#jmrbr

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

From the John Martin Rare Book Room

De nivis usu medico observationes variae by Thomas Bartholin, and printed in Hafniae [Copenhagen] by Matthias Godiche for Peter Haubold [bookseller], 1661.

Happy December, friends. With winter comes snow and frigid temps, of course. As you walk around, breathing in the crisp air and having your face go numb from the wind and snow, you may think to yourself, "Hmm, I wonder if anyone ever considered using snow as anesthesia?" The answer is a stone–cold "yes."

We're highlighting the work from the prodigious 17th–century Danish physician Thomas Bartholin (1616–1680). Beyond looking like Billy Joel in his heavy metal days (yes, that was a thing), Bartholin rocked a strong scientific mind and was a prolific writer. He corresponded with many of the greatest thinkers of his day, wrote over 20 books (including one on unicorns!), and conducted many experiments.

One area he dabbled in was refrigeration anesthesia (the application of cold to deaden sensation, known today as cryoanesthesia). The application of something cold has long been known to help reduce pain. Medieval physicians, such as Ibn Sina, were the first to write about it.

In De nivis usu medico observationes variae [Various observations on the medical use of snow], Bartholin picks up where those medieval writers left off, thoroughly examining all the medical applications of snow, including as a topical anesthetic.

Chapter XXII makes the first known mention of the use of mixtures of ice and snow for freezing to produce surgical anesthesia, crediting the Italian physician Marco Aurelio Severino for the technique. To avoid killing the tissues and causing gangrene, the ice–snow mixture was to be applied in narrow parallel lines to the area designated to be cut. After a quarter of an hour, feeling would be deadened and the part could be cut without pain.

Along with about 200 pages detailing all the medical properties of snow (who knew there were so many!), there is also a treatise on snow crystals by Bartholin's younger brother, Erasmus. This is the earliest publication on crystallography and preceded Boyle's Essay about the origine & virtues of gems (1672) by eleven years.

It should be noted that we do not suggest trying Bartholin's methods out for yourself this winter.

--Curator Damien Ihrig

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

FOX, JOSEPH (1775-1816). The natural history of the human teeth. Printed in London for J. Cox, 1803. 100 pages. 13 illustrations. 30 cm tall.

Welcome to spring, everyone! As we count down to longer days, more sun, flowers in bloom, and a twitterpated animal kingdom, I naturally want to talk about...teeth. So let's sink our teeth into Joseph Fox's (1775-1816) The natural history of the human teeth (first edition - 1803).

Joseph Fox was a trailblazer in dentistry who made significant contributions to the field during the early 19th century. Born in London in 1775, Fox received his medical training at Guy's Hospital. A student of John Hunter and Henry Cline, Joseph Fox was eventually appointed the first lecturer on dentistry at Guy's Hospital. He was the first dental surgeon appointed to a hospital position and one of the first medical practitioners to devote themselves completely to the care of teeth.

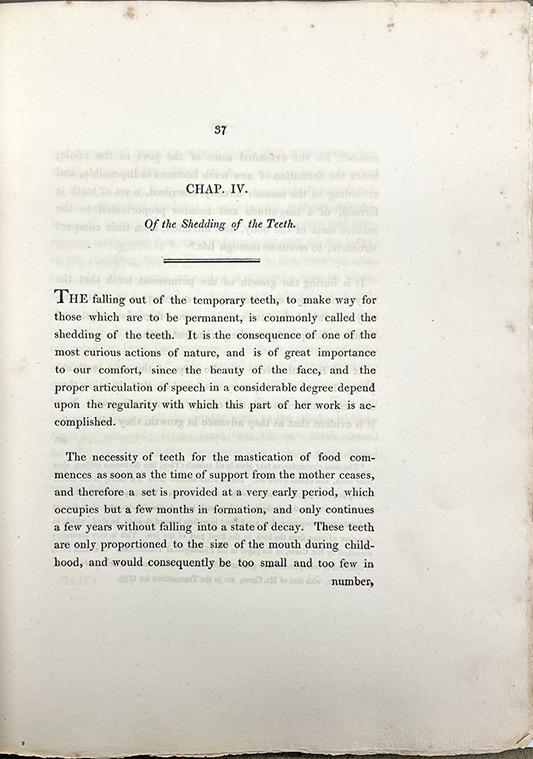

For those with dental anxiety, you can thank Dr. Fox for stressing the need for regular dentist visits. He argued this was especially important for children as they grew and "shed" their first set of teeth.

Fox cared deeply for his profession and wrote and lectured on the importance of improving the quality and standards of dentistry. He stressed that dentistry must have a scientific foundation as it was a medical field.

Beyond teeth, Fox was a passionate proponent of Edward Jenner and vaccination, even offering up his house as a vaccination location, and helped to found the Jenner Society. He was also involved in educational and abolitionist causes.

From 1799 until his death, Fox lectured on dentistry at Guy's Hospital in London. Based on his lectures, he first published The natural history of the human teeth in 1803 and the companion volume, The history and treatment of the diseases of the teeth, in 1806.

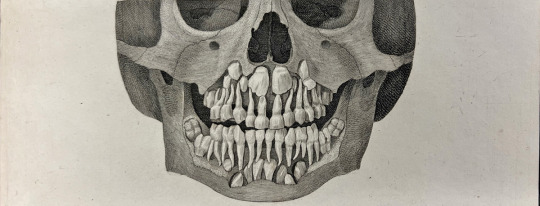

Improving and expanding the work of foundational dental scholars, such as Pierre Fouchard, these were the first works in English to provide instructions for the correction of certain dental irregularities. They also have several detailed and sometimes striking illustrations, including the first to show operative procedures and dental pathologies.

There were many editions, including in other languages, and though much of his theory of oral physiology and pathology was of dubious value, his operative procedures remained in vogue for more than fifty years. Along with the clinical and surgical aspects of the book, Fox also provides his thoughts on the biggest issues in the profession, giving the reader a fuller context of the profession at the time.

The book is bound in blue-painted paper over thin paper boards and rebacked with a thick cloth spine. The book is not only striking for its illustrations but also for the text pages. As can be seen from the image above, the book was printed with slightly larger type and very large margins. Anyone with eyesight as poor as mine is grateful for that.

--Curator Damien Ihrig

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library of the Health Sciences

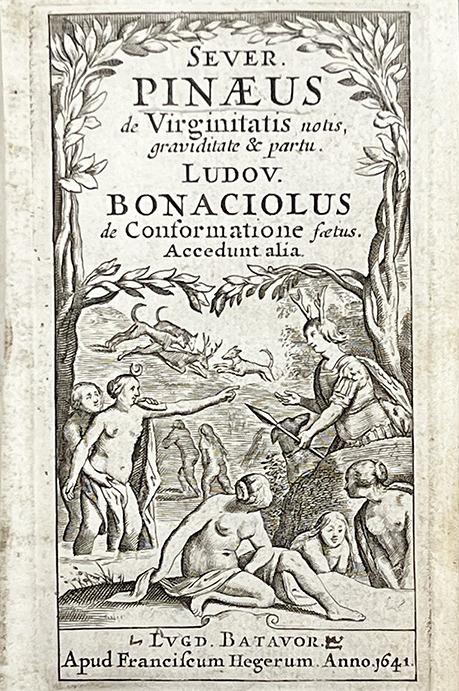

PINEAU, Severin (1550?–1619). De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis: graviditate item & partu naturali mulierum, opuscula. BONACCIUOLI, Luigi (d. 1540). Enneas muliebris. PLATTER, Felix (1536-1614). De origine partium, earumque in utero conformatione. GASSENDI, Pierre (1592-1655). De septo cordis pervio, observatio. SEBISCH, Melchior (1578-1674) De notis virginitatis. Third edition. Printed in Leiden by Francis Heger, 1641. 28 pages. 13 cm tall.

We are big fans of tiny books here at the JMRBR. And banned books, too. So we thought we would highlight a curious little book packed with a number of treatises on obstetrical and gynecological topics, once considered so risqué that it was condemned and banned in several locations. Not coincidentally, it was also a hit that spurred the printing of several editions. The book is also fascinating for its illustrations.

This volume is a collection of gynecological and obstetrical texts. The content, especially the first and last works, caused quite a stir due to the frankness and detail regarding virginity (and how it is lost), pregnancy, and childbirth - so much so that it was confiscated in many locations. Naturally, it was also very popular and printed in several editions.

And by "virginity," the authors specifically mean female virginity. Authors of early medical works surprisingly did not seem too interested in male virginity! All snarkiness aside, the study of female anatomy and physiology, especially of anything to do with sex, pregnancy, and birth, has a long and problematic history. We encourage you to read more about this history here and here and here and here. This is by no means an exhaustive list.

Five works are gathered under the main title, De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis: graviditate item & partu naturali mulierum, opuscula [On the integrity and corruption of known virgins], by the 16th-century French surgeon Séverin Pineau (1550?–1619). Pineau was born in Chartres but trained and practiced in Paris and was surgeon to several French kings. He is most known for his works on gynecological and obstetrical topics, including as an advocate for symphysiotomy (also known as a pelviotomy), a procedure performed on women in labor in which the cartilage of the pelvis is cut to widen it when there is a problem with the position of the baby. This procedure is rarely performed today, with caesarean section preferred instead.

De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis first appeared as part of Pineau's 1597 work, Opusculum physiologum & anatomicum in duos libellos distinctum. It is divided into two parts. The first provides anatomical descriptions of female genitalia. Interestingly, Pineau uses metaphors when naming certain parts. It was common among French midwives at the time to use metaphors instead of anatomical terms when describing female sexual anatomy (e.g., babolle abbatue), while our old friend, Louise Bourgeois, avoided both metaphor and specifics, referring instead to general areas of anatomy.

