#Gabriel Fallopius

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

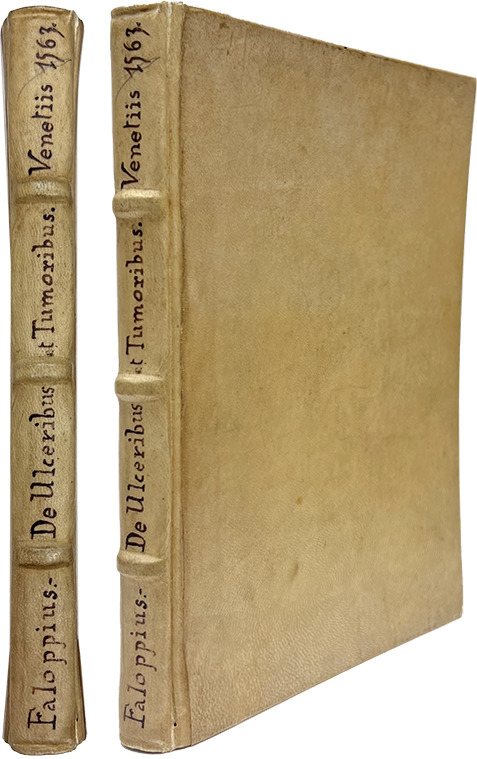

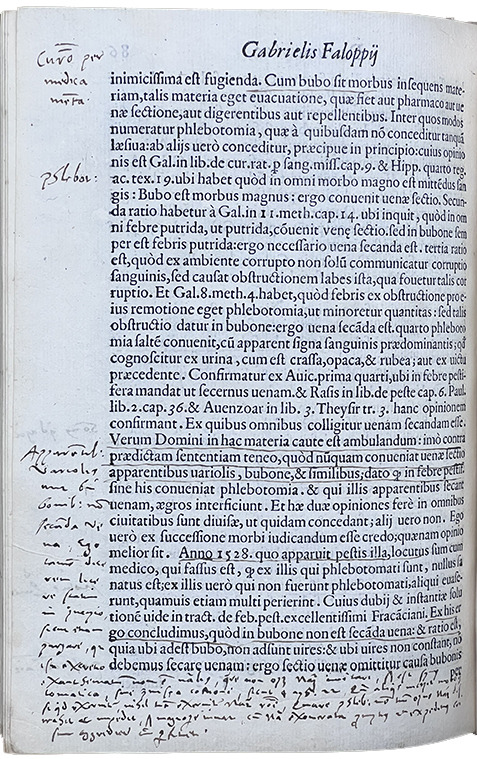

FALLOPIUS, GABRIEL (1523-1562). Libelli duo, alter de ulceribus: alter de tumoribus praeter naturam [Two pamphlets, one on ulcers: the other on unnatural tumors]. Printed in Venice by Donato Bertelli, 1563.

Happy new year, everyone! I think we can all agree that 2022 was a little weird. Perhaps that is just the new normal?

Embracing this new weird normal, we decided to highlight a book this month on skin and skin diseases from a 16th-century Italian anatomist known most widely for his work on reproductive organs.

Gabriel Fallopius (aka Gabriele Fallopio) had a relatively short but incredibly impactful career. The one-time priest was a physician, anatomist, surgeon, dentist, professor, and celebrated lecturer.

Although mostly known now for the eponymous Fallopian Tubes (called "oviducts" in all other mammals), the tubes in human females through which eggs travel from the ovaries to the uterus, he was known in his own time as a student of some of the most famous physicians of the time, an excellent anatomist, and for supplying corrections to the work of Vesalius.

He was enthralled by anatomy and seemingly interested in all parts of the body. This is evidenced by the number and variety of anatomical structures named after him. Beyond anatomy, he also worked with medicinal plants and has a genus in the buckwheat family named after him.

As a physician, he is credited with creating the condom in an effort to prevent the spread of syphilis (supposedly tied off with a pink ribbon to make it more appealing for women).

Fallopius's greatest work, Observationes anatomicae, is a commentary on Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica that attempts to correct Vesalius based on Fallopius's own observations. As you can imagine, Vesalius did not take kindly to this and attempted to publicly discredit his friend. He was unsuccessful.

However, this month we highlight one of his lesser-known works on skin and skin diseases, Libelli duo, alter de ulceribus: alter de tumoribus praeter naturam [Two pamphlets, one on ulcers: the other on unnatural tumors]. It is one of the most thorough works of its kind up to the time of its publication.

