#Escape Room Croydon South

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#escape room#entertainment#activity#amusement park#game#Escape Room Heathmont#Escape Room Ringwood North#Escape Room Mitcham#Escape Room Croydon South#Escape Room Wantirna#Escape Room Vermont#Escape Room Park Orchards#Escape Room Bayswater North#Escape Room Warranwood#Escape Room Nunawading#Escape Room Croydon#Escape Room Donvale#Escape Room Croydon Hills#Escape Room Warrandyte South#Escape Room Doncaster#ringwood escape room#escape room vic#escape room eastland

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Mighty Boosh on the business of being silly

The Times, November 15 2008

What began as a cult cocktail of daft poems, surreal characters and fantastical storylines has turned into the comedy juggernaut that is the Mighty Boosh. Janice Turner hangs out with creators Noel Fielding, Julian Barratt and the extended Boosh family to discuss the serious business of being silly

In the thin drizzle of a Monday night in Sheffield, a crowd of young women are waiting for the Mighty Boosh or, more precisely, one half of it. Big-boned Yorkshire lasses, jacketless and unshivering despite the autumn nip, they look ready to devour the object of their desire, the fey, androgynous Noel Fielding, if he puts a lamé boot outside the stage door. “Ooh, I do love a man in eyeliner,” sighs Natalie from Rotherham. She’ll be throwing sickies at work to see the Boosh show 13 times on their tour, plus attend the Boosh after-show parties and Boosh book signings. “My life is dead dull without them,” she says.

Nearby, mobiles primed, a pair of sixth-formers trade favourite Boosh lines. “What is your name?” asks Jessica. “I go by many names, sir,” Victoria replies portentously. A prison warden called Davena survives long days with high-security villains intoning, “It’s an outrage!” in the gravelly voice of Boosh character Tony Harrison, a being whose head is a testicle.

Apart from Fielding, what they all love most about the Boosh is that half their mates don’t get it. They see a bloke in a gorilla suit, a shaman called Naboo, silly rhymes about soup, stories involving shipwrecked men seducing coconuts “and they’re like, ‘This is bloody rubbish,’” says Jessica. “So you feel special because you do get it. You’re part of a club.”

Except the Mighty Boosh club is now more like a movement. What began as an Edinburgh fringe show starring Fielding and his partner Julian Barratt and later became an obscure BBC3 series has grown into a box-set flogging, mega-merchandising, 80-date touring Boosh inc. There was a Boosh festival last summer, now talk of a Boosh movie and Boosh in America. An impasse seems to have been reached: either the Boosh will expand globally or, like other mass comedy cults before it – Vic and Bob, Newman and Baddiel – slowly begin to deflate.

But for the moment, the fans still wait in the rain for heroes who’ve already left the building. I find the Boosh gang gathered in their hotel bar, high on post-gig adrenalin. Barratt, blokishly handsome with his ring-master moustache, if a tad paunchy these days, blends in with the crew. But Fielding is never truly “off”. All day he has been channelling A Clockwork Orange in thick black eyeliner (now smudged into panda rings) and a bowler hat, which he wears with polka-dot leggings, gold boots and a long, neon-green fur-collared PVC trenchcoat. He has, as those women outside put it, “something about him”: a carefully-wrought rock-god danger mixed with an amiable sweetness. Sexy yet approachable. Which is why, perched on a barstool, is a great slab of security called Danny.

“He stops people getting in our faces,” says Fielding. “He does massive stars like P. Diddy and Madonna and he says that considering how we’re viewed in the media as a cult phenomenon, we get much more attention in the street than, say, Girls Aloud. Danny says we’re on the same level as Russell Brand, who can’t walk from the door to the car without ten people speaking to him.”

This barometer of fame appears to fascinate and thrill Fielding. Although he complains he can’t eat dinner with his girlfriend (Dee Plume from the band Robots in Disguise) unmolested, he parties hard and publicly with paparazzi-magnets like Courtney Love and Amy Winehouse. He claims he’s tried wearing a baseball cap but fans still recognise him. Hearing this, Julian Barratt smiles wryly: “Noel is never going to dress down.”

It is clear on meeting them that their Boosh characters Vince Noir (Fielding), the narcissistic extrovert, and Howard Moon (Barratt), the serious, socially awkward jazz obsessive, are comic exaggerations of their own personalities. At the afternoon photo shoot, Fielding breaks free of the hair and make-up lady, sprays most of a can of Elnett on to his Bolan feather-cut and teases it to his satisfaction. Very Vince. “It is an art-life crossover,” says Barratt.

At 40, five years older than Fielding, Barratt exhibits the profound weariness of a man trying to balance a five-month national tour with new-fatherhood. After every Saturday night show he returns home to his 18-month-old twins, Arthur and Walter, and his partner Julia Davis (the creator-star of Nighty Night) and today he was up at 5am pushing a pram on Hampstead Heath before taking the train north to rejoin the Boosh. “I go back so the boys remember who I am. But it’s harder to leave them every time,” he says. “It is totally schizophrenic, totally opposite mental states: all this self-obsession and then them.”

About two nights a week on tour, Fielding doesn’t go to bed, parties through the night and performs the next evening having not slept at all. Barratt often retreats to his room to plough through box sets of The Wire. “It’s a bit gritty, but that is in itself an escape, because what we do is so fantastical.”

But mostly it is hard to resist the instant party provided by a large cast, crew and band. Indeed, drinking with them, it appears Fielding and Barratt are but the most famous members of a close collective of artists, musicians and old mates. Fielding’s brother Michael, who previously worked in a bowling alley, plays Naboo the shaman. “He is late every single day,” complains Noel. “He’s mad and useless, but I’m quite protective of him, quite parental.” Michael is always arguing with Bollo the gorilla, aka Fielding’s best mate, Dave Brown, a graphic artist relieved to remove his costume – “It’s so hot in there I fear I may never father children” – to design the Boosh book. One of the lighting crew worked as male nanny to Barratt’s twins and was in Michael’s class at school: “The first time I met you,” he says to Noel, “you gave me a dead arm.” “You were 9,” Fielding replies. “And you were messing with my stuff.”

This gang aren’t hangers-on but the wellspring of the Boosh’s originality and its strange, homespun, degree-show aesthetic: a character called Mr Susan is made out of chamois leathers, the Hitcher has a giant Polo Mint for an eye. When they need a tour poster they ignore the promoter’s suggestions and call in their old mate, Nige.

Fielding and Barratt met ten years ago at a comedy night in a North London pub. The former had just left Croydon Art College, the latter had dropped out of an American Studies degree at Reading to try stand-up, although he was so terrified at his first gig that he ran off stage and had to be dragged back by the compere.

While superficially different, their childhoods have a common theme: both had artistic, bohemian parents who exercised benign neglect. Fielding’s folks were only 17 when he was born: “They were just kids really. Hippies. Though more into Black Sabbath and Led Zep. There were lots of parties and crazy times. They loved dressing up. And there was a big gap between me and my brother – about nine years – so I was an only child for a long time, hanging out with them, lots of weird stuff going on.

“The great thing about my mum and dad is they let me do anything I wanted as a kid as long as I wasn’t misbehaving. I could eat and go to bed when I liked. I used to spend a lot of time drawing and painting and reading. In my own world, I guess.”

Growing up in Mitcham, South London, his father was a postmaster, while his mother now works for the Home Office. Work was merely the means to fund a good time. “When your dad is into David Bowie, how do you rebel against that? You can’t really. They come to all the gigs. They’ve been in America for the past three weeks. I’m ringing my mum really excited because we’re hanging out with Jim Sheridan, who directed In the Name of the Father, and the Edge from U2, and she said, ‘We’re hanging with Jack White,’ whom they met through a friend of mine. Trumped again!”

Barratt’s father was a Leeds art teacher, his mother an artist later turned businesswoman. “Dad was a bit more strict and academic. Mum would let me do anything I wanted, didn’t mind whether I went to school.” Through his father he became obsessed with Monty Python, went to jazz and Spike Milligan gigs, learnt about sex from his dad’s leatherbound volumes of Penthouse.

Barratt joined bands and assumed he would become a musician (he does all the Boosh’s musical arrangements); Fielding hoped to become an artist (he designed the Boosh book cover and throughout our interview sketches obsessively). Instead they threw their talents into comedy. Barratt: “It is a great means of getting your ideas over instantly.” Fielding: “Yes, it is quite punk in that way.”

