#Earl Dixon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bad movie I have Nothing but Trouble 1991

#Nothing but Trouble#Chevy Chase#Dan Aykroyd#John Candy#Demi Moore#Valri Bromfield#Taylor Negron#Bertila Damas#Raymond J. Barry#Brian Doyle-Murray#John Wesley#Peter Aykroyd#Daniel Baldwin#James Staszkiel#Deborah Lee Johnson#Karla Tamburrelli#John Daveikis#Earl Dixon#Danielle Aykroyd#P.H. Aykroyd#Richard Kruk#Robert K. Weiss#Laurence Bilzerian#Isaac Tigrett#Catherine Quinn#Ron Ulstad#Paul LeClair#Stan Garner#James Frank Clark#Jeffrey P. Baggett

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Norman and toy props🧸

#death stranding#lou#death stranding 2#tarcat#the walking dead#dog#props#behind the scenes#crew#norman reedus#hideo kojima#tommie earl jenkins#melissa mcbride#carol peletier#daryl dixon#sam porter bridges

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

my virtual hear me out cake

˚₊‧꒰ა ☆ ໒꒱ ‧₊˚

(since i have like no friends to do this w irl)

i’ve seen a few people post these, i’d love to see more<33

#dean winchester#jensen fucking ackles#earl hickey#norman fucking reedus#daryl dixon#prismo the wishmaster#jade herrera#boone twisters#eddie brock#nick wilde#hear me out#hear me out cake

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.I. Joe the Movie was released on August 14, 1987. It was meant to be a theatrical release, see the death of Duke (Michael Bell), and have a topless scene with Zarana (Lisa Raggio). The production went longer than predicted so the Transformers movie was released first, which ended up having a huge impact on the Joe movie. Because Transformers the Movie underperformed in the theaters, it was decided to release the Joe movie as a direct to video and TV presentation. Because the Transformers movie recieved so much backlash from killing Optimus Prime (Peter Cullen), dialogue was added explaining Duke didn't die but went into a coma. The topless scene was story boarded but the scene was altered in the final film with a swim top. Most of the new characters introduced were the new recruits (Lt Falcon - Don Johnson, Kunoichi Jinx - Shuko Akune, Chuckles, Law - Ron Ortiz and Order, Big Lob - Brad Sanders, and Tunnel Rat - Laurie Faso), Sgt Slaughter's (Robert Remus), Renegades (Mercer - Kristoffer Tabori, Red Dog - Poncie Ponce, and Taurus - Earn Boen) and the mutants from Cobra-La (Pythona - Jennifer Darling, Golobulus - Burgess Meredith, and Nemesis Enforcer - Cullen). As Cobra Commander (Christopher Collins/Chris Latta) was facing a mutiny by Dr Mindbender(Brian Cummings), Baroness (Morgan Lofting), Destro (Arthur Burghardt), Zartan (Zack Hoffman), Tomax (Corey Burton) and Xamot (Bell), Pythona arrived and convinced Cobra to steal the BET device. The mission failed, Serpentor was captured, and Cobra Commander retreated his forces to Cobra-La. There Golobulus revealed that Cobra Commander was an escapee from Cobra-La. Also that Cobra-La had secretly manipulated Dr Mindbender into creating Serpentor (Dick Gautier). While Lt Falcon was court martialed by the Joes, Cobra Commander was put on trial in Cobra-La. The movie also featured the familiar Joes and Cobras Low Light (Charlie Adler), Wet Suit (Jack Angel), Blow Torch, Lift-Ticket (both Bell), Motorviper (Gregg Berger), Iceberg (Burghardt), Beach Head (William Callaway), Quick Kick (Francois Chau), Zandar (Cullen), Dial-Tone (Hank Garrett), Hawk (Ed Gilbert), Slip Stream (Dan Gilvezan), Roadblock (Kene Holiday), Bazooka (John Hostetter), Doc (Buster Jones), Gung Ho, Ripper, Televiper (all Latta), Lady J ( Mary McDonald-Lewis), Letherneck (Chuck McCann), Cross-Country (Michael McConnohie), Snow Job (Rob Paulsen), Mainframe (Patrick Pinney), Flint (Bill Ratney), Buzzer, Shipwreck, Monkeywrench, Hector Remirez (all Neil Ross), Thrasher (Ted Schwartz), Scarlett (B.J. Ward), Alpine (Lee Weaver), Torch, Wild Bill (both Frank Welker), Lifeline (Stan Wojno), and Jackson Beck as the narrator. ("G.I. Joe the Movie", Movie, Event)

#august#1987#nerds yearbook#real life event#first appearance#animation#cartoon#g.i. joe#gi joe#ron friedman#buzz dixon#don jurwich#cobra la#charlie adler#low light#jinx#shuko akune#wet suit#jack angel#michael bell#duke#blowtorch#lift ticket#xamot#motorviper#gregg berger#earl boen#taurus#arthur burghardt#destro