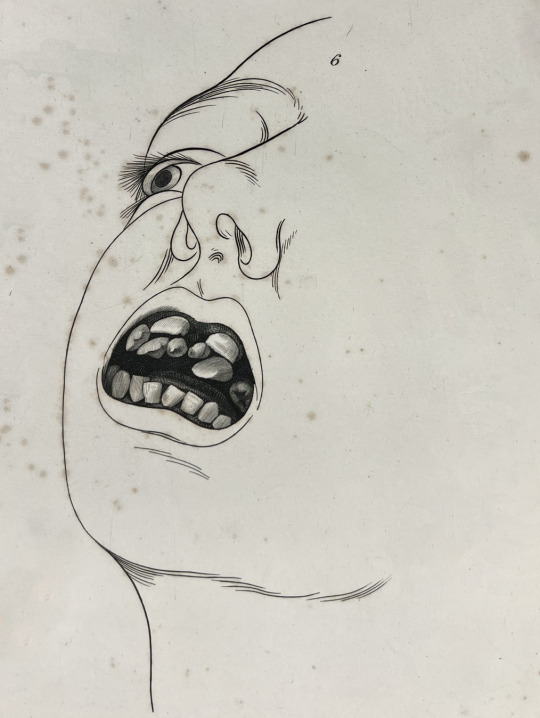

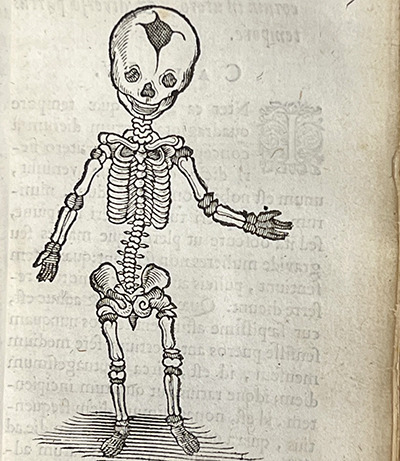

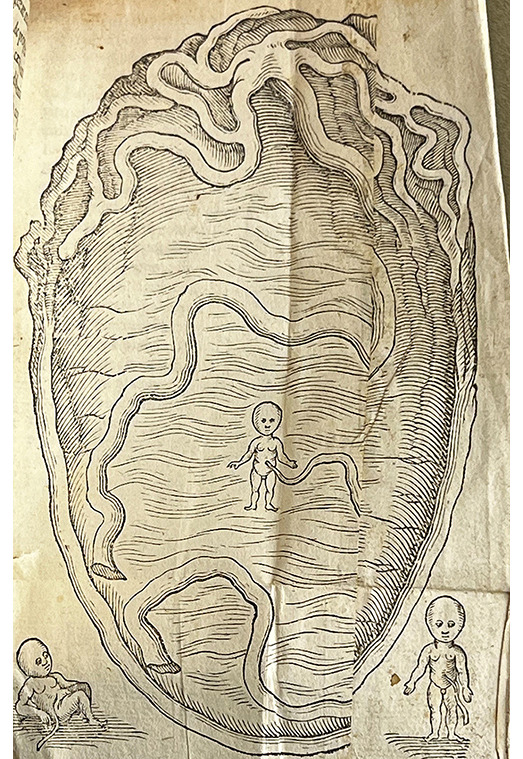

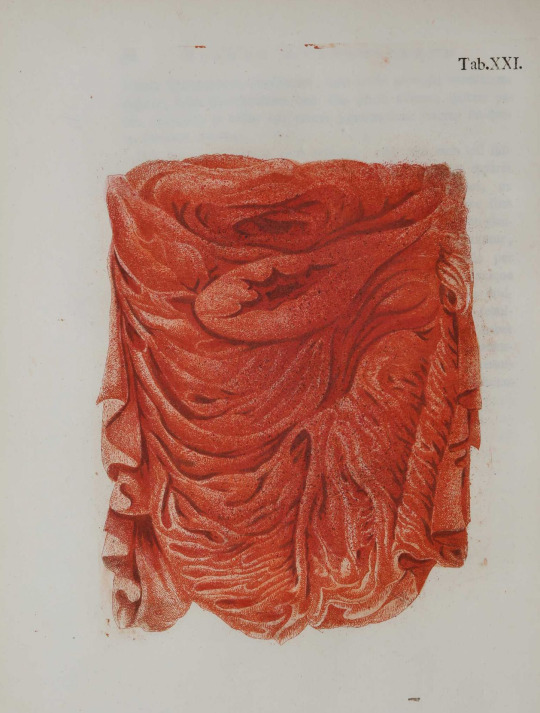

The first part of Pineau's work also lists problems that can occur during pregnancy and labor and surgical methods for treating the problems. The second part covers formation of the fetus. Several interesting woodcut illustrations accompany Pineau's text, including the muscle-bound fetus above.

The second treatise is by Luigi Bonacciuoli (d. 1540s). Bonacciuoli was a physician and anatomist who specialized in obstetrics and practiced at the University of Ferrara in Northern Italy. Enneas muliebris [Treatise on Women in Nine Parts], first printed in about 1505, is a work on obstetrical and gynecological topics based on Bonacciuoli's university lectures. It contains a lengthy dedication to Lucrezia Borgia, the duchess of Ferrara and daughter of Pope Alexander VI and one of the most powerful female leaders of the time.

In the book, Bonacciuoli describes the anatomical structures, such as the mons veneris, the clitoris, and the hymen, and includes a chapter detailing how the fetus is nourished and when fetal movements develop. Other chapters include discussions of the signs of conception, the causes and signs of abortion, delivery, and care of the newborn. He based most of his material on classic works.

The next title belongs to Felix Platter (1536-1614), a Swiss physician and anatomist who practiced at the University of Basel. He remained city physician until his death and was successful in developing the medical school into one of the strongest and finest in Europe. Platter is credited with performing the first public dissection of a human body in a Germanic country and is said to have dissected over 300 bodies during his career. He was widely respected as a teacher and was a physician of great courage who remained in Basel to treat the sick on five occasions when the black plague struck the city. As one of the early nosologists (classifier of diseases), Platter recognized three classes of diseases based on their natural history and postmortem findings and distinguished four types of mental illness. He is best known for his De corporis humani structura et usu, published in 1583.

De origine partium, earumque in utero confirmatione [On the origin of fetal anatomy and formation in the womb] focuses on the formation of the fetus. Platter is chiefly concerned with the origin of the arteries, veins, and nerves from the brain and the relationship of the veins to the heart and liver. This work first appeared in Platter's De corporis humani structura et usu.

The next treatise belongs to the famed French philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician (and opponent of William Harvey), Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655). A Catholic priest with a doctorate in theology, Gassendi was a professor of philosophy and mathematics and believed that experimentation and observation were necessary for the study of science and nature. Among many other contributions to science and philosophy, he is known for the first recorded observation of the transit of Mercury across the sun.

De septo cordis pervio, observatio [Observation on the septum of the heart] is the only appearance in print of this work; there is no separate edition. Gassendi gives the first description of the foramen ovale, a passageway in the fetal heart that allows blood to flow to the left atrium from the right atrium, which closes as the heart fully forms.

The final title is from the Strasbourg physician Melchior Sebisch the Younger (1578-1674). Sebisch (aka Sebizius, Sebizii, and others) was a professor of medicine at the University of Strassbourg, where he eventually took over for his father (Melchior Sebisch the Senior) as the Chair of Medicine. Like many of the other authors on this list, he has many publications to his credit, particularly translations of and commentaries on Galen.

De notis virginitatis [On the characteristics of virginity] bookends Pineau's De integritatis by providing another treatise on the physical signs of female virginity.

The volume is bound in contemporary limp vellum with yapp edges, another callback to our discussion of Louise Bourgeois. The cover shows clear signs of use and aging, with a yellow discoloration, scratches, and staining. The paper is in great condition, with the exception of a torn page and the larger fold-out woodcut illustrations, which have seen a lot of use.

Along with workout warrior fetuses, there are other curious images throughout the book, including the tiny, fully-formed fetus swimming in the cavernous womb seen just above. It is joined by two other fetuses, including one that appears to be taking a moment for some serious rest and reflection.

Most of the illustrations are derived from the work of Guilio Cassesrio, a 16th-century Italian anatomist lauded for the artistry of his illustrations. Each of the fold-outs was also repaired at some point, which unfortunately means we lost part of each image. You can see evidence of these repairs in the womb image.

--Curator Damien Ihrig

#history of medicine#uiowa#libraries#special collections#jmrbr#hardin library#birth#babies#women health#banned books#anatomy#history

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

FALLOPIUS, GABRIEL (1523-1562). Libelli duo, alter de ulceribus: alter de tumoribus praeter naturam [Two pamphlets, one on ulcers: the other on unnatural tumors]. Printed in Venice by Donato Bertelli, 1563.

Happy new year, everyone! I think we can all agree that 2022 was a little weird. Perhaps that is just the new normal?

Embracing this new weird normal, we decided to highlight a book this month on skin and skin diseases from a 16th-century Italian anatomist known most widely for his work on reproductive organs.

Gabriel Fallopius (aka Gabriele Fallopio) had a relatively short but incredibly impactful career. The one-time priest was a physician, anatomist, surgeon, dentist, professor, and celebrated lecturer.

Although mostly known now for the eponymous Fallopian Tubes (called "oviducts" in all other mammals), the tubes in human females through which eggs travel from the ovaries to the uterus, he was known in his own time as a student of some of the most famous physicians of the time, an excellent anatomist, and for supplying corrections to the work of Vesalius.

He was enthralled by anatomy and seemingly interested in all parts of the body. This is evidenced by the number and variety of anatomical structures named after him. Beyond anatomy, he also worked with medicinal plants and has a genus in the buckwheat family named after him.

As a physician, he is credited with creating the condom in an effort to prevent the spread of syphilis (supposedly tied off with a pink ribbon to make it more appealing for women).

Fallopius's greatest work, Observationes anatomicae, is a commentary on Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica that attempts to correct Vesalius based on Fallopius's own observations. As you can imagine, Vesalius did not take kindly to this and attempted to publicly discredit his friend. He was unsuccessful.

