#George Hankers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

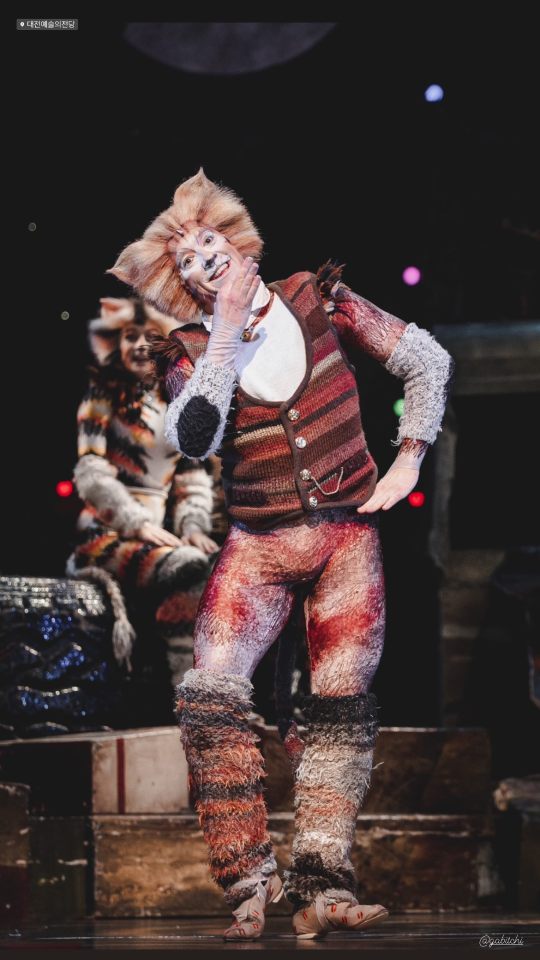

I think it's very important that you all see this clip of M&R being cute with... well, M&R.

Did you know that Tugger can do punchies and, more importantly, Munkustrap can, when called upon by the presence of cute orange little guys, do silly kickees? and also scrabble at bellies?

Oasis cast 1, 2014. Since this is Oasis, and all characters are present for this performance, they are almost certainly all first cast (barring the chance of temporary replacements), and I definitely recognise George Hankers as Mungojerrie. The other three should be Georgie Leatherland (Rumpelteazer), Matias Stegmann (Munkustrap), and Dominic Andersen (a very enthusiastic Tugger who must leap and frolic everywhere).

#oasis#oasis 1#munkustrapxrumpelteazer#mungojerriexmunkustrap#mungojerriextugger#rumpelteazerxtugger#s: bows#george hankers#georgie leatherland#matias stegmann#dominic andersen#c: rum tum tugger#c: munkustrap#c: mungojerrie#c: rumpelteazer#mungojerriexrumpelteazer

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last Wednesday show of Asia Tour 2022-2023 as the cast begins to wrap up everything in Taipei, Taiwan. After today (09 August 2023), there are only six shows left!

George Hankers covered Mungojerrie today, and Katie Hutton give him the praise he deserves as a temporary partner to her Rumpleteazer, and his overall role in the company.

A group of Toms gathered for a picture.

With Russell Dickson as Munkustrap, Nathan Zach Johnson as George, Oliver Ramsdale as Admetus, Saverio Pescucci as Alonzo, Matthew Levick as Bill Bailey, Cian Hughes as Carbucketty, and Johnny Randall as Mistoffelees.

Cian got in four pictures of his Carbucketty, and found Lucy Rice covering Bombalurina in one.

Saverio Pescucci was ready for a great show day.

Matthew Levick as Bill Bailey brushes his troubles away.

#CATS Musical#CATS the Musical#CATS Asia Tour 2022-2023#CATS Taiwan Tour 2023#Rumpleteazer#Katie Hutton#Mungojerrie#George Hankers#Carbucketty#Cian Hughes#Alonzo#Saverio Pescucci#Bombalurina#Lucy Rice#Bill Bailey#Matthew Levick#Mistoffelees#Johnny Randall#Munkustrap#Russell Dickson#Admetus#Oliver Ramsdale#George#Nathan Zach Johnson

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

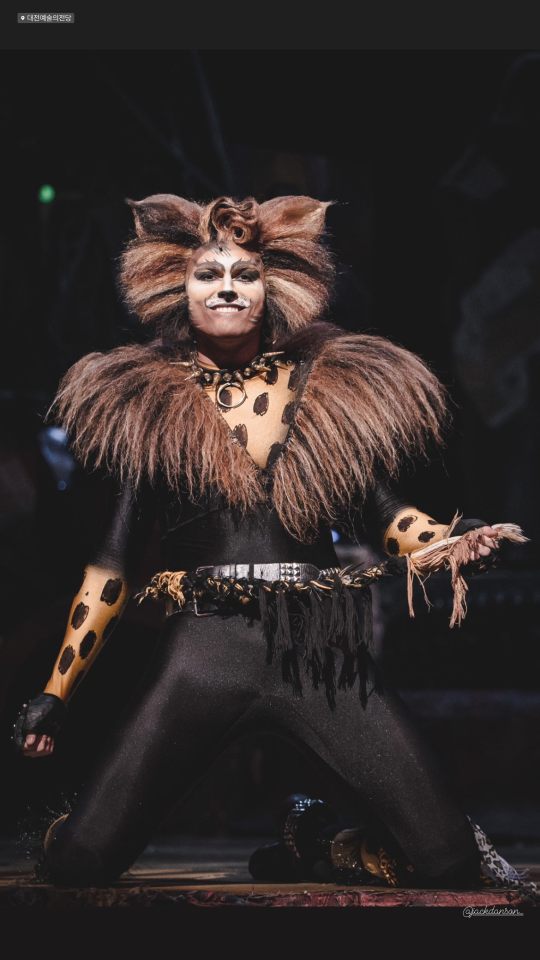

this user's instagram stories: May 21, 2023

#cats korea tour 2022#stage cats#bradley delarosbel#alonzo (cats)#madison green#jennyanydots#matt krzan#munkustrap#jack danson#the rum tum tugger#rum tum tugger#george hankers#carbucketty#pouncival#gavin eden#skimbleshanks#isabella roberts#victoria (cats)#victoria the white cat#see the queue on a sunflower

