#Cordwainer Bird

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

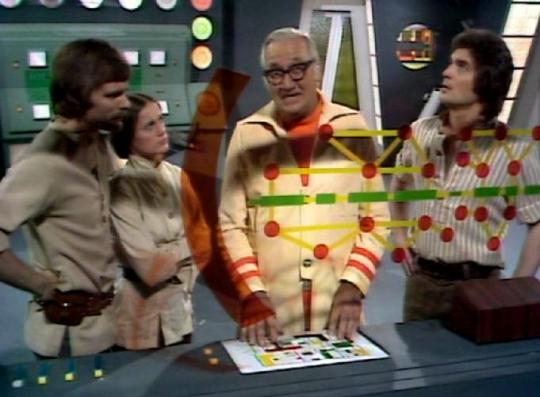

This was one of the first TV shows I ever watched and paid attention to. I was 4 years old. The story behind the making of this show is quite fascinating. Phoenix Without Ashes was actually a novelization of the show's first episode. Harlan Ellison was so displeased at how the show was handled (originally planned as a state-of-the-art production it ended up being filmed in a TV studio next to the news desks on a budget that made Doctor Who look like Avatar) he had his name replaced with Cordwainer Bird. Ben Bova, wrote a spoof on what happened with The Starlost's production as the novel, Starcrossed.

Has anyone else seen this 1973 Canadian Sci Fi TV show, The Starlost?

It was a super low budget adaptation of of Harlan Ellison's book, Phoenix Without Ashes - a story about a huge generation ship on its way to colonize a planet, and society on it collapses back to a primitive state and each section of the ship is like a different tribe. Meanwhile the ship malfunctions from lack of care and the engines are offline and it's drifting into a star.

I was like 9 when this came out, and totally oblivious to the abysmal quality of the production, I was just so fascinated with the concepts here. It might be partly responsible for getting me into Sci Fi. (Lost in Space and Star Trek were big reasons tho too..)

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Serve Them All My Days - BBC One - October 17, 1980 - Januiary 16, 1981

Drama (13 Episodes)

Running Time: 60 minutes

Stars:

John Duttine as David Powlett-Jones

Frank Middlemass as Algy Herries

Alan MacNaughtan as Howarth

Patricia Lawrence as Ellie Herries

Neil Stacy as Carter

Susan Jameson as Christine Forster

Charles Kay as Alcock

Kim Braden as Julia

John Welsh as Cordwainer

Cyril Luckham as Sir Rufus Creighton

Simon Gipps-Kent as Chad Boyer

Belinda Lang as Beth

Nicholas Lyndhurst as Dobson

David King as Barnaby

Phillip Joseph as Emrys Powlett-Jones

Michael Turner as Brigadier Cooper

Norman Bird as Alderman Blunt

#To Serve Them All My Days#TV#BBC One#Drama#1980's#John Duttine#Frank Middlemass#Alan McNaughtan#Patricia Lawrence#Neil Stacy#John Walsh

1 note

·

View note

Text

Contemplating if it's worth tryomh to get my name on a short story switched to Cordwainer Bird.

0 notes

Photo

Earth ship Ark, man’s greatest and final achievement. Out of control, drifting through deep space over 800 years into the far future. Its passengers, descendants of the last survivors of the dead planet Earth, locked in separate worlds, their destination long forgotten. Heading for destruction unless three young people can save The Starlost.

The Starlost (1973)

#The Starlost#1970s#1973#science fiction#Keir Dullea#Cordwainer Bird#Douglas Trumbull#Gay Rowan#Robin Ward#Title Card#Danny watches The Starlost#Nothing but the most recent scifi over here!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are you sure it's not the voice actress from Dexter's Laboratory who voiced Dee Dee?

Another possibility is Allison Moore, the LA-based playwright and TV writer. (There is also an Allison Moore playwright based in Minneapolis, but I think this person is less likely.)

Otherwise, maybe this is an analog to Alan Smithee, a pseudonym used by directors when they worked on a project, but it went so sour that they no longer want their name connected to it.

Apparently Harlan Ellison used "Cordwainer Bird" on projects he no longer wanted to be associated with.

Who Is Allison Moore?: A Disney's Wish Mystery

OK, this is a little off the rails and random but this has been driving me crazy since I looked into it last night.

So, Disney's 100th Anniversary movie Wish is coming out soon and people have had a lot of hot takes about it so I wanted to do some digging. As part of that, I looked at the writers and two people have a "Screenplay by" credit: Jennifer Lee and Allison Moore.

Jennifer Lee, of course, wrote Frozen--their biggest princess hit in the modern era so that makes total sense to me. If you're coming out with a new princess movie for the big centennial of course you'd tap her. But I'd never heard of Allison, and when you look at her name on Wikipedia:

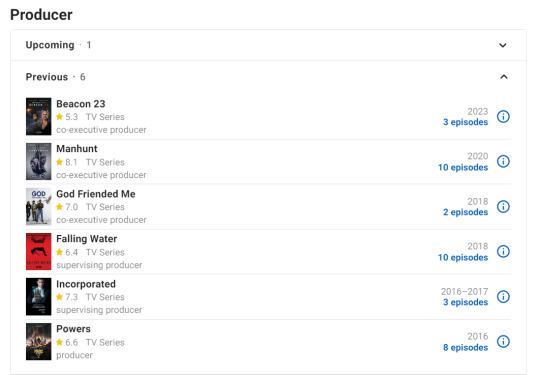

No blue link. So I headed to IMDB to check out her credits, figuring maybe she was some hot new talent recently promoted from within who did storyboards on some recent projects like Moana or something. But when I went to her IMDB page, this is what I found (after a brief mix-up with a Dexter's Lab actress):

Her Producer credits come up first and...huh. That's a lot of adult live action TV projects. Well, maybe her Writing credits are where this starts to make sense:

What? That can't be right, can it? The only vaguely Disney-esque thing on that credit list is Beauty and the Beast and, to be clear, that is a CW reboot of a 1987 procedural with the logline, "A beautiful detective falls in love with an ex-soldier who goes into hiding from the secret government organization that turned him into a mechanically charged beast." And she wrote two episodes on it.

And look at Disney's official page about Wish!

Everyone else on this page has credits that make sense--Frozen, Frozen 2, Raya, Encanto. And the two credits they list for Allison?

Night Sky and Manhunt.

Night Sky, an Amazon Prime show that she wrote one episode for and was cancelled after one season. And Manhunt--and show about hunting the UNABOMBER--that ran for two seasons and that she wrote two episodes for. Those are her two credits that they put up there next to Frozen and Encanto.