Their 1998 Edinburgh Fringe show called The Mighty Boosh was named, obscurely, after a friend’s description of Michael Fielding’s huge childhood Afro: “A mighty bush.” While their double-act banter has an old-fashioned dynamic, redolent of Morecambe and Wise, the show threw in weird characters and a fantasy storyline in which they played a pair of zookeepers. They are very serious about their influences. “Magritte, Rousseau...” says Fielding. “I like Rousseau’s made-up worlds: his jungle has all the things you’d want in a jungle, even though he’d never been in one so it was an imaginary place.”

Eclectic, weird and, crucially, unprepared to compromise their aesthetic sensibilities, it was 2004 before, championed by Steve Coogan’s Baby Cow production company, their first series aired on BBC3. Through repeats and DVD sales the second series, in which the pair have left the zoo and are living above Naboo’s shop, found a bigger audience. Last year the first episode of series three had one million viewers. But perhaps the Boosh’s true breakthrough into mainstream came in June when George Bush visited Belfast and a child presented him with a plant labelled “The Mighty Bush”. Assuming it was a tribute to his greatness, the president proudly displayed it for the cameras, while the rest of Britain tittered.

A Boosh audience these days is quite a mix. In Sheffield the front row is rammed with teenage indie girls, heavy on the eyeliner, who fancy Fielding. But there are children, too: my own sons can recite whole “crimps” (the Boosh’s silly, very English version of rap) word for word. And there are older, respectable types who, when I interview them, all apologise for having such boring jobs. They’re accountants, IT workers, human resources officers and civil servants. But probe deeper and you find ten years ago they excelled at art A level or played in a band, and now puzzle how their lives turned out so square. For them, the Boosh embody their former dreams. And their DIY comedy, shambolic air, the slightly crap costumes, the melding of fantasy with the everyday, feels like something they could still knock up at home.

Indeed, many fans come to gigs in costume. At the Mighty Boosh Festival 15,000 people came dressed up to watch bands and absurdity in a Kent field. And in Sheffield I meet a father-and-son combo dressed as Howard Moon and Bob Fossil – general manager of the zoo – plus a gang of thirty-something parents elaborately attired as Crack Fox, Spirit of Jazz, a granny called Nanageddon, and Amy Housemouse. “I love the Boosh because it’s total escapism,” says Laura Hargreaves, an employment manager dressed as an Electro Fairy. “It’s not all perfect and people these days worry too much that things aren’t perfect. It’s just pure fun.”

But how to retain that appealingly amateur art-school quality now that the Boosh is a mega comedy brand? Noel Fielding is adamant that they haven’t grown cynical, that The Mighty Book of Boosh was a long-term project, not a money-spinner chucked out for Christmas: “There is a lot of heart in what we do,” he says. Barratt adds: “It’s been hard this year to do everything we’ve wanted, to a standard we’re proud of... Which is why we’re worn to shreds.”

Comedy is most powerful in intimate spaces, but the Boosh show, with its huge set, requires major venues. “We’ve lost money every day on the tour,” says Fielding. “The crew and the props and what it costs to take them on the road – it’s ridiculous. Small gigs would lose millions of pounds.”

The live show is a kind of Mighty Boosh panto, with old favourites – Bob Fossil, Bollo, Tony Harrison, etc – coming on to cheers of recognition. But it lacks the escapism to the perfectly conceived world of the TV show. They have told the BBC they don’t want a fourth series: they want a movie. They would also, as with Little Britain USA, like a crack at the States, where they run on BBC America. Clearly the Boosh needs to keep evolving or it will die.

Already other artists are telling Fielding and Barratt to make their money now: “They say this is our time, which is quite frightening.” I recall Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer, who dominated the Nineties with Big Night Out and Shooting Stars. “Yes, they were massive,” says Fielding. “A number one record...” And now Reeves presents Brainiac. “If you have longer-term goals, it’s not scary,” says Barratt. “To me, I’m heading somewhere else – to direct, make films, write stuff – and at the moment it’s all gone mental. I’m sort of enjoying this as an outsider. It was Noel who had this desire to reach more people.”

Indeed, the old cliché that comedy is the new rock’n’roll is closest to being realised in Noel Fielding. Watching him perform the thrash metal numbers in the Boosh live show, he is half ironic comic performer, half frustrated rock god. His heroes weren’t comics but androgynous musicians: Jagger, Bowie, Syd Barrett. (Although he liked Peter Cook’s style and looks.)

“I like clothes and make-up, I like the transformation,” he says. Does it puzzle him that women find this so sexually attractive? “I was reading a book the other day about the New York Dolls and David Johansen was saying that none of them were gay or even bisexual, and that when they started dressing in stilettos and leather pants, women got it straight away with no explanation. But a lot of men had problems. It’s one of those strange things. A man will go, ‘You f***ing queer.’ And you just think, ‘Well, your girlfriend fancies me.’”

The Boosh stopped signing autographs outside stage doors when it started taking two hours a night. At recent book signings up to 1,500 people have shown up, some sleeping overnight in the queue. And on this tour, the Boosh took control of the after-show parties, once run as money-spinners by the promoters, and now show up in person to do DJ slots. I ask if they like to meet their fans, and they laugh nervously.

Fielding: “We have to be behind a fence.”

Barratt: “They try to rip your clothes off your body.”

Fielding: “The other day my girlfriend gave me this ring. And, doing the rock numbers at the end, I held out my hands and the crowd just ripped it off.”

Barratt: “I see it as a thing which is going to go away. A moment when people are really excited about you. And it can’t last.”

He recalls a man in York grabbing him for a photo, saying, “I’d love to be you, it must be so amazing.” And Barratt says he thought, “Yes, it is. But all the while I was trying to duck into this doorway to avoid the next person.” He’s trying to enjoy the Boosh’s moment, knows it will pass, but all the same?

In the hotel bar, a young woman fan has dodged past Danny and comes brazenly over to Fielding. Head cocked attentively like a glossy bird, he chats, signs various items, submits to photos, speaks to her mate on her phone. The rest of the Boosh crew eye her steelily. They know how it will end. “You have five minutes then you go,” hisses one. “I feel really stupid now,” says the girl. It is hard not to squirm at the awful obeisance of fandom. But still she milks the encounter, demands Fielding come outside to meet her friend. When he demurs she is outraged, and Danny intercedes. Fielding returns to his seat slightly unsettled. “What more does she want?” he mutters, reaching for his wine glass. “A skin sample?”

#I hadn't seen this one before so I thought I'd share#noel will never dress down#ah yes the patient boyfriend Julian Barratt

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickfields Meadow

Pond/Lake.

Tennison Road

South Norwood SE25

7.10.21

Brickfield meadow is a public open space in South Norwood behind a secluded entrance which means very few people are aware that it even exists. It was formally the site of Woodside brickworks, which was a product of the area’s Victorian industrial heritage as the clay used to be dug out and fired into building materials. In the 1930s, one million bricks were being made every week. Croydon council took control of the site in the early 1990s. The whole area of the meadow covers a size of 10 acres. The pond/Lake is a bit of a surprize as it is quite big, deep, and filled with a great variety of different fish, the fish vary in size and include Rudd, Roach Perch, and carp, the advice is to fish around the borders and banks and in and under the branch’s weedy areas around the rocks.

The main part of the pond was an old clay pit and when the clay run out, clay was then taken from the Victoria line underground tunnels to make bricks. There is also a smaller more natural pond that leads into the large one under a wooden bridge. It also boasts a healthy population of waterfowl, including moor hen and many birds can be heard to be singing in the otherwise quiet and peaceful place. As well as the pond/Lake, there is a Buddleia valley, grassland, woodland areas, woodland planting, a small children’s play area which includes a mini maze and is surrounded by new housing. Fishing is allowed and dipping platforms are provided, however, eating of the fish is not recommended and swimming is not allowed as the lake is unkempt with rubbish and fly tipping taking place in the pond, at one point (2013), even an abandoned car could be seen in the water.

After one clean up in 2018 a whole living room was found, complete with T.V., this has resulted in cloudy brown water. There is a community group that has formed to try and maintain the meadow and raise funds for this. This is one of my favourite paces to sit and relax as it is so quite and chilled with few people around as no one knows about it. Its my very own escape from the hassle and bustle of life.

