#Fulfillment by Amazon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How Amazon transformed the EU into a planned economy

Amazon is a perfect parable of enshittification, the process by which platforms first offer subsidies to end users until they’re locked in, then make life good for business customers at users’ expense, until they’re locked in, then claw back all the value they can for themselves, leaving just enough behind to keep the lock-in going.

In a new report for SOMO, Margarida Silva describes how the end-stage enshittification of Amazon is playing out in the EU, with Amazon repeating its US playbook of gouging the small businesses who have no choice but to use the platform in order to reach its locked-in customers, making European customers and European sellers poorer:

https://www.somo.nl/amazons-european-chokehold/

The mechanism for this isn’t a mystery. Amazon boasts about it! They call it their flywheel: first, customers are lured into the platform with low prices, especially through Prime, which requires pre-payment for a year’s shipping, which virtually guarantees that customers will start their shopping on Amazon. Because customers now start their buying on Amazon, sellers have to be there. The increased range of goods for sale on Amazon lures in more buyers, who lure in more sellers, with both sides holding each other hostage:

https://vimeo.com/739486256/00a0a7379a

This flywheel creates a vicious cycle, starving local retail so that customers can’t get what they need from brick-and-mortar shops, which funnels sellers into offering their goods for sale on Amazon. The less choice customers and sellers have about where they shop, the more Amazon can abuse both to pad its own bottom line.

There are 800,000 EU-based sellers on Amazon, and they have seen the junk-fees that Amazon charges them skyrocket, to the point where they have to raise prices or lose money on each sale. Amazon uses both tacit and explicit “Most Favored Nation” deals to hide these price-hikes. Under an MFN deal, sellers must not allow their goods to be sold at a lower price than Amazon’s — so when they raise prices to cover Amazon’s increasing fees, they raise them everywhere:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/25/greedflation/

It’s not hard to understand why Amazon would raise its fees: the company has an effective e-commerce monopoly. Like Ozymandias, they have run out of worlds to conquer, and so their growth has to come from squeezing suppliers and/or raising prices, not from bringing in new customers. This is likewise true of mobile companies like Apple and Google, who have run out of people who are so excited about incremental mobile hardware gains that they’ll buy a new phone every year, which means that growth has to come from squeezing app vendors:

https://www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/202x/2023/06/09/Pixel-4-to-7

This is likewise true of the streaming companies, which is why Netflix is cracking down on “password sharing”:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/02/nonbinary-families/#red-envelopes

It’s true of the movie studios, which is why they want to zero out their wage bills by replacing writers with automatic plausible sentence generators that will write stupid movies that they think we’ll still pay to see because there won’t be anything else:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/06/people-are-not-disposable/#union-strong

It’s certainly true of Uber, which is why they’ve double the cost of a taxi ride and halved the wages they pay drivers:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

Monopolies “grow” by making their customers and suppliers worse off. But they have to be careful about this: if it’s obvious that you’re using your market power to screw buyers, you can get in trouble with competition regulators. That’s because the only part of antitrust law that the neoliberal project left intact is “consumer welfare” — the idea that monopolies should only face enforcement when they raise prices and/or lower quality:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/10/play-fair/#bedoya

This focus on price-hikes has given monopolists a free hand to squeeze suppliers and workers, because a monopolist — from Walmart to Amazon — can claim that squeezing your workers and suppliers is necessary to enhancing consumer welfare. The less you pay to produce a product, the cheaper you can price it.

When a company has a lot of seller power, we call it a monopolist. When it has a lot of buying power, we call it a monopsonist. No one ever made a bestselling, family-destroying board game called “Monopsony” so most people haven’t heard of the concept. But monopsony is every bit as dangerous as monopoly, and monopsonists find it far easier to acquire market power than monopolists. Few suppliers can afford to have even 10% of their sales disappear overnight, so a buyer who accounts for 10% of your sales can demand deep discounts and other favorable terms.

Amazon is a monopolist, but it’s also a very powerful and ruthless monopsonist. For example, its audiobook division, Audible, has a 90+% market-share, and it used that market-power to steal at least $100m from audiobook creators, in a scandal dubbed Audiblegate:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/07/audible-exclusive/#audiblegate

For Europe’s 800k sellers who rely on Amazon to reach their customers, the monoposony conditions are blatant and shameless. Take listing fees: Amazon’s “flywheel” pitch claims that as the company grows, it achieves “economies of scale” that can lower its cost basis. But Amazon’s listing fees haven’t changed, even as the company experienced explosive growth in the EU (remember, sellers whose Amazon fees exceed their margins have to pass those fees onto buyers, and also raise their prices everywhere else to satisfy the Most Favored Nation requirement).

