#Fourth Sunday in Lent

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pretzel Sunday

Pretzels, with their salty and twisty goodness, are a delicious way to enjoy a snack that can be delightfully basic or creatively complex.

Pair a soft pretzel with a bit of mustard or some squeezy cheese, or dip some crunchy pretzel in a caramel sauce for that sweet and savory combo. No matter how they are enjoyed, the guest of honor is always tasty. It’s time for Pretzel Sunday!

In its native German, Pretzel Sunday is called “Bretzelsonndeg”, and this traditional day is notable because it lands right at the center of the religious season of Lent.

History of Pretzel Sunday

Pretzels date back hundreds of years, with some historians believing that the first pretzels were created by monks in either Northern Italy or Southern France in the 7th century AD. These pretzels were probably made from scraps of dough that were left over after the bread-making process. The legend has it that the long strips of pretzel dough were twisted around and across to symbolize the shape of a child’s arms that were folded in prayer. Another story goes that the religious symbolism is also related to the three holes representing the three persons of the Christian trinity.

Particularly celebrated in the small European country of Luxembourg, Pretzel Sunday is a celebration of love that falls on the fourth Sunday of Lent. Lent takes place for the days prior to Easter (not counting Sundays) and is a time of fasting for those in the Christian faith. Pretzel Sunday is an exciting time that marks the halfway point between the beginning of the Lenten Season and the end.

Pretzel Sunday comes from a fun folk custom that originated in Luxembourg where the tradition is that boys are invited to present girls they like with a pretzel. This type of pretzel might be a slightly sweeter version that is made from puff pastry, covered in fondant icing and topped off with sliced almonds.

Then, if the girl likes the boy in return, she is invited to reciprocate by giving the boy a decorated egg a few weeks later, on Easter Sunday. In a more disappointing turn of events, if she is not interested in him, the girl will give him an empty basket as a sign that he should look elsewhere for love.

This exchange is a delightful tradition that brings lots of fun and affection, even for married couples who participate. And in leap years? The roles are reversed so that the girl gives the sweet pretzel on Pretzel Sunday and boys have the option to give an egg or an empty basket on Easter.

Today, Pretzel Sunday can be enjoyed and celebrated by anyone, whether using it for that special someone or simply by giving away pretzels to those who are loved!

Pretzel Sunday Timeline

610 AD

Pretzels are created

The story goes that pretzels are created by monks either in Italy or France.

1710

Pretzels make it to the US

German immigrants bring pretzels to Pennsylvania.

1861

First commercial pretzel bakery in the US

Julius Sturgis founds his pretzel bakery in Lititz, Pennsylvania.

1988

First Auntie Anne’s Pretzel’s opens

In Downington, Pennsylvania, Auntie Anne’s is opened in a farmers’ market, and this will eventually become the largest pretzel chain in the United States.

How to Celebrate Pretzel Sunday

Have tons of fun celebrating this delightful day with some traditional customs or new activities. Mark Pretzel Sunday by enjoying the day in some of these ways:

Give a Pretzel to Your Sweetie

Pretzel Sunday is a great time to keep the Luxembourg tradition alive by offering a sweet, soft pretzel to the person you love. Though it is specifically meant to be the boy giving the pretzel to the girl, it’s certainly okay for a girl to break tradition and gift a pretzel to the boy she loves.

Of course, modern times can mean modern traditions, and it might be fun to spread the wealth from just romantic love and, instead, give out delicious soft pretzels to anyone that is loved!

Try Making Soft Pretzels

One fun and tasty way to enjoy celebrating Pretzel Sunday might be to learn how to make these yummy treats at home. Choose a recipe that is made from puff pastry reminiscent of the traditional Luxembourg style, complete with fondant icing and sliced almonds. Or try out a salty soft pretzel recipe that can be enjoyed with more savory dips. In any case, get creative in the kitchen in honor of this excellent day!

Take a Trip to Luxembourg

Because the Pretzel Sunday tradition originated in the European country of Luxembourg, this might be a great time to plan a trip to visit this unique and interesting country. Luxembourg is nestled just between the countries of France, Germany and Belgium. The main city and capital of this small nation is Luxembourg City, which is located in the south central portion of the country.

Visitors to Luxembourg can enjoy a variety of sights, ancient castles, and architecture, as well as beautiful natural scenery. In addition, the country has a unique blend of cultures and holds three national languages: French, German and the national language that is called Luxembourgish. Many people there also can speak English very well, so it’s a great place for people all over the world to visit!

Get Creative with Eating Pretzels

Enjoy Pretzel Sunday by enjoying some unique and creative ways to eat pretzels. For instance, pretzel dough can be made into buns and eaten with burgers or chicken patties to create a delicious sandwich. Or, use some savory dips such as hummus, mustard dip or guacamole to make a delicious and somewhat healthy snack. Or they can even be enjoyed when made into mini cheese ball bites.

Of course, it would certainly also be a smart way to go to make pretzels into some sweet, dessert style snacks. Cover them in a sweet yogurt frosting. Crunch them up and put them in ice cream. Or make them into caramel and chocolate turtles for a tasty treat.

Throw a Pretzel Sunday Party!

Perhaps a new and fun way to celebrate Pretzel Sunday would be to host a little party for family and friends. Invite guests to bring their favorite type of pretzels, whether soft or crunchy, and then have a gathering of dips, spreads and sauces to enjoy them with. Use some of the ideas from above to serve pretzels in a myriad of sweet and savory ways.

Pretzel Sunday FAQs

Are pretzels healthy?

Pretzels can be low in fat, but they don’t have any nutrients and they can raise the blood sugar, so they’re not a highly healthy snack.

Can dogs eat pretzels?

A pretzel or two won’t hurt a dog, but the high sodium could be problematic.

How to make soft pretzels?

Making homemade soft pretzels requires flour, salt, water, yeast, eggs and a few other ingredients. Mix, let rise, bake and enjoy!

Are pretzels gluten free?

Pretzels are typically made with flour which means they contain gluten.

Can pretzels go bad?

Yes, after the bag is opened, pretzels will remain fresh for about 1-2 weeks.

Source

#Pretzel Sunday#street food#Boston#USA#Massachusetts#New England#original photography#summer 2018#travel#vacation#Freedom Trail#cityscape#Old State House#architecture#national day#Pretzel#landmark#tourist attraction#Bretzelsonndeg#Fourth Sunday of Lent#10 March 2024#Pretzel Crusted Chicken

0 notes

Text

03/08/2024

If that word was made flesh, I'd punch it.

___

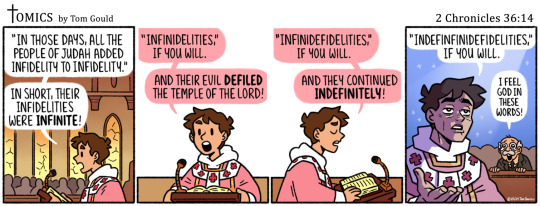

JOKE-OGRAPHY: 1. The priest, Fr. Mark, is giving a homily during Laetare Sunday (the fourth Sunday of Lent, and a day when priests wear rose-colored vestments). He notes that, in the first reading, the infidelity of the people of Judah seems infinite, and it defiles their places of worship, and it continues indefinitely. Because the words "infidelity," "infinite," "defile," and "indefinitely" share many letters and sounds, Fr. Mark starts combining the words together to make hip new words which contain all of their meanings at once. The evolution of this new word goes thuswise and whenceforth: 1a. INFIDELITY (in-fi-del-i-ty): unfaithfulness. 1b. INFINIDELITY (in-fin-i-del-i-ty): infinite unfaithfulness. 1c. INFINIDEFIDELITY (in-fin-i-def-i-del-i-ty): infinite unfaithfulness which defiles. 1d. INDEFINFINIDEFIDELITY (in-def-in-fin-i-def-i-del-i-ty): infinite unfaithfulness which defiles and continues indefinitely. Indef(inite) + infini(te) + defi(le) + (infi)delity. 2. Once the ultimate form of the priest's new word is complete and the heroes can no longer stop it's godless birth, one of the parishioners declares that he feels God in the priest's word. Is this out of genuine religious ecstasy, or out of fear that the new word will destroy everyone who resisted it when it gains sentience? That, I leave for the scholars to decide.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: This is yet another "Tomics Resurrection," where I've taken an old cartoon and, much like the priest, remade it with all the hubris I can muster. The old cartoon only combined "indefinite," "infinite," and "infidelity." In this new version, I added "defile" to the mix, because that's also in the verse, and contains several of the same letters as the rest of the victims of my chimeric abomination. Ironic, isn't it? That I would defile the English language further than ever by using that very word. But I'm a scientist, after all. The opportunity was there, so I took it, even if it was taboo. I can almost hear it murmuring, "Ed...ward?"