0 notes

Photo

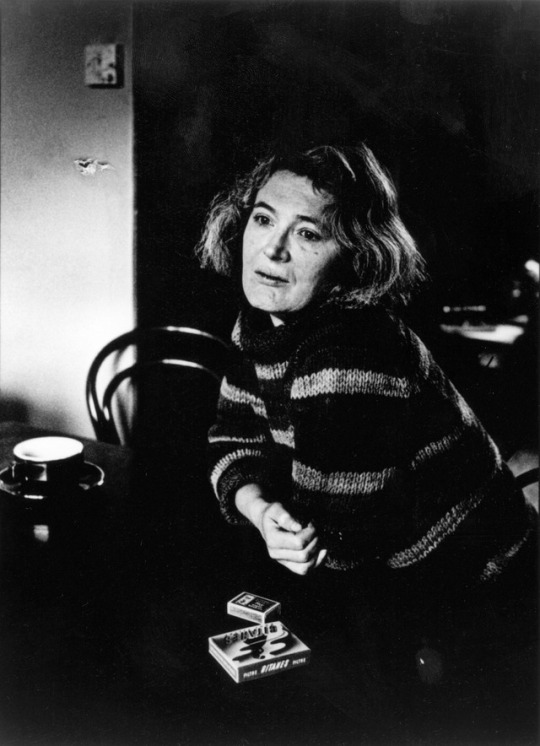

She Escaped To Become Original.

The relationship between a biographer and his or her subject often takes the form of a one-sided love affair. When the subject is a person of ill repute or a criminal the chances of an attachment are of course less—the most that may usually be managed is a fascinated repulsion. But with a writer, ardent involvement is almost always present, at least at first. After all, the lover and the beloved already share a profession, and the biographer cannot help but feel that he or she understands the subject’s inner life and professional struggles. The fact that this is in effect a love affair is often confessed in public and also in print, at the very end of the acknowledgments in the finished book, when, after thanking interviewees and researchers and editors, the biographer apologizes to his or her spouse or partner for what sounds rather like an adulterous affair, one that diverted time and attention, if not affection and passion, from a real-life partner.

These imaginary adulteries are not one-night stands. The average serious literary biography appears to take about five years of research and writing, and ten years or even more are common when it runs to two or three volumes. Almost always the task involves extensive travel, hours hunched over a computer while your partner or family go on with their lives, and long conversations with strangers in expensive restaurants, bars, and coffee shops. Edmund Gordon is clearly a serious and gifted biographer. He has worked hard, traveling all over the world to speak to people who knew Angela Carter and reading every scrap of her writing he could find. His title, The Invention of Angela Carter, announces both that Carter was a tremendously original writer with a marvelous gift of invention and that, as he puts it, “The story of her life is the story of how she invented herself.”

Gordon discusses Carter’s writing with skill and sense. He also manages to make her self-invention understandable and even sympathetic. He does not leave anything out, but he does sometimes include so much prosaic detail—the names of people she knew, the geography of the places she lived—that astonishing information sometimes flares up like a burst of flame on a damp log. You put the book down, asking yourself: Wait a second. Did he just say that after she slept with the husband of one of her best friends, Jenny, Carter wrote in her journal:

It is good for my ego (happiness is ego-shaped) to see myself as [John] sees me, a sweet, cool, flower in the sun; &, especially as [Jenny] sees me, an exotic, treacherous femme fatale…. I wish Jenny would try to kill herself.

One way to understand this sort of thing is to see it as a statement from someone who is trying to reinvent herself after a truly oppressive childhood. Psychologists have suggested that there are two classic early fears, both deftly portrayed in the folktale “Hansel and Gretel”: the fear of being abandoned and the fear of being consumed. For most of us, one of these anxieties is dominant. Angela Carter grew up with a mother who, like the witch in the fairy tale, overfed and confined her. According to Gordon, “She was an intensely loved and thoroughly spoiled child, heaped with gifts and goodies:…chocolate and ice cream and books…. She was never put to bed until after midnight.” Soon Angela was a very fat little girl who at eight already weighed “six or seven stone” (between eighty-four and ninety-eight pounds), with a bad stammer and no friends.

Her father, who worked as a night editor for the Press Association, was seldom home, and outside of school hours Angela spent most of her time with her mother, Olive, who monitored her every move: “Even when she was ten or eleven, she wasn’t allowed to go to the lavatory on her own. She was made to wash with the bathroom door open well into her teens.” She was also forbidden to go out with boys, and spent most of her free time at home, reading and writing stories. It is not surprising that her early novels and tales often feature lonely girls who are imprisoned in sinister houses or castles.

What is most remarkable is that Carter was able to escape from the gingerbread house. When she was seventeen she suddenly went on a serious diet. Gordon, though he puts this politely, does not quite believe her claim of having become an anorexic and weighing less than eighty pounds, since none of the friends or relatives he interviewed confirmed it. But in any case she eventually stopped dieting and settled into the normal weight range for her height. She also began to defy her parents: “She came to enjoy provoking Olive, and saying whatever she thought would go down worst, usually something iconoclastic, blasphemous or obscene.” It was a game Carter continued to play with anyone who struck her as pretentious or uptight, and one, according to reports, she never ceased to take pleasure in.

Angela Carter was a brilliant student, and her teachers encouraged her to apply to Oxford; but she refused after Olive declared that if she was admitted they would rent a house there to be close to her. When she left school at eighteen, her father found her a job on a local newspaper, the Croydon Advertiser. Angela Carter took the job, she later said, “kicking and screaming,” though soon began to enjoy it. But she was still living at home and quarreling with her parents. She was miserable and full of self-hatred: later she described herself as having been at the time “a great, lumpy, butch cow, physically extremely clumsy, titless and broadbeamed.”

She was also, obviously, a very determined and courageous person. Not only did she transform herself, in a few months, from a fat, frightened, awkward teenager into a skinny Goth beatnik, she managed to escape from Croydon. In 1959, at nineteen, she met her first boyfriend, a twenty-seven-year-old industrial chemist and folk music fan called Paul Carter, and the following year she married him. In 1961 Paul got a job teaching at what would become City of Bristol College, and she moved finally and decisively out of her parents’ claustrophobic world. She began taking courses toward a college degree, and in 1962 published her first short story.

All was not well, however. As Angela Carter later wrote in her journal, “Marriage was one of my typical burn-all-bridges-but-one acts; flight from a closed room into another one.” Though they seem to have been happy at first, she and Paul were not temperamentally suited; Paul was given to “gloomy spells and touchy, drawn-out silences.” He resented her (lifelong) reluctance to do any housework, though she was an enthusiastic and gifted cook.

Once she had finished her degree, most of Angela Carter’s time was devoted to writing. “My first husband wouldn’t let me get a job after I graduated from university,” she said in 1980. “So I stayed at home and wrote books instead, which served the bugger right.” Gordon tactfully calls this an “exaggeration,” and reports that in fact Paul, who “was never very supportive of her writing,” seems to have put pressure on Angela to find a job. Luckily for her readers, he did not succeed, and over the next decade she published three novels and dozens of articles and stories.

Edmund Gordon has admirably avoided what is known as the biographical fallacy: the attempt to explain a writer’s work by the facts of his or her life. But a reviewer, whose observations will soon dissolve into wastepaper and weak electronic pulses, can be more casual and speculative. It seems quite likely to me that a fat, clever girl with no friends who spends the first seventeen years of her life in a gingerbread house in suburban middle-class South London, reading avidly and incessantly, will have limited experience of life. Her conceptual world, on the other hand, may be rich and full and colorful, populated by the dramatic characters and events—both historical and fictional—that have excited her imagination.

Most writers take off from the worlds they have known. Angela Carter’s stories and novels, on the other hand, can be seen as inspired principally by dramatic historical figures like Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe and Lizzie Borden, plus a rich imaginative universe of witches and ghosts and princes and princesses, magicians and clowns, werewolves and vampires, mad scientists and evil aristocrats, incestuous siblings, and murderous seducers. It is a world that would make her simultaneously one of the most derivative and the most original of writers.

Angela Carter’s first published story, “The Man Who Loved a Double Bass,” was a remarkable achievement for a twenty-two-year-old. Its hero hangs himself when his beloved instrument is destroyed. Already, the prose is strikingly good: “Darkness came with the afternoon, dragging mist with it…. [It] fell around their shoulders like a rain-soaked blanket.”

Her first three novels, Shadow Dance (1966), The Magic Toyshop (1967), and Several Perceptions (1968), are set in contemporary Bristol and London, in an intensely emotional counterculture landscape of disguise and artifice, sex, and violence, and they were well reviewed. Later she ranged further in space and time, often setting her stories in a world of fantastic characters and melodramatic events, vast wealth, and violent passions; a world as far as possible from the one she had grown up in. As she put it in her appendix to the story collection Fireworks (1974):

I’d always been fond of…Gothic tales, cruel tales, tales of wonder, tales of terror, fabulous narratives that deal directly with the imagery of the unconscious—mirrors; the externalized self; forsaken castles; haunted castles; forbidden sexual objects.