Amazon books the revenues from these fees — and other junk-fees it extracts from sellers — in Luxembourg, an EU member nation that provides a tax haven to multinational businesses that want to maintain the fiction that they operate their businesses out of the tiny kingdom. There is sharp competition in the EU to offer the most servile, corrupt environment for multinationals, and Luxembourg is a leader, along with Cyprus, Malta and, of course, Ireland:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/15/finnegans-snooze/#dirty-old-town

But at least listing fees haven’t gone up, unlike other fees, which have climbed sharply. Amazon falsely claimed that its additional revenues from fees were the result of growth by independent sellers, which Amazon pegged at 65%. Later, the company admitted that the true growth figure was 22%. Meanwhile, fees are up 85%.

The true growth figure might be lower still. Amazon refuses to show the math behind its growth figures, or even say which sellers and sales are included in the figure.

The SOMO report cites research by Juozas Kaziukėnas of the e-commerce research firm Marketplace Pulse, who finds that sellers are now giving 50% of their gross revenues to Amazon, an increase of 10% over the past five years across the whole EU. However, different EU (and ex-EU) countries have experienced much steeper increases in fees — in the UK, fees have nearly doubled (up 98%), and in France, fees more than doubled (up 115%).

Many of these increases come from the Fulfilment By Amazon (FBA) program, which is promoted as an optional service, but which is really obligatory — careful research shows that sellers who warehouse, pack and ship their own goods get banished to the depths of search results, even if they have ratings, costs and times that are competitive with FBA. This is especially true of the “buy box” that lands at the top of most searches. The company refuses to disclose how buy box positioning is determined, but 90% of products in the buy box pay for FBA.

Amazon has used excuseflation to hike its FBA prices, blaming higher energy prices for price hikes that predated the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and blaming covid for price hikes that predated the pandemic.

Italy’s competition authority did yeoman service in uncovering the sleaze of FBA, publishing an investigation that showed that Prime and buy box made the notionally “optional” FBA into a must-have for merchants, meaning that Amazon could jack up FBA prices without losing business.

Another notable source of gouging came in response to the UK and France adopting digital services taxes, which were meant to make up for the tax-base erosion enabled by Luxembourg’s flouting of EU tax law. Amazon passed these taxes straight through to its merchants, without seeing a comparable decrease in the number of sellers using its platforms — an unmistakable sign of market power. If you can raise prices without losing customers, then, by definition, your customers have nowhere else to go.

I’ve previously written about how Amazon’s $31b/year “advertising” market isn’t really advertising — rather, it’s a payola scheme that auctions off the top of a search-listing to the merchant with the most to spend:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

This is how you get a simple search like “cat beds” returning results whose first screen is 100% ads, and whose next five screens are 50% ads, many of them for dog products:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2022/amazon-shopping-ads/

Auctioning off search results means that every time you search for something you want, you have to wade through screen after screen of listings for products whose vendors spent more on advertising, leaving less to spend on making quality goods.

This is as true in the EU as it is in the USA. The SOMO report shows that European merchants are required to spend ever-larger sums to show up in results for the exact products they sell, leaving them with a choice between making less money, raising prices, or skimping on quality.

But even the “winners” of Amazon’s gladiatorial combat among vendors can still lose. Amazon uses an automated product removal process that can delete some or all of a merchant’s products, without warning or explanation, and no one at Amazon will explain what a merchant did wrong. That remains true even if a vendor pays for Amazon’s “marketplace consultant” service — ask these paid Virgils why you’ve been cast into Amazon’s pit, and they’ll shrug their shoulders (and bill you for it).

And even if you can navigate the junk fees, the Kafka-as-a-service removals, the war of all sellers against all sellers for search primacy…you still lose. Merchants told SOMO that a product that survives Amazon’s gauntlet is likely to be cloned by Amazon and sold as an Amazon Basic or other house-brand product. Amazon doesn’t charge itself 50% junk fees, so it can always underprice the vendors it knocks off, and give its own products permanent top-of-search placement.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos once testified under oath before Congress that this doesn’t happen — and then refused to return to Congress when multiple vendors showed evidence that he’d lied:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/10/18/amazon-congress-letter-third-party-data/

He definitely lied:

https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/amazon-india-rigging/

Amazon has faced investigations and enforcement in the EU over this, and settled a claim with a promise to “not use non-public seller data to compete with sellers,” but given the company’s record of broken promises on this score and the difficulty of catching them cheating, it’s pretty naive to think they’ll stick to this.

