#Classic SFF

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

dune — playlist

#dune#frank herbert#playlist#spotify playlists#spotify playlist#book playlist#literature aesthetics#books#book#bookish#bookblr#bookworm#bookstagram#dark academia#booklover#scifi#science fiction#classic sff#studyblr#aesthetic#moodboard#edit#film#movie#denis villanueve#hans zimmer#timothee chalamet#zendaya#moon#dark aesthetic

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Warden Review: SFF Standards, Updated

The Warden Review: SFF Standards, Updated

I am a sucker for fantasy adventure stories. I’m a sucker for necromancers as protagonists. Between all that and my considerable experience with the fantasy genre, The Warden by Daniel M. Ford seemed made for me. Though settling in was a little bumpy, once I was in I was hooked. Our protagonist Aelis is an …

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hot new hypothetical ethics question

If

1. The world-planning alien ocean you're studying creates a simulacrum of your dead ex-girlfriend from your memories of her

2. Said ex-girlfriend committed suicide after a very nasty breakup

3. But the simulacrums memories don't extend that far, and still thinks the two of you are in love

Then

4. Is it ethical to sleep with the simulacrum?

5. Is this a) xenophilia (alien construct), b) over-elaborate maturbation (she's formed entirely from your memories of the original) or c) just normal sex?

628 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rereading Shards of Honor once again, and knowing what I do about the SFF scene:

I suspect this book started as a novelette of just the Sergyar section, originally (Chapters 1-6) and LMB was encouraged to expand it. Which in hindsight we are all very thankful for, but the joins are there if I think to look for them.

#vorkosigan saga#it has the character of a classic SFF expansion of a set up scenario everyone loved

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endless list of favourite characters: VILA RESTAL (Blake's 7, Michael Keating, 1978-1981)

“Hello there. How are you? Excuse me wandering about your premises but I wonder if you can help me. I’m an escaped prisoner. I was a thief but recently I’ve become interested in sabotage, in a small way you understand, nothing too ambitious, I hate vulgarity, don’t you? Anyway, I’ve come to blow something up. What do you think will be most suitable?”

#tbs endless list of fave characters#gif#blake's 7#vila restal#michael keating#1970s#1980s#sff#my gifs#quotes#other people's property just comes naturally to me#i mean#it's vila#he's that classic sort of thief/coward/trickster/small man/jester character out of fantasy#landed in a terrible sff dystopia#and twisty and interesting like all the b7 characters#and if you hadn't already gathered that i'm always going to go for the magician-y/trickster/non-macho types#you have not been paying attention#(which is fair XD)#anyway#<3<3<3

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay putting this on my non-anon account because I'm THRILLED and also I guess I should share stuff I've got coming out and not just reblog grad school memes:

I HAVE A BOOK COMING OUT!

Andrion is the tale of Kallis "Andrion" of Athens, who fights against her father and the other orators for women's rights in Athens. She's ace and poly; the story is unashamedly queer, and so is the press.

It's about as close to historically accurate as you can get in a story with giant robots. I'm so fucking excited for this.

Anyway--Knight Errant's doing a Kickstarter for the 2023 catalogue, which I'll link in the next reblog, and the other two books this year also look amazing. We're all trans and queer. It's a micropress, but it's established with some great authors behind it. We've got almost 4.5k quid raised so far, including some funding from Creative Scotland--but we need 7k for full funding.

So if you want a copy, now's the time to order. ♥

Relevant links below!

#andrion novella#knight errant press#where to find my work#kickstarter#edinburgh#edinburgh press#scotland#scottish press#queer sff#sff#author tumblr#queer writers#queer fiction#trans authors#trans author#classics tumblr#classics author#ace rep

16 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Edan Lepucki

Octavia E. Butler published “Parable of the Sower” in 1993, when she was 46 and I was 12. I came to the book later than you might expect for an L.A. writer with a postapocalyptic novel of my own, but when I finally did, I was stunned. Here was a tale set in the world I knew in my darkest hours: the ravaged, water-starved, earthquake-ridden, fire-eaten Southern California that plays in my dreams, a vision of my dear, troubled homeland that will keep me up at night if I let it. This book — it was already in my bloodstream.

The story, which takes place in the now-uncomfortably-close 2024, is a string of diary entries written by a Black teenager named Lauren Olamina. She resides with her family in the fictional city of Robledo, 20 miles from the center of Los Angeles. Beyond the walls of her gated neighborhood roam violent thieves, feral dogs, illiterate water peddlers and addicts whose drug of choice makes them hungry for arson. When those walls are breached, most of the inhabitants killed for their property and possessions, Lauren flees. She disguises herself as a boy and, armed with the gun her preacher father taught her to shoot, joins the hordes of other migrants heading north on the 101 — on foot.

