#French director biopic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

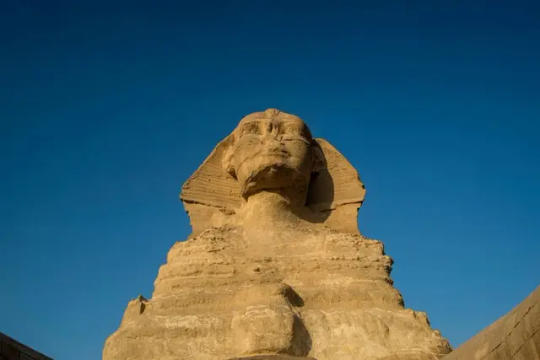

The Hunt: What Happened to the Great Sphinx’s Nose?

The mystery of the Egyptian statue's missing nose has fascinated people for centuries.

Much like the desert winds that perhaps helped shape it, conspiracy theories swirl around the Great Sphinx guarding the Giza plateau—especially regarding how the winged lion’s human head lost its nose. One enduring hypothesis blames Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops for blowing the snout off during target practice. While that conspiracy’s long-debunked, it persists in popular culture. Director Ridley Scott knowingly depicted the myth in last year’s Napoleon biopic, without sacrificing any of his film’s critical acclaim. However, Egypt’s Dr. Zahi Hawass told Britannica, “We have, really, to say to everyone that Napoleon Bonaparte has nothing to do with destroying the Sphinx’s nose.”

Napoleon’s 1798 battle didn’t even take place on the Giza plateau, but 10 miles north at Imbabah. Some theories have posited that storms and earthquakes shook the Sphinx’s nose from its face. Others squabble over which regional conflict (if not Napoleon’s Battle of the Pyramids) led to the nose’s destruction. In 1990, J.P. Lepre noted that “the figure was used as a target for the guns of the Mamluks,” who were actually Napoleon’s opponents.

The French emperor did, however, lay eyes on the Sphinx’s face when he arrived in Giza, with many soldiers, painters, and engravers in tow. “Thousands of years of history are looking down upon us,” he reportedly exclaimed beneath the monument’s gaze. Napoleon didn’t respect borders, but he did respect history. The Waterloo Association called the lingering accusations against him “particularly unjust because the French general brought with him a large group of ‘savants’ to conduct the first scientific study of Egypt and its antiquities.” The resulting Orientalist survey ignited an Egyptian fervor back in Europe.

Primary materials prove the nose removal predated Napoleon, too. Danish naval captain Frederic Louis Norden’s sketch from 1738 depicts the Sphinx without its central facial feature. What’s more, French naturalist Dr. Pierre Belon visited the Sphinx in 1546, writing that it had sustained damage and “no longer [had] the stamp of grace and beauty so admired by Abdel Latif in 1200”.

Medieval Arab scholars such as al-Maqrīzī pin the damage on Muhammed Sa’im al-Dahr, a 12th-century Sufi Muslim from a respected Cairo convent, who was allegedly angry that peasants used the Sphinx to entreat Abul Hol (the Arabic name for the sphinx) into helping their harvests. Removing an idol’s nose was an accepted method to suffocate spirits inside. Still, the details remain up for debate. Hawass believes that al-Dahr acted alone. Others claim he hired men to desecrate the Sphinx. Most experts, however, agree the great statue’s nose came off with a chisel. It is also generally accepted that al-Darhr’s actions got him killed by angry villagers. Sadly, the nose itself has likely crumbled into the desert.

By Vittoria Benzine.

#the sphinx#The Hunt: What Happened to the Great Sphinx’s Nose?#Giza Plateau#sculpture#statue#pharaoh Khafre#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian gods#egyptian pharaoh#egyptian mythology#egyptian art#ancient art

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

FAVORITE FILMS OF 2024

You could say going to see a movie at a theater is my hobby. I much prefer the theater experience. I saw 40 new films released in 2024. Only one of those via streaming because it was only shown in two theaters (LA and NYC).

Below are my nine favorite films and the reasons why. I added to honorable mentions (coincidentally both biopics) that I liked but had flaws that prevent me from calling them favorites.

I’ll post a list of my least favorite films later.

The Return (Odyssey) (12/05)

This film tells the last chapters of Homer’s the Odyssey. Odysseus (Ralph Fiennes) return home from the Trojan War after being away from 20 years. No one recognizes him and his wife (Juliette Binoche) is being pressured by dozens of men to finally remarry. The film is very faithful to the story. Very well done and both Fiennes and Binoche are terrific.

Count of Monte Cristo (01/06/25)

It’s based on the 1844 novel book by Alexander Dumas (author of the Three Musketeers). Monte Cristo is beautifully filmed and suspenseful from start to finish. (French with subtitles, limited release)

September 5 (12/09)

A film about the hostage taking at the 1972 Olympics at Munich. But it’s told from the perspective of the ABC sports crew there to report on the sporting event. I was surprised by how suspends they were able to tell the story. Some good performances by John Magaro as the control room director and Leonie Benesch as a German member of the crew.

Mars Express (05/07)

Another French movie - this one animated. It set in the far future where robots of all types work side-by-side with humans. A human detective and her robotic partner try to find a missing girl. Like all good detective stories, the more they dig, the bigger the conspiracy becomes. The art design is superb.

Nosferatu (12/25)

This remake is probably one of the best retelling of Dracula. But all the names have been changed. Orlok the vampire isn’t a romantic Count, he’s hideous. It’s creepy and beautifully shot. I particularly liked Nicholas Hoult (as a version of Johnathan Harper). He’s is terrific. (How did he sustain that level of fear and panic during the shoot?) My only “but” regarding “Nosferatu” is that I thought it was too long. It may eventually show up on Peacock but I’m an advocate for seeing movies in theaters.

Wicked: Part One (11/22)

Cynthia Erivo is terrific as Elphaba, the future Wicked Witch. Her closing number “Defying Gravity” is a show stopper. Ariana Grande as Galinda holds her own opposite Erivo. The special effects and art design are also great. A couple of things keep it from being the top of my favorite list: too many of the supporting characters came off like gay stereotypes; and does Jeff Goldblum ever actually play a character or does he just play himself in everything he’s cast in?

Conclave (10/26)

I did not plan to see “Conclave”. I don’t have any interest in stories about religion nor the Catholic Church in particular. There aren’t any murders in “Conclave” but the plot follows a typical detective mystery story - Fiennes must discover who is telling the truth, and what secrets are they hiding. Fiennes is very good and it was nice seeing Isabella Rossellini in a small role.

Challengers 04/26

Challengers is about professional tennis players starring three of best young star of modern Hollywood (Zendaya, Josh O’Connor, and Mike Faist). There are many sexy scenes of sexy actors kissing each other sexily. But the real action is on the tennis court, where they exerting themselves, sweating, grunting and slamming the ball. At there first meeting, Zendaya asks the boys if they already have girlfriends, because she doesn’t want to be a Home Breaker. This question will have repercussions in the years to come. The film is well paced and edited (especially the tennis matched). It’s directed by Luca Guadagnino who directed “Call me by your name” (2017).

Dune Part 2 (03/01)

Part 2 lives up to the promise of Part 1. Denis Villeneuve’s films are vastly superior to David Lynch’s 1984 film. The worlds and worms are masterfully created. Timothée Chalamet leads a terrific cast. The one exception is Christopher Walken as the Emperor - another actor who stopped “acting�� decades ago).

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Better Man (01/07)

This is Robbie Williams biopic where he’s portrayed by a CGI chimpanzee. I accepted the conceit immediately. The movie is at its best in the first half and with the musical numbers. They are dynamic, cleverly stage and edited (especially Rock DJ). I didn’t enjoy the second half as much, as it dived into Williams’ addictions and ends with a couple unearned redemptions.

A Complete Unknown (12/25)

This is the Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothée Chalamet. The supporting cast is terrific: Edward Norton as Pete Seeger, Scoot McNairy as Woody Guthrie, Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez and Elle Fanning as Dylan’s on again off again girlfriend. While Chalamet is good as Dylan I felt the character was a selfish asshole.

#favorite movies of 2024#the count of monte cristo#the return with Ralph Fiennes#nosferatu#conclave#challengers#September 5 Munich hostage attack#wicked#better man chimpanzee#a complete unknown asshole#dune part 2#mars express

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mads poll with a difference!