I have been scouring the internet trying to figure out who this woman is and how she got this job and I have come up *empty*. This is the big 100th anniversary movie! Why would they have one of the two screenplay writers be someone who seemingly has never done something like this before??? Like, I understand that not having done something before doesn't mean you can't do a good job, but it usually means you don't get the keys to the biggest most anticipated projects in the company's history!

They presumably could have gotten anyone they wanted for this and they picked this person and I have zero clue why and it's driving me crazy. If anyone has ANY information that could illuminate this at ALL--an interview, a social media post, gossip from your cousin who's a gofer at Disney--please let me know because I feel like I'm going full Pepe Silvia over this.

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ellison’s Law

Even for the early 1960s, Burke’s Law was a silly gimmick show.

The gimmick? Millionaire Amos Burke, despite inheriting fabulous wealth, always wanted to be a detective so he joined the LAPD and worked his way up to captain of the homicide bureau.

Basically Batman without the trauma or costume.

And like Batman of a few years later, an exercise in camp.

The show was rigidly formulaic, but for practical reasons. It relied heavily on stunt casting celebrities as suspects or witnesses and as such it had to be flexible enough to handle rewrites and re-castings in the middle of production.

The typical episode began with someone found murdered or shown getting killed in some unusual manner, cut to Amos Burke flirting with a lady only to be called away by his police duties. Cue the opening title as Burke and his driver hurry out of his relatively modest Beverly Hills mansion to his Rolls-Royce (actually producer Aaron Spelling’s car which he rented back to the production) as a sultry female voice incants: “It’s Burke’s Law” then after the first commercial break Burke arrives at the scene of the crime and finds clues pointing him to four or five suspects.

Said suspects are the celebrity guest stars, recruited either to give them some manic scenery chewing time or -- more rarely -- an intense dramatic scene.

After three more commercial breaks, Burke intones one of his “laws” (“Burke’s law: Never ask a question where you don’t already know the answer.”), pulls a rabbit out of his hat / solution out of his butt, and fingers that episode’s duly appointed murderer.

The problem with the series as a whole is that it could never quite decide on what tone it wanted to take and stick with it consistently. The British series The Avengers found the perfect balance of tongue-in-cheek / derring-do but Burke’s Law bounced all over the spectrum, frequently in the same episode.

So why bring up this mediocre TV show at all?

Two words: Harlan Ellison

. . .

I’ve posted many times before on Harlan’s career and the impact of his writing and friendship on me.

He was in the mid 1960s at his zenith as a TV writer, and while his writing career as a whole encompasses so much more than that, his brief run as one of the meteors streaking across the Hollywood sky only lasted 4 years.

Oh, he kept writing for TV after that, but the old zing was gone. He supplied stories for other series, created and fought hard to keep The Starlost on track but eventually had to walk away from that heartbreak, adapted several of his own short stories to a Twilight Zone revival, as well as numerous development deals that went nowhere (including two great ideas for The Name Of The Game, another Gene Barry series, that would have fit perfectly into that show’s oeuvre).

If you find his second book of TV criticism, The Other Glass Teat, check out his first draft for “The Whimper Of Whipped Dogs” episode of The Young Lawyers (not to be confused with his short story of the same title).

It’s one of the most powerful / gut wrenching things you’ll ever read…

…but by the time the studio and the network got through with it, the final product was virtually unrecognizable…and unwatchable.

Such was Harlan’s fate after 1967 in Clown Town (as he referred to it).

But from 1963 to 1967, he was golden.

. . .

Harlan’s rocky personal history went through many highs and lows before coming to Hollywood in 1962.

Harlan’s first breakthrough as a writer was with his series of stories and essays on juvenile crime in New York in the early and mid-1950s..

Drafted in 1957. following his discharge, he settled in Chicago with his second wife and her son, editing Rogue magazine, a Playboy imitator.

Feeling his personal life becoming untenable, he called in favors from a friend, drove out to California with his soon-to-be ex-wife and stepson (aware the marriage was over, she also wanted to relocate away from Chicago), made his first sale to TV (his short story “No Fourth Commandment” to the TV show Route 66), then briefly found a sweet spot with Burke’s Law, writing four teleplays for their first season.

Burke’s Law is a good crucible for examination because of its silly, gimmicky nature and rigid format requirements.

These scripts represent a pivotal point in Harlan’s writing career, but more importantly, they mark the only sustained run he enjoyed on a non-anthology show, and as such make a good benchmark in comparing his growth as a writer and how his unique perspective played out in in relation to the constraints of episodic television.

While a couple of Harlan’s better science fiction / fantasy stories were written before 1963, the meteoric rise of his career in those genres began with his classic short story “’Repent, Harlequin!’ Said The Ticktockman” in 1965, followed by a host of other groundbreaking short stories and novellas, and his original anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions in which he recruited other science fiction and fantasy writers -- many of them already well established pros -- to follow the path he blazed in the genre.

His experience on Burke’s Law occurs squarely between what he once was to what he was becoming, and as such is worthy of attention.

SPOILER: There are no great hidden gems here.

There’s a lot of amusing writing, and a few flashes of the emotional intensity Harlan could provide, but by and large this is journeyman level stuff: Better than most, but not the best.

. . .

”Who Killed Alex Debbs?” was his first script for the series, and he pitched it to producer Aaron Spelling at a cattle call after a screening of the show’s pilot episode.

Harlan jump started the pitch process by improvising an idea off the cuff at the end of the screening, and Spelling took him to his office to hear how Harlan planned to resolve it, then hired him on the spot.

It’s unclear if Harlan was actually a staff writer on the series or simply hung out at the studio a lot, but he used his skills as a quick study to start working his way up the food chain.

His first script fulfills all the requirements of a Burke’s Law episode and shows off two of Harlan’s main strengths: An ability to hone in on intense emotion and a keen eye for the culture around him (in this case, very specifically Hollywood of the early 1960s).

On the downside, logic gaps render this story more implausible than most -- and as noted, Burke’s Law as a series wasn’t famous for its plausibility.

A flaw of almost all Burke’s Law episodes is that the victim is typically found dead under mysterious / bizarre circumstances, and the impression we get of them is constructed entirely through the words of suspects and witnesses.

It’s not an unworkable approach, but not the best suited for episodic television.