The report quotes Thomas Höppner, a lawyer who has represented small businesses that Amazon screwed over. Höppner says the problem is that the EU evaluates Amazon’s bad deeds on a “case-by-case” basis, missing the big picture: “By the time one identified problem was seemingly solved, Amazon had long made amendments elsewhere with the same effect. We require a more holistic approach that considers the entire Amazon ecosystem and the various interdependencies within.”

But the EU’s enforcement approach is about to change significantly. The EU just passed the Digital Markets Act (DMA), which imposes a bunch of obligations on Amazon:

allowing sellers to offer their products on other marketplaces at different prices (Article 5.3),

not obliging business users to pay for one of its services in order to use its platform (Article 5.8),

limiting the way Amazon uses non-public seller data to compete with them (Article 6.2)

preventing Amazon from giving top billing in search results to its own products or sellers that have acquired extra Amazon services (Article 6.5)

The report concludes with a suite of recommendations for improving EU enforcement. First, they argue for a return to traditional competition law, abandoning the “consumer welfare standard” that is so friendly to monopsonies and their abuses of suppliers and workers.

They call for a probe into Amazon’s Most Favored Nation deals (“fair pricing policy”), the practice of sponsoring search results, and spiraling fees. They want the EU to adequately fund DMA enforcement, with “measures to prevent regulatory capture.” And they want Amazon to publish clear explanations for how search results, buy box placement, and other practices hidden behind a veil of secrecy.

Amazon will doubtless claim that disclosing how those systems work will make it easier for spammers and scammers to game their way to the top of search results. We should be skeptical of this claim — content moderation is the last domain where anyone takes the bankrupt idea of security through obscurity seriously:

https://doctorow.medium.com/como-is-infosec-307f87004563

Finally, the report calls for breaking up Amazon, forcing it to choose between being a platform seller or a platform user, calling this the only way to “prevent the conflicts of interest between its role as a platform intermediary, seller, and service provider.”

The technical term for this measure is “structural separation” — a rule that bans platform companies from competing with their business customers. This is the principle at work in the US bipartisan AMERICA Act, which would force Google and Meta to spin off the parts of their ad-tech business that put them in a conflict of interest. Right now, Googbook represents both publishers and advertisers, while operating the marketplace where ad sales take place, and they take 51% out of every ad dollar:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

Structural separation hasn’t really been applied in the US for a generation, but it’s gained currency in recent years, for the obvious reason that the referee can’t also own one of the teams. I was in Germany last week speaking to regulators and politicians, and they espoused skepticism that the EU would embrace structural separation anytime soon.

But they were wrong! Today, the European Commission announced plans to force Google and Meta to sell off their conflict-of-interest ad-tech lines of business, mirroring the provisions of the US AMERICA Act:

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2023/06/google-may-soon-be-ordered-to-break-up-its-lucrative-ad-business-eu-warns/

Structural separation really is the policy we should be demanding. It’s amazing that lawyers who would never argue a case in front of a judge who was married to the plaintiff will turn around and defend the idea that Amazon can fairly operate a marketplace where they compete with other sellers.

With Amazon dominating online sales, and with in-person retail cratering, Amazon’s decisions have the power to determine the outcome of whole swathes of Europe’s economy. This is the “planned economy” that the EU claims it detests and seeks to prevent — but it’s an economy planned by distant autocrats in a Seattle boardroom, for the purpose of extracting the surpluses needed to launch an endless procession of penis-rockets.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this postto read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/14/flywheel-shyster-and-flywheel/#unfulfilled-by-amazon

[Image ID: A desert ruin. In the foreground is a huge Amazon box, with an EU flag in place of its shipping label. Atop the box are the feet and partial legs of an Oxymandias figure.]