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

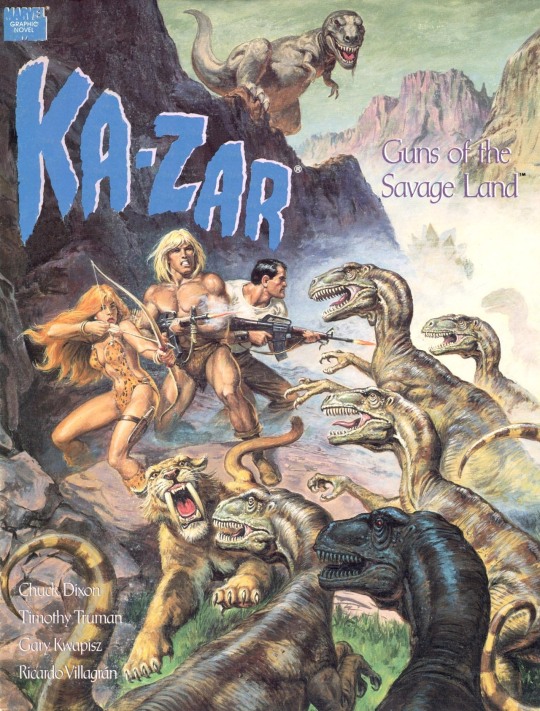

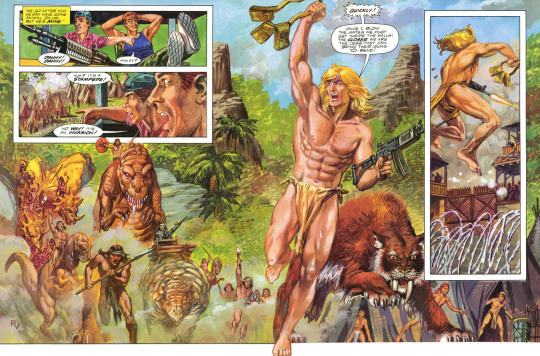

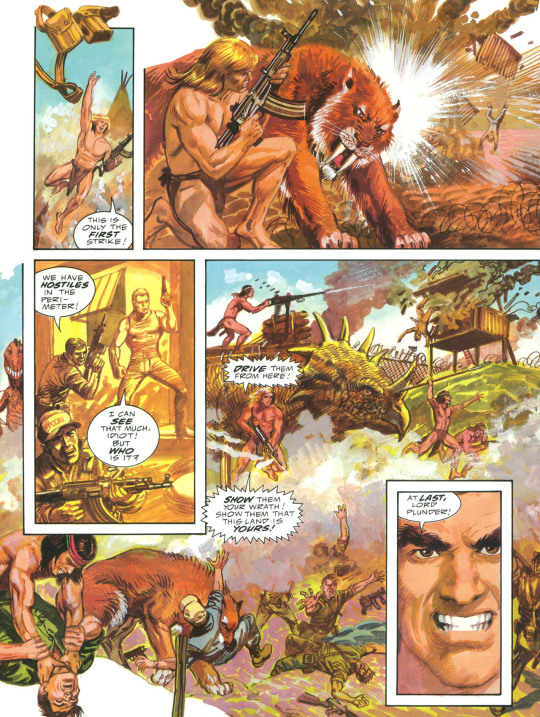

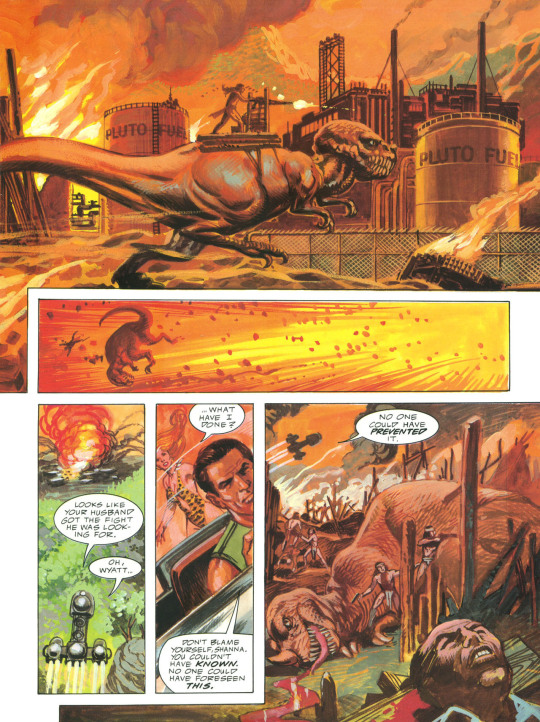

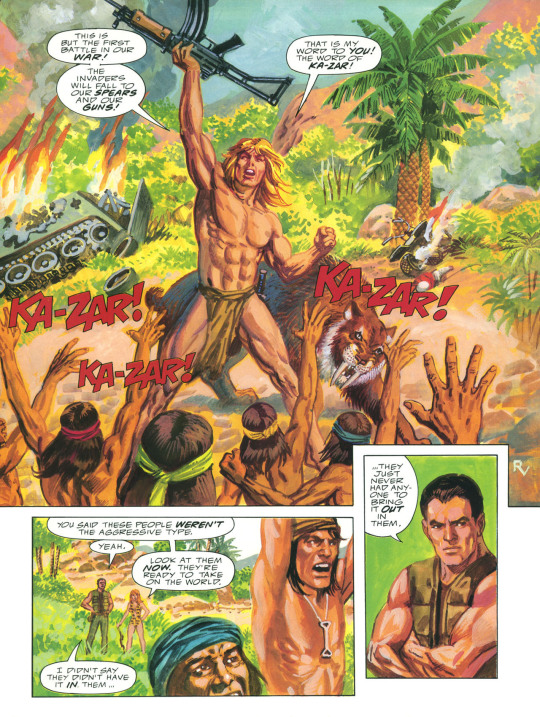

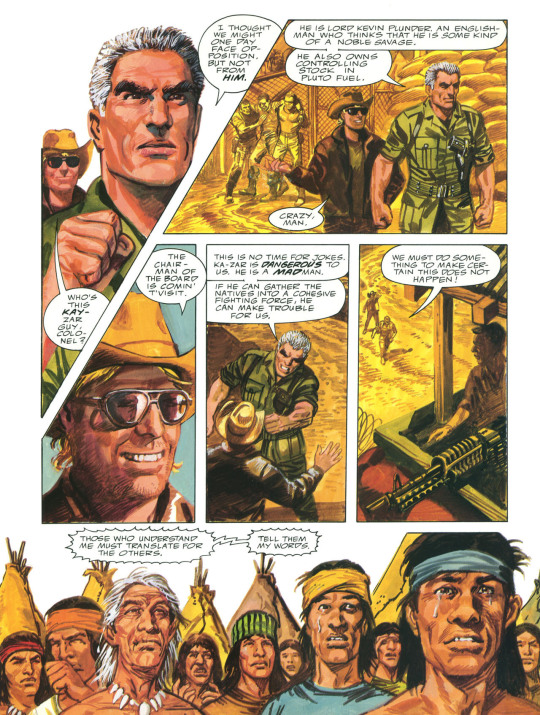

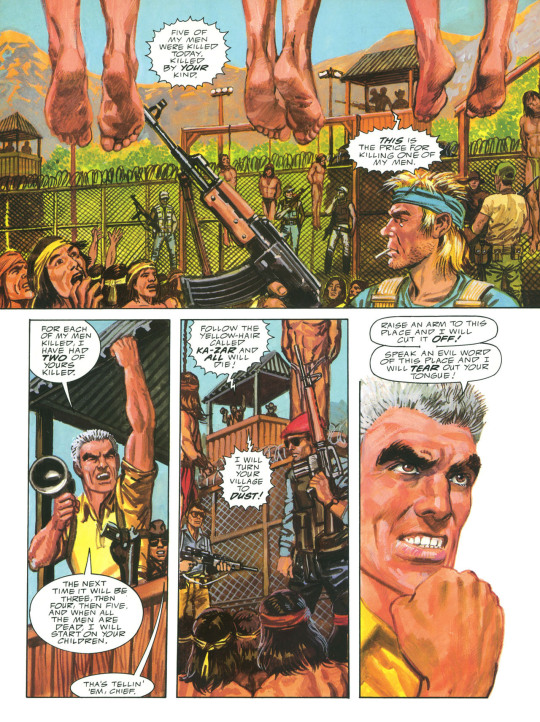

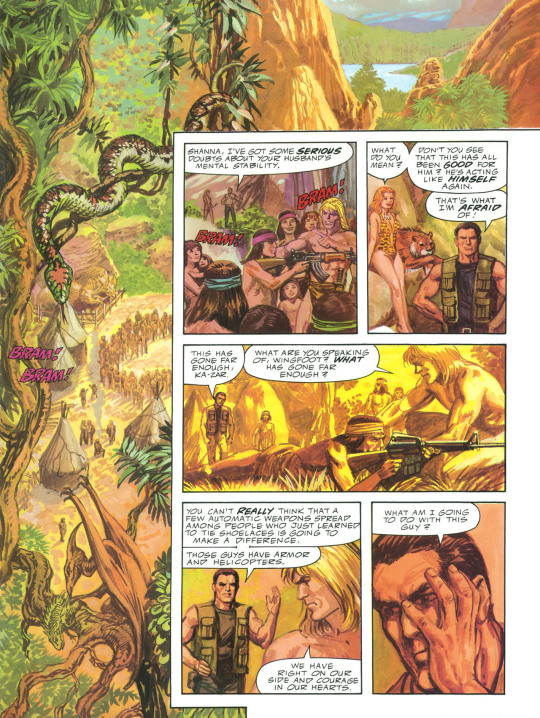

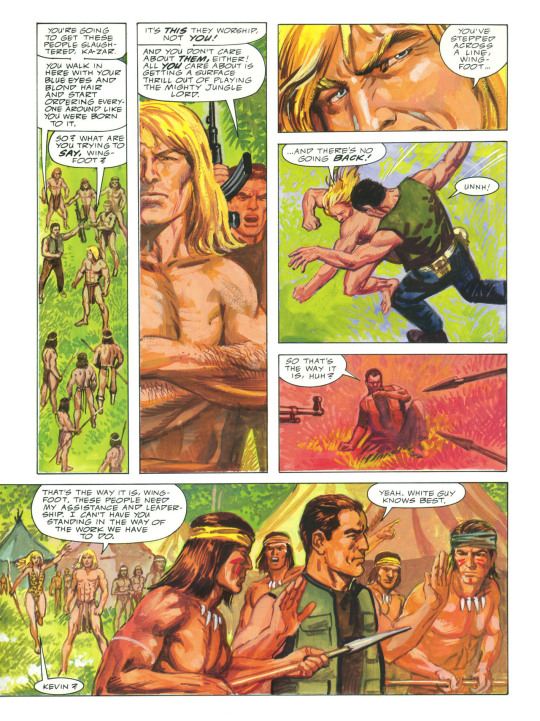

Marvel Graphic Novel 62 (1990) Ka-Zar: Guns of the Savage Land by Chuck Dixon, Timothy Truman and Gary Kwapisz

Cover: Earl Norem

#Marvel Graphic Novel#Ka Zar#Shanna the She Devil#Zabu#Wyatt Wingfoot#Chuck Dixon#Timothy Truman#Gary Kwapisz#Earl Norem

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alden: Earl and I want to build wall catapults for our protection against the Whisperers.

Yumiko: Yeah, no.

Later ...

Earl: Screw that. I'm Earl Sutton, blacksmith that keeps Hilltop running and Imma build me some mothereffin' catapults.

Also Earl: And Imma make Daryl a morningstar weapon. Just because.

#the walking dead#twd s10#twd#earl sutton#alden twd#alden sutton#adam sutton#daryl dixon#the whisperers

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earl Gardner, last to hang in Arizona.

Arizona, long a part of the old and wild West, has a somewhat chequered history for both law-breaking and law-enforcement. Home to Tombstone, the OK Corral, Bisbee, Prescott and a few other Wild West landmarks, it immeditely conjures images of rattlesnakes, arid deserts, epic shoot-outs and outlaws twisting at the end of a rope. Earl Gardner was no Old West outlaw, but he was the last oportunity…

View On WordPress

#Ambrose Yesterday#Apache#Arizona#Bisbee#capital punishment#Coolidge Dam#crime and punishment#death penalty#Earl Gardner#Florence#gallows#George Dixon#George W.P. Hunt#Gila County#History#murder#Native American#OK Corall#Prescott#San Carlos Reservation#Tombstone#true crime#Walapai#Wild West

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SCOTT DIXON 2023 24 Hours of Le Mans Paul Foster Photography

#scott dixon#24h le mans 2023#wec#indycar#hi earl#my luck is about as good as his this weekend but we stay silly :3

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I ordered five packs of the Ganassi collector cards aaaaand

#indycar#alex palou#scott dixon#kyffin simpson#linus lundqvist#marcus armstrong#renger van der zande#alex lynn#earl bamber#dario franchitti#alex zanardi#jimmy vasser#collector cards#that’s 22 out of 36 cards#the temptation to buy more

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

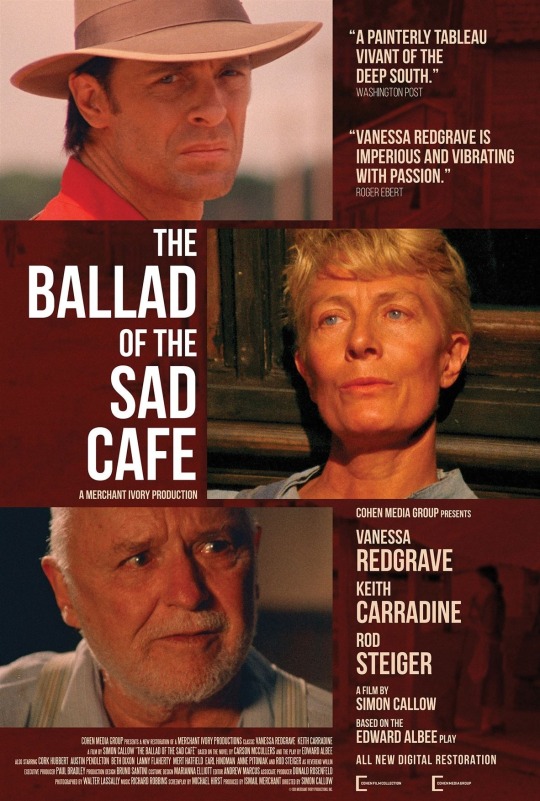

#the ballad of the sad café#vanessa redgrave#keith carradine#rod steiger#cork hubbert#austin pendleton#beth dixon#lanny flaherty#mert hatfield#earl hindman#anne pitoniak#simon callow#1991

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Guitarist, singer and songwriter Lacy Gibson (1936-2011) may not have been too well known among fans, although I'm sure many of you have heard him, without remembering he was there, on the Son Seals Live and Burning album. He also played and/or recorded with Jimmy Reed, Earl Hooker, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Willie Dixon, Otis Rush, Willie Mabon, and even accompanied jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie. He was a versatile, flamboyant guitarist with a passionate voice. Just listen to "Easy Woman" from the album Switchy Titchy.

***

Quizás el guitarrista, cantante y compositor Lacy Gibson (1936-2011) no haya sido demasiado conocido entre los aficionados/as aunque seguro que muchos/as lo habéis escuchado, sin recordar que estaba, en el disco de Son Seals Live and Burning. Además tocó y/o grabó con Jimmy Reed, Earl Hooker, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Willie Dixon, Otis Rush, Willie Mabon, e incluso acompañó a músicos de jazz de la talla de Duke Ellington o Count Basie . Era un guitarrista versátil, llamativo y con una voz apasionada. No hay más que escuchar "Easy Woman" recogida en el disco Switchy Titchy.

(Fuente: Eugenio. latabernadelblues,com)

desde: pasión por el jazz y blues

#Youtube#blues#guitar#jimmy reed#earl hooker#junior wells#duke ellington#count basie#buddy guy#willie dixon#otis rush#willie mabon

1 note

·

View note

Text

Words: 5,818

Pairing: Daryl Dixon x Reader

Reader pronouns: she/her

Era: the Whisperers

Warnings: language (lots of swearing always haha), typical TWD violence

Summary: Daryl finds himself in a tight spot in the woods when walkers are suddenly behaving in ways they shouldn't.

A/N: This is the first part of a news series! Thanks for joining me on another new adventure.

“How was it?” Carol asked, catching sight of Daryl as he came in.

The archer shrugged. “Got somethin’. Deer. Ain’t much. Was pretty scrawny, but better than nothin’. Dropped it off at the pantry,” he drawled. He hesitated and she saw it immediately.

“What is it?” she asked, her brow furrowing.