However, this month we highlight one of his lesser-known works on skin and skin diseases, Libelli duo, alter de ulceribus: alter de tumoribus praeter naturam [Two pamphlets, one on ulcers: the other on unnatural tumors]. It is one of the most thorough works of its kind up to the time of its publication.

Fallopius not only describes the illnesses and their various presentations but also innovations in treatment. He suggests new techniques for the cauterization of ulcers and the removal of tumors.

The first leaf of our book looks like it was meant to be canceled (replaced with a corrected leaf), but instead, the new leaf was added and the old leaf was retained. This is somewhat unusual and very handy for folks studying the creation of this particular edition and book production, in general, at that time.

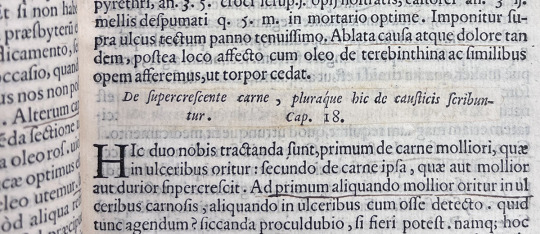

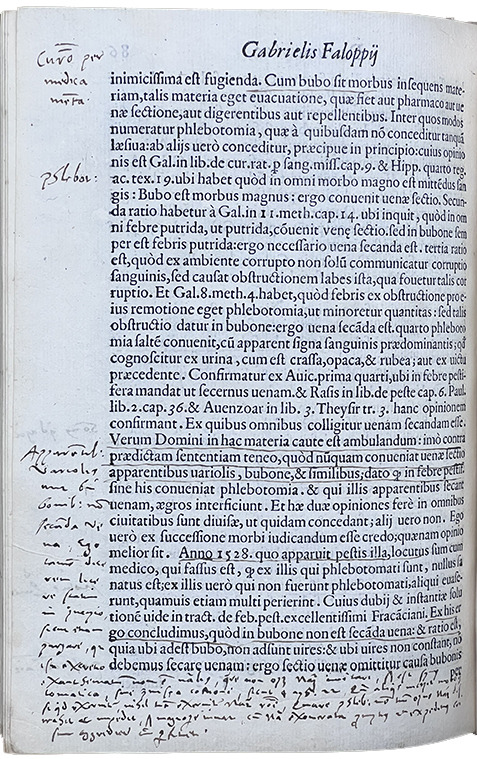

The book is broken into chapters, several for each main topic. As can be seen in the banner image above, chapter 18 of the ulcers topic was corrected by pasting a new chapter heading over the old one. Unlike the canceled first leaf, though, this is not unique to this volume. The new chapter 18 heading can be seen in multiple digitized copies.

Finally, the book has clearly been well cared for. It is in great condition and filled with marginal notes by a careful reader. It is another great example of these beautiful artifacts that combine the history of medicine, early book production, readership, and conservation practices!

Fallopius died at the (very young!) age of 39, most likely from tuberculosis. Although he practiced for less than twenty years, his impact on medicine - especially anatomy - was immense.

#Gabriel Fallopius#uiowa#special collections#libraries#jmrbr#hardin library#medical history#anatomy#rare books

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room!

At the Hardin Library of Health Sciences

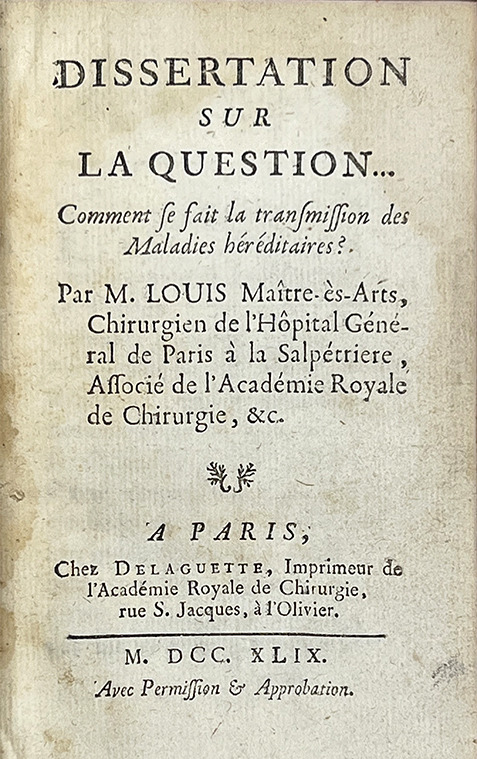

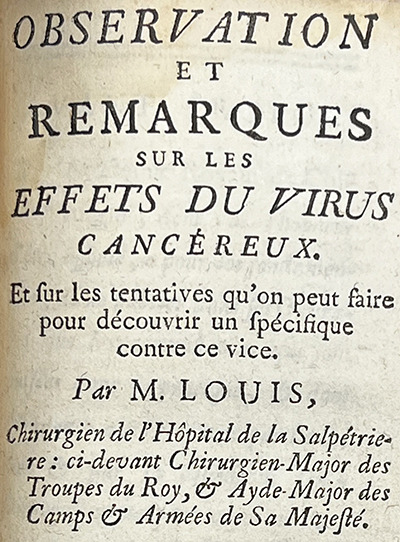

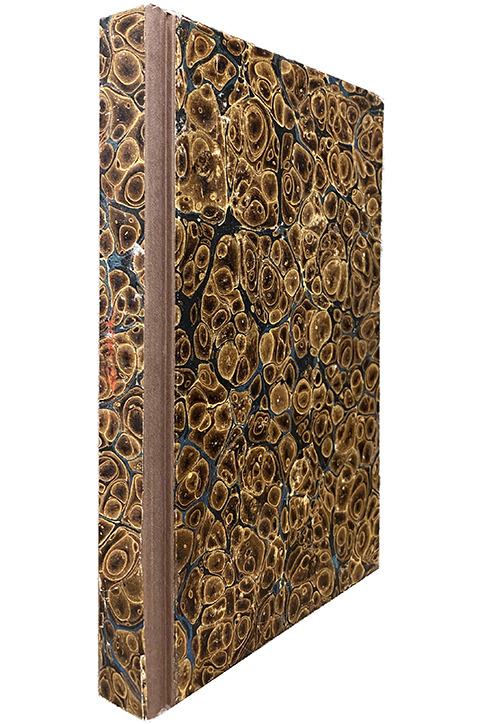

LOUIS, ANTOINE (1723-1792). Dissertation sur la question--comment se fait la transmission des maladies héréditaires? [Dissertation on the question--how are hereditary diseases transmitted?] and Observation et remarques sur les effets du virus cancéreux [Observation and remarks on the effects of the cancer virus], Printed in Paris at Chez Delaguette, 1749. 17 cm tall.

This month we highlight a book (but two works!) by the 18th-century French surgeon, Antoine Louis, who helped change the perception of surgeons in the medical community. We touch on his works on hereditary diseases and cancer, his little-known connection to the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror, and his role in helping to create the modern surgical profession.

Louis was born to a military surgeon family. His father was a surgeon-major, the senior surgeon of a regiment, at a military hospital. Louis apprenticed under his father and by 1743 had joined another regiment as a surgeon himself. He soon went to Paris, though, to further his education at the Salpêtrière hospital, which you may remember from such JMRBR newsletters as "Volume 2, Issue 4." In 1750 he was appointed professor of physiology, holding that position for 40 years.

Louis was at the head of a movement to push back against the negative perception of surgeons driven by physicians. He wrote often, and effectively, to argue for equal status for surgeons. For centuries surgeons were thought of by physicians as, at best, less educated technicians and, at worst, uneducated boors who would cut anything for money.

Although eventually a separate discipline with its own schools, societies, and formal training, surgery in Europe had its roots in the barber-surgeon tradition. Often employed in the military, barber-surgeons used their tools for surgical and dental procedures as well as for cutting hair.

The 16th-century predecessor of Louis, Ambroise Paré, helped lay the groundwork for the modern evolution of surgery into a medical specialty. He challenged surgical dogma at the time and wrote many works, always in French as he did not know Latin, describing his new techniques and inventions.

Scottish surgeon John Hunter, a contemporary of Louis, established the empirical foundations of modern surgery. Echoing a common theme among early modern medical pioneers, he rejected the status quo and sought to understand surgical knowledge from the ground up. He based his conclusions on his own observations, experiences, and experiments. With his skill as both an experimentalist and writer, Hunter nearly singlehandedly set surgery on the path to its modern place in medicine.

By the 19th century, barber-surgeons ceased to exist and surgeons were well-trained doctors who chose surgery as a specialization.

Louis was not afraid to put his money where his mouth was. Upon the completion of his stint at Salpêtrière, he could have slid right into a position at the college of Surgery, but instead, he wrote and publicly defended his thesis, Positiones anatomicae et chirurgicae(1749). Both of which he accomplished in Latin, thereby demonstrating that surgeons were as liberally educated as their physician colleagues.

While also performing surgeries, writing, and maintaining a busy administrative calendar, Louis found time to invent and improve surgical instruments. His renown eventually led to an association with the most infamous period in French history. A physician opposed to capital punishment petitioned the National Assembly (formed shortly after the French Revolution) to advocate for a more "humane" way to execute criminals.

This would be accomplished by using a machine designed to quickly decapitate them. The Assembly eventually petitioned Louis to design and build it. Originally referred to as the Louisette, it eventually adopted the name synonymous with the Reign of Terror - the Guillotine, named after the physician who originally proposed its use, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin.

Louis wrote and published throughout his life, including several biographies of other surgeons, Encyclopédie entries, and pioneering works on medical jurisprudence. Two boxes of unpublished works were found while cataloging his belongings after his death. The books highlighted here are two of his earlier publications. Observation et remarques sur les effets du virus cancéreux is an interesting piece on cancerous growths and remedies, in which Louis refers to cancer as a virus. We now know of several viruses that can lead to cancer.