Image: Rama (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gladiator_with_sword-Louis_Ernest_Meissonnier-MG_1216-IMG_1223-white.jpg

CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/fr/deed.en

#pluralistic#payola#digital markets act#dma#Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations#planned economies#kafka-tech#fba#Luxembourg#amazon#enshittification#monopsony#chokepoint capitalism#Margarida Silva#flywheel#eu#fulfillment by amazon#junk fees#ad-tech#somo

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Discover how Amazon FBA can transform your eCommerce business. From effortless logistics solution to reaching millions of customers, learn how to maximize your business growth with Fulfillment by Amazon. Read now and take your business to new heights!

0 notes

Text

The Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) business model has revolutionized how online sellers manage their operations. By leveraging Amazon's extensive fulfillment network and Amazon FBA Management Software, sellers can streamline logistics, enhance inventory control, and focus on business growth.

1 note

·

View note

Text

E-commerce Fulfillment Solution

Warehousing, Logistics and Mailing Houses!

Elevate your e-commerce game with FloStream's Amazon Fulfillment FBA services!

Our expert team ensures smooth order processing and timely deliveries, so you can delight your customers every time.

Say goodbye to shipping hassles and hello to seamless operations!

0 notes

Text

Wait you guys are actually buying Disney products I thought it was a joke

(READ TAGS FOR FULL CONTEXT Sorry it’s long dies

#Honestly I’m only bothered bc I feel partially responsible (WTF EGOMANIAC OVER HERE)#I know I can’t control other people’s spending habits and my own habits are. Less than ideal !!#But when I wanted to spread my love for Wreck it Ralph I didn’t want people to get that takeaway 😔#IMPORTANT NOTE ‼️It’s okay to express your love for something through buying official things !!! That DOESN’T make you a “bad person” !!!#Still ! I think we have to let ourselves feel bothered by things and we need to be more critical of exploitative companies#Of course I chose to watch inside out 2 with my mom in theaters so I’m not immune lmao. Also using amazon / Etsy … just as a whole#But if you need help finding Disney movies without supporting them please just ask me!! PLEASE don’t use Disney+ if you can avoid it#I know we are all capable of finding our fulfillment from better places. But sometimes it’s hard#Capitalism sucks and yet that’s how we are endlessly pressured to live :(#We’re all at different points in our lives. Sometimes self care involves consumerism#Be hopeful that it someday won’t have to#Txt#again I’m sorry if this comes off as horribly egotistical to even consider being single-handedly responsible for#Social media is bad …. numbers bad…. Distorts reality and your perception of yourself…..#Or as me trying to guilt trip people in any way. Genuinely do what makes you happy but WE CAN BE HAPPIER & HEALTHIER I KNOW WE CAN#Wreck it ralph#Rant#Also sorry I have huge beef with streaming services I don’t mean to enforce that on other people but also. Sharing my opinion

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from The Revelator:

In recent decades the Inland Empire — comprised of San Bernardino and Riverside counties — has been the primary victim of America’s warehouse boom. As demand for online shopping has surged — e-commerce sales grew 50% to $870 billion during the pandemic alone — this region has served as a billionaire’s dumping ground. Those are the words of Tom Dolan, executive director of Inland Congregations United for Change. “Now it’s no longer just Warren Buffet, it’s Jeff Bezos and Amazon,” Dolan told The Guardian in 2021. “And we’re paying the cost of doing their business.”

That business is only made possible by taking out a nonconsensual loan from the residents of surrounding communities. It’s a coercive trade: the health and safety of citizens for the profits they’ll never share. And no worthwhile efforts have been made to pay off that debt.

In order to fulfill the glamorous promises of expedited, overnight and same-day deliveries, diesel trucks conduct over 600,000 daily trips through the Inland Empire alone, carrying roughly 40% of the nation’s goods. These vehicles emit 1,000 pounds of diesel particulate matter every day (alongside 100,000 pounds of nitric oxide and 50,000,000 pounds of carbon dioxide).

The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified diesel particulate matter as a Group 1 carcinogen — the most severe category — due to sufficient evidence linking diesel exposure to lung cancer. (Other studies have suggested a relationship to cancers of the bladder, larynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas and blood, alongside asthma, other respiratory disease, heart attacks and premature mortality.) The region bordering the warehouse hub in one Inland Empire city, Ontario, ranks in the 95th percentile of cancer. A 2015 study estimated that 70% of the total cancer risk from air pollution in California is caused by diesel exhaust alone.