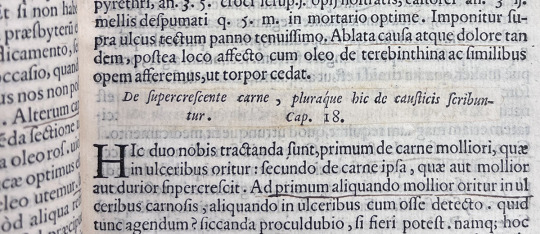

Fallopius not only describes the illnesses and their various presentations but also innovations in treatment. He suggests new techniques for the cauterization of ulcers and the removal of tumors.

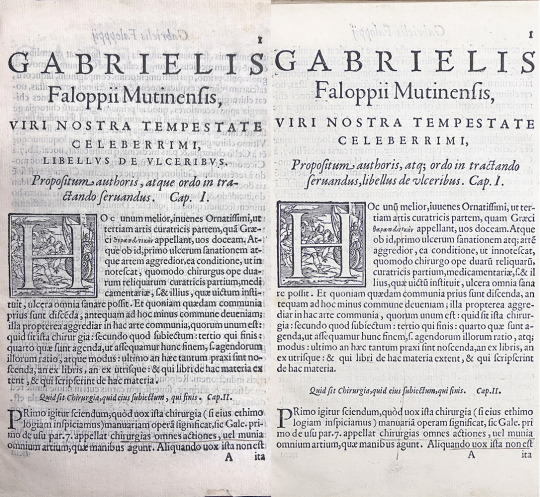

The first leaf of our book looks like it was meant to be canceled (replaced with a corrected leaf), but instead, the new leaf was added and the old leaf was retained. This is somewhat unusual and very handy for folks studying the creation of this particular edition and book production, in general, at that time.

The book is broken into chapters, several for each main topic. As can be seen in the banner image above, chapter 18 of the ulcers topic was corrected by pasting a new chapter heading over the old one. Unlike the canceled first leaf, though, this is not unique to this volume. The new chapter 18 heading can be seen in multiple digitized copies.

Finally, the book has clearly been well cared for. It is in great condition and filled with marginal notes by a careful reader. It is another great example of these beautiful artifacts that combine the history of medicine, early book production, readership, and conservation practices!

Fallopius died at the (very young!) age of 39, most likely from tuberculosis. Although he practiced for less than twenty years, his impact on medicine - especially anatomy - was immense.

#Gabriel Fallopius#uiowa#special collections#libraries#jmrbr#hardin library#medical history#anatomy#rare books

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In 1559, for example Columbus—not Christopher but Renaldus—claims to have discovered the clitoris. He tells his "most gentle reader" that this is "preeminently the seat of woman's delight." Like a penis, "if you touch it, you will find it rendered a little harder and oblong to such a degree that it shows itself as a sort of male member." Conquistador in an unknown land, Columbus stakes his claim: "Since no one has discerned these projections and their workings, if it is permissible to give names to things discovered by me, should be called the love or sweetness of Venus." Like Adam, he felt himself entitled to name what he found in nature: a female penis.

[...]

Columbus' colleagues, meanwhile, attacked him with equal vigor. Gabriel Fallopius, his successor at Padua, insisted that he—Fallopius—saw the clitoris first and that everyone else was a plagiarist. Kaspar Bartholin, the distinguished seventeenth-century anatomist from Copenhagen, argued in turn that both Fallopius and Columbus were being vainglorious in claiming the "invention or first Observation of this Part," since the clitoris had been known to everyone since the second century. "

- Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud, Thomas Laqueur

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

October 9th 1562, death of Catholic priest, Italian anatomist, namesake of the Fallopian tubes, and pioneer of condom use to prohibit sexually transmitted diseases, Gabriel Fallopius; one of the most important figures in medicine and anatomy in the sixteenth century, despite his death on this day aged only 39. Fallopius inherited and continued the anatomical work begun in Padua, Italy by his predecessor Vesalius, the pioneer of modern anatomical study, and author of ‘De humani corporis fabrica’ (On the Fabric of the Human Body), published in 1543. Vesalius it was noted last week died on the 2nd of October 1564, by the effects of a shipwreck, on his way to the Holy Land in mysterious circumstances, accused by his detractors of performing an autopsy on a living person, and fleeing from the Inquisition. As a young man Vesalius had been taught by Dutch physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker Gemma Frisius, who also taught the Welsh astronomer, astrologer and occult philosopher John Dee. As head of anatomy at the University of Padua, Fallopius taught Hieronymus Fabricius, known as the "The Father of Embryology”. In 1594, Fabricius designed the first theatre for public anatomical dissections, and also designed an orthopedic exoskeleton he called the ‘Oplomoclion’. Fabricius would himself teach the English physician William Harvey, the first known physician to completely map systemic circulation, and describe in detail the properties of blood pumped to the brain and the rest of the body by the heart. Theories he would publish in 1628 as ‘De Motu Cordis’. Harvey also from 1618 was 'Physician Extraordinary' to King James I. In keeping with the monarch’s paranoia (Continued in the comments). #darkillustration #darkillustrations #witchcrafthistory #witchhistory #16thcentury #17thcentury #17thcenturyart #historyofscience #superstitions #folklore #strangehistory #historyofphilosophy #williamharvey #witchtrials #jamesi #witchfindergeneral #pendlewitches #folklore #witchartist #morbidhistory #anatomical #anatomicalart #historyofanatomy #scientificrevolution #fallopian #sciencehistory #anatomy #anatomytheatre #physician #sciences https://www.instagram.com/p/CUxhYvllQed/?utm_medium=tumblr

#darkillustration#darkillustrations#witchcrafthistory#witchhistory#16thcentury#17thcentury#17thcenturyart#historyofscience#superstitions#folklore#strangehistory#historyofphilosophy#williamharvey#witchtrials#jamesi#witchfindergeneral#pendlewitches#witchartist#morbidhistory#anatomical#anatomicalart#historyofanatomy#scientificrevolution#fallopian#sciencehistory#anatomy#anatomytheatre#physician#sciences

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

CATHOLIC INVENTIONS AND DISCOVERIES. Some one writes us to know, what Roman Catholics have ever invented? There is the shillalah, and — well — we cannot think of anything else. Write to the Catholic News: it will probably be able to prove that every inventor that ever lived was a Roman Catholic, or, at least, that he ought to have been. The above clipping is from the Boston Investigator of June 15. Yes, the Roman Catholics invented the "shillalah." It was a necessity forced upon them by people whose skulls are so thick that nothing short of a shillalah will make an impression upon them or open a place large enough to allow the truth to penetrate. Mons. C. F. Cheve, formerly a collaborator of M. Proudhon, the celebrated French revolutionary writer, once a bitter enemy of the Catholic Church, will assist us. Upon his authority we are justified in saying that Catholicity has created a representative form of government; founded the system of trial by jury; inundated Christendom with its benevolent institutions; commanded its Bishops, by the Sixth Council of Arles, to protect and defend the poor and oppressed; created arts, literature and languages, and every modern science; invented in the tenth century the system of Arithmetic by the monk Gerbert; Algebra by the monk Lucca di Borgo; the musical gamut by two Benedictines of St. Armand; discovered in the fourth century, the circulation of the blood by Bishop Numiscus; the laws of anatomy by Fallopius, Canon of Modena, whose name is still given to a certain part of the human anatomy ; the laws of light by a Sicilian Abbot, Maurolgio ; the laws of electricity by two ecclesiastics, Lun and Brecaria; conceived the force of attraction, steam, use of power, aerostatics; magnetism, by the monk Roger Bacon; modern astronomy by Canon Copernicus and Cardinal de Cresu; established the laws of mineralogy by a Canon of Paris; invented clock mechanism, by Richard, Abbot of St. Albans, in the fourth century; telescopes by monks; spectacles by Dominican Alessandro Spina; lightning conductors by a Moravian Priest, Procopius Divish; telegraphs by the Abbe Chappe; the first piano was constructed in 1711 by an English monk, in Rome, Rev. Father Wood; the first book printed in the New World was the Spiritual Ladder of St John Climacus, printed in Mexico; the first quarto Bible printed in this country was published by Matthew Carey & Co., Philadelphia in 1790; the discoverer of the Salt Springs at Onandaga, N. V., was the Jesuit Father Simon Le Moyne, in 1654; the first who called attention to the mineral oil near Lake Erie was the Franciscan, Father dc la Roche d'Allion, in 1627; the first who worked the copper mines on Lake Superior was a Jesuit lay Brother; the first cargo of wheat that went down the Mississippi from Illinois, was raised at a Jesuit Mission; the first sugar cane was raised by the Jesuits in New Orleans; the first book printed west of the Alleghanies was the Epistle and Gospels in French and English, printed at Detroit by T. Mettez, in 1812; and the first printing press set up in the northwest, was by Father Gabriel Richard, priest and member of Congress from Michigan; the division of the Holy Bible into chapters was made by Cardinal Hugode Santo Caro, a Dominican, who lived in the middle of the thirteenth century; Sunday-schools were first founded by St. Charles Borromeo in Milan; Night schools were founded in Rome in 1819 by Giacomo Casaglio; the earliest book printed was a Latin Bible commonly called the Mazarin Bible, supposed to have been issued between 1452 and 1456, long before Luther's time; the Eucalyptus trees planted in the Roman Campagna to purify the atmosphere and make the place inhabitable were planted by Trappist monks. We need not refer to the astronomical discoveries made by Father Curci, the Jesuit, and still later by other Jesuit Fathers at Georgetown College. We feel that we have given the investigator enough information for this time. Besides we think it only fair, — if we are not attacked again — to leave some discoveries to people who are not Catholics.