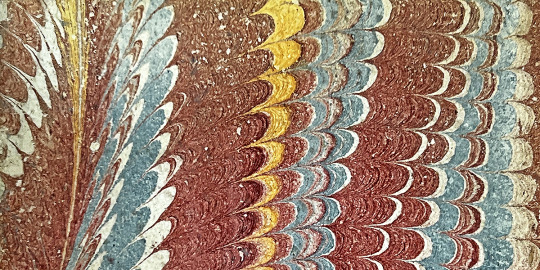

Our copy is an adorable little book with beautiful marbled endpapers, a closeup of which you can see above. The contemporary sheepskin cover shows that the book has lived a busy life. It is a deep, rich brown color with several gilt flowers along the spine. The paper is in excellent condition, showing few signs of age or damage.

#medical history#medicine#surgical#french revolution#university of iowa#rare books#jmrbr#hardin library#libraries#antoine louis

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest post from John Martin Rare Book Room

At UIowa's Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

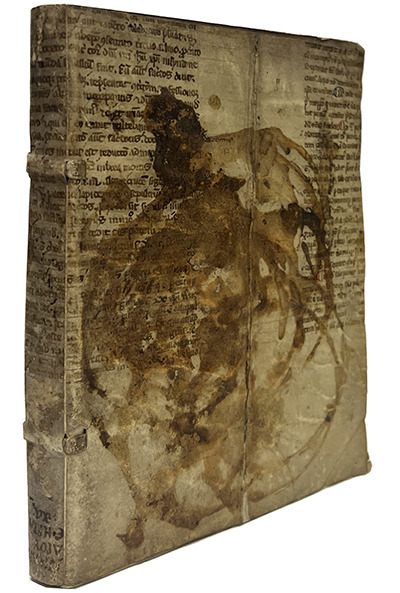

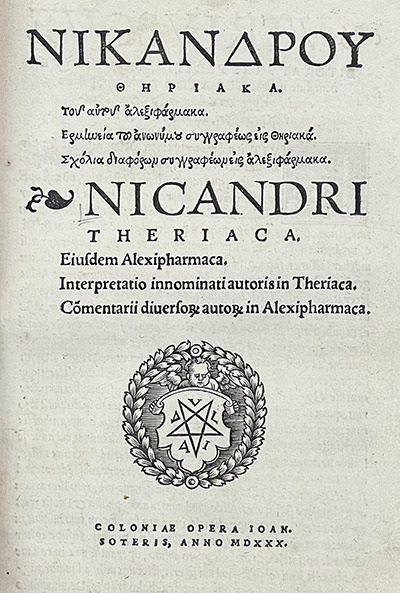

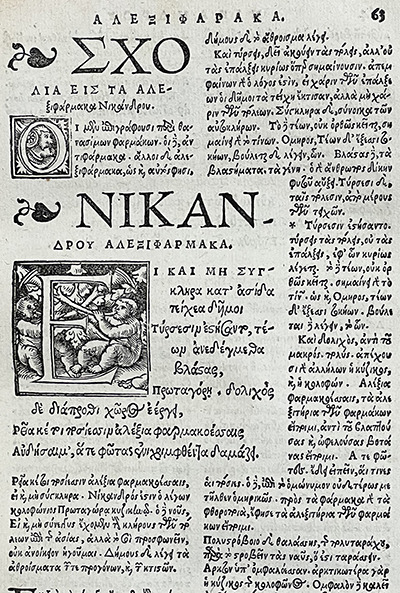

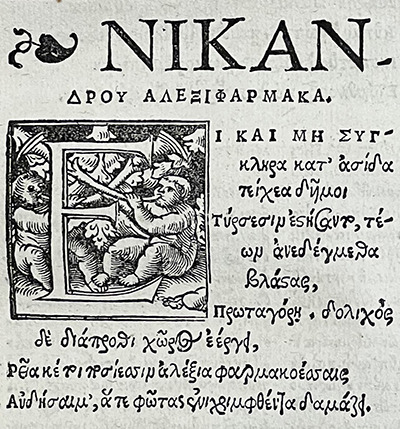

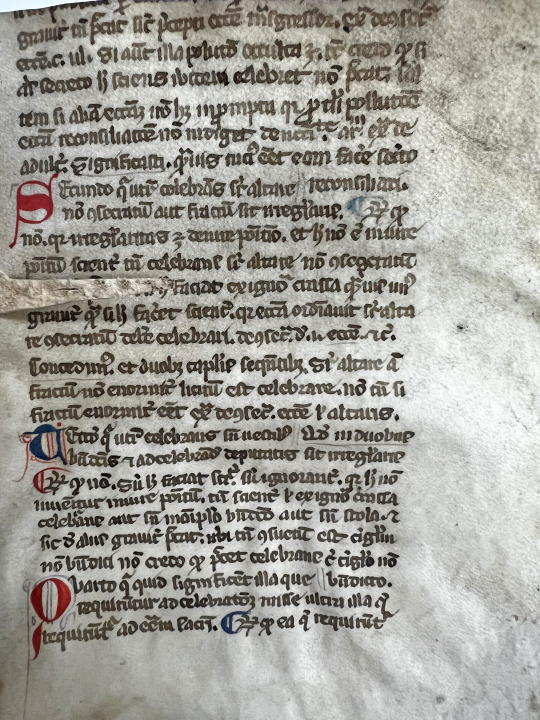

NICANDER OF COLOPHON (flourished 138-130 BCE) Theriaka; Tou autou Alexipharmaka [Greek title transliterated]. Theriaca; Eiusdem Alexipharmaca. Printed by John Soteris in 1530. 21 cm tall.

April is National Poetry Month, so we are highlighting the classic works of Nicander of Colophon. Nicander was a physician poet from the 2nd century BCE. We know he wrote many different works, but only two complete examples have survived.

The two works, Theriaca and Alexipharmaca, deal with poisons and venoms. Poems like these were thought to make scientific content and concepts easier to understand and remember. Nicander, though, was more interested in form and style, not necessarily accuracy. Indeed, his poems can be difficult to read and he did not seem to have much knowledge at all of toxicology. As Gow and Scholfield note in their Poems and poetical fragments, "his contorted style and fantastic vocabulary put him beyond the reach of scientists unless they are also Greek scholars. . ." (p. xi).

Nicander was born and raised in Clarus in western Asia Minor (near the larger Colophon, in what is now Western Turkey) during the reigns of the last kings of the Attalid Dynasty of Pergamon. Clarus was home to a large temple devoted to Apollo and there are several references to Nicander's family as priests in the cult, including perhaps Nicander himself.

The longest of the hexameter poems, Theriaca, covers venomous animals. Nicander describes the animals, the symptoms associated with a bite or sting, and pharmacological recipes for treating them. The Alexipharmaca covers poisons that have been ingested orally from animals, plants, or minerals and their antidotes. Much like Theriaca, Nicander breaks the entries into a description of the poison, the symptoms, and recipes for antidotes. Nicander is also thought to be the first to suggest the use of leeches in a medicinal context, although many scholars believe he borrowed heavily from the Greek-Egyptian physician Apollodorus (fl. 250 BCE).

The first known print copies of the poems are in the 1499 edition of Dioscorides' De materia medica. The poems are also bound together in this item with the first Latin translation made by Johann Lonitzer (1499-1569). Lonitzer was a classical languages scholar, poet, and professor at Marburg in Germany. As can be seen from the image above, the cover of the book is cut from a piece of vellum manuscript waste (parchment from an older, handwritten work used in the binding of another book). It is heavily stained with ink spilled from an inkpot (tip of the hat to Collections Conservator Beth Stone for identifying the stain). Perhaps an apprentice or student faced the wrath of their instructor for using the book as a stand for their ink?

It also appears the cover was given conservation treatment at some point before we acquired it. As part of this treatment, the cover was removed. However, when it was reattached, the covers were reversed! Thus, the spine title is now upside down and the ink stains on the front actually originated on the back. Another example of all the amazing stories our books have to tell us beyond what is written on the page. Other than the mistreatment at the hands of the nameless, ink-spilling writer/illustrator, the book is in great condition. And other than some minor staining in the back (ink that bled through from the spill on the cover) and on the edges, the paper is especially in good shape. If you stop by the open house tonight, you'll have a chance to take a look for yourself.