This is a future at once vivid and brutal, and it’ll scare you down to your scalp. How did Butler do it?

Perhaps it’s that the author — noted genius and inspiration for a thousand internet memes, with a middle school named after her and a new bookstore too — began as a daughter of Pasadena. She grew up in Southern California, as did I, and this place of sunshine and danger, with its attendant anxieties, must have imprinted on her, as it did on me.

But there’s more to it. A writer like Butler becomes iconic not only by reflecting our world and interrogating it but also by articulating our most profound truths. As I see it, Butler’s gift is naming vulnerability, exploring its burden and value.

In “Parable of the Sower,” Lauren is a “sharer,” meaning she suffers from a condition called “hyperempathy syndrome.” She can feel the pain and pleasure of others, and in this future there isn’t much pleasure to be had. For most of her life, Lauren kept her sharer status a secret because, as she tells it, “Being the most vulnerable person I know is damned sure not something I want to boast about.” As the story progresses, however, and she encounters the wider world, including her first sight of the Pacific Ocean, Lauren divulges her syndrome, her gift, to others.

She also tentatively shares the religion she is beginning to shape. For Lauren is also a prophet. She names her religion Earthseed, and in her journal entries we witness Lauren trying to make sense of it, to comprehend a system of meaning that she believes is already fully formed and simply waiting for her to bring it forth. Lauren isn’t the sloganeering prophet I’m used to; she is fumbling toward truth. Her vulnerability, no matter how burdensome, signifies hope. It is exhilarating and profound, and it’s what animates this dystopian novel.

For me, “Parable of the Sower” is a call to be daring in my fiction and to reside in feeling, to show characters revealing their most fragile selves — and at a high cost. What could be more dramatic? The question resonated as I wrote my forthcoming novel, “Time’s Mouth.” The book, like Butler’s, also takes place in California, and it’s also about a young woman with an exceptional way of experiencing the world — in this case, an ability to time travel to one’s own past. Butler’s novel led the way with its own wild premise, and it also taught me that a sensitive heroine must put herself at risk, must grapple to comprehend her gift, if her story is to feel consequential.

This is only one way my work is indebted to Butler, a writer who offered a terrifying vision of my hometown and showed a way forward — in fiction (and in the craft of fiction) if not in fact. Those who conjure frightening futures aren’t in the business of fortune-telling, only in the sharing of cautionary tales. I don’t want to find myself in the California of Butler’s imagination, as much as it might thrill, as easy as it is to picture. Thank goodness I can read it.

#books#reading#octavia butler#the parable of the sower#science fiction#scifi#sff#literature#classics

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

New UQuiz - What Classic SFF Trope Are You?

I made a new uquiz! It’s a personality quiz that assigns you a classic sci fi/fantasy trope. I really enjoy making these, so I might make more. Much earlier this year I made one that assigns the taker an antagonistic horror force, and that one was really fun to make as well. Feel free to let me know what you think of these quizzes! I try to give them engaging questions and interesting…

#classic tropes#fantasy fan#fantasy reader#fantasy tropes#fantasy writing#new uquiz#original uquiz#personality quiz#scifi reader#scifi tropes#scifi writer#sff stropes#transcendragons writes#trope quiz#tropes#uquiz#writer things#writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

New on the blog - I've read a couple of excellent SFF books this year that combine science fiction and classic detective stories with iconic Hollywood film adaptations. Nick and Nora in space? Sam Spade versus superhumans? Yes, please!

0 notes

Text

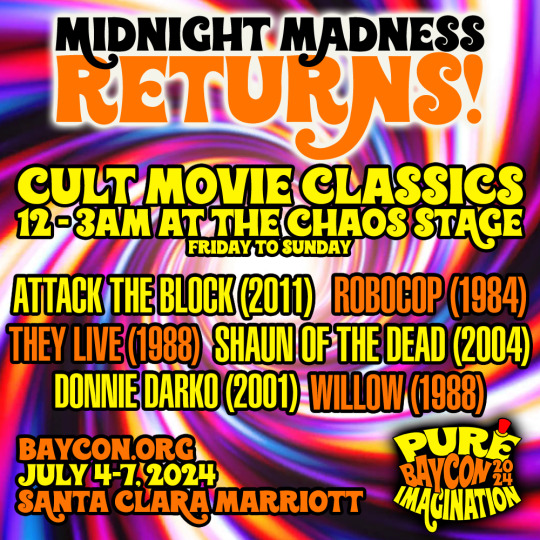

🌟 Dive into the extraordinary at BayCon's Midnight Madness! 🌌 Every night at the Chaos Stage, we unleash a world of Pure Imagination with back-to-back cult film gems. ✨