In this instance. victim Alex Drebbs is a Hugh Hefner-like men’s magazine publisher and monarch of a mini-empire of key clubs ala the Playboy Clubs of the era. Harlan captures that milieu well but here’s where the logic gaps hit hard: There’s no way a Hefner-like figure would be alone long enough for someone to kill him without being noticed, there’s no way his disappearance wouldn’t be immediately noticed by employees needing his attention, and it sure as hell wouldn’t have happened in a deserted club on the afternoon of its big opening.

On the plus side, there are some great character scenes including Arlene Dahl as a bitter ex-investor in Debbs empire now reduced to licking saving stamps to keep her decay mansion in repair, Burgess Meredith as a men’s magazine cartoonist who is nothing but a bundle of neurotic twitches and tics, and finally Sammy Davis Jr as Cordwainer Bird, the humor editor for Debbs’ magazine.

This was at the Robin Williams stage of Davis career, when all you had to do was point a camera in his direction and let him go. Harlan supplied the corny gags but Davis launched them over the top with his antics, and while he brings the proceedings to a complete disruptive halt, his brief scene is the most entertaining in the entire series. (Harlan later used Cordwainer Bird as his WGA pseudonym when he wanted to indicate displeasure at what had been done to his scripts.)

By his own account, Harlan had less luck with Diana Dors -- “the British Marilyn Monroe” -- and treated her condescendingly during the shoot. (By comparison, William Goldman in his memoir Adventures In The Screen Trade shows a much more sanguine / roll-with-the-punches attitude, and that might explain part of the reason his screenwriting trajectory was far different than Harlan’s.)

All in all, an uneven example of both the series and Harlan’s abilities.

. . .

”Who Killed Purity Mather?” was Harlan’s second script for the series and one of the few that played with the rigid format of the series insofar as the victim is seen alive for a few moments before being killed in a rather sadistic and spectacular manner (splashed with acid then trapped in a burning house, and the high angle shot used to show her demise must have been incredibly risky -- and thus costly -- to film).

It also drops a very subtle clue that I’ll reveal in the footnote.*

This is Harlan going so far over the top he emerges on the other side. Plotwise it features more logic gaps than his first script, but the whole thing is so silly it’s pointless to complain about it.

Purity Mather is a professional witch (!) who speeds up the investigation into her own demise by mailing Amos Burke a recording saying she’ll be killed along with a list of five possible suspects (that she doesn’t mention them by name in the recording reflects the show’s desire for standalone scenes, enabling them to recast and rewrite plotlines more easily; the scene where Burke reads the names to his team was doubtlessly shot after the guest cast was locked in).

Burke & co. start shaking down suspects, including Telly Savalas as Fakir George O'Shea, a Muslim holy man / cosmetics chemist (!!); Charlie Ruggles as I. A. Bugg, an eccentric elderly millionaire who likes to chase -- but not catch -- prostitutes around his apartment while dressed in lederhosen(!!!); Wally Cox as Count Carlo Szipesti, vampire for hire (!!!!); and Gloria Swanson as Venus Hekate Walsh a fright wig bedecked self-proclaimed goddess of free love (!!!!!).

The episode might as well have had a laugh track. It’s amusing with several daft touches only Harlan could provide, but the daftness comes from his take on Hollywood culture of the time.

I’d go so far as to say elements of Cox and Swanson’s characters were based on real life people living in and around Hollywood at the time, in particular some science fiction fans Harlan had come in contact with.

It’s a romp but a disappointing one. The logic gaps are too big in this one (case in point, if you’re the captain of the homicide bureau and you come home to see a masked figure climbing out of your second story window in broad daylight, you don’t simply shrug and let them run off) and the ending is one of those annoying ah-yes-now-that-you-caught-me-I-will-admit-everything-even-stuff-you-don’t-know cappers that Joe Ruby and Ken Spears would have rejected for Scooby Doo.

In short, a script whose parts are better than the whole.

. . .

”Who Killed Andy Zygmunt?" is another slight story that pays off with an insight into Hollywood pop culture of the era. The victim is “a pop artist” (no, he’s not; he an assemblage sculptor) impaled on his own artwork.

He’s also revealed to be an extortionist who acquires embarrassing evidence that he affixes to his assemblages then blackmails his victims into buying the art to keep their secrets safe.

Once again Burke is conveniently handed a list of suspects, in this case the people who bought the last five pieces of art from the exhibit.

This is one of the few times the series had more than one suspect in the same scene as there’s a big gathering in Burke’s office midway through the story (it also includes Michael Fox, a semi-regular on the series playing the coroner, so it represents a pretty sizeable filming day for the show). The suspects include Macdonald Carey as Burl Mason, the star of a popular TV detective show (Harlan gives his scenes what we would now call a meta-fiction touch by playing off Barry’s fictional TV detective dealing with a fictional fictional TV detective); Jack Weston as Silly McCree, a kid’s show host who destroys his career with an on air anti-child rant; Ann Blyth as Deirdre DeMara, a rival “pop artist” who creates her art by spraying women with paint and having them roll around on giant canvases (a gimmick later used in the bizarre 1966 Ann-Margaret comedy The Swinger); Aldo Ray as Mister Harold, former pro-wrestler turned poodle groomer; and Tab Hunter in a surprisingly well done scene as a sky diving playboy.

Hunter’s scene in particular shows Harlan getting his hyperbole under control, much more laconic and evocative than other characters he wrote for the series. As mentioned above, Burke’s Law occurs just on the cusp of Harlan’s huge success in print; he’s beginning to harness the lessons learned to maximum effect. (He would have some setbacks, too, in his screenwriting career, and to be honest part of that can be attributed to his failure to consistently apply the lessons learned, part of it can be attributed to his reputation preceding him, and part of it can be attributed to just bad luck.)

The motives this time are fairly edgy for a 1963 TV series, and combined with the slices of Los Angeles life Harlan provides give a fair example of the cultural zeitgeist of the era.

. . .

”Who Killed ½ Of Glory Lee?” can be explained as Benjamin Glory, half owner of Glory Lee Fashions, with Gisele MacKenzie as the other half, Keekee Lee.

After breaking the budget with his spectacular demise of Purity Mather, Harlan staged this murder as an inexpensive off camera elevator plunge.

This time the plot is a wee bit more plausible, with control of a profitable business being the apparent motive for the murder.

But Harlan loaded up this episode with a more powerful emotional punch than most of his others, and while the dénouement may feel a bit farfetched, it certainly rings true emotionally.