#catholic#christian#jesus#comic#cartoon#catholic memes#jesus memes#christian memes#tomics#bible#priest#laetare sunday#rose#tomics comics#tom gould#indefinfinidefidelity#ed...ward#roko's basilisk

301 notes

·

View notes

Note

This seems really indulgent and I know (and love!) footy au so no pressure at all but -- more butch Bea? Would make my day anytime, whatever you might have in mind! :) Thank you for your words

[i love indulgence, here's what was supposed to be one scene & ended up being 8.4k words about how remarkable it is to be butch :) for @unicyclehippo , also on ao3]

//

giving your body to ava is easy; giving your body to yourself is the hard part.

you’re supposed to protect her, you’re told: keeping her safe is the only thing that matters. you understand, as you tug a scratchy blanket up over her shoulders on a train to a little town nestled in the alps, that you are in charge of keeping ava safe because she’s the halo-bearer, because she’s the key to slaying demons and defeating adriel and heaven and hell and the earth between. you’re not supposed to keep her safe because she’s ava, but her breaths are warm against your neck, tucked in safely, her chin on your shoulder — you will keep her safe. it’s a vow you take with the gravitas you have your others, perhaps even more certain, sure, clear: you will keep ava safe.

you’ve felt the same impulse — not as strong, and not as sharp, but the same — toward a few people you’ve known. mackenzie, in third grade, after keith, a fourth grader, called her a bitch at recess, and it was easy, so easy, to let the anger well up in you and to, just like you’d been trained in aikido since you were five, punch him in the throat. you’d had to go to the principal’s office after a small riot had erupted, and you’d sat, sullen, while your principal told your mother and father what had happened. they asked you to apologize, and the words — rotten and wrong — got stuck in your throat. you were suspended for a week and your parents made you go to bed without dinner the entire time; your stomach ached to the point of physical pain and it was hard to think, but when you went back to school, mackenzie had smiled big and bright and had kissed your cheek and brought extra cookies to share at lunch, and it was so worth it.

you’d felt the same impulse in eighth grade, with marin, your best friend. she would come over after archery, and she said she didn’t mind that you were sweaty, even though you knew, objectively, it was gross. marin was always wearing a ripped denim jacket you were, silently, in love with, and her parents let her put purple streaks in her dark hair, and you couldn’t stop thinking about her mouth, even during algebra II, your favorite class. you learned to walk, on impulse, between her and the road whenever you were on the sidewalk; you held hands and felt proud: you were, in ways you had no idea how to name, hers. she pressed you up against the packages of mein and liangpi and cans of kidney beans in your pantry and kissed you, quietly and softly, one day. your first kiss, in the dark in the closet, and you had frozen stock still because — homosexuals are going to hell; that’s not love, that’s a sin, every sunday, and wednesdays during lent and vespers too, all the rosaries in the world won’t take away the way marin sighing into your mouth feels so perfect you want to die in it — it’s in your core, this want. so, of course, you kiss her back. you don’t know what you’re doing, have only watched movies where boys kiss girls or maybe you’d mostly skipped those parts; maybe in bend it like beckham you had paid attention to keira knightly’s short hair and her stomach and jesminder’s smile and the curve of her nose and found it more compelling than the men’s matches your dad takes you and your brother to see. your hands are shaking but you fist them in marin’s hair, coarse and curly and perfect, and you think you might explode when she rests her palm on your hip. it feels a little like jumping off a cliff.

and even your father walking in on you hadn’t stopped you from the want; your mother’s you’re disgusting; i’d rather you take your own life than be gay and the priest at their church telling you, quite clearly, that being a lesbian would result in eternal damnation. even that hadn’t been enough to stop the awful and bright desire to help krishna fix her shelf in her dorm in switzerland when you were sixteen, to accept her thanks in the form of laughter and sweet halwa. you are wrong, you know so, because your parents had seen you kissing a girl and you hadn’t wanted to repent; you had wanted to protect marin from speeding cars and hold her hand in the rain and fall asleep curled up next to her with a movie playing in the background, one where girls kiss and they don’t die afterward. it’s a suicide mission, maybe, the way krishna’s skirt rides up to her underwear while she sits on her bed and watches you level the shelf, her brown skin and the stretch marks you think are beautiful, that you think about kissing, all the time. you learn fencing and archery and you get multiple blackbelts in kendo; one of your sensei has a bright smile and short hair and the most precise hands. she’s beautiful in a way you don’t understand, not really, not yet: her hair is cropped short, and her jaw is square and compelling, and she speaks softly and kindly. when she corrects one of your stances you feel a race of electricity down your spine, the opposite of the stress you feel as your hips get bigger, as you go through the embarrassing ordeal of learning how to put a tampon in, as you have to go up a size with your sports bra. she teaches you to use a bo, and there are many things you can’t name: the power; the ache — you see a reflection that feels so much like a home to you that you are not supposed to want that you don’t know how to face it.

most of the girls in your school had gone to university; you had opened your letters from oxford; from tsinghua; from harvard; from the eth, with steady, sure hands, reading the acceptances calmly. it wasn’t hard, not this part: you braid your hair carefully each day and feel a little like throwing up every time you had to put your skirt on, the weekends and your aikido and judo classes and the standard, starchy, thick gi the most profound reprieve — you studied and you took your exams and it was easy, to become an asset, to become a weapon. you’re brilliant, all of the adults in your life tell you so. you stare at your ceiling and on the bad nights you can’t feel your hands. on the bad nights you want to touch yourself so badly you could scream, and you let your fingers wander down your stomach into the curls that have grown dark between your legs, and you think of stupid keira knightly’s hipbones and you feel the wetness there before you pull your hand away, every time. it’s wrong, to want like you do: to think of what a tweed jacket like your professors wear would look like, how your shoulders would be square and strong; every now and then, you stare at the scissors in your bathroom, for trims in the months between semester breaks when you can leave the grounds, and wonder what it would be like to just cut your hair short, how you might get in trouble but it also might be a relief. there is so much grace you can’t give to yourself yet.

of course, you’re not brave enough for any of it. you are brave, enough, however, to want to die: the ocs is bloody and brutal and a home unlike one you’ve ever known. it’s easier to push all of the sin down and fashion yourself useful, so useful if anyone, anyone at all, ever found out what you think about in the middle of the night, they would still have to value you: you have your arrows and your knives and your sisters and the most beautiful bo you had ever seen. you have your habit and your combat boots; you eat three exacting meals a day and you want and you want and you fucking want — but you tell ava about it, as clearly as you can, and she just loves you. you’re rude, for a second, but she sits patiently and doesn’t judge you for your tears or the curling desire in your chest, and then, what feels like a literal miracle, she tells you that you’re beautiful and you want to be called that, you want to be called handsome, you want her to laugh at your jokes and stare too long at your freckles. you want to love her, and you do: you want ava, who is so pretty and kind, despite it all, to know, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that you will be there for her. so you bandage the cut along your cheekbone in the train car and don’t think of the acceptance letters you had calmly thrown in your trashcan, or the thick watch the woman in front of you was wearing, her sleeves rolled up her forearms, or the way ava is warm and soft and you will gone on as many suicide missions as it took to protect her. to protect her, not the halo, not the church: ava.

she stirs eventually and smiles up at you, groggy and grateful and trusting, like she knows you won’t let anything bad happen to her; it’s easy to let her touch you, to let her lean on you, to let her use you for anything she needs. your heart swells as she burrows deeper into your side.

/

the first time you really allow yourself to think of it, this monstrous, lovely ache inside of you, is when lena, a shopkeeper in switzerland with a neat fade, a perfect quiff combed neatly on top, streaked with grey, and an impeccable linen suit, hands you a pair of pants. ava is in the dressing room trying on a pile of tiny clothes — which you do your absolute best not to think about — and the soft material and exact stitching: neat pleats that will accommodate the small flare of your hips; a straight leg that will sit at your ankle. lena smiles and offers you a few button downs, oversized and collarless, tailored perfectly, and she doesn’t know you’re a nun but you take them all and tell yourself that they’re suitable for you because they’re modest, because they won’t draw attention — not the way ava’s brightly patterned button down she ties into a crop top will, not the way ava will, just inherently, with her perfect smile and elegant brow. you’re drawn to earth tones, to subtle patterns, to thick cotton that drapes without sitting against your chest too snugly. ava loves your clothes, apparently, which is mostly expected because ava loves everything and, you’re certain of it, ava loves you. not as a sister warrior, not as a nun, but as beatrice, which is perhaps the scariest thing of them all.