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

CATS OASIS 1ST CASTS BOOT HAS DROPEED

youtube

Cast acoording to the description: Alonzo / Rumpus Cat - Jack Butterworth Asparagus / Bustopher Jones / Growltiger - Greg Castiglioni Bombalurina - Rachael Ward Cassandra - Georgia Reid Hamilton Coricopat - James Titchener Demeter - Kelsie-Rae Marshall Grizabella - Vivienne Carlyle Jellylorum / Griddlebone - Celia Graham Jennyanydots - Erica Leigh Hansen Mistoffelees - Anthony Starr Mungojerrie - George Hankers Munkustrap - Matias Stegmann Old Deuteronomy - Trent Armand Kendall Plato / Macavity - Calvin Cooper Pouncival - Enric Marimon Rumpelteazer - Georgie Leatherland Rum Tum Tugger - Dominic Andersen Sillabub/Jemima - Tarryn Gee Skimbleshanks - Lee Greenaway Tantomile - Lydia Bannister Tumblebrutus - Aaron Hunt Victoria - Sophia McAvoy

#cats the musical#cats musical#jellicle cats#cats oasis of the seas#cats oasis#Cats rccl#im really happy to see this like considering nowadays we have the curent cast boots#and was hoping from the past few days we get the pre 2019 boot like the whole shebang#AND NOW ITS HEREEE#Youtube

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

At first glance, the first stretch of New Jersey Route 4 — which begins just off the George Washington Bridge coming from Manhattan — looks like any other highway in the tri-state area. As one might expect on a busy road through Englewood, New Jersey, there’s a concentration of gas stations, motels and parking lots.

But there’s one business on this busy highway that offers something that other commuting and road tripping pit stops simply do not: Hot, kosher cholent, the slow-cooked traditional Ashkenazi stew.

Welcome to Snaxit — yes, its name is a portmanteau of the words “snack” and “exit” — a gas station convenience store that in many respects looks like all others. But upon closer inspection, visitors might notice a steady stream of Hasidic customers and a sign that says “24/6,” meaning the business is open 24 hours a day, six days a week and is closed on Shabbat. Located directly off Route 4, Snaxit is a fully kosher convenience store that’s an ideal pit stop for observant Jewish drivers — or anyone with a hankering for Ashkenazi cuisine.

For the driver looking for a quick munch, Snaxit’s shelves are lined with packaged kosher food like Doritos (written in Hebrew script) and dried fruit. For the driver in need of a pick-me-up, kosher energy drinks called Koyach sit atop the counter. And for the driver who wants a hot, hearty and decidedly Jewish meal? They can head to the convenience store-style case and grab a cholent, kugel or perhaps a knish if they’re in the mood.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It is terrifying to think how little I learned at Oxford. I suppose because I never wanted to go there – my heart was in travel. I was no longer hankering for the Navy, but had this desire for travel. My next brother, now King George VI, was in the Navy and by that time he had gone to sea and was making trips around the world. That irritated me very much because I wanted to be traveling too. I couldn’t think why he should be so lucky to do these things and not me.”

- The Duke of Windsor, reflecting on his time at Oxford.

- from Once a King: the Lost Memoir of Edward VIII, by Jane Marguerite Tippett

#how about a little cheese with that whine?#king george vi#king edward viii#duke of windsor#Royal brothers#british royal family

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Citizen: My Life After the White House by Bill Clinton

In this account of his years after leaving office, Clinton is a hyperactive and loquacious presence, helping out in disaster zones and pontificating about public service – but he reveals little about his private life

American presidents are supposed to renounce pomp and disappear into private life when their term ends. George Washington enjoyed sampling the whiskey produced by the distillery at his Virginia plantation, while George W Bush currently amuses himself by clearing underbrush on his Texas ranch. Bill Clinton, aged only 54 when he left office in 2001, spurned bucolic oblivion; as he says with scriptural solemnity: “I didn’t think my work here on Earth was finished just yet.” Although he calls his memoir Citizen to signal his reduced status, he admits to hankering after his years as a conqueror, with military bands that struck up Hail to the Chief as his personal anthem whenever he strode into a room.

Because the presidency has grown ever more undemocratically monarchical, Clinton toyed with a possible succession. His wife’s candidacy in 2016 offered him the prospect of returning to the White House as her First Gentleman, and his daughter, Chelsea, might have exotically extended the family line: in 2002 Muammar Gadaffi suggested marrying her to his son and thereby “launching a dynasty”. But Hillary lost to Trump, Chelsea nixed the proposal, and instead Clinton has incorporated himself. He set up the Clinton Foundation, kept it flush with his lecture fees and soon presided over an empire of eponymous acronyms - the CCI (Clinton Climate Initiative), the CDI (Clinton Development Initiative), the CGI (Clinton Global Initiative), the CHAI (Clinton Health Access Initiative), and so on to the end of the alphabet.

He is frank about his initial motive for keeping busy. “I had to start making money,” he admits, mostly to pay the legal bills accrued during the Republican attempt to impeach him over his entanglement with Monica Lewinsky. Yet for this hyperactive man, being busy is its own reward. In the first section of his book he hurls himself into disaster zones like an ambulance-chasing attorney, usually taking celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey or Sean Penn along for the adrenalised ride. “I volunteered to help,” he says after hearing about an earthquake in Gujurat. With the Asian tsunami he teasingly stands on ceremony: “My staff called the White House to say I wanted to help.”

On the ground he is generous with his presence, reporting that at an Indian hospital he “visited with the patients and families who wanted to say hello”. In a Rwandan village he and Chelsea helpfully mime the filtration process of murky water that would benefit “countless millions of poor people”. A Puerto Rican hurricane supplies “the most fun” when Lin-Manuel Miranda lays on a performance of Hamilton; George Clooney, despatched by Nespresso to encourage ruined coffee planters, joins the party. After a consoling sortie to the battered Maldives, Clinton resumes a triumphal junket “to China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan to promote my autobiography”. Other countries expecting seismic upsets are tipped off about his likely availability: “I’ll show up if I can.”