He certainly gave Nina Foch and Anne Helm plenty to work with regarding their characters’ complicated mother / daughter relationship, yet at the same time found room for a playful scene in which Buster Keaton pantomimes his answers to Burke’s questions.

Yet at the same time one senses an impatience behind the keyboard. The opening scene has a squad of female elevator operators (yes, once upon a time there needed to be somebody in the elevator to push the buttons for you) discussing pop culture references of a generation before -- Harlan’s generation.

And while the key emotional conflicts are played out well, several of the other scenes feel rather perfunctory…yet at the same time this is probably the most cohesive whole of any Burke’s Law script, whether written by Harlan or not.

It’s as if after a brief but profitable run on a network series, Harlan realized he’d absorbed as much of the practical end of the business as he could and his next moves should be into broader, edgier territory.

© Buzz Dixon

* SPOILER: Purity Mather is the murderer; she connives a career nudist (!!!!!!) to participate in a magic ceremony then disfigures and kills her, leaving evidence that she hopes will convince the police the body is hers. The subtle clue Harlan drops is the victim, wearing a long black negligee, complaining about how she doesn’t like the feel of the clothes. A nice touch, but undercut by Purity then going to the nudist camp her victim operates and waiting in the buff by the front gate for the police to show up and question the career nudist -- whom Purity has mentioned as a suspect in her faked murder. While it works insofar as Purity doesn’t try to pass herself off to anyone else at the camp as the career nudist, it doesn’t scan that she would know when the police would come to investigate or if they could be easily convinced at the gate and not come in to question other patrons.

#Burke's Law#Harlan Ellison#Aaron Spelling#Gisele MacKenzie#Buster Keaton#Nina Foch#Also Ray#Tab Hunter#Ann Blyth#Macdonald Carey#Jack Weston#Telly Savala#Carlie Ruggles#Wally Cox#Gloria Swanson#Sammy Davis Jr#Cordwainer Bird#Burgess Meredith#Arlene Dahl#writing#screenwriting#television

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

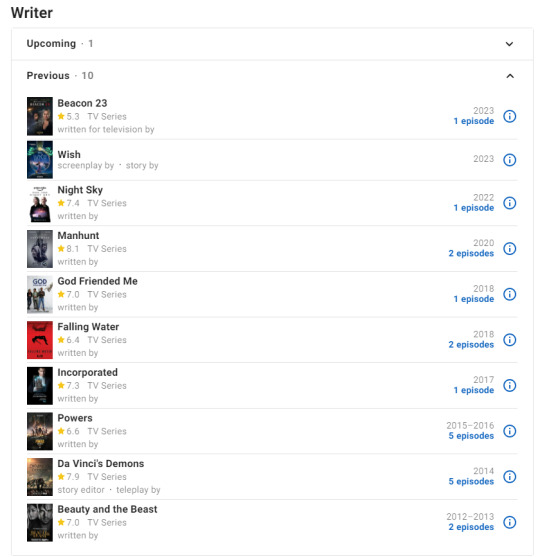

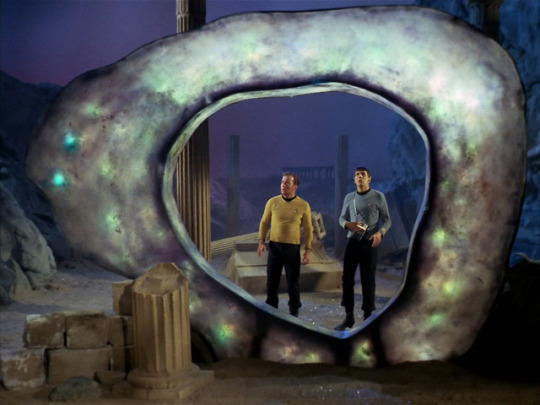

“Spock! Are you sure. Ellison. Passed. Through here?” “That appears so, Captain.”

Three of the most awesome space Jews ever!

#harlan ellison#star trek#i refuse to tag as tos because it's just called star trek dammit#the city on the edge of forever#leonard nimoy#william shatner#judaism#science fiction#hugo award#a.k.a.#cordwainer bird

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Febuwhump Day 2: Failed Rescue Attempt

Six of Crows, Inej Ghafa, Kaz Brekker; light whump (more character study)

A year ago, Inej started following Kaz to test how close she would have to be before he noticed her presence, which she could see in the way that his shoulders relaxed and lowered a fraction of an inch; he never said anything, but occasionally he would tip his chin up like he was catching sight of a bird, or checking the clouds for the weather. His eyes would unerringly find hers and then he would continue on his way like nothing happened.

Then she tested how far away she could be before his shoulders crept back up, but if he was so far away, even her ability to track him from the rooftops was at its limit. When she dropped back so far, the last thing she saw were his shoulders tightening under his coat before he disappeared into a crowd, around a corner, through a door.

Eventually, if Kaz didn’t have another job for her, she followed him to see where he went, what he did. Over time, she discovered that he had a favorite stall for hutspot and a cafe where the owner brought him coffee without either saying anything beyond the exchange of coins. He had a tailor across town that made his beautiful, meticulously fitted suits; a cordwainer in another far corner who made his heavy black boots; a glover from whom he bought his gloves. He mostly dropped off and picked up his own laundry and paid his laundress well. Kaz Brekker might be the Bastard of the Barrel, but he apparently had a second life as a young mercher with a taste for well-made clothes, far away from the Barrel.

Inej has long suspected that if he didn’t want company for these outings, he would find her other things to do while he makes them; instead, he either doesn’t care or he is trying to communicate something to her, something she doesn’t entirely understand. Seeing him through the window of his tailor’s shop is strangely intimate; she has seen a version of Kaz that she doesn’t think anyone else has.

Most of Kaz’s errands are during the day; night is for Barrel business. But something sends him rocketing out of the Crow Club on a single minded mission. Inej was about to head out for her own evening of spying, but something tells her she should follow Kaz instead. She pulls her grey hood up over her hair and climbs a drainpipe to take to the roofs while he stalks the streets, his cane tapping loudly on the stones.

It isn’t long before trouble finds him. Inej can’t see into the alley well, partially covered as it is by ornamental tile that overhangs the alley, but she is close when she hears a scuffle and a sickening crack that sounds like a blunt object impacting meat. She unsheathes Sankt Petyr before making her way to the eaves to peer over the edge. She wants to drop into the alley immediately, but knows that she’ll hurt Kaz’s chances and maybe herself if she lands in the wrong spot.

