#Cornish tin mines

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

7th June

St Meriasek’s Day / St Colman’s Day

Miners Enjoying “Croust Time”, East Pool Mine, 1893. Source: Mac Waters/ cornwallforever.co.uk

Today is the feast day of both St Meriasek and St Colman. Meriasek is the patron saint of tin miners and therefore historically a very significant figure in Cornwall. As late as the 1890s, clay images of the saint were put up at the mine’s entrance by the men for good luck. At the beginning of each shift the miners would intone Meriasek we pray thee to invoke his protection. Also, if the miners came across a snail during their work, they would drop some lantern wax on the creature “for luck”. What the snails thought of these encounters is not clear.

St Colman had a well dedicated to him at Cranfield Church, on the shore of Lough Neagh near Castletown in County Antrim. The well offered the usual curative remedies in return for coins. The well was cleaned in the 1970s and a fine collection of deposited coins was discovered. Allegedly, despite it being bad luck to steal the well’s offerings, one of the workmen helped himself to some. He was killed by a car on his way home.

0 notes

Text

It’s rather lonely being the only one in your little freak corner of hyperfixations

#Cornish history specifically shipping trade/tin and copper mining/agriculture/language then and now#not really something I can get other folk involved with#save the odd shipwreck#but liiiiiike#I care I care so much#I once cried when I found some coal on a walk#I will and have taken people to the mat who called Kernowek ‘not a real language’#I care about the local history and the impact on a global scale#I!!! NEED!!! BUDDIES!!!!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#cornish mining#steam power engines#engine houses#tin#copper#beam & bob#mining in cornwall#mine workings#industry#technology#geology#science physics

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A weird giant piece of machinery I was very scared of in a dream. It was some kind of pump or some part of a tin mine. It was around 30ft tall? It went up and down when the mine was moving. Probably inspired in some way by real life mining equipment as I grew up in Cornwall. No idea why it instilled such intense fear in me in this dream but I could barely look at it let alone get any closer to it. From 2010

#dream#dreams#dream imagery#dream analysis#tin mine#mining#mining equipment#weird fears#an oddly cornish fear#fear#phobia#megalophobia#2010

1 note

·

View note

Text

St. Piran’s Day Special: The Tommyknocker

~ ~

Our second Celtic Month piece celebrates St. Piran’s Day, on March 5th, the national day of Cornwall. Have some pasties! Mine some tin! Talk like a stereotypical movie pirate; but not if anybody Cornish can hear you.

Before you read what the piece means to me, share what it means to _you_. I’m just the artist; you’re the beholder.

Leave a comment.

~ ~

This was actually the first Spring Vignettes piece I created; and I think it remains the best, for its elegant minimalism and flawless composition.

I said in the last description that the Welsh are the survivors of the Celtic Britons; but they aren’t the only ones; because the Cornish still remain. The Cornish language went extinct in the 18th or 19th Century, but it’s currently being revived. Long may the Cornish language and people endure.

Cornwall is known for its tin-mining. During the Bronze Age, tin was one of the two ingredients of that era’s eponymous metal; and while copper could be found around the Mediterranean, traders needed to import tin from far afield to supply the great empires of the Near East. Cornwall has likely been one of those sources since very ancient times.

According to legend, St. Piran, patron saint of Cornwall and tin-miners, rediscovered tin-smelting when his black hearthstone put forth a pool of liquid metal that formed the shape of a cross. To this day, the flag of Cornwall is a silver cross on a black field.

Tin occurs in the form of a pitch-black ore, cassiterite, which forms distinctive rhombic crystals.

Cornish miners tell of a subterranean fairy-being, called a knocker or tommyknocker, that inhabits the deep and guards its precious ore. Provided they’re on friendly terms, tommyknockers can protect miners, lead them to veins of ore, and warn of collapses by knocking on the walls. On the other hand, if disrespected, they can steal tools, extinguish lights, or even collapse mines. It’s customary to toss the last bite of your pasty to the tommyknockers, to keep their good favor.

Cornish pasties, a savory hand-pie, are a cherished part of Cornish cuisine; usually filled with beef, potato, rutabaga, and lots of pepper. The parameters of an authentic Cornish pasty are heavily regulated by the Cornish Pasty Association. If you ever find carrots in a Cornish pasty, it is generally agreed that you should throw it back in the face of whoever gave you it; because carrots have no place in a Cornish pasty. They’re a savory food, and carrots are too sweet. If you find a pasty containing anything sweeter than carrots, you should probably stomp on it.

Fun fact: The style of speech now popularly associated with pirates is by origin a highly stylized version of a Cornish accent. Those in Cornwall who don’t delve in the mines likely sail on the sea; and the accent was well at home among salty sailors with many yarns to tell during the Age of Sail. Many rounds of iterated exaggeration eventually produced the absurd caricature recognizable throughout the English-speaking world today. Cornish English is rhotic, which is to say, R is pronounced even when it is not before a vowel; and while this feature is common in North American English, it stands out among the other dialects spoken in Southern England. I wouldn’t wonder if this was the reason for the greatly exaggerated Rs in the stylized imitations.

The interjection “arr” is actually known to be used in Cornwall, where it is synonymous with “aye”, “yea”, and “yes”.

#st_pirans_day#cornwall#cornish#knocker#tommyknocker#tin#mine#miner#cave#celts#celtic#spring#springholidays#digitalart#vector#mosaic#collage#inkscape

1 note

·

View note

Text

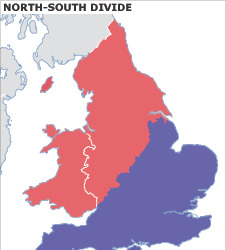

England doesn’t have a North-South divide. But if it did have one, Cornwall would be in the North.