A poll of Mads Mikkelsen movies where the selection is based on range of factors, including but not limited to: genre, writer/director, country of release, date of release and 🎉vibes 🎉

Some of the movies may fit in more than one category, so vibes have mostly informed those decisions.

Round Two:

Choose your fave!

The winners from Lil' bit o' Mads and They could have been blockbusters!! face off:

King Arthur is a 2004 UK-US-Irish historical adventure. Setting the legend of King Arthur against the backdrop of the Roman Empire rather than a medieval retelling it revolves around defending the area around Hadrian's Wall. Mads plays Tristan, one of the knights of the round table (and Hugh plays fellow knight Galahad :3)

At Eternity's Gate is a 2018 French-UK-US biopic of the painter Vincent van Gogh, chronicling his final years. Mads plays a priest at the mental asylum where van Gogh is placed after cutting off his ear.

#mads mikkelsen#hannibal#hannigram#hannibal extended universe#king arthur#king arthur 2024#tristan#at eternity's gate#my polls#tumblr polls

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m just a defense analyst, so I’ll leave a proper critique of Ridley Scott’s new blockbuster biopic Napoleon to the many reviewers who have already disparaged it. I, for one, found it to be a lukewarm mélange of battle scenes and romantic vignettes, leaving me with neither a sense of the man Napoleon Bonaparte—the bicorne-hatted soldier-turned-emperor of the French—nor a feel for the age of upheaval he so much defined. For a grand piece of historical fiction from the director of such masterpieces as Blade Runner, Thelma & Louise, and Black Hawk Down, the film curiously fails to entertain.

My perspective on Napoleon is a different one. Scott’s film stands in a long line of movies, novels, and even history books that have given the world an entirely wrong view of how wars are fought—and even more importantly, how they are won. And that matters, because the mythical idea of war embedded in Napoleon and so many other works has become so widespread in our culture and discourse that it ends up informing actual decisions about actual wars.

Let’s call it the decisive battle myth. Napoleon, with its focus on famous battles such as those of Austerlitz and Waterloo, perpetuates the dangerous idea that wars are decided by great and bloody clashes. This obsession is as old as there have been written accounts of history, but in popular culture in the English-speaking world, the myth can be traced back to the 1851 publication of The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo, which helped kickstart an entire genre of works focusing on battles supposed to have singlehandedly changed the course of history. In film, think of The Longest Day, Midway, and Stalingrad; in books, the list of battle histories and battle fiction is too long to contemplate. The genre even plays in counterfactuals: The 1993 movie Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels, suggests that the South could have won the U.S. Civil War had the Battle of Gettysburg gone the other way.

No matter what these works have taught us to think, the decisive battle is a myth. Wars between major powers are not decided by great battles but by attrition of soldiers and materiel, which in turn is determined by such things as force size, logistics, production, and technology. Battles, large and small, are important only to the extent to which they accelerate attrition and wear down the other side. Yet the myth of the decisive battle—the idea that an adversary can be defeated in one big and bloody but short engagement—remains powerful. It’s also dangerous, because it affects not only ordinary moviegoers but military and political leaders as well. In other words, the very people deciding whether to start and how to fight a war.

Scott’s focus on battles is hardly surprising. Napoleon fought numerous campaigns culminating in big set-piece battles, after which the defeated side sought peace; at the Battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon defeated the allied armies of Austria and Russia, forcing the former to sue for peace and the latter to retreat home. But the French emperor’s most celebrated victory—exactly 218 years ago today—was only an episode in a long war that did not end until 10 years later, after attrition and mutual exhaustion.

The focus on decisive battles orchestrated by a brilliant military leader such as Napoleon has been poisoning Western military thinking for centuries by suggesting that great power wars can be short affairs. The idea that an adversary can be decisively beaten in just one or a few engagements has incentivized political and military gambling: Think of the German Schlieffen Plan that bet on a single, decisive encirclement of French forces and their quick annihilation or capitulation in 1914, with the disastrous result of condemning much of Europe to four years of attrition with millions of soldiers killed. The idea of a quick, decisive battle inspired then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to invade Iran in 1980, which led to a horrifically bloody eight years of attrition.

More recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin thought one decisive push toward Kyiv in early 2022 would quickly and painlessly conquer Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of deaths later, the grinding war goes on. For all the emphasis on Napoleon’s quick campaigns and decisive battles, his wars tell a similar story of long and painful attrition: More than 5 million European soldiers were killed or otherwise died during the Napoleonic wars, a level of carnage, relative to total population, on par with World War I. France alone lost around 860,000 soldiers, including 38 percent of all men born between 1790 and 1795.

That Napoleon is only a movie doesn’t make it better. There are documented cases of films influencing a policymaker’s decisions to go to war. In 1970, for example, then-U.S. President Richard Nixon repeatedly watched the film Patton during the decision-making process to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia, taking inspiration from the movie general’s willpower and single-minded belief in U.S. military power. One academic study found that popular culture, including fictional films, can frame the way we think about a multitude of issues, and there is no reason to believe that military officers and policymakers are exempt from these effects. Movies can help prevent wars, too. Former U.S. President Ronald Reagan was inspired by the television film The Day After and Tom Clancy’s novel Red Storm Rising to push for nuclear arms control. But if decision-makers and military leaders are prone to fighting the wars of their imagination, then a popular culture that reinforces the idea that wars can be short and decisive may incentivize willingness to look for a quick military solution to a political problem.

There is much more in Napoleon that made me cringe as a military analyst. What you see on the screen has absolutely nothing to do with warfare in the age of Napoleon—as a matter of fact, the clouds of gunpowder from the era’s muzzle-loaded muskets meant you would not be able to see very much on a Napoleonic battlefield to begin with. The battle scenes are a Hollywood mishmash of medieval melees, meaningless cannonades, and World War I-style infantry advances.

One scene that stands out is the apocryphal depiction of Napoleon leading a cavalry charge into what are supposed to be the Russian lines at the Battle of Borodino. As a former artillery officer, of course, Napoleon never led a cavalry charge in his life. For all of Scott’s fixation on Napoleon’s battles, he seems curiously disinterested in how the real Napoleon fought them—and just as disinterested in the changing character of Napoleonic warfare. By 1812, Napoleon’s enemies had not only learned to adapt by emulating the French style of fighting, but the battles themselves had turned into meat grinders of such a scale that no individual could control them. The battles of Wagram (in 1809), Borodino (1812), and Leipzig (1813) each involved hundreds of thousands of troops and many hundreds of cannons. The idea that the commander of his country’s armies in an 1812 battle had the liberty to lead a horse charge is so preposterous that the scene makes Mel Gibson’s Braveheart—considered one of the most historically inaccurate films in recent decades—look like a paragon of historical realism.

Napoleon’s military genius was not just about individual heroism or skilled battle tactics, but more importantly his vision for structural reforms. Napoleon helped institutionalize the corps system, dividing up large armies into smaller ones as a way to enable more effective command and control, as well as greater speed and range. Key to this new corps system were Napoleon’s marshals, distinguished military officers who sometimes remained undefeated in battle and whose deaths Napoleon mourned deeply. It was the marshals and other officers to whom Napoleon delegated authority; they proved to be a major asset contributing to his victories. In the film, these colorful independent actors are relegated to the role of footmen.

The film’s wild inventions go much farther. The British Army, led by the Duke of Wellington, features prominently, even though it played only a minor role in battle. Rather than the fighting role, the British contribution to Napoleon’s defeat lay in the sea blockade and in financing the huge standing armies of Austria, Prussia, and Russia that bore the brunt of the fighting. The duke and Napoleon never met in person, another invention of the movie that could have been omitted without loss, since it is devoid of meaningful dialogue that might have helped the audience better understand Napoleon’s volatile and ruthless character. Scott could instead have depicted the heated argument between Napoleon and Austrian diplomat Prince Klemens von Metternich during their famous eight-hour encounter in Dresden, then the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, in 1813. The meeting convinced Metternich of the French emperor’s troubling mental state and the impossibility of making peace as long as he reigned.

There is no reason to believe that the myth of the decisive battle will lose its power any time soon. As the historian Cathal J. Nolan writes in The Allure of Battle: “The idea of decisive battle will always be more alluring than winning by attrition—morally and aesthetically; to generals and theorists, and to publics hungry for war news.” Nolan might have added film directors to his list.