A large man has Kaz by the neck, held aloft and pressed against the alley wall. Kaz is grasping at the man’s hands, kicking and spitting like a wet cat. A young woman is holding a revolver on Kaz, but her eyes are wide, wild. Inej thinks maybe she’s not ready to fire into the melee and risk shooting the wrong man. Another man is sprawled on the cobblestones, blood pooling around what’s left of his head.

Inej is going to drop behind the woman with the gun, but the burly thug starts hitting Kaz against the wall, his skull impacting the stone. With no time to decide if it’s the smart choice, she hurls herself off the roof ledge and onto the man’s back, sinking her knife deep into his neck. He drops Kaz, who falls into a gasping heap. The man staggers backwards, but Inej is already launching herself towards the woman with the gun.

She doesn’t register the noise of the shot until she’s felt the impact in her shoulder. Inej looks down in surprise, thinking for the briefest moment that she doesn’t see any blood, before she realizes that her dark clothes hide the color. She wonders if she can use that to her advantage, but everything around her seems to happen so fast while her thoughts slow.

Black spots appear at the edge of her vision and the last thing Inej hears is, “I got Brekker and his Wraith!

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

End of year writing meme! 3, 19, 21, 23, 30? ^^

Thanks for the ask! 19 I answered below, so here are the others.

3. favorite line/scene you wrote this year?

There are quite a few lines in A Trip Down Paradise Alley that I like a lot, including:

Citizen Cullen scowls at him. ‘And I’ll need something else to wear: right now I look as convincing as a hoon in a hula skirt.

and

…life in all its galactic variety, a thousand habitats, a million sentient races, and all of them edible.

but I think my stand-out favourite scene is the start of chapter 3, because most of the ideas in the fic are deliberately drawn from other sources, but this was all mine:

Long ago, as a whim of some mediaplex heir or retired conglomerate zillionaire, a spherical arcology was brought to Alpha, towed in and tethered high over Terra Sector. Those wealthy enough to enter found its curving walls lined with manicured lawns, flowing streams and woodlands of carefully-selected trees; delicate herbivores drifted in little herds and clouds of long-tailed birds fluttered under a bright solstrip. For as long as the credit lasted it was a luxurious retreat, an escape for the privileged few, but in time its owner lost interest or the money ran out, maintenance ceased, and the artificial ecology was abandoned, its plants and animals left to fend for themselves.

Some failed and died, overwhelmed by the increasingly erratic environment, but many found the means to adapt to the fragmenting ecosystem: in place of the neat woodlands grew tangled forests of creeping vines and spined tree-ferns, able to shoot up three feet in a cycle when the solstrip flickered to sudden brightness, falling dormant again when it guttered low; instead of smooth turf fields of phosphorescent fungi bloomed in drought or endless downpour. And among them the introduced species and opportunistic newcomers found themselves new niches to exploit: scale-winged insects and predatory plants, skittering reptiles with poison-tipped barbs and vast-eyed night-hunting birds.

It’s Billy’s favourite place on the station, an object lesson in life’s determination to survive in the most unpromising circumstances.

21. most memorable comment/review

I actually sent this one in to ao3commentoftheday: someone read their way through five chapters of Necropolis and left the comment, ‘But how does it end?!’ And having a reader who was invested in the story galvanised me to finish it after a long hiatus.

23. fics you wanted to write but didn’t?

Ooh. There’s the secret fic that I’ve been struggling to finish - I hoped to have it done by Christmas, but didn’t make it; and I was going to write a Roman gladiator AU which never got off the ground. And I’m incubating one last prompt from Yuletide that I didn’t have time to do for the exchange itself. And there was that prompt that came up on tumblr, about police chief Billy/soft-spoken mob boss Goody - I don’t know if I’m capable of writing it, but I’d like to read it.

30. favorite fandom to read fic from this year?

Magnificent Seven all the way! Though I read a lot of MCU as well, and I’ve been entranced by the tiny fandoms which I discovered for Cordwainer Smith’s The Instrumentality of Mankind stories, and Ursula Le Guin’s The Author of the Acacia Seeds!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

----[]

http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=science+fiction+klassiker+bücher

http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=science+fiction

http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=flug+scheibe

http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=raum+schiff

--

https://www.tor-online.de/feature/buch/2019/03/die-100-besten-science-fiction-buecher-aller-zeiten

Die 100 besten Science-Fiction-Bücher (a..z)

Als es noch Menschen gab - Clifford Simak (City, 1952)

Andymon - Angela und Karlheinz Steinmüller (1982)

Auf zwei Planeten - Kurd Laßwitz (1897)

Auslöschung - Jeff VanderMeer (Annihilation, 2014)

Bedenke Phlebas - Iain M. Banks (Consider Phlebas, 1987)

Binti - Nnedi Okorafor (2015)

Blade Runner (Träumen Androide von elektrischen Schafen) - Philip K. Dick (Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep, 1968)

Blumen für Algernon - Daniel Keyes (Flowers for Algernon, 1966)

Der brennende Mann (Die Rache des Kosmonauten, Tiger! Tiger!) - Alfred Bester (The Stars My Destination, 1956)

Commander Perkins - H. G. Francis (1979, Hörspiele 1976)

Contact - Carl Sagan (1985)

Cyberabad - Ian McDonald (River of Gods, 2004)

Dämmerung - Octavia Butler (Dawn, 1987)

Dangerous Visions - Hrsg. Harlan Ellison (1967)

Die denkenden Wälder - Alan Dean Foster (Midworld, 1979)

Dhalgren - Samuel R. Delany (1975)

Doktor Ain - James Tiptree jr.

A Door Into Ocean – Joan Slonczewski

Die Drachenreiter von Pern - Anne McCaffrey (Dragonriders of Pern, 1977 - 2012)

Die drei Sonnen - Cixin Liu (三體 / 三体, 2008)

Die Ehen zwischen den Zonen Drei, Vier und Fünf - Doris Lessing (The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five, 1980)

Ein Junge und sein Hund - Harlan Ellison (A Boy and His Dog, 1969)

Einsatz der Waffen - Iain M. Banks (Use of Weapons, 1990)

Enders Spiel - Orson Scott Card (Ender’s Game, 1985)

Es stirbt in mir - Robert Silverberg (Dying Inside, 1972)

Evolution - Stephen Baxter (2003)

Der ewige Krieg - Joe Haldeman (The Forever War, 1974)

Expanse-Reihe - James A. Corey (2011 - )

Fahrenheit 451 - Ray Bradbury (1953)

Frankenstein oder Der moderne Prometheus - Mary Shelley (Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, 2018)