Now I’m not saying there isn’t a big geographical divide between like, Manchester and Canterbury, or that the country’s a homogeneous patchwork, what I’m saying is this divide isn’t north-south and thinking about it as such masks a lot of things.

Oh, and I am, for necessity of discussing this divide, going to be ignoring the Midlands. I hope you forgive me ignoring the deep cultural ties between Birmingham and Rutland.

Map Men made a video about the North-South divide in England (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENeCYwms-Cc&ab_channel=JayForeman), which focused on the line determined by Danny Dorling in 2008.

… Which isn’t a north-south divide. It’s a northwest-southeast divide, going up at more than 45 degrees – it’s more an east-west divide than it is a north-south. It also includes Wales in “the North” but we’ll get to that.

But it was a north-south divide he set out to find, so a north-south divide he sort of drew, excluding exclaves and enclaves where the metrics he was looking at would make that not a north-south divide.

Notably, several would seem to put the west country peninsula in “the North”… So what’s up with that?

(Dorling's full paper is here, and I recommend looking through the whole thing to see how he arrived at the divide he eventually concluded: https://www.dannydorling.org/wp-content/files/dannydorling_publication_id2938.pdf)

Anyway. This is what’s up with that:

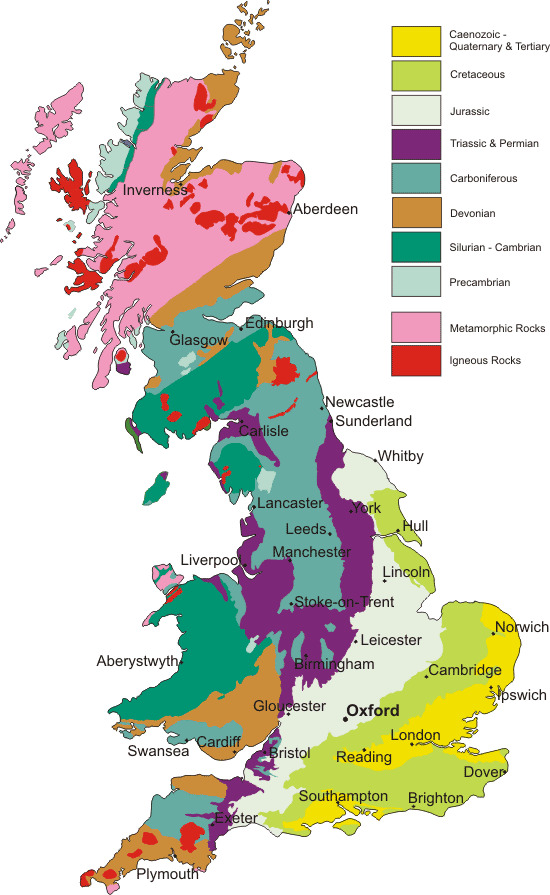

This is a geological map of Great Britain (and the Isle of Man, which isn’t actually part of the UK or any of its constituent countries but I guess it’s here anyway.)

Here again, in the boundary between Jurassic and Triassic geology, is that diagonal line from the Humber to the Severn, but continuing past both. For convenience, here are those two lines superimposed on one another.

With Danny Dorling’s line (frequently following county boundaries or other administrative boundaries) in blue, and the geological divide in red.

One line was drawn in 2008, the other has existed over 200 million years.

This isn’t a coincidence – it’s the reason for the divide.

What made “the North” is the industrial revolution. And one thing that drove the industrial revolution was the mines: coal, iron, silver, tin, the rocks beneath our feet and the people who dreamed they were worth more than the people they sent into the dark to bring it into the light.

Towns grew around mines, from Walker to South Crofty, and more than just the mines defining them, it was the mines closing that would cement the divide.

“Byker Hill and Walker Shore, collier lads forever more”

“Cornish lads are fishermen and Cornish lads are miners too”

- Two folk songs about regional identity’s roots in its industry, from opposite ends of this dividing line

In the West Midlands, the Black Country didn’t earn that name with caviar; it, like Manchester and Leeds, reinvented itself when the industry collapsed: cities built in the brick ruins of the temples built to the exploitation of the workers, blackened by the smokes of the cremation of its labour industry. When the light catches the steel and glass just right, you can still see the ghosts.

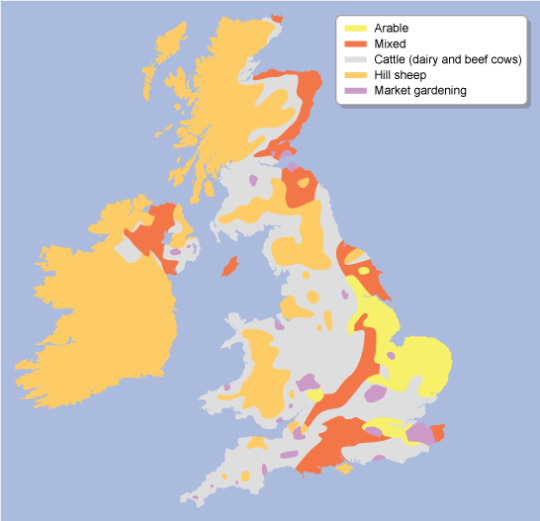

Even the country life outside the cities is shaped by this geology: the terrain north-west of this line doesn’t lend itself to large, flat expanses of land for arable farming, and the divide is visible again when looking at agriculture:

With the majority of land south of the Jurassic-Triassic line being arable, mixed and market gardening, with a fair amount of cattle in the Cotswolds and Chilterns and along the north side of the Thames, and the majority north-west of it being cattle and sheep – which are almost absent from the south side of the divide with the exception of the Isle of Wight and therefore, ironically, Cowes.

Not all farming is the same, the yearly flow of labour and of marketable goods between livestock and arable having little in common beyond being intensive work out-of-doors and taking huge amounts of land to accomplish.