Boston College, The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 8, Number 10, 30 July 1892

#Catholic#Catholicism#Christian#Christianity#Boston College#science#inventions#Jesuit#Franciscan#Dominican#priests#religion#books#Bible#civilisation#education

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benjamin Banneker and a Cascade of Coincidences

Benjamin Banneker and a Cascade of Coincidences

Well, even I have to take a day off…sort of. So, 9 October, a whole lot of things happened. Charlemagne and his brother Carloman were crowned Kings of the Franks in 768; Louis VII of France married the only daughter of Henry VII of England, Mary, in 1514; Gabriel Fallopius (the guy who named the fallopian tubes) died in 1562; the siege of Yorktown, Virginia ended in 1781; the first calliope…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Unik, Inilah Kondom Jaman Purbakala

Kabarnusantara.net – Dari catatan sejarah, kondom telah digunakan sejak beberapa ratus tahun lalu. Sekitar tahun 1000 sebelum Masehi orang Mesir kuno menggunakan linen sebagai sarung penganan untuk mencegah penyakit.

Tahun 1500-an untuk pertama kali dipublikasikan deskripsi dan pencobaan alat mencegah penyakit berupa kondom di Italia. Ketika itu Gabrielle Fallopius mengklaim menemukan sarung…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Syphilis was a scary epidemic in the 16th century. One doctor made it less so.

<br>

Ask any social scientist and they'll agree: Humans are really, really, really good at having sex.

But, for as long as we've been having it, we've also been trying to prevent some of the less desirable things that sometimes come along with it — namely unwanted pregnancies and STIs.

Modern science and medical innovation give sexually-active people lots of safe and reliable options to do both, and condoms, in particular, are now extremely effective — preventing pregnancy and STIs about 98% of the time when they're used correctly.

Getting to this point wasn't a quick process though. It involved centuries of trial and error, some terrible ideas (two words: dung sponges), and some serious medical breakthroughs.

A condom from 1813 that might be a bit beyond its expiration date. Image via Lund University Historical Museum/Wikimedia Commons.

Condoms can be traced back to about 3,000 B.C.

According to Greek mythology, King Minos of Crete and his wife, Pasiphaë, used a goat's bladder as a barrier during sex, after several of Minos' mistresses died from the "scorpions and serpents" in his semen.

Over the next several thousand years, Greek, Roman, New Guinea, Chinese, and Japanese civilizations developed and used their own condom variations for women and men using linen, animal bladders, intestines, or a combination of the three. While evidence of condom use continued to appear in art and literature for hundreds of years, it took until the 16th century for a doctor to apply scientific methods to test their effectiveness.

That doctor was Gabriel Fallopius, and his work greatly advanced the human understanding of reproductive health.

An etching of Gabriel Fallopius. Lin-Manuel Miranda hasn't written a musical about his mostly-unknown legacy yet, but he absolutely could. Image via Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons.

By his early-thirties, Fallopius was already considered one of the greatest anatomical researchers of the time. He studied the muscles of the head, the workings of the inner ear, and the nerves and muscles of the human eye. He disproved the theory that the penis entered the uterus during sex. He proved the existence of the hymen in women and discovered the tubes (now called fallopian tubes) connecting the uterus to the ovaries. He reportedly coined the word "vagina" and was the first to describe the clitoris.

With an extensive knowledge of reproduction and biology, Fallopius turned his attention toward the prevention of STIs — namely, syphilis.

"A Harlot's Progress," a famous 17th century etching by William Hogarth featuring a fictional British prostitute, Moll Hackabout, dying of syphilis. Image via The British Museum/Wikimedia Commons.