Carter’s new persona was equally vivid. She started dyeing her drab brown hair with henna, and for the next twenty years was a striking five-foot-nine redhead. She dressed dramatically, often in black, chain-smoked, and liked to say shocking things and use coarse words. She claimed to despise classic authors like Henry James and W.B. Yeats, and “formed an intense dislike for Jane Austen.” Her attitude toward contemporary British writers, especially women, was unfriendly: at a public reading she went up to the realistic novelist A.S. Byatt, whom she had never met, and said: “My name’s Angela Carter. I recognized you and I wanted to stop and tell you that the sort of thing you’re doing is no good at all. There’s nothing in it—that’s not where literature is going.” But she was not always comfortable with the impression she was making, and wrote in her journal:

I talk about myself too much instead of watching other people, I try & exhibit my own original and exciting personality—whereas I am, in fact, merely a stupid young bitch…

Soon Angela Carter had a reputation as someone who would say anything and take any risk. It was not all talk: when Several Perceptions won a prize of £500 in 1969, she used the money to go to Japan for a month, although she knew no one there and could speak no Japanese. Halfway through her stay she met a twenty-four-year-old college dropout called Sozo in a coffee-house, and went with him to a Tokyo “love hotel.” Almost at once, she was in love. When she returned to England two weeks later she did not return to her husband Paul. She also did not see her parents until that December, when she heard that her mother was in the hospital with a heart attack. According to Gordon, Olive “took one look at her and turned her face to the wall.” She died soon after, having cut her daughter out of her will.

In April 1971 Carter moved to Japan to live with Sozo, first in Tokyo and then in a nearly deserted winter beach resort where she began to write her controversial magic-realist fantasy, The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972), which a few readers, including Salman Rushdie, consider her best work. Others have found it both lurid and baffling. As Gordon says, it is set in “a dream-version of Tokyo” in which the narrator-hero, Desiderio, who is based on Sozo, pursues the evil Dr. Hoffman through a series of fantastic supernatural worlds full of exotic and in some cases violent and cruel sexual customs, all graphically described.

Passionate as it was, Carter’s relationship with Sozo had problems. Sozo was younger than she, and not really ready to settle down. As a Japanese man, he expected a woman to stay home at night and mind the house while he went out drinking with friends, often not returning until the following morning.

In April 1972, Carter went back to England to do publicity for her newest novel, Love. When she returned to Tokyo a little over two months later, Sozo was not there to meet her as he’d promised. When she finally tracked him down, he told her that he had slept with three women while she’d been away. A week afterward the affair was over. Carter always maintained that the break was her idea, but Gordon does not believe this. For the first time in her life she was the rejected one, and it hit her hard:

She returned to worrying that she was unattractive and unlovable, and that her work wasn’t any good. All the same, she had enough self-awareness to realise that she hadn’t objectively changed when Sozo left her.

She stayed on in Japan, writing and seeing expatriate friends; for a week she worked as a bar hostess, but quit when she found she was expected to go home with at least some of the patrons. In November 1972 she took up with a nineteen-year-old Korean called Kō who spoke very little English. The relationship made her happy, but she didn’t take it very seriously, though she did spend the New Year holidays with him and his parents in Osaka. In the spring she returned to England; Kō desperately wanted to go with her but she discouraged him. Back home she wrote in her journal, almost as Lieutenant Pinkerton might have written of Madame Butterfly:

I can’t think what will come next or who will come next; Kō is in my heart, for ever, and maybe I do not want time to blur his perfection at nineteen, his warm, clean, golden flesh, his eyes like the hearts of anemones…. You can’t possess people; you only borrow them for a time.

Carter’s stay in East Asia was the source not only of The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman but of two of her most brilliant early stories, “A Souvenir of Japan” and “The Smile of Winter.” They are clearly autobiographical: the narrator sees her lover in great detail, but as an object. “I should have liked to have had him embalmed and been able to keep him beside me in a glass coffin, so that I could watch him all the time….” She realizes that both of them are engaged in a kind of intense sex tourism. “He found me, I think, inexpressibly exotic.” She is also enthralled by the mannerist style and elegant formality of Japan, and eager to take part in the performance: “Here we all strike picturesque attitudes and that is why we are so beautiful.” The darker side of the culture especially fascinates her: “This country has elevated hypocrisy to the level of the highest style. To look at a samurai, you would not know him for a murderer, or a geisha for a whore.”

After Angela Carter returned to live in London in 1972, her reputation and confidence increased. She published more novels and many stories, essays, and reviews, and bought a house in South London. The Company of Wolves (1984) and The Magic Toyshop (1987), two films based on her work, appeared; she joined the board of Virago Books and was recognized as one of Britain’s leading feminist writers. In the fall of 1974 she met a young carpenter from Bristol called Mark Pearce who was working on the house across from hers. Angela described him as looking “like a werewolf,” but in fact he was essentially stable and kind. They soon became lovers, and Mark moved in with her. They would be together for the rest of her life, and he was the father of her son Alex, born in 1983.

The most difficult task for a biographer, in the long run, is not how to write both sympathetically and honestly about a subject’s bad times and bad behavior, but how to keep the reader’s attention when all the news is good. As Penelope Fitzgerald put it, “The years of success are a biographer’s nightmare.” Gordon’s book inevitably loses some of its dramatic interest as he reaches the years when Angela Carter was living happily with Mark and Alex. Now we hear a steady rising melody of achievement and recognition: respectful interviews, favorable reviews, escalating advances and sales, meetings with other famous people, trips to writers’ conferences, literary and film and theater projects, and well-paid gigs as a visiting writer at top universities all over the world.

At the same time, a new Angela Carter gradually emerged. She stopped dyeing her hair and wearing all black. I remember her during this period at a literary festival in the garden at Charleston, the former home of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell: a tall, slightly smiling woman with long white hair in a long pale blue sweater and a flowered Liberty print skirt, like a benevolent ghost from the Bloomsbury years.

But it was not just Carter’s outward appearance that had changed: now she was often described by journalists as a warm, affectionate wife and mother, and/or a wise, generous, and benevolent white witch or fairy godmother, with magical narrative and imaginative powers. According to people who knew her well, and to her biographer, this wasn’t a pose. It seems very likely: after all, happiness is usually good for the character. “I haven’t always been nice,” she used to say to interviewers, but nobody believed her. Though she never became close to any contemporary woman writer, she was loved and admired by her agent, her editor, and many friends.

Meanwhile her reputation kept on growing. In 1979 she published two of her best and most famous works: The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography and The Bloody Chamber. The first is a remarkably erudite and ardent examination of the way that men have limited women to the roles of victim and victimizer, or virgin and whore, with a proposal for an alternative myth in which a good woman can be both strong and passionate; it is still widely read and a set text in college courses.

The second, The Bloody Chamber, dramatically illustrated these ideas. It is a brilliant revision of some of Grimm’s best-known stories, and presents striking alternatives to the characters and plots of the old tales. In the title story, the bride of the wicked marquis, a Bluebeard figure, is rescued not by her brothers, as in the original, but by her mother, who rides into the castle on a rearing horse and shoots the murderous husband with a revolver as he is about to cut off her daughter’s head. In “The Tiger’s Bride,” a revised version of “Beauty and the Beast,” the Beast does not become human; instead Beauty joyfully, and perhaps metaphorically, turns into a tiger herself.

In Angela Carter’s next two novels, Nights at the Circus (1984) and Wise Children (1991), she continued to take off from the historical and literary persons and scenes that had always inspired her. But now she moved from the exotic and fantastic worlds of her earlier work into a more familiar and local territory. Instead of Surrealism and fairy tales, she drew on Shakespeare and music-hall comedy. In Nights at the Circus there are still both historic and fantastic elements: its narrator is a journalist based on the young Jack London; and its heroine, Fevvers, is a trapeze artist who can really fly. But in both books the setting is essentially the real world—a world of theatrical boardinghouses, provincial road companies, backstage romance, Christmas pantomime, Cockney hoofers and comics, stage magicians, singers, charwomen, and taxi drivers. Angela Carter celebrates not exotic, erotic violence, but working-class humor and vulgarity, loyalty and courage and comradeship.