Foundation-Trilogie - Isaac Asimov (Foundation, 1951)

Die Frau des Zeitreisenden - Audrey Niffenegger (The Time Traveler's Wife, 2003)

Freie Geister (Planet der Habenichtse, Die Enteigneten) Ursula K. Le Guin (The Dispossessed, 1974)

Fremder in einer fremden Welt - Robert Heinlein (Stranger in a Strange Land, 1961)

Der futurologische Kongress - Stanislaw Lem (Kongres futurologiczny, 1971)

Gateway - Frederik Pohl (1977)

Gelb - Jeff Noon (Vurt, 1993)

Die Haarteppichknüpfer - Andreas Eschbach (1995)

Hardboiled Wonderland und das Ende der Welt - Haruke Murakami (Sekai No owari to Hādoboirudo Wandārando, 1985

Herland - Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1915)

Hier sangen einst Vögel - Kate Wilhelm (Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, 1976)

Die Hölle ist die Abwesenheit Gottes - Ted Chiang

Hyperion - Dan Simmons (1989)

Ich, der Robot - Isaac Asimov (I Robot, 1950)

Der illustrierte Mann - Ray Bradbury (The illustrated Man, 1951)

Die Insel des Dr. Moreau - H. G. Wells (The Island of Dr. Moreau, 1869)

Kinder der Zeit - Adrian Tchaikovsky (Children of Time, 2015)

Krieg der Klone - John Scalzi (Old Man’s War, 2005)

Krieg der Welten - H. G. Wells (The War of the Worlds, 1898)

Krieg mit dem Molchen - Karel Čapeks (Válka s mloky, 1936)

Die lange Erde - Stephen Baxter und Terry Pratchett (The Long Earth, 2012)

Der lange Weg zu einem kleinen, zornigen Planeten - Becky Chambers (The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, 2015)

Die Letzten der Menschheit – Walter Tevis (Mockingbird, 1980)

Der letzte Tag der Schöpfung - Wolfgang Jeschke

Liebe ist der Plan - James Tiptree jr.

Die linke Hand der Dunkelheit (Der Winterplanet) - (The Left Hand Of Darkness, 1969)

Little Brother - Cory Doctorow (2008)

Die Mars-Chroniken - Ray Bardbury (The Martian Chronicles, 1950)

Der Marsianer - Andy Weir (The Martian - 2001)

Die Mars-Trilogie (Roter Mars, Blauer Mars, Grüner Mars) - Kim Stanley Robinson (Red Mars, Blue Mars, Green Mars, 1992 - 1996)

Die Maschinen - Anne Leckie (Ancillary Justice, 2013)

Metro 2033 - Dmitri Glukhovsky (2007)

Der Mond ist eine herbe Geliebte (Revolte auf Luna, Mondpsuren) - Robert Heinlein (The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, 1966)

Morgenwelt - John Brunner (Stand on Zansibar, 1968)

Nachspiel-Trilogie (Star Wars) - Chuck Wendig (Aftermath 2015 - 2017)

Neuromancer - William Gibson (1984)

Das Orakel vom Berge - Philip K. Dick (The Man in The High Castle, 1962)

Otherland von Tad Williams

Per Anhalter durch die Galaxis - Douglas Adams (The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, 1979)

Perdito Street Station (Die Falter/Der Weber) - China Miéville (2000)

Perry Rhodan - Clark Dalton

Picknick am Wegesrand - Arkadi und Boris Strugatzki (Piknik na obotschinje, 1972)

Die Reise zum Mittelpunkt der Erde - Jules Verne (Voyage au centre de la terre, 1864)

Rendezvous mit Rama - Arthur C. Clark (Rendezvous with Rama, 1973)

Der Report der Magd - Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid’s Tale, 1985)

Ringwelt - Larry Niven (Ringworld, 1970)

Schöne neue Welt - Aldous Huxley (Brave New World, 1932)

Schlachthof 5 oder Der Kinderkreuzzug - Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, 1969)

Simulacron-3 - Daniel F. Galouye (1963)

Snow Crash - Neal Stephenson (1992)

Solaris - Stanislaw Lem (1961)

Spin - Robert Charles Wilson - (2005)

Der Splitter im Auge Gottes - Larry Niven und Jerry Pournelle (The Mote in God's Eye, 1974)

Starship Troopers (Sternenkrieger) - Robert Heinlein (1959)

Die Triffids - John Wyndham (The Day of the Triffids, 1951)

Ubik - Philip K. Dick (1969)

Uhrwerk Orange - Anthony Burgess (Clockwork Orange, 1962)

Das Unsterblichkeitsprogramm - Richard Morgan (Altered Carbon, 2002)

Utopia - Thomas Morus (De optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia, 1516)

Die vergessene Welt - Arthur Conan Doyle

Was aus den Menschen wurde - Cordwainer Smith (2011, umfasst Kurzgeschichten von 1928 bis 1966)

Wer fürchtet den Tod - Nnedi Okorafor (Who Fears Death, 2010)

Wir waren außer uns vor Glück – David Marusek

Das Wort für Welt ist Wald - Ursula K. Le Guin (The Word For World Is Forest, 1972)

Der Wüstenplanet von Frank Herbert (Dune, 1965)

Die Zeitmaschine - H. G. Wells (The Time Machine, 1895)

Zerrissene Erde - N. K. Jemisin (The Fifth Season. 2015)

1984 - George Orwell (1949)

2001 - Arthur C. Clark (1968)

20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer - Jules Verne (Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, 1869)

--

https://www.amazon.de/Science-Fiction-Bücher/s?k=Science+Fiction

--

national radio quiet zone

https://science.nrao.edu/facilities/gbt/interference-protection/nrqz

http://www.landesmuseum.at/de/ausstellungen/detail/paul-kranzler-andrew-phelps-es-war-einmal-in-amerika.html

--

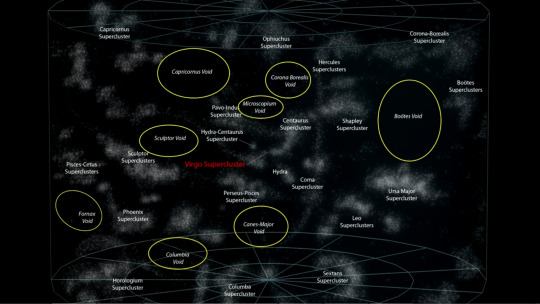

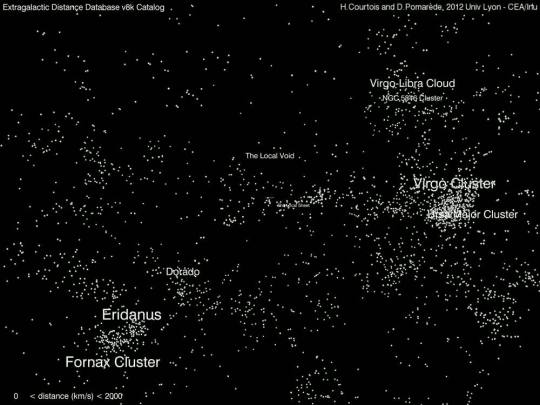

void

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Local_Void

Cosmicflows-3: Cosmography of the Local Void [] https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.08329

--

https://twitter.com/ESA # https://sci.esa.int/web/juice/home/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was the very first TV show you ever watched?

