#Elena Manistina

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

1 septembrie 2021, LES NOCES, Stravinsky

Regia multimedia, Carmen Lidia Vidu

În 14 februarie 1926, George Enescu a fost unul dintre cei 4 pianiști care au c��ntat în premieră americană lucrarea „Les Noces” de Igor Stravinski. Era cunoscută admirația lui Enescu pentru compozitorul rus pe care îl considera genial. „Les Noces / Nunta” s-a bucurat de un real succes și a fost interpretată de două ori în seara premierei americane. George Enescu Festival a marcat aniversarea a 140 de ani de la nașterea marelui compozitor român precum și 50 de ani de la moartea compozitorului Igor Stravinski printr-un „dialog” Stravinski-Enescu în care s-au auzit lucrări semnate de aceşti doi muzicieni. Pe 1 septembrie, la Sala Palatului, s-a auzi în premieră „Les Noces” de Stravinski. Concertul a fost susţinut de Orchestra Simfonică a Radiodifuziunii din Berlin condusă de Vladimir Jurowski. Cei patru pianiști au fost Alexandra Silocea - Pianist, Mihai Ritivoiu, Daniel Ciobanu, Andrei Licareț.

RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN VLADIMIR JUROWSKI conductor RALF SOCHACZEWSKY assistent to the chief conductor CHOIR OF THE GEORGE ENESCU PHILHARMONIC IOSIF ION PRUNNER conductor of the choir CARMEN LIDIA VIDU multimedia director

Stravinsky Les Noces (Russian choreographic scenes with singing and music for voices, four pianos and percussion) SOFIA FOMINA soprano ELENA MANISTINA mezzo-soprano ALEXANDER FEDOROV tenor VLADIMIR OGNEV bass DANIEL CIOBANU piano (laureate of the Arthur Rubinstein International Competition) ANDREI LICAREȚ piano MIHAI RITIVOIU piano (laureate of the George Enescu International Competition) ALEXANDRA SILOCEA piano (Bösendorfer Artist)

#CARMEN LIDIA VIDU#les noces#igor stravinsky#Vladimir Jurowski#RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN#RALF SOCHACZEWSKY#CHOIR OF THE GEORGE ENESCU PHILHARMONIC#IOSIF ION PRUNNER#SOFIA FOMINA#ELENA MANISTINA#ALEXANDER FEDOROV#VLADIMIR OGNEV#DANIEL CIOBANU#ANDREI LICAREȚ#MIHAI RITIVOIU#ALEXANDRA SILOCEA#george enescu festival#festivalul george enescu#Scurt Jurnal de Creație la Festivalul George Enescu

1 note

·

View note

Text

La donzella de neu a la ONP Fotografia de Sebastien Mathe_onp

La donzella de neu a la ONP, producció de Dmitri Tcherniakov

La donzella de neu, producció de Dmitri Tcherniakov, fotografia ©-Elisa-Haberer

Un teatre imponent i de primera categoria fa coses imponents i d’excel·lent i primera categoria. L’Opéra National de París ha programat en la temporada 2016/2017 la bellíssima òpera de Nikolai Rimski-Kósakov “La donzella de neu“.

Es tracta de la tercera de les quinze òperes que va composar el compositor rus i segons diuen, l’òpera que més estimava del seu opus, un opus farcit d’obres imprescindibles que ens hem hagut d’acostumar a prescindir-ne degut a la miopia dels programadors que insisteixen en el de sempre amb l’intent de mantenir als de sempre abonats com sempre.

A París han triat un tàndem rus per dirigir una companyia quasi exclusivament russa, garantint d’aquesta manera una idoneïtat idiomàtica i una adequació estilística que si més no atorgui autenticitat. El resultat com no podia ser d’altra manera, és un estímul cultural d’altíssim valor i un orgull per a la institució que la programa i ofereix al seu públic, per l’obra i per la manera de donar-la a conèixer.