The title characters in Wise Children, the identical twins Dora and Nora Chance, are based on two real-life music hall performers, the Dolly Sisters. Now they are tough, wise old Cockneys who still sometimes, in their local pub, burst into song and dance from their old routines. They are the illegitimate twin daughters of a family of Shakespearean actors, the Hazards, whose last name is an upmarket synonym of theirs. In some ways the book is like a night at a Victorian music hall or early cinema. Melodramatic events are thick underfoot: murder, suicide, extravagant parties, intense sexual encounters, burning mansions, and the return of characters presumed dead, but everything turns out all right in the end. Gordon manages his subject’s years of success as well as anyone could, leavening the list of achievements with quotes and anecdotes, but he doesn’t really escape the problem. It is in a way his good fortune as a biographer, and our great misfortune as readers, that this period of Angela Carter’s life was short. In March 1991 she was diagnosed with lung cancer. “Things happened very quickly after that,” she wrote to a friend. In order to make sure that Mark would have custody of their son Alex, they married in May 1991. She worked whenever she could, planning a new novel and collecting the best of her articles for the book that appeared in 1992 as Expletives Deleted. But in less than a year she was dead.

As soon as Angela Carter was gone a flock of fans and critics of all kinds descended upon the body of her work. It was naturally attractive to them: not only was it highly original and imaginative, it drew both from folklore and from history. It was full of dramatic stock characters and events, both real and traditional, and therefore encouraged comparison and interpretation. Feminists, postfeminists, structuralists, poststructuralists, anthropologists, Freudians, and Jungians came to feast and praise, to interpret and overinterpret. As more schools of criticism appear, no doubt they too will be drawn to this tasty and inexhaustible meal. And why shouldn’t they be? At the very least, they will encourage the reading and rereading of one of the twentieth century’s most gifted and original writers.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

A few days after the Jewel in the Claw, a Silent Eye workshop back in 2018, I was lucky enough to have a visit from the queen. Not, I hasten to add, the one who currently wears the crown, but from my friend who had played Elizabeth I at the workshop, along with the gentlemen who had embodied the characters of ‘Sir Walter Raleigh’ and ‘ Dr Dee’.

As we are all stuck inside at the moment, and as I took them to visit the big house in the village, I thought it would be a good moment to re-share our visit to Waddesdon Manor, the improbable French chateau that graces my little village.

The Manor was built in the last half of the nineteenth century by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, as a place to entertain his guests and to house his art collection. On his death in 1957, James de Rothschild bequeathed the house and its contents to the National Trust, but it remains managed by the charitable Rothschild Foundation.

The house is set in a beautiful garden that combines the natural with the sculpted, but within the fairytale walls, there is art beyond imagining, from the innumerable clocks of every style and material, from inlaid ebony to the fantastical elephant automaton, to the porcelain, sculpture and art. There is not one thing within the house that is not, in its own way, both exquisite in its artistry or workmanship, and redolent with history.

There are carpets from Versailles, pearl handled rifles, Meissen, and whole rooms devoted to Sèvres porcelain, each piece hand painted with different flowers and birds.

There are more paintings by Reynolds than you are ever likely to see in one place, as well as pieces so famous that your jaw drops to find they live in your village and are your neighbours… like Boucher’s Madame de Pompadour, hung, with either romance or humour, above a bust of her lover, Louis XV of France.

There are staterooms, dining rooms, billiard rooms and every other conceivable type of room, all open to the public and fairly oozing opulence. It is not a home, it is a gallery and yet, there is something about the place that speaks of love and care.

After the death of its builder, Baron Ferdinand, the Manor passed to his sister, Alice, who added to the art collection and cherished the house as a memorial to her brother. When Alice died in 1922, the Manor passed to her nephew, James, who further added to the collection and later bequeathed it to the National Trust.

It was never a place designed to hold a family and only ever housed children during the war years, when pre-school children from Croydon, south of London, were evacuated to the Manor to escape the Blitz. James and his wife, Dorothy, also offered the sanctuary of the Manor to a group of Jewish boys from Germany.

The Rothschild family continue to play a philanthropic part in the life of the village and the Manor is the largest local employer. The Home Farm is still worked, the land managed and a new facility to house, educate and showcase modern art was built on the estate a few years ago.

The house has seen many illustrious visitors over the years. Some, like Queen Victoria, were guests. She was fascinated by the newly installed electric lighting and commemorated her visit with the gift of a portrait bust of herself that still sits on a side table.

Others have included members of high society, politics and royalty and, more recently, stars of music, stage and screen. The Manor has been used as a filming location for everything from the O’Connell’s home in The Mummy III to Downton Abbey, Howard’s Way and even one of the Carry On films, to mention but a few.

Today it is still a place where art and culture flourish, with regular exhibitions, theatrical productions and modern art installations in the grounds, where, as a villager, I get to wander for free to my heart’s content.

With all the splendour and fantastic, priceless art that make this such a rich resource on my doorstep, I would never have been able to choose one favourite thing…until this visit, and that was a very human moment.

Our ‘Dr Dee’ had once been known, at the Renaissance Faire, for his embodiment of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and a lifelong love of Queen Elizabeth I. To our surprise and delight, the most iconic portrait of the sixteenth century knight hung on the wall beside that of his queen. To see my friend stand gazing face to face across the centuries, was a beautiful thing and a moment I shall not soon forget.

And that, I think, was the lesson I took from the day… that amid all the magnificence, it is only the human stories that matter. It is the smile of the Pompadour who captivated a king, the hand of the potter who shaped a curious bear jug, the attention of the porcelain painter whose birds are themselves flights of imagination, the love of a sister who preserved the house for her brother’s memory and the quiet, untold stories of the men, women and children who have walked these gracious halls throughout the years.

From the villagers who volunteer as guides, to the housekeepers and gardeners who maintain the Manor… from the visitors who have gasped in awe or decried the obscenity of ostentation, to the stage fright of actors and the satisfaction of artists creating art from light and flowers… every object, every painting, every breath and footstep tells a human story, if we look beyond its surface. And there, I believe, lies the true beauty of this place.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

A right royal visit… A few days after the Jewel in the Claw, a Silent Eye workshop back in 2018, I was lucky enough to have a visit from the queen.

#art collection#Boucher#Dudley#Elizabeth I#Pompadour#Queen Victoria#Reynolds#Rothschild#Sevres#Waddesdon manor

0 notes

Text

Interior and Exterior Light Installation Melbourne

Looking to spruce up your patio or bring dimension to your living room? Lighten up your dining room to really show off the food you spent hours cooking. Playing with your lighting design is a fantastic way to make drastic changes to your space, at a very reasonable cost. Fisher Brothers light installation experts in Melbourne can assist you every step of the way.

about the light installation melbourne experts

Fisher Brothers Electrical is a family owned company, specializing in indoor and outdoor lighting installation. Safety and security are their highest priority. Providing excellent customer service and guaranteed value for their customers is a close second, and this includes being on time, every time they have an appointment. They have become known as experts in their industry over time, with dedication to their customers, and good, old-fashioned hard work.

domestic electrical services

Fisher Brothers provides both interior and exterior lighting installation services. The Domestic division of this company is made up of skilled and trained professionals. The primary focus of this team is offering solutions for lighting installation and electrical needs. With over 35 years in the electrical industry, this team is highly-skilled, and very passionate about providing you with the perfect lighting solutions for your home.

interior light installation melbourne

This Melbourne company can update the interior of your home to provide the atmosphere you want to create. From a fun, creative atmosphere, to a quite peaceful one, Fisher Brothers Electrical has got your back.

The lighting in your home says a lot about your personality. Do you have the latest trends? Is your lighting classic? Or do you prefer a more vintage style? Or a theme? These light installation Melbourne specialists can fit your lighting to your personality.

exterior light installation melbourne

Do you spend time in your garden? Or on your deck, or in your courtyard? Fisher Brothers Electrical can style the lighting in your outdoor space to reflect the mood you wish to create. Have you always dreamed of having that oasis that you can escape to when you need a break from reality? Now you can have that retreat.

Whether you are looking to create a focal point or hide your garden in shadows with silhouettes floating on the breeze, this team can provide you with that safe, desirable space you have your heart set on.

light installation melbourne design

The Domestic division works with their customers to provide quality lighting, with energy saving benefits, at a cost you can afford. They take the time to understand what their customer are looking for, by providing a free consultation. This is the time to state your desires and help them understand what you truly want. Once you have given them your “wish list”, Fisher Brothers can design your perfect oasis or amazing indoor lighting scheme. These experts in conceptual lighting understand just how to change a light or place it a certain way in your home or garden to get the desired effect.