Let us hope that U.S. and NATO military strategists and force planners do not draw too deep an inspiration from Scott’s depiction of Napoleonic battle. It’s bad enough that the allure of the decisive battle is already shaping U.S. deliberations over how to fight a possible future war with China over Taiwan. Disregarding the likely attritional character and extended length of such a fight—and the requirements in manpower, weapons, ammunition, production capacity, and political constancy that would entail—could spell disaster for the United States and its allies. Focusing on long attrition instead of dramatic clashes would certainly make for a boring film experience, especially since one only has to look at Ukraine to see the long slog of attrition playing out in real life. Nonetheless, stripping Napoleon of the romanticism associated with epic battles decided by the archetypal hero on horseback would be a small first step in gaining a better understanding not only of past wars, but also of how future wars will be fought.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tony Lo Bianco

American actor who fitted naturally into the 70s trend for gritty crime thrillers as a brute with a twinkle in his eye

The American actor Tony Lo Bianco, who has died of cancer aged 87, specialised in hoods and heavies, often played with an uncommon twinkle in the eye that suggested he was in on some grim private joke. “I guess I’ll have to do a nun next,” he said after a run of such roles.

There was never any doubt that he meant business. “If you encountered Tony in a deserted alley at midnight, you’d be inclined to hand him your wallet before he asked for it,” wrote a US newspaper in 1978.

With his conspiratorial manner, imposing stare and tractor-tyre eyebrows, Lo Bianco fitted naturally into the 70s trend for gritty crime thrillers. As the mobster Sal Boca in The French Connection (1971), he is pursued by the New York cop “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) for his role in buying a massive shipment of heroin. The Seven-Ups (1973) reunited Lo Bianco with his friend and French Connection co-star Roy Scheider, and gave him a bigger bite of the cherry, this time as a shady police informer in a camel-hair coat and sharp hat.

His first major role had already proved he was more eccentric than any rent-a-thug. In The Honeymoon Killers (1970), which was inspired by real events, he played the silver-tongued Spanish con-artist Ray Fernandez, who embarks on a murder spree with a lonely woman whom he tries to swindle. Martin Scorsese was sacked as the film’s director for dragging his feet, but the end result (with the composer and librettist Leonard Kastle stepping in after Scorsese’s exit) has a sizzling, unwholesome B-movie tang, due in no small part to Lo Bianco’s oleaginous presence and his rapport with Shirley Stoler as his partner-in-crime.

Most of his finest screen work was done in the 70s. He was a police detective investigating seemingly random murders in the supernatural horror God Told Me To, and an injured, suicidal former rodeo rider raising his young sons in Glory Days, AKA Goldenrod (both 1976).

Bloodbrothers (1978), in which Lo Bianco was all gruffness and gristle as an Italian-American construction worker pressuring his recalcitrant son (Richard Gere) to follow in his footsteps, was especially dear to him. “It’s very close to my heart,” he said. “I know the characters like I know my family.”

In the same year, he was a surprisingly genial crime boss opposite Sylvester Stallone in the union drama F.I.S.T. “Sure, I could have played [him] as one more Italian thug,” he reflected. “But does the world really need another overbearing, obnoxious, obvious slob to dismiss or look down on as some kind of buffoon?”

Lo Bianco attributed his facility as an actor partly to his upbringing. “Coming from an Italian family in a big city, my emotions were always close to the surface, ready to live life fully, to give, to laugh and cry without holding back, without strain.”

He was born in New York City to Carmelo, a taxi driver, and Sally (nee Blando). One of his teachers at William E Grady high school suggested he give acting a go, though his early passions were largely sporting ones. As a teenager, he tried out for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and was also a Golden Gloves welterweight boxer. “I guess you’d say I was a borderline delinquent. It was the 50s, Elvis time, leather jackets, a time for being tough.”

Years later, he would step back into the ring to play the boxer Rocky Marciano in the television biopic Marciano (1979). He returned to the same story, again for TV, in Rocky Marciano (1999), this time as the gangster-turned-promoter Frankie Carbo opposite Jon Favreau as the prizefighter.

Lo Bianco studied acting at the Dramatic Workshop in Manhattan in the late 50s, and founded the Weekend Theater there in order to gain experience. “I built the sets, the stage, and put in the lighting. I got it going.” He did the same in 1963 with the Triangle Theater, where he also served as artistic director. It was here that he first met Scheider.

He accumulated numerous credits on television, including a recurring role between 1971 and 1973 as a doctor in the long-running soap opera Love of Life, and on stage: in 1975, he won an Obie (an award for an off-Broadway performance) for his portrayal of a fading baseball star in Yanks-3 Detroit-0, Top of the Seventh. He also won a Tony for playing the tormented longshoreman Eddie Carbone in A View from the Bridge in 1983.

Appearing in the Italian caper Mean Frank and Crazy Tony (1973) immediately after his success in The French Connection, Lo Bianco seemed to be spoofing his own image when it was still in its infancy: he played a none-too-bright crook who idolises a legendary gangster (Lee Van Cleef). But the actor re-asserted his authority on television in the anthology series Police Story (1973-76). He was one of only a handful of cast members who appeared in more than one episode. Even more unusually, he was on the right side of the law this time.

In Franco Zeffirelli’s mini-series Jesus of Nazareth (1977), he was Quintillius, who advises Pontius Pilate, played by Rod Steiger. A year later, also on television, he starred in The Last Tenant as a man dealing with the increasing needs of his senile, irascible father, played by the acting guru Lee Strasberg. In the 80s he won plaudits for a TV adaptation of Paul Shyre’s play Hizzoner!, in which he starred as the New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia. This spawned several spin-offs, including La Guardia and The Little Flower, written by Lo Bianco and performed by him across the world at the start of this century.

Notable later roles include a mafia boss in the lighthearted, 30s-set Clint Eastwood/Burt Reynolds vehicle City Heat (1984), a corrupt property developer in John Sayles’s ensemble drama City of Hope (1991), the ivory-haired mobster Johnny Roselli in Oliver Stone’s Nixon (1995), and yet another intimidating gangster in The Juror (1996), with Demi Moore and Alec Baldwin.

Like Robert De Niro, for whom he was sometimes mistaken, it seemed there was nowhere left to go but comedy after playing so many crooks. Having parodied himself at the very start of his film career, Lo Bianco did so again in Mafia! (1998), also known as Jane Austen’s Mafia!, a send-up from some of the team behind the Airplane! and Naked Gun spoof series.

Though he directed to acclaim on stage, he made only one film, the slasher movie Too Scared to Scream (1984). His final picture was Somewhere in Queens (2022), starring and directed by Ray Romano, in which Lo Bianco played the main character’s standoffish father.

He is survived by his third wife, Alyse (nee Muldoon), a writer, whom he married in 2015, two daughters, Yummy and Nina, from his first marriage, to the actor Dora Landey (Anna, a third daughter from that marriage, died in 2006), a brother, John, and six grandchildren. Both his previous marriages – the second was to Elizabeth Natwick – ended in divorce.

🔔 Anthony Lo Bianco, actor, born 19 October 1936; died 11 June 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My ★★½ review of Napoleon on Letterboxd https://boxd.it/5pDz3x

"YOU THINK YOU ARE SO GREAT BECAUSE YOU HAVE BOATS!!!"

-Napoleon Bonaparte (apparently)

The fundamental problem with this film can be summed up by the ending text which describes how Napoleon fought in 61 battles and lists out the few battles that were seen in the movie. Beside these names are, of all things, the number of casualties of each battle. It then says that in total, 3 million people died in his battles.

I'm not sure why that's the final takeaway Scott wanted us to have about Napoleon. The man was certainly flawed and ended up losing his power, but there is no denying that he was a military genius so charismatic and cunning that he swiftly rose from general to emperor. If you knew nothing about him before watching this movie, you would never know that he won almost 90% of his battles despite being outnumbered in many of them. Instead, we only see about 5 of these battles, 2 of which he loses and the others being strangely insignificant. During the battle of Waterloo, the British commander even points out that Napoleon is sleeping. Is this movie all just one big joke?