Having shown up, Clinton can be counted on to speechify. Although he believes that “the world doesn’t need another talkfest”, he is unstoppably loquacious. With Kim Jong-il he picks over “the usual stilted talking points” and in Bosnia he delivers terse “remarks”. In Accra, however, boosted by loudspeakers at a rally in an open square, he holds forth to a million auditors, “the largest crowd I’ve ever addressed”. He mistakenly assumes that George HW Bush is equally gabby and obliges him “to talk too long to too many people” on one of their humanitarian tours; George W Bush, raising funds for yet another hurricane, astutely warns Clinton to be “short and sweet”. Only once is he both out-talked and unmanned. As a student at Oxford, invited to tea at a women’s college, he likens himself to the ball boy at a testicular tennis match, exhausted by “the verbal serves and volleys that flew across the net”.

Garrulous he may be, but Clinton is convivial without being confidential. On a mission to extricate two journalists held hostage in North Korea, he remembers to be diplomatically expressionless in the official photograph and even rehearses not smiling. This long book about himself has the same ultimately dreary impersonality. “We all experience good times and grief,” he says, shuttering his private life. He bridles when accused by an interviewer of not apologising personally to Monica Lewinsky: didn’t he express generalised regrets in a public forum during a meeting with “faith leaders” at the White House? It was not, he says, “my finest hour”, referring to the tetchy interview, not to his exploitation of an infatuated intern.

Autobiographical anecdotes are twisted into what Clinton calls “teachable moments”, as when his reminiscence of an outdoor toilet in his Arkansas boyhood, “attractive to snakes in the summer”, introduces a homily about “productive grassroots partnerships with business”. The snakes must have been real enough but the grass they slither in is merely metaphorical. A single specimen of candid unpolitical speech is brattishly uttered by the three-year-old Chelsea when introduced to George HW Bush at his home in Maine. “Where’s the bathroom?” she asks her host.

No wonder that Clinton, always on guard against intimate leakages, so enjoyed collaborating with James Patterson on two thrillers published in 2018 and 2021, in which successive US presidents shed their inhibitions and enjoy careers as action heroes: the first anonymously slips out of the White House to thwart a cyberterrorist, the second ventures to Libya to rescue his kidnapped daughter. Clinton warns that climate change will eject us into “a real-life sequel to the post-apocalyptic Road Warrior movies”, but that swashbuckling apparently appeals to him. Politics, by contrast, seems as deadly dull as the language he uses to describe it. America, he says, has gone “off the rails”, although responsible commentators try “to keep the train on the tracks”: is he angling for honorary membership of Aslef?

Handed a microphone, Clinton is eager to share “an overview of how I view the world”, although these omniscient surveys mostly consist of faded neoliberal truisms. At the end of his book, this overview of the world is replaced by an underview of the universe as he scrutinises “the far reaches of outer space” at a scientific observatory in Hawaii. The interstellar void seen through the telescope makes him ask, with a shudder that the banal phrasing fails to muffle: “What does it all mean in the grand scheme of things?” His foundation, its funds and its global good works suddenly shrivel, and Clinton rebukes those who pursue “worldly political power” with a misplaced messianic zeal.

Then a few lines later he resumes pontificating about public service, and after a possible glimpse of a “creator God” out there in the darkness, he concludes by insisting “I’m happy.” This was written before the recent election; I’ll bet he no longer feels quite so cosmically complacent.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Dorado (1966)

Pulp science fiction writer Leigh Brackett was an anomaly in the genre. Not only was she a woman, but she also crossed over into Hollywood sporadically. Alongside her novellas and serialized stories, her film credits are enviable: The Big Sleep (1946; okay, this film’s story never made sense, but its romantic dialogue is legendary), Rio Bravo (1959), and, posthumously, The Empire Strikes Back (1980). To Brackett, she deemed her script to 1966’s El Dorado, a loose adaptation of Harry Brown’s novel The Stars in Their Courses, as “the best script [she] had done in [her] life.” High praise for oneself, especially as one could easily interpret El Dorado as a lighter, slightly more comic version of Rio Bravo. El Dorado was Brackett’s fourth of five collaborations with director Howard Hawks (1938’s Bringing Up Baby; the four other Brackett-Hawks collaborations include The Big Sleep, 1948’s Red River, Rio Bravo, and 1970’s Rio Lobo). Brackett’s inventiveness and spiky dialogue makes even the more clichéd elements of the story more entertaining than they should be. Other than Hawks and the ensemble cast, it is Brackett who is most responsible for the film’s success.

Somewhere in the American West, cowboy Cole Thornton (John Wayne) rides into the town of El Dorado for a job offer from local landowner Bart Jason (Ed Asner). His longtime friend, Sheriff J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum) meets with him, quickly deduces the reason for Cole’s presence in town, and effortlessly persuades his friend to turn down the job (the mutual respect for each other – between the characters and between Mitchum and Wayne – is apparent from the moment they meet). Jason’s job for to Thornton included coercing, gently or otherwise, the MacDonald family to abandon their land and water rights. The MacDonalds are an honest family, Harrah says, and they have been the target of regular harassment from Bart Jason and his men. Over the rest of the film, Harrah, Thornton, elderly deputy Bull Harris (Arthur Hunnicutt), a youthful gunslinger named Mississippi (James Caan), and Dr. Miller (Paul Fix) find themselves further embroiled in Jason’s repeated attempts to violently force the MacDonalds out.

El Dorado’s large supporting cast also includes saloon owner Maudie (Charlene Holt, whose character has a hankering for Thornton); R.G. Armstrong, Christopher George, Johnny Crawford, and Adam Roarke as the MacDonald boys; and Michele Carey as the hot-tempered Josephine “Joey” MacDonald (Carey and Holt play two of the final examples of the “Hawksian woman”).

Comparisons to Rio Bravo are all but inevitable to cinephiles and fans of American Westerns. Where Rio Bravo is more of a movie where friends revel in each other’s’ vibes, El Dorado is squarely a story of aging cowboys whose foibles – Harrah’s alcoholism to drown his self-pity, Thornton’s first act spinal injury and free-roaming ways – may spell the difference between local tragedy and justice. Despite what she might say, Brackett’s script to Rio Bravo (co-written by Jules Furthman) is far tighter than El Dorado’s, which employs a momentum-killing six-month time skip just as its dramatic interest begins to pique (editor John Woodcock does not provide any assistance here). It takes just a tad too much time for El Dorado, which uses the time skip to introduce Mississippi and sideline Harrah due to his heavy drinking, to regain the dramatic interest it established in the opening third of the movie.