Fisher Brothers Electrical has worked hard to become the light installation Melbourne experts in the Melbourne area. Their reputation was earned, and not achieved by accident. It’s through dedication, hard work, and fantastic customer service that this company has excelled. Contact Fisher Brothers Electrical today for your free consultation and let them get started on your next lighting project!

Fisher Brothers Electrical Contractors are reliable, honest and friendly. Some of the services we offer include:

Thermal Imaging Melbourne

Domestic Electrician Melbourne

Home Alarm Installation

Electrical Wiring

TV Antenna Installation

CTV Installation Melbourne

Electrician Melbourne

Security Camera Installation

Light Installation Melbourne

Home Automation Melbourne

Home Security Melbourne

Smoke Alarm Installation Melbourne

We service all areas of Melbourne. Below are just a few examples of suburbs that we provide service in. If you are unsure if we service your area, please contact our friendly office on: 03 9532 0681

Electrician Carrum Downs, Electrician Aspendale. Electrician Carrum, Electrician Bonbeach, Electrician Chelsea, Electrician Braeside, Electrician Moorabbin, Electrician Mordialloc, Electrician Mentone,Electrician Cheltenham, Electrician Clarinda, Electrician Clayton South, Electrician Dingley Village,Electrician Edithvale, Electrician Heatherton, Electrician Aspendale Gardens, Electrician Chelsea Heights, Electrician Highett, Electrician Moorabbin Airport, Electrician Parkdale, Electrician Patterson Lakes, Electrician Waterways, Electrician Clayton, Electrician Chadstone, Electrician Hughesdale,Electrician Ashwood, Electrician Glen Waverley, Electrician Huntingdale, Electrician Mount Waverley,Electrician Mulgrave, Electrician Notting Hill, Electrician Oakleigh, Electrician Ormond, Electrician Wheelers Hill, Electrician Murrumbeena, Electrician Bentleigh, Electrician Caulfield, Electrician Carnegie, Electrician Elsternwick, Electrician Gardenvale, Electrician Glen Huntly, Electrician Mckinnon, Electrician Lyndhurst, Electrician Noble Park, Electrician Bangholme, Electrician Dandenong,Electrician Keysborough, Electrician Springvale, Electrician Karingal, Electrician Skye, Electrician Seaford, Electrician Kananook, Electrician Langwarrin, Electrician Frankston, Electrician Clyde,Electrician Berwick, Electrician Cranbourne, Electrician Devon Meadows, Electrician Doveton,Electrician Endeavour Hills, Electrician Pearcedale, Electrician Beaumaris, Electrician Black Rock,Electrician Brighton, Electrician Hampton, Electrician Armadale, Electrician Glen Iris, Electrician Kooyong, Electrician Malvern, Electrician Prahran, Electrician South Yarra, Electrician Toorak,Electrician Windsor, Electrician Hawthorn, Electrician Kew, Electrician Sandringhan, Electrician Albert Park, Electrician Balaclava, Electrician Elwood, Electrician Middle Park, Electrician Beacon Cove,Electrician Garden City, Electrician Ripponlea, Electrician St Kilda, Electrician Port Melbourne, Electrician Southbank, Electrician South Melbourne, Electrician Abbotsford, Electrician Alphington,Electrician Burnley, Electrician Carlton North, Electrician Clifton Hill, Electrician Collingwood, Electrician Cremorne, Electrician Fairfield, Electrician Fitzroy, Electrician Princes Hill, Electrician Richmond,Electrician Bellfield, Electrician Briar Hill, Electrician Bandoora, Electrician Eaglemont, Electrician Eltham North, Electrician Greensborough, Electrician Heidelberg, Electrician Heidelberg Heights, Electrician Heidelberg West, Electrician Ivanhoe, Electrician Ivanhoe East, Electrician Lower Plenty, Electrician Macleod, Electrician Montmorency, Electrician Rosanna, Electrician St Helena, Electrician Viewbank,Electrician Watsonia, Electrician Yallambie, Electrician Mt Cooper, Electrician Kingsbury, Electrician Northcote, Electrician Preston, Electrician Reservoir, Electrician Thornbury, Electrician Aberfeldie,Electrician Airport West, Electrician Ascot Vale, Electrician Avondale Heights, Electrician Essendon,Electrician Flemington, Electrician Newmarket, Electrician Keilor East, Electrician Kensington, Electrician Monee Ponds, Electrician Niddrie, Electrician Strathmore, Electrician Travancore, Electrician Brunswick,Electrician Moonee Vale, Electrician Coburg, Electrician Fawkner, Electrician Glenroy, Electrician Gowanbrae, Electrician Hadfield, Electrician Oak Park, Electrician Pascoe Vale, Electrician Tullamarine,Electrician Mont Albert, Electrician Surrey Hills, Electrician Canterbury, Electrician Camberwell,Electrician Deepdene, Electrician Ashburton, Electrician Balwyn, Electrician Ferntree Gully, Electrician Knoxfield, Electrician Boronia, Electrician Bayswater, Electrician Lysterfield, Electrician Rowville,Electrician Scoresby, Electrician Wantirna, Electrician Bulleen, Electrician Doncaster, Electrician Donvale, Electrician Park Orchards, Electrician Templestowe, Electrician Warrandyte, Electrician Ringwood, Electrician Croydon, Electrician Heathmont, Electrician Blackburn, Electrician Box Hill,Electrician Burwood, Electrician Forest Hill, Electrician Mitcham, Electrician Nunawading, Electrician Vermont, Electrician Chirnside Park, Electrician Pakenham, Electrician Officer, Electrician Mornington,Electrician Mount Eliza, Electrician Baxter, Electrician St Albans, Electrician Keilor, Electrician Sunshine,Electrician Albion, Electrician Thomastown, Electrician Mill Park, Electrician Lalor, Electrician Epping,Electrician Ardeer, Electrician Broadmeadows, Electrician Campbellfield, Electrician Jacana,Electrician Gladstone Park, Electrician Westmeadows, Electrician Cairnlea, Electrician Deer Park,Electrician Delahey, Electrician Derrimut, Electrician Kealba, Electrician Altona, Electrician Brooklyn,Electrician Newport, Electrician Spotswood, Electrician South Kingsville, Electrician Williamstown,Electrician Braybrook, Electrician Footscray, Electrician Kingsville, Electrician Maidstone, Electrician Maribyrnong, Electrician Seddon, Electrician Tottenham, Electrician West Footscray, Electrician Yarraville, Electrician Docklands, Electrician Carlton, Electrician East Melbourne, Electrician North Melbourne, Electrician Fishermans Bend, Electrician Parkville, Electrician West Melbourne, Electrician Calder Park, Electrician Sydenham, Electrician Taylors Lakes, Electrician Altona Meadows, Electrician Kings Park, Electrician Laverton, Electrician Seabrook, Electrician Seaholme, Electrician Burnside,Electrician Caroline Springs, Electrician Hillside, Electrician Ravenhall, Electrician Taylors Hill, Electrician Truganina, Electrician Williamstown North, Electrician Keilor Downs, Electrician Keilor Park, Electrician Altona North, Electrician Hoppers Crossing, Electrician Tarneit, Electrician Keilor North, Electrician Sunshine North, Electrician Sunshine West, Electrician Laverton North, Electrician Point Cook, Electrician Werribee, Electrician Werribee South, Electrician Wyndham Vale

#Thermal Imaging Melbourne#home theatre installation Melbourne#Domestic Electrician#domestic electrician Melbourne#home alarm installation#Home Security Systems#Electrical Wiring Melbourne#TV Antenna Installation#CCTV Installation Melbourne#TV Antenna Installation Melbourne#T V Antenna Installation#electrical contractors#electrician services#Electrician Melbourne#Commercial Electrician Melbourne#security camera installation#home security installation#Lighting Installation Melbourne#Light Installation Melbourne#home automation melbourne#Home Automation Melbourne#Home Security Alarm#home security camera#Smoke Alarm Installation Melbourne#Air conditioning Installation Melbourne#Melbourne Electrician#electricians melbourne#melbourne electricians#melbourne electrical

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Vintage Designer Handbags Online | Vintage Preowned Chanel Luxury Designer Brands Bags & Accessories

New Post has been published on http://vintagedesignerhandbagsonline.com/i-loved-being-part-of-that-scene-80s-style-tribes-then-and-now-music/

'I loved being part of that scene': 80s style tribes, then and now | Music

Carrie Kirkpatrick and Gill Soper, skinheads (above)

Carrie I got into punk at the age of 12, and went quite wild with it. It was a means of escape from difficult situations at home. I found it empowering; going to gigs and drinking and taking drugs was exciting. I felt free; but I was getting into trouble with the police.