By the 16th century, syphilis infections had reached epidemic levels across western Europe. Early stage sufferers would endure rashes, joint pains, and fever. Late stage sufferers could go blind, experience heart problems, mental disorders, nerve problems, and eventually, die. Even worse, men and women were carrying the disease unknowingly, contracting it and then passing it on again without ever showing symptoms until they were past the point of treatment. Women of childbearing age were at an added risk because they could pass their infection on to their unborn children, causing birth defects, such as deformed noses, misshapen teeth, blindness, and deafness.

Fallopius and his contemporaries knew enough about syphilis to know that it was transmitted through sexual contact. He further deduced that a barrier preventing the genitals from touching directly during sex could reduce the risk of exposure.

The solution? A thin linen sheath soaked in herbs and unnamed chemicals and then dried.

Men, Fallopius surmised, could wear the sheath during sex — reportedly tied with a ribbon — and potentially prevent infection.

It was a fascinating and simple idea. The next step was proving it worked.

In what is considered to be one of the first historical examples of a clinical trial, Fallopius recruited 1,100 men to test out a sheath during sex.

Gabriel Fallopius describes some of his discoveries to the Cardinal Duke of Ferrara. Painting by Francis James Barraud. Image via Wellcome Images/Wikimedia Commons.

The results were astonishing: not one single participant reported contracting syphilis while using the sheath.

In a book about the experiment published two years after his death, Fallopius reported on his findings: "I tried the experiment [the use of condoms] on 1,100 men, and I call immortal God to witness that not one of them was infected."

Unlike a modern clinical trial, which would confirm patient reports with tests, Fallopius had to trust his participants to tell the truth. Still, the trial was a major breakthrough in STI prevention — and in our collective understanding of the transmission of this deadly disease.

Centuries later, the condom continues to evolve.

Simple, portable, and life-saving. Image via iStock.

Linen and animal intestine sheaths have been replaced with latex, polyurethane or polyisoprene. There are female condoms and condoms of all sizes and shapes for men. They are designed to improve pleasure for both partners, made increasingly thin with ridges, ripples, and other pleasurable accoutrements. Best of all, they're inexpensive, readily available, and easily transportable.

Philanthropist Bill Gates is so convinced of the importance of condom use in aiding sexual wellness in developing countries that, in 2013, he awarded grants to designers who could make an effective condom that doesn't limit sexual enjoyment. The winning design, an ultra-sensitive sheath made partly from bovine collagen, is awaiting approval from the FDA.

Condoms are far from perfect, but when used correctly by consenting partners, they give people more autonomy and control over their bodies.

And while there have been many innovations beyond what he ever dreamed of, we can collectively thank Gabriel Fallopius for his work in helping the science along to where it is today.

<br>

0 notes

Photo

Science & Superstition October 9th 1562, death of Catholic priest, Italian anatomist, namesake of the Fallopian tubes, and pioneer of condom use to prohibit sexually transmitted diseases, Gabriel Fallopius; one of the most important figures in medicine and anatomy in the sixteenth century, despite his death on this day aged only 39. Fallopius inherited and continued the anatomical work begun in Padua, Italy by his predecessor Vesalius, the pioneer of modern anatomical study, and author of ‘De humani corporis fabrica’ (On the Fabric of the Human Body), published in 1543. Vesalius it was noted last week died on the 2nd of October 1564, by the effects of a shipwreck, on his way to the Holy Land in mysterious circumstances, accused by his detractors of performing an autopsy on a living person, and fleeing from the Inquisition. As head of anatomy at the University of Padua, Fallopius taught Hieronymus Fabricius, known as the "The Father of Embryology”. In 1594, Fabricius designed the first theatre for public anatomical dissections, and also designed an orthopedic exoskeleton he called the ‘Oplomoclion’. Continued in comments #historyofscience #sciencehistory #anatomy #anatomyart #anatomyhistory #steampunk #steampunkart #steampunkartist #16thcentury #17thcentury #macabreart #macabre #weirdhistory #strangehistory #witchcraft #witchcraftart #occult #alchemy #alchemyart #occultart #grimoire #history #histology #steampunkhistory #historyart https://www.instagram.com/p/CGNMHSOgRC2/?igshid=64c1h79awbhz

#historyofscience#sciencehistory#anatomy#anatomyart#anatomyhistory#steampunk#steampunkart#steampunkartist#16thcentury#17thcentury#macabreart#macabre#weirdhistory#strangehistory#witchcraft#witchcraftart#occult#alchemy#alchemyart#occultart#grimoire#history#histology#steampunkhistory#historyart

0 notes