But one thing that also goes hand in hand with this is that sheep aren’t mostly farmed for their meat but for their wool, and what drove industrialisation in the Pennines was the steam-loom: the mechanisation and mass-production of wool.

(Incidentally, on this map arable farming and market gardening also correlate with several types of English traditional dance: Molly, Border an East Midlands and East Riding plough dances, which began as a way for seasonal farmhands to make ends meet by busking with menaces in the winter off-season, but that’s for a later Morris ramble).

But hang on, that puts Hull on the same side of the divide as Kent, not, for example, Liverpool. So what gives there?

The East Riding isn’t built on mining - a kid with a bucket and spade could find the water table in most of the county.

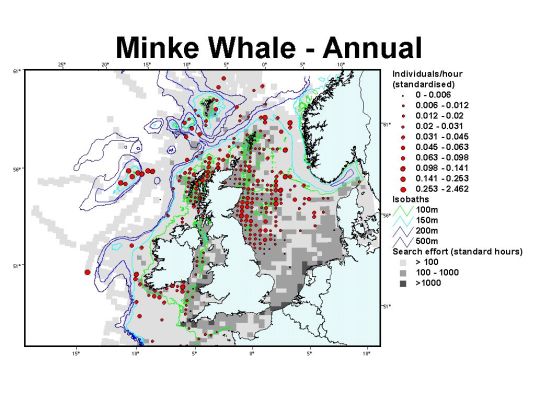

Hull, and other ports of Yorkshire with it, was built on whaling – and not many industries have collapsed harder than whaling. For once, the geography of the land has little impact on this, but the geography of the sea does:

Between England and the European continent is a shallower stretch of sea called Dogger Bank – named for the Dutch cod-fishing boats known as Doggers which fished on it. But shallow water isn’t great for whales. So where is there water good for whales?

Well, whalers from Great Britain would venture as far as the Antarctic ocean in search of whales, and often hunted off Greenland – but there was water closer to home where whales did and still do frequent:

(There is still whaling in the North Sea. Around 500 minke whales are killed by Norwegian whalers each year “in objection to” the global ban on commercial whaling.)

Outside of this, there’s also a divide between port cities dealing primarily in cargo or primarily in passengers, something which is somewhat evening out by one means or another, but here’s a current map of UK passenger ports and their passenger numbers:

Or at least circles sized to correspond to their passenger numbers - source with stats: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sea-passenger-statistics-all-routes-2021/sea-passenger-statistics-all-routes-2021

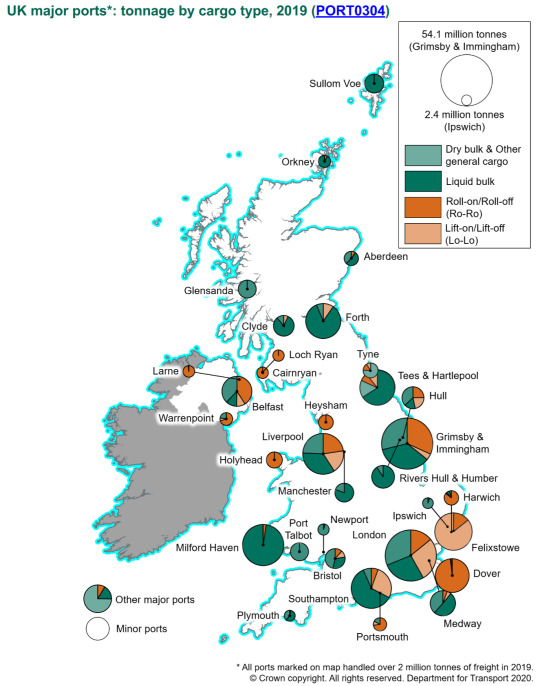

Compare this with a map of cargo ports by load:

Source with numbers: https://safety4sea.com/uk-ports-record-steady-performance-during-2018/

Generally showing passenger numbers getting lower the further you get from Dover, but not the same correlation with cargo (Plymouth and Holyhead both bucking this trend at a glance).

So, if not “The North” and “The South”, what name does make sense for this divide?

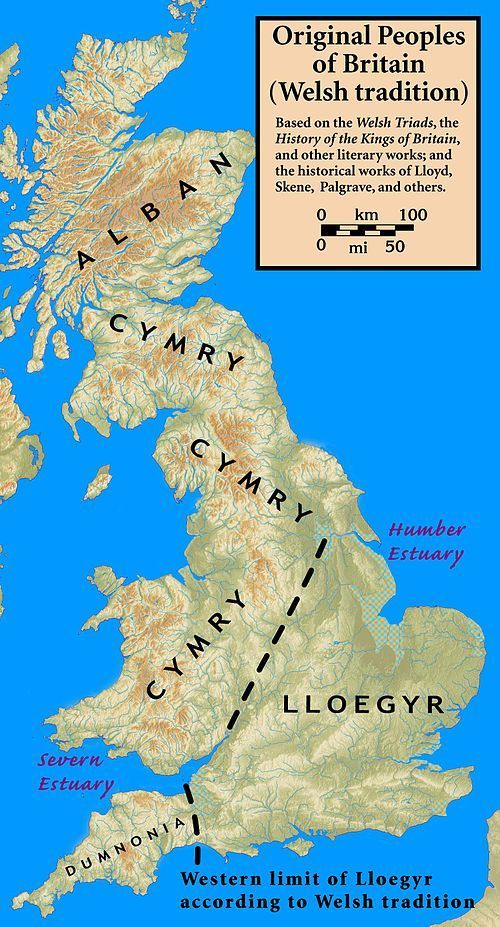

I propose “the South” be known as Lloegyr.

These names still exist: Domnonea still exists in Brittany both as a name for that same region from which Brittonic settlers came to Brittany and an area of Brittany named for them, and in Welsh, yr Alban is Scotland, Cymru is Wales and Lloegr is England.