Both casts of Rio Bravo and El Dorado have advantages over the other. Rio Bravo boasts Walter Brennan and Ward Bond in supporting roles (yet I’ve never been too fond of Dean Martin’s performance). El Dorado has Mitchum (whose dynamic with Wayne is fantastic), Caan (miles better than a Ricky Nelson sticking out like a rock 'n' roll kid from the 1950s), and not enough Asner. The two films, to me, are similar in quality, and I vacillate between which is “better” (but, on a rewatch, I think I might prefer El Dorado)*.

The interplay between John Wayne and Robert Mitchum lies at the heart of El Dorado. In 2024, it remains fashionable to lambaste Wayne for not being able to act and “playing himself” – an accusation that has been around for decades. With more lightly comedic material than usual (I would not consider El Dorado a comedy, but there are good-hearted ribbings and wry situational observances that prevent this from being a pure dramatic Western), Wayne revives some of the comic timing from The Quiet Man (1952) to decent effect here, especially around Mitchum and Caan. But most compellingly, Howard Hawks directs Wayne in a way that acknowledges and plays against his on-screen persona as the accomplished Western hero. Thornton’s spinal injury in the film’s opening act sees him reckon with his mortality – in jest and in seriousness. Wayne’s delivery and his physical acting is striking to longtime viewers such as yours truly, as it is one of the first films in which Wayne must come to terms with aging and his growing fallibility, as well as his reputation for outgunning and outthinking his opponents. The seeds of what would be Wayne’s late career signature performances in The Cowboys (1972) and The Shootist (1976) begin to show themselves here.

Mitchum, perpetually sleepy-eyed and always my first choice to play a slovenly protagonist good with a revolver, is wonderful here as a sheriff with the romantic maturity of a teenager who unaccustomed to rejection. The duality of Mitchum’s Sheriff Harrah here – the fastest gun for miles around determined to uphold the law and the inebriated slob who retains a sense of humor that makes self-pitying and self-deprecation indistinguishable – is difficult to pull off, but Mitchum does exactly that. Mitchum and Wayne’s historical on-screen personas are not polar opposites, but there is nevertheless little overlap between the two aside for their marksmanship. In their only screen appearance together (the two both co-starred on 1962’s The Longest Day, but their scenes were filmed separately), it seems the two have known each other for ages. The subtle glances, the knowing facial expressions, and gentlemanly warmth in conversation bely the fact that this is their first film together. But for El Dorado, their rapport benefits the film magnificently.

Like his good friend Ernest Hemingway, Howard Hawks admired masculine competence, professionalism, and self-reliance. El Dorado rambles a little bit about duty, honor, and loyalty, but all of this surrounds the central tenants of male friendship found here and in Rio Bravo. It is the development of that friendship and simultaneous professional excellence, rather than any plot details, that concerns Hawks – and this is the frame through which he wants viewers to see this film. By his own self admission, Hawks stated that he was, “much more interested in the story of a friendship between two men” than anything else in El Dorado (including fidelity to the original novel). The range war between Jason and the MacDonald family lacks as much exposition as some might expect. Hawks and Brackett refuse to fully explain how the dispute started, as well as what the conflict has wrought during the film’s time skip.

Those who are not as competent or professional – in this film’s case, James Caan’s character of Mississippi – are simply comic relief until they can prove otherwise. For those aware of Hawks’ aversion to Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) – in which Gary Cooper’s Sheriff Will Kane spends almost ninety minutes going around town asking for help when he learns a few recently-released convicts are coming to murder him (Hawks, to my consternation, considered this cowardly and a disgrace to the Western genre) – El Dorado is yet another reaction against it.

Unlike Hemingway, Hawks (who was by no means a feminist) rejects Hemingway’s reductionist portrayals of women as “Dark” (submissive lovers) or “Light” (castrating man-killers). The female protagonists in Hawks’ films, too, demonstrate tremendous ability. The saloon keeper, Maudie, is perhaps the most keenly observant individual in the entire picture, and can pick out the psychology of a person whether she has known them for ages (such as our leads) or if they have just stumbled in for a drink. She may be the smartest person in town. Her fellow Hawksian Woman is the wild-haired Joey MacDonald (her hair feels at times like an anachronism airlifted from the 1960s, rather than a likelihood of the Old West), quick on a gun and with a quicker temper. There is not nearly enough attention on either character as previous Hawksian Women (nevertheless, we need to recall what Hawks wanted to concentrate on most here, and that’s male friendship), but what there is still improves El Dorado’s watchability aside from our two leads.

youtube

A worthy score from composer Nelson Riddle (1960’s Ocean’s 11, 1962’s Lolita) dials back the main theme more than one might expect from a midcentury Western, but it is still effective music for this film. Riddle is best known as an arranger and orchestrator for the likes of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and Linda Ronstadt, not a composer. Nevertheless, arrangers and orchestrators can learn composition through osmosis if they have not already been trained in music composition. Riddle’s liberal use of harmonica perfectly captures the setting, although his use of electric guitar/bass and discernible lack of harmonic identity (especially in the strings) feels too much like television scoring from this era – Riddle was the principal composer for the 1960s Batman television series starring Adam West. Instead, the score highlights revolve around uses of the main title song and its variations.

And what about that title song? Sung by George Alexander and the Mellomen, with lyrics by John Gabriel (Dr. Seneca Beaulac on ABC’s soap opera Ryan’s Hope), “El Dorado” fits the film perfectly, and Alexander’s rich baritone musically exemplifies the masculine themes of El Dorado. Strings double underneath the vocals, with the occasional woodwind and brass section and peaking out from the melodic doubling (again, one wishes for more harmonic interest here aside from doubling the melody). A snippet of the song’s lyrics reference to Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “Eldorado”; the poem itself is recited by Mississippi. “El Dorado” is nothing but an earworm, and I just wish it (and its variations) made more appearances in the film itself.