Are you ready to explore the uncharted realms of fantasy and creativity? Join us at midnight, where the wonders of cinematic artistry await. 🎬 Let's celebrate the magic of the movies under the spell of the night sky! 🌜

Friday at 12am: Attack the Block (2011), followed by RoboCop (1984)

Saturday at 12am: John Carpenter's They Live (1988), followed by Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Sunday at 12am: Donnie Darko (2001), followed by Willow (1988)

#baycon2024#fan convention#sff fandom#pure imagination#midnight madness#cult classics#bay area#willow#robocop#attack the block#shaun of the dead#they live#donnie darko

0 notes

Link

By Edan Lepucki

Octavia E. Butler published “Parable of the Sower” in 1993, when she was 46 and I was 12. I came to the book later than you might expect for an L.A. writer with a postapocalyptic novel of my own, but when I finally did, I was stunned. Here was a tale set in the world I knew in my darkest hours: the ravaged, water-starved, earthquake-ridden, fire-eaten Southern California that plays in my dreams, a vision of my dear, troubled homeland that will keep me up at night if I let it. This book — it was already in my bloodstream.

The story, which takes place in the now-uncomfortably-close 2024, is a string of diary entries written by a Black teenager named Lauren Olamina. She resides with her family in the fictional city of Robledo, 20 miles from the center of Los Angeles. Beyond the walls of her gated neighborhood roam violent thieves, feral dogs, illiterate water peddlers and addicts whose drug of choice makes them hungry for arson. When those walls are breached, most of the inhabitants killed for their property and possessions, Lauren flees. She disguises herself as a boy and, armed with the gun her preacher father taught her to shoot, joins the hordes of other migrants heading north on the 101 — on foot.

This is a future at once vivid and brutal, and it’ll scare you down to your scalp. How did Butler do it?

Perhaps it’s that the author — noted genius and inspiration for a thousand internet memes, with a middle school named after her and a new bookstore too — began as a daughter of Pasadena. She grew up in Southern California, as did I, and this place of sunshine and danger, with its attendant anxieties, must have imprinted on her, as it did on me.

But there’s more to it. A writer like Butler becomes iconic not only by reflecting our world and interrogating it but also by articulating our most profound truths. As I see it, Butler’s gift is naming vulnerability, exploring its burden and value.

In “Parable of the Sower,” Lauren is a “sharer,” meaning she suffers from a condition called “hyperempathy syndrome.” She can feel the pain and pleasure of others, and in this future there isn’t much pleasure to be had. For most of her life, Lauren kept her sharer status a secret because, as she tells it, “Being the most vulnerable person I know is damned sure not something I want to boast about.” As the story progresses, however, and she encounters the wider world, including her first sight of the Pacific Ocean, Lauren divulges her syndrome, her gift, to others.

She also tentatively shares the religion she is beginning to shape. For Lauren is also a prophet. She names her religion Earthseed, and in her journal entries we witness Lauren trying to make sense of it, to comprehend a system of meaning that she believes is already fully formed and simply waiting for her to bring it forth. Lauren isn’t the sloganeering prophet I’m used to; she is fumbling toward truth. Her vulnerability, no matter how burdensome, signifies hope. It is exhilarating and profound, and it’s what animates this dystopian novel.

For me, “Parable of the Sower” is a call to be daring in my fiction and to reside in feeling, to show characters revealing their most fragile selves — and at a high cost. What could be more dramatic? The question resonated as I wrote my forthcoming novel, “Time’s Mouth.” The book, like Butler’s, also takes place in California, and it’s also about a young woman with an exceptional way of experiencing the world — in this case, an ability to time travel to one’s own past. Butler’s novel led the way with its own wild premise, and it also taught me that a sensitive heroine must put herself at risk, must grapple to comprehend her gift, if her story is to feel consequential.

This is only one way my work is indebted to Butler, a writer who offered a terrifying vision of my hometown and showed a way forward — in fiction (and in the craft of fiction) if not in fact. Those who conjure frightening futures aren’t in the business of fortune-telling, only in the sharing of cautionary tales. I don’t want to find myself in the California of Butler’s imagination, as much as it might thrill, as easy as it is to picture. Thank goodness I can read it.