We see none of his military prowess or political acumen and instead have to watch him behave like a pathetic, petulant child desperate for power and his wife Josephine. While I believe there could be a good movie centered around Napoleon and Josephine, this was certainly not one. Despite their complicated relationship being the emotional crux of the film, it was absolutely cringeworthy and painful to watch and I was not invested in either of them. Part of that cringe was intentional, but I feel like that only makes it worse. It boggles my mind that Scott thought it was more important to depict Napoleon whining and stomping his feet because his wife wouldn't have sex with him NOW than his true military accomplishments or any of the major reforms he made to France as emperor.

This is an absolute joke of a Napoleon film that is so inaccurate and insulting to its subject that I can't even call it a biopic in good faith. I truly believe it was only made to tear down his image, and while I am all for depicting the flaws of historical figures, this was done insincerely here. Worst of all, it's not even entertaining to watch—the few battles were underwhelming and it felt like the film was mostly just dragging us through scene after scene with little connection in-between. I barely got by with the little knowledge of French history I had, I cannot imagine comprehending this film without any. Things just happen on-screen with little emphasis on their significance. It also does a bad job of depicting the passage of time, and sometimes I only realized years had passed between scenes because of a line or two of dialogue. Perhaps this is because of the hours of content that were cut out for the theatrical release, but the fundamental issues with this film make me believe that the director's cut will not be much better.

Do not watch this if you want a film that actually depicts Napoleon and his life. Watch this if you want to see a film that's "so bad it's funny" though the funny parts are few and the rest is just cringeworthy.

(I also have to point out how lazy and mismatched the soundtrack felt. Twice they used the iconic piano song "Dawn" that was ripped straight from the 2005 Pride and Prejudice film of all things. Having had to watch that movie countless times growing up because my older sister loved it to pieces, I instantly recognized the song and it took me out of the movie each time. That song is far too iconic and inherently linked with P&P and I'm not sure why the composer chose to use such a gentle, romantic tune for scenes with Napoleon and Josephine when their toxic relationship was nothing like Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy's. It just left me feeling like I could be watching a better film that actually makes me feel invested in their central pair.)

#jade speaks#jade reviews#?#yeah i have a letterboxd lol#don't review much cuz I'm too lazy but today's movie... my god#napoleon 2023

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear @faisonsunreve thanks for the tag. This was definitely a time taking task but so much fun to do. A true time travel to your watching history. To my surprise there are three French films and three Tom Hanks films included. 😄

A few comments about certain choices.

Favorite film of all time: The Thief of Bagdad (1940): The jewel of the film is Conrad Veidt’s insane Jaffar dressed up with the turban.

Best script: Some Like It Hot (1959): The story about two antihero musicians trying to make a living and avoiding gangsters by dressing as women and joining a female band and traveling to Miami is still unique to watch.

Favorite poster: The Empire Strikes Back (1980): Memories from the childhood. Darth Vader’s perhaps a little too epic posture promises you an emotional adventure and that promise will be fulfilled.

"I’ll watch it some day": Napoléon (1927): @missholson and I were introduced to this 6-hour biopic of Napoleon and we were stunned by the shots of the twenty-minute triptych sequence, where widescreen panorama is made by projecting multiple-image montages simultaneously on three screens. Blu-ray is waiting on the shelf.

Big personal impact: Elvis (2022): I wasn’t prepared for the narrative where female gaze and male vulnerability are allowed and validated.

You like, but everyone hates: Angels & Demons (2009): Don’t know today’s reception but when it was released the film was heavily criticized by the critics and the audience. I like both this and The Da Vinci Code (2006), but having more convincing characters, plot and hold for the entirety makes it better than the first one.

Underrated: The Ninth Gate (1999): Polanski is a very contradictory director for his sexual abuse charges, therefore it feels shameful to admit liking his films or considering his films to be valued. Many find Gate as a dull thriller. The film doesn’t rely on jump scares or gore but the mystery around the occult books and the things you can’t see.

"Why do I like this?": Bachelor Party (1984): This is my favourite question of them all. I discussed with @faisonsunreve about on what basis you should answer this and does it reveal your true movie taste. The 80’s crazy comedy is a silly and out-dated genre and that is why the films of this era fascinate me. Bachelor Party is full of lame humor and over-the-top characters. Yet the storyline is versatile and entertaining. Young Tom Hanks embodies the past.

Great soundtrack: La Cage aux Folles (1978): Ennio Morricone has said first he has to understand the film, the images, the story and the director’s intentions before starting to compose. I would like to know his study for Folles, because the soundtrack has such a humorous, characteristic and warm sound.

That cinematography: Furiant (2015): I was balancing between Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011) and La double vie de Véronique (1991), but this short film stands out with the way the rural landscapes, the dimly lit rooms and the unspoken moments are visualized (and edited) by the producer, director, writer, cinematographer and editor Ondřej Hudeček.

Criminally overlooked: Angélique film series (1964-68): Yes, you could put almost any Conrad Veidt film here, however I chose this. I have been fond of Angélique films since I was a child. These spectacles tell the story of Angélique in the time of King Louis XIV of France. Romance, adventure, scheming with breathtaking soundtrack and costume design, beautiful Michèle Mercier in the leading role and the flashy way of speaking French offer us an exquisite interpretation from the 60’s.

Favorite active director: Peter Strickland: I have seen only The Duke of Burgundy (2014) and Flux Gourmet (2022), nevertheless his style of using the aesthetics of Italian genre films and the intimacy he creates is just heartwarming.

Anyone who wants to make their own version, please do and let me know. 📼📀📦🔦

#favorite movie meme but different#the thief of bagdad#some like it hot#star wars#the empire strikes back#napoléon#elvis 2022#werk ohne autor#angels & demons#moulin rouge#the ninth gate#titanic#bachelor party#la cage aux folles#furiant#three men and a baby#drive#lord of the rings#bridget jones's diary#north by northwest#wax mask#angélique#under sandet#peter strickland#aladdin#the dark knight#personal#tag game#own edit#own post

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon Review

A look at the military commander's origins and his swift, ruthless climb to emperor, viewed through the prism of his addictive and often volatile relationship with his wife and one true love, Josephine.

I have been waiting since January of this year to talk about Ridley Scott, Napoleon, a biopic about the notorious French emperor who almost brought Europe to its knees. Outside of some alternate takes and different editing, it was relatively the same film. This did not surprise me, as I could not see what changes they could have made outside of adding 10+ hours of footage and turning it into a miniseries.

Napoleon is Ridley Scott at his best and worst. At 85 years old, Scott still knows how to make a stunning historical epic. The sweeping battles of the Napoleonic Wars are enthralling to watch on the big screen and are worth the price of admission alone. However, once the film gets outside of the battles you have a mess of a story that is riddled with all the standard issues of a biopic. Too much story to tell and not enough time to do it justice.

Napoleon’s life simply can not be compressed into 2.5 hours as it is far too vast and complicated. Because of this problem, the film either glosses over or boils many of his greatest victories and defeats into simple, one-sentence summaries. I wanted to see how Napoleon ticked and how his relationships between his military cabinet, politicians, and the public changed throughout the Napoleonic Wars. How did Napoleon brew up his military strategies and what led him to war? These elements and many more are never explored outside of a sentence stated here and there. Thus creating an uneven film.

However, the most disappointing element of the film was the short Frenchman himself. I understand this take on Napoleon was meant to tear down the mythological militant commander and show his true petty and egotistical colors. But I believe Scott takes this deconstruction too far as it makes you wonder how a pathetic manchild almost conquered all of Europe. The film forgets that Napoleon was a brilliant military strategist and a charismatic leader. They show these characteristics from time to time, but when he is a buffoon for the majority of it, it is hard to take him seriously.

I am unable to tell if this was due to the writing, acting, or both. The writing was obviously off, but I can’t help but think Joaquin Phoenix was miscast. He does a fantastic job with the material he is given, especially showing the Napoleon Complex, but he doesn’t feel like Napoleon. He comes across as a pathetic manchild rather than a brilliant military commander who has an ego problem. Sadly, the same can also be stated with Vanessa Kirby as Josephine. Her performance is outstanding, but she does feel miscast as the film greatly misunderstands the divorce between Josephine and Napoleon. If you were unaware, Josephine was 6 years older than Napoleon. So they either needed to age Kirby, like they did with Phoenix, or cast an actress who is a similar age to Phoenix. They divorced not because she couldn’t have children, but because she couldn't have children anymore. She was 54 when their marriage ended, meaning that her childbearing days were long gone. Gone even before Napoleon became emperor. So to cast a 35-year-old Vanessa Kirby as a post-menopausal woman is an insult to many middle-aged actresses in Hollywood who could have shown how tragic their divorce was.