/

one day, while ava is working and you have unadulterated and unmonitored time to yourself, you let your feet carry you to lena’s shop. ava has been reading you poems at night, and she’s been steadily collecting a few vinyl to play on the phonograph, even though it’s prone to skipping. it’s a life, gentle and slow, even with your training and the looming threat of an apocalypse of literally biblical proportions, and you have no idea how to reconcile who you have always tried to be with who you are, and what you want.

the first night you had been in switzerland, in your tiny apartment with dust and lumpy furniture and ava’s desperately excited energy, you had sat on the couch quietly as she puttered around and then finally settled in bed. you had lied back on the couch, and she had huffed and then sat up: ‘bea, what are you doing?’ she had asked.

you hadn’t been able to find the words that you really meant so instead you’d told her, ‘i’m keeping watch,’ and you hadn’t had to look away from the water stain on the ceiling to know she was rolling her eyes. you had argued, a little, but the couch was genuinely so uncomfortable and you hadn’t slept in so long, you’d gotten up and shuffled to the unoccupied side of the bed. ‘are you sure this is okay?’ you’d asked, and she’d squinted.

‘why wouldn’t it be?’

you had frowned and bitten your bottom lip and stumbled through, ‘because i — i’ve told you, i —‘

ava had rolled her eyes. ‘i don’t care what your sexuality is, beatrice. what i do care about is you sleeping; you’re dead on your feet.’ she had paused and waited for you to situate yourself under the covers, stiffly on your back, and she had huffed a breath and then — slowly, and you were not the only one who understood the overstep of nonconsensual touch, the pain and fury — settled her head just under your chin, resting on your chest. ‘i trust you to keep me safe.’

looking back, maybe that was it, maybe that was the moment you understood: one day, you want to wear a suit to a nice dinner; you want loose, perfectly tailored pants and expensive, thick cotton and for women and femme people — someone like ava; ava herself, you allow yourself — to think that you are attractive, that you’re sexy, that you would do anything to make sure they’re cared for. that you delight in it.

lena is a miracle herself, you think: she understands who you are, or, at least, who you want to be, buried underneath the rubble of a thousand explosions you’d set off along your spine and within your ribcage. she hands you a beautiful suit, and she lets you try it on; some days, you have tea with her wife and practice your arabic and you blush at aleyna’s gravely voice and the way she talks about her favorite art. you are overcome, when you see yourself in the mirror; your soul, eternal longevity be damned, leaps: there you are. you do up an elegant pair of cufflinks and look at a reflection you have always wanted to know.

there you are.

/

ava’s freedom is enviable: she wears clothes she loves and excitedly lets you cut her hair to her chin, because she wants to and because she thinks it’s fun and it’ll look so cute, bea, and she smiles afterward, laughs at herself, delighted, in the mirror. you let her think she’s convinced you of something really exciting and serious when you agree to get highlights; mostly, it makes her happy, and it’s not exactly what you want, but it’s something. ava flirts with boys, and ava flirts with girls, and she leans forward against the bar and winks at you when you drag your eyes away from her chest. some days, you think you might strike up the nerve to ask her, late at night, after you’d heard her touching herself in the shower, stifling little moans: what does it feel like to want with abandon? what is it like?

but you don’t: you dance with her, your head hazy, and you leave a letter — too sentimental, too telling, but a breath — for lena and her wife before you flee. you fight your way through all of madrid and an awful, nightmare of a vision of her with the fog, and then you hold her in your arms, once, after she dies again, after she falls and her body explodes inside its skin — literally. you pray and pray and pray — to her, not a single thought spared for god, and you would give up everything in your life: your vows, your worth, everything, for her to be alive. and she is, eventually, and you help her out of your clothes and it’s a kind of honor in this too: she trusts you not to hurt her, never to hurt her. she trusts you, in the shower, while you’re in an undershirt and boxers and you clean the blood from her ears, to be gentle to her, and to keep her safe.

you have your habit and your robes and your weapons; with each passing day, you become more and more terrified that ava is going to die. you love her; you want, in some way, to spend your life with her, whatever that might mean. but where does it all lead for you if she does die? you clutch your rosary in your hand and feel a very particular horror: who are you, if not for ava’s love? where, now, would all that want go?

/

ava kisses you. it’s your second kiss; you’re the second person she’s kissed, you know as much, but it doesn’t matter: you’ve held her before. you know this, as surely as you know anything. she has been many people, in some way or another, and maybe you have to. there’s so much of your life that has never been yours but the decision to follow her lips as she draws back and bring your hand to her jaw rests in your hands, as steady as they are when you have your bo, and far gentler.

ava kisses you, as she decides to die. you hold her as her body — this beautiful, small, miracle of a body that you love, that you love — fails her, with a particular finality as it glows blue and crumples. you know, when you send her through the portal, that you are going to have to leave this life you have forced down your throat and driven into the marrow of your bones like rods in the center. i love you, you tell her. you hope she knows.

/

no one cares, you realize, if you try on a pair of men’s jeans at a thrift store in berlin. in fact, robbie compliments them casually; you’re not sure if they know how much it means, but they have a lump of skirts in their arms and a neatly trimmed beard and glamorous blue eyeliner today, so you think they probably do. you pull the pants on in the dressing room: they’re light washed, and loose; they fall just at the bottom of your ankles, and you cuff them twice and pull on the sturdy blundstones you’ve worn all over the world at this point. you can see yourself in them in the winter, a big, elegant peacoat and a scarf pulled around your neck, and soft and warm; you can see yourself in them in the summer, rolled up with sandals and an oversized t-shirt. it’s different, than the time you’d tried on a suit — more casual, more variable — but the recognition is there all the same.

‘did you like them?’ robbie asks, meeting you at the front with a few skirts and a crop top that pangs in your chest because robbie will look great in it; because ava would love it.

‘i loved them,’ you say, and a knot releases somewhere in your chest.

/

you end up in los angeles — one tattoo on the top of your wrist and a surfing lesson booked — mostly because it’s the city of angels, which feels a little inevitable, and also mostly because it’s so far from anything you’ve ever known. you keep to yourself at first, mostly, but then you make casual conversation with a few of the surfers out near your airbnb every morning, and they love your accent and give you pointers on how to pop up on your increasingly smaller board and invite you to an arooj aftab show at the broad. it aches, to live this life without ava, even though it’s what she wanted for you, what she asked of you.

you drive along the hellish freeway to make it on time, and you let your friends buy you a drink at the outdoor bar, a little paper wristband signaling you’re over 21 after you’d shown your ID at the entrance; you had agonized over what to wear and settled on your favorite pair of pants, one that you’ve had since switzerland, a wide-legged pair in a deep navy that lena had tailored to fit your waist properly, and a linen collarless button down in a seafoam so pale it’s almost white, the sleeves cuffed up to your elbows, a pair of airforce 1s which your friend had promised you are, without fail, cool. you feel nervous but then your friends seriously look through some art pieces in the museum before the show, and one of them has on a pair of leather chaps, and no one cares at all. you’ve pulled your hair up into a careful, smooth bun for as long as you can remember, and at the show you close your eyes and let your heart hurt: you miss ava. you miss the love of your life, and you miss your faith, and you miss something you’ve wanted your entire life: to be seen as who you are. to be brave enough.

there’s lilting smoke and bright lights diluted by it, everything striking in urdu; you can’t translate each word, of course not, but you do understand: there are so many ways to pray. there are so many gods to pray to.

your friend drops you off at your apartment later that night; you stand in the kitchen in your black sports bra and the simplest pair of black cotton underwear you could find, and let your hair out of its bun. your skin is clean and clear and you have more freckles now than you have your entire life. your hair has gotten long, and every few days someone decides to tell you it’s beautiful. it is, you guess, even though, sometimes, it doesn’t feel like yours. you’d watched paris is burning a few weeks ago, alone at night when it was dark and the only noise you could hear was the gentle brush of the waves outside, after you’d poured yourself one of your favorite ipas and made popcorn, after you’d liet yourself eat a piece of pizza even though you hadn’t gone on a run earlier. you don’t feel like yourself, not all the way: you don’t always want to look at your hips and your chest and when your hair tickles along the middle of your back you have to close your eyes and breathe through it; you love the muscles that have grown sharper and bigger along your arms and the ink in your skin and the way your thighs cut strong and taper down to your knees, the color of your eyes at sunset. you are becoming; it hurts.

you watch the holiness in the ballrooms and you know: people have been far, far braver than you. loving ava — loving yourself — is not a kind of death sentence; it’s a kind of life.