There was a skinhead revival going on, and Gill suggested we get into that instead. Skinheads were more structured, not so wild. We wore smart clothes, we had perfect hair and nails.

I grew up in south London, surrounded by rightwing views. The area had seen a lot of immigration and it was very much a “them and us” attitude. I spent a lot of time making sure I deprogrammed my conditioning around racism. When you’re in a subculture as a kid, you’re doing it for the social scene, for the music, and to find yourself. In your 30s, 40s and 50s, it’s different: you can have shared interests with others, but you don’t have to do everything with them. Your relationships are more sophisticated.

When I showed the original photograph to my son, who is 11, he said, “You don’t look very happy!” But I wasn’t unhappy; I loved being part of that scene. I suppose we were just trying to look hard, weren’t we?

Carrie Kirkpatrick (left) and Gill Soper outside the toilets in Crystal Palace, London, in November 1980 (top) and April 2017 (above). All photographs: Anita Corbin

Gill Between 1978 and 1979, there were so many subcultures to choose from: punk, disco, reggae, mod, 2 Tone. I was a punk originally, but I couldn’t go the whole hog, because I was also into disco. If you turned up at a disco with a blue mohican, you wouldn’t be so welcome.

When you’re young, you latch on to the newest thing, which for us was being a skinhead. Everyone I knew was a punk one day, and then shaving their head and wearing jeans and braces the next.

It was the clothes that drew me. Well, it was the boys to start with, closely followed by the clothes and the music and the attitude. We all had suits made. There were the shirts, the feather cuts, the shoes.

My daughter was born not long after the original picture was taken, and I was “normal” for a while before turning skin again in my 20s. I was clearing out my mum’s house recently and found pictures of my daughter with a feather cut in primary school. She hates me for that. She stayed with my mum a bit, because by that time I had got into scooters and Northern Soul. I’m still into it: it’s a friendly scene and very tight-knit.

I’m 54 now, and things have definitely turned a corner for women my age. Of course, if you want to blend in, you can, but many women have been given a new lease of life. Your experience of age is what you make it, really. I’m going to the hairdressers right now, in fact, I’m having a feather cut and getting it dyed bright red.

‘I still like to be different. I live in a mobile home. I don’t have a TV. I avoid supermarkets’

Shelley Spencer and Di Sage, punks

Shelley Spencer (left) and Di Sage in the toilets at the White Swan, Crystal Palace, in November 1980

Shelley I grew up just outside Croydon in south London. One night, when I was 14, I was at the bus stop on my way to a social club and saw my first punks. One of them had lots of black makeup on, and the other had spiky hair and ripped clothes held together with safety pins. I remember thinking, “Wow.” Over that summer, 1977, I went from riding bikes and horses to going out with my sister and the Croydon Punks. It was huge fun.

I crimped my hair before work every day. I was working at the dole office in King’s Cross and you’d sometimes get musicians coming in to sign on. Dave Vanian from The Damned came in once. I said, “My sister enjoyed your gig last night!” He got all nervous and said, “We don’t get paid, you know,” worried that I would shop him.

Di and I met at school and used to go out three or four nights a week, but we lost touch when I went travelling. After 14 years, we reconnected. Since 2002, I’ve lived in rural France. I look at photos of me as a punk and think, “Ooh, I was quite gorgeous”, and realise that modern society’s view of women in their 50s is very negative.

What the past 36 years has taught me is that you are yourself, whatever else you do. You are not your children’s mother. You are not simply a wife. It is so important to put time aside to remember who you are.

Shelley Spencer (left) and Di Sage in Angoulême, France, in May 2017

Di When I was 17, I had a lot of fire in me. I’d do leaflet drops for the British Union For The Abolition Of Animal Vivisection. As part of a Stop The City protest, us punks would go to phone boxes and all call a number in the City at nine on a Monday morning, so the switchboards were jammed.

Being a punk provided a sense of belonging and of being different. It was fresh, exciting, fiery – and loud. Live music was a huge part of it.

I remember standing at a bus stop with my mother, and people would call me names across the street and she would get upset. People saw punk as aggressive, but I was just expressing myself. I was shy, but I liked to shock.

You’d not be seen dead with your hair flat. You’d do your best, even if it was raining, with a tin of hairspray and an umbrella. I still like to be different. I live in a mobile home, I don’t have a telly, I avoid supermarkets. I am not materialistic. I teach yoga now, and my students can’t believe I used to smoke and take recreational drugs. Yoga is my community and family; like punk, it’s about expressing yourself from the inside.

‘I remember thinking I was going to marry a mod, have a mod house and mod babies’

Tessa Morton and Charlotte Wager, mods

Charlotte Wager (left) and Tessa Morton at Tessa’s parents’ home in Highgate, London, in March 1981

Tessa We got into a 60s crowd when we were 16 and 17. Then we got into the scooter crowd. We loved that it was edgy; we didn’t want people to see that we were middle class. We wanted to be seen as a bit Quadrophenia, then we’d go home to nice Sunday lunches and warm beds and parents who didn’t quite know what we’d been up to.

We were really into 60s Motown, and boys with scooters were part of that scene. We had to be on the back of their scooters, because the good clubs were dotted all over London. Then Charlotte and I got our own scooters, and it became part of ouridentity. I remember thinking I was going to marry a mod, have a mod house and mod babies.

I’d tell my parents I was staying at Charlotte’s when in fact we were down in Brighton for the weekend. I still remember walking into a club and seeing a roomful of people saying, “Oh, Tessa and Charlotte are here!” We were very visible. I still don’t follow the rules. I don’t have cushions that match my curtains, I don’t follow recipes, and I don’t force my children to go to ballet. I want to be myself, to be authentic.

Charlotte Wager (left) and Tessa Morton at Tessa’s parents’ home in Highgate, London, in January 2014

Charlotte I live in Chicago now, and Tessa is in Warwickshire, but we have stayed close. I remember what it felt like to be a mod: exciting, part of a team; it was something you looked forward to, planned for, dressed up for.

In the 1980s, I became a CND youth leader. I was very into political activism, campaigning and organising marches. There was a bit of tension between that and the mod scene.

I spent the 1990s studying and working, first in London, and then at law school in the US. I was a young professional in Chicago, learning how to be a lawyer, becoming financially successful. I was still young and carefree, but in a different way: I had lots of work responsibility, but no kids.

Somewhere in there came the realisation that I wasn’t going to change the world in quite the way I thought. By 2003, I had four children under six and a busy practice. I was trying to be a successful lawyer and the perfect mother.

Until Trump’s election, I had become politically passive, and shame on me, because that’s what led us to where we are now. Now I am reinvigorated. My husband and I took our two youngest kids to the Women’s March in January.

I suppose my tribe now is Volleyball Mom. It’s my youngest daughter’s sport and I attend two dozen tournaments a year. It’s similar to the mod scene: we used to go on scooter rallies to the Isle of Wight; now I drive to Michigan and Wisconsin for tournaments. It’s a subculture of sorts.

‘We weren’t scared of much. Either the world was less scary, or it was the courage of youth’

Linda Robinson and her sister Susan Stecker

Linda Robinson (left) and Susan Stecker outside Southgate tube station, London, in March 1981

Linda I remember this being taken; we were 15 and 17. I saw it for the first time 35 years later, when it was posted on Facebook. I had to call Susan. We were like, “Oh, God, how awful we look!”

In my teens, I loved having my photograph taken; Southgate station had a photo booth, so we would all crowd in there. I had an Instamatic and was always at Boots, getting pictures developed. If I took a photo I didn’t like, I ripped it up and no one would ever see it. It’s different for my four daughters. I see the stress they go through, looking at images of themselves on social media.

We are Jewish, so that was our scene. In our early teens, we’d hang out at McDonald’s or the Baskin-Robbins in Golders Green, and we would go to pubs – not to drink, but to hang around outside. We’d go to Hampstead and meet at The Milk Churn for a salad or ice-cream and hang out there all night to meet new people. Boys, mainly.

In our 20s, we went to the Camden Palace, where all the New Romantics were. I remember feeling inferior, because they had made such a statement with their clothes and makeup. I remember the skins, the punks, the fights.