--Damien Ihrig, Curator of the John Martin Rare Book Room

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

At the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

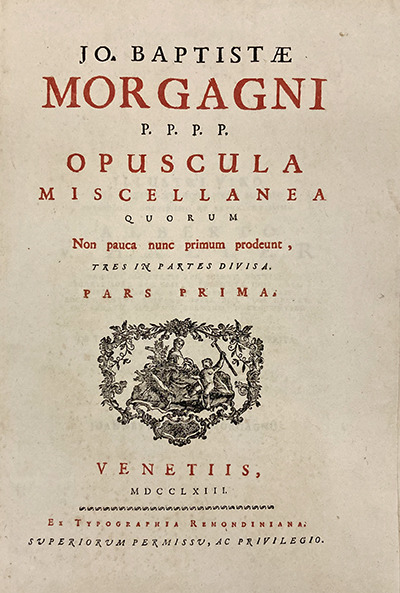

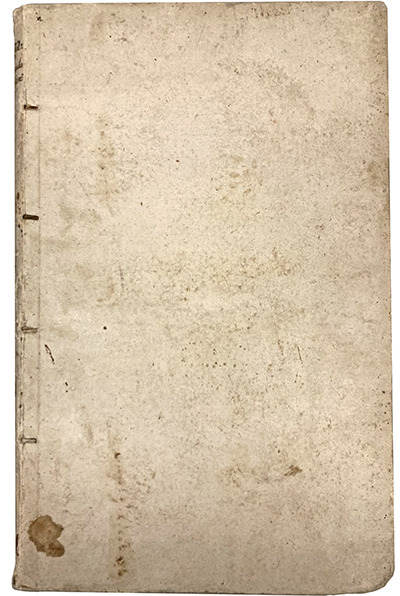

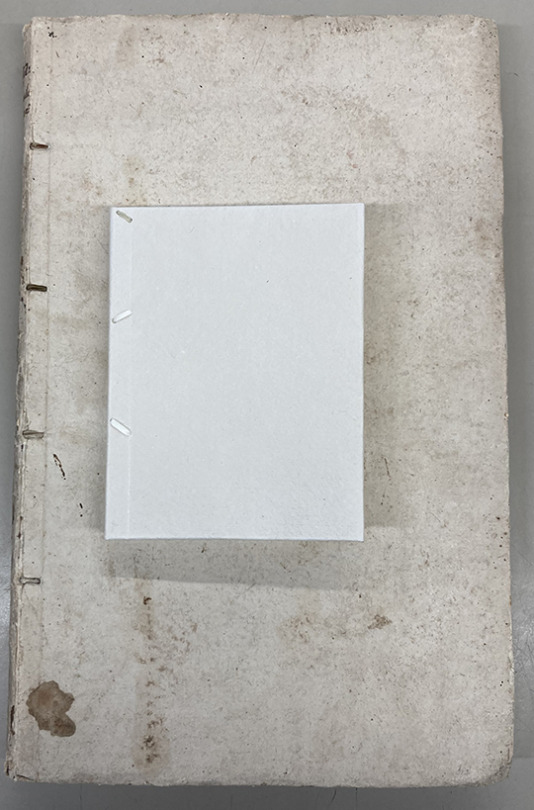

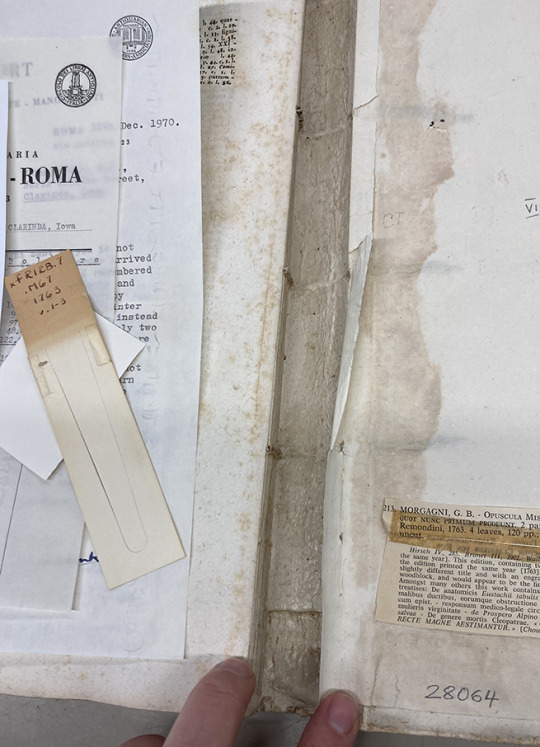

MORGAGNI, GIOVANNI BATTISTA (1682-1771). Opuscula miscellanea quorum non pauca nunc primum prodeunt, tres in partes divisa [Miscellaneous works, some of which are new, divided into three parts]. Printed by Giovanni Antonio Remondini at Remondiniana, Bassano del Grappa, 1763. Three volumes bound together. 39 cm tall.

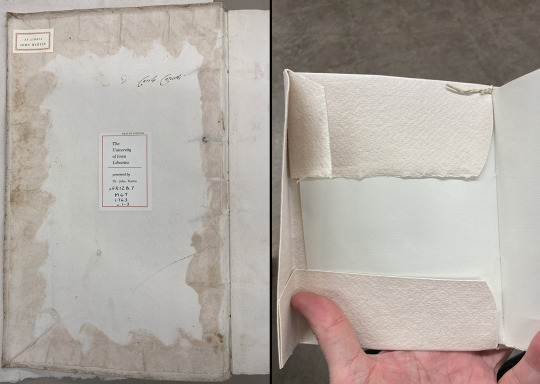

This month we highlight a book currently receiving treatment from the UI Libraries Conservation and Collections Care. Collections Conservator, Beth Stone, is working to clean and stabilize one of our books from Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771).

Morgagni was an 18th-century Italian anatomist and physician. He is referred to as the "father" of modern pathologic anatomy. He stressed connecting the symptoms observed in the sick to the findings from their dissection. Symptoms, he felt, were "the cry of the suffering organs." His work helped dispel the longstanding notion that most diseases were scattered throughout the body. Instead, he was able to demonstrate that they emerge from specific organs and tissues.

During his very long life, Morgagni was a prodigious worker and prolific writer. His three-volume Adversaria Anatomica (1706-1717) put him on the map. His most monumental work, De sedibus, et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis libri quinque, was published in 1761 and made him a legend among anatomists. Vast in scope, it is one of the most fundamentally important works in the history of medicine.

The book this month, however, is Morgagni's Opuscula miscellanea quorum non pauca nunc primum prodeunt, tres in partes divisa [Miscellaneous works, some of which are new, divided into three parts]. As stated in the title, this is a collection of writings on a variety of subjects, including letters to Giovanni Lancisi, an Italian physician, discussing how Cleopatra died.

Morgagni's scholarly ability was apparent at an early age. At sixteen he was a pupil of Antonio Maria Valsalva at Bologna, and there he received the stimulus to devote his life to pathology. While pursuing postgraduate studies, he worked with Giovanni Santorini performing dissections. (Giovanni was clearly a very popular name at this time!)

By 1715 he took the chair of anatomy at Padua, a seat which he held with utmost distinction for many years. He was a brilliant and tireless investigator and, in addition to his work in medicine and anatomy, was a student of the classics and an archaeologist of repute.

Over his long career at the University of Padua, he taught thousands of students from dozens of countries. His teaching emphasized empirical data, direct observation, and experimentation.

Among several other structures, his name is most widely connected with the "Columns of Morgagni," the fine, vertical folds of the anal canal.

As mentioned, if he was not teaching or dissecting, Morgagni was writing. Opuscula miscellanea shows his range and diverse interests. Along with discussing Cleopatra's cause of death, it includes a biography of his mentor, Valsalva, a tract on gallstones, and a few more on legal issues.

Opuscula miscellanea has a lovely, soft paper cover. The cover shows the effects of age, use, and exposure to the environment, with scuffs, stains, and an overall darkening. Do not let that fool you, though, as this is still an effective binding. With a new housing from Conservation, Opuscula miscellanea will be around for a very long time.

Go here to read about Beth’s treatment for Opuscula miscellanea and more.

The annual JMRBR open house is April 20, from 4-7 pm. This is our first in-person event in quite some time and we'd love to see you there!

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Located at Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

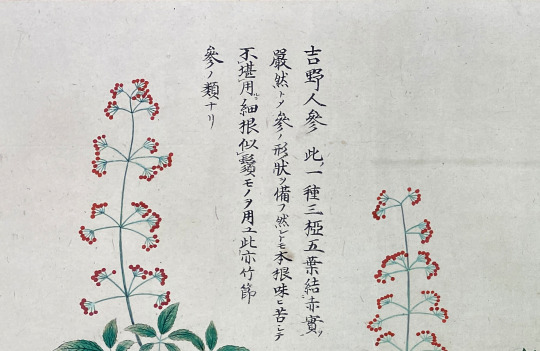

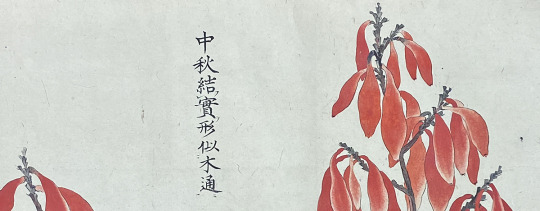

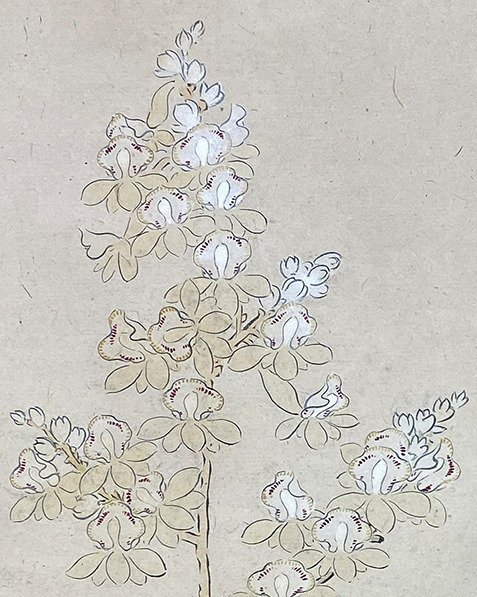

UNKNOWN. Medicinal plants scroll from Japan's mid-Edo period. Estimated date of creation is between 1727 and 1800. 29 x 800 cm.

This book blends all of the things that make working with our collection so rewarding: the paper, how it feels, the artistry, how it smells, the printing, construction, content, and evidence of the life it has lived. Simply known as the Medicinal plants scroll, it is an 8-meter scroll from Japan's Edo period (1603-1867) containing beautiful hand-painted illustrations.

Japanese hand-scrolls, or emakimono, are not meant to be read or displayed completely unfurled. Rather, each panel should be read, one at a time, starting at the right and reading to the left. The right hand works in concert with the left to roll up the scroll at the same time as a new panel is exposed. This is considered especially important for narrative scrolls, such as the famous Tale of Genji.

Emakimono, distinguished from hanging vertical scrolls, or kakemono, are a form of communication almost as old as the Japanese written language. Starting with characters imported from China in the 5th century, the Japanese written language has evolved substantially since then. The use of Chinese characters, however, lasted for centuries. In fact, many of the Japanese books in the Rare Book Room collection use Chinese characters, including the Medicinal plants scroll.

The Medicinal plants scroll is, as its name suggests, a catalog of native Japanese plants, describing their habitats, flowers, fruits, and medicinal uses. Each brief description is accompanied by a hand-painted illustration of the plant, usually in bloom. Thanks to the generosity and hard work of our colleague, Tsuyoshi Harada, our Japanese Studies Librarian, we have a detailed translation of the scroll.

Due to his efforts, we have identified each plant, including Cyrtosia septentrionalis in the image in the introduction, also called Yamashakujo or Tuchiakebi, and Panax japonicus, or Japanese Ginseng, seen here. Unlike traditional ginseng, this guide recommends avoiding the very bitter root of P. japonicus and instead using the root hairs.