Wales isn’t part of “the North”. “The North” is part of Wales.

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished watching the 1966 Hammer flick Plague of the Zombies, and I'm fascinated by it. The premise is that the squire of a small Cornish village, who was raised in the Caribbean before being called home to take over after his father's death, has turned to voodoo to try to get workers to reopen the tin mines that made the village's fortune.

The movie sits neatly in an uneasy horror space between the original horror of the zombie - of your will being overridden by another's, of continuing to be enslaved even after death should have released you from all earthly woes - and Romero's ghouls and everything that they spawned. A nightmare sequence features hands pushing up out of fresh-dug graves, dead faces closing in all around one of our protagonists - but in the end, the only person the zombies are truly dangerous to is the man who created them. The true horror of the story is the absolute power that the squire holds over the people of the village, made metaphorical as voodoo.

The tin mines were closed after multiple fatal accidents caused the men of the village to refuse to work there anymore, so the squire removed their ability to refuse by killing and raising them as zombies. At the end of the day, he owns these people, body and soul, and there's nothing that the police or the vicar or anyone else who is supposed to be responsible for the villagers' wellbeing can do, so long as the squire holds this position of absolute power.

If you feel you simply must transplant zombie horror based in voodoo into a white European context, I feel like using it to highlight the injustices of a system of government directly descended from feudalism is not the worst choice you could make.

#the movie itself is solidly middling late sixties-early seventies horror fare#not terrible. not groundbreaking. all the 'nighttime' scenes are very obviously shot in broad daylight#also wondering if gdt saw this one because 'the descendant(s) of a minor english aristocrat who's trying to reopen the abandoned mines >#< that once made their family and their rural community their fortunes resort to murder in a doomed effort to restore their former glory'#is uhhhhhhh also the plot of crimson peak

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, why do people care so much about Cornish identity? Cornwall’s just a part of England right? Another county with some distinct foods and a funny accent, and they moan about the tourists- when they should be grateful for the money.

Except it’s not.

Whilst the rest of England was forming with a character influenced by Germanic and Norse cultures, Cornwall was holding itself separate as an independent Celtic kingdom, with strong links with Wales, Ireland and Brittany- as well as trading with the wider Mediterranean. For a long time, this kingdom included parts of Devon, but eventually the Celtic people were forced back past the Tamar, and at some point started referring to the land as Kernow, rather than Dumnonia (probably).

Even after the Norman conquest, in part because Cornwall came under the control of the Duke of Brittany, Cornwall retained elements of its unique culture, and certainly its language. There are existing works of literature written in the Cornish language (also called Kernewek) during the medieval period. Due to the active tin mining industry and the Stannary courts, they even had a separate legal system.

All of this continued until the start of the Tudor period, when Henry VII, desperate for money for his wars with Scotland, suspended the operation of the Cornish Stannaries, and imposed greater taxes. This ultimately led to the Cornish Rebellion of 1497. An army of as many as 15000 rebels marched towards Somerset, and ultimately to London, where the rebels met with Henry VII’s armies. Unfortunately, the Cornish lost the ensuing battle, and the rebel leaders were captured, killed and quartered, with their quarters being displayed in Cornwall and Devon. From 1497 to 1508, Cornwall was punished with monetary penalties, impoverishing the people, and land was given to the king’s (English) allies.

However, this wasn’t the death of Cornish culture or dreams of independence from England. Until 1548, Glasney college was still producing literature in Cornish- when it was destroyed in the dissolution of the monasteries, during the English reformation. The following year, 1549, the Cornish rose again- this time to demand a prayer book in their own language, which was still the first (and often only) language of most people in the region. The rebellion was also about the ordinary people vs the landowners, as shown by their slogan “kill all the gentlemen”.

Unfortunately, this rebellion failed too, and this time, it wasn’t just the leaders who were killed, but up to 5,500 Cornishmen- which would have been a significant proportion of the adult male population at the time. These factors combined are widely thought to have contributed to the decline of the Cornish language- although it was still widely in use centuries later.

Despite the failings of these rebellions, the Cornish retained a distinct language and their own culture, folklore and festivals. Mining, farming and fishing meant that the region itself wasn’t economically impoverished, as it was today. Even towards the end of the 1700s, there were still people who spoke Cornish fluently as a first language (including Dolly Pentreath, who definitely wasn’t the last Cornish speaker).

However, over time, the tin mines became less profitable, and Cornwall’s economy started to suffer. Especially in the latter part of the 19th century, many Cornish began to emigrate, especially to places like Australia, New Zealand (or Aotearoa), Canada and South America. Cornish miners were skilled, and were able to send pay back home, and along with the Welsh, influenced culture and sport in many of these places. Many mining terms also have their roots in Cornish language and dialect.

Throughout the 20th Century, Cornwall went through an economic decline- to the point where, when the UK was an EU member, Cornwall was receiving funding intended for only the most deprived regions in Europe. It was one of very few places in the UK to receive this funding- due to the levels of poverty and lack of infrastructure.

Part of the decline was also linked to the decline of historic fish stocks, such as mackerel. In the 70s and 80s, there was a mackerel boom- and large fishing trawlers came from as far away as Scandinavia (as well as Scotland and the north of England) to fish in Cornish waters. The traditional way of fishing in Cornwall used small boats and line fishing. The local fishermen couldn’t compete, and ultimately stocks were decimated by the trawlers. Many more families had to give up their traditional way of life. One could draw parallels here with worldwide indigenous struggles over fishing rights.

Despite this, Cornish communities retained their traditional folklore and festivals, many of which are still celebrated to this day. And throughout the 20th Century, efforts were made to preserve the Cornish language. Although there may not be any first language Cornish speakers left, it is now believed that community knowledge of the language was never truly lost.