For a bit of fun, I’d like to ask folks to think back into their deep memories and try and recall the very first TV show they watched as a kid. It could be a show you watched all the time, or a one-off, something that rests in the back of your mind as your earliest TV memory. Recalling that there are folks who are now legal adults who were born in the year 2000 (making me feel old), if your earliest “TV” memory was actually a DVD or streaming video, that’s fine too.

I have some fragments of TV memories from earlier, but in terms of the first recognizable show, one I could actually say I was a fan of, it was a show that aired in the fall of 1973 when I was four years old:

The Starlost - the infamously low-budgeted sci-fi series created by Harlan Ellison (who disowned it and had his credit changed to his personal “Alan Smithee” - Cordwainer Bird). I remember the opening credits, the people flying down corridors, etc. I never saw the show again until the mid-1980s when I came across a rerun during a visit to Toronto, and got my first proper “revisit” when it came out on DVD a few years back.

What’s yours? (If I had the energy I’d tag some folks, but I’ll just leave this as a free ball for any followers or visitors who want to get in on this).

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cordwainer Bird speaks

There’s no polite way to tell you that it doesn’t matter what you believe.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Told ya, “The Things That Drop From Space” is a good title! Here’s Jonas Lopez Moreno’s artwork turned into a cover for a novel by award-winning science fiction author Avis P. Cobbler.

Before you run to the bookstore, let me explain: “Avis P. Cobbler” is a play on Harlan Ellison’s pseudonym “Cordwainer Bird” - “Avis” being Latin for “bird”, and cobbler, of course, repairing shoes (compared to cordwainer, who makes them). And the “P”? Well, depending on how hungry you are, it stands either for “pseudonym” or “peach”. ;)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flanner

Where my last story, A Plague Of Lucy, was inspired by the new generation of SFF writing, this story derives from something quite a bit older. For quite a while now I’ve been wanting to do something that draws, just a little, from classic SF writer Cordwainer Bird, and this seemed like an excellent chance. Bird came to SFF with a poetic sensibility which really stood out from his peers, which…

View On WordPress

0 notes

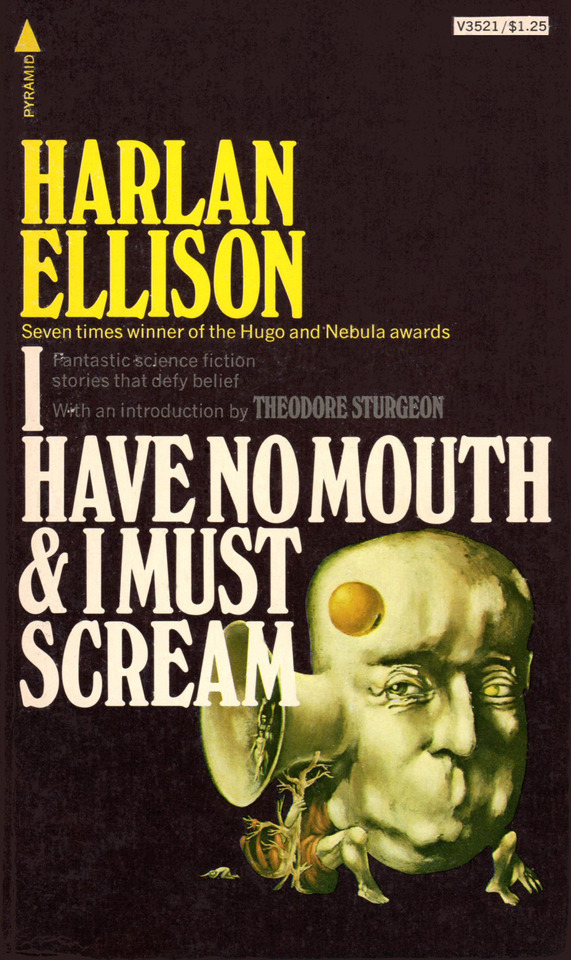

Photo

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream by Harlan Ellison (1967) is probably my favorite of his story collections.

Ellison won eight Hugo Awards; four Nebula Awards; five Bram Stoker Awards; two Edgar Awards; two World Fantasy Awards; two Georges Méliès fantasy film awards; and was a 2011 inductee into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Por que Harlan Ellison precisa ser publicado no Brasil?

New Post has been published on http://baixafilmestorrent.com/cinema/por-que-harlan-ellison-precisa-ser-publicado-no-brasil/

Por que Harlan Ellison precisa ser publicado no Brasil?

Atualmente o Brasil atravessa uma boa fase de publicações literárias que contemplam os gêneros de terror, de ficção científica e fantasia. Entretanto alguns escritores celebres destas searas permanecem inéditos no país, este é o caso do norte-americano Harlan Ellison, um dos autores mais influentes e polêmicos da ficção científica que merece ter sua obra traduzida para o português. Ellison é um escritor prolífico e premiado que produziu cerca de 1.700 contos, além de romances, roteiros audiovisuais, roteiros para quadrinhos, ensaios entre outros textos. Somente algumas histórias em quadrinhos roteirizadas por Harlan Ellison saíram por aqui, os destaques são Demônio da Mão de Vidro (Graphic Globo nº 2, de 1989), Batman 66: O Episódio Perdido (adaptação do roteiro nunca filmado para a série do Batman dos anos 1960), Jornada Nas Estrelas: A Cidade à Beira da Eternidade (baseado no episódio da série Star Trek), e Teatro das Sombras: Contos Fantásticos Além da Imaginação .