/

camila facetimes you in the mid-morning, after you’ve just finished sparring. you’re in a sports bra, the weather too hazy and hot to wear your entire gi on the full walk home. camila grins when she sees your bare shoulders.

‘picking up the ladies, bea?’

you’ve never definitively said anything, but you kissed ava and then renounced your vows and, honestly, you think everyone probably knew the entire time anyway — it’s not as scary as you thought it would be: camila’s eyes are bright and clear and she’s just calling to say hi. there’s no condemnation; there’s no judgement, only your friend, your sister.

‘no, no,’ you say, and camila pouts, which makes you laugh. ‘it’s just hot.’

‘probably because you’re shirtless on the streets of los angeles.’

‘it’s a two block walk home from my dojo, camila.’

‘you’re not a nun anymore,’ she says. ‘let me have a little fun with it, at least.’

you’re quiet, just a beat too long.

‘how are you doing?’ she asks, resolute and gentle like always.

it goes without saying: you miss ava so much it feels like you’ve broken your wrists; you are in love with the world. ‘i’m — i’m figuring it out.’

it’s a more hopeful answer than camila was expecting, clearly, because she perks up and smiles.

‘well,’ she says, ‘it looks good on you.’

/

one night you think of the curve of ava’s rib. the twelfth, exactly, the way it wrapped slightly in her back, near her spine, a flutter away. you think of the way her shirt rode up in the middle of the night, how she rolled over onto her stomach and you saw the dimples above the waistband of her shorts, the curve of her ass, the nape of her neck, the delicate press of her wrists. it felt wrong, to look like that, your eyes red with sleep — but she was there, and she was so, so beautiful.

one night you can’t sleep and you close your eyes and think about the way ava’s lips had felt against yours. you try not to concentrate on any of the bad, just for now, just for a breath, just for this sliver of moonlight and the quiet seep of your desire onto your fingers when you press between your legs.

you wonder, absently, if hell will open up and swallow you whole. you rub circles around your clit and try, so hard, to listen to your body, to trust it like you had only learned how to do in a fight, like you had only allowed yourself in moments of pain and danger. but you’re safe, in this big bed by the ocean, and you think of ava’s twelfth rib and heaven and you come silently, pleasure drenching down your spine as you allow it to curve into the light.

you give your body to yourself, just for a few minutes, and it feels like heaven. you lie back against your pillow and blink open your eyes and laugh.

/

ava has been back for less than twelve hours before she flits through your closet. you’ve picked up pieces here and there, mostly earth tones, mostly loose and comfortable fabrics; you have a few hoodies, which seem to really delight her, and a tweed jacket you haven’t fully worked up the courage to wear with some slacks yet, although they’re both there, and ready, and available.

‘this is so gay,’ she says fondly, meaning, you presume, your entire wardrobe, and it’s so, so stupid for you to feel panicked, because you are gay and you want, so badly, to love being gay, because you love ava, more than heaven and earth, and she came back for you. but still, you can’t erase so many years of hating a fundamental part of who you are; ava frowns and walks up to you slowly. ’bea.’

‘it’s fine.’

‘i’m sorry.’ she takes both of your hands in hers and runs her thumb along the back gently. ‘i don’t — this is all still kind of new to you, i guess.’

it’s gentle, and forgiving, and opens up so much space for you. you had wanted, so, so many times, to change into who you are, brimming under the surface, and you’d only started to feel brave enough when you’d seen her genuine smile at your new slacks in switzerland. you suppose, really, it’s not that much different now. ‘i, uh, i see a therapist.’

‘oh?’ she doesn’t back away, only squeezes your hands. ‘that’s awesome. do you like them?’

‘i do.’

she just stands and waits and you are thankful for her, again and again; you have missed her so, so much.

‘i started — because i was grieving,’ you say, quietly and in the direction of a row of sneakers on the floor. ‘i went because i was hurting, and i didn’t know what to do with it.’ you had started going because, one night, you had gotten roaringly drunk at a little bar in echo park and felt like you wanted to walk into fucking traffic on the 405 when a girl with ava’s lotion passed by you, but that’s a detail you can mention another time, or never.

‘i’m sorry, bea.’

‘no.’ you touch her face gently, rest your hand on her collarbone. ‘not your fault. but what i mean is that — i started going because i missed you, and i didn’t know who i was, really. i left the church, and i fell in love with you, and, like, how do i become who i really am as a lesbian ex-nun whose — uh, person, is, well, missing, for an undetermined amount of time.’

‘therapy does seem like a good start with that,’ she says sagely. ‘also, person?’

‘we hadn’t discussed what we were to each other, before the portal, so.’ you shrug. ‘i know you’re my partner. but you are also my person.’

‘love that,’ she says, and smiles, ‘and love you. and other than how incredible i am, what have you learned about yourself?’

you lead her to a drawer in your closet, and you open it and take out a chest binder, black and unassuming, one you haven’t worn yet but had bought one morning online, after you’d had a wonderful surf session and you had wondered, just enough, how it might feel. ‘i don’t know,’ you say. ‘i don’t — i’m figuring it out.’ ava is still and patient beside you; you have a holy war coming, one neither of you is sure to survive, and it all seems to matter a little less in the face of it. or, maybe, it matters more. ‘is that okay?’

‘fuck yeah,’ ava says. ‘you’re so hot, like, god, even hotter than i remember? what a fucking gift! and, yeah, i mean, you’re however you feel, regardless of me. i know i’m like really awesome, but i’m just a person. kind of. for these purposes, i’m just a girl. mostly.’ she laughs at herself. ‘anyway, try it on! if you want. i love you, and i want to see.’

for your entire life you’ll hold it in your heartspace: i love you, and i want to see. just like that, just like a commandment — true, noble, right, pure, lovely, admirable, excellent, praiseworthy. ‘okay.’

‘sweet,’ ava says, ‘i’ll be waiting out here, whenever you’re ready.’

you step into the binder and pull it on like you’d watched a few tutorials of, and you don’t think it’s something you want all of the time, but your heart pounds and your palms sweat and then your entire body settles when you situate the straps on your shoulders and turn in the mirror, see your chest mostly flat. again, it’s like seeing yourself for the very first time: there you are.

you wipe a few tears from your cheeks and let out a big breath and then slip a t-shirt over your head, pad out to where ava is very obviously vibrating with excitement and not at all reading the book on her lap, opened to a random page.

she groans and leans back dramatically. ‘even hotter, wow.’

���yeah?’

‘yes!’ she narrows her eyes. ‘but, from what i think your therapist is getting at: how does it make you feel? even if i wasn’t here to tell you how hot you are, which i always will be now, obviously. but even if i wasn’t, what are you feeling?’

unbound, you remember, unburdened. ‘happy,’ you say, and she stands and runs her hands up and down your sides, over your flat chest, and kisses you. ‘i feel so happy.’

/

ava is overjoyed when one of your friends in madrid invites you to a drag show. technically, you’re both supposed to be Very Seriously Working, because there really is an imminent number of battles looming over the horizon, but you rent a little flat a few blocks from headquarters and sometimes try your best to take ava on dates. obviously, she enjoys doing everything in her power to loudly woo you: she buys flowers from a vendor on the corner and dramatically gives them to you; she brings home books you might like, in all kinds of languages; she tells everyone at the ocs how your lesbian love was what was strong enough to bring her back from the other realm. it’s all a little ridiculous, but she always has been, and it’s intoxicating to be the sole focus of her joy sometimes.

ava whistles and you roll your eyes when you slip a warm oversized cream color wool sweater over your binder, careful not to mess up your meticulous bun, and let it sit loose and elegant over a pair of navy slacks and slip on a pair of brown loafers. ava is in a dress and a blazer and she’s done eyeliner and lipstick and she’s so, so fucking beautiful. you’d put a little mascara and chapstick on and a little thrill goes through you: ava wants to be on your arm tonight; she wants to sit next to you and whisper joyously in your ear and kiss you and come home with you — ava looks like that and ava is yours.

there are three queens performing that night, two songs each, ava informs you, when you meet up with your friends. it’s loud and bright and one of the queens — ava’s favorite, if her screaming next to you has any indication — does ‘pure/honey’ from renaissance, which, in ava’s words, brings the house down.