With those complaints stated Napoleon is still a very entertaining film. As previously stated the battle scenes are spectacular to watch and are worth the price of admission alone. The film is surprisingly funny with slapstick humor and some funny quotes, even when it's unintentional. I look forward to the 4.5-hour director cut as it will most likely alleviate some of the complaints that I have with the theatrical cut. However, even 4.5 hours does not feel like enough time to do Napoleon's life justice.

My Rating: B-

#film#cinema#movies#movie#filmmaking#filmmaker#moviemaking#moviemaker#cinephile#film is not dead#film community#film review#movie review#film critic#movie critic#cinematography#film critique#napoleon#ridley scott#joaquin phoenix#vanessa kirby

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"EMILY" (2022) Review

"EMILY" (2022) Review

I have been aware of only four productions that served as biopics for the Brontë family. I have seen only three of these productions, one of them being a recent movie released in theaters last year. This latest movie, the first to be written and directed by actress Frances O'Connor, is a biopic about Emily Brontë titled "EMILY".

This 2022 movie began with a question. While Emily Brontë laid dying from tuberculosis, her older sister Charlotte asks what had inspired her to write the 1847 novel, "Wuthering Heights". The story flashed back to 1839, when Charlotte returned home to the Haworth parish in West Yorkshire to visit before her graduation from school. Emily attempts to re-connect with the older sister about her fictional works, but Charlotte merely dismisses her creations as juvenile activities. Around the same time, their father Patrick, the parish's perpetual curate receives a new curate name William Weightman. While Charlotte, younger sister Anne and several young women seem enamored of the handsome newcomer, only Emily is dismissive of him. Emily accompanies Charlotte to the latter's school to learn to become a teacher and their brother Bramwell goes to study at the Royal Academy of Arts. Both Emily and Branwell return shortly to Haworth after as failures. When Branwell manages to find a job as a tutor, the Reverend Brontë charges William to provide French lessons to Emily. What began as lessons in French and religious philosophy lessons, eventually evolves into a romantic entanglement between the pair.

"EMILY" managed to garner a good deal of critical acclaim upon its release in theaters, including four nominations from the British Independent Film Awards. It also won three awards at the Dinard British Film Festival: Golden Hitchcock, Best Performance Award for leading actress Emma Mackey and the Audience Award. I have no idea how much "EMILY" had earned at the U.K. box office. But in North America (the U.S. and Canada), it earned nearly four million dollars. Regardless of this . . . did I believe "EMILY" was a good movie? Did it deserved the accolades it had received not only from film critics, but also many moviegoers?

I cannot deny that the production values for "EMILY" struck me as first-rate. I believe Steve Summersgill did a first-rate job as the film's production designer. I thought he had ably re-created Britain's West Yorkshire region during the early 1840s with contributions from Jono Moles' art direction, Cathy Featerstone's set decorations and the film's art direction. Nanu Segal's photography of the Yorkshire locations created a great deal of atmosphere with moody colors that managed to remain sharp. I found myself very impressed with Michael O'Connor's costume designs. I thought he did an excellent job in not only re-creating fashions from the end of the 1830s to the late 1840s, he also ensured that the costumes worn by the cast perfectly adhered to their professions and their class, as shown below:

However, according to a relative of mine, Emily Brontë's fashion sense had remained stuck in the mid-to-late 1830s, something that the 2016 movie, "TO WALK INVISIBLE" had reflected. On the other hand, "EMILY" had the famous author wearing up-to-date fashion for someone of her class:

And I must admit that I found those moments featuring actress Emma Mackay wearing her hair down . . . in an era in which Western women did no such thing . . . very annoying. Otherwise, I certainly had no problems with the movie's production values. The movie also included a fascinating scene in which Emily had donned a mask and pretended to be the ghost of the Brontës' late mother during a social gathering. The scene reeked with atmosphere, emotion and good acting from the cast. I also found the scene well shot by O'Connor, who was only a first-time director.

"EMILY" also featured a first-rate cast. The movie featured solid performances from the likes of Amelia Gething as Anne Brontë, Adrian Dunbar as Patrick Brontë, Gemma Jones as the siblings' Aunt Branwell, Sacha Parkinson, Philip Desmeules, Veronica Roberts and other supporting cast member. I cannot recall a bad performance from any of them. The movie also featured some truly excellent performances. One came from Fionn Whitehead, who gave an emotional performance as the Brontë family's black sheep, who seemed overwhelmed by family pressure to succeed in a profession or the arts. Alexandra Dowling gave a subtle, yet charged performance as Charlotte Brontë, the family's oldest sibling (at the moment). Dowling did an excellent job of conveying Charlotte's perceived sense of superiority and emotional suppression. I wonder if the role of William Weightman, Reverend Brontë's curate, had been a difficult one for actor Oliver Jackson-Cohen. I could not help but notice that the role struck me as very complicated - moral, charming, intelligent, passionate and at times, hypocritical. Not only that, I believe Jackson-Cohen did an excellent job of conveying the different facets of Weightman's character. The actor also managed to create a dynamic screen chemistry with the movie's leading lady, Emma Mackey. I discovered that the actress had received a Best Actress nomination from the British Independent Film Awards and won the BAFTA Rising Star Award. If I must be honest, I believe she earned those accolades. She gave a brilliant performance as the enigmatic and emotional Emily, who struggled to maintain her sense of individuality and express her artistry, despite the lack of support from most of her family.

"EMILY" had a great deal to admire - an excellent cast led by the talented Emma Mackey, first-rate production designs, and costumes that beautifully reflected the film's setting. So . . . do I believe it still deserved the acclaim that it had received? Hmmm . . . NO. No, not really. There were two aspects of "EMILY" that led me to regard it in a lesser light. I thought it it was a piss poor biopic of Emily Brontë. I also found the nature of the whole romance between the author and William Weightman not only unoriginal, but also unnecessary. Let me explain.

As far as anyone knows, there had been no romance - sexual or otherwise - between Emily Brontë and William Weightman. There has never been any evidence that the two were ever attracted to each other, or one attracted to the other. Many have discovered that the youngest Brontë sister, Anne, had been attracted to Weightman. In fact, she had based her leading male character from her 1947 novel, "Agnes Grey", on the curate. There have been reports that Charlotte had found him attractive. But there has been no sign of any kind of connection between him and Emily. Why did Frances O'Connor conjure up this obviously fictional romance between the movie's main character and Weightman. What was the point? Did the actress-turned-writer/director found it difficult to believe that a virginal woman in her late 20s had created "Wuthering Heighs"? Did O'Connor find it difficult to accept that Emily's creation of the 1847 novel had nothing to do with a doomed romance the author may have experienced?

Despite Mackey's excellent performance, I found the portrayal of Emily Brontë exaggerated at times and almost bizarre. In this case, I have to blame O'Connor, who had not only directed this film, but wrote the screenplay. For some reason, O'Connor believed the only way to depict Brontë's free spirited nature was to have the character engage in behavior such as alcohol and opium consumption, frolicking on the moors, have the words "Freedom in thought" tattooed on one of her arms - like brother Branwell, and scaring a local family by staring into their window at night - again, with brother Branwell. This is freedom? These were signs of being a "free spirit"? Frankly, I found such activities either immature or destructive. Worse, they seemed to smack of old tropes used in old romance novels or costume melodramas. In fact, watching Emily partake both alcohol and opium reminded me of a scene in which Kate Winslet's character had lit up a cigarette in 1997's "TITANIC", in order to convey some kind of feminist sensibility. Good grief.