Daryl shook his head and shrugged again. “I dunno. S’weird. I felt like somethin’ was watchin’ me out there some of the time.”

She leaned heavily on the counter, a tight frown growing on her face. “Something?”

“Or someone maybe,” Daryl said with a shrug.

The worry lines on her forehead deepened. “Well, did you see any sign of anybody out there? How close were you to here, to Hilltop?”

Daryl hauled his crossbow off his shoulder and shrugged. “I didn’t see shit. And I was a ways off but not far enough. Close enough that if somebody is out there, they’d probably stumble their way here eventually. Made sure nobody could follow me back but—” He chewed on his bottom lip anxiously. “I dunno.”

Carol looked worried and her eyes drifted to Henry where he stood with Alden and Earl, already starting his blacksmith training.

Daryl reflexively reached for his knife in its sheath, meaning to check the sharpness of the blade. He swore when his hand grasped at air. “Fuck!” he growled.

“What is it?” Carol asked.

Daryl sighed and rubbed a hand over his face, annoyed. “I must have left my knife out there… Prob’ly set it down after I gutted the damn deer. There were walkers comin’ and I was in a hurry.” He sighed heavily again. “Shit. I’ll go back for it tomorrow. See what else I can see out there. I can’t shake the damn feeling somethin’ was out there.”

Carol nodded, her brow still furrowed.

“Ya heard anything from Michonne? How’re the kids?” Daryl asked.

Carol’s expression dropped. “Haven’t heard. We’re still… not talking. She’s keeping Alexandria closed off.”

“Mmm,” Daryl hums, swinging his crossbow back up on his shoulder. He was about to go on, but Tara, Jesus, and Aaron come running up. They exchange greetings and hugs before Daryl excuses himself to find some place to crash with Dog for the night.

Carol puts her arm around Henry’s shoulder as they watch him wander toward the barn. “I guess he’s not so bad,” Henry comments. “Henry!” Carol scolds him, but she can’t help laughing a little herself.

_ _ _ _ _ _

The next morning Daryl woke early like usual, plagued by the same old restlessness that never seemed to have a cause or a cure. He wanted his damn knife back, and that nagging feeling was still bothering him, like a tickle at the back of his brain, some itch he couldn’t reach to scratch. That feeling he had been watched the day before. He assembled his gear, grabbed a spare knife, and set off beyond the walls of Hilltop and back into the woods, retracing his route from the day before.

It was easy to retrace his steps. Even if he hadn’t known the woods like the back of his hand by then after his six years of wandering, the circle of vultures and noisy cawing of ravens squabbling over the gut scraps of the carcass drew him. He prepared himself in case there were walkers feeding too. He found the gut pile easily and started to search the ground nearby for his knife. He felt through the leaf litter and kicked over sticks and through nearby bramble but his search was initially fruitless. Did the damn thing sprout legs? What the hell… It wasn’t until he stood up in frustration and really scanned his surroundings that the glint of something silver caught his eye.

Daryl’s eyes narrowed as they landed on the metallic object. The hair on the back of his neck prickled and stood on end. He found himself carefully surveying the entirety of his surroundings again, straining his hearing for any sound of movement, squinting into the shadows cast by the large trees overhead. He cautiously approached the nearby tree trunk, watching where he placed his feet, waiting for someone to pounce like this was a trap and he was the mouse going for the cheese.

His knife was hanging from an arrow shot into the trunk of a huge oak, dangling from a leather strap. Daryl carefully slid it off and inspected it. It looked just as it had the day before, except for the addition of the makeshift loop in order to hang it from the arrow. Oh—and it had been sharpened? The blade was honed to perfection. And the arrow was something else… He grabbed and pulled on the shaft, but the head broke off and remained buried deeply in the tree. He could tell, however, that it had been handmade. The fletching was of stiff, black, glossy feathers with a slightly iridescent sheen. He spun the shaft between his fingers and watched the way the light shone on them, shifting from plum to emerald to shining sapphire blue and then back to deep night. He glanced over his shoulder, frozen, listening.

He didn’t know what the fuck was going on, but he knew one thing for certain now; he wasn’t imagining that feeling of being watched. But who was watching and why would they bother to hang a found knife in case its owner returned? Most people would have considered it a good find and kept it for themselves. He maintained it religiously as a rule. It was in perfect condition. Not that he was complaining… but it seemed fucking peculiar.

As he turned toward home, a raven let out a series of raspy croaks overhead and took flight. The wood was so quiet that Daryl could hear the wind through its wings as it flapped past and wheeled upwards, disappearing into the canopy of the craggy trees.

Daryl began to slowly search the area for any sign of someone, but was surprised and even more perplexed when he couldn’t seem to find a leaf or twig out of place. Not even a damn partial footprint… an impression in the ground. Nothing. The archer scoured the area thoroughly for the next couple hours, knife back in its sheath and the mysterious arrow shaft with its inky black fletching clutched in his right hand. He kept his eyes open for game, but it seemed to be making itself as scarce as clues were. There were seemingly endless game trails, old and new, and he walked them as systematically as he could. It was the easiest way to get around. Step off to either side and the blackberry brambles and vines would tear at your clothes and skin, biting in and drawing blood. That alone should have made it easier to figure out if someone was lurking around, but he found neither track nor trace… With the day wearing on and no sign of anything else out of the ordinary, Daryl conceded and decided to head back to Hilltop. At least he had his knife...

It was nearly dark by the time Daryl could see the walls of Hilltop ahead. Carol happened to be up on the guard platform when he returned, though Henry was absent. “Find anything?” she asked, surveying his expression as he came inside and the walls closed behind him. He was as stoic as always.

His hand went to the handle of his knife, replaced in its sheath. “Yes and no,” he drawled. Furrows appeared in Carol’s forehead. “Found my knife. But it was hangin’ up on this,” he said, holding up the arrow he still had clutched in his hand. “Stuck into a goddamn tree like somebody was waitin’ for me to come back for it.”

“That’s strange,” Carol murmured. She took the shaft and examined it, running a finger along the glossy black feathers at the end. Her eyes met Daryl’s, sharp and wary. Her expression was questioning. Daryl shrugged and shook his head. “I ain’t got a clue. I spent the whole day over there, crisscrossing the trails lookin’ for some sign of who was out there and all I was left with was this damn arrow. Not a boot print, not a broken twig, fuckin’ nothin’. ‘S’like it was left by a damn ghost.”

“Why would someone would pin it up for you to find again? Why wouldn’t they just keep it?” she questioned him, handing the arrow shaft back. Daryl shrugged.

“Dunno…” he murmured, twirling it in his hands. He looked around at the afternoon shadows crawling slowly over Hilltop and sighed. “How’re things? Henry?” he drawled, patting Dog’s head absently.

“He’s… doing okay,” she said, smiling. “I think it’s going to take him a little time to find his place here. But Alden and Earl have gotten him started.”

Daryl nodded. “Can’t be easy tryin’ to figure out bein’ ‘round other kids his age for the first time,” Daryl commented.

“No,” Carol said. “But I’m sure he’ll figure it out,” she added with a tight smile.

Daryl looked up as Jesus, Aaron, and Tara were suddenly making their way down the hill toward him and Carol with grim expressions.

“S’matter?” Daryl drawled, fiddling with his bandana absently as they came to a stop in front of him.

“Early this morning, Aaron and I found Rosita collapsed and exhausted out in the woods. She fired a flare. She and Eugene were working on something when walkers came up on them. Eugene’s hurt. She said she left him in a barn and was trying to get here for help. She’s in the infirmary,” Jesus explained.

“Eugene is still out there,” Aaron said, looking at Daryl. “We could really use your tracking skills. I don’t want to risk him spending another night out there.”

Daryl nodded. “Yeah. ‘Course.” And the three of them, Daryl, Aaron, and Jesus (and Dog) prepared to head out and search for Eugene.

They headed back toward where Aaron and Jesus had found Rosita and Daryl realized it wasn’t far from where he’d shot the deer and forgotten his knife. He pondered this, but didn’t say anything to Jesus or Aaron. He did, however, continue scrutinizing the ground closely for any sign or Eugene or anyone else.

They came to the edge of a large field and Daryl stopped dead. “What the hell?” he drawled. Aaron and Jesus stopped beside him, squinting at a herd in the field moving in concentric circles.

“Have—have either of you ever seen walkers do that before?” Jesus asked. Both Aaron and Daryl shook their heads.

“Never,” Daryl said, his gaze sharp as he studied the swirling horde. “C’mon. We ain’t got long before dark.” He led the way again with Dog out slightly in front. Moving through the woods as silently as possible, Daryl knew they were now very close to where he’d shot the deer. The hair on the back of his neck prickled again and he stopped as a gust of wind suddenly kicked up at their backs. “Stop,” he said suddenly, throwing up a hand. Jesus and Aaron stood still. “I can hear ‘em,” Daryl drawled. “On the wind.”

Straining their hearing, Jesus and Aaron heard the growls on the wind now too. “They’re following,” Aaron said, glancing back. Through the trees, wandering shapes could barely be seen. “Did they see us?” he asked.

Jesus stared at the incoming herd, suspicious and at a loss. “I don’t know. But we better keep moving.” Night had fallen by the time Daryl was able to trace Rosita’s trail back to the barn. They found Eugene huddled in the cellar. He was nearly incoherent, shaking and sweaty. “C’mon. We gotta go, Eugene,” Daryl insisted.

“Are you okay?” Aaron asked concernedly as soon as they had hauled him up from the hidden cellar.

“I took a bad step and dislocated my knee,” Eugene said, still shaking.

“Well, if it’s dislocated we can just pop it back in,” Daryl said, his brow furrowed.

“No. No, listen to me,” he argues, wiping sweat from his brow. “The herd that followed us here is on its way back.”

“I saw their tracks,” Daryl drawled, not understanding his frantic tone and his trembling. “They’re gone…”

“No. It’s not. It’s already been through here twice. It’s lookin’ for me,” he insisted. “Eugene—” Jesus started. “No! We have to get out of here before it comes back! This wasn’t a normal run-of-the-mill bunch of wandering dead,” he says in his Texas twang.

“What do you mean?” Aaron asked, wide-eyed and unsettled by Eugene’s behavior.

He lowered his voice. “When they passed us by, we could hear them—they were whispering to each other.”

Everyone exchanged confused and stunned glances. “You mean they were—talking?” Aaron asked.

Eugene was almost crying he was so frantic. “I know how it sounds! But Rosita heard it too. She’ll corroborate!”

Suddenly, Dog barked. The herd was back and inbound.

Daryl rushed to look out the window. “Shit,” he swore. “They’re gonna cut us off… Look, you two get him outta here. I’ll distract ‘em, lead em away so you can cover some ground. This dun make any damn sense,” Daryl said, pacing the length of the barn.

“They shouldn’t have doubled back like that and they definitely shouldn’t have followed us to the barn,” Jesus agree, shouldering Eugene’s weight with Aaron.