Potser a la direcció de Mikhail Tatarnikov no tingui la grandesa que de ben segur li atorgarien Gergiev, Petrenko o Jurowski, però hi ha una bona paleta de colors en la sonoritat que l’exuberant orquestració demana i ell tot i que el discurs es torna feixuc en més d’una ocasió, dóna notorietat als grans i nombroses conjunts amb un Cor en estat de gràcia que enlluerna per la sonoritat i cohesió, en una temporada que la programació l’ha posat al límit, sabent superar tots els reptes amb una nota excel·lent.

L’extens equip vocal està encapçalat per la dolcíssima Snegúrotxka de l’emergent Aida Garifullina en la millor prestació que li he escoltat fins ara. Una veu bonica, gens forçada, d’emissió fàcil i sobretot amb una aura encisadora, té àngel.

El contratenor Yuriy Mynenko és la segona vegada, que jo sàpiga, que assumeix el rol de mezzosoprano en un rol transvestit de l’òpera russa, va ser Ratmir al Ruslanf et Ludmyla a Moscou també sota la direcció de Dmitri Tcherniakov i ara és el desitjat Lel. Canta admirablement i la veu és dolcíssima, però escènicament no és del tot creïble, hi ha una dissonància entre el físic i el cant i la interpretació que costa de superar, però és innegable que l’aposta per a un contratenor (altres vegades ho ha fet un tenor) l’apropa més a la vocalitat original.

Martina Serafin tampoc dóna el físic idoni a la jove Kupava, però vocalment està molt més convincent que en les incursions en els exigents i poc apropiats rols de soprano dramàtica verdiana que han malgastat la seva sumptuosa veu. Aquí està esplendorosa i passional.

Qui havia de ser l’original holandès liceista, el baríton Thomas Johannes Mayer es fa càrrec del rol de Mizguir amb contundència vocal i escènica. mentre que el tenor Maxim Paster tot i complir vocalment amb el rol, no dóna credibilitat escènica al Tsar Berendeï, és clar que la credibilitat escènica en els muntatges de Tcherniakov aviat salta pels aires gràcies a la fascinant i trencadora dramatúrgia.

No m’han convençut gaire La fada primavera d’Elena Manistina i el rei de glaç de Vladimir Ognovenko, ja una mica gastat per esdevenir creïble en un rol que encara ha de mostrar autoritat, té un gran ofici i moltes taules escèniques però la veu mana. Franz Hawlata possiblement tampoc sigui el millor baix per atorga grandesa a Bobyl Bakula.

El conjunt funciona esplèndidament perquè al darrera també hi ha una gran producció escènica amb el segell inconfusible de Dmitri Tcherniakov, que quan es posa a dirigir òperes russes mai defrauda, i si en el Kitej ens va enlluernar, com també ho va fer en els muntatges de La núvia del Tsar a Berlín, El príncep Igor a Àmsterdam i el MET, Ruslan i Ludmila a Moscou crea una fascinació dramàtica i escènica absolutament genial, molt lluny de les fallides aproximacions verdianes.

Dmitri Tcherniakov recrea un món possible, molt contemporani de la Rùssia actual i que per tant segurament un rus identificaria molt millor que nosaltres, per a un conte inicialment fantàstic i d’arrels molt populars. Hi ha una barreja de vestuari que ja no ens hauria de sorprendre, i sobretot hi ha una escenografia imponent per recrear aquesta comunitat neo-rural on el conte de Snegúrotxka intenta, no sempre de manera convincent però finalment poc discutible gràcies a un quart acte d’absolut somni, màgic i altament poètic, convencer de les bondats d’aquesta història que enfronta a déus, semi-déus i humans, de manera ben diferent però altament influenciada per el món wagnerià.

En el pròleg assistim a un classe de dansa a una escola, on la mare de Snegúrotxka no és la fada primavera sinó una professora de ballet, mentre que en els quatre actes successius l’acció transcorre en un frondós bosc, de impactant realisme quan convé.