I didn’t have any particular statement to make. My dream wasn’t to rebel, but to be financially sound and not reliant on a man. I got a job as a John Lewis fashion buyer at 16 and bought my first flat at 22. I regret not travelling, though.

Linda Robinson (left) and Susan Stecker outside Southgate tube station, London, in April 2017

Susan I was too young to be aware of what a subculture was. We weren’t really part of one, but we wouldn’t have been scared of punks or crossed the street if we saw some. I don’t think we were scared of much, really. Either the world was a less scary place, or it was the courage of youth.

We wore whatever was in fashion. I think the sweatshirt I’m wearing was from Miss Selfridge. On a night out, we would have friends round or go to a friend’s house. There were clubs and events put on especially for the London Jewish teenage scene, and we used to go to those. We weren’t drinking, really, but if we did it would be something like Malibu or Cinzano. We’d arrange to meet at a certain place. It’s bizarre thinking about it now: having no mobiles, you just had to wait for people to arrive.

A lot of the clubs would play disco, but I also liked Spandau Ballet, Adam and the Ants, Heaven 17, David Bowie. I had my own stereo with a cassette and record player, and lots of 12-inch singles. I think music has much less of an influence on fashion now. It’s the age of celebrity.

‘It was about wanting to be different from my parents. By 16, I had a pink mohican’

Helen de Jode and Emma Hall

Helen de Jode (left) and Emma Hall in Wimbledon, London, in August 1980

Emma I was 14 in that picture, the same age as my daughter is now. It is currently half-term, and both she and my 13-year-old son are roaming free in north London, so I suppose their lives are quite similar to mine.

Those tartan trousers were the ones I wore on a CND rally, which culminated in a Killing Joke concert at Trafalgar Square. I wasn’t political at that age; it was more about being part of something. I didn’t have dreams of the future and neither was I trying to escape anything. I think that’s partly because I came from a secure home. I just thought everything would turn out OK. More than anything, it was about wanting to be different from my parents. They were nothing more terrible than middle class and conventional, but the only way to rebel was to look abnormal, so by 16 I had a pink mohican.

As you’re growing up, you are trying on your identity, working it out, trying to find like-minded people. I have a strong sense of myself now, though I think identity is something you search for but never really find.

Helen de Jode (left) and Emma Hall in Finsbury Park, London, in May 2017

Helen It was 1980, and we used to listen to the Stranglers and the Clash. We were very London-based; we didn’t think a great deal about the rest of the world, or listen to music from anywhere else. I think about my children now and can’t imagine them having nearly as much freedom as we had. When we were out, we were completely uncontactable.

There was a group of us who shared similar clothes and went out together, but Emma and I were the only ones at the same school. I remember saying to her once: “I think I have seen you every single day this year.”

At 51, I don’t think of myself as part of a group. The friends I have are friends for their individual personalities, rather than because of something we all have in common.

Everything is so much more global nowadays. My children watch American TV and listen to international music, and there is nothing local that might offer them a sense of identity, except maybe a football club.

My friendship with Emma has evolved throughout our lives. After graduating from uni, I lived and worked in Africa for 10 years; Emma worked in Paris and New York, before settling in London. As young mothers, we lived in neighbouring streets in Highbury; now, I’m living in Sydney. We’re still good friends and see each other a couple of times a year. In many situations, you can present the picture you want others to see, but with someone who has known you since you were 11, you can only be who you truly are.

‘We would sneak off to the airbase to practise our moves on their wooden dancefloor’

Nicole Le Strange, aka Quasi, and Sue Lenham, aka Squasher, rockabillies

Nicole Le Strange (left) and Sue Lenham at the Royalty in Southgate, London, in March 1981

Nicole People called me Quasi because I did a great impersonation of Quasimodo. I was 18. I loved rockabilly music, the clothes, the hairstyles, the dancing, but it was also my refuge. I grew up being told by my mother that I wasn’t good enough because I wasn’t a boy, because I was ugly, because I was too tall and too skinny. Then I met this group, and Sue in particular, and they didn’t want me to change. I felt like a superhero.

I never really liked this picture, but I recently realised it’s not about how I look, it’s about what the photograph means. There I am at such a hard time in my life, but I’m with Sue, who loved me unconditionally – with whom I could be, and still can be, exactly who I want to be.

Even into my early 30s, I remember watching the movie Thelma And Louise and there’s this one line, “You get what you settle for”, and I realised that had been my life. I hadn’t got what I wanted; I had basically done what other people told me I should be doing – including having children, if I’m completely honest. I have three children, and one grandchild. I suddenly realised there was a whole world out there.

In the past 14 years, I have rebuilt my life. For the last five years, my partner and I have lived all over Europe. I’m 54 and feel completely free. At 18, I wasn’t certain what freedom meant.

Nicole Le Strange (left) and Sue Lenham in Kranjska Gora, Slovenia, in April 2017

Sue Nobody else was into rock’n’roll when I was at school: it was too retro. My dad brought us up, which was unusual in the 1960s, and my family situation was challenging. I had to be independent and the scene let me express myself. I found out later that my dad had been an Edwardian, a particular type of teddy boy. It turned out we had frequented the same haunts: unknowingly, I was following in his footsteps. People called me Squasher because my surname sounded like lemon, which became squasher lemon.

Nikki and I would sneak off to Mildenhall airbase to practise our dance moves on their great wooden dancefloor. The men assumed we were gay, because we danced together, which was good, really, because we didn’t want any of them bothering us.

Of course there was gang stuff going on, but I’d do anything not to be in a fight. I remember we snuck in to see Quadrophenia when it opened and we were the only rockers there. We wore jeans and checked shirts, no leathers, but we were terrified we might get done on the way out.

I didn’t get on with my sister and Nikki had family problems, too, so we were both sort-of orphans and became each other’s family. I looked out for her. I knew quite early on that I didn’t want children or a family. Because of my childhood, I had decided to choose my family from my friends. I looked after them and they looked after me, and we still do.

These days, I would say I was a bippy, or a biker-hippy. I go to motorbike rallies twice a year to keep me feeling mad, bad and dangerous to know: we have the hippy mentality, but we’re all bald or short-haired; the average age is between 40 and 60. We bond over our non-conformism. I’ve always been a bit “rage against the machine” in that way.

• These photographs are from Visible Girls: Revisited, an exhibition that opens in Hull on 7 July before a UK-wide tour; go to visiblegirls.com for details.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Interview: Olivia Domingos

Olivia Domingos on combining textiles and simple messages to create an intervention...

Living in a city can be tough – the constant rushing around sometimes tipping into anxiety. What if, whilst you were staring at the back of someone's head on the bus, you were asked 'Are You Okay?'. Would that help? Would it remind you to take a little more time to practice self-care? Jade French caught up with Olivia to explore this and some of her other work too...

Could you introduce yourself and tell us a little about what you do? I’m Olivia Domingos, an artist based in South London. I make illustrations, objects and internet things (with my boyfriend Tom). On the side I sometimes put on art shows / installations and do some photography too.

What’s the ‘Are You Okay’ project, and what do you aim to achieve? Are You Okay? is a social tool to communicate to those who may need a little compassion. I worry a lot about the wellbeing of others but am forever frustrated that I’m not doing enough to help. The idea to place the question on the back of a cap came from walking around London and endlessly looking at the back of someone's head as it’s so busy. I thought it was a really good way to ask a discreet but direct question to a stranger. Unfortunately, not everyone has the benefit of family or friends to check they’re doing okay, or they do but aren’t sharing their problems. And so I want to help those people who aren’t being asked enough if they’re okay. What interests you about mental health issues, and approaching them through art? Each year 1 in 4 people in the UK will experience a mental health problem. That’s a lot of people and there is still stigma around the issue which is incredibly unhelpful for those who might need a bit of help. Approaching the issue through art breaks down a little of the barrier and makes room for humour and empathy, hopefully making it more accessible. This cap is not only for those dealing with mental health issues though, it’s for anyone who is suffering in any capacity whether that’s illness, work related stress, relationship troubles etc. What has the most interesting response been to this project? Right now the project is still in it’s early stages, so I’ve not had a huge response yet. I can only hope that someone has seen a cap being worn and felt a sense of support and understanding. Could you tell us a bit about the ‘Relax Yourself’ project? Relax Yourself is an installation I made recently as part of a show I co-curated in Croydon. It focuses on the absurdity of the celebrity status and the solace we seek in being voyeurs. In Relax Yourself we see Kim Kardashian post sex tape and pre Kanye; trying to establish herself as a global being, the work-out video being a physical representation of the social labour she’s undergoing.