Cornwall has since become a popular tourist destination. This brings its own problems- many people want to stay in self-catering accommodation and, more recently, air bnbs. This, alongside second homes, has gutted many Cornish communities. The gap between house prices and average wages is one of the largest in the country. Land has become extremely expensive, which hurts already struggling farmers. Roads can’t cope with the level of traffic. The one (1) major hospital can’t cope with the population in the summer. All of last winter, most Cornish households faced a “hosepipe ban” due to lack of water- yet in the summer, campsites and hotels can fill their swimming pools and hot tubs for the benefit of tourists.

Does this benefit Cornwall? Only about 13% of Cornwall’s GDP comes from tourism. The jobs associated with tourism are often poorly paid and may only offer employment for part of the year. People who stay in Air BnBs may not spend that much money in the community, and the money they pay for accommodation often goes to landlords who live upcountry and aren’t Cornish. Many major hotels and caravan sites are also owned by companies that aren’t Cornish, taking money out of the local economy.

Match this with a housing crisis where it’s increasingly difficult to rent properties long term, and buying a flat or house in Cornwall is out of reach of someone on the average salary and it’s easy to see why people are having to leave communities where their family lived for generations. This damages the local culture, and means centuries-old traditions can come under threat.

All of this feeds into the current situation; it feels like middle class families from London see Cornwall as their playground, and moan about tractors on the road, or the lack of services when they visit. People talk about theme park Cornwall- a place that’s built for entertainment of outsiders, not functionality for those who live here. More widely, a lot of people around the UK have never heard of the Cornish language, or view it as something that’s “extinct” or not worth preserving.

The Cornish are one of Britain’s indigenous cultures, alongside Welsh, Gaelic, Scots, Manx and others. And it’s a culture that’s increasingly under threat economically and culturally. We’ve been clinging on to our homes for a long time, and even now it still feels like we might be forced from them (indeed some of us are). So yes, Cornish people can seem excessively defensive about our identity and our culture- but there’s good reason for it!

#uk politics#cornwall#cornish#kernow#kernewek#celtic languages#minority languages#minority cultures#Cornish history#cornish langblr

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who - The Stuff of Legend LIVE!

Paul McGann and India Fisher to star in special one-off live recording of a brand-new Eighth Doctor adventure.

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of licensed Doctor Who audio dramas, Big Finish Theatre, in partnership with BBC Studios, Fourth Wall Live and AEG, is proud to announce a unique full-cast live recording event, taking place at Cadogan Hall, London on Saturday 14 September 2024.

For the very first time, Doctor Who fans will be able to watch an all-star cast take to the stage to perform a brand-new audio play, The Stuff of Legend, by Robert Valentine.

Leading the cast is Paul McGann as the Eighth Doctor and India Fisher as his indomitable companion Charley Pollard. They’ll be joined onstage by Alex Macqueen as the Master alongside Nicholas Briggs, who voices the Doctor’s unstoppable arch-enemy, the Daleks.

Something is afoot in the lonely Cornish village of Merrymaid Bay. Rumours of dead men working in the tin mines have sent a chill through the community, and it's up to the Doctor and Charley to get to the bottom of the mystery.

Can the legends of the Bucca that haunts the mines be true? And just what awesome power do the Doctor’s greatest enemies – the Daleks! – threaten to unleash upon the universe?

Tickets will be available to order at www.doctorwhoaudiolive.com from 10:00 (UK time) on Friday 05 July, with prices beginning at £18.00.

Big Finish executive producer Jason Haigh-Ellery said: “25 years? It feels like 25 seconds! Producing the audio adventures of Doctor Who has been such a joy that two and a half decades has flown by – almost as if we have all been in the time vortex with the Doctor.

“We’ve enjoyed ourselves so much producing thousands of hours of audio drama adventures – and now we have the chance to show fans of the series how the audio productions are made, with a new live performance – the first time Doctor Who has been performed live on stage since 1989.”

Dominic Walker, Global Business Director at BBC Studios, added: “After 25 years of working with Big Finish on the Doctor Who audio adventures, BBC Studios is excited to now be bringing a live version to the stage. The Stuff of Legend is a fitting celebration and I am delighted that fans will be able to witness the recording of such a momentous anniversary story up close and personal.”

Please note: Cadogan Hall has limited capacity so fans are advised to book quickly to avoid disappointment.

Simultaneous to the live stage show, a full-cast studio production of Doctor Who: The Stuff of Legend will be released on 14 September 2024. Big Finish listeners can pre-order this adventure now for just £15.99 (collector’s edition double CD + download) or £12.99 (download only) exclusively here. This will also be available to purchase as a collector’s edition CD at the event.

All the above prices include the special pre-order discount and are subject to change after general release.

Please note that Big Finish is currently operating a digital-first release schedule. The mail-out of collector’s edition CDs may be delayed due to factors beyond our control, but all purchases of this release unlock a digital copy that can be immediately downloaded or played on the Big Finish app from the release date.

#Big Finish#Eighth Doctor#Charley Pollard#The Master#Live Audio Drama recording#Doctor Who#25th anniversary

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

SUMMARY: An American and his daughter arrive in England with the hopes of reviving the tin mining industry. However, when the plan turns to action, falling rocks trap men in a haunted Cornish mine.

#haunters of the deep (1984)#supernatural horror#ghost#survival horror#1980s#united kingdom#european movie#horror#movie#poll

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Devil's Foot

Originally published in 1910 and part of His Last Bow.

Poldhu, which means "black pool" in the Cornish language is located on the Lizard Peninsula, the southernmost tip of Great Britain.

Cornwall has historically been popular for smugglers. Another common pasttime due to the frequency of shipwrecks was "wrecking" i.e. locals taking the cargo from the vessels dashed against the shore, which is legally considered theft. In 2007, a damaged cargo ship was run aground on the Devon coast to avoid an environmental disaster and the locals started looting the cargo, including a bunch of BMW motorbikes. The police eventually closed the beach and told people to contact the Receiver of Wreck - those who did were allowed to keep the bikes or sell them back to BMW for a £3,000 reward.