‘gender fuckery is heaven, baby,’ the queen says after, to absolutely raucous cheers from the crowd. ava looks at you with a raised brow but her grin is so big you can’t do anything but kiss her: the swell in your chest is good, you decide, like a perfect set by the pier just after sunrise, wave after wave breaking in a way your body knows exactly what to do with, exactly how to ride safely into shore. you wipe a few tears but you let ava drag you to your feet and you sing along, on your own accord, when they play whitney houston.

/

‘what’s one thing — especially something that you’ve maybe felt scared of, or that you’re not sure you’ll like — that you associate with queerness that you’ve always wanted to try?’

and, like, therapy is hard, okay? it’s hard when ava is so overjoyed and so fearless about her own sexuality, and about loving you without any hesitation; of course, you both have trauma, but ava has never, in her entire life, tried to deny herself want or pleasure or expression.

and it’s hard because, god, there are so many things on that list. some of them you’ve done: buying men’s pants (that fit you like a dream, thank you very much); dancing with ava and finally kissing her after a few shots; going to a lesbian bar; going to a drag show. you want to get more tattoos — some that mean important things, and maybe some that don’t, that you just like — and you want to smoke weed the way ava does with your friends sometimes, laughing slow and soft and curling up in your lap. you want to kiss ava in front of a van gogh without checking around you first; you want to pull her chair out at dinner; you want to laugh when your friends say that’s gay — with lots of love — after one of them says something sweet about their partner. you want ava to steal your clothes. you want to go to pride. you want, very badly, to find a church that doesn’t make you feel like dying.

‘it doesn’t have to be serious,’ your therapist says, coaxing you along just a little. ‘it doesn’t have to be huge or life-changing. just something you might try, whatever comes to mind.’

‘a haircut.’ it sort of comes out of your mouth without permission, but maybe that was the point; you’re still figuring out want and desire and giving in to them without anxiety.

your therapist smiles, and it feels good, warm, to know that you’ve told the truth, that she seems to understand. ‘why does that scare you?’

you look down at your hands and will yourself not to fidget; your therapist notices and hands you a stim toy, admittedly your favorite one.

‘well, first, what if i hate it?’

‘haircuts are, fortunately, relatively temporary. what would you do if you did hate it?’

‘grow it out again, i guess.’ you think of ava’s collection of hats and beanies. ‘a cap, maybe?’

‘logical. what else scares you?’

‘what if ava hates it?’

‘well, from everything i know of ava, i doubt she would hate anything you decide could bring you joy. and she seems very into you.’

it gets you to smile: ava makes that known often, and to everyone she wants, it’s true.

‘when ava tries something, like a haircut or color, or a more masculine or feminine outfit, how do you feel?’

‘i love her, obviously. in any form; she’s beautiful and she’s my partner.’

your therapist smiles. ‘exactly. and, beyond that, i know we’ve been talking about this, but your sexuality and your relationship to it, and your joy in it, lies far outside of your partner. you were a lesbian before you met ava, and you will be, no matter what your relationship with her is, unless you decide you feel something different. your queerness and place in it isn’t just about sex, or your partner. it’s about who you are, fundamentally, and how you want to be seen for it.’

you nod, take a deep breath. ‘yes. i guess, well, when i was younger, 12 or 13, maybe, i wanted to cut my hair short. i was in so many martial arts and archery classes; i ran and swam all the time, so it seemed easier. it also seemed … cool? like, i thought it might feel… that it might feel good, or right. i didn’t know why.’

‘why didn’t you cut your hair then?’

‘my mother, when i asked, she said that it would make people think i’m … that i’m a dyke.’ you pause, let the hurt well up in you and breathe it out. ‘she used that word, and it scared me.’

‘what does that word make you feel now?’

‘i… i love it? it still feels a little scary, maybe, but — i already know people look at me and don’t think i’m straight, even when i’m not with ava. that used to be terrifying, because what if someone was unkind or even dangerous? but that … it hasn’t happened, and, if it did, i could handle it. i know i could.’

‘so what would a haircut change, then?’

‘if i — ‘ you imagine it, then, you let yourself: how the collar of your favorite turtleneck sweater might look, how easy it would be to take care of after surfing, how you could put on mascara and linen and your favorite sunglasses and hold ava’s hand, just like always. ‘people would see me and know i’m a lesbian, i think. it’s… a choice, for me at least, to look queer. and a haircut is one i can’t immediately change, like clothes. and we’re going to see my old friends soon, and i don’t know what they’d think, and — ‘

‘your friends have been accepting of you, and of ava, and of you and ava together, right?’

‘yes, of course. but it would just be — i couldn’t hide. everyone would know; everyone would be able to see, all the time. ava isn’t read as queer all the time; i can pass as straight. but if i couldn’t — ‘

when you don’t continue, your therapist gently says, ‘you would be seen. which is scary, and i hear what you’re saying, absolutely. but, beatrice, you would be seen for who you are, without apology.’

‘that’s true.’

‘i have one more question.’

‘okay.’

‘what would happen if you loved it?’

/

‘how are you doing?’ your stylist, xavi — one of your favorite people on the planet, one of your best friends who has been offering to give you a haircut you actually want for two years now — calmly combs out your long hair after she’d washed it.

‘i think i might throw up.’

it makes her laugh, which is maybe a little mean but also why you’re so fond of her; she had been one of the students in your adult beginners aikido class and, while she hadn’t shown any talent or much interest, she had made you smile all the time and invited you and ava to dinner with her and her wife as soon as she found out you mentioned ava, and you had been friends ever since. most days, you just put your hair into a neat bun. ava likes to play with it down, especially when you’re sleeping in, but when you told her you wanted to cut it she had kissed you square on the mouth. ‘i love you, and i want to see,’ she’d told you again, and played with the engagement ring around your finger. ’even if it looks terrible — which isn’t possible, because it’s you — there’s no way i’m ever asking you to take this off. ever, ever, ever, bea. okay?’

xavi pats your shoulder; she had excitedly fit you in this morning after you’d texted her after therapy yesterday with pictures of a short, neat mid-fade to the skin, sitting in your car before you even drove home, afraid you’d lose your nerve if you didn’t. ‘we can just do a trim, or start with a little off, and you can decide how you’re feeling from there.’

it’s so patient and so kind. ‘no, no. i — i’m sure. i’m just scared.’ it’s ridiculous, really, you think: you’ve been shot and stabbed and blown up multiple times; you have killed more people than you can count; you have almost died, so, so many times. but this, this is living, true to who you are. ‘i — this is what i want. i know this is what i want.’

‘okay then,’ xavi says, and collects your hair, smooth and long, into a ponytail at the base of your skull. ‘ready?’

‘as i’ll ever be.’

it’s fast and unceremonious, just a few sips as you close your eyes, but then you feel hair tickle your cheeks and you open your eyes and xavi hands you your long ponytail with a grin.

‘oh my god.’

‘okay,’ she says, ‘we can stop here? i can definitely make this work.’

‘no, no,’ you say, ‘it’s good.’ you laugh. ‘i feel good.’

‘you want to keep going?’

‘yeah,’ you say, let out a breath you didn’t even know you were holding, settled in a way, already, that you never have been before in your entire life. ‘let’s do it.’

‘amazing,’ xavi says. ‘this is going to look so good.’

and, really, it does: xavi turns the clippers on and you let go of the swoop in your stomach, your clammy palms, the too-fast thud of your heart, and just let yourself become. xavi explains what she’s doing each step, and she talks about the kittens she’s fostering, and asks you about your new aikido class, and it’s easy.

she finishes; she places a hot towel on your neck and makes sure your hairline is clean in the back and then shows you how to put a little pomade in the top, an inch and a half long, textured and dark. she takes the cape off and you stand, look at yourself in the mirror: your favorite crewneck, and a pair of pants ava had surprised you with from artists and fleas, the thin chain with a tiny cross you don’t take off sitting just below your collarbone. ‘i love it, xavi,’ you say, your hands are shaking but when you bring them up to your hair there’s a clarity in your chest that’s never been there before: unbound, unburdened, you remember, and also: i felt finally myself.