The scroll also includes references to other medicinal plant resources available at the time. We are excited to see if we can locate any of these as well.

The scroll is in excellent condition. There is very minor staining here and there, but the original paper is otherwise spotless. It has been rebacked fairly recently with a modern paper containing gold flecks. Replacing the paper support on the back as the scroll ages is a customary practice. Emakimono are not made from a continuous roll of paper, but rather equally sized sheets that have been cleverly glued together, combining long fibers that extend out each side of the sheets. The layers of backing paper then add support and durability.

--Damien Ihrig, curator

#Japanese#herbal#jmrbr#hardin#uiowa#japanese art#special collections#libraries#rare books#scroll#medicine

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest post from John Martin Rare Book Room!

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

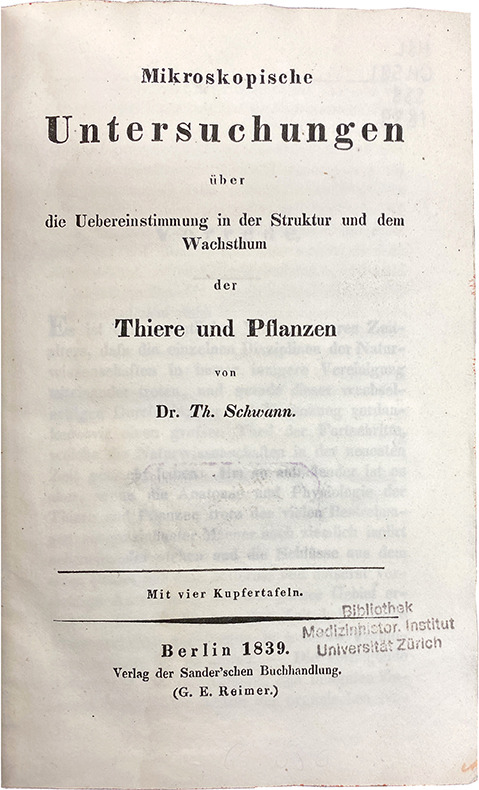

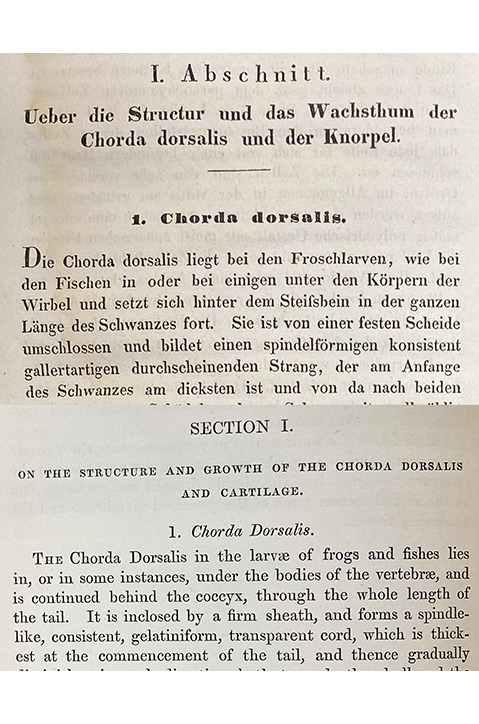

THEODOR SCHWANN (1810-1882). Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Uebereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsthum der Thiere und Pflanzen. [Microscopical researches into the accordance in the structure and growth of animals and plants] Printed by Georg Reimer in Berlin in 1839. First edition. 270 pages. 21 cm tall.

Schwann was an energetic and talented researcher, inventor, and teacher. He is recognized for many contributions to medical science. Easily his greatest contribution, though, is this foundational work on extending cell theory to animals. Working for his mentor, Johannes Peter Müller, in 1837 the 27-year-old Schwann was using the most powerful microscopes of the day to examine and describe various types of animal cells.

In one of those wonderful moments of scientific serendipity, he happened to be dining with his close friend the botanist, Matthias Jakob Schleiden, when they began to discuss plant cell nuclei. Schwann quickly realized he had seen similar structures in animal cells and that animal cells must function similarly to plant cells: as foundational structures for all living things. Schwann and Schleiden worked together to confirm this. Schwann extended the research with several more experiments on a variety of animal tissues, eventually publishing Mikroskopische in 1939.

By the middle of the 19th century, his two main conclusions, that cells are distinct, but function as the foundational, organizational structures for all living things, became the accepted description for the basic structural components of life. His third conclusion about the formation of cells was not supported by further experimental evidence and was eventually discarded. Regardless, Schwann's work created the foundation upon which rested the important discoveries of the next century in biology and the medical sciences.

If your German is a little rusty, you are in luck! We also have an English translation by Henry Smith from 1847. If you are interested in seeing these or other items mentioned in earlier newsletters, please contact Damien Ihrig at [email protected] or 319-335-9154 to arrange a visit in person or over Zoom.

#history of medicine#theodor schwann#cell biology#science#hardin medical library#jmrbr#rare books#german

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

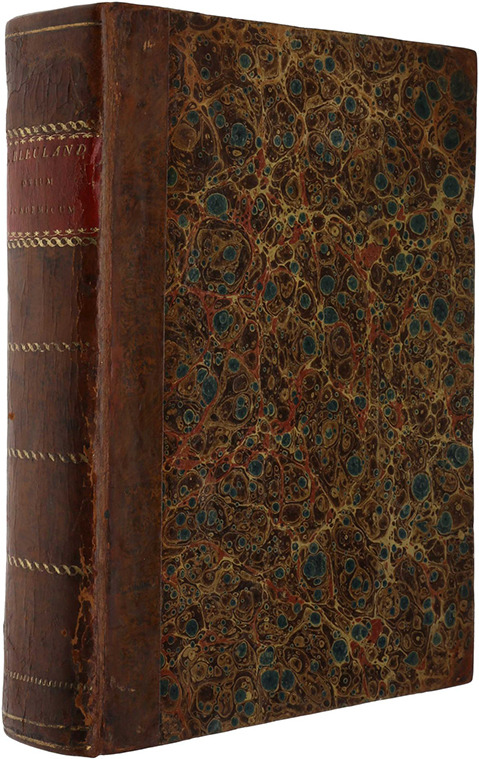

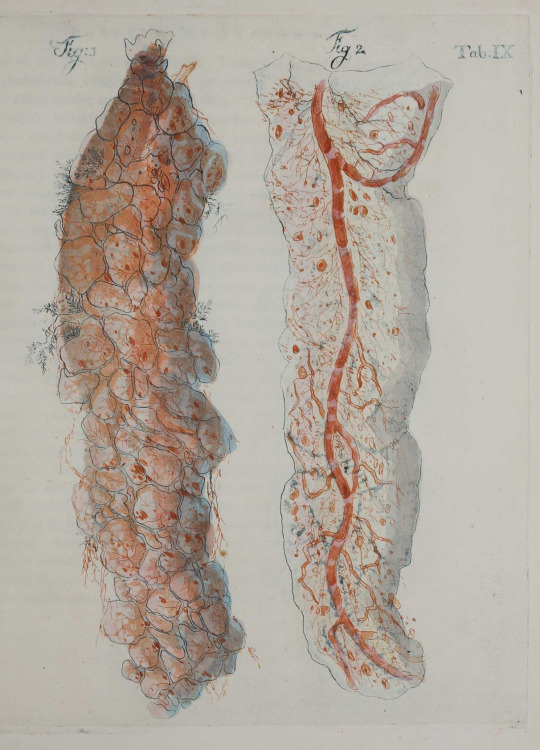

Today we present a book from the Dutch physician Jan Bleuland (1756–1838), filled with beautiful anatomical and pathological illustrations.

Bleuland trained at Leiden University under the tutelage of the anatomist, Eduard Sandifort. There he honed his skills injecting anatomical specimens and working with the large anatomical collection of the university. After graduating with his doctor of medicine, he eventually made his way to Utrecht, where he taught anatomy, physiology, surgery, and obstetrics.

Over his career, Bleuland built his own collection to over 2,500 mostly human specimens. He used his collection for his teaching and research and to publish several works, including another book in our collection, Observationes anatomico-medicae de sana et morbosa oseophagi structura. Observationes deals with the anatomy of the esophagus in the infant and adult, its specific functions, and pathological conditions.

In 1826, Bleuland retired and the Dutch government bought his collection for the Utrecht University Museum. He quickly produced an inventory of the collection, Descriptio musei anatomici (1826), and began to create his greatest work, an illustrated catalog of the collection. We were fortunate enough to find a copy of this catalog, and we are excited to present it to you.