“It ain’t right,” Daryl agreed. “Alrigh’, go. Go! I’ll lead ‘em off. Go! C’mon boy!” Dog rushed after Daryl as the other three made their way slowly in the opposite direction.

Daryl and Dog pounded the pavement as fast as they could until they reached a dilapidated trailer house on the side of the road, not too far from the fork where he’d separated from the others. Daryl hurriedly heaved himself up on the top and withdrew some firecrackers from his bag, flicking his lighter, and lighting the fuse. He tossed them out onto the pavement and they soon were popping and banging with a burst of sound that echoed up and down the lonely road. Dog barked at the herd in the distance and Daryl watched as some of the walkers began to turn toward him and away from the direction of Eugene, Aaron, and Jesus. “Keep ‘em comin’ boy,” he called down to Dog, squinting in the fog and darkness.

All was as it should be at first; the walkers were following the sound. And then suddenly, they weren’t. The ones who had veered off were suddenly pulled back the way they had come as if drawn by some magnetic force correcting their course again. Daryl couldn’t believe what he was seeing. He hurriedly hushed Dog and stared, bewildered and desperate as the horde continued in the direction of his friends.

“Shit,” he muttered. “Shit!”

Daryl hurriedly slung himself over the edge, hung from the edge and then dropped down onto the ground. Dog ran up beside him. Huddled in the grass, he wondered frantically what to do. He had to get to the others—they wouldn’t know what was coming until it was too late. But how?

“Fuck it,” Daryl muttered, straightening up and dashing across the road into the brush on the other side. He followed parallel to the walkers, trying to get ahead of them so he could reach the others, but it was hard as they walked on the old highway and he had to scramble through windfalls and brambles, Dog bouncing in front of him. He found the path of least resistance suddenly cutting closer and closer to the road and the horde.

Overhead, lightning flashed and thunder rolled. Daryl ducked low in the shadows, eyeing the progress of the walkers, constantly trying to pass them and stay hidden. Soon the developing fog was closing in around him and he could barely see ten feet. Suddenly, Dog let out a low growl and Daryl froze, sensing some mass behind him. His hand twitched to his knife and he withdrew it. He spun and was face to face with a lunging walker, its hands raised and slashing like claws. He struck with his knife and it dropped. Daryl stumbled backward and swung his bow off his shoulder as his back hit the trunk of a large tree. He fired a bolt as another figure emerged from the fog reaching for him. Dog leapt and attacked as another walker stumbled forward. Daryl readied his knife again. They were closing in. He was hemmed in on all sides, the tree at his back, and as he stood, trying to prepare himself, panic threatening to drown him as he faced the certainty of his own death, he did hear the whispers.

Kill. Kill him. Kill. Tear. Rip him apart. Kill.

“Dog! Here! Get back!” Daryl yelled, waiting for the next of the circle of walkers around him to lunge. He watched with confusion as a huge walking, lumbering toward him, was struck by an arrow, seemingly rained down from above. It fell with weight in front of him, tripping up another. Then Daryl was suddenly struck hard on the head by something which then tumbled down over his shoulder.

Distracted, he looked to see a rough-looking rope ladder with wooden steps cascading beside him from out of the tree. Another walker jolted forward, snarling, and Dog clamped down on its head and didn’t stop biting until it lay still. Daryl kicked another back to keep it off Dog. He craned his neck to look up the ladder, up into the huge old oak tree, but he could see nothing high up in the darkness and haze of the fog. There was a sudden moan and snarl and Daryl found himself holding off a walker at arm’s length, grappling with it to keep its snapping jaws away from his neck. There was a sharp swish and a rush of air and the walker he was fighting went suddenly still, an arrow buried in its face. Daryl had half a moment to note that the fletching was black as midnight before it fell at his feet.

More of the dead pressed in. He stabbed two more and another arrow from above pierced the head of a third. He glanced back up at the tree and the dangling ladder. Did he have a choice? He looked back at the circle of walkers pressing ever more closely in. Another couple began to stagger forward. Dog barked frantically, facing them bravely, trying to protect Daryl. No choice. He had no choice. “Dog! C’mon! Up! Get up!” He seized the bottom of the ladder and pulled it slightly out, using all his weight to hold it taught as Dog let out a nervous bark and then ran up it like a ramp at full speed, scrambling a little against the trunk and more vertical steps near the top but finally disappearing into the darkness under the eaves of the tree. Daryl heaved out a final breath, slung his bow across his back and scrambled up after him. He felt fingertips on his ankle and kicked hard to free himself but the grip was strong. Another rush of air and the sharp sound of a passing arrow and the grip disappeared.

He climbed, heart racing, until he arrived at a surprisingly large wooden platform, built in among the thick branches. He spilled onto it and lay flat on his back, trying to catch his breath. Dog surged forward, anxious paws tapping, and licked his face.

Daryl startled as a dark figure moved beside him and quickly heaved the rope ladder up, rolling it into a neat coil and dropping it onto the platform before retreating again to the other side to lean back against a particularly large offshoot of the tree trunk. Daryl hurriedly rolled over and sat up on his knees, squinting into the darkness. Below, the growls and snarls seemed even louder and he could still hear the faintest rustle and hush of whispers woven in among them.

Dog circled and sat beside Daryl, peering with interest at the dark-clad figure. Daryl waited with bated breath for a long time to see if they would speak. They didn’t.

They were set back in shadow and he couldn’t make out much about them at all until lightning burst overhead again and he could barely see that they had on a sort of dark cloak with a hood and clutched a bow in one hand.

There was an increasing roar of crackling and rustling all around him and Daryl realized that it had started raining, but he felt no drops falling on him. Looking upwards, he saw with the next burst of lightning that there was another platform above him. He glanced back down at the figure. They were still unmoving. He watched as they set their bow aside and then raised their hands and pushed back their hood. Another fork of lightning lit the sky.

He gulped. His heart did a strange lurch in his chest. He was staring at you, and you were staring back at him. He was at a loss for anything to say. Below, the growls and snarls went on and on…

You were studying him carefully, your eyes narrowed, lips parted a little and slightly pursed.

He attempted to clear his throat, but it felt tight all of a sudden. “‘M Daryl,” he said, having to nearly yell over the torrent of rain and continued rolling booms of thunder.

You reached for your bow again, not taking your eyes off him.

“I—I think ya just saved my life. And Dog’s too. Well—I know ya did,” he said lamely, trailing off.

Instead of responding, he watched as you slung your bow on one shoulder and then turned and started to climb up the large vertical branch you’d been standing in front of with an agility and speed that was astonishing.

“Wait—hey!” he called after you.

But the tail of your dark cloak was already licking around the platform above and you were gone. Dog trotted over to where you’d been, sniffing and then looking up the branch. He let out a low whine and wagged his tail.

“What the fuck?” Daryl muttered, climbing to his feet and going to stand where you’d been. He examined the tree trunk, half-expecting to find steps or footholds drilled in that allowed you to climb so swiftly but there was nothing but the rough bark of the tree. He ran his fingers over it. He couldn’t imagine how you’d gotten a hold. Another bright burst of lightning shot through the sky and a loud boom of thunder rolled. Daryl backed away from the edge and sank down in the middle of the platform beside his pack and crossbow. He hauled his bow onto his lap, set another bolt in the flight groove, and drew it back so it was ready to fire in a hurry if needed. There he sat, rigid, staring into the darkness around him, Dog at his side.

His heart sank as he thought of Jesus, Aaron, and Eugene. He hoped they were safe. What a massive fucking misadventure this had been. But as he sat clutching his bow, wondering who the fuck you were, why the fuck you’d helped him, where the fuck you’d gone now (up the tree?), his mind did continually wander back to the whispering... He’d heard it. Exactly as Eugene had said. And the herd had behaved unlike any other he’d ever seen. They’d doubled back. They’d ignored the lights and sounds of the firecrackers. They’d rerouted. They seemed to move with purpose. They didn’t just wander. He didn’t know what it meant, why it occurred, but it was terrifying. _ _ _ _ _ _

Daryl awoke with a start when Dog let out a soft woof and he shot upright, grappling for his bow. He hadn’t meant to fall asleep, especially being twenty-five feet in the air, but he had finally succumbed to exhaustion when the storm had passed in the wee hours of the morning. His back was stiff and tight from sleeping on the hard wood and he attempted to stretch to relieve the worst of it but was far too aware of you staring at him.

Now, he was looking back at you in the light of morning where you’d just climbed down on another ladder from the upper platform. This ladder passed through a hole in the platform above and he again remembered how skillfully you’d ascended without it the night before.

You were still dressed in mostly black, but the cloak and hood you’d worn during the night were gone. Along with your bow and a quiver full of arrows, there was a small bag slung across your body and you knelt and slipped it off. You flipped it open and pulled out a thermos and a chunk of crusty bread. You thrust them toward him and he eyed them somewhat warily. You finally just set them down and then stood, shifting your bow and quiver to the side, and leaning back against the tree trunk in the same way you had the night before. You crossed your arms over your chest and surveyed him.

Your eyes were bright and the colors seemed to flash in the morning sun. Daryl gulped and then cautiously reached for the bread and thermos. He unscrewed the top and sniffed its contents. Steam rose up and it was accompanied by an earthy and slightly sweet smell. Hot tea. Tea… in a tree? He was baffled. Did you have a fire up there somewhere? A stove? What the fuck? he thought for the hundredth time in a day’s time.

He looked up at you again and set the thermos aside. His eyes flickered down to your quiver. The feathers of the fletching were all glossy black. He swallowed the lump in his throat. “Ya found my knife the other day.” A long beat of silence. You were unreadable. “Why’d ya—hang it back up for me to find?” he asked. “Ya knew I’d come back lookin’?”

Still nothing.

“Were ya watchin’ me out here before?”

Silence.

He was getting slightly annoyed. “Christ, d’ya speak at all or—”

“Yes,” you said suddenly. “I do.”

Now, Daryl’s mouth was hanging partially open.

“But I’m not in the habit of speaking with strangers.”

“Well,” he straightened up a bit, clearing his throat, “’M Daryl. And this is Dog,” he said, ruffling the Malinois’ fur. He waited to see if you’d reciprocate the introduction but you merely shifted a little. Daryl chewed on his bottom lip nervously.

“How’d you get mixed up in that mess last night anyway?” you asked him. You couldn’t help studying his every little movement closely, watching for a microscopic flash that something was off, waiting for him to suddenly reveal himself to be something… dark. But you saw nothing like that. Not yet, anyway. But he was obviously strong, capable. Careful, you cautioned yourself mentally.

Daryl’s stomach turned as he thought again of Eugene and Aaron and Jesus. He scolded himself for not thinking of them until now after waking up. “S’kinda a long story,” he drawled. “I was tryin’ to lead ‘em away from somewhere. Guess it backfired.”