The people who suffer the consequences of our online shopping are not typically over-consumers themselves. The South Coast Air Quality Management District found that the 2.4 million people living within half a mile of a warehouse are also disproportionately Black and Latino communities below the poverty line. In 2012 San Bernardino ranked as the second poorest city in America with over 34.6% of people living in poverty. And of all the residents living within a mile of the average Amazon warehouse, 80% are people of color.

20 notes

·

View notes

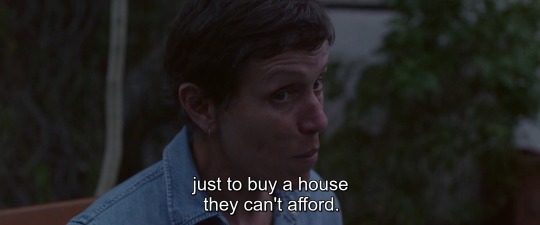

Photo

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020)

#Nomadland#Chloé Zhao#USA#drama film#Jessica Bruder#Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century#life#Frances McDormand#David Strathairn#Linda May#Bob Wells#United States of America#working class#working poor#U.S.A.#Amazon fulfillment center#Nevada#workers#Arizona#road#Great Recession#nomads#friendship#South Dakota#ocean#independence#California#friends#generosity#helpfulness

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

But though the World be yours, it is not safe

Depending on a fickle multitude

Whom Interest and not Reason renders just.

Vallentio to the newly-liberated King Orsames, The Young King by Aphra Behn, V.iii.46-48

#so for context. orsames is essentially segusmundo from calderon's la vida es sueño#he's been living in a cave with only his tutor geron his whole life because of a prophecy that would be devastating to fulfill#it's the secondary plot in the young king but it is the plot the title refers to interestingly enough#thersander and cleomena aren't just my favs but they do get a lot more scenes which gives more to talk about#in this adaptation they still have the dream sequence but later on cleomena confounds the prophecy#by being like well that WAS his reign so it's fulfilled. now he should be liberated and able to become king#and she facilitates his release so she can go on a suicide mission to avenge clemanthis and dacia still has an heir#(orsames is her brother and thus in a male primogeniture-assumed monarchy the more rightful heir)#she's been raised as the presumed heir her whole life and that's why she's basically an amazon. i love my girl so much#cleomena is my biggest early-modern drama blorbo in such a long time#aphra behn#the young king#poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 2017 another worker, Philip Lee Terry, fifty-nine, was crushed to death by a forklift he was working beneath in the maintenance area, in Plainfield, Indiana. He lay in a pool of blood for two hours before anyone noticed him. The state initially fined Amazon $28,000 for four major safety violations, including failure to train Terry in how to elevate the forklift properly. But the state OSHA director offered company officials advise in how to negotiate down the fines and shift blame to Terry, in a phone call recorded by the OSHA inspector on the case, John Stallone. After hanging up with Amazon, the OSHA director said to Stallone, 'I hope you don't take it personally if we have to manipulate your citations.'

-Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America, by Alec MacGillis

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is technically a Diana's age poll but I framed it partially around Julia's rescue because that's the event I need to contextualize and whether or not Diana is a thing yet is p important for my purposes. I would keep the Pérez run and postcrisis continuity in mind when answering this bc that's when this is relevant but I'd keep in mind that even though Diana is very young there (like early 20s) we don't know I don't think if she ages differently as a child (esp as a themysciran AND being made from clay) and in some versions she is older than she looks and was made earlier

Edit: I accidentally logic-ed this out in the tags lol 🤦♀️but feel free to still vote however you want. Going to publish this anyway bc I think I made some good points later in my tags