/

you’re in and out of it after surgery; you know your injuries as ava told you and then the surgeon explained more completely. mostly, you’re just relieved you’re alive, because the moment before you hit the wall you were sure you weren’t going to be. you’d asked mary a few hours ago, while ava was in the bathroom, to convince ava to take a walk and then eat an actual meal, not just pick at food while she sits by your bedside. it works: mary bullies ava into it, but sometimes, even now, that’s just what you have to do.

you fall asleep again; you’ve been walking more the past day, up and around with a walker a few times a day. between that and the pain medicine you’re still on, and the residuals from anesthesia, it’s impossible to not nap fairly often. when you wake up, lilith is kicked back in the chair by one side of your bed, her feet, boots still on, resting by your side on the blanket. mother superion sits next to her, doing a crossword in the daily paper. the sight makes you laugh a little, and you’re pleased that you’re a little less sore.

they both notice you’re awake; mother superion puts down her crossword but lilith doesn’t move an inch. you’re thankful your surgeon had let you sit on the shower seat and let ava wash your hair earlier this morning, careful to not press hard against the bruise on the back of your skull or get any water on your incisions — you feel slightly less gross and definitely more awake than you had before.

she looks at you and you feel anxious, all of a sudden: lilith appraises you, and then slouches even further into your seat. ‘gay,’ she decides on, and then, ‘aerodynamic.’

you look to mother superion for a moment, whose mouth twitches in a smile. ‘we didn’t have much chance to talk before the battle,’ she says, ‘but what lilith means is that your hair suits you.’

your brain is still sluggish, but — ’because i’m… gay and aerodynamic?’

lilith, miraculously, laughs. ‘well, sure, but it looks good.’ she shrugs. ‘you look like yourself.’

mother superion nods. ‘it’s good to see you becoming who you are.’

you’re definitely still loopy, overly emotional, but you might tear up from that even if you weren’t. still, lilith rolls her eyes. ‘oh, come on, beatrice.’

‘sorry,’ you sniffle, then rub your eyes.

you hear ava’s, ‘you made her cry? i was only gone for like, half an hour? what the fuck?’

‘i said something nice,’ lilith defends, getting to her feet.

‘sure you did,’ ava says. ‘i can still take you in a fight. i’ll do it, swear to god.’

‘you definitely cannot take me in a fight, ava.’

ava stands, indignant, although it’s made less effective by the comfortable hoodie a little crooked on her shoulders and mary’s a whole head taller than her. the halo flares a little but quiets when you reach out a hand in her direction.

‘oh, for fuck’s sake,’ lilith says, and then in a flash she’s gone. mother superion squeezes your hand before she heads out with a nod and another soft smile, and mary follows.

ava sits on the side of your bed. ‘was lilith an asshole? i swear if she made you feel bad about anything i will kill her.’

‘she was actually, in her own way, kind. and mother superion was too. i’m just more emotional than usual because of the meds.’

‘you’re sure?’

you tug ava down a little and she messes with your hair with a soft smile, then kisses your forehead. ‘very chivalrous of you, to offer to defend my honor, though.’

she laughs. ‘i don’t want to fight lilith again, ever, in any realm, in any way.’ she presses her mouth to yours. ‘but, for you, bea, i would do anything.’

/

‘you look — ‘ you let your brother fumble over his words for a moment and then laugh, spare him any more worry.

‘hot is fine.’

he rolls his eyes. ‘you look incredible, bea.’ the suit lena had made you — navy, and light, a slim tuxedo pant, a single button jacket and a perfect, crisp white t-shirt tucked in neatly, sitting beneath — fits exactly how you want it. your hair has grown out, and it parts in the middle now, and flops — as ava loves to say — just above your eyes; the sides and back are still buzzed short, and it makes you smile, even now — your ‘prince charming era’ according to ava. xavi had done your makeup: tinted moisturizer and a little bit of mascara.

‘i do look incredible, huh?’

he smiles. ‘yeah. you really do.’ he lint rolls your shoulders for the final time, more out of nerves than there having ever been lint in the first place. ‘well, let’s do this then. let’s go get you married.’

he walks you down the aisle and then you wait in front of the altar you had made, barefoot on the beach, and when ava rounds the corner and then smiles at you, you know you’ve given her a gift too: i want to see. i love you, and i want to see.

/

‘thank god i married you,’ ava says, tracing a line down your spine and then along the linework tattoo on your ribcage.

‘mmmm,’ you say, ‘i agree. but why, specifically.’

she bends down to laugh into your shoulder before kissing down your spine. ‘it’s fucking insane that you get hotter like, literally every day.’

you laugh too. ‘thank you, my wife.’

she squeezes your hips. ‘wow. my wife.’

you turn over beneath her and pull her down slowly to kiss you. the snow is falling outside but the fireplace at your room in a resort in the alps is beautiful, and everything is warm. you feel the halo hum beneath her hands and it’s easy, it’s so easy, to let ava roll her hips against yours and press you down into the mattress; it’s easy to put on boxers — black calvins, tight against your thighs — after you shower and stand in the mirror. your hands are calm, and it’s so easy, when you really look, to see who you are in your body. to belong only to yourself: there you are.

#wn#warrior nun fic#avatrice#avatrice fic#butch!beatrice#an ode to her bc i love her & i love being butch#if this isn't ur vibe... pls just move along thank u#ava’s favorite way of affirming bea is just being horny. a queen#this entire thing exists bc i had the first line & then lilith saying ‘gay. aerodynamic’ & i had to get from one to the other lmao

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

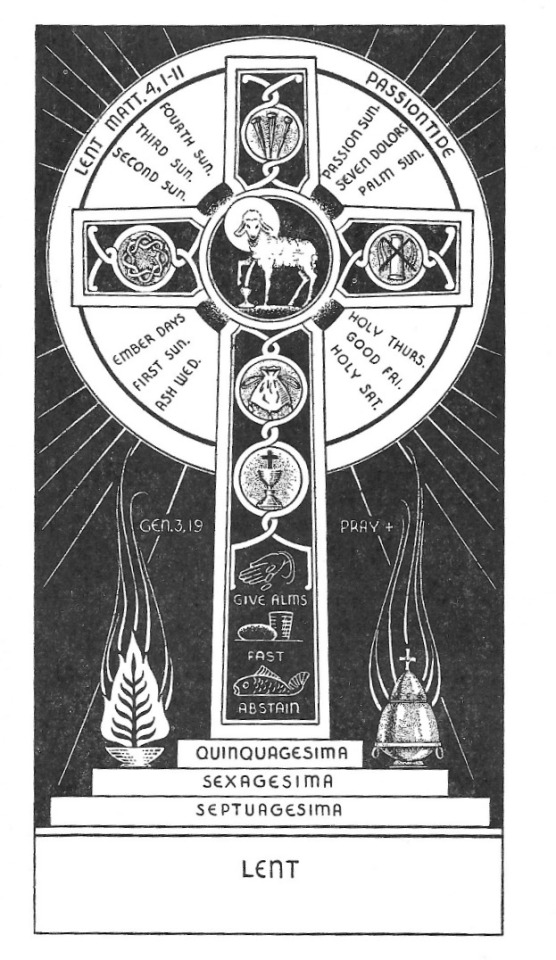

Vestments

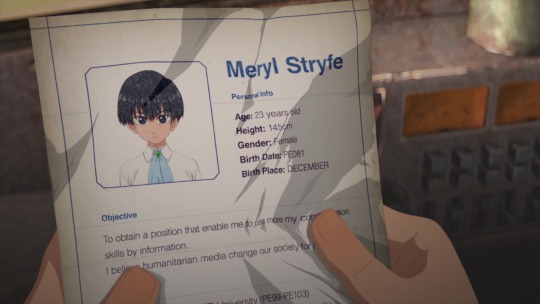

It just occurred to me that probably most other members of the fandom don't have any insight into Catholic liturgical seasons and colours. I used to be an alter server for my parish so a lot of it got sunk into my brain, and I somehow didn't realise it's affecting my reading of Stampede, so...

A Catholic liturgy is an elaborate ritual. Everything about it is layered with significance. It's about representations and stand-ins. And part of that is the clothing!

Vestments. They differ from place to place, depending on what's available, but the calendar and the colours don't change.

Green is for Ordinary Time, between Easter and Christmas or vice versa. It represents hope, growth and life.

White/Gold is purity, joy, light and glory. Angels, saints, feast days relating to Mary, Christmas and Easter.

Red is passion, fire, the blood of martyrs. Good Friday, Palm Sunday, and the Pentecost. A sign that you're willing to die or kill in the name of devotion.