Though Rio Bravo had elements of a changing of the guard, El Dorado cannot help but feel, by its conclusion, as a generational marker, a near-last hurrah – intentionally or otherwise. This is not, like The Wild Bunch (1969) or Unforgiven (1992), a eulogy of the Old American West. In 1966, El Dorado came at a time when the great figures of Old Hollywood and the height of the American Western’s popularity (Wayne and Mitchum) were no longer the dominant forces in American cinema. The film’s title song even opens with oil paintings from Western artist Olaf Weighorst, of evocatively overcast vistas of the West, as if in reflection.

El Dorado would be Leigh Brackett and Howard Hawks’ penultimate collaboration and penultimate Western, with Rio Lobo a few years away. Their professional partnership, so unlikely given Hawks’ status in Hollywood and Brackett’s supposedly disreputable day job as a pulp science fiction writer, is maybe one of the most underrated and undermentioned in Old Hollywood history – one that spanned the height of Golden Age Hollywood to its final years. For El Dorado, Brackett, despite a few structural missteps, once again shows her gifts for dialogue and a keen understanding of Hawks’ directorial intentions. Hawks arguably improves upon his depiction of male camaraderie from Rio Bravo, allowing our protagonists to intuit their aging (some might say obsolescence). This is a sterling Western, if slightly out of time.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* As of this write-up’s publication, I have not seen Rio Lobo (1970), which forms an unofficial trilogy of Westerns with Rio Bravo and El Dorado.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#El Dorado#Howard Hawks#John Wayne#Robert Mitchum#James Caan#Charlene Holt#Paul Fix#Arthur Hunnicutt#Michele Carey#Leigh Brackett#Ed Asner#R.G. Armstrong#Harold Rosson#John Woodcock#Nelson Riddle#Harry Brown#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

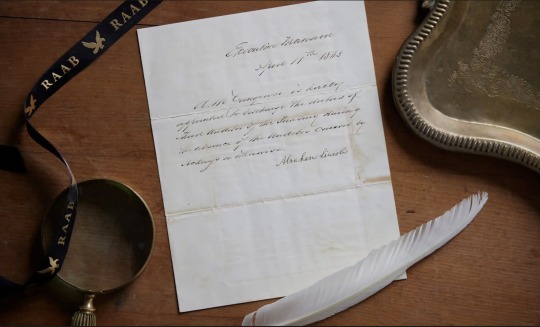

An original document signed by President Abraham Lincoln four days before his assassination on 15 April 1865. Photograph: Raab Collection

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

February 18, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

On the third Monday in February, the U.S. celebrates Presidents Day, a somewhat vague holiday placed in 1968 near the date of George Washington’s birthday on February 22, 1732, but also traditionally including Abraham Lincoln, who was born on February 12, 1809. This year, that holiday falls on February 19.

That the American people in the twenty-first century celebrate Abraham Lincoln as a great president would likely have surprised Lincoln in summer 1864, when every sign suggested he would not be reelected and would go down in history as the man who had permitted a rebellion to dismember the United States.

The news from the battlefields in 1864 was grim. In May, General U. S. Grant had taken control of the Army of the Potomac and had launched a war of attrition to destroy the Confederacy. In May and June, more than 17,500 Union soldiers were killed or wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness, 18,000 at Spotsylvania, and another 12,500 at Cold Harbor. As the casualties mounted, so did criticism of Lincoln.

Those Republican leaders who thought Lincoln was far too conservative both in his prosecution of the war and in his moves toward abolishing enslavement had plotted with the humorless Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, who perennially hankered to run the country, to replace Lincoln with Chase on the 1864 ticket.

In February they went so far as to circulate a document signed by Senator Samuel Pomeroy of Kansas, a key party leader, saying that “even were the re-election of Lincoln desirable, it is practically impossible against the union of influences which will oppose him.” Even if he could manage to pull off a reelection, the Pomeroy circular said, he was unfit for office: “his manifest tendency towards compromises and temporary expedients of policy” would make the “dignity and honor of the nation…suffer.”

This was no small challenge: Chase had been in charge of remaking the finances of the United States, and he had both connections and Treasury employees all over the country who owed their jobs to him. In an era in which political patronage meant political victories, he had a formidable machine.

Lincoln managed to quell the rebellion from the radicals. In June 1864, soon after the party—temporarily renamed the National Union Party to make it easier for former Democrats to feel comfortable voting for Republicans—met to choose a presidential candidate, Chase threatened to resign from the Cabinet, as he had done repeatedly. In the past, Lincoln had appeased him. This time, Lincoln accepted his resignation.

But conservatives, too, were in revolt against Lincoln.

Crucially, Thurlow Weed, New York’s kingmaker, thought Lincoln was far too radical. Weed cared deeply about putting his own people into the well-paying customs positions available in New York City, and he was frequently angry that Lincoln appointed nominees favored by the more radical faction.

That frustration went hand in hand with anger about policy. Weed was upset that the Republicans were remaking the government for ordinary Americans. The 1862 Homestead Act, which provided western land for a nominal fee to any American willing to settle it, was a thorn in his side. Until Congress passed that law, such land, taken from Indigenous tribes, would be sold to speculators for cash that went directly to the Treasury. Republicans believed that putting farmers on the land would enable them to pay the new national taxes Congress imposed, thus bringing in far more money to the Treasury for far longer than would selling to speculators, but Weed foresaw national bankruptcy.

Even more than financial policy, though, Weed was unhappy with Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which moved toward an end of human enslavement far too quickly for Weed.

On August 22, Weed wrote to his protégé Secretary of State William Henry Seward that he had recently “told Mr. Lincoln that his re-election was an impossibility…. [N]obody here doubts it; nor do I see anybody from other states who authorises the slightest hope of success.”

“The People are wild for Peace,” he wrote, and suggested they were unhappy that “the President will only listen to terms of Peace on condition Slavery be ‘abandoned.’” Weed wrote that Henry Raymond, another protégé who both chaired the Republican National Committee and edited the New York Times, “thinks Commissioners should be immediately sent to Richmond, offering to treat for Peace on the basis of Union.”

On August 23, 1864, Lincoln asked the members of his Cabinet to sign a memorandum that was pasted closed so they could not read it. Inside were the words:

“This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards. — A. Lincoln”

But then his fortunes turned.