SINOPSI

Filla del rei Glaç i de la fada Primavera, Snegúrotxka, la donzella de neu, té el cor de neu, que el sol no pot fondre-li. Un dia, des del fons del bosc on viu, sent els cants de Lel, el pastor. Encisada per aquella veu i pel que canta, Snegúrotxka demana als seus pares anar a viure entre els homes. Un cop allà, l’adopten una parella de pagesos i la noia comença a viure com ells. En una ocasió en què escoltava les cançons de Lel, el pastor li demana un petó en paga, però ella li dóna només una flor. Aleshores Lel fuig amb tot d’altres noies que el reclamen. Snegúrotxka és consolada per Kupava, la noia que està a punt de casar-se amb el pastor Mizguir. Però quan apareix aquest darrer, resulta que s’enamora perdudament de Snegúrotxka.

Llavors l’abandonada Kupava recorre a la justícia del bon tsar Berendei, que és festejat pels seus músics i cortesans (que es queixen del fred que no s’atura). El tsar ordena la preparació d’una gran cerimònia nupcial i ofereix un premi a qui sigui capaç d’enamorar Snegúrotxka, sabedor que el fred no cessarà fins que el cor de neu de la noia s’arribi a fondre. Durant la festa, Lel torna a cantar i en acabat li és concedit com a premi un petó de la noia que ell esculli. Però Lel tria Kupava, contra les esperances de Snegúrotxka.

Aleshores, la noia de neu reclama l’ajuda de la seva mare, que finalment li concedeix el do d’estimar qui l’estimi. Snegúrotxka dóna el seu amor a Mizguir, però això no fa sinó que la noia acabi fonent-se finalment, escalfada pel sol de l’amor. Mentre Mizguir es llança al riu, desesperat, el tsar i tota la seva cort celebren amb una gran festa la tornada del sol

Nikolái Rimski-Kórsakov Снегурочка–Весенняя сказка o Snegúrochka–Vesénnyaya Skazka LA DONZELLA DE NEU (1873) Òpera en un pròleg i 4 actes amb llibret del compositor basat en l’obra d’Aleksandr Ostrovski

Snegourotchka (La donzella de neu), Aida Garifullina Lel, Yuriy Mynenko Kupava, Martina Serafin El Tsar Berendeï, Maxim Paster Mizguir, Thomas Johannes Mayer La fada primavera, Elena Manistina El rei de glaç, Vladimir Ognovenko Bermiata, Franz Hawlata Bobyl Bakula, Vasily Gorshkov Bobylicka, Carole Wilson L’Esperit dels boscos, Vasily Efimov Primer herald, Vincent Morell Segon herald, Pierpaolo Palloni Un patge, Olga Oussova

Orchestre et Choeurs de l’Opéra national de Paris La Maîtrise des Hauts-de-Seine Director del cor: José Luis Basso Director musical: Mikhail Tatarnikov

Director d’escena: Dmitri Tcherniakov Escenografia, Dmitri Tcherniako Disseny de vestuari, Elena Zaitseva Disseny de llums, Gleb Filshtinsky Vídeo, Tieni Burkhalter

La Bastille, París 25 d’abril de 2017

Aquest streaming que ens va proposar el Canal Arte és una de les coses més belles, estimulants i gratificants de la temporada i no cal dir que després del que us vaig explicar ahir aquí, encara més. Els incondicionals del Kitej per suposat, però tota la resta també, no us ho podeu perdre.