Purple is for Lent or the Advent (before Easter and before Christmas). A mourning colour. Penance, preparation, and sacrifice. A reminder to pray for the absolution of the departed. (Black is also mourning, obviously, but it doesn't get used that much. Wearing black is also a reminder to pray for the departed.)

Rose is very rarely worn - third Sunday of Advent, fourth Sunday of Lent. It represents joy and love, even in times of mourning and penance.

Blue is worn on exactly one day, during the feast of Mary.

#trigun stampede#meta: communion#trigun meta#tw religion#tw catholicism#an excuse to have more pictures of meryl? more likely than you think#say what you want about catholicism but it's an Aesthetic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐜𝐡 𝟏𝟎, 𝟐𝟎𝟐𝟒 𝐆𝐨𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐥

Fourth Sunday of Lent

Jn 9:1, 6-9, 13-17, 34-38

As Jesus passed by he saw a man blind from birth.

He spat on the ground and made clay with the saliva,

and smeared the clay on his eyes,

and said to him,

“Go wash in the Pool of Siloam” — which means Sent —.

So he went and washed, and came back able to see.

His neighbors and those who had seen him earlier as a beggar said,

“Isn’t this the one who used to sit and beg?”

Some said, “It is, “

but others said, “No, he just looks like him.”

He said, “I am.”

They brought the one who was once blind to the Pharisees.

Now Jesus had made clay and opened his eyes on a sabbath.

So then the Pharisees also asked him how he was able to see.

He said to them,

“He put clay on my eyes, and I washed, and now I can see.”

So some of the Pharisees said,

“This man is not from God,

because he does not keep the sabbath.”

But others said,

“How can a sinful man do such signs?”

And there was a division among them.

So they said to the blind man again,

“What do you have to say about him,

since he opened your eyes?”

He said, “He is a prophet.”

They answered and said to him,

“You were born totally in sin,

and are you trying to teach us?”

Then they threw him out.

When Jesus heard that they had thrown him out,

he found him and said, “Do you believe in the Son of Man?”

He answered and said,

“Who is he, sir, that I may believe in him?”

Jesus said to him,

“You have seen him, and

the one speaking with you is he.”

He said,

“I do believe, Lord,” and he worshiped him.

#jesus#catholic#my remnant army#jesus christ#virgin mary#faithoverfear#saints#jesusisgod#endtimes#artwork#Jesus is coming#come holy spirit#Gospel#word of God#Bible#bible verse of the day#bible verse

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Gregorius - Parable of the Prodigal Son -

The Parable of the Prodigal Son (also known as the parable of the Two Brothers, Lost Son, Loving Father, or of the Forgiving Father) is one of the parables of Jesus in the Bible, appearing in Luke 15:11–32. Jesus shares the parable with his disciples, the Pharisees, and others.

In the story, a father has two sons. The younger son asks for his portion of inheritance from his father, who grants his son's request. This son, however, is prodigal (i.e., wasteful and extravagant), thus squandering his fortune and eventually becoming destitute. As consequence, he now must return home empty-handed and intend to beg his father to accept him back as a servant. To the son's surprise, he is not scorned by his father but is welcomed back with celebration and a welcoming party. Envious, the older son refuses to participate in the festivities. The father tells the older son: "you are ever with me, and all that I have is yours, but your younger brother was lost and now he is found."

The Prodigal Son is the third and final parable of a cycle on redemption, following the parable of the Lost Sheep and the parable of the Lost Coin. In Revised Common Lectionary and Roman Rite Catholic Lectionary, this parable is read on the fourth Sunday of Lent (in Year C); in the latter it is also included in the long form of the Gospel on the 24th Sunday of Ordinary Time in Year C, along with the preceding two parables of the cycle. In the Eastern Orthodox Church it is read on the Sunday of the Prodigal Son.

Albert Jacob Frans Gregorius, or Albert Jacques François Grégorius (26 October 1774, Bruges - 25 February 1853, Bruges) was a Flemish-Belgian portrait painter and Director of the art academy in Bruges.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's Mother's Day here in the UK tomorrow.

Per wikipedia: "Mothering Sunday is a day honouring mother churches, the church where one is baptised and becomes "a child of the church", celebrated since the Middle Ages in the United Kingdom, Ireland and some Commonwealth countries on the fourth Sunday in Lent. On Mothering Sunday, Christians have historically visited their mother church—the church in which they received the sacrament of baptism."

In more recent times it has become a more general celebration and appreciation of motherhood, boosting sales of flowers, choclates, sparkling wine and greetings cards....

Genuine appreciation is an option.

(Ian Sanders)

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today, on the fourth Sunday of Lent we celebrate the Venerable John, Abbot of Sinai and author of the Ladder of Divine Ascent (or the Climacus). This indispensable book stands as a witness to the great effort needed for entrance into God’s Kingdom (Mt.10: 12). The spiritual struggle of the Christian life is a real one, “not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers of the present darkness the hosts of wickedness in heavenly places” (Eph 6:12). Saint John encourages the faithful in their efforts for, according to the Lord, only “he who endures to the end will be saved” (Mt.24:13). The troparion of Saint John is chanted by St. Kassiani Antiochian Archdiocese Choir of Australia. May he intercede for us always + #saint #john #ladder #ladderofdivineascent #johnclimacus #climacus #book #lent #greatlent #kingdomofheaven #God #easter #pascha #journeytotheresurrection #resurrection #sinai #abbot #egypt #orthodox (at Sinai, Egypt) https://www.instagram.com/p/CqOiHccjGm9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#saint#john#ladder#ladderofdivineascent#johnclimacus#climacus#book#lent#greatlent#kingdomofheaven#god#easter#pascha#journeytotheresurrection#resurrection#sinai#abbot#egypt#orthodox

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The next Sunday is called "Meat-Fare" because during the week following it a limited fasting -- abstention from meat -- is prescribed by the Church. This prescription is to be understood in the light of what has been said about the meaning of preparation. The church begins now to "adjust" us to the great effort which she will expect from us seven days later. She gradually takes us into that effort -- knowing our frailty, foreseeing our spiritual weakness.

On the eve of that day (Meat-Fare Saturday), the Church invites us to a universal commemoration of all those who have "fallen asleep in the hope of resurrection and life eternal." This is indeed the Church's great day of prayer for her departed members. To understand the meaning of the connection between Lent and the prayer for the dead, one must remember that Christianity is the religion of love. Christ left with his disciples not a doctrine of individual salvation but a new commandment "that they love one another," and He added: "By this shall all know that you are my disciples, if you love one another." Love is thus the foundation, the very life of the Church which is, in the words of Saint Ignatius of Antioch, the "unity of faith and love." Sin is always absence of love, and therefore separation, isolation, war of all against all. The new life given by Christ and conveyed to us by the Church is, first of all, a life of reconciliation, of "gathering into oneness of those who were dispersed," the restoration of love broken by sin. But how can we even begin our return to God and our reconciliation with Him if in ourselves we do not return to the unique new commandment of love? Praying for the dead is an essential expression of the Church as love. We ask God to remember those whom we remember and we remember them because we love them. Praying for them we meet them in Christ who is Love and who, because He is Love, overcomes death which is the ultimate victory of separation and lovelessness. In Christ there is no difference between living and dead because all are alive to Him. He is the life and the Life is the light of man. Loving Christ, we love all those who are in Him; loving those who are in Him, we love Christ: this is the law of the Church and the obvious rationale for her of prayer for the dead. It is truly our love in Christ that keeps them alive because it keeps them "in Christ," and how wrong, how hopelessly wrong, are those Western Christians who either reduce prayer for the dead to a juridical doctrine of "merits" and "compensations" or simply reject it as useless. The great Vigil for the Dead of Meatfare Saturday serves as a pattern for all other commemorations of the departed and it is repeated on the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of Lent.

[Continued under readmore]

It is love again that constitutes the theme of "Meat-Fare Sunday." The Gospel lesson for the day is Christ's parable of the Last Judgement (Matt. 25:31-46). When Christ comes to judge us, what will be the criterion of His judgement? The parable answers: love -- not a mere humanitarian concern for abstract justice and the anonymous "poor," but concrete and personal love for the human person, any human person, that God makes me encounter in my life. This distinction is important because today more and more Christians tend to identify Christian love with political, economic, and social concerns; in other words, they shift from the unique person and its unique personal destiny, to anonymous entities such as "class," "race," etc. Not that these concerns are wrong. It is obvious that in their respective walks of life, in their responsibilities as citizens, professional men, etc., Christians are called to care, to the best of their possibilities and understanding, for a just, equal, and in general more humane society. All this, to be sure, stems from Christianity and may be inspired by Christian love. But Christian love as such is something different, and this difference is to be understood and maintained if the Church is to preserve her unique mission and not become a mere "social agency," which definitely she is not.