Harlan Ellison nasceu em 1934, na cidade de Ohio. Em 1951 ele entrou para a Ohio State University, mas ficou apenas 18 meses na faculdade pois socou um professor que denegriu a sua escrita. Provocador nato, Ellison fazia questão de sempre enviar uma cópia de seus livros para o tal professor. O autor começou a ser publicado ainda na década de 1950, quando ele se mudou para Nova York em 1955 decidiu se focar na ficção científica. Harlan Ellison, que nunca gostou de ser rotulado como escritor de FC, afirmou em uma entrevista registrada em vídeo:

Nós estamos no meio de uma revolução, é uma revolução de pensamento, mas é tão importante quanto a Revolução Industrial. Nesse período de confusão e incerteza em que vivemos, nós precisamos de uma nova literatura que fale diretamente com estes sentimentos e estas necessidades. A ficção cientifica e a ficção especulativa estão falando com todos os tipos de pessoas, eu acho que agora está se tornando a ficção do povo. Como as histórias que Charles Dickens escrevia, que eram consideradas ficção para o povo. Na ficção científica o sonho prevalece, e hoje em dia os sonhos parecem ser mais reais que a realidade. Fantasistas são um tipo especial de sonhadores, as mentes e os pensamentos deles vem de um lugar diferente.

Em 1958 Harlan Ellison já havia publicado mais de cem contos em diversas publicações, alguns dos textos foram reunidos nos livros A Touch of Infinity e The Deadly Streets, ambos lançados em 58. Web of The City, o primeiro romance de Ellison, também foi publicado no mesmo ano. Inspirado na obra do escritor pulp Hal Ellson, o livro trata do universo violento das gangues de adolescentes. Para escrevê-lo Harlan Ellison se tornou membro da gangue The Barons, que atuava em uma região perigosa do Brooklyn.

Harlan Ellison se diferenciava de outros escritores muito em função da narrativa e da escolha dos temas de suas histórias. Em 1961 o autor lança o romance Spider Kiss, sobre um jovem do campo que se torna uma estrela do Rockabilly, e a antologia de contos Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation, um livro que se afasta dos elementos fantásticos para mostrar as formas de injustiça que eram costumeiras nos Estados Unidos, tais como o racismo, intolerância, fanatismo e abuso de poder policial. O livro seguinte de contos de Ellison, cujo título é Ellison Wonderland, de 1962, permitiu que o escritor arrecadasse o dinheiro que precisava para se mudar para Los Angeles.

A partir dessa época Harlan Ellison passa a trabalhar constantemente escrevendo roteiros para séries como The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, A Lei de Burke, O Agente da Uncle e Route 66, além do roteiro do longa Confidências de Hollywood. Para o seriado The Outer Limits, Ellison criou dois roteiros antológicos: O Soldado e O Demônio da Mão de Vidro. Outro roteiro importante é o do episódio A Cidade à Beira da Eternidade, de Jornada nas Estrelas (Star Trek), considerado por alguns o melhor de toda a série clássica. Entretanto, Harlan Ellison reclamou das alterações no texto final feitas por Gene Roddenberry (criador de Star Trek) e outras pessoas. Ellison chegou a assinar certos roteiros com o pseudônimo de Cordwainer Bird para alertar o público de que a sua contribuição tinha sido deturpada.

A década de 1960 foi o auge criativo de Harlan Ellison, no conto “Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman, presente no livro Paingod and Other Delusions, o escritor mostra uma sociedade distópica em que todos precisam cumprir suas funções dentro de uma extremamente precisa tabela temporal, o atraso é considerado crime. Ellison utiliza uma narrativa não linear, começa a história no meio, volta para o início e depois a encerra, tudo isso sem o uso de flashbacks. O conto se principia com uma citação de Desobediência Civil, de Henry Thoreau, e faz uma crítica contra autoridades repressoras. O texto venceu o prêmio Hugo Award na categoria de melhor conto.

Um outro conto que conquistou o troféu foi Eu Não Tenho Boca e Preciso Gritar (I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream), de 1967, talvez o mais conhecido do autor e que pode ser encontrado na internet traduzido para o português. Trata-se de uma alegoria sobre o inferno em que cinco humanos são atormentados por um computador onisciente por toda a eternidade. Infelizmente poucas adaptações da literatura de Harlan Ellison chegaram ao cinema, a exceção é o filme O Menino e seu Cachorro, dirigido por L. Q. Jones em 1975, uma história que segue as aventuras de um adolescente e seu cachorro telepata por um futuro pós-apocalíptico arrasado por uma guerra nuclear. Harlan Ellison publicou primeiramente O Menino e seu Cachorro como um conto em 1968, mas expandiu a trama posteriormente gerando um ciclo de narrativas.

Em 1967 Harlan Ellison foi editor da seminal antologia de contos Dangerous Visions, publicação que ajudou a ficção científica a se modernizar e ampliar os limites do gênero. A seleção incluiu craques como Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, Philip K. Dick, J. G. Ballard, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber e Brian Aldiss. Dangerous Visions foi um sucesso instantâneo na cena literária, principalmente por abarcar histórias incomuns para o período, algumas escritas por mulheres, outras em que negros protagonizavam ou que envolviam temas tabus como sexo, religião e etc. Ellison queria justamente o material que nenhuma outra revista ou livro teriam a coragem de apostar, daí vem o título: visões perigosas.

O americano continuou a publicar regularmente durante as décadas de 1970 e 1980, quando já era reconhecido como um dos escritores fundamentais para os aficionados por ficção científica. O seu livro de contos Strange Wine, lançado em 1978, foi considerado por Stephen King como um dos melhores livros de horror escritos entre 1950 e 1980. Já No Doors, No Windows, de 1975, demonstra a versatilidade de Ellison ao reunir suas narrativas de mistério e suspense. Harlan Ellison recebeu alguns dos maiores prêmios literários como o Hugo, o Nebula, o Bram Stoker e o Edgar Alan Poe. Hoje em dia Ellison está com 83 anos de idade, seu último livro saiu em 2015 nos Estados Unidos, uma coleção de contos que ainda não haviam sido publicados. O documentário de 2007 Dreams with Sharp Teeth, dirigido por Erik Nelson, faz um resgate interessante da carreira de Harlan Ellison.

#Dangerous Visions#Eu Não Tenho Boca e Preciso Gritar#Harlan Ellison#Harlan Ellison deveria ser publicado no Brasil#O Demônio da Mão de Vidro#O Menino e seu Cachorro#Spider Kiss#Star Trek#Strange Wine#The Outer Limits#Web of The City

0 notes