0 notes

Text

FINAL: Queer Adult SFF Books Bracket

Book summaries and submitted endorsements below:

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

A groundbreaking work of science fiction, The Left Hand of Darkness tells the story of a lone human emissary to Winter, an alien world whose inhabitants spend most of their time without a gender. His goal is to facilitate Winter's inclusion in a growing intergalactic civilization. But to do so he must bridge the gulf between his own views and those of the completely dissimilar culture that he encounters.

Embracing the aspects of psychology, society, and human emotion on an alien world, The Left Hand of Darkness stands as a landmark achievement in the annals of intellectual science fiction.

Science fiction, classics, speculative fiction, anthropological science fiction, distant future, adult

The Locked Tomb series (Gideon the Ninth, Harrow the Ninth, Nona the Ninth, and others) by Tamsyn Muir

Endorsement from submitter #1: "An extremely fun, humorous romp! A heart-breaking, soul crushing catharsis inducing tragedy! A thoughtful piece on imperial structures and trauma. On queerness, Muir flawlessly and without announcement, cracks gender open like an egg and spills its disproven guts across the page. The Locked Tomb does it all also bones, bitch."

Endorsement from submitter #2: "Lesbian necromancers in space. So many fascinating, sort of fucked up sapphic relationships going on."

The Emperor needs necromancers.

The Ninth Necromancer needs a swordswoman.

Gideon has a sword, some dirty magazines, and no more time for undead bullshit.

Brought up by unfriendly, ossifying nuns, ancient retainers, and countless skeletons, Gideon is ready to abandon a life of servitude and an afterlife as a reanimated corpse. She packs up her sword, her shoes, and her dirty magazines, and prepares to launch her daring escape. But her childhood nemesis won't set her free without a service.

Harrowhark Nonagesimus, Reverend Daughter of the Ninth House and bone witch extraordinaire, has been summoned into action. The Emperor has invited the heirs to each of his loyal Houses to a deadly trial of wits and skill. If Harrowhark succeeds she will become an immortal, all-powerful servant of the Resurrection, but no necromancer can ascend without their cavalier.

Without Gideon's sword, Harrow will fail, and the Ninth House will die. Of course, some things are better left dead.

Fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, humor, series, adult

#polls#queer adult sff#the left hand of darkness#ursula k. le guin#ursula k le guin#ursula le guin#the locked tomb#tlt#tamsyn muir#gideon the ninth#harrow the ninth#tlhod#nona the ninth#lhod#alecto the ninth#therem harth rem ir estraven#the locked tomb series#estraven#books#booklr#lgbtqia#tumblr polls#bookblr#book#lgbt books#queer books#poll#sff#sff books#queer sff

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

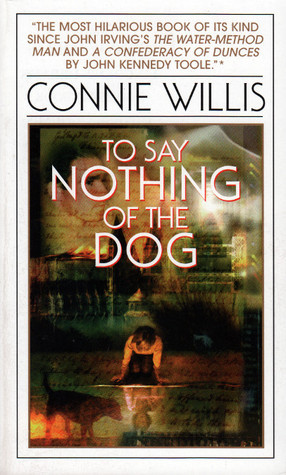

2024 Book Review #35 – To Say Nothing Of The Dog by Connie Willis

This was my second shot on reading something of Willis’, and I found it far more enjoyable than the first. Which is something of a feat, honestly – it’s a rare book that you can more-or-less accurately describe s a ‘cozy romcom’ that doesn’t make me recoil. But it was charming! And dated, but mostly only charmingly as well.

The story is the second in a series, which no one ever told me when recommending it because it does not matter in the slightest (at least, I had no issues at all following along with the story) – though it does mean that it hits the ground running and requires you to pick up quite a bit from context for the first while. It follows Ned Henry, a historian at the University of Oxford in the mid-21st century – a field that has been changed dramatically by the invention of time travel. For example, it’s suddenly in desperate need of particle-accelerator money, which is why and the entire rest of the department have been conscripted by an incredibly generous donor to help her reconstruct Coventry Cathedral exactly as it was before being destroyed in the Blitz. Exactly. ‘God is in the details’, and Henry has spent subjective weeks running himself ragged attending wartime rummage sales and sifting through bombed out ruins to try and verify the fate of a glorified flower pot mainly notable for being overdone and ugly even by Victorian standards.