The Cornish language was pretty much extinct in terms of actual speakers by 1897, but there has been a revival movement since then.

Church of England vicars are generally, but not always, given a stipend instead of a regular wage along with use of the vicarage to live in; they can supplement their income by things like going on satirical news shows (Richard Coles) or writing tales about sentient steam locomotives (Wilbert Awdry).

Helston had a workhouse with an infirmary - it was a hospital until the 1990s. The main Cornwall asylum was in Bodmin and closed in 2002; "going Bodmin" became a local term for going crazy.

Lodgers are not the same as sub-letters, as the latter have exclusive use of part of the property. The former tend to be a lot more acceptable to social housing authorities than the latter.

There was a common belief that traders from Phoenica (mostly modern-day Lebanon) had visited Cornwall, but there is no archaeological evidence to back this up.

Cornwall had a tin-mining industry from c.2000 BC until the last mine closed in 1998; a number of former mines are now museums. The Poldark series of books, along with the TV adaptations, revolve a lot around it. There is now a lithium carbonate mine.

Dr. Sterndale would probably have to wait a couple of weeks for another ship to Africa.

"Cool motive, still murder".

The Ubangi River, a tributary of the Congo, today forms part of border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo with the Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic.

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I'm an English peasant during the Wars of the Roses, do I know that the Yorks and Lancasters are fighting (before they pillage my farm) and why?

Surprisingly, yes!

The lower classes were actually mobilized a fair bit during the political and military struggles between York and Lancaster:

the Kingmaker's popularity with the City of London due to his (frankly criminal) actions as the Captain of Calais had major political and military implications. It led to Suffolk's death in 1450, it prevented Margaret from holding pro-Lancastrian Parliaments in London, and when the real fighting started, Margaret had significant trouble controlling the capital.

Similarly, one of Edward IV's main political strengths was his enormous popularity among the commons of London, which allowed him to easily proclaim himself as King after Mortimer's Cross, and then again in returning from exile.

Jack Cade's rebellion in 1450 was a clear Yorkist/anti-Lancastrian effort to the point where it probably had some Yorkist backing behind the scenes.

The Kingmaker was really good at organizing peasant rebellions against his enemies: Robin of Redesdale's (also known as "Robin Mend-all") Rebellion of 1469 was a rebellion against Edward IV that used the imagery of Robin Hood to stir people up against taxes and "abuses of power," but was led by retainers of Richard Neville, and the Lincolnshire Rebellion of 1470 was sponsored by the Kingmaker and George of Clarence against Edward IV.

On the other hand, Robin of Holderness' rebellion in 1469 was a pro-Lancastrian rebellion against a "corn tax" (i.e, a tax on grain) and in favor of restoring the Percy family (one of the most powerful Lancastrian Houses and mortal enemies of the Nevilles) to the Earldom of Northumberland.

Finally, you have the Cornish Rebellions of 1497, which combined economic motivations (Henry VII has raised taxes for a war against Scotland, and had damaged Cornwall's economy by banning tin-mining) with support for Perkin Warbeck, the impostor Richard of York who tried to overthrow Henry Tudor.

So yeah, English peasants had Views on the Wars of the Roses, often depending on whether they came from the North or the South.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm… Cornish Western story… hm

#OKAY BUT THIS HAS SOME HISTORICAL VALIDATION#bc okay. in the 1830s there was this MASSIVE Cornish emigration#Cornish tin and copper was drying up and the mining business overall in the uk was coming to its heat death#so boom. no more work for a VAST MAJORITY of Cornish folk#so a lot went to South and Cebtral America and a lot went into the US west and Midwest#because westward expansion was also happening (fuck) and so hey#there’s more work out west and in the Americas#just grass valley Cal. was 3/4 Cornish by descent by 1911#so there was a huge Cornish diaspora group in the American west#there were tons of places labelled as “’little Cornwalls’ all throughout the west#and in mexico too!! real de monte!#that’s the only place I can think of atm that retained the status#now clearly there’s way more nuance to it and a far more complex history#especially when talking abt Manifest Destiny and the suchlike#ik that Cornish miners were being PAID to leave Cornwall for Australia to work but I can’t find anything about anything like that happening#re: immigration to america. it’s an incredibly fascinating history bc it did help out the Cornish economy in ways#still quite a few men went over and sent money back to their families#but anyways. to bastardise an entire period in history#cornish western#(multigenerational story? classic revenge ie escaping a past?)#I should be banned from thinking I don’t do anything good with this ability#its actually an idea I’ve had for a while but only in vague shapes#I just think Cornwall is pretty and I’m deep in its history. I also think the American west is pretty and I’m fascinated by ITS history#kicking a tin can around in my brain with my hands in my pockets#anyways

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pendennis Castle (and friends)

I feel like I've been adopted by the spirit of Pendennis Castle. (Perhaps I lived there, in a former life, firing cannons for King Henry?)

Point being, the very first time I caught the Riviera Sleeper to Cornwall in 2017, the diesel loco that pulled the train was Pendennis Castle - and ever since then, the name keeps. Coming. Up. So I think I have slightly adopted it.

This holiday, I went to Falmouth and explored Pendennis Castle itself (“Castle On The Hill Castle”, haha). But more excitingly, look what I encountered in Didcot!

Pendennis Castle! (And holy moly she is a big beastie. And constantly LOUD, her chimney roaring away like a massive kettle you forgot to take off the boil.)

Granted, standing on the station next to her, she's obviously huge - I was STILL not as tall as her. But it’s only when you’re at ground level right alongside, staring up at at this towering piece of noisy engineering and realising that the top of your head doesn’t even come to the top of its wheel, that you realise what absolutely monumental vehicles these actually were. I had to stand on tiptoe to look into her cab.