Just a week after Weed foretold his electoral doom, the Democrats chose as a presidential candidate General George McClellan, formerly commander of the Army of the Potomac, in a transparent attempt to appeal to soldiers. But to appease the anti-war wing of the party, they also called for an immediate end to the war. They also rejected the new, popular measures the national government had undertaken since 1861—the establishment of state colleges, the transcontinental railroad, the new national money, and the Homestead Act—insisting on “State rights.”

Americans who had poured their lives and fortunes into the war and liked the new government were not willing to abandon both to return to the conditions of three years before.

Then news spread that Rear Admiral David Farragut had taken control of Mobile Bay, the last port the Confederates held in the Gulf of Mexico east of the Mississippi River. On September 2, General William T. Sherman took Atlanta, a city of symbolic as well as real value to the Confederacy, and set off on his March to the Sea, smashing his way through the countryside and carving the eastern half of Confederacy in half again.

Reelecting Lincoln meant committing to fight on until victory, and voters threw in their lot. In November’s election, Lincoln won about 55% of the popular vote compared to McClellan’s 45%, and 212 electoral votes to McClellan’s 12. Lincoln won 78 percent of the soldiers’ vote.

After his reelection, Lincoln explained to a crowd come to serenade him why it had been important to hold an election, even though he had expected to lose it:

“We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.”

Happy Presidents Day.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#History#Abraham Lincoln#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters from An American#defense of democracy#American Civil War

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

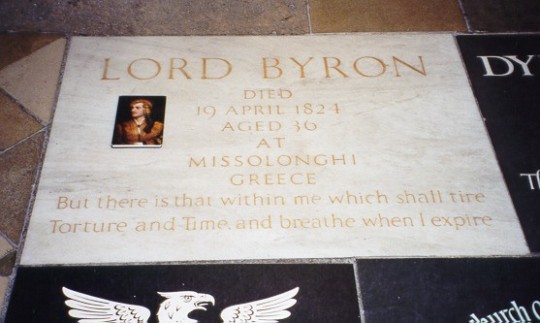

The Romantic Poet Lord Byron died on 19th April 1824.

George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron of Byron was born in London on January 22nd 1788 to Captain John Byron and Catherine Gordon, heiress of Gight in Aberdeenshire.

After his father, known as “Mad Jack”, had frivolled away much of her fortune, Catherine whisked her son away to Aberdeen in 1789 where he spent his formative years, it was this time that left a mark on the romantic poet, he always saw himself as a Scot after this.

His father died when he was three, his half-sister was shipped off to live with their maternal grandmother, and he lived in miserable lodgings with his volatile, depressed mother and their abusive nurse. Aged ten his great-uncle William unexpectedly died in 1789, leaving young Byron to take up the reigns as sixth Baton Byron of Rochdale. The family moved to Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire, and he was later educated at Harrow and The University of Cambridge.

Despite enduring such ordeals as a young child in the north east of Scotland, the poet was empowered by his Scottish bloodline. Aged just 19, he wrote of his love for the northern countryside in ‘Hours of Idleness’, distinctly unimpressed by the comparatively barren landscapes of the south, the evidence is in the third verse of the poem Dark Lochnagar, for those unconvinced about his “Scottishness”

England! thy beauties are tame and domestic

To one who has roved on the mountains afar

Oh for the crags that are wild and majestic

The steep frowning glories o’ wild Lochnagar.

As the poet entered into his late teens and early twenties, his life was quickly overwhelmed by scandal – among his affairs with married women, actresses and young men, it is thought he had a child with his half-sister Augusta, five years his elder, a scandalous life at any time, let alone 18th century England!

In what is considered his masterpiece, Don Jaun, he again hankers back to Scotland, the work is over 500 pages long, split into canto’s. Canto X (ten) gives us another wee glimpse with….

But I am half a Scot by birth, and bred A whole one, and my heart flies to my head, —

As “Auld Lang Syne” brings Scotland, one and all, Scotch plaids, Scotch snoods, the blue hills, and clear streams, The Dee — the Don — Balgounie’s brig’s black wall, All my boy feelings, all my gentler dreams Of what I then dreamt, clothed in their own pall, Like Banquo’s offspring; — floating past me seems My childhood in this childishness of mine: I care not — ‘t is a glimpse of “Auld Lang Syne.”

And though, as you remember, in a fit Of wrath and rhyme, when juvenile and curly, I rail’d at Scots to show my wrath and wit, Which must be own’d was sensitive and surly, Yet ‘t is in vain such sallies to permit, They cannot quench young feelings fresh and early: “scotch’d not kill’d” the Scotchman in my blood, And love the land of “mountain and of flood.”

Byron's body was embalmed but his heart buried under a tree in Messolonghi in Greece. His remains were sent to England for burial in Westminster Abbey, but for some reason the Abbey refused.

He is buried at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Hucknall in the family vault.

In later years, the Abbey allowed a duplicate of a marble slab given by the King of Greece, which is laid directly above Byron's grave. In 1969, 145 years after Byron's death, a memorial to him was finally placed in Westminster Abbey.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

(you can ignore this I just had a hankering for angst -- MT)

*in your ask box is a tupperware container and a mason jar. The mason jar has in Leggy's shitty writing "Phoenix" and it has a brown liquid in it. On top of the tupperware is a note.*

"Dear Phoenix,

"I don't understand what's happening or what you're doing, but no matter what I'm here for you. In the jar is a quart of sweet tea, just as sweet as you like it, and in the tupperware is some pork, rice, and tomatoes. It's all separated with this partition thing because I know you're particular, but it tastes good together.

"I love you,

"Dad."

*it's clearly from Leggy.*

-- @b1gm0n3yb1gg3rc4n3

(Phoenix finds the gift and furrows his brow. He picks up the note and reads it, his heart hurting slightly as he did.)

(He picked up the Tupperware and mason jar, taking them inside and setting them on the table. He got a fork and a straw from a drawer, prepping to actually eat. It would be the first real thing he’s eaten in…a while.)

“I should say thank you,” Phoenix muttered to himself as he opened the mason jar and put the straw in. He took a big sip and felt tears prick at his eyes. It was just like being back home.

Phoenix reheated the food and ate it, keeping it mostly apart except for the last few bites where he mixed everything together. It was damn good, better than anything he’s eaten since he left.