After going through so many rapid-fire temporal shifts that the jump sickness leaves him waxing rhapsodic about the highway and falling in love with every woman he sees, he’s sent to Victorian Oxford to lay low and recuperate, and deliver a vitally important package to a contact already in situ. Unfourtunately that jump sickness means that he’s pretty unclear on the particular what and who. Really it’s remarkable that things don’t spin even more wildly out of control than they do (and there’s a period where he might have accidentally made the nazis win WW2).

So yeah, not what you’d call a serious novel. Most of the plot is sneaking around trying to make sure various members of the Victorian gentry fall in love in the right pattern to make sure someone’s grandson can fly in the RAF down the line and someone else elopes off to America on schedule (with drastically limited details and new information from back home changing things ever so often). Also sneaking a pampered rare-fish-hunting pet cat and slothful bulldog around before they arouse the wrath of their hosts. The apocalyptic threat that’s theoretically hanging over everyone never really feels real, and it’s all just pleasently absurd and enjoyable to read.

The comedy reminds me of early Prachett, in a way? Which like, a light comedy from the ‘90s in large part poking fun at English academia, of course there are similarities, but still. Not that that’s n insult. There’s plenty of absurd situations caused by miscommunication or desperately trying to work around absurd social conventions or personal foibles. Almost the entire Victorian cast (and a decent number of the present-day characters as well) are objectively ridiculous people, and the book has a lot of fun making do the literary equivalent of chewing scenery for the camera.

I call this a romcom, but I’m not ever sure that fits, honestly. It is a comedy with romance, between the two lead characters, whose dynamic with each other is the main throughline of the book. But it’s never really a source of drama? Or a motor of the plot. They are coworkers who end up working in close confines and get alone fine, who both awkwardly admit they find each other very attractive and start flirting and at the end they kiss and adopt a cat together. Least miscommunication- or conflict-ridden central romance in fiction you’ve ever seen. I don’t know enough about the genre constraints to determine whether it counts or not.

Part of the appeal of this was honestly the odd ways it came across as a bit dated? Not at all in a bad way but just, like – the fixation on the Blitz as the sine qua non of English history feels very 20th century? The references to the Charge of the Light Brigade and Schrodinger’s Box and Three Men in a Boat, combined with the felt obligation to step back from the narrative and explain what they were in case the reader wasn’t aware – just the idea that someone reading a time travel story won’t already be familiar with the concept of temporal paradoxes, really. It all added up to a reading experience that felt a bit off-kilter in a pleasing way.

This is obviously a story very fascinated by Victoriana – both the time period and the popular memory. Its perspective on the period is – I guess ���affectionate contempt’ might be the best way to put it? It clearly doesn’t think much of the Oxfordshire gentry, the women shallow as a puddle and obsessed with marriage gossip and spiritualism, the men with their heads stuffed with some academic fixation and utterly divorced from all practical affairs, both obsessed with petty one-up-man-ship of their peers and casually abusive and callous towards the servants who run and organize their lives for them. But it all feels rather good-natured; not a trace of righteous fury or real class hatred is on display, the fact of the empire and the source of their fortunes is I think not even mentioned. One more way it feels a bit dated, I suppose, or maybe just a way my usual reading’s much more explicitly political about these things.

I’m also not sure if this is a matter of tastes or popular memory changing or just my impression of what the received common wisdom is being parochial or inaccurate, but – given the association of ‘Victorian’ with imperial grandeur, aesthetic superiority, eye-wateringly expensive historical real estate, etc, it is quite funny how the book takes for granted that to be ‘victorian’ means to be horrifically gaudy and over-designed, devoid of elegance or restraint, and to have probably ruined some real medieval beauty in its creation.

Anyway yes, you absolutely could dig into this book and write some meaty essays out of it, but I simply was not reading it closely enough to do so. It’s probably overlong and definitely meandering and unhurried, but I did find it a really enjoyable read.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Updike (whom I haven't read but was a huge influence on the American lit scene) had a very similar take on all this; was going to add this Wikipedia screenshot but reading on hey what the fuck is Adam Roberts talking about

the term "literary fiction" as a genre is so silly to me thats like having a genre of film called "cinematic" or a genre of music called uh. music. "fantasy" means elements that are imaginary or mythological. fantastical even. "science fiction" means how the author imagines science and technology could develop in the future. "mystery" means. there is a mystery to solve. "literary" means..... there's a book.... about a guy?