--Curator of JMRBR, Damien Ihrig

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest post from the John Martin Rare Book Room

Located at the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

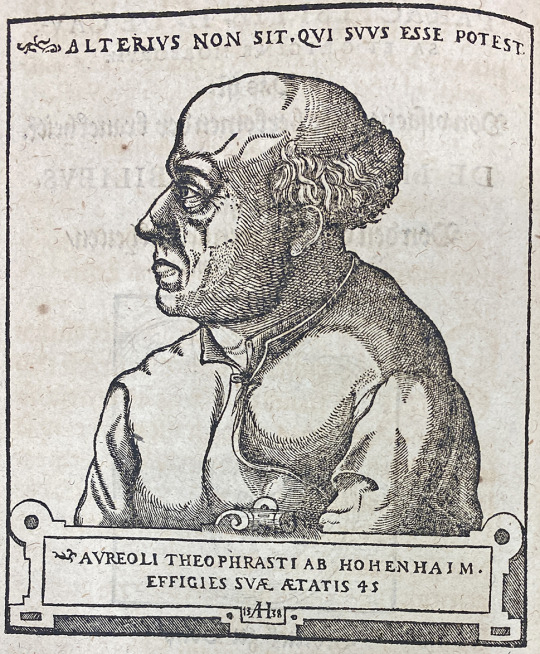

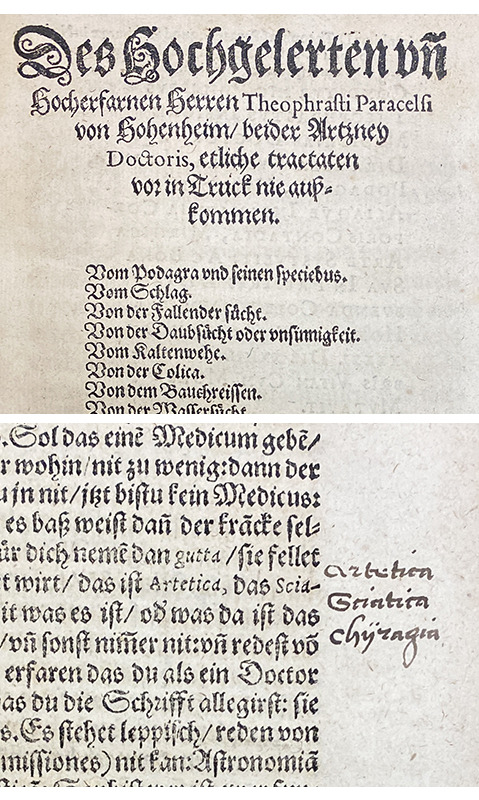

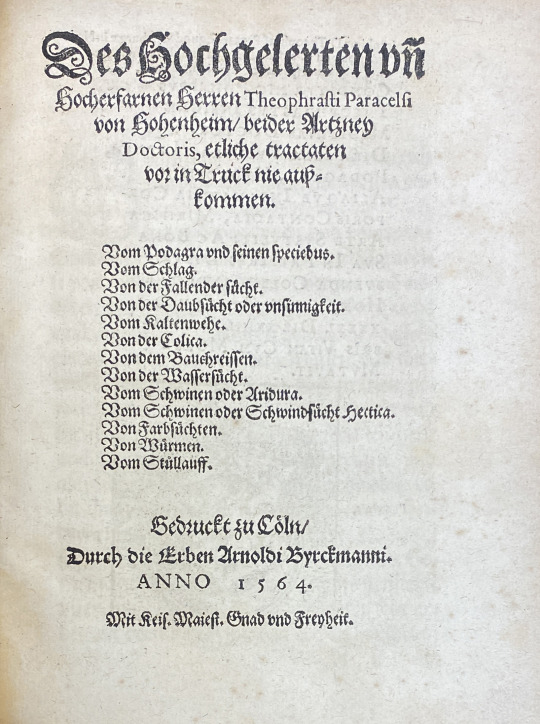

PARACELSUS (ca. 1493-1541). Des hochgelerten vn[d] hocherfarnen Herren Theophrasti Paracelsi von Hohenheim, beider Artzney Doctoris, etliche Tractaten vor in Truck nie ausskommen. [From the highly educated and high ranking Theophrastus Paracelsus of Hohenheim, doctor of both medicines, a number of never before seen tracts] Printed by Arnold Birckmann's print shop (the "Heirs of Arnold Birckmann") in Cologne in 1564. First edition. 167 pages. 20 cm tall.

Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim is universally known as Paracelsus, a name given to him by others who saw him as a genius "surpassing Celsus" (a 2nd-Century Greek philosopher). He was born in Switzerland in 1493 and educated at Basel, a center of Renaissance humanism. There, he was eventually appointed town physician and professor at the University of Basel. His unorthodox ideas and teachings, though (and perhaps his heavy drinking and impatience with those in power), put him in conflict with the orthodox establishment of his time and Paracelsus spent most of his life wandering through Europe as an itinerant physician, chemist, theologian, and philosopher.

Paracelsus was a creative medical visionary during the Renaissance. Like many of his scientific and medical contemporaries, he stressed the value of observation when describing the structures and functions of life. Credited as the "father of toxicology," he described the modern concept of "dose-response" in his Third Defense. Here he stated that "Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison.". In other words, everything is poison if you get too much of it.

This targeted approach to administering medicines was counter to the prevalent strategy of applying cure-alls. This is due, in part, to his rejection of the classic "balancing of the humors" approach to healing, and his insistence that illnesses have an environmental component. Among other things, Paracelsus is also credited for coining the terms "gas," "alcohol," and "chemistry".

Although his ideas were heavily influenced by concepts that we would now consider quackery, many of Paracelsus's ideas in medicine were ahead of their time. He was a prolific writer, but few of his works were published during his lifetime. After his death, though, his works became very popular and were printed for decades afterward. Check out our newest addition to our Paracelsus collection below!

This brief biography only scratches the surface of the remarkable life of Paracelsus. Please find more extensive biographies at the National Library of Medicine History of Medicine Division and through PubMed.

Etliche Tractaten...is a collection of thirteen of the most important medical tracts by Paracelsus on various diseases and their treatments. They include one of the author's most thorough discussions of gout. Paracelsus was the first to suggest the possibility of a chemical as opposed to humoral causation of gout. It also includes an important contribution to his theories regarding the treatment of epilepsy, and descriptions of colic, rheumatism, dropsy, mental illness, consumption, shock, edema, vertigo, helminths (parasitic worms), and tuberculosis.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

At Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

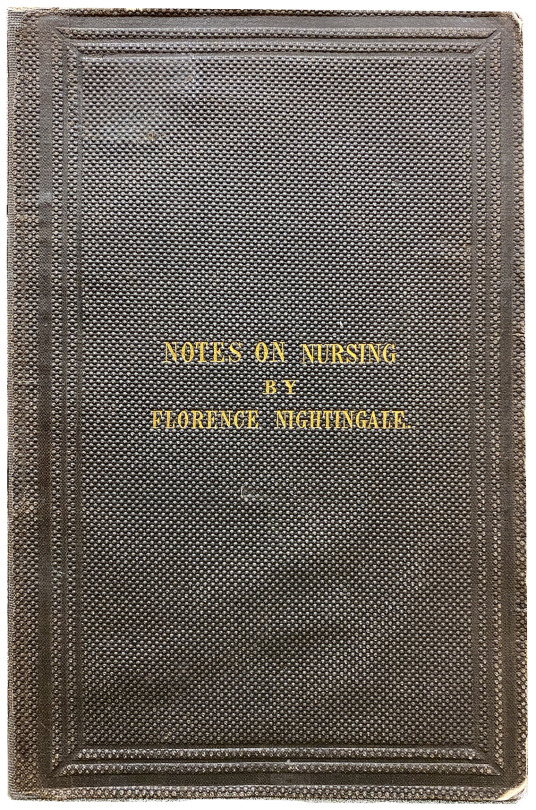

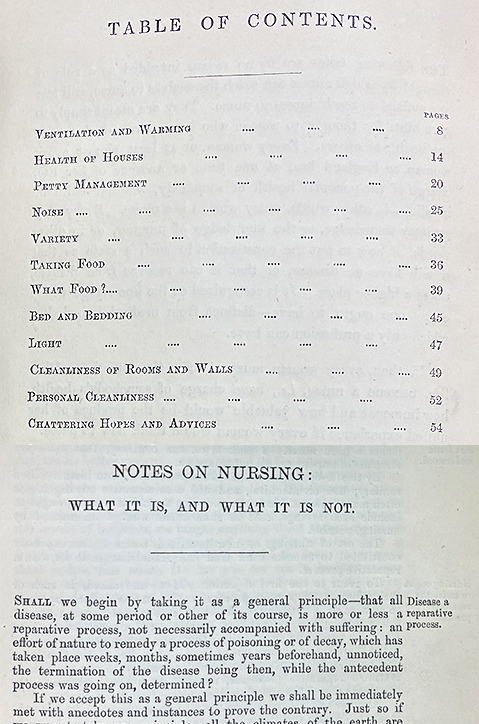

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE (1820-1910). Notes on nursing: what it is, and what it is not. Printed by Harrison in 1860. This is the second issue of the first edition. 79 pages. 21.6 cm tall.

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820, to a wealthy, aristocratic British family. She was known for her smarts and humor, translating classic works and excelling at math and statistics. She was keen on helping others and saw nursing, a fairly disreputable career at the time, as her opportunity to do so. She was trained in France, Germany, and Egypt, and after nursing experience in England, in 1854 she was asked to take charge of a group of nurses being dispatched to the Crimea to care for the British wounded in the war. Her heroic efforts brought the mortality rate among the soldiers from 42 percent to 2 percent.

The rest of her life was spent in the struggle to improve the care of patients and to establish nursing as a profession. This no-nonsense book is not only a call for the establishment of training of nurses; it offers practical advice on the care of patients. Nursing, she says in Notes..., "has been limited to signify little more than the administration of medicines and the application of poultices. It ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet."

Although this book is undated and its publication is often ascribed to 1859, it was probably not actually available to the public until 1860. The present issue is sometimes called the first issue, but as a few copies exist in which no advertisements appear on the endpapers and in which a statement concerning translation rights (carried in later issues on the title page) does not appear, this must be accorded place as the second issue, before correction of several typographical errors in the text.

The book itself is unassuming, created during a time of transition from high quality to lower quality papers. Of the two 1860 books we have, one is in good shape. The brown, stamped cloth covers remain mostly intact and the paper, although yellowed slightly, is in excellent condition. The second book has seen a lot of wear and tear and will eventually need conservation work to reattach the covers and a few pages. There are no illustrations, but there are some fun advertisements for other Harrison printed books used as endpapers. In addition, one of the books has a small engraving of Lea Hurst, Nightingale's home, that someone pasted in the front at some point in the life of the book.

We have other works by NIghtingale and many others on the topic of nursing. If you are interested in seeing these or other items mentioned in this or earlier newsletters, please contact Damien Ihrig at [email protected] to arrange a visit in person or over Zoom.

--Damien Ihrig, Curator of the John Martin Rare Book Room

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Library for Health Sciences, University of Iowa

Periodically, Hardin and the JMRBR receive gifts of books from our patrons. One such patron was Dr. Walter Bierring. Those familiar with the history of Iowa medicine will no doubt know his name. Referred to as "Iowa's Osler," he graduated from the University of Iowa with his MD in 1892, became a leading figure in the state and beyond for bacteriology, held several leadership positions at the UI medical school, and was a leader in statewide public health until his death in 1961.