After he was done, he set the Tupperware in the sink and took the mason jar with him to his room. George was sitting on his floor in a pile of blankets, and Phoenix let out a soft sigh and the sight of him.

“Hi, bud,” Phoenix murmured, feeding him one of the tomatoes that he had purposely not eaten. After he tucked the note into his nightstand, Phoenix settled down on the bed, holding the sweet tea as close to him as he could. His thumb ran over the writing on it, trying to keep himself from crying.

He’d make time to sneak onto the Shadow Company base and visit if he could. Or, at least, he told himself he would. In actuality, he would probably just write a letter and leave it on Leggy’s desk for him to find later.

But, for now, Phoenix would slowly sip at the sweet tea and imagine what he would say if—no, when—he saw his Dad again.

#I LOVE YOU MISSUS!!!!#I LOVE ANGST!!!!#this was so much fun to write thank you pookie 🙏🏻#father dearest#after the ashes settle

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last show day in Yongin, South Korea (28 May 2023) and the end of the penultimate week in that country before Asia Tour 2022-2023 shifts to Taiwan.

Sophie-Rose Middleton as Electra has some fun during the bows with Xavier Pellin as Mistoffelees.

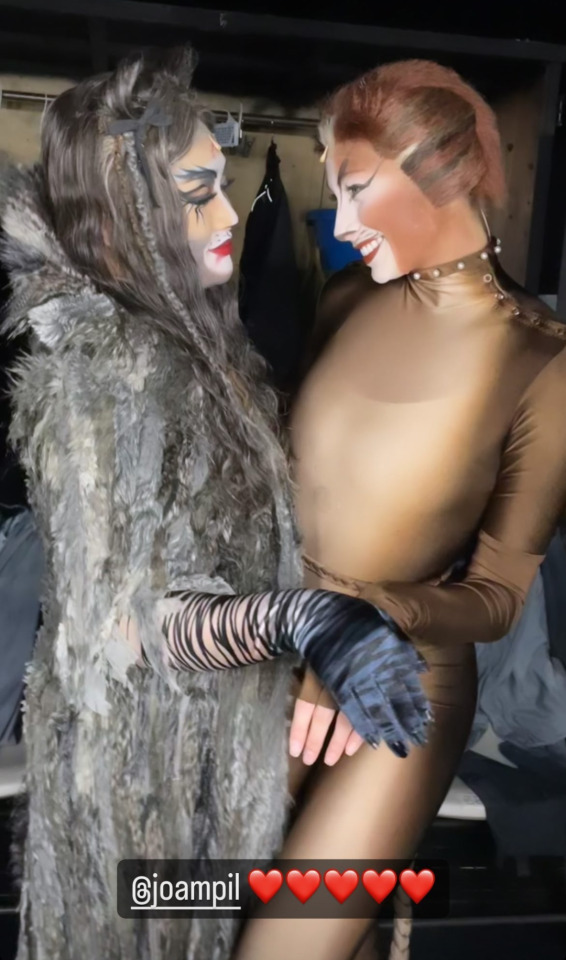

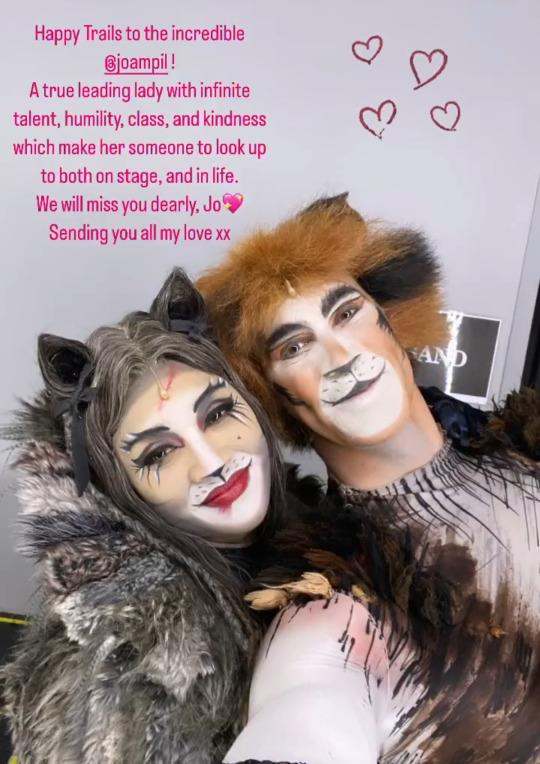

Joanna Ampil's last show as Grizabella was today (leaving for another show as usual) and some of the cast wished her off.

With Katie Hutton as Rumpleteazer, Isabella Roberts as Victoria, George Hankers covering Carbucketty, Taryn Donna as Cassandra, and Saverio Pescucci as Admetus.

#CATS Musical#CATS the Musical#CATS Asia Tour 2022-2023#CATS Korean Tour 2022-2023#Electra#Sophie-Rose Middleton#Mistoffelees#Xavier Pellin#Grizabella#Joanna Ampil#Victoria#Isabella Roberts#Rumpleteazer#Katie Hutton#Cassandra#Taryn Donna#Carbucketty#George Hankers#Admetus#Saverio Pescucci

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

source

#cats korea tour 2022#backstage cats#gabrielle parker#jemima (cats)#victoria (cats)#rumpelteazer#cian hughes#mungojerrie#george hankers#george (cats)#katie hutton#isabella roberts#meghan peploe williams#tantomile#petra ilse dam#bombalurina#taryn donna#cassandra (cats)#anneka dacres#demeter (cats)#sophie rose middleton#electra (cats)#alice batt#jellylorum#madison green#jennyanydots#see the queue on a sunflower

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad Arguments

Elizabeth I

Girls Could Marry At Twelve

Freaks portray this wickedness as an oh-so noble concern for historical truth.

And YOU wouldn't object to Duh Twoof, would you now?

Oh! Ah! Well! It may seem like abuse to us But We Must Remember that Girls Could Marry At Twelve...

I love being implored to Remember the lies they've not told me yet.

Notice how it always begins with a feigned nod of empathy:

Hah! Yes! Of course. I hate it too. I really disapprove of This Sort Of Thing. Honest!