Christian love is the "possible impossibility" to see Christ in another man, whoever he is, and whom God, in His eternal and mysterious plan, has decided to introduce into my life, be it only for a few moments, not as an occasion for a "good deed" or an exercise in philanthropy, but as the beginning of an eternal companionship in God Himself. For, indeed, what is love if not that mysterious power which transcends the accidental and the external in the "other" -- his physical appearance, social rank, ethnic origin, intellectual capacity -- and reaches the soul, the unique and uniquely personal "root" of a human being, truly the part of God in him? If God loves every man it is because He alone knows the priceless and absolutely unique treasure, the "soul" or "person" He gave every man. Christian love then is the participation in that divine knowledge and the gift of that divine love. There is no "impersonal" love because love is the wonderful discovery of the "person" in "man," of the personal and unique in the common and general. It is the discovery in each man of that which is "lovable" in him, of that which is from God.

In that respect, Christian love is sometimes the opposite of "social activism" which one so often identifies Christianity today. o a "social activist" the object of love is not "person" but man, an abstract unit of a not less abstract "humanity." But for Christianity, man is "lovable" because he is person. There person is reduced to man; here man is seen only as person. The "social activist" has no interest for the personal, and easily sacrifices it to the "common interest." Christianity may seem to be, and in some ways actually is, rather sceptical about that abstract "humanity," but it commits a mortal sin against itself each time it gives up its concern and love for the person. Social activism is always "futuristic" in its approach; it always acts in the name of justice, order, happiness to come, to be achieved. Christianity cares little about that problematic future but puts the whole emphasis on the now -- the only decisive time for love. The two attitudes are not mutually exclusive, but they must not be confused. Christians, to be sure, have responsibilities towards "this world" and they must fulfil them. This is the area of "social activism" which belongs entirely to "this world." Christian love, however, aims beyond "this world." It is itself a ray, a manifestation of the Kingdom of God; it transcends and overcomes all limitations, all "conditions" of this world because its motivation as well as its goals and consummation is in God. And we know that even in this world, which "lies in evil," the only lasting and transforming victories are those of love. To remind man of this personal love and vocation, to fill the sinful world with this love -- this is the true mission of the Church.

The parable of the Last Judgement is about Christian love. Not all of us are called to work for "humanity," yet each one of us has received the gift and the grace of Christ's love. We know that all men ultimately need this personal love -- the recognition in them of their unique soul in which the beauty of the whole creation is reflected in a unique way. We also know that men are in prison and are sick and thirsty and hungry because that personal love has been denied them. And, finally, we know that however narrow and limited the framework of our personal existence, each one of us has been made responsible for a tiny part of the Kingdom of God, made responsible by that very gift of Christ's love. Thus, on whether or not we have accepted this responsibility, on whether we have loved or refused to love, shall we be judged. For "inasmuch as you have done it unto one of the least of these My brethren, you have done it unto Me. . ."

--Rev Dr. Alexander Schmemann: Great Lent - Journey to Pascha

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

10th March >> Fr. Martin's Homilies / Reflections on Today's Mass Readings (Inc. John 3:14-21) for the Fourth Sunday of Lent, Year B: ‘The light has come into the world’.

Fourth Sunday of Lent, Year B

Gospel (Except USA) John 3:14-21 God sent his Son so that through him the world might be saved.

Jesus said to Nicodemus:

‘The Son of Man must be lifted up as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert, so that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him. Yes, God loved the world so much that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not be lost but may have eternal life. For God sent his Son into the world not to condemn the world, but so that through him the world might be saved. No one who believes in him will be condemned; but whoever refuses to believe is condemned already, because he has refused to believe in the name of God’s only Son. On these grounds is sentence pronounced: that though the light has come into the world men have shown they prefer darkness to the light because their deeds were evil. And indeed, everybody who does wrong hates the light and avoids it, for fear his actions should be exposed; but the man who lives by the truth comes out into the light, so that it may be plainly seen that what he does is done in God.’

Gospel (USA) John 3:14–21 God sent his Son so that the world might be saved through him.

Jesus said to Nicodemus: “Just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life.” For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him might not perish but might have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him. Whoever believes in him will not be condemned, but whoever does not believe has already been condemned, because he has not believed in the name of the only Son of God. And this is the verdict, that the light came into the world, but people preferred darkness to light, because their works were evil. For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come toward the light, so that his works might not be exposed. But whoever lives the truth comes to the light, so that his works may be clearly seen as done in God.

Homilies (6)

(i) Fourth Sunday of Lent

All of the great religions have a symbol that identifies it. The symbol of Judaism is the six pointed Star of David. The symbol of Islam is the crescent moon and star. The symbol of Hinduism is made up of three letters A, U and M. The symbol of Christianity is the cross. The cross speaks of crucifixion, a terrible form of death that the Roman Empire reserved for slaves and those considered a threat to public order. It is how Jesus was put to death.

When we look upon Jesus crucified, we can see what human beings are capable of doing to one another; we confront the sin that put Jesus on the cross. Jesus lifted up on the cross exposes the evil tendencies that resides in all of our hearts. Yet, when we as Christians look upon the cross, we see more than just the darkness of human nature. We also see the brightness of God’s nature. We see the love of God shining through the crucified Jesus. In the gospel reading, Jesus speaks of himself as the Son of Man who must be lifted up. Jesus had to be lifted up on the cross; it was the price he had to pay for remaining faithful to his mission of revealing God’s love for the world. As Jesus says elsewhere in this gospel of John, ‘No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends’. Jesus’ death on the cross revealed his greater love for us, a love that was faithful to us, even when it meant his death. The love that shone through Jesus as he hung from the cross was the love of God. On the cross Jesus was showing the world that God is love. In the words of today’s gospel reading, ‘God loved the world so much that he gave his only Son’. Jesus’ whole life, and especially his death, was a powerful expression of God’s love for the world and for each one of us personally. Saint Paul could say, and we can all say, ‘I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me’. Jesus was God’s greatest gift of love to the world and to each one of us personally.

Today’s gospel reading goes on to say that ‘God sent his Son into the world not to condemn the world’. There was and is much to condemn in the world. The crucifixion of Jesus, the continued slaughter of the innocents, is a witness to the power of sin in the world. Yet, Jesus did not come among us just to condemn what was wrong in us. God sent his Son into the world to reveal a love that was more powerful than sin or evil, so that we could all be raised up by this love. God sent his Son into the world to release a power of love that would enable us to become the people God desires us to be, what the second reading refers to as ‘God’s work of art, created in Christ Jesus to live the good life’. If we allow ourselves to be touched by God’s love given to us in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, we will begin to live fully human lives and we will enter into eternal life.

Saint Paul in the second reading stresses that God’s love present in Jesus is freely given to us. It does not have to be earned; it is not a reward for what we have done. As Paul says, ‘it is by grace that you have been saved, through faith… not by anything you have done’. No matter who we are or what has happened to us in life, God is for us, God’s love is over us to recreate us, to lift us up from our sin, so that we can live loving lives that reflect God’s love for the world. God’s love poured out through his Son is a gift to be received rather than a reward to be earned. Receiving this gift can be a gradual process in our lives. When Jesus went to wash Peter’s feet, Peter said, ‘You shall never wash my feet’. Peter struggled to receive Jesus’ gift of his self-emptying love. There is something of Peter in all of us. Yet, Jesus would not take no for an answer, saying to Peter, ‘Unless I wash you, you have no share with me’. Peter had many flaws; he would soon deny Jesus publicly. Yet, Jesus insisted on washing Peter’s feet.

God’s love for us present in Jesus is unconditional, because God is love. One of the greatest challenges of faith is to allow God to be God, to allow God present in Jesus, our risen Lord, to bring me to experience his love for me in a very personal way. The light of God’s love never ceases to shine, but sometimes, in the words of the gospel reading, we can avoid this light. Our calling is to keep coming into God’s loving light. That will sometimes mean turning from whatever pockets of darkness are to be found in our lives. They need not come between us and the love of God because as Paul says in one of his letters, ‘nothing in all creation will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord’.

And/Or

(ii) Fourth Sunday of Lent