What made O'Connor's movie even worse was her portrayal of the rest of the Brontë family. As far as anyone knows, Reverend Brontë had never a cold parent to his children, including Emily. Emily had not only been close to Branwell, but also to Anne. And Branwell was also close to Charlotte. All three sisters had openly and closely supported each other's artistic work. Why did O'Connor villainize Charlotte, by transforming her into this cold, prissy woman barely capable of any kind of artistic expression? Why have Charlotte be inspired to write her most successful novel, "Jane Eyre", following the "success" of "Wuthering Heights", when her novel had been published two months before Emily's? Why did she reduce Anne into the family's nobody? Was it really necessary for O'Connor to drag Charlotte's character through the mud and ignore Anne, because Emily was her main protagonist? What was the damn point of this movie? Granted, there have been plenty of biopics and historical dramas that occasionally play fast and loose with the facts. But O'Connor had more or less re-wrote Emily Brontë's life into a "re-imagining" in order to . . . what? Suggest a more romantic inspiration for the creation of "Wuthering Heights"?

I have another issue with "EMILY". Namely, the so-called "romance" between Brontë and Weightman. Or the illicit nature of their romance. Why did O'Connor portray this "romance" as forbidden? A secret? I mean . . . why bother? What was it about the pair that made an open romance impossible for them? Both Brontë and Weightman came from the same class - more or less. Weightman had been in the same profession as her father. And both had been college educated. Neither Emily or Weightman had been romantically involved in or engaged to someone else. In other words, both had been free to pursue an open relationship. Both were equally intelligent. If the Weightman character had truly been in love with Emily, why not have him request permission from Reverend Brontë to court her or propose marriage to Emily? Surely as part of the cleric, he would have considered such a thing, instead of fall into a secretive and sexual relationship with her. It just seemed so unnecessary for the pair to engage in a "forbidden" or secret romance. Come to think of it, whether the film had been an Emily Brontë biopic or simply a Victorian melodrama with fictional characters, the forbidden aspect of the two leads' romance struck me as simply unnecessary.

What else can I say about "EMILY"? A rich atmosphere filled the movie. The latter featured atmospheric and beautiful images of West Yorkshire, thanks to cinematographer Nanu Segal. It possessed a first-class production design, excellent costumes that reflected the movie's 1840s setting and superb performances from a cast led by the talented Emma Mackey. I could have fully admired this film if it were not for two aspects. One, I thought it was a shoddy take on a biopic for author Emily Brontë that featured one falsehood too many. And two, I found the secretive and "forbidden" nature of Brontë's false romance with the William Weightman character very unnecessary. Pity.

#emily 2022#frances o'connor#emily bronte#bronte sisters#charlotte bronte#anne bronte#emma mackey#oliver jackson cohen#william weightman#wuthering heights#fionn whitehead#branwell bronte#adrian dunbar#gemma jones#alexandra dowling#amelia gething#sacha parkinson#philip desmeules#veronica roberts#gothic romance#period drama#period dramas#costume drama

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Zone of Interest: The Banal Dreams of Nazi Settler Colonialism”

In Jonathan Glazer's Oscar-Winning Movie, You Do Not See Auschwitz the Camp; You See Auschwitz the Colony. Neither Exists Without the Other

— Hazem Fahmy | 11 March 2024 | Middle East Eye

English Director Jonathan Glazer Poses with the Oscar for Best International Feature Film for "The Zone of Interest" during the 96th Annual Academy Awards on 10 March, 2024 (AFP)

In the 1965 Soviet Film Ordinary Fascism, Also Known as Triumph Over Violence, director Mikhail Romm’s voiceover implores the viewer to pay attention to the petit-bourgeois quality of fascism in general, and Nazism in particular.

Over archival footage of German small-business owners leaving their stores in uniform and hopping onto bicycles, he remarks, almost comically: "Here is a butcher, and there goes a baker." This brief scene succinctly captures Hannah Arendt’s (by now highly cliched) notion of the "banality of evil", a phrase she coined while covering the trial of Adolf Eichmann, known as the "architect of the Holocaust".

But Arendt’s own refusal to interrogate the inherently colonial nature of European fascism, a refusal inseparable from her own racism and western chauvinism, has blunted the sharpness of that term’s capacity for critical insight. Yes, the Holocaust was engineered by middle managers, but to what end? What did they get out of the horrific affair, besides satiating their sadism?

A simple answer is Jonathan Glazer’s Academy Award-winning film,The Zone of Interest: land - more specifically, enough land to replicate the expansionism of American manifest destiny, to recreate the German Aryan into the fascist ideal of the Ubermensch.

Over the weekend, the film won the Oscar's best international film award. In his acceptance speech, Glazer told the audience: "Right now we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people, whether the victims of October 7 in Israel or the ongoing attack in Gaza."

The story follows the mundane domestic lives of Rudolf Hoss (Christian Friedel), the longest-serving commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, and his wife and children, as they go about their days in their idyllic house adjoining the camp grounds.

As the primary subject is the Holocaust, the film has been widely noted for its refusal to visually depict any of the atrocities that occurred within the camp, though the audience frequently hears gunshots and screams from over the wall. This bold narrative and political choice has been consistently misread in mainstream film criticism as a simple affirmation of Arendt’s limited perspective on the "banality of evil".

It is far too simplistic to describe the film as a truncated biopic of its subject, nor is it accurate to reduce it to a formal experiment; a film about the Holocaust in which you do not see the Holocaust. In other words, The Zone of Interest is not simply a film about the Nazi official as a middle manager, but is much more importantly a film about the Nazi official as a settler.

Cartoon Villains

Since 1939, mainstream western education, media, and discourse about World War II and the Holocaust have strived to depict Nazism as a catatonic movement of unbridled hate, rather than a settler-colonial one in continuum with those of other western powers.

Nazis tend to be portrayed as larger-than-life cartoon villains, rather than quite ordinary monsters, easily comparable to their colonial brethren in the Belgian Congo, French Algeria or British India, among countless other places around the world that have had the misfortune of experiencing western occupation and colonialism.

youtube

Writers and scholars from across the Third World have, of course, long questioned this narrative. One of the most notable and succinct critiques was levied by Aime Cesaire in his Discourse on Colonialism.

But such perspectives have been uncommon within the US. With the exception of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, which has frequently been criticised for oversimplifying the primary terms of its investigation, writing on the intimate connections between western, and very specifically American, colonialism and Nazism is often marginalised. Scholars such as Carroll P Kakel and Edward B Westermann are few and far between.

The beauty of these scenes begs the (rhetorical) question: what is the difference between Hoss's family and that of any other frontiersman?

This connection is laid bare in The Zone of Interest, both visually and politically.

The amount of screen time dedicated to the lush vistas of the Nazi-occupied Polish countryside, in which Hoss and his family hike, swim and play, evokes the frontier romanticism of classic western films such as The Naked Spur, Shane and Johnny Guitar.

Being Hollywood productions, these stories, of course, implore the viewer to identify with the settlers’ yearning for the vast landscapes they seek to conquer and rid of their indigenous inhabitants.

In The Zone of Interest, the gaze is identical, but it is now one of a Nazi as opposed to that of a noble American pioneer. The beauty of these scenes begs the (rhetorical) question: what is the difference between Hoss’s family and that of any other frontiersman?

Pivotal Scene

Glazer’s identification of Poland as a frontier for Nazi German expansion is one shared unambiguously by his characters. In a pivotal scene, Hoss and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Huller) argue as to whether they should leave Auschwitz. He has been reassigned elsewhere by his higher-ups and his instinct, as that of any family man, is to take his wife and children with him.

But Hedwig refuses: “Your work is in Oranienburg now. Mine is raising our children.” When he insists, she delivers the final blow: “This is our home. We’re living how we dreamed we would since we were 17 - beyond how we dreamed. Out of the city finally. Everything we want, on our doorstep. And our children strong and healthy and happy. Everything the Fuhrer said about how we should live is exactly how we do. Drive east, Lebensraum. Here it is.”

Hedwig’s impassioned plea emphasises what the vast majority of western media narratives seek to suppress: that genocidal fascist projects are always about reproduction as much as they are about destruction. This is why Lebensraum, German for "living space", is so seldomly discussed in mainstream depictions of the Holocaust.

The Nazis’ ideology of eastward settler expansion did not simply echo American manifest destiny, but considered it a blueprint. This is why the robotically repeated line that the film is about not depicting, or “looking away” from Auschwitz is patently false. You do not see Auschwitz the camp. You see Auschwitz the colony. Neither exists without the other.