Your eyebrows lifted. “Lead them? Of course it went wrong,” you said, looking at him like that was the most obvious thing ever, or maybe more like he was a fucking idiot.

His brow furrowed low over his blue eyes. “What d’ya mean?”

“Well, the shepherds, obviously,” you said, deadpan.

“The—who?”

You straightened up, perplexed as you stared back at him. “The shepherds.” There was no understanding or recognition on his face. “Of the dead.”

Daryl only stared back at you, utterly confused.

You shook your head a little. “Couldn’t you hear them?” you asked him.

Finally, he nodded. “Ya mean the—the whisperin’?”

“Yes. It’s the shepherds,” you said again.

He still looked confused. You sighed and walked over the coiled ladder and nudged it off the edge with your foot. “Come down. I’ll show you.”

Daryl watched you slip down with ease and then glanced at Dog. “Stay, boy,” he said, and he followed more clumsily down the ladder behind you, feeling cautiously with his boots for the next step. He felt overly large and awkward behind you. When he planted his boots back on solid ground again, he was surprised to see the number of dead walkers lying at the base of the tree. You had shot more than he’d noticed the night before in all the chaos. Most had a thick arrow shaft capped with black feathers protruding from its head. You went about collecting your arrows. You paused at the last one and gave him a significant look before rolling it over with your boot so it was facedown. You bent and Daryl moved closer. “Here. See?” You pointed at the back of the head. At first, Daryl didn’t understand what he was supposed to be looking at. You withdrew a knife from your hip with a skillful movement and slipped the blade up the back of the head. It was as you did this that Daryl finally saw the lacing, like a shoelace, on the back of the head.

“What the hell?” he growled.

Once the lacing was cut, you gripped the scraggly hair on the top of the head and tugged. The whole head seemed to come off at first until he realized it was slipping off like a mask. You held it up with a disgusted look on your face for him to see.

“Jesus fucking Christ,” he drawled. He turned the body back over and found himself looking at a person. Not one who had ever turned to the undead, but the very human-looking corpse of a person dead from your arrow the night before. He stood up, in slight shock.

You dropped the horrifying mask to the ground. “They wear skins, herd the dead. They walk with them. Control them,” you said. “The shepherds.”

“Why?” Daryl asked.

You didn’t answer, simply stared at him stony-faced, sheathed your knife, stuffed the arrows you’d collected back in your quiver, and climbed the ladder back up into the tree.

As a last thought, Daryl grabbed the mask and crammed it into the inside pocket in his vest. Then, he followed you back up.

Daryl found you sitting at the edge petting Dog when he pulled himself back onto the platform. The bread and thermos were still sitting there in the middle and his hunger reared its head. He grabbed the bread and sank down beside his pack and bow again.

“What d’ya know ‘bout these shepherds?” he asked you again. “These—Whisperers?”

Your eyes flickered up to his face and then back to Dog as you picked a burr out of his coat. “They almost killed you last night. What more do you need to know?”

“Alrigh’…” Daryl drawled, biting off another piece of bread. “Ya ain’t even gonna tell me yer name? Where ya came from?”

Your eyes snapped up to his face again. “You don’t owe me your backstory and I certainly don’t owe you mine,” you said. You stood abruptly as the croak of a raven sounded nearby. “You led that herd right to my tree—”

Daryl’s eyes narrowed and his brow furrowed. “Ain’t like I did that on purpose. I didn’t know somebody was livin’ in a fuckin’ tree—it coulda been any tree in a thousand.”

“But it wasn’t. And I saved your ass—”

Daryl was slightly incredulous. “Ya want another thank you? Or an apology?” he asked, standing.

Your hand reflexively strayed to your knife as he rose to his full height. “And now I’ll have to move—”

Daryl continued to stare at you, baffled. The raven croaked again nearby. “Why the hell did ya even save me and Dog?” he asked.

“Should I not have?” you retorted. Abruptly, you tore your eyes from his face. “I think it’s time you go. I’m sure your people are worried,” you said, patting Dog once more time.

“Hang on—how d’ya know I got people?” Daryl pressed you.

“You have people,” you said.

“Do you have people?” he asked.

You ignored his question. “I can fit a harness on your dog to lower him down,” you said.

“Forget it,” Daryl growled. He shoved what was left of the chunk of bread into his pack and slung it across his back. He shouldered his crossbow. “Thanks for breakfast. Dog. Shoulders, c’mon!”

Daryl bent his knees and Dog propelled himself onto Daryl’s shoulders and balanced there. Daryl was bowed slightly under the weight and you watched, somewhat amazed as he navigated the edge of the platform and climbed the ladder back down. You leaned over and watched Dog jump down. Daryl readied his crossbow in his hands, prepared to set out.

You couldn’t resist having the last word. “Daryl,” you called down. He looked up. “You didn’t thank me, technically, for saving your life.”

Daryl peered up, disbelieving. “Last night, I said—”

“You stated a fact, that I did,” you interrupted. “That isn’t a ‘thank you’.”

He swore under his breath. “Hey, what the hell is your problem?” he growled back.

And for the first time, Daryl saw you smile, and his stomach seemed to somersault in his midsection. Just then, a huge raven swooped in and perched on your shoulder, letting out a raspy noise as a greeting and ruffling its feathers as you scratched beneath its bill affectionately. “Bye, Daryl. Be careful of the shepherds. And I’ll ask that you just go and forget about me.” And with that, you disappeared, and the ladder behind him slowly began to raise as you reeled it back up.

Daryl had seen a lot of shit in his time since the world fell, but this? You? Some mysterious woman living in a tree with a fucking pet raven? What the fuck... This was something else entirely. Forget about you? Not fucking likely.

#daryl dixon x reader series#daryl dixon fanfiction#daryl dixon x reader#daryl dixon twd#the walking dead#twd fanfics#daryl dixon drabbles#daryl imagines#daryl x y/n#fanfics#writers of tumblr#twd drabbles

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

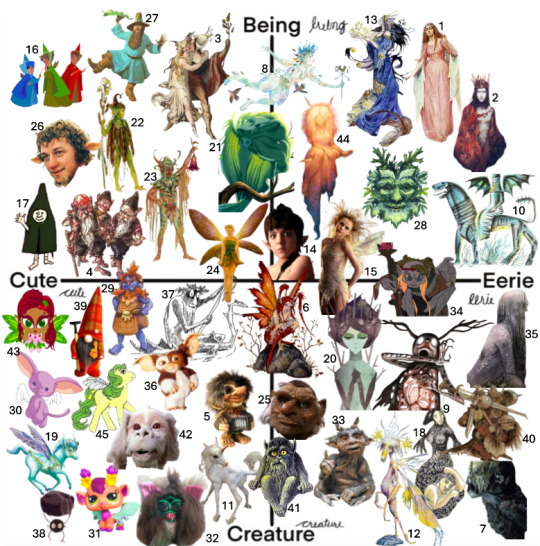

posting this on its own as well :) template and idea from @trollmaiden and full guide/sources under cut

"La Belle Dame sans Merci” by Henry Meynell Rheam

by Ayami Kojima

“The Fairy Lovers” by Theodor Richard Edward von Holst

Gnomes from the novel The Little Grey Men, written and illustrated by “BB” (Denys Watkins-Pitchford)

Nyform Norwegian troll

“Little Red Mischief” by Amy Brown

Faery from “The Hallow” dir. Corin Hardy, SFX by John Nolan

Ariel from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, illustrated by Jane Ray

The Beast from Over The Garden Wall, created by Patrick McHale

“Morgan Le Fay” by Clive Hicks-Jenkins

Unicorn foal sculpture by SovaeArt https://www.deviantart.com/indigo-ocean/gallery

Faery from Good Faeries, Bad Faeries by Brian Froud

“Dusk” by Stephanie Pui-Mun Law

Honeythorn Gump from “Legend” dir. Ridley Scott

Oona from “Legend” dir. Ridley Scott

Flora, Fauna and Merryweather from “Sleeping Beauty”, art direction by Eyvind Earle

Bilbo Baggins from a Dutch edition of JRR Tolkein’s The Hobbit, illustrated by Kees Kelfkens(?)

Selkie depicted on a Faroese stamp

Chortlebones from Bella Sara, illustrated by Lynn Hogan

Huldra from the game “Year Walk”

The Sprite from Fantasia 2000, segment directed by Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi

and 23 Costume designs for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Robert Courtneidge

As above

Tinker Bell from Peter Pan (2003) dir. PJ Hogan

Hoggle from Labyrinth, designed by Brian Froud and created by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop

Mr Tumnus from The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe dir. Andrew Adamson

Tom Bombadil from JRR Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings, illustrated by Tim Hildebrandt

The Green Man (source unclear)

Illustration for Terry Pratchett’s The Wee Free Men by Robyn Haley

Truffle from Adventure Quest

Littlest Pet Shop fairy

Woodland Furby made by me :) Please do not call him cursed

The Psammead from the BBC’s TV adaptation of E Nesbitt's Five Children and It, dir. Marilyn Fox

Thranduil, King of the Wood Elves from The Hobbit, dir. Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass

Nøkken by John Bauer

Gizmo from Gremlins dir. Joe Dante, creature design by Chris Walas

Gollum from JRR Tolkein’s The Hobbit, illustrated by Tove Jansson

Soot Sprite from Spirited Away dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Gonk

“The Junk Lady” from Labyrinth; concept art by Brian Froud

Domovoi by Vladimir Chernickov

Falkor from The Neverending Story dir. Wolfgang Petersen, creature design by Patrick Woodroffe

Cherry Fairy from Webkinz

Titania from Vertigo Comics, illustrated by Matt Dixon

Wind Drifter, My Little Pony G1

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ted finds him when the party has calmed down, just a smidge. (For a given value of ‘calmed down’: Colin’s singing along to some old Cher tune at the top of his lungs; Sam’s wearing a sparkling feather boa gifted to him by an ecstatic drag queen; Jan and Moe is locked into a heated debate over the European Union that is somehow also almost a rap battle and involves doing shots while several rapt onlookers cheer them on. Still, it’s fairly quiet compared to the utter euphoria of the first few hours after the penalty that gave them their promotion.)

Jamie’s slipped away to take a leak and make sure his hair is still on point (it is) and his nose is still okay (it is), and on his way back to the crowd he pauses for a moment, lingering by the door to take it all in, the noise, the laughter, the glowing faces of his teammates under the fluorescent lights. That’s where Ted finds him, walking up with a smile and offering him a bottle of beer.

”That was a real nice thing you did out there, handing that penalty over to Dani,” the gaffer offers without preamble. “A bold call, but a good one.” He pauses for a moment. “Can’t have been easy, giving up the opportunity to get us through to take a chance like that. ‘Cause I’m assuming you didn’t do it on account of being worried you were going to miss?”