#like i get what he's saying in that sff has had an unquantifiable impact on mainstream pop culture but#1. literary fiction DOES (sort of) sell well i think it just looks different than what he was reading at Cambridge or Oxford or wherever#2. let's maybe not couch book opinions in ghetto metaphors#('the classics' is of course a whole other european can of worms)#just noticed his name is mispelled; Wikipedia L#books

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

further to the book discourse while obviously its important to get new ideas & engage w challenging topics, people don't have to do that with like every type of media bcos no-one is into every type of media equally.

like im an SFF person so i do make a point to seek out classics of the genre & also to look for new and different perspectives. im not so fussed about movies and im not into music at all. some ppl are not into books but are very passionate about other kinds of media. there's all sorts of ways you can challenge yourself that don't involve reading books.

so no obviously its not a big deal if someone exclusively reads 1 genre of book or doesn't read books at all bcos prose fiction isn't everyone's primary way of engaging w culture and that's fine.

that said if we are talking specifically about people who are studying literature then yes it's reasonable to expect them to be reading broadly & actively challenging themselves and frankly kind of weird and patronising to imply otherwise.

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swoony Sapphic Romance Recs

Ever find f/f lukewarm? (It’s not you, it’s an industrial complex.) My intention here is to collect canonical sapphic rep that avoids the flat “girl meets girl” trope, where two women with doubtful chemistry are made to get together simply because they exist in the same narrative. I want media that will make me feverishly ship characters and spend at least 24 hours reeling from the brainrot in the aftermath. I don’t want to like a pairing just because they’re sapphic rep, I want it to be good and unforgettable. These lists are a wild jumble of genres, loosely organised (mostly novels, but I clarify when they aren’t), and in alphabetical order! I left out author names to avoid clutter. This is a living post and I will keep updating—please reblog or comment with your own recs if you wish!

⭐️: classics among sapphic media and/or criminally underrated essentials

Top tier best wlw romances: fluttery, swoony and angsty

in four, very loose categories

CONTEMPORARY

Bottoms (movie) ⭐️

How You Get the Girl

Iris Kelly Doesn’t Date

Kiss Her Once for Me

Love & Other Disasters

One Last Stop ⭐️

Saving Face (movie) ⭐️

She Loves to Cook, She Loves to Eat (manga/show)

The Fiancée Farce

XO, Kitty (show)

HISTORICAL

Annie on My Mind ⭐️

Don’t Want You Like a Best Friend

Gwen and Art Are Not in Love

Last Night at the Telegraph Club ⭐️

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo ⭐️

SCI-FI/FANTASY

A Dark and Drowning Tide

Arcane (animated show) ⭐️

Lucy Undying

The Midnight Lie ⭐️

Warrior Nun (show)

Youngblood (faced backlash for problematic content—check reviews before reading/supporting. Included here because sapphic romance itself is undeniably excellent.)

GRAPHIC NOVELS

Sunset Phoenix (webcomic)

Tamen de Gushi ⭐️

The Guy She Was Interested in Wasn’t a Guy at All ⭐️

The Princess and the Grilled Cheese Sandwich

Solid romance but less angsty:

Bloom Into You* (ani/manga)

Forget Me Not

If You’ll Have Me (graphic novel)

I Kissed Shara Wheeler

Magan & Danai (webcomic)

Run Away With Me, Girl (manga)

She Drives Me Crazy

These Witches Don’t Burn

Bonus: SFF with excellent sapphic characters (not romance focused)

A Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Pirates* (graphic novel)

Gideon the Ninth ⭐️ (this is its own genre and absolutely gutting despite not being heavy handed on the romance, very emotional and will make you want to put a butch in a pillow fort)

On a Sunbeam (graphic novel)

Shera and the Princesses of Power* (animated show) ⭐️

Bonus: Literary fiction (little focus on romance but packs a gut-wrenching punch)

Blue Sisters

Even Though We’re Adults (manga)

Our Dreams at Dusk ⭐️ (manga)

The Impossible Love Life of Amanda Dean

Wandering Son ⭐️ (ani/manga)

*sort of girl meets girl but worth plowing through for various reasons, usually their importance to sapphic media or LGBTQ+ discourse in the plot (might get taken off the list with time as I add better options!)

#gay#lgbt#queer#wlw#sapphic#f/f#lesbian#lgbtq+#bi#book recs#bookblr#media recs#pan#pansexual#bisexual#wlnb#the seven husbands of evelyn hugo#shera and the princesses of power#spop#arcane#the guy she was interested in wasn't a guy at all#bloom into you#anime#manga#anime recs#manga recs#recommendations#netflix recs#femslash#romantasy

61 notes

·

View notes