#blah#the 45 years is a guesstimation of julias age w her being in her late 40s#bc she has a middle school aged daughter which would make you lean a bit younger but shes also highly respected prof at harvard (is she the#dept head? i think so. and has a career that would suggest older. and shes also drawn middle aged so 🤷♀️#i would say late 40s early 50s for her honestly. but i moved it down a lil bit bc of vanessas age#wait shit i may have contradicted logic here bc wasnt the diana trevor stuff supposed to have happened before dianas birth. and that was#wwii. which would be btwn 42 and 45 years. BC PÉREZ!TREVOR IS OLD I FORGOT THAT#okay so actually there still could be a question of what happened first the timeline would just be much shorter#but then wouldnt julias family be boating during wwii? that makes no sense#im definitely thinkimg too hard about this probably. logically it would make the most sense if diana was like 20smth in reality. but thats#its own basket of worms honestly. like what do you mean hippolyta only had like 20 yrs w her daughter out of a lifespan of thousands of#years. what do you MEAN she became champion and ambassador so young like#like also thats the point though. she had to wear a mask in the challenge for a reason. her inexperience with men is what makes her the kind#of ambassador they need. and her youth and relation to hippolyta and role as the baby of the amazons is one of the things that makes her#ambassadorship SO important is bc she fulfills that role in an ancient sense. where it would be a sign of great trust and respect to send#someone close to the crown as an envoy bc it shows you mean business and arent going to reneg on whatever the deal is. bc if you do they#shoot the messenger#god anyways i very much answered my own question here in the tags like 100%. esp in regards to the pérez canon bc he very much laid this out#and i was trying to weasel my way out of it. only that didnt work and the decisions he made he made for a reason and they have huge#narrative importance. damn. okay then#i always write the shittiest posts and the best tags and then have to keep the post to keep the tags#i rlly need to make these tags posts ugh. anyways keeping this up bc of my tags abt diana and ambassadorship#also sidenote I LOVE HIPPOLYTA#just though id mention that. i love how much shes motivated by love and i also love when she makes fucked up decisions bc of that and has to#live with them. woman of all time FOR REALS#god this is making me want to reread historia again lol bc its the one ww comic i own. also its fire. and hippolyta gets to make shitty#decisions motivated by emotion and live w the consequences. and the comic is actually good unlike when that happened in the messner-loebs#run. which was the other instance of that ive read rlly. 10000% sure there are others but i havent fully gotten there yet.#i mean ive read other comics where she makes painful decisions thats like her whole deal but there are different vibes to those than the two#i mentioned. like the exile thing in ww year 1 or rlly anytime she has to send diana away

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

having a boomer moment as i walk past a group of kindergartners being herded omw home and half of them are like on their hands and feet crawling and turning themselves around and in general, bumbling around with lots of excess energy like children are want to do and my immediate half relevant thought was "and the WOKE LEFT want to give these KIDS adhd meds!!!!!!" it really does horrify me that we are deliberately stunting our children in such a vital developmental phase just because theyre.....like not maximizing their productivity? they arent purely efficient little automatons marching from place to place? because its mildly more of a hassle herding kids vs lobotomized cows. its evil. it is.

#why isnt my 7 year old acting like an amazon fulfillment worker should we pour hot oil in their brain to subdue them like a dahmer victim#giving your kid psychiatric meds because theyre a kid is the silent ipad baby crisis#i just!!!! its such a form of neglect too thats how it was with my mom instead of literally ever talking with me or doing any sort of effort#into changing the household or relationship or lifestyle it was just the pill carousel and i cant blame her for it bcs thats the lie#big pharma sells the public struggling with family that there will eventually be a magic cure pill you just have to keep trying

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Running a successful Amazon FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon) business is no easy feat, but once you've achieved a steady stream of sales, it's natural to want to scale your operation and take it to new heights.

0 notes

Note

I don’t mean to bother you or anything but do you think you’ll ever sell your stuff on Amazon?

Probably not. It's not really a marketplace that aligns with my brand values. And it's generally frowned upon in all other small business circles (in fact some marketplaces like Faire and Handshake will blacklist you if you sell on Amazon). The fees on Amazon are also higher than Etsy's so there's no point in using it instead of Etsy.

#they do offer Fulfillment with Amazon where you can ship your stuff to them and they'll handle storage and shipping etc#that would be nice...but yeah not worth getting blacklisted by literally everyone LOL#ask

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flostream is rapidly growing Mailing and Fulfilment services provider based in the South of England.

Our cutting edge mailing equipment and a large network of delivery agents allow us to offer our customers an incredibly agile solution to their fulfilment needs.

#Warehouse Storage#Fulfillment Services#Amazon FBA#E-Commerce Fulfillment#Third Party Logistics#Mailing Services

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How can an Amazon FBA Prep Center Boost Your Business 10X?

Learn how using an Amazon FBA prep center can streamline your operations, improve efficiency, and boost your business by 10X. Fulfillville® provides comprehensive fulfillment services, from inventory management to shipping, designed to support your growth. Start maximizing your business potential with Fulfillville® today!

#Amazon FBA Prep Center#Amazon FBA Prep#FBA Prep Center#fulfillment#b2bfulfillment#warehousespace#dropshipfulfillment

0 notes