And Jamie scoffs because really, he isn’t going to miss a penalty, is he? But the scoff is a passing thing, easily shrugged off, because he knows that Ted knows that, too. And it was a good call, and contrary to what Ted suggests, a strangely easy one to make.

It’d just seemed right. Pay it forward, like.

So he shrugs. Has a sip of the beer Ted’s handed him. “Yeah, well. Knew he could do it, didn’t I. I mean, I know he’s been all up in his head about poor Earl, that was some proper bad luck, that was, but. Sometimes you just need someone to believe in you, do you know what I mean? Get a second chance.”

He throws a furtive look at Ted, wondering if the gaffer gets what he’s getting at, or if Jamie has to spell it out, which he fucking won’t.

It seems Ted does get it, though, because his smile is knowing; pleased. “I couldn’t agree more. Always nice, though, seeing people make the most of the chances they’re given, right? Makes you darn proud of them.”

And that. Ah. That aches, a little, but not badly. Not the pain of a kick to the ribs, but the tingling, warming pain of blood flowing back into a numb limb.

Jamie lets go of a long breath. Clears his throat. “Yeah. I mean, I guess so, yeah.”

“Yeah, well, I know so.” Ted nods to the dance floor where Dixon’s just taking his shirt off and waving it over his head. Dani’s beaming at him and applauding like Dixon’s some rock star or something. “All right, you go on now and scoot your butt over there. Go celebrate with your team.”

“Yeah. I will, yeah.” But Jamie doesn’t move just yet; he pauses for a moment, hesitating. “Thanks, Coach. For. Well. Just thanks, I guess.”

Ted just shakes his head, still smiling. “Nah. Don’t mention it. All I need from you tonight is for you to have the best gosh damned night you’ve had all year, okay? You sure do deserve it.”

And well, gaffer’s got a point, don’t he? And it’d be selfish of Jamie to disappoint him now, right, so Jamie grins and throws back his beer and sets out to do as told.

#for all that ted and jamie just don’t quite get each other#i think they’re both trying#and probably have some good moments#jamie tartt#ted lasso#2x12#grace passed on#ficlet#my stuff

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earl Sweatshirt: A Geography of Grief and Growth

I made myself the poet of the world. The white man had found a poetry in which there was nothing poetic….I had soon to change my tune.

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

I suggest that we do not necessarily need to hear and know what is stated in its entirety, that we do not need to “master” or conquer the narrative as a whole, that we may know in fragments.

—bell hooks, “Teaching New Worlds/New Words” (1994)

Breakin’ ’em down to micro-fragments.

—Saafir, “Battle Drill” (1994)

What is asked of me is not to ascend but to descend.

—Robert Bly (1990)

1.

Earl Sweatshirt’s arc, swerving and dervishy, isn’t difficult to see, as we’ve witnessed it with him—we’re either interlocutors or interlopers, both with questionable motives. So when Earl looks back on school daze, as he does on “OD,” we look back with him (though ours is often an imperial gaze [HOW COULD IT NOT BE?]). We tee-hee and titter as we hear that “somebody tooted in the student commons,” tooted being the most puerile word for gas he could have chosen. An array of scatological options were ignored. It’s a deliberate gesture toward juvenilia. He doesn’t want his expression to be too mature, ha. He wants to welcome you to the romper room, ha. Remaining a kid until the moment he expires, apparently. So he sets the adolescent scene: the student commons. “The bell rang,” and the accused student was spared the prolonged opprobrium. In about four seconds, the student will begin to post. He “went home and argued in the comments,” channeling his embarrassment elsewhere, talking shit (shit) on the internet behind the safety and quasi-anonymity of a screen—an odd facade. He can walk right up to your avi and diss you. That’s his philosophy. The public humiliation replaced with a private self-possession. The discomfort of the crowd exchanged for the solace of solitude.

2. DID AN ANGEL SPEAK?

The sonics of “tooted” and “student” are twee, giggle-inducing. We laugh along with the concatenation of m and n phonemes [somebody | student | commons | rang | went | home | then | in | comments]. The near-homophonous commons and comments scan hysterical. With “OD,” it’s easy to confuse adolescence with adulthood. That “somebody” committed this social transgression seems defensive. Maybe it was him—the subject, Earl, Thebe—seeing as how the rest of the song is delivered in the first-person. Embrace the Age of Immaturity. Channel the Fat Boys: Darren Robinson’s flatulent beatbox. Place it beside the disorderly lyrics that Bobbito spits: “I write my own shit from finish to start, / Diminish the heart, / I eat a knish and then I fart.” Like the Cenobites, Earl kicks a dope verse, and only that. “I keep my sentences short,” he says on “EAST.” Beauty is brevity, brevity beauty. A “brevity pack,” as Earl has referred to the Feet of Clay songs. He strives to be live ’cause he got no choice. He runs his own business like James Joyce. In A Portrait of the Artists as a Young Man, a similar flatus incident unravels. At Clongowes Wood College (Stephen Dedalus’s Coral Reef Academy), a “stout student who stood below…on the steps” by the name of Goggins “farted briefly.” Sonically, the sentence shares much with Earl’s opening line. Dixon asks, in a “soft voice,” “Did an angel speak?” But the others react with bellicosity and name-calling (stinkpot; flamingest dirty devil). Goggins doesn’t retreat home; he simply asks, “It did no one any harm, did it?” You still bet that you can harm me, but you don’t alarm me, Goggins might say another way, reprising Del the Funky Homosapien, echoplexing Masta Ace.

3.

Earl “watched the doppler move,” the wavelength shift—the siren song of the “toot,” something insidious—or maybe it’s just the tremors we’re feeling. Woop, woop: that’s the sound of the beast, KRS would say. The frequency shivers. The shift, the movéd doppler, means Earl is immediately older, he’s the child who “get[s] introduced to violence,” even if he acknowledges the line was inspired by his nephew on a playground in South Africa, experiencing apartheid reincarnate as a whiteboy cuts him in line for the slide. Cranly, bullying Goggins, “shove[s] him violently down the steps.” The doppler moves. It slides into violence—like the violence visited upon the MOVE compound located at 6221 Osage Avenue in Philly in 1985. Gradations of black/white. ELUCID mentions the “gray on [his] face showing age” on his Osage (2016) project. Isn’t it strange—how the youngins can turn cold, hoarfrosty, in an instant? The grayscale cover to ELUCID’s tape is graced by a photograph of Birdie Africa, the sole child survivor of the siege. The bone fragments of the MOVE children have since been used in anthropology courses at UPenn and Princeton—case studies. It’s a good trope. Fascinating stuff.

4. TRYIN’ TO TRANSFORM YOU BOYS TO MEN LIKE DAYCARE

When JuJu of the Beatnuts asked, You want pain?, he wasn’t referencing the dramatical-traumatical pain Earl negotiates—JuJu’s question posed a ruffneck and ruffian pain on “Watch Out Now.” Somewhere closer to Marcy, where Jay-Z’s streets was watching. Earl clocks minutes, anaphoric with what he watches (I watched the doppler… / I watched a child…), much like Dylan’s portentous hard rain in which he saw endless racialized visions: “I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it”; “I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’”; “I saw a white ladder all covered with water.” For Earl, the ladder is a slide. The saw is watched. Witnesses all.

5.

In “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” bell hooks writes that she “came to theory because [she] was hurting”: “I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing.” hooks says that she “came to theory young, when [she] was still a child,” citing Terry Eagleton who argues that “[c]hildren make the best theorists.” Children, Eagleton insists, possess “a wondering estrangement.” No wonder, then, that “since a jit” Earl has found no use in “giving up.” He rather make it make sense.

6.

I beat you to the point. Having gained experience, there’s nothing you can tell Earl that he doesn’t already know, that he hasn’t already seen. He’s seen enough, had enough. He doesn’t await the mob’s pursuit; he places the noose on himself, he RE: DEFines it within his own lexicon. His noose, therefore, “is golden.” He’s a young youth, rockin’ the gold [noose], DEATHWORLD goose. He speaks with criminal slang, with a split tongue like ELUCID. Where ELUCID was “true and living, actual—no dull axes, owner of all heads,” Earl is “true and living, lonesome,” with no skulls to keep him company. He has to square up with the “pugilistic moments” on his own.

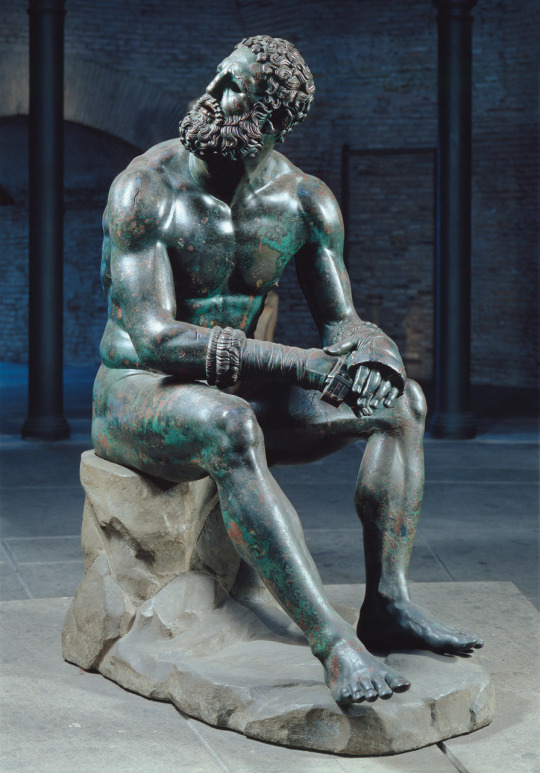

7. I AM OLDER THAN I ONCE WAS AND YOUNGER THAN I’LL BE

I’m thinking of “The Pugilist at Rest” (1991) by Thom Jones, whose epileptic protag describes a “grainy black-and-white photograph” of the bronze statue called The Pugilist at Rest. The pugilist, with a pocketful of mumbles, has “slanted, drooping brows that bespeak torn nerves” and a forehead “piled with scar tissue.” Torn nerves and scar tissue—sounds like the physical manifestations of grief. And, yes, Earl has grieved, and he continues to grieve—as listeners, we’re accustomed to his grief pedigree, as per Ka. In the past, Earl was “panicking a lot”—he just “want[ed] [his] time and [his] mind intact.” That’s a cold fact.

The narrator of “The Pugilist at Rest” readies himself for a cingulotomy—a psychosurgical procedure that will “cauterize a small spot in a nerve bundle in [his] brain.” In other words, he wants to keep his mind intact. The neurosurgeon promises the operation will lift “the heaviness of a heart blackened by sin,” which is what convinces the narrator to agree to it. Good grief, he thinks, he’s been reaping what he sowed. He “can’t go on like this,” barely living “with a deadening sense of languor,” a phrase which calls to mind Earl’s lethargic, slugabed flow. Feeling insane in the membrane, like he’s a Soul Assassinated, exploring the depths beneath his whooligan behaviors. 376 was a brothel. “Good and evil are only illusions,” Jones writes. In anticipation of the surgery, the protag considers the worst-case [so what, so what] scenario: “If they fuck up the operation, I hope I get to keep my dogs somehow.”