Before introducing the actual message:

But if you were A Reel Intelleckchul, like me, you would Understand that It Was Like That Then, and Perfectly Normal.

Besides the unsaid conclusion:

That means I'm right to blame Elizabeth.

The endless counter arguments to this have all been said before, and are near-enough a waste of words, for this isn't silly, muddle-headed ignorance but open malice, and agendas don't care about facts.

Because really, how would the customs governing matrimony apply to this situation?

Where does marriage figure in a middle-age man breaking into his stepdaughter's room to molest her?

Well here's the distraction technique:

Soon as we get to incestuous pædophilia, start wittering about wedlock and how it's ackshully alright to touch kids...in the time period, of course.

WHAT?!

If I believe Tudor society took a lax view of preying upon children, then by this very argument, that attitude could ONLY ever exist with regards to marriage.

They want me to accept Seymour Did Nothing Wrong, because his era allowed him to marry a girl of twelve.

This implies consummation followed immediately, although they never say as much, precisely as it is too big of a lie, hinting at it instead to let your subconscious join the dots.

BUT, if his entire defence is nothing better than blabbering about how he can sleep with a twelve‐year-old bride if he wants to, then he needed to marry Elizabeth beforehand for this to be alright.

But not only had Seymour not married her, he already had a wife, so his behaviour alone is a simply lovely mix of fornication, adultery AND incest.

And last time I looked, the Tudors came down hard on all three.

Oh yeah. They killed Anne and George for less. But ten years later? Totally normal!

I hate this Bad Argument with such deep, boiling fury I'm about to rip it apart, so no one ever can ever sew its tattered chunks together again.

It is absurd to the point of evil, as just think about what they are saying.

Seymour forces his way into Elizabeth's room to grope and spank her.

Me: That's abuse, that!

Them: Oh you thick, detestable pleb. Girls Could Marry At Twelve, doncha know.

As when Seymour molested Elizabeth, he wasn't really molesting her, because she was old enough to marry him.

And you can't sexually assault adults.

...

Once a gal can get married, it's every fella's sworn duty to come at her, for she wants 'em.

She wants 'em all.

She does, man! She's just being difficult!

You know how it goes:

6th September 1545: Little girl.

7th September 1545: WAHMAN!!!

Soon at that clock struck midnight, a switch flicked in Elizabeth's brain, and ever after she had a hunger...for MAN.

And Seymour just couldn't bear to see her hankering and not go providing like a true hero.

It would've been cruel NOT to do it.

Of age? Well say no more.

Come one, come all. Open for business.

And if she complains, well that's just playing hard to get, innit?

No escape now, love.

Legally capable of marriage? Well you want it whatever you say.

Stop struggling.

Same with Elizabeth. I mean, come on, Girls Could Marry At Twelve.

So obviously, if she hadn't really wanted it, she would've stayed eleven forever.

Is that so much to ask?

But oh no, she just so happened to have thirteen birthdays beforehand like a slut.

Ah-hah! Gotcha now! That little innocent routine don't fool me!

Then she has the nerve to play the victim as if it isn't all her fault for growing.

And then idiots blame Seymour for taking his rights when she made herself fully available by not dying in childhood, the selfish bitch.

Look at her, not being dead! Tempting him!

This Bad Argument is ONLY ever used by women to defend men attacking other women and girls, so please remember it's composed of three lies:

1. Seymour Did Nothing Wrong, because she was over twelve.

2. Elizabeth clearly loved every minute, because she was over twelve.

3. Sleeping with children was Perfectly Fine for most of human history and it's our prissy, overreacting modern hysteria about it that's the The Real Problem.

Why? Because if they can push you to accept it was normal then, it's the first step towards pushing you to accept it's normal now.

0 notes

Text

I acknowledge a list of names is not enough, so here are some sources and or direct quotes from the historical figures I mentioned who supported Palestine:

Einstein: “I should much rather see reasonable agreement with the Arabs on the basis of living together in peace than the creation of a Jewish state. Apart from the practical considerations, my awareness of the essential nature of Judaism resists the idea of a Jewish state with borders, an army, and a measure of temporal power no matter how modest. I am afraid of the inner damage Judaism will sustain - especially from the development of a narrow nationalism within our own ranks, against which we have already had to fight without a Jewish state”

— Albert Einstein

“The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me. The sanction for it is sought in the Bible and the tenacity with which the Jews have hankered after return to Palestine. Why should they not, like other peoples of the earth, make that country their home where they are born and where they earn their livelihood? Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct. The mandates have no sanction but that of the last war. Surely it would be a crime against humanity to reduce the proud Arabs so that Palestine can be restored to the Jews partly or wholly as their national home. The nobler course would be to insist on a just treatment of the Jews wherever they are born and bred. The Jews born in France are French in precisely the same sense that Christians born in France are French”

— Mahatma Gandhi

— Muhammad Ali

— Stephen Hawking

— Malcolm X

— Fred Hampton

— Nelson Mandela

— Noam Chomsky

— Rev. Dr. MLK Jr.

— Jimmy Carter

— Bernie Sanders, literally a few days ago

According to Zionist logic, the following historical figures would have been considered “Hamas Terrorist Nazi Antisemites” because they were a) critical of Israeli war crimes and b) supported Palestinians:

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Mahatma Gandhi

Malcolm X

Fred Hampton

Nelson Mandela

Albert Einstein (is Jewish)

Stephen Hawking

Frida Kahlo (is Jewish)

Noam Chomsky (is Jewish)

DJ KHALED 🗣️🗣️🗣️🗣️🗣️

Muhammad Ali

Jimmy Carter

Ben and Jerry (the ice cream people)

Bernie Sanders (is Jewish)

Susan Sarandon

Now, let’s look at some of the people who have supported Israel since its creation and do to this day/until their death beds:

Donald Trump

Joseph Stalin

Joe Biden

George W. Bush

Bibi Netanyahu (Israeli PM)

Hillary Clinton

Jefferey Epstein

According to Zionist logic, the man who called white supremacists in Charlottesville who chanted “Jews will not replace us”, “fine good people” and the dictator of the USSR who actively persecuted Jews in SSRs like Lithuania, Sakartvelo, and Russia are both actually based liberal kings

19 notes

·

View notes