She's at the coal stage here (above), about to have her tender refilled. The camera was on my eyeline. Even in these photos you can't really grasp how thunderingly enormous this old lady is. 120 tonnes! And even when she was not doing anything at all (her crew weren't even aboard), she was noisy.

Here's an even bigger one! This is King Edward II, who escaped the scrapyard by about 30 minutes and (I think) was in such a state it took longer to restore than it was in service. (I asked the tour guide and it's slightly shorter than the Flying Scotsman but heavier, at 135 tonnes, and more powerful. Apparently there was a bit of a pissing competition between GWR and LNER over who had the better engine, which resulted in these behemoths being designed. They had to do lots of weird things with it because otherwise it wouldn't have fitted through tunnels/alongside platforms/etc.)

Yeah. These are big beasts. (Even the dinky little tank engine they had outside weighed in at almost 23 tonnes.) If I get anywhere with this thing I'm noodling away at, I really want to try and carry that off.

It's quite sad, in a way, seeing them preserved and just sitting there - getting lots of love and polish, granted, but I wanted to see them escape onto the mainline and really run. Watching Pendennis Castle shuffle up and down her 750m of line was a bit like watching a racehorse pace around in a paddock.

Of course I was busy taking notes. (I didn't quite get brave enough to ask the volunteers "so if you were in the middle of nowhere, just an engine and crew, and you'd stopped for some reason, and the driver then had a heart attack, how would you get help?")

(Something something someone runs down the tracks to a lineside phone to call the signalmen to put a stop on the line, and the engine sits whistling the hell out of an SOS because he's not quite got the steam pressure back up to run, until a policeman comes along to help.)

In a final turn for the weird, this holiday, I was just getting ready to leave my hotel on the final day, and heard the toot of a steam train. That can't be a steam train, I said, it's a mainline railway station next door. But I hurried away anyway, and look what was sat in Bristol Temple Meads station! (I left the people in for scale. Even here, the loco is lighter than Pendennis - 72 tons vs 81 tons.)

She left literally not even a minute after I got to the platform, so that was a huge touch of luck. It's a special one-off service running on the mainline up to Shrewsbury. So this is on my list for next year!

(If there isn't already a character in TTTE called Dennis, WELL THERE SHOULD BE. Who used to work the tin mines and speaks Cornish so no-one fucking understands him.)

(The sleeper is my favourite way to travel on holiday. Go to sleep in London, wake up 250 miles away in Penzance!)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moving on.

(7th Sept 2024)

“Kernow Bys Vyken” is something I could say with my whole chest. It means “Cornwall Eternally” in Kernewek, the language of the Cornish people. I am Cornish. I was born here, and I come from a Long line of Cornish Farmers, Miners and Labourers. I speak very little of the language, but the phonetics of it creep through in the way I speak. My generic Southern English accent (which, for those who are not from the UK, is the one you hear in most Non-British media) is often tinged with the same roughness and rhoticity that makes my Grandfather unintelligible to non-native speakers. I take pride in it. I take pride in my celtic heritage and I reject the label of English to pay homage to my colonised forefathers and the nation they lost.

That being said, Kernow is a shit hole. This small part right at the end of the British Mainland Is known for it’s picturesque scenery. Abandoned wheelhouses from our tin mining days stand triumphantly on grassy knolls and tell stories of our past as an exporter of precious metals and agriculture. Our beaches are unique, nestled in between rugged cliff faces or at the mouths of Rivers that built towns in their stead. It’s a place to relax. To feel connected to the earth. To marvel at what nature has to offer in its rawest form and to appreciate the ways it has provided for us. This is code for: Our economy is now built on tourism. Our mines are visitor attractions. Our cliff sides are caravan parks. We’re rammed with English tourists in the summer who have no respect for our beaches or our countryside or the people who live and work here. To them, Cornwall is a Holiday spot. One big play park. A gentrified, miserable play park with no money to provide infrastructure that could possibly support its residents. Many venues close their doors for the bitter winter months, and we Cornish people are left floundering with fuckall to do and a nasty headcold.

I’d be the last to admit my life has not been particularly easy. But, it hasn’t. I grew up Dirt poor to an abusive father and a teen mother who had to learn to grow up alongside her children. There’s a wall decoration in my kitchen, placed by my mother with love. It reads “This Home is a Happy Place” in thick black letters. I can’t say that’s true. Home holds weight to me. It’s not just the place but also everything I experienced here. Home is not just my culture but how I exist within it. I was groomed here. I had my first kiss here. I was thrown across a room by my father here. I met my best friends here. I remember the way the carpet in my primary school felt under my trainers. I remember the smell of seawater on Lemon Quay as the tide came in and the boats rose with it in my Port Hometown. I remember spending time at Crantock beach in the early hours of that whole summer that felt like a day, and nursing my blistering sunburn and developing scarring and freckles on my shoulders and upper back that I still have to this day. I remember the way my mother smacked me across the back of the head with a smug grin on her face, and I remember the way my own face crumpled into tears because she was supposed to be the safe one. I remember how much I longed to exit my childhood when I was in it, thinking i’d be in control when I was a grown up, and that feeling echoes in my grown up heart now, the heart of a man who has no control and mourns for a childhood he never had.

The end result of this is not me returning to the sun-lit glow of a childhood that was not mine to miss, but rather me in a place that I do not recognize. A place where the signs do not have their Kernewek translations proudly stated underneath. A place where the water is dirty and contaminated with industrialism. A place where my father cannot reach me with his violent hands. A place where no one knows my old name. A place where I can live by my own rules, as my own man, emboldened and unafraid, but at the forfeit of every bit of comfort. Everything I knew to be true.