8. MOURNING & MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLIA

Grief carries its own antidote along with it.

—Charles Brockden Brown, Wieland (1798)

“Grief is the door to feeling,” Robert Bly says. But Earl, on “Grief,” told us he “ain’t been outside in a minute”—and that minute, whether we’re speaking with criminal slang like Nas on “It Ain’t Hard To Tell” or not, is an eternity. Earl hadn’t crossed that threshold, hadn’t kicked in that door. MIKE would realize it much later on “No Curse Lifted (rivers of love),” how you “had to walk through the grief,” even if it “was the worst feeling.” In 2015, though, Earl found these passageways distorted. Like the undulating photograph on the cover of his first mixtape. Like the blur-obscured selfie on the cover of Some Rap Songs. Like the static-scrambled cover of I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside. Earl’s dealt in fragmentary confuzzled noise for a full career. He’s been standing on the corner, red burnt, moving down alien lanes paved by GBV, greenthinking to himself. It ain’t hard to tell that Earl “don’t act hard” and yet is a “hard act to follow.” The density or opacity of his exterior notwithstanding, grief don’t come easy. “As men,” Bly says, “we’re taught not to feel pain and grief as children.” So Earl spits somnolent, numb-tongued and slack-jawed. Like he said on “Cold Summers”: muffle my pain and muzzle my brain up.

“I’ve been alone in my shit for the longest,” he spit on “Grief,” and in work as recent as “Vin Skully,” he’s still figuring out “how to stay afloat in a bottomless pit.” Bly says that “we receive something from our father by standing close to him—something moves over that can’t be described in material terms.” Bly speaks of being in a “conspiracy with his mother” from early on. Earl finds himself “thinking ’bout [his] grandmama” while he wallows and lies in a bottle. “Grief” catalogs all the things his mama taught him. Earl’s work, of late, is autodestructive. He peels away and pastes back haphazardly. He vibes with this Bly shit: “If you can deny something so fundamental as grief in the whole family, you can deny anything. And then how can you write poetry if you’re involved in that much denial?”

Bly goes on to quote Alice Miller, the psychoanalyst who gave us The Drama of the Gifted Child (1979): “When you were young, you needed something you did not receive, and you will never receive it. And the proper attitude is mourning.” Mourning is the proper attitude, not blame—mourning. Mourning makes its way through moaning and mumbling—Earl’s current intonation. On “Grief,” he “cut the grass off the surface [and] pray[s] the lawnmower blade catch the back of a serpent.” Philip Larkin’s poem “The Mower” (1979) leans more literal: “The mower stalled, twice; I found / A hedgehog jammed up against the blades, / Killed. It had been in the long grass.” Larkin’s speaker genuflects before the innocent critter, recalling how he “fed it, once.” Now, he mourns how he has “mauled its unobtrusive world, / Unmendably. Burial was no help.” Earl, of course, is less forgiving of the serpents in the grass. They’re threats, not friends. Still, a void opens up when the mower—(and let’s not forget the lawnmower is a modernized scythe)—does its mowing. Grief is the door to feeling, and on the other side:

Next morning I got up and it did not. The first day after a death, the new absence Is always the same; we should be careful Of each other, we should be kind While there is still time.

9. NOBODY KNOW WHO MADE THIS WELL, FOR IT WAS HERE WHEN I WAS BORN

“Come get to know me at my innermost…”

Riveting, Earl raps. Earl raps are riveting. We fix to the flow—riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s. We’re invited to know Earl, to become familiar, and his “innermost” is a constant vacillation between optimism and [afro]pessimism. The sudden switches—these switches on bitches like fixed with hydraulics—establish what Danny Schwartz, writing for Rolling Stone, called an “uneven terrain.”

Earl’s “family business [is] anguished,” and that’s recognizable. We’ve known Earl (on “Chum”) with the “pendulum swinging slow” and low. He holed up, hostage-like, in his “heart’s bottomless pit.” Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum” (1842) brand of captivity. “I was sick,” that narrator says, “—sick unto death with that long agony.” Something tells me there should be an exclamation point there (SICK!). Earl Sweatshirt was down, down, down. “I was in the fucking pits for like 10 months post my pops dying,” he said in an interview. The Spanish Inquisition ain’t shit.

But for these countless downs, “OD” tracks the ups like naloxone in the nasal membrane. “Now I need atonement,” Earl notes—he makes a case for reparations. He “sets the goal[s]” like some motivational speaker. If “half [his] wings is broken,” he can “spread the other for [his] brodie OD.” Somewhat circumspect as he’s “tiptoeing,” yet the approach is laden with “too much love.” Even when his “sister showed in a rut,” he’s joining arms with her and “getting over, sending up.” That rut she walks—like Eudora Welty’s worn path (1941)—is a path through the pinewoods, and she’s suddenly Phoenix Jackson. “She was very old and small,” Welty writes, and she moves “with the balanced heaviness and lightness of a pendulum in a grandfather clock.” Even with her pentium processing and pendulum low, she swings back up—the rise of her namesake. She screams phoenix, her feathers and flames are one skin. “Living in the moment,” Earl raps, and his craft is bars. “You been corrupt”—and, sure, who hasn’t?—but you recover with “some ginabot.” Welty’s Old Phoenix surveys a spring “silently flowing through a hollow log.” She bends and drinks and says, “Sweet gum makes the water sweet.” It’s the equivalent to Earl putting “shilajit in his sippy cup,” which is “healing cuts revealingly.” And, yes, from a “sippy cup,” so we’re back to toddling around again (“Since a jit,” he says). “I can’t give enough,” Earl raps, his last winding-sheet made of nard and myrrh.

10.

We crouch and teeter, caterwauling along the ledges, for we’ve got these clumsy feet of clay. This is the intended effect[/defect]; this is the rubble of what Earl calls the “crumbling empire.” This is us feeling the violent vibes of the “death throes” he speaks of. Why would we expect anything to resemble traditional song or rhyme structure when the earth quakes, civilization trembles, and Earl’s dungeon shakes? His chains have fallen off. The tenor is tremors. He’s living the trife life—hell on earth—but still living. Earl’s done trying to not look down—he embraces an outer appearance which scans dour; he deliberately gazes into the pit, inviting the vertigo, for it “haunts the whole of existence,” as Fanon says. But Frank B. Wilderson III promises a “vengeance of vertigo.”

11.

Gallons of rubbing alcohol flow through the strip, and Earl’s lips. He’s “refilling the pump”—his heart, yeah—but with a sawed-off shotgun, hand-on-the-pump posture. There’s “no concealing it,” not even with a concealed carry permit. He brandishes right back at “the enemy up in arms bearing snubs.” The mood swings; been down so long it looks like up to him. The turns require tourniquets. This is some Battle of Dak To torture—somewhere between Retaliation and the Heavenly Divine. Emotional turmoil seems violent by design, and Earl’s “memory [is] really leaking blood.” Fear not, the blood is “congealing, stuck.” Like Havoc says, “The Mobb rollin’ thicker.” Prodigy cites it, too: “This ain’t rap—it’s bloodsport.” But Earl has known that all along—he’s been “mobbin’ deep as ’96 Havoc and Prodigy did” since 2013.

12.

HipHopDX’s Kevin Cortez referred to listeners having to “sift through the muddle” in order to appreciate the bars, but where muddle suggests a disorderly conduct, a kaos network, Earl’s style, more appropriately, models. The woozy, wavy, and inner-conflict-war-torn vocals model an abstraction that anticipates the listener’s loyalty. This is what I’ve got, brief and cryptic as the gesture may be, the model says. Writing for NME, Dhruva Balram described Earl’s lyrics as “slurred,” but slurry is the form.

13.

If the empire can deploy Orwellian technologies of repression, its outcasts have the gods of chaos on their side…

—Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (2005)

So if we’re giving ourselves over to the woozes and waves, we’ll just as well find ourselves lost. Let’s go—like those tourist books run by students—and let’s wander eastward. Follow our napkin-scrawled directions and disorientations to a somewhere elsewhere. Let’s go east for a second, for a spell, on a lark, in the dark (word to AKAI SOLO). Earl’s bloodwork contains “pieces of slums”—or more aptly, [sLUms]. He’s hand-to-hand with that Jungle Boy MIKE, but also the god Mike Davis. “[T]he cities of the future,” Davis wrote, would be “constructed out of crude brick, straw, recycled plastic, cement blocks, and scrap wood.” Just the same as an Earl Sweatshirt verse is built—under the tutelage and overstanding-sharing, symbiotically, with MIKE. Davis says our cities aren’t “cities of light soaring toward heaven,” but a world that “squats in squalor, surrounded by pollution, excrement, and decay.” Smells like somebody tooted in the student commons. Smells like a slum village, something we’ve smelled before—possibly coming straight from the slums of Shaolin.

14. ACID EASTERNS

Earl trekked to the East and squinted into “one beacon in the dust weaving”—like Clint Eastwood arriving out of the hazy horizon ether of High Plains Drifter (1973). But Earl is heading to the East, blackwards. And though Brother J claimed you can’t define what’s direct from the East, Jeru told us on The Sun Rises in the East that you can’t stop the prophet either. So on “EAST,” Earl traverses a tricky terrain—it’s tricky, tricky, tricky because it’s an acid western landscape: an acid eastern.

The path isn’t direct or linear—it zigs and zags like rolling papers, and stimulates the same. “Double back when you got it made,” Earl says at the start of his journey “EAST.” The objective is to talk sense condensed into the form of a poem like Special Ed once did on “I Got It Made.” Instead, Earl’s poems—his L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poems—skew [non]sense, go form[less], and vaporize rather than condense. Lyn Hejinian in cinnamon Timbs: “constant change figures / the time we sense.” The narrative is hallucinogenic (note: “how the story careen against the bars”). Earl’s bindle contains “thirty racks and weed [with] no fat in the collard greens.” That’s how he gets funky on the mic like an old batch. That’s how he gets sincerity on the mic: “Off top it’s me—no cap, / I don’t bottle things.” That buck that bought a bottle could’ve struck the lotto, maybe. But Earl’s “canteen was full of the poison [he] need[s].” He gets where he’s going like El Topo, bereft. The “trip was long and steep”—that being an acid trip—so let me see you try to ride a horse into the chasms of the canyon.