The books detailed in the Conservation Corner by Assistant Conservator, Beth Stone, are two of the books donated by Dr. Bierring, and they are good examples of the kinds of mysteries found in the stacks of a rare book room.

Today we look at Robert Pitt’s (1653–1713) book The craft and frauds of physick expos'd : the very low prices of the best medicines discover'd, the costly preparations now in greatest esteem condemn'd, and the too frequent use of physick prov'd destructive to health : with instructions to prevent being cheated and destroy'd by the prevailing practice, which was printed in 1702.

During the seventeenth century, the Society of Apothecaries gained great wealth and esteem throughout England, and in many instances, its members were also practicing medicine nearly full-time. This practice ultimately led to open conflict with the physicians, and the situation was not resolved for more than a century. At the time this book was written, the quarrel centered on the opening of dispensaries by members of the College of Physicians and the prosecution of apothecaries practicing medicine. Both sides wrote many pamphlets and books, and this work by Pitt, an anatomist at Oxford and physician to St. Bartholomew's, London, is a direct attack on the apothecaries in which he defends the dispensaries and criticizes the practices of the apothecaries.

For more on Robert Pitt, please visit the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

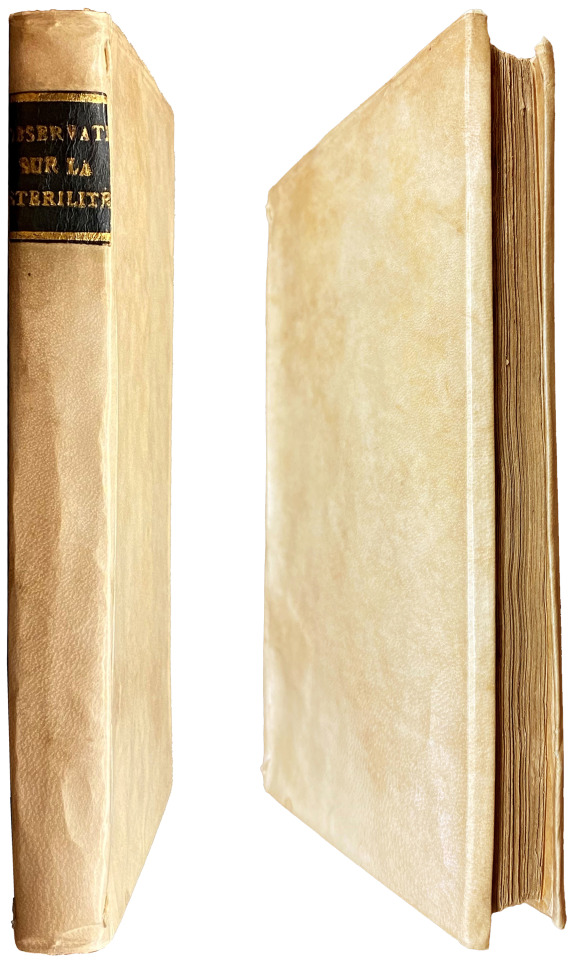

Obseruations diuerses sur la sterilité, perte de fruict, fœcondité, accouchements, et maladies des femmes, et enfants nouueaux naiz / amplement traictees et heureusement praticquees par L. Bourgeois, dite Boursier, sage femme de la Roine; œuure vtil et necessaire a toutes personnes.

This book is a first edition of the first book on obstetrics published by a midwife. Louise Boursier was a scientist, practitioner, teacher, and author. She was a woman of many firsts. She was one of the first women to be trained at the school for midwives which was opened at the Hôtel Dieu. She was the midwife who attended Marie de Medici, the wife of Henri IV (Henry the Great of France), at the births of her six children. She was the "sworn midwife" to the city of Paris, and in 1601 she officiated at the birth of the dauphin, later to be King Louis XIII of France. She was one of the pioneers of scientific midwifery, and her Observations was the go-to pocket book of contemporary midwives.

Between 1609 and 1652, she wrote many books, mostly expanded volumes of this first edition. Among other techniques, she introduced premature labor in patients with a contracted pelvis or uterine hemorrhage. Her work set the stage for the training and practice of future midwives in many countries, including her own descendants.

The binding for Observations is vellum pasted over thin boards. The book cover is also a nice example of yapp edges. An abbreviated spine title has been gold stamped on a black strip of leather overlayed onto the vellum. There are three engraved illustrations in the book, the title page, and portraits of Louise Boursier (above) and her patron, Marie de Medici. Her cap, collar, and cross help identify Louise as a royal midwife.

Book: LOUISE BOURGEOIS BOURSIER [also known as Louise Bourgeoise] (1563-1636) Obseruations diuerses sur la sterilité, perte de fruict, fœcondité, accouchements, et maladies des femmes, et enfants nouueaux naiz / amplement traictees et heureusement praticquees par L. Bourgeois, dite Boursier, sage femme de la Roine; œuure vtil et necessaire a toutes personnes. [Diverse Observations on Sterility, Miscarriage, Fertility, Childbirth, and Diseases of Women and Newborn Children. Discussed in Detail and Successfully Practiced by L. Bourgeois, called Boursier, Midwife to the Queen. A Work Useful and Necessary for All]. Printed by Chez A. Saugrain in 1609.

#Louise Bourgeois Boursier#midwifery#medicine#medical history#rare books#jmrbr#Hardin Library#books#university of iowa

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guest Post from the John Martin Rare Book Room

Hardin Medical Library, University of Iowa

Periodically, Hardin and the JMRBR receive gifts of books from our patrons. One such patron was Dr. Walter Bierring. Those familiar with the history of Iowa medicine will no doubt know his name. Referred to as "Iowa's Osler," he graduated from the University of Iowa with his MD in 1892, became a leading figure in the state and beyond for bacteriology, held several leadership positions at the UI medical school, and was a leader in statewide public health until his death in 1961.

The books detailed in the Conservation Corner by Assistant Conservator, Beth Stone, are two of the books donated by Dr. Bierring, and they are good examples of the kinds of mysteries found in the stacks of a rare book room.

Today we look at Alexander Monro’s (1697-1767) book, Anatomy of the human bones, nerves, and lacteal sac and duct.

Monro's Anatomy received wide acclaim and remained in print well into the early 19th Century. Beginning with the second edition, all editions included Monro's separate treatises on the nerves and lacteal sac.

Founder of the Edinburgh medical school, Monro is the first of three generations of physicians with the same name. In 1719 he was admitted to the Incorporation of Surgeons in Edinburgh. He lectured on anatomy at the appointment of the Town Council and was eventually granted his own place at the University.

Monro primus, as he is usually called, was the first in the long line of the Monro family who held the Chair of Anatomy at Edinburgh uninterruptedly for more than 120 years (along with his son (secundus), and his grandson (tertius). During the tenures of the Monros primus and secundus, the University of Edinburgh became a great center of medical teaching. Monro primus was a disciple of Boerhaave and William Cheselden, and his own teaching attracted hundreds of medical students. For more on the Monros, please visit the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

Our edition is printed for G. Hamilton and J. Balfour, 1763. 7th edition. 410 pages. 16.8 cm tall.

--Damien Ihrig, Curator at John Martin Rare Book Room

#JMRBR#medicaltext#history of medicine#Alexander Monro#anatomy#conservation#rare books#university of iowa#hardin library

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Guest Post from John Martin Rare Book Room

Untersuchungen über thierische Elektricität [Investigations into Animal Electricity]

Du Bois-Reymond, considered by many authorities to be the founder of modern electrophysiology, was a pioneer in the study of electrical impulses in nerve and muscle fibers. Born in Berlin, he studied there at the Collège Français, later at Neuchâtel in Switzerland, and finally entered the University of Berlin in 1836.After completing the requirements for a degree in medicine, Du Bois-Reymond accepted an assistantship with Johannes Müller who directed his interest to the study of electrophysiological problems. Proper instrumentation for the research he wished to conduct was lacking so Du Bois-Reymond developed new instruments and applied scientific methods to the study of animal electricity. He was the first to prove that muscular activity is accompanied by chemical changes in the muscle as well as by changes in its electromotive properties. In 1843 he demonstrated the phenomenon of electrotonus which refers to the potential changes produced by an externally applied current. He also discovered the resting nerve current and the difference in electric potential between the cut and uninjured ends of an excised muscle or nerve. He was an accomplished author and wrote many philosophical essays and biographical studies in addition to his numerous physiological studies.

Untersuchungen über thierische Elektricität is Du Bois-Reymond's major work and contains the body of his physiological studies and research. The first volume appeared in 1848 and the first part of the second volume in 1849. The second volume was not completed until 1884 after additional years of research and experimentation. Because of the long intervals between the publication of the individual volumes, complete sets of the work are very rare. This set contains thirteen plates of illustrations instead of the usual twelve because one of the plates in Volume I is duplicated in Part I of Volume II. The set was bound at some point in gray paper over paper boards, with a bright, half red Morocco leather and gold stamped spine titles. The books are also unique because they include the original "wrappers" describing the contents of the unbound manuscripts. And because many of the pages in all three books are "unopened." This means adjacent pages have not been separated and cannot be fully opened. This is due to a method of printing and binding where a larger sheet of paper is printed with several pages of text, folded, and bound. It makes for difficult reading, but is fun to see!

Du Bois-Reymond, Emil Heinrich (1818-1896). Untersuchungen über thierische Elektricität. [Investigations into Animal Electricity] Printed by Georg Reimer from 1848-1884. Volume I: 743 pages with 6 folded, black and white plates; Volume II, Part I: 608 pages with 5 folded, black and white plates; Volume II, Part II: 579 pages with 2 folded, black and white plates. 23.7 cm.

#De Bois-Reymond#electricty#medicine#medical history#rare books#jmrbr#Hardin Library#university of iowa#books

34 notes

·

View notes