ONP 2016/2017: LA DONZELLA DE NEU DE RIMSKY-KÓRSAKOV (Garifullina-Serafin-Manistina-Paster-Mayer-Mynenko;Tcherniakov-Tatarnikov) Un teatre imponent i de primera categoria fa coses imponents i d'excel·lent i primera categoria. L'Opéra National de París…

#Aida Garifullina#Carole Wilson#Choeur et Orchestre de l&039;Opèra national de Paris#Dmitri Tcherniakov#Elena Manistina#Franz Hawlata#La donzella de neu#Martina Serafin#Maxim Paster#Mikhail Tatarinkov#Nicolai Rimski-Korsakov#Olga Oussova#Opera National Paris La Bastille#Pierpaolo Palloni#Snegourotchka#Thomas Johannes Mayer#Vasily Efimov#Vasily Gorshkov#Vincent Morell#Vladimir Ognovenko#Yuriy Mynenko

0 notes

Video

youtube

TEASER “LES NOCES” / STRAVINSKY

ORCHESTRA SIMFONICĂ A RADIODIFUZIUNII DIN BERLIN

VLADIMIR JUROWSKI

CARMEN LIDIA VIDU regizor multimedia

SOFIA FOMINA soprană

ELENA MANISTINA mezzosoprană

ALEXANDER FEDOROV tenor

VLADIMIR OGNEV bas

DANIEL CIOBANU pian (laureat al Concursului Internațional Arthur Rubinstein) ANDREI LICAREȚ pian

ALEXANDRA SILOCEA pian

MIHAI RITIVOIU*pian (laureat al Concursului Internațional George Enescu)

0 notes

Text

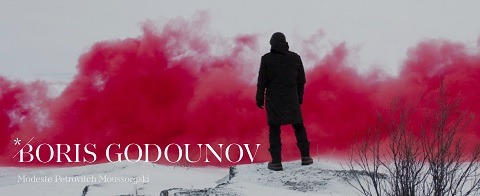

Lope Hernan Chacón: Mussorgsky – Boris Godunov (Paris, 2018)

Modest Mussorgsky – Boris Godunov L’Opéra national de Paris, 2018

Vladimir Jurowski, Ivo van Hove, Ildar Abdrazakov, Evdokia Malevskaya, Ruzan Mantashyan, Alexandra Durseneva, Maxim Paster, Boris Pinkhasovich, Ain Anger, Dmitry Golovnin, Evgeny Nikitin, Peter Bronder, Elena Manistina, Vasily Efimov, Mikhail Timoshenko, Maxim Mikhailov, Luca Sannai

Culturebox – 7 June 2018

There’s a sense of the epic in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov that is entirely in keeping with the importance of the period in Russian history and with the nature of the Russian characteristics displayed in it. What is also essential about Mussorgsky’s epic vision for the work is its ability not just to capture a sense intimacy and personal conflict within that historical drama – a common enough characteristic in opera – but how he is able to make those personal sentiments just as grand and epic without losing their human character. Mussorgsky takes human sentiments of sadness, regret, guilt and internal conflict and gives them a Macbeth-like Shakespearean depth and complexity on a scale that befits their importance.

You get a sense of that right from the start in the opera, with the people of Russia calling out in chorus for him to be their new ruler. You also get a sense of how Boris feels about this from his very first line – “My soul grieves”. He has a heavy duty to perform to live up to the expectations of the Russian people and do them justice, but there is also a sense of guilt and remorse for the manner in which he comes to power, with rumours already accusing him of murdering the young Tsarevitch Dmitriy from the line of Ivan the Terrible to ascend to the throne. An accumulation of misfortune and other forces, including the rise of a Pretender to the throne in Lithuania, turns the people against Godunov, and the combined results strike the Tsar in deeply troubling ways. Finding a balance of scale between epic and intimate is one matter, but there is also the consideration of which version of Boris Godunov is the most authentic and effective in achieving the necessary impact. Historically it’s been the revised 1872 version that has been most commonly used, and understandably so as it contains many extensions to Mussorgsky’s brilliant score, but Rimsky-Korsakov’s reworking of the original materials has also been popular. Gradually however, we are seeing more productions of the original 1869 version, commonly with a few additions from the revised 1872 version that are deemed too good to be left out.