“EAST” is a death meditation, a grand duel between Dantean and Donneian lyric voices [he damn-near well should’ve double-tracked the vocals]. In a 2015 interview with SPIN, Earl is asked about the worst thing he did that year, to which he replies: “Umm…acid?” He elaborates: “I took it at a time when I really didn’t need to be taking acid. I had like a fucking existential crisis at, like, four in the morning. But it was tight. We reeled it back.” Jodorowsky called El Topo (1970) an “eastern” in that it “incorporat[ed] ancient eastern wisdom in the materiality of American cowboys.” For Earl, it’s more a rhinestone cowboy—he holds the cold one like he holds an old gun (as evidenced in the “EAST” music video). DOOM was no stranger to grief, of course, and the rumors persist regarding the bad acid that precipitated Subroc’s early demise (“Bad Acid” also being the original title for “December 24”).

Estranged Earl, alienated—a high plains drifter (not Clint Eastwood, though) who rechristens a town “Hell” through a baptism of blood. Like the Beastie Boys’ version, Earl pulls out a pair of pliers and pulls a bullet out of his chest. He pulls through, true and living. “I’m long distance from my girl,” Mike D raps, so he’s “talking on the cellular,” but Earl is more alienated than that—beyond racking up roaming charges, immersed in dead zones. He “lost [his] phone and consequently all the feelings [he] caught for [his] GF.” Relationships can’t be sustained in these bleak and barren locations. All the blood has been drained from the ruddy faces—sanguine scenery. In his essay “On the Acid Western,” Jonathan Rosenbaum discusses how the subgenre “refuses to respect or valorize bloodshed.” Memory really leaking blood. Congealing. Stuck. To paraphrase Rosenbaum, Earl’s acid eastern “formulat[es] a chilling, savage frontier poetry to justify [his] hallucinated agenda—a view at once clear-eyed and visionary, exalted and laconic, moral and unsentimental, witty and beautiful, frightening and placid.” Earl’s “innocence was lost in the East,” and obsessives speculate whether this refers to Samoa or New York City—how far east we going? Countless spirit-questers pit-stopping at ashrams, searching for that Gifted Unlimited Rhymes Universal guide.

“I wait a beat,” Earl says. His canteen stays filled, auto-replenishes. His “cognitive dissonance shattered” and the “necessary venom restored.” Jodorowsky reportedly once taped snakes to his chest for an experimental theater performance. As if it matters if you think it matters anymore. Or, as ELUCID says, “Words mean things but don’t have to.” Acids and bases. Occident and Orient. Western and Eastern. Up is down.

15. NOTHING LIKE US EVER WAS

Earl’s “EAST” accordion beat—or whatever Orkes Gambus Al Fata instrumentation is at work—is more madcap than madvillainous. In my head is Erick Sermon, though, speaking about how “the flow slow…like a jazz player, or someone on the accordion” on “Knick Knack Patty Wack.” But I’m less concerned with the flow of air through bellows—compressing and expanding—than I am with Earl’s rendering of wind. (Somebody tooted.)

“Let the dead be dead,” Carl Sandburg says at stanza’s end in “Four Preludes on the Playthings of the Wind” (1920). Later, he reports, “The only singers now are crows crying.” And so Earl, a lonesome crow, reminds us—and himself—that “the wind get the ashes in the end” on “December 24.” The whining, wheezing consonance of /-nd/ in “wind” and “end” manages to evoke both the wind itself and the circularity of life. The bar whooshes and whips until we’re at our end, the terminus. That circularity, that full circle: ashes to ashes. “We are the greatest city,” Sandburg repeats, “the greatest nation: / nothing like us ever was.”

Global winds be blowin’—[Of the Soul]—and so billy woods cites that same line on “Haarlem”: “Thebe said the wind get the ashes in the end, bruv.” Check the configuration of the rhime:

The wind | gets | the ashes | in | the end {birth} {life} {death}

Even that get does work—whether it’s the violence of Death Grips’ “get got”; Too $hort threatening you to “get in where you fit in”; or the satirical sadism of Keenen Ivory Wayans’ I’m Gonna Git You Sucka. The wind wins out—it gets what it wants. On “EAST,” the wind—infinitely personified—“whispered to [Earl], ‘Ain’t it hard?’” It ain’t hard to tell that it is. How about some hardcore? Yeah, we like it raw like M.O.P. But those burns yield ashes. In Adrienne Rich’s poem “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children” (1989), she struggles with the words she uses, knowing “[t]his is the oppressor’s language / yet [she] needs to talk to you.” I know it hurts to burn, she writes, but writing is no less ardent. “The typewriter is overheated, my mouth is burning.”

Let me bring it back to Robert Bly. “In the ancient times,” Bly says, “the movement for the men was downward—a descent into grief. It’s referred to in the fairytale as ‘the time of ashes.’” Ashes, he explains, is the “code word for the ‘out of it’ time.”

We know what it is like to take ashes in our hands. How light they are! The fingertips experience them as a kind of powder… Ashes, we note, find their way into the whorls of our fingertips, cling there, make the whorls more noticeable, more visible, more clear to us. We can take our own fingerprints with ashes.

Ashes, then, aren’t simply for the wind’s taking—ashes are for us, are necessary for us to transcend the grief the boys, the men, and the man-child experience. Bly points to the various cultures that have used ashes in initiation rites: “Ashes Time is a time set aside for the death of that ego-bound boy.” Ready to give up, so you seek the Old Earth. The elders cover your face—even your whole body—with ashes “to make [you] the color of dead people and to remind [you] of the inner death about to come.” Consider Earl’s ashen white face produced in the negative imagery of the “Grief” music video.” “The word ashes contains in it a dark feeling for death,” Bly says. “Ashes when put on the face whiten as death does.”

Earl Sweatshirt is a far cry from knocking blunt ashes into caskets.

16.

Feet of clay, hands of light…

—Moor Mother and billy woods, “Furies” (2020)

For Cheryl I. Harris, Earl’s mother, the feet of clay refer to a vulnerability we all possess no matter how formidable we may appear to become. Earl invokes the King of Babylon’s dream, a dream of an idol “meant to represent all the empires of the world,” echoing Sandburg’s imperious “greatest nation.” Earl believes “we at the feet of clay right now…We posted up live from burning Rome.” Imagine the ash pile. So Earl is here, ostensibly, to turn the disco into something dismal—how Mtume becomes “MTOMB” with its entombed sonics, as if he’s rapping from within a wall, the victim of some Poe immurement.

17.

“I remember woods,” Earl raps on “OD.” “I remember Endom when he wasn’t remembering much, / I remember love healing the ruptures.” I remember is also the refrain and title of Joe Brainard’s poem-memoir, a term which aptly describes much of Earl’s recent output. Brainard’s memories bum-rush into the present:

I remember a dream I used to have a lot of a beautiful red and yellow and black snake in bright green grass. I remember painting “I HATE TED BERRIGAN” in big black letters all over my white wall. I remember liver.

If Earl recalls love “healing the ruptures,” then he also likely recalls Fanon: It is essential to convey to the black man that an attitude of rupture has never saved anyone. But Fanon also speaks of young Black men “maintain[ing] their alterity. Alterity of rupture, of conflict, of battle.” Earl, “feeling rushed, grew up quick.” He echoes Biggie, who “grew up a fucking screw-up,” and Raekwon, who “grew up on the crime side” (though Earl’s mama taught him, as we know from “Grief,” how to avoid the pigs, persecution, and prosecution). Eyes on the clock, Earl acknowledges this “trip around the sun” is his “25th,” so “give it up”—his survival alone deserving of a standing [on the corner] ovation. He celebrates life with “gin and rum.” Again, notably not gin and juice—murder was never the case. The only death is the inner death, the death of the ego-bound boy, that Bly describes. Earl’s gin is the drink of be[gin]ning, of genesis (“Light them Phillies up then…”), of Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, when I was dead-broke, man… “We wasn’t supposed to be alive,” Earl says, yet here he stands.

18. RUMINANT

Stare at the Feet of Clay album cover—an evocation of folkloric imagery: a Grimm forest with gnarled tree branches—and the enchanted, diabolic goat lying in wait. Earl’s parasocial following speculate G.O.A.T., of course, but I’m more inclined to mythopoeic possibilities. The Feet of Clay goat glares like Baphomet but frolics like a faun over fractured beats. “OD,” Earl has stated, “brought [him] up out of [his] little wreck”—a wreck of wracked nerves. Adrienne Rich encourages “diving into the wreck” (1973).

I am blacking out and yet my mask is powerful it pumps my blood with power.

Earl’s right there with her, submerged and blacking out, but still surviving: Really leaking blood, but refilling the pump.

In her essay “Teaching New Worlds/New Words,” bell hooks invokes Rich’s struggle to navigate the “oppressor’s language.” For hooks, as a Black writer, managing that is even more difficult and historical. “I think now of the grief of displaced ‘homeless’ Africans, forced to inhabit a world where they saw folks like themselves, inhabiting the same skin, the same condition, but who had no shared language to talk with one another, who needed ‘the oppressor’s language.’” hooks explains how Black folks have “remade that language so that it would speak beyond the boundaries of conquest and domination.”

Earl Sweatshirt, especially in his later work, has “altered [and] transformed” English, just as “enslaved Black people took broken bits of English and made of them a counter-language.” The emotional wreckage is also a linguistic heap of fragments—micro-fragments, if we’ve learned anything from Saafir. Earl, in the tradition of his ancestors, “put[s] together [his] words in such a way that the colonizer ha[s] to rethink the meaning of the English language.” “The grammatical construction of sentences in these songs” by Earl, just as by the spirituals of hundreds of years prior, “reflect[s] the broken, ruptured world of the slave.” That crumbling empire Earl mentions was faulted by feet of clay.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2019, sharing a dais with his mother, Cherly I. Harris, Earl spoke to this lineage directly: “Rap music is slave music—the modern-day iteration of it. Slave communication had to be encrypted. You got a code.” He shifted: “If I know what I’m saying…I can teach it to you.” On Feet of Clay, Earl is teaching to transgress. “I’m cracking my own code,” he says to an audience member during the Q&A, “how it comes out garbled…,” and then he trails off, as if making a deliberate effort to keep his answer cryptic.

hooks always saw language as “a site of resistance.” This included the incorrect usage and placement of words—she called such practices a “rebellion.” Weaponizing syntax. hooks recognized rap music as a continuation of this fight—the latest [sound]clash, hip-hop artists as rebels without a pause—while still acknowledging the collateral damage it might cause.

Rap music has become one of the spaces where black vernacular speech is used in a manner that invites dominant mainstream culture to listen—to hear—and, to some extent, be transformed. However, one of the risks of this attempt at cultural translation is that it will trivialize black vernacular speech. When young white kids imitate this speech in ways that suggest it is the speech of those who are stupid or who are only interested in entertaining or being funny, then the subversive power of this speech is undermined.

Or, as Earl once said on “Chum,” “Too Black for the white kids and too white for the Blacks,” an axiom he’s come to loathe. Perhaps Fanon had the better bar on this subject: “The white man had the anguished feeling that I was escaping from him and that I was taking something with me. He went through my pockets. He thrust probes into the least circumvolution of my brain. Everywhere he found only the obvious. So it was obvious that I had a secret.”