But that’s the letting go. Cornwall is a Sinking ship, and I am not its captain. I can love it. I can mourn the idea of it, and I can understand when It’s time to move on. I can make peace with the fact that I will never be a child again. And I can grieve for the person I may have been if I was not weighed down by the immense burden of my trauma. Time is fleeting, and my past is so much pain. I have to keep moving, onward and onward. Go where my instincts take me and remember my home with pride, knowing full well that this will never be my home again. It’s all I can do.

Kernow bys Vyken

#cornwall#kernow#kernewek#kernow bys vyken#essay#personal essay#writing#creative writing#moving on#letting go

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nanscough: A Gothic Scarlet Hollow AU

Nanscough (Cornish: Scarlet Valley) is a village and civil parish in Cornwall. The local tin mine, owned by the prominent Cough (pronounced ko) family, was once prosperous and drew many to the area. A few Afro-Caribbean families even settled in Nanscough a century ago and are now assimilated into local life. But the tin trade began to decline earlier in the century following a collapse in Nanscough Mines, and the town’s fortunes fell along with it. The parish is also home to the Seven Maids, local megaliths said to be a group of girls turned to stone for dancing on the Sabbath. Lately the area has been plagued by reports of creatures from Cornish lore – giants, pixies, Tommyknockers, phantom cats, and even the Devil’s Dandy Dogs. Nanscough will not give up its secrets easily….

Mr./Miss/Mx. MC Cough: MC grew up in genteel poverty with their mother, the late Vivian Cough, who fled her ancestral home under mysterious circumstances. They are visiting Nanscough for the first time in their life to attend the funeral of their aunt, Mrs. Anne Cough.

Miss Tabitha Cough: Iron-fisted manager of Nanscough Mines and mistress of Nanscough Hall. Cousin to MC.

Dustin: A badger living in a dresser in the Hall. Son to Dustin Mam. Speaks broken English with a strong Cornish accent.

Dustin Mam: Another badger living in a dresser in the Hall. Mother of Dustin. Also speaks broken English with a strong Cornish accent.

Frou-Frou: Nanscough Hall cat. Speaks with a French accent.

Miss Stella Trelawney: Former lady’s companion to Miss Cough, current lady reporter investigating stories of the Devil’s Dandy Dogs. Owner of Gretchen. Friend to Cora and Rhys.

Gretchen: Stella’s lapdog. Speaks the Queen’s English.

Miss Cora Forsyth: Afro-Caribbean shopkeeper, aspiring naturalist, and lover of Gothic tales and penny dreadfuls. Friend to Stella and Rhys. Sister of Miles and daughter of Sybil.

Mrs. Sybil Forsyth: Town midwife, herbalist, and shop owner. Mother to Cora and Miles. A fixture of Nanscough.

Master Miles Forsyth: Indifferent Afro-Caribbean youth. Lover of boy’s adventure tales and little else. Son of Sybil and brother of Cora.

Mx. Avery Bell: Afro-Caribbean barkeep at the Bell, Nanscough’s only public house. Nibling to Winifred. Liked by all, but close to no one.

Mrs. Winifred Bell: Widowed Afro-Caribbean landlady of the Bell. Aunt to Avery. Makes the best pasties. Another town fixture.

Mr. “Duke” Calloway: Local farmer. Claims to be descended from British royalty, hence the nickname. Father to Beau. Distant cousin to Julius.

Mr. Beau Calloway: Local farmer. Large adult son to Duke. Distant cousin to Julius.

Mr. Julius Tremaine: Local farmer. Scoffs at his family’s claim to royal blood. Distant cousin to Duke and Beau.

The Miners: Come from all over Cornwall and even parts beyond.

Mr. Oscar Gutierrez: British-born Spaniard schoolmaster. Father to Rosalina.

Miss Rosalina Gutierrez: British-born Spaniard girl. Daughter to Oscar. Friend to Alexis, Miles, Rebecca, and Zane.

Morsel: The Gutierrez’s cat. Speaks broken English.

Sheriff Hammet: Affable town sheriff. Suitor of the Widow Bell.

Deputy Teague: Overly-serious sheriff’s deputy. Owner of the Lord Mayor.

Deputy Penrose: Calm sheriff’s deputy. Takes ninepins far too seriously.

Jimmy: Deputy Teague’s dog. Affectionately known as the Lord Mayor. Speaks with a slight accent.

Scraps and Daisy: Local dogs and leaders of the Dog Militia. Speak with accents.

Vicar Daniel: Local vicar with sparsely attended sermons. Strange and off-putting. Husband to Mrs. Jane, father to Flora.

Mrs. Jane: Vicar Daniel’s wife, mother of Flora, keeper of sheep. Forces weekly social calls on Tabitha.

Miss Flora: Daughter of Vicar Daniel and Mrs. Jane. Claims to have befriended pixies at the Seven Maids.

Dr. Joan Kelly: One of Britain’s first female licensed doctors. Formerly of London by way of Ireland. Claims to be the widow of a sea captain who died during a transatlantic voyage. Mother to Rhys.

Mr. Rhys Kelly: “Consumptive” artist. Bought to Cornwall by his doctor mother to “recover his strength” in country air. Extremely Byronic. Son to Dr. Kelly. Friend to Stella and Cora.

The other youths: Miss Rebecca, Miss Alexis, Master Zane. Friends to Miles and Rosalina. Probably up to no good.

Mrs. Nancy: An ill-tempered and entitled miner’s wife. Mother to Miss Rebecca.

Mr. Samuel Wayne: Nanscough Hall groundskeeper, currently neglecting his duties. Probably not the host of an inhuman consciousness.

#Scarlet Hollow#Alternate Universe#Scarlet Hollow Characters#I skipped some of the animals and all of the dead people#Let me know if I missed anybody important#Gothic AU#Victorian AU

44 notes

·

View notes