah Glasse#england#great britain#comfort food#Cinnamon#Milk Soup#desserts#breakfast#soups#historical cooking#bread#Georgian recipes#vegetarian recipes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Badly cropped FFAS Commonwealth government development notes...

#yes it's very obviously stuart britain but I am trying to get some more georgian ireland in there. for instance look at the undertaker#wip: ffas

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical silverware expert on antiques roadshow just said he'd never thought about the connection between Georgian era sugar bowls and slavery....

#isnt his job to know about the historical context of items??#never once considered how georgian britain got all that sugar???#jesus fucking christ dude#narn.txt

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somerset House On A Rainy Day, London, England, United Kingdom, 2019

#photography#photo#original photography on tumblr#original photographers#city photography#somerset house#london#georgian era#palace#18th century#britain#United Kingdom#canon#19th century#victorian era#construction time stretched across bothtime periods#architecture#fountain

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shropshire

Ironbridge, UK (by Beth Chobanova)

#Ironbridge#Shropshire#River Severn#The Gorge#1779#UK#English villages#Georgian architecture#18th century#historic#Thomas Telford#engineering feat#Industrial Revolution#Great Britain

557 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Circle

The Rotunda Museum in Scarborough, England. built in 1828 and is Grade II Listed.

#scarborough#architecture#architecture design#architecture photography#building#classical#classical architecture#decorative#detail#georgian#georgian era#georgian architecture#grade II#grade 2#heritage#history#listed#museum#old#seaside#stone#stone masonry#urban#north yorkshire#britain#england#uk

0 notes

Text

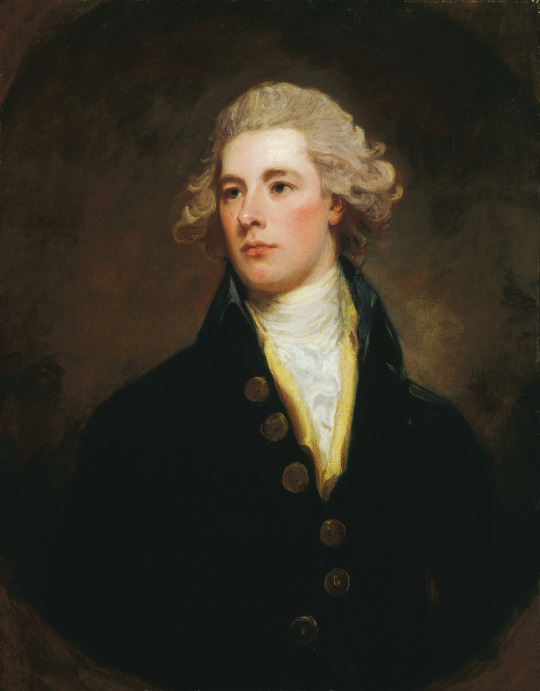

William Pitt the Younger by George Romney

#william pitt#william pitt the younger#art#portrait#george romney#england#great britain#prime minister#english#british#history#europe#french revolutionary wars#napoleonic wars#french revolution#georgian era#georgian

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wentworth Woodhouse: Britain's largest home has over 300 rooms

#Wentworth Woodhouse#Rotherham#South Yorkshire#UK#Baroque aesthetic#Palladian architecture#English mansions#country estate#rural britain#Georgian era#1740's

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highgrove-Gloucestershire

Highgrove House

#Highgrove House#Tetbury#Gloucestershire#Cotswolds#UK#English countryside#country estate#formal garden#sanctuary#retreat#monarchy#rural britain#Georgian era#Prince Charles#Georgian architecture

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georgian Judge Lord Ellenborough and his struggle against pornography.

Available 2025 First, a disclaimer. Pornography was not a word that was used in the Georgian era; the first reference in any Victorian newspaper seems to be the Hereford Times of 1858, when it is used in its absolute literal sense of writings about prostitutes in Roman Pompeii. It gathered its modern meaning in the 1880s, but even then no home-grown responsibility was taken for it; it was…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Yellow Robe à la Française, ca. 1760, British.

Met Museum.

#met museum#silk#cotton#linen#yellow#18th century#1760#1760s#1760s britain#womenswear#extant garments#dress#britain#british#robe a la francaise#georgian#fave#1760s dress

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baby You're First-Rate

Rated Navy ships in the 17th to 19th centuries [from the Royal Museums Greenwich]

The rating system of the British Royal Navy was used to categorise warships between the 17th and 19th centuries. There were six rates of warship.

A ship’s rate was basically decided by the number of guns she carried, from the largest 120-gun First Rate, down to the Sixth Rate 20-gun ships. Captains commanded rated ships, which were always ship rigged – meaning they had three square-rigged masts.

First Rate

First Rate ships were the biggest of the fleet with their gun batteries carried on three decks. They were generally used as flagships and fought in the centre of the line-of-battle. They were armed with a minimum of 100 heavy cannon, carried a crew of about 850 and were over 2000 tons Builder’s Measure (a formula for calculating the capacity of the ship, not the displacement of the ship as is the practice today).

Second Rate

The Second Rate ships of the line were also three-deckers, but smaller and cheaper. They mounted between 90 and 98 guns, and like the First Rates fought in the centre of the line-of-battle. Generally around the 2000 ton mark, they had a crew of about 750. Unlike the First Rates, which were too valuable to risk in distant stations, the Second Rates often served overseas as flagships. They had a reputation for poor handling and slow sailing.

Third Rate

The most numerous line-of-battle ships were the two-decker Third Rates with 64–80 guns. The most effective and numerous of these was the 74-gun ship, in many ways the ideal compromise of economy, fighting power and sailing performance, which formed the core of the battle fleet. They carried a crew of about 650 men.

Fourth Rate

Two decker ships of 50–60 guns were no longer ‘fit to stand in the line of battle’ by the end of the 18th century. With two decks, their extra accommodation made them suitable flagships for minor overseas stations, while their relatively shallow draught made them useful as headquarter ships for anti-invasion operations in the North Sea and the English Channel. They were also useful as convoy escorts, troopships and even on occasion, as convict transports. In normal service they had a crew of 350 and measured around 1000 tons.

Fifth Rate

These were the frigates, the Navy’s ‘glamour ships’. With their main armament on a single gundeck, they were the fast scouts of the battle fleet, when not operating in an independent cruising role, searching out enemy merchant ships, privateers or enemy fleets. Developed from early-18th century prototypes, the Fifth Rates of Admiral Lord Nelson’s time had a variety of armaments and gun arrangements, from 32–40 guns. Captured enemy frigates were also used in service, and many of the best British-built ships were copied or adapted from French designs. Their tonnage ranged from 700 to 1450 tons, with crews of about 300 men.

Sixth Rate

The Sixth Rates were smaller and more lightly armed frigates, with between 22 and 28 guns, a crew of about 150, and measured 450 to 550 tons.

Find out about ‘unrated’ Royal Navy vessels in the 17th to 19th centuries

#royal navy#history#nautical#age of sail#ships#ships of the line#navy#frigates#warships#georgian#18th century#19th century#admiral nelson#reference#royal museums greenwich#maritime#britain#british history

1 note

·

View note