Ironically, and despite being the only filmmaker at the 96th Academy Awards to explicitly acknowledge the situation, Glazer himself apparently failed to see the resonance of his own work to the ongoing Israeli genocide in Gaza. In multiple interviews, he has responded meekly when asked about Israel’s mass slaughter and starvation of Palestinians since 7 October, with a shallow lamentation for “both sides”. He repeated this liberal sentiment during his acceptance speech for Best Foreign Language Film, ignoring how the Hoss family has been reborn time and time again in Sderot and Ashkelon and all the other settlements of the so-called Gaza envelope.

Anyone uncomfortable with such comparisons needs only to listen to the words of Israeli leaders speaking of Auschwitz as their end goal for Gaza. I wish Glazer had done so, rather than fall into the tired old trap his own work so brilliantly escapes.

When it comes to colonialism, what most urgently demands our attention is not the banality of evil, but the evil of banality.

#Youtube#Middle East Eye 👁️#The Zone of Interest#The Banal Dreams#Nazi Settler Colonialism#Jonathan Glazer#Winner of Oscar for Best International Feature Film#English Director#96th Annual Academy Awards#Hazem Fahmy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Light's Out!!

“Cinema”, the word itself is derived from the Greek word “kinema”, meaning movement, short for the French word cinematographer, coined by two brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere. But in today’s time the word may beg to differ. It has different characteristics after all. In the 19th century the Lumiere brothers captured and demonstrated their first work in 1893 in Paris France which was a huge success, and after that, people from all around the world tried to capture and present their work and it was the start of what we call nowadays FILMMAKING. At this point we have numerous amounts of categories of filmmaking for e.g. (T.V, streaming series, AR-VR, movies).

The cinematic language can express as many emotions as human beings consist of. Can show sorrow/joy in the form of poetry, shows how a simple shot can impact a life of a human being so easily. People who are very much engaged in films are now termed as CINEPHILE. From shooting in analogue camera to Imax 4d, we’ve certainly come a long way and our audience has changed accordingly from time-to-time shaking hands with technology in a peaceful way. Well it is said that every single thing has its pros and cons , talking about the pros the films we watch today are more of clear vision and we can see many unreal things , thanks to computer graphics , but the cons are as sad as the pros are as good, film in today’s date has occupied a commercial base rather than just showcasing art , it has created a certain level for the coming audiences, that many people refuse to watch films made in the 70s,80s, which showed real things and gave a message in the end , but nowadays people refuse to watch real topic films, as they are more engaged towards things to do with computer graphics. People are also very much considering this as a profession and some of them are really in this field to showcase what they think film as an art. There are as many legends as possible in this field, but the missing point here is that this field is very massive, talking about (directors, actors, cinematographers, screenwriters, editors, etc.). some of the greatest directors to ever exist are, Satyajit Ray, Martin Scorsese, Akira Kurosawa, Stephen Spielberg etc. and talking about actors the list is never-ending, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Tom Hanks, Leonardo Dicaprio, Tom Cruise, etc

There are many films which are good but there are less films which are great, and by great, I mean great in everything in everything, the direction, the script, the acting, and the reality of the film. For e.g. The godfather trilogy is considered as one of the greatest movies of all time, it is said that many film schools teaches that movie to the students pursuing filmmaking as their career and the first Indian movie which got the attention of the west was Pether Panchali by Satyajit Ray.

Even the Bollywood is progressing now, some newly directors are bringing back the actual reality in films, with real topics like Masan by Neeraj Ghayan is an actual depiction of what a real heartbreak a person can go through.

And the very recent blockbuster, biopic of J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER. Well, it is a big hit in the country, not because of the story but because of the director which is said to be Christopher Nolan. It is becoming a matter of great pride that most of our audiences are getting to know great films.

Now we can say we have come a long way.

PHOTO CREDITS-

@la_photolover

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Cillian Murphy is getting noted for his role of J. Robert Oppenheimer in the film Oppenheimer and he is looking very promising in the role. He is all geared for the big release and for the promotion of the film.

Murphy was born on 25 May 1976 in Douglas, Cork. His mother taught French while his father, Brendan, worked for the Department of Education. His grandfather, aunts, and uncles were also teachers. He was raised in Ballintemple, Cork he had two sisters and one brother. He started writing and performing songs at the age of 10. He was raised Catholic and attended the fee-paying Catholic secondary school Presentation Brothers College, where he did well academically but often got into trouble, sometimes being suspended; he decided in his fourth year that misbehaving was not worth the hassle. Not keen on sports, which was a major part of the school’s curriculum, he found that artistic pursuits were neglected at the school.

Murphy did his first performance in secondary school when he participated in a drama module presented by Corcadorca Theatre Company director Pat Kiernan. Novelist William Wall, who was his English teacher, encouraged him to pursue acting but he was set on becoming a rock star. In his late teens and early 20s, he sang and played the guitar in several bands alongside his brother, Páidi, and the Beatles-obsessed duo named their most successful band The Sons of Mr. Green Genes, which they adopted from the Frank Zappa song of the same name. They were offered a five-album deal by Acid Jazz Records, which they rejected because Páidi was still in school and the duo did not agree with the small amount of money they would get for giving the record label the rights to Murphy’s compositions.

Murphy began studying law at University College Cork (UCC) in 1996 but failed his first-year exams because he was busy with his band, but he knew within days after starting at UCC that law was not what he wanted to do. After seeing Corcadorca’s stage production of A Clockwork Orange, directed by Kiernan, acting began to garner his interest. His first major role was in the UCC Drama Society’s amateur production of Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, which starred Irish-American comedian Des Bishop.

He made his professional debut in Enda Walsh’s 1996 play Disco Pigs and in the 2001 screen adaptation of the same name. His early notable film credits include the horror film 28 Days Later (2002), the dark comedy Intermission (2003), the thriller Red Eye (2005), the Irish war drama The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006), and the thriller Sunshine (2007). He played a transgender Irish woman in the comedy-drama Breakfast on Pluto (2005), which earned him a nomination for a Golden Globe Award.

Murphy began collaborating with filmmaker Christopher Nolan in 2005, playing Scarecrow in The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005–2012) as well as appearing in Inception (2010) and Dunkirk (2017). He gained prominence for his role as Tommy Shelby in the BBC period drama series Peaky Blinders (2013–2022) and for starring in the horror sequel A Quiet Place Part II (2020). In 2023, he starred as J. Robert Oppenheimer in Nolan’s biopic Oppenheimer.

In 2011, Murphy won the Irish Times Theatre Award for Best Actor and Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Solo Performance for the one-man play Misterman. In 2020, The Irish Times named him one of the greatest Irish film actors.'

#Cillian Murphy#Oppenheimer#Misterman#Peaky Blinders#Christopher Nolan#A Quiet Place Part II#Inception#Dunkirk#The Dark Knight Trilogy#Scarecrow#Sunshine#Breakfast on Pluto#Golden Globe#Red Eye#The Wind That Shakes The Barley#Disco Pigs#28 Days Later#Intermission#The Sons of Mr. Green Genes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghosted (2023) Review

Adrien Brody’s crappy French accent in this movie I could have forgiven, if only I haven’t seen John Wick: Chapter 4 a couple of weeks ago where I experienced the most delightful Parisian mouthing of Bill Skarsgard’s villain, so now Brody’s French-ish slur sticks out like a sore thumb. And boy is this one sore thumb. Everything is not j’aime up in this joint.

Plot: Cole falls head over heels for enigmatic Sadie, but then makes the shocking discovery that she's a secret agent. Before they can decide on a second date, Cole and Sadie are swept away on an international adventure to save the world.

This is the third time Chris Evans and Ana de Armas are co-starring in a film together, following the fantastic murder mystery Knives Out and the Netflix action film The Gray Man. As such this pairing on paper seems like a natural one, however upon seeing the new Ghosted film on Apple TV+ I have made quite the peculiar discovery - these two have absolutely zero chemistry. I mean none whatsoever. All their flirting comes of as cringeworthy, the romance is none existent and I didn’t buy into their relationship whatsoever. Their kissing scenes reminded me of that Andrew Garfield/Emma Stone SNL sketch where they don’t know how to kiss on camera. It was just awkward. And when in a rom-com your central couple have no chemistry, well then the movie is doomed to fail as is. Also, talk about a miscast! Chris Evans is supposed to play a farmer boy with an inhaler having an innocent outlook on life, yet it’s so hard not to see him as the alpha male, as such making his casting very questionable. Ana de Armas is usually a likeable presence, however, again, here is very bland and forgettable. And wears a wig. A very obvious wig, made the more obvious by the Twitter community, so thank you guys. It’s a shame really, as one could have easily done a trashy silly spy rom-com with A-list actors. Just look at Mr & Mrs Smith - an absolutely stupid movie but its hard to deny the sex appeal of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie together... though obviously that hasn’t aged too well but back then they were fire!