The 2018 Paris production however, directed by Ivo van Hove and conducted by Vladimir Jurowski, takes very much a purist approach by sticking to the complete 1869 original version of Boris Godunov, with no Polish Act nor any of the 1872 additions. It’s purist at least in musical terms, but clearly with the controversial Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove involved in the project, it’s going to be anything but purist as far as the staging goes. That presents an intriguing team that should find a good balance between the grandly epic and the deeper underlying personal sentiments, and in many respects both sides of the work are well represented, but the production seems to be more effective for the choice of the stripped down force of the 1869 version than for anything that Jurowski or van Hove bring to the work.

As is usually the case with this director, Ivo van Hove relies on a minimal staging, abstract-modern with no period or historical trappings. The use of the space, opened up with back projections of the Russian people and landscapes that are mirrored to the sides, permits a sense of epic scale that can also close the work down to a more intimate level of intensity. A staircase is often present, leading up and also leading down beneath the stage, the symbolism of which is clearly apparent, representing rise and fall, and the separation of the ruling classes from the people. Other scenes are effectively austere, such as between Pimen and Grigoriy in the cell of the monastery in Chudov, needing no further elaboration than two people in near-darkness recounting events in words and divulging the thoughts that run through their minds.

How much of the success in getting this across is down to effective direction, how much is down to the musical performance and how much of this is simply down to the power of the story and Mussorgsky’s scoring of it is debatable, but it seems to me that it’s Mussorgsky’s score that does the bulk of the work. Even then Jurowski‘s conducting seems rather restrained and unfocussed, although it’s hard to judge fairly from an internet stream (I’ll be listening again more closely to the live radio broadcast on France Musique this weekend), and yet there’s no question that the drama and the dynamic is all there. Likewise Ivo van Hove doesn’t seem to bring much to an interpretation of the drama, but it doesn’t get in the way of it either.

There are a few stylistic touches applied, but perhaps the only significant twist is at the conclusion. Not only does Boris Godunov finally and dramatically succumb to the pressures of family problems, famine blighting the country and growing instability in his mind over his murder of Dmitriy, but his son dies too at the hand of the Pretender Grigoriy. It’s a dark dramatic moment that doubles down on the music that Mussorgsky provides for this finale and, as Boris’s son’s reign was indeed cut short in deference to the False Dmitriy, it even effectively conveys the suggestion in Mussorgsky’s music that the conflict and turmoil of this historical period is far from over.

Ideally you want a Russian cast in Boris Godunov for maximum effectiveness, at least in the principal roles, and there’s little to find fault with in team assembled for the Paris production. Ildar Abdrazakov is perhaps a little too smooth and lacking the necessary depth and edge to get across the full conflict of Boris Godunov. He sings the role well, but there’s not enough emotion in the voice and too much overplaying in the acting to try to compensate for it. Ain Anger is an appropriately grave austere and occasionally ominous Pimen, there’s a similar good balance of restraint and gravity in Maxim Paster‘s Shuysky, and Vasily Efimov brings vocal colour and some hard truths as the Holy Fool. Lots to enjoy in the singing performances then, with strong a strong chorus combining to make a convincing case for the original 1869 version of Boris Godunov becoming the canonical version of this great work.

Links: L’Opéra de Paris, Culturebox

View Source

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2KnI3Yc via Ver Fuente

0 notes

Video

youtube

Stravinsky, LES NOCES (scene coregrafice pentru cor, soliști, 4 piane și percuție)

CARMEN LIDIA VIDU, regie multimedia

VLADIMIR JUROWSKI dirijor

SOFIA FOMINA soprană ELENA MANISTINA mezzosoprană ALEXANDER FEDOROV tenor VLADIMIR OGNEV bas DANIEL CIOBANU pian (laureat al Concursului Internațional Arthur Rubinstein) ANDREI LICAREȚ pian MIHAI RITIVOIU pian (laureat al Concursului Internațional George Enescu) ALEXANDRA SILOCEA pian (Bösendorfer Artist)

#CARMEN LIDIA VIDU#Les Noces#Vladimir Jurowski#George Enescu#george enescu festival#festivalul george enescu#Scurt Jurnal de Creație la Festivalul George Enescu

0 notes