There’s a lot of talent involved behind the camera here. Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick who are known as the writers of the very successful and entertaining Deadpool movies have story credits here, and Dexter Fletcher is in the director’s chair. Evidently all three must have been undergoing some kind of collective erectile dysfunction causing their creative juices to dry out like water in a desert, as this movie consists of all the possible Hollywood plot cliches imaginable, with a painfully unfunny script, boring direction and general nonsense. Fletcher is fresh off the heels of his previous directorial outing with the Elton John biopic Rocketman that was visually filled with colour and charm, yet here the directing is so shallow and plain. So uninspired. As for the action sequences, they are there I guess. There’s a somewhat passable fight/chase on a bus, but even then, all those stunts you would have seen before.

Ghosted would have been a perfectly acceptable affair back in the early 2000s, however in 2023 it is simply ticking off every generic cliché of a Hollywood action film, only not anywhere as good as the movies its ripping off, nor that funny either. There’s even a few pointless cameos thrown in, and I do mean pointless. So in a nutshell, not worth getting Apple TV+ for anyway, however if you’re wondering about that streaming service, there is a delightful movie about the backstory of Tetris that came out on there recently starring Taron Egerton, and that’s actually much more interesting.

Overall score: 3/10

#ghosted#2023#action#romance#comedy#adventure#spy#movie#film#movie reviews#film reviews#ghosted review#2023 in film#2023 films#chris evans#ana de armas#adrien brody#dexter fletcher#paul wernick#rhett reese#apple#apple tv#apple tv+#streaming#mike moh#amy sedaris#tate donovan#ryan reynolds#anthony mackie#john cho

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mads poll with a difference!

A poll of Mads Mikkelsen movies where the selection is based on range of factors, including but not limited to: genre, writer/director, country of release, date of release and 🎉vibes 🎉

Some of the movies may fit in more than one category, so vibes have mostly informed those decisions.

Round One:

Choose your fave!

First, starting off with Mads in a supporting role.

I Am Dina is a 2002 Norweigian-Swedish-Danish film. Set in the 1860s, it's about a girl - Dina - who accidentally causes her mother's death. Mads plays Niels, the stepson of Dina's husband and a total dick.

Torremolinos 73 is a 2003 Spanish-Danish comedy. Set in 1973, Alfredo and his wife Carmen's change in financial circumstances results in them publishing and distributing pornographic movies. Mads plays Magnus, a virile young porn star.

Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself is a 2002 Danish-Scottish dramedy-romance. Harbour, and his suicidal brother Wilbur, inherit a bookshop, and romance changes Wilbur's life. Mads plays Dr Horst, Wilbur's psychologist who suspects Harbour has a serious illness.

At Eternity's Gate is a 2018 French-UK-US biopic of the painter Vincent van Gogh, chronicling his final years. Mads plays a priest at the mental asylum where van Gogh is placed after cutting off his ear.

Cast your votes on this serious matter!

#mads mikkelsen#i am dina#torremolinos 73#wilbur wants to kill himself#at eternity's gate#tumblr polls#my polls

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gladiator II: Fact vs. Fiction

Fact and Fiction in Gladiator II: Those Who Are About to Lie Salute You Remember when Ridley Scott’s 2023 biopic Napoleon set off a firestorm among finicky French historians? How shocked, shocked they were by the film’s factual inaccuracies (zut alors, Bonaparte never led the charge at Waterloo!). Well, it looks like the 86-year-old Oscar-winning director is at it again (see page 56), only this…

0 notes

Text

Anouk Aimée

Elegant French film actor best known for her roles in the classic films A Man and a Woman, Lola, and La Dolce Vita

Show-business history records how the young Françoise Sorya was walking with her parents in Paris when they were approached by the director Henri Calef, who asked whether the teenager could play a part in his forthcoming production La Maison Sous la Mer (1947). The answer was yes and Françoise took the professional name Anouk after the character she was to play.

A short while later, she accepted a part in La Fleur de l’Age and its director, Marcel Carné, added Aimée to her chosen name. In the event the film was not completed, but its writer, Jacques Prévert, had been captivated by the beauty and natural talent of the young actor and wrote a screenplay indebted to Romeo and Juliet for her. As a result, Anouk Aimée, who has died aged 92, took the role of Juliette in The Lovers of Verona (1949).

The success of the movie launched her career, which included some 70 feature films, stage work and a handful of TV movies and miniseries. Her greatest successes were La Dolce Vita (1960), Lola (1961) and A Man and a Woman (1966), for which she won a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination, but she chose work erratically and happily sacrificed her career for a private life that included an absence from the screen during the first six years of her marriage to the actor Albert Finney.

Daughter of Geneviève (nee Durand), who acted under the name Geneviève Sorya, and Henri Dreyfus, also an actor, she was born in Paris. During the occupation, her parents moved her to the country for safety and she used her mother’s name rather than that of her Jewish father. He later changed his name to Henry Murray.

Aimée studied both drama and dance before her first starring role in The Lovers of Verona, as the would-be actor Juliette, who, while working as an understudy, meets and falls tragically in love with a set carpenter (Serge Reggiani). That success took her to Britain for a part opposite Trevor Howard in The Golden Salamander (1950). Although she was well received in the rather dull film, she subsequently married the Greek director Nico Papatakis and had a daughter, and did not appear on screen again until The Crimson Curtain (1953).

This was a stylishly made period romance, adapted by the writer Alexandre Astruc from a short story as his directorial debut. Despite a duration of 43 minutes and narration rather than dialogue, it proved a critical success. Aimée, cast as a young woman with heart problems who sacrifices herself for her lover, embarked on a busy international career.

She played a prostitute, Jeanne, in an adaptation of a Georges Simenon story, The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By (aka The Paris Express, 1952); co-starred in a somewhat pretentious thriller, Bad Liaisons (1955), directed by Astruc; and played a small role in Lovers of Paris (1957), which starred Gérard Philipe, France’s leading romantic actor.

She was invited to play opposite him in Jacques Becker’s Montparnasse 19 (1958), a biopic of Modigliani in which she took the role of the woman who eventually married the artist. She moved straight to another prestige production for Georges Franju, The Keepers (1959), playing a woman who tries to help a young man wrongly committed to a psychiatric hospital by his father. In Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, starring Marcello Mastroianni, she had the powerful role of a jaded socialite and found in the director a new freedom and vitality that kept her working in Italy for much of the next six years.

However, her best role was in Lola, Jacques Demy’s enchanting debut, dedicated to Max Ophuls and romantic cinema, which it affectionately satirised. Aimée as the not very talented singer waiting for her sailor lover to return made the character, in top hat and feather boa, vivacious yet vulnerable. Sadly, most of the other films in this period were less distinguished, and only Fellini’s 8½ (1963) placed her in a quality movie, as Mastroianni’s girlfriend.

She received the greatest popular acclaim of her long career in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman. It took the Oscar as best foreign film, and the Cannes festival award as best film, with an Oscar nomination for Aimée as best actress. She did not win, but there was compensation in receiving the equivalent award from Bafta, a Golden Globe and starring in a huge box office hit. Its success led to a sequel, A Man and a Woman – Twenty Years Later (1986).

After starring in the elegant and mysterious Un Soir, Un Train (1968) for the Belgian director André Delvaux, she again played Lola, in Model Shop (1969), which marked Demy’s American debut. The film flopped, not least because Aimée seemed uninterested and unengaged by her role.

The same could be said of The Appointment and Justine (both 1969). The former was a misguided project by the New Yorker Sidney Lumet and suffered from an arty pseudo-European “sophistication” that alienated audiences. Justine was taken over by George Cukor early in the shooting. The director, famous for his rapport with female actors, later remarked that it was his only experience working with “somebody who didn’t try”. It was a commercial failure.